Kimberly Croswell

Putting the word out there

The sub.Media collective, Indigenous resurgence, and prefigurative politics in the parallel present

Introduction: Means-ends unity and the parallel present

Video activism on the broadband: The sub.Media collective

Pushing the envelope with an aesthetic vanguard and the coming community

Solidarity Politics and the Sparking of a Movement

Mobilising solidarity and action: sub.Media supporting frontline resistance

Situational awareness backgrounder

Abstract

This article examines prefigurative politics within a heterotopic parallel present activated by the contributions of the anarchist video collective sub.Media. Activists seeking to ‘plug into’ the resistance can find information, inspiration, and motivation by engaging with sub.Media’s video originals and remixes. They are part of a vital activist ecosystem that encourages participation in prefigurative relationship building fomenting shared anti-authoritarian values. Through their connections with Indigenous and activist communities, sub.Media demonstrates how Indigenous warriors and anarchists may combine forces to mobilise generative resistance to colonialism in the thrust of Indigenous resurgence.

Introduction: Means-ends unity and the parallel present

Prefigurative politics and resistance are intertwined. Activating the present to create a shared future necessitates challenging conditions of injustice, inequality, and ignorance while simultaneously planting seeds in preparation for days to come. Central to anarchist prefigurative politics is the insistence that the means of organizing align with the ends desired, thus ensuring generative outcomes in continuity with anarchism’s societal vision (Goldman, 1924/1983: 402). However, to succeed, anarchists understand means-ends unity must encompass more than a present-future continuum: it demands acting in a heterotopic parallel present across relationship networks founded on egalitarian social values, unfolding along many fronts where the enactment of solidarity and resistance struggles are located. The parallel present is grounded in reality and involves fostering human relationships in the absence of authority. Following Colin Ward, this entails the actualisation and enhancement of already existing freedoms ‘rooted in the experience of everyday life, which operates side by side with, and in spite of, the dominant authoritarian trends of our society’ (1973: 11, emphasis added). Organising from an anarchist positioning, possibilities arise to enact what Richard Day, borrowing from Martin Buber, calls structural renewal: an ongoing strategy of anarchist dual power that expropriates social, cultural and material power from state-capitalist society (Day, 2005: 91). Structural renewal is guided by a logic of affinity. It operates as both a negative force that simultaneously works against state and corporate power, and as a positive force reversing their negative impacts through mutual aid (Day, 2005: 123-124). Day’s groundwork for this theory is keyed to Gustave Landauer, who famously wrote, ‘The state is a social relationship; a certain way of people relating to one another. It can be destroyed by creating new social relationships; i.e., by people relating to one another differently’ (1910/2010: 214). Thus, creating social change in the parallel present is not a structural task but a relational one to be realised, according to Paul Goodman, as ‘the extension of the spheres of free action until they make up most of social life’ (cited in Ward, 1973: 11; also cited in Day, 2005: 217). In this manner, resistance and prefigurative politics become guideposts for enhancing egalitarian relationships and institutions, not to ‘build’ a new society, but to outgrow the shell of the old society.

Video activism on the broadband: The sub.Media collective

In this article, I examine the prefigurative parallel present through the work of the video activist collective sub.Media (founded 1997). Their work contributes to developing communities of solidarity, providing the transformative potential necessary to a practice of prefigurative politics.

Sub.Media contributes intel, analysis, and inspiration to the movement by producing fast-hitting video interviews and subversive montages to inform and amuse its fanbase. It is one of many anarchist internet media collectives that have federated together under the Kollektiva social media platform, and it participates in the Channel Zero Network, an affiliation of anarchist and anti-authoritarian media providers. The goal of these federations is to create alternative/counter internet infrastructure to outmaneuver the logarithmic throttling and censorship policing of social media platforms such as Facebook and Instagram. Thus, sub.Media, through its affiliated network, fosters a broad spectrum of relations through ties with activist organisations, contributors, and audiences who provide support and sometimes shape the discourses that are brought to bear in this alternative/counter media ecosystem.

Sub.Media’s activities are a form of direct action; that is, acting ‘in the here-and-now’ to achieve one’s goals. As an independent crowd-funded collective, sub.Media operates on the model of a crafts-artel. Its economic structure supports one full-time and five part-time members who share responsibilities and visions for the project. Individuals realise their personal strengths while also rotating a roster of shared tasks, from copyediting and production to merchandising. In sum, sub.Media constitutes a counter-institution, challenging the establishment media while nurturing resistance struggles. Under the terms of structural renewal, sub.Media’s organisational activities proceed tactically as a simultaneous disengagement from and attack on the edifices of hegemonic media culture, spreading dissident media-activist content and maximising its distribution. Their videos merge deadly serious information with humour in its most parodic and sarcastic forms, utilising a fast, confrontational, and empowering aesthetic. They produce subversive, explicitly anarchist content by combining insightful analysis with original action footage. Often, they shoot interviews spliced with pop-culture media clippings, and lace them up with an impactful soundtrack. As one member, Heatscore, explained to me, ‘sub.Media didn’t coin the term “riot porn” but we sure popularized it for many people’ (Research Participant Interview, 11/11/2020).

Realising prefigurative politics and resistance unfolding in the parallel present involves autonomous individuals who share an affinity and together determine which tactics and strategies they will use to achieve their goals. In the case of sub.Media, video activism not only speaks for its producers as individuals: it gives voice to communities, and allows other resisters to see themselves in the images and stories in the video. Mobilising aesthetics, visual pleasure is ‘weaponised’ to reinforce the urgency of the messages. Additionally, when serving as media witness to confrontations and/or direct actions, video activism is situated on the cutting edge of oppositional movements of protest and resurgence. As such, video activism is a type of vanguard activity that stimulates further resistance. Let us review the crux of Trouble’s ‘Organize: For Autonomy and Mutual Aid’ trailer (see sub.Media, 2020).

What distinguishes anarchist organising, primarily, is the goals of that organising. If you want a future free from hierarchy and domination, if you want a future where people have autonomy and are treated equally, how you are engaging today has to reflect these values. (sub.Media, 2020: 0:33-0:55)

In this educational clip, sub.Media highlights the essential unity of means and ends embodied by intrinsic egalitarian values that inform anarchist organising strategies in anticipation of realising future goals. Sub.Media’s programming demonstrates that to prefigure this anticipatory future, anarchists engage in a variety of tactics, both destructive, as represented in the trailer, and creative, as evidenced by sub.Media’s production of the clip. As such, sub.Media inspires by exemplifying anarchist values desired in both present and future worlds: but most of all, the collective asserts resistance is not only possible, it is necessary.

Pushing the envelope with an aesthetic vanguard and the coming community

I am not the first to point out that artists are ideal social candidates for envisioning a coming ‘future’ society (hence the term ‘vanguard’). In art historical literature, artists, artist collectives, and art movements engaged with socially transformative practices are commonly designated ‘avant-garde’(meaning an ‘advanced’ vanguard) (Gibson, 1996). As I will demonstrate, the video activism of sub.Media is avant-garde because it is put to activist purposes towards an anarchist future vision. Vanguard art embeds its discourse not only by virtue of its subject matter and form (i.e., the visual, and visual-narrative), it also speaks to an audience relating to its medium and identifying with its content.

Sub.Media does not stand alone – there are a spectrum of vanguards within anarchism that are keyed to diverse tactical situations and possibilities to enact transformative politics in the present that, in turn, impact the future. To be clear, the multiple vanguards I speak of have nothing to do with hegemonically imposing an elite directorship on ‘the masses’, whether through a political party, or a school of academic thought (Graeber, 2009). I speak of vanguards in the plural, because in anarchist movements, various fronts of resistance are embedded in social movement networks wherein collectives, groups, or individuals perform different functions, but all are in alignment with shared goals and values. In general parlance, the idea of multiple vanguards is encapsulated by the concept of a ‘diversity of tactics.’ For example, some anarchists may defend Indigenous territories from colonial incursions by putting their bodies on the line, while others pressure politicians in public displays of opposition involving direct action or symbolic protest; still others may establish counter and alternative institutions to help build social, cultural, and economic capacity for the movement. Thus, diverse, self-organising ‘vanguards,’ operating on different ‘fronts,’ enact social change according to egalitarian values.

This is a tactical assessment of anarchistic vanguardism; but what ties these actors together? No one follows the ‘orders’ of an elite; rather, the vanguards as a whole organically self-organise, forming what Gustav Landauer describes as an imminent community in formation. Moreover, ‘community’ can also be prefigured: it is ‘yet to come:[pointing] to the one we want to initiate without further delay’ (1900/2010: 96). Thus, we have a prefigurative politics of affinity relationships. In the ‘coming’ community, Landauer does not consider individuals to be singular or isolated. Rather, they are points of manifestation, ‘the electrical sparks of something greater, something all encompassing’ (ibid.: 101). Asserting connection, not isolation, Landauer argues we find self-realisation through shared affinity. ‘Once individuals have transformed themselves into communities, then they are ready to form wider communities with like-minded individuals’ (ibid.: 105, emphasis added). Finding affinity by aligning in action towards shared goals, community in formation fosters solidarity that constitutes as a social movement.

Solidarity Politics and the Sparking of a Movement

Taking Landauer's position as the point of departure, enacting transformative politics on the level of individual awareness is an important tactic when pursuing prefigurative means and ends. One approach to creating a sense of community is the elicitation of solidarity. Generally speaking, solidarity is considered a phenomenon of ‘the masses,’ understood to be ‘successful’ when it involves a broad social spectrum. Demonstrating solidarity, both as individuals and groups, creates connections, and establishes trust. Solidarity politics can spark relationship-building, a process often filled with tension and negotiation, but one that is fruitful insofar as it can sustain mutual growth and support in the long-term. Solidarity is often the primary ‘give’ between groups and/or individuals creating shared relationships of struggle binding social movements, but what does it mean?

Anarchist theorist Richard Day defines solidarity as ‘a practice across all axis of oppression’ (2005: 5). Solidarity’s crux is a politics of affinity achieved through enacting ‘groundless solidarity’, a concept Day borrows from postmodern anti-racist feminist theory:

Groundless solidarity means seeing one’s own privilege and oppression in the context of other privileges and oppressions, as so interlinked that no particular form of inequality – be it class, race, gender, sexuality, or ability – can be postulated as the central axis of struggle. (ibid.: 18)

Arguing for a ‘politics of affinity’, Day focuses on the interstitial spaces between differences, where partially shared commonalities, hopes, and desires exist as empathetic forces. By nurturing empathy, Day argues ‘groundless solidarity’ is contiguous with ‘unity in diversity’, a commonality in which all movements unite to fight against oppression and injustice, and create alternative social structures to realize change. This is the context in which many anti-authoritarian vanguards seek to produce a politics that is open enough for individuals to connect with others in community, giving them opportunities to see where they may fit in the struggle, and together, create the future they would like to see in the present.

Mobilising solidarity and action: sub.Media supporting frontline resistance

By performing as a vital communications bridge between on-the-ground movement actors and the counter-publics that support them, sub.Media integrates with many vanguards operating on multiple fronts in resistance against colonialism, extractivist capitalism, and the state. Furthermore, the visual narratives they create foster a power of recognition that sparks reciprocal co-identification between the individual self and the ‘other.’ Through their essential communications function, sub.Media shares information that shapes resistance by educating and inspiring change, marshaling emotional affinity to spark on-the-ground support for social struggles.

One of sub.Media’s longstanding video campaigns has been to mobilise support for the Wet’suwet’en, an Indigenous nation currently under attack by neocolonial corporate actors and the Canadian state. The Wet’suwet’en are an Indigenous people whose territories are part of the province of British Columbia, Canada. They have been resisting the incursion of multiple pipelines in their territories for well over a decade. Presently, they are facing off against Coastal Gas Link (CGL), a company that intends to export ‘natural’ fracked gas by building a pipeline through Wet’suwet’en territories. The gas is to be processed on the Pacific coast and shipped to Asia. Aided and abetted by the unironically named Community-Industry Response Group (C-IRG), a militarised wing of the Royal Canadian Mounted Police (RCMP), CGL has been destroying the ecological integrity of traditional Wet’suwet’en lands, and disrupting/obliterating archeological sites. The company recently drilled a tunnel to snake the pipeline under a pristine salmon bearing river, the sacred Wedzin Kwa. Environmental destruction on the part of CGL in disrespect of the Wet’suwet’en’s sovereignty over their unceded territories is reinforced by daily C-IRG trespass, intimidation, and harassment of local Indigenous inhabitants. ‘Unceded’ means no treaties were ever signed with the state, and as such, Indigenous hereditary law, sovereignty, and self-determination have never been extinguished.[1] Moreover, the Wet’suwet’en are not only asserting sovereignty; their resistance is safeguarding the future for all people. Building the pipeline has consequences for all of us: in a time of catastrophic climate change, building fracked gas infrastructure prefigures the opposite of what the world needs; that is, if we want to share a clean, cool, and livable future.

Situational awareness backgrounder

Before I demonstrate how sub.Media’s video communications relay in solidarity with Wet’suwet’en Wing Chief Sleydo’ functioned, I need to present a situational awareness backgrounder.

In the fight for justice, equality, and self-determination in the parallel present, prefiguratively planting the seeds for a future without a state necessitates creating relationships. For over thirteen years (after fifteen years of prior preparations), the spark that has multiplied from Wet’suwet’en territory, riding a powerful wave of resurgence outward, has been the spark of decolonisation. April 1, 2009 marks the first checkpoint on the Wedzin Kwa in the territory of the Unist’ot’en clan (unistoten.camp, 2019). A group of Indigenous sovereigntists, starting with Dzeke Ze’[2] Freda Huson, Dini Ze’[3] Smogelgem, and Mel Bazil, built this checkpoint not as a ‘blockade’ but as a tool to enforce the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent Protocol, a traditional Indigenous practice that had lain dormant due to colonisation, but was reclaimed and reconstituted by sovereigntists practicing their hereditary laws and Indigenous knowledge (Bazil and CKUT Radio, 2014; Bazil and Média Recherche Action, 2012a). They founded the Unist’ot’en Action Camp just beyond their checkpoint and practiced the protocol to monitor their territory, and assert their sovereign, traditional responsibilities to the land (ibid.; see also Hill and Antliff, 2021: 108-111). Over the years the Unis’tot’en Action Camp invited thousands of supporters (many non-Indigenous anarchists) to visit and learn about their territories, traditions, and lifeways. Supporters, each of whom underwent a formal application and vetting process, were encouraged to join the sovereign Wet’suwet’en people not only in struggle, but to enter the path of decolonisation by helping to build the camp’s healing centre situated directly in the pathway of several proposed bitumen and frack gas pipelines (all proposals were stopped, and only the CGL pipeline project remains).

Fast forward to the three militarised incursions on the territories by the RCMP. The first took place on January 7, 2019. Ten people were arrested, and in response, an outpouring of solidarity actions took place across 70 cities. Then on January 1, 2020, Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Chiefs served CGL with an eviction notice to remove themselves and their equipment off Wet’suwet’en sovereign territories (unistoten.camp, 2020). Shortly afterwards, the second militarised incursion occurred on February 6, 2020. The state police forces disrespectfully and forcefully interrupted a sacred ceremony lead by Unist’ot’en Dzeke Ze’ Freda Huson in honour of the hundreds of Indigenous women, girls, and two-spirited people that have gone missing and are presumed murdered. In response to this outrage, supporters across Canada shut down major points of infrastructure, including ports, roads, and rail lines throughout February, 2020. In the capital of British Columbia, Victoria, hundreds (at night), if not thousands (during the day) of activists lead by Indigenous youth, camped out to ensure politicians could not easily access the Legislative Assembly. From their position at the ceremonial doors of the Legislature building, collaborating activists amassing around the sacred fire the Indigenous youth built, regularly, and tactically, dispersed onto the streets, taking bridges and major intersections disrupting traffic for hours at a time. Additionally, during these ‘festivities,’ activists #ShutDownCanada by simultaneously picketing all the B.C. government buildings in the capital, thus blocking the civil servants from gaining entry to their offices. To diffuse this crisis, the Canadian government offered to sign a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with Wet’suwet’en Hereditary Leadership. Wet’suwet’en allies stood down in good faith, believing the talks were to be meaningful, but they went nowhere.

The third militarised incursion on Wet’suwet’en territory was the most violent and forceful yet. On November 18-20, 2021, Wing Chief Sleydo’ and twenty-nine Wet’suwet’en plus invited allies were forcibly removed from their homes at gunpoint by police with trained attack dogs. Included in the group of arrestees were two legal observers and two accredited journalists. No news or information was allowed to come in or out as the state enforcers cut all lines of communication. Reporting on the aftermath, sub.Media interviewed two Haudenosaunee (Mohawk) allies, Lala Staats and Skylar Williams, who spoke of the dehumanizing treatment they endured en route to court after their arrest. This included being refused the right to wear their clothes in court (they had to appear in long underwear) and being transported in dog kennels built into police vehicles (sub.Media, 2021b). No other media outlet in Canada reported on this evidence of intensifying police state brutality.

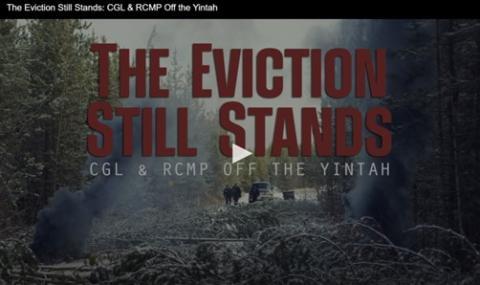

Video Amplification Mobilising Relationships

To mark this juncture in the resistance, sub.Media, in collaboration with the anarchist radio collective It’s Going Down, produced a remix/video montage to amplify the words of Gidimt’en checkpoint[4] spokesperson, Sleydo’.[5] Drawing from a November 12, 2021 interview, which she gave just before she was arrested, sub.Media remixed statements made before the raid with images of the event. The result is a video and audio montage articulating the determination of the Wet’suwet’en that inspires supporters to think up ways they can contribute to the resistance. It begins with Sleydo’s voice speaking from a distance, as if broadcast over a handheld radio. We are informed that the 2020 CGL eviction notice served by the hereditary Wet’suwet’en leadership will continue to be enforced. The timing is significant because the video was released after the November 18-20, 2021 raid. Stating the eviction will stand, the video amplifies the Wet’suwet’en’s subsequent actions, namely reoccupying Coyote Camp[6] the day after being raided. Next, while flashing a series of images of downing trees and excavators moving earth and snow to establish Indigenous road blockades, the remix draws out Sleydo acknowledging solidarity actions taking place throughout Canada. In this way, viewers are not only informed of these actions: they become witnesses to the frontline solidarity such struggle supports. Then a call to ‘come to the Yintah[7],’ or ‘take action wherever you are’ is showcased (ibid.: 0:48-1:00). A sequence of train tracks, highways, and blocked traffic appears as Sleydo’ discusses the potential threat of another #ShutDownCanada in response to continued state oppression. At the end of this sequence, while Sleydo’ refers to the militarised police threatening to remove Wet’suwet’en people at gunpoint, footage of an armed cop looking through a destroyed cabin door establishes the fact that the raid happened on November 18-20, 2021. This time frame juxtaposes the present viewing/witnessing of state violence, past threats of violence, and Sleydo’s promise to continue fighting into the future.[8] But the fight’s success needs supporters. Thus, the last sequence in the video hones in on Sleydo elaborating on relationships:

You know, we’ve seen this relationship between Indigenous warriors and anarchists that has been developing over the years, and I think that combining those two groups particularly is a really powerful move against the state. It’s a real threat; we’re a real threat when we act together, and so I just want to encourage people to act on that. Because we are on the right track. We are winning this fight and we just have to push harder and keep going and push the envelope even further than we already have. (ibid.: 1:33-2:10)

Sleydo’s original interview for It’s Going Down discusses working with multiple solidarity actions performed by ‘groups,’ and then explicitly identifies anarchists as collaborators. Sub.Media’s remix profiles the relationship between Indigenous warriors and anarchists, and then emphasises the imperative to act together. This narrative shift is not only aesthetic; it reflects a strong allyship that has been cultivated for years between Wet’suwet’en sovereigntists and non-Indigenous anarchists, who have been invited to collaborate in solidarity by the Wet’suwet’en.

I have discussed how sub.Media furthers prefigurative politics in a parallel present not only by educating and inspiring viewers to realise social transformation, but also by activating support and mobilising for action. In the fight for Indigenous sovereignty and resurgence, an important aspect of this transformative strategy (which sub.Media is aware of) are the decades of strategising, educating, and outreach that Indigenous movement leaders undertook to grow the relationship between anarchists and Indigenous warriors into what it is today.

Conclusion

In this article, I have discussed solidarity practices pertaining to the Indigenous-led resurgence movement of the Wet’suwet’en in Canada. And I have demonstrated the already existing parallel present path of decolonisation that is shared by Indigenous sovereigntists and anarchists. The fight against colonial injustices, from violence to ecocide, has many facets. Serving as a communications vanguard broadcasting the Wet’suwet’en’s sovereignty struggle to the rest of North America, sub.Media’s video activism encompasses both resistant and transformative practices in the moment. Their work unfolds in a parallel present where actions and media combine to carve out counter-narratives and create counter publics to realise egalitarian social transformation along multiple fronts, which, by harmonising means and ends, can serve to prefigure relations of community and solidarity. Through choreography, video, audio, music, and text, sub.Media amplifies the voices of Indigenous leadership, and collaborative allyship, creating connections of affinity between viewers and subjects. This work is particularly important in an age of video streaming and social media, because it contributes to relational transformation by expanding outward through extended spheres of interrelatedness. Sub.Media tells us what’s happening and keeps us inspired and informed. In their capacity as a communications and educational vanguard for the anarchist movement, sub.Media leads the way by ‘putting the word out there.’

References

Bazil, M. and CKUT Radio (2014) ‘Anarchy, indigenous sovereignty, and decolonization, part 2’. CKUT Radio, Montreal, QC. [https://ia802500.us.archive.org/6/items/afm-final-straw06152014/afm-final-straw06152014.mp3]

Bazil, M. and Média Recherche Action (2012a) ‘Transcending rights, a workshop by Mel Bazil (part 2)’. Vancouver Media Co-op, Victoria, BC. [http://www.radio4all.net/files/commune@riseup.net/4393-1-melbazilpresentation2.mp3]

Bazil, M. and Média Recherche Action (2012b) ‘Transcending Rights, a workshop by Mel Bazil (part 1)’. Vancouver Media Co-op, Victoria, BC. [http://www.radio4all.net/files/commune@riseup.net/4393-1-melbazilpresentation1.mp3]

Beaudoin, G. (2019) ‘Delgamuukw case’. [https://www.thecanadianencyclopedia.ca/en/article/delgamuukw-case]

Day, R.J.F. (2005) Gramsci is dead: Anarchist currents in the newest social movements. London, Ann Arbor and Toronto: Pluto Press.

Gibson, A. (1996) ‘Avant-garde’, in R.S. Nelson and R. Shiff (eds.) Critical terms for art history. Chicago & London: University of Chicago Press.

Goldman, E. (1924/1983) ‘Afterword to my disillusionment in Russia’, in A.K. Shulman (ed.) Red Emma speaks: An Emma Goldman reader. New York: Schocken Books.

Graeber, D. (2009) ‘Anarchism, academia, and the avant-garde’, in R. Amster, A. DeLeon, L. Fernandez, A.J. Nocella, and D. Shannon (eds.) Contemporary anarchist studies: An introductory anthology of anarchy in the academy. London; New York: Routledge.

Hill [Kwakwa̱ka̱ʼwakw], G. and A. Antliff (2021) ‘Indigeneity, sovereignty, anarchy: A dialog with many voices’, Anarchist developments in cultural studies, (1): 99–118.

Landauer, G. (1910/2010) ‘Weak statesmen, weaker people!’, in G. Kuhn (ed.) Revolution and other writings: a political reader. Oakland: PM Press.

Landauer, G. (1901/2010)‘Through separation to community’, in G. Kuhn (ed.) Revolution and other writings: a political reader. Oakland: PM Press.

sub.Media (2020) ‘Trouble #24: Organize: For autonomy and mutual aid [trailer]’. [https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0CksNzuLOEc]

sub.Media (2021a) ‘All out for Wedzin Kwa: Oct 9-15 week of action’. [https://sub.media/video/all-out-for-wedzin-kwa-oct-9-15-week-of-action/]

sub.Media (2021b) ‘Reconciliation at gunpoint: An interview with Layla Staats and Skyler Williams’. [https://sub.media/video/reconciliation-at-gunpoint-an-interview-with-layla-staats-and-skyler-williams/]

sub.Media and It’s Going Down (2021) ‘The eviction still stands: CGL & RCMP off the Yintah’. [https://sub.media/video/the-eviction-still-stands-cgl-rcmp-off-the-yintah/]

unistoten.camp (2019) ‘UNIST’OT’EN CAMP — Heal the people, heal the land: Timeline of the campaign’. [https://unistoten.camp/timeline/timeline-of-the-campaign/]

unistoten.camp (2020) ‘Wet’suwet’en hereditary chiefs evict Coastal GasLink from territory’. [https://unistoten.camp/wetsuweten-hereditary-chiefs-evict-coastal-gaslink-from-territory/]

Ward, C. (1973) Anarchy in action. Sydney, Melbourne, Auckland and London: Allen & Unwin.

The Author

Kimberly Croswell is a writer and settler activist-scholar living in Victoria, Canada, on unceded Lekwungen Territories. She recently completed her Ph.D. in Leadership, Adult Education, and Community Studies from the University of Victoria. Her dissertation, ‘Collective Leadership: Non-Hierarchical Organising in Activist Art Practices’ was supported by a Joseph-Armand Bombardier Graduate Doctoral Scholarship from the Social Sciences and Humanities Research Council of Canada. Kimberly has a history as a sculptor, and a puppetista. She organises collectively with Camas Books, an anarchist bookstore, infoshop, and community space. She is a member of the Victoria Anarchist Bookfair Collective and production manager for the open-source academic journal, Anarchist Developments in Cultural Studies.

Email: creatrix AT riseup.net

[1] In 1997 a British Columbia Supreme Court recognised Indigenous sovereign title in the historic case of Delgamuukw vs. British Columbia. In this precedential ruling, the court found the governments of Canada and BC had no right to extinguish ‘Indigenous peoples’ exclusive right to the land’ (Beaudoin, 2019, 10th paragraph, emphasis added). Thus, the Canadian federal and BC provincial governments are willfully ignoring Canadian case law in favour of enforcing the operations of Coastal Gas Link’s corporate interests.

[2] Meaning Female Chief; this was a title Freda Huson received later.

[3] Meaning Male Chief; this was a title, and traditional name Smogelgem received later.

[4] Gidimt’en checkpoint is the entry point onto the Wet’suwet’en territories. Conducting the Free, Prior, and Informed Consent Protocol at this checkpoint is the responsibility of the Gidimt’en (Bear) clan. Each militarised incursion on the part of the police has begun at this checkpoint.

[5] Go to https://sub.media/video/the-eviction-still-stands-cgl-rcmp-off-the-yintah/

[6] Coyote Camp is the name of the resistance campsite the Land Defenders occupied before their arrest and before CGL drilled under the river.

[7] Yintah is the Wet’suwet’en word for their homeland.

[8] On January 4, 2022, Sleydo’ announced the Gidimt’en would make a strategic retreat from Coyote Camp: ‘Our warriors are not here to be arrested. Our warriors are here to protect the land and the water, and will continue to do so at all costs’, stated Sleydo’ (Molly Wickham), a wing chief of the Cas Yikh people. ‘Every time that the RCMP, the C-IRG, has come in to enforce CGL’s injunction they have done violence against our women. They have imprisoned our Indigenous women and our warriors. We will not allow our people to be political prisoners’ (January 6, 2022, Unist’ot’en Solidarity Brigade email).