Michael Loadenthal

The Politics of Attack

Communiqués and Insurrectionary Violence

2017

1. Concerning method and the study of political violence

A feminist method for studying violence

Communiqués as political theory

Surveying communiqué collections

The challenges of collecting communiqués

Opaque truths and verifiability

Arsonist theorists and “primitive rebels”

New methodologies of critical inquiry

Duel use and returning to the principal of “do no harm”

2. Insurrection as history from Guy Fawkes to black blocs

History, genealogy, and subjectivity

A genealogical account of discourse

Introducing a past history of insurrectionary attack

The twenty-first century: from Chiapas to 9/11

“Anti-globalization” and the black bloc

The Al-Qaeda effect and the diffusion of the rioters

3. Insurrection as a post-millennial, clandestine, network of cells

A modern history of insurrectionary attack

The Informal Anarchist Federation

The Conspiracy of Cells of Fire

Práxedis G. Guerrero Autonomous Cells for Immediate Revolution

Individualists Tending Toward the Wild

Case study: internationalizing campaigns of attack

4. Insurrection as warfare, terrorism, and revolutionary design

Re-reading urban guerrilla warfare

The questions of “terrorism” and “violence”

A revolutionary reading of political violence

Affinity groups, monikers, and guidelines

5. Insurrection as theory, text, and strategy

The modern insurrectionary turn

Magazines, zines, and anonymous texts

Conclusion: an insurrectionary canon? More like an insurrectionary cannon!

6. Insurrection as values-driven theory and action

Establishing eight values of the insurrectionary canon

Attack: continuous, immediate, and spontaneous

Against management and movements, for temporary informality

Rejecting the (capital “L”) Left

Informal, temporary collectivities of affinity

Against reformism, democracy, and mediation

For illegalism, against “civil” anarchists

Against domestication and technology, for re-wilding

7. Insurrection as anti-securitization communication

For a new (poststructural) intersectionality

The “Totality” and system-level violence

Critically reading security and insurrection

On performativity and spectacle

Political violence as performative spectacle

A performance requires an audience

[Front Matter]

[Series Title Page]

CONTEMPORARY ANARCHIST STUDIES

A series edited by

Laurence Davis, University College Cork, Ireland

Uri Gordon, University of Nottingham, UK

Nathan Jun, Midwestern State University, USA

Alex Prichard, Exeter University, UK

Contemporary Anarchist Studies promotes the study of anarchism as a framework for understanding and acting on the most pressing problems of our times. The series publishes cutting-edge, socially engaged scholarship from around the world – bridging theory and practice, academic rigor and the insights of contemporary activism.

The topical scope of the series encompasses anarchist history and theory broadly construed; individual anarchist thinkers; anarchist informed analysis of current issues and institutions; and anarchist or anarchist-inspired movements and practices. Contributions informed by anti-capitalist, feminist, ecological, indigenous and non-Western or global South anarchist perspectives are particularly welcome. So, too, are manuscripts that promise to illuminate the relationships between the personal and the political aspects of transformative social change, local and global problems, and anarchism and other movements and ideologies. Above all, we wish to publish books that will help activist scholars and scholar activists think about how to challenge and build real alternatives to existing structures of oppression and injustice.

International Editorial Advisory Board:

Martha Ackelsberg, Smith College

John Clark, Loyola University

Jesse Cohn, Purdue University

Ronald Creagh, Université Paul Valéry

Marianne Enckell, Centre International de Recherches sur l’Anarchisme

Benjamin Franks, University of Glasgow

Judy Greenway, Independent Scholar

Ruth Kinna, Loughborough University

Todd May, Clemson University

Salvo Vaccaro, Università di Palermo

Lucien van der Walt, Rhodes University

Charles Weigl, AK Press

Other titles in the series

(From Bloomsbury Academic):

Anarchism and Political Modernity

Angelic Troublemakers

The Concealment of the State

Daoism and Anarchism

The Impossible Community

Lifestyle Politics and Radical Activism

Making Another World Possible Philosophical Anarchism and Political Obligation

(From Manchester University Press):

Anarchy in Athens

The Autonomous Life?

[Title Page]

The politics of attack

Communiqués and insurrectionary violence

Michael Loadenthal

Manchester University Press

[Copyright]

Copyright © Michael Loadenthal 2017

The right of Michael Loadenthal to be identified as the author of this work has been asserted by him in accordance with the Copyright, Designs and Patents Act 1988.

Published by Manchester University Press

Altrincham Street, Manchester M1 7JA

www.manchesteruniversitypress.co.uk

British Library Cataloguing-in-Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data applied for

ISBN 978 1 5261 1445 7 hardback

ISBN 978 1 5261 1444 0 paperback

First published 2017

This work is licensed under the Creative Commons Attribution-Non-Commercial-ShareAlike 2.0 England and Wales License. Permission for reproduction is granted by the editors and the publishers free of charge for voluntary, campaign and community groups. Reproduction of the text for commercial purposes, or by universities or other formal teaching institutions is prohibited without the express permission of the publishers.

The publisher has no responsibility for the persistence or accuracy of URLs for any external or third-party internet websites referred to in this book, and does not guarantee that any content on such websites is, or will remain, accurate or appropriate.

Typeset

by Toppan Best-set Premedia Limited

Figures

3.1 CARI-PGG’s logo included in communiqués

3.2 Image circulated with “First communiqué of Wild Reaction (RS)”

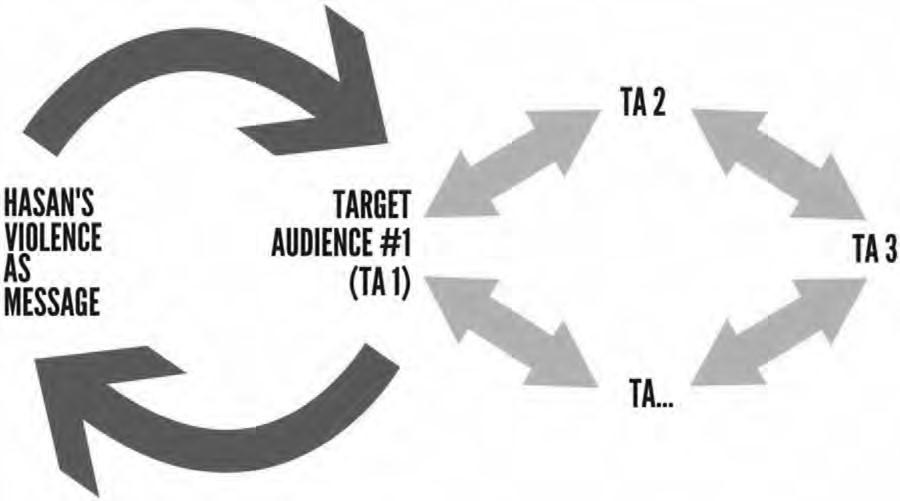

7.1 Secondary–tertiary target audience concept map

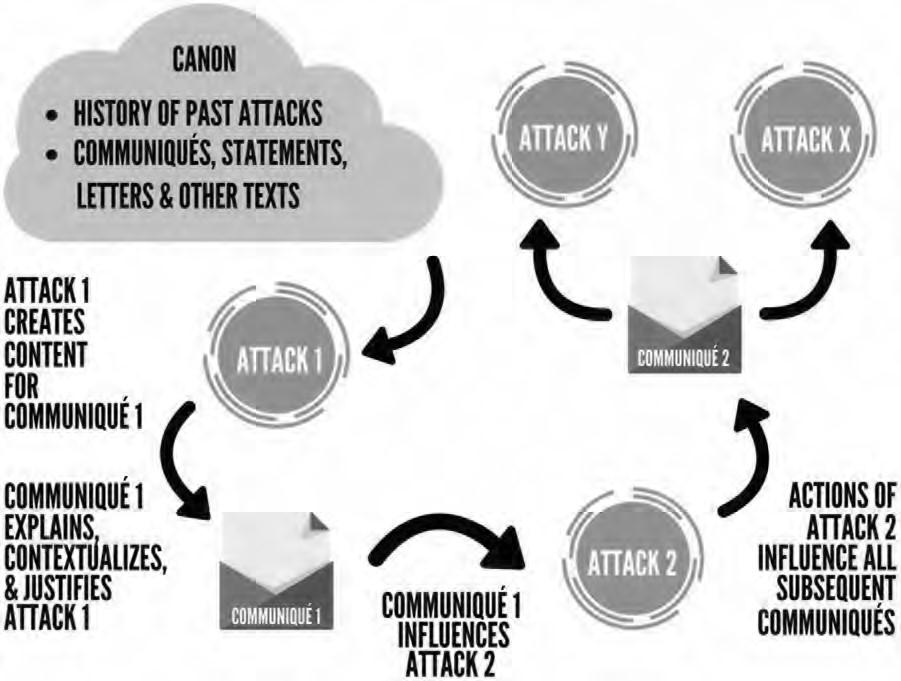

7.2 Communiqué/attack–form/function concept map

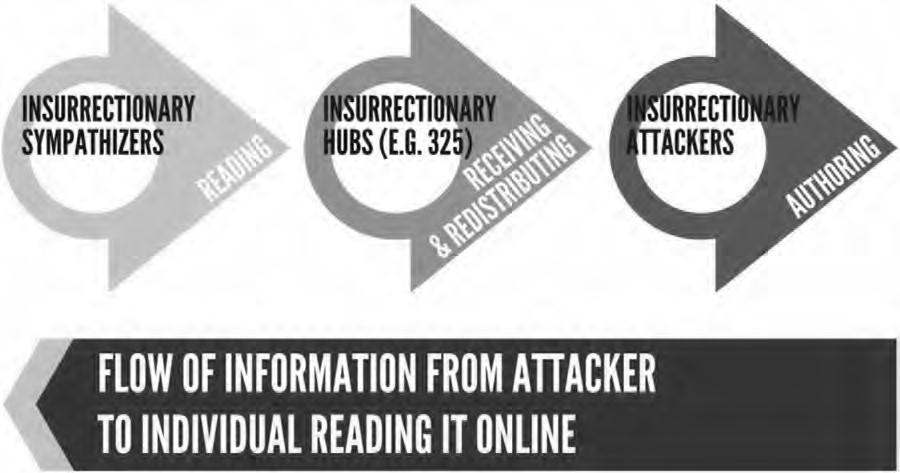

7.3 Knowledge transmission concept map

Preface

On a chilly, rain-soaked April day in the nation’s capital, I find myself trudging through the puddles looking for a post office. Now, while my use of the federal mail system is quite limited in these days of e-mail, digital document signing, and electronic bill paying, today I’m mailing my contract for the publication of my first book, this book.

As fate would find it, the contract reaches my desk while I am residing in Washington, DC, for some precariously contingent teaching work, residing in a colleague’s Capitol Hill basement unit. Through the wonders of smartphone mapping, on my walk to the metro, I locate a post office only a few blocks from me. I traverse the various post-9/11 fortifications surrounding the Capitol area designed to blend into the landscape, past the cars being searched for bombs hidden beneath their chassis, past the officers hiding behind panopticonal, opaque glass screens, and eventually find myself inside of one of the main Congressional buildings; part of a series of such facilities connected to one another through a series of tunnels, elevators, and stairs and just adjacent to the south Capitol lawn.

I enter the building through the “non-members [of Congress]” door, submit myself and my possessions to an x-ray machine and metal detector, and am eventually cleared to enter and given relative free rein to explore. I begin by riding the “members-only” elevator down to the basement, sharing the ride with a man who from his age and dress I assume is a Congressman. His body language expresses his annoyance that a dripping wet, hooded, septum-pierced traveler is descending the elevator shaft with him.

After exploring the catacombs and long hallways of the lower level, I begin asking for the post office. When I eventually find it, its familiarity and unremarkability are the only things I note. It is nearly identical to every other post office I have ever encountered. I mail my package and wander around the building a bit. I pass the offices of various Representatives proudly displaying their state flags. I pass bubbly, expertly quaffed, internaged women and men, most of whom are too buried in their phones to even notice me. I overhear discussion of legislation, travel, last night’s social events. Though the building is on the surface a public place, I feel like an outsider, like everyone must know I do not belong, and I imagine the buildings and its inhabitants exuding a small sigh of relief when I depart its doors without incident.

Upon leaving the building and re-entering the rainy Thursday morning, I am struck by how very odd the whole experience was. Here I am, an underdressed (to say the least), non-umbrella holding, non-badge displaying, non-member of Congress exploring the labyrinths of technocratic statecraft, looking to mail a package that – when abstracted to its most sensational – is chiefly focused on underground actors mailing explosives to the offices of politicians. This book contract, securing the publication and distribution of a foray into insurrectionary warfare, passed through the hands and x-rays of the US Capitol Police, and in that moment I am reminded of FBI press conferences where manila envelopes are held up to display improvised explosive devices intercepted en route.

I imagine my own package sitting in a bin, deep inside the federal building, already buried beneath other mail. Tick, tick, tick. It has yet to reach the world. Tick, tick, tick. I imagine it is waiting to explode. Tick, tick, tick. I imagine that we live in a world where ideas and arguments burst from the pages and into our consciousness.

This book is an examination of militant resistance, and while some will be quick to call bombs in the mail and the arson of property “terrorism”, nothing we could do can ever approach the terror inherent in statehood. As the post-9/11, anarcho bathroom graffiti so often said, “The State is the only terrorist!”

As I remember my drenched walk through the vaults of centralized power, I think of my own manila package – one that I hope will be incendiary – and my own battles with the forces of domination. I think of the morning’s events and I laugh just audibly enough that it makes my fellow hallway travelers notice, and maybe, just maybe, threatens their sense of security that has become such a hallmark of state control.

Acknowledgments

This book would not have been possible without the kind efforts of a number of individuals. I would like to first thank my amazing dissertation committee, chaired by Richard Rubenstein, and joined by Leslie Dwyer and John Dale. Rich, without your patience, generosity, guidance, and support, none of this would have been possible. I would also like to thank the Contemporary Anarchist Studies series editors who provided feedback throughout this process. Thank you to Laurence Davis, Nathan Jun, Alex Prichard, and especially Uri Gordon, who was always a voice of encouragement. Additional thanks is due to the great team at Manchester University Press, especially Thomas Dark, Alun Richards, and Robert Byron. I would also like to sincerely thank Bruce Hoffman and Anne Routon at Columbia University Press for their support in my early quest to locate a suitable publisher.

I am thankful for the support of Solon Simmons who was a sounding board for some of my methodological conundrums, and William Leap who first introduced me to corpus linguistics. My most heartfelt appreciation and praise to my former-students-turned-research-assistants at Georgetown University who helped to compile the communiqué corpus. Thank you to Phoebe Wild who began the collaborative endeavor, Anna Colette Heldring and Annie Kennelly who joined us later, and Jessica Anderson who saw it through in its final stages. I hope these relationships were mutually beneficial and collaboratively non-coercive. My most humble gratitude to the staff at Georgetown’s Program on Justice and Peace and the Center for Social Justice Research, Teaching & Service, who provided encouragement and office space during the writing phase. A special thank you to thank Kayla Corcoran who assisted me in constructing the figures contained in the final chapter. Last, but certainly not least, I am humbled to thank Georgetown’s Andria Wisler, Randall Amster, and Mark Lance – dazzling scholars, friends, allies, and colleagues in the truest sense. I would also like to thank Gwyneth O’Neill and John Copacino at Georgetown’s Criminal Justice Clinic for shepherding me through my first federal felony, for helping keep me out of prison, and for allowing us to stand tall in a new era of criminalized dissent.

I also must thank the various members of the North American Anarchist Studies Network who helped me locate some of the more obscure historical texts from anti-state attackers of centuries past. Thank you as well to the members of the Critical Studies on Terrorism Working Group who provided insight at various points in this process. I also could not have completed this project without the use of a number of key institutions whose libraries I plundered for texts on linguistics, discourse analysis, poststructural philosophy, guerrilla warfare, and anarchist histories. Thanks to the re-shelvers at the libraries of Georgetown, George Mason University, Northern Kentucky University, University of Cincinnati, and especially Donald Russell at Provisions in Fairfax, VA. I also must thank my friends Gary Hall and Michael J. Woods who provided me with bedrooms to hide away and write, Amanda Meister who took care of the wee ones during my doctoral defense, and the Washington Metro Area Transit Authority – without your constant delays and slow service I would have never been able to get so much reading done.

Of course I have to thank the clandestine window smashers and fire starters distributed throughout the world: Without you, these pages would be quite a different story. Thanks for always writing such passionate prose, and thank you to those who were diligent with their footnoting, crossreferencing, and attribution. Your eye for anal-retentive editing has not been overlooked.

I would like to thank my dearest kids, Emory Sheindal, Simon Bella, and Tevye Yosef who were willing to share their Daddy with this time-consuming enterprise, and who inspire me every day to be brave, take risks, and work towards a brighter future.

Finally, I would like to thank my partner and co-conspirator, the brilliant anthropologist, Jennifer Grubbs. Jennifer, thank you for listening to me talk about my work, helping to create time for me to write, dealing with the never-ending stacks of books strewn about, and for always encouraging me to be better.

Abbreviations

| 17N | Organization 17 November |

| ALF | Animal Liberation Front |

| BB! | Bash Back! |

| CARI-PGG | Práxedis G. Guerrero Autonomous Cells for Immediate Revolution |

| CCF | Conspiracy of Cells of Fire |

| CSS | Critical Security Studies |

| CTS | Critical Terrorism Studies |

| ELF | Earth Liberation Front |

| EMETIC | Evan Mecham Eco-Terrorist International Conspiracy |

| EZLN | Zapatista Army of National Liberation (Ejército Zapatista de Liberación Nacional) |

| FAI | Informal Anarchist Federation (Federazione Anarchica Informale) |

| F.A.I. | Iberian Anarchist Federation (Federación Anarquista lbérica) |

| FAI-M | Informal Anarchist Federation – Mexico |

| FARC | Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (Fuerzas Armadas Revolucionarias de Colombia) |

| HRC | Human Rights Campaign |

| IED | improvised explosive device |

| IEF | Institute for Experimental Freedom |

| IID | improvised incendiary device |

| IRF | International Revolutionary Front |

| ITS | Individualists Tending Toward the Wild |

| OPCA | Obsidian Point Circle of Attack |

| OPCAn | Obsidian Point Circle of Analysis |

| PIRA | Provisional Irish Republican Army |

| RAF | Red Army Faction |

| RB | Red Brigades |

| RC-ALB | Revolutionary Cells – Animal Liberation Brigade |

| RS | Wild Reaction (Reacción Salvaje) |

| RZ | Revolutionary Cells (Revolutionäre Zellen) |

| TAZ | Temporary Autonomous Zone |

| TIC | The Invisible Committee |

| WTO | World Trade Organization |

| WUO | Weather Underground Organization |

1. Concerning method and the study of political violence

Ah hell. Prophecy’s a thankless business, and history has a way of showing us what, in retrospect, are very logical solutions to awful messes … Things are certainly set up for a class war based on conveniently established lines of demarcation, and I must say that the basic assumption of the present set up is a grade A incitement to violence. (Vonnegut 1999, chap. IX)

When asked about anarchism’s association with violence, I often reply by inquiring whether one would ask the same thing of a retail clerk, a stockbroker, a lawyer, a priest, an engineer, a taxpayer, a consumer, a liberal, a conservative – or any other identity attribute associated with mainstream society. Most assuredly, the scale of violence perpetuated by the day-to-day operations of capital and the state is grossly disproportionate to anything in the anarchist lexicon, with upwards of 100 million deaths from wars alone during the twentieth century. I daresay that the sum total of people killed or physically injured by anarchists throughout all of recorded history amounts to little more than a good weekend in the empire … Are anarchists violent? Sometimes, but more so when they are participating in the casual, invisible, structural violence of modern life than when they are smashing its symbols of oppression. (Amster 2012, 43–44)

An anarchist group has claimed responsibility for an arson attack on North Avon Magistrates’ Court … police are investigating the on-line claims but say they do not have the evidence to link it to other attacks carried out on buildings owned by “establishment” bodies, including the police, the Army and various banks. In a post on the 325. nostate website, people naming themselves as the Informal Anarchist Federation, said: “10 camping gas canisters were enough to devastate the front lobby, with a homemade napalm mixture as the detonator. We chose the early hours to avoid any injuries.” (The Bristol Post 2014a)

Introduction

Throughout the past decade and a half, scholarship focused upon the study of political violence, specifically that which can clearly be labeled as terrorism, has rapidly increased (Ranstorp 2007; Silke 2009). With the powerful aftereffects of the 9/11 attacks, interest in those pursuing political, social, and religious objectives through violence found an obvious place in the academy. Largely, this scholarship was dealt with through the fields of Terrorism Studies and Social Movement Studies, as well as interrelated disciplines such as Criminology, Security Studies, and Sociology. While these fields have often overlapped through interdisciplinary pursuits, each has its own epistemological presumptions, methodological tendencies, and canonical truths.

For the study of political violence, and especially clandestine political violence which is the subject herein, one is often positioned at the crossroads between interpreting the subject as a terrorist or a social movement and, as such, is led towards those corresponding disciplines, literatures, and presumptive groundings. Keeping in mind the poststructuralist assertion that the production of knowledge – especially that which is involved in the formation of political policy – is never a neutral endeavor (Foucault 1980, 98), the collection of evidence and the construction of arguments is inherently the culmination of intentional decisions. When faced with these choices, held up against the subject of post-millennial, anti-authoritarian, insurrectionary networks, such concerns are paramount. Those who choose to pursue study through the literature of Terrorism Studies, are likely to be burdened with not only the state-centric bias of background literature, but also the field’s lack of theorization and its focus on counterterrorism (della Porta 2013, 282) and other securitization implementations. Those who choose to examine such networks as social movements,[1] a field that bases its focus on manifestations of social protest, also face difficulties as this field has often remained apart from radical politics within militant and violent protest, and has a corresponding theorization abyss regarding these borderlands.

Since the end of the twentieth century, an explosion of anti-state networks of clandestine militancy have emerged throughout the world. Through thousands of attacks, revolutionaries have been constantly at war with the status quo, targeting localized manifestations of state and capital in an attempt to create a venue of conflict that can bring about system-level change. Though distributed globally and irregularly active, these networks attack with frequency and vigor, making them a top priority for law enforcement. In one locale, Bristol, England, a city of around half a million residents, insurrectionary anarchist networks have been responsible for “over a hundred offensives dating [from] 2010 [to December 2014]” (Bevan 2014, pts. 00:44–00:50) according to the lead investigating officer. According to sympathetic activists, this number may be far higher, as those compiling local communiqués were able to locate more than 60 attacks in a two-anda-half year period (Bevan 2014). These attacks, many of which involve arson, are said to have caused approximately £20 million (~$31 million) in damage. The vast majority of these attacks have been claimed via online communiqués through anonymous monikers such as the Informal Anarchist Federation (FAI). The FAI moniker has been adopted so frequently that, despite not having a centralized structure or “members,” the entity was declared to be a terrorist organization by the European Union in 2009.

In only a few years, in the city of Bristol alone, the clandestine political networks under examination were responsible for the £18 million arson of a police firearms training center, the burning of UK Border Agency vehicles and personal vehicles belonging to a Mayor and other local politicians, sabotage targeting a local commuter rail service, and the arson of industrial infrastructure, which resulted in a loss of radio and TV service to more than 80,000 homes (Channel 4 News 2013; Malik 2012; 2013). Other Bristolarea targets struck in the last few years include private security company G4S and the zoo. This brief look at Bristol is meant to provide insight as to the scale of the subject. The international, insurrectionary milieu – the subject of this book – is deserving of attention even if one only judges them on the basis of their destructive capabilities. Though modern attackers are not successfully assassinating heads of state, as was somewhat commonplace in late nineteenth and early twentieth century, they are dispatching bombs to European Prime Ministers, burning down Mexican Walmarts, and carrying out thousands of costly attacks targeting governmental, financial, commercial, and other sites. Furthermore, since there have been very few arrests of this movement, we know relatively little about the participants. Because of this reality, in order to understand the insurrectionary arsonists, bomb makers, and saboteurs, we must examine their frequent articulations of critique – the communiqué.[2] Despite often failing to do this, the need for such forms of analysis have been expressed in mainstream press reporting, for example this article from The Bristol Post which states:

To understand why these attacks are happening, for what reason, and how these individuals identify politically, it’s recommended to read their words and statements for clarity. Each attack is by a unique established group of individual/s, with a diversity of anonymous cloaks, presenting varying ideological viewpoints. The beauty of the insurrectionist movement you might say. (2014b)

While these attacks, and the communiqué/claims of responsibility that accompany them, have received nominal attention in the (counter) Terrorism Studies literature, very little focus has been paid to their political ideology and socio-political critique. Moreover, the interaction between “radical social movements” (Koehler 2014, 2) and their broader contexts (e.g. social, political, ideological) is under researched.

The following introductory chapter will examine a number of key issues of central importance to the book. First it will discuss the object of analysis – the communiqué – as a method for delivering critical analysis typically reserved for more formalized texts. This approach begs the question: “Can one read a claim of responsibility (i.e. a communiqué) in the same formalized manner as one would read The Communist Manifesto or The Federalist Papers?” This discussion will also survey the available literature that focuses on the study of communiqués, identifying weaknesses and necessary corrections to this reading. Second, this chapter identifies some initial difficulties arising from the study of these objects, specifically problems relating to verifiability, triangulation, determining credible authorship, and the inherent subjectivity in historical interpretation. Finally, this chapter discusses the limitations and scale of the study, establishing two key questions, which are pursued throughout the remaining chapters. These questions aim to guide the reader to evaluate two central claims: (1) Modern insurrectionary networks are informed by, and act to, constitute an “insurrectionary canon,” and (2) Due to the poststructural influence on the modern insurrectionary critique, the milieu will resultantly carry forth an expanded understanding of structural violence and inequality.

A feminist method for studying violence

While a more complete discussion of ethically-embedded, critical modes of inquiry is pursued at the conclusion of this chapter, a brief discussion of ethics is warranted before proceeding. A methodological positioning informed by feminist ethics permeates the proceeding discussions. The feminist methodology and ethic of research (Mies 1983; Cook and Fonow 1986; 1991; Maguire 1987; Harding 1988; Lather 1988; Kirby and Kate 1989; Collins 1991; Reinharz 1992) adds a great deal, including a reading of identity politics, standpoint theory, action-orientated research, and embedded, emotive and sincere participatory involvement. From among these tendencies, this inquiry seeks to maintain a single goal, namely that research generates a reciprocally positive impact for the subject (Oakley 1981), and in this manner, the respondent community is not seen as a vessel containing knowledge to be taken, but rather as a partner in a collaborative endeavor to engage in knowledge building, not knowledge production. In the present discussion of insurrectionary anarchism, this involves the construction of knowledge for social action and not further criminalization, and remaining accountable to the community of activists and scholars whom the movement is based around.

Feminist methodology seeks to subvert traditional power relationships and ethical pitfalls, and according to one scholar, challenges four concerns otherwise recurrent in field research:

1.) The increased salience of race/ethnicity, gender, and class in the research relationship; 2.) the objectification of research subjects; 3.) the influence of social power on who becomes a research subject; and 4.) problematic assumptions in the conventional analytic approaches. (Sprague 2005, 121)

In practice, the following analysis attempts to destabilize the “othering” (Letherby 2003, 20–24; Sprague 2005, 125) of the subject, which tends to portray the researchers’ position as normative. In this manner, it becomes the task of a constructed taxonomy to position urban guerrillas among a wider socio-political movement, and through placement within such a continuum, such “violent” actors can be understood as similarly rational actors choosing to pursue a less popular – albeit illegal – form of protest. This also means that as a researcher, one can position themselves within the research as not only an observer, but a participant (Cole 1990, 159–166; Letherby 2003, 8) in the subject community. Such an approach can allow one to “understand the kind of questions that needed answering” (Cole 1990, 162), as well as the process of knowledge construction for the respondent community. This approach is far from mainstream, as most often, political actors adopting counter-state and violent strategies are viewed within the exoticized lens akin to the primitive savage of the colonial, anthropological, village subject. This tendency is (as can be expected) further exaggerated in mainstream journalistic accounts of these movements, which often carry sensationalist headlines such as “Meet the NihilistAnarchist Network Bringing Chaos to a Town Near You” (Hanrahan 2013). By de-sensationalizing the violence, and instead focusing on the movement’s political discourse, one hopes to shift the readers’ attention away from the frequency of the bombs, and towards the validity of the critiques.

Furthermore, one of the methods of subverting the pitfalls of traditionally unethical scholarship is to be found in emphasizing the subject’s perspective, and allowing the knowledge holder to determine the research agenda and its analysis (Sprague 2005, 141). This is a contribution of post-1970s feminist methodological battles and a notable aspect of my methodological pursuit. Taken as a whole, a feminist methodological approach to qualitative investigation is adopted precisely because it addresses issues of power within the realm of research (Letherby 2003, 114). It does so in a practically applicable manner aimed at subversion and the development of new methods of investigation that exist as counter forces to traditionalism, knowledge banking, and the expropriation of stories from an othered subject. Therefore it is the aim of the proceeding discussion to not borrow the sexy dynamism of insurrection to construct an engaging argument, but rather to move beyond the discussion of these networks as merely the producers of fires and explosions and instead begin to understand them as social critics, “organic intellectuals” (Gramsci 1971b, 9), and philosophical practitioners.

Communiqués as political theory

I say to you: that we are in. a battle, and that more than half of this battle is taking place on the battlefield of the media. And that we are in a media battle in a race for the hearts and minds … And that however far our capabilities reach, they will never be equal to one thousandth of the capabilities of … that [which] is waging war on us. (al-Zawahiri 2005, 10)

Communiqués are seen as an essential communicative component of insurrectionary attack. Following each incident of political violence – from a broken bank window to an assassinated nanotechnologist – the act is explained, “infused with meaning” (Hodges 2011, 5) via a text meant to expand the discourse on revolutionary struggle. This site, that of the communiqué, demonstrates the social construction of both the act (of “terrorism”) and the discourse (on “terrorism”). Both the event (i.e. the attack) and the object (i.e. the communiqué) are socially constructed phenomena (Stump and Dixit 2013, 108), serving to apply meaning and context for a wider audience. These explanatory frames discursively embed the act of anti-social violence, and have key functions within the construction of consequent discourses and attacks. To borrow an explanation from the bomb throwers themselves, “through the communiqués that accompany attacks we can begin an open debate on reflections and problems that, even if viewed through different lenses, are certainly focused on the same direction: revolution” (G. Tsakalos et al. 2012, 15). Such “requisite revolutionary discourse … following[ing] bombings against targets that serve domination” (G. Tsakalos et al. 2012, 11) typically takes the form of a written communiqué posted and circulated through a network of websites. These websites form a repository for the collection of communiqués and the establishment of a corpus. This communiqué corpus constitutes the central “data” for this book and its discussions.

Surveying communiqué collections

Academic and popular press books dealing specifically with communiqués as subject – often reprinting entire documents – have been sparse, interdisciplinary, and seemingly on the rise. Notable examples include edited volumes such as Europe’s Red Terrorists: The Fighting Communist Organizations (Alexander and Pluchinsky 1992), Speaking Stones: Communiqués from the Intifada Underground (Mishal and Aharoni 1994), Our Word Is Our Weapon: Selected Writings of Subcomandante Marcos (Marcos 2002), Voices of Terror: Manifestos, Writings and Manuals of Al Qaeda, Hamas … (Laqueur 2004), What Does Al-Qaeda Want? (Marlin 2004), Sing a Battle Song: The Revolutionary Poetry, Statements, and Communiqués of the Weather Underground 1970–1974 (Dohrn, Ayers, and Jones 2006), Earth Liberation Front 1997–2002 (Pickering 2007), the multi-volume series, The Red Army Faction: A Documentary History (Moncourt and Smith 2009a; 2009b), Creating a Movement with Teeth a Documentary History of the George Jackson Brigade (Burton-Rose 2010), Queer Ultraviolence: A BASH BACK! Anthology (Eanelli and Baroque 2012), and studies utilizing communiqués comingled with other forms of texts such as The Road to Martyrs’ Square (Oliver and Steinberg 2006) which documents Palestinian militant culture through communiqués, video transcripts, graffiti, and other ephemera. Additionally, there appears to be an increasing number of studies that apply a linguistic or discursive analysis to politically violent ephemera, such as farewell correspondences from suicide bombers (e.g. S. J. Cohen 2016) and jihadist magazines (e.g. Ingram 2015; Novenario 2016).

Yonah Alexander and Dennis Pluchinsky’s book provides one of the more comprehensive approaches to the examination of communiqués. Alexander and Pluchinsky (1992, x) focus on nine European “fighting communist organizations [FCOs],” and in speaking to their book’s limitations note:

This book was not designed to be an all-inclusive, detailed study of the European FCOs. To the authors’ knowledge, no such study exists. The intent was to compile a brief collection of documents (attack communiqués, ideological tracts, interviews, policy statements, etc.) … so that the reader can obtain a general understanding of how these groups think and view the world about them.

While the aforementioned books contain very valuable exhibitions of primary source materials, with exceedingly few exceptions, the communiqués are not analyzed thoroughly and are often simply presented. The texts are far more descriptive in nature, not analytical. Typically the volumes are nearly entirely the words of the non-state actor with a brief introductory frame written by an editor. While some are careful to discuss the texts in relation to actual events (e.g. Moncourt and Smith 2009a; 2009b; BurtonRose 2010), the texts themselves are rarely the focus. In none of the volumes surveyed is the political critique of the non-state actor held up as legitimate theory to be evaluated. Instead, it is often showcased in an exotic manner, or in the case of Laqueur’s edited volume, displayed as the writings of various “terrorists.”

Additional books cataloging the political writings of individual practitioners of political violence are quite common, such as those containing the words of Islamist figureheads Osama bin Laden (2005) and Sayyed Hassan Nasrallah (2007), Marxist guerrilla leader Ernesto “Che” Guevara (1997), the Red Army Faction’s Ulrike Meinhof (2008), “New Afrikan” militants Jalil Muntaqim (2002), Kuwasi Balagoon (2003), and Russell Maroon Shoatz (2013), anarcho-primitivist “Unabomber” Theodore Kaczynski (2010d), and Animal Liberation Front activists Walter Bond (2011) and

Rod Coronado (2011). In these person-specific compilations, the original (and translated) works are presented with very little commentary and often no analysis. There are also frequent personal narratives, memoirs, autoethnographies, and autobiographies from individual actors that often portray life events but exclude formal political statements. Examples from the revolutionary left include those by North American militants Ann Hansen (2002) and David Gilbert (2011), West German urban guerrilla Bommi Baumann (2002), 1960s student protest leaders and Weathermen Mark Rudd (2010) and Bill Ayers (2009), American Indian Movement political prisoner Leonard Peltier (2000), Palestinian airplane hijacker Lelia Khaled (1973), Revolutionary Armed Forces of Colombia (FARC) guerrilla María Eugenia Vásquez Perdomo (2005), and Black Panther Assata Shakur (2001), as well as a semi-autobiographical, first-hand account from Basque ethnonationalist militants (Agirre 1975), Italian Red Brigade militants (Giorgio 2003), and Americans who joined Spanish Republicans to challenge fascism in the 1930s (Orwell 1980; Bailey 1993). Many more have been published digitally, including autobiographical accounts of 1996 Olympic Park bomber Eric Rudolph (2015) and American-born jihadi leader Omar Hammami (2012).

Communiqués as political texts are an under-theorized site for critical inquiry. Despite their prominence in the ephemera of clandestine networks of political violence, their compilation, interpretation, and analysis has been lacking. Some scholars (e.g. Harrison 2013) have focused on the development of methodologies for interpreting the ideological predilections of political manifestos. Though these works are instructive in a general sense, their focus on ideology and parties make them ill-suited for discussing antiideological, anti-political (i.e. those that reject politics as a method of social change) movements. Insurrectionary theorists posit that the foundational basis, whether anarchist or other, is never stoic or fixed but rather a “nonessentialist, non-ideology” (Rodríguez 2011b) enacted diversely by diverse actors. This makes demarcating what is and is not “insurrectionary” a difficult taxonomic task. In Sarah Harrison’s (2013, 55–56) study, the author focused on the discourse of right-wing political parties, identifying the frequency of select words and coding these keywords for thematic analysis.

Similar studies have been coordinated by the Manifesto Research Group/ Comparative Manifestos Project (2014) which has conducted “quantitative content analyses of parties’ election programmes from more than 50 countries covering all free, democratic elections since 1945.”

Not all acts of political violence – clandestine or otherwise – are claimed via a written communication. Some are claimed via video releases, audio transmissions, graffiti, or telephone calls, and still others are unclaimed. Research suggests that only approximately 14% of terrorist attacks occurring in the period 1998–2004 were followed by claims of responsibility, and that the rate is declining – with 61% of attacks claimed in the 1970s and 40% in the 1980s (Wright 2011). The issuing of communiqués following acts of violence is often dependent on the modus operandi of the movement (A. M. Hoffman 2010). Animal Liberation Front (ALF) and Earth Liberation Front (ELF) attacks are nearly universally claimed via a written communiqué – in approximately 93% of attacks (Loadenthal 2010, 89 (chart 3.3)) – which are then compiled and circulated by aboveground support networks such as Bite Back Magazine, the North American Animal Liberation Press Office, and the international, translation, and counter-information network “of the new generation [of] incendiary anarchy and global anticivilization attack” (K. Cohen et al. 2014, 251) embodied in websites such as 325.nostate, War on Society, and others. Comparatively, in attacks by Palestinian paramilitary organizations (1968–2004), 56% were claimed (A. M. Hoffman 2010, 621), while in other conflicts, especially those where non-state factions are less competitive in their battles for supporters, the rate is often much lower. In Provisional Irish Republican Army (PIRA) and affiliated attacks, since the paramilitary is seen as having fewer competitors than the various Palestinian factions, attacks in England (1973–1998) were claimed in less than 15% of cases (A. M. Hoffman 2010, 624). This has led some to conclude that anonymous, unclaimed attacks are actually the norm (Abrahms and Conrad 2016, 2), which is not the dominant trend in attacks by insurrectionary anarchists under discussion.

In examining the post-millennial clandestine attack networks that drew inspiration and modeling from the millennial anti-globalization, countersummit protests, it is no surprise that the militant edges of this movement are communiqué-rich sources. In a lengthy piece of strategic writing authored by anonymous individuals “somewhere in the [American] Mid-West” and affiliated with the direct action network Anti-Racist Action, the authors instruct:

It is important that all … [militant street] actions be followed with a comprehensive communiqué … This communiqué should discuss the action in terms of why it occurred, why specific conflicts/tactics developed and how this immediate struggle is connected with the broader Anarchist movement towards a liberated and creative world … Such communiqués are important in regards to reaching out to the broader populace, as well as in debunking the demonization of our activities as can be expected to emanate out of the corporate press. (G-MAC and People Within The ARA 2002, 220–221)

This commentary speaks to the reliance on communiqués as a speech act, and specifically as a means to self-report, spread propaganda, and challenge divergent accounts from media and liberal/sectarian sources. What explains the underground attackers’ preference for reporting via communiqués? Maybe it is that the communiqué structures a particular speech device and, in doing so, facilitates direct communication between a previously silenced entity (i.e. the attacker) and an often-curious recipient (i.e. the public).

The challenges of collecting communiqués

On a practical level, the collection of communiqués allowed for the construction of an approximated incident-based dataset: a historical recounting of the politics of direct attack as told through the broken windows, slashed tires, and burnt storefronts so eloquently rationalized through the texts. The construction of such a dataset begins with the development of strict ingroup/out-group rules for inclusion and exclusion. The construction of this rule set requires a more generalized familiarity with the content hosted on the website network surveyed. In discussing the analysis and mapping of “radical violence in social media,” researchers from the Swedish Defense Research Agency make the same observation, writing, “in order to develop relevant keywords that actually indicate radicalism, an in-depth knowledge of the milieu in question is required” (K. Cohen et al. 2014, 251). After familiarizing myself with its content over the course of years of reading,[3] broad parameters are established, tested, and then refined and recorded in a decision tree. Only incidents that were claimed via a communiqué and posted to the surveyed hubs were included. Similarly, communiqués that did not claim responsibility but offered more general critique, theory or debate were excluded.

This was by no means an easy task. The nature of clandestine, decentralized, and internationally-dispersed cells offers methodological challenges beyond simply the frequent inability to triangulate data and reach respondents to follow. In their discussion of the Revolutionary Cells (RZ) – a German, moniker-driven, direct action network operating between the 1970s and1990s – Moncourt and Smith (2009b, 2:221) discuss similar problems stating:

The Revolutionary Cell [RZ] seemed unstoppable in 1982, but tabulating their activity poses a methodological problem, as anybody could carry out an attack – from breaking some windows to planting a bomb – and claim it as an RZ action. Limiting the account to major actions is both arbitrary and unavoidable in a study not itself devoted to the Cells; nonetheless, readers should keep in mind that these major attacks [e.g. bombings, shootings] were accompanied by a much greater number of low-level actions [e.g. vandalism, sabotage], even if most of these are now largely forgotten.

It is precisely because of such cautionary methodological tales of woe that this study was constructed around the communiqué. Within these means, the presence of the primary source document equates to inclusion, not the subjectively judged “severity” of the attack. Thus, while the dataset will contain discussions of bombs, bullets, and Molotovs, to a larger degree it is the story of painted walls and broken windows. The history of the modern insurrectionary attacker mirrors that of the RZ, in that the frequency of revolutionary vandalism is overshadowed by the spectacle of tactics more easily understood as terrorism, namely those involving fire, explosives, and guns.

Furthermore, by including the entirety of attacks claimed by communiqué, and not sorting for those which are high profile, one allows the incident-based history of the movement to speak more for itself, rather than reflect the careful manipulation of inclusion and coding methods to serve political, securitization or rhetorical ends. In an analysis of 27,136 incidents of so-called “eco-terrorism” occurring between 1973 and 2010,[4] I discovered that the tactical coding of these incidents by state-funded and allied scholars allowed incendiary devices to be regarded as explosives, animal releases to be recoded as theft, and the frequent gluing of locks, slashing of tires, breaking of windows, and sabotaging of machinery to be nearly uniformly disregarded (Loadenthal 2010, 2014b).

Opaque truths and verifiability

In the deciphering of textual authenticity that is necessary in interpreting opaque online reports, one must acknowledge that misrepresentation, exaggeration, and outright fictitious incidents will most certainly occur. First, establishing authorship is difficult if not impossible in a variety of cases. Communiqués, letters, and other forms of text are written, published, and distributed, and those behind them are unknown. If ten texts are posted, it is difficult to determine if these are the work of a single author, ten independent authors, or possibly scores more writing collaboratively. While there are investigative linguistic techniques that can be used to identify and compare lexical features, word classes, and syntax – such as the frequency of words, parts-of-speech, and sentence constructions respectively – these methods are “not mature enough” (K. Cohen et al. 2014, 252) and outside the intent of this book.

Determining authorship remains a challenge for the analysis of online and anonymously authored texts, but does not present a particular challenge for this inquiry as establishing such points of identification are not necessary. The intent here is not to determine the identity or size of a given milieu, but rather its collectively-constituted universe of ideas. The linking of individual texts to individual or group authors would require extensive social network research, mapping, and triangulation, and because such an effort could easily be used by law enforcement for intelligence gathering and repression, it is avoided. Furthermore, identifying authors of anonymous communiqués disrupts the intended function of the text. The decision by an attacker to communicate via a moniker, pseudonym, or remain anonymous, is a conscious decision and the result of many calculations. In this sense we can consider each new articulation of identity – from the formal “FAI” or “ALF” to the playful “some insurrectionary anarchists” – as a new author, even if the new persona is embodied in a prior writer. It can be assumed that individual authors have written under a variety of pseudonyms, and that documents seemingly representing a multitude of voices are written by a single individual.

These sorts of challenges with reliability are not confined to the postings of anti-state revolutionaries, as both traditional non-state actors (e.g. the Taliban) and state security forces (e.g. Department of Defense) have intentionally falsified reports. Often, official accounts of counterterrorism operations are falsified to demonstrate strength to one’s opponents, weakness of the enemy, or to reframe skirmishes and otherwise muddy the waters of accurate narration. Such acts of narrative reframing can be used to retell a stone throwing demonstration against the military into a “terrorist attack”, or to reframe as “armed clashes”’ the invasion of a village (Loadenthal 2013). To cite one example, National Public Radio’s correspondent Leila Fadel states that when investigating Egyptian counterterrorist operations targeting jihadi insurgents, the state was found to have misrepresented itself, and engaged in outright false reporting. According to Fadel, “We found that a lot of that huge military operation was actually quite fictional. We couldn’t really find evidence of these major attacks. A lot of the reports of militants being killed were really exaggerated” (“With Egypt’s New Choices, The Burden Of Democracy” 2012).

This problem of reliability is not reserved to armies and arsonists. Consider the frequent revisions the nation was treated to in US President Obama’s retelling of the killing of Osama bin Laden (Hersh 2016). Since the SEAL team responsible for his assassination, and the soldiers charged with dumping his body into the sea, are few in numbers and discouraged from public comment, the citizenry is largely unable to access information regarding the historical event. Instead, the population is forced to accept the state narrative or enter into the ill-fated world of the “conspiracy theorist.” Similar problems exist in establishing fact regarding US drone strikes in Syria, Iraq, Pakistan, Afghanistan, Yemen, Libya, and Somalia; such accounts offer a single state-produced narrative which one is forced to accept, as comparative data sources are often unavailable. This is particularly relevant when questioning fatalities and victims’ status as combatants or civilians. When civilian eyewitness and NGO data is available, their reporting often shows disagreement between state accounts and those from local media, eyewitnesses, and foreign governments. For example, we can examine the wildly differing accounts of a January 2009 airstrike in Sudan, which targeted a convoy allegedly transporting weaponry to the Gaza Strip. According to media accounts, 39–41 people were killed in the airstrike (Harel, Melman, and Ravid 2009), yet according to the Sudanese Defense Minister, Abdel Rahim Mohamed, 119 were killed including “56 smugglers and 63 smuggled persons from Ethiopian, Somali and other nationalities” (Reuters 2009; BBC 2009). Here we see once again that the consumers of information, even those that attempt to triangulate and verify their sources, are left with stark choices: accept either the state or the non-state narrative, both of which are inaccessibly unverifiable.

This problem with data validity is additionally burdened by analysis that often accompanies reporting of acts of political violence, especially if those reports are found within security literature such as annual Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI) reports, INTERPOL papers, or government-funded attack databases, such as the Global Terrorism Database maintained by the National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism, a university-affiliated research project of the Department of Homeland Security. The complexity of political violence, its various strategic and tactical tendencies and intersecting but separate histories, are far beyond the scope of what most desire in seeking to contextualize an attack. Most data consumers simply want to know if the attacker is “right-wing” or “left-wing,” “Communist” or “jihadist,” “anti-government,” “pro-militia,” etc. Surely these are truncated categories to the point of being cartoonish, but despite these limitations, contextual data surrounding political attacks against the state are often not available. When such narratives are located, they routinely are penned by either the direct producer of violence (e.g. the one sending the mail bomb) or the recipient entity (e.g. the Office of the Prime Minister). From both perspectives, inflated, bombastic, and misleading description can be employed to craft simple narratives from complex events.

One of the explanations for fantastical explanations for significant events – like the US’s assassination of Osama bin Laden – can be found in the study on conspiracy theories and narrative. In a 2014 study published in the American Journal of Political Science, the authors explain:

[Americans have a] natural attraction towards melodramatic narratives as explanations for prominent events – particularly those that interpret history [in terms of] universal struggles between good and evil … For many Americans, complicated or nuanced explanations for political events are both cognitively taxing and have limited appeal. (Jacobs 2014)

This sort of logic can not only explain the difficulty in distinguishing falsehoods from truths in an age of unprecedented information availability, but also the challenge of pushing discussion of political violence towards an arena of nuanced, well-informed, and engaged analysis. It is much easier – and more dramatically appealing – to present clandestine revolutionaries as caricatures of themselves; to reinforce old tropes of the bomb-throwing anarchist hiding around the corner.

Arsonist theorists and “primitive rebels”

In developing political theory as derived from communiqués and other claims of responsibility, it is important to note the revolutionaries’ tendency toward “organic intellectualism.” Antonio Gramsci, the Italian Marxist, offers this concept, writing, “all men are intellectuals … but not all men have in society the function of intellectuals … Everyone at some time fries a couple of eggs or sews up a tear in a jacket, we do not necessarily say that everyone is a cook or a tailor” (1971b, 9). In this manner, the production of high theory through non-academic, non-traditional settings is commonplace in the activist-academic community, as well as from activists “in the streets.” Sandra Jeppesen (2011, 151–152), an anarchist academic, speaks to this tendency writing:

Among anarchists there are many “organic intellectuals” who produce theory and action in written and dialogical texts that are not primarily academics, including zines, blogs, workshops, teach-ins, counter-summits, Indymedia web sites, and other anarchist spaces … Thus, in considering post-anarchist[5] theory, we need to extend that space that we investigate as post-anarchist or we risk seeing only a partial picture that looks neither beyond the male European classical anarchists to contemporary anarchist thinkers … [and] current social movements in which anarchists are playing agenda-setting roles.

This “theory and action in written and dialogical texts” is part of a larger anarchist pedagogy based in developing ephemera, theory, and intermovement histories. Another way to think of these extra-academic knowledge products is that of “guerrillas texts” described as “irregular non-uniform anti-authoritarian texts combating a much larger normalized authoritarian system of textual production that tends to be capitalist, patriarchal, heteronormative, racist and/or ableist” (Jeppesen 2010, 473). Therefore the anonymously-authored texts that make up the object of analysis throughout this book can be understood as not only the products of anarcho-organic intellectuals, but texts which are in themselves “subterranean at times, like manifestos, zines or direct action communiqués, breaking out as ‘surface extensions’ in many directions, like books by independent publishers or pamphlets distributed at protests” (Jeppesen 2010, 474).

While discussing the histories, action, and ideas of a social movement, one inherently adapts an often unspoken framework that influences the construction of arguments and the ordering of events within a politicized logic. It is therefore important to attempt a transparent process when constructing histories, and it is equally important to point out when others are not meeting this standard. There is an inherent subjectivity hidden within historical interpretation, and when one’s history prejudices one against an even-handed analysis of a subject, this bias should be acknowledged. I have attempted to do this by engaging as an “anarchist academic,” publishing this book within a series on anarchism. I have not hidden my affinity for anarchism’s critiques nor associations with anarchist movements.

To cite a counter example of a foundational, social movement text which is at odds with the present discussion, we can examine historian Eric Hobsbawm’s 1959 book, Primitive Rebels: Studies in Archaic Forms of Social Movement in the 19th and 20th Centuries. In this book, Hobsbawm (1971, 2) develops the archetype of the “primitive rebel,” which he describes as a “pre-political … blind and groping” mass of individuals struggling from poor and/or rural areas in a battle against domination.[6] Hobsbawm speaks deploringly of these masses and their agitation, thus earning them the apolitical term primitive and the slightly less despairing term, rebels. Hobsbawm speaks of “social bandits,” best understood though the Robin Hood (1971, 4, 13–27) character, who emerge from the masses to carry out illegal acts against those in power in an attempt to redistribute wealth and control to the poor and marginalized. While one may find such character portrayals admirable, Hobsbawm deplores them as having “next to no organization or ideology … totally inadaptable to modern social movements” (1971, 5).

Hobsbawm’s criticism reaches beyond his rejection of Robin Hoodstyled banditry, and the primitiveness of unorganized mobs, and appears overly despairing of a political and social framework the author found counter to his own. Hobsbawm’s portrayal of spontaneous, collective violence, such as riots, has been called “anti-class struggle” (Young 2001, para. 30), as critics accuse this bias of existing “at the heart of all his written work as a labor historian.” This is largely due to Hobsbawm’s expressed preference for social change through organized labor (i.e. union activism) and his dismissal of “the spontaneous militancy of primitive rebels, bandits and … working-class militants” (Young 2001, para. 23). These later methods of contestation are seen as un-political, inherently unsuccessful, and thus largely irrelevant in the historical record outside of demonstrating their unsuccessfulness.

Hobsbawm explicitly addresses anarchist militants, focusing on those active in the Spanish Civil War of the 1930s. Despite the establishment of collectivized, anarchist-styled lands, trade unions, factories, social services, organizational bodies, and militias occurring in conjunction with a highly asymmetric war against the fascists of Francisco Franco, Hobsbawm laments the militants’ efforts, writing: “anarchism was and is helpless … Nothing is easier than illegal organization in a unanimous village … but when the millenarian frenzy of the anarchist village subsided, nothing remained but the small group of the … true believers” (1971, 91). This portrayal stands in contrast to the findings of other scholars (Bookchin 2001; Peirats 2011) specifically examining the anarchist experiment in Revolutionary Catalonia. In typical accounts, scholars have concluded that its failure was not the fault of anarchism but rather of reformist efforts on the left and direct repression from the right. Hobsbawm later writes, in reference to Revolutionary Catalonia, “anarchism is thus a form of peasant movement almost incapable of effective adaptation to modern conditions … thus the history of anarchism, almost alone among modern social movements, is one of unrelieved failure” (1971, 92).

Hobsbawm’s prediction for mass-based organized labor and his rejection of anarchism’s “spontaneous and unstable rebelliousness” (1971, 92) is obviously influenced by his efforts in conjunction with the German Communist Party which he joined in 1931, the Communist Party of Great Britain which he joined in 1939, and his consistently vocal support for Joseph Stalin’s Popular Front (Young 2001, para. 4). Hobsbawm assumes in his method of argumentation that socialist-inspired forms of organized labor consistently led the charge for reform, and that forms of resistance from the “inarticulate” (1971, 2) are meaningless. This stands in obvious contrast to the insurrectionary position that favors the spontaneity, antireformist, and unorganized nature of mass revolt and struggle and rejects the glorification of “workerism” and “workerists.”[7] Additionally, Hobsbawm’s criticism of loosely assembled, spontaneous outbursts of anti-state anger (i.e. riots) as lacking merit represents one side of a debate, with insurrectionary-sympathetic writers, on the other side, often speaking of the potential strengths of these types of outburst.

This discussion of Hobsbawm is meant to partially unearth the political subjectivities that inform our collection and interpretation of historical data. Certainly one cannot escape their own subjectivity, especially in matters of historical interpretation as read through politics. Therefore I would be remiss to avoid noting that my own reading of history, the reading of history contained herein, is understood through my embracing of the anarchist tradition. As Hobsbawm was in favor of large, mass-based forms of protest by organized labor, this was likely the result of his positive experience with such movements for socialism. However normal this appears, it becomes problematic when Hobsbawm uses this position not only to speak of the possibilities contained in Stalinist socialism, but the child-like sensibilities of those who operate with more fluidity and less predictability. For Hobsbawm, these rioters, peasant insurgents, social bandits, and illegalists are the short-sighted, illogical, non-strategic masses, and it is only through the centralism of Communism that one can effectively wage such battles. As a result, Hobsbawm’s notions of social change do not align with that of his subject and, as a result, he tosses them aside. Noting the failures of Hobsbawm, the current examination of insurrectionary anarchism is not meant to inscribe this author’s anarchism atop the subject; to judge its successes or failures with strategy or message and offer a complementary or critical alternative. Rather the intent here is to explore insurrectionary theory through its own framework, which while informed by anarchism at its roots, embodies a new articulation of its own ilk.

New methodologies of critical inquiry

What’s on trial is the option of armed struggle against the murderous machine of power. Today, anyone who does not understand the necessity of armed anarchist action against the tyrants of our life, is either extremely naïve or a cop … Our voices and ideas are more powerful when they come from the barrel of a gun. (Economidou et al. 2016)

The exploration of radical political actors can serve a variety of functions. One can analyze patterns of attack and target selection for the creation and refinement of methods designed to identify, disrupt, and capture combatants. Conversely, one can examine the lived realities that produce combatants and seek to analytically apply these criticisms to subjects as grandiose as structural violence (Galtung 1969). This book is most certainly the second form of inquiry. In doing so, the analysis begins from the fields of Peace/Conflict Studies, not International Relations, and leans towards anarchism and poststructuralism (i.e. post-anarchism) rather than realism or neoliberalism. This is not to claim ideological blankness, but rather to assert my a priori framework. If one were to pursue the study of political violence through the preeminent field of Terrorism Studies, emboldened by the boom in scholarship post-9/11, then one would likely investigate how best to secure the homeland from attackers, and in doing such “agenda setting” (M. Crenshaw 1990, 17), present the subject as one of securitization, not investigation (Jackson et al. 2011, 13). This manner of scholarship has been critiqued for its avoidance of empirical measures to study terrorism. When counterterrorism is the focus, such a pattern is even more striking, as according to one study (Lum, Kennedy, and Sherley 2008) “only 3 percent of articles from peer-reviewed sources appeared to be rooted in empirical analysis” (Biglan 2015).

In their discussion of “the terrorism industry” the authors of Terrorism: A Critical Introduction cite the failure in scholarship embodied in traditional/ orthodox Terrorism Studies.

… the orthodox terrorism field has developed a long-term material interest in the maintenance of terrorism as a major public policy concern … [and] in order to protect its privileged position, the field has developed a number of subtle gate-keeping procedures which function to ensure that scholars or critics who do not share dominant views and beliefs are marginalized and denied access to policymakers and the main forums for discussion. (Jackson et al. 2011, 13)

Such a demarcation has been developed to separate research on political violence associated with securitization and counterterrorism, and that which establishes other aims. To borrow again from the book’s authors, in attempting to separate oneself from this trend, they define traditionalist scholarship as that which embodies “the failure to recognize that ‘terrorism’ is a label given to acts of political violence by outside observers, and that the designation of what constitutes terrorism has historically changed according to political context” (Jackson et al. 2011, 15).

Scholarship examining social movements, including those movements that challenge through force, is essential, yet must be carried out apart from the discourse on securitization found prevalent in Criminology (orthodox) Terrorism Studies and Security Studies. This securitization focus limits the types of scholarship that is produced. In the preface to their multivolume exploration of Germany’s Red Army Faction (RAF), the authors write:

We felt our work was unique, as English-language studies of the RAF were almost uniformly written from a counterinsurgency perspective, the goal being to discredit the guerrilla and to deny it any recognition as a legitimate political force; in short, to deprive us of its history. (Moncourt and Smith 2009b, 2:XVI)

It is precisely this notion that has motivated the subsequent examination of insurrectionary texts. While very little scholarship addresses this milieu at all, that which does focuses on securitization (Marone 2014) and sensationalism (Hanrahan 2013; Winfield and Gatopoulos 2010), presenting a broad and diverse social movement as a secretive conspiracy of inter-linked and orchestrated actors.

In order to interrogate this understanding of this portrayal, one must first establish what is meant by a movement, and more specifically, a (radical) social movement. Political theorist Daniel Koehler offers a definition of “Radical Social Movement[s],” building off the concept of a “social movement” as defined by Sociologist Mario Diani (1992, 13). Koehler’s (2014, 4) defines radical social movements as:

Networks of informal interactions between a plurality of individuals, groups and/or organizations having the character of a counterculture with the primary goal to influence (positively or negatively), fundamentally alter, or destroy a specified target society on the basis of a religious or political ideology, using all available means, legal and illegal, including the strategic use of violence, to fulfill and realize the ideologically corrected or purified version of the target society.

This description bodes well for the current study, as in reality the insurrectionary model is a tactical and strategic sub-trend within a much larger social movement against the state and capital. Though some scholarship has sought to describe non-state actor networks as akin to “countercultures” where individuals “associate with each other through shared definitions of what is wrong with the status quo and where to look for a better alternative” (Hemmingsen 2014, 7), as insurrectionary action is the sum total of a variety of transnational counterculture networks, it is best understood as a movement which draws its constituency from a variety of cultures, both mainstream and counter. It is bound by shared politics as well as overlapping, associated social circles. This social aspect separates it from the authoritarian, militarized conflicts mobilized at the community level (e.g. ethno nationalist/diaspora communities, separatist movements) and enforced through regimented fighting forces, broad-based social service provision, and participation in the political sphere. In this manner, it is more RAF than FARC,[8] more Weather Underground Organization (WUO) than PIRA, despite frequent portrayal to the contrary. In other words, while these latter examples (i.e. FARC and PIRA) maintain networks of fighters that may drain supporters from larger social networks, the organizations are firmly integrated into the society through more dominant institutions such as formalized paramilitary brigades, direct service provision (e.g. education, healthcare), and interaction with state-level politics.

While scholarship (both academic and state) has been keen to analyze the internet activities of violent non-state actors such as those affiliated with the global jihad (e.g. National Coordinator for Counterterrorism 2007; United Nations Office on Drugs and Crime 2012; von Behr et al. 2013; Drissel 2014; Klausen 2014; Torres-Soriano 2014), little attention has been directed at similar online outreach and organizational efforts by those challenging the state at a more fundamentally existential (and secular) level.

This has created a noticeable gap in the literature. Though the precise cause for this exemption is unclear, it is likely influenced by the various venues of conflict. In the majority of cases, insurrectionary political violence occurs outside of the “traditional” physicality of the exoticized and Orientalist (Said 1979) “East” (e.g. Afghanistan, Pakistan, Iraq, Syria, Palestine, Iran, Somalia …) but rather in largely “Western” nation-states (e.g. US, UK, Spain, Italy, Sweden, Greece, Argentina). In other words, while traditionally terrorism is something done to the West by a sub-state, subaltern[9] (Gramsci 1971a, 202; Spivak 1988), Oriental actor, insurrectionary violence is often located and produced by the so-called First World. In the present discussion, this seemingly unnatural turn away from the Arabian battlefields has likely contributed to the scant examination of insurrectionary violence in traditionalist Security and Terrorist Studies discourses.

This may also be due to unfamiliarity and discomfort with discussing violent outbursts outside of standard explanatory frames – lack of political opportunity, authoritarian political regimes, abject poverty, and religious fanaticism. In other words, it may be precisely because of the insurrectionary critique that its actions are not examined; as to assess its “findings” could serve to challenge the nature of power which establishes the legitimacy of the scholarship and knowledge construction. This sort of (often avoided) approach functions to focus the readers’ attention toward structural criticisms such as rejections of the nation-state, capitalism, eco-cide, speciesism, patriarchy, militarism, and the like. There is of course exemplary scholarship examining the insurrectionary tendency and, although scant, these works must be recognized. Many are the product of insurrectionary proponents (e.g. CrimethInc. Ex-Workers’ Collective 2009; IEF 2013; Casper/CrimethInc. and Graeme/IEF 2014), anti-authoritarian theorists (e.g. Williams and Thomson 2011; Nomad 2013; Wood 2013; The Institute for the Study of Insurgent Warfare 2014), politically-aligned public events (e.g. Ariel et al. 2014), and traditional (critical) academics (e.g. Noys 2011).

In order to build an analytical model to further explore these networks of non-state actors, I have adopted the frameworks developed within the so-called critical turn in social science analysis: a collective of evolving interdisciplinary fields which have influenced arenas such as poststructuralism, Justice and Peace Studies, Feminist Theory, and elsewhere. While the preceding discussion was meant to describe how one can descriptively establish what a movement consists of, and subsequently where and why that movement’s ideological boundaries exist, these intermediate goals are subservient to a larger methodological task of exploring new manners of critical inquiry adopted from feminist theory, Critical Security Studies (CSS), Critical Terrorism Studies (CTS), and the mixing of these disciplines through hybrid mechanisms such as feminist security studies (Wibben 2011) and human security (Tadjbakhsh and Chenoy 2007).

This book is seeking to incorporate aspects of two broadly inter-related fields, namely that of CSS and CTS. The often linked fields of Terrorism Studies and Security Studies have witnessed a boom following the more generalized rise in university study directed at Islam, political Islam, Islamic terrorism, and Middle Eastern politics following the 9/11 attacks. Subsequently, new approaches have been developed and taxonomized under a host of “critical” fields including Critical Terrorism Studies and Critical Security Studies which attempt to problematize and clarify a methodology for those seeking to investigate political violence and its responses through a non-orthodox, non-realist lens. Recurrent throughout both of these emergent fields is what is often referred to as the critical turn, characterized by (at least) four key components:

1) Social and political life is messy: our analysis must reflect our belief that we cannot identify any single unifying principle in social and political life; methodological pluralism is a hallmark of this belief.

2) Agency – the capacity to act – is everywhere: it can be found in individuals, groups, states, ideational structures, and non-human actants.

3) Causality is emergent, rather than efficient: analyses set out the conditions of possibility for a set of politics, identities, or policies, rather than a single or complex source.

4) Research, writing, and public engagement are inherently political: we understand politics in its broadest sense to mean questions concerning justice, power, and authority; critical scholarship means an active engagement with the world (Salter 2012a, 2).

A great deal of this book’s approach speaks to the first critical component, that of methodological pluralism, as well as issues of agency. However important such components are, I have chosen to adopt a critical framework precisely because of component number four: the inherently political project of research, writing, and public engagement. To this end, CSS begins its pursuit by problematizing the concept of securitization itself, as “no neutral definition is possible” (Smith 2005, 27). This should be understood as a single appeal within a larger set of analytical features such as the critical turn away from knowledge extraction and towards knowledge construction, away from detachment and towards engagement and away from expertise-ism and towards participatory research that engages marginalized knowledge and subjects (Scheper-Hughes 1995; A. Doucet and Mauthner 2006; Blakely 2007; Hesse-Biber 2011). These contributions – largely adapted from feminist interventions in the study of methodology – redefine the venue of research as inherently political; seeking social change by operating at the margins of subjugated knowledge. In their discussion of methodology and epistemology, A. Doucet and Mauthner (2006) state this clearly, noting that a feminist method may not be a distinct approach, though it functions to overlay this emancipatory political project atop knowledge building.

As other approaches do, CSS carries with it a set of proscriptive presumptions including the validity of ethnography and discursive investigations as form of security-themed investigation. CSS diverges from orthodox Security Studies in its validation of the “ethnographic turn” (Salter 2012b, 51–57) and the “discursive turn” (Salter and Mutlu 2012, 113–119), elaborating these tendencies within the field. Concerning ethnographic tendencies within CSS, the framework suggests that respondent “cultures” must be experienced to be understood (Salter 2012b, 56–57) and that even in the realm of studies concerning policing, national security, and statecraft, issues such as reflexivity, critical engagement with “expertise,” and one’s relationship to the security state must be acknowledged and confronted. Questions such as “What constitutes security?,” “Can security have emancipatory functions?” (Alker 2005, 189–213; Toros 2012, 35–40), and “What is the implied narrative in traditionalist conceptions of security?” (Wibben 2011, chap. 4) are indeed relevant at the onset of a research project. Such concerns separate Critical Security Studies from a non-critical method in radical ways of direct relevance to this book. For example, the relationship between knowledge construction and securitization, policing, and intelligence gathering is a tricky collaboration at best.