Kori Rumore

5 things you might not know about Chicago native Ted Kaczynski — the ‘Unabomber’ who died in prison Saturday

Ted Kaczynski over a car near Lincoln, Mont., in the early 1970s, after Ted had settled outside the small town, immersing himself in a self-imposed survivalist retreat. He shunned electricity, poached wild game and grew his own vegetables.

But Ted's Montana retreat only seemed to fuel his rage and isolation. He railed against overhead jets interrupting his sleep, his perfect quiet. He began trashing nearby cabins, booby-trapping trails with neck wires meant to decapitate anyone speeding by on a noisy motorcycle or snowmobile. He also started building bombs--primitive devices, with triggers fashioned from match heads. (Kaczynski family photo)

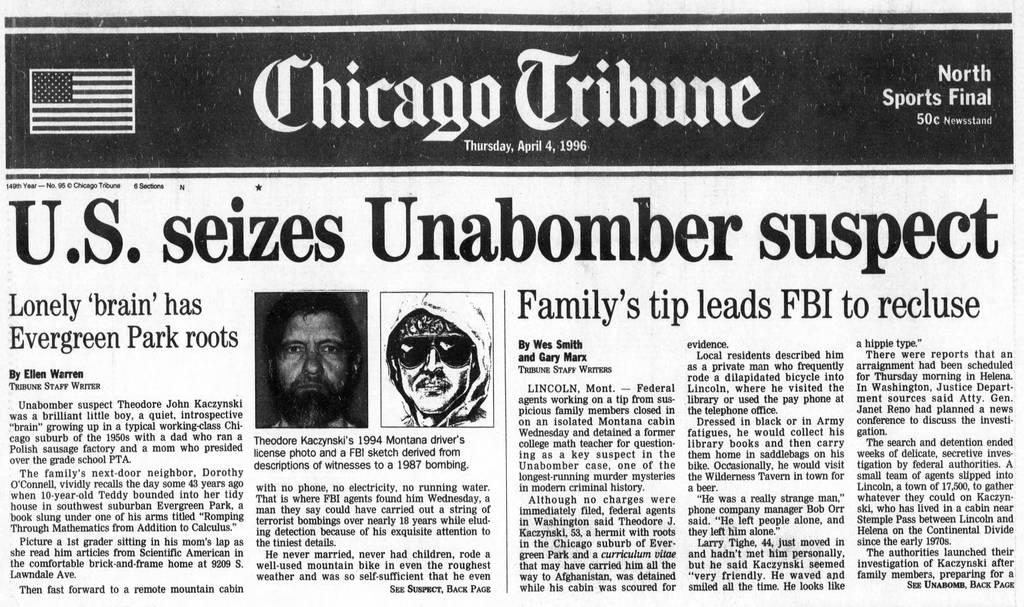

Theodore “Ted” Kaczynski, who died Saturday, was born and raised in the Chicago area. It’s also where he began an 18-year career terrorizing academics and industrialists by planting his handmade explosive devices disguised as everyday objects.

It’s been 27 years since the reclusive former math professor was arrested and 25 years since he was sentenced to life in prison.

Here’s a look back at some obscure milestones in a life that began in suburban Evergreen Park, then dissolved into anger, paranoia, hate and destruction.

1. Family members say isolation began at an early age for Kaczynski.

Close relatives of Kaczynski told investigators that he had a lengthy and traumatic separation from his parents at the age of 6 months, when he was hospitalized with a severe allergic reaction.

2. He was a loner who rarely interacted with classmates — except for once during a chemistry class — then entered Harvard at an age when most teens get their driver’s license.

By all accounts, Wanda Kaczynski doted on her mathematical genius son, pushing him academically while apparently not helping him to adjust socially, neighbors told the Tribune in 1996. From the time Teddy was a baby, she kept a diary about him, reading to him day and night while his father, also named Theodore, earned a living making sausage at his factory at 49th Street and Ashland Avenue.

Neighbors recalled that his doting mother, Wanda, was so intent that her boys, Teddy and younger son David, get a head start that she opened a neighborhood preschool in the days before hardly anyone thought about sending toddlers to classes. She also read him articles from Scientific American when he was a first grader.

When Kaczynski was in fifth grade, he scored a 167 on an IQ test, well into genius territory. A school counselor told Kaczynski’s mother that her son could be “another Einstein.” In junior high school, he was correcting his algebra teacher. As he progressed academically, though, Ted withdrew further into books, and into himself. His intelligence only exacerbated his lack of social skills, the Tribune reported.

Kaczynski was considerably younger than most of his classmates at Evergreen Park Community High School in the late 1950s due to skipping a few grades. He was in band, Biology Club, Coin Club, German Club and Math Club.

Painfully shy, Kaczynski found the most popular students in Mr. McCaleb’s chemistry class suddenly paying attention to him in 1958. What they wanted, some of his old classmates recollect, was in his head: a recipe for a small explosion. He readily wrote it down, the classmates recall. But the measurements were somehow bollixed, causing an explosion that blew out windows and led to what might be Kaczynski’s second-most-serious encounter with authority: He was suspended.

He would graduate in three years then head to Harvard University on scholarship at age 16. Just scarcely past his 20th birthday in 1962, Kaczynski had already collected his math degree from Harvard. At the University of Michigan, he earned a master’s degree in mathematics in 1964 and his Ph.D. in the same subject there three years later. He joined the faculty of the University of California at Berkeley as an assistant professor of mathematics. But Kaczynski lasted there less than two years. Although he made his home in Montana, he is known to have returned to the Chicago area at least twice in the 1970s.

3. The Unabomber’s first victims — ‘a scientist, businessman or the like’ — were in the Chicago area.

In 1978, Kaczynski returned from Montana to the family home, now in Lombard, and went to work at a foam rubber company in Addison, where his younger brother, David, was a supervisor. It was about that time that Kaczynski assembled his first bomb.

His writings show him to be a patient and methodical killer. Kaczynski noted in his journal that his chief reason for returning to Chicago was to “more safely attempt to murder a scientist, businessman or the like. … In the anonymity of the big city, I figured it would be much safer to buy materials for a bomb and mail it.” In his writings, Kaczynski detailed how he selected the name of his first victim at random from the ranks of professors engaged in technical fields.

The first four bombings connected to Kaczynski were nonfatal:

May 25, 1978: The first bomb was left in a parking lot at the University of Illinois at Chicago (then known as the Circle Campus) because he could not fit it into a mailbox, and he hoped that a student in a scientific field would find it and “blow his hands off or get killed,” Kaczynski wrote. A passerby picked it up and returned it to the person Kaczynski listed on the return address as the sender. That person, a Northwestern University professor, was suspicious about the package and turned it over to security there. A public safety officer at Northwestern suffered minor injuries when he opened the package and it exploded.

May 9, 1979: Northwestern University graduate researcher John G. Harris was treated for cuts on his arms and burns on his eyes after a bomb in a cigar box exploded when he opened it in a study room at the school’s Technological Institute. Police said the force of the blast blew his eyeglasses off his face and singed his eyebrows and lashes.

Nov. 15, 1979: A bomb inside a mail pouch explodes in the cargo hold of an American Airlines 727 jet traveling from Chicago to Washington, D.C., forcing an emergency landing at Dulles International Airport. Twelve people suffer smoke inhalation.

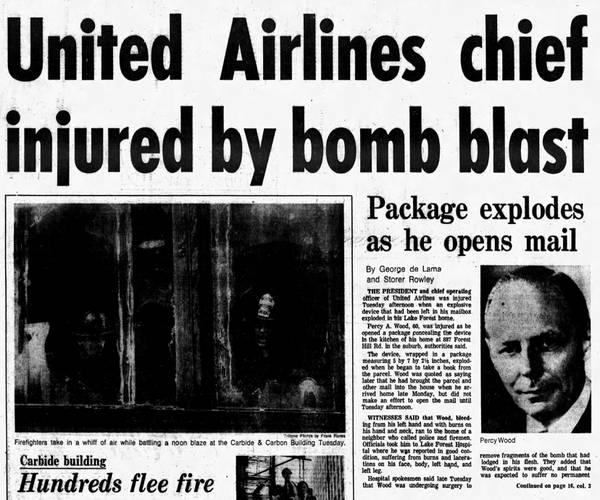

June 10, 1980: Percy A. Wood, United Airlines president and chief operating officer, was injured after opening a book inside a package that had been left inside his mailbox at his Lake Forest home. He suffered from burns and lacerations on his face, body, left hand and left leg. In a coded entry in his journal dated Sept. 15, 1980, Kaczynski wrote, “After complicated preparation I succeeded IN INJURING THE PRES. OF UNITED A.L. BUT HE WAS ONLY ONE OF A VAST ARMY OF PEEPLE WHO directly and indirectly are responsible for the JETS.”

There were 15 more explosions, which killed three people and injured 23 in 18 years. The last bomb exploded in April 1995, killing a lumber industry lobbyist in California.

Kaczynski pleaded guilty in January 1998 — almost 20 years to the day after the Unabomber’s first pipe bomb exploded — to three bombing murders and the maiming of two other people and agreed to a life sentence in prison without the possibility of release. He avoided the death penalty and a trial where he would have been portrayed as mentally ill.

4. David Kaczynski led the FBI to his older brother. He received a reward — $1 million — but didn’t keep it.

Without the information from David Kaczynski, authorities might still be pursuing the case they initially dubbed UNABOMB, because the early cases involved universities, the “UN,” and airlines, the “A.”

Then a social worker in New York, David initially tried to prove his older brother was not the Unabomber. Both Kaczynski boys inherited their father’s suspicions about the technological world. At various times in their lives, both men lived “off the grid,” without electricity, without shaving.

David’s suspicions about his brother began during the summer of 1995. From their home in upstate New York, he and his wife, Linda Patrik, heard media reports of locations of the Unabomber’s crimes: suburban Chicago, Salt Lake City, Berkeley, California.

David realized that his brother — a mathematical genius who had dropped out of mainstream society — had ties to them all. He was left with “a nagging feeling,” his attorney Anthony Bisceglie told the Tribune in 1996.

When the Unabomber’s 35,000-word manifesto was published by The New York Times and The Washington Post in September 1995, David pored through it “with the idea that he would be able to immediately discount any connection between his brother and the Unabomber,” Bisceglie said.

Instead, the manifesto, with its strong anti-technology message, left David Kaczynski with “considerable unease,” Bisceglie said. It reminded David of correspondence the family had received from Theodore.

One stunning example: Both Ted and the Unabomber reversed the old saying “have their cake and eat it too” by writing “eat their cake and have it too.”

In the first week of February 1996, Bisceglie told investigators the name Theodore J. Kaczynski. Neither David nor his attorney were aware that the federal government offered a $1 million reward for the information that broke the Unabomber case, if it led to a conviction.

When the reward was paid out, David set up a fund to give away the $1 million reward. Most of it went to the Unabomber’s victims or their families.

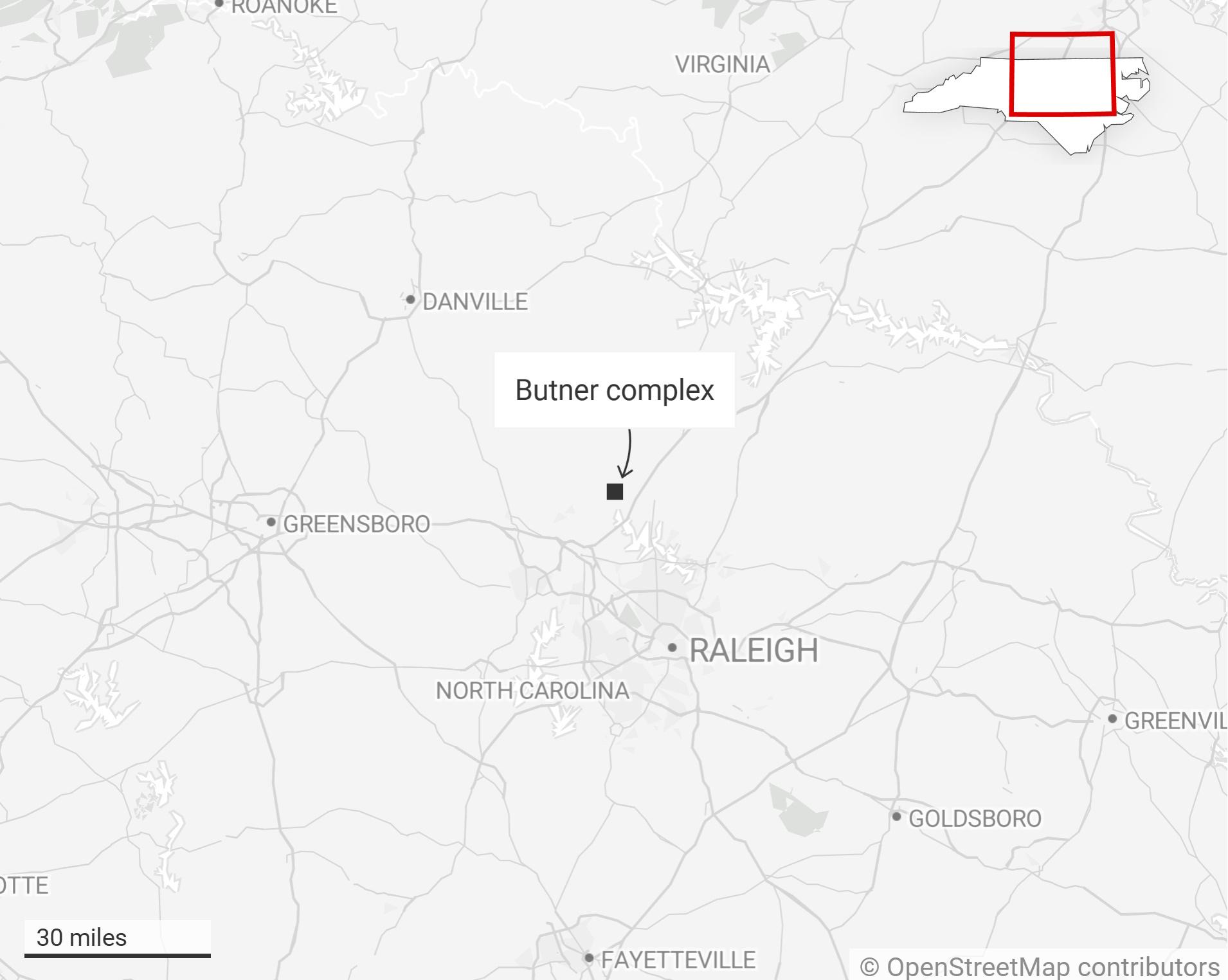

5. The federal prison complex where Kaczynski was an inmate has also housed other notable Chicagoans.

Singer R. Kelly, former Chicago police commander Jon Burge, former Rep. Mel Reynolds and ex-Rep. Jesse Jackson Jr. all served time at Butner Federal Correction Institution in North Carolina. Mob hit man “Frankie Breeze” Calabrese died at its Federal Medical Center in 2012.

High-profile inmates at the facility have included Bernard Madoff, the New York City financier whose Ponzi scheme led investors to lose their fortunes, who died at the complex in 2021, and “Tiger King” star Joe Exotic.

Sources: Tribune reporting and archives; AP

Subscribe to the free Vintage Chicago Tribune newsletter, join our Chicagoland history Facebook group and follow us on Instagram for more from Chicago’s past.

Twitter @rumormill