Miriam Basilio

Corporal Evidence

Representations of Aileen Wuornos

Millie Wilson, in her installation Not a Serial Killer (1994), and Tammy Rae Carland, in her video Lady Outlaws and Faggot Wannabes (1995), critically examine media representations of Aileen Wuornos. Wuornos, who has been classified as the “first woman serial killer” by the FBI, has been on death row in Florida since her 1992 trial.[1] Now aged 39, Wuornos had been a sex worker for most of the seventeen years preceding her arrest in January 1991. Convicted of killing seven men, she testified that she had armed herself with a gun when soliciting clients in response to increasing levels of violence.[2] Wuornos has consistently affirmed the right to self-defense: “I’m supposed to die because I’m a prostitute? No, I don’t think so. I was out prostituting. And I was dealing with hundreds and hundreds of guys. You got a jerk that’s going to come along and try to rape me? I’m going to fight. I believe that everybody has a right to self-defend themselves.”[3] Crucial evidence was withheld at Wuornos’s 1992 trial, which was also compromised by the financial interests motivating certain participants in the case.[4] The TV film Overkill (1992) was made with the collaboration of police investigators and Wuornos’s former lover, Tyria Moore, who made lucrative deals with the producers prior to the trial. Arlene Pralle, who adopted Wuornos after her arrest, soon began earning money from talk show appearances, print interviews, and a lurid true-crime paperback book.[5] The case has become a sensationalized media spectacle in a climate of anxiety about the assignment of gender roles, the ostensible causes of homosexuality, the definition of sexual harassment, rape and self-defense, and the causes of economic decline.

Most feminist, gay and lesbian, and prisoners’ rights organizations have not become involved in Wuornos’s trial and appeals process.[6] Yet the controversial case has been featured in hundreds of newspapers, magazines, and television news and tabloid programs. Representations of Wuornos in print and television media are typical of images of pathologized lesbians that emerged in the nineteenth century, and intersect with gendered and classed terms to reveal deep-seated anxieties about attempts to redefine social and legal categories. Wuornos’s trial followed a number of cases that prompted debates about the categorization of sexual harassment, rape, and battered wife syndrome, in which repeated instances of abuse could justify acts of self-defense.[7] Also polemical were discussions of the growing visibility of lesbians and a renewed interest in the so-called causes of homosexuality. At the same time, the campaigns organized by the religious right targeting gay men and lesbians as threats to the stability of American society coincided with a rise in class polarization and xenophobia.

As with other deeply divisive legal cases such as the William Kennedy Smith rape trial, the Clarence Thomas- Anita Hill hearings, and, more recently, the 0. J. Simpson murder trial, visual artists have also referenced the case in work in a variety of media, including installations, public art projects, videos, artists’ books, and performances.[8] These artists employ diverse strategies to examine the homophobia and gender and class bias imbedded in representations of Wuornos formulated by law-enforcement agents and media commentators; in addition, they characteristically reframe such representations to examine their wider legal and political implications. Wuornos’s case is examined in relation to the high degree of violence against women and the marked disparities in prison sentences for men and women convicted of violent crimes. Also relevant is the criminalization of lesbian and gay sexuality in the United States and its effects on sentencing of defendants identified as homosexual.[9] Wilson and Carland focus on representations of Wuornos to provoke viewers to examine their consumption of media images.

Wilson’s work has consistently explored the possibilities of lesbian representation within the hegemonic discourses of the mass media, anthropology, psycho-analysis, museology, and modernist and postmodernist artistic production. She has also interrogated representations of lesbians that have been formed in large part by pathologizing discourses dating from the nineteenth century.[10] Particularly important for Wilson’s work has been the appropriation and redeployment of photographic images, especially those taken from the media. In her 1989-91 series The Museum of Lesbian Dreams, Wilson problema- tized lesbian identity politics and the exclusion of lesbians from the modernist canon and postmodern theory by suggesting the relationships between systems of classification and related institutions—such as criminology and prisons, and art history and museums.[11]

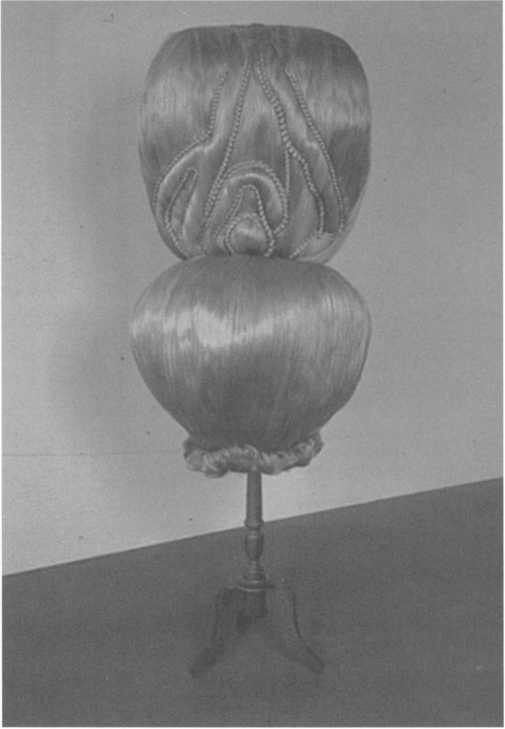

Wilson’s strategy of working with relations between texts and objects in place of explicit representations of the body is evident in the series of wigs titled Merkins. These wigs (merkins) were inspired by and exhibited with a reproduction of a print by Hogarth from 1761 depicting periwigs, which functioned as “symbols of authority” in the eighteenth century, and a medical illustration of lesbians’ genitals from a 1948 text, The Gynecology of Homosexuality. The wigs resemble both Hogarth’s hairpieces and the genitals labeled by a scientist with the names of his lesbian “specimens”: Patricia, Ellen, Gladys.[12] The merkins are displayed on “Donald Judd-inspired [wood] shelves” and are given names corresponding to those in the sexological drawing.[13] Wilson’s extravagant hairpieces destabilize dominant images of lesbian bodies as pathological through parodic strategies of appropriation, substitution, and redeployment.

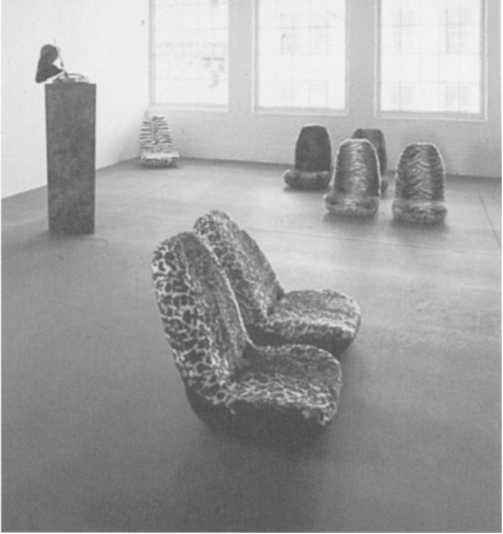

Inspired by media representations of Wuornos, Wilson explores these strategies further in Not a Serial Killer, an installation that disrupts normative categories of gender and sexuality while creating the conditions in which queer readings can take place. A brief discussion of two components of Not a Serial Killer will demonstrate the artist’s double strategy of parodic appropriation that both deconstructs the hegemonic discourses functioning in representations of Wuornos and creates the conditions that allow for lesbian spectatorial positions. Autopsy (fig. 1), seven fake-fur bucket seats displayed as a series, references Minimalist and Pop seriality and repetition while evoking the seven men that Wuornos affirms she killed in self-defense. Wilson’s appropriation of industrially produced objects, such as the bucket seat, satirizes the privileging of Minimalism as a masculinist movement. The use of fake-fur coverings for the bucket seats evokes references to materials associated with Pop art, such as Claes Oldenburg’s fake-fur-covered popsicles, and with queer camp. It also alludes to macho car culture, coinciding with media images of Wuornos as an aggressive, masculinized lesbian by focusing on the motorcycle bar culture in Daytona and the roadside highway exits she frequented in search of clients. Throughout the media coverage of the case, the men she killed were defined by their age, middle-class occupation, and type of car they drove, while Wuornos’s abuse history and marginal occupation and class were cited as evidence of her pathology and inherent criminality. This image of Wuornos’s clients is evident in a pattern- of-killings diagram devised by police in which men were correlated to their cars and highway locations on a map of Florida.[14] In a reversal of the usual positioning of a prostitute as a disposable commodity within the heterosexual economy, the anthropomorphized bucket seats in Autopsy are displayed as interchangeable, replaceable objects. The substitution of objects made of artificial materials for the bodies of Wuornos and her clients also suggests camp strategies of parody informed by revisions of Freudian fetishism.[15] Wilson’s play on Minimalist and Pop seriality and repetition throughout the installation also denaturalizes the essentialist discourses underlying the serial killer category.

Although there have been thirty-five earlier cases of women accused of serial murder, criminologists distinguish these cases from Wuornos’s in feminine-gendered terms such as passivity or nurturance—sexual aggression is considered a trait of male serial murderers.[16] Autopsy alludes to the frequently cited fetishistic tendency of serial killers to preserve objects, often body parts, of their victims as trophies.[17] Criminologists, however, do not address the incongruence between Freudian notions of the impossibility of female fetishism and their inclusion of women into the ranks of serial killers. Prosecutors and most media commentators conflated Wuornos’s presumed job description as a highway sex worker, along with the FBI profile of a (male) serial killer, with the stereotype of the predatory, masculine lesbian.[18] This served to conceal her working conditions, which became far more dangerous when many of her regular clients were mobilized for the Gulf War, leaving her to rely heavily on roadside solicitation. The police and media stress on the singularity of Wuornos as a female serial killer veils both the routine incidence of violence against women and the potential threat embodied in the possibility of women defending themselves.

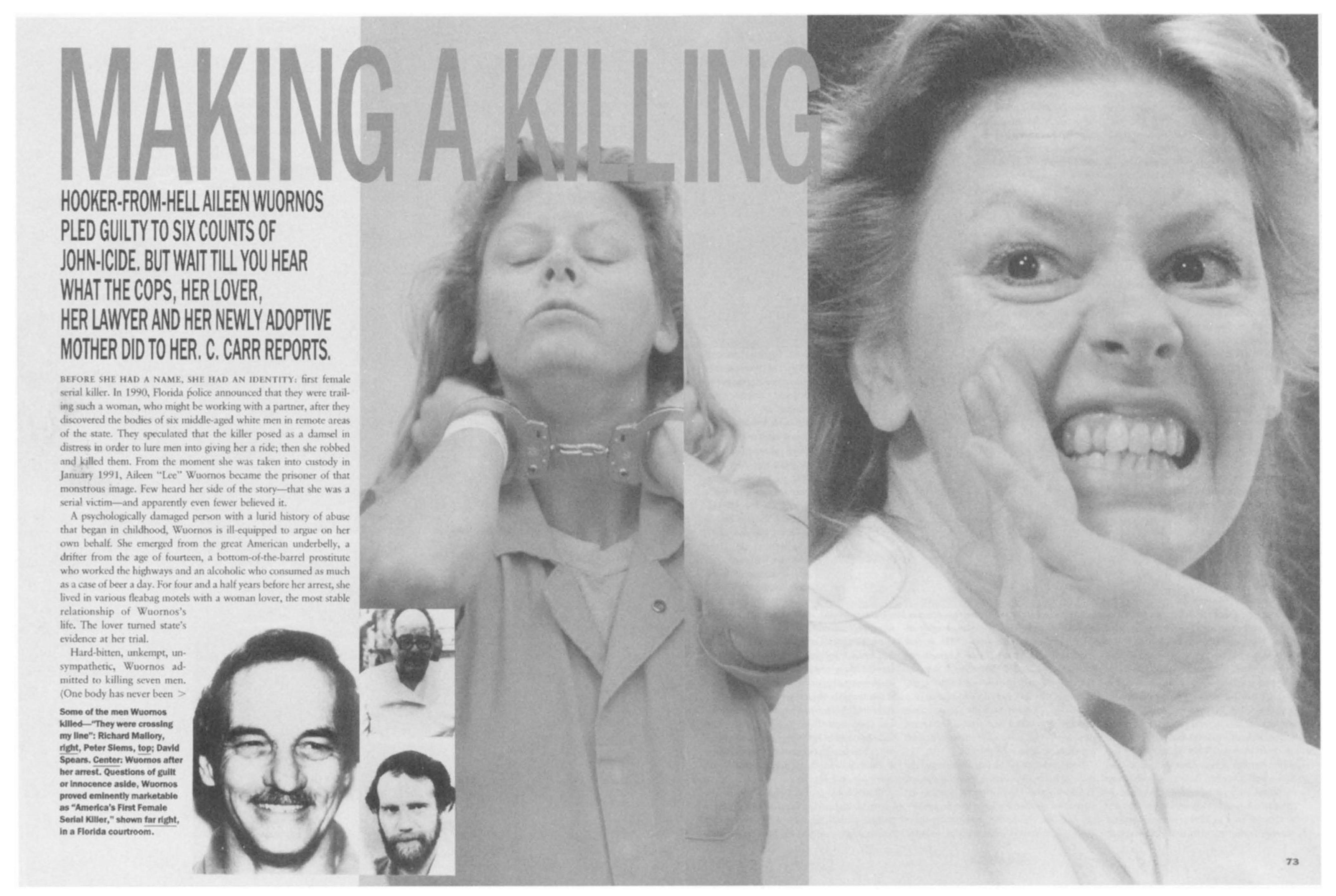

Daytona Death Angel (fig. 2), a platinum-blonde, life-size, synthetic-hair wig, the braiding of which resembles the pubic contours of the Merkins, is linked to Wilson’s interrogation of the functions of pathologizing medical and psychiatric discourses in her earlier work. It is the closest Wilson comes to a figurative representation of Wuornos. Throughout the case, Wuornos has been figured as monstrous, sexually predatory, and uncontrollably violent. Criminologists, lawyers, and journalists hold contradictory ideas simultaneously in their categorizations of Wuornos as a criminal and as a lesbian. Continual references have been made to her working-class family background and physical traits as evidence of her capacity for crime. Underlying descriptions of Wuornos as predatory prostitute and aggressive man hater is the assumption that sex workers and lesbians can be identified by their physiognomy and dress.[19] The strategic application of terms such as mannish or aggressive is evident when descriptions of Wuornos are contrasted with those of Tyria Moore, her former lover. Wuornos and Moore were portrayed respectively as feminine and masculine (or femme and butch) in initial depictions, most notably the police composite issued for their arrests. Once Moore collaborated with the police in obtaining a confession from Wuornos, descriptions of her used feminine terms and stressed her “respectable,” middle-class background despite her stereotypically “butch” appearance.[20] Although an article published in 1994 in Mirabella entitled “Making a Killing” discusses the ways in which financial motives obstructed due process, the case is sensationalized, stressing Wuornos’s abuse history and casting doubt on her sanity.[21] The image of Wuornos as volatile and hostile is perpetuated in the accompanying illustration (fig. 3). Teeth bared, her hand over her mouth to project her voice, her gaze directed at the viewer, Wuornos’s expressions of outrage are merged with the threat of irrational violence. Daytona Death Angel, with its pubic resonances and its evocation of the extravagantly feminine bouffant hairstyles of the 1960s, is a disquieting, parodic image of the pathologized Wuornos presented by the media. Wilson inscribes vaginal imagery into the wigs to reference the threat of castration and its dismissal through fetishism; in this way, she demonstrates the extent to which homophobic constructions of lesbianism have deeply inflected the Wuornos case.

Although the police composite was the catalyst for Not a Serial Killer, Wilson avoids direct representation of Wuornos. Instead, the works in the installation, such as Autopsy and Daytona Death Angel, are presented as artificial tableaux and banal objects displayed in a seemingly detached manner, denaturalizing dominant images that present physiognomy as evidence of lesbian pathology. At the same time, Wilson foregrounds the relation of this imagery to discursive formations of deviance, pathology, and criminality. Wilson’s work resists fixed, stable readings, and the tensions between the cool presentation and the eroticism and humor evoked by her use of materials demands an active role on the part of the viewer.[22] The components of the installation carry associations with some of the emblematic images of the case—some titles (such as Autopsy) mimic the seemingly objective tone of police and media reports, while others echo lurid titles found in sensationalized coverage of the case (Daytona Death Angel). The dissonance between the titles and the objects opens the objects to varied readings, while suggesting the gender and class bias and homophobia that underlie media coverage of the case. Additionally, Wilson made fact sheets, drafted by women’s groups assisting Wuornos with her defense, available to gallery goers, making it possible for viewers to question further their own consumption of media images.

Both Wilson and Carland share an interest in the evidentiary uses of images of lesbians’ bodies by hegemonic institutions, particularly in the use of class position as an indicator of deviance. In Lady Outlaws and Faggot Wannabes, Carland blends appropriated images, fantasy narrative sequences, text, and documentary footage to establish ironic cross-referencing of pathologizing images of lesbians with possibilities for visibility, self-representation, identification, and eroticism. Carland’s decision to portray Wuornos directly is related to her larger project of “attempting] to bridge the gaps between documentary, narrative, and diary video formats.”[23] Four narratives employing the formats listed above respond to Terry Castle’s discussion of “the much-ghosted yet nonetheless vital lesbian subject” in The Apparitional Lesbian: “1. She is not a gay man”; “2. She is not a recent invention”; “3. She is not asexual”; and “4. She is not a nonsense.”[24] Carland contrasts institutional constructions of lesbianism with vantage points that allow for recontextualization of these images and render lesbians’ sexualities and political resistance visible.

The concluding section of Lady Outlaws and Faggot Wannabes blends appropriated footage of Wuornos with a poetic voice-over stressing Wuornos’s subjectivity, through which Carland identifies with her. Three successive lines of text are held on the screen to introduce this segment: “17 of the 42 women on death row are lesbians”; “Lesbianism can be considered an aggravating factor in cases that are eligible for the death sentence”; and “This is a why her, why not me story.” These texts draw attention to the criminalization of lesbian and gay sexuality in the United States.

Like Wilson, Carland was struck by the police composite of Wuornos and Moore, particularly in its written form: “Two W/F’s who appeared to be lesbians [my emphasis] were seen exiting the vehicle and leaving southbound on foot. Subject #1: wearing blue jeans with some type of chain hanging from front belt loop. Subject #2: Very overweight and masculine looking.”[25] Footage of Wuornos (fig. 4) manacled as she is led to a police car, reacting to testimony at her trial and sentencing, and speaking on the stand is slowed down and accompanied by a voice-over. Carland’s voice-over suggests how certain stereotypical notions of class, gender, and sexual orientation served to feed the dehumanized image of Wuornos prevalent in police and news reports:

Every time she swears, swaggers or snarls they take a picture. Her skin is evidence. The way it hangs on her thick bones like gravity prematurely got the best of her. Too much sun and cheap soap. Never enough protection. Her hands are evidence. Hands that have trailed the bodies of women—looking for the place that makes breath halt. . . . The chain that hangs from her belt loop is evidence. Low and on the left.

Carland’s substitution of the voice-over for the footage’s original audio and her altering of its temporality strategically realigns the appropriated images with her text and provokes the viewer to question the seamless objectivity of news reports and documentaries.

Mass-media representations of Wuornos may be viewed as attempts to contain threats embodied in redefinitions of social and legal categories. The use of Wuornos to redefine the category of criminal deviance known as the serial killer to include women occurs at a time when women’s greater social mobility is causing anxiety in conservative sectors of American society. Wilson’s Not a Serial Killer and Carland’s Lady Outlaws and Faggot Wannabes make it possible for viewers to examine their reception of media images of criminalized lesbians. These works serve as a reminder that the effects of gender and class bias and homophobia in the legal system and the media affect all women, gay men, and lesbians. Representations of Wuornos pose the questions: What types of women are credible rape victims? Who can be raped? What types of lesbians are acceptable or easily assimilated? In what situations is self-defense applicable?

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank the editors, as well as Robert Lubar, Linda Nochlin, and John Farmer, for their helpful comments and suggestions.

MIRIAM BASILIO is a doctoral candidate at the Institute of Fine Arts, New York University.

[1] Michael Reynolds, Dead Ends (New York: Warner Books, 1992), 238.

[2] Numerous studies have documented the incidence of robbery, assault, rape, and murder against sex workers; street and highway prostitutes face the highest risk of violence. See Victoria Brownworth, “Crime and Punishment,” QW (October 25, 1992): 24-27; and Phyllis Chesler, “A Woman’s Right to Self-Defense: The Case of Aileen Carol Wuornos,” in her Patriarchy: Notes of an Expert Witness (Monroe, Maine: Common Courage Press, 1994), 97-102.

[3] Aileen Wuomos, “America’s First Female Serial Killer,” transcript of interview, Dateline ABC, August 25, 1992 (Burelle’s Information Services), 9.

[4] Wuomos was tried in January 1992 for the killing of Richard Mallory and pleaded no contest to the other six charges. Evidence of Mallory’s conviction and incarceration for sexual assault was not presented by the defense at the trial. Additionally, an edited version of her confession—which omitted her numerous assertions of self-defense—was shown to the jury, which also heard evidence regarding the other killings. See Chesler, “A Woman’s Right,” 110-11.

[5] See Dolores Kennedy, On a Killing Day (New York: SPI Books, 1994).

[6] Phyllis Chesler and the Aileen Wuomos Defense Committee, San Francisco, are notable exceptions; see Chesler’s “A Woman’s Right.” Victoria Brownworth has cited reasons for the lack of response: the small number of lesbians on death row and the higher number of cases in which racism or gender bias was a factor affecting sentencing. Another factor may be Wuornos’s class and occupation. Feminist and gay and lesbian activists may also fear that public support of Wuomos may perpetuate negative stereotypes. See “Dykes on Death Row,” Advocate, June 16, 1992, 63-64.

[7] Lorraine Radford, “Pleading for Time: Justice for Battered Women Who Kill,” in Moving Targets: Women, Murder, and Representation, ed. Helen Birch (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994), 172-98.

[8] Installations include Carland’s This Is a Why Her Why Not Me Story (1995); Leslie Ernst, Cathy Greenblatt, and Susan McWhinney’s (Ain’t) Natural History (1993); the Theory Girls’ (Laura Brun and Jennie Currie) Scream (1992); and Wilson’s Lee’s Locker (1995); and an artist’s book by Miranda Maher, Girls! Girls! Girls! Madwomen and Murderesses (1993). Among the performance pieces are Deb Margolin, Lois Weaver, and Peggy Shaw (Split Britches Troupe), Lesbians Who Kill (1992); and the Theory Girls’ If You Were Like the Heroine in a Country and Western Song (1993). Videos include Nick Broomfield’s documentary Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1993); and Annie Wright’s Killer Babe (1994). Two recent exhibitions about murder, violence, and gender have included work that examines images of Wuomos: “Murder As Phenomena,” organized by Rupert Jenkins at San Francisco Camerawork in 1992, and “Deadly Responses: Murder and Suicide by Women,” organized by Betti-Sue Hertz at the Longwood Arts Gallery, Bronx, New York (1996). See Amy Scholder, ed., Critical Condition: Women on the Edge of Violence (San Francisco: City Lights Books, 1993); Rupert Jenkins, “East of Eden: Murder As Phenomena,” Camerawork 19, no. 2 (Fall 1992); and Lynda Hart, Fatal Women: Lesbian Sexuality and the Mark of Aggression (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

[9] See Ruthann Robson, Lesbian (Out)Law: Survival under the Rule of Law (New York: Firebrand Books, 1992); Nan D. Hunter, “Life after Hardwick,” in Hunter and Lisa Duggan, Sex Wars: Sexual Dissent and Political Culture (London: Routledge, 1995), 85-100; and Victoria Brownworth, “Crime and Punishment: Are the Rules of Law Different for Lesbians Charged with Crimes?” in Deneuve, January/February 1995, 58-61.

[10] For discussion of the nineteenth-century formulation of psychiatric and legal discourses of lesbian pathology and criminality, see Lillian Faderman, Surpassing the Love of Men: Romantic Friendship and Love between Women from the Renaissance to the Present (New York: William Morrow, 1981); George Chauncey, Jr., “From Sexual Inversion to Homosexuality: Medicine and the Changing Conceptualization of Female Deviance,” Salmagundi, nos. 58-59 (Fall 1982-Winter 1983): 114-46; and Sander L. Gilman, Difference and Pathology: Stereotypes of Sexuality, Race, and Madness (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1985).

[11] See Terry Wolverton, “Thoroughly Postmodern Millie,” Advocate, no. 564 (November 20, 1990): 70-71.

[12] The term is used by Catherine Lord, “Down There: Toys in Babeland,” Art and Text 46 (September 1993): 30-33.

[13] See Debora Doez Donato, “On View: San Francisco,” New Art Examiner, September 1992, 25.

[14] Reproduced in Reynolds, Dead Ends.

[15] See essays in Emily Apter, ed., Fetishism As Cultural Discourse (Ithaca, N.Y.: Cornell University Press, 1993), 31-61; and Elizabeth A. Frost, “Fetishism and Parody in Gertrude Stein’s Tender Buttons,” in Sexual Artifice: Persons, Images, Politics, ed. Ann Kibbey, Kayann Short, and Abouali Farmanfarmaian (London: New York University Press, 1994), 64—93.

[16] See Chesler, “A Woman’s Right,” 95—97; Mark MacNamara, “Kiss and Kill: Out of Florida’s Recent Wave of Horrific Crimes Comes a Dark Version of Thelma and Louise in a Rare Case of a Female Serial Killer,” Vanity Fair, September 1991, 91—106; and Candice Skrapec, “The Female Serial Killer: An Evolving Criminality,” in Birch, Moving Targets, 241-68.

[17] Skrapec distinguishes a subcategory of serial killers who are driven by sexual motives and preserve “‘souvenirs’ of the murders in the form of personal items or body parts” that “become stimuli for later masturbatory fantasies.” See “The Female Serial Killer,” 246.

[18] For instance, Skrapec has attributed the recent increase in female serial killers to the greater social mobility and sense of entitlement created by the feminist movement. She cites Wuornos as typical of women serial killers whose “growing sense of entitlement,” joined with outward expressions of anger, transformed her from “prey” to “predator” (“The Female Serial Killer,” 260-62). Police, prosecutors, and most media coverage depicted Wuomos as a predatory prostitute luring unsuspecting men to their deaths. See Reynolds, Dead Ends; and Dolores Kennedy, On a Killing Day.

[19] See Joan Nestle, “Lesbians and Prostitutes: A Historical Sisterhood,” in Sex Work: Writings by Women in the Sex Industry, ed. Frederique Delacoste and Priscilla Alexander (Pittsburgh: Cleis Press, 1987), 231-47.

[20] See Kennedy, On a Killing Day, 12-23; and James S. Kunen et al., “Florida Cops Say Seven Men Met Death on the Highway When They Picked Up Accused Serial Killer Aileen Wuomos,” People, February 25, 1991, 5.

[21] C. Carr, “Making a Killing,” Mirabella, March 1994, 72-77.

[22] Wilson has described this relationship to Minimalism in her work, specifically the piece A Disturbing Emotional Coloring from The Museum of Lesbian Dreams series: “The language is hot but the look is cool.... I place a sign for deviant femininity on top of something that looks like a well-behaved Minimalist statement.” See David Hirsh, “Lesbian Dreams,” New York Native, April 20, 1992, 45.

[23] Tammy Rae Carland, Lady Outlaws and Faggot Wannabes (1995), published in College Art Association Abstracts 1996 (New York: College Art Association, 1996), 57.

[24] Terry Castle, The Apparitional Lesbian: Female Homosexuality and Modern Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 1993), 8, 10, 12, 13.

[25] Reynolds, Dead Ends, 59-60.