Kenneth Brower

The Danger of Cosmic Genius

How could someone as smart as Freeman Dyson be so dumb about the environment? The answer lies in his almost religious faith in the power of man and science to bring nature to heel.

One starry night 35 years ago, I drove the physicist Freeman Dyson through the British Columbia rain forest toward a reunion with his estranged son, George. The son, then 22, was a long-haired, sun-darkened, barefoot dropout with an uncanny resemblance to Thoreau. He had emigrated to Canada during the Vietnam War, and he lived 95 feet up a Douglas fir outside Vancouver. His passion was the aboriginal North American skin boat. In a workshop near his tree house, he had resurrected the baidarka, the kayak of the Aleutian Islands—a watertight second skin, lightweight and nimble, in which the Aleut hunter originally, and young George himself eventually, became a kind of sea centaur, half man and half canoe. The father, Freeman, was then and continues to be a professor of physics at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, New Jersey, employed there, as Einstein was before him, to think about whatever he finds interesting.

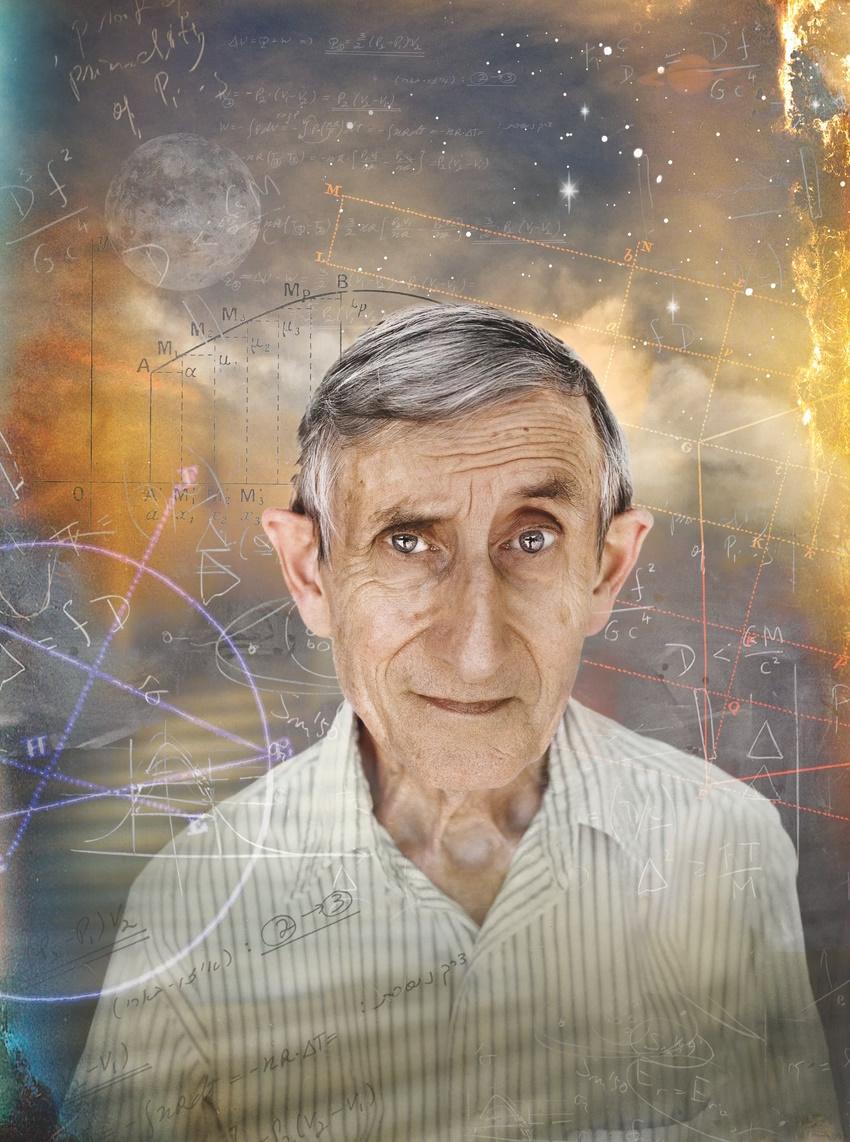

Freeman Dyson is one of those force-of-nature intellects whose brilliance can be fully grasped by only a tiny subset of humanity, that handful of thinkers capable of following his equations. His principal contribution has been to the theory of quantum electrodynamics, but he has done stellar work, too, in pure mathematics, particle physics, statistical mechanics, and matter in the solid state. He writes with a grace and clarity that is rare, even freakish, in a scientist, and his books, including Disturbing the Universe, Weapons and Hope, Infinite in All Directions, and The Sun, the Genome, and the Internet, have made a mark. Dyson has won the Lorentz Medal (the Netherlands) and the Max Planck Medal (Germany) for his work in theoretical physics. In 1996, he was awarded the Lewis Thomas Prize, which honors the scientist as poet. In 2000, he scored the Templeton Prize for exceptional contribution to the affirmation of life’s spiritual dimension—worth more, in a monetary way, than the Nobel.

The period of his career that Dyson remembers most happily, the endeavor during which he believes he learned the most, began the year after Sputnik. In 1958, he took a leave of absence from the Institute for Advanced Study and moved to La Jolla, California, where he joined Project Orion, a group of 40 scientists and engineers working to build a spacecraft powered by nuclear bombs. The Orion men believed that rocketry was hopeless as a means of settling the universe. Only nuclear power had sufficient bang to propel the requisite payloads into space. The team called the concept “nuclear-pulse propulsion.” From a hole at the center of a massive “pusher plate” at the bottom of the craft, atom bombs would be dropped at intervals and detonated. The shock wave and debris from each blast would strike the pusher plate, driving the ship heavenward on a succession of blinding fireballs. Shock absorbers the size of grain silos would cushion the cabin and crew, smoothing out the cataclysmic bumpiness of the ride.

To the layperson, this seems exactly the sort of contraption that Wile E. Coyote, in his efforts to overtake Road Runner, habitually straps on before self-immolation. But the layperson is wrong, apparently. Specialists in the effects of nuclear explosions saw no reason Orion would not work. The Advanced Research Projects Agency, the precursor to NASA, underwrote the project, then NASA took it on, and nuclear-pulse propulsion briefly held its own against the chemical rockets of Wernher von Braun. Dyson and his colleagues did not want to delegate; they intended to go bombing into space themselves. Their schedule had them landing on Mars by 1965 and Saturn by 1970.

The Volkswagen camper in which I was driving Freeman through the forest was a ’69, assembled the same year the Orion ship was supposed to thunder silently through space toward its 1970 rendezvous with Saturn. Like all VW minibuses of that vintage, mine was underpowered and prone to overheating. It was primitive transportation—internal combustion, just 57 horsepower—yet it got us down the road. Now and again, I checked the speedometer. We were averaging about 50 miles per hour, well under the 22 million mph that Freeman had hoped to coax from an interstellar spacecraft, but safe under the conditions. To the tinny pocketa pocketa of the four cylinders, I steered beneath the narrow swath of stars bounded by the crowns of conifers on either side.

The détente between the Dysons, father and son, was something I had helped mediate. This drive through the forest to unite them had the look of family counseling, but in fact it was fieldwork. I was gathering notes for my book The Starship and the Canoe, an account of the two men, their two vessels, and their two diverging views of the future.

Occasionally I stole a sideways glance at Freeman, who rode shotgun, very erect in the seat, staring in his unblinking way at the pavement ahead. It did not escape me that the black macadam in my headlights covered a road on Vancouver Island, British Columbia, Canada, Planet Earth. This was not extraterrestrial basalt on the dark side of Saturn’s moon Iapetus, which Freeman had especially wanted to visit, curious about why one side is black and the other white. This was not some haul road on Mimas, the innermost of the major moons of Saturn, a cratered satellite of water-ice just 115,000 miles from the planetary surface and favored by Freeman both as a place to provision and for its spectacular view of Saturn filling most of the sky. Back in 1958, Freeman had calculated the velocity increments required to deposit the Orion ship on various inner moons of Saturn and Jupiter, laying out the data in tables—but all for naught, in the end. The Limited Test Ban Treaty of 1963, with its prohibition of nuclear explosions in the atmosphere and outer space, killed Project Orion. President Kennedy’s signature effectively condemned Freeman to spend the rest of his life on this planet.

The forest was dark, the road twisty and narrow. It was two in the morning, and I had been driving all night. To keep awake at the wheel, I interviewed the physicist, in a desultory way. I was curious about his childhood in England. In 1943, as a teenager, he had been a mathematician with the Royal Air Force, calculating the ideal density for bomber formations raiding Germany; but his precociousness, I knew, had manifested itself much earlier than that. By the age of 6, his great interests had been mathematics and astronomy. He had been a little wizard, a wunderkind.

“It is said that the mental processes of a mathematical prodigy differ in no essential respect from those of ordinary folks who can handle more modest problems,” George Dyson had written—not Freeman’s tree-dwelling son, but Sir George Dyson, Freeman’s father, a composer and the director of the Royal College of Music. “The prodigy’s gift is the power of incessant concentration on more and more complicated mental calculations, until his brain can instantly recall the end products of the thousands of factors with which his mind has been busy.”

The prodigy in question, Freeman Dyson, now middle-aged, stared ahead, his incessant concentration on the road unbroken. He seemed mesmerized by the oncoming pavement, or by some idea or formulation glimpsed in the immateriality beyond the pavement. I asked him whether as a boy he had speculated much about his gift. Had he asked himself why he had this special power? Why he was so bright?

Dyson is almost infallibly a modest and self-effacing man, but tonight his eyes were blank with fatigue, and his answer was uncharacteristic.

“That’s not how the question phrases itself,” he said. “The question is: why is everyone else so stupid?”

In August 2009, Dyson appeared on the Charlie Rose show. His inimitable voice—somehow both diffident and firm, its original British accent overlaid by an American one—caught me in transit of my living room, and I pulled up a chair. Dyson has aged well. He has kept himself trim, not to say scrawny, and what he radiates in his 80s is a kind of wizened boyishness. I smiled at the familiar mannerisms. Freeman and his son, George, share an odd, cryptic style of chuckling in which the chin drops, the eyes get merry, and the shoulders shake with laughter, but no sound comes out.

Among intelligent nonexperts who have weighed in on climate change, Freeman Dyson has become, now that Michael Crichton is dead, perhaps our most prominent global-warming skeptic. Charlie Rose began his interview with questions about the climate. Dyson answered that he remained very skeptical about the dangers of global warming. He did not believe the pronouncements of the experts. He did not claim to be an expert himself, so he would not argue the details with anybody; he had not given much time to the issue and did not pretend to know the real answers, but what he knew for sure was that the global-warming experts did not know the answers, either.

Dyson did not deny that the world was getting warmer. What he doubted was the models of the climatologists, and the grave consequences they predicted, and the supposition that global warming is bad. “I went to Greenland myself, where the warming is most extreme,” he said. “And it’s quite spectacular, of course, what you see in Greenland. But what is also true is, the people there love it. The people there hope it continues. It makes their lives a lot more pleasant.”

Dyson argued that melting ice and the resulting sea-level rise is no cause for alarm. He said that the release of increasing volumes of carbon dioxide into the atmosphere is a very good thing, as it makes plants grow better. The important thing to remember, he said, is that the planet is warming mainly in places that are cold, and at night rather than during the day, so that the phenomenon is essentially making the climate more even, rather than just making everything hotter.

“Have we been kind to the planet?” Rose asked at one point.

“Yes. I would say, on the whole, yes.”

When Rose expressed surprise at this answer, the physicist backtracked slightly.

“No, the fact is, of course, we’ve done a lot of damage to the planet, but we also repair the damage. I grew up in England, and England was far more filthy then than it is now. We had the industrial revolution first, so England was much more polluted than the United States ever has been, and England now is quite comparatively clean. You can go to London and your collar doesn’t get black in one day.”

The question that phrases itself now, in the minds of many, is: how could someone as smart as Freeman Dyson be so dumb?

That humanity has been kind to the planet is not a possible interpretation, not even for a moment—certainly not for anyone who has been paying the slightest attention at any point in the 4,700 years of human history since Gilgamesh logged the cedar forest of the Fertile Crescent. That we repair our damage to the planet is a laughable assertion. It is true that the air is better now in London, and in Los Angeles too. Collars do blacken more slowly in both those places. Some rivers in the developed world are somewhat cleaner, as well: the Cuyahoga has not burned in many years. But it is also true that the Atlantic is afloat with tar balls, and that detached sections of fishnet and broken filaments of longline drift, ghost-fishing, in all our seas. Many of the large cities of Africa, South America, and Asia are megalopolises of desperate poverty ringed by garbage. Vast tracts of tropical rain forest, the planet’s most important carbon sink, disappear annually, burned or logged or mined. Illegal logging is also ravaging the slow-growing boreal forests of Siberia. The ozone hole over Antarctica continues to open every southern spring, exposing all life beneath to unfiltered ultraviolet rays. African wildlife is in precipitous decline. Desertification continues in the Sahel, turning that semi-arid zone into just more Sahara. Frogs are vanishing everywhere. We are in the middle of a mass die-off, the “sixth extinction,” this one caused not by volcanoes or collisions with asteroids and comets, as before, but by mankind—with species disappearing, according to the International Union for Conservation of Nature, at 1,000 to 10,000 times the rate prevalent over the 65 million years since the previous great extinction. That one was caused by an asteroid strike—the cataclysm that ended the Cretaceous Period, killing off the dinosaurs and nearly everything else alive. It is wonderful that Dyson, in his trips home to London, finds less soot on his collar, but this is perhaps not the best measure of planetary health.

Many of Dyson’s facts on global warming are wrong, as the scientists who have done actual research on the subject point out, but more disconcerting is the selective way he gathers his information and the peculiar conceptual framework into which he inserts it.

It is true that plants grow better with increases in carbon dioxide. (Photosynthesis is the conversion of carbon dioxide and sunlight into organic compounds, so the more CO2 and sunlight, the better, up to a point.) If a plant’s survival depended only on its metabolism—if all it had to do was photosynthesize—then increased CO2 in the atmosphere might indeed be a good thing. But plants happen to grow in these little universes we call ecosystems, where they are sustained by complex webs of interdependency with fungi, microbes, animals, and other plants. Much of this mutually dependent life is adapted to narrow temperature and rainfall regimes, and these biomes are collapsing everywhere.

Plants do grow better with increased CO2, but not when deprived of water. Water is a vanishing commodity in the American West, where I live, and where, like the Australians and Sudanese and many others, we are enduring a succession of increasingly prolonged and severe droughts. Drought is a paleontological fact in the American West, but the latest desiccations have a new signature, and my region’s climatologists, hydrologists, foresters, and water managers are nearly unanimous in their conviction that what we are seeing now is climate change, the anthropogenic kind, a consequence of too much CO2 and other greenhouse gases. Drought-induced stress increases plants’ susceptibility to disease, and tree diseases are epidemic now in my home landscape and elsewhere. Plants grow better with increased CO2, but not when they are dead snags.

The planet, Dyson assured Rose, is warming mainly in places that are cold; it is not getting hotter so much as the climate is evening out. This is a peculiar analysis. The fact is that the planet is getting hotter, by small but enormously consequential increments. That the warming is most pronounced in cold places is true, but this is no consolation to the creatures that live there. I recently returned from reporting on diminishing sea ice and the decline of penguin populations and krill stocks on the Antarctic Peninsula, the western side of which, over the past half century, has been warming at five times the world’s average rate. I feel obligated to put in a word for the elephant seals, fur seals, crabeater seals, leopard seals, whales, penguins, albatrosses, petrels, and other members of that cold-adapted, krill-dependent fauna. Dyson’s implication that an evening out of global temperatures might somehow be a neutral or beneficial phenomenon is astounding. Temperature differentials at different latitudes and altitudes are a prime driver of planetary weather. Weather patterns, needless to say, are full of consequence not just for penguins and seals, but for all life everywhere.

How could someone as brilliant as Freeman Dyson take the positions he does on global warming and other environmental issues?

I have a number of theories.

Contrariness

A contrarian nature, by clearing the field of received wisdom, speeds original thought. Physicists, astronomers, scholars of every stripe, have always been charmed by the counterintuitive—and why not, as it so often turns out to be right? Dyson’s present devotion to a set of contrary, counterintuitive, even counter-obvious ideas on climate change is hardly a novel stance for him, only a little more stubborn than usual. It is clear to me that he has been stung by the criticism of his musings on global warming, and is digging in his heels.

He Doesn’t Really Mean It

Dyson is prone to conducting thought experiments, and will often slip into one without warning. It is not always apparent when he is inhabiting some Dalí-esque experimental landscape between his ears and when he has touched down on Earth. Even his old colleagues from Project Orion, men working with him on an exceedingly far-out concept, were sometimes unsure.

“Freeman’s last lecture, toward the end of his stay, was a marvelous thing,” an Orion engineer named Brian Dunne told me. “He decided to take Orion to the ultimate. It was funnier than hell. First I didn’t believe it. Then I did. Then I didn’t. It was just so outlandish, beyond anything we had ever envisioned before.”

What Dyson proposed was a 240-million-ton ark with a pusher plate 90 miles in diameter and powered by hydrogen bombs. It was a modest vessel, really, the smallest possible practical version of a class of 6,000-miles-per-second starships he had dreamed up, dreadnoughts capable of crossing our solar system in a month. His starship would be slow off the starting blocks, with a zero-to-6,000-mps time of 30 years, but then it would really get rolling. Dyson addressed small details, like questions of plumbing. Nuclear-pulse propulsion, even in the small, pokey, atom-bomb-powered version of the Orion ship designed to tool around this solar system, required that each nuclear bomb be packaged in propellant—some material that, when vaporized into a plasma stream by the explosion, would strike the pusher plate and provide the necessary kick. For his starship, Dyson proposed recycling the feces of the astronauts as propellant. Riding a thermonuclear shit storm, his ark would carry several thousand colonists to Alpha Centauri on a 150-year voyage.

“Was he serious?” I asked Dunne.

“No,” said the engineer. He laughed merrily at the memory. Then suddenly he stopped. His face went thoughtful. “Well, you never know,” he said. “You can’t tell with Freeman. You have to be cautious.”

“Was he serious?” I asked Ted Taylor several days later. Taylor, an expert in the miniaturization of nuclear bombs, was the head of Project Orion and Dyson’s closest friend on the team.

“I don’t think so,” Taylor said, after several moments of hesitation. “In his characteristic way, he wanted to push something to the limit. H-bombs, per unit of energy, are a lot cheaper than A-bombs. They’re also a lot hotter, a lot more energetic.”

Dyson himself, when I put the same question to him, was dismissive. “The starship was like an existence theorem in math,” he said. “It was to prove if you could do it. I never really believed in it.”

Educated Fool

Einstein could not make change, according to the lore; the bus drivers of Princeton had to pick out his nickels and quarters for him. We dimmer bulbs love to seize on tales like this. We are comforted by the notion of the educated fool. It seems only right that some leveling principle should deprive the geniuses among us of common sense, street smarts, mother wit. It is tempting to try explaining Dyson in this way.

Having myself grown up in Berkeley, where Nobel laureates are a dime a dozen, I certainly know the syndrome: the mismatched socks, the spectacles repaired with duct tape, the forgotten anniversaries and missed appointments, the valise left absentmindedly on the park bench. Yet hometown experience did not prepare me completely for Dyson. In my interviews with the physicist, he would sometimes depart the conversation mid-sentence, his face vacant for a minute or two while he followed some intricate thought or polished an equation, and then he would return to complete the sentence as if he had never been away. I have observed similar departures in other deep thinkers, but never for nearly so long.

“He’d just disappear,” George Dyson remembers. George was just 5 when his father moved the family west to La Jolla for the Orion work, but he was a watchful child, and it was his impression that the varied challenges of designing the spacecraft only intensified his father’s preternatural powers of concentration. Freeman’s body occupied the chair in his study, but in every other sense, he was gone.

Many years after Orion, in La Jolla, with the physicist as my guide, I tried to drive us to a restaurant that Dyson knew from his spaceship days. We overshot it by a mile going east, because Dyson got lost in some long chain of cogitation, and then we overshot it going west, and then overshot it going east again. Each time, Dyson would apologize, but remorse did not save him from falling again, just a few yards down the road, into some black pothole of cerebration. Our course to the restaurant, which we finally reached, half-starved, was the sort of oscillation you might chart by affixing a pencil to the tip of a pendulum as it loses momentum. (I chose not to interview Dyson afresh for this essay, not from any impatience with his mental walkabouts, but because what I wanted to address here were his public statements on climate change, the environment, and technology.)

If this seems to support a nutty-professor explanation for Dyson, then the testimony of his colleagues tends to argue the other way. Among his former co-workers, Dyson is famous for a kind of elevated common sense.

The Orion engineer Brian Dunne, a nuts-and-bolts sort of guy, was doubtful at first about Dyson’s pragmatism. “I had had dealings with lots of very eminent theorists,” he told me. “I’d found huge gaps in their knowledge of things, particularly experimental problems—how to put something together that works. When I realized Freeman really is a fine engineer, I was astounded. He knows electrical engineering, mechanical engineering, structural. That’s unnerving, in a theoretical physicist with the eminence that he enjoys. His contributions to quantum electrodynamics are classics. They are beautiful pieces of work—poetry in physics, if you will. To see the same man do an analysis of the pusher-plate motion, and the shock-absorber motion, putting in the damping coefficients, and the strengths and stresses, and getting it all right—that’s unnerving.”

Dyson eludes stereotype. The nutty-professor hypothesis, as applied to him, remains a work in progress.

Old Age

Some critics have suggested that at his advanced age, Dyson is “out of his beautiful mind,” as one put it. On most subjects, Dyson’s recent writings and lectures give no hint that he is slipping. He puts his words and thoughts together as lucidly as ever. When a mind starts out with all the excess computing power that Dyson’s did, it generally has enough millions of spare neurons to carry the owner into his 90s and across the finish line in style. I would venture that if Dyson’s mind is lost, or just wandering far afield in its idiosyncratic way, then that detour happened long ago, and age has nothing to do with it.

“First I have to clear away a few popular misconceptions about space as a habitat,” he said, lecturing in London in 1972, when he was only 48. “It is generally considered that planets are important. Except for Earth, they are not. Mars is waterless, and the others are, for various reasons, basically inhospitable to man. It is generally considered that beyond the sun’s family of planets there is absolute emptiness extending for light-years until you come to another star. In fact, it is likely that the space around the solar system is populated by huge numbers of comets, small worlds a few miles in diameter, rich in water and the other chemicals essential to life.”

The comets contain everything we need except warmth and air, he promised, and he predicted that biological engineering would make up for these two shortcomings: bio-engineers would design trees that function in airless space and thus make the comets habitable. Then he turned to potential habitations much closer at hand:

“There’s very good news from the asteroids. It appears that a large fraction of them, including the big ones, are actually very rich in H2O. Nobody imagined that. They thought they were just big rocks … It’s easier to get to an asteroid than to Mars, because the gravity is lower and landing is easier. Certainly the asteroids are much more practical, right now. If we start space colonies in, say, the next 20 years, I would put my money on the asteroids.”

The real-estate mantra “Location, location, location” applies to the asteroids, as it does everywhere else. The near-Earth asteroids seem particularly prime. And Dyson has had his eye on them for a very long time.

Eros, the first near-Earth asteroid discovered and the second-largest of them all, is promising terrain. Eros is a Mars-crosser. It is named for the god of love. Shaped something like a sweet potato, or a cashew, it is 21 miles long by eight wide by eight deep—somewhat bigger, astronomers think, than the asteroid that dug the Chicxulub crater out of the Yucatán Peninsula and wiped out the dinosaurs. The Erotic climate is not perfect. Temperatures rise to 212 degrees Fahrenheit in daytime and drop to minus 238 degrees at night. Gravity there is unsettled, fluctuating wildly depending on where you stand. But Eros does have redeeming features. More gold, silver, aluminum, zinc, and other precious metals lie near its surface, in theory, than exist in all the Earth’s crust. Eros was the first asteroid on which a spacecraft ever landed. In 2001, after orbiting Eros for a year, the robotic probe Shoemaker set down on the rubble of the Erotic surface. The probe sits there still. For future colonists, it may prove useful—a historical monument, perhaps, or just scrap.

Dyson has been thinking about Eros for most of his life, and in his imagination, he anticipated the Shoemaker’s landing by nearly 70 years. Among the relics of his childhood is a blue exercise book, its cover reading, in fountain pen, Sir Phillip Roberts’s Erolunar Collision. Written by F. J. Dyson, aged 8–9, 1932–1933. The story opens:

Chap. I. The Great Discovery

Sir Phillip Roberts, director of the British South-African Astronomical Society, was sitting in his study, calculating facts about Eros, the minor planet which revolves at between 100,000,000 and 180,000,000 miles from the sun, and which sometimes approaches within 13,000,000 miles of the Earth; He had just discovered that Eros was going to come exceptionally near to the Earth in 10 years and 291 days, and might, by some luck, be caught within the Earth’s attraction. He quickly went off and told one of the members of the society, Major Forbes, who was rather a friend of his, the good news.

There is very little action in “Sir Phillip Roberts’s Erolunar Collision,” but a great deal of calculating. (“This set everybody calculating exactly where the Moon would be at that time, and, wonder of wonders!, the Moon was found to be due at the exact spot where Eros would be in 10 years, 285 days’ time; or, to put it more shortly, Eros would collide with the Moon.”) Sir Phillip Roberts and his astronomer colleagues, having determined that Eros will hit the moon, set about designing a craft that will take them there in time to observe the crash. (“‘Well,’ said Sir Phillip, ‘we are here to converse about our projectile inside which we are to ascend to our only satellite; what size do you prepose?’”)

My point here is not that this fictional projectile eerily foreshadows Dyson’s work on the Orion spaceship—though foreshadow it certainly does. My point is that the physicist was not in his 80s and fading when he lost his beautiful mind in the asteroids. He was just 8 years old.

Collision of Faiths

In the June 12, 2008, New York Review of Books, in an essay called “The Question of Global Warming,” Dyson reviews books on that subject by William Nordhaus and Ernesto Zedillo. He writes,

All the books that I have seen about the science and economics of global warming, including the two books under review, miss the main point. The main point is religious rather than scientific. There is a worldwide secular religion which we may call environmentalism, holding that we are stewards of the earth.

After halfheartedly endorsing this idea of stewardship, Dyson goes on to lament that “the worldwide community of environmentalists—most of whom are not scientists”—have “adopted as an article of faith the belief that global warming is the greatest threat to the ecology of our planet.” This is a tragic mistake, he says, for it distracts from the much more serious problems that confront us.

Environmentalism does indeed make a very satisfactory kind of religion. It is the faith in which I myself was brought up. In my family, we had no other. My father, David Brower, the first executive director of the Sierra Club and the founder of Friends of the Earth, could confer no higher praise than “He has the religion.” By this, my father meant that the person in question understood, felt the cause and the imperative of environmentalism in his or her bones. The tenets go something like this: this living planet is the greatest of miracles. We Homo sapiens, for all the exceptionalism of our species, are part of a terrestrial web of life and are utterly dependent upon it. Nature runs the biosphere much better than we do, as we demonstrate with our ham-handedness each time we try. The arc of human history is unsustainable. We cannot go on destroying natural systems and expect to survive.

Freeman Dyson does not have the religion. He has another religion.

“The main point is religious rather than scientific,” he writes, yet never acknowledges that this proposition cuts both ways, never seems to recognize the extent to which his own arguments proceed from faith. Environmentalism worships the wisdom of Nature. Dysonism worships the indomitable ingenuity of Man. Dyson often suggests that science is on his side, but lately little of his popular exposition on planetary matters has anything to do with science. His futurism is solidly in the tradition of Jules Verne, as it has been since he was 8 and wrote “Sir Phillip Roberts’s Erolunar Collision.” On the question of global warming, the world’s climatologists and scientific institutions are almost unanimously arrayed against him. On his predictions for the future of ecosystems, ecologists beg to differ. Dysonian proclamations like “Now, after three billion years, the Darwinian interlude is over” are not science. (His argument here, which is that cultural evolution has replaced the Darwinian kind, is at best premature and at worst the craziest kind of hubris.)

The two faiths collided in the Dyson family.

The schism between Freeman and his son, George, began not with any debate about asteroids versus redwoods, but over marijuana. In his early teens, George left his father’s house in Princeton to spend his summers in Northern California, visiting his mother, the mathematician Verena Huber-Dyson. He and his mother hiked the Sierra Nevada on Sierra Club trips; in those mountains, and later in Colorado, he came to know my sister, Barbara, a teenage cook for the club. He also hiked the Haight of the late ’60s, when rebellion and cannabis smoke were thickest in that neighborhood, and he made contacts among the flower children. Back home in New Jersey, he became the target of an investigation, suspected by narcotics officers of being the main weed dealer at his high school. His room was raided and some seeds were found. He was handcuffed during class and taken to jail. Freeman chose not to bail him out. In his week behind bars, George read the dictionary up to the letter M before his sister Esther helped spring him. He was shaken by the experience, and his relationship with his father was broken.

At 16, George went west for good. He matriculated at the University of California, living surreptitiously in the Berkeley marina on a small sailboat. From time to time, he visited my family’s home in the Berkeley hills. He fell under the influence of my father. (And vice versa. My father, struck by George’s ambition “to find freedom, without taking it from someone else,” used the line often in his speeches.)

George did not find freedom at the University of California. After a short period of spotty attendance, he lit out for Canada. In Vancouver, he and his half-sister Katarina, who had preceded him north, became intimates of the founding fathers of Greenpeace. George had gone over to the other side, joining the secular religion of environmentalism, but his faith was noninstitutional, personal, quixotic. He began designing and building a succession of kayaks that would culminate in his equivalent, or his antidote, to his father’s starship: a giant baidarka, the Mount Fairweather, 48 feet long, the biggest kayak in history, with six manholes for paddlers and an outrigger platform on which a seventh crewman sculled with a sweep oar. In this behemoth, as in his smaller kayaks, George paddled resolutely in the opposite direction from his father, back toward the Stone Age.

After five years of estrangement, both father and son relented. In my Volkswagen camper, aboard a ferry pulling into Vancouver Island, Freeman scanned the shore for his son. “The big moment,” he said. George’s 14-year-old sister, Emily, who had been asleep in the back, searched too. I spotted George first, walking down to the slip in a knit cap and fisherman’s oilskins. “You see him? Where is he?” Freeman asked. I pointed, and Freeman stared. “Yes, there’s the man.” He leaned out the window and waved. We pulled up beside George, one of the last cars off the ferry. Beaming broadly, father and son shook hands.

We spent the next few days camping in the forests of Swanson and Hanson islands and paddling the straits and channels thereabouts. Freeman was impressed by George’s woodcraft and boatmanship; he admired the man his son had become. Fascinated by George’s friends, he informed these backwoodsmen that they had just the sort of skills and temperament required of space colonists, and in a playful way he tried to recruit them.

For 35 years, now, Freeman and George Dyson have been reconciled personally; and ideologically too, the gap between them has narrowed.

George has long since come down from his tree house. Even while he lived up there, the flying squirrels were stealing his insulation to line their own nests, and today, three decades after he abandoned his pied-à-l’air, the squirrels have stripped the place bare. There is no returning. George now lives in Bellingham, Washington. In 1989, he bought a derelict bar on the waterfront, Dick’s Tavern, and converted it to a kayak-building shop. He drifted into writing. His first book, Baidarka, is a history of the Aleut kayak and an account of his resurrection of that vessel. His second book, Darwin Among the Machines, is a history of the luminaries of the information revolution, and as such signals a turn back toward the world of his father. His third, Project Orion, is a history of his father’s spacecraft. His next, Turing’s Cathedral, he conceives as “a creation myth for the digital universe.”

This July in Dick’s Tavern, George was hard at work finishing Turing’s Cathedral, trying to meet an August deadline for delivery of the manuscript. Mounted on the tavern wall, running the length of the bar, was the skeletal frame for one of his Aleut-style kayaks, 25 feet long, with three manholes for paddlers. Beneath this unfinished vessel, the pages of Turing’s Cathedral were laid out in neat stacks along the bar surface, about two chapters per bar stool. The inspiration for the book seems to have come in 1961, when George was 8 and he and a small band of comrades—the sons of field theorists at the Institute for Advanced Study—stumbled upon an old barn on the institute’s campus. Stored inside, along with old farm equipment, were the relics of the antediluvian electronic computer on which John von Neumann conducted his pioneering experiments in artificial intelligence. In Darwin Among the Machines, in a chapter called “Rats in a Cathedral,” George describes how he and his buddies, with wrenches and screwdrivers, lobotomized von Neumann’s machinery. “We blindly dissected the fossilized traces of electromechanical logic out of which the age of digital computers first took form.”

Freeman, for his part, seems to have settled more deeply into his own secular religion, becoming a prominent evangelist of the faith. He is in such a scientific minority on climate change that his views are easy to dismiss. In the worldview underlying those opinions, however—in the articles of his secular faith—he makes a kind of good vicar for a much more widely accepted set of beliefs, the set that presently drives our civilization. The tenets go something like this: things are not really so bad on this planet. Man is capable of remaking the biosphere in a coherent and satisfactory way. Technology will save us.

In “Our Biotech Future,” a 2007 essay in The New York Review of Books, Dyson writes,

Domesticated biotechnology, once it gets into the hands of housewives and children, will give us an explosion of diversity of new living creatures … New lineages will proliferate to replace those that monoculture farming and deforestation have destroyed. Designing genomes will be a personal thing, a new art form as creative as painting or sculpture. Few of the new creations will be masterpieces, but a great many will bring joy to their creators and variety to our fauna and flora.

He goes on to predict that computer-style biotech games will be played by children down to kindergarten age, games in which real seeds and eggs are manipulated, the winner being the kid who grows the prickliest cactus or the cutest dinosaur. “These games will be messy and possibly dangerous. Rules and regulations will be needed to make sure that our kids do not endanger themselves and others.”

One always searches Dyson’s prognostications for hints of irony. Surely this vision of powerful biotechnology in the hands of housewives and kindergartners—godlike power exercised by human amateurs as amusement—is a Swiftian suggestion, Dyson’s try at “A Modest Proposal.” But nowhere in this essay will you find a single sly wink. Dyson is serious.

How is it possible to misapprehend so profoundly so much about how the real world works? In the space of these few sentences, Dyson has misjudged the desperation of housewives, the dark anarchy in the hearts of kindergarten kids, the efficacy of rules and regulations, and, most problematic of all, the deliberation with which Darwinian evolution shapes the authentic organisms of Creation, assuring the world of plants and animals that make sense in their respective biomes.

In this same essay, Dyson writes,

We are moving rapidly into the post-Darwinian era, when species other than our own will no longer exist, and the rules of Open Source sharing will be extended from the exchange of software to the exchange of genes.

When species other than our own will no longer exist.

Has anyone else proposed such a future? Does anyone else want to live in it? Has anyone suggested how such a future (without pollinators, nitrogen-fixers, decomposers, without microbes in the soil and bacteria in the gut) would be possible? For the unifying impulse of the physicist, the idea might be satisfying—just one species—but for the diversifying impulse of the biologist, there could be nothing more chilling than this endorsement of mass biocide, Dyson’s cheerful embrace of extinction for everything but us.

“Environmentalism has replaced socialism as the leading secular religion,” Dyson complains in his 2008 New York Review of Books essay on global warming. This is far too gloomy an assessment. The secular sect on the rise at the moment is Dyson’s own. A 2009 Pew poll found that only 57 percent of Americans believe there is solid evidence that the world is getting warmer, down 20 points from three years before. In response to climate change, we have seen a proliferation of proposals for geo-engineering solutions that are Dysonesque in scale and improbability: a plan to sow the oceans with iron to trigger plankton blooms, which would absorb carbon dioxide, die, and settle to the sea floor. A plan to send a trillion mirrors into orbit to deflect incoming sunlight. A plan to launch a fleet of robotic ships to whip up sea spray and whiten the clouds. A plan to mimic the planet-cooling sulfur-dioxide miasmas of explosive volcanoes, either by an artillery barrage of sulfur-dioxide aerosol rounds fired into the stratosphere or by high-altitude blimps hauling up 18-mile hoses.

None of these projects will happen, fortunately. They promise side effects, backfirings, and unintended consequences on a scale unknown in history, and we lack the financial and political wherewithal, and the international comity, to accomplish them anyway. What is disquieting is not their likelihood, but what they reveal about the persistence of belief in the technological fix. The notion that science will save us is the chimera that allows the present generation to consume all the resources it wants, as if no generations will follow. It is the sedative that allows civilization to march so steadfastly toward environmental catastrophe. It forestalls the real solution, which will be in the hard, nontechnical work of changing human behavior.

What the secular faith of Dysonism offers is, first, a hypertrophied version of the technological fix, and second, the fantasy that, should the fix fail, we have someplace else to go.

Freeman Dyson is a national and international treasure. His career demonstrates how a Nobel-caliber mind, in avoiding the typical laureate’s dogged obsession with a single problem, can fertilize many fields, in his case particle physics and astrophysics, biology and exobiology, mathematics, metaphysics, the history of science, religion, disarmament theory, literature, and even medicine, as Dyson was a co-inventor of the TRIGA reactor, which produces medical isotopes.

Dyson, clearly a busy man, was extraordinarily generous with his time with me at an early stage of my career. His allowing me to be present at an intimate family affair—his reunion with George—provided the climax and denouement for my best and most successful book. In the field, Dyson was an amusing and never-boring companion. Never have I had a relationship of such asymmetrical understanding. Dyson always got the drift of my ideas and sentences before I was three or four words into them, but the converse was not true. When the physicist spoke of his own pet subjects—quantum electrodynamics, say, or certain characteristics of the event horizon in the vicinity of black holes—I had no idea what he was talking about. Dyson is a discoverer of, and fluent in, the mathematics by which the fundamental laws of the universe operate, and in that language I am illiterate.

Long ago I asked Ted Taylor, the chief of Project Orion, what quality distinguished Dyson from the other Orion men. “Freeman’s gift?” said Taylor. “It’s cosmic. He is able to see more interconnections between more things than almost anybody. He sees the interrelationships, whether it’s in some microscopic physical process or in a big complicated machine like Orion. He has been, from the time he was in his teens, capable of understanding essentially anything that he’s interested in. He’s the most intelligent person I know.”

This is how Dyson strikes me too. But the operative word for me is cosmic. The word terrestrial would not apply. In taking the measure of the universe, Dyson fails only in his appraisal of the small, spherical piece of the cosmos under his feet. Or so it seems to me. For whatever reason, he is emotionally incapable of seeing the true colors of the rampant ingenuity of our species and calculating where our cleverness, as opposed to our wisdom, is taking us.