Karl Vick / Jerusalem

The Ultra-Holy City

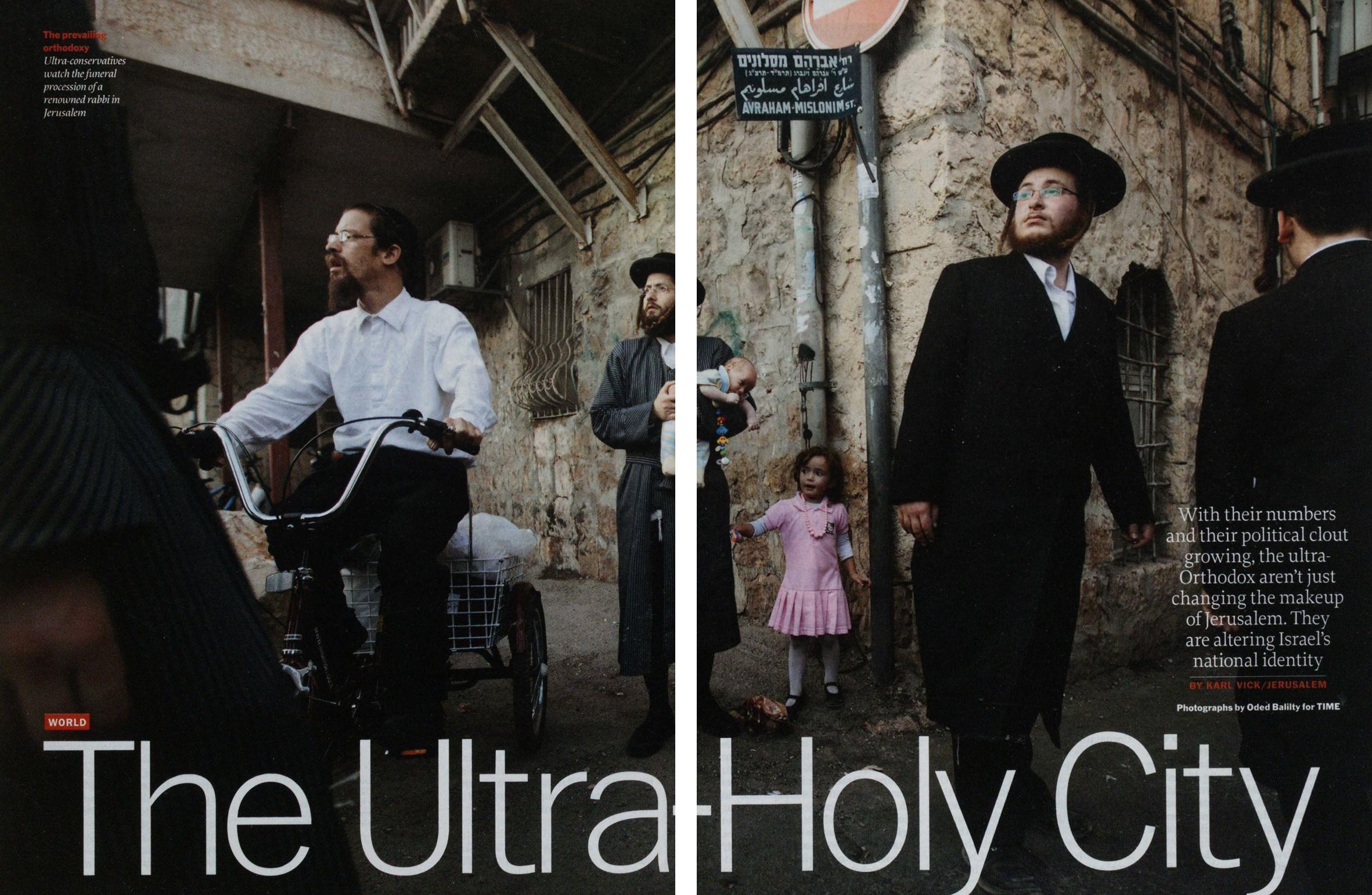

God was last known to reside approximately 300 yards north of the minimart at the corner of Ma’ale HaShalom and Wadi Hilwa. There stood the Second Temple, built around the Ark of the Covenant containing the Holy of Holies. And two millennia after the temple’s destruction, the power of the divine still radiated so potently from the remaining stones that Gibli recalls feeling it in his entire being the first time he entered Jerusalem’s Old City, at age 13. The welling of awe affirmed a pair of decisions: One was to live his life as his parents had, wholly within a very conservative strain of Judaism known as ultra-Orthodox. The other was to live that life in Jerusalem. Both would play hell with the local real estate market.

Millions visit the Holy City each year. Most are pilgrims to the signal sites of Christianity, though Muslims gather at their own great shrine above the Western Wall. Neither, however, are terribly welcome as residents. Since 1967, Jerusalem has become a resolutely Jewish city, so much so that the central question preoccupying residents today is not how it might be divided with Palestinians–for they are widely ignored of late–but rather just how religiously conservative the city can become while remaining a place most Israeli Jews could imagine living.

Forty-five years after the last decisive contest for the city–the lightning push by Israeli forces who needed just two days of the Six-Day War to take the whole place–a new battle for Jerusalem is under way. This contest is a grinding war of attrition, fought from trench lines etched across leafy neighborhoods of a city divided between Jews like Gibli, who wear black fedoras and sit primly away from women on public buses, and Jews like Noam Pinchasi, who keeps a glossy of Marilyn Monroe next to the fridge.

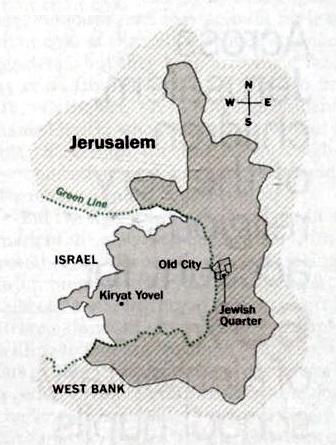

Both men own apartments in a neighborhood called Kiryat Yovel, a seemingly serene urban glade that is sizing up as the Somme or perhaps Little Big Horn. In a city of almost 800,000 people, Kiryat Yovel may be the last stand for Jews like Pinchasi, seculars who for decades have been fleeing the city in droves. Some 20,000 have left in the past seven years alone, reducing the share of the population who wear their faith lightly from a 37% plurality to a 31% minority, the same percentage as the ultra-Orthodox, but the number of ultra-Orthodox is rising. (About 35% of Jerusalem is Muslim Palestinian, with the remainder Christian or undeclared.)

It’s a flight much of Israel is watching with concern bordering on alarm. The ultra-Orthodox are the fastest growing population in a Jewish state long governed by seculars but lately grappling with just how Jewish it wants to be. Not three months after Benjamin Netanyahu assembled what was called a broad coalition of extraordinary stability, it flew apart over the question of what to do about the ultra-Orthodox. The centrist Kadima party returned to opposition after Netanyahu refused to alienate the religious parties by requiring their youth to serve in the military. Draft avoidance is just one privilege. The ultra-Orthodox, whose hermetic lifestyle may be based on preoccupation with the next world but whose political clout defines savvy in this one, also enjoy subsidies for child care, education and housing. The community’s power only grows with its numbers. Uncontained, it stands to fundamentally alter Israel’s identity.

“This is a war over territory,” says Pinchasi, speaking without metaphor. On Friday nights, he leads commando raids with like-minded compatriots on enemy positions, dodging police and groups of angry “blacks”–as the ultra-Orthodox are sometimes called–to sow discomfort and mischief. He’s been arrested; he’s been roughed up. But each week he’s back out, an urban guerrilla in a hoodie, slapping posters of classic nude paintings on synagogue doors. “They’re afraid their children will see things they shouldn’t see,” he explains. “Our message is very strong and clear: This is not like Ramot, Ramot Eshkol, Neve Yaakov, Maalot Dafna,” he says, naming Jerusalem neighborhoods that started out secular and are now solid black. “Here it is going to be war.”

Men in Black

Three generations ago, the ultra-Orthodox were all but extinct. Their Lazarus-like comeback either threatens the fabric of Israel or, as they see it, points the way to the nation’s salvation. Born in 18th century Eastern Europe–the inspiration for their wardrobe–the movement originated with rabbis who rejected the age of reason. Life was to be lived strictly by the Book–studying it and raising children in a tightly controlled environment to ensure that they would grow up to do the same. “We believe the way of life for us–to endeavor to keep the Bible, which we got from Moses–is difficult,” says Yitzchak Pindrus, the ultra-Orthodox vice mayor of Jerusalem. “For a teenager, a youngster, the way to keep it is to stay in a certain, let’s say, frame. That’s why we want to live like our grandfathers. It’s not about someone else,” he says. “It helps us keep the Bible.”

This means not only side locks on men and wigs or scarves on women but also separating girls from boys as early as nursery school. It means barring smart phones, which can access licentiousness on the Internet. It means a host of things far more easily assured if everyone in town is pulling in the same direction.

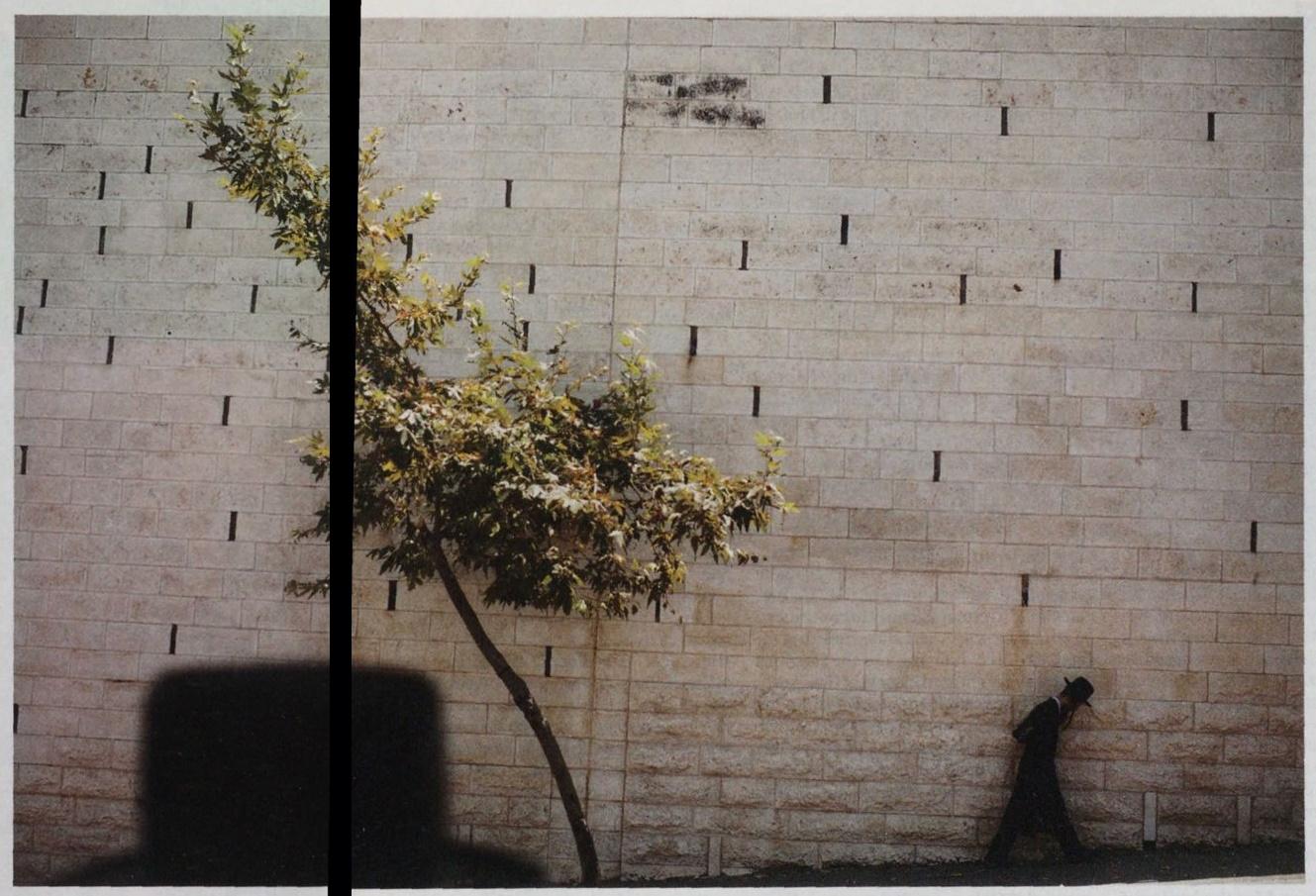

An ultra-Orthodox Jew walks on a street in the Yefe Nof neighborhood of Jerusalem

So when ultra-Orthodox Jews arrive in a neighborhood, they come in numbers. Three years ago, when Gibli moved to Kiryat Yovel, he was the first ultra-Orthodox in his building. Now ultra-Orthodox occupy four of the eight apartments. Like Gibli’s, each is crowded with religious books and children: Gibli and his wife Rachel have produced five in six years of marriage. “Every child is a gift,” he says.

As Jerusalem’s ultra-Orthodox community grows, it is expanding into secular areas like Kiryat Yovel

The munificence is changing the complexion of the city. At city hall on the day of our interview, Pindrus had appointments with three ultra-Orthodox groups looking to open kindergartens–the bellwether of a neighborhood turning black. In Jerusalem, the children of the very religious account for 65% of elementary-school pupils. Across Israel, where ultra-Orthodox now account for 10% of the population, they make up 21% of elementary-school enrollment. Demographers calculate that with a birthrate three to four times that of seculars, they will account for 1 in 5 Israelis in 20 years.

“We’ll give you a good price because we want you out of here,” a man in a black hat told a woman named Etty Ohaion when he knocked at her door one recent day. A lot of people would have sold.

Almost wiped out by the Nazis, the ultra-Orthodox now unnerve others with their fecundity, overflowing districts built expressly for them, conquering neighborhoods designated for others. But something was afoot in Kiryat Yovel. Ohaion closed her door. And when a religious man made an offer to Pinchasi’s neighbor, the urban guerrilla took things up a notch. “I have barbecues during Shabbat,” Pinchasi told the man, keenly aware of the prohibition on fire on the Sabbath. “Pork. We’re going to play music. We smoke.” His eyes danced. “And we bring prostitutes here. “

The man bought anyway, perhaps driven by the housing market’s law of supply and demand. One thousand religious couples wed in the city each year and start looking for a place of their own in the Holy City. Jerusalem is surrounded on its north, south and east by Palestinian territory, and they could move there. But Israel pays a political price every time it builds there. “Where am I supposed to go?” asks Gibli, on a park bench in Kiryat Yovel, which lies to the west.

Attacks and Counterattacks

Kiryat Yovel translates as “Jubilee Town.” Named to commemorate the 50th anniversary of the organization that began purchasing land for a future state, its streets are named for countries that voted to affirm Israel’s entry into the U.N. General Assembly and for the heroes of Zionism, the ideology that demanded the country’s creation. The neighborhood was never homogeneous: professors can be found in the single-family homes with the commanding views. Lower down lies Stern Street, named for the fascist founder of the preindependence Stern Gang and the progenitor of a gang of its own: delinquents from the high-rises hastily built to shelter the poorest immigrants. Still, until the ultra-Orthodox began buying about eight years ago, the area was overwhelmingly secular.

Pinchasi qualifies as a prototype. “I’m not an atheist,” he says. His family lights a candle and blesses the wine on Friday nights. Yet religion is an almost vestigial element of his primary identity, which is Israeli. Pinchasi personifies the New Jew, the muscular alternative early Zionist fashioned against the stereotype of the scrawny scholar of Eastern Europe’s ghettos–precisely the type embraced by the ultra-Orthodox. First as a paratrooper, then as a sky marshal and finally as a bodyguard for Israel’s President, Pinchasi devoted the first half of his life to protecting the state. When, in his 30s, he left the field to younger men, he decided to make a living with a driving school, only to find himself tooling around a city that looked less and less like him.

Jerusalem’s holiness was reasserting itself. “The whole idea of the spiritual Jerusalem is becoming much stronger,” says Rabbi Moshe Grylak, editor in chief of the ultra-Orthodox weekly Mishpacha. For decades, religious Jews, keen to remain near the Western Wall of the Second Temple, lived in the Old City or in a couple of neighborhoods outside. Today Jerusalem’s entire north side teems with men in black and women in wigs pushing baby carriages.

Their numbers brought political power, which brought money. In Israel’s parliamentary system, governments are formed by coalitions; since 1977, all but one have included ultra-Orthodox parties. They make great partners: religious parties deliver votes and in return ask only to continue to be left alone with their state subsidies for small children, housing and the religious schools that men attend most of their adult lives. “They’re working in a world economy but not in this world,” says Bar Ilan University professor Menachem Friedman, an expert on the ultra-Orthodox. “They’re accumulating mitzvahs to get a good seat in the next world.”

The arrangement began in 1948, when Israel’s founders created just 400 slots to replenish the stock of Torah scholars wiped out in the Holocaust. Thirty years later, Menachem Begin saw votes in increasing the number, and today Torah study has become an entitlement. Not even half of ultra-Orthodox men work for wages. Fewer still serve in the military. The situation engenders resentment among taxpayers and veterans that is lately exploding into the political realm. One of the events that shattered Netanyahu’s coalition was the “suckers protest,” 20,000 people taking their objections to the ultra-Orthodox into the streets–the venue Pinchasi has been sneaking down to for two years, always under cover of darkness.

Pinchasi ghosts around the block in his wife’s car, a white Subaru model called, nicely, a B4. The first lap is with headlights off. “I’m trying not to be paranoid,” Pinchasi says, but it’s a night operation in the new battle for Jerusalem, and he’s been tailed before. More than once, he says, an unmarked car disturbed the stillness of a Sabbath night a moment after his own car passed, falling in a few lengths back.

Another Friday after midnight, a squad car pulled up just as he got behind the wheel. “Hi, Noam,” the officer said. “Where are you going? I hope you’re not out to make trouble.” Pinchasi smiled. On the backseat lay a pot of glue and a roll of posters celebrating the unclothed female form. “I’m going here and there,” Pinchasi said, only the truth.

His crusade began after a pair of neighborhood pools banned mixed swimming during daylight hours. It gained steam when unlicensed synagogues appeared in homes and storefronts. The city forced some to close. Others Pinchasi shut himself, squirting glue into the locks.

“Then there’s the eruv thing,” Pinchasi says. An eruv is a boundary, a wire stretched around a Jewish town. Inside it, observant Jews are permitted to carry things–a purse, a prayer book–that they would otherwise be barred from lifting during the enforced rest of the Sabbath. There’s an eruv around the whole of Jerusalem, but newly arrived residents of Kiryat Yovel wanted their own. Without asking, they stuck poles on private property and strung wire between them.

Pinchasi got a saw. The racket drew witnesses, and he spent a night in custody. “We learned it was illegal to cut down even illegal poles,” he says. After that he found a more discreet way to cut wood, a kind of lacerating rope–“very quiet,” Pinchasi says–but the ultra-Orthodox answered his innovation with their own, girdling poles in steel sheaths. So Pinchasi went for the wire. To reach it, as high as a phone line, he first struggled with a Ginsu knife lashed to a stick. Then he discovered the Wolf-Garten professional tree trimmer. Made in Germany. It extends up to 4 m. 250 shekels (about $65). “The best of its kind,” he says, flourishing the contraption like a saber.

The man is full on. Pinchasi parks in the shadows, pulls up the hoodie and runs in a crouch. He snips the wire at one, two, three poles, then leaves behind a sticker: pirate eruv over a skull and crossbones. One night, about 30 ultra-Orthodox youths caught him in the act and roughed up his crew, including a Hebrew University professor. “To Prof. Dan and Noam, the secular maniacs,” reads graffiti on a utility box near their homes. “Stop. Get out of the neighborhood. You’re in our sights,” signed “The commando of the neighborhood.”

Pinchasi drives to Gibli’s neighborhood, parks and reaches for the posters. Botticelli’s The Birth of Venus goes up on a synagogue door, then on a recycling bin directly across the street. “My basic assumption,” Pinchasi says, “is if they feel uncomfortable, they won’t come here.”

Down but Not Out

The bookish ultra-Orthodox have their militants too, hard-eyed zealots whose extremism defines not only the public debate but increasingly the public spaces of Jerusalem. Downtown billboards in Israel’s capital no longer feature women; advertisers fear defacement or, worse, boycotts. On public buses, ultra-Orthodox women sit in the back–a situation Hillary Clinton likened to the pre-segregation South when it bubbled up in the controversy that consumed Israel in December. In Bet Shemesh, a half-hour outside Jerusalem, ultra-Orthodox men spit on an 8-year-old girl who was on her way to school, calling her a “whore” for her long-sleeved clothes, which were not conservative enough for their standards.

In Kiryat Yovel, most of the new arrivals are gentler, even sly. The latest eruv countermove was to forgo wire and demarcate a boundary with an array of potted plants. Indeed, Pinchasi’s victories may prove to be small battles in a larger war that he and those like him are losing. Religious Jews may account for less than 20% of the neighborhood’s 21,000 residents, but they keep arriving. “Ten, 15 years from now, it’s all going to be ultra-Orthodox,” says a religious resident named Itzick, who moved in three years ago. “It’s certain. It’s clear. All the neighborhoods that are secular are old people. There are no young people coming.”

But the fight’s not quite over yet. In a mark of the neighborhood’s strategic importance, secular families are organizing to buy property in Kiryat Yovel. The effort, dubbed New Spirit, began with a group of Hebrew University students who were unwilling to join the stream of young seculars exiting Jerusalem. “People do not feel together anymore. I think this is the major challenge in Israel today,” says one of them, Nir Yanovsky Dagan. “For me, Jerusalem is the center of the story.” The 10 fellow liberals in his self-made community banded together in something like one of the kibbutzim of early Israel. Dagan and his wife just signed to buy a flat in a building specifically swarmed by secular young families. It wasn’t easy. The ultra-Orthodox get subsidies, as do many who buy on the Palestinian side of the Green Line (where Dagan says city officials urged him to go). “I want a pluralistic city again,” he says.

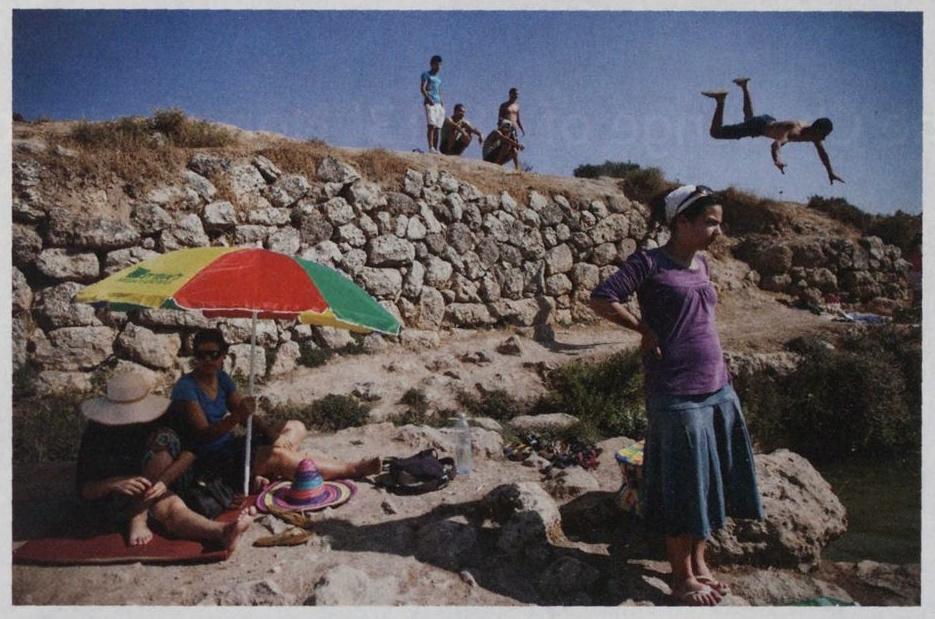

Secular and Orthodox Jews enjoy the sun at a spring-fed reservoir in Jerusalem

There are signs it might be working. This year the number of secular students in Jerusalem schools actually increased, after 15 years of decline. On the other hand, Dagan says one community is thinking of moving together to Bet Shemesh because its members can’t find affordable shelter in the capital.

At his desk in city hall, Pindrus smiles indulgently. “Be serious,” he says. “These 20 families, nice youngsters, come out of college, they’re going to change the area? Very nice.” He has 50 of his people living unseen like sleeper cells in an ostensibly secular neighborhood at the city’s southern border. “This is the reality in Jerusalem,” says Grylak, the ultra-Orthodox magazine editor. “Demography is geography.”