Nine Heroes

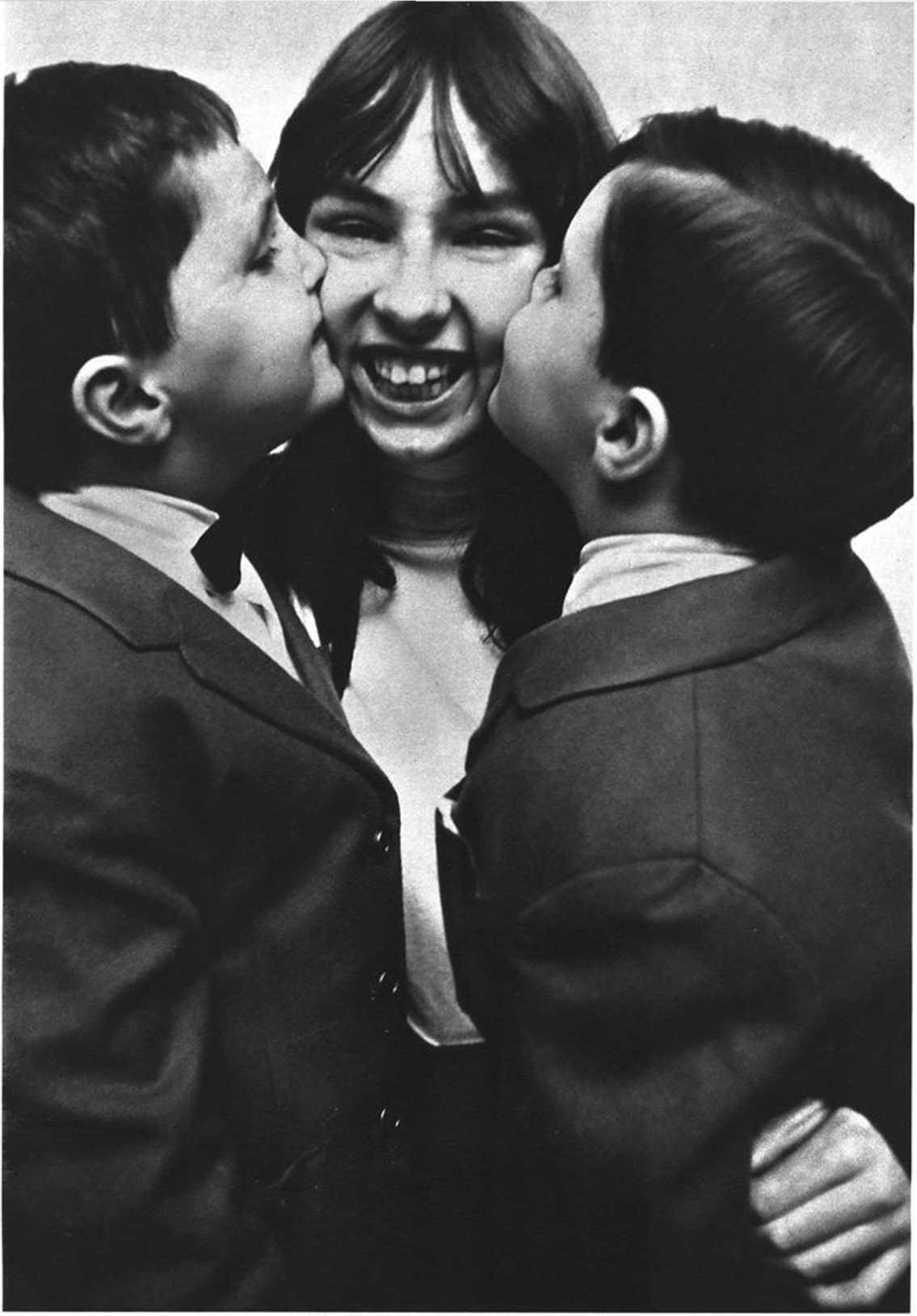

Thirty-eiglit people heard Kitty Genovese cry out for help and did nothing: a circumstance that was immediately seized upon as a paradigm for our times. Perhaps it is. But let the historians of the future take note that in a grubbily selfish decade there were a few Xmericans. at least, capable of selflessness. To set the record straight we present nine of them here, and we begin with Gloria Cassidy, shown above with her brothers. Gregory and Sean. Gloria hail no need to ask whether or not she was her brothers' ker|>er; she assumed she was, and kept them. On October 27. 1965. a fire broke out in the twins' bedroom in their New York City apartment. Mrs. Cassidy roused her six children and got them outside, but in the confusion Sean and Gregory, then three years old, ran back into their room and hid in a closet. Gloria heard their screams and ran back to find them. She brought them out one at a time— first Sean, then Gregory. “The pain from the Hames was so bad I thought I d go out of my mind, she said. Gloria suffered third degree burns over most of her body and was hospitalized for three months. She was then thirteen years old. She was presented with the Young American Medal for Bravery by the President of the United States.

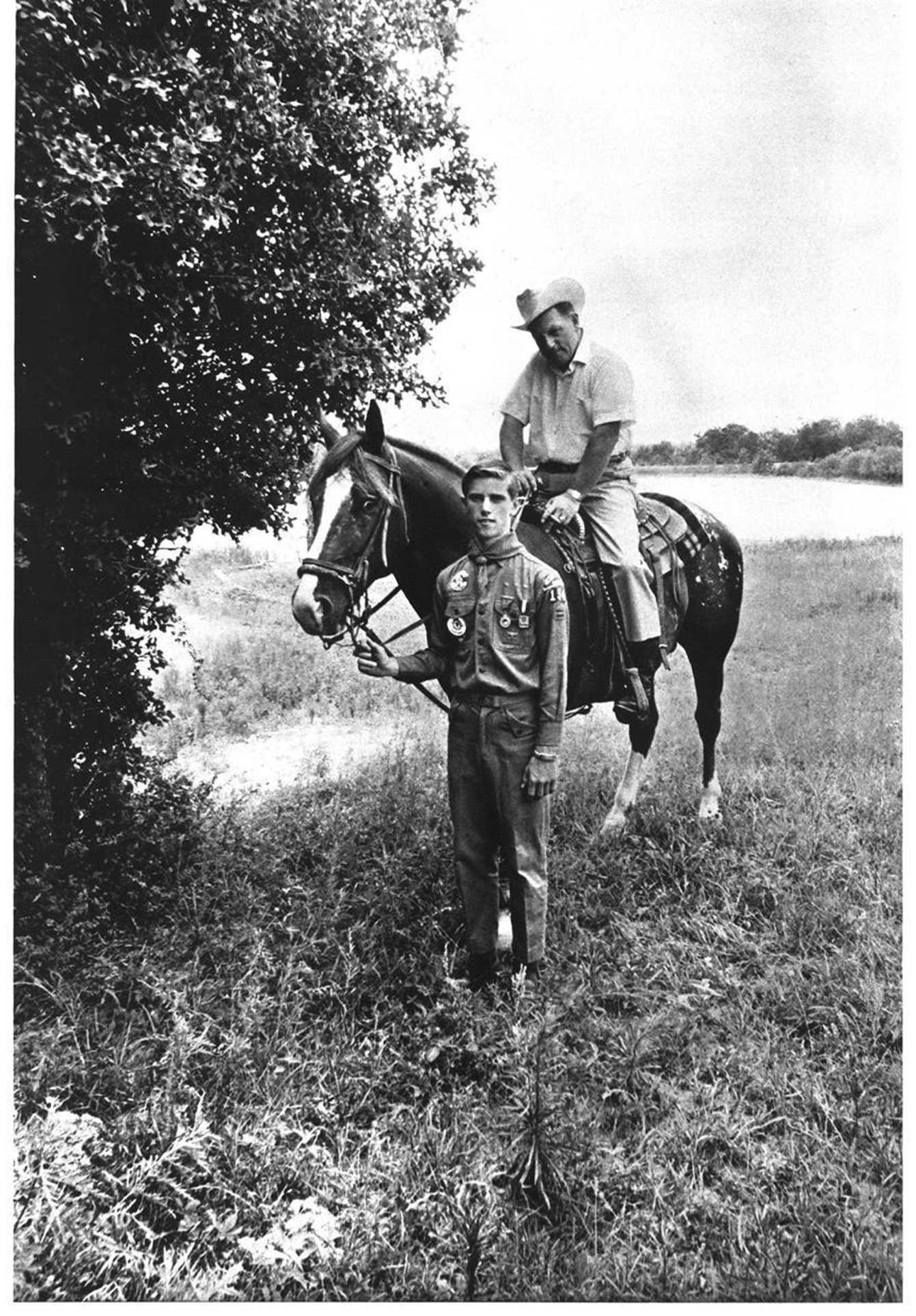

It’s by the grace of God and David Goolsby that I'm alive today.” So says II. C. Schulte whose life David saved on his Texas ranch on July 30. 1966. David was swimming with his younger brother and a friend. Schulte was crossing the lake on the back of a stallion some four hundred yards away when David saw the horse rear up and fall backward on the rancher. Knowing that Schulte could swim, David's first thought was getting the stallion safely to shore as he began swimming toward the accident. As he approached he heard Schulte cry out for help: “I swam faster than I thought possible ami went down as deep as I could." Schulte had become entangled with a submerged branch which David broke. He grabbed his friend by the collar and got him to the shore, one hundred and thirty yards away. Schulte weighed one hundred seventy |»oiinds. David one hundred ami eight. On shore David applied mouth-to-mouth resuscitation, then placed Schulte, face down, across his horsr and took him to the ranch house two miles away where a doctor was summoned. In the interim David, remembering that Schulte had a heart condition, placed two nitroglycerin tablets under the rancher's tongue. David was awarded the Honor Medal, the highest Boy Scout award, and the Carnegie Hero Medal, bronze. "David is truly an unusual young man." said Schulte.

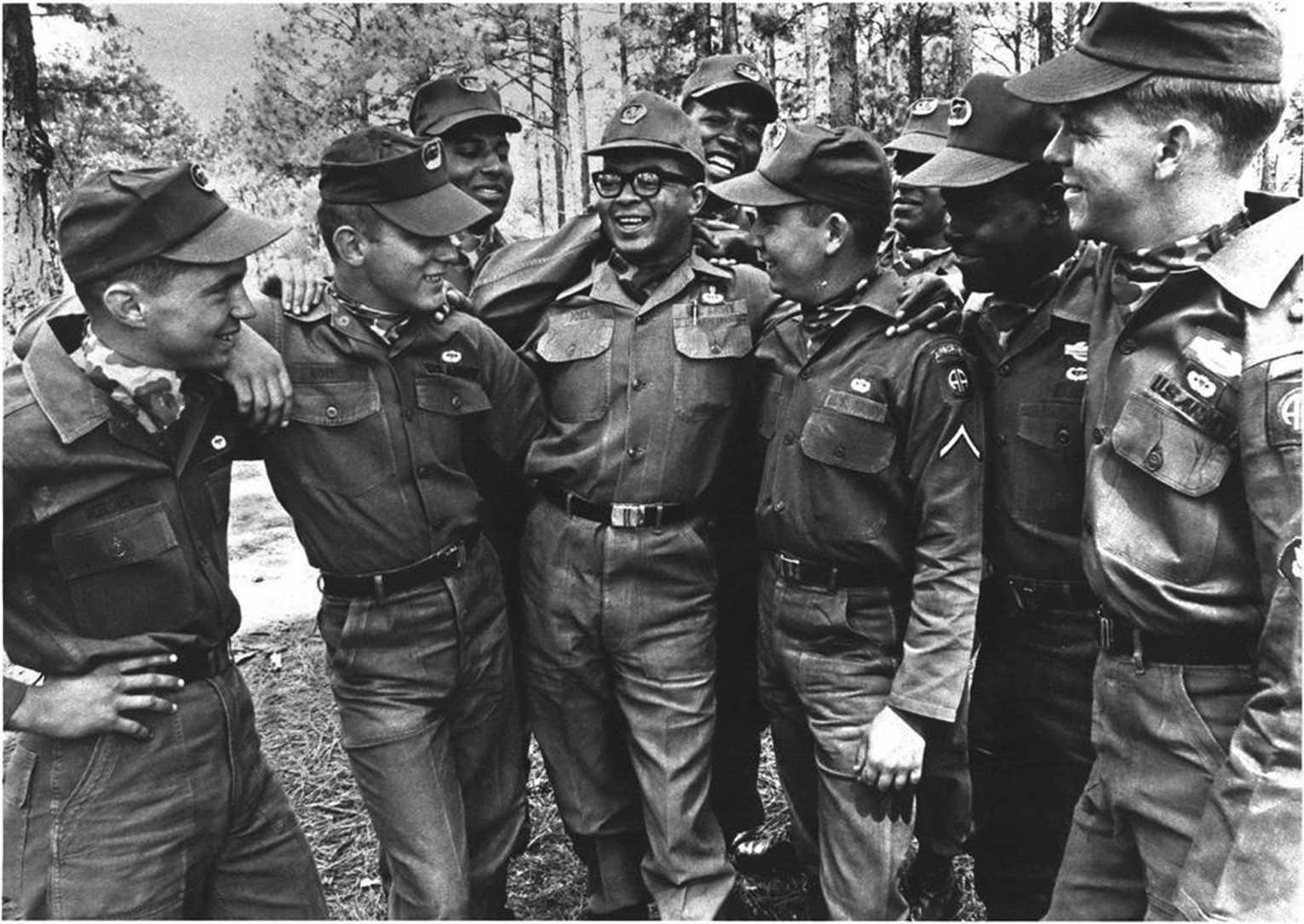

Lawrence Joel joined the Army because he was convinced "you couldn't make it really big" as a Negro in the civilian world. As a medical aidman with the rank of Specialist Five, he made it really big in Vietnam: he won the Congressional Medal of Honor, "for conspicuous gallantry and intrepidity in action at the risk of his life above and beyond the call of duty." On November 8. 1965, a \ ietcong ambush killed or wounded nearly every man in the lead squad of his company. Joel, heedless of enemy fire, went from man to wounded man administering aid. A machine gun tore into his right leg. Bandaging his wound, and allowing himself one Syrette of morphine for his pain (afraid that more would interfere with his performance). Joel continued to search for the wounded. He had just finished giving plasma to one man when he was hit again. With the bullet lodged in his thigh he dragged himself around the field and treated thirteen more men until his medical supplies ran out. He saved the life of one by placing a plastic bag over a chest wound to congeal the blrntd. Having replenished his stock. Joel crawled through continuous enemy fire to get back to the field. The citation reads, in part. "His meticulous attention to duty .. .and his unselfish, daring example under most adverse conditions was an inspiration to all." Photographed at Fort Bragg with members of his outfit.

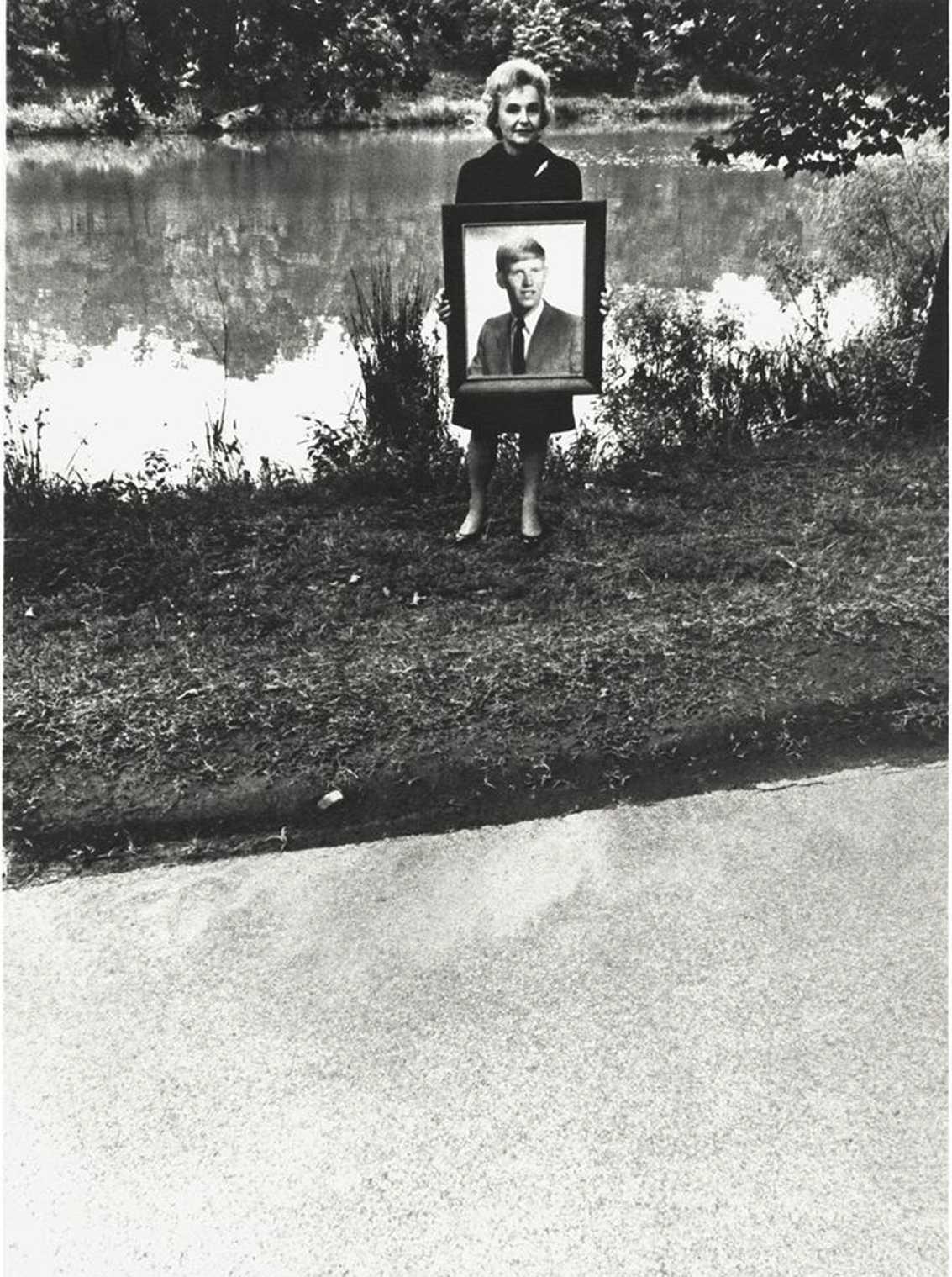

Holding a picture of her rescuei. Don Trickey, and standing at the very spot where her car splashed into the water, is Mrs. Inez McSwain. Trickey is now in the Navy and in Japan, hut on January 22, 1966, he was driving home from a dale along Lakeshore Drive in North Little Bock. Arkansas. As he glanced in his rearview mirror he saw Mrs. McSwain's car go out of control, plunge over an embankment into Lakewood Lake No. 2. Trickey stopped and ran to the water's edge where he saw the car was sinking rapidly. He called to Mrs. McSwain to gel out but she, growing panicky, shouted back that she couldn’t swim. Trickey took off his shirt and shoes and swam to the car. “When I got to it the car wasn't completely under water. The top was still sticking up. The front end was down, the trunk up. Mrs. McSwain had the window about halfway down, with her head out." Trickey reached in, rolled the window all the way down and brought her out. He held her around the neck and shoulder ami swam some fifty yards to the shore. He rang the doorbell of a house across the street and a lady let them in. The lady phoned Mrs. McSwain's husband and Trickey told him about the accident. “Then we called the wrecker and got it out there." The police refused to let Trickey go back into the water to help with salvage operations, so he went home. He didn't even catch a cold.

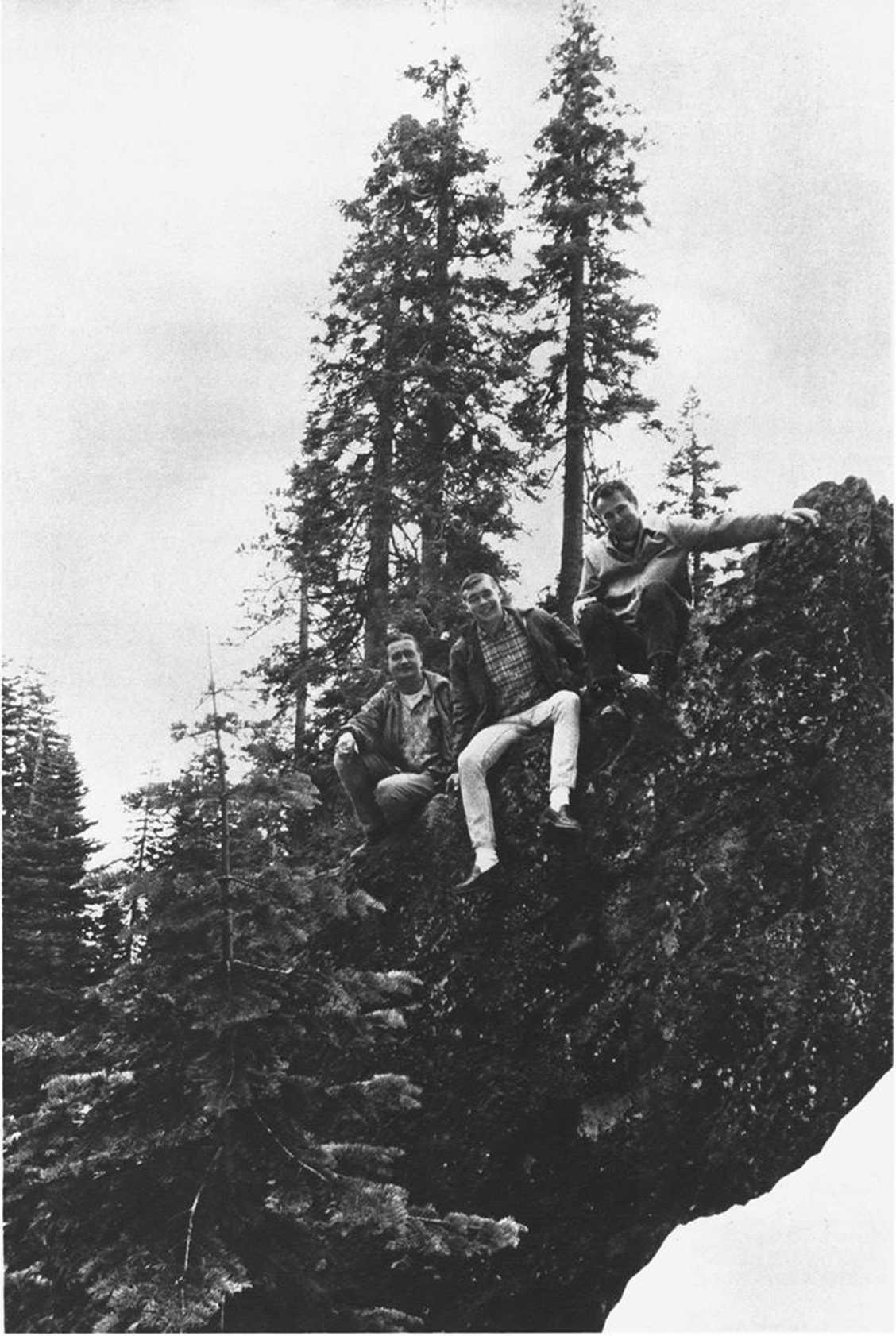

Laughing about it now that it’s over arc. left to right. Kenneth W. Terry, Clayton E. Toensing and Howard I). Hill. On July 7, 1965, Toenning. a girl, and another boy began the descent from the top of Granite Chief Peak in Squaw Valley, California. The boy lost his footing and fell Iwo hundred sixty feet to the bottom, and wa* badly injured. Hurrying down, Tocnsing also slipped, but landed on a .small ledge two hundred feet from the base without damage. The girl made it down and summoned help. Hill and Terry, repairmen for a telephone company, took with them a two hundred fifty foot rope and went to the top of the cliff. There they found two other men who had tied a two hundred foot rope to a tree. They joined the ropes and Hill climbed down it to a narrow ledge vertically above the one on which Toensing stood. Terry came down next and held Hill's legs while Hill looked over. He saw Toensing but couldn't reach him. They formed a loop with a slipknot on the rope’s end. and, while Terry again held his legs. Hill went over and managed to get the rope around Tocnsing's chest. Holding onto the rope with one hand and Toensing with the other. Hill inched his way back over the edge as Terry pulled first on Hill and then on the rope. They made it. and. after a brief rest, fashioned a sling and lowered Toensing to the bottom of the cliff.

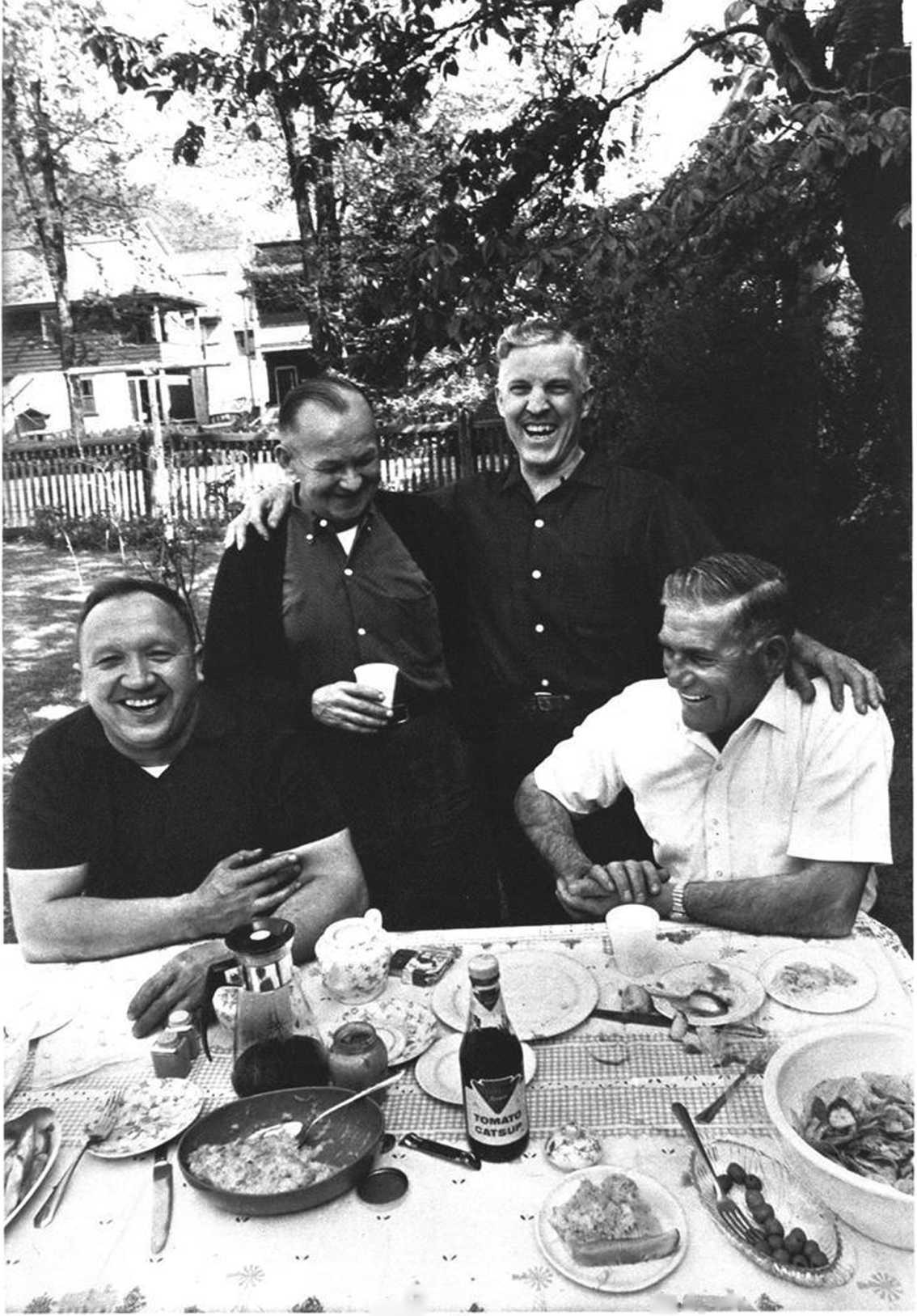

The heroes are laughing: the rescued man. Peter Byczkowski, is looking pleased and holding a cup. Eroin left to right: William Paul Holena. Byczkowski, Clair S. Sigworth, and Prank Di Andriole. A coal mine caved in at the Franklin Colliery, Wilkes-Barre. Pennsylvania on December 21. 1964, trapping Byczkowski and his brother-in-law under coal and debris eight feet deep. Everyone else got out. After a second collapse, the mine was ordered clear of all rescue workers: the risk was too great. By this time, however, the rescuers had learned that Byczkowski was still alive, his brother-in-law dead. In spite of the warnings and the virtual certainty of further cave-ins. Sigworth, a mine inspector, and Holena, a miner, decided to get Byczkowski out if they could. To reach him they made their way among the temporary supports to a ten foot area between the end of the passage and the pile of debris under which Byczkowski was pinned, face down. His legs were caught under heavy timbers, his upper body free. There was just enough room for Sigworth to lie on top of him and remove the coal covering his legs, passing it back to Holena. Although they did manage to uncover his legs, Byczkowski's feet remained caught and it was not until the two men, joined by Frank Di Andriole, had made repeated trips through the* trembling mine with hydraulic jacks and other tools that they got the man free. Two hours later the gangway of the* mine collapsed and it took six days to find the body of Byczkowski's brother-in-law. The* reunion is photographed in Sigworth’s backyard, a rather ordinary looking group of American men—heroers. as all these* photos have shown, can look much like anybody else. And. like anybody else, the hero is concerned with himself: "I could never have* lived with myself if I hadn't tried to help that man." said Sigworth. You see? Just like* the rest of us.