Mark Prince

Time and Place

James Benning interviewed by Mark Prince

The Wisconsin-born artist, educator, filmmaker and mathematician, discusses landscape, loneliness and ‘outsiderness’, the relationship between time and place, and finding ways to connect with people through the art of copying.

Mark Prince: Your exhibition ‘PLACE’ centres on a series of eight ten-minute film clips, each shot from a single, static viewpoint, of places where American artists, all of whom worked on the margins of the culture, lived and worked. One of the artists is fictitious. You have written short biographies of each in a pamphlet, which is also presented in the gallery, and your replicas of works by the seven artists who did exist are shown in conjunction with the films.

The title seems precise, although the exhibition transforms our perception of time as much as place by forcing a reset of the speed at which we tend to consume images these days. The viewer gradually becomes invested in the time you have brought to the detail of copying the paintings and patiently training your camera on the sites associated with them.

James Benning: Well, those are functions of time. Place is a function of time. You can’t tell if the wind is blowing in a place from a still photograph. I mean, you might if it’s a time-exposure, and it’s blurred. That would be constructing time in the photograph. It takes time to understand place. And the idea of this piece, of course, is to understand place in order to understand the people who lived in those places. I think of the whole project as a performance for one, for myself, and the installation as a summary or documentation of that performance. I’ve been interested in this group of artists for a number of years now. In fact, my interest in outsiderness started as early as 1980. I found out about Bill Traylor through a friend of mine, who bought a painting of his in the early 1980s, around the time of the black folk art show in Washington DC, at which he was discovered.</strong>

Thinking about that term ‘outsider artist’: some of these figures are by now quite well known — Forrest Bess, for instance — although they were outside the system when they were working.

I have a shot of the bayou where Forrest Bess lived, just off the coast of Texas, the Gulf of Mexico, where he was selling bait to fishermen to make a living, and painting in the middle of nowhere; he was truly an outsider. But he was corresponding with Betty Parsons Gallery in New York, and she showed him alongside those painters who were becoming famous at the time, such as Jackson Pollock. He studied architecture for a while, went to college, was in the military, and was released because he was badly beaten up for being gay, or letting people know that he was gay. Most of the people I’ve chosen didn’t have easy lives. They struggled with being outside the norm.

The replica paintings fit into a tradition which also includes the work of Sherrie Levine and Sturtevant, but those artists were mostly working from relatively remote art-historical titans, canonical figures. In your work — and now particularly when the paintings are seen in relation to the films you have made of the places where the artists lived — postmodern referencing shifts into the inductive logic of empiricism, where the fixed example of the past turns into the unpredictability of present experience. As I understand it, you come upon these artists as much through an identification with their lives, and sometimes a geographical and temporal proximity to them, as you do through an interest in their work.

I was interested in them early on, but I didn’t start copying their paintings until I bought property up in the Sierra Nevada mountains, where I had a house which I had reconstructed. When it was done, I thought, ‘What can I do out here in the middle of nowhere?’ And I thought, ‘I’ll teach myself to paint’ I always liked Traylor’s paintings, so I started with his. I thought they might be easy to do, then I realised that if I didn’t put them on the page just as he did, and develop the same kind of negative space around them, they completely lost their power. I needed to look closer at how he positioned the figures on the page and how he liked to use paper with flaws in it, which he could work around. I thought, people may call him an untrained artist, but he was a slave to begin with, then a working farmer for many years, so he knew about landscape, and how things fitted together, and when he puts something on the page it’s as though he was ploughing a field, and contra-ploughing, to make the ploughing fit into that landscape. I’m guessing at this, and maybe I’m romanticising, but I can imagine he learned about land through farming, and so when it’s said that he’s untrained, well maybe he’s got some better training. He really knows physical space from living his life in it.

The artists you have worked from created idiosyncratic, often fantastical pictorial worlds. They tended to be solipsistic and inward-looking. This contrasts with the objectivity you bring to the reconstruction process. Are you conscious of that difference when making them?

Yes, any kind of fallacy is removed. If they create an image with their own personal narrative, that’s removed for me. But in doing it, I try to imagine the narrative they brought to the painting. My interpretations may be wrong, but they give me another, stronger connection. I realise that if I have to do something that’s very precise, when I lean over the work and hold the brush in this way, knowing that Bill Traylor had these huge hands, I feel the difference in our stature.

An empathic process?

The show for me is a process in which I’m trying to know these people on many different levels. Copying the work is one way I feel empathy for what might have been on their minds when they were making that mark. But also thinking about how they lived: place has to have some effect on a person, and by going to these places, it’s clear that you can’t understand that in a few moments. So I make some five-minute shots that for a viewer can seem like an eternity, but it’s only the beginning of trying to understand what that place is like through its sound and movement.

Last year, at the premiere of your 2019 film Maggie’s Farm, you made a distinction between ‘observational space’ and ‘narrative space’, as if observation, in the long static shots, was anti-narrative. It’s a distinction which could be applied to structuralist filmmaking in general, but protracted observation creates its own narrative — a squirrel runs along a telegraph line, or someone exits a house and returns again a few minutes later — and through duration and concentration the image becomes a composition, whereas it seemed at first to be a contingent cropping of the landscape. At the same time, the camera’s focus on a space in which nothing appears to be happening brings us to realise all that it misses, in the history of the place which the parameters of the work imply. We come around to an intimation of all that you don’t find there, which the image can’t give you.

It’s the idea of looking harder at something, and how that happens over time. The changes may occur momentarily, or it may take years. I made a film called Nightfall six or seven years ago, from the top of a mountain where my cabins are. It’s simply a long, single shot from late afternoon to complete darkness — I think an hour and 45 minutes. It goes down to a black, which is created by the camera because it’s not as sensitive as my eyes were. It also records all the sounds.

Finally, the loud serenade of the crickets. Because it’s near where I live, I occasionally return to the spot, and over the past four or five years global warming has enabled pine bark beetles to survive through the winter, so they have spread from Montana all the way down to Southern California, killing millions of trees. Three or four years ago I went back and all the trees in my shot were dead, but what comes next is that you have all these dead trees in the Sierra Nevada, which provide fuel. One lightning strike — a careless person, or a person who wants to start a fire — and a huge amount of land gets burned, which is what just happened to this grove of trees. I might go back and remake the film. The road that goes up there has been closed, because the burned trees have fallen across it, but I imagine now it’s just black sticks, sticking up into the air.

When one sees a ten-minute clip of a place — the length of each of the shots which make up the PLACE film — it implies what may have happened in the past, but also what may be going to happen there in the future.

I think my film 13 Lakes, 2004, is about this. You have 13 large lakes, which are vulnerable to the way we take care of them, but which will all outlast us, just as the trees — maybe not the same trees — will probably regrow. We’ll be shaken off like flies. I think about time in that way. If I’m making the almost two-hour shot of nightfall, I’m aware that the trees weren’t there 25 years ago, or that they were small. But I couldn’t have imagined what was going to happen in the future, because it happened so quickly. So that function of time in relation to place is highly relative these days.

Your work has a diaristic quality, like a private travelogue, but it is also analytically objective. The sites you filmed for PLACE are partially determined by being where the artists whose work you have copied lived and worked. But in other films, such as 11 x 14 from 1977, locations which appear to be have been selected at random come to seem representative through the repetition of motifs across the span of the film. For instance, the harvested field becomes an emblem of a midwestern agrarian culture, while the views through a car window on the open highway evoke the American pioneer spirit. The nondescript periphery becomes a screen onto which we can project. Maggie’s Farm was filmed on the grounds of CalArts, where you teach, but you chose to film the landscaped borders of the property and unoccupied sections of the building, which are usually only accessed by maintenance workers rather than artists.

With PLACE, I’m interested in trying briefly to look at specific places where these artists worked. Whatever is there when I show up is what I get. But I do some research before travelling, then the shot is determined when I arrive, walk around and decide that a certain vantage provides the most information. On Jesse Howard’s farm, his house is behind those trees, which have grown and concealed it. So, I was recording what is different about the place. 11 x 14 shows places I was familiar with from living in, or escaping to, the black hills of South Dakota. That film is close to who I was at the time. I had my first teaching job at Northwestern, and moved to Chicago. I was living in Evanston and rode the L train from there to downtown.

Which appears in that long shot through the window as the train approaches the city.

I thought that this was really a privileged route because the train’s last stop was in Evanston then it went all the way downtown without stopping, and that the route was not going to last long because Evanston was losing its wealth and position, and the train passed through working-class areas without stopping. The route had been founded when Evanston had privilege, and at that time it still did because of Northwestern. I don’t know if that route still exists, but I purposely created that shot because it meant that I don’t have to ride with the working classes: what kind of classist crap is this? I don’t think you see it in the shot, but the train passes by Wrigley Field, which is for me a working-class symbol in Chicago.

I am aware of the genesis of those images in my own life. I know my personal involvement in them. But for spectators, they may appear generic or symbolic, or remind them of their own experience, so the audience sees many different films, depending on their point of view, and their own privilege or lack of it.

If you have made a painting and find you are not satisfied with it, is there a difference between it not being good enough as a painting and it not being good enough as a replica of the original — or is that in practice, for you, the same difference?

Generally, I choose works that I’m really moved by, and I know that from my point of view they are strong paintings. So, when I make one and it doesn’t have that quality, I get very depressed. The ones in this show, while not being exact copies by any means, are for me very close to giving me the same feelings. I made them over the past year, some taking quite a while, others coming quite quickly. Some of these have more detail to them: I made the paper for the Martin Ramírez painting the way he did. He used potatoes to make paste, and he would paste different kinds of paper together to create bigger sheets of paper, and I noticed in a few of the paintings he would have text bleeding through, which I had never noticed before.

When I saw that shadow of newsprint I thought this was a detail which surely was not exactly as it had been in the original.

But it could have been, because when I made copies of Henry Darger’s early work, in which he used Christmas seals and stamps from 1933, I went online and I bought sheets of those, so I could reconstruct it. It becomes more of a game for me. I love looking for old frames in flea markets and cheap antique stores. This might be a passion which is unique to what I’m doing and not so much part of the process of getting to know them better.

You are following in these artists’ footsteps, identifying with them by doing what they did. I take it you wouldn’t replicate the work of someone with whom you felt no identification at all, would you?

No, I don’t think so. At first, I was just fooling around. I liked Traylor’s paintings and I knew I couldn’t afford one, so I started to try to make them, and I thought, this is silly, I need to learn something from this and think about why I’m even doing it. I then realised that I really was interested in who these people were, where they came from and what the process of copying their work could teach me about them. Maybe I became more interested in the person than the painting, but I needed to learn the paintings well to know the person. It was their personalities and their lives I was drawn to. They were all obsessive, and I am too. If I wake up in the morning I’m depressed if I don’t start working immediately. It’s an anxiety which comes from a few drug experiences when I was young. To get through two or three anxious years I became a workaholic, which allowed me to focus so clearly on something else that these anxieties would disappear when I was fully engaged in the work. I think some of that has grown into this work because I see the work of these artists coming out of some kind of anxiety too, they’re covering something up. I don’t see this as a bad way of working. It has provided me with a way of getting a lot done.

But their positions interest me more than my own. I’m aware that I can fit into an art world, maybe even want some success in that world, not in a monetary way, but in terms of somebody coming to talk to me rather than not talk to me. And that also applied to a few of these artists. Certainly, Bess wanted attention. And Bill Traylor left this whole other world behind when he moved out of his apartment and into a rest home. He didn’t destroy it and he wrote an autobiography: he left things. But one can argue that maybe he never meant for anyone to see any of it. Ramírez needed to work to stay alive, given the conditions he lived in within the mental institution.

The first time these paintings were presented was on the walls of the cabin in the Sierra Nevada mountains, which you modelled on the one Henry David Thoreau built in the mid 19th century in Concord, Massachusetts. Do you see Thoreau’s pursuit of integrity and focus through solitude, as exemplified by the single-occupant cabin in the woods and the two years he spent living in it alone, as an original template for the stories of these artists? Obviously, there are differences — Thoreau had an active social and political life — but his writing’s emphasis on isolating oneself and communing with nature as a route to self-definition seems to be a thread running through these various narratives.

He certainly lived for a couple of years on his own, built his own house, but he was also a hundred yards from his mother’s house. And he was politically connected in the anti-slavery movement, and helped run the underground railroad.

And the cabin was on Ralph Waldo Emerson’s land.

Yes, but I suspect he died a virgin, which connects to Ted Kaczynski — the former mathematics professor and American domestic terrorist, known as the Unabomber — who I suspect is probably still a virgin (although if he reads this he’s not going to like me saying that). So, you could say that there’s an awkwardness in the people I have been interested in.

But when I built the Thoreau cabin, it wasn’t part of an art project. I’d had so much fun reconstructing my house, then I started to make these paintings, and I thought I needed to do some more physical work. I built the Thoreau cabin first. I had wanted to build a house, but thought that I’m too old to do it, so I would build a small one, a quintessential small house, so I thought I would use the dimensions of Thoreau’s cabin. When it was finished, I put up some of the paintings I had been making, just to decorate it, and that was when I saw that this was not just about learning how to build a house or how to paint, it was talking about what Thoreau was looking for, as well as what I was doing up there, and whether I had a connection to that. Then I thought back to my 1984 film American Dreams (lost and found), for which I used the baseball cards of Henry Aaron. I had started with songs and political speeches from those years, but felt it needed a counterpoint to that, so I decided to use the diary of Arthur Bremer, who attempted to assassinate the American Democratic governor George Wallace in 1972.

By a counterpoint, you mean something more dangerous?

Something that would punch at it. I thought I would write a diary as if I were an assassin. It was going to be fictional. I would make believe Arthur Bremer had a diary. Then when I went to the library to do some research, I found he had actually written one. ‘This is becoming easy,’ I thought. So, when I built the Thoreau cabin, I thought it needed an Arthur Bremer.

You already knew about Kaczynski’s cabin?

I was interested in the Unabomber in the early 1980s, when he was becoming the bogey man. I went to school in Madison, Wisconsin, where four young men in the late 1960s blew up the Army math research building. Three of them were caught, but one, Leo Burt, never was. All of my friends thought maybe he was the Unabomber. And I had a few friends who were interviewed by police: a filmmaker who taught in Nashville, who made artwork using fireworks and small explosives, so he was interviewed quite soon. I think Tony Conrad was interviewed too. Conrad studied maths at Harvard, like Kaczynski, and around the same time, although I don’t think they knew each other, but I built the Kaczynski cabin for the same reason I added Bremer to the film. And in this case, unlike with the Thoreau cabin, it was an exact replica of the original.

You have previously said that you found the beam construction of the Kaczynski cabin’s roof was unbalanced, or asymmetrical in some way, but that it turned out to be more stable for that, which reminds me of your comparison of Bill Traylor’s method of painting with the ploughing and counter-ploughing of a field.

I found the joists didn’t match, but that seemed to lessen the torque when they did match, so it was functional. My friend Julie Ault has been corresponding with Kaczynski, and asked him about this, but he denied it. Maybe he was a genius builder and didn’t know what he was doing, or maybe he had forgotten, but once I had built the two cabins — they’re about 50 yards from one another and from my house — the paintings made more sense to me. I saw they formed a larger topic of being on the edge of things, on the outside, thinking differently, and how that can go awry.

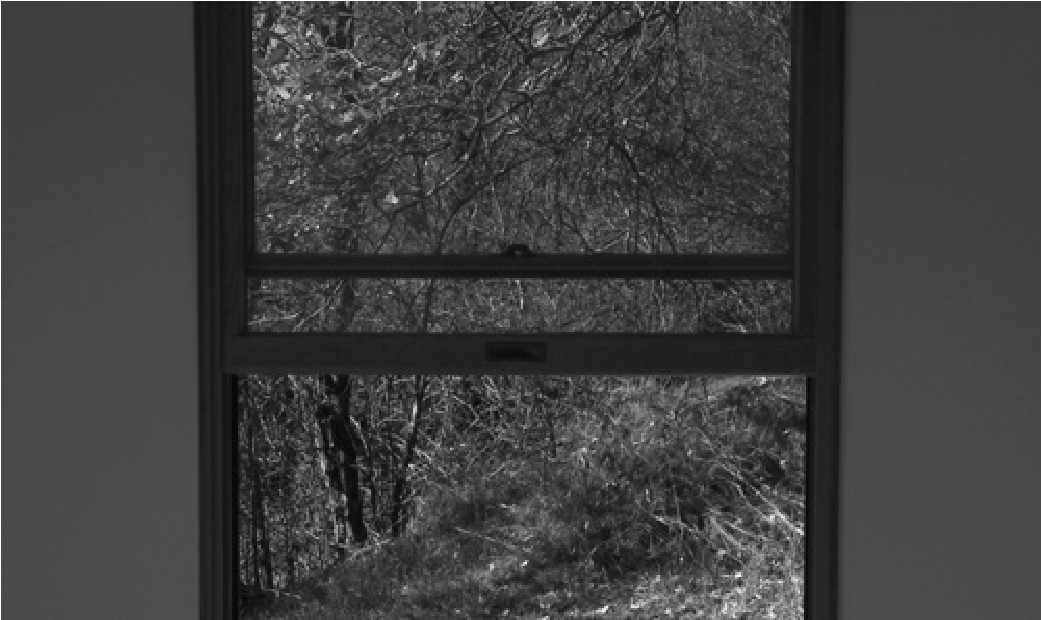

The first time I saw documentation of the Two Cabins project was in an exhibition in which you showed a film of the surrounding landscape shot through the window of one of the cabins. The shot’s vantage appeared as a metaphor for the camera’s aperture, with the darker cabin as its chamber, which associated your camera with the solitude, concentration and isolation of the occupants of the original cabins, and also, by extension, of the artists whose paintings you had copied.

It was shot through the small, 15” by 15” window of the Kaczynski cabin. The metaphorical dimension became apparent when I was filming. The fact that there were two cabins — one Thoreau, one Kaczynski — opened up a comparison between the two different architectures and how they were constructed by these two different ideologies. The Kaczyński cabin has two windows, one halfway up the wall — the one I shot out of — with the desk below on which he worked, so he could sit at the desk and look out the window. I also built the desk. The other window is higher and goes up to the ceiling, and you can stand and look out of it. One of them you can look out of when you’re sitting, the other when you’re standing. And they’re small because it gets very cold up in the mountains of Montana, so it’s all very functional.

Another thing regarding the paintings and their connection to the cabins — and I’m not sure if I’m ready to defend this — is that all of those artists I have been affected by have been men. I purposely made the fictitious painter in the exhibition a woman for that reason. The hand-pressed booklet I wrote contains eight biographies. Seven correspond to the paintings in the show, the eighth one to the shot of the wall painting in Utah, which is probably 2,000 years old.

It’s claimed that it was painted by a man, but all those pictographs and petroglyphs have designs similar to those which appear on pottery, and the people who have studied this have claimed that the pottery was made by women, the paintings by men. I don’t know why they came to that conclusion. I have written a very romanticised view of a young woman who received the holy rite to paint on the cabin walls. I have her born in 1064AD. More accurately, she would probably have been born before Christ, because those paintings can be up to 4,000 years old, although there are a couple of other paintings on the wall in that shot which are probably from a different period. There are maybe three different cultures represented. They are painted in a mixture of different berry juices, urine and egg white. Whatever it was that they concocted, it has lasted 4,000 years.

It was significant to you that the one fictitious artist among the group was a woman?

I didn’t agree with the scholarship which came to these conclusions, but I also made it a woman because I thought of the inadequacy of my own upbringing, in the 1950s, in this sexist reporting of how things are. But I’m not going to make believe I was inspired by outsider women artists that I know of now, but didn’t back then because of the culture I was in. And I don’t want to even try to defend that position. These are serious topics, but I am who I am; I’m not going to say I was a different person, with different influences. But it bothers me, because I could have learned a lot more. If the Bible wasn’t sexist I think I would be in a better position. There were a number of female artists around the same time, but not many, who would fit into this outsider category. It might be a matter of a certain male privilege. Jesse Howard, one of the artists I have copied, is interesting, because he was a hard-working farmer, but his wife was a schoolteacher, she had a job that could be relied on, and so he became a guy that got ornery and painted signs. But that’s an unusual situation, too, not a cliché at all in the social context of the time, that a woman’s taking care of business and he’s yelling at his neighbours.

When I taught high-school math for a year in Missouri I was living 30 miles from Howard and didn’t know it. He painted until he was 94, up until the 1980s. I could have visited him, in theory. I wish I had a time machine.

James Benning‘s exhibition ‘PLACE’ continues at neugerriemschneider, Berlin until 31 December.

Mark Prince is an artist and critic based in Berlin.