Michael D. Lemonick

The Bomb is in the Mail

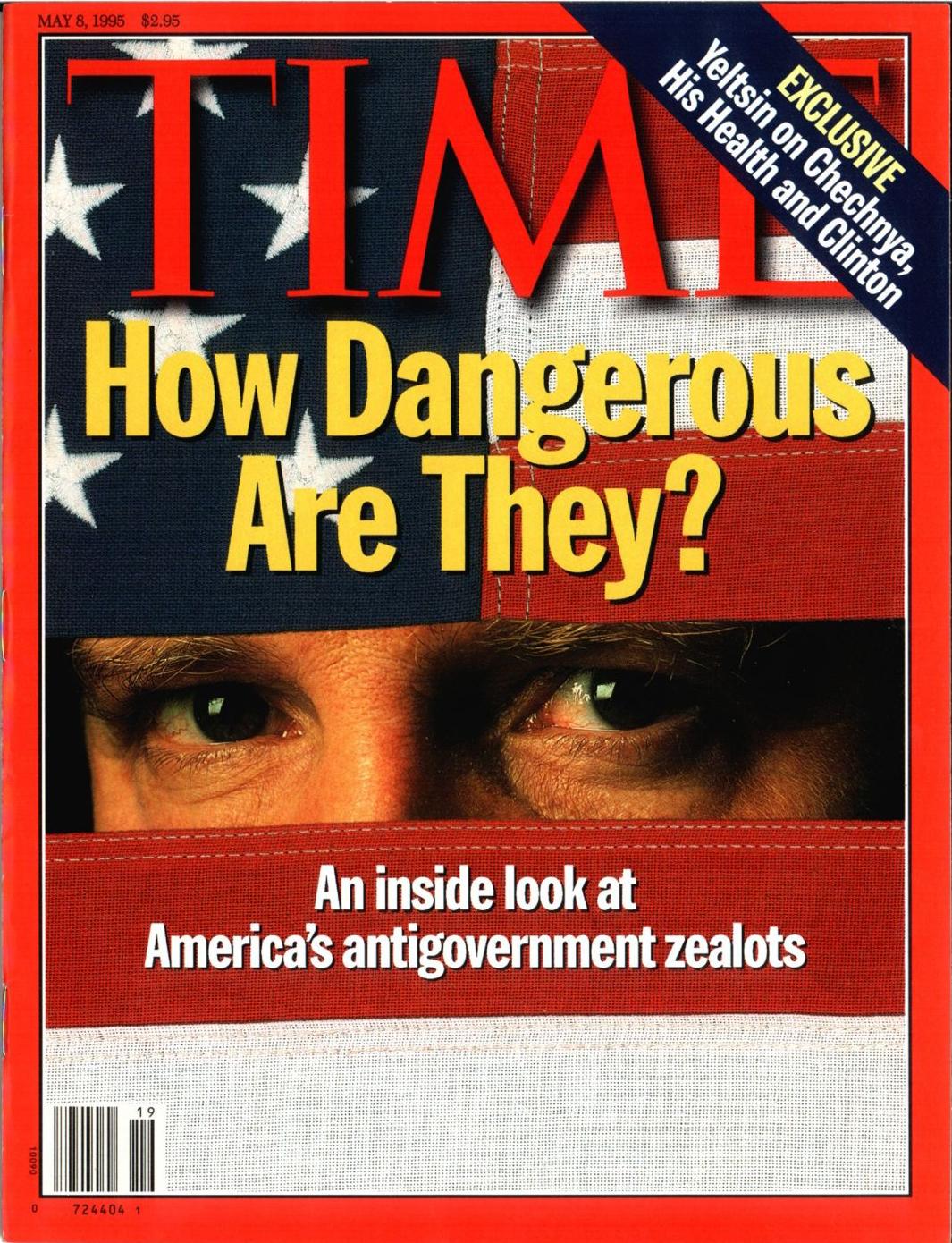

The Mysterious Unabomber Strikes Again. But for the First Time in 17 Years, He Wants to Explain Why

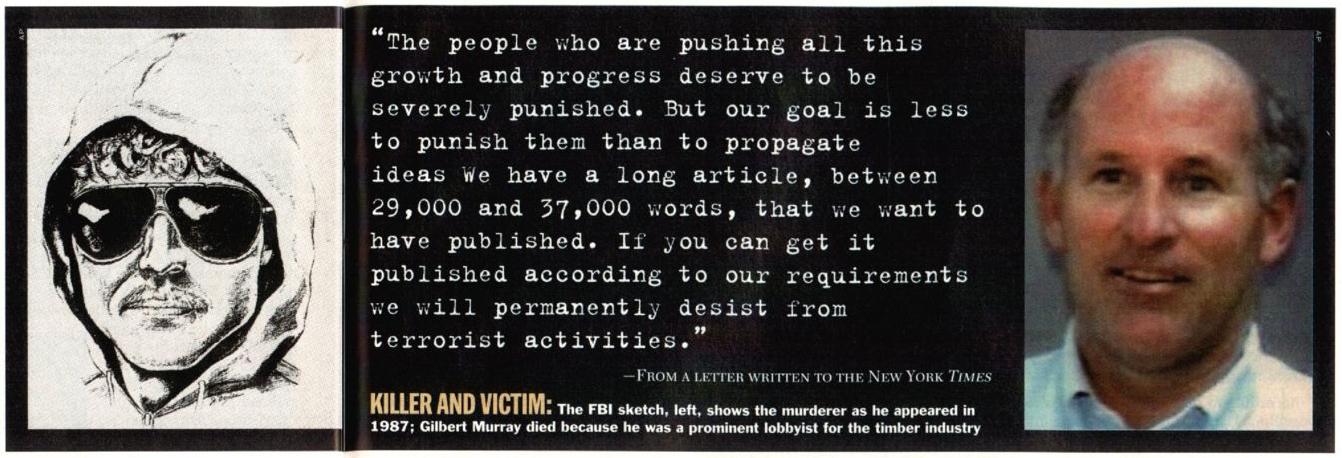

If the receptionist at the California Forestry Association office in Sacramento hadn't had so much trouble opening the shoebox-size package that arrived in the mail last Monday, she would now be dead. She survives only because she carried the box in to her boss, the organization's president, Gilbert Murray, and left it with him. He started to unwrap it-and the package blew up in his hands. The blast, which killed Murray,47, instantly, was powerful enough to knock two doors off their hinges and blow gashes into the ceiling panels. And it was loud enough to be heard for blocks around, sending hundreds of workers into the streets in fear and bewilderment. Their panic was easy to understand: the Oklahoma City bombing had taken place just five days earlier.

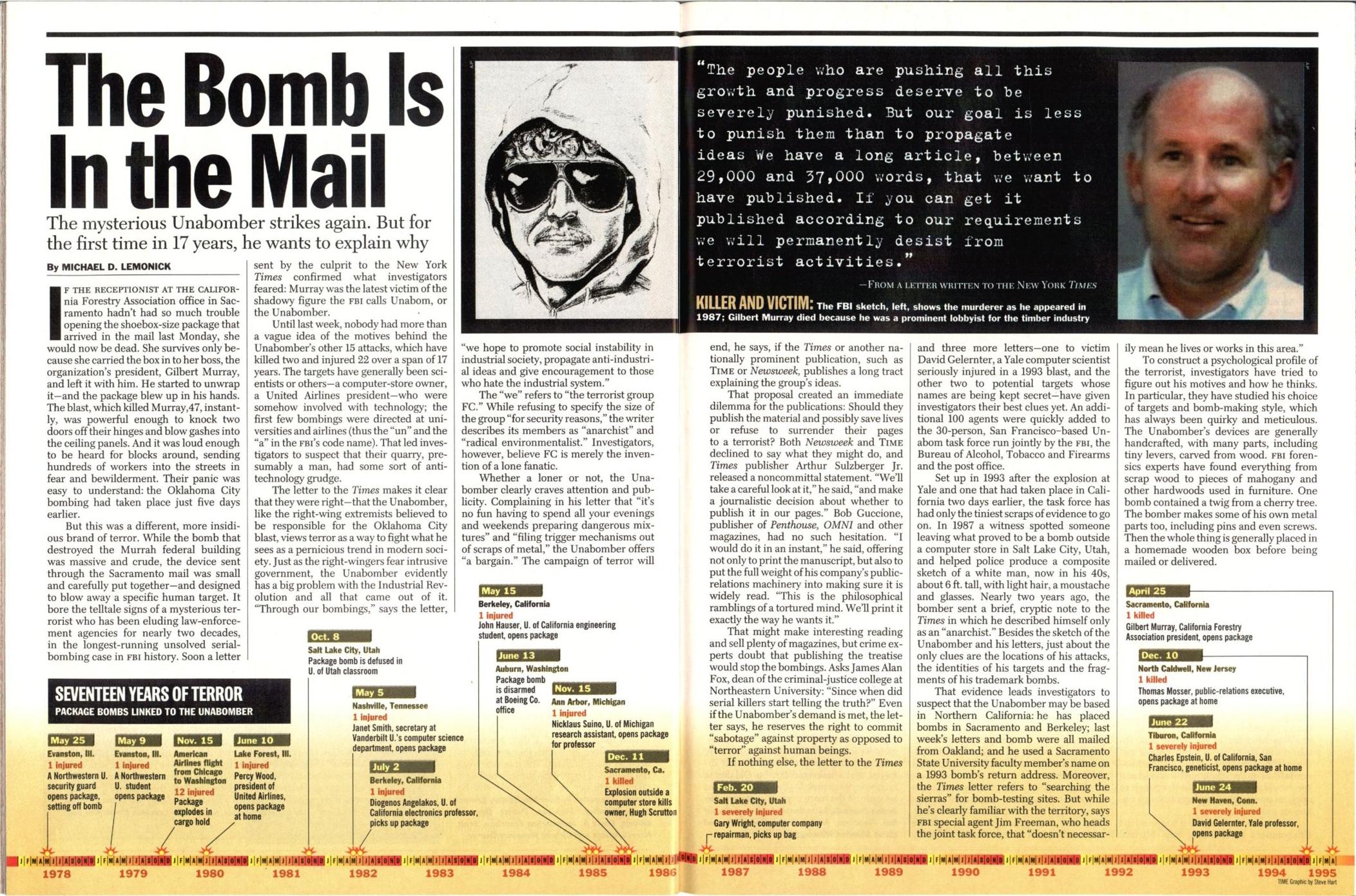

But this was a different, more insidious brand of terror. While the bomb that destroyed the Murrah federal building was massive and crude, the device sent through the Sacramento mail was small and carefully put together-and designed to blow away a specific human target. It bore the telltale signs of a mysterious terrorist who has been eluding law-enforcement agencies for nearly two decades, in the longest-running unsolved serial-bombing case in FBI history. Soon a letter sent by the culprit to the New York Times confirmed what investigators feared: Murray was the latest victim of the shadowy figure the FBI calls Unabom, or the Unabomber.

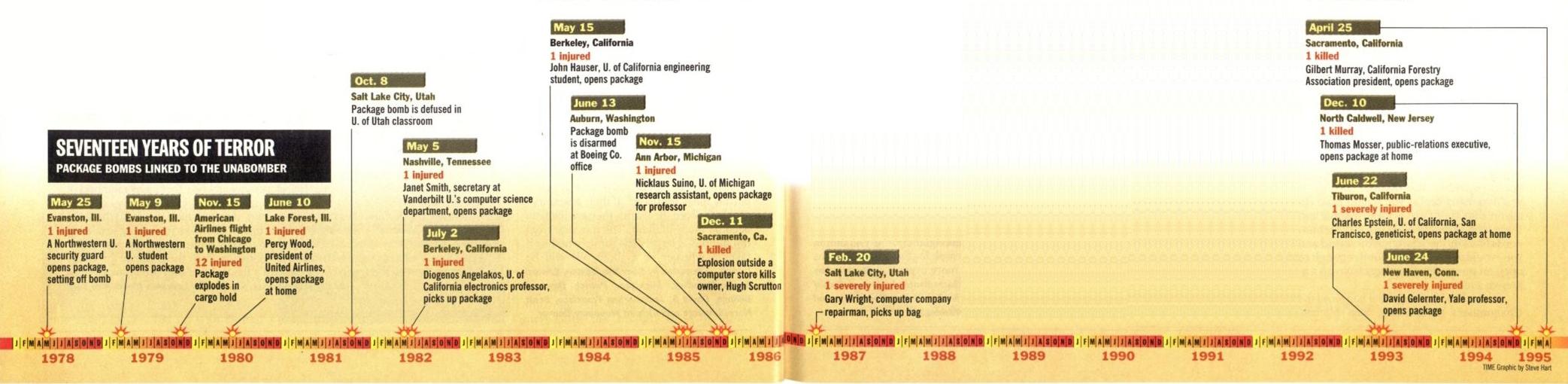

Until last week, nobody had more than a vague idea of the motives behind the Unabomber's other 15 attacks, which have killed two and injured 22 over a span of 17 years. The targets have generally been scientists or others -- a computer-store owner, a United Airlines president -- who were somehow involved with technology; the first few bombings were directed at universities and airlines (thus the "un" and the "a" in the FBI's code name). That led investigators to suspect that their quarry, presumably a man, had some sort of antitechnology grudge.

The letter to the Times makes it clear that they were right-that the Unabomber, like the right-wing extremists believed to be responsible for the Oklahoma City blast, views terror as a way to fight what he sees as a pernicious trend in modern society. Just as the right-wingers fear intrusive government, the Unabomber evidently has a big problem with the Industrial Revolution and all that came out of it. "Through our bombings," says the letter, "we hope to promote social instability in industrial society, propagate anti-industrial ideas and give encouragement to those who hate the industrial system."

The "we" refers to "the terrorist group FC." While refusing to specify the size of the group "for security reasons," the writer describes its members as "anarchist" and "radical environmentalist." Investigators, however, believe FC is merely the invention of a lone fanatic.

Whether a loner or not, the Unabomber clearly craves attention and publicity. Complaining in his letter that "it's no fun having to spend all your evenings and weekends preparing dangerous mixtures" and "filing trigger mechanisms out of scraps of metal," the Unabomber offers "a bargain." The campaign of terror will end, he says, if the Times or another nationally prominent publication, such as Time or Newsweek, publishes a long tract explaining the group's ideas.

That proposal created an immediate dilemma for the publications: Should they publish the material and possibly save lives or refuse to surrender their pages to a terrorist? Both Newsweek and TIME declined to say what they might do, and Times publisher Arthur Sulzberger Jr. released a noncommittal statement. "We'll take a careful look at it," he said, "and make a journalistic decision about whether to publish it in our pages." Bob Guccione, publisher of Penthouse, OMNI and other magazines, had no such hesitation. "I would do it in an instant," he said, offering not only to print the manuscript, but also to put the full weight of his company's public-relations machinery into making sure it is widely read. "This is the philosophical ramblings of a tortured mind. We'll print it exactly the way he wants it.''

That might make interesting reading and sell plenty of magazines, but crime experts doubt that publishing the treatise would stop the bombings. Asks James Alan Fox, dean of the criminal-justice college at Northeastern University: "Since when did serial killers start telling the truth?" Even if the Unabomber's demand is met, the letter says, he reserves the right to commit "sabotage" against property as opposed to "terror" against human beings.

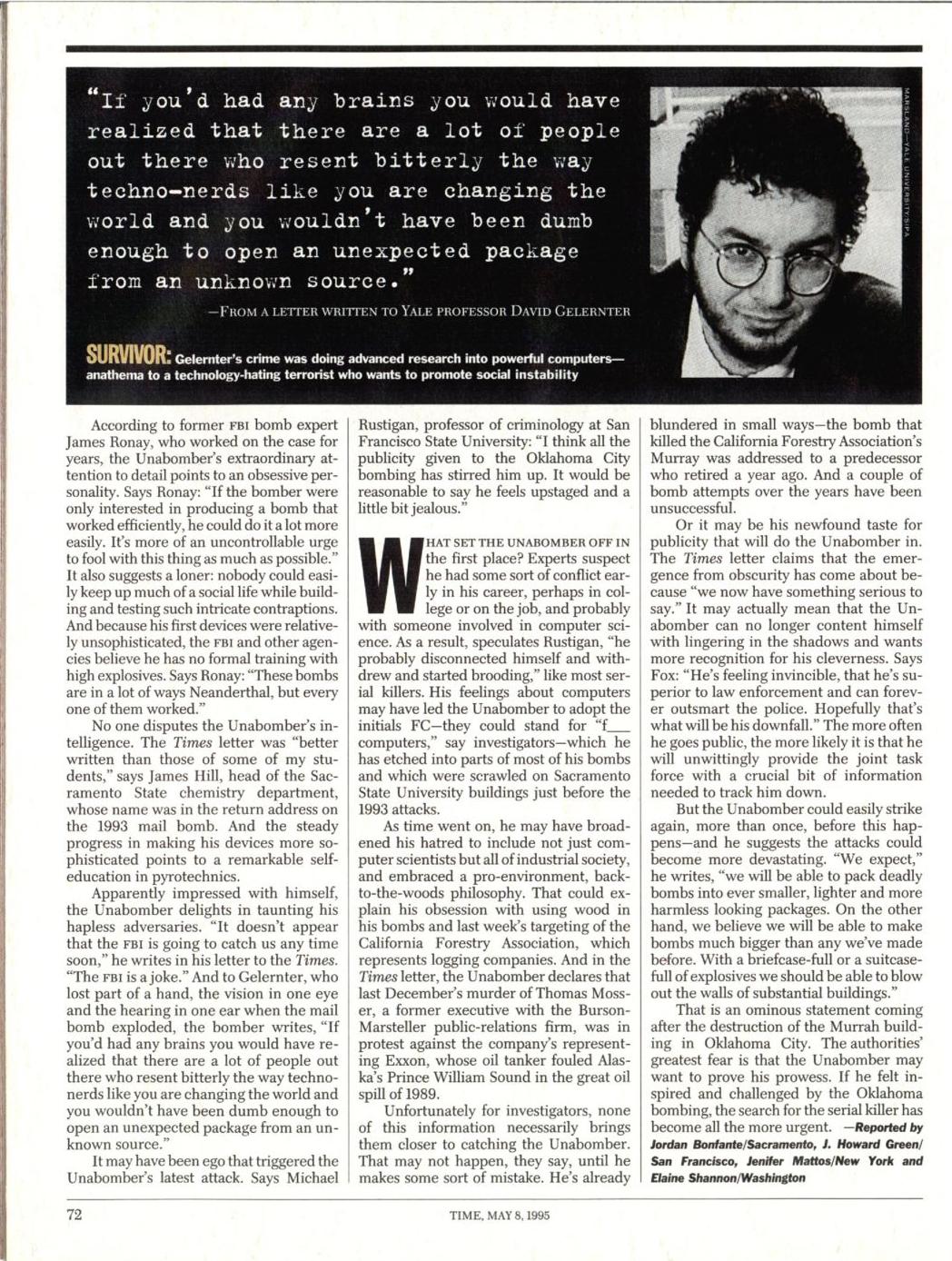

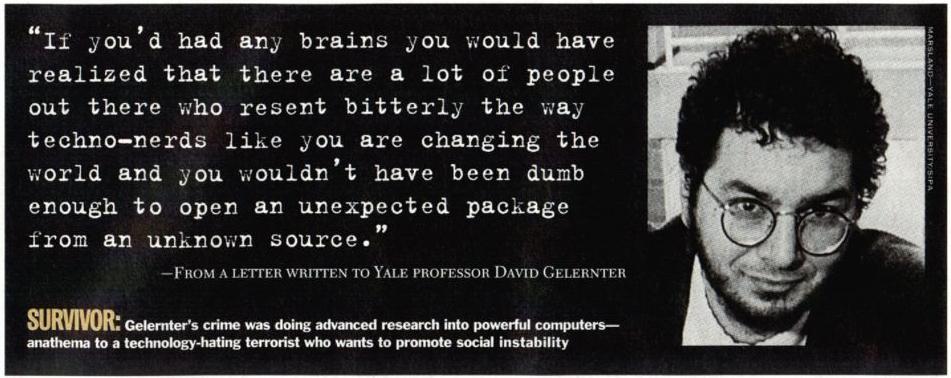

If nothing else, the letter to the Times and three more letters -- one to victim David Gelernter, a Yale computer scientist seriously injured in a 1993 blast, and the other two to potential targets whose names are being kept secret -- have given investigators their best clues yet. An additional 100 agents were quickly added to the 30-person, San Francisco-based Unabom task force run jointly by the FBI, the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms and the post office.

Set up in 1993 after the explosion at Yale and one that had taken place in California two days earlier, the task force has had only the tiniest scraps of evidence to go on. In 1987 a witness spotted someone leaving what proved to be a bomb outside a computer store in Salt Lake City, Utah, and helped police produce a composite sketch of a white man, now in his 40s, about 6 ft. tall, with light hair, a moustache and glasses. Nearly two years ago, the bomber sent a brief, cryptic note to the Times in which he described himself only as an "anarchist." Besides the sketch of the Unabomber and his letters, just about the only clues are the locations of his attacks, the identities of his targets and the fragments of his trademark bombs.

That evidence leads investigators to suspect that the Unabomber may be based in Northern California: he has placed bombs in Sacramento and Berkeley; last week's letters and bomb were all mailed from Oakland; and he used a Sacramento State University faculty member's name on a 1993 bomb's return address. Moreover, the Times letter refers to "searching the sierras" for bomb-testing sites. But while he's clearly familiar with the territory, says FBI special agent Jim Freeman, who heads the joint task force, that "doesn't necessarily mean he lives or works in this area."

To construct a psychological profile of the terrorist, investigators have tried to figure out his motives and how he thinks. In particular, they have studied his choice of targets and bomb-making style, which has always been quirky and meticulous. The Unabomber's devices are generally handcrafted, with many parts, including tiny levers, carved from wood. FBI forensics experts have found everything from scrap wood to pieces of mahogany and other hardwoods used in furniture. One bomb contained a twig from a cherry tree. The bomber makes some of his own metal parts too, including pins and even screws. Then the whole thing is generally placed in a homemade wooden box before being mailed or delivered.

According to former FBI bomb expert James Ronay, who worked on the case for years, the Unabomber's extraordinary attention to detail points to an obsessive personality. Says Ronay: "If the bomber were only interested in producing a bomb that worked efficiently, he could do it a lot more easily. It's more of an uncontrollable urge to fool with this thing as much as possible." It also suggests a loner: nobody could easily keep up much of a social life while building and testing such intricate contraptions. And because his first devices were relatively unsophisticated, the FBI and other agencies believe he has no formal training with high explosives. Says Ronay: "These bombs are in a lot of ways Neanderthal, but every one of them worked."

No one disputes the Unabomber's intelligence. The Times letter was "better written than those of some of my students," says James Hill, head of the Sacramento State chemistry department, whose name was in the return address on the 1993 mail bomb. And the steady progress in making his devices more sophisticated points to a remarkable self- education in pyrotechnics.

Apparently impressed with himself, the Unabomber delights in taunting his hapless adversaries. "It doesn't appear that the FBI is going to catch us any time soon," he writes in his letter to the Times. "The FBI is a joke." And to Gelernter, who lost part of a hand, the vision in one eye and the hearing in one ear when the mail bomb exploded, the bomber writes, "If you'd had any brains you would have realized that there are a lot of people out there who resent bitterly the way techno-nerds like you are changing the world and you wouldn't have been dumb enough to open an unexpected package from an unknown source."

It may have been ego that triggered the Unabomber's latest attack. Says Michael Rustigan, professor of criminology at San Francisco State University: "I think all the publicity given to the Oklahoma City bombing has stirred him up. It would be reasonable to say he feels upstaged and a little bit jealous."

What set the Unabomber off in the first place? Experts suspect he had some sort of conflict early in his career, perhaps in college or on the job, and probably with someone involved in computer science. As a result, speculates Rustigan, "he probably disconnected himself and withdrew and started brooding," like most serial killers. His feelings about computers may have led the Unabomber to adopt the initials FC-they could stand for "f------ computers," say investigators-which he has etched into parts of most of his bombs and which were scrawled on Sacramento State University buildings just before the 1993 attacks.

As time went on, he may have broadened his hatred to include not just computer scientists but all of industrial society, and embraced a pro-environment, back-to-the-woods philosophy. That could explain his obsession with using wood in his bombs and last week's targeting of the California Forestry Association, which represents logging companies. And in the Times letter, the Unabomber declares that last December's murder of Thomas Mosser, a former executive with the Burson-Marsteller public-relations firm, was in protest against the company's representing Exxon, whose oil tanker fouled Alaska's Prince William Sound in the great oil spill of 1989.

Unfortunately for investigators, none of this information necessarily brings them closer to catching the Unabomber. That may not happen, they say, until he makes some sort of mistake. He's already blundered in small ways -- the bomb that killed the California Forestry Association's Murray was addressed to a predecessor who retired a year ago. And a couple of bomb attempts over the years have been unsuccessful.

Or it may be his newfound taste for publicity that will do the Unabomber in. The Times letter claims that the emergence from obscurity has come about because "we now have something serious to say." It may actually mean that the Unabomber can no longer content himself with lingering in the shadows and wants more recognition for his cleverness. Says Fox: "He's feeling invincible, that he's superior to law enforcement and can forever outsmart the police. Hopefully that's what will be his downfall." The more often he goes public, the more likely it is that he will unwittingly provide the joint task force with a crucial bit of information needed to track him down.

But the Unabomber could easily strike again, more than once, before this happens -- and he suggests the attacks could become more devastating. "We expect," he writes, "we will be able to pack deadly bombs into ever smaller, lighter and more harmless looking packages. On the other hand, we believe we will be able to make bombs much bigger than any we've made before. With a briefcase-full or a suitcase-full of explosives we should be able to blow out the walls of substantial buildings."

That is an ominous statement coming after the destruction of the Murrah building in Oklahoma City. The authorities' greatest fear is that the Unabomber may want to prove his prowess. If he felt inspired and challenged by the Oklahoma bombing, the search for the serial killer has become all the more urgent. --Reported by Jordan Bonfante/Sacramento, J. Howard Green/ San Francisco, Jenifer Mattos/New York and Elaine Shannon/Washington