Nancy Gibbs

Mad Genius

The Odyssey, Pursuit, and Capture of the Unabomber Suspect

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND CORPORATIONS

So Many Answers, So Many Questions

INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY AND ITS FUTURE

THE PSYCHOLOGY OF MODERN LEFTISM

DISRUPTION OF THE POWER PROCESS IN MODERN SOCIETY

INDUSTRIAL-TECHNOLOGICAL SOCIETY CANNOT BE REFORMED

RESTRICTION OF FREEDOM IS UNAVOIDABLE IN INDUSTRIAL SOCIETY

THE ‘BAD’ PARTS OF TECHNOLOGY CANNOT BE SEPARATED FROM THE ‘GOOD’ PARTS

TECHNOLOGY IS MORE POWERFUL SOCIAL FORCE THAN THE ASPIRATION FOR FREEDOM

SIMPLER SOCIAL PROBLEMS HAVE PROVED INTRACTABLE

Front Matter

A Reign of Terror Begins

When the parcel arrived around 4 p.m. in the ground-floor mail room of Northwestern’s Technological Institute, Crist saw immediately that the handwriting was not his. After his secretary confirmed that it wasn’t her penmanship either, Crist was troubled enough to alert campus security to the mystery bundle, which through the brown wrapping felt like wood. Campus police officer Terry Marker was dispatched to the mail room, and as a handful of curious onlookers, Crist among them, craned their necks, Marker joked, “O.K., stand back.”

Boom!

ATTENTION: SCHOOLS AND CORPORATIONS

WARNER books are available at quantity discounts with bulk purchase for educational, business, or sales promotional use. For information, please write to SPECIAL SALES DEPARTMENT. WARNER BOOKS, 1271 AVENUE OF THE AMERICAS, NEW YORK, N.Y. 10020

Title Page

Mad Genius

THE ODYSSEY, PURSUIT,

AND CAPTURE OF THE

UNABOMBER SUSPECT

AWARD-WINNING JOURNALISTS

Nancy Gibbs, Richard Lacayo, Lance Morrow, Jill Smolowe, and David Van Biema with the Editorial Staff of TIME®Magazine

BOOKS

A Time Warner Company

Publisher Details

If you purchase this book without a cover you should be aware that this book may have been stolen property and reported as “unsold and destroyed” to the publisher. In such case neither the author nor the publisher has received any payment for this “stripped book.”

WARNER BOOKS EDITION

Copyright © 1996 by TIME magazine

All rights reserved.

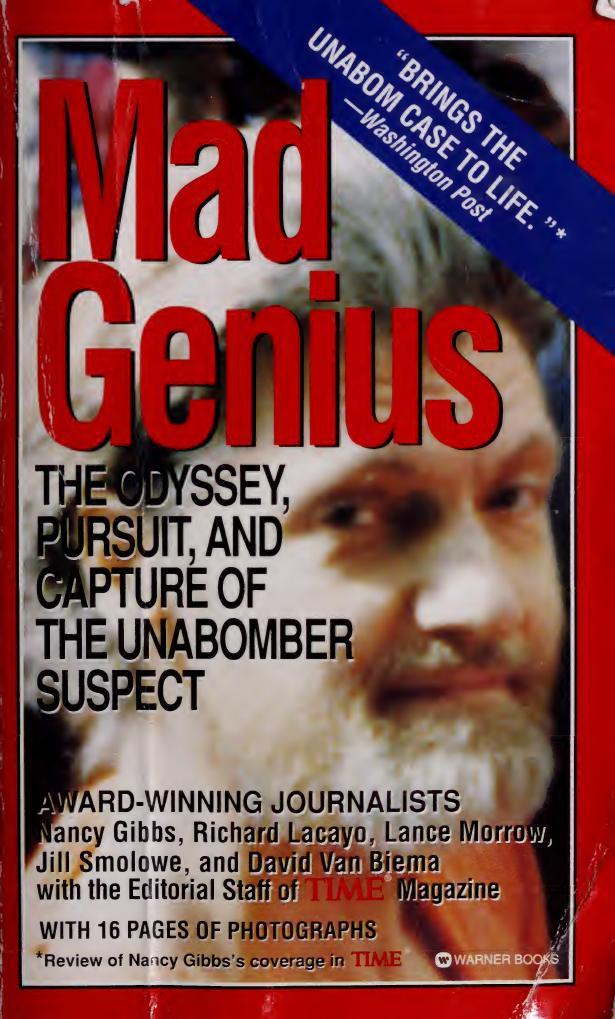

Cover design by Diane Luger

Cover photograph by Michal Gallacher-Missoulian Gamma Liaison

Warner Books, Inc.

1271 Avenue of the Americas

New York, NY 10020

Visit our web site at

A Time Warner Company

Printed in the United States of America

First Printing: June, 1996

10 987654321

Acknowledgments

When major news breaks, it is standard procedure at Time magazine to dispatch correspondents and photographers to remote places, gather vast amounts of research material and assign writers and editors to pull together accounts that enhance our readers’ understanding of often complex events. Typically the journalistic bounty that results from these group efforts is winnowed down to a relatively small number of pages that present only the pick of the informational crop.

On rare occasions, however, the harvest is too bountiful, the tale too compelling, to contain in magazine format. So it is with the story of the Unabomber, the 18-year reign of terror, the Herculean task of hunting down the perpetrator and the arrest of the suspect, Theodore John Kaczynski, on April 3, 1996. When Walter Isaacson, Time’s managing editor, called Warner Books president Laurence Kirshbaum and Warner Paperbacks publisher Mel Parker a week later to propose the idea of expanding Time’s cover story on the arrest to book length, the magazine’s correspondents and reporters were already sitting on a trove of facts and knowledgeable contacts. With Warner Books’ ready decision to publish the full saga, our journalists returned to their original sources, as well as to a host of new ones uncovered in the wake of Kaczynski’s arrest.

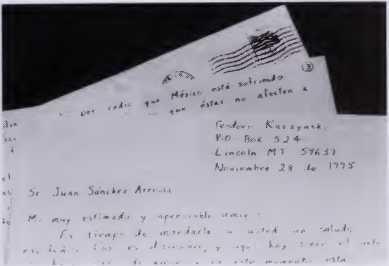

Central to the reporting for this book were: Washington correspondent Elaine Shannon, who covers law-enforcement agencies for the magazine; reporter Pat Dawson, on the scene in Montana; Midwest bureau chief James L. Graff and fellow Chicago bureau members Wendy Cole and Julie Grace; Detroit bureau chief William A. McWhirter, plus Midwest stringers Sheila Gribben, Mark Shuman, Josh White and Kelly Williams, all of whom combed through the Kaczynskis’ early years; San Francisco bureau chief David S. Jackson, who mined the Bay Area, thick as it was with Unabomber-related material; Los Angeles bureau chief Jordan Bonfante, who with correspondents Elaine Lafferty and Denver-based Richard Woodbury and stringers Anne Palmer Donohoe in Salt Lake City and Ellis Conklin in Seattle probed sites and sources elsewhere in the western part of the country; East Coast-based correspondents Sam Allis, Sharon E. Epperson, Jenifer Mattos and Elaine Rivera, aided by stringers Mary Beth Warner and Mabel Brodrick-Okereke, who followed the Unabomber’s trail and delved into David Kaczynski’s family life and brother Ted’s career at Harvard. Latin America bureau chief Laura Lopez filed on Juan Sanchez Arreola from Chihuahua. The intimate descriptions of Montana’s topography and natural beauty is courtesy of national political correspondent Michael Duffy, who flees the nation’s capital whenever he can to fish in the state.

In New York, a team led by assistant editor Ratu Kamlani and including chief of research Marta Dorion, assistant editors Ursula Nadasdy de Gallo, Ariadna Victoria Rainert and Susanne Washburn, along with reporters Barbara Burke, Charlotte Faltermayer and Andrea Sachs, reported and culled through voluminous files and other sources. Senior writers Richard Lacayo, Jill Smolowe and David Van Biema, as well as senior editor Nancy Gibbs, then sat down and among them wrote the narrative. The challenge of organizing and editing this considerable work fell to senior editor Lee Aitken.

Copy editing and proofreading a work of this length on an abbreviated schedule was a challenge taken up by copy chief Susan L. Blair, along with Doug Bradley, Bruce Christopher Carr, Evelyn Hannon, Peter J. McGullam, Maria A. Paul, Jane Rigney and Amelia Weiss. Librarians Sandra Jamison, Charles Lampach, Joan Levinstein, Mary Ann Pradt and Angela Thornton gathered additional material to help writers put the story in its full context. Assistant picture editors Bronwen Latimer and Nancy Jo Johnson assembled the photographs that accompany the text. In the end, production editor Michael Skinner managed to pull all the pieces together and deliver a complete package to our colleagues at Warner Books. Start to finish, the book was completed in 11 days, offering readers what we believe is the freshest and most comprehensive account of the Unabomber’s story anywhere.

—Barrett Seaman

Special Projects Editor Time Magazine

Introduction

The medium—a bomb in a package—was his message. It was loud and sometimes fatal, but inarticulate. It signified... what? A nonentity announcing himself to the world. The bombs were what he had instead of a life.

He started sending them in the middle of Jimmy Carter’s term of office. A sort of perverted model of saintly patience, the Unabomber labored at the devices through two administrations of Ronald Reagan and four years of George Bush, then three years into Bill Clinton’s time. Elsewhere in the larger world, the Shah of Iran fell; the Ayatullah Khomeini took his place, ruled in turn and subsequently died; the Soviet Union crumbled and vanished. History went on. The Unabomber stayed in touch with life by mail.

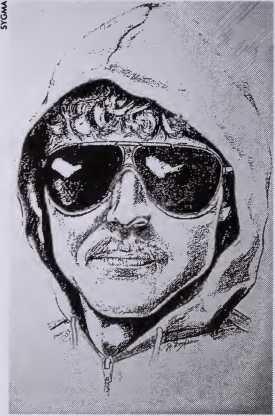

Invisible, but manifest in his works, he would turn up from time to time in the news, like some demon Forrest Gump—not his face of course, but flashes of his labor, his jack-in-the-box violence. When the smoke cleared, all the FBI would be left with was a sketch of his mysterious terrorist-from-the-funny-papers countenance, the mad monk in hood and sunglasses, a post office icon that did not age. Celebrity in obscurity: off and on, he enjoyed more than the usual 15 minutes of fame. His career went on for 18 years, punctuated by 16 packages, by three deaths, by 22 injuries.

Part of the fascination with the Unabomber—before his somewhat pedantic Luddism came into print, anyway—arose from the mystery of his motive. What made his mind tick? Politics? Ideology? Insanity? The bombs were his only meaningful contact with society, until he blackmailed the Washington Post and the New York Times to see his 35,000- word antitechnology tract—his megalomanifesto—in print.

In the end, the case of the Unabomber probably belongs more to the history of sociopathic psychiatry than to the history of political ideas. His private violence bubbled up in a culture of paranoia that has always flourished in America. The atmosphere of inflamed suspicion and conspiracy sighting has grown more virulent at home in the years since the cold war ended. Where once the American paranoid impulse had the entire Soviet Union and world communist threat to occupy it (and the threats were real enough), it now can shop around in a multicultural supermarket of bad guys (the government in general; the Internal Revenue Service; the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms; Exxon; technology as a whole; angry white males; television; secular humanists; homosexuals; Fundamentalist Christians; the radical right; Rush Limbaugh; the media; feminists; immigrants; blacks; liberal Democrats; conservative Republicans). The bazaar of available enemies looks like the bar in Star Wars. As that successful paranoid Mao Zedong once advised, “Let a hundred flowers bloom. Let a hundred schools of thought contend.”

Paranoia may come in either tribal or private form. It may be an intimate pathology or an aspect of identity politics (racial, ethnic, sexual, for example). In a famous essay in 1965, the historian Richard Hofstadter examined what he called “The Paranoid Style in American Politics.” Hofstadter observed, “There is a vital difference between the paranoid spokesman in politics and the clinical paranoic: although they both tend to be overheated, oversuspicious, overaggres- sive, grandiose, and apocalyptic in expression, the clinical paranoid sees the hostile and conspiratorial world in which he feels himself to be living as directed specifically against him; whereas the spokesman of the paranoid style finds it directed against a nation, a culture, a way of life...”

Still, it is in the nature of the disease that every paranoid aspires to the universal. He sees himself as target of a vast, • malignant conspiracy. Paranoia, after all, is toxic selfimportance—a way of imagining oneself to be at the center of the world; that it is a malevolent world is part of the price the paranoid pays for such attention. You invent powerful, Satanic enemies and then, in response to them, deploy apocalyptic weapons. Such is the dialogue that the paranoid invents to communicate with the world.

American intellectuals have sometimes taken a certain ain’t-we-awful pride in the nation’s tradition of political paranoia. But on the whole, Americans’ freedom has made them comparative innocents in the world. The great stains on American history (slavery and the near extermination of the Indians) represented the brutality of the overdog, matter-of- factly atrocious; they were not caused by paranoia.

Contrast that to the style of Stalin’s regime in the Soviet Union, which was a Masterpiece Theatre of the paranoid. His dinners in the Kremlin went on all night. He would sit at a long table and force his ministers and cronies to drink, hour after hour, while he plotted and probed and flattered and terrified them. At dawn, when their brains were numb with fear and vodka and confusion, the nkvd might lead one or two of them away, without explanation, to be shot. Stalin refracted violent fear through alcohol. That was the physics of paranoia under laboratory conditions: for every action, an opposite reaction. Paranoia induces paranoia, a reciprocal mind game. Stalin’s chronic and possibly psychotic paranoia—his greatest survival skill, by the way—sent waves of perfectly justified paranoia not only through the Soviet victims within his reach but also out into the world that was within his nuclear range.

Or think of politics in the Balkans: almost a millennium of blood-drenched ethnic and religious paranoia, a form passed down the generations through the flawless fiber optics of tribal memory, every offense committed 400 years ago being as real as yesterday.

America is young, but has done its level best to develop a record of persecution-and-revenge fantasies. They constitute the dark underweave of American idealism. The rhetoric was often riper than the Unabomber’s prose. In 1798, for example, the president of Yale, Timothy Dwight, attacked the irreligious Jacobins in these terms: “The sins of these enemies of Christ, and Christians, are of numbers and degrees which mock account and description. All that the malice and atheism of the Dragon, the cruelty and rapacity of the Beast, and the fraud and deceit of the false Prophet, can generate, or accomplish, swell the list.”

An anti-Masonic writer in 1829 called Freemasonry the most dangerous institution ever imposed on man, “an engine of Satan ... dark, unfruitful, selfish, demoralizing, blasphemous, murderous, anti-republican and anti-Christian.” Virulent anti-Catholicism focused for a time on the Jesuits, who, claimed one writer, “are prowling about all parts of the United States in every possible disguise, expressly to ascertain the advantageous situations and modes to disseminate Popery ... the western country swarms with them under the names of puppet-show men, dancing masters, music teachers, peddlers of images and ornaments, barrel organ players, and similar practitioners.”

And so on, through anti-immigrant crusades in the 1920s and McCarthyism in the 1950s.

American paranoias come in waves. The last year or two brought a surge in the dynamic: Ruby Ridge and Waco convinced some that the Federal Government had become an arm of an international conspiracy—probably rooted in the United Nations. A vivid fantasy of blue-helmeted U.N. troops descending in black helicopters to take over the U.S. by disarming its population was passed from modem to modem around the Internet. The president of the National Rifle Association talked about the government’s “jack-booted thugs.”

The mood, which started on the fringes, then began to infect the general population. After the 1994 elections, the newly elected Gingrich Congressmen vowed no compromise. Liberals wrote them down as fascists. The Million Man March of African-American men in Washington, otherwise admirable, provided a platform for minister Louis Farrakhan’s elaborate numerological conspiracies, the very arithmetic of the universe clicking in conspiracy. The Whitewater scandal and the death of Vincent Foster, deputy counsel to the President, persisted in emitting a low-intensity radioactive glow. And of course, an elaborate police plot framed O.J. Simpson for a double murder.

But then the psychology seemed to change, much for the better, as if, for the moment anyway, the wave of paranoia had exhausted itself. The first anniversary of the April 19 Oklahoma City bombing passed. President Bill Clinton had traveled there in his role as national grief counselor. The victims and their families had come at least some of the way in recovering, while farther to the west, in Denver, the trial of Timothy McVeigh got under way.

And in Montana, the man supposed to be the Unabomber was arrested.

—Lance Morrow

The Hermit’s Lair

The majority of people engage in a significant amount of naughty behavior. —Manifesto, paragraph 26

Maybe it wasn’t really so lonely at night in the woods at the edge of Montana’s Scapegoat Wilderness, where the trees sound like a crowd waiting for the curtain to rise. Theodore John Kaczynski lived at heaven’s back door, where the land remained as the explorers had found it, still sealed, unlighted, unwired, resembling most perfectly the place he wanted America to be. It is a place where a man who hates technology and progress and people would have plenty of time to savor the absence of all of them. He could listen to the forest rustle and hum, the larches and ponderosa pines hundreds of years old, hundreds of feet high, the tamaracks and the lodgepoles that totter when the wind rubs up against the Continental Divide. What he didn’t know was that for the past few weeks, the trees were listening back.

The agents and explosives experts were everywhere, disguised as lumberjacks and postal workers and mountain men. They had draped the forest with sensors and microphones, nestled snipers not far from the cabin. Some residents of Lincoln, the nearest town, five miles away, thought the guys they had spotted wearing fbi jackets were there to intercept militia types from Idaho on their way to reinforce the rebel Freemen over in Jordan, 320 miles due east on Montana Highway 200. A Helena fbi agent, known by some town residents, turned up in Lincoln, but locals thought he was there to snowmobile. Some agents staying at the local hotel said they were historians researching old gold mines.

Wayne Cashman, owner of the 7 Up Ranch Supper Club, had seen the agents coming and going for a month; he was told they were on some kind of training mission. They wore green camo pants and a variety of shirts and jackets, heavy hiking or hunting boots and sidearms. By Wednesday, April 3, they had rented all four cabins and 16 motel rooms at the 7 Up. That morning he made them 50 box lunches.

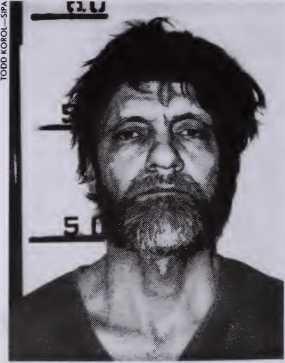

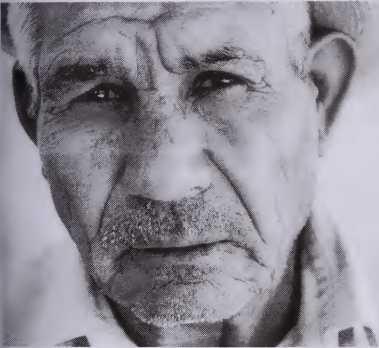

The agents had been asking about the hermit who lived off Stemple Pass Road. But they asked carefully, knowing they were in a small town, where people knew people, word traveled fast, privacy was the local currency. No one could tell them much. Kept to himself. Rarely said much. Didn’t look too great, especially lately, his hair matted, his clothes more ragged, riper even than usual. He came down into town only occasionally, to stock up on flour and Spam and canned tuna at the grocery store, maybe pick up some used clothes or spend the day at the library. He walked with his head down, kept his sentences short, but the voice was still noticeable, a cultivated contrast to his shaggy demeanor. He didn’t say “ain’t,” didn’t say “yeah, right”; he’d say “quite correct.” The dogs in town didn’t like him.

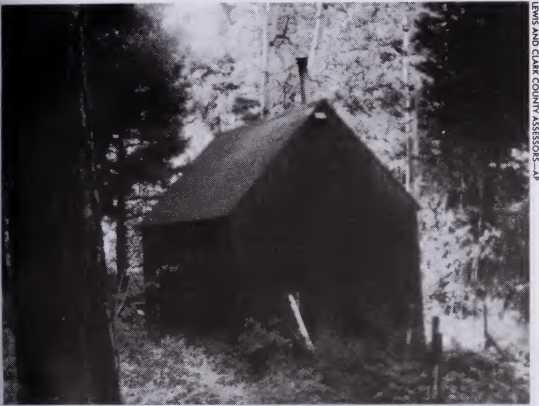

Otherwise he stayed in his cabin up near Poorman’s Creek, a 10-ft. by 12-ft. shack built of plywood and rolled roofing paper, no wires, no water, three locks on the door. It must have got awfully cold in the winter; the snows came early and stayed late, and he hauled and cut his firewood by hand. He hunted rabbits with a .22-cal. rifle, the same kind his father had used to kill himself. A Census worker had stopped by once and actually got inside, saw the stacks of books, the Shakespeare and Thackeray and Victor Hugo, the tools and boxes, the table and cot. Visitors knew better than to knock. But there were never many visitors.

Ted knew his neighbors, like Butch and Wendy Gehring, who ran the local sawmill. He had bought the land, almost an acre and a half, from Butch’s father in 1971. When the agents came to town, they had to tell Butch why they were there, because they rented two nearby cabins from which to keep watch. In fact, so many people knew Ted was being investigated that had he made any close friends whatsoever, in Lincoln or in Helena, he might have been warned, and escaped. Anna Haire at the Helena bookstore said she was amazed that the fbi trusted her and others, because any one of them could have warned him of the closing net. But no one did.

The agents followed Ted’s movements day after day, waiting for the moment when he might emerge, with a parcel in his backpack or in his saddlebags, and head into town, maybe catch a ride to Helena, maybe even board a Greyhound headed south, or west, where they could track him to what they had come to believe were the scenes of his crimes: a post office, a campus, a computer store. But days passed, and there was no sign of him except an occasional foray to tend his garden. One day Butch wandered up by the cabin with a Forest Service worker and called out a greeting to Ted. Ted stuck his head out, recognized his neighbor and waved back. But then nothing.

As it turned out, the agents didn’t have the luxury of time. Word came from Washington: cbs News was about to break a story that the fbi had finally, after 18 years, tracked down a man they suspected was the Unabomber. There had been some tense negotiations as the feds tried to get cbs to hold off, and the network had agreed to wait a day or two. But it was going to run the story, so there was little hope now of catching their man red-handed. They had to get him outside the cabin; he might have guns, it might be boobytrapped, he might decide to kill himself or one of them, or blow up his shack and all that was inside.

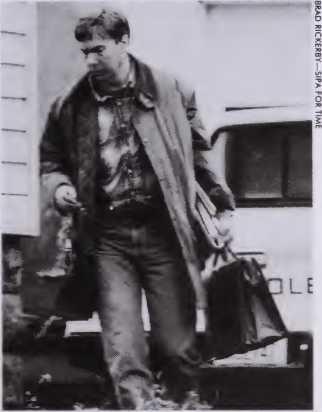

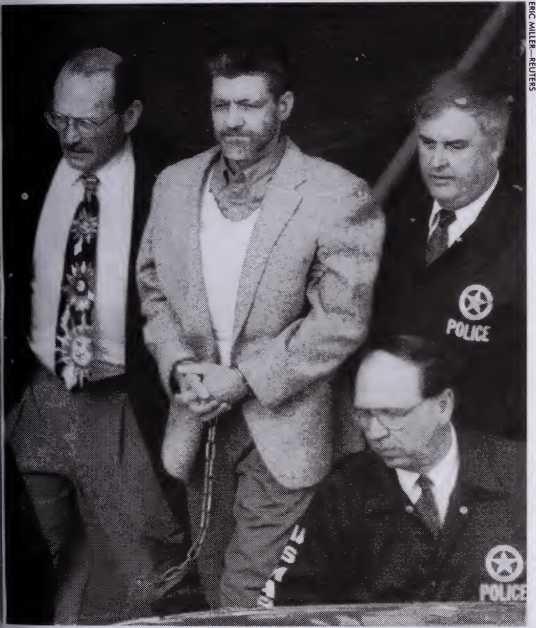

So on Wednesday morning, the same Forest Service official wandered up by the cabin with an FBI agent, holding a map and pretending to be looking for a property line between Ted’s land and the national forest. “Ted,” they called, “We need to talk.” Recognizing the Forest worker from the previous week, Ted opened the door; the air spilled out, dense with woodsmoke and unwashed clothes. The agent then told him who they really were, and that they had come with a search warrant. Ted tried to duck back inside; when the agent and another who had been hiding nearby grabbed him, he tried to shake them off. But he wasn’t much of a fighter, and they quickly had him in handcuffs.

The agents took him to a nearby cabin and started asking questions. Wendy heard what happened next from one of the interrogators. “He would just sit and talk about anything, until they brought up the Unabomber,” she said. “He said he did not want to talk about the Unabomber case. He said he would like to stay in neutral conversation—that he would like to talk about anything but that.”

After about five hours they arrested him. By the time they brought him to the courthouse in Helena, he was wearing a flame orange prison uniform, shackles on his ankles and wrists and a professor’s tidy tweed jacket. The reporters flocked about, shouting questions.

“Are you the Unabomber?” he was asked.

“Are you guilty?”

“Why did you do it?”

And for once he didn’t hang his head. He flashed the sly smile that would jog the memory of many old classmates. But as usual, he didn’t say a word.

The arrest of Ted Kaczynski brought to an end the longest, most expensive hunt for a serial killer in U.S. history. After 200 suspects, millions of pieces of information, thousands of interviews, a million man-hours, 20,000 calls to 800-701- BOMB and visits with clairvoyants, the agents were not about to rush to judgment and declare that he was the Unabomber. But that didn’t keep them from marveling at the finale. For years they had brought all their technology to bear to hunt a man who hated technology. In the end, however, for all their work and patience and skill, it was not a detective story. If Kaczynski is convicted, he will owe his downfall to his own ego and a brother’s honor, without which he might have gone on indefinitely, striking and disappearing again, leaving no trace other than a country reluctant to open its mail.

Among the hunters from the FBI, the U.S. Postal Inspection Service and the Bureau of Alcohol, Tobacco and Firearms, there were agents who retired in frustration after failing to solve the ultimate criminal riddle. What kind of man would launch a career as a terrorist with no interest in personal profit, no obvious personal grudges—some bombs were left for random targets—smart and skillful enough to build by hand untraceable bombs, able and willing, right up until the last year, to remain invisible while the legend around him grew? “It was just an incredibly complicated jigsaw puzzle,” said a former FBI agent who worked on the case.

Over mugs of coffee in the morning, pizza and beer at midnight, the Unabom task force obsessed about his contradictions. He scraped the labels off batteries so they could not be traced, used stamps long past their issue dates and wires that were out of production. But he made his own screws, built his own triggers, even when cheap parts from Radio Shack would have been much harder to trace. When he began taunting his hunters in letters to newspapers, he said he sanded his bombs down to remove not only fingerprints, but also any oils from his hands that might have seeped into the wood.

The agents imagined a smart, twisted man, carving and fiddling into the night. To kill three strangers and injure 22 others, he had to be powerfully angry. Yet he must have had enormous patience to experiment with explosives and triggers and not blow his fingers off. “When you see this stuff, some of these components bear markings of having been put together and taken apart repeatedly,” said Chris Ronay, the FBI’s top bomb expert, who retired in 1994. “It’s not just that he’s creating something carefully. He’s played with it for a while. He marks things with numbers so he can put them together again right. He’s leaving a little of himself at each crime scene.” And each little bit of himself that he left the hunters put into their puzzle. The picture started to focus: a white male, middle-aged, educated, alienated, isolated, brittle, patient, paranoid. And while they got it uncannily right, even in their dreams they could hardly have imagined the life story of the Harvard hermit in the woods.

For years all they had to go on were tiny pieces. A couple of unexploded bombs; remnants of others; some letters to victims. A hair here, a piece of fiber there. But there must have finally come a day when the Unabomber concluded that somehow, his message wasn’t getting through. Maybe he had been too subtle. When news came of the bombing of the federal building in Oklahoma City, that horror and its implications brought the country to a halt while politicians and scholars and the oracles of talk radio examined the state of the nation. The Unabomber had been doing this for 17 years, albeit more discreetly, without anyone but the cops paying attention to the pattern of his targets. The next bomb went off five days later; within weeks the letters and writings poured forth. It all began to look like a last, desperate effort to have a conversation.

“If we had never done anything violent,” the Unabomber wrote in his 35,000-word manifesto, published, after much soul searching, by the New York Times and the Washington Post in September 1995, “and had submitted the present writings to a publisher, they probably would not have been accepted. If they had been accepted and published, they probably would not have attracted many readers, because it’s more fun to watch the entertainment put out by the media than to read a sober essay.” And the message, he believed, was too important to be ignored: industrial society was a plague; it was destroying souls, disrupting community, ravaging nature, ruining the promise of a country in love with its fantasy of the frontier. “In order to get our message before the public with some chance of making a lasting impression,” wrote a man who never was able to make a lasting impression, “we’ve had to kill people.”

The manifesto gave the hunters a much clearer sense of what kind of man they might be dealing with; but only one person could read that treatise, hear its message and recognize the messenger. David Kaczynski knew that his brother was strange, his life a walking warning of danger; Ted had grown bitter, shriveled somehow in isolation. When David read the manifesto, he heard echoes of his brother’s letters and deepest beliefs and confronted the possibility that he was in possession of the greatest secret in modem criminal history.

What exactly was he supposed to do? Tell his mother? Confront Ted? Wait for more proof? Wait for an arm to be blown off, another timber executive to die? David’s decision to launch his own quiet manhunt, and eventually turn his brother over to the fbi, was painfully and perfectly in keeping with the way he lived his life. He was a man with a moral code: blood thicker than water, honor thicker than blood. The agents who swept down on Lincoln, Montana, during Holy Week knew where to go because the brother had shown them the way.

When the investigators arrived at last at the door to the cabin, they were blasted with fumes from the wood stove. Everything was covered with a thick coat of soot. But as their eyes adjusted they saw that they were looking at a mother lode of evidence such as they had hardly dared imagine: books, chemicals, tools, a half-made pipe bomb, 10 looseleaf binders containing detailed diagrams of explosives.

“It’s unbelievable,” said an investigator. “People had speculated he would save all kinds of crap.” But to see it all there, everything the lab guys and the case agents could have wanted, arrayed like Christmas morning... and that was only the beginning. They set up a generator that hummed through the night, providing the lights and power for their equipment. They sent in a 3-ft.-tall robot to handle suspicious- looking boxes. For a command post, they brought in a long motor home with a dish antenna on the roof and an American flag on a pole outside, near the portable toilet. On the first warm spring day, the voices echoed through the timber, with sudden shouts and bursts of excitement, like an after-work softball team jacked to win.

By Friday night they had found a fully functioning bomb, tucked in a wooden box and ready for mailing. “It was wrapped, armed, assembled and ready to go,” said an official. “All you had to do was slap a label on it.” After disarming it, the agents told their colleagues they thought it was unmistakably the Unabomber’s work, as if he had signed his name on the painting.

But there was more, still more. Maps of San Francisco tucked in a Tater Tots box. Wires and switches in old

Quaker Oats containers. A scrap of paper apparently titled “hit list,” with the words “airline industry,” “computer industry” and “geneticists.” He kept his Michigan diploma in a Samsonite case, his high school yearbooks in a green plastic bag. They vacuumed the floor, gathering up fibers and hairs, cataloging the dust bunnies.

The first two typewriters they found looked promising; their bomber had always used the same one, maybe so the feds would know they were dealing with their real terrorist and not some pretender. But the third typewriter was the lucky one. They found it in the cabin’s loft, and nestled next to it, an original copy of the manifesto.

Within a few days the first tourists had arrived—from Costa Rica—to pose by Ted’s mailbox and have their pictures taken. He was down in the county jail, on a suicide watch. For the first time in many years, he was living where he could read by a strong light, shoot hoops in the afternoon sun, use a toilet. For Easter dinner he had ham, scalloped potatoes, peas and carrots, lemon coconut pie and coffee.

As for the investigators, they set out on a new mission. They were sure they had their man; now they needed to build an airtight case against him. All across the country they spread, bearing pictures and tracing patterns: how he got around, where he stayed, who might have seen him near the scenes of the crimes. The meticulous search of the cabin went on for weeks. But even as investigators worked at proving what Kaczynski had done, another examination was already under way, conducted by newspaper reporters and armchair psychologists and a country riveted by the tale of a mad genius in the woods. What they all wanted to know was, Why had he done it? And for that story the clues lay elsewhere, starting perhaps in the backyards of Chicago, with a little boy with few friends and a powerful mind.

A Gifted Child

It isn’t natural for an adolescent human being to spend the bulk, of his time sitting at a desk absorbed in study.

—Manifesto, paragraph 115

One can trace the line of Theodore Kaczynski’s early life on a map. It starts in Illinois, then moves through Massachusetts, doubles back to Michigan and shoots to California. From there it takes him finally to the remote woods of Montana. Whatever else that jagged stripe represents—a philosophical wandering, an interrupted career path—it also marks an attempted escape route from the 20th century itself. The man who would find his way to the Scapegoat Wilderness, one of the quietest spots on earth, was bom in Chicago, another kind of wild place altogether. Though it’s by no means the chief symbol anymore for the overloads of city life—for that we now have New York City and Los Angeles—Chicago is still one of the busiest and most populous cities on earth. And when Kaczynski was bom, in 1942, it was still the Second City, a capital of the industrial world. If you wanted an early immersion in all the glories and predicaments of civilization, you could get it there. You might get that even if you didn’t want it.

Earlier still, in the first decades of this century, when Kaczynski’s parents were coming of age, Chicago was more than the Second City. It was in many senses the First City.

Carl Sandburg’s “City of the Big Shoulders” was the hot center of modernity, the great nexus point where all the vectors of invention, money and industry collided. For Americans it was at the heart of their national enterprises— railways, meat packing, timber—the most economically vibrant spot on the continent. For Europeans it was the very essence of America, the place where their writers and intellectuals came for a glimpse of the future. But with the awe it inspired came the uneasy conviction that its headlong development, in which pollution and squalor went hand in hand with prosperity, held a warning about the dilemmas of progress. Even the British author H.G. Wells, an enthusiastic advanceman for the future, was unnerved by the unmanaged expansion he saw there during a visit. Chicago’s defining characteristic, he thought, was “the dark disorder of growth.”

Kaczynski’s parents arrived there in the decade following the First World War. Both of them were children of Polish immigrants, and they were drawn in part by the city’s well- established Polish-American communities. Theodore Richard Kaczynski had been born in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania. Wanda Theresa Dombek had arrived with her parents from Zanesville, Ohio, a pottery-making center 50 miles east of Columbus. On April 11, 1939, less than five months before the start of World War II, they were married. He was 26; she was 21. The newlyweds found an apartment in a two-story brick house at 4755 South Wolcott Avenue in a neighborhood known as the Back of the Yards.

They loved two things: each other and books. Though at this point neither had a college degree, or maybe because of that, they would never stop learning. All his life Ted’s acquaintances would be startled by the breadth of his reading. He could joke about the Anabaptists, a splinter group among Reformation Protestants, or discourse on politics. His politics were leftish. So were hers. It was Wanda who, everybody said, loved not only to learn but also to teach. In the late 1960s, after their sons were out of the house, she would even earn a bachelor’s degree from the University of Iowa and for two years teach high school freshman English in Geneva, Illinois.

They were also both evidently nonbelievers. Instead of being married in the Roman Catholic Church, the couple exchanged vows before a Cook County judge. “That was highly unusual for a Polish family in those days,” says Norbert Gons, 76, a neighborhood historian. And instead of a parochial school, their eldest son would attend the public Sherman Elementary School on West 52nd Street. Says family friend Keith Sorrick: “The boys were raised Darwinian.” The Kaczynskis real faith was in the secular trinity of the 20th century: reason, learning, progress.

The Back of the Yards was a Polish-American enclave near the bustling and noxious Chicago stockyards. In his book City of the Century historian Donald L. Miller describes how by the 1890s it was “the vilest slum in Chicago.” The only open space was “the hair field,” where hog’s hair and cattle skins were spread out to dry under clouds of buzzing flies. By the time the Kaczynskis arrived the city had made improvements in housing and sanitation, but the Back of the Yards was still nobody’s idea of prosperity. On bad days the local air was vivid with the stench from cattle holding pens and the slaughterhouses.

Yet like many a neighborhood of the working poor, it was also upwardly striving, safe and close-knit. Theodore found a job with a first cousin, Felix, whose storefront sausage factory was well known among the shops that lined South Ashland Avenue. Though the place closed in 1969, old- timers will still tell you that Felix Kaczynski and Sons made the best kielbasa on the South Side. Theodore was just a sausage maker, but he was a thinking man’s sausage maker: at one point he came up with the idea for a new sausage casing that he attempted, without success, to patent.

On May 22, 1942, the Kaczynskis’ first child was bom. They named him Theodore John. To distinguish him from the elder Theodore they would take to calling him Teddy. Instead of going to the nearby Evangelical Hospital, Wanda had given birth at Lying-In Hospital, the maternity wing of the University of Chicago Hospitals. Though farther from their apartment it was South Side’s best facility. Records there show a normal delivery.

Very soon after, however, something may have gone wrong. Investigators involved with the Unabomber case say the family told them that at age six months, Teddy suffered a severe allergic reaction to medication. It led to a hospital stay of several weeks, during which the family has said he was kept in isolation. Hospital rules did not allow his parents to hold or hug him. When he came home, they sensed a change. The expressive and happy baby they had sent away now appeared listless and withdrawn.

When infants suffer the same kinds of allergic reaction today, the customary treatment is steroids, which weren’t available in the early 1940s. Medical practice then prescribed a more complicated regime of ointments and com- j presses. To keep babies from scratching themselves while they healed, their arms might be partially immobilized with cuffs or splints. Some were even bound in a spread-eagle position. If the treatment required hospitalization, there could also be an emotional impact from the effects of isolation. “To be taken away from Mother at six months is very drastic to a youngster,” says Dr. John Kennell of Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland, Ohio, one of the nation’s foremost experts on early childhood development.

“Most hospitals at that time didn’t allow more than weekly visitation for sick children. To a child of that age, a week without Mother’s contact may be totally devastating. They have no appreciation that the abandonment will ever end.”

Within a few years it was apparent that there was something else about Teddy. He was smarter than other kids. When he was six he took a Stanford-Binet IQ test that was administered by Ralph Meister, a friend of his father’s who was a child psychologist. An average score was 100. His was in the range of 160 to 170. This boy would be more than bright. He possessed gifts of a kind that were granted to very few. It only remained to see how he would display them.

Meister still remembers his surprise when one day the Kaczynski boy asked him for a copy of Robert’s Rules of Order. The dry handbook of parliamentary procedure was not exactly a Hardy Boys adventure. But Teddy was always hitting the books, even books that were much bigger than he was. It was a discovery that excited his mother no end. Wanda started a special diary. Each new evidence of his budding intellect was lovingly recorded.

Some time in the 1940s, the Kaczynskis moved to a larger place at 5234 South Carpenter Street. They were still in a two- family house, but this time in a house with yards front and back, on a tree-lined street farther away from the foul air of the stockyards. On Oct. 3,1949, Wanda gave birth to their second child, a boy they named David. Teddy, smart and wary, was seven.

Like many kids he may have reacted coolly to the appearance of a competitor for his parents’ attention. Perhaps very coolly. Decades later, after his arrest, one of his aunts told the Daily Southtown, a newspaper in suburban Chicago, that before David was bom, “he’d snuggle up to me.” But not after, she said. “He changed immediately. Maybe we [paid too much attention] to the new baby, like people do.” If it’s true that Teddy was worried about his hold on his parents’ affection, he also would have known by then how to clinch it. Study. Read. Keep on showing the signs of superior intellect that his mother so proudly recorded in that diary.

In 1952 the Kaczynskis made the leap to the suburbs. Evergreen Park, Illinois, was still partly rural when they moved to the three-bedroom brick colonial on South Lawndale Avenue. Truck farms were tucked in among the subdivisions. Teams of horses plowed the nearby cornfields, and the prairie stretched out at the edge of town. But with the postwar combination of prosperity and the baby boom, Chicago was spilling fast into its nearby surroundings. Like America in general, Evergreen Park was a pastoral setting overtaken by civilization, a place that didn’t live up to its promise to be ever green.

For a while it was the fastest-growing community in the state, exploding from 5,000 people in 1945 to nearly 16,000 in 1953, eventually rising to a peak of 26,000 in the 1970s. In the same year that the Kaczynskis arrived, so did Evergreen Plaza, one of the nation’s first shopping malls. Among its features was an underground conveyor belt that moved groceries from the supermarket to the parking lot, where clerks would carry them to the customer’s car. It was one of those machine-age conveniences that in the 1950s seemed the very image of a bright new tomorrow.

The Kaczynskis were well liked in their neighborhood, despite the fact that in some ways they were a breed apart. In a town with 13 established congregations—Evergreen Park called itself the Village of Churches—the Kaczynskis were considered atheists. They were also liberals, an increasingly rare breed among the socially conservative white ethnics of Chicago and its environs. In the 1960s they would revere the Kennedys and the Rev. Martin Luther King. And detest Richard Nixon.

In later years, when they were living in another Chicago suburb, they occasionally wrote letters to the editor of the ! Chicago Tribune. On Oct. 17, 1988, the paper published Theodore’s letter defending liberalism, “Isn’t it puzzling that lately the ‘L’ word is used so pejoratively?” he wrote. “That the word ‘liberal’ is used to evoke something bad? Here are some things that the liberals have given us: Social Security, later the Social Security colas, federal deposit insurance, unemployment insurance, the right to join or not to join a union, the G.I. Bill (giving educational opportunities to veterans), Medicare and student loans for education.

“By what twist of the imagination can anyone call the above bad? Let us treat the word ‘liberal’ with the respect it deserves.”

The first of Wanda’s two published letters would appear in the Tribune on Dec. 21, 1988. That one defended the embattled Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev, who had cut short a trip the U.S. to rush to the site of an earthquake in Soviet Armenia: “How cynical can some of our political analysts get? To hear on TV their skeptical comments on why Gorbachev left for Russia, cutting short his agenda in the U.S., they suggest that if it were not for political opposition in his country, he would have stayed in New York basking in the limelight, visiting plush establishments, etc. etc. Please let’s give the man some credit for being human!

“Tens of thousands of people were dead, dying or injured in his country. Surely, no matter what, this would take him back home.”

On April 20,1990, Wanda wrote in support of health-care reform, “The most frequent criticism one hears of the Canadian national health plan is that high-tech care is not readily available and that one must wait for elective surgery.

“What is not mentioned is that to millions of uninsured or underinsured people in the U.S., not only are those two aspects of health care unavailable but even primary care and preventive care is out of reach. Are we to deny basic health care to millions of children so that wealthy people can be assured that they can buy expensive medicine quickly and easily?”

But while they might have been more liberal than some of their neighbors, their politics seemed well within the ordinary spectrum. And from the time they arrived in Evergreen Park, the Kaczynskis impressed people there by their kindness and good cheer. When a new neighbor’s home was quarantined for six weeks because their infant daughter was stricken with polio, Wanda regularly left hot meals on their front stoop. Joyce Collis, a classmate of Ted’s who lived next door, says when she came home from school each day, she often saw Wanda outside waiting for Ted. “She would greet me as I came up the walk in the sweetest way.”

The Kaczynskis were familiar figures at meetings of the school board and the pta, and at the Northwest Boosters, a neighborhood organization that got the local streets paved and a park installed. Years before such things became common, Wanda started a neighborhood preschool. And if the Kaczvnskis were smart, they weren’t snobbish. “I remember going over there once and there were stacks and stacks of books, mostly philosophy, that Wanda had checked out of the library,” says Collis. “Wanda said they were being passed around among family members, and that we were welcome to take any of the books home with us. But we really sort of laughed the suggestion off, because they were heavy, heavy reading.”

Next to books, what Ted Sr. loved was the outdoors. He liked gardening, hiking and camping. He used to take the boys into the woods for as much as a week at a time. On some of those trips they would try to live only on whatever they could gather or kill. But he also taught them to love animals. Once he and David came upon a lame rabbit in the nearby woods. They brought it home, where 12-year-old Ted nursed it back to health. Then he took it to the edge of town, where the houses gave way to the open prairie, and released it back into the wild.

But for the Kaczynskis the real focus of their lives was their children. “Wanda and Theodore dedicated practically everything to the kids,” says Dr. LeRoy Weinberg, who lived behind them. “When we had parties, they weren’t the type to let it go, have a drink, dance, live it up a little.” For the Kaczynskis love was bound up with learning. On Sundays there were trips to Adler Planetarium and the Museum of Science and Industry. Neighbors still recall seeing Wanda on the front steps of their house reading to the 1 O-year-old Teddy from Scientific American. “Wanda was a born teacher,” says her neighbor Dorothy O’Connell. “She was bound and determined for those boys to do well.”

And they did well. David was bright too, though not the standout that his brother was. As for Teddy, O’Connell clearly remembers him at age 11 stopping by her house before he left with his parents for a vacation in the Wisconsin woods. Under his arm was his vacation reading: Romping Through Mathematics from Addition to Calculus. A year later, he joined her, his mother and another neighbor in a game of Scrabble. “He beat us all,” says O’Connell. “His vocabulary was something.”

There was something else that everybody noticed about Teddy. He kept to himself. It worried his parents that whenever a car pulled up to the Kaczynski home, he would dash up the stairs to his room. He didn’t like to talk much or to play with other kids. Despite his gifts, he had disciplinary problems in grade school. His parents wondered whether a boy so much brighter than his peers might not feel frustrated in class. As an attempted remedy, he was skipped a grade.

That gave Teddy a curriculum more nearly in pace with his abilities. But as the years went by his shyness seemed to harden into a permanent condition of awkward solitude. He entered his teens with an Elvis pompadour (when his hair was combed at all) and a brown leather briefcase, but few real companions. “He was always a loner,” remembers Weinberg. “When he walked, he stared at the ground.” His neighbor Joyce Collis recalls that “whenever Ted went out, he was almost pushed out the door by his parents.” Her mother sometimes drove her to school and offered rides to the Kaczynski boys. When he got into the car, Ted would offer a curt “Hello,” then sit in silence for the rest of the trip. “I don’t think Ted was able to build a rapport with anyone,” says Collis, “young or old.”

David, who was much more outgoing and had more kids his age in the neighborhood, had an easier time. He was the one you might see playing ball in the yard with his father. His mother once said it made her feel young again to have the house filled with the comings and going of David’s friends. By the time he got to high school Ted never really seemed to have any of his own, even among the other brains, whom some kids made fun of as the “briefcase boys.” As a smart kid in the cliquish world of a ’50s high school, he would have been dead meat even if he hadn’t been so weird. “He had a pocket protector, the whole thing,” says Raymond Janz, a classmate who used to tease him. “We stuffed him in a locker one time just for grins.”

Ted did have a couple of hobbies, however. One of them was wood carving. Give him the right tools, and he could craft beautiful and intricate things, like the sewing box he made as a gift for the 13-year-old daughter of a family friend. That was one of the things about him that would cause some raised eyebrows years later among investigators, who knew the Unabomber had mailed some of his explosive devices in handmade wooden compartments.

One of his other schoolboy pastimes was small-scale explosives. No major bursts, just the little ones that have always happened when you bring boys together with chemistry books. With Dale Eickelman, now a professor of anthropology and human relations at Dartmouth College, he used to “blow up weeds” in an open field. “Ted had the know-how of putting together things like batteries, wire leads, potassium nitrate and whatever,” says Eickelman. “We would go to the hardware store, use household products and make these things you might call bombs. I remember once we created an explosion in a garbage can.”

Wanda once apologized to the neighbors for the noise made by a homemade bomb her son had detonated. Kids remember him setting off a rocket behind the school that rose hundreds of feet into the air. Fascinated by little popping devices called “Atomic Pearls,” Teddy had worked out how to make those too. In his senior year one went off in chemistry class when some kids asked him to provide them with the formula, then they botched the execution. The explosion blew out classroom windows. Classmates recall that he was suspended, but there is no record of it at his school.

Evergreen Park high graduate Margaret (Peg) Attridge Giroux remembers Teddy—or Ted, as he was increasingly called—as a “prankster” who had a crush on Joann Vincent De Young. One time he took an animal skin from the biology lab and put it in Joann’s locker, Giroux recalls. On another occasion, he handed her a “letter bomb, a little wad of paper that exploded when you opened it. Like a firecracker, but not that powerful.” Giroux remembers that Ted always had “a sly smile, like he was saying, ‘I’m pulling one over on you.’ ”

Ted didn’t clam up with everybody. Like many bright kids he could be more open sometimes around his elders. “People say that Ted didn’t talk,” says his neighbor O’Connell. “That wasn’t true. If you talked to him, he would have a lot to say.” Robert Rippey, who taught math and science at Evergreen Park High School, remembers a “wry” Ted Kaczynski. “I never thought of him as gloomy in any way. He was a clean-cut, nice kid.” Rippey always gave him A’s. “What made him special was the way he thought. From time to time, he’d go off and work on problems totally independent from what he was learning in class. He’d take a mathematical proof and find different ways of doing it, without any instruction from me. It’s the hallmark of a truly penetrating mind.”

“I think anyone you talked to who had worked with him would have expected nothing short of extraordinary success,” said Lois Skillen, a high school guidance counselor who took him under her wing. “With some students, I have predicted their demise,” she told the Chicago Tribune. “But with him, never.” Ted’s high school yearbook also shows him participating in four after-school clubs: math, biology, German and coins. Rippey remembers the boy’s excitement at finding a rare copper penny in his pocket change, then happily selling it to his teacher for $75.

During Ted’s freshman and sophomore years he joined the high school band, where schoolmates remember him working away at the trombone. Recollections of his talent vary. First-rate is one. Dutiful but uninspired is another. “He played well mechanically,” recalls Jerome DeRuntz, who played baritone horn. “But it never sounded like music. He did not have a feel for music.” Ever the proud parent, Ted Sr. was a dedicated band booster, recalls Daral DeNormandie, who worked on tag sales with him. “He was like a gentle soul, very much a gentleman,” she says. “He was proud of Ted as can be. He was always talking about him skipping a grade and how intelligent he was. He was just a delight.”

Even so, by high school Ted seemed deeply out of step with his classmates. Paul Jenkins, who taught Ted algebra in his freshman year and biology in his sophomore year, suggested to the Kaczynskis that he might skip two full grades. They resisted. Whatever his intellectual gifts, Ted had a lot of growing up to do. Already one year ahead of his peers, a two-year leap would land him among classmates who were three years older, physically and emotionally. But holding him back risked deepening his alienation. There was also the satisfaction that came from having a son who could race ahead of others in that way. They agreed to let him skip just his junior year.

That put Ted in the graduating class of 1958. Years earlier, while their high school was under construction, members of that class had begun their freshmen year in a church basement, where the end of classroom periods was marked by the ringing of a cowbell. “That experience made us very closeknit by the time we were seniors,” recalls David Kaiser. Kay Jones Stritzel, a cheerleader who was one of Ted’s classmates, says he acted like “a frightened puppy dog” whenever she approached him. Even she, at 5 ft. 7 in., towered over Ted, who “looked like a baby.” If you talked to him, Kaiser says, Ted would just “turn away and mumble.”

So in his senior year, like all the others, Ted didn’t fit anywhere. The girls in gingham and headbands wouldn’t date him, even if he could have worked up the nerve to ask them. The athletes who roared around in their tail-fin cars were more apt to ignore him than torment him. Even among the other brains, who were mostly two years older, he was the runt of the litter.

But in everything that bore upon the life of the mind he was king. By the time he graduated, he had been accepted to Harvard, a place the more ordinary students of Evergreen High could scarcely aim for, much less get to. But no one was really surprised when Ted was accepted there, anymore than they had been surprised that he was a National Merit finalist, one of five in the graduating class of 183.

It wasn’t just that he was brilliant. He was brilliant in the world of numbers, which the cold war had suddenly given a whole new importance. At the start of senior year, in October 1957, the Soviet Union launched Sputnik, the first artificial earth satellite. Suddenly frightened by the prospect of falling behind in the space race—a contest that most people did not even know they were in a few months before—Americans were about to put their children through a crash course in the sciences. For the best and the brightest among them, there would be every opportunity, and not a little pressure, to concentrate on fields that would close the presumed science gap between the U.S. and the U.S.S.R. Teddy was already well along in his training. In one respect at least, he was the perfect specimen of what America needed.

If Teddy was ready. He was just 16, lacking even a driver’s license, and he seemed in some ways much younger. There was no doubt that he was ready for the intellectual rigors of college. And the emotional ones? Maybe a life on his own would help to bring him out of his shell. His parents could only hope.

The Untenured Mathematician

The system needs scientists, mathematicians and engineers. It can’t function without them. So heavy pressure is put on children to excel in these fields. —Manifesto, paragraph 115

When he arrived at Harvard, Ted Kaczynski did what he had done all his life at home: he ran to his room and shut the door. He was “the ultimate loner,” remembered Keith Martin, who lived in the same freshman dorm. Decades later, after Kaczynski was arrested, Andrew Sihler, now a linguistics professor at the University of Wisconsin at Madison, tried to recall who this supposed classmate could be. “I took out my yearbook and said to myself, ‘Oh, him.’ ”

Kaczynski had been accepted at Harvard when the school was in the midst of a long process of change and selfexamination. The elite university was opening up to the new winners in the emerging American meritocracy. If his test scores were high enough, a boy from a Polish-American family of modest means could find himself crossing the same quadrangles where Cabots and Lowells used to walk. And where a few Kennedys still did.

But if Harvard was changing, Ted was not. As a freshman, he holed up in a first-floor room at 8 Prescott Street, a light-colored, framed, university residence that housed 15 undergraduates considered poor prospects for group living (most freshman lived two to four in a suite). The three years that followed he spent in the famous and formidable Eliot House, along the Charles River. The preppiest place on campus, Eliot to a large extent was a spill tank for the gene pool of the old Wasp ascendancy. Its legendary house master and philosopher king was professor John Finley, a classicist and the last word in gentlemen. For Kaczynski, a maladroit boy from nowhere in particular, Eliot House might as well have been Buckingham Palace.

It so happens he was assigned to a suite with five other underclassmen who also were outsiders of a kind. “We didn’t choose to room together,” said Michael D. Rohr, now a philosophy professor at Rutgers University. “I was assigned to a suite of people without roommates. They were mostly loners. One of them seemed more interested in insects than people.” The rooms they occupied, the ones approached through the ’N’ entry, were “the low-rent wing of Eliot House,” said Patrick McIntosh, one of Kaczynski’s suitemates. While the classic Harvard suite featured a living room with a fireplace, this “suite” was just a corridor lined by six bedrooms, a bathroom and a walk-in cedar closet that housed a telephone. As everybody knew, the rooms had once been the servant’s quarters for the house master’s quarters just below. “We felt like we were second class,” said McIntosh. “Some of the preppies certainly made us feel that way whenever possible.”

Martin, who shared the suite with Kaczynski, remembered him as a blur. “He would walk down the corridor in a , forced-march pace and open his door and slam it. And that I would basically be it. His goal was not to get stopped by anybody to talk.” At a time when Harvard men were required to wear a coat and tie to meals, rumpled Kaczynski complied. But he almost always ate alone, usually at one of the comer tables. “I’d go to his table, and he would not say much,” said McIntosh. “He’d smile furtively and leave before he was really finished.”

Though he didn’t talk much, a lot of people say, like the Cheshire Cat, he left behind his smile. That “great, shy smile” said Gerald Bums, another fellow student. “You should have seen his smile back then.” But the other memory he left was a faint bad odor, like the stockyard smell that hung over his old neighborhood in Chicago. His room was filthy. “I swear it was 1 ft. or 2 ft. deep in trash,” said McIntosh. “Underneath it all were what smelled like unused cartons of milk. We finally called the house master, who was aghast.”

During senior year, McIntosh decided to bunk with Martin. That freed one bedroom, which the group used to create the common room their suite otherwise lacked. The boys moved in a TV, a stereo, a sofa and a few chairs. But Kaczynski never joined them for bull sessions or trips to the movies. While they gathered there, he locked himself away in his room. Sometimes they would ask him to play his trombone more quietly. Said McIntosh: “Why we didn’t put two and two together and say this guy needs help, I don’t know.”

Kaczynski did well at Harvard, but not well enough to make the top of his class. He graduated in 1962, but not cum laude. He didn’t write, a senior thesis. After leaving, he maintained the same low profile. Since 1982, his mailing address in the Harvard alumni records has been 788 Banchat Pesh, Khadar Khef, Afghanistan. If he was ever there, that part of his life is still to be unearthed.

From Harvard he went on to graduate work in mathematics at the University of Michigan at Ann Arbor. There he made much the same impression as he had at Harvard. “I don’t remember anything about him. I don’t think I ever even saw him,” said Alan Heezen, who spent most of the 1960s studying math at Michigan. “The math department was not very big in those days. I thought I knew everybody in the class, but I guess that I didn’t.”

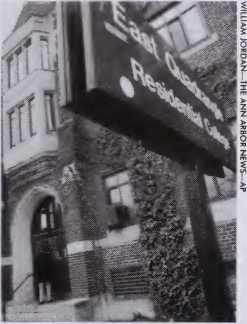

Altogether the university had 25,000 students, a crowd where it was easy to get lost. Judging by the university archives, Kaczynski is someone who hardly existed. His name cannot be found in the Michigan yearbook for 1964, when he received his master’s degree, nor 1967, when he was awarded his doctorate. He left behind an 80-page doctoral dissertation and some faculty records attesting to the fact that for three years, he served as a part-time teaching assistant. That paid him $2,350 annually.

During his first two years in Arm Arbor, he lived at the East Quadrangle Residence Hall, a vast, brick box that housed 1,100 men. For the next three, he moved to off-campus apartments within walking distance of his classes. Professor Peter Duren remembers Kaczynski as the student who used to show up at his real analysis course wearing a jacket and necktie. “It was unusual in those days,” Duren said. The Kaczynski he knew had a passion for math. During lectures he often sat at a front desk, asking one question after another. But outside class the inquisitive student disappeared into himself. “If the topic was math, he was ready and willing to talk about it,” said Duren. “He did not go out of his way to make social contact. But he didn’t strike me as being pathological. People in math are sometimes a bit strange. It goes with creativity.”

One other thing Duren remembered is that when solving problems in math, Kaczynski always offered “much more proof than was really needed.” Years later, fbi investigators would note that the Unabomber on occasion built redunan- cies into his bombs, providing more initiators, for example, than the devices required.

Just as Harvard was changing when Kaczynski arrived there, so was Michigan. The student movement of the 1960s was gaining momentum; civil rights and antiwar activism were becoming as common on campus as fraternity parties. In 1962, Students for a Democratic Society, which would become the most prominent campus radical group of the era, was founded 98 miles away in Port Huron, Michigan. Men and women studying math or science, like Kaczynski, found themselves under increasing pressure not to undertake work or research that might contribute to the Vietnam War effort.

In 1967, Allen Shields, Kaczynski’s doctoral thesis adviser, was one of 60 math professors from around the country who signed an open letter to his colleagues calling on them to refuse involvement in Pentagon research. Published in the Michigan Daily, the campus student newspaper, it read in part: “We urge you to regard yourselves as responsible for the uses to which your talents are put. We believe this responsibility forbids putting mathematics in the service of this cruel war.”

“There was a gradual loss of faith in institutions,” said Michigan State University mathematics professor Joel Shapiro, who studied in the math department with Kaczynski. “And there was a lot of anger on the University of Michigan campus. The whole society was just polarized. Everyone was touched in one way or another by what was going on.” Kaczynski, however, remained aloof. Unlike other students, who typically sought weekly sessions with their advisers, he did not meet regularly with his, preferring simply to turn in piles of neatly organized equations. “His strength was his independence,” said Duren.

Kaczynski’s specialty, “boundary functions,” is an area that is familiar to mathematicians and arcane to everyone else. By graduate school, he had moved into a mathematical realm that was utterly removed from human concerns.

Elegant, if you have a taste for abstraction and know the language, but very detached. His doctoral dissertation was closely crafted and presented with carefully argued proof. One typical sentence reads this way: “If f is defined in H, then the set of curvilinear convergence of f is the set of all points x E X such that there exists some arc at x along which /approaches a limit.” And so on.

“There is no point in going into his dissertation,” said Chia-Shun Yih, one of Kaczynski’s thesis advisers, who barely remembers him. “It is advanced and abstract. There is no connection between the violence, the bombs and the work he did on his dissertation. None at all.”

If the University of Michigan largely forgot Kaczynski, perhaps Kaczynski did not forget his alma mater. In the fall of 1985, one of the Unabomber’s mail bombs went off there, at the home of James McConnell, a well-known professor of psychology and the author of a widely used textbook. The book-size package bomb was opened instead by his assistant, Nicklaus Suino, who sustained flesh wounds to his arms and upper body.

McConnell came to believe he had been targeted because the Unabomber hated one of his fields of research, behavior modification. Years after McConnell’s death from a heart attack in 1990, the Unabomber’s manifesto appeared to bear out those suspicions. Part of it was devoted to an attack on that same area of study. “The system will therefore be FORCED to use every practical means of controlling human behavior.” But when Kaczynski became the chief Unabomber suspect, fbi investigators also began to wonder whether he had zeroed in on McConnell because he knew him, or at least knew of him, from the years when they were both at Michigan.

Toward the end of Kaczynski’s years at Michigan, the world of his youth was disintegrating. In 1966, while Ted was finishing up his Ph.D., his brother David moved to New York City to start his freshman year at Columbia University, where he would eventually get a degree in English. His parents moved also, to the small town of Lisbon, Iowa. His father had taken a job there as a supervisor of the newly opened factory of a foam-cutting company, Cushion Pak Inc.

There the Kaczynskis became friends with a crowd of politically active lowans and got involved in a local controversy over whether children from a nearby Amish community would be required to attend public school. The Kaczynskis became enamored of the Amish and their peaceable ways. Ted Sr. was especially intrigued by their rejection of modem technologies, a position he respected, even if he was not prepared to imitate it himself. “Kaczynski really admired the Amish, the way they lived,” said Paul Carlsten,. who was then a political-science professor at Iowa’s Cornell College. “He saw how technology could subvert the world— just as the Amish did.”

In 1968 the elder Kaczynskis moved again, this time to Lombard, Illinois, another suburb of Chicago, and Ted Sr. had a job nearby with another factory. In that year, the compressed forces of the decade suddenly detonated. At Columbia University, where David Kaczynski was a sophomore, the students took over the campus for a week in April. Martin Luther King and Robert Kennedy were assassinated. In France, students and workers nearly toppled the government. In Vietnam, the Viet Cong’s Tet offensive made it plain to Americans that victory, if such a thing were possible at all, would be a long and bloody affair.

The elder Kaczynskis, active as they were in liberal causes, found themselves swept into the antiwar presidential candidacy of Senator Eugene McCarthy first in Iowa and then in Illinois, where they both joined the Lombard Democratic

Club (Wanda attended meetings until January 1996). It was a time when all the predicaments of the West boiled down to the word Vietnam, and “the war machine” was a metaphor for the perverse means by which America’s industrial and scientific power might subvert democracy and subdue a small nation. When McCarthy spoke of how the best scientific minds were being applied to the service of illegitimate aims, Ted Sr. could only nod in agreement. That summer, at the Democratic Convention in Chicago, the system would appear to melt down before their eyes.

By that time, their eldest son had relocated to Berkeley, another center of the student revolt, but he had not signed up as a soldier in the revolution. He was on his way to a tenured post in the math department, considered by many to be one of the most prestigious in the world. If Ted Kaczynski had wanted it, his skills could have put him in line for a number of private-sector careers that relied upon numbers: aircraft, computers, financial markets. Instead he was pursuing an academic career. After getting his doctorate, he had been hired as an assistant professor of mathematics on a two-year contract that had commenced in the fall of 1967.

The offer required that he teach two undergraduate courses, number systems and introduction to the theory of sets, and two for grad students, general topology and function spaces. “We hired about 10 [assistant professors] a year then,” recalled professor emeritus John Wz. Addison Jr., who was department chairman during Kaczynski’s years there. “On average, about one out of three would have got tenure.”

Kaczynski stood a good chance of being one of them. Since 1964, he had published three mathematical papers with typically abstruse names: “Another Proof of Wedderburn’s Theorem,” “Boundary Functions for Functions Defined in a Disk,” “On a Boundary Property of

Continuous Functions.” While he was at Berkeley, he would publish three more papers. Whatever they were called, it was an accomplishment that would place him well along on the tenure track. An offer could be expected within four to six years of the time he started work.

After he was arrested, everyone would describe Kaczynski’s handwriting as meticulous. Childlike would be a better word for the lettering of his faculty biography, the data sheet he provided to Berkeley three days before Christmas 1966. The letters are widely spaced and so painstakingly drawn they look like penmanship samples in a grade-school writing pad. As for information, Kaczynski didn’t offer much. One line of the form requested: “Use the following space for biographical data that you desire to have become a part of your official University of California records.” He left it blank.

Kaczynski lived in a small apartment at 2628A Regent Street. In a community offering everything from gingerbread Victorians to Arts and Crafts bungalows, his homely stucco residence was the kind of place in which you might expect to find a penniless student, not an assistant professor on his way up in the world. Faculty, even the newer ones, favored the hilly north side Qf the campus, with its views of the campus clock tower and, further in the distance, the skyline of downtown San Francisco and the Golden Gate Bridge.

The area where Kaczynski settled was flat, viewless and crowded with students. Many people preferred it, however, because Telegraph Avenue ran through the neighborhood like a bolt of lighting. His 15-minute walk to campus took him along all its jagged edges, offering a full dose of the Berkeley carnival. In those days, Telegraph was thronged with long-haired students and street people, dressed in dashikis and ponchos, army surplus and tie-dyes. Life was a costume party, and everybody was invited. It was here you found the shops, cafes and three locally famous bookstores, Moe’s, Cody’s and Shakespeare & Company. Sidewalk vendors peddled hash pipes and handmade jewelry. In the air, there was incense and marijuana smoke. And music: maybe After Bathing at Baxter’s, a trippy album by the Jefferson Airplane, maybe Anthem of the Sun by the Grateful Dead, who were then still a dustball menagerie and not the institution they would become, or maybe the leftist anthems of Phil Ochs, such as I Ain’t Marchin’ Anymore.

That title was a double-edged joke at the time. Everybody was marchin’. And all roads led to Sproul Plaza. The university’s sunlit public forum was the white-hot center of the Big Bang. In 1964 it had seen the birth of the Free Speech Movement, a primal episode of what would be the worldwide student upheaval. By the time Kaczynski arrived at Berkeley, hardly a day went by without a campus demonstration. Most of them started on the steps of Sproul Hall, the main administration building. Classes were routinely canceled because students, too busy protesting, failed to show up. Kaczynski would always show up.

In fact, there is no evidence that Kaczynski was ever involved in any political activity. Still, he would have had to be deaf, dumb and blind not to absorb the message of the student protesters. Certainly the Unabomber did: the manifesto both parrots and pillories much of the leftist rhetoric from this period about freedom, repression, social control and high technology. It also notes that “in any event no one denies that children tend, on average, to hold social attitudes similar to those of their parents.” The raucous showdowns in Berkeley had their genteel counterpart in Lisbon, where Ted’s mother sewed headbands for the peace candidate’s I youthful supporters.

Heading for one of his classes in Campbell Hall, where the math department was based at the time, Kaczynski would run a gauntlet of recruitment tables and leafleteers, pacifists, Trotskyists, Hare Krishnas, Black Panthers. The world itself was up for grabs. It could seem sometimes that all of the pieces were being thrown into the air. It only remained to see how they might be reassembled.

Or how the fallout could be avoided altogether. If Kaczynski wanted peace and quiet, there was a bit of that too. Scattered around the surprisingly pastoral Berkeley campus were unexpected pockets of tranquillity. Just outside the back door of Campbell Hall he could walk down 26 steps, pass under an old arch inscribed in Latin and find himself in Faculty Glade, a grove of redwoods. Even now, it remains a place where you can almost imagine shutting out the clatter of history. But not quite. The streets of Berkeley are not all that far away. From there he would have to dip back eventually into the crowd heading for Telegraph.

And back to the classes he hated to face. The boy who could never talk to anyone had no gifts as a teacher. Every year Berkeley students evaluated their instructors in ratings that were printed in a supplement to the college catalog. If Kaczynski were a Broadway show, he would have closed on opening night: “Kaczynski’s lectures were useless and right from the book ... He showed no concern for the students ... He absolutely refuses to answer questions by completely ignoring the students.” Undergrads are a tough jury. A lot of faculty fared just as badly. But by now, this notice sounds like the Kaczynski everybody knew. Or didn’t know.

His last act was on Jan. 20, 1969. The attention of most people that day was focused on Washington, and the inauguration of a new President, Richard Nixon, the man Kaczynski’s father could not abide, the man about whom thousands of passionate young people had said, “If he’s elected, I’m leaving the country.” On that day, Ted abruptly tendered his resignation. In the two-line note in which he gave the news to math department chairman John Addison, he didn’t offer any explanation. Later he told people that he was leaving the field of mathematics altogether. For what? He didn’t know.

While some academics leave their posts because they decide they are not going to get tenure, that was not the case for Kaczynski. Addison and Calvin Moore, the department vice chairman, tried to talk him into staying. “Dr Kaczynski has decided to leave the field of mathematics,” Addison said in a March 2, 1969, letter to Walter D. Knight, dean of the College of Letters and Sciences, in which he informed him of Kaczynski’s “sudden and unexpected resignation.” He further told Knight that he and Moore had “tried to persuade him to reconsider his decision but [had] not been successful.” Certainly Kaczynski was not the only defector from academics and the sciences in this era. “It was not uncommon,” recalled Addison. “One of my advisees went and lived on a farm and did carpentry.”

Later Kaczynski’s old thesis adviser, Allen Shields, heard that his well-regarded former student had bolted from a job that promised a great deal. Puzzled and concerned, he wrote to Addison, who replied that Kaczynski had told him he was not sure what he was going to do. “He was very calm and relaxed about it on the outside.”

Addison added, “Kaczynski seemed almost pathologically shy, and, as far as I know, he made no close friends in the department. Efforts to bring him more into the swing of things had failed.”

Montani Semper Liberi

Freedom means having power; not the power to control other people but the power to control the circumstances of one’s own life. —Manifesto, paragraph 94