Kathe Callahan, Melvin J. Dubnick & Dorothy Olshfski

War Narratives: Framing Our Understanding of the War on Terror

Enhancing Homeland Security from a Public Administration Perspective

War Narratives and the Shaping of American Culture

The Centrality of Narratives in Social and Administrative Life

Making Sense of the State of War

Kathe Callahan

Rutgers University — Newark

Melvin J. Dubnick

University of New Hampshire

Dorothy Olshfski

Rutgers University – Newark

Kathe Callahan is an assistant professor of public administration at Rutgers University-Newark. She has published work on the topics of citizen participation, government performance, and accountability. Her most recent book, Elements of Effective Governance: Measurement, Accountability and Participation, will be published this fall by Auerbach Publications.

E-mail: kathe@andromeda.rutgers.edu.

Melvin J. Dubnick is a professor of political science and director of the MPA program at the University of New Hampshire. He is a recipient of the Mosher Award for a coauthored article in PAR (1987) and the Burchfield Award for the best book review published in PAR (2000). He has coauthored textbooks on public policy analysis, public administration, and American government.

E-mail: m.dubnick@unh.edu.

Dorothy Olshfski is an associate professor in the Graduate Department of Public Administration at Rutgers University-Newark. Her work has appeared in PAR and other leading journals. Her most recent book, Agendas and Decisions: How State Government Executives and Middle Managers Make and Administer Policy, with Robert Cunningham, will be published by SUNY Press this year.

E-mail: olshfski@andromeda.rutgers.edu.

Unlike past American wars, the current war on terror has not been associated with a centrally proffered narrative providing some guidance and orientation for those administering government services under state-of-war conditions. War is as much a cultural endeavor as it is a military undertaking, and the absence of a clear sensemaking narrative was detected in this study of public administrators from three agencies with varying proximity to the conflict. Q-methodology was used to explore the way individuals processed the war narratives put forth by the Bush administration and reported in the media immediately following the September 11 attacks. Though no distinct state-ofwar narratives were found among the public administrators in this study, there are clear indications that latent narratives reflecting local political and organizational task environments have emerged.

In past U.S. wars, a central narrative was a critical element in developing support and directing the war effort. This has not been the case with the present “war on terror.” Specifically, we found no evidence of a central war narrative in a sample of public administrators. The United States declared the war on terror with no established or emergent “state-of-war narrative.” As the existence of a coherent war narrative has proved to be a critical element in the conduct of past wars, it may be useful to evaluate the implications of this purported anomaly. Of special interest are the implications for public-service employees who, given their closeness to the conduct of wartime activities, might be expected to coordinate their efforts by reference to a common war story.

We begin our consideration of the absence of such a story by highlighting war as a cultural phenomenon, and then we turn our attention to the important role that narratives play in shaping the actions and decisions of public administrators. We consider the

circumstances surrounding the current war on terror in light of the absence of a clearly articulated state-of-war narrative. Specifically, we will focus on the meaning of four latent war narratives that have filled that void and explore the impact of these narratives among three groups of public administrators whose work and lives are affected by the current state of war. The idea of “going to war” seemed obvious enough at first blush: We have been attacked, and we plan to respond in kind. It was that simple—or was it?

Despite analogies that have been drawn to the attack on Pearl Harbor in 1941, the decision to enter a state of war after September 11, 2001, was a unique event in American history. Although other American wars are associated with triggering events—the bombardment of Fort Sumter, the sinking of the battleship Maine, the attack on Pearl Harbor, the invasion of Kuwait—none of those events occurred in a narrative vacuum. In each case, the road to war had been well paved materially, politically, and psychologically over an extended period of time. The shelling of Fort Sumter by South Carolinian troops was the culmination of events that had unfolded over several months after the election of Lincoln and after many years of heated discussion and debate (Agar 1966). The public clamor for war with Spain was already several years old when the battleship Maine exploded and sank in Havana Harbor in February 1898, but even then, two months passed before Congress declared war (Paterson 1996). The United States’ entry into World War I is often associated with the loss of American lives when the Lusitania was sank—but nearly two years and a great deal of preparation passed between that event and the declaration of war (Smith 1956; Thompson 1971). Although the attack on Pearl Harbor was a military surprise, it took place amid debate over plans for mobilization and ongoing preparations for war that had been building for at least two years (Fleming 2001; O’Neill 1993; Sagan 1988). And the extended buildup—psychologically as well as militarily—to the first Gulf War was still fresh in our memories as the process was repeated in 2003 (Gordon and Trainor 1995, 2006).

The war on terror that was triggered by the events of September 11 had no such gestation period. The state of war was declared by President George W. Bush and others without hesitation, but it was also done without any troops or plans in place to confront this particular enemy. Just as important, it occurred in a context of public indifference to or ignorance of the threat posed by terrorists. There had been discussions within the intellectual communities about possible “blowbacks” (Johnson 2000) and a coming “clash of civilizations” (Huntington 1996). There had also been warnings issued in a series of reports by a relatively obscure advisory commission chartered in 1998 by Secretary of Defense William Cohen.[1] But otherwise, little attention was given before September 11 to establishing a scenario for anything resembling a war on terror. Such matters as terrorist threats remained stories of law enforcement, criminal investigations, and the prosecution of bombers and their co-conspirators. The bombings of the World Trade Center in 1993 and the Alfred P. Murrah Federal Building in Oklahoma City in 1995, as well as the mischief of the Unabomber, were perceived as the criminal acts of fringe fanatics who would be brought to justice through the normal channels of law and order. Until the morning of September 11, 2001, however, there was no substantial story line in the popular press or from the government about a war on terror.

War as a Cultural Institution

Despite centuries of debate and study, the nature and origin of war remain points of contention dividing intellectual communities. This is true regardless of whether the subject is approached from an abstract philosophical position or from the practical viewpoint of military tacticians. Even the most fundamental and defining issues surrounding war—whether war is a product of nature or nurture—remain in dispute. The Hobbesian view of war as a presocial condition has not only retained credibility among students of politics but also garnered scholarly support from the work of ethnologists and sociobiologists, who stress the continuing impact of innate drives on individual and collective human behavior. In contrast, the Rousseauian position that war is a social artifact imposed on humankind through civil and political institutions relies on a growing body of historical and anthropological research that traces the development of “war machines” to collective actions first initiated in Neolithic cultures approximately 13,000 years ago.[2]

These positions converge in somewhat superficial agreement on the point that war has significance beyond the immediate enlistment and engagement of fighting forces. War is not merely an intermittent military endeavor involving the mobilization and strategic manipulation of troops and armaments. Whether it is rooted in human nature or social calculation, war soon becomes a key factor in the cultural lives and institutionalized relationships of all societies (Malinowski 1941; Zur 1987). The exact form and fit of war into the sociocultural milieu depends, of course, on the historical and social circumstances of the society (Clausewitz 1984, 707–18), and scholars disagree about whether the cultural role of war is functional or pathological.

Deleuze and Guattari (1986), for example, observe that nomadic societies are organized as war machines, not for the purpose of satisfying some genetic urge for violence or conquest but as a necessary complement to a life of traversing potential hostile territories and artificial borders. Students of ancient Greece have noted that a state of war was a pervasive condition reflecting the vulnerability of city-states to attack from other city-states or empires, leading Max Weber to observe that the ancient polis can best be understood as a “guild of warriors” (1978, 1359).[3] John Kenneth Galbraith (1971) presents a persuasive argument that the modern industrial state thrived for decades in both the United States and the Soviet Union with the assistance of a Cold War culture that amounted to a state-of-war condition just short of actual hostility.

Some scholars have stressed the pathological impact of the war culture on societies. John Keegan (1993), for example, regards war-preoccupied cultures as destructive at worst and antiprogressive at best.[4] Lewis Mumford regards war as “negative creativity” that ultimately offsets any real or potential gains from major technological advances (1970, 221). And as a counter to Galbraith’s thesis, Seymour Melman (1974) presents a case against the benefits of a war culture for economic well-being.[5]

Whether it is perceived as functional or pathological, the relationship between war and culture is an acknowledged fact of social life, and it is within that frame of reference that we will address the role of state-of-war narratives.

War Narratives and the Shaping of American Culture

Surprisingly little scholarship has focused on the role of narratives during times of war, and most of what we know of this topic is anecdotal (in the broad historical sense) or atheoretical. A number of scholars have examined how different national cultures— winners as well as losers—have handled the memory of past wars. Lundberg (1984) provides an analysis of the literature that emerged from the American Civil War, as well as the U.S. involvement in World Wars I and II; Moeller (1996) examines the search for a “usable” past in post-Nazi politics and more recent German literature; and Igarashi (2000) focuses on the literature of post-war Japan.

The American cultural experience with war narratives has received increasing attention in recent years. Historians note that, from the outset of colonial life in New England, the spiritual leaders of the Puritan regime used biblical narratives to counsel the colonists on the need to organize themselves in order to defend against the “heathen tribes” that populated the continent. Notably, until the 1670s, attacks by Native Americans were attributed as much to God’s testing of the spiritual community’s resolve as to the perceived barbarity (and satanic nature) of the attackers (Ferling 1981; Slotkin 2000, esp. chap. 2). The narrative changed during the mid-1670s, however, as colonists took the offensive and engaged in attacks that brought into question the Christian nature of the colonial forces. Behaving more like the so-called savages whom they had been sent to fight, the colonists engaged in a bloody campaign that showed no mercy. They were engaged in a “holy war” that required more than military victory—it also demanded that the defeated communities be terrorized so that the lesson of war would not be lost on either the survivors or future enemies (Ferling 1981, 30–33). Jill Lepore’s study of what has come to be known as King Philip’s War (1675–76) focuses on the role that narratives about the conflict played in establishing hostile boundaries of cultural differences that would shape colonist-Native American relations for decades (Lepore 1998).

As the threats of colonial life shifted from Native Americans to other colonies, so did the war narratives. During the period of intercolonial strife from the 1690s to the mid-18th century, more secular narratives arose. These stressed both regional interests and the need to defend the English colonies against the Spanish, French, and related enemies (i.e., Indian tribes that allied themselves with the “enemy”) (Ferling 1981, 34ff; Slotkin 2000, 224–41). This was followed by still another shift that reflected the colonists’ growing problems with Britain, which would eventually provide the narrative foundation for the American Revolution (Draper 1996; Miller 1943, chap. 8; Phillips 1999, chap. 5; Sieminski 1990).

In short, war narratives have played a central role in American history from the outset of colonization. Today, there is a growing literature that documents the American efforts to establish narratives to define the nation’s enemies and the threats they have posed. Some of these studies focus on the mass media’s role in preparing the public for war (Doherty 1999). Others concentrate on social scientists and other experts who create stereotypical images of enemy societies and the threats they pose to the American way of life (Robin 2001), as well as the way these images have pervaded American culture and narratives of the Cold War (Whitfield 1996).

This expansive and expanding literature on the importance of war narratives in American culture would be of little import outside academe if not for its relevance to the operations of government in the post-September 11 world. The uniqueness of the declared war on terror, both in terms of its timing and its terms of engagement, calls for a greater understanding of how state-of-war narratives affect the public administration community. This, in turn, requires a better understanding of the role that narratives in general play in administrative life.

The Centrality of Narratives in Social and Administrative Life

Narratives have taken on considerable importance in the social sciences in recent years. Relatively well established in literary studies for several decades (Bal 1997; Chatman 1978, 1990; Cobley 2001a, 2001b), the study of socially relevant narratives has emerged in several forms.[6] Among sociologists, anthropologists, and social psychologists, the use of discourse analysis (Gee 1999; Schiffrin, Tannen, and Hamilton 2001) has drawn greater attention to narratives used in distinct contexts, from daily conversations (Ochs and Capps 2001) and interactions in the workplace (Beech 2000; Boje 1991; Wajcman and Martin 2002) to physician-patient interactions (Waitzkin, Britt, and Williams 1994; Loewe et al. 1998) and celebrity interviews (Abell and Stokoe 1999). The new field of narrative psychology[7] has generated a number of studies dealing with the long-standing issues of self-identity (Ezzy 2000; Freeman 1999; Hermans 2001; Lindgren and Wáhlin 2001; Mason-Schrock 1996; Nelson 2001; Ochs and Capps 1996; Wahler and Castlebury 2002) and human development (Engel 1995; Grob, Krings, and Bangerter 2001; Gullette 2003; Jordan and Cowan 1995; Masahiko 2001; Nelson, Plesa, and Henseler 1998; Sperry and Sperry 1996; Sugiyama 2001). Meanwhile, legal scholars are paying greater attention to the role that narratives and storytelling play in the dynamics of litigation and legal reasoning (Amsterdam and Bruner 2000; Noonan 2002).

Political scientists have addressed narratives through the study of political culture and rhetoric (in the form of symbols, ideology, and myths) and public policy making. During the early 1970s, Murray Edelman drew attention to several “classic themes or myths” found in American political rhetoric. Years later, he discussed narratives as playing a key part in the “political spectacle” designed to generate desired reactions from the American public (Edelman 1971, 1988). H. Mark Roelofs (1976) posits a distinction between national ideology and national myth, noting that although ideology provides the country with a model of how things are done operationally, myth provides the cohesion and legitimacy for those government operations. For Roelofs, myth is the stuff of great orations, such as the Gettysburg Address, which contained fundamental aspects of American political thought. Today, these myths would be regarded as narratives that play a key role in the political acquiescence of the American public. James Oliver Robertson (1980) takes a similar approach, noting that mythical narratives are a part of the political reality and should be treated as such. Richard Merelman (1989), in a critique of traditional approaches to political culture that stress the “surface elements” of attitudes and values, calls for more attention to the fundamental narratives of “mythologized individualism” that underlie the political culture. More recently, Christopher G. Flood (1996) has posited the concept of “mythopoeic narrative” to stress the role that stories and storytelling play in all political cultures in supporting ideological positions. The common thread of these and related political science perspectives is the view of narrative as a tool—and a reflection—of political power.

Students of public policy have found the concept of ideological narratives increasingly useful. Some have stressed the important historical role that narratives, in the form of ideologies or schools of thought, have played in shaping foreign policy.[8] The role of narratives in other policy arenas is implied by those who focus on policy argumentation and policy design (Fischer 1995, part 5; Schneider and Ingram 1997).[9] Emery Roe’s (1994) efforts to apply literary narrative techniques to a range of policy debates in 1994 was the first major effort to focus attention on policyrelevant narratives, and in recent years, studies have been published on the role of narratives in such topics as postwar urban policies in the United Kingdom (Atkinson 2000), telecommunications in New Zealand (Bridgman and Barry 2002), environmental regulation in Canada and the United States (Bridge and McManus 2000), anticorruption in China (Hsu 2001), criminal justice in Britain (Peelo and Soothill 2000), and race and ethnicity in the United States (Yanow 2003).

Work specifically linking narratives with administrative decision making has emerged from the study of “sensemaking” by Karl Weick and his students.[10] Building on his earlier groundbreaking work on the social psychology of organizing, Weick (1995) makes narratives an important part of his examination of how people make sense of their environments. He argues that sensemaking precedes interpretation by isolating and focusing on some events among the flow of experience. By focusing on some specific events, outcomes are explained by assigning them to a plausible story to recount what is going on. Sensemaking needs a good story. Thus, stories, or narratives, are an important element of how individuals make sense of their environments and how they see themselves operating in those environments.

The war on terror provides an opportunity to extend Weick’s analysis of sensemaking in organizations to a more general context. The challenges of making sense of administrative life in the post-September 11 world go beyond understanding the limited and constrained capacity for rational decision making in modern organizations. Additionally, it is not limited to making sense of the bureaupathologies or the distortions and abuses of bureaucratic power. Rather, the challenge is to comprehend how public administrators contend with the uncertainties generated by a radically altered and threatening environment. How did public administrators contend with the sudden transformation of their lives from a relatively mundane post-Cold War indifference to a historically distinctive state-of-war condition in which the situation remains narratively ambiguous?

Making Sense of the State of War

The perspective applied here relies on narratives as more than merely a literary form, a rhetorical instrument of power, or a methodological tool that treats actions as texts. Narratives are fundamental to analyzing human consciousness and understanding—and thus to comprehending human thought and action. Human thought and action do not occur in a mental vacuum; rather, they are shaped by (and, in turn, shape) the ongoing processes of narration (i.e., sensemaking) that seem implied by the situation (Turner 1996).

We can pursue this perspective in three distinct ways. First, narratives can be approached as causal and controlling factors in social life. Such a position is strongly implied in the political and administrative culture literatures in which narratives take on determinative roles by shaping the realities, values, and premises that form attitudes, decisions, and behaviors. In this view, narratives are assumed to be an autonomous cultural artifact, distinct from any individual and generated by a community within a range of possible options. This is reflected in the cultural theory approach used by Mary Douglas and others (Douglas 1999; Thompson, Ellis, and Wildavsky 1990) and applied to public administration by Wildavsky (1987, 1988) and, more recently and elaborately, by Hood (1998).

A second approach treats narratives as dependent variables—as the product of bureaucratic behavior and administrative machinations. In this literature, narratives are not merely the vehicle through which bureaucratic control is exercised but the context created by and manifest in those narrative structures and the norms and assumptions they represent. This is the “lifeworld” of phenomenologists (see Schütz 1945, 1967) that has found expression in analyses of the bureaucratization of administrative, political, and social life (e.g., Hummel 1994).

The third and least developed approach is to regard narratives as the key intervening variable in social life in general and administrative life in particular. From this view, narratives are neither a source of external control nor a functionalist driver of the human life-world. Rather, they are the internalized media—the sensemaking mechanisms—through which human thought and action take shape. In the general literature, this approach has found it most explicit expression in the work of Dennett (1991, 1996). In the study of administrative life, it is the view central to the work of Weick (1995) and his colleagues.

Applying the third approach, for individual public administrators, the central question and challenge of the war on terror is to make sense of the radically altered environment and their respective places (and roles) in it. In lieu of an established meta-narrative— or at least efforts to develop and nurture a state-of-war narrative that identifies an enemy, end state, and some expectations regarding roles and obligations—what emerges in the consciousness of administrators are “multiple drafts.” In Dennett’s terms, these drafts represent the continuous revision of narratives through a complex multitrack process that occurs in “hundreds of milliseconds” and generates “something rather like a narrative stream or sequence” that is subject to “continual editing”:

Contents arise, get revised, contribute to the interpretation of other contents or to the modulation of behavior (verbal and otherwise), and in the process leave their traces in memory, which then eventually decay or get incorporated into or overwritten by later contents, wholly or in part. (Dennett 1991, 135; italics in original)

In Weick’s terms, public administrators are engaged in an ongoing process of making sense of the war on terror through state-of-war narratives drawn from past experiences, both real and perceived. The challenge we face is to understand how—and to what effect— those state-of-war narratives manifest themselves.

Contending State-of-War Narratives

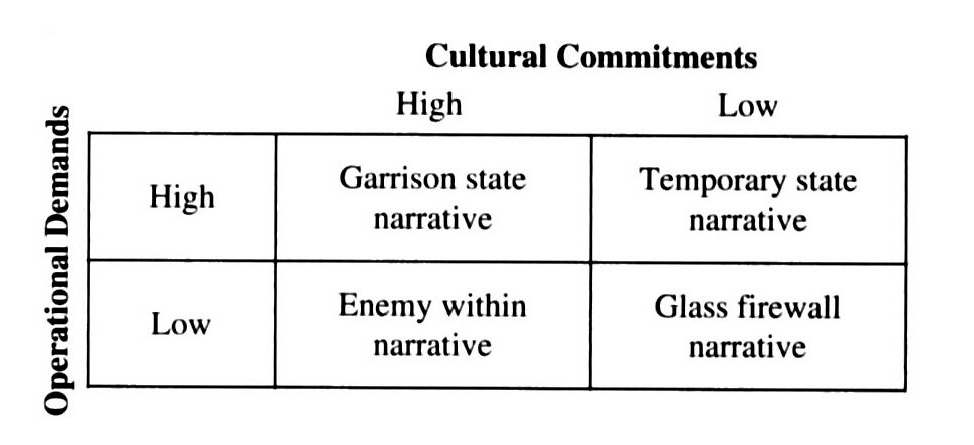

Of course, it would be absurd to contend that the war on terror occurs in a complete narrative vacuum. State-of-war narratives are a part of American culture, and public administtators are no less subject to the historical and popular images and myths of war that permeate American culture than other citizens. For empirical study, our framework for distinguishing among four common state-of-war narratives (Dubnick 2002; see figure 1) is based on the transposition of two salient features of such narratives: what they imply about the operational demands and the cultural commitments expected of American citizens. Operationally, a state of war may call for the full mobilization of our economic and social resources at one extreme or, at the other, a level of mobilization that generates minimal or isolated demands on the nation. In terms of cultural commitment, a state of war may be perceived as requiring a full integration of the war effort’s values, norms, and priorities in the national culture or, again at the other extreme, a minimal deference to the cultural demands of war. When combined, the two dimensions provide a framework outlining four options for the state-of-war narratives.

The substantive form of these narratives on the war on terror was identified through an analysis of speeches and news reports that emanated from politicians and administration officials after the September 11 tragedy. We want to emphasize that the narratives we identified are about the war on terror and the initial response to the terrorist attacks on the United States, not the ensuing war in Iraq, which was preceded by a war narrative buildup from September 2002 until the invasion the following spring. Four narratives were identified: (1) the garrison state narrative; (2) the temporary state narrative; (3) the glass firewall narrative; and (4) the enemy within narrative.

Briefly, under a garrison state, society is completely and permanently transformed to deal with present and future threats to national security. Society organizes itself around the constant threat of war—it becomes a war machine. This narrative can be viewed in its most extreme forms in George Orwell’s novel 1984 and in real life in contemporary North Korea. The concept is attributed to Harold Laswell, who in 1941 wrote of a future in which “specialists on violence are the most powerful group in society” (455). Someone who “hears” the garrison state narrative would agree with statements that reflect permanent changes in our society.

Source: Dubnick (2002).

The temporary state reflects the belief that measures taken during war are necessary but short term. The temporary state narrative reflects the ancient Roman doctrine inter arma silent leges, idiomatically, “in time of war, the laws are silent.” Public silence and violations of civil liberties are accepted because the condition is temporary. The belief is that the sooner we eliminate the enemy, the sooner life will return to normal. Someone who hears the temporary state narrative would agree that the violation of individual civil liberties is permissible, as long as it is short term (Rehnquist 1998).

The glass firewall narrative reflects two parallel administrative worlds—one civilian and one military—that operate simultaneously and in full view of each other. These parallel worlds are separated by a legal and organizational firewall that protects each from interference by the other (Stever 1999). During wartime, the military expects to call the shots without political interference. Someone who hears this narrative would agree with a statement regarding the expertise of the military and its ability to protect us. As civilians, we should go on with our lives, comfortable in the knowledge that the military will protect us.

The final narrative requires a high level of personal and cultural commitment. It is labeled the “enemy within” to stress its similarity to the anticommunist perspective that dominated the late 1940s through the mid-1950s. This narrative emphasizes that the threat to our security emanates from within our borders, and that as good Americans, we should ferret out dangerous individuals. The enemy in this war might very well be our own neighbor, and therefore we have to keep a watchful eye on one another and report any suspicious activity (Schulhofer 2002).

Methodology

Here we use Q-methodology to explore the way individuals process the war narratives expressed by officials in the Bush administration and captured by the media. Running counter to the usual expectations of large-scale survey research, the technique requires only small numbers. It groups like-thinking individuals together, allowing researchers to determine how groups differ in their thinking and to examine the differences in characteristics and attributes among the groups (Brown, 1980, 1996; McKeown and Thomas 1988). Q-methodology requires that individuals sort statements about a specific topic—in this case, the war on terror—and indicate how strongly they agree or disagree with each statement; ultimately, it requires them to distribute the statements in a bell curve that reflects their attitudes regarding the war on terrorism (Brown 1980, 1996).

Q-methodology requires participants to evaluate each statement in relation to the other statements. For example, do I disagree with this statement more than 1 disagree with that statement? The ranking of each statement influences the ranking of other statements and ultimately provides the researcher with a comprehensive view of the respondent’s subjective view on a particular topic.

Q-methodology was developed by psychologist William Stephenson, and it has been used widely in a variety disciplines. Gade et al. (1998) use this method to explore journalists’ attitudes toward civic journalism, Bussell (1998) examines parental choice of primary schools, and Dell and Korotana (2000) analyze reactions to domestic violence. In the field of public administration, this methodology has been used by Brown and Ungs (1970) to study reactions to the Kent State shootings; by Yarwood and Nimmo (1976) to study definitions and attitudes about bureaucracy; by Cunningham and Olshfski (1986) to describe the attitudes of legislators and administrators toward policy-making and implementation; by Selden, Brewer, and Brudney (1999) to explore how public managers view their roles and responsibilities; and by Brewer, Selden, and Facer (2000) to examine public-service motivation.

Q-methodology is particularly useful for examining individual views of war narratives because it is able to clarify subjective constructs, first using the quantitative aspect of the method, which groups like-thinking individuals together, and then the qualitative part of the method, which allows the researcher to observe the issues and concerns of those completing the exercise and to ask questions about those concerns.

The respondents in the present study were asked to arrange the statements, derived from the narratives, into a normal distribution. They were informed that the statements they were looking at had been selected from the war narratives put forth by the Bush administration and reported in the media immediately following the attacks of September 11. Each narrative produced six statements (see table 1), and these statements were placed on cards. The respondents were asked to arrange the cards, first into agree, disagree, and neutral categories. Then they were asked to refine their categories until they had four cards in both the strongly agree and strongly disagree categories, five cards in each of the somewhat agree and somewhat disagree categories, and six cards in the neutral column. This forced distribution requires that the participants compare the statements to each other and choose among them. The researchers were permitted to interact with the participants and note the comments made by the respondents as they struggled with the choices they were asked to make. Because Q-sort methodology focuses on an in-depth analysis of a number of individuals, a relatively small sample, or P-set, is required to establish groups. Emphasis is placed on the meaningful generalization obtained from a small sample rather than the size of the sample.[11]

Table 1 Narrative Statements

Garrison State

-

In a state of war, every decision we make—as citizens, as business people, as consumers—needs to start with the question: how will my actions or inaction impact on the war effort?

-

After 9/11 things will never be the same. War is going to be a permanent part of the American condition.

-

This war isn’t going to be won in a month or a year or even a decade. It will take a generation or two of being vigilant.

-

I am prepared to make permanent changes in my way of living to support the war on terror.

-

Since September 11th our country has entered into a permanent state of war and as a result we must be willing to make personal sacrifices to support the effort.

-

Declaring a war is one thing, being at war is another. We need total commitment if this war is going to be won.

Temporary State

-

The war on terror will make many demands on us, but eventually things will return to the way they were.

-

The violation of individual civil liberties is permissible as long as it’s short term.

-

The goals of the wars on terror are simple: find the enemy, deal with them, and then get back to our normal lives.

-

I am willing to subject myself to extensive security delays at the airport as long as it’s temporary.

-

I don’t complain because I know that all wars require temporary sacrifices and inconveniences.

-

The sooner we find and eliminate Osama and his gang, the quicker we can get on with our lives.

Enemy Within

-

The greatest dangers we face in the war on terror is not the visible enemy outside our borders, but the enemy within.

-

We need to be vigilant because threats can emanate from within our own neighborhoods.

-

Since the enemy in this war is able to hide within our communities, the government needs more power to use wiretaps and surveillance of possible “cell” members.

-

Ethnic and racial profiling in the cause of liberty is a necessary evil.

-

The job of every citizen is to remain vigilant and report any suspicious activity.

-

It is our responsibility as Americans to keep a watchful eye on one another.

Glass Firewall

-

Our military is prepared to do what needs to be done. We can fight terrorism without too much disruption in our daily lives.

-

Let the military provide security and protection; I don’t want to have to think about it.

-

In this war, the enemy wins if we allow him to disrupt our lives.

-

The military will protect us; we should just let them do their job.

-

Our role in the war on terror is to give the military and homeland security folks all the resources and support they need to do their jobs.

-

When it comes to war, let’s leave it to the experts.

Person Sample (P-Set)

Our person sample included 30 mid- to upper-level managers from the Port Authority of New York and New Jersey; the Newark District Office of the Immigration and Naturalization Service (INS) in Newark, New Jersey; and the township of Montclair, New Jersey. Ten public administrators from each agency or jurisdiction participated in this research.

The Port Authority of New York and New Jersey is responsible for the tunnels, bridges, terminals, airports, and ports in the New York and New Jersey region, as well as the Port Authority Trans-Hudson rail line. The World Trade Center was constructed and operated by the Port Authority. The managers from the Port Authority who participated in this research were responsible for departmental security, public safety, and customer relations for the tunnels and bridges. Five participants were at work in the World Trade Center on the morning of September 11, when 75 of their colleagues lost their lives. On the day we conducted our research (February 13, 2003), Tom Ridge, then secretary of homeland security, had just raised the risk of terrorist attack from an elevated (yellow) level to a high (orange) level, and as a result, there was a heightened sense of anxiety that day. The average American was trying to figure out the appropriate response to an undefined terrorist threat, and these managers were concerned with evacuation plans and strategies to protect the airports, bridges, and tunnels.

The Newark District Office of the INS serves the entire state of New Jersey; it is responsible for citizenship and immigration services, immigration and customs enforcement, and border protection. The responsibilities of the office are diverse and include services such as the processing of visa requests, the detention and deportation of illegal aliens, inspections at Newark Liberty Airport, and investigations, including the identification and prosecution of individuals involved in criminal activity and alien smuggling. The research participants held a variety of upper-level positions at the INS representing both enforcement and service. On the morning of September 11, managers from this district office were challenged to transfer high-risk federal inmates from a devastated and immobilized lower Manhattan location to a prison in New Jersey.

Montclair, New Jersey, is a municipality of 38,000 economically and racially diverse residents, located 12 miles west of Manhattan. Montclair, considered by many to be a liberal and progressive community, has strong ties with New York City. Many residents of this community work on Wall Street and in Lower Manhattan and were on their way to work or in their offices when the first plane hit. Nine members of the community perished in the attack, as did countless friends, relatives, and colleagues. The people who participated in this research worked for the township in various mid- and upper-level positions.

We selected these groups because each was affected by the attack on the World Trade Center and because they have different job responsibilities with respect to the war on terror; consequently, we thought they might be attuned to different war narratives.

We hypothesized that where one sits determines where one stands—that is, the salient narrative among groups of actors would depend on where they were situated relative to the conflict’s initial and potential flash points. We believed the Port Authority administrators, because they are charged with monitoring access to and egress from Manhattan, would be more attuned to the garrison state narrative. Furthermore, we expected the INS administrators, because the agency’s mission is to guard against illegal entry into the country, to be more in tune with the enemy within narrative. Finally, we thought the Montclair officials, because their jobs are further removed from active antiterrorist activities, would be more likely to adhere to the glass firewall narrative. We hypothesized that the temporary state narrative would be distributed among the groups. Succinctly, we expected that the personal narratives of the administrative professionals would be shaped not merely by their individual characteristics but also by task-environment factors such as the nature of their agency, perceived vulnerability to terror attacks, and exposure to the consequences of the conflict.

Demographics of the P-Set

Of the 30 participants in our research, 21 were men and 9 were women. On average, they had worked in the public sector for 20 years and had been in their current positions for 11 Vi years. Twenty-six possessed college degrees, 19 baccalaureates, and 7 graduate degrees. Eighteen of the participants were over the age of 50.

We asked participants to identify their primary source of news, their political affiliation, whether they or their family members served in the armed forces, and whether they thought their jobs had changed dramatically since September 11, 2001. The majority of respondents (11) relied on CNN as their major news source, followed by national newspapers (4), the Internet (4), and radio (3). Their political affiliations ran the gamut from apolitical to strongly partisan. Twelve identified themselves as Republicans, nine as Democrats, and six as independents. As far as political philosophy, nine considered themselves moderate, six conservative (from slight to extreme), and nine liberal (from slight to extreme). Ten participants felt that the Democratic Party is better able to keep us out of war, seven thought party did not matter, four were not sure, and two thought the Republican Party was better able to keep us out of war. Most of the respondents (15) agreed that their jobs had been dramatically affected by the events of September 11, and 13 agreed that their jobs were extremely close to the frontline of terror (see table 2).

Findings

We hypothesized that public sector employment and its closeness to the war on terror would strongly influence an individual’s own war narrative. However, we did not find clear and distinct state-of-war narratives among the three groups of administrators. We found the participants clustered into two factors, or groups. The narratives of one group centered on a concern for the protection of civil liberties. The other group identified with a narrative that reinforced the need to be vigilant and to do what is necessary to prevent future acts of terrorism and reduce the threat of war (see table 3).

The first group was dominated by seven public administrators from Montclair, but it also included two INS managers and two Port Authority managers. This group strongly disagreed with the necessity for any policy of racial or ethnic profiling and worried about violations of civil liberties as a result of the war on terror. They also felt that just getting rid of Osama bin Laden would not allow their lives to return to normal. This group agreed that we should not let the enemy disrupt our lives and that extensive security measures should be temporary. They seemed to assume a reactive posture with regard to the war on terror: Do not violate individual rights.

The second factor (or group) consisted largely of Port Authority managers. Four Port Authority administrators populated this group, but it also included one each from the INS and Montclair Township. This group felt the war on terror to be a disrupting force and that it would be difficult to get back to normal life. This group was concerned with being vigilant, reporting suspicious activity, and making changes in their way of life to fight the war on terror. They seemed to focus on a proactive response to the war: Be vigilant.

Q-sort methodology showed us where the two groups agreed and where they disagreed. Both groups agreed that the war on terror is not going to be won in a year or even a decade—it is going to take a generation of being vigilant. Additionally, both groups disagreed with the statement, “We should let the military protect us, I don’t want to think about it.”

Table 2 P-Set Demographics

| Total | Factor A (concern for civil liberties) | Factor B (concern for vigilance) | |

| Size of group | 30 | 11 | 6 |

| Average years in current position | 11.5 | 8 | 13 |

| Average years in public sector | 20 | 20 | 16 |

| Level of education | |||

| Undergraduate degree | 19 (63%) | 6 | 4 |

| Graduate degree | 7 (23%) | 3 | 1 |

| Gender | 21 men, 9 women | 7 men, 4 women | 4 men, 2 women |

| Age | 17 (56%) over the age of 50 | 9 (53%) over the age of 50 | 1 (6%) over the age of 50 |

| Primary news source | CNN 11 (38%) | CNN 4 (25%) | CNN 2 (12%) |

| Political identification | |||

| Apolitical | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Independent | 6 | 6 | 0 |

| Weak Democrat | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Independent Democrat | 4 | 1 | 1 |

| Strong Democrat | 2 | 0 | 0 |

| Independent Republican | 7 | 1 | 2 |

| Weak Republican | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Strong Republican | 5 | 0 | 3 |

| No opinion | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Political philosophy | |||

| Extremely liberal | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Liberal | 5 | 2 | 1 |

| Slightly liberal | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Moderate | 9 | 6 | 1 |

| Slight conservative | 3 | 0 | 1 |

| Conservative | 2 | 0 | 1 |

| Extremely conservative | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Political party best able to keep us out of war | |||

| Republicans | 2 | 0 | 2 |

| Democrats | 10 | 5 | 2 |

| Same/don’t know | 11 | 6 | 1 |

| Political party best able to handle international problems | |||

| Republicans | 10 | 2 | 5 |

| Democrats | 3 | 1 | 0 |

| Same/don’t know | 11 | 8 | 0 |

| Job changed dramatically since 9/11? | |||

| Agree | 15 | 5 | 4 |

| Somewhat agree | 5 | 3 | 1 |

| Neutral | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Somewhat disagree | 1 | 1 | 0 |

| Disagree | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Job extremely close to frontline? | |||

| Agree | 13 | 5 | 4 |

| Somewhat agree | 5 | 1 | 1 |

| Neutral | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Somewhat disagree | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Disagree | 4 | 3 | 0 |

Other characteristics of those who populated the first group—those concerned with civil liberties—were identified. Only one of the 11 managers in this group identified with the Republican Party and identified himself as an independent Republican. The remaining 10 members considered themselves Democrats (3), independents (6) or apolitical (1). Philosophically, they all categorized themselves within the range of middle of the road to extremely liberal. Eight of the members felt that their jobs had changed to some extent because of the war on terror, and six felt that they were working close to the frontline of the war on terror.

Conversely, with one exception, those who made up the second group—those concerned with vigilance—identified with the Republican Party. One member identified as a liberal, and the rest ranged from moderately to extremely conservative (one absent response). Everyone agreed that their jobs had changed since September 11 and that they were working close to the frontline of the war on terror.

The INS managers did not cluster in any significant way. This may be because the INS assumes multiple missions of service and enforcement. The INS managers who clustered with the other two groups probably did so because of their demographic characteristics, not the nature of their jobs.

Table 3 Q-Sort Results

Q-Sort Factors

Factor A: Concern for Civil Liberties

Eigen value = 6.26 explains 21% of the variance

Dominated by Montclair (7) but also included two managers each from the INS and Port Authority.

Disagreed with the following statements:

-

Let the military provide security and protection, I don’t want to think about it.

-

Ethnic and racial profiling in the cause of liberty is a necessary evil.

-

The violation of individual civil liberties is permissible as long as it’s short term.

-

The sooner we find and eliminate Osama, the quicker we get on with our lives.

Agreed with the following statements:

-

In this war, the enemy wins if we allow him to disrupt our lives.

-

I am willing to subject myself to extensive security at airport, as long as it’s temporary.

-

After 9/11 things will never be the same. War is going to be a permanent part of the American condition.

-

This war isn’t going to be won in a month or a year or even a decade. It will take a generation or two of being vigilant.

Factor B: Concern for Vigilance

Eigen value = 4.96 explains 17% of the variance

Dominated by Port Authority managers but included one each from the INS and Montclair Township.

Disagreed with the following statements:

-

Let the military provide security and protection, I don’t want to think about it.

-

The goals of the war on terror are simple: find the enemy, deal with them and then get back to our normal lives.

-

After 9/11 things will never be the same. War is going to be a permanent part of the American condition.

-

Our military is prepared to do what needs to be done. We can fight terrorism without too much disruption in our daily lives.

Agreed with the following statements:

-

The job of every citizen is to remain vigilant and report any suspicious activity.

-

We need to be vigilant because threats can emanate from within our own neighborhood.

-

I am prepared to make permanent changes in my way of living to support the war on terror.

-

This war isn’t going to be won in a month or a year or even a decade. It will take a generation or two of being vigilant.

Note: Bold indicates agreement between the two groups: italics indicates disagreement between the two groups.

Administration of the test proceeded differently with the three groups. The Montclair administrators complained repeatedly that they could not agree with any of the statements, and they found it difficult to place any of the cards in the agree category. The Port Authority administrators complained repeatedly that they could not disagree with any of the statements and they found it difficult to place any of the cards in the disagree category. The INS managers also found the categorization difficult, but as a group, their complaints were not uniform.

We discovered that the public administrators who participated in our study all heard a narrative, but what they heard seemed to be determined by their political outlook and ideological leaning. In the absence of a coherent meta-narrative delivered by an authoritative public figure, the individuals in this study relied on narratives that complemented their existing ideological perspectives, and these, in turn, seemed to be associated with the social, political, and administrative milieus in which they were operating. Not surprisingly, the narratives people hear are filtered through their frame of reference, or the latent narratives they have internalized.

Discussion and Conclusion

What has been absent in the case of the declared war on terror is an established or emergent narrative, generated from the political center with the intent of signaling a coherent response during a time of war. Although we identified four narratives emerging from top political figures in the Bush administration, none of these narratives captured the hearts and minds of the public officials in this study. Rather, those who participated in our study crafted narratives based on their own values and experiences. They chose statements about war that seemed to reflect their own interpretation of the role of government in society and the appropriate governmental reaction to a specific external threat. Thus, their narratives had a particularly conservative or liberal bent. The conservative narrative targeted vigilance and maintaining security, whereas the liberal narrative focused on civil liberties and the temporary nature of the disruption.

We argue that human thought and action do not occur in a mental vacuum; rather, they are shaped by (and, in turn, shape) ongoing narratives that are clearly articulated so as to be almost universally accepted as truth. Or, in lieu of a clearly posited narrative, human thought is structured by the latent narrative that emerges from the individual’s underlying story about the way the world operates. Thus one’s own latent narrative emerges as the sensemaking mechanism if no other coherent narrative is proffered.

Before September 11, the lack of a coherent, relevant, and widely articulated narrative about the war on terror created a narrative vacuum for the state of war that was declared after the attacks. The Bush administration’s efforts to articulate a post—September 11 state-of-war narrative resulted in multiple and ambiguous personal narratives. In lieu of any clear and coherent state-of-war narrative for the war on terror, the latent war narratives—those reflecting individual personal ideological and professional situations— filled the void.

Although we were able to examine the absence of clearly articulated perspectives in the narratives adopted by three groups of public administrators, it would have been desirable to include other groups in the analysis who were not so close to the September 11 devastation. At the time, however, we felt that because the situation was in flux—and we did not know how the story would unfold—we needed to capture the moment. In fact, several participants in our last sample group (March 2003) raised questions about the honesty and legitimacy of the statements they were being asked to reflect on. Questions about honesty and legitimacy did not enter into the discussions of September 11 that took place a month earlier. Knowing what we know now, we would have continued to monitor our participants in order to capture the dynamic nature of the war-narrative development, especially in light of the changing narratives emerging from legitimate governmental sources. Future research could continue to focus on the role narratives play in shaping the actions and decisions of public administrators and how narratives help people make sense of their environment.

References

Abell, Jacqueline, and Elizabeth H. Stokoe. 1999. “I Take Full Responsibility, I Take Some Responsibility, I’ll Take Half of It but No More Than That”: Princess Diana and the Negotiation of Blame in the “Panorama” Interview. Discourse Studies 1(3): 297–318.

Agar, Herbert. 1966. The Price of Union. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Amsterdam, Anthony G., and Jerome S. Bruner. 2000. Minding the Law. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Atkinson, Rob. 2000. Narratives of Policy: The Construction of Urban Problems and Urban Policy in the Official Discourse of British Government 1968–1998. Critical Social Policy 20(2): 211–32.

Bailey, Mary Timney. 1992. Do Physicists Use Case Studies? Thoughts on Public Administration Research. Public Administration Review 52(1): 47–54.

Bal, Mieke. 1997. Narratology: Introduction to the Theory of Narrative. 2nd ed. Toronto: University of Toronto Press.

Balfour, Danny L., and William Mesaros. 1994. Connecting the Local Narratives: Public Administration as a Hermeneutic Science. Public Administration Review 54(6): 559–64.

Bates, Robert H., Avner Greif, Margaret Levi, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Barry R. Weingast. 1998. Analytic Narratives. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Bates, Robert H., Avner Greif, Margaret Levi, Jean-Laurent Rosenthal, and Barry R. Weingast. 2000. The Analytic Narrative Project. American Political Science Review 94(3): 696–702.

Beech, Nic. 2000. Narrative Styles of Managers and Workers: A Tale of Star-Crossed Lovers. Journal of Applied Behavioral Science 36(2): 210–28.

Bevir, Mark, and R. A. W. Rhodes. 2001. Decentering Tradition: Interpreting British Government. Administration & Society 33(2): 107–32.

Bevir, Mark, and R. A. W. Rhodes. 2003. Searching for Civil Society: Changing Patterns of Governance in Britain. Public Administration 81(1): 41–62.

Bevir, Mark, R. A. W. Rhodes, and Patrick Weller. 2003. Traditions of Governance: Interpreting the Changing Role of the Public Sector. Public Administration 81(1): 1–17.

Boje, David M. 1991. The Storytelling Organization: A Study of Story Performance. Administrative Science Quarterly 36(1): 106–26.

Brewer, Gene, Sally Selden, and Rex Facer. 2000. Individual Conceptions of Public Service Motivation. Public Administration Review 60(3): 254–64.

Bridge, Gavin, and Phil McManus. 2000. Sticks and Stones: Environmental Narratives and Discursive Regulation in the Forestry and Mining Sectors. Antipode 31(4): 10–47.

Bridgman, Todd, and David Barry. 2002. Regulation is Evil: An Application of Narrative Policy Analysis to Regulatory Debate in New Zealand. Policy Sciences 35(2): 141–61.

Brown, Steven. 1980. Political Subjectivity: Applications of Q Methodology in Political Science. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Brown, Steven. 1996. Q Methodology and Qualitative Research. Qualitative Health Research 6(4): 561–67.

Brown, Steven, and Thomas Ungs. 1970. Representativeness and the Study of Political Behavior; An Application of Technique to Reactions to the Kent State Incident. Social Science Quarterly 51(3): 514–26.

Bussell, H. 1998. Parental Choice of Primary School: An Application of Q-Methodology. Service Industries Journal 18(3): 135–48.

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin. 1978. Story and Discourse: Narrative Structure in Fiction and Film. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Chatman, Seymour Benjamin. 1990. Coming to Terms: The Rhetoric of Narrative in Fiction and Film. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Clausewitz, Carl von. 1984. On War. Translated by M.E. Howard and P. Paret. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Cobley, Paul. 2001a. Analysing Narrative Genres. Sign Systems Studies 29(2): 479–502.

Cobley, Paul. 2001b. Narrative. London: Routledge.

Connor, W. R. 1988. Early Greek Land Warfare as Symbolic Expression. Past and Present 119: 3–29.

Cunningham, Robert, and Dorothy Olshfski. 1986. Interpreting State Administrator-Legislator Relationships. Western Political Science Quarterly 39(1): 104–17.

Dawson, Doyne. 1996. The Origins of War: Biological and Anthropological Theories. History and Theory 35(1): 1–28.

Deleuze, Gilles, and Fâelix Guattari. 1986. Nomadology: The War Machine. New York: Semiotext(e).

Dell, P., and O. Korotana. 2000. Accounting for Domestic Violence: A Q-Methodology Study. Violence against Women 6(3): 286–310.

Dennett, Daniel C. 1991. Consciousness Explained. Boston: Little, Brown.

Dennett, Daniel C. 1996. Kinds of Minds: Toward an Understanding of Consciousness. New York: Basic Books.

Doherty, Thomas Patrick. 1999. Projections of War: Hollywood, American Culture, and World War II. New York: Columbia University Press.

Douglas, Mary. 1999. Four Cultures: The Evolution of a Parsimonious Model. Geojournal 47(3): 411–17.

Draper, Theodore. 1996. A Struggle for Power: The American Revolution. New York: Times Books.

Dubnick, Melvin J. 2002. Postscripts for a “State of War”: Public Administration and Civil Liberties After September 11. Special issue, Public Administration Review 62: 86–91.

Edelman, Murray J. 1971. Politics as Symbolic Action: Mass Arousal and Quiescence. Chicago: Markham.

Edelman, Murray J. 1988. Constructing the Political Spectacle. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Engel, Susan. 1995. The Stories Children Tell: Making Sense of the Narratives of Childhood. New York: W.H. Freeman.

Ezzy, Douglas. 2000. Illness Narratives: Time, Hope and HIV. Social Science and Medicine 50(5): 605–17.

Ferling, John. 1981. The New England Soldier: A Study in Changing Perceptions. American Quarterly 33(1): 26–45.

Fischer, Frank. 1995. Evaluating Public Policy. Chicago: Nelson-Hall.

Fleming, Thomas J. 2001. The New Dealers’ War: FDR and the War within World War II. New York: Basic Books.

Flood, Christopher. 1996. Political Myth: A Theoretical Introduction. New York: Routledge.

Freeman, Mark. 1999. Culture, Narrative, and the Poetic Construction of Selfhood. Journal of Constructivist Psychology 12(2): 99–116.

Gade, P., S. Abel, M. Antecol, H. Hsueh, H. Hume, A. Packard, S. Willey, N. Fraser and K. Sanders. 1998. Journalists’ Attitudes toward Civic Journalism Media Roles. Newspaper Research Journal 19(4): 10–26.

Galbraith, John Kenneth. 1971. The New Industrial State. 2nd ed. New York: New American Library.

Gee, James Paul. 1999. An Introduction to Discourse Analysis: Theory and Method. London: Routledge.

Gordon, Michael R., and Bernard E. Trainor. 1995. The Generals’ War: The Inside Story of the Conflict in the Gulf. Boston: Little, Brown.

Gordon, Michael R. and Bernard E. Trainor (2006). Cobra 2: The Inside Story of the Invasion and Occupation of Iraq. New York, Pantheon Books.

Grob, Alexander, Franciska Krings, and Adrian Bangerter. 2001. Life Markers in Biographical Narratives of People from Three Cohorts: A Life Span Perspective in Its Historical Context. Human Development 44(4): 171–90.

Gullette, Margaret Morganroth. 2003. From Life Storytelling to Age Autobiography. Journal of Aging Studies 17(1): 101–11.

Hart, Gary, Warren B. Rudman, et al. 1999. New World Coming: American Security in the 21st Century—Major Themes and Implications: The Phase I Report on the Emerging Global Security Environment for the First Quarter of the 21st Century. Washington, DC: U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century.

Hart, Gary, Warren B. Rudman. 2000. Seeking a National Strategy: A Concert for Preserving Security and Promoting Freedom—The Phase II Report on a U.S. National Security Strategy for the 21st Century. Washington, DC: U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century.

Hart, Gary, Warren B. Rudman. 2001. Road Map for National Security: Imperative for Change—The Phase III Report of the U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century. Washington, DC: U.S. Commission on National Security/21st Century.

Hedges, Chris. 2002. War Is a Force That Gives Us Meaning. New York: Public Affairs.

Herberg-Rothe, A. 2001. Primacy of “Politics” or “Culture” over War in a Modern World: Clausewitz Needs a Sophisticated Interpretation. Defense Analysis 17(2): 175–186.

Hermans, Hubert J.M. 2001. The Dialogical Self: Toward a Theory of Personal and Cultural Positioning. Culture and Psychology 7(3): 243–81.

Hood, Christopher. 1998. The Art of the State: Culture, Rhetoric, and Public Management. Oxford, UK: Clarendon Press.

Hsu, Carolyn L. 2001. Political Narratives and the Production of Legitimacy: The Case of Corruption in Post-Mao China. Qualitative Sociology 24(1): 25–54.

Hummel, Ralph P. 1991. Stories Managers Tell: Why They Are as Valid as Science. Public Administration Review 51(1): 31–41.

Hummel, Ralph P. 1994. The Bureaucratic Experience: A Critique of Life in the Modern Organization. 4th ed. New York: St. Martin’s Press.

Hunt, Michael H. 1987. Ideology and U.S. Foreign Policy. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Huntington, Samuel P. 1996. The Clash of Civilization and the Remaking of World Order. London: Touchstone/Simon & Schuster.

Igarashi, Yoshikuni. 2000. Bodies of Memory: Narratives of War in Postwar Japanese Culture, 1945–1970. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Johnson, Chalmers A. 2000. Blowback: The Costs and Consequences of American Empire. New York: Metropolitan Books.

Jordan, Ellen, and Angela Cowan. 1995. Warrior Narratives in the Kindergarten Classroom: Renegotiating the Social Contract? Gender and Society 9(6): 727–43.

Kaplan, Thomas J. 1986. The Narrative Structure of Policy Analysis. Journal of Policy Analysis and Management 5(4): 761–78.

Keegan, John. 1993. A History of Warfare. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Kelly, Marisa, and Steven Maynard-Moody. 1993. Policy Analysis in the Post-Positivist Era: Engaging Stakeholders in Evaluating the Economic Development Districts Program. Public Administration Review 53(2): 135–42.

Laswell, Harold D. 1941. The Garrison State. American Journal of Sociology 46(4): 455–68

Lepore, Jill. 1998. The Name of War: King Philip’s War and the Origins of American Identity. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Levi, Margaret. 2002. Modeling Complex Historical Processes with Analytic Narratives. Paper presented at the Problems and Methods in the Study of Politics Conference, December 6–8, New Haven, CT.

Lindgren, Monica, and Nils Wåhlin. 2001. Identity Construction among Boundary-Crossing Individuals. Scandinavian Journal of Management 17(3): 357–77.

Loewe, Ronald, John Schwartzman, Joshua Freeman, Laurie Quinn, and Steve Zuckerman. 1998. Doctor Talk and Diabetes: Towards an Analysis of the Clinical Construction of Chronic Illness. Social Science and Medicine 47(9): 1267–76.

Lundberg, David. 1984. The American Literature of War: The Civil War, World War I, and World War II. American Quarterly 36(3): 373–88.

Malinowski, Bronislaw. 1941. An Anthropological Analysis of War. American Journal of Sociology 46(4): 521–50.

Manicas, Peter T. 1982. War, Stasis, and Greek Political Thought. Comparative Studies in Society and History 24(4): 673–88.

Masahiko, Minami. 2001. Maternal Styles of Narrative Elicitation and the Development of Children’s Narrative Skill: A Study on Parental Scaffolding. Narrative Inquiry 11(1): 55–80.

Mason-Schrock, Douglas. 1996. Transsexuals’ Narrative Construction of the “True Self”. Social Psychology Quarterly 59(3): 176–92.

McKeown, B., and D. Thomas. 1988. Q Methodology. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Mead, Walter Russell. 2001. Special Providence: American Foreign Policy and How It Changed the World. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Melman, Seymour. 1974. The Permanent War Economy: American Capitalism in Decline. New York: Touchstone.

Merelman, Richard M. 1989. On Culture and Politics in America: A Perspective from Structural Anthropology. British Journal of Political Science 19(4): 465–93.

Miller, John C. 1943. Origins of the American Revolution. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 1979.

Moeller, Robert G. 1996. War Stories: The Search for a Usable Past in the Federal Republic of Germany. American Historical Review 101(4): 1008–48.

Mumford, Lewis. 1970. The Myth of the Machine. Vol. 2 of The Pentagon of Power. New York: Harcourt Brace & World.

Nelson, Hilde Lindemann. 2001. Damaged Identities, Narrative Repair. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Nelson, Katherine, Daniela Plesa, and Sarah Henseler. 1998. Children’s Theory of Mind: An Experimental Interpretation. Human Development 41(1): 7–29.

Noonan, John Thomas. 2002. Persons and Masks of the Law: Cardozo, Holmes, Jefferson, and Wythe as Makers of the Masks. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Ochs, Elinor, and Lisa Capps. 1996. Narrating the Self. Annual Review of Anthropology 25: 19–43.

Ochs, Elinor, and Lisa Capps. 2001. Living Narrative: Creating Lives in Everyday Storytelling. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Orwell, George. 1949. Nineteen Eighty-Four. New York: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

O’Neill, William L. 1993. A Democracy at War: America’s Fight at Home and Abroad in World War II. New York: Free Press.

Paterson, Thomas G. 1996. United States Intervention in Cuba, 1898: Interpretations of the Spanish-American-Cuban-Filipino War. History Teacher 29(3): 341–61.

Peelo, Moira, and Keith Soothill. 2000. The Place of Public Narratives in Reproducing Social Order. Theoretical Criminology 4(2): 131–48.

Phillips, Kevin P. 1999. The Cousins’ Wars: Religion, Politics, and the Triumph of Anglo-America. New York: Basic Books.

Rehnquist, William H. 1998. All the Laws but One: Civil Liberties in Wartime. New York: Alfred A. Knopf.

Robertson, James Oliver. 1980. American Myth, American Reality. New York: Hill and Wang.

Robin, Ron. 2001. The Making of the Cold War Enemy: Culture and Politics in the Military-Intellectual Complex. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Roe, Emery. 1994. Narrative Policy Analysis: Theory and Practice. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Roelofs, H. Mark. 1976. Ideology and Myth in American Politics: A Critique of a National Political Mind. Boston: Little, Brown.

Sagan, Scott D. 1988. The Origins of the Pacific War. Journal of Interdisciplinary History 18(4): 893–922.

Schiffrin, Deborah, Deborah Tannen, and Heidi Ehernberger Hamilton, eds. 2001. The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. Malden, MA: Blackwell.

Schneider, Anne Larason, and Helen Ingram. 1997. Policy Design for Democracy. Lawrence: University Press of Kansas.

Schulhofer, Stephen J. 2002. The Enemy Within: Intelligence Gathering, Law Enforcement, and Civil Liberties in the Wake of September 11. New York: Century Foundation Press.

Schutz, Alfred. 1945. On Multiple Realities. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research 5(4): 533–76.

Schutz, Alfred. 1967. The Phenomenology of the Social World. Translated by G. Walsh and F. Lehnert. Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press.

Seldon, Sally, Gene Brewer, and Jeffry Brudney. 1999. Reconciling Competing Values in Public Administration: Understanding the Administrative Role Concept. Administration & Society 31(2): 171–204.

Sieminski, Greg. 1990. The Puritan Captivity Narrative and the Politics of the American Revolution. American Quarterly 42(1): 35–56.

Slotkin, Richard. 2000. Regeneration through Violence: The Mythology of the American Frontier, 1600–1860. Norman: University of Oklahoma Press.

Smith, Daniel M. 1956. Robert Lansing and the Formulation of American Neutrality Policies, 1914–1915. Mississippi Valley Historical Review 43(1): 59–81.

Sperry, Linda L., and Douglas E. Sperry. 1996. Early Development of Narrative Skills. Cognitive Development 11(3): 443–65.

Stever, James A. 1999. The Glass Firewall between Military and Civil Administration. Administration & Society 31(1): 28–49.

Stone, Deborah A. 1988. Policy Paradox and Political Reason. Glenview, IL: Scott, Foresman.

Stone, Deborah A. 1989. Causal Stories and the Formation of Policy Agendas. Political Science Quarterly 104(2): 281–300.

Sugiyama, Michelle Scalise. 2001. Food, Foragers, and Folklore: The Role of Narrative in Human Subsistence. Evolution and Human Behavior 22(4): 221–40.

Thompson, J. A. 1971. American Progressive Publicists and the First World War, 1914–1917. Journal of American History 58(2): 364–83.

Thompson, Michael, Richard Ellis, and Aaron Wildavsky. 1990. Cultural Theory. Boulder, CO: Westview Press.

Turner, Mark. 1996. The Literary Mind: The Origins of Thought and Language. New York: Oxford University Press.

Wahler, Robert G., and Frank D. Castlebury. 2002. Personal Narratives as Maps of the Social Ecosystem. Clinical Psychology Review 22(2): 297–314.

Waitzkin, Howard, Theron Britt, and Constance Williams. 1994. Narratives of Aging and Social Problems in Medical Encounters with Older Persons. Journal of Health and Social Behavior 35(4): 322–48.

Wajcman, Judy, and Bill Martin. 2002. Narratives of Identity in Modern Management: The Corrosion of Gender Difference. Sociology 36(4): 985–1002.

Weber, Max. 1978. Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology. Vol. 2. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Weick, Karl. 1995. Sensemaking in Organizations. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Weingast, Barry R. 1997. The Political Foundations of Democracy and the Rule of Law. American Political Science Review 91(2): 245–63.

White, Jay D. 1999. Taking Language Seriously: The Narrative Foundations of Public Administration Research. Washington, DC: Georgetown University Press.

Whitfield, Stephen J. 1996. The Culture of the Cold War. 2nd ed. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Wildavsky, Aaron. 1987. Cultural Theory of Responsibility. In Bureaucracy and Public Choice, edited by Jan-Erik Lane, 283–93. London: Sage Publications.

Wildavsky, Aaron. 1988. A Cultural Theory of Budgeting. International Journal of Public Administration 11: 651–77.

Yanow, Dvora. 2000. Conducting Interpretive Policy Analysis. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

Yanow, Dvora. 2003. Constructing “Race” and “Ethnicity” in America: Category-Making in Public Policy and Administration. Armonk, NY: M. E. Sharpe.

Yarwood, Dean and Dan Nimmo. 1976. Subjective Environments of Bureaucracy: Accuracies and Inaccuracies in Role-taking Among Administrators, Legislatures and Citizens. Western Political Quarterly 29(3): 337–52.

Zald, Mayer N. 1993. Organization Studies as a Scientific and Humanistic Enterprise: Toward a Reconceptualization of the Foundations of the Field. Organization Science 4(4): 513–28.

Zur, Ofer. 1987. The Psychohistory of Warfare: The Co-Evolution of Culture, Psyche and Enemy. Journal of Peace Research 24(2): 125–34.

[1] Known by various names—initially the National Security Study Group, then the Hart-Rudman Commission (after its cochairs), and most recently and formally, the U.S. Commission on National Securiry/21st Century—it issued its first report in 1999 (Hart, Rudman et al. 1999), a second in 2000 (Hart, Rudman et al. 2000), and a lengthy final report less than a year later (Hart, Rudman et al. 2001).

[2] Of course, other perspectives focus on neither nature nor nurture (e.g., the Malthusian and Hegelian models, which regard war as the product of forces unleashed by the logic of historical or economic development), and still others that combine the two positions by seeing war as the intentional cultivation of the aggressive qualities of human nature. For an overview of these various positions, see Dawson (1996).

[3] For contrasting views, see Manicas (1982) and Connor (1988).

[4] Keegan’s analysis is rooted in a critique of Clausewitzs theory of war but has itself been subject to criticism; see Herberg-Rothe (2001).

[5] For a personal perspective on the pathological impact of war, see Hedges (2002).

[6] We limit our discussion here to the emergence of narratives as a factor in social and administrative life, but its growing role as a methodological tool should also be noted. For example, narratives have been adopted as a means for testing policymaking theories (Bates et al. 1998, 2000; Levi 2002; Weingast 1997) and, especially among students of public administration, as a basis for identifying a wide range of social actions (in the form of expressed understandings by those involved), which can then be subjected to hermeneutical and other forms of interpretive analysis (Bailey 1992; Balfour and Mesaros 1994; Hummel 1991; Kelly and Maynard-Moody 1993; White 1999; Yanow 2000).

[7] For an overview of narrative psychology and related writings, see http://web.lemoyne.edu/~hevern/narpsych.html.

[8] For example, Hunt (1987) stresses the existence of a core ideology throughout U.S. history, and Mead (2001) elaborates four basic schools of thought that have dominated foreign policy making.

[9] Some explicit attention was paid to narratives during the 1980s (Kaplan 1986; Stone 1988, 109–16; Stone 1989), but these efforts were regarded by one observer as “fledgling” in the early 1990s (Zald 1993, 522–23).

[10] More recently, Bevir, Rhodes and colleagues have applied the narrative concept to traditions and beliefs of European governance and administrative cultures (Bevir and Rhodes 2001,2003; Bevir, Rhodes, and Weller 2003).

[11] The data were analyzed using PCQ software, version 1.41, developed by Michael Stricklin and Ricardo Almeida.