Lauren Joseph, Matthew Mahler & Javier Auyero

New Perspectives in Political Ethnography

Introduction: Politics under the Ethnographic Microscope

Official Rhetoric in Everyday Life

Chapter 2. Losing Face in Philippine Labor Confrontations: How Shame May Inhibit Worker Activism

Dynamics of Shame in Face-to-Face Encounters

Shame and the Habitus of Personal Dependents: The Case of Philippine Plantation Workers

From Deference to Confrontation

Emotion Work: Changing Sentiments and Behavioral Dispositions

The Historical Context of Protest Demonstrations in Japan

Anti-Emperor Protest as a Site for Constructing the Limits of Dissent

Demonstrations as a Social Form

The Isolation of Demonstrations and Protesters

Protecting the Public from Contamination by Outcasts

Spatial and Conceptual Dislocation of Protest

Narrowing the Limits of Permissible Protest

Policing by Surveillance and Bodily Control

Compliance with the Limits on Dissent

Implications for the Study of Protest Policing

Chapter 4. Honor and Morality in Contemporary Rural India

Ideological Integration in the 1970s and 1980s

Informal Indications of the Decline of Former Village Lords

Ideological Bases for Village Rule Today

Chapter 5. Routing Conflict: Organized Violence and Clientelism in Rio de Janeiro

Drug Trafficking and Clientelism in Rio de Janeiro

History and Operation of Clientelism in the Americas

A Short History of Clientelism in Rio de Janeiro

The Practice of Clientelism in Three Rio de Janeiro Favelas

Clientelist Practices in Rio Today

Chapter 6. Vicious Virtuous Circles: Barriers to Institution-Building after War

Prior Literature: Connections Among Social Capital, Trust and Confidence

“Good Governance” in Postwar Bosnia

OSCE Workshops and Dual Outcomes for the Development of Confidence

Analysis of Citizen Engagement of Local Authorities

On States and Social Movements: Conflictual Cooperation

Making Gains and Relationships

Project H.O.M.E.: “Confidence and ‘Inaction’ ”

Favorable Sites for the Institutionalized Advocates

Institutionalized Authority and its Reproduction

Chapter 9. Field Research During War: Ethical Dilemmas

The Research: High-Risk Collective Action and Democratization as a Way out of Civil War

Field Conditions in Comparative Perspective

Emotional Challenges in Field Research

Chapter 10. Politics as a Vocation: Notes Toward a Sensualist Understanding of Political Engagement

The Political Passions of Lyndon Johnson and Joe Trippi

Chinese-Box Epistemology and Beyond

Towards an Analytic of Political Experience

Chapter 11. Afterword: Political Ethnography as Art and Science

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

New Perspectives in Political Ethnography

Edited by

Lauren Joseph

Department of Sociology

Stony Brook University

Matthew Mahler

Department of Sociology

Stony Brook University

Javier Auyero

Department of Sociology

Stony Brook University

Springer

[Contact]

Lauren Joseph

Sociology Dept.

SUNY-Stony Book

Stony Brook 11794–4356

Email: lajoseph@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

Other Email: Qualitative_Sociology@notes.

cc.sunysb.edu

Javier Auyero

Sociology Dept.

SUNY-Stony Brook

Stony Brook 11794–4356

Email: jauyero@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

Matthew Mahler

Sociology Dept.

SUNY-Stony Brook

Stony Brook 11794–4356

Email: mmahler@notes.cc.sunysb.edu

[Copyright]

ISBN-13: 978-0-387-72593-2 e-ISBN-13: 978-0-387-72594-9

Library of Congress Control Number: 2007931383

© 2007 Springer Science+Business Media, LLC

All rights reserved. This work may not be translated or copied in whole or in part without the written permission of the publisher (Springer Science+Business Media, LLC, 233 Spring Street, New York, NY 10013, USA), except for brief excerpts in connection with reviews or scholarly analysis. Use in connection with any form of information storage and retrieval, electronic adaptation, computer software, or by similar or dissimilar methodology now know or hereafter developed is forbidden.

The use in this publication of trade names, trademarks, service marks and similar terms, even if they are not identified as such, is not to be taken as an expression of opinion as to whether or not they are subject to proprietary rights.

Printed on acid-free paper.

9 8 7 6 5 4 3 2 1 springer.com

Contents

Introduction: Politics under the Ethnographic Microscope

Javier Auyero and Lauren Joseph

1. From Confusion to Common Sense: Using Political Ethnography to Understand Social Mobilization in the Brazilian Northeast

Wendy Wolford

2. Losing Face in Philippine Labor Confrontations: How Shame May Inhibit Worker Activism

Rosanne Rutten

3. Radical Outcasts Versus Three Kinds of Police: Constructing Limits in Japanese Anti-Emperor Protests

Patricia G. Steinhoff

4. Honor and Morality in Contemporary Rural India

Pamela Price

5. Routing Conflict: Organized Violence and Clientelism in Rio de Janeiro

Enrique Desmond Arias

6. Vicious Virtuous Circles: Barriers to Institution-Building after War

Tammy Smith

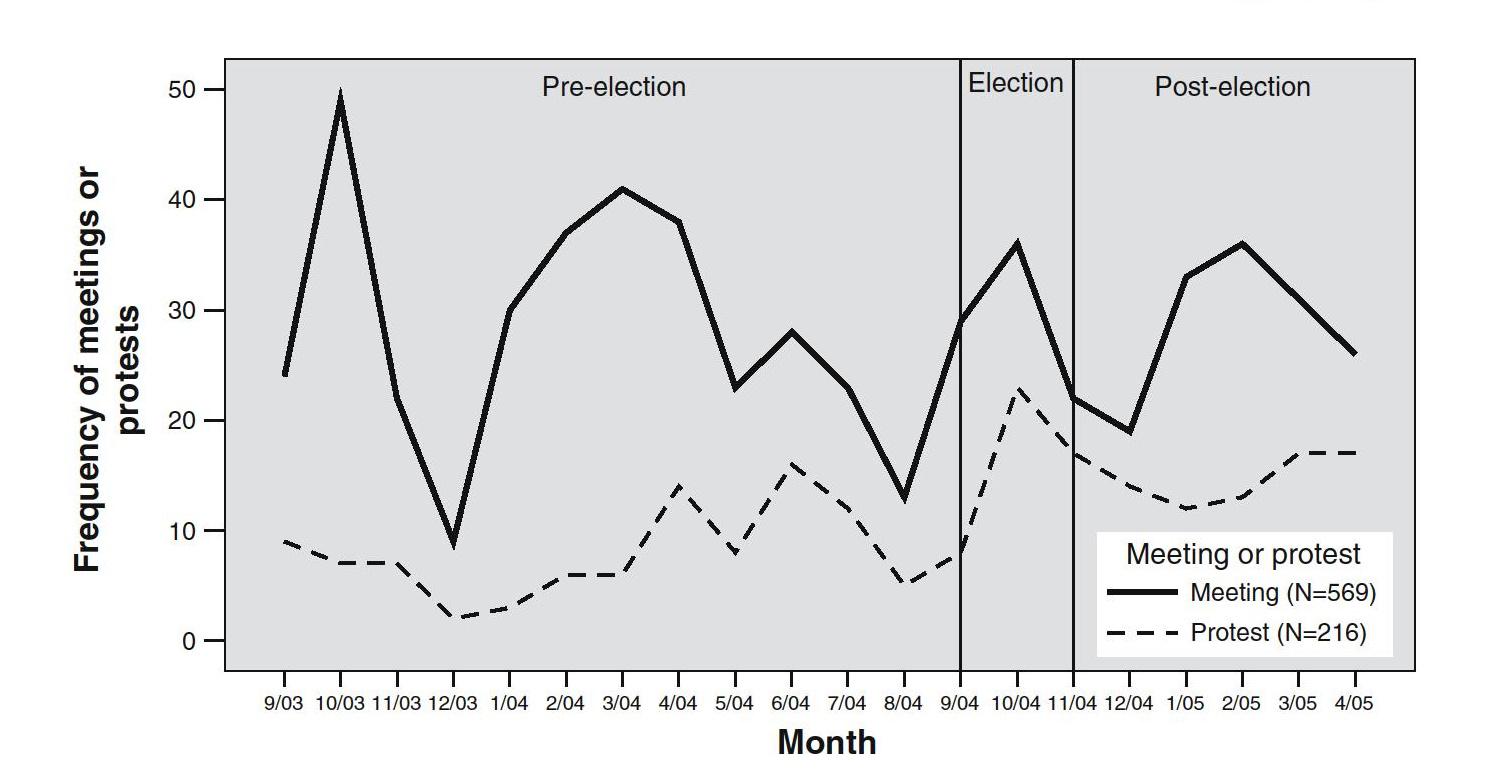

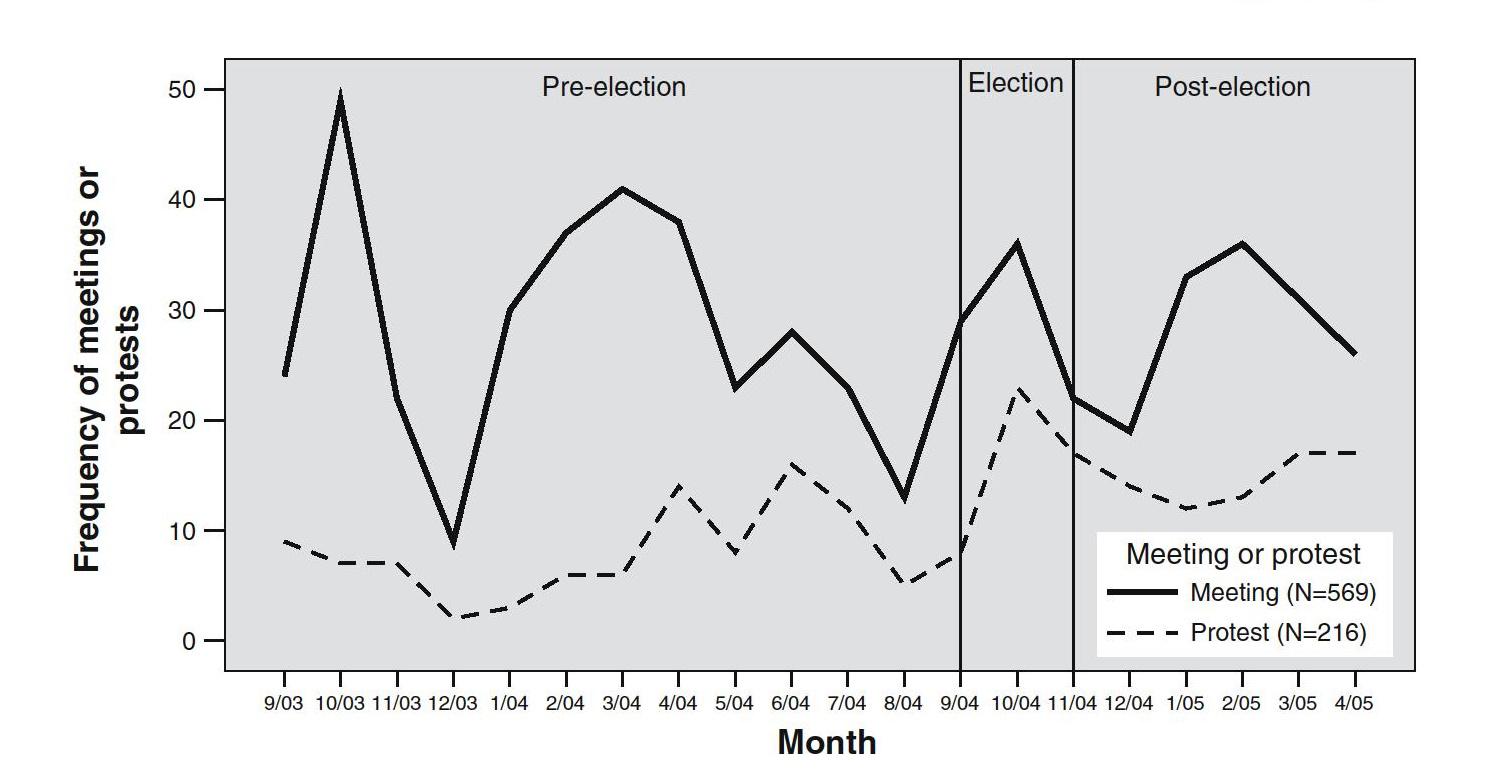

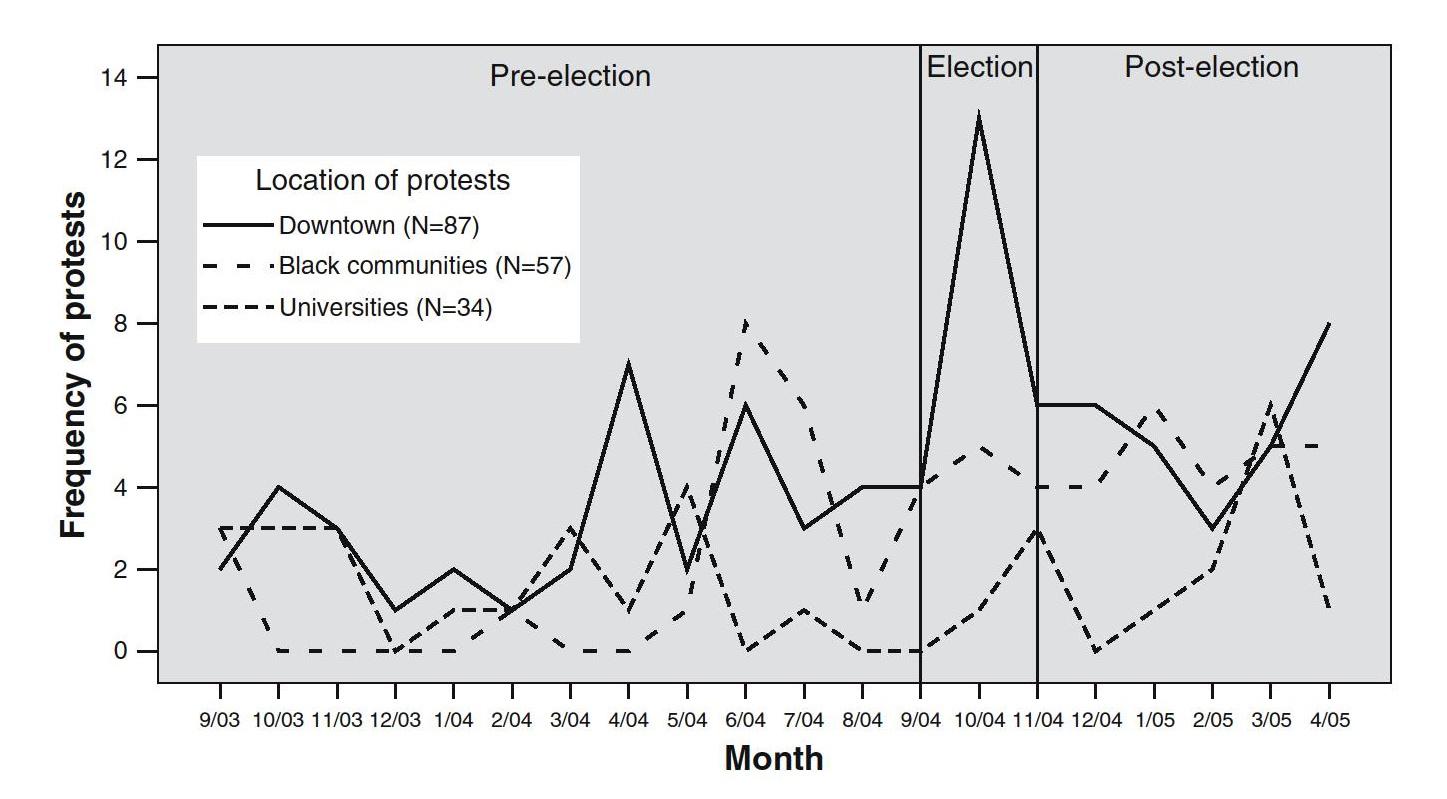

7. Are National Politics Local? Social Movement Responses to the 2004 US Presidential Election

Kathleen M. Blee and Ashley Currier

8. Professional Performances on a Well-Constructed Stage: The Case of an Institutionalized Advocacy Organization

Mirella Landriscina

9. Field Research During War: Ethical Dilemmas

Elisabeth Jean Wood

10. Politics as a Vocation: Notes Toward a Sensualist Understanding of Political Engagement

Matthew Mahler

11. Afterword: Political Ethnography as Art and Science

Charles Tilly

About the Contributors

Index

Contributors

Enrique Desmond Arias, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, City University of New York, New York

Javier Auyero, Department of Sociology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York

Kathleen M. Blee, Department of Sociology, University of Pittsburgh, Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania

Ashley Currier, Department of Sociology and Women’s Studies, Texas A&M University, College Station, Texas

Lauren Joseph, Department of Sociology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York

Mirella Landriscina, Department of Social Sciences, St. Joseph’s College, Brooklyn, New York

Matthew Mahler, Department of Sociology, Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, New York

Pamela Price, Department of South Asian History, University of Oslo, Oslo, Norway

Rosanne Rutten, Department of Sociology and Anthropology, University of Amsterdam, Amsterdam, The Netherlands

Tammy Smith, Department of Sociology, State University of New York at Stony Brook, Stony Brook, New York

Patricia G. Steinhoff, Department of Sociology, University of Hawaii, Honolulu, Hawaii

Charles Tilly, Department of Social Sciences, Columbia University, New York, New York

Wendy Wolford, Department of Geography, University of North Carolina-Chapel Hill, Chapel Hill, North Carolina

Elisabeth Jean Wood, Department of Political Science, Yale University, New Haven, Connecticut

Introduction: Politics under the Ethnographic Microscope

Javier Auyero and Lauren Joseph

Go and sit in the lounges of the luxury hotels and on the doorsteps of the flophouses; sit on the Gold Coast settees and on the slum shakedown; sit in the Orchestra Hall and the Star and Garter Burlesque. In short, gentlemen, go get the seat of your pants dirty in real research.

Robert Park

The revival of ethnographic research within sociology is undisputed. New journals, new books from major presses, and new hires at top research departments all attest to the renewal, growth, and increasing relevance of the ethnographic craft among sociologists. As ethnography is (re)gaining a well-deserved prominence within the discipline its empirical focus, theoretical underpinnings, and narrative styles are also expanding — traditional forms of ethnographic inquiry now coexist with more experimental ones.

From dealing drugs (Bourgois 1995), to emigrating and immigrating (Fitzgerald 2006; Smith 2006), prostituting (Murphy and Venkatesh 2006), working off the books (Venkatesh 2006), boxing (Wacquant 2003a), dancing (Wainwright et al. 2005), glassblowing (O’Connor 2006), designing objects (Molotch 2005), providing services in luxury hotels (Sherman 2007), and street vending (Duneier 2000) — the list of activities and subjects upon which ethnography has focused its attention in recent years is virtually inexhaustible. Ethnographers have been heeding Park’s advice: they have gotten the seat of their pants dirty in a myriad of places, researching all sorts of (more or less exotic) practices.

Yet, at a time when few, if any, objects are beyond the reach and scrutiny of ethnographers, it is quite surprising that politics and its main protagonists (state officials, politicians, and activists) remain largely un(der)studied by ethnography’s mainstream. It is indeed fair to say that both routine (party, union, NGO) and contentious (social movement and other forms of collective action) politics are far from the top of contemporary ethnography’s agenda. One figure should suffice to illustrate politics’ marginal status among sociological ethnography: out of 215 articles published in the last 10 years in sociology’s main journal devoted to ethnography, the Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, only 15 focus on politics as their main subject (see Hunter 1993; Ostrander 1993 for some of the few prior exceptions). It is time to move politics out of the shadows and into the center of ethnographic attention.

True, during the last decades a number of notable books have ethnographically explored the workings of both ordinary and extraordinary forms of political action. James Scott (1987), Robert Gay (1994), Faye Ginsburg (1989), Paul Lichterman (1996), Nina Eliasoph (1998), Richard Wood (2002), Ben Kerkvliet (2005), Adam Ashforth (2005), and Gianpaolo Baiocchi (2005) are some of the authors who come, or should come, immediately to mind; but these writings are too few and too far between to constitute a coherent corpus of ethnographic work — similar to the body of, say, ethnographies of poverty enclaves (Bourgois 1995; Sharff 1998; Newman 2000; Venkatesh 2002; Dohan 2003; Young 2003) or factory life (expanding from Roy ([1954] 2006) through Burawoy (1982) to Salzinger (2003)).

Let us take a very basic, agreed-upon, definition of ethnography as:

social research based on the close-up, on-the-ground observation of people and institutions in real time and space, in which the investigator embeds herself near (or within) the phenomenon so as to detect how and why agents on the scene act, think and feel the way they do (Wacquant 2003b, p. 5).

One would expect that this mode of inquiry would be one of the preferred tools among those for whom the study of politics is their profession — that is, political scientists and political sociologists. After all, ethnography is uniquely equipped to look microscopically at the foundations of political institutions and their attendant sets of practices, just as it is ideally suited to explain why political actors behave the way the do and to identify the causes, processes, and outcomes that are part and parcel of political life. But here, as with many other scholarly matters, common sense serves as a less than reliable guide. A closer examination reveals that ethnography is far from the favorite mode of analysis among political scientists and political sociologists, for whom surveys, secondary data (usually culled from newspapers), formal modeling, and statistical approaches constitute the standard methodological tools. To witness: peruse the issues of the American Journal of Political Science and the American Political Science Review for the last 10 years (1996–2005). Out of a total number of 569 and 369 articles, respectively, only one article relies on ethnography as a data-production technique (Soss 1999). Unfortunately, however, in concentrating, almost exclusively, on the models, charts, regressions, and correlations of standard political research, social science has missed a significant aspect of the ongoing reality that is politics: namely it has missed the nitty-gritty details of politics, its “day-to-day intricacies” (Baiocchi 2005, p. 16), its “implicit meanings” (Lichterman 1998), its passions, and its sacrifices (Mahler, this volume); in other words, the pace of political action, the texture of political life, and the plight of political actors have all been cast into the shadows created by the unnecessary and deleterious overreliance on quantitative methods in both political science and political sociology.

This volume aims to address this double absence: of politics in ethnographic literature and of ethnography in studies of politics. Focusing on case studies from around the world, the chapters in this book draw upon close-up observation of politics in action to scrutinize the dispositions, skills, desires, and emotions of a variety of political actors and the meanings that they attach to their practices.

Large-scale political transformations have ground-level sources and effects. The ethnographic microscope serves to capture these quite well. We do not believe that ethnography is the only way of studying politics. But the chapters included here reinforced our conviction that ethnography provides the “thickest” form of political information (Geertz 1973; Ortner 2006).

The chapters included in this volume are significantly revised and expanded versions of chapters first published in a double special issue of the journal Qualitative Sociology. In their attention to the microscopic aspects of politics, the chapters in this volume demonstrate that ethnography is particularly well-equipped to capture “the practice of politics (strategic choices), the signification of these practices (culture/meaning-making)” as they unfold (Blee and Currier, this volume), and the confusions, emotions, and uncertainties that, although inherent in all forms of political action, conventional political analysis tends to dismiss (or ignore) as either “noise” or anecdotal information with no relevance for what “really” matters (Wolford, this volume). Ethnography is also particularly useful to capture changing and/or persistent beliefs and their relationship to specific practices (Price, Rutten, Smith, all this volume) and the nitty-gritty details and effects of different forms of political action, networks, and tactics (Arias, Landriscina, Steinhoff, all this volume).

There are three other areas to which political ethnography can make a really useful contribution. Since they are not covered in the chapters included in this book, we would like to briefly summarize what we see as research topics for future ethnographic research on politics. Let us call them: repertoires-in-the-making, clandestine-connections-count, and official-rhetoric-confronts-daily-experience.

Repertoires-in-the-Making

Understood as the set of routines by which people get together to act on their shared interests, the notion of repertoire of collective action (first coined by Tilly 1977, and then deployed by a series of scholars, Traugott 1995) invites us to examine patterns of collective claim-making, regularities in the ways in which people band together to make their demands heard, across time and space. The notion brings together different levels of analysis ranging from large-scale changes such as the development of capitalism (with the subsequent proletarianization of work) and the process of state-making (with the parallel growth of the state’s bulk, complexity, and penetration of its coercive and extractive power) to patterns of citizen-state interaction. This term exhorts us to conceptually hold together macrostructures and microprocesses by looking closely at the ways in which big changes indirectly shape collective action by affecting the interests, opportunities, organizations, and identities of ordinary people. Furthermore, the notion makes clear the need for a simultaneous analysis of diachrony and synchrony with its emphasis on both the forms of protest and at their transformation.

The term repertoire is eminently political and cultural. Political, in that this set of contentious routines (1) emerges from continuous struggles against the state, (2) has an intimate relationship with everyday life and routine politics, and (3) is constrained by patterns of state repression. Cultural, in that it focuses on people’s habits of contention, on the form that collective action takes as a result of shared expectations and learned improvisations. The repertoire, then, is not merely a set of means for making claims but also an array of meanings that arise relationally, in struggle; meanings that, as Geertz puts it, are, “hammered out in the flow of events” (Geertz 2001, p. 76). Learning through struggle is thus at the core of the theatrical metaphor of repertoire: “Repertoires are learned cultural creations, but they do not descend from abstract philosophy or take shape as a result of political propaganda; they emerge from struggle” (Tilly 1995, p. 26). What do protesters learn? Tilly explains, “People learn to break windows in protest, attack pilloried prisoners, tear down dishonored houses, stage public marches, petition, hold formal meetings, organize special-interest associations. At any particular point in history, however, they learn only a rather small number of alternative ways to act together” (Tilly 1995, p. 26). How does this learning process affect subsequent ways of acting?: “The existing repertoire constrains collective action; far from the image we sometimes hold of mindless crowds, people tend to act within known limits, to innovate at the margins of existing forms, and to miss many opportunities available to them in principle. That constraint results in part from the advantages of familiarity, partly from the investment of second and third parties in the established forms of collective action” (Tilly 1986, pp. 390–391).

Political ethnography offers both a perspective and a toolbox to focus simultaneous attention on two issues that, located at the heart of the notion of repertoire, have too often been divorced, namely the impact of structural change on collective action and the transformation of the culture of popular protest. The ethnographic microscope can detect and dissect in situ, in real time and space, how the meanings of contention are formed and contested in interaction, and how this learning actually takes place (and in what ways, through which channels and mechanisms, the learning limits successive performances and how the innovation emerges).

Clandestine Connections Count

Clandestine connections between legal political actors are crucial in routine politics and in extraordinary collective violence and they have recently attracted some, still scattered, scholarly attention. Research on the origins and forms of communal violence in Southeast Asia, for example, highlights the usually hidden links between partisan politics and violence (Das 1990). Shaheed’s (1990) analysis of the Pathan-Mujahir conflicts during 1985–1986 shows that the riots can be “traced directly to the actions of religious political parties.” Paul Brass’ notion of “institutionalized riot systems” captures well these usually obscure connections: in these riot systems, Brass points out, “known actors specialize in the conversion of incidents between members of different communities into ethnic riots. The activities of these specialists [who operate under the loose control of party leaders] are usually required for a riot to spread from the initial incident of provocation” (1996, p. 12). Sudhir Kakar’s (1996) description of a pehlwan (wrestler/enforcer who works for a political boss) further illustrates this point: the genesis of many episodes of collective violence is located in the area where the actions of political entrepreneurs and those of specialists in violence (people who control the means of inflicting damage on persons and objects) secretly meet and mesh (see also Varshney 2002; Wilkinson 2004). Linda Kirschke’s (2000) work on transitions to multiparty politics in Sub-Saharan Africa offers additional examples of the (usually masked) constant interweaving between party and state in the making of violence. In the Americas, we have several other illustrations of the effects that the activation of clandestine connections among political actors may have on routine and nonroutine forms of political action (Gunst 1995; Roldan 2002; Goldstein 2003, Arias 2006). Our own work on the dynamics of food lootings (Auyero 2006, 2007; Auyero and Moran 2007) unearths the concealed interactions between looters, political activists, and police forces that shaped the incidence and form of collective violence.

Political analysis tends to focus attention on “respectable” politics, on the “civilized” forms of political interaction, the sort that takes place in parliaments and government houses and that enjoys media attention. In many parts of the world, this kind of politics depends on clandestine, hidden connections (what one of us terms “the gray zone of politics” (Auyero 2007)). Students of politics should take the ambiguous and obscure zone seriously, making it the empirical focus of sustained research efforts. If, as Debora Yashar argues (1999, p. 97), rigorous scholarly attention needs to be paid to the ways in which “democracy is practiced,” the gray zone should not be excluded from neither serious theoretical nor empirical consideration. Visible state-society relations are undoubtedly important to the quality of democracy in many parts of the world, so are hidden and clandestine links between different political actors. There is indeed much work to be done on this crucial dimension and ethnography is particularly well-suited to inspect this hidden backstage of politics.

Official Rhetoric in Everyday Life

Conventional political analysis should move beyond the study of official rhetoric by looking at the ways in which it resonates (and, in the process, is transformed) in the everyday life of ordinary folks (Wedeen 1999). One last example on this area should suffice to make our case for political ethnography. In their splendid study of everyday ethnicity in the Transvylvanian town of Cluj, intensive fieldwork allows Brubaker and his collaborators to dissect “the everyday contexts in which ethnic and national categories take on meaning and the processes through which ethnicity actually ‘works’ in everyday life” (Brubaker et al. 2006, p. 9). Their study wonderfully shows that ethnography is not only an excellent methodological tool; it is also a “stance” — as Sherry Ortner (2006) puts it — to study the relationships between the discourse and practices of political leaders and “beliefs, desires, hopes, and interests” (p. 167) of the ordinary folk. In particular, Brubaker and his collaborators focus on the resonances of the “rhetoric of ethnopolitical entrepreneurs,” convincingly illustrating the “disjuncture between intense and intractable nationalist politics and the ways in which ethnicity and nationness are embodied and expressed in everyday life” (p. 16)

From Tillyian “big structures and large processes” (such as the history of nationalist and nationalizing politics in East Central Europe) to small but highly significant practices (such as ways of answering the phone (p. 223)), the book shows the virtues and potentials of a rigorous and systematic attention “in fine-grained detail to the contexts and contours, the timing and trajectories, the meanings and modalities of ethnicity and ethnicization in everyday life” (p. 16). Moving away from “viewing nationalist politics from a distance, and from above,” which according to the authors “fosters a kind of optical illusion” (p. 167), they take an in-depth look at the disjuncture between “the thematization of ethnicity and nationhood in the political realm and their experience and enactment in everyday life” (p. 363). The result is an epistemological rupture of sorts which offers a corrective to “overethnicized interpretations of culture, society, and politics” (p. 363).

To study how ethnicity works, Brubaker argues, we need to study everyday experience. And for this, the author strongly implies, ethnography is fundamental. The same could be argued about all sorts of more or less contentious, more or less collective, and more or less routine politics. Ethnography, the authors of this volume will show, is useful for understanding how political hegemony is constructed, challenged, and reconstructed, how political habits are constructed, how activists make (or fail to make) choices, how “culture” enables and constrains individual and collective actions, how party or social movement politics connect (or disconnect) from everyday life, and so on.

All too often, theory testing in sociology is performed on what might be termed “stylized facts,” oversimplified descriptions generated by concepts and notions which usually fail to capture the fine-grained, microsociological, processes at work. As a result, much macrosociological work in political sociology rests on conceptually weak microfoundations and on an understanding of politics that removes from sight much of what politics is really about (power, yes, but also desires, sacrifices, emotions, etc.). The kind of political ethnography that these articles carry out (and the kind that we advocate) is an essential tool for providing a more solid foundation for sociological (both theoretical and empirical) work. Sociology, we strongly believe, needs more political ethnography.

Political ethnography, in the skilled hands of the contributors to this volume, is both theoretically sophisticated and empirically rigorous. Regarding theory: the political ethnography undertaken here is designed to critically evaluate the strengths and limitations of central sociological concepts such as power, legitimacy, clientelism, habitus, mobilizing structures, political opportunities, social capital, and so on. Regarding empirical work: this volume exemplifies the virtues, challenges, and complexities of traditional fieldwork, an approach which still requires, to use Sidney Mintz’s (2000) apt phrase, “the same willingness to be uncomfortable, to drink bad booze, to be bored by one’s drinking companions, and to be bitten by mosquitoes as always.” We hope the articles demonstrate why sociology needs more of this “old-fashioned” field research.

The specific sociopolitical universes on which these authors focus their empirical attention are quite varied thematically and geographically: social movement politics in rural Brazil and the USA, community politics in India and urban Brazil, insurgent activism in Japan, the Philippines and El Salvador, party politics in Washington D.C., and local municipal politics in Philadelphia and Bosnia. Similarly diverse are the actors on which contributors focus their attention (professional politicos, militants, organizers, municipal officials, NGO activists). In order to dissect these worlds and to understand these actors, the authors employ various theoretical orientations (from Katz’s phenomenology to Bourdieu’s genetic structuralism and Tilly’s relational realism) and narrative choices (one voice, multiple voices; one style, multiple ones). Through these multiple problématiques, objects, orientations, and writing styles, the reader is introduced to the blossoming innovations in this slowly emerging field of inquiry.

There are numerous ways of ordering (thus providing a blueprint for readers) the chapters in this volume (by geographical area covered, by actors on which authors focus attention, by the preferred techniques used to produce evidence, by the authors’ theoretical inclinations, etc.). We think that the classificatory grid provided by Charles Tilly at the end of this book, centered on the kind of general analytic questions asked by each contributor, offers a helpful guide both for the reader and the ethnographic practitioner: (1) How does a specific cause generates its effects? (Wolford, Rutten, Steinfhoff, Price, Arias); (2) How can we explain the diverse processes that take place in apparently comparable situations? (Smith, Blee and Currier, and Landriscina); and (3) How can we ethnographers create knowledge that is both reliable and convincing about specific social processes? (Wood and Mahler).

Wendy Wolford’s research in the sugarcane region of northeast Brazil, conducted over a 4-year period, documents the trajectory of the rural workers’ movement in a plantation settlement. Despite early success of the movement in which land was distributed among workers and commitment levels to the movement were high, Wolford’s research finds that several years later the movement was in crisis in the region. In this work, she focuses on interviews with one rural worker turned land reform settler, a former member of the movement whose reasons for joining and leaving the movement speak to what she calls the “fuzziness” of movement membership more generally. She points out that within any given movement there are varying degrees of engagement, and highlights the merit of interviewing along the continuum of movement commitment levels. More importantly, she uses this data to illustrate the fluidity and contradictions of social movement membership and identity. Rather than explaining away what she calls the “confusion” that emerges in subjects’ accounts of their behavior, rather than imputing an intentionality to their actions which creates a rational post-facto justification, she creates a self-conscious analysis of contradiction and silence that can more accurately account for the realities of social change and movement trajectories.

Rosanne Rutten’s research on plantation laborers in the Philippines traces the history of activism in that setting over the last several decades. Living in a sugarcane plantation community for extended periods of time between 1978 and 2000, she was witness to a gradual change in habitus for the workers from that of clientelist mode to activist mode. The feudalistic system of patronage and paternalistic mode of interaction on the plantations had created a context in which workers were indebted to planters through relationships based on personal dependency and loyalty. Rutten argues that shame, as an emotion and a behavioral disposition, functioned as an obstacle to face-to-face confrontations and claim-making by workers in this context of clientelism. Claimants, she found, were both vulnerable to personal humiliation when their claims were rejected, and felt embarrassment for breaching the established rules of worker-planter interaction. She documents the efforts of local labor movement groups to mobilize these workers over several decades, pointing out what she calls the “emotion work” undertaken by these labor groups which empowered workers to challenge the authority of planters. Over time, many of the workers developed a “radical habitus,” and were consistently engaged in various types of activism against plantation owners. By taking a long-view perspective of this case study, one that spans many years in the field, Rutten’s research has added yet another dimension to the role that emotions and behavioral dispositions play in both the reproduction of static social relations and in patterns of involvement in social movements.

In her study of anti-emperor protests in Japan during 1990–1991, Patricia Steinhoff examines the street demonstration as a social form through observation and limited participation. She finds that the limits of dissent within a society are established not only by the conditions set by law and formal regulations pertaining to demonstrations, but are more actively negotiated by police and protesters through direct interaction within the protest setting. By focusing her attention directly on the demonstration setting and observing patterns of direct contact she documents tactics used by police to control and minimize the effects of protests on the public consciousness. By stigmatizing and separating demonstration participants from mainstream Japanese public life, and by dividing more radical movement groups from other member groups within the broader coalition anti-emperor movement, the police and government forces succeed in using soft repression to limit the expression of dissent against the state. These tactics involve the use of several types of police to manage the rallies, including armed riot police whose presence exaggerated the threat of the anti-emperor movement to casual onlookers, raised the tension of these protests, and effectively manipulated the message that the protesters sought to portray to the public. Using fine-tuned attention to interactional patterns during these protests, Steinhoff’s study suggests that the boundaries of social dissent are constructed and reconstructed over time through direct contact between the state and political actors on the streets.

Pamela Price examines the changing meanings of honor, authority, and respect in rural India in the context of political and social shifts in local power structures. Under new conditions of democratization in which political power is increasingly dislocated from high caste status, the diversification of political officers has had an impact on the definitions of the qualities of respect and authority drawn upon by villagers. In previous eras, notions of respect were associated exclusively with those of high caste status who concurrently held political dominance in the village, and were based on hierarchical relations connected to fear and dependence. Since the decline of the village lords as political leaders and the rise of lower caste villagers to positions of political authority, Price finds that villagers increasingly define honor and respect in terms of moral and individual characteristics. During her research of 6 months of fieldwork in a rural Indian village, she closely analyzes the various words and idioms used by locals to describe concepts of authority and respect. Drawing on this meticulous and focused examination of language, Price concludes that shifting relations of power and authority have created new definitions of honor and respect that illustrate the emergent political and social conditions of the local setting.

Desmond Arias’s article examines the transformation of clientelist practices in Rio de Janeiro and the impact of the growing power of drug traffickers in favelas. He finds the emergence of what he calls a “two-tiered” system of clientelism, in which drug traffickers act as patrons to favela residents by distributing goods and services obtained through contacts with politicians. This mode of “neo-clientelism” signals a transfer of local power from the local neighborhood association leaders to the traffickers, contrasted with previous eras in which local leaders procured benefits for the community in exchange for allegiance to local politicians. While traditional practices of clientelism provided an effective means for the impoverished residents of favelas to link themselves into political organizations and to redress basic grievances, Arias argues that this new form of clientelism reduces residents’ already precarious identification with politicians and further removes them from the political process. Drawing on 2 years of fieldwork in three favelas in Rio de Janeiro, he concludes that criminal violence has been incorporated into the political process in a way that was unseen in prior configurations of clientelist practices.

In postwar Bosnia, Tammy Smith documents the low level of citizen confidence in institutions, and considers the impact of this condition for the rebuilding of institutions under the new democratic state. As residents recovered from a war in which state institutions were used to promote widespread violence and ethnic cleansing, Smith found that citizens are reluctant to endow governing organizations with the confidence that they will be effective in governance and nondiscriminatory in their policies. She bases her assessment on research conducted over 3 years within a local governance development program in Bosnia, which served as a training program for representatives from local governments and nongovernmental organizations as well as local citizens. She concluded that while citizens possessed interpersonal trust in individuals who worked in local institutions, this trust did not translate into increased confidence in institutions. Moreover, her data suggest that reliance upon interpersonal trust in fact undermines the development of institutional confidence, in turn undermining the strength of institutions. Institutions must begin to function again if the state is to transition from war to liberal democracy, she argues, and they will need citizens’ confidence and participation to do it.

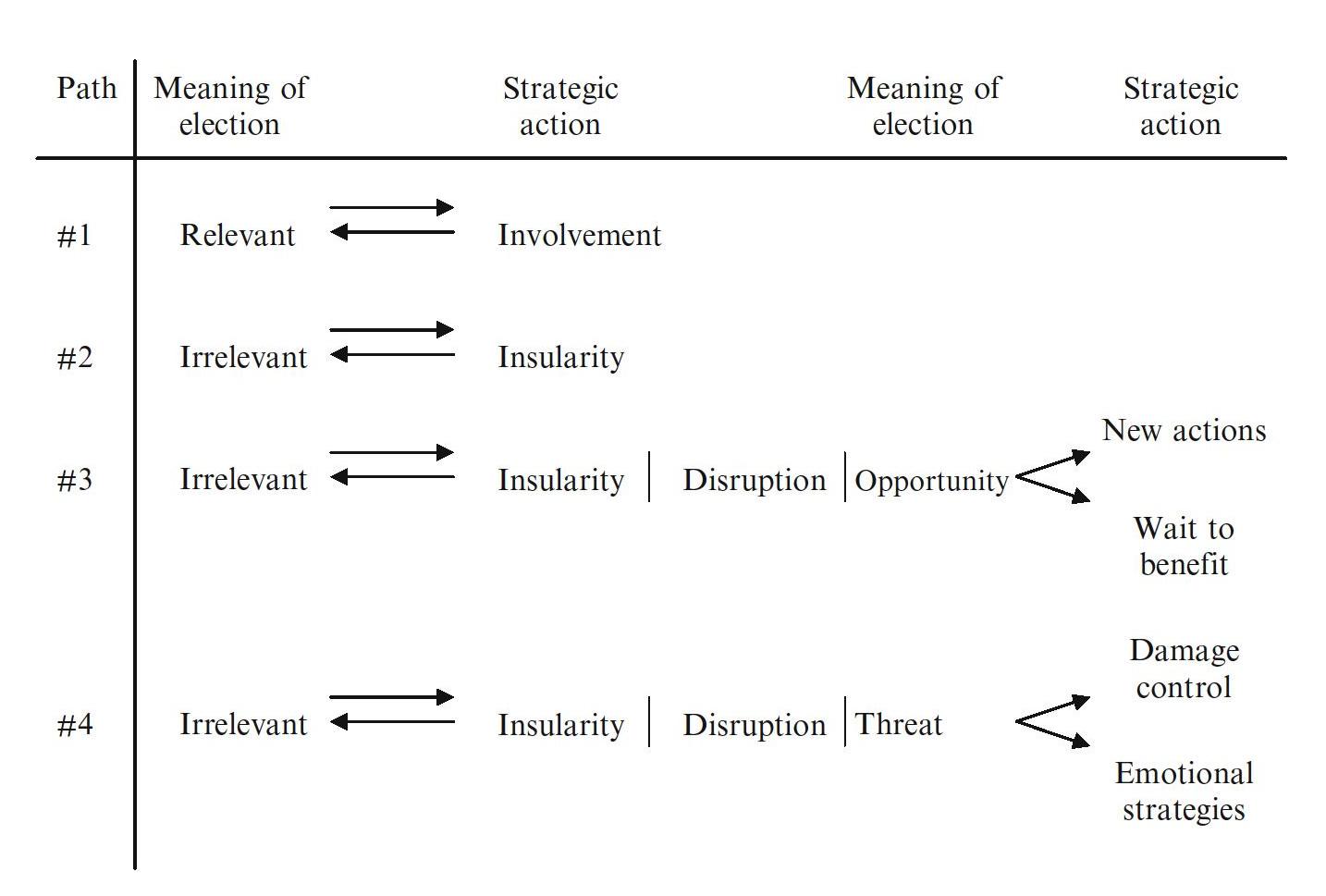

How do social movement groups (SMGs) respond to national elections? Blee and Currier tackle this question by tracing the strategic choices of these groups and the tactics they developed over time. The authors analyzed continuous data on 15 SMGs over a 20-month period that extended across the electoral cycle. Ethnographic research using groups as the unit of analysis provided a context to view both moments of action as well as inaction or avoidance in relation to the election. Moreover, through fieldwork the authors were privy to the unfolding process of collective meaning-making or culture in progress as sequences of action were created. The authors argue that patterns of action by SMGs were path-dependent, with self-reinforcing sequences of action disrupted at turning points in their trajectories. It is during these turning points, they find, that the dynamics of meaning-making, or group culture, can be detected and analyzed for their significance and impact on paths of action. Further, by analyzing the timing of action in relation to the contextual field of the election and other groups’ activity, the authors also integrate the concept of timing as a factor to consider in research on SMGs. How SMGs react to a national election may vary, they contend, but it is in the different patterns of response — and the decisions made that produced such a response — that we can learn about the internal dynamics of SMGs.

Is institutionalization bad for social movement organizations? Can an advocacy group undergo professionalization yet continue to act as an independent entity and pursue radical or disruptive goals? Mirella Landriscina’s work engages these usually elusive questions in her examination of Philadelphia’s homeless politics while conducting research within a homeless service provider and advocacy organization called Project H.O.M.E. Her study focuses on how Project H.O.M.E. responded in 2002 to a push by downtown business groups for legislation that would curb what they saw as an unruly street population. This organization was well-established in the community and had extensive resources and networks, both to city officials such as police and to the business community. It was this connectivity that provided the setting for what Landriscina refers to as “conflictual cooperation” and communication among the actors, allowing for negotiation and arbitration regarding the problem of homelessness in the downtown area. Thus, she argues, the privileged position of an institutionalized organization can set the stage for playing a key role in managing conflict, but does not necessarily restrain the organization from acting in its own interests. Landriscina concludes that even from this centralized position in the dispute over homelessness in the city, Project H.O.M.E. remained an independent actor capable of posing challenges to authorities when the protection of homeless rights was at stake. Her research sheds light on the potential capacity of organizations to effect radical change when they have been incorporated into the mainstream of local politics.

Elisabeth Wood presents a methodological piece addressing the ethical dilemmas that arise during field research in conflict zones. She draws on 26 months of research in El Salvador during the civil war with actors across various political divisions, from armed insurgents to military and government personnel, NGO staff, and ordinary citizens. She outlines the multiple ethical and emotional challenges that she faced and highlights the spaces in which traditional research protocols were insufficient for providing concrete guidance as to how to resolve these dilemmas. Ethical challenges Wood encountered in the field included issues of informed consent, the protection of politically sensitive data, the dissemination of findings, and the repatriation of data, and were compounded by emotional challenges that included the stress and loneliness of working for long periods of time in field sites of violence and insecurity. Wood’s analysis points to the conclusion that ultimately the researcher must rely upon her own judgment in interpreting the generalized norms of ethical field research while navigating the exigencies of her field site. This chapter presents the practical, on-the-ground challenges of field research, the unanticipated and complex dynamics of one’s field site and the demands placed upon the researcher, particularly in politically charged settings, and supplies insight into how fieldworkers work through these intricacies during research.

Matthew Mahler, finally, pushes the boundaries of ethnographic research methods by drawing on works of political nonfiction, producing an analysis of “politics-in-action” with a view into the construction of the political self. By focusing on political practice and action, he taps into the sensual and physical experience of the political actor as animal — a living, breathing, suffering being whose engagement with politics is far more complex than traditional explanations of political practice can account for. To answer the question of why one engages in politics, he directs our attention away from categorical analyses such as rational choice theory that fail to consider the foreground of action in which the political actor is sensually and aesthetically drawn into political practice. Up-close observations and detailed depictions, he argues, can be found in the richly descriptive and vivid data of political autobiographies, biographies, and journalistic articles. It is in these accounts that this distinctive form of passion, in which the agent is engaged with the embedded and aesthetic attractions of his environment, can be reconstructed and brought to light for an embodied analysis of political practice.

Acknowledgments We would like to thank the authors who contributed to this volume (who graciously accepted suggestions for reviews and did so in a timely manner), Charles Tilly who wrote a very illuminating afterword, Teresa Krauss at Springer who was very enthusiastic about this project from the very beginning (and supported it throughout), two anonymous reviewers who made helpful suggestions to the book prospectus and this introduction, the numerous reviewers who provided sound advice to the contributors, and our colleagues and friends at the Sociology Department at Stony Brook University who provided the needed institutional and emotional support. Thanks to all!

References

Arias, D. 2006. Drugs and democracy in Rio de Janeiro. North Carolina: The University of North Carolina Press.

Auyero, J. (2006). The political makings of the 2001 lootings in Argentina. Journal of Latin American Studies, 38, 1–25.

Auyero, J. (2007). Routine politics and collective violence in Argentina: The gray zone of state power. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Auyero, J., & Moran, T. (2007). The dynamics of collective violence: Dissecting food riots in contemporary Argentina. Social Forces (March).

Ashforth, A. (2005). Witchcraft, violence, and democracy in South Africa. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Baiocchi, G. (2005). Militants and citizens: The politics of participatory democracy in Porto Alegre. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press.

Bourgois, P. (1995). In search of respect. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Brass, P. (1996). Riots and pogroms. New York: New York University Press.

Brubaker, R., Feischmidt, M., Fox, J., & Grancea, L. (2006). Nationalist politics and everyday ethnicity in a Transvylvanian town. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Burawoy, M. (1982). Manufacturing consent. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Das, V. (1990). Mirrors of violence: Communities, riots, and survivors in South Asia. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Dohan, D. (2003). The price of poverty: Money, work, and culture in the Mexican-American barrio. California: University of California Press.

Duneier, M. (2000). Sidewalk. New York: Farrar, Straus and Giroux.

Eliasoph, N. (1998). Avoiding politics: How Americans produce apathy in everyday life. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Fitzgerald, D. (2006). Towards a theoretical ethnography of migration. Qualitative Sociology, 29, 1–24.

Gay, R. (1994). Popular organization and democracy in Rio de Janeiro: A tale of two favelas. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Geertz, C. (2001). Available light: Anthropological reflections on philosophical topics. New Jersey: Princeton University Press.

Ginsburg, F. (1989). Contested lives: The abortion debate in an American community. Berkeley, CA: University of California Press.

Goldstein, D. (2003). Laughter out of place: Race, class, and sexuality in a Rio shantytown. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Gunst, L. (1995). Born fi’ dead: A journey through the Yardie posse underworld. New York: Canongate Books.

Hunter, A. (1993). Local knowledge and local power: Notes on the ethnography of local community elites. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 22, 36–58.

Kakar, S. (1996). The colors of violence: Cultural identities, religion, and conflict. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Kerkvliet, B. J. T. (2005). The power of everyday politics: How Vietnamese peasants transformed national policy. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Kirschke, L. (2000). Informal repression, zero-sum politics and late third wave transitions. Journal of Modern African Studies, 38, 383–403.

Lichterman, P. (1996). The search for political community: American activists reinventing commitment. New York: Cambridge University Press.

Lichterman, P. (1998). What do movements mean? The value of participant observation. Qualitative Sociology, 21, 401–418.

Mintz, S. (2000). Sows’ ears and silver linings: A backward look at ethnography. Current Anthropology, 41, 169–189.

Molotch, H. (2005). Where stuff comes from; How toasters, toilets, cars, computers and many other things come to be as they are. Routledge.

Murphy, A., & Venkatesh, S. (2006). Vice careers: The changing contours of sex work in New York City. Qualitative Sociology, 29, 129–154.

Newman, K. (2000). No shame in my game: The working poor in the inner city. New York: Vintage.

O’Connor, E. (2006). Glassblowing tools: Extending the body towards practical knowledge and informing a social world. Qualitative Sociology, 29, 177–193.

Ortner, S. (2006). Anthropology and social theory. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Ostrander, S. (1993). ‘Surely you’re not in this just to be helpful’: Access, rapport, and interviews in three studies of elites. Journal of Contemporary Ethnography, 22, 7–27.

Roldan, M. (2002). Blood and fire: La violencia in Antioquia, Colombia, 1946–1953. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Roy, W. ([1954] 2006). Cooperation and conflict in the factory: Some observations and questions regarding conceptualization of intergroup relations within bureaucratic social structures. Qualitative Sociology, 29, 59–85.

Salzinger, L. (2003). Genders in production: Making workers in Mexico’s global factories. California: University of California Press.

Scott, J. (1987). Weapons of the weak: Everyday forms of peasant resistance. Yale, NH: Yale University Press.

Shaheed, F. (1990). The Pathan-Muhajir conflicts, 1985–6: A national perspective. In V. Das (Ed.), Mirrors of violence: Communities, riots and survivors in South Asia (pp. 194–214). Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Sharff, J. (1998). King Kong on 4th street. Boulder, CO: Westview.

Sherman, R. (2007). Class acts: Service and inequality in luxury hotels. Berkeley: California University Press.

Smith, R. C. (2006). Mexican New York: Transnational lives of new immigrants. Berkeley: California University Press.

Soss, J. (1999). Lessons of welfare: Policy design, political learning, and political action. American Political Science Review, 93, 363–380.

Tilly, C. (1977). Getting it together in Burgundy, 1675–1975. Theory and Society, 479–504.

Tilly, C. (1986). The contentious French. Cambridge: Harvard University Press.

Tilly, C. (1995). Contentious repertoires in Great Britain. In M. Traugott (Ed.), Repertoires and cycles of collective action. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Traugott, M. (Ed.) (1995). Repertoires and cycles of collective action. Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Varshney, A. (2002). Ethnic conflict and civic life: Hindus and Muslims in India. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.

Venkatesh, S. (2002). American project: The rise and fall of a modern ghetto. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Venkatesh, S. (2006). Off the books: The underground economy of the urban poor. Harvard, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wacquant, L. (2003a). Body & soul: Notebooks of an apprentice boxer. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Wacquant, L. (2003b). Ethnografeast: A progress report on the practice and promise of ethnography. Ethnography, 4, 5–14.

Wainwright, S., Williams, C., & Turner, B. S. (2005). Fractured identities: Injury and the balletic body. Health, 9, 49–66.

Wedeen, L. (1999). Ambiguities of domination: Politics, rhetoric, and symbols in contemporary Syria. Chicago: The University of Chicago Press.

Wilkinson, S. (2004). Votes and violence: Electoral competition and ethnic riots in India. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Wood, R. (2002). Faith in action. Chicago: Chicago University Press.

Yashar, D. (1999). Democracy, indigenous movements, and the postliberal challenge in Latin America. World Politics 51(1): 76–104.

Young, A. (2003). The minds of marginalized black men: Making sense of mobility, opportunity, and future life chances. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press.

Chapter 1. From Confusion to Common Sense: Using Political Ethnography to Understand Social Mobilization in the Brazilian Northeast

Wendy Wolford

The decade of the 1990s was a difficult one for the sugarcane region of northeastern Brazil. Local producers were hurt by falling international prices for sugar: from a high of almost one dollar per pound in the early 1980s, the price fell to an average of 10–12 cents a pound throughout the 1990s (World Bank Report No. 20754-BR 2002, p. 34). Price decreases were exacerbated by changes in the nature of state support: in 1989, the newly democratic Brazilian government began dismantling and progressively withdrawing its generous safety net for northeastern sugarcane producers (de Andrade and de Andrade 2001). Subsidies that had previously (since 1975) allowed northeastern producers to compete with their more efficient counterparts in the South were cut by more than 60% in 1989 (Buarque 1997). By 1995, 15 of 26 sugarcane distilleries in Pernambuco — the state responsible for a majority of the total sugarcane produced in the Northeast at that time — were either shut down or on the verge of bankruptcy (Lins 1996, p. 2). Production in the state had fallen from 20 million tons in 1989 to 14 million in 2000–2001 (de Andrade and de Andrade 2001, p. 147), and plantation and distillery owners were leaving their land for healthier industries elsewhere (particularly tourism on the coast). Common laborers were badly hurt by the crisis: in an industry heavily dependent on manual labor, an estimated 350,000 workers were unemployed in 1996 and considered unlikely to find work even during the harvest season.

Crises such as this one are not uncommon in sugarcane. As with most monocropped agricultural commodities, sectoral crises are a regular response to shifts in international supply and demand. In one important way, however, this crisis was different from the past: economic conditions combined with the increasing presence of the largest grassroots social movements in Brazilian history, O Movimento dos Trabalhadores Rurais Sem Terra (The Movement of Rural Landless Workers, commonly known as the MST). As the crisis deepened, the MST began effectively mobilizing former rural workers to occupy idle plantations and pressure the government to distribute the land. The MST’s methods centered on purposeful civil disobedience, particularly the occupation and symbolic appropriation of spaces such as large farms or plantations, government buildings, and public thoroughfares. The movement’s ideology reflected its leadership’s roots in the peasant culture of southern Brazil, and also brought together an eclectic mix of leftist radicals such as Karl Marx, Antonio Gramsci, Paulo Freire, Mao Tse-Tung, and Mahatma Ghandi. Formed in southern Brazil in 1984 to fight for agrarian reform, movement leaders considered mobilization in the country’s poverty-stricken northeast to be a particularly important step to transforming the regional movement into a national one (see Petras 1997; also see Fernandes 1999; Stedile and Fernandes 1999; Navarro 2000; Robles 2001; Branford and Rocha 2002, p. 21; Wright and Wolford 2003).

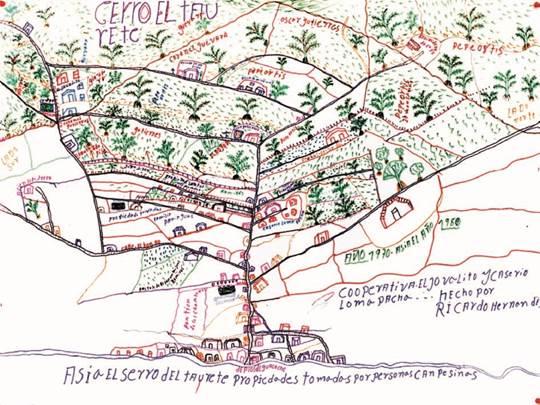

As sugarcane elites went bankrupt and MST leaders militated for land reform, the state government of Pernambuco expropriated 27 former plantations and distributed them among former workers and MST squatters (Buarque 1997; MEPF 1998). Seemingly overnight (although in fact it took much longer than that), sugarcane plantations were transformed: rural workers whose very identity had been produced through the hierarchical spatial and social segmentation of sugarcane production were given ownership of equal areas of land and theoretically turned into small farmers.[1] On one settlement, which I call Flora, in the municipality of Agua Preta, 46 families were given access to land in 1996.[2] The beneficiaries included the wife and son of the former patrao (literally translated patrao means patron or boss; in Flora’s case, the boss was renting the land from a nearby sugarcane factory), the elite administrative workers, the common workers, both legal and undocumented (the latter being those who were employed on the plantation without their legal working papers, an occupation category increasingly common after stricter labor compensation laws were passed in 1963), house servants, and the MST squatters who had occupied the property months before to press for its expropriation.[3] Agua Preta is in the heart of the southern sugarcane region in the state of Pernambuco and in 1999 had both the highest concentration of land ownership and the highest number of land reform settlements in the state.[4] The municipality is almost entirely dependent on sugarcane (and largesse from the mayor’s office) for employment and production, and the economic crisis of the 1990s hit everyone hard.[5]

When I first visited in 1999, national, state, and local MST leaders considered both Agua Preta and Flora to be strongholds of MST support and membership. When asked where I ought to locate my field research in Pernambuco, MST leaders suggested Flora as exemplary of the movement’s success in the region.[6] The entrance to the small grouping of houses that marked Flora’s center boasted a bright red MST flag, and movement activists were leading the monthly association meetings and organizing public demonstrations.[7] One such demonstration in September of 1999 brought over 200 rural settlers together from around Agua Preta to protest long delays in the release of state-subsidized production loans. The settlers were trying to move away from the regional specialty, sugarcane: at the urging of MST leaders, they were planting subsistence crops as well as bananas and coconuts for the market.

Four years later, however, the political and economic landscape looked very different. The price of sugarcane had increased to more than twice its low in 1999 and local factories were now paying approximately R$35 for a ton of cane, as opposed to between R$12 and R$15 in 1999.[8] Most of the settlers on Flora had gone back to work in sugarcane. The projects for bananas, coconuts, and cattle had not been very successful, and when the opportunity to work with sugarcane came up, they took it. The settlers were, in the words of one settlement president “dying of hunger” as they planted sugarcane again — either on their land or in the mills around Agua Preta. The MST was no longer Flora’s official political representative and the movement generally regarded its position in the region to be in crisis.

These changes that took place on Flora could be understood as rational responses to the changing price of sugarcane: the former rural workers left the movement because they no longer needed it, they could now earn their living planting sugarcane for the regional market. Or the changes could be understood (as the MST leaders understood them) as examples of false consciousness: the settlers were pulled back into sugarcane production because they could not free themselves from the hegemony of the plantation system. In some ways, both of these arguments are valid — planting sugarcane could be considered a rational response to changing prices, particularly in the context of the generalized dominance of sugarcane in the region. The difficulty with both of these arguments (and in fact, with the theoretical frameworks used to understand political consciousness), is that they rest on two problematic — if sometimes correct — assumptions.

The first assumption is that the MST was in crisis because people who had formerly belonged to the movement subsequently dropped out. Movements are generally believed to consist of members who join and drop out with precision (such that the movements succeed and fail in the same fashion). In fact, many people who “join” movements do so with some skepticism or even reluctance, ignorance, and bad faith — and many “leave” the same way: we cannot read political beliefs off of group membership. The rural workers on Flora had all believed they were part of the movement in 1999, but they were far from “ideal” members: they participated in demonstrations and state meetings, but they didn’t always understand that the movement was supposed to be composed of landless rural workers, not simply for them. In the same way, although none of the rural workers I interviewed on Flora in 2003 said they still belonged to the MST, not all were convinced that the movement’s withdrawal from local politics had been a good thing. The thick lines between inside and outside that social movements draw for strategic reasons (and that observers sometimes draw for political or solidarity reasons) are rarely — if ever — mirrored on the ground.

The second problematic assumption is related to the first. Both rational choice and Marxist attempts to understand consciousness assume an intentionality (people do things because they mean to) that is common of social movement theories in general. Although social movement scholars are bringing people, agency, and emotions back into the analysis (Auyero 2003; Wood 2003; Jasper 2004) and correcting for what has been called the structuralism of classical social movement studies (Goodwin and Jasper 1999; McAdam et al., 2001, p. 18), the focus on intentionality draws new lines in the sands of liberal subjectivity: people either join (and leave) social movements because they want to, usually because they decide it is in their best interests (they get fed up, they want to maintain their reputation, they believe in the cause), or they join and (more often) leave because they are manipulated or swept away against their will by people who decide it is in their best interests. Both of these positions assume a market-place of ideas and decision-making that invokes Liberal economic theory: believing in agency has come to mean believing in intentionality. At the risk of being cited for bad puns, one could say: the path to social mobilization has been paved with intentionality. Whether the focus is on the “people” who engage in collective action or on some set of hegemonic representatives (in this case, the sugarcane elites) who manipulate others, someone is making decisions with access to perfect information and in competitive political markets.[9] When we come across “informants” who contradict themselves, or who can’t explain their own motivations, we think of it as “noise” and it gets edited out: nonsense, by definition, does not make sense.

Instead of editing out these “unreasonable” answers, we need to add what Lila Abu-Lughod (2000, p. 263) calls a “counter-discourse,” where people are “confused, life is complicated, emotional and uncertain,” to our analyses of social change and mobilization.[10] In addition to bringing culture into studies of social movements (Wolford 2003, 2005; Rubin 2004), we need to explicitly incorporate that aspect of culture best described as “common sense.” Following others, culture can be conceived of as a continuum running from informal to formalized expressions: common sense, tradition, ritual, and ideology, where ideology is expressed in (and demonstrated by) highly developed, well thought out declarations (textual and oral), and common sense is “the simple truth of things artlessly apprehended,” (Swidler 1986).[11] It is, in the Gramscian sense, contradictory, fragmented, and never autonomous from hegemonic ideologies. It is the realm of culture that is most fraught with internal difference, most fluid (rather than contained within a recognizable group of people) and most readily changing in order to make sense of — and take advantage of — new situations (rather than rooted in tradition). The move to incorporate common sense does not mean structure, agency, and explanation should be abandoned in studies of social movements.[12] Rather, our ability to explain movement trajectories over time depends on our ability to incorporate common sense into the analysis.[13] When asked in 2003 why they left the MST, the land reform settlers in Agua Preta responded in ways that were contradictory, incomplete, attempts to justify post hoc a set of decisions that had often been made without explicit articulation or even understanding. Incorporating this “noise” into our analysis of political consciousness helps to explain that the question one might ask in returning to the sugarcane region, “why did the MST fail in Agua Preta,” is too black and white: in fact, the MST did not fail entirely (just as it did not succeed entirely), and the movement may even have planted the necessary conditions to rebuild its presence again. There was enough uncertainty and mixed emotions among the land reform settlers to suggest that if the movement becomes a strong political actor again in the region, at least some settlers would swear they never left (and perhaps they never did).

This sort of study requires an appropriate methodology: an analysis of contradiction, silences, and confusion can only be done through what Gillian Hart calls “advancing to the concrete” and employing the sort of political ethnographies that are the subject of this edited collection. Political ethnography has a dual meaning: it refers to the politicized nature of ethnography as a method that is uniquely suited to examining and exposing the power relations that inflect all social life. At the same time, it refers to the need for (and practice of) ethnographic investigations of politics, where elections and states are no longer the privileged site of political life, rather people are. This attention to location (rather than the local, see Gupta and Ferguson 1997, p. 39), to lived experiences (rather than rhetoric, see Burdick 1995; Edelman 2001, pp. 309–310) and to (un)intentions (as opposed to simply action, see Ortner 1995; Wolford 2003) will enrich our ability to understand and explain social movements. In the body of this paper, I use the textual tools of Pierre Bourdieu’s (1991) Weight of the World to work through two interviews conducted with a rural worker turned land reform settler on Flora, in Agua Preta, Pernambuco, Brazil.[14] He was formerly a “common worker,” not an administrative (elite) employee or an MST squatter. I call him Cicero although that is not his real name. The interviews were conducted in 1999 when Cicero said he belonged to the MST and in 2003 when he no longer “knew what to say about the movement.” The first interview was situated within the context of my seven months in Agua Preta. I also visited the area and met informally with the settler in 2001.

Cicero is not the kind of social movement member who usually finds his or her way into a study: he was not vocal in his opinions, he was not the “model” member on the settlement to whom researchers were told to speak, nor was he a contrarian who walked away from meetings (or the MST) in disgust and waited for his chance to “tell all” to the American researcher on the settlement. To the contrary, Cicero was quiet, he was uncertain what to think about the movement, and he rarely picked sides in a disagreement. In this, he was perhaps representative. His reasons for joining and leaving the MST resonated with the silent majority of settlers on the settlement (silent because they do not speak out or are not asked).

Analyzing Cicero’s discussion of why he joined — and then left — the MST leads to four key points. First, the confusion and contradiction Cicero presents cannot be easily dismissed as mistakes or unimportant; they are part of his attempt to reconcile his personal circumstances with the way he imagines the world ought to work. Second, the uncertainty Cicero feels about leaving the MST highlights the fuzziness of movement membership more generally — within any given movement, there are varying degrees of engagement, and interviewing along the continuum provides us with a more representative picture of movement politics than simply interviewing movement addicts and elites. Third, the pride that Cicero feels in owning his land has to be situated in a longer history of “captivity” on the plantations: as a former plantation worker, he feels a new freedom. For movement leaders, this freedom means freedom from the dominance of sugarcane, plantation elites, and the state, but for Cicero, freedom means being able to allocate his own labor time and to work where he wants. Freedom, for Cicero, means the right to reject the MST’s advice and ultimately to withdraw from the movement. Fourth, and finally, Cicero’s discussion of politics on the settlements highlights the extent to which participation in the MST laid the groundwork for future political participation. Even if the movement itself never regains its political strength in the region, the tools of participation that movement activists laid down will certainly be used again. Social movements may come and go, but they build on and generate broader repertoires of contention; these repertoires are easily missed if we privilege the movement as a bounded, easily defined object of study.

In presenting and analyzing Cicero’s interviews, I am not suggesting that he “speaks” in a way that is representative or original and therefore authentic or necessarily insightful. I am using his words to highlight the fluidity and contradictions of social movement membership and identity. He spoke for himself in our interview but he does not necessarily do so in this text. The interviews have been structured both by my presence and by the interview format, and the text was structured afterwards through analysis and academic publishing conventions.

Cicero, July 31, 1999

Cicero is a short, sturdy black man, perhaps the darkest man on Flora. He was singled out for his color in the casual, even affectionate way that people are in Brazil. People called him the “little black one,” and when Cicero worked in the neighboring mill before receiving land on Flora, the other men knew him as “Amaral,” the name of a nationally known soccer player who was as dark as he. Cicero was very friendly, with a quick smile; and unlike many of the former rural workers, he always looked me in the eye when I talked to him. I interviewed Cicero on the porch of his new house inside Flora, a fast but dirty walk along a red clay path from the settlement’s center. Cicero did not live in the house where we sat; he and his family had a little house in the town (na rua) of Agua Preta. When he received the government funds earmarked for housing, he built the brick house by the small stream that ran through his property. Cicero had planted manioc along the hillside behind his house, and he grinned broadly as we walked around his plot of land. Cicero’s wife and children were not with us during the interview; he had been walking alone to his house when I caught up with him. He said his wife weeded with him, but only occasionally. If the settlement ever got electricity, as the mayor had promised, Cicero said he would move the whole family into the new house.

Cicero remembered his life before the present without details. He was born in the mill where his parents lived, on a sugarcane plantation. When asked “what was it like,” he seemed uncertain of the question and answered as someone who did not feel they had the luxury of choosing the broad strokes of his life: “It was what we had to do, wasn’t it? What else were we going to do?” The family didn’t have land of their own, though they were sometimes allowed to plant garden crops on the land near their house. Access to land for planting had once been a regular condition of tenancy, or moradia, where workers lived on the plantation and worked a certain number of days per week in return for land to plant and a house to live on. The tenancy relationship was severely eroded after the 1960s when national legislation extended formal labor rules to the countryside and informal “gifts” such as access to land were increasingly unavailable (Juliao 1972; de Andrade 1988; Pereira 1997). In the 1970s, new government subsidies increased production, and it became even harder for workers to find land for their own subsistence.

After the transformation in tenancy norms, Cicero’s family displayed a mobility that has since become common to the sugarcane region: people exercise their “right” to leave a plantation when working conditions are deemed unbearable. From the point of view of the workers, this mobility offers some freedom in their otherwise highly circumscribed lives.

When he was very young, Cicero’s family moved around from mill to mill in the southern sugarcane region of Pernambuco until they ended up at a mill called Jotoba where his parents both cut and weeded cane. His father always liked their old bosses and never made trouble. Cicero said the boss at Jotoba was a good man because when his father died, his mother was hired to work in the Big House. Workers in the Big House were often treated “just like family,” in the region’s paternalist system of labor relations. Cicero’s mother eventually remarried and the whole family went together to yet another mill named Barro Branco.

From Barro Branco, Cicero began working in the mills on his own. He was seventeen years old when he began gathering sugarcane (cambitando) in the large trucks to take to the distillery. He liked working with the trucks because it was easier than working in the fields, “the cane cutter or sharecropper is more beaten down, he has to cut a ton of cane just to earn four or five reais.[15] For people who are good with a scythe, you can cut two or three tons a day. And I can make this much money with just one or two trips with the truck, depending on the truck. If the truck was well-built, well, there were trips when I would earn R$5.00 just on one.” Cicero always lived on the mills where he worked and remembered his bosses giving him land to plant. He liked his bosses well enough, saying cryptically that “I don’t want to see a boss for any reason when things are going well, I only want to see them when someone in the family is sick.” By the time I met him, Cicero had a world-weary sense about him, having already been “all around this world, my god! I’ve already lived in Jotoba, Pamosca, Ferrao, in Alagoas, Espinheiro also in Alagoas, Japaranduba, which is next to Palmares, and other places too.” He had been married for more than 20 years (he said with a grin, “I love my little old lady a lot,”) and he hoped to stay put for a while: “Now that I have this little house here in Agua Preta, I’ve settled down. Here, what I have is mine: this was my dream. And thank god I will stay here for the rest of my life.”

When Cicero arrived in Agua Preta, he worked on the mill that would become Flora. He worked as an undocumented worker (clandestino), hired by the man who had been renting the property — about 450 hectares of land, since 1982. “In those days,” when Cicero first arrived, the fields were well-planted: “It was full of cane here, some 100 people worked here... [The former renter] was planting, and all these mills around here were full of cane.”

After six years of working illegally, Cicero received his working papers. He began working with the cattle, planting cane for feed and tending to the animals. This was roughly when the plantation “began to go bankrupt, [the boss] brought himself down. He went under.” In 1993, most of the settlers on Flora agreed, the renter stopped planting sugarcane. He harvested a second and third growth from the cane already in the field (called ratoons), but was unable to maintain production in the face of reduced government subsidies and falling world sugarcane prices. This was the beginning of the industry-wide crisis in Agua Preta. It was also the beginning of the demand for agrarian reform and the MST’s political presence in the region. The MST was only one of several organizations pushing for land distribution, but they were the most committed to aggressive action and arguably forced the rural trade unions, the Catholic Church, and other social movements to take up the cause. The MST had actually begun organizing in 1989, but local leaders initially had trouble mobilizing support among rural workers who were embedded in very different land-labor relation than the family farmers of southern Brazil where the movement began (Wolford 2003).

In the mid 1990s, MST leaders and members joined the state agricultural workers’ federation, FETAPE, in a massive occupation of the largest sugarcane operation in Latin America. The distillery, Catende, had been a site of political dispute since 1993 when 2,300 people were summarily laid off. In 1994, the mill stopped paying its still-employed workers their legally mandated “rights” (direitos) which included back pay, bonuses, fines for late payments, unjust termination rewards, and holiday pay. By 1995, political protest had resulted in the expropriation of several mills belonging to Catende, but most of the squatters affiliated with the MST were not eligible for land (the unemployed former workers were given first priority), and they moved on to occupy new plantations. In 1995, 13 families arrived on Flora after having occupied other mills nearby and camped out alongside the street under their black plastic tents. On Flora, they occupied a small riverbank in the interior of the plantation. At that time, the land was not actively productive: “Not at all,” Cicero said, “they weren’t planting anything here at all.” The National Institute for Colonization and Agrarian Reform (hereafter INCRA) had actually evaluated the property during the faint-hearted agrarian reforms of the 1970s. The property was slated for expropriation then, but nothing happened for over twenty years. The owner remained in debt to the state for nonpayment of loans received, and the land was rented out to medium-sized sugarcane suppliers. After three nonviolent (but difficult) expulsions, the federal agrarian reform agency (INCRA) expropriated the property on March 7, 1996. Cicero learned late that the expropriation was finally going to go through: “I didn’t even know about it, I only came to know after they had already signed everyone up. But then there were three people who didn’t want the land, and so I threw myself into the middle, thank God. I am very grateful to the administrator here. He gave a push for me to get this land.”

Cicero had never owned his own land before, and he thought that the expropriation was a good idea: “I thought that I would have a little piece of land to plant on. I said to myself that I wouldn’t have to live any more on anyone’s back (as custas de seu ninguem). Because we used to spend all of our time battling for other people. You arrive one day, and that day they have work, the next day you go back, and then there isn’t any. When I got my piece of land, I considered myself a man rich in the grace of God. Because here I work when I want, no one is going to look at me, whatever I want to plant, whatever I want to do here in my house, no one is going to beat me up, because it’s mine. They gave this to me free and clear.” Cicero repeatedly expressed his relief in no longer having to beg for the handouts that are a common feature of the paternalistic and poverty-ridden political culture in the Northeast: “After I arrived here in Água Preta, I worked in the summer for the person who rented the mill, but in the winter I was always unemployed. I got tired of always standing in the doorway of the city council, abusing this person or the other, or the mayor, getting money to do the weekly shopping from one person, getting R$100 from another. Today, thank God, I don’t need this.”