To cite this article: Leah M. Wyman & George N. Dionisopoulos (1999) Primal Urges and Civilized Sensibilities: The Rhetoric of Gendered Archetypes, Seduction, and Resistance in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, Journal of Popular Film and Television, 27:2, 32–39, DOI: 10.1080/01956059909602802

Leah M. Wyman & George N. Dionisopoulos

Primal Urges and Civilized Sensibilities

The Rhetoric of Gendered Archetypes, Seduction, and Resistance in Bram Stoker’s Dracula

“If there hadn’t been women, we’d still be squatting in a cave eating raw meat because we made civilization to impress our girlfriends,” claimed Orson Welles (qtd. in Gossett 20). This quotation is typical of a “gendered ideology,” which dichotomizes male and female natures by associating that which is civilized with the feminine, and that which is uncivilized with the masculine. That ideology underpins the belief that it is the social role of women to provide a calming effect on male aggression through setting and reinforcing boundaries concerning “appropriate” male behavior. This results in an expectation that a woman in an intimate heterosexual relationship should take on a kind of mothering role, limiting the threat posed by the man’s essentially masculine nature.

In this article, we explore how societal framings of gender that link masculinity to innately primitive, primal urges and femininity to the delicate, civilized sensibilities are embedded in cultural myth and folklore. We analyze Bram Stoker’s Dracula to offer insight into how such gendered archetypes are portrayed in popular filmic versions of folklore. We examine Bram Stoker’s Dracula because it is the most recent retelling of this classic story, which has been presented through various media throughout history. We have elected to use the screenplay—as opposed to the film itself—for two reasons. First, the screenplay includes the entire script, including all the dialogue used in the film. Second, the screenplay includes important commentary from the two creators of the film: writer James Hart and writer/director Francis Ford Coppola.

We begin by exploring how mythic archetypes of gender are expressed in popular theories, perspectives, and social trends. Then we examine how popular films draw on and perpetuate cultural myths. And, finally, we examine Bram Stoker’s Dracula, focusing on how the Dracula legend employs those gendered mythic archetypes.

Primal Men, Civilized Women

One common cultural myth concerning gender asserts that men have difficulty controlling their aggressive, indulgent, destructive impulses. This myth suggests further that it is the job of women to provide a mothering role in male-female relationships. To calm men’s antisocial tendencies, women are charged with setting and reinforcing limits, which help men behave responsibly. The association of masculinity with primal, primitive urges, and femininity with delicate, civilized sensibilities results in dichotomous archetypes of men and women, which are often rationalized as being the “natures” of each gender and biologically determined. Variations of that myth have appeared in mainstream theories and popular social movements that focus on defining “appropriate” gender roles in society.

For example, scholars have pointed to beliefs of this sort as the foundation for Robert Bly’s book Iron John and the corresponding men’s movement that it sparked. Although acknowledging that men would benefit from inclusion in a movement that seeks to dissolve patriarchy, Ruether observes that Bly’s work did not constitute such a movement. In fact, its philosophies actually strengthened the foundations that keep patriarchy in place. As Starhawk notes, a real antipatriarchy men’s movement would question male socialization by asking questions such as, “How are [men] conditioned to be good soldiers? How can they undo that conditioning, and redefine manhood as to further creative, not destructive power? ... [T]hese issues would tie into all the divides that still lie between women and men, into the deep issues of violence and sexual violence that are bred by war” (34). Adair argues that the men’s movement that grew out of Bly’s work reconfirms the status quo by beginning from the premise that men are innately aggressive and territorial.[1]

Jane Caputi and Gordon MacKenzie explain that Bly’s work was in the form of a “fairy tale,” offering engaged male audiences a model of masculinity that they could relate to and strive to emulate. The main character in this story is referred to as the “wild man” and is described as being repressed by modem culture. Bly helps men connect with this fictitious character, thereby facilitating their efforts to reclaim their male identity. In ritualized “retreats in the woods,” men “create privatized selves and disavow responsibility for the public world” (Ruether 17).[2]

Bly’s wild-man definition of masculinity supports the cultural myth of the primitive male by presuming that an untamed nature is unique to men and that its expression is paramount to male self-actualization and happiness. As Ruether states, this suggests that “males should deal with their masculinity by recreating puberty rites in sylvan settings ... [and that] by reclaiming a strong, masculine psyche, men can heal their wounded masculine identity” (16).

Bly’s take on gender further fits the myth by suggesting that men’s identity conflicts stem from the overinfluence of mothers and, thus, femininity. Bly maintained that because many men grow up with fathers who are either uninvolved or completely absent, the male psyche is watered down by an overload of mothering. Therefore, the proposed “solution to men’s problems is to relive this adolescent struggle to free himself from his mother” (Ruether 16). Eisler described this “old macho script ... in New Age clothes” thus:

Once again in accordance with the dominator requirements, male identity is defined in negative terms, as not being like a woman. As in the old macho script of contempt for the “feminine,” Bly berates his followers for being “too soft” and thus “unmanly.” To this end, men must even distance themselves from their own mothers, lest, in Bly’s words, they be controlled and contaminated by “too much feminine energy.” (48)

That coincides with the mythic archetypes of gender in two ways. First, it defines the masculine as being the complete opposite of the feminine. Second, it suggests that femininity, and by extension, women, seek to control and set boundaries on masculinity and men, thus perpetuating the idea that it is the nature of men to act according to their inherent aggressive tendencies, and the role of women to try to curtail those actions.

Erica Burman finds this interpretation of gender in discourse used to describe childhood and child development. She observes that the state of childhood itself is often described in feminine terms and associated with “innocence,” and the process of maturation out of childhood—in which one is curious, experimenting, and prone to testing the limits of appropriate behavior—is detailed in masculine terms. As she observes,

Significantly, in terms of cultural associations, the category of childhood is feminine, but “youth” is masculine. The real children who were the object of the social and legal gaze were primarily male, those boys and young men considered likely to be “delinquent,” who constituted a threat to the social order. (50)

This suggests that not only is adolescent behavior categorized as male, but it is also viewed as socially unacceptable, and a threat to the social order. Therefore, for males, developing out of adolescence and into adulthood could be interpreted as a continual effort to be self-disciplined, despite an inherent “delinquency.” The phrase “boys will be boys” serves to rationalize certain “inappropriate” behavior and indeed suggests that it is an inseparable part of the male condition.

Susan Lydon discusses the dichotomy of presumed masculine and feminine natures in frames of human sexuality. She asserts that in the limited biological knowledge of the Victorian era, it was concluded that because male sexual pleasure was necessary for reproduction and female pleasure was not, sexual pleasure was the sole province of men. Thus labeled, it was defined in exclusively male terms and alienated from women. Women, she writes, were kept “submissive to sex by creating a mystique of the sanctity of motherhood; and, supported by Freud, passed on to us the heritage of the double-standard” (202).

Bemie Zilbergeld writes that this labeling of sexual pleasure as masculine, facilitates its coupling with other masculine traits, including the reckless aggression noted earlier. He observes that the mixing of male sexuality with dominance was a confirmation of male identity, and that men are taught that violent sexuality is a natural part of maleness. As examples of that socialization, he cites slang terms used to refer to a penis, including “weapon, tool, rod, ram rod, battering ram, and formidable machine” (28), all of which connote aggression, and in some cases, violence.[3]

It is important to note here that these mythic archetypes of gender, which masculinize the “wild” instincts, can also be found in the writings of those who claim to adopt a feminist perspective. One example would be Starhawk’s description of the “Horned God,” one of the idols worshiped by the pagan-witchcraft community to which she belongs:

He is the Stallion, swift as thought.... He is the moonbull, with its crescent horns, its strength, and its hooves that thunder over the earth ... yet he is untamed. He is all that is within us that will never be domesticated, that refuses to be compromised, diluted, made safe, molded, or tampered with. He is free. (Spiral Dance, 100)

Thus, even Starhawk, who describes herself as pro-feminist, matriarchal, and female-affirming (Spiral Dance), ascribes to the Homed God the qualities culturally affirmed as male. He represents the “untamed” male spirit.

Judith Walkowitz suggests that women sometimes co-opt patriarchal constructs of gender because those frames are so deeply ingrained and embedded in the cultural consciousness. As she explains, women “are not innocent because they are on the sidelines. They are bound imaginatively by a limited cultural repertoire, forced to reshape cultural meanings within certain parameters” (9). Thus, stereotypes of gender may be perpetuated by both the men and women.

Carol Travis finds gendered archetypes in the work of various feminists. She writes that the ecofeminist philosophy, which combines ecological perspectives with feminism, contrasts the warlike, aggressive, and exploitive character of men with a more peaceful, nonaggressive, and connected-to-nature character that is attributed to women. Travis also notes that feminist psychoanalysis sometimes adopts that perspective by portraying men as more emotionally aloof and women as naturally more emotionally connected. These perspectives emerge from our tendency to divide things into binary opposites, such as good-bad, us-them, masculine-feminine. That allows a simple categorization that is not encumbered by shades of gray.[4] Travis observes that when that polarity is projected onto gender, stereotypes emerge that overlook both differences and similarities As she describes it:

Thinking in opposites may be a comfortable habit, but the results are often hazardous to our relationships, social policies and private lives. For one thing, it twists our way of talking about differences that do exist between men and women into stable, permanent qualities. It is not, thank God, a blueprint for life. People develop, learn, have adventures and new experiences; and as they do, their notions of masculinity and femininity change too. (91)

Travis suggests further that the myth of inherent male aggressiveness may also be mistaken. It is based on cultural notions that men are warlike and women are peaceful. But the historical fact that women have not fought in wars can be attributed more to the lack of opportunity than to a lack of interest. Travis comments that women frequently endorse war in whatever ways they can: as “combatants, defenders, as laborers in the work force to produce war materials, as supporters of their warrior husbands and sons” (67). Similarly women are as capable as men of adopting the mentality that makes them “co-conspirators of war” (71). That is, they are as likely as men to dehumanize the enemy in war, referring to them as animals needing to be exterminated.[5]

Lastly, Travis highlights the notion that portraying women and men as opposites lays the foundation for tension and animosity between them, in that dichotomies inevitably produce debates over which is better or worse, right or wrong. She claims that it would be more productive, and accurate, to view stereotypical male and female qualities as “potentials in human nature” (2).

To the extent that these mythic archetypes of gender are rooted in culture, we could expect to see them being reaffirmed and sustained in popular media. We turn now to examine how the media—primarily popular film-—have become part of the mechanism that draws on and perpetuates cultural myth.

Film and Cultural Myth

Caputi and MacKenzie observe that mass media can help create cultural myth and ritual by telling and retelling stories that reinforce common values, define what is normal and what is deviant, and make implicit social structures explicit. Thus, media can play an important role in forming the individual and collective psyche of a culture. As Nimmo and Combs point out, mainstream films, in particular, can offer “cultural tales [with which] people readily identify,” creating and reflecting accepted fantasies concerning audiences and the environment (107). The large audiences reached by popular film mark it as potentially a very influential medium. Shirley Weitz explains this power by noting, “Personalities and situations portrayed in [film] become a part of our popular culture.... [F]ilm can transmit ideas and images to millions of people at once; their symbolic language becomes our language, their ideas and ideals, ours” (179).

Jerry Farber echoes this observation by noting that artistic expressions can create “remembered experiences” to which audience members mentally refer when confronted with similar situations in their own lives. Thus, the characters and situations observed in films become part of our repertoire of memories through which we make sense of our world. The mere process of watching people and situations being presented as spectacle in film can cause a kind of benign acceptance of what is being depicted. As Farber stated, if “we perceive something aesthetically, doesn’t it mean that for that moment at least, we accept it? Not accept it as good, necessarily. Just accept it: ‘that’s the way life is ... ;’ this would make it the bosom friend of the status quo ... [and] allow it to redeem itself as spectacle” (167–68).

This effect is particularly persuasive when the concepts being presented coincide with what the audience already believes to be true. Thus, Farber (1982) concludes that film is best understood in relation to its ability to embellish attitudes already in place and inspire behaviors for which the seeds have already been planted, rather than prompting new individual attitudes and actions.

Hart contends that “messages bear the imprints of social situations that produced them” (60). To the extent that this is true we could expect to find mythic archetypes of gender in popular film representations of cultural folklore. Indeed, Dan Kiley notes that dichotomizing gender into wild men and refined women is prominent in Peter Pan. He writes that men stuck in the “Peter Pan syndrome” refuse to grow up by continually acting like adolescent boys—tending to be undependable, rebellious, angry, manipulative, and narcissistic. These “Peter Pans” find “Wendy syndrome” women to take on the required mothering role of caretaker and rationalize the care they give by thinking the man is incapable of caring for himself. Kiley suggests that indeed the man is capable but simply does not wish to care for himself, because doing so would mean leaving never-never land and assuming the responsibilities of adult status.

Another filmic depiction of this theme is Disney’s version of Beauty and the Beast. The character of Beauty, like Wendy, is intelligent, loving, and maternal and devoted to caring for her widowed father. The Beast in the story reflects many of the same male qualities exhibited in Peter Pan. As Elizabeth Gray states, “there is a clear mythopoetic representation of the man who is totally preoccupied with his own salvation, who is prone to violence, and still very much ‘under the spell of enchantment’” (160).

Significantly, only the love of a woman can break the spell, implying that only a woman can end his “beastliness” and return him to his more gentlemanly form. Thus again, the good-natured female is to undertake the job of transforming the frighteningly untamed male. Gray concludes that this suggests women’s “savior role ... in breaking the enchantment of patriarchy” (163). Although that feminist interpretation is appealing, it still presumes inherent natures of men and women that revolve around traditional stereotypes, delegating some qualities to one and some to the other, solidifying the notion of men and women as polar opposites.

Carol Travis notes the role that stories play in transmitting and reinforcing cultural myths within a society. She observed that we “develop and shape our identities in the narratives we tell about our lives” (307). Walter Fisher echoes the power of stories, suggesting that we “arrive at conclusions based on ‘dwelling’ in dramatic and literary works. We come to new beliefs, reaffirmations of old ones, reorient our values, and may even be led to action” (158).

If it is the case that filmic portrayals of gendered archetypes serve to strengthen societal beliefs concerning “proper” gender roles, it is important that we deconstruct those narratives to reveal “who benefits from the official theories and private stories we tell? Who pays? What are the consequences?” (Travis 289). Analyses of gendered archetypes in popular film can help illuminate the cultural foundations on which they are based. Once unveiled, those foundations can be examined in terms of how they may function to preserve cultural values and ideals and affect individual and collective thinking and behaviors. For as Steele and Redding point out, once internalized, cultural values can be translated into guides for proper action and premises for accepting or rejecting the arguments one encounters.

We examine the gendered archetypes in Bram Stoker’s Dracula —the latest version of a story that has been retold many times, in many forms. As noted, this implies that it has reached the level of mythic folklore, suggesting that it could be a signifier of cultural beliefs, thus making it an excellent object for a case study. Our analysis is informed by Foss’s observation that criticism “done from a feminist perspective ... is designed to analyze and evaluate the use of rhetoric to construct and maintain particular gender definitions for women and men” (151). Foss describes feminist criticism as including the analysis of concepts of gender presented in the artistic artifact and discussion of the effect that the artifact’s notion of gender may have on its audience. One artifact that did, indeed, “construct and maintain particular gender definitions” was Bram Stoker’s Dracula.

Gendered Archtypes in Bram Stoker’s Dracula

Vampire Eroticism

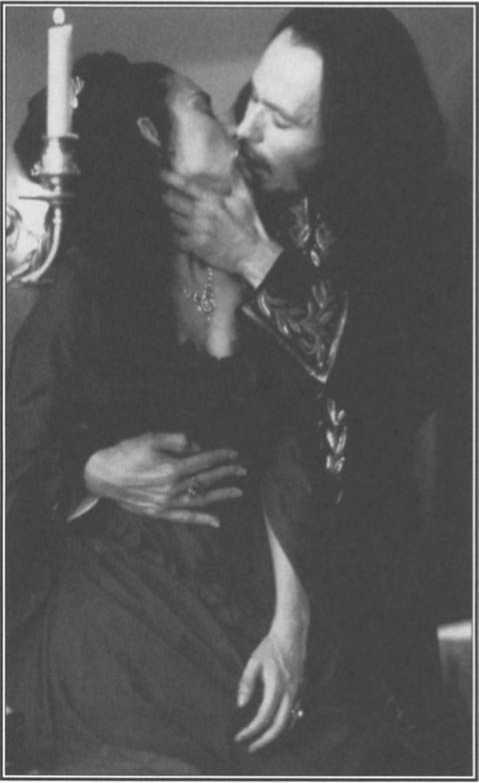

“Vampires seduce us and take us to dark places and awaken us sexually in ways that are taboo” (Coppola and Hart 136).[6] As this quotation from screenplay writer James Hart suggests, vampires in general, and particularly in Bram Stoker’s Dracula, represent a form of sexuality that contrasts with socially acceptable expressions of sexuality. Yet it is also presumed to be an innate part of human desire, which we subconsciously want permission to express. From this perspective, Dracula represents that permission by providing his victims with a vehicle to express this forbidden impulse; a vehicle that civilized society is both unable and unwilling to provide. Hart’s phrase “awaken us sexually” implies that the violent sexuality offered by Dracula is present, but dormant, in humans and needs to be awakened.

This lethal sexuality is defined as inherently male, as evidenced in the story by the fact that all of the female vampires become vampires when they are attacked by the story’s only male vampire, Dracula. In that vampirism is being shown as only passing from man to woman, the female vampires are only relevant to the story in terms of how they relate to Dracula. For instance, Dracula’s brides are only defined as such, never given names, and Dracula is never referred to as their “husband”; in fact, they refer to him as “master.” Lucy and Mina, the narrative’s two human females who are seduced by Dracula, are depicted as mistress and wife to him, respectively. At one point Lucy is referred to as “the devil’s [Dracula’s] concubine” and Mina as “the bride my master covets.” Because Dracula transforms all the women in the story into vampires, the assumption can be made that vampirism—including its violent, sexual nature—originates in him. Thus although it may be passed to women, it is initially and innately masculine. Dracula defines each woman’s vampire identity; they do not define his.

Besides being defined as masculine, vampirism is also constructed in opposition to purity and righteousness, and thus as a threat to society. As noted in the screenplay, Stoker’s “vampires represent, among other things, the rampant libido.... Stoker’s human characters ... are irresistibly drawn to them—but if they surrender, they are doomed. Only death and a holy ritual of exorcism can save their souls” (136). Additionally, director Coppola refers to Dracula’s three brides as a harem, suggesting-that if Mina is transformed into a vampire she would be wife number four. As the antithesis of a traditional, monogamous lifestyle, Dracula’s more closely reflects an “uncivilized,” stereotypic male fantasy: one man with several lovers, requiring loyalty to none.

The forbidden nature of vampire sexuality—conflicting as it does with fundamental social mores—is further echoed in scenes using a snake, the biblical symbol of female temptation and seduction. In one scene, Dracula is described as coming to Mina in the form of a green mist that “enters through the window, down [the] wall, to the end of the bed. Then up the bed, following the bulge under Mina’s sheets, coiling toward her like a serpent” (132). The snake symbolism is also used in the costuming of Mina and Lucy. As it is described, “Lucy and Mina wear similar green dresses in a party scene, but the embroidery—Mina’s of leaves and Lucy’s of snakes—differs significantly” (127). The relation of the snake to Lucy presages that she will be the first to be seduced by Dracula. The danger of the snake is confirmed when she is ultimately killed for her transgression.

The shame of indulging in Dracula’s eroticism is quickly felt by Lucy. The first scene, in which Mina discovers Lucy after she has been attacked by the vampire, is described as follows: “Lucy alone, breathing in heavy, orgasmic gasps; gown spread, revealing her breasts—her thighs. Mina runs into the POV [point of view], wraps her shawl about Lucy.” Lucy pleads, “Please don’t tell anyone—please.” The description of Lucy’s nudity combines with her evident embarrassment to confirm the forbidden nature of vampire sexuality.

The Violence of Dracula

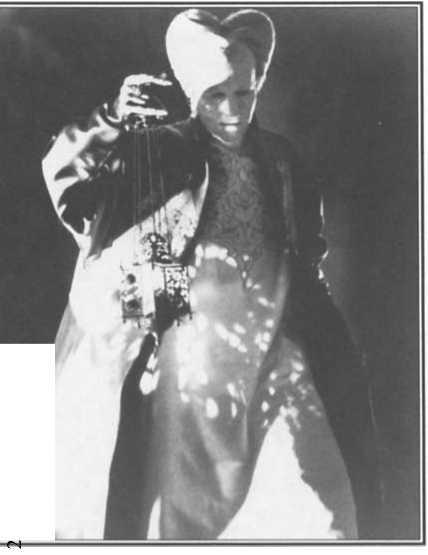

In addition to overt, decadent eroticism, Dracula also embodies brutal, unrestrained violence. As the film opens, Dracula, in his human, prevampire state, is leading troops into battle. As the scene depicts men being impaled on wooden stakes, a narrative voice-over describes:

From Transylvania arose a Romanian Knight of the Sacred Order of the Dragon—Vlad the Impaler—known as Dracula. A renowned military genius, his blood-thirsty ways were notorious throughout Europe. In a bold surprise attack, he led 7,000 of his troops against 30,000 Turks. (12)

This visual image and narrative description define Dracula as fearless, aggressive, and warriorlike.

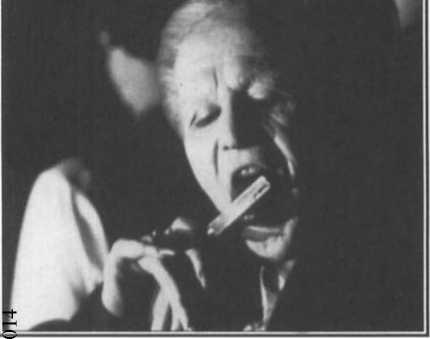

Later, his violent nature is displayed in the scenes in which he attacks Lucy. The description of the first scene of this nature is illustrative: “her arms pinned back, a dark figure, erect like a wet man or beast bends over her—mounts her between her legs, close up of fangs in Lucy’s bloodied neck” (71). That theme is replayed in the scene in which Dracula attacks Lucy for the last time, ultimately killing her humanness and changing her into a vampire. Dracula, in the form of a large wolf, flies in the window, lands on Lucy and tears her apart; “growing more erotic, with the wolf-Dracula ravaging Lucy ... we pull back to reveal that she is surrounded by white satin in a glass coffin” (112–13).

Dracula as Animalistic

Dracula’s image as the epitome of maleness is completed through the use of animal imagery that combines the “wild man” image offered by Bly with the untamed male spirit detailed by Starhawk.

Mina witnesses Dracula—in the form of an animal—attacking Lucy. As noted, he is a “dark figure ... wet man or beast” (71). When Dracula senses Mina’s presence, he is disturbed about her seeing him in this form, and says, “No ... do not see me.” Screenplay directions indicate that he is “very emotional about seeing her; almost stunned” (71). Thus, although Dracula’s character is primitive and barbaric—particularly when in pursuit of blood—Mina’s presence has a civilizing effect on him, symbolizing the feminine role to subdue male rage. Thus the film delegates to maleness the power of physical strength and dominance, as it simultaneously confers on women and femininity the power to calm males through goodness and decency. But because Lucy is easily seduced and revels in the erotic experience Dracula has to offer, she cannot calm his more “natural” animalistic tendencies. Only Mina— more “feminine” and more resistant to Dracula—can stifle his hypermasculinity.

Dracula’s animalistic nature permeates the screenplay. As Dr. Van Helsing states, “He can command the meaner things: the bat ... the rodent ... the wolf ... and all the elements” (124). Dracula himself comments on the connection between vampirism and the animal world. When he attempts to make Mina a vampire, he says to her, “I give you eternal life ... the power of the storm and the beasts of the earth” (134). This suggests that the impulsive, self-indulgent, violent, sexually charged world of the vampire is one of primal feelings that embrace men as “animalistic,” driven by the wild, perhaps even uncontrollable desires found in animals.

This same perspective denies the connection of “good” women to those primal urges, in that Mina must become a vampire to receive the gifts Dracula offers. Good women act to neutralize those primal, animalistic drives. When Dracula is with Mina, he strives to take on the form of a “polite, handsome gentleman.” He does not wish to act like an animal when he is with her.

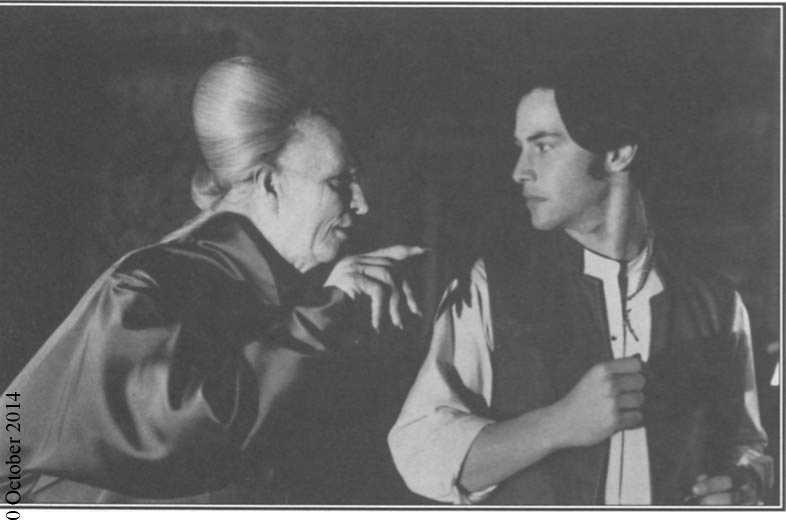

Mina as Savior of Humanity

When Mina and Dracula officially meet for the first time, he is a stranger to her and approaches her on a busy London street comer. When he asks her what tourists in town should see, she responds, “For lost souls, I recommend Westminister Church” (77). Holy water and crucifixes can destroy a vampire’s powers, so sending Dracula to a church associates Mina with the religious virtue that can overcome a vampire. This exchange sets Mina up from the beginning as Dracula’s one weakness, the one woman he cannot seduce or attack at will.

This is paralleled later in the story when Dracula attempts to feed off Mina, but finds himself unable to do so. As the scene is described, “He bends close to her, his fangs about to sink into her pulsing neck. He is astonished at the emotion he feels; his fangs recede” (84). Because the vampire’s bite is sexually connotative, the scene suggests he is impotent to inflict himself on Mina. In contrast, as the vampire kills Lucy he taunts her: “Your impotent men with their foolish spells cannot protect you from my power” (112). Thus, the story uses impotence to connote restrained male power, and male sexual potency to represent power, specifically violent, harmful power. This again suggests that violence and aggression are inseparable parts of male sexuality. Starhawk observes that Bly’s concept of men who have had their masculinity watered down by too much feminine influence reminds her of “the old male taunt ‘can’t get it up,’ or possibly ‘faggot’” (30).

Toward the end of the film script Mina asks to become a vampire. Dracula’s efforts to comply are depicted as follows: “He falters—tears welling up—suddenly fighting his desire. He shoves her back in anguish” (135). Because that ambivalence does not arise with any other character, it again highlights the effect Mina’s “female nature” has on Dracula.

Mina’s potential for stopping Dracula’s destructiveness once and for all is articulated by the character of Van Helsing. When Mina begins to change into a vampire she states that she would rather die than become a threat to anyone she loves. Van Helsing responds, “you must not die—your salvation is his destruction” (139). Thus Mina’s salvation—and indeed the salvation of all—lies in her resistance to Dracula’s sexuality; that is, her ability to place and enforce limits on the primitive, violent extravagances he represents. Only when Mina is purged of those primitive desires can she again become the epitome of the feminine: civilized, sensible, restrained. By setting limits on male indulgence, she can fulfill her role as the curtailer of wild behavior that jeopardizes the status quo.

In the end, Mina kills Dracula herself, relieving him of his vampire state, enabling him to rest in peace as a mortal. After she does so, a voice-over by Van Helsing states, “God be thanked that all has not been in vain—the curse has passed away” (164). Mina’s intervention has saved the culture from the threat posed by vampirism. It can now return to its civilized state, in which female propriety sets boundaries on male overindulgence.

Conclusion

We have offered an illustration of the persuasive potential of folklore for solidifying cultural presuppositions. Such stories can serve as vehicles for validating cultural beliefs and perpetuating the collective psyche of a culture. Specifically, our case study of Bram Stoker’s Dracula illustrates that the folk myth of vampirism is enmeshed with presumptions of innate male and female dynamics, presumptions that provide both expectations of, and rationalizations for, male and female behavior.

Mina’s killing of Dracula symbolizes the restoring of order and civility to the culture and thus an overpowering of primal masculinity by female sensibility. Through this ending, the narrative not only confirms the presumed inherent natures of the male and female conditions but implies a necessity for one to transform and contain the other. The example of Bram Stoker’s Dracula shows how film can perpetuate cultural myths of gendered archetypes and strengthen the premises on which they are based. We hope by our analysis to deconstruct these myths and so diminish their power.

Works Cited

Adair, Margo. 1992. “Will the Real Men’s Movement Please Stand Up?”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 55 – 68. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Burman, Erica. 1995. “‘What Is It?’ Masculinity and Femininity in Cultural Representations of Childhood”. In Feminism and Discourse: Psychological Perspectives, Edited by: Wilkinson, S. and Kitzinger, C. London : SAGE Publications.

Google Scholar

Caputi, J. and Mackenzie, G. O. 1992. “Pumping Iron John”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 69 – 81. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Coppola, Francis Ford and Hart, James V. 1992. Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend, New York : Newsmarket Press.

Google Scholar

Eisler, Riane. 1992. “What Do Men Realy Want: The Men’s Movement, Partnership, and Domination”. In Women Repond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 43 – 54. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Farber, Jerry. 1982. A Field Guide to the Aesthetic Experience, North Hollywood : Foreworks.

Google Scholar

Fisher, Walter R. 1989. Human Communication as Narration: Toward a Philosophy Reason, Value, and Action, Columbia : South Carolina UP.

Google Scholar

Foss, Sonja K. 1989. Rhetorical Criticism: Exploration and Practice, Prospect Heights : Waveland Press.

Google Scholar

Gossett, Haitte. 1992. “Mins Movement??? A Page Drama”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 19 – 25. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Gray, Elizabeth D. 1992. “Beauty and the Beast: A Parable for Our Time”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 69 – 81. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Hagan, Kay L. 1992. Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Hart, Roderick P. 1990. Modern Rhetorical Criticism,, 2nd ed, Glenview, Ill. : Scott, Foresman/Little Brown.

Google Scholar

Kiley, Dan. 1983. The Peter Pan Syndrome: Men Who Have Never Grown Up, New York : Avon Books.

Google Scholar

Kiley, Dan. 1984. The Wendy Dilemma: When Women Stop Mothering Their Men, New York : Arbor House.

Google Scholar

Lydon, Susan. 1970. “The Politics of Orgasm”. In Sisterhood Is Powerful, Edited by: Morgan, R. 197 – 205. New York : Random House.

Google Scholar

Nimmo, Dan and Combs, J. E. 1990. Mediated Political Realities, New York : Longman Press.

Google Scholar

Ruether, Rosemary R. 1992. “Patriarchy and the Men’s Movement: Part of the Problem or Part of the Solution?”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 13 – 18. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Small, Meredith F. 1992. “What’s love got to do with it?”. Discover, June : 46 – 51.

Google Scholar

Starhawk. 1992. “A Men’s Movement I Can Trust”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagan, K. L. 27 – 37. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Starhawk. 1989. The Spiral Dance: The Rebirth of the Ancient Religion of Great Goddess, San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Steele, Edward and Redding, Charles W. 1962. “The American Value System: Premises for Persuasion”. Western Speech, 26 : 83 – 91.

Google Scholar

Steinem, Gloria. 1992. “Foreword”. In Women Respond to the Men’s Movement: A Feminist Collection, Edited by: Hagen, Kay L. v – ix. San Francisco : HarperCollins.

Google Scholar

Travis, Carol. 1992. The Mismeasure of Women, New York : Simon & Schuster.

Google Scholar

Walkowitz, Judith R. 1992. City of Dreadful Delight: Narratives of Sexual Danger in Late-Victorian London, Chicago : Chicago UP.

Google Scholar

Weitz, Shirley. 1997. Sex Roles: Biological, Psychological, and Social Foundations, New York : Oxford UP.

Google Scholar

Zilbergeld, Bernie. 1978. Male Sexuality, New York : Bantam Books.

Google Scholar

LEAH M. WYMAN is an instructor in the Department of Speech Communication at California State University, Long Beach. GEORGE N. DIONISOPOULOS is a professor in the School of Communication at San Diego State University.

[1] See also Gloria Steinem, “Foreword.”

[2] Hagen describes Bly’s men-only retreats as “mostly white men affirming primal masculinity in expensive workshops” (xii).

[3] Interestingly, although this concept of aggressive male sexuality is often justified through biology, research suggests that it may be, instead, socially constructed and reinforced. Small’s research on bonabo monkeys—which she claims are biologically closer to humans than chimpanzees—illustrates that in these animals sexual expression was never laced with power and aggression. In contrast, sexuality was occasionally used to decrease tension and hostility. As she argues, “sexual behavior ... occurs after aggressive encounters, especially among males ... it’s the male bonabo’s way of shaking hands and letting everyone know that the conflict has ended amicably” (49). She asserts further that when a group of bonabos encounter a food source that may be fought over, the group will often dissipate the tension through sexual activity, hence confirming the situation as friendly instead of adversarial. Research of this type suggests that the human associations of sexuality—particularly male sexuality—with power and aggression may be socially conditioned instead of biologically innate.

[4] As an interesting example of this tendency toward bipolar descriptions, Travis notes a study that examines how parents describe children. It reveals that if the parents have three or more children, they describe each in individual and unique terms. But if the parents only have two, they describe them as opposites—such as one is outgoing, the other shy, one is athletic, the other clumsy, and so on.

[5] Travis also suggests that the idea that women are more intuitively empathetic than men may be based on the fact that women have typically been in positions of less power than men—especially in the workplace. In situations in which power is equal, the gender gap in intuition and empathy dissipates.

[6] This and subsequent references to the screenplay or director’s notes are from Coppola, F. E, and Hart, J. V.’s Bram Stoker’s Dracula: The Film and the Legend.