Michael Balter

Early Start for Human Art? Ochre May Revise Timeline

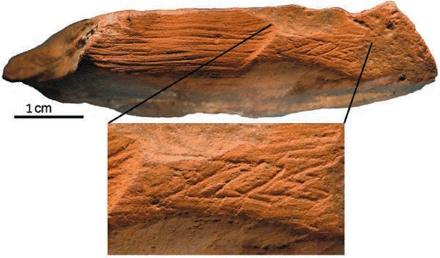

In 2002, a discovery at Blombos Cave in South Africa began to change how researchers view the evolution of modern human behavior. Archaeologists reported finding two pieces of red ochre engraved with crosshatched patterns, dated to 77,000 years ago. Many experts interpreted the etchings as evidence of symbolic expression and possibly even art, 40,000 years earlier than many researchers had thought (Science, 11 January 2002, p. 247). Now the Blombos team reports on an additional 13 engraved ochre pieces, many dated to 100,000 years ago. The researchers suggest that some of the engravings may represent an artistic or symbolic tradition. If so, the timeline for the earliest known symbolic behavior must once again be redrawn.

“[I] almost fell off my chair” on seeing the latest ochre etchings, says archaeologist Paul Mellars of the University of Cambridge in the United Kingdom. At least some “are unquestionably deliberate designs; … they have to be some kind of symbols,” he says. Archaeologist Paul Pettitt of the University of Sheffield, U.K., a skeptic about the original discovery, says, “The new material removes any doubt whatsoever.”

Others remain cautious, however, suggesting that the etched lines may have been produced incidentally when working ochre for utilitarian reasons.

Pettitt, Mellars, and other experts attended a meeting earlier this month in Cape Town, South Africa, where the Blombos paper was presented; it is also in press at the Journal of Human Evolution (JHE). After the meeting, researchers toured the site, which has become crucial for understanding early human behavior. Archaeologist Christopher Henshilwood of the University of the Witwatersrand in Johannesburg, South Africa, lead author and the cave's discoverer, has reported numerous signs of apparent symbolic behavior from Blombos, including incised ochre, shell beads, and sophisticated tools, all presumably crafted by Homo sapiens (Science, 16 April 2004, p. 369). Blombos is one of several sites in Africa and the Near East that have challenged the notion that full-fledged symbolism, such as cave paintings, did not appear before about 40,000 years ago in Europe. “There is now no question that explicitly symbolic behavior was taking place by 100,000 years ago or earlier,” says Mellars.

He and others say that the Blombos dates seem accurate. Henshilwood's team has used at least four dating methods, including optically stimulated luminescence (OSL) dating of quartz grains from the cave's sediments and thermoluminescence dating of stone tools. The most recent round of OSL dating put the earliest archaeological levels at Blombos—where eight of the 13 new ochre pieces were found—at about 99,000 years ago. “The stratigraphy is impeccable, with remarkably well-layered and discrete lenses of material,” says Pettitt, a dating expert.

Engravings on this ancient ochre may have had symbolic meanings.

CREDIT: CHRISTOPHER HENSHILWOOD AND FRANCESCO D'ERRICO

To analyze the latest finds, Henshilwood teamed up with Francesco d'Errico of the University of Bordeaux in France and independent ochre expert Ian Watts, who is based in Athens. The trick with ancient ochre is to figure out what early humans were using it for. Many previous studies have concluded that ochre was often ground to make a powder, which could have been used to paint bodies—a form of social identification usually considered symbolic—or for more utilitarian purposes. For example, Lynnette Wadley of Witwatersrand has argued from modern-day experiments that ground ochre could have been used as a kind of glue to haft stone tools into wooden or bone handles.

So Henshilwood and colleagues focused their attention on 13 pieces engraved in ways that seemed inconsistent with grinding alone. Some pieces have lines arranged in apparent fan-shaped or crosshatched designs; others are etched in wavy patterns. Microscopic examination showed that these engravings had been made with a pointed stone tool and a finely controlled hand.

Wadley agrees that “some of the pieces seem engraved for reasons other than ochre powder removal,” although she is not yet convinced that those reasons were symbolic. Archaeologist Richard Klein of Stanford University in Palo Alto, California, says that ultimately the question of whether the engravings were symbolic “is not something that science can resolve.” The team points out, however, that some of the oldest pieces have a crosshatched pattern similar to that of the two original ochre pieces dated to 77,000 years ago. And other researchers have very recently discovered similar crosshatched patterns on a few African stone and bone objects thought to be as old as the new finds, or nearly so. This refutes suggestions that the marks are merely doodles, Henshilwood says, and suggests a 25,000-year tradition of symbolic representation.

If so, modern humans were probably engaging in symbolic behavior even before the 100,000-year mark at Blombos and possibly since the origin of our species, sometime between 160,000 and 200,000 years ago, says Mellars.

Still, even if the engravings are symbolic, Klein says, the question remains: “What did they symbolize?” Researchers agree that we may never know.