Luisa Del Giudice

Studies in Italian American Folklore

1. Tears of Blood: The Calabrian Villanella and Immigrant Epiphanies

Small-Group Life and Cultural Reproduction, 1960-1990

Contexts of Villanella Singing

Serenades to Wake a Lover from Her Slumbers

Songs of Disappointment and Despair

The Villanella and Mediterranean Cultural History

Significance of the Villanella

2. The "Archvilla": An Italian Canadian Architectural Archetype

The Dream House: Bridging Recollection and Projection, Reality and Symbol

The House in the Italian Folk Worldview

Ethnic Personalization of Space

The Mental Landscape of the Italian Immigrant: Land and Food

Ethnicity and Upward Mobility: The Archvilla

Inhabiting the New Spaces: Discrepancies

The Secularization of Folk Icons

The Arch as Cultural Archetype

Recalling Rome in the New World

Monumentality on the Domestic Front

Fascism and Romanità: The Myth of Rome

The Arch as a Focus of National Identity

Background Factors of the Little Italy Festival

History of the Little Italy Festival

Food-Related Events and Attractions

4. From the Paese to the Patria: An Italian American Pilgrimage to Rome in 1929]

Stereotypes as Cultural Constructs: A Kaleidoscopic Picture

"Measuring Italianness": The Analysis of Common Sense

The Changing of Stereotypes in Fieldwork

Varieties of Meaning in Stereotypes

Stereotypes of the Past: A Paradox Leading to Success

Wop, Dago, Guinea: The Evocative Power of Stereotypes

Transforming the Stereotype: Change and Continuity

Narration of Success and Successful Narratives

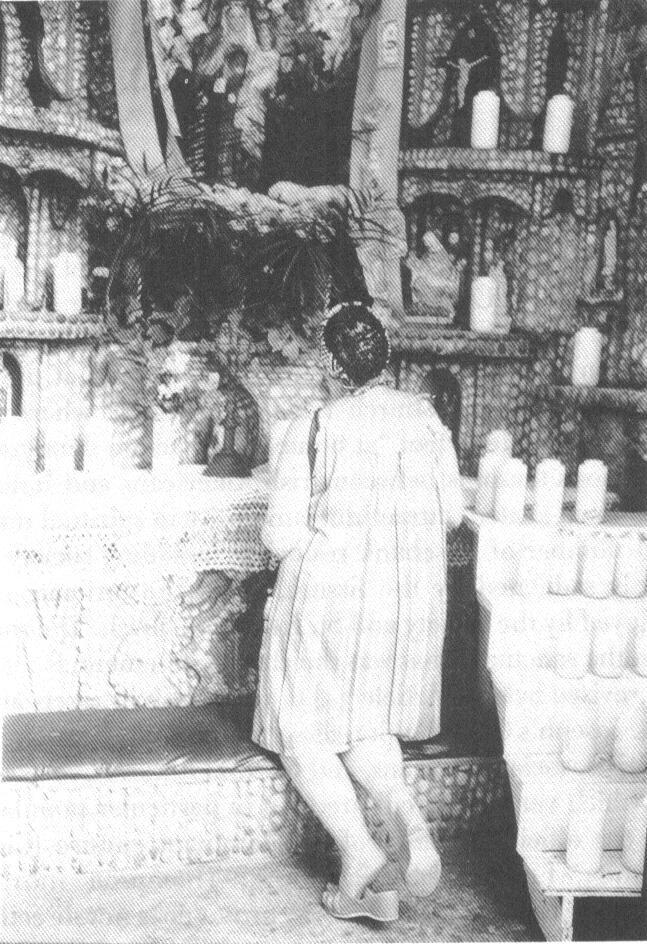

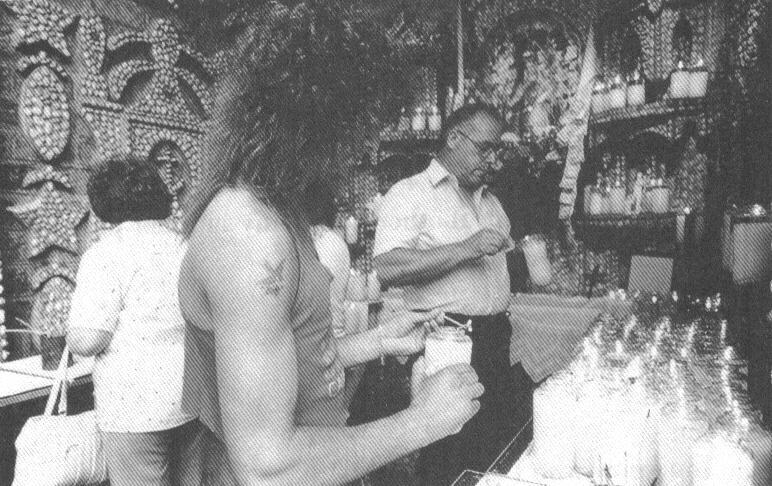

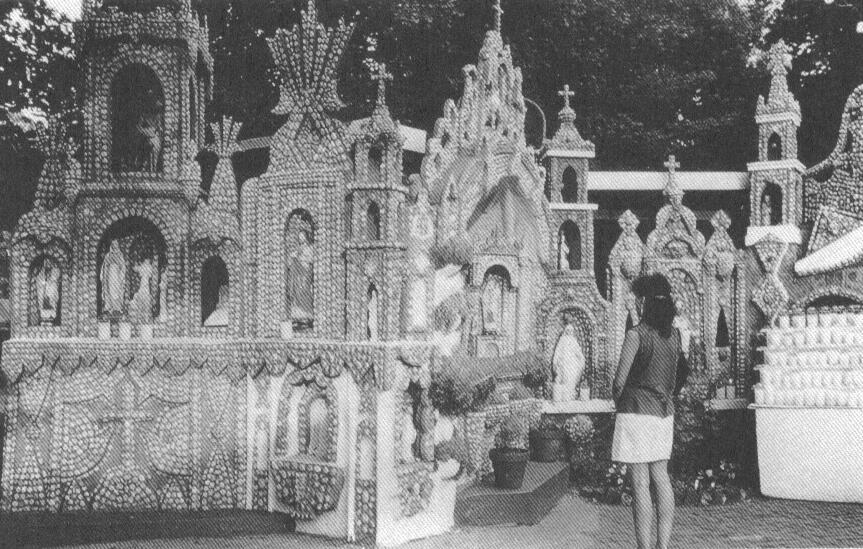

Talking to God at the Rosebank Grotto

Bibliography of Italian American and Italian Canadian Folklore

| Series | Publications of the American Folklore Society |

| Publisher | Utah State University Press |

| ISBN10/ASIN | 0874211719 |

| Print ISBN13 | 9780874211719 |

| Ebook ISBN13 | 9780585098500 |

| Subject | Italian Americans--Social life and customs. |

Front Matter

Title Page

Studies in Italian American Folklore

Edited by

Luisa Del Giudice

Utah State University Press

Logan, Utah

1993]

Publisher Details

1993 Utah State University Press

A Publication of the American Folklore Society, New Series Patrick B. Mullen, General Editor

Cover design by Mary Donahue

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Studies in Italian American folklore / edited by Luisa Del Giudice

p. cm.(Publications of the American Folklore Society. New series)

Includes bibliographical references and index.ISBN 0-87421-167-0 (hardcover: acid-free)ISBN 0-87421-171-9 (paperback: acid-free)

1. Italian AmericansSocial life and customs. I. Del Giudice, Luisa. II. Series: Publications of the American Folklore Society. New Series (Unnumbered)E184.I8s8151993]

973'.0451dc2093-21459]

CIP

Acknowledgments

I wish to acknowledge the help of Moyra Byrne and Alessandro Falassi in the initial phases of this project, especially in the evaluation process of papers submitted for consideration in this volume. I thank Patrick Mullen, Steve Siporin, and Elizabeth Mathias for their reading of, and valuable commentary on, the various essays assembled here. And I am grateful, as always, to my husband, Edward Tuttle, whose many expertises and abiding enthusiasm makes my life as an independent scholar less one of soliloquies than it might otherwise be.

Introduction

Luisa Del Giudice

In commemoration of the five hundredth anniversary of the voyages of Christopher Columbus to America, the Italian section of the American Folklore Society presents this collection of essays on Italian American folklife. This is one of the first efforts to bring together various voices to interpret the folkways of this ethnic group in America.[1] Midst the contrasting fanfare and backlash of the Columbian year, it appeared that some quieter and more thoughtful assessment of the Italian presence in this country was called for, one more in tune with the times. Further, an attempt to focus on an aspect of Italian culture little known and little appreciatedeven by Americans of Italian descent themselvesseemed long overdue.

Sensitivity to issues of cultural diversity has ideally been a practice of folklorists long before it became fashionable. This openness, however, is not just directed toward other groups, but also encompasses the various voices within one's own ethnic affiliation. Italians have known diversity throughout the centuries. The evolution of myriad city states and republics (the most powerful being the Venetian, Florentine, and Papal States) and a long history of foreign occupation (from the medieval Normans and Arabs in the South, to the later Bourbons and the more recent Austrians and French in the North) have each added layers to the ancient cultural substrata of pre-Latin and Latin tribes. These historical legacies have all contributed to a highly diversified social and cultural reality which today we recognize as composed of North, South (dividing at the La Spezia-Rimini line), and Central Italy; regional and linguistic Italies with further dialectical fragmentation within the regions; ethnic minorities (among them, Albanians, Greeks, Slovenes, Germans, and Provençals)many with separatist notions; and finally, the large Italian diaspora populations, most numerous in North and South America, but present on other continents (Australia, Africa) as well. Compound these peculiarly Italian cultural parameters with those that more generally applyclass, gender, religion, generation, and so forthand one begins to capture the complexity of Italy.

While many Italian Americans seem "starstruck," quick to point to illustrious Italian ancestorsMichelangelo, Leonardo, and Columbus himselfas a means, somehow, of "legitimizing" their background, few are as eager to call attention to a heritage more intimately theirs the folk cultural patrimony. With the conspicuous exceptions about whom we have heard so often, Italian immigrants to North America came largely from the more economically depressed areas of the country, possessing archaic features of peasant culture which they carried directly to the New World. The cultural patterns they here forged are both direct imports and creative inventions, wherein old (their regional and national Italian identities) and new (the local and national American realities) dynamically interact.

Although the bold achievement of Columbus in navigating an ocean merits commemorationwhile also recognizing the negative impact of the contacts he initiated on native peoplesit is equally true that each immigrant made a personal and more recent "journey of discovery" into largely unknown territory. Fueled by myths and misconceptions, and a desperate need to flee poverty and social decay, those first Italian immigrants to the New World sought refuge and economic well-being. Many discovered they had come to a physically and humanly hostile environment. Some adapted, eventually made peace, created a new "hybridized" culture, and some fled. Few originally intended to make this land a permanent home, but the majority remained. In the last two decades, interestingly, we are witnessing the phenomenon of reverse migration, as Americans of Italian descent return to Italy.

If Columbus's voyages engender ambiguity today, it is not only those far earlier, Asiatic immigrantstoday's Native Americans-who curse him. To both early and subsequent Italian immigrants, too, Columbus did not figure as an unqualified hero. He was sometimes invoked as the first cause of suffering and alienation for Italian immigrants: "Maledetto Cristoforo Colombo e quando ha scoperto l'America!" ("Damn Christopher Columbus and his discovery of America!") is a phrase I have heard on more than one occasion. Indeed, from the Italian folk perspective, the majority of paesani who debarked on these shores were as much victims of a capitalist, colonial mentality the pawns in global relocations of labour[2] and resourcesas the peoples these new waves of migrants might have displaced. Emigration, from the fin-de-siècle Italian government's perspective, was a means of alleviating domestic woes, a demographic safety valve through which, in addition, might trickle back some harder currency.

Christopher Columbus and immigration are intimately linked in the Italian folk mentality, and at a stretch, he may be seen as the prototype of the wandering Italian. Indeed, Columbus himself was an immigrant ante-litteram, since he settled and married in Spanish Madeira and his offspring were Spanish. He frequently appears in folksongs about immigration, for instance. In one widely known Northern Italian folksong, Columbus is the "discoverer" of a harsh and inhospitable land:

E Ii veniva Cristoforo Colombo,

E ha scoperto 'na parte del mondo,

E navigando sul mare profondo,

Fino all'Anerica, e noi siamo arrivà.

E siam partiti dal porto di Genova,

E siam partiti con grande onore,

Trentasei giorni di macchina a vapore,

Fino all'America, e noi siamo arrivà.

. . . . . . . . . . . . .

E in America noi siamo arrivati.

Non abbiamo trovato nè paglia e nè fieno.

Abbiam dormito sul duro terreno,

Come le bestie abbiamo riposà.

E l'Aanerica l'è lunga e l'è larga;

L'è circondata da monti e colline.

E con l'industria dei nostri italiani,

Abbiam formato paesi e città.[3]

But, more often, he has been blessed for making prosperity in the New World possible for destitute Italian peasants. To the descendants of those immigrants, Columbus became an emblem. Columbus Day, which occurs every October 12, is not so much a celebration of that first journey in 1492 as it is a public acknowledgment of Italian Americans and a self-celebration of their accomplishments and contributions to American society. Indeed, that each ethnic group be accorded a holiday in the national calendar may become a worthy feature of our diverse society. In Canada, Italian immigrants have fixed upon the more northerly navigator, Giovanni Cabotto (John Cabot), to serve a similar emblematic function. Italian immigrants are proud of their contributions to the New World. But most of themthat strata of Italian society upon which, as folklorists, we frequently focusdidn't plant the flag, but rather helped build America in brick and stone.

Is there some irony in the fact that an Italian Canadian is writing this "Columbian" introduction? Ought I to mention that my father could not enter the pearly gates of the America he sought? His navigations landed us a bit farther north, but could as well have landed us farther southall a matter of quotas and the immigration policy of the moment. My personal "voyages of discovery" have been many: as an Italian immigrant born in Italy and raised in Canada; as an Italian Canadian returning to Italy to "discover" Italian cultureofficially in Florence and more intimately in a town just south of Rome, my birthplace; as an Italian and Italian Canadian transplanted to the United States and coming into contact with both the older strata of immigrants and the newest clique of transatlantic Italian commuters. Personally the continental and transatlantic links remain vitalno side of this triangle must be severed for my own mental well-being. And so, I project, the ideal equilibrium for any immigrant might be this cultural pendolarismo between who one was and who one is, as one's cultural identity continuously evolves.

I am not of the nativist school which aspires to study Italian American culture as a self-contained phenomenon; rather its dynamism arises from the historical and geographical dyad (even triad), and that requires a knowledge of the specific local Italian culture from which each form of Italian American culture evolved. Carla Bianco's The Two Rosetos (the one in Puglia, the other in Pennsylvania) offers, I believe, the model which best enables us to fully understand and appreciate the Italian American symbiosis. If we ignore the province of Fog-gia circa 1900, Roseto, Pennsylvania, will necessarily be fraught with mysteries and anomalies. An understanding of Italian regionalism is essential to the study of Italian American folkways.

But consciousness of two worlds is not merely a desideratum for researchers. It is the reason why Italian language acquisition for second- and third-generation Italians is so vital; why return trips of discovery are so important for Italian Americans. No Italian American can fully know himself or herself culturally until these rites of passage have taken place. They contribute richness to a cultural identity far beyond the abilities of a Mean Streets or Good Fellas. Of course, with the passing of timeand grandmothersand the severance of transatlantic ties, the Italian past dims in memory and seems to become less and less relevant. Or so it would appear, were it not for the fact that even third- and fourth-generation Italian Americans still feel the pull.

The reader will note that most of the essays in this book do not ignore Italian folk and national culture but make constant reference to them. These articles demonstrate that a more than superficial understanding of Italian American folkways is impossible without a broad background knowledge of the Italian language, Italian folkways, national and regional cultures and history. But they do not stop at cultural archaeology. Rather, all have been shaped by extensive field-work, where the dynamism of past and present reveals itself in living traditions. Yet, of the many variables which must be taken into consideration in the study of Italian Americans, regionalism appears to be the most significant.

The Calabrian villanella is a sung genre born in the southern Italian region and still alive among Calabrian immigrants in New York. Yet Anna Chairetakis's paper is more than a study of a specific song genre; it is a detailed ethnography of Calabrian Americans in the New York/New Jersey area and touches on traditional gender roles, social organization, foodways, traditional verbal exchanges, and other aspects of folklife. This context provides for an understanding of the vil-lanella, especially in terms of the psychological, symbolic interpretation that the author suggests. Chairetakis writes with conviction, excitement, colour, and a feeling for live performance; her essay is an intensely enjoyed unfolding of social interaction. Her work in the Italian American community has ranged from documentation of this sort, to the production of important musical recordings (listed in the bibliography) and festival organization and advocacy. It is worth noting, too, that the villanella singer De Franco has recently become a National Heritage Fellow.

My study of the “archvilla" in Toronto spans three decades of Italian life and customs in Canada and focuses on the mix of elite, popular, and folk cultures in the little-examined "new" immigration. It, too, is a cross-genre commentary, which draws upon proverbs, customs, and foodways to provide a sense of the evolving social life of Italians in Canada. It shifts continuously between Italy and Canada and among ethnic pride, historical memory, and personal aspirations as these forces shape the interplay between real and mythic space in an architectural form. Ultimately the essay is historical and examines Fascism's use of the myth of Rome and Roman architecture and how these have helped imbue the arch with special meaning for Italian Canadians.

Sabina Magliocco deals with a most important topic in any discussion of Italian American folklifefoodways, in this instance those within the festival context. Because festivals are such a major form of Italian ethnic expression in North America, this essay provides important insights into both foodways and festivals as they converge in Clinton, Indiana's Italian festa. It also explores a little studied northern group of immigrants, the Piedmontese in Indiana, and helps right the imbalance in Italian American studies, which have so often focused on southern Italians (and to a lesser degree on central Italians). This article is firmly grounded in fieldwork, knowledge of Italy, and theory, as Magliocco refers to, among others, Hobsbawm and Ranger and their notion of the "invention of tradition."

Dorothy Noyes's contribution is the most historical in this collection, although she has carried out extensive fieldwork in Philadelphia's Italian community, which resulted in an important exhibit and catalogue (curated and written by Noyes) on Italian American traditions at the Fleisher Art Memorial (Philadelphia Folklore Project) in Philadelphia in 1989. This essay, based on contemporary newspaper accounts, focuses on the "invention" of Italy in and around 1929 by Italian Americans who undertook a "pilgrimage" to Fascist Italy organized by the Philadelphia chapter of the order Sons of Italy. Since Italian American organizations (whether town, regional, religious, social, professional or sports affiliated) are so much a part of Italian life in America, this article sheds important light on how such organizations may mediate and invent ethnic identity. It also reveals the vast distance which often separates these "official" representatives of the Italian community from the community itself, the rhetoric from the reality, the representation of events from the actual events.

Paola Schellenbaum, an Italian contributor, provides the most strongly theoretical essay in this collection, yet it is based on sustained fieldwork in the North Bay area of California. The author, who frames her work in reflexive ethnography, examines cultural stereotypes through a kaleidoscope of shifting perspectives: how Italians from differing regional provenances stereotype each other and Americans; how Americans view Italians; how, as an Italian researcher, she views Italian Americans and Americans. She positions the process in a historical context and focuses on the transformation of meanings and symbols through time as they may be distorted by memory and shaped by collective imagery. Like Magliocco, Schellenbaum gives central importance to the idea that emotional reactions may be strongly coloured by cultural conditioning.

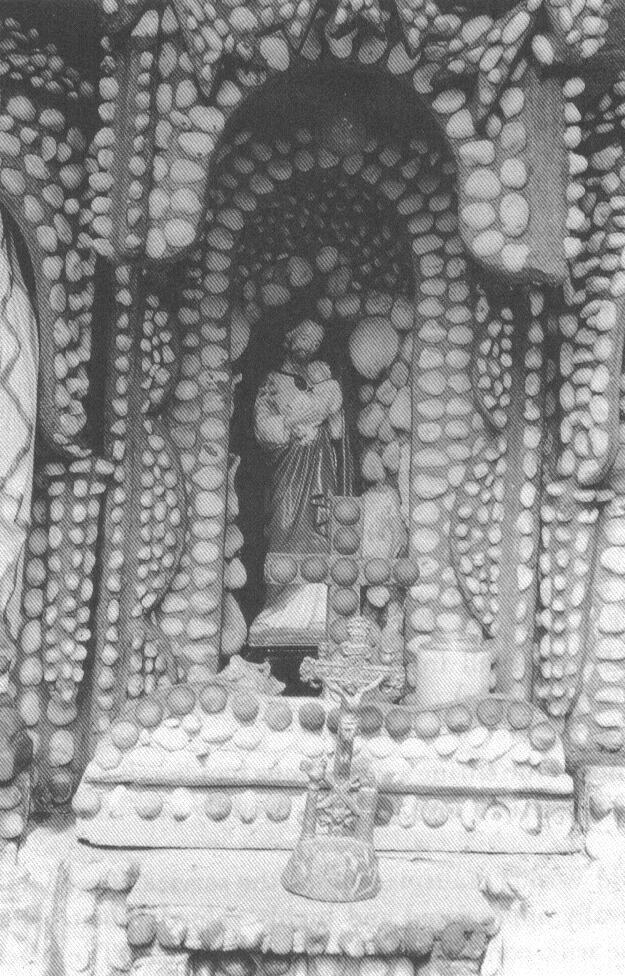

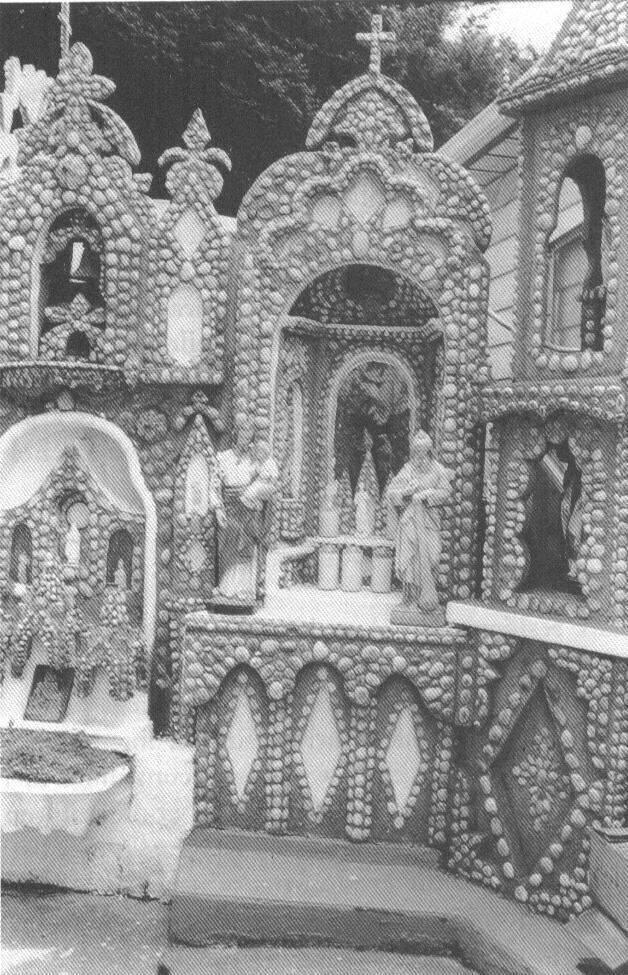

Joseph Sciorra, who has long been interested in sacred space (from backyard shrines and altars to the Giglio procession and festival and, in his essay here, the Our Lady of Mount Carmel grotto in Rosebank, Staten Island), has an ear for diverse and contrasting voices. Sciorra examines the ways in which people's words and actions engender meaning for the grotto. The multivocality emanates from three groups of people: the society members who constructed and currently maintain the site, the faithful who travel from all parts of the New York City metropolitan area to pray at the grotto, and the local clergy. From the whispered and written prayers of the faithful inside the grotto to the priest's diatribes against the society's brand of popular religion, the voices Sciorra captures are many. Further, the discourse around the grotto spans an ocean and centuries. Sciorra recalls the place of caves in popular Mediterranean religions, the conflict between Marian- and Christ-centered Catholicism, the centuries-old conflict between southern Italian peasants and the Roman Catholic clergy, and the current battle for inclusion and diversity in mainstream religions.

These essays span time and space. They focus on both new and old immigrants: from the largely post-World War II community in Toronto, Canada, to the more established Italian Americans of New York and Philadelphia. Geographically they range from large cities such as New York, Toronto, Philadelphia, and San Francisco to smaller communities like Clinton, Indiana, and San José, California. Regionally they deal with Italian American groups of Piedmontese and Calabrian descent, or more generally with the essential northern/southern Italian divisions. And in terms of national culture, the patria is the "mecca" of a pilgrimage fashioned by the "Supreme Venerable," Giovanni Di Silvestro, in 1929; it may also be a more archetypal place evoked through architectural nationalism in the archvilla. Further, the essays collectively address important parts of Italian American folklife: music, architecture, foodways, associations, religion, and ethnic representation and stereotyping.

This brief introduction should orient the reader to the six essays assembled here. Finally, in the interest of disseminating the work of previous scholars on the folklore of Italian Americans and Canadians, and in the hope of reviving research efforts in this field, I have appended a bibliography and index of Italian American and Canadian folklore to this collection.

And there came Christopher Columbus,

And he discovered a part of the world,

And sailing on the deep sea,

We arrived in America.

We departed from the port of Genova,

And we departed with great honour.

Thirty-six days on a steamship,

We arrived in America.

And in America we arrived.

We found neither straw nor hay.

We slept on the hard ground;

Like the animals we slept.

And America is long and vast;

It is surrounded by mountains and hills.

And by the hard work of our Italians,

We built towns and cities.

For an edited version of this "emigration song," compare Nuovo Canzoniere Italiano, "Trenta giorni di nave a vapore," on Roberto Leydi and Franco Crivelli, eds., Bella Ciao, Dischi del Sole, 1974.

1. Tears of Blood: The Calabrian Villanella and Immigrant Epiphanies

Anna L. Chairetakis

Introduction

"We were clearing the fields for a landowner in the Sila,"[4] recalls Raffaela De Franco of her adolescence during the post-World War II years. "We were all women, and we were singing. They always wanted me along because, young as I was, my voice was a trumpet, and I could both sing and throw the iettu. Suddenly, a man appeared with a large machine. It was a tape recorder, but at that time, none of us had ever seen one. We believed he was using an enchantment to steal our souls through our voices, and some of us talked of killing him on the spot."

Twenty-five years later, on the evening of February 23, 1975, I carried a tape recorder into the basement of Santa Rosalia Church in Brooklyn, New York, and found Mrs. De Franco and a group of her paesani (fellow townspeople) singing the villanella. At that moment I felt the way Heinrich Schliemann must have when he discovered Troy. I had been searching for Italian musicians to perform at the Smithsonian's Festival of American Folklife in Washington, D.C., that year and had thus far found few Italian Americans who knew or would claim their folk music. At last I had received a promising invitation from the sacristan of St. Rosalia's to hear "some of those little things we do in our dialect." One of these "little things" proved to be a chorus lining out drone harmonies which would have been pleasing to the Byzantines of southern Italy ten centuries ago.

The Calabrian villanella is a polyphonic song-poem elaborating on the ottava, or eight-line, hendecasyllabic, lyric verse form characteristic of south-central Italy.[5] It is native to Acri and nearby communes of the province of Cosenza in the northern Calabrian interior and belongs to an extensive tradition of similar unaccompanied choral singing which until recently flourished in the upland tangle of hilltop towns and villages that run the length of the south-central Apennines.[6] In Acri, as among the immigrants to the United States from that commune, the villanella exists in at least three melodic and structural variants. I estimate that the Acretanu repertoire of vil-lanella texts (excluding variants and historical texts now no longer current) may well run into the hundreds; I can only present a sample here.

The villanella is a genuine antique of a type of European polyphony employing two to three parts with a double drone. In spite of its interest as both a musical and poetic form, however, it has received little scholarly attention. Because it is difficult to master, is stylistically unorthodox by the canons of Western polyphony, and lacks the cheerful naïveté beloved of revivalists and composers in the folk vein, it has never left the oral tradition. There, however, it holds an honored place.

The following analysis, which links the social contexts, musical style, and poetics of the villanella, suggests that the genre as performance is a statement about the small group life and informal coalitions characteristic of Apennine society south of Rome. As such, it simultaneously announces women's prominent role within such groups and stresses the bonding of couples, and with it the ethos of patriarchal familism which infuses mountain social organization. Among Acretanu immigrants of the 1960s and 1970s, shifts in social relationships and economic roles have expanded the feminine domain and attenuated the ties connecting kin and neighborly groups. However, the villanella remains relevant as an embodiment of Cala-brian aesthetics and psychosocial dynamics. Villanella singing and reciting are acts of remembrance and meditation on both individual experience and collective identity which are important in the set of Calabrian practices and cultural icons that immigrants have integrated into their American setting.

The Acretani

The Brooklyn singers interrupted themselves with shouts of "Eccola! È arrivata!" ("Here she is, she made it!"). Greeting me with open arms and affectionate embraces were about twenty people of all ages, most of them related. The only props in the otherwise empty basement were some chairs arranged in a semicircle. To the side, a long table was laden with food fixed at home and packed in foil: baked pasta, rispelli (twists of fried dough), squagliatielle (circlets of boiled, then glazed, dough, flavored with anise or pepper), olives, pickled eggplants and hot peppers, home-cured hot and mild salami, homemade ricotta, imported mountain cheese, bread, and winea dark, Homeric red and an effervescent white, made in Brooklyn cellars from California grapes.

A small, moon-faced man, red with suppressed excitement, played the four-base organetto (button accordion) for dancing. He had been driven over from New Jersey for the occasion. A statuesque, black-haired woman of sixty accompanied him on the tambourine, with her brother, a grizzled, smiling man of flay, a former muleteer, who played the castanets. Everyone dancedpolkas, mazurkas, waltzes, and variants of the Calabrian tarantella. Those who sang the villanella and for the tarantella were all, with the exception of one youth who was learning, over forty.

This was, at the time, a regular Saturday night gathering of the Ac-retani. They had immigrated between the late 1950s and early 1970s from the large commune of Acri (thirteen hundred hectares), situated midway between the Ionian and Tyrrhenian seas in the Sila Greca and had attached themselves to preexisting Acretanu enclaves in Benson-hurst, Brooklyn; Belleville, Nutley, and Lyndhurst, New Jersey; and Westerly, Rhode Island. They worked in factories, as longshoremen, or ran small family businesses. Two distinct groups were represented among them: those from the paese, a bustling town of about eighteen thousand, and those from the hamlet of Serricella and other rural districts within the territory of the commune.

The first group, settled for the most part in Brooklyn, had been owner-shepherds, blacksmiths, shoemakers, carters; muleteers, shopkeepers, and silk makersbelonging, in short, to the subclass of artisans who also farmed. They remembered Acri as a jolly place. Calabria was their homeland, America a place of temporary exile to be tolerated but not loveda place to make money to take back to Calabria, where the landscape was inspiring, the mountain climate healthful, the food genuine, and social life full of pleasures. Even with grown children starting families of their own in America, the older members of this group were beginning to spend several months out of each year in Calabria as they neared retirement. Some were planning to repatriate altogether. Because of their Calabrian orientation and because they had little need of it in their daily lives, most of those over thirty had not learned English.

Those from the rural districts, on the other hand, had known a harder life, having worked as marginal sharecroppers, field hands, hired shepherds, and day laborers. Even those few who, as tenant farmers and small proprietors, had eaten well, worn shoes, and attended elementary school as children felt the isolation and abandonment by "civilized" society experienced by all the country people. For until the 1960s, the rural hamlets had lacked paved roads, electricity, water, medical care, and other amenities of the twentieth centuryall but the most rudimentary stores and schools. Consequently, many in this group felt that Italy had wronged and excluded them so that they could not live as "cristiani" (human beings). Although Calabria held powerful associations, it was a place to visit occasionally, but not to return to permanently. Their loyalty was to America, which had treated them better. While most of their time was spent among speakers of Calabrian, many of the adult members of this group had learned English fairly quickly.

The women of both groups had worked on their own farms and as estate laborers in Calabria. Some of those from artisan families had been silk makers in a small way. In the United States, these women continued in their breadwinning roles, largely in factories.

Notwithstanding their differing perceptions of and attitudes toward Italy and America, both rural and urban Acretanu immigrants had integrated a series of Calabrian practices and traditions into their American settings, creating, as have other immigrants and minorities, a vital, intense, and distinctive cultural life. In general, such a strategy has not produced conflicts for Acretani; on the contrary, it has eased the immigrant adaptive process and has helped to launch the younger generation into American life within parameters that are acceptable and pleasing to both young and old.[7]

Small-Group Life and Cultural Reproduction, 1960-1990

The Acretani have reproduced in America a modified version of the southern Italian modes of patriarchal household formation and economy and of social interaction. This lifestyle is characterized by a loose corporate management, by both parents and eventually grown children, of the resources and labor of the entire household and is aimed toward marrying and endowing all of the children, who then maintain ongoing interests in and dependencies upon parental and fraternal households. In such a field of intrafamilial and interhousehold relationships, the mother-daughter bond is perhaps the strongest. It expands over time to include daughters' husbands and children and to ramify among maternal siblings and their children.

Paralleling and sustaining these forms of social interaction are three orders of behavior, consisting of the flow and patterning of social life, food making and distribution, and expressive culture, particularly the verbal and musical arts. These are the foundations of adult small-group life, which is a primary locus of the creativity and cultural renewal of the community.

The small group is composed of kin cummari and cumpari [Italian comari and compari], persons considered kin through the institution of godparenthoodneighbors and former neighbors, people who grew up together in Calabria, and occasionally, hometown acquaintances brought closer together in the United States. Typically, siblings and their spouses form a stable core to which other couples adhere, but very often the small group may include single women isolated by widowhood, marital separation, or other circumstances. Members carefully weigh the degree of reciprocity in the frequency and length of visits; the exchange of information, food, favors and gifts between them; and inclusion in celebrations and work bees. In keeping with southern Italian social mores, the small group may include an individual of higher status who acts as honorary patron.

Such informal groupings are loosely connected in a web of kinship, friendship, secondhand friendship, and gossip. They are brought together periodically in the life-cycle celebrations shared by all, either through direct participation or through knowledge and discussion. Impinging on this relatively egalitarian network are several overarch-ing and interpenetrating principles and structures. First is the still-imminent shadow of the oppressive two-class system that prevailed in southern Italy until about 1955, within whose bottom half most of the immigrants were ranked. Then there are the formal institutions of the immigrant community-church, ethnic social club, fraternal and political organizations, and festivalsthrough which a variety of values and aspirations are articulated. Finally, permeating family life, household organization, and public behavior is the hierarchy of gender, with men occupying a formally dominant position in the sexual division of roles, and a separation of male/public and female/private domains. As a general operating principal, southern Italian patriarchy mirrors the old class system, in which the poor, like women, were invisible. However, complementarity appears to supersede gender hierarchy in small-group relations; adult married women in fact play the central, leading roles in group organization and activity. In my observation, the Acretanu pattern is generally representative of mountain village society in Calabria, Campania, Molise, and Abruzzi.

To the greatest extent possible in an American urban or exurban setting, the Acretani follow the cycles of the agricultural calendar in Calabria. Both men and women put most of their spare time into growing, preparing, distributing, and consuming traditional foods. It is a process which shapes and nourishes, both corporeally and spiritually, most other aspects of social life. Indeed, as they engage in these activities, it would seem that the Calabrians are actually growing their culture.

In the spring, gardens are sown with tomatoes, basil, zucchini, eggplant, hot and sweet peppers, parsley, salad greens, and other vegetables. These are eaten fresh as they ripen and also preserved. Pickling and preserving begins in late summer: pressed eggplant or zucchini with hot pepper and garlic in oil or vinegar; pimentos; hot peppers of all kinds; sun-dried tomatoes; wild mushrooms and berries gathered by those who live near woodlands. Late in August, kin and neighbors collaborate in canning hundreds of jars of homegrown tomatoes, supplemented by ones from farmers' markets. September is for winemak-ing with grapes grown on backyard vines and arbors and purchased from California wholesalers. In November, green olives are bought, smashed, and cured with garlic and salt. In January, the men kill pigs or buy them fresh killed, and the women cure salami and hams which hang from the rafters of their cool, well-ordered cellars, over casks of wine. Every fifteen days, as in Italy, housewives do their baking: in addition to bread, they often make squagliatielle, rispelli, taralli (baked rings, flavored with anise or pepper), and varieties of pasta for company and holidays. Men make ricotta and cheese and also procure prized shepherds' cheeses from Acri, and at Christmas and Easter they put rabbit or goat on the table.

Many of the tasks of gardening and processing are divided in culturally prescribed ways between men and women; some are shared. Generally, the male contribution is periodic, whereas women's involvement is ongoing and constant. The same applies to distribution. Women continually circulate the foods through the household and extended family and beyond. However, it is frequently a male prerogative to select and bestow special gifts of food, particularly the wine and prized cured meats and Italian handmade cheeses. Both men and women are strongly committed to the domestic food complex.

The home economy is motivated as much by social and psychological needs and gratifications as by values of thrift and serf-sufficiency. It gives a household social currency in the community of immigrants. It nourishes the family psyche, particularly that of the main breadwinner. Giuseppe De Caro of Westerly (aged thirty) put it this way: "When I get home from the plant at night, the first thing I do is go to the cellar, have one or two glasses of wine, and I just sit there. Then I go upstairs to my wife and children, and I feel great." By keeping a Calabrian homea particularly difficult achievement in the immigrant setting, where most working-class Italian women hold full-time jobs a woman constructs a central position in her family and in small-group life.

Further, food is inscribed with gender and sexual symbolism, which the Calabrians make explicit during conviviality. Salami and circles of bread are metaphors for male and female sexual parts. Served together, they present the image of imminent consummation; wine and hot pepper are the agents that ignite and unleash this force. Eaten together, round breads and “soupy" (suppressata [Italian soppressata] or salami) are believed to give strength and, implicitly, to make men potent and women fertile. In other words, consuming such foods becomes an act of contemplating and ingesting sexual potency and fecundity, as well as of renewing these states. In the immigrant community, not only the fertility and regeneration of the family, but that of the cultural community, are sanctioned in the commensal setting. Eating in this context becomes an act that reinforces being Calabrian and regenerates a common Calabrian identity at its very source.

Contexts of Villanella Singing

A trinity of sociality, food, and artful verbal play constitutes the setting in which the villanella is performed by adult immigrants from Acri. As company drops by, wine and preserved foods are brought out from their underground sanctum, complemented by homemade breads, store-bought cakes, and Italian and American coffee. In Westerly, on the night of Easter Saturday, round, braided, egg-studded breads (culluria), "soupy" and wine are offered to Easter carolers playing the chi-tarra battente[8] and singing their praises and good wishes to each household on their rounds. Such foods act both on the body chemistry and on the perceptions, associations, and behavior of those present. When the company is congenial (quannu c'è na cumpagnia bona), they inspire an exchange of witticisms, rhymed when the participants are at their best. Here the paramount theme of coupling is suggested in a stream of allusions, jokes, and riddles. On appropriate occasionsan informal party, a holiday gathering, an impromptu visit from a musician or good singerthis can lead to dancing and villanella singing. Singing sessions are often informally planned"Ven-immu sta sira e facciamu na canteata" ("Let's come over tonight and sing"), someone will suggest.[9] When people know there's going to be singing, even when nothing has been said about it, the verbal play becomes a rehearsal, a warming-up process, a catalyst for the deep plunge into song.

The Italian contexts of villanella singing were far more numerous and varied, being functionally connected to work and to specific social events such as serenading, as well as to informal occasions such as those used by immigrants. Villanelle accompanied female group labor of many kinds: collecting firewood in the upland forests; transporting heavy loads of wood, water, and laundry, balanced on the head, over rough country lanes; and working on the great fruit, olive, and wheat plantations of the plains, where gangs of women hired out by the season and lived in barracks. Villanelle animated the backbreaking labor of harvesting and the neighborly conviviality of corn huskings, both organized through informal cooperation and labor exchange between friends and relations. Insulting verses were sung by women to warn, ridicule, or punish an obstreperous or promiscuous neighbor, or by men to destroy the heart and reputation of a rejected lover. Men and women sang villanelle together in night serenades, calling up verses of soul-piercing tenderness and desire designed to melt a girl's heart and declare to her family and the neighborhood that she was being courted and so out of bounds to other suitors. The sexes sang together at intense, wine-drenched, nightlong parties around the fire in winter months, when work was scarce and agriculture dormant. Or in summer, "We'd sing and frolic till dawn, and then go straight to the fields."[10]

Style, Structure and Variants

Two can sing the villanella, as Raffaela De Franco and her sister did during a rare and emotional reunion. While four or five singers make up the usual chorus, Bambina and Angelo Luzzi recall singing ten to fifteen strong. What majestic, mournful, and thrilling music they must have made on those dark winter hilltops! Not too distant, perhaps, from the "wolf-calling" choruses who, by their concerted howling in the forests, induced wolves to answer and betray their whereabouts. Indeed, one of the probable functions of villanella singing, with its powerful, far-reaching dynamics, was to locate female work parties. The sound carries farthest at the point in the singing when "beating" is intense and the high drone voice enters the chorus.

The villanella chorus may be mixed in sex, but to judge from its many female, work-related contexts and from the importance of the high drone part, the genre is basically feminine. The high drone (called lu iettu, or "the throw," in Serricella, and lo sguillo, "the peal," or caiauto in Acri) is in fact a part specifically designed for women, and it is generally agreed that the chorus sounds best when women are singing. Either sex, or both in alternation, may lead the singing. Leadership is informal, depending upon the skill, vocal qualities, and memory for texts of those present.

Singers stand in a closed circle, leaning against one another or with their arms around one another's shoulders if they are related. An unrelated woman will stand free or arm in arm with another woman. The singers' faces are serious, and their eyes are cast upward or gaze abstractedly into the center of the singing circle. As he delivers his lines, a male lead singer will rock his torso and throw his body into a conventionalized posture suggesting a cringe, twisting his head up and sideways away from the group with his eyes closed and his face in a grimace, like one in pain. Women are more sedate, but also rock and cringe while singing. Positioned thus, they sing into one another's faces, producing a vibrating effect on the sound waves called beating, a device used in vocal polyphony throughout southeast Europe.

The manner in which vocal unity and harmony are created out of monophony/heterophony is the outstanding feature of villanella singing in all local variants of the genre, and indeed of mountain polyphony throughout southern Italy. Each line or couplet is begun by a leader. The leader is joined by, or drowned in, a chorus at the peak of the melody and the poetic utterance, which the whole group then reiterates with variations in both melody and text. The high-pitched, strident voice of the iettu of Calabrian polyphony climactically overrides and ornaments the final line of each couplet. In effect, a monophonic situation gives way to heterophony, in which other voices weave together subtle variants of the melody in loose unison. These distinct voices then merge to create the prolonged, bagpipelike drone chords that are a signature of every phrase ending.

In this way, unity is almost painstakingly constructed out of a concert of in dependent voices, sustained for a few breathtaking moments, then broken, to be recreated in succeeding lines of the song. This is a precise musical statement of the coalition dynamic, and more exactly of the close, yet informal, evanescent nature of small groups, prevalent in southern Italian social life and important as well in Italian American communities. This premise is supported by the manner in which singers consult with one another between verses, prompt the lead singer, argue over which version of the next verse to sing, or compose new verses.[11]

Applied to several examples of the villanella and closely related genres, the Cantometric method of cross-cultural analysis of song performance produces a stylistic profile which is distinctive from, though related to, the predominant urban Mediterranean style.[12] Alternating leaders overlap with a chorus singing unaccompanied polyphony in the highly individualized manner of group performance in the Mediterranean region. Long phrases, free meter, slow tempo, and liberal use of rubato accentuate and dramatize texts, although enunciation is rather slurred, with about 50 percent repetition. Typically found are four- and seven-phrase strophes with melismatic, descending phrases, drone harmonies, loud dynamics, and forceful accent, sung by narrow, raspy, nasal voices.

These features distinguish this Calabrian mountain genre from the "high lonesome" solo tradition of Naples, Sicily and the southern littoral (see Lomax 1955-56 and 1976; Carpitella 1991). From as nearby as the Cosentine coast, one finds accompanied choruses, whose four-phrase strophic tunes, short phrases, diatonism, lack of ornament, and moderate tempo give them a modern Western European flavor. On the other hand, comparison of villanella performances with examples from the southern Appennines, Sardinia and southeastern Europe yields similarities suggestive of common roots in an older tradition of Mediterranean singing that survived in isolated pockets of Sardinia, Corsica, the Balearics, and Appennine Italy-areas never absorbed (or incompletely so) by the centralized, imperial culture of the Graeco-Roman, Arab, and Spanish worlds.[13]

Three melodic and structural variants of the villanella have been reported to methe villanella and lassa piglia of Acri, and the villanella of Serricella. Others, from rural hamlets like Serricella, no doubt existed. In each of the variants, two lines of poetry from a total of eight are elaborated, when sung, into a verse of four phrases plus repetition and recapitulation. The following breakdown of a single verse (two lines of poetry) of the "Villanella di Acri" shows how this variant is performed.

| VILLANELLA DI ACRI | E saputo ca all'America vu jire, ji lu diluvio pe ttia se vo voteare! (I've heard you're leaving for America, And may the deluge rain down upon you!) |

| First Leader: | E saputo ca all'America vu jire, ji lu diluvio pe ttia se |

| Chorus: | vo voteare-e-e |

| First Leader: | Aié se vo voteare |

| Drone: | e-e-e |

| Chorus and Drone: | Oi pe ttia se vo voteare-e-e! |

| [Recapitulation:] | |

| Second Leader: | E cca vu jiri e lu diluvio pe ttia se |

| Chorus: | va voteare-e-e |

| Second Leader: | E se d'e voteare |

| Chorus and Drone: |

Oié pe mmia se vo voteare-e-e![14] The first leader throws back his/her head and delivers the first couplet (canta), and the chorus (l'accuordo) comes in unevenly over the end of the send line in ragged two- or three-part harmony, which unifies in a sustained drone note at the end of the line. The first leader then repeats the last phrase of the couplet, with the high drone (iettu) coming in over the final droned vowel of the chorus. Chorus and iettu repeat the last phrase a second time. A second leader then returns or throws back (revota) the couplet in the Same manner, recapitulating or echoing, with the chorus and drone, different sections of the lines. Each phrase is long, lasting from six to sixteen seconds, and an entire couplet/verse takes from forty-five seconds to a minute to performthree times as long as the strophe in most European folksongs. |

Like the "Villanella di Acri," the lassa piglia was performed only in the urban center (Acri paese) by the artisan group, but it has a more complex structure than the villanella. Three leaders alternate within a single strophe, and the chorus elaborates the couplet in such a way that it is gradually broken down to the e-e-e-a-e coda, the favored vowel combination in the dialect of the paese. There does not appear to be a high drone part in the lassa piglia. "La lassa piglia è stata fatta prima della villanella," Annunziato Chimento told me. “Una piglia, un'atra revota, e un'atra la finisce, e poi c'è quella che ietta." ("The lassa piglia originated before the villanella. One person takes up the song, another returns it, and a third finishes it; then there's the one who 'throws' the drone voice.")[15] A single verse (two lines of poetry out of a total of four) is sung thus:

LASSA PIGLIA DI ACRI

| Eh! Intrá ssi fuossi e dintra ssi valleate, ogni damiente mie d'introné si sente! (Eh! In these chasms and in these valleys, My every lament like thunder echoes!) | |

| First Leader: | Eh!... Intrá ssi fuossi, e dintrá ssi valleate-e-e-e-a-a! |

| Second Leader: | Eh-e-e, dintrá ssi valleati, o-ogni damiente mie-e-e-e-e-a-e |

| Third Leader: | e d'introné si |

| Chorus: | sente-e-he-e, d'introné si sente-e-e! E-he-e-a, e-he-e-a![16] |

Villanelle were sung in towns surrounding Acri as well. Acretani view their own singing as very close to that of the ethnic Albanians (Gheghi, as they are known locally, from the Albanian phrase ghe, or "hey, you") from nearby settlements such as San Demetrio, Vac-carizzo, or Cavallerizzo. During seasonal agricultural labor, women from both ethnic communities worked and sang together, appreciating one another's proficiency in similar drone harmony traditions and enjoying novel differences in styles and texts. Female-dominated polyphonic songs, similar in function and performance style and no less striking, but not as long or structurally complex as the villanella, were sung in the uplands throughout south-central Calabria.[17]

Poetics of the Villanella

The French villanelle, which enjoyed great popularity as a verse form in sixteenth-century literary composition, apparently derived from Italian folksong (Preminger 1986; Sadie 1980).[18] In the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, all regions of Italy had their villanelle (Calcaterra 1926). In Naples, however, "[the genre] achieved an artistic beauty all its own, and became known as Neapolitan" (Santoli 1968). Judging from the relative complexity of its sixteenth-century literary form and the modern Calabrian type, the villanella probably developed as an urban artisan as well as a peasant genre, as it appears to have done in Cosenza. In Calabria, it is likely that the term itself is of cultivated or literary origin and may have filtered in through the French presence in southern Italy. Acretanu (artisan) informants told me that the vil-lanella texts were written "over a hundred years ago, before our time, by a poet named Virginio" (whom I understood to mean Virgil). Vir-ginio, they said, wrote many songs which were lost in their written form, but passed down orally to their generation.[19] The contrived artfulness and arch tone of some of the texts I collected does suggest literary derivation or inspiration in a few instancesa not unlikely possibility, given the great influence of Provencal and classical traditions in Italy, as well as the presence of vigorous schools of literary composition in Calabria. Certainly the poetry often has a classical literary cast, particularly in its balance between one contrasting "voice” or argument and another, its persuasive tenor, and its artful use of conceits. At the same time, it is highly original.

Acretanu informants report that villanelle were frequently composed on the spot, although the songs told to me were not attributed to any one individual. It is my impression that authorship may be of slight consequence in the Calabrian context and recedes quickly into obscurity. As far as I know, villanelle are not now composed by immigrant Acretani. In both collecting and performance contexts, women are the primary, though not the only, sources of texts, and some have extensive repertoires of more than fifty texts.

When asked to repeat a villanella text, an Acretanu will recite it as an ottava (eight-line lyric poem in hendecasyllabic meter), which is how the songs have been transcribed by older collectors:[20]

Eh! Cchiù si bella e cchiù ci puort' affettu,

e pu mi muostri tanto madu coru!

Eh! De dacrimi de sangue ci di iettu,

lu vientu mi disperde li parodi.

Oije ma ssu pettuzzu tua forrá di vitro,

che lu da intra comparissi fori!

Ca i pub vedere se ci puorta bene,

o puramente si t'amó de core)[21]

(Eh! The more beautiful you grow, the more I love you,

And then you show me such a cruel heart.

Eh! I shed tears of blood,

And the wind scatters my words.

Oh, if only your little breast were made of glass,

So what is inside could show forth,

And I could see if you cared for me,

And if I loved you from the heart.)

However, De Simone (1973) finds for Campanian song, as we do for Calabrian, that in performance the hendecasyllabic line and the eight-line verse are broken down in many different ways, both metrically and syllabically. In the "Villanella di Serricella," a single couplet is broken down as follows:

| VILLANELLA DI SERRICELLA |

Eh! Cchiù si bella e cchiù ci puort'affettu, e pu mi muostri tanto madu coru! |

| First Leader, male: | Eh! Cchiù si bella e cchiù ci puort'affettu, | [A] |

| epu mi muostri | [B] | |

| Leader and Chorus: | tantu madu corn! | |

| Second Leader, female: | Oi madu | [C] |

| Leader and Chorus: | coru [prolongation of final vowel] | |

| Leader, Chorus and Drone: | oijé tantu madu core! [prolongation] |

Line C is broken down into three parts, but sung as one musical phrase, so that the sung verse structure of the recited (or written) couplet is ABC (in Cantometric terms, simple strophe with variation).

This fact has convinced De Simone that these songs were not derived from the cultivated verse form, which is what earlier collectors assumed, and he notes that no attempt has been made, even with regard to the Neapolitan villanella, to relate present folk versions to older texts. In his view, while interesting from historical and philological perspectives, the value of classifying these popular song-poems into villanelle, motets, strambotti, etc., is small, since the poetic form is often only one component of the whole, which involves repetition and variation, music (often polyphony), gesture and even dance (De Simone 1973).

In the past, villanelle were composed on a variety of themes of local interest, particularly the exploits of bandits and other subjects of political and social concern (see Capalbo 1985: 137 and passim). Some contemporary informants remember these, but in keeping with late-twentieth-century trends in popular culture, the repertory now performed is almost exclusively of a personal, romantic nature. Social themes, such as immigration, poverty, and gender issues, are secondary or implicit.

In the youths of the singers, not long past, the villanella was the voice of courtship and lovemaking in their many aspects, of interpersonal communication of feeling, desire, and intention in a world where other channels were closed and open flirtation and dalliance out of the question. Looking at a modern collection of the texts, one sees that they fall into a natural thematic progression, like the poetry of Catullus, as follows:

Serenades to Wake a Lover from Her Slumbers

O padumella che tu sempri duormi,

risvigliati nu poco e penza a mmia.

farfalla che tu sempri duormi,

svegliati un poco e penza il tuo caro.

Ca lu suonne ti guasta ssi uocchi bielli,

ti guasta lu tuo viso quannu duormi.

Ca il sole si ristrugge i tuoi occhi,

e ristrugge il tuo viso quando dormi.[22]

(O little dove, sweetly sleeping,

Awake, and think of me!

O butterfly, deeply sleeping,

Wake up, and think of your sweetheart.

For Sleep will ruin those beautiful eyes,

Will spoil your face in slumber.

For the sun will destroy your eyes,

Will destroy your face in sleep.)

Songs Praising a Lover

A chissu duoco c'è comparso na stilla,

meracudo di Dio, quant'era bella!

Unn'era ranne, e manco pettirilla,

era giusto di misura e graziusella.

Tiene d' occhiuzzi de davero serpa,

e li capelluzzi della sita torta!

Puzzicchio d'oro e manuzza gentido,

e le jídita ca ci capi l'annello.[23]

(In this neighborhood a star has appeared:

Miracle of God, how lovely she is!

She isn't big, nor is she tiny;

She's a perfect size, and full of grace.

With the sweet eyes of a fascinator,

And hair of twisted silk.

A golden bracelet and soft little hands,

And fingers made for a ring.)

Songs of Desire, Avowal and Intention

U jire menne vuoglio nfuntanella

dove vanno le donne a se lavare.

E scegliere me la vuoglio la cchiù bella,

a nu padazzo me la vuoglio portare.

Chi genti ca mi a vidano tanta bella,

"Dove l'ha fatta ssa cacciariata?"

"L'aiu fattu allu buoscu di Favella,

dove vanno i cacciatori a cacciare."[24]

(I wish to go to the fountain

Where the women go to wash themselves.

I want to choose the most beautiful,

And to a palace carry her away.

And those who would see my prize would say,

"Where did you bag your game?"

"I made her in the forest of Favella,

Where the sportsmen ride to hunt.")

Songs of Disappointment and Despair

Chi de coro che chiange e chi damente,

lassa chiangire a miu povera amante.

Ca chi perde d'amici e chi parenti,

ho cchih doloru che perdo un amante.

Ca chiddu perde mortu non è nente,

se stui l'uocchi e sa queta lu chianto.

Chinu perde bivo è fuoco arzendo,

che iere e momente passa davanti.[25]

(Whomever has known true sorrow and lamentation,

Leave my poor love alone to mourn.

Whomever has been bereft of friends and relations,

Suffers more, losing a lover.

For one who loses the dead will recover;

He will dry his eyes and still his weeping.

But for one who loses the living, it's a burning fire,

And every moment is yesterday.)

Songs of Departure

Strada appassiunata e mo te lascio,

piancendo mene vado la mia via.

Cento miglie de ttia vaio luntano,

e cento funtane fanne l'occhi mie.[26]

(Road of passion, now I leave you;

Weeping, I'm going on my way.

A hundred miles lie between us,

And a hundred fountains spring from my eyes.)

Songs of Scorn

These songs, known as dispetti, are a class unto themselves. They were intended by cast-off lovers to inflict humiliation and even permanent ruin on the objects of their desire.

Facci e cucuzzielle incelenata!

Tu va dicienno ca no m'ha vudutu.

Allu bicchiero tua c'aiu iu bivutu,

allu lietto cu ttia ci signu statu.

Allo tavodo ma ci signu stata

c'aiu fattu tille ch'è vodutu.

Ssi quattro crosche che ci su rimaste,

dónalle a ssu maiale ch'è venuto.[27]

(Stupid zucchini face!

You go around saying you didn't want me.

I have drunk from your glass,

I have lain in your bed,

I have sat at your table

I've done with you what I wanted.

These four husks that are left over,

Give them to that pig who comes to you now!)

The only songs thematically and functionally unrelated to love and lovemaking are songs warning troublesome neighbors, composed and sung by women. This one comes from Teresa Francese (Nutley, N.J., November 1977).

A sse contuorne c'è na mala spina

vucca d'anvierne se potisse chiamare!

Ad ogni focodare e si avvicina,

ad ogne menestra va mettienne u sade!

Fatte l'affare tua, mala vicina!

Tu de d'affatti mia nun hai c'affare!

Ca s'iu passu da luoco qualche mattina,

e quattro cane te fazzo pigghiare!

Una si chiama scippe, e n'autra spurpa;

a poco poco te devo cacciare.

(There's a big pain in the ass in the neighborhood

Mouth of Hell could be her name.

She creeps up to every hearth,

And throws her salt in every broth!

Mind your own business, bad neighbor!

Keep your nose out of my affairs!

For if I pass by your place one morning,

I'll set four dogs on you.

One is called Tear-Apart, the other, Rip-the-Meat-off-the-Bone

Slowly, slowly, I'll drive you out!)

According to Ruth Finnegan's interpretation of the formula in oral poetry (1976), it is clear that one of the chief conventions of the modern villanella is theme itself, and within this sphere, the almost involutional development of the courtship motif. The formulaic devices of direct address and, secondarily, of soliloquy, dialogue, and the first-person narrative voice animate and intensify both theme and imagery.[28] Women are nearly always the protagonists of the villanella, the objects of its address, and the locus of its 'poetic art. The imagery draws from the natural worldflowers, trees, fruit, birds, serpents, and other animals; topography; parts of the human body, particularly the eyes, breasts, and hair. Such icons, often repeated in conceits extending throughout a poem, are associated with femininity and with states and processes adhering to women: beauty, fertility, sentiment, bonding, sexual penetration.

Figurative language can consist of various kinds of metaphor, such as synecdoche, personification, allusion, and occasionally punning. Sometimes it is regionally based, as in this mattinata (early-morning serenade), which is but one of many similar serenades found throughout south-central Italy. Individual couplets here are highly formulaic and easily interchangeable from one variant to another and can be added or subtracted, as Annunziato Chimento may have done here, without detracting from the sense and unity of the whole.

Risvìgliate, no cchiù dormire!

Lèvate l'uocchiu tua l'amato suonne!

Lu suonne a ttia te guaste sse uocchie bielle,

te guaste le vise quanne.duorme!

Risvìgliate allu cantu dell'accielle,

nun te fare engannare de lu suone!

Ca pe amare a ttia, Miennode bella,

ci ha perso la maggiore de lu suonne!

Tanne le finirò le mie affanne,

quanne alle braccia mie vieni a ci duorme.[29]

(Awake, sleep no more!

Lift beloved Sleep from your eyes!

Sleep is spoiling those pretty eyes,

Ravaging your countenance as you slumber.

Wake to the songs of the birds,

And let not Sleep deceive you.

For love of you, my Almond Flower,

I have lost all repose.

My sorrows will only come to an end

When to my arms you come to rest.)

More often, however, the figures are entirely original, unique to a single poem, and develop progressively throughout, building drama. This is the case in the next example, in which the eyes stand for a girl, and the metaphor is extended through two elaborate conceits. The first of these alludes to a beautiful woman, lost among suitors and temptations (the "sea," which has magical and erotic associations), and inclining to another man/family connection ("foreign parts"). The second dwells on the beauty and perfection of the eyes and the power associated with beauty.

Mienzo 'sto mare dua verde biell'uocchi

che dunano gran pena all'arma mia.

Pio pe li phigghiare e non li puozzo;

crio che si nne vanno alia straniera.

Vorrà sapire ssu mastro de ss'uocchi,

pe mi nne fare n'atro paro a mmia.

I vuogghio fatti cumo su li vuostri;

s'uocchi so bielli, me fannu morire.

Me fo morire e me fo pazziare,

e a nu fuoco fo stare d'arma mia.[30]

(Out in this sea, two pretty green eyes

Give torment to my soul.

I try to seize them and cannot;

I fancy they're drifting to foreign parts.

I would like to meet the maker of those eyes, To have another pair made for me.

I want them made like yours;

Those eyes are beautiful, they make me die. They make me die, they drive me mad,

They make a fire burn in my soul.)

A related device is that of using a single noun/image, such as "sleep," "night," or “heart" (the subject of the following song), repetitively and playfully throughout a text in both figurative and literal ways.

De corona ratiro una canzuna,

tutta da cora te voglio canteare.

Coro, ca te ricierche uno vaguro,

nu vuoglio n'atra amante te parlare.

Coro, che se ma fa chissu fagoru,

lu coro mio è du tuo, se de parleare.

Ca de du coro mio su lu patrunnu,

ma de du coro tuo m'e dare i chiave.[31]

(From my heart I draw out a song;

With all of my heart, I sing to you.

Heart, I seek a favor:

Let not another lover address you.

Heart, if you grant me this favor,

My heart is yours, and must speak to you.

For you are the mistress of my heart,

But to your own, you must give me the keys.)

Let us now look more closely at the sensuous imagery that permeates these songs. In the two classic mattinate quoted above, the courting male exhorts innocent beauty (dove, butterfly), in danger of being held in the power of Sleep beyond her time of maturation, to come to life sexually (wake up) and respond to his erotic call (song of the bird, bird being frequently a metonym for phallus).[32] The rose is a metaphor for a woman's imminent sexual awakening or opening (rose hanging from a bough, red rose of April) and woman's erotic life (blooming rose, mouth of roses; mouth and roses also being metony-mous with vulva). The elegant, spice-scented carnation, also a frequent image in southern Spanish folksongs, is a piquant aphrodisiac:

La rosa è belle e fa l'ordura assaie,

lu garofano è biello, e vinci cchitù.

(The rose is beautiful and sweet smelling,

The carnation is charming and more captivating.)

Or the girl sings, "Carnation of Love, let's go," to her lover, defying her parents. In these songs, the affinity of water, sea, and fountain images with the spume of erotic release and fulfillment is clear: "From the trunk [of a "tree loaded with diamonds"the fertile phallus] spouts a fountain." And

Viene, gioiuzza mia, e viene scatená

all'acqua frisca della tua funtana!

(Come, my joy, come and play

In the fresh waters of your fountain!)

Here is a teasing argument between a man and woman about sex, beautifully disguised in images of light and darkness, opening and closure, within a lattice of timethe hours of the day, the hours of love. "At my window no candle burns," a veiled metaphor for the fire that is said to burn between a woman's legs, can be understood as the denial of her desire, couched nonetheless in titillating language in this dialogue poem:

"È puno u sudo é fatto notto;

Bella, unne vedimme sta sera?"

"È furnó u iusso della notto,

alia fenestra mia un giarde cannila."

"Apre, bella mia, fenestra e porta,

ca l'ura è fatta, me aiu de jire."

“A porta mia none s'apre de notte,

venne de juorne chi me vuo vedire."

("The sun has sunk, night has come;

Beautiful, shall I see you tonight?"

"The right time of the night is past;

At my window no candle burns."

"Open, my beauty, window and door,

For the hour is come, and I must enter."

"My door doesn't open at night;

Those who seek me come by day.")

A leading motif of the villanella is the desirability of women, and even more, their inherent erotic power. In Calabrian folklore, feminine eros has a magical or supernatural dimension which emanates most strongly from the eyes, but is also associated with the hair. It is alluded to in the villanella with such imagery as a pair of green eyes floating in the sea, the "sweet eyes of a fascinator" (literally, serpent), and such epithets as "dark girl, you who do battle with the sun." A girl's linens not only announce her capacities and wealth, but also draw to her the man she wantsweaving and needlework were implicated in the practice and beliefs of love magic.

A ssi fenestre ssi bianchi panni,

de fore ci comiegnene d'entenne.

Ce voré mannare io dove ssa mamma,

se me donasse sse gioia de figlia.

U patri dici che era pittirilla;

a mamma dici ca nun avía le panne.

Illa se vota cu s'uocchi giranne:

"Garofado d'Amore, e iamme ninne!"[33]

(The white linens hanging at those windows

Invite our admiration from outside.

I want to send word to that mother

To give me her joy of a daughter!

Her father says she's too young,

Her mother that she has no linens.

But she turns around with flashing eyes

Saying, "Carnation of Love, let's go!")

Here, as in the next two examples, a woman declares her own desire. In Calabrian rural society, moreover, sexuality and reproduction do not appear to be compartmentalized, but are referents of one another as well as converging aspects of an integral state of being. The statement by a middle-aged Acretanu woman with seven children that "it [sex] is the happiness of the household" mirrors the frequently voiced maxim that "children are the joy of the family." The sentiment is charmingly conveyed in this villanella, a favorite among Acretani:

O giovaniello de zuccaro fatto,

ca si te vennera ta cattera d'io.

Pigghiera una vedanza e ti pesassi,

a una parte mettu d'uoru, e un'atra ttia.

Simpaticono mie!

Ca pu vedera quade cchitù gravasse,

e lassera l'uore e mi pigghierà ttia.

Ca d'uore se ne va a fedice spasso,

ed io cent'anni me guodo co ttia![34]

(O young man made of sugar,

If they were selling you, I'd buy you!

I'd take a scale and weigh you;

On one side I'd put gold, on the other,

you. Adorable one!

Then I would see which weighed the most,

And I'd leave the gold, and take you.

For gold vanishes with good times,

But you I can enjoy for a hundred years!

The cultural motifs emerging from this analysis are implicit in the romantic villanella texts as well. While erotic meaning is disguised, it shines through in the language of nature and its fertility. Because it was as difficult for men and women to approach one another as it was to reach the golden apples of the fairy tale, achieving this goal became a predominent theme of, and purpose for singing, villanella poetry.

Are those who transmit and receive the songs aware of the erotic burden of the texts? Is the figurative language interpreted by Acretani in the ways that I have suggested here? These are key questions because they lead us to an understanding of the place the villanelle heldand to some degree still holdsin Calabrian society. On the conscious level, insofar as I have been able to ascertain, even those with the most profound knowledge of the repertory do not interpret the texts this way. Rather, they seem entranced by the naturalistic beauty and wit of the poems and the magical coloring and powerful familiarity of the recurrent imagery. The imagery and "plot" of the songs hold for the insider a thousand connotations and awaken many personal memories and associations. The sensuous fantasy of the poetry, I believe, infuses singers and listeners with a liminal, but pleasurable, awareness of their underlying sexual content. Just as in dreams, latent meanings occasionally "poke through" their disguises in ways that are unmistakable to members of the cultureas in cases of clear, commonly used substitutions, such as "fig" for vulva.

This, too, is part of the artistry of the texts. The very fact that their erotic aspect is "covered" endows the poems with the power of discovery and releasean attribute of dreams and fantasiesin which those who sing and listen may indulge with freedom. For instance, of the following startlingly dreamlike paean to love and male potency in the feminine voice, singers offer a strictly literal interpretation. It is a favorite in the large repertoire of Bambina Luzzi, who is in her late forties and has raised six children and several grandchildren. Her handsome husband leads off the lines as they sing together:

Mienzo ssu chiano ci comieguerío,

un arbol caricata di diamanti.

Adura adura, la frunna cadía:

Cogliele, amure mie, ca su diamanti!

allu tringùnu 'na funtana eseía:

mera eumm'era frisca ed era gadante!

Allu eurino c'è lu bene mio

che duna resbiannuno a tutte quante![35]

(In the midst of this plain where we two meet,

Is a tree loaded with diamonds.

Heavy with perfume, its branches fall:

Gather them, my love, they're diamonds.

From the trunk spouts a fountain:

Look how fresh and fine it is!

At its crown is my beloved

Who gives splendor to everyone.

Dreams begin as private communions with the self. Acretani engage in dream reporting and interpretation, but share erotic dreams only with familiars of the same sex. The villanella texts are public declarations, heard and felt by all present, by both sexes, and sometimes the whole community. But because of their ambiguous and obscure language, the songs constitute a form of intimate discourse in a public setting. At the same time, the sensuous, preguant imagery with which they are filled creates an atmosphere in which lovemaking becomes a possibility. It is not to be imagined, however, that villanelle were traditionally performed by or for the courting couple alone, but rather a mix of ages and statuses. For the married and the middle-aged, moreover, the songs are intensely memory evoking and stimulating, imbuing their present with the excitement and passion of youth.

The many texts concerning the dark side of love strike another chord. It is one that is consonant with the performance style and emotional tone of the villanella. This, concurrently with eros a major sub-text of the genre, is lamentation. Villanella lyrics in this vein expose the talons of the social order I have outlined, which promoted a highly charged, but restrictive and often disappointing and brutal, connection between the sexes. It was all the more agonizing for women and poor people because sex and marriage were historically among the few avenues of pleasure, happiness, and self-realization open to these groups. Indeed, sexual and emotional disappointment and the feeling of "loneliness in a crowd" are believed to be leading causes of depression and suicide among men and women in southern Italy today.[36]

Writing of the relationship between the aesthetic conventions and social functions of Cretan funeral laments, Anna Caraveli argued that "[t]he main effects of lamentation on the women of the patriarchal Greek village society are to establish a strong sense of bonding among them, and to reinforce social roles and modes of interaction which can best serve as strategies for survival. Its effects on the community are the collective confrontation of death and the ensuing catharsis..." (Caraveli 1981; see also Caraveli-Chaves 1982). Similarly, the villanella permitted the members of two oppressed groupspoor men and their womento express together and to one another both the sorrows of their particular circumstances and those inherent in their respective and shared positions in society.

The lamentation formula derives form and power from a figurative language of torment (the "burning fire" and "tears of blood" of a discarded heart), deep sorrow ("my lament like thunder echoes"; "road of passion, now I leave you"), and desolation (“... in these caverns and in these valleys, my lament echoes"). It is dramatized through the repetition and recapitulation which occurs simultaneously in text, performance and melody, and grows, couplet by couplet, to a climax such as this: "But for one who loses the living, it's a burning fire/And every moment is yesterday." As with the erotic texts, the effect of this tripartite repetition and progressive intensification is one of an architecture of reasoned, artful argument woven into a grand, baroque crescendo of feeling. Imagery and metaphor, which in other contexts would be associated with tenderness, erotic pleasure, and fertility are inverted to invoke their opposites, as in "a hundred fountains spring from my eyes," and the "little breast of glass" (revealing a cruel heart). This device is used throughout the following dispetto to an emigrating lover:

E saputo ca all'America vu jire.

Ji lu diluvio pe ttia se vo voteare!

U bu troveare nè d'acqua nè vino,

si vuanno di siccheare li funteane!

Upu troveare chiesia pe ci jiri,

nemmen'i santi pe ti ci adoreare.

Mo vaie lunteane e pu ci arresimiglio:

Calabria bella, duve t'hai lasciate?

(I've heard you're leaving for America,

And may the deluge rain down upon you!

You'll find no water or wine,

And the fountains will run dry.

You'll find no church to enter,

Nor even saints to worship.

Now you are leaving, but later you will realize:

Beautiful Calabria, where have I left you!)

The Villanella and Mediterranean Cultural History