Kim Murphy

Unabomber still writing after 14 years in prison

One small publisher, at least, thinks his apocalyptic messages are worth pondering.

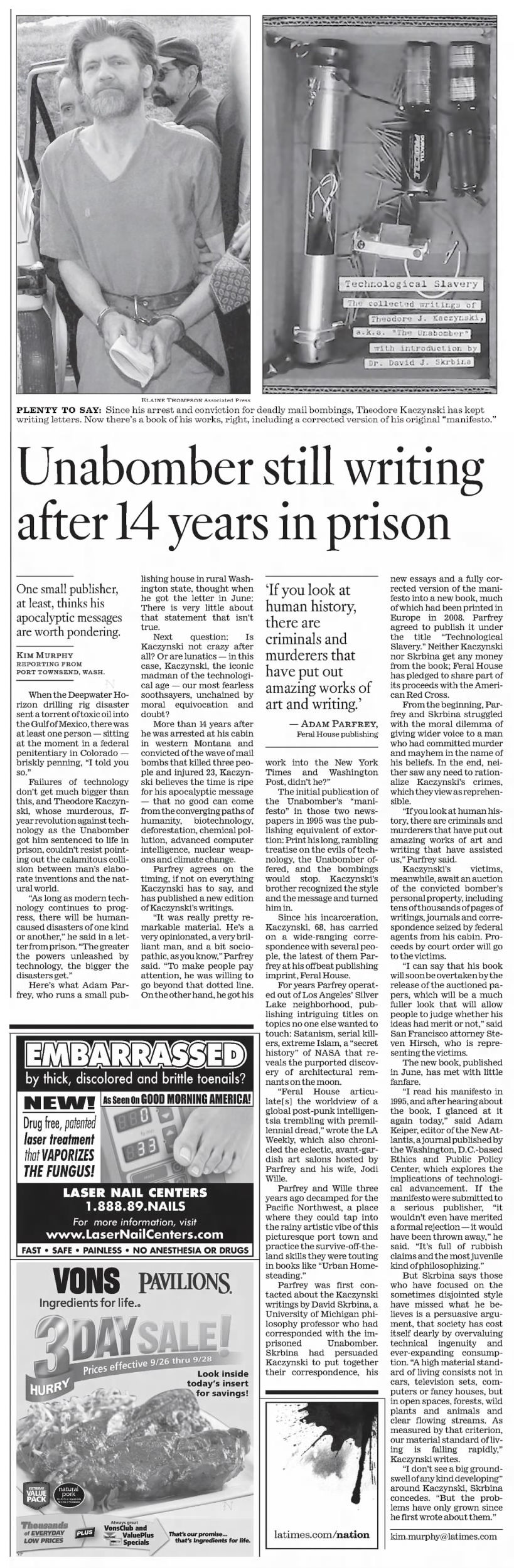

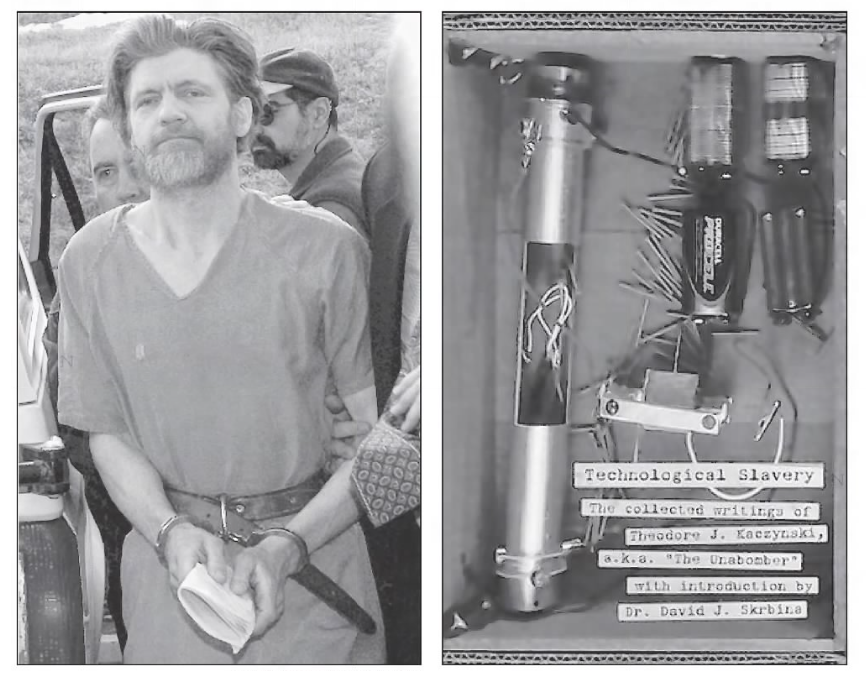

PLENTY TO SAY: Since his arrest and conviction for deadly mail bombings, Theodore Kaczynski has kept writing letters. Now there's a book of his works, right, including a corrected version of his original "manifesto."

When the Deepwater Horizon drilling rig disaster sent a torrent of toxic oil into the Gulf of Mexico, there was at least one person — sitting at the moment in a federal penitentiary in Colorado — briskly penning, “I told you so.”

Failures of technology don’t get much bigger than this, and Theodore Kaczynski, whose murderous, 17-year revolution against technology as the Unabomber got him sentenced to life in prison, couldn’t resist pointing out the calamitous collision between man’s elaborate inventions and the natural world.

“As long as modern technology continues to progress, there will be human-caused disasters of one kind or another,” he said in a letter from prison. “The greater the powers unleashed by technology, the bigger the disasters get.”

Here’s what Adam Parfrey, who runs a small publishing house in rural Washington state, thought when he got the letter in June: There is very little about that statement that isn’t true.

Next question: Is Kaczynski not crazy after all? Or are lunatics — in this case, Kaczynski, the iconic madman of the technological age — our most fearless soothsayers, unchained by moral equivocation and doubt?

More than 14 years after he was arrested at his cabin in western Montana and convicted of the wave of mail bombs that killed three people and injured 23, Kaczynski believes the time is ripe for his apocalyptic message —that no good can come from the converging paths of humanity, biotechnology, deforestation, chemical pollution, advanced computer intelligence, nuclear weapons and climate change.

Parfrey agrees on the timing, if not on everything Kaczynski has to say, and has published a new edition of Kaczynski’s writings.

“It was really pretty remarkable material. He’s a very opinionated, a very brilliant man, and a bit sociopathic, as you know,” Parfrey said. “To make people pay attention, he was willing to go beyond that dotted line. On the other hand, he got his work into the New York Times and Washington Post, didn’t he?” The initial publication of the Unabomber’s “manifesto” in those two newspapers in 1995 was the publishing equivalent of extortion: Print his long, rambling treatise on the evils of technology, the Unabomber offered, and the bombings would stop. Kaczynski’s brother recognized the style and the message and turned him in.

Since his incarceration, Kaczynski, 68, has carried on a wide-ranging correspondence with several people, the latest of them Parfrey at his offbeat publishing imprint, Feral House.

For years Parfrey operated out of Los Angeles’ Silver Lake neighborhood, publishing intriguing titles on topics no one else wanted to touch: Satanism, serial killers, extreme Islam, a “secret history” of NASA that reveals the purported discovery of architectural remnants on the moon.

“Feral House articulate[s]the worldview of a global post-punk intelligentsia trembling with premillennial dread,” wrote the LA Weekly, which also chronicled the eclectic, avant-gardish art salons hosted by Parfrey and his wife, Jodi Wille.

Parfrey and Wille three years ago decamped for the Pacific Northwest, a place where they could tap into the rainy artistic vibe of this picturesque port town and practice the survive-off-the-land skills they were touting in books like “Urban Homesteading.”

Parfrey was first contacted about the Kaczynski writings by David Skrbina,a University of Michigan philosophy professor who had corresponded with the imprisoned Unabomber. Skrbina had persuaded Kaczynski to put together their correspondence, his new essays and a fully corrected version of the manifesto into a new book, much of which had been printed in Europe in 2008. Parfrey agreed to publish it under the title “Technological Slavery.”Neither Kaczynski nor Skrbina get any money from the book; Feral House has pledged to share part of its proceeds with the American Red Cross.

From the beginning, Parfrey and Skrbina struggled with the moral dilemma of giving wider voice to a man who had committed murder and mayhem in the name of his beliefs. In the end, neither saw any need to rationalize Kaczynski’s crimes, which they view as reprehensible.

“If you look at human history, there are criminals and murderers that have put out amazing works of art and writing that have assisted us,” Parfrey said.

Kaczynski’s victims, meanwhile, await an auction of the convicted bomber’s personal property, including tens of thousands of pages of writings, journals and correspondence seized by federal agents from his cabin. Proceeds by court order will go to the victims.

“I can say that his book will soon be overtaken by the release of the auctioned papers, which will be a much fuller look that will allow people to judge whether his ideas had merit or not,” said San Francisco attorney Steven Hirsch, who is representing the victims.

The new book, published in June, has met with little fanfare.

“I read his manifesto in 1995, and after hearing about the book, I glanced at it again today,” said Adam Keiper, editor of the New Atlantis, a journal published by the Washington, D.C.-based Ethics and Public Policy Center, which explores the implications of technological advancement. If the manifesto were submitted to a serious publisher, “it wouldn’t even have merited a formal rejection — it would have been thrown away,” he said. “It’s full of rubbish claims and the most juvenile kind of philosophizing.”

But Skrbina says those who have focused on the sometimes disjointed style have missed what he believes is a persuasive argument, that society has cost itself dearly by overvaluing technical ingenuity and ever-expanding consumption. “A high material standard of living consists not in cars, television sets, computers or fancy houses, but in open spaces, forests, wild plants and animals and clear flowing streams. As measured by that criterion, our material standard of living is falling rapidly,” Kaczynski writes.

“I don’t see a big groundswell of any kind developing” around Kaczynski, Skrbina concedes. “But the problems have only grown since he first wrote about them.”

kim.murphy@latimes.com