Michael Crichton

Jurassic Park Series

PROLOGUE: THE BITE OF THE RAPTOR

WHEN DINOSAURS RULED

THE EARTH

Introduction: “Extinction at the K-T Boundary”

Prologue:

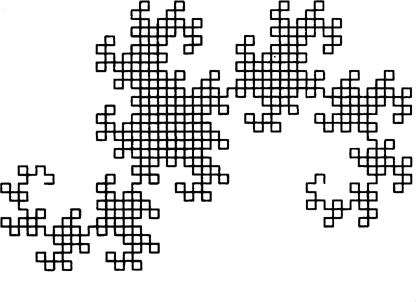

“Life at the Edge of Chaos”

Young Johnson Joins the Field Trip West

Jurassic Park: A Novel

Front Matter

Praise for the book

“A TAUT THRILLER …

FASCINATING …

Crichton is a master at blending edge-of-the-chair adventure and a scientific seminar, educating his readers as he entertains them.”

—St. Louis Post-Dispatch

“Crichton combines his knowledge of science with a great talent for creating suspense.… Fast-moving.”

—San Francisco Chronicle

“Crichton is remarkably realistic with his depictions of what it could be like if genetic engineering created a theme park full of carefully modified dinosaurs—and the terrible lizards got out of control.”

—USA Today

“Crichton’s notion is wonderful precisely because nothing about it is entirely outside the realm of possibility.… He presents an astonishingly plausible case that a lot of money and a little bit of luck are all one would need to make this book’s unlikely scenario become real.”

—The Cleveland Plain Dealer

“Intellectually provocative, high-octane entertainment.”

—New York Newsday

“AN EXCITING, FAST-PACED

TALE THAT’S HARD TO

PUT DOWN.”

—Milwaukee Journal

“Riveting … A winning blend of action, suspense, and information.”

—Detroit Free Press

“Exciting … Frightening.”

—The New York Times

“Ingenious … JURASSIC PARK is hard to beat for sheer intellectual entertainment.”

—Entertainment Weekly

“A winner … Highly entertaining … Michael Crichton has written a thriller combining sophisticated biotechnology with prehistoric legend. And what a thriller it is.”

—St. Petersburg Times

“[A] DEFT SCIENTIFIC

THRILLER … A SNAPPY

NIGHTMARE OF SCIENCE

RUN AMOK.

—The Wall Street Journal

“Crichton’s dinosaurs are genuinely frightening.”

—Chicago Sun-Times

“Crichton’s sci-fi is convincingly detailed.”

—Time Magazine

“Vastly entertaining … [A] tornado-paced tale … Easily the most exciting dinosaur novel ever written. A sure-fire bestseller.”

—Kirkus Reviews

“A scary, creepy, mesmerizing techno-thriller with teeth.”

—Publishers Weekly

“By far the best science fiction I have read since Jules Verne in my youth.”

—John Barkham Review

Title Page

Publisher Details

A Ballantine Book

Published by The Random House Publishing Group

1990 by Michael Crichton

Published in the United States by Ballantine Books, an imprint of The Random House Publishing Group, a division of Random House, Inc., New York, and simultaneously in Canada by Random House of Canada Limited, Toronto.

Ballantine and colophon are registered trademarks of Random House, Inc.

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 90-52960

eISBN: 978-0-307-76305-1

The edition published by arrangement with Alfred A. Knopf, Inc.

v3.1_r5

Contents

-

Cover

-

Title Page

-

Copyright

-

Dedication

-

Epigraph

-

Introduction

-

Prologue: The Bite of the Raptor

-

First Iteration

-

Almost Paradise

-

Puntarenas

-

The Beach

-

New York

-

The Shape of the Data

-

Second Iteration

-

The Shore of the Inland Sea

-

Skeleton

-

Cowan, Swain and Ross

-

Plans

-

Hammond

-

Choteau

-

Target of Opportunity

-

Airport

-

Malcolm

-

Isla Nublar

-

Welcome

-

Third Iteration

-

Jurassic Park

-

When Dinosaurs Ruled the Earth

-

The Tour

-

Control

-

Version 4.4

-

Control

-

The Tour

-

Control

-

Big Rex

-

Control

-

Stegosaur

-

Control

-

Breeding Sites

-

Fourth Iteration

-

The Main Road

-

Return

-

Nedry

-

Bungalow

-

Tim

-

Lex

-

Control

-

The Road

-

Control

-

In the Park

-

Control

-

The Park

-

Dawn

-

The Park

-

Fifth Iteration

-

Search

-

Aviary

-

Tyrannosaur

-

Control

-

Sixth Iteration

-

Return

-

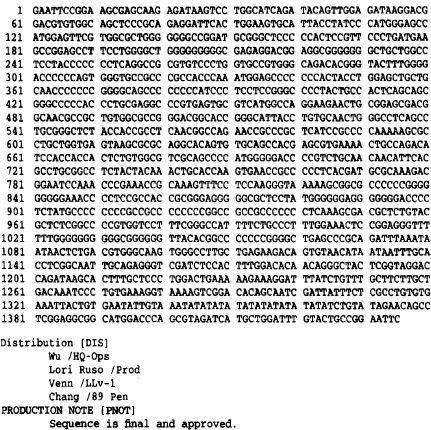

The Grid

-

Lodge

-

Control

-

Seventh Iteration

-

Destroying the World

-

Under Control

-

Almost Paradigm

-

Descent

-

Hammond

-

The Beach

-

Approaching Dark

-

Epilogue: San José

-

Acknowledgments

-

Books by Michael Crichton

-

About the Author

Dedication

For A-M

and

T

Epigraph

“Reptiles are abhorrent because of their cold body, pale color, cartilaginous skeleton, filthy skin, fierce aspect, calculating eye, offensive smell, harsh voice, squalid habitation, and terrible venom; wherefore their Creator has not exerted his powers to make many of them.”

LINNAEUS, 1797

“You cannot recall a new form of life.”

ERWIN CHARGAFF, 1972

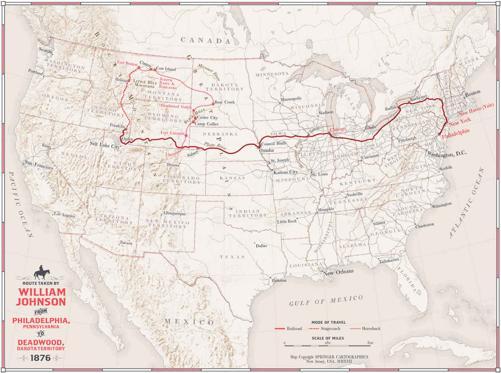

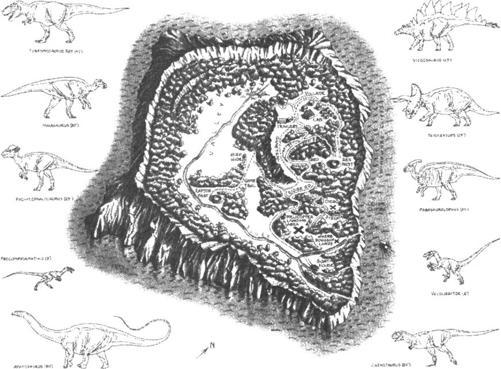

Map

INTRODUCTION

“The InGen Incident”

The late twentieth century has witnessed a scientific gold rush of astonishing proportions: the headlong and furious haste to commercialize genetic engineering. This enterprise has proceeded so rapidly—with so little outside commentary—that its dimensions and implications are hardly understood at all.

Biotechnology promises the greatest revolution in human history. By the end of this decade, it will have outdistanced atomic power and computers in its effect on our everyday lives. In the words of one observer, “Biotechnology is going to transform every aspect of human life: our medical care, our food, our health, our entertainment, our very bodies. Nothing will ever be the same again. It’s literally going to change the face of the planet.”

But the biotechnology revolution differs in three important respects from past scientific transformations.

First, it is broad-based. America entered the atomic age through the work of a single research institution, at Los Alamos. It entered the computer age through the efforts of about a dozen companies. But biotechnology research is now carried out in more than two thousand laboratories in America alone. Five hundred corporations spend five billion dollars a year on this technology.

Second, much of the research is thoughtless or frivolous. Efforts to engineer paler trout for better visibility in the stream, square trees for easier lumbering, and injectable scent cells so you’ll always smell of your favorite perfume may seem like a joke, but they are not. Indeed, the fact that biotechnology can be applied to the industries traditionally subject to the vagaries of fashion, such as cosmetics and leisure activities, heightens concern about the whimsical use of this powerful new technology.

Third, the work is uncontrolled. No one supervises it. No federal laws regulate it. There is no coherent government policy, in America or anywhere else in the world. And because the products of biotechnology range from drugs to farm crops to artificial snow, an intelligent policy is difficult.

But most disturbing is the fact that no watchdogs are found among scientists themselves. It is remarkable that nearly every scientist in genetics research is also engaged in the commerce of biotechnology. There are no detached observers. Everybody has a stake.

The commercialization of molecular biology is the most stunning ethical event in the history of science, and it has happened with astonishing speed. For four hundred years since Galileo, science has always proceeded as a free and open inquiry into the workings of nature. Scientists have always ignored national boundaries, holding themselves above the transitory concerns of politics and even wars. Scientists have always rebelled against secrecy in research, and have even frowned on the idea of patenting their discoveries, seeing themselves as working to the benefit of all mankind. And for many generations, the discoveries of scientists did indeed have a peculiarly selfless quality.

When, in 1953, two young researchers in England, James Watson and Francis Crick, deciphered the structure of DNA, their work was hailed as a triumph of the human spirit, of the centuries-old quest to understand the universe in a scientific way. It was confidently expected that their discovery would be selflessly extended to the greater benefit of mankind.

Yet that did not happen. Thirty years later, nearly all of Watson and Crick’s scientific colleagues were engaged in another sort of enterprise entirely. Research in molecular genetics had become a vast, multibillion-dollar commercial undertaking, and its origins can be traced not to 1953 but to April 1976.

That was the date of a now famous meeting, in which Robert Swanson, a venture capitalist, approached Herbert Boyer, a biochemist at the University of California. The two men agreed to found a commercial company to exploit Boyer’s gene-splicing techniques. Their new company, Genentech, quickly became the largest and most successful of the genetic engineering start-ups.

Suddenly it seemed as if everyone wanted to become rich. New companies were announced almost weekly, and scientists flocked to exploit genetic research. By 1986, at least 362 scientists, including 64 in the National Academy, sat on the advisory boards of biotech firms. The number of those who held equity positions or consultancies was several times greater.

It is necessary to emphasize how significant this shift in attitude actually was. In the past, pure scientists took a snobbish view of business. They saw the pursuit of money as intellectually uninteresting, suited only to shopkeepers. And to do research for industry, even at the prestigious Bell or IBM labs, was only for those who couldn’t get a university appointment. Thus the attitude of pure scientists was fundamentally critical toward the work of applied scientists, and to industry in general. Their long-standing antagonism kept university scientists free of contaminating industry ties, and whenever debate arose about technological matters, disinterested scientists were available to discuss the issues at the highest levels.

But that is no longer true. There are very few molecular biologists and very few research institutions without commercial affiliations. The old days are gone. Genetic research continues, at a more furious pace than ever. But it is done in secret, and in haste, and for profit.

In this commercial climate, it is probably inevitable that a company as ambitious as International Genetic Technologies, Inc., of Palo Alto, would arise. It is equally unsurprising that the genetic crisis it created should go unreported. After all, InGen’s research was conducted in secret; the actual incident occurred in the most remote region of Central America; and fewer than twenty people were there to witness it. Of those, only a handful survived.

Even at the end, when International Genetic Technologies filed for Chapter 11 protection in United States Bankruptcy Court in San Francisco on October 5, 1989, the proceedings drew little press attention. It appeared so ordinary: InGen was the third small American bioengineering company to fail that year, and the seventh since 1986. Few court documents were made public, since the creditors were Japanese investment consortia, such as Hamaguri and Densaka, companies which traditionally shun publicity. To avoid unnecessary disclosure, Daniel Ross, of Cowan, Swain and Ross, counsel for InGen, also represented the Japanese investors. And the rather unusual petition of the vice consul of Costa Rica was heard behind closed doors. Thus it is not surprising that, within a month, the problems of InGen were quietly and amicably settled.

Parties to that settlement, including the distinguished scientific board of advisers, signed a nondisclosure agreement, and none will speak about what happened; but many of the principal figures in the “InGen incident” are not signatories, and were willing to discuss the remarkable events leading up to those final two days in August 1989 on a remote island off the west coast of Costa Rica.

PROLOGUE: THE BITE OF THE RAPTOR

The tropical rain fell in drenching sheets, hammering the corrugated roof of the clinic building, roaring down the metal gutters, splashing on the ground in a torrent. Roberta Carter sighed, and stared out the window. From the clinic, she could hardly see the beach or the ocean beyond, cloaked in low fog. This wasn’t what she had expected when she had come to the fishing village of Bahía Anasco, on the west coast of Costa Rica, to spend two months as a visiting physician. Bobbie Carter had expected sun and relaxation, after two grueling years of residency in emergency medicine at Michael Reese in Chicago.

She had been in Bahía Anasco now for three weeks. And it had rained every day.

Everything else was fine. She liked the isolation of Bahía Anasco, and the friendliness of its people. Costa Rica had one of the twenty best medical systems in the world, and even in this remote coastal village, the clinic was well maintained, amply supplied. Her paramedic, Manuel Aragón, was intelligent and well trained. Bobbie was able to practice a level of medicine equal to what she had practiced in Chicago.

But the rain! The constant, unending rain!

Across the examining room, Manuel cocked his head. “Listen,” he said.

“Believe me, I hear it,” Bobbie said.

“No. Listen.”

And then she caught it, another sound blended with the rain, a deeper rumble that built and emerged until it was clear: the rhythmic thumping of a helicopter. She thought, They can’t be flying in weather like this.

But the sound built steadily, and then the helicopter burst low through the ocean fog and roared overhead, circled, and came back. She saw the helicopter swing back over the water, near the fishing boats, then ease sideways to the rickety wooden dock, and back toward the beach.

It was looking for a place to land.

It was a big-bellied Sikorsky with a blue stripe on the side, with the words “InGen Construction.” That was the name of the construction company building a new resort on one of the offshore islands. The resort was said to be spectacular, and very complicated; many of the local people were employed in the construction, which had been going on for more than two years. Bobbie could imagine it—one of those huge American resorts with swimming pools and tennis courts, where guests could play and drink their daiquiris, without having any contact with the real life of the country.

Bobbie wondered what was so urgent on that island that the helicopter would fly in this weather. Through the windshield she saw the pilot exhale in relief as the helicopter settled onto the wet sand of the beach. Uniformed men jumped out, and flung open the big side door. She heard frantic shouts in Spanish, and Manuel nudged her.

They were calling for a doctor.

Two black crewmen carried a limp body toward her, while a white man barked orders. The white man had a yellow slicker. Red hair appeared around the edges of his Mets baseball cap. “Is there a doctor here?” he called to her, as she ran up.

“I’m Dr. Carter,” she said. The rain fell in heavy drops, pounding her head and shoulders. The red-haired man frowned at her. She was wearing cut-off jeans and a tank top. She had a stethoscope over her shoulder, the bell already rusted from the salt air.

“Ed Regis. We’ve got a very sick man here, doctor.”

“Then you better take him to San José,” she said. San José was the capital, just twenty minutes away by air.

“We would, but we can’t get over the mountains in this weather. You have to treat him here.”

Bobbie trotted alongside the injured man as they carried him to the clinic. He was a kid, no older than eighteen. Lifting away the blood-soaked shirt, she saw a big slashing rip along his shoulder, and another on the leg.

“What happened to him?”

“Construction accident,” Ed shouted. “He fell. One of the backhoes ran over him.”

The kid was pale, shivering, unconscious.

Manuel stood by the bright green door of the clinic, waving his arm. The men brought the body through and set it on the table in the center of the room. Manuel started an intravenous line, and Bobbie swung the light over the kid and bent to examine the wounds. Immediately she could see that it did not look good. The kid would almost certainly die.

A big tearing laceration ran from his shoulder down his torso. At the edge of the wound, the flesh was shredded. At the center, the shoulder was dislocated, pale bones exposed. A second slash cut through the heavy muscles of the thigh, deep enough to reveal the pulse of the femoral artery below. Her first impression was that his leg had been ripped open.

“Tell me again about this injury,” she said.

“I didn’t see it,” Ed said. “They say the backhoe dragged him.”

“Because it almost looks as if he was mauled,” Bobbie Carter said, probing the wound. Like most emergency room physicians, she could remember in detail patients she had seen even years before. She had seen two maulings. One was a two-year-old child who had been attacked by a rottweiler dog. The other was a drunken circus attendant who had had an encounter with a Bengal tiger. Both injuries were similar. There was a characteristic look to an animal attack.

“Mauled?” Ed said. “No, no. It was a backhoe, believe me.” Ed licked his lips as he spoke. He was edgy, acting as if he had done something wrong. Bobbie wondered why. If they were using inexperienced local workmen on the resort construction, they must have accidents all the time.

Manuel said, “Do you want lavage?”

“Yes,” she said. “After you block him.”

She bent lower, probed the wound with her fingertips. If an earth mover had rolled over him, dirt would be forced deep into the wound. But there wasn’t any dirt, just a slippery, slimy foam. And the wound had a strange odor, a kind of rotten stench, a smell of death and decay. She had never smelled anything like it before.

“How long ago did this happen?”

“An hour.”

Again she noticed how tense Ed Regis was. He was one of those eager, nervous types. And he didn’t look like a construction foreman. More like an executive. He was obviously out of his depth.

Bobbie Carter turned back to the injuries. Somehow she didn’t think she was seeing mechanical trauma. It just didn’t look right. No soil contamination of the wound site, and no crush-injury component. Mechanical trauma of any sort—an auto injury, a factory accident—almost always had some component of crushing. But here there was none. Instead, the man’s skin was shredded—ripped—across his shoulder, and again across his thigh.

It really did look like a maul. On the other hand, most of the body was unmarked, which was unusual for an animal attack. She looked again at the head, the arms, the hands—

The hands.

She felt a chill when she looked at the kid’s hands. There were short slashing cuts on both palms, and bruises on the wrists and forearms. She had worked in Chicago long enough to know what that meant.

“All right,” she said. “Wait outside.”

“Why?” Ed said, alarmed. He didn’t like that.

“Do you want me to help him, or not?” she said, and pushed him out the door and closed it on his face. She didn’t know what was going on, but she didn’t like it. Manuel hesitated. “I continue to wash?”

“Yes,” she said. She reached for her little Olympus point-and-shoot. She took several snapshots of the injury, shifting her light for a better view. It really did look like bites, she thought. Then the kid groaned, and she put her camera aside and bent toward him. His lips moved, his tongue thick.

“Raptor,” he said. “Lo sa raptor…”

At those words, Manuel froze, stepped back in horror.

“What does it mean?” Bobbie said.

Manuel shook his head. “I do not know, doctor. ‘Lo sa raptor’—no es español.”

“No?” It sounded to her like Spanish. “Then please continue to wash him.”

“No, doctor.” He wrinkled his nose. “Bad smell.” And he crossed himself.

Bobbie looked again at the slippery foam streaked across the wound. She touched it, rubbing it between her fingers. It seemed almost like saliva.…

The injured boy’s lips moved. “Raptor,” he whispered.

In a tone of horror, Manuel said, “It bit him.”

“What bit him?”

“Raptor.”

“What’s a raptor?”

“It means hupia.”

Bobbie frowned. The Costa Ricans were not especially superstitious, but she had heard the hupia mentioned in the village before. They were said to be night ghosts, faceless vampires who kidnapped small children. According to the belief, the hupia had once lived in the mountains of Costa Rica, but now inhabited the islands offshore.

Manuel was backing away, murmuring and crossing himself. “It is not normal, this smell,” he said. “It is the hupia.”

Bobbie was about to order him back to work when the injured youth opened his eyes and sat straight up on the table. Manuel shrieked in terror. The injured boy moaned and twisted his head, looking left and right with wide staring eyes, and then he explosively vomited blood. He went immediately into convulsions, his body vibrating, and Bobbie grabbed for him but he shuddered off the table onto the concrete floor. He vomited again. There was blood everywhere. Ed opened the door, saying, “What the hell’s happening?” and when he saw the blood he turned away, his hand to his mouth. Bobbie was grabbing for a stick to put in the boy’s clenched jaws, but even as she did it she knew it was hopeless, and with a final spastic jerk he relaxed and lay still.

She bent to perform mouth-to-mouth, but Manuel grabbed her shoulder fiercely, pulling her back. “No,” he said. “The hupia will cross over.”

“Manuel, for God’s sake—”

“No.” He stared at her fiercely. “No. You do not understand these things.”

Bobbie looked at the body on the ground and realized that it didn’t matter; there was no possibility of resuscitating him. Manuel called for the men, who came back into the room and took the body away. Ed appeared, wiping his mouth with the back of his hand, muttering, “I’m sure you did all you could,” and then she watched as the men took the body away, back to the helicopter, and it lifted thunderously up into the sky.

“It is better,” Manuel said.

Bobbie was thinking about the boy’s hands. They had been covered with cuts and bruises, in the characteristic pattern of defense wounds. She was quite sure he had not died in a construction accident; he had been attacked, and he had held up his hands against his attacker. “Where is this island they’ve come from?” she asked.

“In the ocean. Perhaps a hundred, hundred and twenty miles offshore.”

“Pretty far for a resort,” she said.

Manuel watched the helicopter. “I hope they never come back.”

Well, she thought, at least she had pictures. But when she turned back to the table, she saw that her camera was gone.

The rain finally stopped later that night. Alone in the bedroom behind the clinic, Bobbie thumbed through her tattered paperback Spanish dictionary. The boy had said “raptor,” and, despite Manuel’s protests, she suspected it was a Spanish word. Sure enough, she found it in her dictionary. It meant “ravisher” or “abductor.”

That gave her pause. The sense of the word was suspiciously close to the meaning of hupia. Of course she did not believe in the superstition. And no ghost had cut those hands. What had the boy been trying to tell her?

From the next room, she heard groans. One of the village women was in the first stage of labor, and Elena Morales, the local midwife, was attending her. Bobbie went into the clinic room and gestured to Elena to step outside for a moment.

“Elena …”

“Sí, doctor?”

“Do you know what is a raptor?”

Elena was gray-haired and sixty, a strong woman with a practical, no-nonsense air. In the night, beneath the stars, she frowned and said, “Raptor?”

“Yes. You know this word?”

“Sí.” Elena nodded. “It means … a person who comes in the night and takes away a child.”

“A kidnapper?”

“Yes.”

“A hupia?”

Her whole manner changed. “Do not say this word, doctor.”

“Why not?”

“Do not speak of hupia now,” Elena said firmly, nodding her head toward the groans of the laboring woman. “It is not wise to say this word now.”

“But does a raptor bite and cut his victims?”

“Bite and cut?” Elena said, puzzled. “No, doctor. Nothing like this. A raptor is a man who takes a new baby.” She seemed irritated by the conversation, impatient to end it. Elena started back toward the clinic. “I will call to you when she is ready, doctor. I think one hour more, perhaps two.”

Bobbie looked at the stars, and listened to the peaceful lapping of the surf at the shore. In the darkness she saw the shadows of the fishing boats anchored offshore. The whole scene was quiet, so normal, she felt foolish to be talking of vampires and kidnapped babies.

Bobbie went back to her room, remembering again that Manuel had insisted it was not a Spanish word. Out of curiosity, she looked in the little English dictionary, and to her surprise she found the word there, too:

raptor\n [deriv. of L. raptor plunderer, fr. raptus]: bird of prey.

FIRST ITERATION

IAN MALCOLM

ALMOST PARADISE

Mike Bowman whistled cheerfully as he drove the Land Rover through the Cabo Blanco Biological Reserve, on the west coast of Costa Rica. It was a beautiful morning in July, and the road before him was spectacular: hugging the edge of a cliff, overlooking the jungle and the blue Pacific. According to the guidebooks, Cabo Blanco was unspoiled wilderness, almost a paradise. Seeing it now made Bowman feel as if the vacation was back on track.

Bowman, a thirty-six-year-old real estate developer from Dallas, had come to Costa Rica with his wife and daughter for a two-week holiday. The trip had actually been his wife’s idea; for weeks Ellen had filled his ear about the wonderful national parks of Costa Rica, and how good it would be for Tina to see them. Then, when they arrived, it turned out Ellen had an appointment to see a plastic surgeon in San José. That was the first Mike Bowman had heard about the excellent and inexpensive plastic surgery available in Costa Rica, and all the luxurious private clinics in San José.

Of course they’d had a huge fight. Mike felt she’d lied to him, and she had. And he put his foot down about this plastic surgery business. Anyway, it was ridiculous, Ellen was only thirty, and she was a beautiful woman. Hell, she’d been Homecoming Queen her senior year at Rice, and that was not even ten years earlier. But Ellen tended to be insecure, and worried. And it seemed as if in recent years she had mostly worried about losing her looks.

That, and everything else.

The Land Rover bounced in a pothole, splashing mud. Seated beside him, Ellen said, “Mike, are you sure this is the right road? We haven’t seen any other people for hours.”

“There was another car fifteen minutes ago,” he reminded her. “Remember, the blue one?”

“Going the other way …”

“Darling, you wanted a deserted beach,” he said, “and that’s what you’re going to get.”

Ellen shook her head doubtfully. “I hope you’re right.”

“Yeah, Dad, I hope you’re right,” said Christina, from the backseat. She was eight years old.

“Trust me, I’m right.” He drove in silence a moment. “It’s beautiful, isn’t it? Look at that view. It’s beautiful.”

“It’s okay,” Tina said.

Ellen got out a compact and looked at herself in the mirror, pressing under her eyes. She sighed, and put the compact away.

The road began to descend, and Mike Bowman concentrated on driving. Suddenly a small black shape flashed across the road and Tina shrieked, “Look! Look!” Then it was gone, into the jungle.

“What was it?” Ellen asked. “A monkey?”

“Maybe a squirrel monkey,” Bowman said.

“Can I count it?” Tina said, taking her pencil out. She was keeping a list of all the animals she had seen on her trip, as a project for school.

“I don’t know,” Mike said doubtfully.

Tina consulted the pictures in the guidebook. “I don’t think it was a squirrel monkey,” she said. “I think it was just another howler.” They had seen several howler monkeys already on their trip.

“Hey,” she said, more brightly. “According to this book, ‘the beaches of Cabo Blanco are frequented by a variety of wildlife, including howler and white-faced monkeys, three-toed sloths, and coatimundis.’ You think we’ll see a three-toed sloth, Dad?”

“I bet we do.”

“Really?”

“Just look in the mirror.”

“Very funny, Dad.”

The road sloped downward through the jungle, toward the ocean.

Mike Bowman felt like a hero when they finally reached the beach: a two-mile crescent of white sand, utterly deserted. He parked the Land Rover in the shade of the palm trees that fringed the beach, and got out the box lunches. Ellen changed into her bathing suit, saying, “Honestly, I don’t know how I’m going to get this weight off.”

“You look great, hon.” Actually, he felt that she was too thin, but he had learned not to mention that.

Tina was already running down the beach.

“Don’t forget you need your sunscreen,” Ellen called.

“Later,” Tina shouted, over her shoulder. “I’m going to see if there’s a sloth.”

Ellen Bowman looked around at the beach, and the trees. “You think she’s all right?”

“Honey, there’s nobody here for miles,” Mike said.

“What about snakes?”

“Oh, for God’s sake,” Mike Bowman said. “There’s no snakes on a beach.”

“Well, there might be.…”

“Honey,” he said firmly. “Snakes are cold-blooded. They’re reptiles. They can’t control their body temperature. It’s ninety degrees on that sand. If a snake came out, it’d be cooked. Believe me. There’s no snakes on the beach.” He watched his daughter scampering down the beach, a dark spot on the white sand. “Let her go. Let her have a good time.”

He put his arm around his wife’s waist.

Tina ran until she was exhausted, and then she threw herself down on the sand and gleefully rolled to the water’s edge. The ocean was warm, and there was hardly any surf at all. She sat for a while, catching her breath, and then she looked back toward her parents and the car, to see how far she had come.

Her mother waved, beckoning her to return. Tina waved back cheerfully, pretending she didn’t understand. Tina didn’t want to put sunscreen on. And she didn’t want to go back and hear her mother talk about losing weight. She wanted to stay right here, and maybe see a sloth.

Tina had seen a sloth two days earlier at the zoo in San José. It looked like a Muppets character, and it seemed harmless. In any case, it couldn’t move fast; she could easily outrun it.

Now her mother was calling to her, and Tina decided to move out of the sun, back from the water, to the shade of the palm trees. In this part of the beach, the palm trees overhung a gnarled tangle of mangrove roots, which blocked any attempt to penetrate inland. Tina sat in the sand and kicked the dried mangrove leaves. She noticed many bird tracks in the sand. Costa Rica was famous for its birds. The guidebooks said there were three times as many birds in Costa Rica as in all of America and Canada.

In the sand, some of the three-toed bird tracks were small, and so faint they could hardly be seen. Other tracks were large, and cut deeper in the sand. Tina was looking idly at the tracks when she heard a chirping, followed by a rustling in the mangrove thicket.

Did sloths make a chirping sound? Tina didn’t think so, but she wasn’t sure. The chirping was probably some ocean bird. She waited quietly, not moving, hearing the rustling again, and finally she saw the source of the sounds. A few yards away, a lizard emerged from the mangrove roots and peered at her.

Tina held her breath. A new animal for her list! The lizard stood up on its hind legs, balancing on its thick tail, and stared at her. Standing like that, it was almost a foot tall, dark green with brown stripes along its back. Its tiny front legs ended in little lizard fingers that wiggled in the air. The lizard cocked its head as it looked at her.

Tina thought it was cute. Sort of like a big salamander. She raised her hand and wiggled her fingers back.

The lizard wasn’t frightened. It came toward her, walking upright on its hind legs. It was hardly bigger than a chicken, and like a chicken it bobbed its head as it walked. Tina thought it would make a wonderful pet.

She noticed that the lizard left three-toed tracks that looked exactly like bird tracks. The lizard came closer to Tina. She kept her body still, not wanting to frighten the little animal. She was amazed that it would come so close, but she remembered that this was a national park. All the animals in the park would know that they were protected. This lizard was probably tame. Maybe it even expected her to give it some food. Unfortunately she didn’t have any. Slowly, Tina extended her hand, palm open, to show she didn’t have any food.

The lizard paused, cocked his head, and chirped.

“Sorry,” Tina said. “I just don’t have anything.”

And then, without warning, the lizard jumped up onto her outstretched hand. Tina could feel its little toes pinching the skin of her palm, and she felt the surprising weight of the animal’s body pressing her arm down.

And then the lizard scrambled up her arm, toward her face.

* * *

“I just wish I could see her,” Ellen Bowman said, squinting in the sunlight. “That’s all. Just see her.”

“I’m sure she’s fine,” Mike said, picking through the box lunch packed by the hotel. There was unappetizing grilled chicken, and some kind of a meat-filled pastry. Not that Ellen would eat any of it.

“You don’t think she’d leave the beach?” Ellen said.

“No, hon, I don’t.”

“I feel so isolated here,” Ellen said.

“I thought that’s what you wanted,” Mike Bowman said.

“I did.”

“Well, then, what’s the problem?”

“I just wish I could see her, is all,” Ellen said.

Then, from down the beach, carried by the wind, they heard their daughter’s voice. She was screaming.

PUNTARENAS

“I think she is quite comfortable now,” Dr. Cruz said, lowering the plastic flap of the oxygen tent around Tina as she slept. Mike Bowman sat beside the bed, close to his daughter. Mike thought Dr. Cruz was probably pretty capable; he spoke excellent English, the result of training at medical centers in London and Baltimore. Dr. Cruz radiated competence, and the Clínica Santa María, the modern hospital in Puntarenas, was spotless and efficient.

But, even so, Mike Bowman felt nervous. There was no getting around the fact that his only daughter was desperately ill, and they were far from home.

When Mike had first reached Tina, she was screaming hysterically. Her whole left arm was bloody, covered with a profusion of small bites, each the size of a thumbprint. And there were flecks of sticky foam on her arm, like a foamy saliva.

He carried her back down the beach. Almost immediately her arm began to redden and swell. Mike would not soon forget the frantic drive back to civilization, the four-wheel-drive Land Rover slipping and sliding up the muddy track into the hills, while his daughter screamed in fear and pain, and her arm grew more bloated and red. Long before they reached the park boundaries, the swelling had spread to her neck, and then Tina began to have trouble breathing.…

“She’ll be all right now?” Ellen said, staring through the plastic oxygen tent.

“I believe so,” Dr. Cruz said. “I have given her another dose of steroids, and her breathing is much easier. And you can see the edema in her arm is greatly reduced.”

Mike Bowman said, “About those bites …”

“We have no identification yet,” the doctor said. “I myself haven’t seen bites like that before. But you’ll notice they are disappearing. It’s already quite difficult to make them out. Fortunately I have taken photographs for reference. And I have washed her arm to collect some samples of the sticky saliva—one for analysis here, a second to send to the labs in San José, and the third we will keep frozen in case it is needed. Do you have the picture she made?”

“Yes,” Mike Bowman said. He handed the doctor the sketch that Tina had drawn, in response to questions from the admitting officials.

“This is the animal that bit her?” Dr. Cruz said, looking at the picture.

“Yes,” Mike Bowman said. “She said it was a green lizard, the size of a chicken or a crow.”

“I don’t know of such a lizard,” the doctor said. “She has drawn it standing on its hind legs.…”

“That’s right,” Mike Bowman said. “She said it walked on its hind legs.”

Dr. Cruz frowned. He stared at the picture a while longer. “I am not an expert. I’ve asked for Dr. Guitierrez to visit us here. He is a senior researcher at the Reserva Biológica de Carara, which is across the bay. Perhaps he can identify the animal for us.”

“Isn’t there someone from Cabo Blanco?” Bowman asked. “That’s where she was bitten.”

“Unfortunately not,” Dr. Cruz said. “Cabo Blanco has no permanent staff, and no researcher has worked there for some time. You were probably the first people to walk on that beach in several months. But I am sure you will find Dr. Guitierrez to be knowledgeable.”

Dr. Guitierrez turned out to be a bearded man wearing khaki shorts and shirt. The surprise was that he was American. He was introduced to the Bowmans, saying in a soft Southern accent, “Mr. and Mrs. Bowman, how you doing, nice to meet you,” and then explaining that he was a field biologist from Yale who had worked in Costa Rica for the last five years. Marty Guitierrez examined Tina thoroughly, lifting her arm gently, peering closely at each of the bites with a penlight, then measuring them with a small pocket ruler. After a while, Guitierrez stepped away, nodding to himself as if he had understood something. He then inspected the Polaroids, and asked several questions about the saliva, which Cruz told him was still being tested in the lab.

Finally he turned to Mike Bowman and his wife, waiting tensely. “I think Tina’s going to be fine. I just want to be clear about a few details,” he said, making notes in a precise hand. “Your daughter says she was bitten by a green lizard, approximately one foot high, which walked upright onto the beach from the mangrove swamp?”

“That’s right, yes.”

“And the lizard made some kind of a vocalization?”

“Tina said it chirped, or squeaked.”

“Like a mouse, would you say?”

“Yes.”

“Well, then,” Dr. Guitierrez said, “I know this lizard.” He explained that, of the six thousand species of lizards in the world, no more than a dozen species walked upright. Of those species, only four were found in Latin America. And judging by the coloration, the lizard could be only one of the four. “I am sure this lizard was a Basiliscus amoratus, a striped basilisk lizard, found here in Costa Rica and also in Honduras. Standing on their hind legs, they are sometimes as tall as a foot.”

“Are they poisonous?”

“No, Mrs. Bowman. Not at all.” Guitierrez explained that the swelling in Tina’s arm was an allergic reaction. “According to the literature, fourteen percent of people are strongly allergic to reptiles,” he said, “and your daughter seems to be one of them.”

“She was screaming, she said it was so painful.”

“Probably it was,” Guitierrez said. “Reptile saliva contains serotonin, which causes tremendous pain.” He turned to Cruz. “Her blood pressure came down with antihistamines?”

“Yes,” Cruz said. “Promptly.”

“Serotonin,” Guitierrez said. “No question.”

Still, Ellen Bowman remained uneasy. “But why would a lizard bite her in the first place?”

“Lizard bites are very common,” Guitierrez said. “Animal handlers in zoos get bitten all the time. And just the other day I heard that a lizard had bitten an infant in her crib in Amaloya, about sixty miles from where you were. So bites do occur. I’m not sure why your daughter had so many bites. What was she doing at the time?”

“Nothing. She said she was sitting pretty still, because she didn’t want to frighten it away.”

“Sitting pretty still,” Guitierrez said, frowning. He shook his head. “Well. I don’t think we can say exactly what happened. Wild animals are unpredictable.”

“And what about the foamy saliva on her arm?” Ellen said. “I keep thinking about rabies.…”

“No, no,” Dr. Guitierrez said. “A reptile can’t carry rabies, Mrs. Bowman. Your daughter has suffered an allergic reaction to the bite of a basilisk lizard. Nothing more serious.”

Mike Bowman then showed Guitierrez the picture that Tina had drawn. Guitierrez nodded. “I would accept this as a picture of a basilisk lizard,” he said. “A few details are wrong, of course. The neck is much too long, and she has drawn the hind legs with only three toes instead of five. The tail is too thick, and raised too high. But otherwise this is a perfectly serviceable lizard of the kind we are talking about.”

“But Tina specifically said the neck was long,” Ellen Bowman insisted. “And she said there were three toes on the foot.”

“Tina’s pretty observant,” Mike Bowman said.

“I’m sure she is,” Guitierrez said, smiling. “But I still think your daughter was bitten by a common basilisk amoratus, and had a severe herpetological reaction. Normal time course with medication is twelve hours. She should be just fine in the morning.”

In the modern laboratory in the basement of the Clínica Santa María, word was received that Dr. Guitierrez had identified the animal that had bitten the American child as a harmless basilisk lizard. Immediately the analysis of the saliva was halted, even though a preliminary fractionation showed several extremely high molecular weight proteins of unknown biological activity. But the night technician was busy, and he placed the saliva samples on the holding shelf of the refrigerator.

The next morning, the day clerk checked the holding shelf against the names of discharged patients. Seeing that BOWMAN, CHRISTINA L. was scheduled for discharge that morning, the clerk threw out the saliva samples. At the last moment, he noticed that one sample had the red tag which meant that it was to be forwarded to the university lab in San José. He retrieved the test tube from the wastebasket, and sent it on its way.

“Go on. Say thank you to Dr. Cruz,” Ellen Bowman said, and pushed Tina forward.

“Thank you, Dr. Cruz,” Tina said. “I feel much better now.” She reached up and shook the doctor’s hand. Then she said, “You have a different shirt.”

For a moment Dr. Cruz looked perplexed; then he smiled. “That’s right, Tina. When I work all night at the hospital, in the morning I change my shirt.”

“But not your tie?”

“No. Just my shirt.”

Ellen Bowman said, “Mike told you she’s observant.”

“She certainly is.” Dr. Cruz smiled and shook the little girl’s hand gravely. “Enjoy the rest of your holiday in Costa Rica, Tina.”

“I will.”

The Bowman family had started to leave when Dr. Cruz said, “Oh, Tina, do you remember the lizard that bit you?”

“Uh-huh.”

“You remember its feet?”

“Uh-huh.”

“Did it have any toes?”

“Yes.”

“How many toes did it have?”

“Three,” she said.

“How do you know that?”

“Because I looked,” she said. “Anyway, all the birds on the beach made marks in the sand with three toes, like this.” She held up her hand, middle three fingers spread wide. “And the lizard made those kind of marks in the sand, too.”

“The lizard made marks like a bird?”

“Uh-huh,” Tina said. “He walked like a bird, too. He jerked his head like this, up and down.” She took a few steps, bobbing her head.

After the Bowmans had departed, Dr. Cruz decided to report this conversation to Guitierrez, at the biological station.

“I must admit the girl’s story is puzzling,” Guitierrez said. “I have been doing some checking myself. I am no longer certain she was bitten by a basilisk. Not certain at all.”

“Then what could it be?”

“Well,” Guitierrez said, “let’s not speculate prematurely. By the way, have you heard of any other lizard bites at the hospital?”

“No, why?”

“Let me know, my friend, if you do.”

THE BEACH

Marty Guitierrez sat on the beach and watched the afternoon sun fall lower in the sky, until it sparkled harshly on the water of the bay, and its rays reached beneath the palm trees, to where he sat among the mangroves, on the beach of Cabo Blanco. As best he could determine, he was sitting near the spot where the American girl had been, two days before.

Although it was true enough, as he had told the Bowmans, that lizard bites were common, Guitierrez had never heard of a basilisk lizard biting anyone. And he had certainly never heard of anyone being hospitalized for a lizard bite. Then, too, the bite radius on Tina’s arm appeared slightly too large for a basilisk. When he got back to the Carara station, he had checked the small research library there, but found no reference to basilisk lizard bites. Next he checked International BioSciences Services, a computer database in America. But he found no references to basilisk bites, or hospitalization for lizard bites.

He then called the medical officer in Amaloya, who confirmed that a nine-day-old infant, sleeping in its crib, had been bitten on the foot by an animal the grandmother—the only person actually to see it—claimed was a lizard. Subsequently the foot had become swollen and the infant had nearly died. The grandmother described the lizard as green with brown stripes. It had bitten the child several times before the woman frightened it away.

“Strange,” Guitierrez had said.

“No, like all the others,” the medical officer replied, adding that he had heard of other biting incidents: A child in Vásquez, the next village up the coast, had been bitten while sleeping. And another in Puerta Sotrero. All these incidents had occurred in the last two months. All had involved sleeping children and infants.

Such a new and distinctive pattern led Guitierrez to suspect the presence of a previously unknown species of lizard. This was particularly likely to happen in Costa Rica. Only seventy-five miles wide at its narrowest point, the country was smaller than the state of Maine. Yet, within its limited space, Costa Rica had a remarkable diversity of biological habitats: seacoasts on both the Atlantic and the Pacific; four separate mountain ranges, including twelve-thousand-foot peaks and active volcanoes; rain forests, cloud forests, temperate zones, swampy marshes, and arid deserts. Such ecological diversity sustained an astonishing diversity of plant and animal life. Costa Rica had three times as many species of birds as all of North America. More than a thousand species of orchids. More than five thousand species of insects.

New species were being discovered all the time at a pace that had increased in recent years, for a sad reason. Costa Rica was becoming deforested, and as jungle species lost their habitats, they moved to other areas, and sometimes changed behavior as well.

So a new species was perfectly possible. But along with the excitement of a new species was the worrisome possibility of new diseases. Lizards carried viral diseases, including several that could be transmitted to man. The most serious was central saurian encephalitis, or CSE, which caused a form of sleeping sickness in human beings and horses. Guitierrez felt it was important to find this new lizard, if only to test it for disease.

Sitting on the beach, he watched the sun drop lower, and sighed. Perhaps Tina Bowman had seen a new animal, and perhaps not. Certainly Guitierrez had not. Earlier that morning, he had taken the air pistol, loaded the clip with ligamine darts, and set out for the beach with high hopes. But the day was wasted. Soon he would have to begin the drive back up the hill from the beach; he did not want to drive that road in darkness.

Guitierrez got to his feet and started back up the beach. Farther along, he saw the dark shape of a howler monkey, ambling along the edge of the mangrove swamp. Guitierrez moved away, stepping out toward the water. If there was one howler, there would probably be others in the trees overhead, and howlers tended to urinate on intruders.

But this particular howler monkey seemed to be alone, and walking slowly, and pausing frequently to sit on its haunches. The monkey had something in its mouth. As Guitierrez came closer, he saw it was eating a lizard. The tail and the hind legs drooped from the monkey’s jaws. Even from a distance, Guitierrez could see the brown stripes against the green.

Guitierrez dropped to the ground and aimed the pistol. The howler monkey, accustomed to living in a protected reserve, stared curiously. He did not run away, even when the first dart whined harmlessly past him. When the second dart struck deep in the thigh, the howler shrieked in anger and surprise, dropping the remains of its meal as it fled into the jungle.

Guitierrez got to his feet and walked forward. He wasn’t worried about the monkey; the tranquilizer dose was too small to give it anything but a few minutes of dizziness. Already he was thinking of what to do with his new find. Guitierrez himself would write the preliminary report, but the remains would have to be sent back to the United States for final positive identification, of course. To whom should he send it? The acknowledged expert was Edward H. Simpson, emeritus professor of zoology at Columbia University, in New York. An elegant older man with swept-back white hair, Simpson was the world’s leading authority on lizard taxonomy. Probably, Marty thought, he would send his lizard to Dr. Simpson.

NEW YORK

Dr. Richard Stone, head of the Tropical Diseases Laboratory of Columbia University Medical Center, often remarked that the name conjured up a grander place than it actually was. In the early twentieth century, when the laboratory occupied the entire fourth floor of the Biomedical Research Building, crews of technicians worked to eliminate the scourges of yellow fever, malaria, and cholera. But medical successes—and research laboratories in Nairobi and Sao Paulo—had left the TDL a much less important place than it once was. Now a fraction of its former size, it employed only two full-time technicians, and they were primarily concerned with diagnosing illnesses of New Yorkers who had traveled abroad. The lab’s comfortable routine was unprepared for what it received that morning.

“Oh, very nice,” the technician in the Tropical Diseases Laboratory said, as she read the customs label. “Partially masticated fragment of unidentified Costa Rican lizard.” She wrinkled her nose. “This one’s all yours, Dr. Stone.”

Richard Stone crossed the lab to inspect the new arrival. “Is this the material from Ed Simpson’s lab?”

“Yes,” she said. “But I don’t know why they’d send a lizard to us.”

“His secretary called,” Stone said. “Simpson’s on a field trip in Borneo for the summer, and because there’s a question of communicable disease with this lizard, she asked our lab to take a look at it. Let’s see what we’ve got.”

The white plastic cylinder was the size of a half-gallon milk container. It had locking metal latches and a screw top. It was labeled “International Biological Specimen Container” and plastered with stickers and warnings in four languages. The warnings were intended to keep the cylinder from being opened by suspicious customs officials.

Apparently the warnings had worked; as Richard Stone swung the big light over, he could see the seals were still intact. Stone turned on the air handlers and pulled on plastic gloves and a face mask. After all, the lab had recently identified specimens contaminated with Venezuelan equine fever, Japanese B encephalitis, Kyasanur Forest virus, Langat virus, and Mayaro. Then he unscrewed the top.

There was the hiss of escaping gas, and white smoke boiled out. The cylinder turned frosty cold. Inside he found a plastic zip-lock sandwich bag, containing something green. Stone spread a surgical drape on the table and shook out the contents of the bag. A piece of frozen flesh struck the table with a dull thud.

“Huh,” the technician said. “Looks eaten.”

“Yes, it does,” Stone said. “What do they want with us?”

The technician consulted the enclosed documents. “Lizard is biting local children. They have a question about identification of the species, and a concern about diseases transmitted from the bite.” She produced a child’s picture of a lizard, signed TINA at the top. “One of the kids drew a picture of the lizard.”

Stone glanced at the picture. “Obviously we can’t verify the species,” Stone said. “But we can check diseases easily enough, if we can get any blood out of this fragment. What are they calling this animal?”

“ ‘Basiliscus amoratus with three-toed genetic anomaly,’ ” she said, reading.

“Okay,” Stone said. “Let’s get started. While you’re waiting for it to thaw, do an X ray and take Polaroids for the record. Once we have blood, start running antibody sets until we get some matches. Let me know if there’s a problem.”

Before lunchtime, the lab had its answer: the lizard blood showed no significant reactivity to any viral or bacterial antigen. They had run toxicity profiles as well, and they had found only one positive match: the blood was mildly reactive to the venom of the Indian king cobra. But such cross-reactivity was common among reptile species, and Dr. Stone did not think it noteworthy to include in the fax his technician sent to Dr. Martin Guitierrez that same evening.

There was never any question about identifying the lizard; that would await the return of Dr. Simpson. He was not due back for several weeks, and his secretary asked if the TDL would please store the lizard fragment in the meantime. Dr. Stone put it back in the zip-lock bag and stuck it in the freezer.

Martin Guitierrez read the fax from the Columbia Medical Center/ Tropical Diseases Laboratory. It was brief:

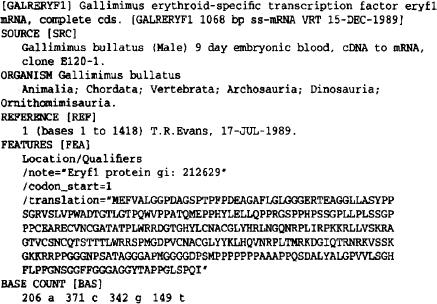

SUBJECT: Basiliscus amoratus with genetic anomaly (forwarded from Dr. Simpson’s office)

MATERIALS: posterior segment, ? partially eaten animal

PROCEDURES PERFORMED: X ray, microscopic, immunological RTX for viral, parasitic, bacterial disease.

FINDINGS: No histologic or immunologic evidence for any communicable disease in man in this Basiliscus amoratus sample.

(signed)

Richard A. Stone, M.D., director

Guitierrez made two assumptions based on the memo. First, that his identification of the lizard as a basilisk had been confirmed by scientists at Columbia University. And second, that the absence of communicable disease meant the recent episodes of sporadic lizard bites implied no serious health hazards for Costa Rica. On the contrary, he felt his original views were correct: that a lizard species had been driven from the forest into a new habitat, and was coming into contact with village people. Guitierrez was certain that in a few more weeks the lizards would settle down and the biting episodes would end.

The tropical rain fell in great drenching sheets, hammering the corrugated roof of the clinic in Bahía Anasco. It was nearly midnight; power had been lost in the storm, and the midwife Elena Morales was working by flashlight when she heard a squeaking, chirping sound. Thinking that it was a rat, she quickly put a compress on the forehead of the mother and went into the next room to check on the newborn baby. As her hand touched the doorknob, she heard the chirping again, and she relaxed. Evidently it was just a bird, flying in the window to get out of the rain. Costa Ricans said that when a bird came to visit a newborn child, it brought good luck.

Elena opened the door. The infant lay in a wicker bassinet, swaddled in a light blanket, only its face exposed. Around the rim of the bassinet, three dark green lizards crouched like gargoyles. When they saw Elena, they cocked their heads and stared curiously at her, but did not flee. In the light of her flashlight Elena saw the blood dripping from their snouts. Softly chirping, one lizard bent down and, with a quick shake of its head, tore a ragged chunk of flesh from the baby.

Elena rushed forward, screaming, and the lizards fled into the darkness. But long before she reached the bassinet, she could see what had happened to the infant’s face, and she knew the child must be dead. The lizards scattered into the rainy night, chirping and squealing, leaving behind only bloody three-toed tracks, like birds.

THE SHAPE OF THE DATA

Later, when she was calmer, Elena Morales decided not to report the lizard attack. Despite the horror she had seen, she began to worry that she might be criticized for leaving the baby unguarded. So she told the mother that the baby had asphyxiated, and she reported the death on the forms she sent to San José as SIDS: sudden infant death syndrome. This was a syndrome of unexplained death among very young children; it was unremarkable, and her report went unchallenged.

The university lab in San José that analyzed the saliva sample from Tina Bowman’s arm made several remarkable discoveries. There was, as expected, a great deal of serotonin. But among the salivary proteins was a real monster: molecular mass of 1,980,000, one of the largest proteins known. Biological activity was still under study, but it seemed to be a neurotoxic poison related to cobra venom, although more primitive in structure.

The lab also detected trace quantities of the gamma-amino methionine hydrolase. Because this enzyme was a marker for genetic engineering, and not found in wild animals, technicians assumed it was a lab contaminant and did not report it when they called Dr. Cruz, the referring physician in Puntarenas.

The lizard fragment rested in the freezer at Columbia University, awaiting the return of Dr. Simpson, who was not expected for at least a month. And so things might have remained, had not a technician named Alice Levin walked into the Tropical Diseases Laboratory, seen Tina Bowman’s picture, and said, “Oh, whose kid drew the dinosaur?”

“What?” Richard Stone said, turning slowly toward her.

“The dinosaur. Isn’t that what it is? My kid draws them all the time.”

“This is a lizard,” Stone said. “From Costa Rica. Some girl down there drew a picture of it.”

“No,” Alice Levin said, shaking her head. “Look at it. It’s very clear. Big head, long neck, stands on its hind legs, thick tail. It’s a dinosaur.”

“It can’t be. It was only a foot tall.”

“So? There were little dinosaurs back then,” Alice said. “Believe me, I know. I have two boys, I’m an expert. The smallest dinosaurs were under a foot. Teenysaurus or something, I don’t know. Those names are impossible. You’ll never learn those names if you’re over the age of ten.”

“You don’t understand,” Richard Stone said. “This is a picture of a contemporary animal. They sent us a fragment of the animal. It’s in the freezer now.” Stone went and got it, and shook it out of the baggie.

Alice Levin looked at the frozen piece of leg and tail, and shrugged. She didn’t touch it. “I don’t know,” she said. “But that looks like a dinosaur to me.”

Stone shook his head. “Impossible.”

“Why?” Alice Levin said. “It could be a leftover or a remnant or whatever they call them.”

Stone continued to shake his head. Alice was uninformed; she was just a technician who worked in the bacteriology lab down the hall. And she had an active imagination. Stone remembered the time when she thought she was being followed by one of the surgical orderlies.…

“You know,” Alice Levin said, “if this is a dinosaur, Richard, it could be a big deal.”

“It’s not a dinosaur.”

“Has anybody checked it?”

“No,” Stone said.

“Well, take it to the Museum of Natural History or something,” Alice Levin said. “You really should.”

“I’d be embarrassed.”

“You want me to do it for you?” she said.

“No,” Richard Stone said. “I don’t.”

“You’re not going to do anything?”

“Nothing at all.” He put the baggie back in the freezer and slammed the door. “It’s not a dinosaur, it’s a lizard. And whatever it is, it can wait until Dr. Simpson gets back from Borneo to identify it. That’s final, Alice. This lizard’s not going anywhere.”

SECOND ITERATION

IAN MALCOLM

THE SHORE OF THE INLAND

SEA

Alan Grant crouched down, his nose inches from the ground. The temperature was over a hundred degrees. His knees ached, despite the rug-layer’s pads he wore. His lungs burned from the harsh alkaline dust. Sweat dripped off his forehead onto the ground. But Grant was oblivious to the discomfort. His entire attention was focused on the six-inch square of earth in front of him.

Working patiently with a dental pick and an artist’s camel brush, he exposed the tiny L-shaped fragment of jawbone. It was only an inch long, and no thicker than his little finger. The teeth were a row of small points, and had the characteristic medial angling. Bits of bone flaked away as he dug. Grant paused for a moment to paint the bone with rubber cement before continuing to expose it. There was no question that this was the jawbone from an infant carnivorous dinosaur. Its owner had died seventy-nine million years ago, at the age of about two months. With any luck, Grant might find the rest of the skeleton as well. If so, it would be the first complete skeleton of a baby carnivore—

“Hey, Alan!”

Alan Grant looked up, blinking in the sunlight. He pulled down his sunglasses, and wiped his forehead with the back of his arm.

He was crouched on an eroded hillside in the badlands outside Snakewater, Montana. Beneath the great blue bowl of sky, blunted hills, exposed outcroppings of crumbling limestone, stretched for miles in every direction. There was not a tree, or a bush. Nothing but barren rock, hot sun, and whining wind.

Visitors found the badlands depressingly bleak, but when Grant looked at this landscape, he saw something else entirely. This barren land was what remained of another, very different world, which had vanished eighty million years ago. In his mind’s eye, Grant saw himself back in the warm, swampy bayou that formed the shoreline of a great inland sea. This inland sea was a thousand miles wide, extending all the way from the newly upthrust Rocky Mountains to the sharp, craggy peaks of the Appalachians. All of the American West was under water.

At that time, there were thin clouds in the sky overhead, darkened by the smoke of nearby volcanoes. The atmosphere was denser, richer in carbon dioxide. Plants grew rapidly along the shoreline. There were no fish in these waters, but there were clams and snails. Pterosaurs swooped down to scoop algae from the surface. A few carnivorous dinosaurs prowled the swampy shores of the lake, moving among the palm trees. And offshore was a small island, about two acres in size. Ringed with dense vegetation, this island formed a protected sanctuary where herds of herbivorous duckbilled dinosaurs laid their eggs in communal nests, and raised their squeaking young.

Over the millions of years that followed, the pale green alkaline lake grew shallower, and finally vanished. The exposed land buckled and cracked under the heat. And the offshore island with its dinosaur eggs became the eroded hillside in northern Montana which Alan Grant was now excavating.

“Hey, Alan!”

He stood, a barrel-chested, bearded man of forty. He heard the chugging of the portable generator, and the distant clatter of the jack-hammer cutting into the dense rock on the next hill. He saw the kids working around the jackhammer, moving away the big pieces of rock after checking them for fossils. At the foot of the hill, he saw the six tipis of his camp, the flapping mess tent, and the trailer that served as their field laboratory. And he saw Ellie waving to him, from the shadow of the field laboratory.

“Visitor!” she called, and pointed to the east.

Grant saw the cloud of dust, and the blue Ford sedan bouncing over the rutted road toward them. He glanced at his watch: right on time. On the other hill, the kids looked up with interest. They didn’t get many visitors in Snakewater, and there had been a lot of speculation about what a lawyer from the Environmental Protection Agency would want to see Alan Grant about.

But Grant knew that paleontology, the study of extinct life, had in recent years taken on an unexpected relevance to the modern world. The modern world was changing fast, and urgent questions about the weather, deforestation, global warming, or the ozone layer often seemed answerable, at least in part, with information from the past. Information that paleontologists could provide. He had been called as an expert witness twice in the past few years.

Grant started down the hill to meet the car.

The visitor coughed in the white dust as he slammed the car door. “Bob Morris, EPA,” he said, extending his hand. “I’m with the San Francisco office.”

Grant introduced himself and said, “You look hot. Want a beer?”

“Jesus, yeah.” Morris was in his late twenties, wearing a tie, and pants from a business suit. He carried a briefcase. His wing-tip shoes crunched on the rocks as they walked toward the trailer.

“When I first came over the hill, I thought this was an Indian reservation,” Morris said, pointing to the tipis.

“No,” Grant said. “Just the best way to live out here.” Grant explained that in 1978, the first year of the excavations, they had come out in North Slope octahedral tents, the most advanced available. But the tents always blew over in the wind. They tried other kinds of tents, with the same result. Finally they started putting up tipis, which were larger inside, more comfortable, and more stable in wind. “These’re Blackfoot tipis, built around four poles,” Grant said. “Sioux tipis are built around three. But this used to be Blackfoot territory, so we thought …”

“Uh-huh,” Morris said. “Very fitting.” He squinted at the desolate landscape and shook his head. “How long you been out here?”

“About sixty cases,” Grant said. When Morris looked surprised, he explained, “We measure time in beer. We start in June with a hundred cases. We’ve gone through about sixty so far.”

“Sixty-three, to be exact,” Ellie Sattler said, as they reached the trailer. Grant was amused to see Morris gaping at her. Ellie was wearing cut-off jeans and a workshirt tied at her midriff. She was twenty-four and darkly tanned. Her blond hair was pulled back.

“Ellie keeps us going,” Grant said, introducing her. “She’s very good at what she does.”

“What does she do?” Morris asked.

“Paleobotany,” Ellie said. “And I also do the standard field preps.” She opened the door and they went inside.

The air conditioning in the trailer only brought the temperature down to eighty-five degrees, but it seemed cool after the midday heat. The trailer had a series of long wooden tables, with tiny bone specimens neatly laid out, tagged and labeled. Farther along were ceramic dishes and crocks. There was a strong odor of vinegar.

Morris glanced at the bones. “I thought dinosaurs were big,” he said.

“They were,” Ellie said. “But everything you see here comes from babies. Snakewater is important primarily because of the number of dinosaur nesting sites here. Until we started this work, there were hardly any infant dinosaurs known. Only one nest had ever been found, in the Gobi Desert. We’ve discovered a dozen different hadrosaur nests, complete with eggs and bones of infants.”

While Grant went to the refrigerator, she showed Morris the acetic acid baths, which were used to dissolve away the limestone from the delicate bones.

“They look like chicken bones,” Morris said, peering into the ceramic dishes.

“Yes,” she said. “They’re very bird-like.”

“And what about those?” Morris said, pointing through the trailer window to piles of large bones outside, wrapped in heavy plastic.

“Rejects,” Ellie said. “Bones too fragmentary when we took them out of the ground. In the old days we’d just discard them, but nowadays we send them for genetic testing.”

“Genetic testing?” Morris said.

“Here you go,” Grant said, thrusting a beer into his hand. He gave another to Ellie. She chugged hers, throwing her long neck back. Morris stared.

“We’re pretty informal here,” Grant said. “Want to step into my office?”

“Sure,” Morris said. Grant led him to the end of the trailer, where there was a torn couch, a sagging chair, and a battered end table. Grant dropped onto the couch, which creaked and exhaled a cloud of chalky dust. He leaned back, thumped his boots up on the end table, and gestured for Morris to sit in the chair. “Make yourself comfortable.”

Grant was a professor of paleontology at the University of Denver, and one of the foremost researchers in his field, but he had never been comfortable with social niceties. He saw himself as an outdoor man, and he knew that all the important work in paleontology was done outdoors, with your hands. Grant had little patience for the academics, for the museum curators, for what he called Teacup Dinosaur Hunters. And he took some pains to distance himself in dress and behavior from the Teacup Dinosaur Hunters, even delivering his lectures in jeans and sneakers.

Grant watched as Morris primly brushed off the seat of the chair before he sat down. Morris opened his briefcase, rummaged through his papers, and glanced back at Ellie, who was lifting bones with tweezers from the acid bath at the other end of the trailer, paying no attention to them. “You’re probably wondering why I’m here.”

Grant nodded. “It’s a long way to come, Mr. Morris.”

“Well,” Morris said, “to get right to the point, the EPA is concerned about the activities of the Hammond Foundation. You receive some funding from them.”

“Thirty thousand dollars a year,” Grant said, nodding. “For the last five years.”

“What do you know about the foundation?” Morris said.

Grant shrugged. “The Hammond Foundation is a respected source of academic grants. They fund research all over the world, including several dinosaur researchers. I know they support Bob Kerry out of the Tyrrell in Alberta, and John Weller in Alaska. Probably more.”

“Do you know why the Hammond Foundation supports so much dinosaur research?” Morris asked.

“Of course. It’s because old John Hammond is a dinosaur nut.”

“You’ve met Hammond?”

Grant shrugged. “Once or twice. He comes here for brief visits. He’s quite elderly, you know. And eccentric, the way rich people sometimes are. But always very enthusiastic. Why?”

“Well,” Morris said, “the Hammond Foundation is actually a rather mysterious organization.” He pulled out a Xeroxed world map, marked with red dots, and passed it to Grant. “These are the digs the foundation financed last year. Notice anything odd about them? Montana, Alaska, Canada, Sweden … They’re all sites in the north. There’s nothing below the forty-fifth parallel.” Morris pulled out more maps. “It’s the same, year after year. Dinosaur projects to the south, in Utah or Colorado or Mexico, never get funded. The Hammond Foundation only supports cold-weather digs. We’d like to know why.”

Grant shuffled through the maps quickly. If it was true that the foundation only supported cold-weather digs, then it was strange behavior, because some of the best dinosaur researchers were working in hot climates, and—

“And there are other puzzles,” Morris said. “For example, what is the relationship of dinosaurs to amber?”

“Amber?”

“Yes. It’s the hard yellow resin of dried tree sap—”

“I know what it is,” Grant said. “But why are you asking?”

“Because,” Morris said, “over the last five years, Hammond has purchased enormous quantities of amber in America, Europe, and Asia, including many pieces of museum-quality jewelry. The foundation has spent seventeen million dollars on amber. They now possess the largest privately held stock of this material in the world.”

“I don’t get it,” Grant said.

“Neither does anybody else,” Morris said. “As far as we can tell, it doesn’t make any sense at all. Amber is easily synthesized. It has no commercial or defense value. There’s no reason to stockpile it. But Hammond has done just that, over many years.”

“Amber,” Grant said, shaking his head.

“And what about his island in Costa Rica?” Morris continued. “Ten years ago, the Hammond Foundation leased an island from the government of Costa Rica. Supposedly to set up a biological preserve.”

“I don’t know anything about that,” Grant said, frowning.

“I haven’t been able to find out much,” Morris said. “The island is a hundred miles off the west coast. It’s very rugged, and it’s in an area of ocean where the combinations of wind and current make it almost perpetually covered in fog. They used to call it Cloud Island. Isla Nublar. Apparently the Costa Ricans were amazed that anybody would want it.” Morris searched in his briefcase. “The reason I mention it,” he said, “is that, according to the records, you were paid a consultant’s fee in connection with this island.”

“I was?” Grant said.

Morris passed a sheet of paper to Grant. It was the Xerox of a check issued in March 1984 from InGen Inc., Farallon Road, Palo Alto, California. Made out to Alan Grant in the amount of twelve thousand dollars. At the lower corner, the check was marked CONSULTANT SERVICES/COSTA RICA/JUVENILE HYPERSPACE.

“Oh, sure,” Grant said. “I remember that. It was weird as hell, but I remember it. And it didn’t have anything to do with an island.”

Alan Grant had found the first clutch of dinosaur eggs in Montana in 1979, and many more in the next two years, but he hadn’t gotten around to publishing his findings until 1983. His paper, with its report of a herd of ten thousand duckbilled dinosaurs living along the shore of a vast inland sea, building communal nests of eggs in the mud, raising their infant dinosaurs in the herd, made Grant a celebrity overnight. The notion of maternal instincts in giant dinosaurs—and the drawings of cute babies poking their snouts out of the eggs—had appeal around the world. Grant was besieged with requests for interviews, lectures, books. Characteristically, he turned them all down, wanting only to continue his excavations. But it was during those frantic days of the mid-1980s that he was approached by the InGen corporation with a request for consulting services.

“Had you heard of InGen before?” Morris asked.

“No.”

“How did they contact you?”

“Telephone call. It was a man named Gennaro or Gennino, something like that.”

Morris nodded. “Donald Gennaro,” he said. “He’s the legal counsel for InGen.”

“Anyway, he wanted to know about eating habits of dinosaurs. And he offered me a fee to draw up a paper for him.” Grant drank his beer, set the can on the floor. “Gennaro was particularly interested in young dinosaurs. Infants and juveniles. What they ate. I guess he thought I would know about that.”

“Did you?”

“Not really, no. I told him that. We had found lots of skeletal material, but we had very little dietary data. But Gennaro said he knew we hadn’t published everything, and he wanted whatever we had. And he offered a very large fee. Fifty thousand dollars.”

Morris took out a tape recorder and set it on the endtable. “You mind?”

“No, go ahead.”

“So Gennaro telephoned you in 1984. What happened then?”

“Well,” Grant said. “You see our operation here. Fifty thousand would support two full summers of digging. I told him I’d do what I could.”

“So you agreed to prepare a paper for him.”

“Yes.”

“On the dietary habits of juvenile dinosaurs?”

“Yes.”

“You met Gennaro?”

“No. Just on the phone.”

“Did Gennaro say why he wanted this information?”

“Yes,” Grant said. “He was planning a museum for children, and he wanted to feature baby dinosaurs. He said he was hiring a number of academic consultants, and named them. There were paleontologists like me, and a mathematician from Texas named Ian Malcolm, and a couple of ecologists. A systems analyst. Good group.”

Morris nodded, making notes. “So you accepted the consultancy?”

“Yes. I agreed to send him a summary of our work: what we knew about the habits of the duckbilled hadrosaurs we’d found.”

“What kind of information did you send?” Morris asked.

“Everything: nesting behavior, territorial ranges, feeding behavior, social behavior. Everything.”

“And how did Gennaro respond?”

“He kept calling and calling. Sometimes in the middle of the night. Would the dinosaurs eat this? Would they eat that? Should the exhibit include this? I could never understand why he was so worked up. I mean, I think dinosaurs are important, too, but not that important. They’ve been dead sixty-five million years. You’d think his calls could wait until morning.”

“I see,” Morris said. “And the fifty thousand dollars?”

Grant shook his head. “I got tired of Gennaro and called the whole thing off. We settled up for twelve thousand. That must have been about the middle of ’85.”

Morris made a note. “And InGen? Any other contact with them?”

“Not since 1985.”

“And when did the Hammond Foundation begin to fund your research?”

“I’d have to look,” Grant said. “But it was around then. Mid-eighties.”

“And you know Hammond as just a rich dinosaur enthusiast.”

“Yes.”

Morris made another note.

“Look,” Grant said. “If the EPA is so concerned about John Hammond and what he’s doing—the dinosaur sites in the north, the amber purchases, the island in Costa Rica—why don’t you just ask him about it?”

“At the moment, we can’t,” Morris said.

“Why not?” Grant said.

“Because we don’t have any evidence of wrongdoing,” Morris said. “But personally, I think it’s clear John Hammond is evading the law.”