Otto John Maenchen-Helfen

The World of the Huns

Studies in Their History and Culture

Fragments from the Author’s Preface

Author’s Acknowledgments (Fragments)

Hunnic Pressure on the Lower Danube

The Huns Help Aelius and Lose Pannonia

The Second Gotho-Hunnic War (463/4-466)

Speculations about the Language of the Huns

X. Early Huns in Eastern Europe

4. The Alleged Loss of Pannonia Prima in 395

5. Religious Motifs in Hunnic Art?

XII. Background: The Roman Empire at the Time of the Hunnic Invasions

II. Classical and Medieval Register of Cited Names and Titles

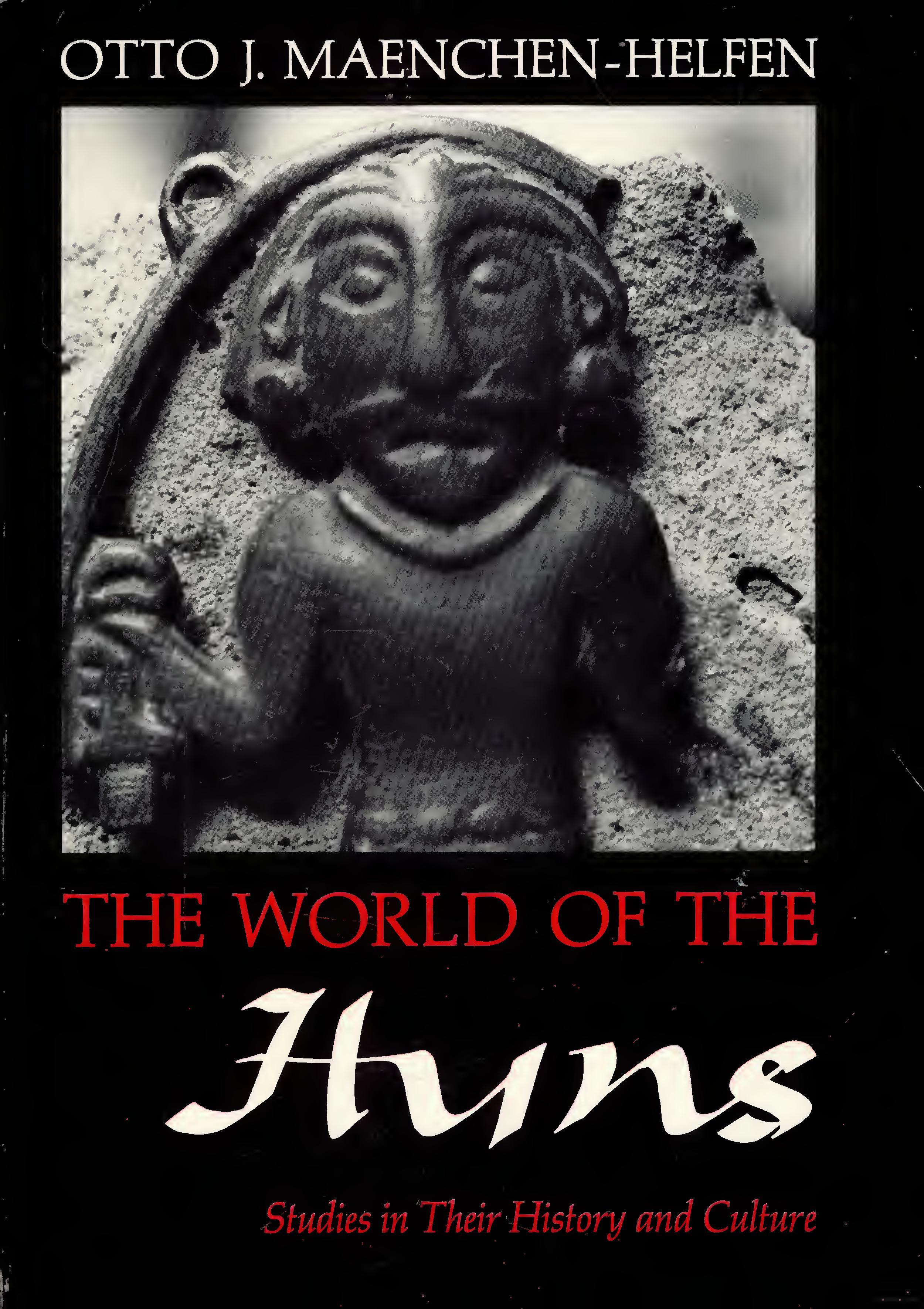

[Front Matter]

[Synopsis]

THE WORLD OF THE

Studies in Their History and Culture

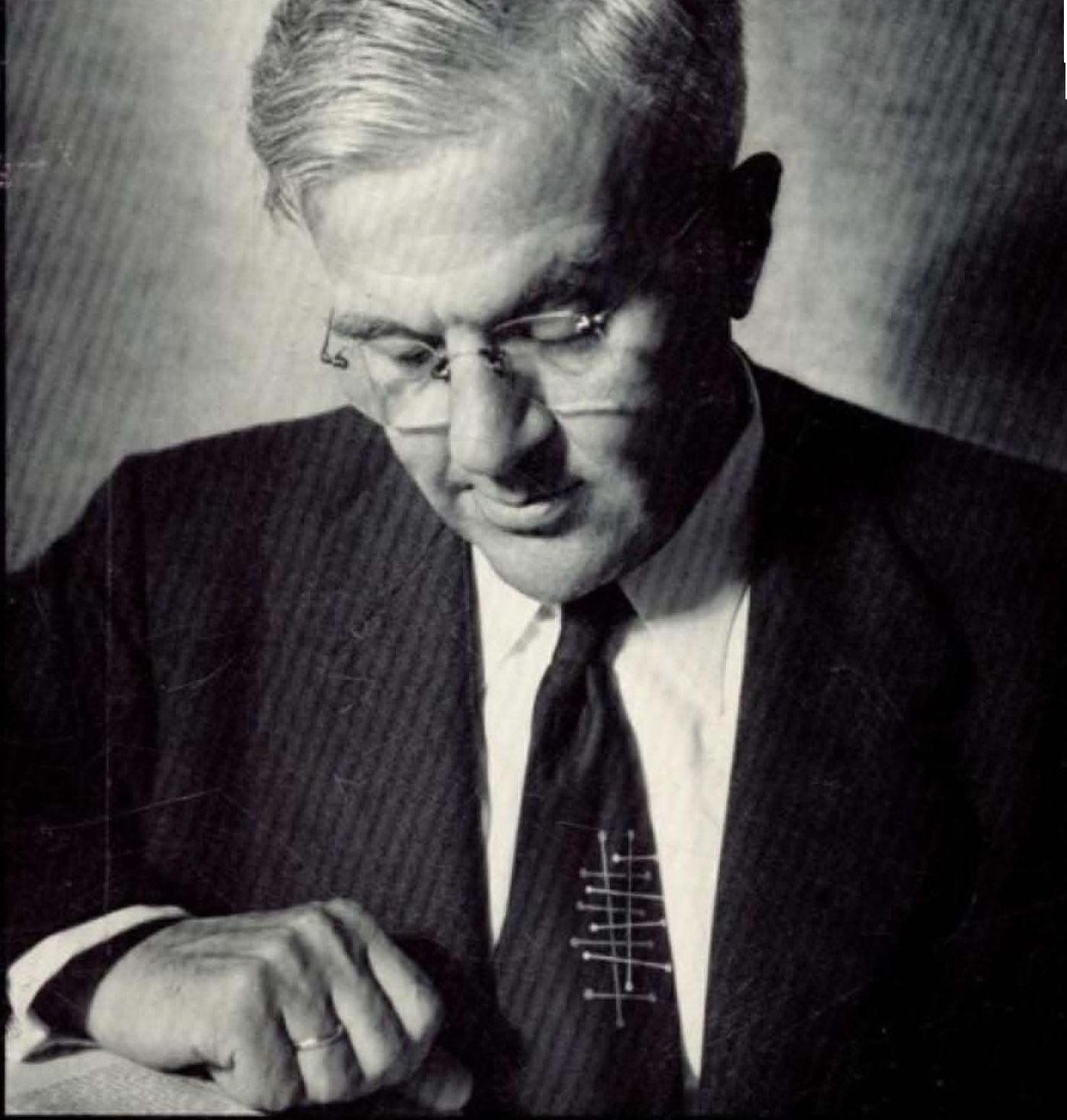

By OTTO J. MAENCHEN-HELFEN

Edited by Max Knight

Few persons know more about the Huns than their reputation as savage horsemen who flourished at the beginning of the Middle Ages and the name of one of their leaders, Attila. They appeared in Europe from “somewhere in the East,” terrorized the later Roman Empire and the Germanic tribes, caused the greatest upheaval that the Mediterranean world had ever seen—the Great Migrations — and vanished. Illiterate, they left no written records; such literary evidence of them as exists is secondary, scattered in the writings of contemporary and later reporters, fragmentary, biased, and unreliable. Their sole tangible relics are huge cauldrons and graves, some of which contain armor, equestrian gear, and ornaments.

Who were the Huns? How did they live? Professor Maenchen-Helfen dedicated much of his life to seeking answers to these questions. With pertinacity, passion, scepticism, and unsurpassed scholarship he pieced together evidence from remote sources in Asia, Russia, and Europe; categorized and interpreted it; and lived the absorbing detective story presented in this volume. He spent many years and extensive resources in exploring the mystery of the Huns and in exploding popular myths about them. He investigated the century-old hypothesis that the Huns originated in the obscure borderlands of China, whence in the course of several generations they migrated westward as far as Central Europe. In his quest for information about them. Professor Maenchen-Helfcn sifted written sources in the original classical, Slavic, and Asian languages. He also devoted years of travel to visiting archeological digs from Hungary to Afghanistan, from Nepal to Mongolia, and from the Caucasus to the Great Wall. His subject fascinated him, and this book conveys something of this fascination.

Intrigued by each report of the discovery of a new grave somewhere, the author could not bring himself to complete the work. At his death in 1969 his study was filled from floor to ceiling with binders, folders, and photographic negatives. Some chapters were in final form; many were not. The editor had to choose among various drafts, to decipher and organize, and to enlist the assistance of the author’s scholar-friends in filling gaps in the material.

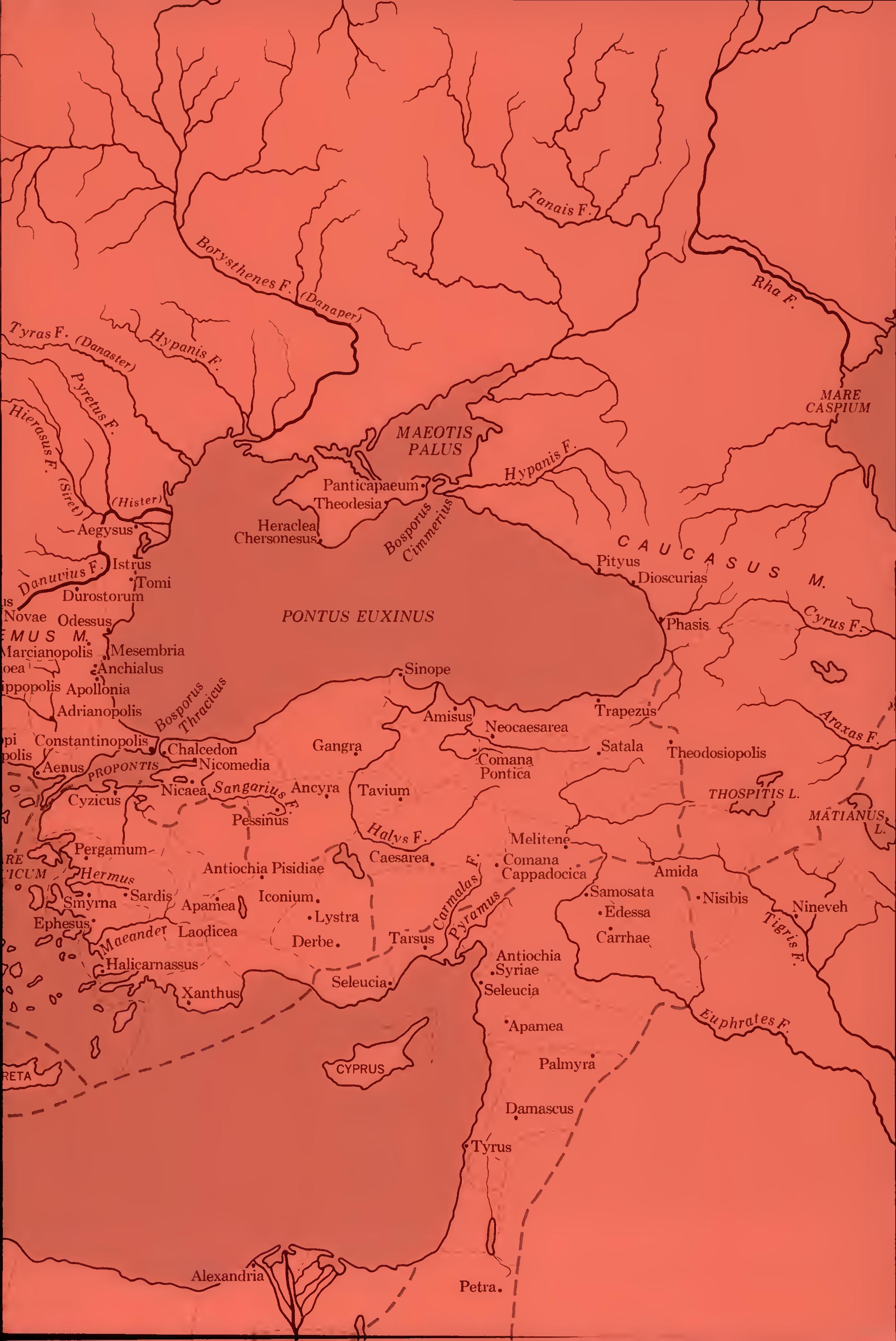

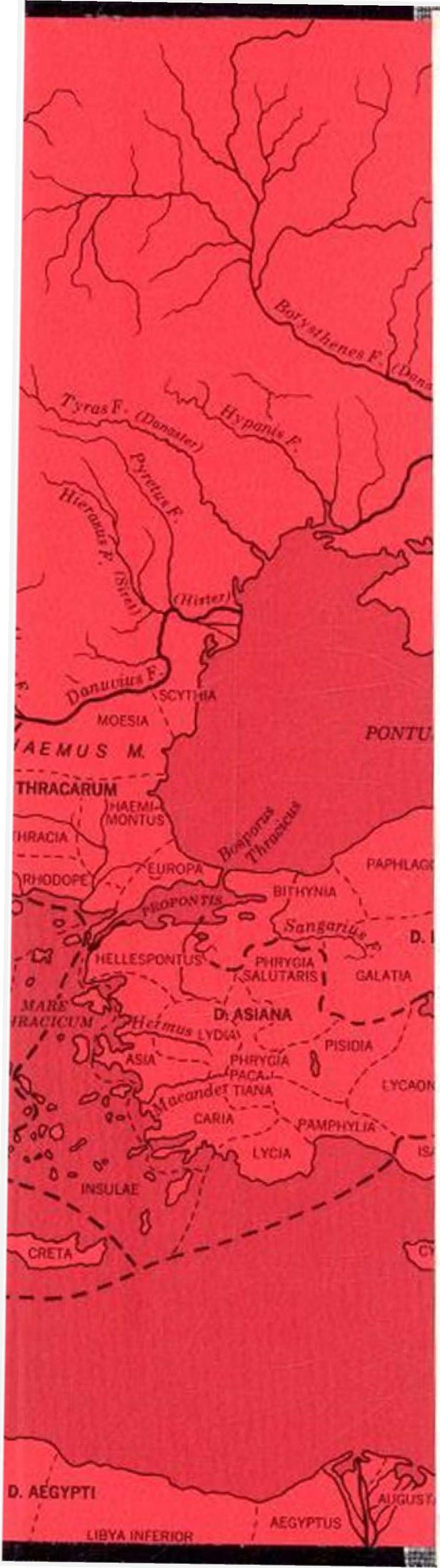

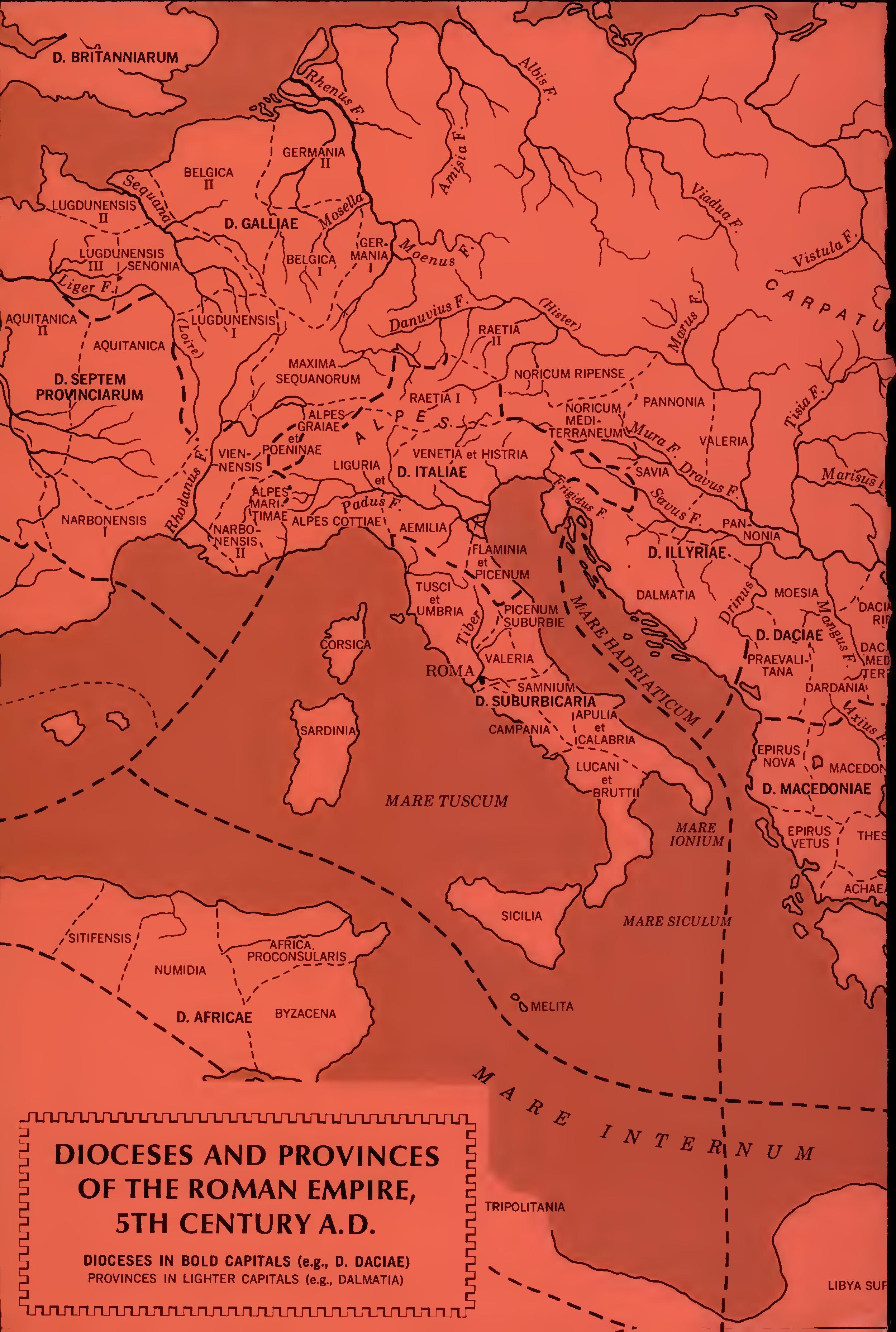

The work, intended primarily for scholars, lacks an introduction. However, Paul J. Alexander, Professor of History and Comparative Literature at the University of California, Berkeley, has provided a historical background designed for the general interested reader. The book is richly illustrated with rare photographs collected by the author, and includes a specially prepared map of the Roman Empire at the time of the Huns.

“Professor Maenchen’s knowledge of Central Asian peoples, including the Hsiung-nu and Huns, was absolutely unparalleled; his learning in several disciplines, including philology (with language knowledge ranging as widely as Greek and Chinese), was unique. His study includes the latest Soviet discoveries. Books of comparable scope have been attempted, but none of them has been buttressed by a comparable erudition; none has been infused with comparable understanding of the panorama of Eurasia; none has achieved in comparable degree the placing of the actors on this vast stage and their correct perspectivesand proportions.”

[Title Page]

THE WORLD OF THE

Hun

Studies in Their History and Culture

By J. OTTO MA EN CHEN-HELFEN

EDITED BY MAX KNIGHT

University of California Press / Berkeley / Los Angeles / London / 19 75

[Copyright]

University of California Press

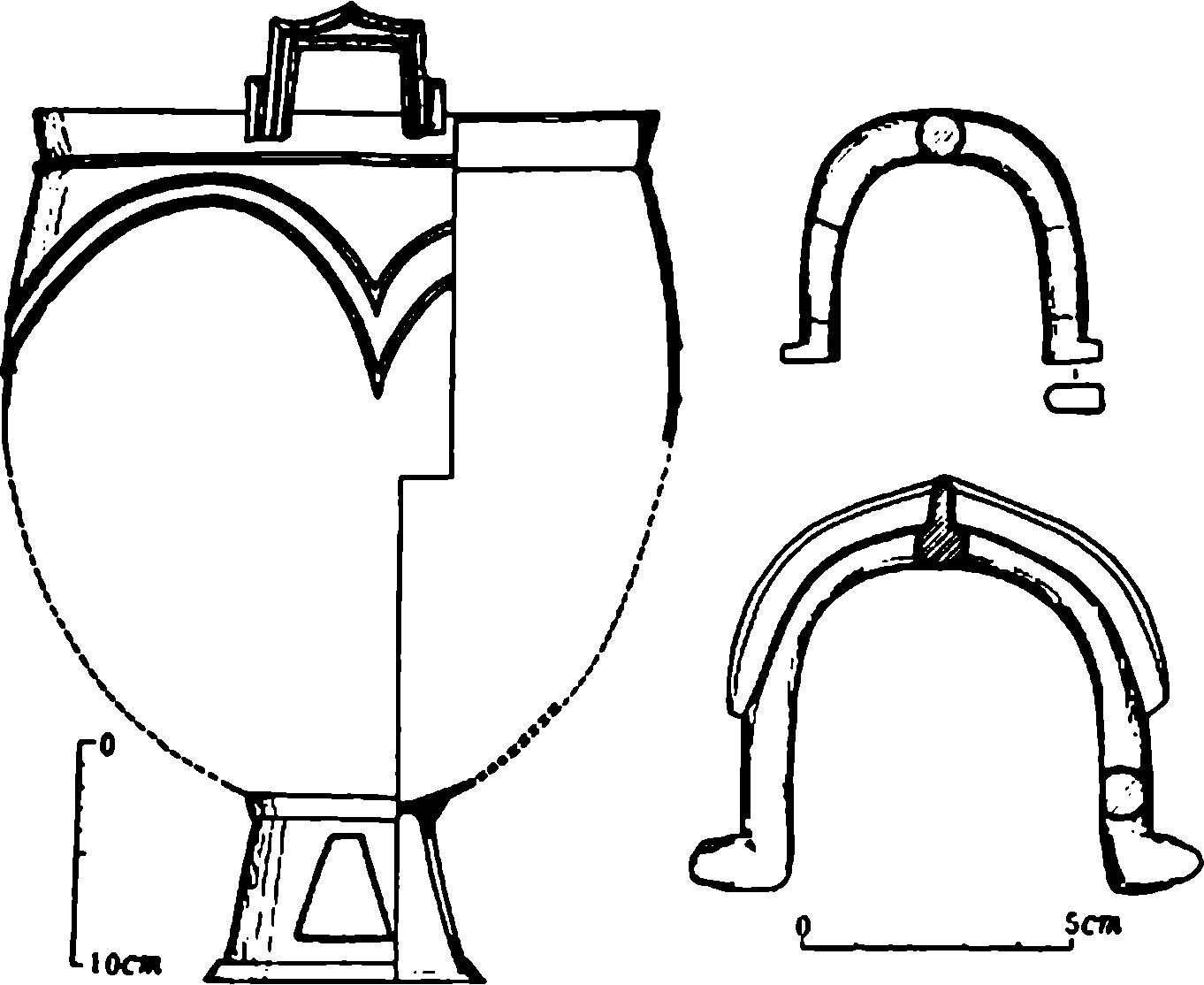

Berkeley and Los Angeles, California

University of California Press, Ltd.

London, England

Copyright © 1973, by

The Regents of the University of California

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 79–94985

International Standard Book Number : 520-01596-7

Designed by James Mennick

Printed in the United States of America

List of Illustrations

FIGURE PAGE

1 A horse with a “hooked” head and bushy tail represented on 205 a bronze plaque from the Ordos region. From Egami 1948, pl. 4.

2 Grave stela from Theodosia in the Crimea with the representation of the deceased mounted on a horse marked with a Sarmatian 212 tamga, first to third centuries a.d. From Solomonik 1957, fig. 1.

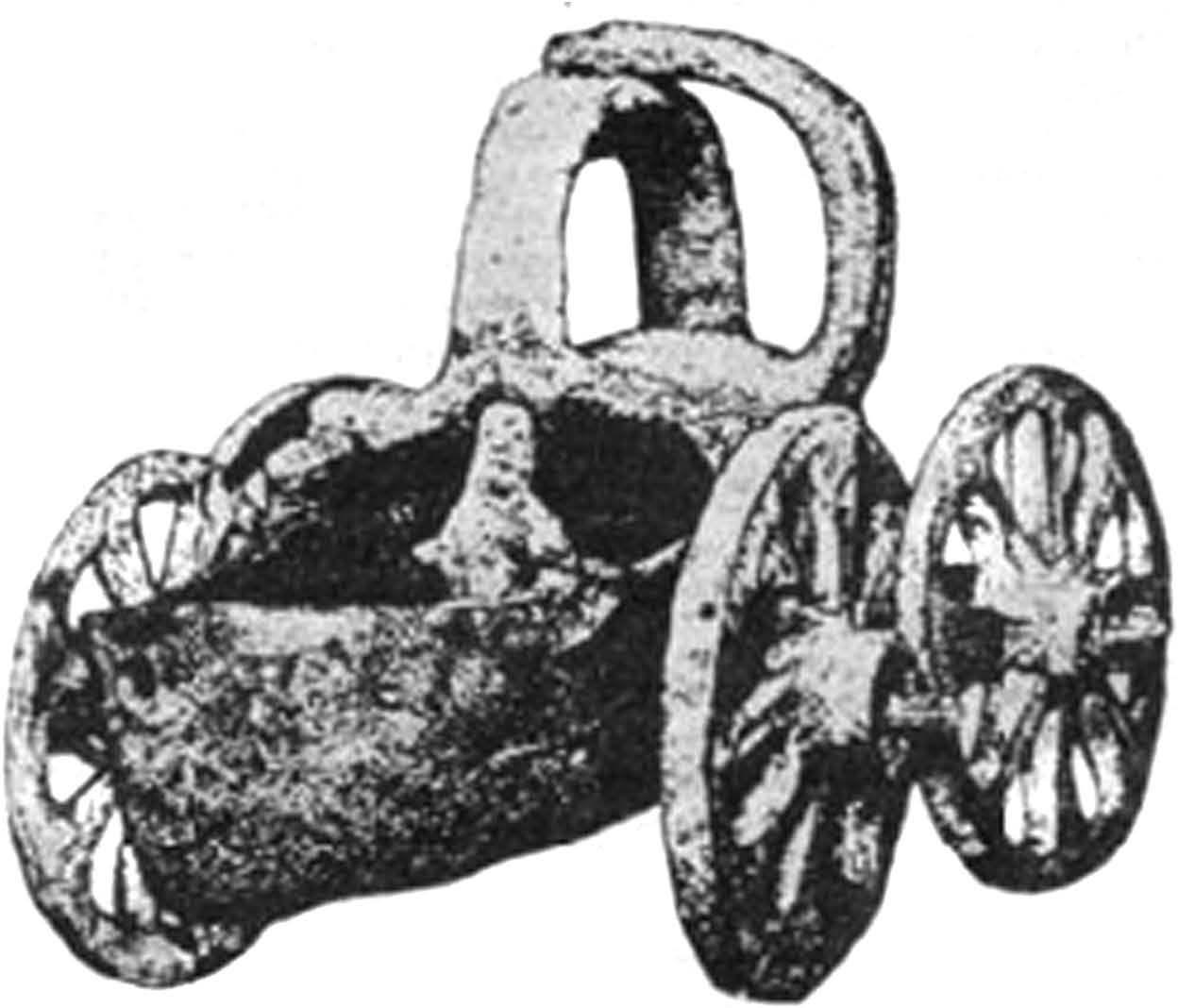

3 Two-wheeled cart represented on a bronze plaque from the Wu-216 huan cemetery at Hsi-ch’a-kou. From Sun Shou-tao 1960, fig. 17.

4 Bronze plaque from Sui-yiian with the representation of a man 217 holding a sword with a ring handle before a cart drawn by three horses. From Rostovtsev 1929, pl. XI, 56.

5A Miniature painting from the Radziwil manuscript showing the wa-218 gons of the Kumans. From Pletneva 1958, fig. 25.

5B Miniature painting from the Radziwil manuscript showing human 218 heads in tents mounted on carts. From Pletneva 1958, fig. 26.

6 Ceramic toy from Kerch showing a wagon of Late Sarmatian type. 219 From Narysy starodav’noi istorii Ukrains’koi RSR 1957, 237.

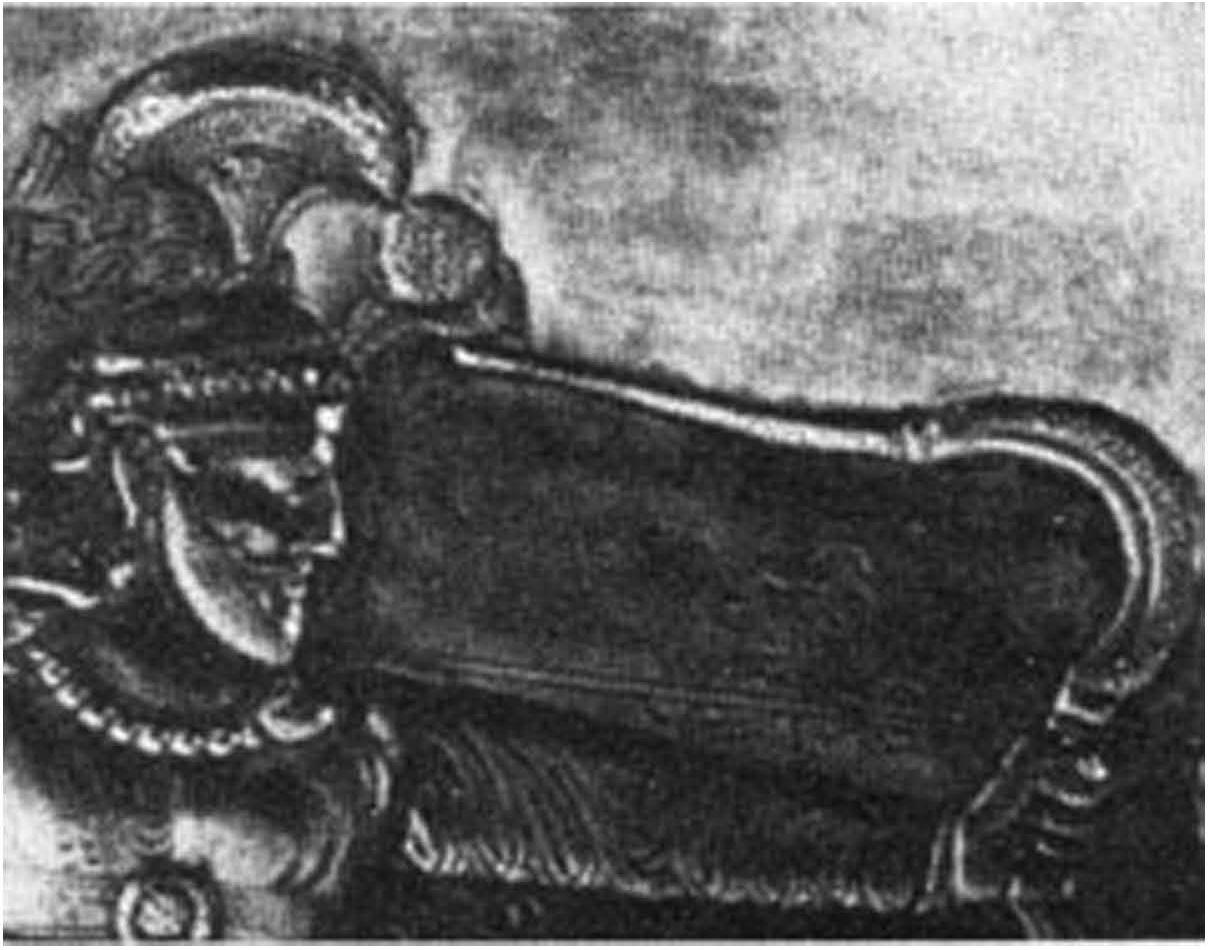

7 Detail of a Sasanian-type silver plate from a private collection. 229 Detail from Ghirshman 1962, fig. 314.

8 Detail of a Sasanian silver plate from Sari, Archaeological Museum, 230 Teheran. Detail from Ghirshman 1962, pl. 248.

9 Silver plate from Kulagysh in the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad. 232 From SPA, pl. 217. “

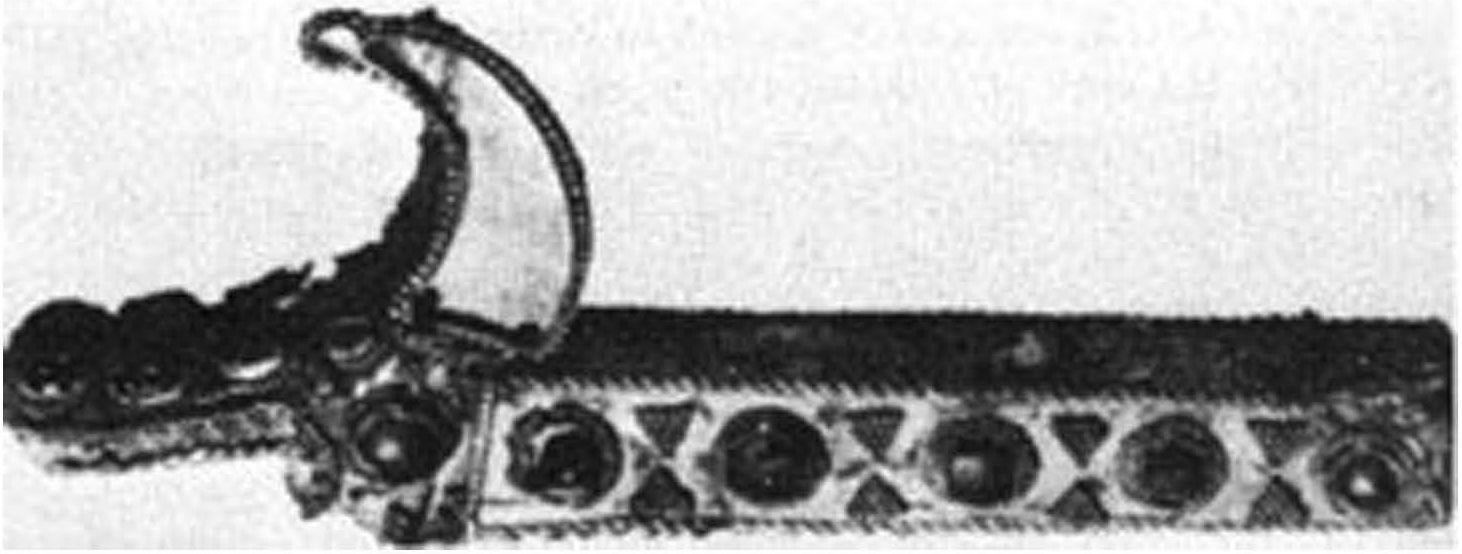

10A Scabbard tip of a sword from Altlussheim near Mainz. From J. 233 Werner 1956, pl. 58:4.

10B Detail of the sword from Altlussheim near Mainz. From J. Werner 234 1956, pl. 38 A.

11 Stone relief from Palmyra, datable to the third century a.d. 235 Ghirshman 1962, pl. 91.

12 Agate sword guard from Chersonese, third century a.d. From 237 Khersonesskii sbornik, 1927, fig. 21.

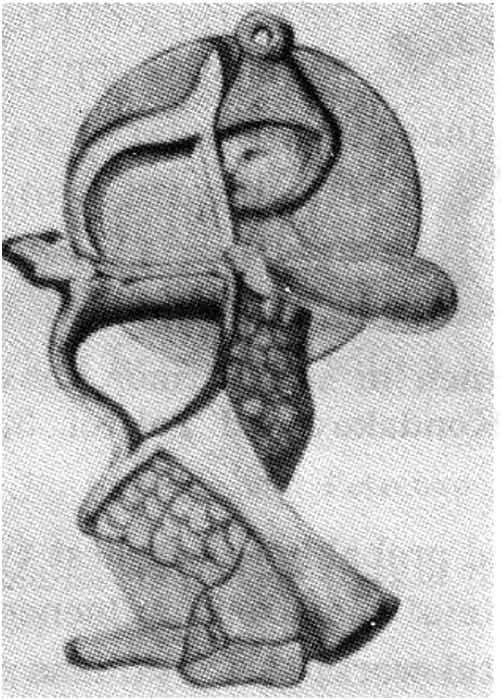

12A Bronze pendant said to have been found in a grave at Barnaul, 243 Altai region, showing a man in scale armor and conical hat with

an hour-glass-shaped quiver, datable to the fourth century a.d.

From Aspelin 1877, no. 327.

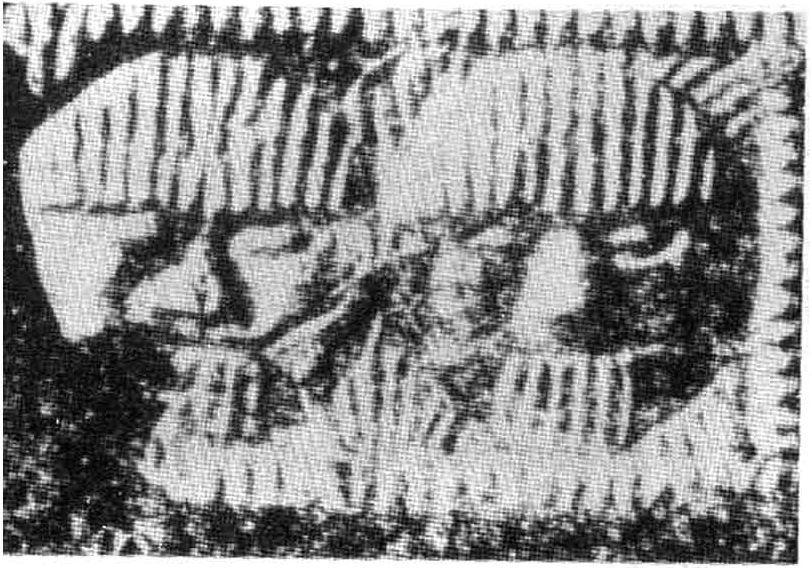

12B Two horsemen in scale armor shown in gold pendants from western 244 Siberia. From Kondakov and Tolstoi, 3, fig. 49.

12C The representation of a Sarmatian member of the Roxolani tribe in 246 a detail of the marble relief from Trajan’s Column, in the Forum of Trajan, Rome. Datable to the second decade of the second century a.d. Photos courtesy Deutsches archaologisches Institut, Rome.

13 Mask-like human heads stamped on gold sheet from a Hunnic burial 281 at Pokrovsk-Voskhod. From Sinitsyn 1936, fig. 4.

14 Mask-like human heads stamped on silver sheet on a bronze phalera 281 from kurgan 17, Pokrovsk. From Minaeya 1927, pl. 2:11.

15 The representation of the head of a Scythian in clay from Transcau-283 casia. Photo courtesy State Historical Museum, Moscow.

16 Bronze mountings from a wooden casket from Intercisa on the Da-284 nube. From Paulovics, AE, 1940.

17 Flat bronze amulet in the shape of an ithyphallic human figure of 286 Sarmatian type. (Source not indicated in the manuscript. — Ed.)

18 Sandstone pillar in the shape of a human head from kurgan at Tri Brata near Elista in the Kalmuk steppe. (Height 1 m.) From Sinitsyn 1956b, fig. 11.

19 Chalk eidola from an Alanic grave at Baital Chapkan in Cherkessia, fifth century a.d. From Minaeva 1956, fig. 12.

20 Chalk figure from a Late Sarmatian grave in Foc§ani, Rumania. (Height ca. 12 cm.) From Morintz 1959, fig. 7.

21 Stone slab at Zadzrost’, near Ternopol’, former eastern Galicia, marked with a Sarmatian tamga. (Height 5.5 m.) From Drachuk, SA 2, 1967, fig. 1.

22 Fragment of a gold plaque from Kargaly, Uzun-Agach, near Alma Ata, Kazakhstan. (About 35 cm. long.) Photo courtesy Akademiia Nauk Kazakhskol SSR.

23 Hunnic diadem of gold sheet, originally mounted on a bronze plaque, decorated with garnets and red glass, from Csorna, western Hungary. (Originally about 29 cm. long, 4 cm. wide.) From Archao-logische Funde in Ungarn, 291.

24A-C Hunnic diadem of gold sheet over bronze plaques decorated 301 with green glass and flat almandines, from Kerch. Photos courtesy Rheinisches Museum, Bildarchiv, Cologne.

25 Hunnic diadem of thin bronze sheet over bronze plaques set with convex glass from Shipovo, west of Uralsk, northwestern Kazakhstan.

From J. Werner 1956, pl. 6:8.

26 Hunnic diadem of gold sheet over bronze plaques set with convex 302 almandines from Dehler on the Berezovka, near Pokrovsk, lower Volga region. From Ebert, RV 13, “Siidrussland,” pl. RV 41 :a.

27 Hunnic diadem of gold sheet over bronze plaques (now lost) set with 303 convex almandines, from Tiligul, in the Romisch-Germanisches Zentralmuseum, Mainz. From J. Werner 1956, pl. 29:8.

28 Bronze circlet covered with gold sheet and decorated with conical 304 “bells” suspended on bronze hooks, from Kara Agach, south of Akmolinsk, central Kazakhstan. (Circumference 49 cm., width ca. 4 cm.) From J. Werner 1956, pl. 31:2.

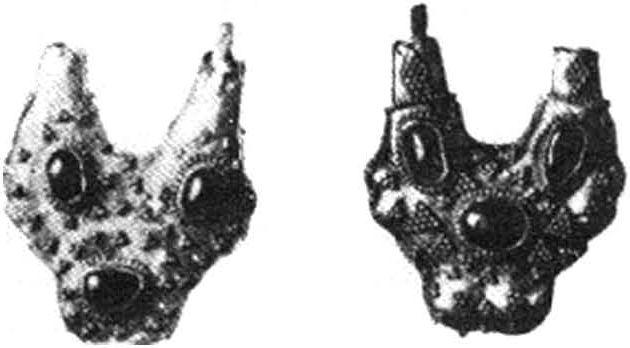

29A Terminal of a gold torque in the shape of a dragon, decorated with 304 granulation and cloisonnd garnets, amber, and mother-of-pearl. From Kara-Agach, south of Akmolinsk, central Kazakhstan. From IAK 16, 1905, p, 34, fig. 2.

29B Gold earrings from Kara-Agach, central Kazakhstan. From IAK 305 16, 1905, fig, 3:a-b.

30 Silver earring decorated with almandines and garnets from kurgan 36, SW group, near Pokrovsk. From Sinitsyn 1936, fig. 10.

31 Fold earring from Kalagya, Caucasian Albania. From Trever 1959, 305 167, fig. 18.

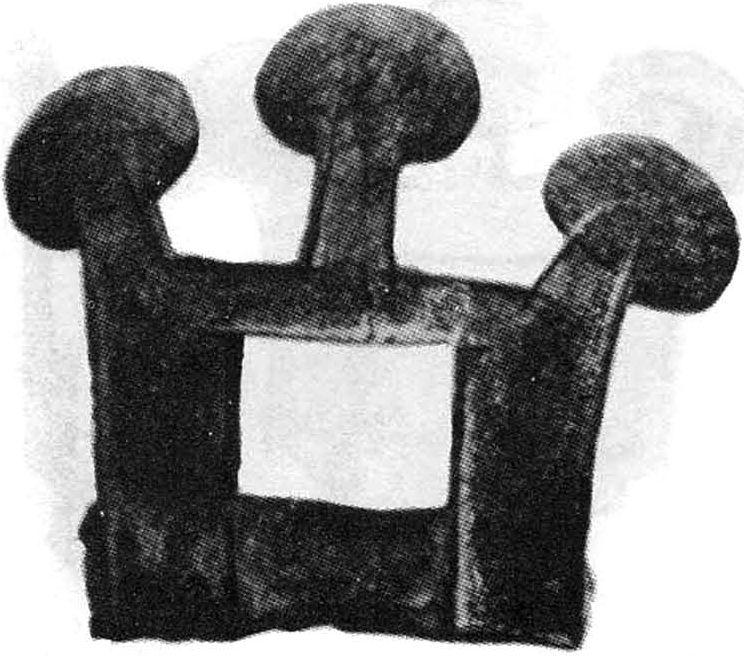

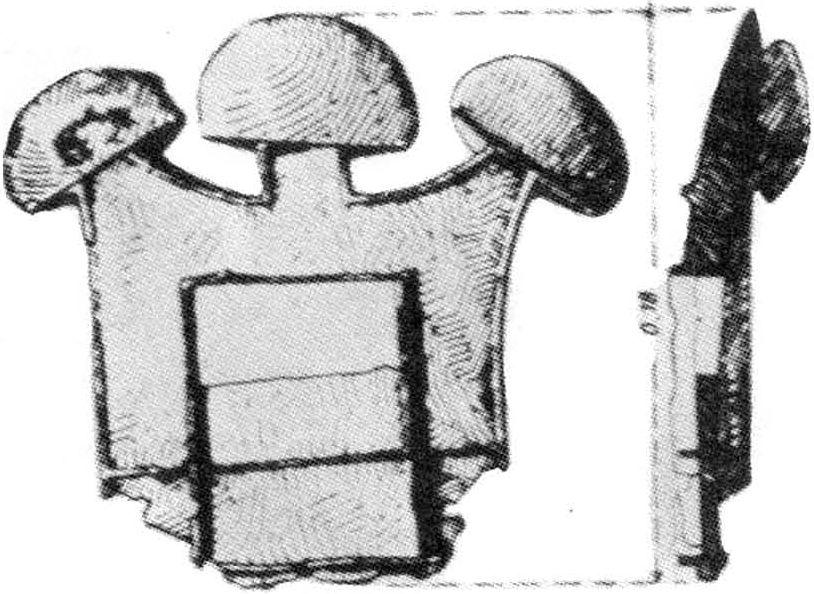

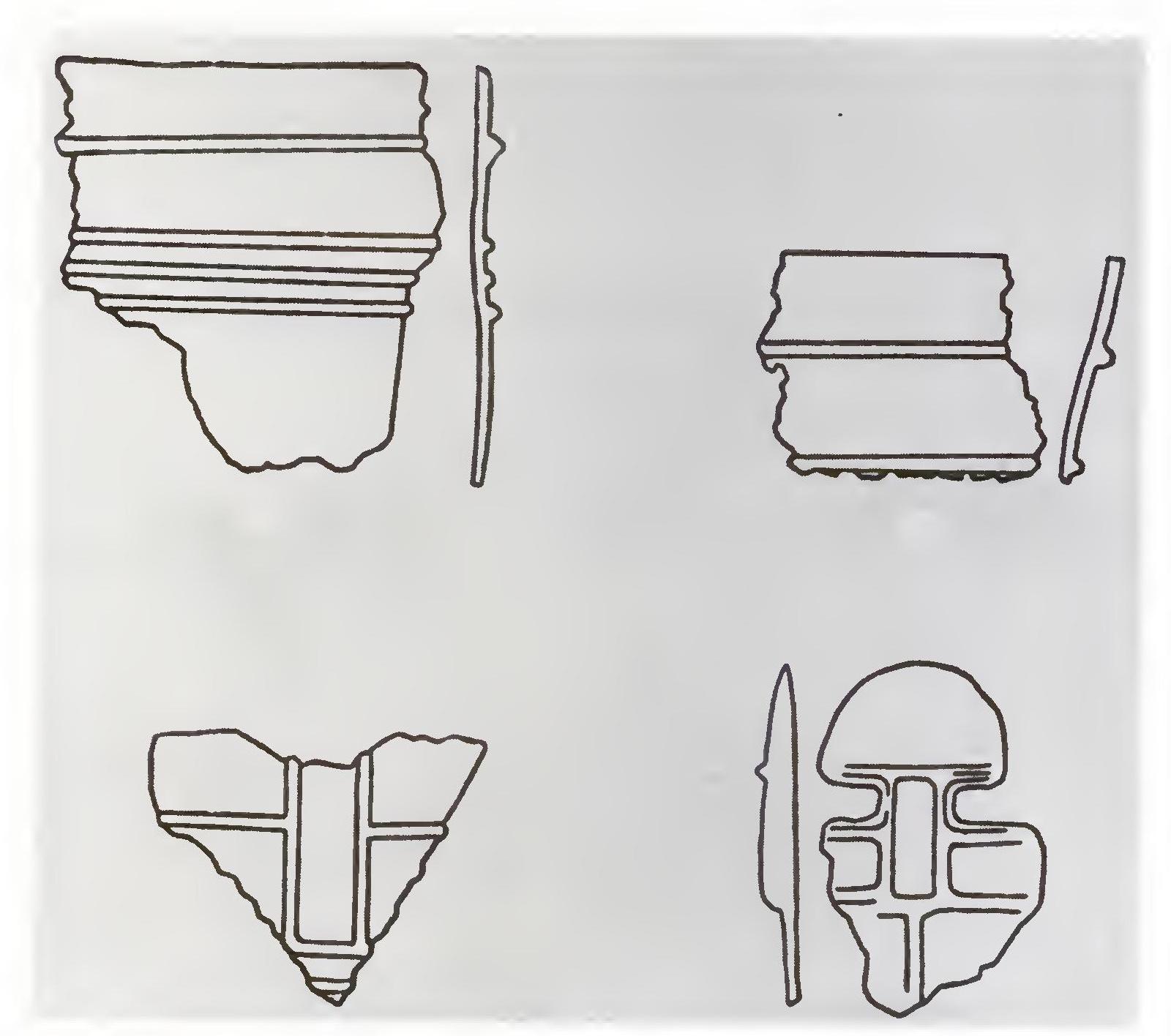

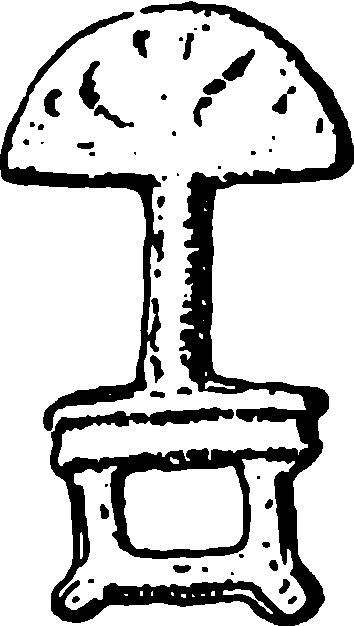

32 Fragment of a bronze lug of a cauldron from BeneSov, near Opava 307 (Troppau), Czechoslovakia. (Height 29 cm., width 22 cm., thickness 1 cm.) From Altschlesien 9, 1940, pl. 14.

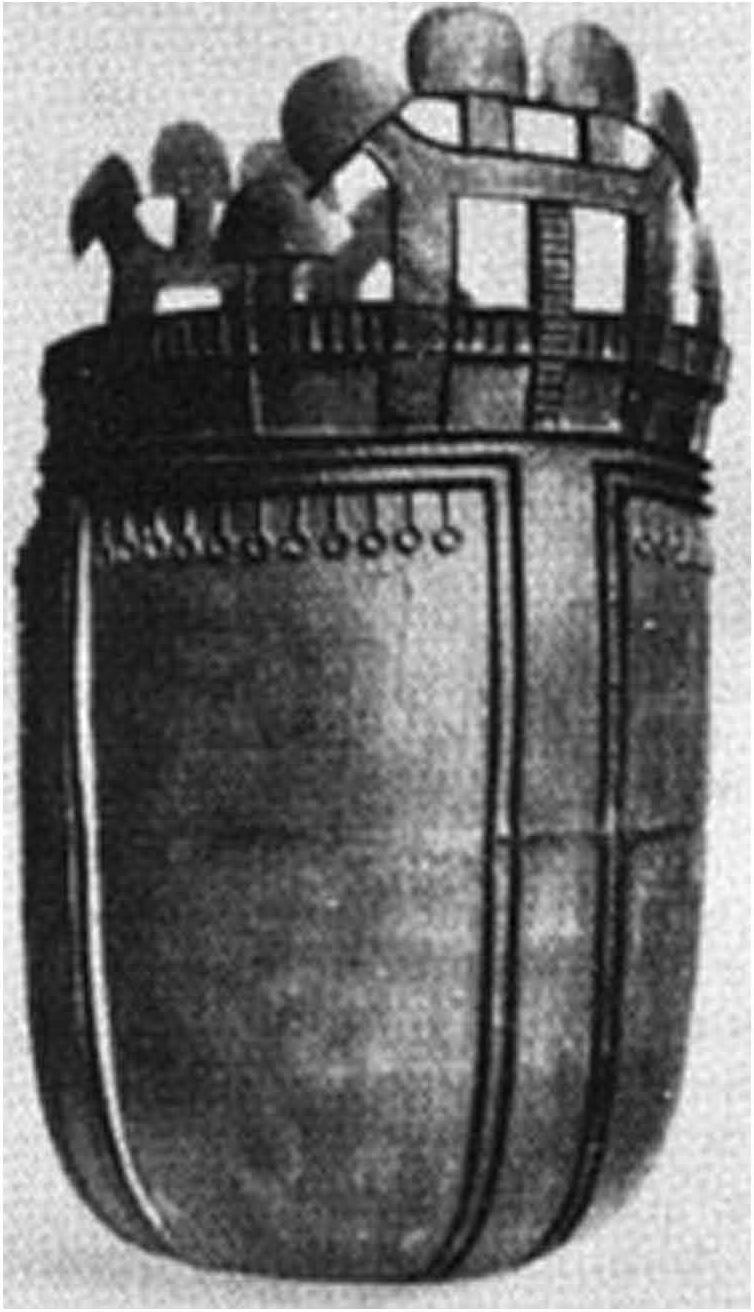

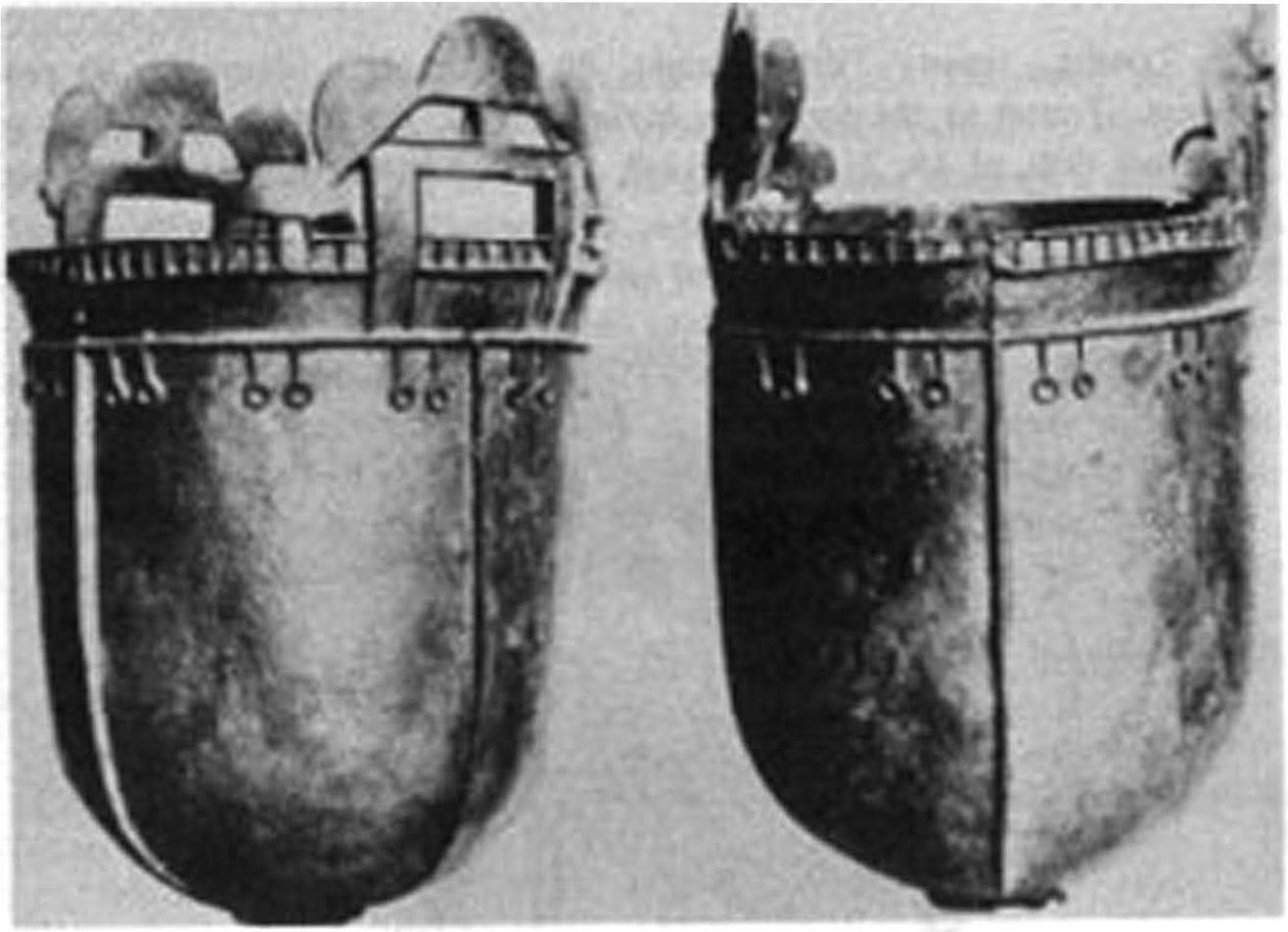

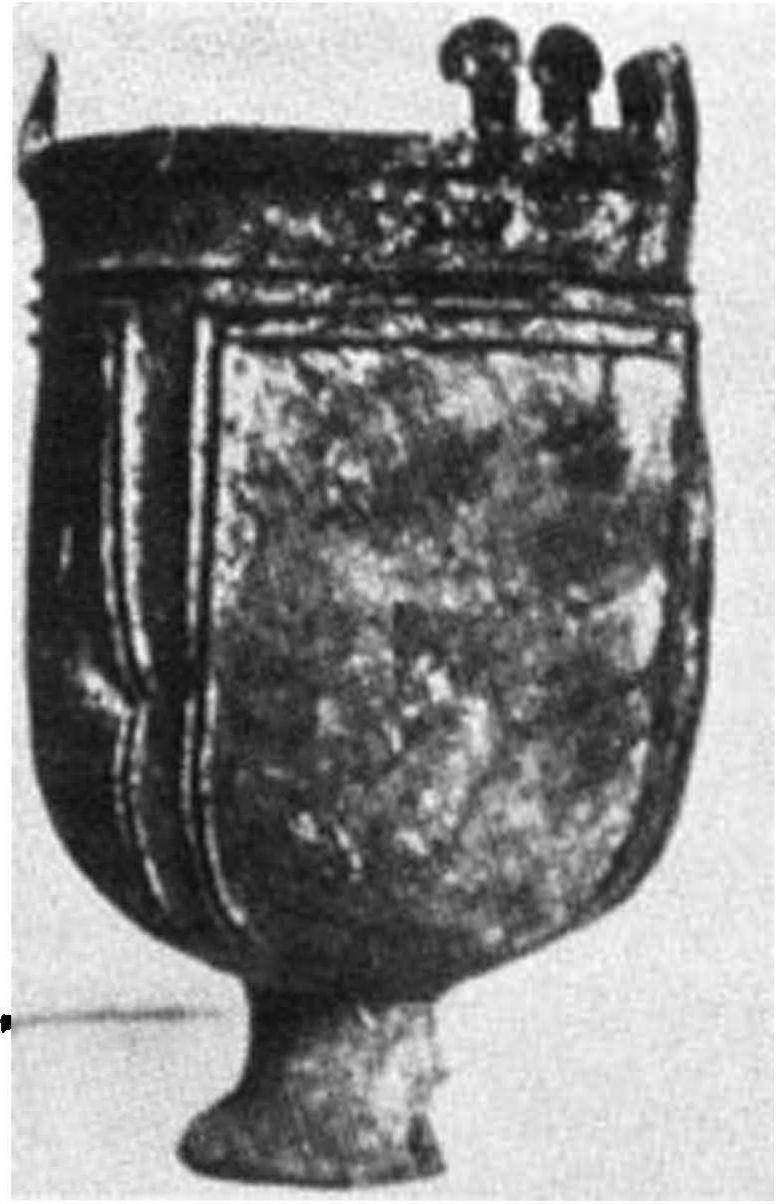

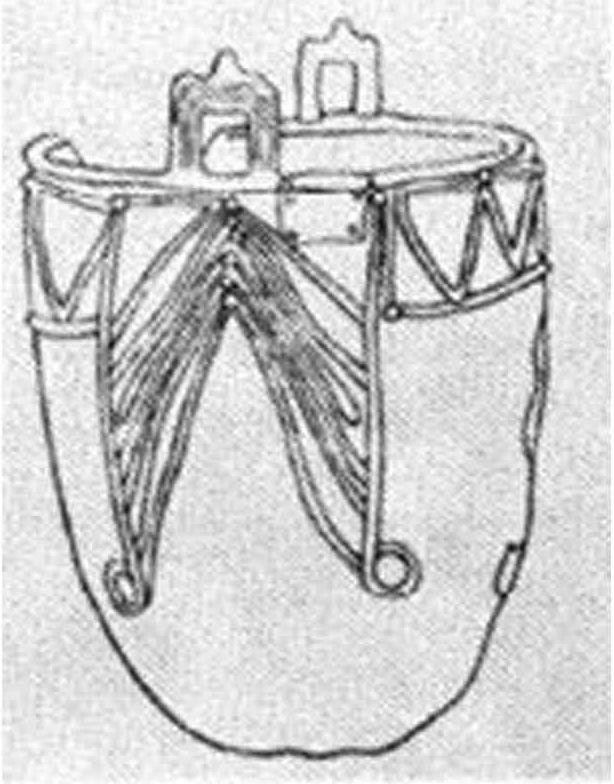

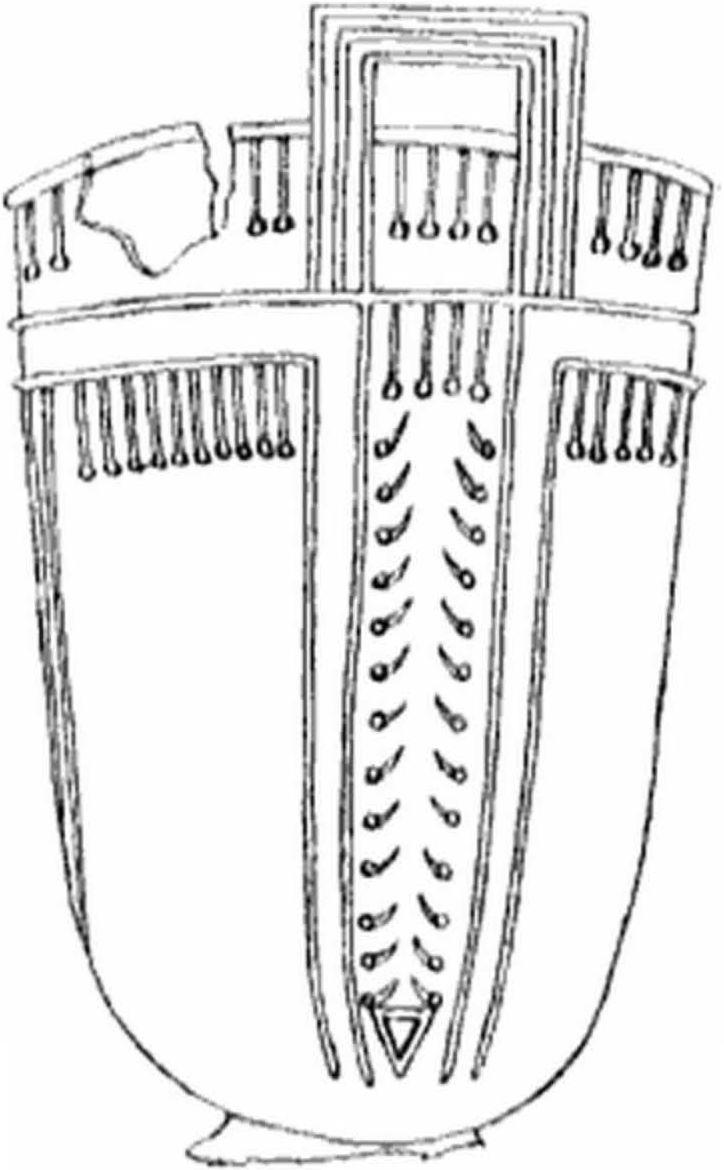

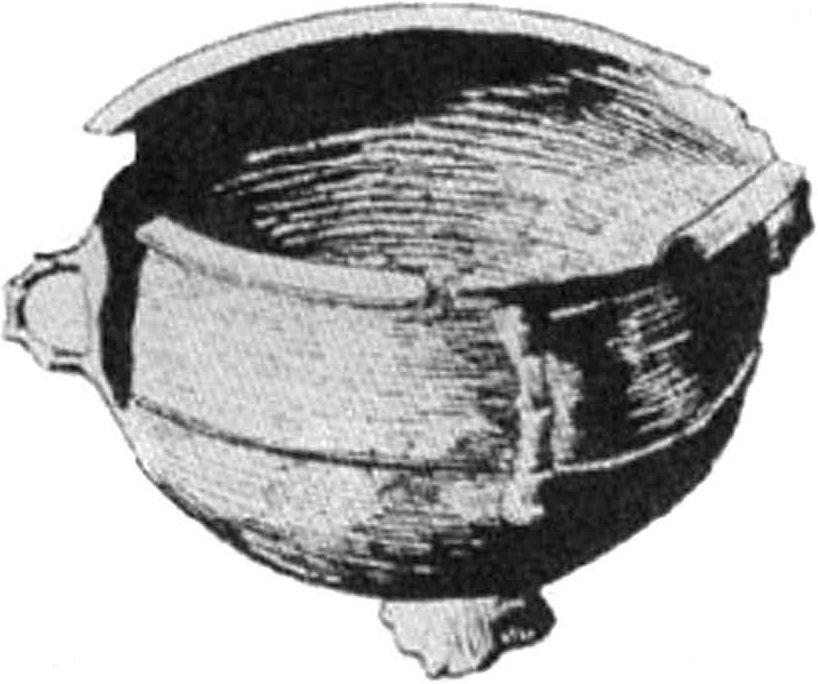

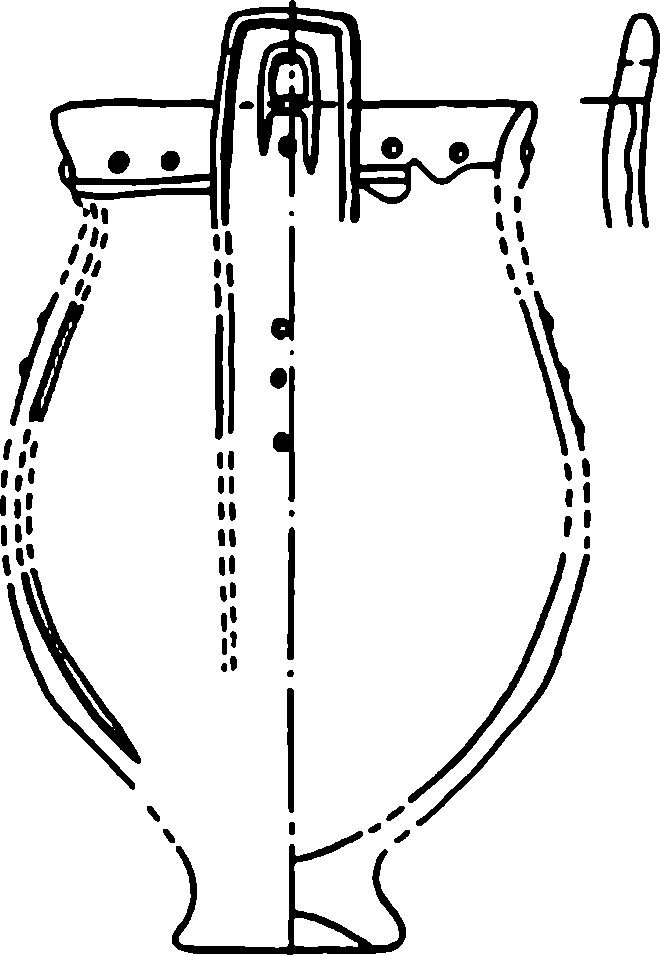

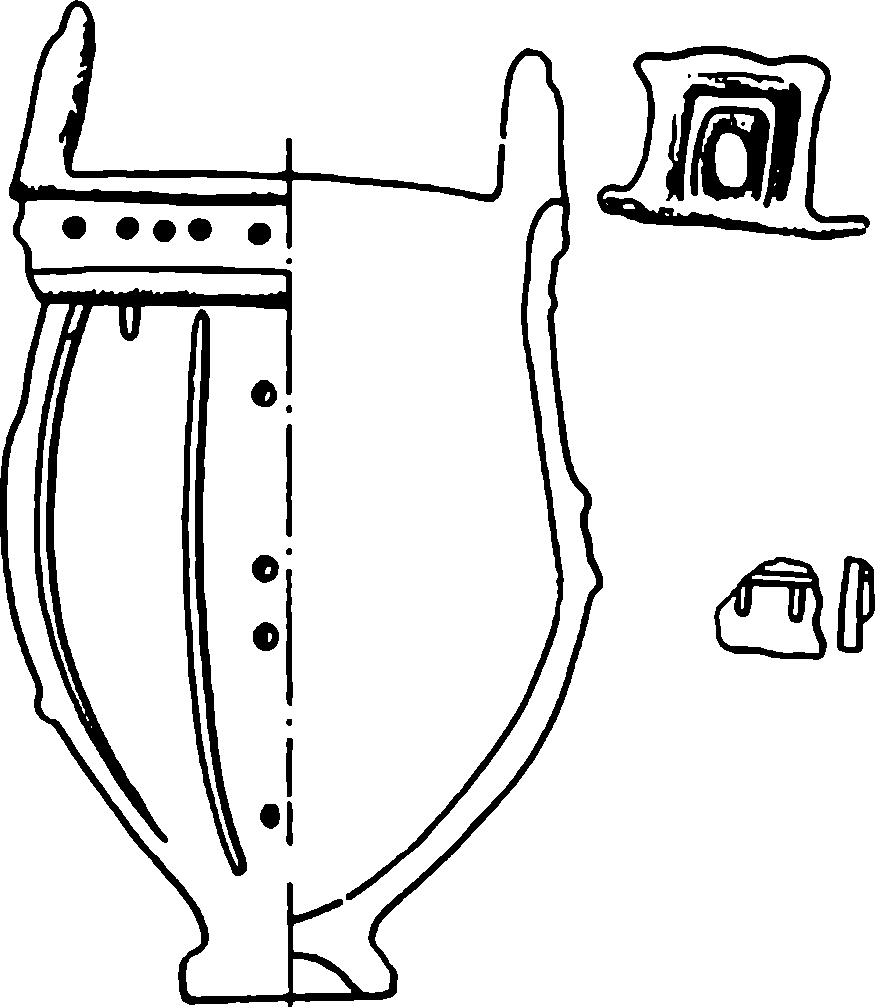

33 Hunnic bronze cauldron Jedrzychowice (Hockricht), Upper 308 Silesia, Poland. (Height 55 cm.) From J. Werner 1956, pl. 27:10.

34 Hunnic bronze cauldron found at the foot of a burial mound at Tortel, 309 Hungary. (Height 89 cm., diam. 50 cm.) From Archaologische Funde in Ungarn, 293.

35 Hunnic bronze cauldron found in a peat bog at Kurdcsibrdk, in the 310 Kapos River valley, Hungary. (Height 52 cm., diam. 33 cm., thickness of wall O.8 cm., weight 16 kg.) From Fettich 1940, pl. 11.

36 Hunnic bronze cauldron from B^ntapuszta, near V^rpalota, Hungary. 311 From Takats, AOH, 1959, fig, t.

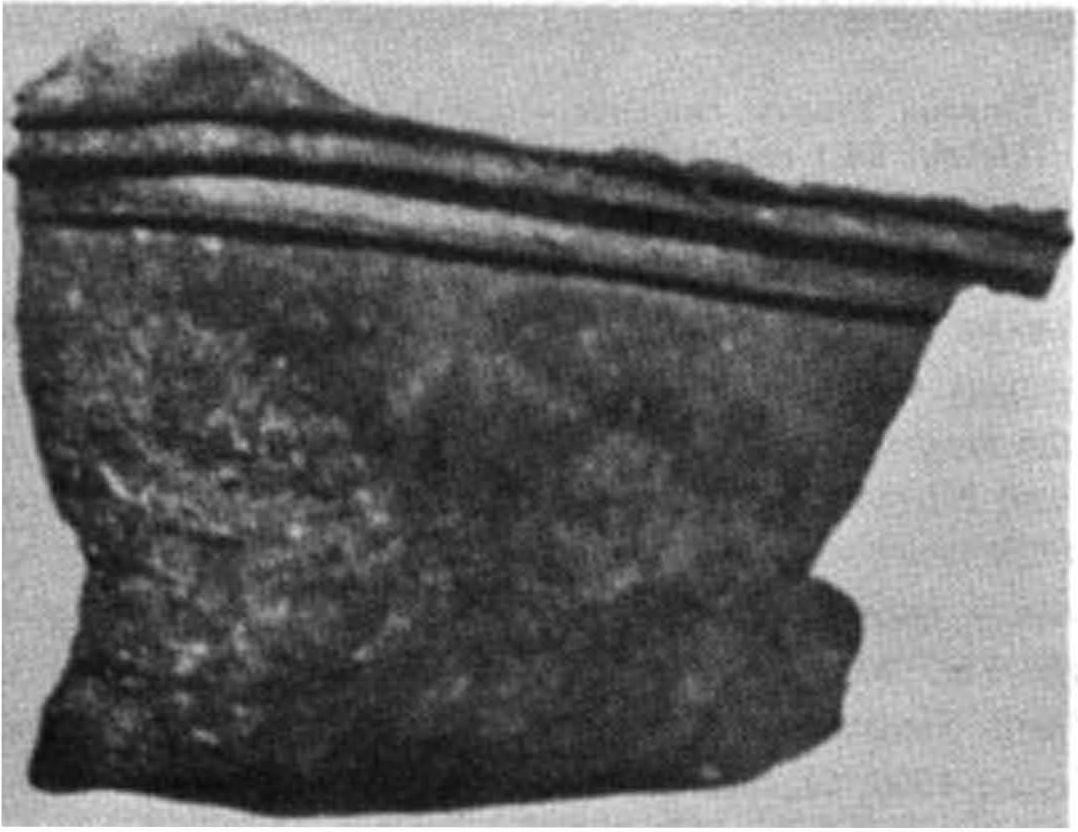

37 Fragment of a bronze cauldron from Dunaujv^ros (Intercisa), 311 Hungary. From Alfoldi 1932, fig. 6.

38 Hunnic bronze cauldron from a lake, Desa, Oltenia region, Rumania. 312 (Height 54.1 cm., diam. 29.6 cm.) From Nestor and Nicolaescu-Plopsor 1937, pls. 3a-3b.

39 Fragment of a bronze lug from a lake, HotSrani, Oltenia region, 313 Rumania. (Height 16.2 cm., width 19.7 cm.) From Nestor and Nicolaescu-Plopsor 1937, pl. 39:1.

40 Fragment of a bronze lug probably from western Oltenia, Rumania. 313 (Height 8.4 cm.) From Nestor and Nicolaescu-Plopsor 1937, pl. 39:2.

41 Fragment of a bronze lug found near the eastern shore of Lake Motistea, from Bosneagu, Rumania. (Height 18 cm.) From Mitrea 1961, 1–2?

42 Fragments of a lug and walls of a bronze cauldron from Celei, 314 Muntenia, Rumania. From Takdts 1955, fig. 13:a-d.

43 Hunnic bronze cauldron from Shestachi, Moldavian SSR. From 315 Polevoi, Istoriia Moldavskoi SSR, pl. 53.

44 Bronze cauldron from Solikamsk, Perm region, USSR. (Height 9 cm.) 316 From Alfoldi 1932, fig. 5.

45 Bronze cauldron found in thesand near the Osoka brook, Ul’yanovsk 317 region, USSR. (Height 53.2 cm., diam. 31.2 cm., weight 17.7kg.) From Polivanova, Trudy VII AS 1, 39, pl. 1.

46 Bronze cauldron from Verkhnii Konets, Komi ASSR. From Hampel, 318 Ethnologische Mittheilungen aus Ungarn 1897, 14, fig. 1.

Bronze cauldron from Ivanovka, gubernie Ekaterinoslav, USSR. From Fettich 1953, pl. 36:4.

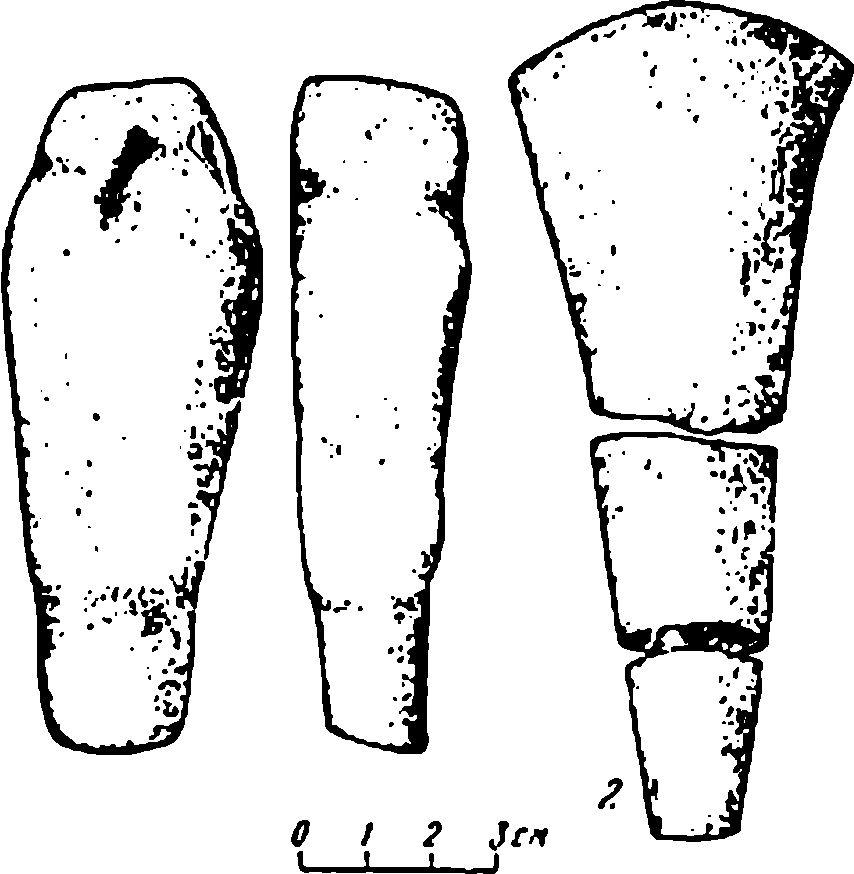

Bronze cauldron found near Lake Teletskoe, in the High Altai, now in the State Historical Museum, Moscow. (Height 27 cm.,diam. 25–27 cm.) Photo courtesy State Historical Museum, Moscow. Fragment of a bronze lug from Narindzhan-baba, Kara-Kalpak ASSR. From Tolstov 1948, fig. 74a.

Fragment of a bronze lug, allegedly found “on the Catalaunian battlefield.” (Height 12 cm., width 18 cm.) From Takdts 1955, fig. l:a-b.

Bronze cauldron from Borovoe, northern Kazakhstan. From Bernshtam 1951a, fig. 12.

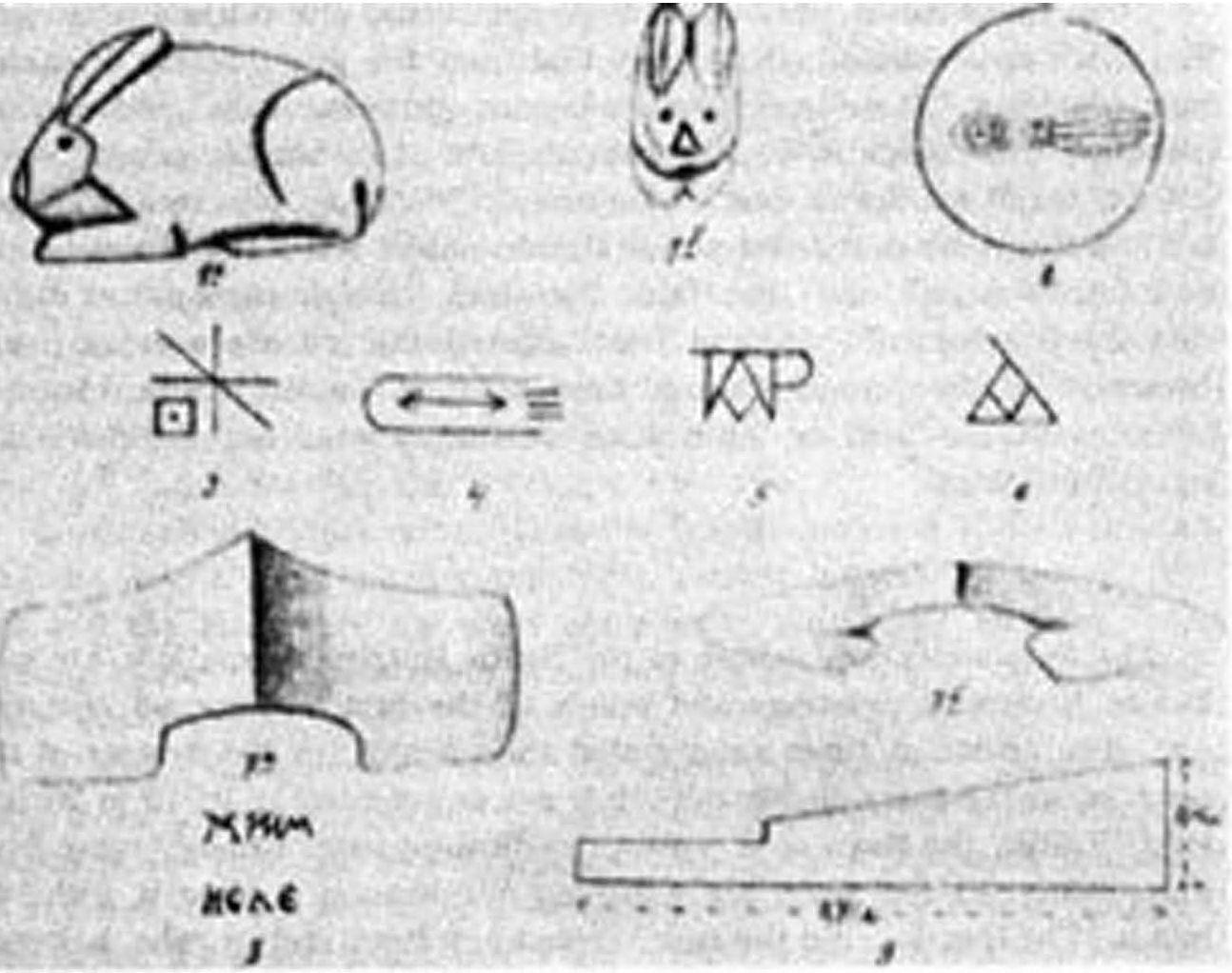

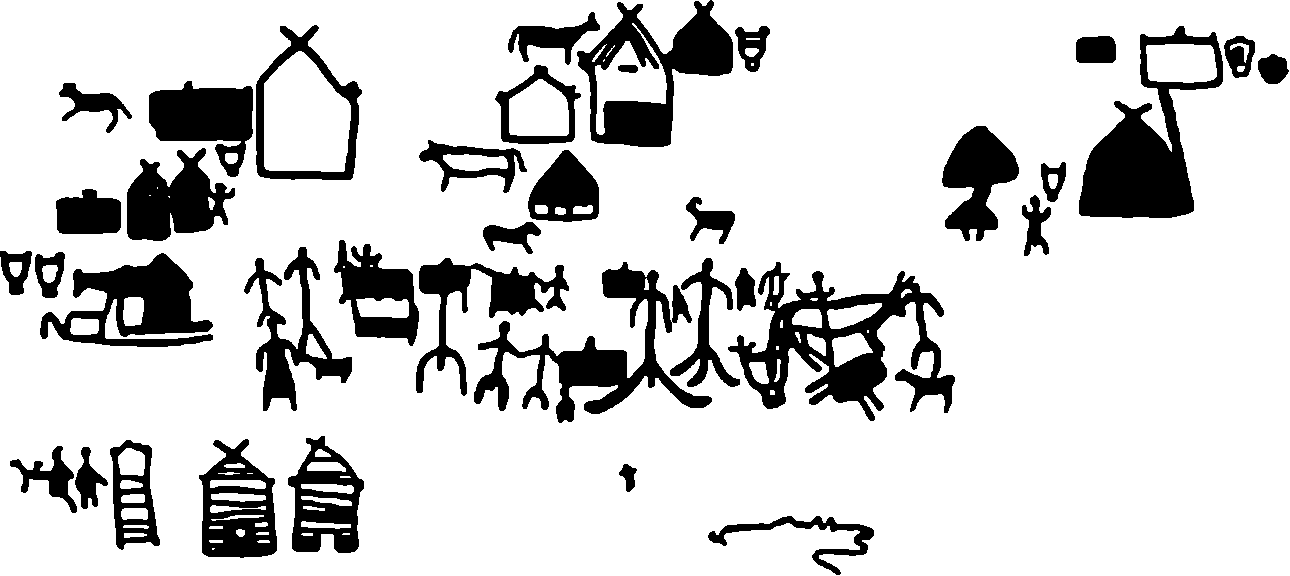

The representation of a cauldron in a detail of a rock picture from Pis annaya Gora in the Minusinsk area. From Appelgren-Kivalo, fig. 85. Representation of cauldrons in a rock picture from Bol’shaya Boyarskaya pisanitsa, Minusinsk area. From Ddvlet, SA 3, 1965, fig. 6. Bronze cauldron of a type associated with Hsiung-nu graves at Noin Ula and the Kiran River. From Umehara 1960, p. 37. Ceramic vessel from the Gold Bell Tomb at Kyongju, Korea, showing the manner in which cauldrons were transported by nomads. From Government General Museum of Chosen 1933, Museum Exhibits Illustrated V.

Clay copy of a Hunnic cauldron of the Verkhnii Konets type (see above, fig. 46), from the “Big House,” Altyn-Asar, Kazakhstan. (Height 40 .cm.) From Levina 1966, fig. 7:37–38.

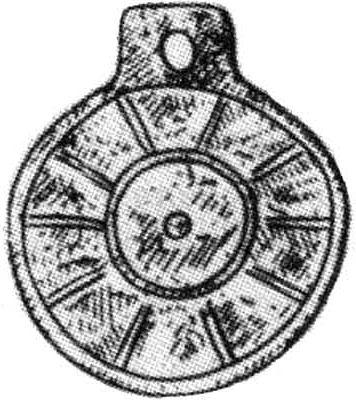

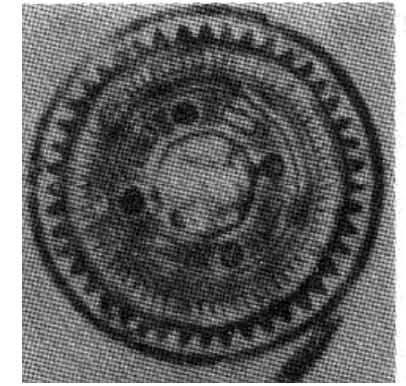

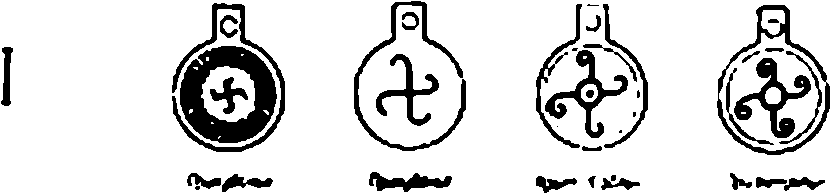

Chinese mirror of the Han period found in burial 19, on the Torgun River, lower Volga region. From Ebert, R V, «Siidrussland,»pl. 40: c:b. A Sarmatian bronze disc in the shape of a pendant-mirror, of a type found in the steppes betweenVolga and lower Danube, from the first century b.c. to the fourth century a.d. From Sinitsyn 1960, fig. 18:1.

Bronze mirror of a type similar to that shown on fig. 58, but provided with a tang that was presumably fitted into a handle. From Gushchina, SA, 2, 1962, fig. 2:5.

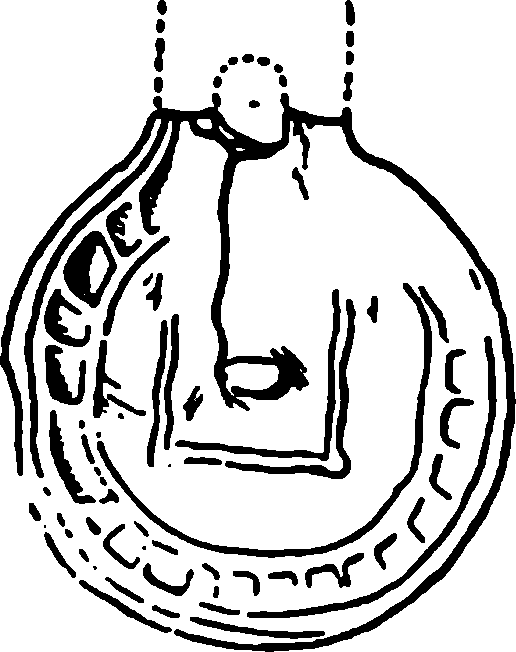

Bronze pendant-mirror from the cemetery at Susly, former German Volga Republic. From Rau, Hugelgraber, 9, fig. la.

Bronze pendant-mirror from the cemetery at Susly, former German Volga Republic. From Rykov 1925, 68.

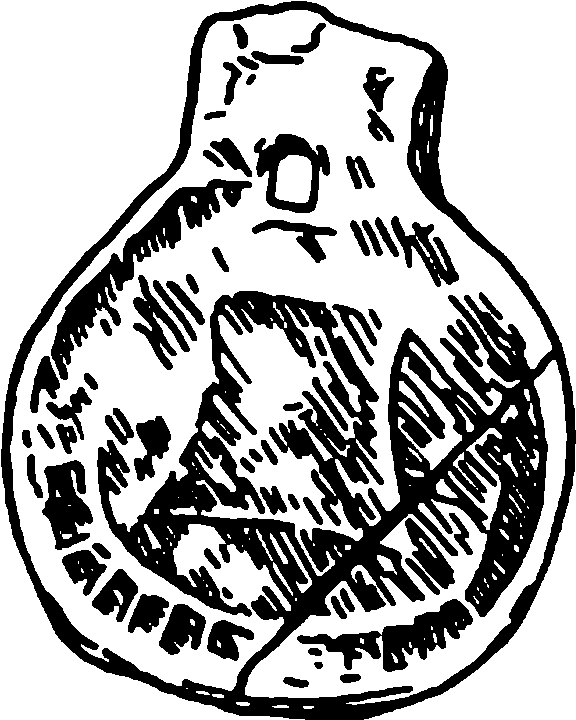

Bronze pendant-mirror from Alt-Weimar, kurgan D12. From Rau, Ausgrabungen, 30, fig. 22b.

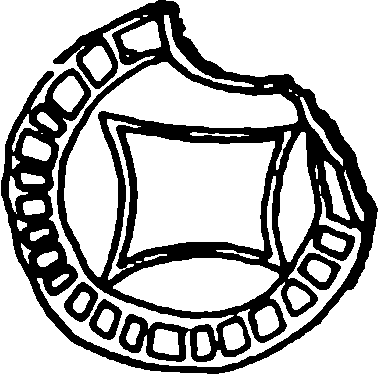

Bronze pendant-mirror from kurgan 40 in Berezhnovka, lower Eruslan, left tributary of the Volga. From Khazanov 1963, fig. 4:9. Bronze pendant-mirror from kurgan 23, in the “Tri Brata” cemetery, near Elista, Kalmuk ASSR. From Khazanov 1963, fig. 4:8. Bronze pendant-mirror from the lower Volga region. From Khazanov 1963, fig. 4:6.

Bronze pendant-mirror from a catacomb burial at Alkhaste, northwestern Caucasus. From Vinogradov 1963, fig. 27.

An imitation of a Chinese TLV mirror from Lou-Ian. From Umehara, O bei, 39, fig. 7.

68 Small bronze mirror with simplified decoration from Lo-yang. 347 From Lo-yang ching 1959, 80.

69 Small bronze mirror with simplified decoration from Lo-yang. 347 From Lo-yang ching 1959, 82.

70 Bronze mirror from Mozhary, Volgograd region, now in the Hermitage Museum, Leningrad, datable to about a.d. 200. (Diam. 7.4 cm.) From Umehara 1938, 55.

71 Bronze mirror from Kosino in Slovakia. From Eisner, Slovensko 349 v praveku 1933, fig. 2:7.

72 Bronze pendant-mirrors from the Dnieper and Volga regions. From 350 Solomonik 1959, fig. 6.

73 Sarmatian imitation of a Chinese mirror (cf. the example from 351 Lo-yang, above, fig. 69), from Norka, lower Volga region. From Berkhin 1961, fig. 2:2.

74 Small bronze plaque showing a horseman with prominent cheekbones 370 and full beard, from Troitskovavsk in Transbaikalia. From Petri, Dalekoe proshloe Pribaikal’ia 1928, fig. 39.

75 Bronze plaque from the Ordos region, showing a man of Europoid 371 stock with wide open eyes and moustache. British Museum. Photo G. Azarpay.

Foreword

Few scholars would care to risk their reputation in taking on the monumental task of straightening out misconceptions about the Huns, and incidentally about the many peoples related to them, allied with them, or confused with them. At the foundation there are philological problems of mindboggling proportions in languages ranging from Greek to Chinese; above that, an easy but solidly professional familiarity with primary sources for the history of both Eastern and Western civilizations in many periods is required; finally, a balanced imagination and a prudent sense of proportion are needed to cope with the improbabilities, contradictions, and prejudices prevailing in this field of study. The late Professor Otto Maenchen-Helfen worked on this immense field of research for many years, and at his death in 1969 left an unfinished manuscript. This is the source of the present book.

Maenchen-Helfen differed from other historians of Eurasia in his unique competence in philology, archaeology, and the history of art. The range of his interests is apparent from a glance at his publications, extending in subject from “Das Marchen von der Schwanenjungfrau in Japan” to “Le Cicogne di Aquileia,” and from “Manichaeans in Siberia” to “Germanic and Hunnic Names of Iranian Origin.” He did not need to guess the identities of tribes, populations, or cities. He knew the primary texts, whether in Greek or Russian or Persian or Chinese. This linguistic ability is particularly necessary in the study of the Huns and their nomadic cognates, since the name “Hun” has been applied to many peoples of different ethnic character, including Ostrogoths, Magyars, and Seljuks. Even ancient nomadic people north of China, the Hsiung-nu, not related to any of these, were called “Hun” by their Sogdian neighbors. Maenchen-Helfen knew the Chinese sources that tell of the Hsiung-nu, and thus could evaluate the relationship of these sources to European sources of Hunnic history.

His exceptional philological competence also enabled him to treat as human beings the men whose lives underlie the dusty textual fragments that allude to them, and to describe their economy, social stratifications, modes of transportation and warfare, religions, folklore, and art. He could create a reliable account of the precursors of the Turks and Mongols, free of the usual Western prejudice and linguistic limitations.

Another special competence was his expertise in the history of Asian art, a subject that he taught for many years. He was familiar with the newest archaeological discoveries and knew how to correlate them with the available but often obscure philological evidence.

To define distinctive traits in the art of a people as elusive as the Huns requires familiarity with the disjointed array of archaeological materials from the Eurasian steppe and the ability to separate materials about the Huns from a comparable array of materials from neighboring civilizations. To cite only one example of his success in coping with such thorny problems, Maenchen-Helfen’s description of technical and stylistic consistencies among metal articles from Hunnic tombs in widely separated localities dispels the myth of supposed Hunnic ignorance of metal-working skills.

Archaeological evidence also plays a critical role in the determination of the origin of the Huns and their geographical distribution in ancient and early medieval times, as well as the extent of Hunnic penetration into eastern Europe and their point of entry into the Hungarian plain. Maenchen-Helfen saw clearly how to interpret the data from graves and garbage heaps to yield hypotheses about the movements of peoples. “He believed in the spade, but his tool was the pen,” he once said about another scholar — a characterization that perfectly fits Maenchen-Helfen himself. Burial practices of the Huns and their associates indicate that Hunnic weapons generally originated in the east and were transmitted westward, while the distribution of loop mirrors found in association with artificially deformed skulls — a Hunnic practice — gives proof of Hunnic penetration into Hungary from the northeast. (An unpublished find of a sword of the Altlussheim type recently discovered at Barnaul in the Altai region, east Kazakhstan SSR, now in the Hermitage Museum, is a forceful argument in favor of Maenchen-Helfen’s assumption about the eastern connections of this weapon. See A. Urmanskii, “Sovremennik groznogo Attily,” A Itai 4 [23], Barnaul 1962, pp. TS- 93.) His findings define and bring to life the civilization of one of the most shadowy peoples of early medieval times.

Maenchen-Helfen’s account opens in medias res, with a tribute to that admirable Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus, whose view of the Hunnic incursions was, despite his prejudices, in some respects clearer than that of Western historians. Abrupt as this beginning may seem, the author perhaps intended the final version of his book to begin with such a striking evaluation of a basic text. In so doing, he underlined the necessity for sharp and well-reasoned criticism of the sources of the history of the Huns. From the beginning these people were denigrated and “demonized” (to use his own term) by European chroniclers and dismissed as avatars of the eternal but faceless barbarian hordes from the east, against whom vigilance was always necessary, but whose precise identity was of little importance. The bulk of the book discusses the history and civilization of the “Huns proper,” those so familiar — and yet so unfamiliar — to Europeans. (Here we use the term “civilization” purposefully, since reports of this folk have tended to treat them as mere barbaric destroying agents — “vandals” spilling blood across the remnants of the declining Roman Empire. Maenchen-Helfen saw them with a clearer vision.)

The style is characteristically dense with realia. Maenchen-Helfen had no need to indulge in generalizations (read “unfounded guesses”). But he was not absorbed in details to the exclusion of a panoramic view. He saw, and presents to us here, the epic character of the great drama that took place on the Eurasian stage early in our era, the clash of armies and the interaction of civilizations. The book is a standard treatise not likely to be superseded in the predictable future.

Guitty Azarpay

Peter A. Boodberg

Edward H. Schafer

Editor’s Note

In early January 1969 Professor Otto Maenchen-Helfen brought a beautifully typed manuscript from the Central Stenographic Bureau of the university to the University of California Press. It seemed to represent the final result of his monumental study of the Huns, to which he had devoted many years of research and travel. A few days later, on January 29, he died. In the memorial speeches at the Faculty Club in Berkeley, several friends mentioned that he had truly completed his lifework, and that his manuscript was ready to go to press.

The impression that the delivered manuscript pages constituted the complete manuscript turned out to be erroneous. Mr. Maenchen had brought only the first of presumably two batches of manuscript. The chapters representing that second batch were not in final form at the time of his death, the bibliography was missing, footnotes were indicated but the sources not stated, an introduction and a complete preface were lacking, the illustrations were scattered in boxes and desk drawers and not identified. There was no table of contents, and the chapters were not numbered; although some groupings of chapters are suggested in the extant part of the author’s preface, it was not clear in what order he intended to arrange his work.

On Mrs. Maenchen’s suggestion I searched the author’s study and eventually found a tentative draft of a contents page. It was of unknown age, and contained revisions and emendations that required interpretation. On the basis of this precious page, the “Rosetta Stone of the manuscript,” the work was organized.

Several chapters mentioned in this page were not in final form. But three-ring folders in the author’s study, neatly filed on shelves, bore the names of most missing chapter headings. The contents of these folders were in various stages of completion. Those that appeared to be more or less finished except for final editing were incorporated into the manuscript; also sections which, although not representing complete chapters but apparently in final form, were included and placed where they seemed to fit mostly logically. In several instances, different drafts of the same subject were found, and it was necessary to decide which was the most recent one. Occasionally, also, only carbon copies of apparently finished sections were in the folders.

Errors in judgment in these editorial and compiling activities cannot be ruled out, but wherever doubts existed about the preferred version or the placement of a fragment the material was excluded. Many notes, isolated pages, and drafts (frequently written by hand, with various kinds of emendations) remain in the author’s study, including undoubtedly valuable research results.

In retyping the parts of the manuscript that existed only in draft form with many emendations and hand-written corrections, every effort was made not to introduce errors, such as misspellings of foreign words, especially in the notes and bibliography. For errors that undoubtedly slipped in nevertheless, the author is not responsible.

Although the work addresses itself to specialists, it is of interest to a broader range of educated readers who cannot, however, be expected to be familiar with some of the events, persons, institutions, and sources the author takes for granted. For these readers Professor Paul Alexander has provided an introduction; in deference to the author it was placed as “background” at the end of the book, but it may usefully be read first, as a preparation for the text.

The editorial preparation of the manuscript required the help of an unusually large number of persons, reflecting the wide range of the author’s competence. The Russian references were checked by the author’s friend, the late Professor Peter A. Boodberg, who delivered the corrected pages just a few days before his death in the summer of 1972. The Chinese references were checked or supplied by Professor Edward H. Schafer, also a friend of the author. The Latin and Greek passages were translated by Professor J. K. Anderson and Dr. Emmy Sachs; Mr. Anderson also faithfully filled lacunae in the footnotes and unscrambled mixups resulting from duplicated or omitted footnote numbers. Professors Talat Tekin and Hamid Algar checked and interpreted Turkish references. Professor Joachim Werner of Munich counseled on the Altlussheim sword. Questions about Gothic, Iranian, Hungarian, Japanese, and Ukrainian references or about historical (ancient and medieval) and many other aspects of the text that needed interpretation were answered by a long list of scholars contributing their services to the cause.

Miss Guitty Azarpay (to whom the author used to refer fondly as his favorite student) selected and painstakingly identified the illustrations. She also verified references with angelic patience.

The formidable task of compiling a bibliography on the basis of an incomplete set of cards and of the text itself was performed by Mrs. Jane Fontenrose Cajina. The author’s working cards, assembled over many years, were not yet typed in uniform style, many entries were missing, and many lacked essential information. For Russian transcriptions in the bibliography and bibliographical footnotes (but not in the text), the Library of Congress system was used.

The map was drawn by Mrs. Virginia Herrick under the supervision of Professor J. K. Anderson. The index was prepared by Mrs. Gladys Castor.

The editor is indebted to all these many competent and sympathetic helpers; clearly, without their devotion the conversion of the Maenchen papers into the present volume would not have been possible.

Max Knight

Fragments from the Author’s Preface

[Among the author’s papers were several fragments, partly written in pencil, bearing the notation “for the preface,” and evidently intended to be worked into a final draft. He may have wished to say more; all we found is presented below.—Ed.]

The author of the present volume, in his early seventies, may make use of the privilege, usually granted to men in the prime of their senility, to say a few words about himself, in this case the sources of his interest in the Huns. All my life I have been fascinated by the problems of the frontier. As a boy I dug Roman copper coins along the remnants of the earthen walls that, as late as the seventeenth century, protected Vienna, my native town, from the East. Two blocks from the house in which I was born there still stood in my youth a house above whose gate a Turkish stone cannon ball from the siege of 1529 was immured. My grandfather spent a year in jail for fighting in 1848 with the revolutionaries against the Croatian mercenaries of the Habsburgs. My doctoral dissertation dealt with the “barbarian” elements in Han lore. In 1929 I lived for months in the tents of Turkishspeaking nomads in northwestern Mongolia, where the clash between “higher civilization,” represented by Tibetan Lamaism, and the “primitive” beliefs of the Turks was strikingly visible. In Kashmir, at Harwan, I marveled at the artificially deformed skulls on the stamped tiles of Kushan times, those skulls that had impressed me so much when I first saw them in the museum in Vienna and that I had measured as a student. In Nepal I had another chance to see the merging of different civilizations in a borderland. I spent many days in the museum at Minusinsk in southern Siberia studying the “Scythian” bronze plaques and cauldrons. In Kabul I stood in awe before the inscription from Surkh Kotal: it brought back to me the problems of the barbarians at China’s border about which I had written a good deal in previous years. Attila and his avatars have been haunting me as far back as I can recall.

In the history of the Western world the eighty years of Hun power were an episode. The Fathers assembled in council at Chalcedon showed a sublime indifference to the barbarian horsemen who, only a hundred miles away, were ravaging Thrace. They were right. A few years later, the head of Attila’s son was carried in triumphal procession through the main street of Constantinople.

Some authors have felt that they had to justify their studies of the Huns by speculating on their role in the transition from late antiquity to the Middle Ages. Without the Huns, it has been maintained, Gaul, Spain, and Africa would not, or not so soon, have fallen to the Germans. The mere existence of the Huns in eastern Central Europe is said to have retarded the feudalization of Byzantium. This may or may not be true. But if a historical phenomenon were worth our attention only if it shaped what came after it, the Mayans and Aztecs, the Vandals in Africa, the Burgundians, the Albigenses, and the crusaders’ kingdoms in Greece and Syria would have to be wiped off the table of Clio. It is doubtful that Attila “made history.” The Huns “perished like the Avars” — “sginuli kak obry,” as the old Russian chroniclers used to say when they wrote about a people that had disappeared forever.

It seems strange, therefore, that the Huns, even after fifteen hundred years, can stir up so much emotion. Pious souls still shudder when they think of Attila, the Scourge of God; and in their daydreams German university professors trot behind Hegel’s Weltgeist zu Pferde. They can be passed over. But some Turks and Hungarians are still singing loud paeans in praise of their great ancestor, pacifier of the world, and Gandhi all in one. The most passionate Hun fighters, however, are the Soviet historians. They curse the Huns as if they had ridden, looting and killing, through the Ukraine only the other day; some scholars in Kiev cannot get over the brutal destruction of the “first flowering of Slavic civilization.”

The same fierce hatred burned in Ammianus Marcellinus. He and the other writers of the fourth and fifth centuries depicted the Huns as the savage monsters which we still see today. Hatred and fear distorted the picture of the Huns from the moment they appeared on the lower Danube. Unless this tendentiousness is fully understood — and it rarely is — the literary evidence is bound to be misread. The present study begins, therefore, with its reexamination.

The following chapters, dealing with the political history of the Huns, are not a narrative. The story of Attila’s raids into Gaul and Italy need not be told once more; it can be found in any standard history of the declining Roman Empire, knowledge of which, at least in its outlines, is here taken for granted. However, many problems were not even touched on and many mistakes were made by Bury, Seeck, and Stein. This statement does not reflect on the stature of these eminent scholars, for the Huns were on the periphery of their interests. But such deficiencies are true also for books which give the Huns more room, and even for monographs. The first forty or fifty years of Hun history are treated in a cursory manner. The sources are certainly scanty though not as scanty as one might believe; for the invasion of Asia in 395, for instance, the Syriac sources flow copiously. Some of the questions that the reign of Attila poses will forever remain unanswered. Others, however, are answered by the sources, provided one looks, as I have, for sources outside the literature that has been the stock of Hunnic studies since Gibbon and Le Nain de Tillemont. The discussions of chronology may at times tax the patience of the reader, but that cannot be helped. Eunapius, who in his Historical Notes also wrote about the Huns, once asked what bearing on the true subject of history inheres in the knowledge that the battle of Salamis was won by the Hellenes at the rising of the Dog Star. Eunapius has his disciples in our days also, and perhaps more of them than ever. One can only hope that we will be spared a historian who does not care whether Pearl Harbor came before or after the invasion of Normandy because “in a higher sense” it does not matter.

The second part of the present book consists if monographs on the economy, society, warfare, art, and religion of the Huns. What distinguishes these studies from previous treatments is the extensive use of archaeological material. In his Attila and the Huns Thompson refuses to take cognizance of it, and the little to which Altheim refers in Geschichte dec Hunnen he knows at second hand. The material, scattered through Russian, Ukrainian, Rumanian, Hungarian, Chinese, Japanese, and latterly also Mongolian publications, is enormous. In recent years archaeological research has been progressing at such speed that I had to modify my views repeatedly while I was working on these studies. Werner’s monumental book on the archaeology of Attila’s empire, published in 1956, is already obsolete in some parts. I expect, and hope, that the same will be true of my own studies ten years from now.

Although aware of the dangers in looking for parallels between the Huns and former and later nomads of the Eurasian steppes, I confess that my views are to a certain, I hope not undue, degree influenced by my experiences with the Tuvans in northwestern Mongolia, among whom I spent the summer of 1929. They are, or were at that time, the most primitive Turkish-speaking people at the borders of the Gobi.

I possibly will be criticized for paying too little attention to what Robert Gobi calls the Iranian Huns: Kidara, White Huns, Hepthalites, and Hunas. In discussing the name “Hun” I could not help speculating on their names. But this was as far as I dared go. The literature on these tribes or peoples is enormous. They stand in the center of Altheim’s Geschichte der Hunnen, although he practically ignores the numismatic and Chinese evidence, on which Enoki has been working for so many years. Gobi’s Dokumente zur Geschichte der iranischen Hunnen in Baktrien und Indien is the most thorough study of their coins and seals and, on this basis, of their political history. And yet, there remain problems to whose solution I could not make a meaningful contribution. I have neither the linguistic nor the paleographic knowledge to judge the correctness of the various, often entirely different, readings of the coin legends. But even if someday scholars wrestling with this recalcitrant material do come to an agreement, the result will be relatively modest. The Huna Mihirakula and Toramana will remain mere names. No settlement, no grave, not so much as a dagger or a piece of metal exists that could be ascribed to them or any other Iranian Huns. Until the scanty and contradictory descriptions of their life can be substantially supplemented by finds, the student of the Attilanic Huns will thankfully take cognizance of what the students of the so-called Iranian Huns can offer him; but there is little he can use for his research. A recently discovered wall painting in Afrosiab, the ancient Samarkand, seems to show the first light in the darkness. The future of the Hephthalite studies lies in the hands of the Soviet and, it is hoped, the Chinese archaeologists. ’Ev ftvOcp yaq aAijOeia.

I am aware that some chapters are not easy reading. For example, the one on the Huns after Attila’s death draws attention to events seemingly not worth knowing, to men who were mere shadows; it jumps from Germanic sagas to ecclesiastical troubles in Alexandria, from the Iranian names of obscure chieftains to an earthquake in Hungary, from priests of Isis in Nubia to Middle Street in Constantinople. I will not apologize. Some readers surely will find the putting together of the scattered pieces as fascinating as I did, and I frivolously confess to an artistic hedonism which to me is not the least stimulus for my preoccupation with the Dark Ages. On a higher level, to pacify those who, with a bad conscience, justify what they are doing — Historical Research with capital letters — may I point out that I fail to see why the history of, say, Baja California is more respectable than, say, that of the Huns in the Balkans in the 460’s. Sub specie aeternitatis, both dwindle into nothingness.

Anatole France, in his Opinions of Jerome Coignard, once told the wonderful story of the young Persian prince Zemire, who ordered his scholars to write the history of mankind, so that he would make fewer errors as a monarch enlightened by past experience. After twenty years, the wise men appeared before the prince, king by then, followed by a caravan composed of twelve camels each bearing 500 volumes. The king asked them for a shorter version, and they returned after another twenty years with three camel loads, and, when again rejected by the king, after ten more years with a single elephant load. After yet five further years a scholar appeared with a single big book carried by a donkey. The king was on his death bed and sighed, “I shall die without knowing the history of mankind. Abridge, abridge I” “Sire,” replied the scholar, “I will sum it up for you in three words: They were born, they suffered, they died I”

In his way, the king, who did not want to hear it all, was right. But as long as men, stupidly perhaps, want to know “how it was,” there may be a place for studies like the present one. Dixi et salvaui animam meam ....

0. M.-H.

Author’s Acknowledgments (Fragments)

[The author left some pencil jottings of names on several slips of paper under headings indicating that he wished to acknowledge them in the preface. Some are not legible, others lack initials. They are consolidated here, initials added when known, and the spelling of unidentified names as close as the handwriting permitted. Within the various countries, the order is random; the list of country names includes France, Rumania, Taiwan, and Korea, but the names of the scholars whom the author undoubtedly intended to acknowledge under these headings are lacking. The fragments include acknowledgments of help received from the East Asiatic Library and the Interlibrary Borrowing Service of the University of California. The notes must have been written at various times throughout the years, and it is obvious that the list is not complete.—Ed.]

In Austria: R. Gobi, Hancar.

In England: Sir Ellis Minns, E. G. Pulleyblank.

In Germany: J. Werner, K. Jettmar, Tauslin.

In Hungary: Z. Takats, L. Ligeti, D. Czallany, Gy. Moravcik, K. Csegledy, E. Liptak.

In Italy: M. Bussagli, P. Daffina, L. Petech.

In Japan: Namio Egami, Enoki, Ushida.

In Soviet Union: K. V. Golenko, V. V. Ginsburg, E. Lubo-Lesnichenko, C. Trever, A. Mantsevich, M. P. Griaznov, L. P. Kyzlasov, I. A. Zadneprovsky, I. Kozhomberdiev, M. Saratov, A. P. Okladnikov, S. S. Sorokin, B. A. Litvinsky, I. V. Sinitsyn, Gumilev, Belenitsky, Stavisky.

In Sweden: B. Karlgren.

In Switzerland: K. Gerhart, I. Hubschmid.

In United States: P. Boodberg, E. Schafer, R. Henning, A. Alfoldi, R. N. Frye, E. Kantorowicz, L. Olschki, K. H. Menges, N. Poppe, I. Sevcenko.

I. The Literary Evidence

The chapter on the Huns written by the Roman historian Ammianus Marcellinus (330–400 a.d.) is an invaluable document.{1} Coming from the pen of “the greatest literary genius which the world has seen between Tacitus and Dante,”[1] it is also a stylistic masterpiece. Ammianus’ superiority over the other writers of his time who could not help mentioning the Huns becomes evident from their statements about the first appearance of the savage hordes in the northern Balkan provinces. They tell us in a few scanty words that the Goths were driven from their sites by the Huns; some add the story of a doe which led the Huns across the Cimmerian Bosporus. And this is all. They did not care to explore the causes of the catastrophe of Adrianople, that terrible afternoon of August 9, 378, when the Goths annihilated two-thirds of the Roman army, else they would have found that “the seed and origin of all the ruin and various disasters”[2] were the events that had taken place in the transdanubian barbaricum years before the Goths were admitted to the empire. They did not even try to learn who the Huns were and how they lived and fought.

It is instructive to compare the just quoted words of Ammianus with the following passage by the historian-theologian Paulus Orosius (fl. 415 a.d), St. Augustine’s disciple:

In the thirteenth year of the reign of Valens, that is, in the short interval of time that followed the wrecking of the churches by Valens and the slaughtering of the saints throughout the East, that root of our miseries simultaneously sent up a very great number of shoots. The race of the Huns, long shut off by inaccessible mountains, broke out in a sudden rage against the Goths and drove them in widespread panic from their old homes.”[3]

If the Arian heresy of Valens was the root of all evils and the attack of the Huns on the Goths only a shoot, then it was clearly a waste of time and effort to occupy oneself with the Huns. There was even the danger that by looking too closely at gesia diaboli per Hunnos one might lose sight of the devil himself. Orosius pays attention only to supernatural agents, God or the demons. Unconcerned about the antecedents of a happening or its consequences unless they could be used for theological lessons, Orosius, and with him all the Christian authors in the West, showed no interest in the Huns. Ammianus called the battle of Adrianople another Cannae.[4] He never doubted, even when all seemed lost, that every Hannibal would find his Scipio, convinced that the empire would last to the end of the world:[5] “To these I set no boundary in space or time; unlimited power I have given them.” (His ego nee metas reriim nex tempora pono: imperium sine fine dedi.[6]) Among the Christians, Rufinus was the only one who could say that the defeat of Adrianople was “the beginning of the evil for the Roman Empire, then and from then on.”[7] The others saw in it only the triumph of orthodoxy, indulging in lurid descriptions of the way in which the accursed heretic Valens perished. Orosius adduced the death of the unfortunate emperor as proof for the oneness of God.

Demonization

Possibly the lack of interest in the Huns had still another reason: the Huns were demonized early. When in 364 Hilary of Poitiers predicted the coming of the Antichrist within one generation,[8] he repeated what during the two years of Julian’s reign many must have thought. But since then Christ had conquered, and only an obdurate fanatic like Hilary could see in the emperor’s refusal to unseat an Arian bishop the sign of the approaching end of the world. Even those who still adhered to the chiliasm of the pre-Constantine church, and took the highly respected Divinae institutiones of Lactantius as their guide to the future, did not expect to hear themselves the sound of Gabriel’s trumpet. “The fall and ruin of the world will soon take place, but it seems that nothing of the kind is to be feared as long as the city of Rome stands intact.”[9]

The change set in early in 387. Italy had not been invaded by barbarians since Emperor Aurelian’s time (270–275). Now it suddenly was threatened by an “impure and cruel enemy.” Panic spread through the cities; fortifications were hastily improvised.[10] Ambrose, who shortly before had lost his brother Saturus, found consolation in the thought that he was “taken away that he might not fall in the hands of the barbarians.... that he might not see the ruin of the whole earth, the end of the world, the burial of relatives, the death of fellow-citizens.” It was the time which the prophets had foreseen, “when they felicitated the dead and lamented the living” (gratulabantur mortuis et vivos plangent).[11] After Adrianople, Ambrose felt that “the end of the world is coming upon us.” War, pestilence, famine everywhere. The final period of the world’s history was drawing to its close. “We are in the wane of the age.”[12]

In the last decade of the fourth century, an eschatological wave swept over the West from Africa to Gaul. The Antichrist already was born, soon he would come to the throne of the empire.[13] Three more generations, and the millennium would be ushered in, but not before untold numbers would have perished in the horrors which preceded it; the hour of judgment drew nearer, the signs pointing to it became clearer every day.[14]

Gog and Magog (Ezekiel 38:1–39:20) were storming down from the north. The initial letters suggested to some people, said Augustine, who himself rejected such equations, identification with the Getae (Goths) and Massagetae.[15] Ambrose took the Goths to be Gog.[16] The African bishop Quodvultdeus could not make up his mind whether he should identify Magog with the Moors or the Massagetae.[17] Why the Massagetae? There were no Massagetae in the fifth century. But considering that Themistius, Claudian, and later Procopius called the Huns Massagetae,[18] it seems probable that those who identified Magog with the Massagetae thought of the Huns. In the Talmud, where the Goths are Gog,[19] Magog is “the country of the kanths” (Sogdian kanf), that is, the kingdom of the white Huns.[20]

Jerome did not share the chiliastic fears and expectations of his contemporaries. In reshaping Victorinus of Poetovio’s Commentary on the Revelation he substituted for the last part, full of chiliastic ideas, sections from Tyconius.[21] But when in 395 the Huns broke into the eastern provinces, he, too, feared that “the Roman world was falling,”[22] and the end of Rome meant the end of the world.[23] Four years later, still under the impression of the catastrophe, he saw in the Huns the savage peoples kept behind the Caucasus by the iron gates of Alexander.[24] The ferae gentes were Gog and Magog of the Alexander legend. Flavius Josephus (37/8100 a.d.), the first to speak of Alexander’s gates,[25] equated the Scythians and Magog.[26] Jerome, who followed him,[27] identified Herodotus’ Scythians with the Huns,[28] in this oblique way equating the Huns and Magog. Orosius did the same; his “inaccessible mountains” behind which the Huns had been shut off were those where Alexander had built the wall to hold back

Gog and Magog. In the sixth century, Andreas of Caesarea in Cappadocia still held the view that Gog and Magog were those Scythians in the north “called Hunnica by us” aneo xaXovpev Ovvvixa.[29] If even the sober Jerome was inclined, for a time, to see in the Huns the companions of the apocalyptic horsemen, one can easily imagine how the superstitious masses felt.[30]

After 400, the chiliastic fears were somewhat abated.[31] But behind the Huns the devil still was lurking. The curious story in Jordanes[32] about their origin almost certainly is patterned on the Christian legend of the fallen angels:[33] The unclean spirits “bestowed their embraces on the sorceresses and begot this savage race.” The Huns were not a people like other peoples. These fiendish ogres,[34] roaming over the desolate plains beyond the borders of the Christian oecumene, from which they set out time and again to bring death and destruction to the faithful, were the offspring of daemonia immunda. Even after the fall of Attila’s kingdom, the peoples who were believed to have descended from the Huns were in alliance with the devil. They enveloped their enemies in darkness vnd ttvag payelag.[35] The Avars, whom Gregory of Tours called Chuni, “skilled in magic tricks, they made them, that is, the Franks, see illusionary images and defeated them thoroughly” (magicis artibus instructi, diversas fantasias eis, i.e., Francis ostendunt et eos valde superant).[36]

To be sure, this demonization of the Huns alone would not have prevented the Latin historians and ecclesiastic writers from exploring the past of the Huns and describing them as Ammianus did. But the smell of sulphur and the heat of the hellish flames that enveloped the Huns were not conducive to historical research.

Equations

How did the Eastern writers see the Huns? One should expect the Greek historians to have preserved at least some of the ethnographic curiosity of Herodotus and Strabo. But what we have is disappointing.

Instead of facts they serve us with equations. The Latin chroniclers of the fifth century, in calling the Huns by their proper name, were less guided by the intention to be precise than forced to be factual by their ignorance of literature. They knew next to nothing about the Scythians, Cimmerians, and Massagetae, whose names the Greek authors constantly interchanged with that of the Huns. However, even at a time when there still existed a Latin literature worthy of its illustrious past, the Latin writers, both prosiasts and poets, shunned the circumlocutions and equations in which the Greeks indulged. Ausonius rarely missed an opportunity to show how well read he was, yet he refrained from replacing the real names of the barbarians with whom Gratian fought by those he knew from Livy and Ovid.[37] Ambrose, too, avoided the use of archaic or learned words. The Huns, not the Massagetae, attacked the Alans, who threw themselves upon the Goths, not the Scythians.[38] In Ambrose, the former consularis, Roman soberness and aversion to speculation were as much alive as in Ausonius, the rhetor from Bordeaux. A comparison of Pacatus’ panegyric on Theodosius with the orations of Themistius is revealing: The Gaul called the Huns by their name;[39] the Greek called them Massagetae.[40]

As in the West, many writers in the East lacked interest in the invaders. They looked on them as “bandits and deserters,”[41] or they called them Scythians, a name which in the fourth and fifth centuries had long lost its specific meaning. It was widely applied to all northern barbarians, whether they were nomads or peasants, spoke Germanic, Iranian, or any other tongue. Nevertheless, in the vocabulary of the educated the word retained, however attenuated, some of its original significance. The associations it called forth were bound to shape the way in which the barbarians were seen. That makes it at times difficult to decide whom an author means. Are Priscus’ “Royal Scythians” the dominating tribe as in Herodotus, or are they the members of the royal clan, or simply noblemen ?

It is not enough to say that the phrase is merely one of the several instances of Priscus’ literary debt to Herodotus. It certainly is. But it would be strange if the man who used this and other expressions of the great historian would not, here and there, have succumbed to the temptation to see the Huns as the ancients had seen the Scythians.

The Greek historians equated the Huns and the Cimmerians, Scythians, and other peoples of old not just to display their knowledge of the classics or to embellish their accounts,[42] but first of all because they were convinced that there were no peoples which the wise men of the past had not known. And this, in turn, was not so much narrow-minded traditionalism—it was that, too—as, to use a psychological term, a defense mechanism. Synesius of Cyrene (ca. 370—412), in his “Address on Kingship,” explained why there could not be new barbarians:

Now it was not by walling off their own house that the former rulers prevented the barbarians either of Asia or Europe from entering it. Rather by their own acts did they admonish these men to wall off their own by crossing the Euphrates in pursuit of the Parthians, and the Danube in pursuit of the Goths and Massagetae. But now these nations spread terror amongst us, crossing over in their turn, assuming other names, and some of them falsifying by art even their countenances, so that another race new and foreign may appear to have sprung from the soil.[43]

This is carrying the thesis of the identity of the old and new barbarians to absurdity. But it is, after all, what so many Roman generals said so many times on the eve of a battle: our fathers conquered them, we shall conquer them again. The ever recurring oi TtaXai serves the same purpose. It deprives the unknown attacker of his most frightening feature: he is known and, therefore, needs not be feared.

In the equation of the Huns and the peoples of former times both motives, the emotionally conditioned reductio ad notum and the intention .of the learned historian to show his erudition, play their role, whereby the former, I believe, is more often in the service of the latter than is usually assumed. With which of the known peoples an author identified the Huns depended on his information, the circumstances under which he wrote, and the alleged or real similarity between the known and the barely known. The result was invariably the same. All speculations about the origin of the Huns ended in an equation.

Philostorgius, in his Ecclesiastical History written between 425 and 433, “recognized” in them the Neuri.[44] A well-read man, he may have come across a now lost description of the Neuri which reminded him of what he had heard of the Huns. One could think that Philostorgius, less critical than Herodotus, believed the werewolf stories told about the Neuri.[45] Synesius[46] and Jerome[47] were probably not the only ones to compare the Huns with wolves. It was not beyond Philostorgius to identify the “wolfish” Huns with the werewolves of Scythia. But the most likely explanation of his belief is the location of the Neuri: They were the northernmost people, the Huns came from the extreme North—ergo the Huns were the Neuri. To say that they lived along the Rhipaean Mountains, as Philostorgius did, was merely another way of placing them as far north as possible; since the legendary Aristeas[48] the Rhipaean Mountains were regarded as the region of the eternal snow, the home of the icy Boreas.

Procopius’ identification of the Huns with the Cimmerians[49] is neither better nor worse than his assertion that the Goths, Vandals, and Gepids were in former times called Sauromatae.[50] As a rule Procopius, like Themistius and Claudian,[51] equated the Huns and the Massagetae.[52] The later Byzantine writers repeated monotonously the formula: the former x, the present y.

There is finally the historian Eunapius of Sardes (ca. 345—420). The following fragment from him shows (in Vasiliev’s opinion) what a conscientious historian Eunapius was:

Although no one has told anything plainly of whence the Huns came and by which way they invaded the whole of Europe and drove out the Scythian people, at the beginning of my work, after collecting the accounts of ancient writers, I have told the facts as seemed to me reliable; I have considered the accounts from the point of view of their exactness, so that my writing should not depend merely on probable statement and my work should not deviate from the truth. We do not resemble those who from their childhood live in a small and poor house, and late in time, by a stroke of good fortune, acquire vast and magnificent buildings, and none the less by custom love the old things and take care of them.... But we rather resemble those who first using one medicine for the treatment of their body, in the hope of help, and then through their experience finding a better medicine, turn and incline towards the latter, not in order to neutralize the effect of the first one by the second but in order to introduce the truth into erroneous judgment, and, so to speak, to destroy and enfeeble the light of a lamp by a ray of the sun. In like manner we will add the more correct evidence to the aforesaid, considering it possible to keep the former material as an historical point of view, and using and adding the latter material for the establishment of the truth.[53]

All this talk about medicines and buildings, the pompous announcement of what he is going to write on the Huns, is empty. Eunapius’ description of the Huns is preserved in Zosimus.[54] It shows what a windbag the allegedly conscientious historian was. One half of it Eunapius cribbed from Ammianus Marcellinus;[55] the other half, where he “collected the accounts of the ancient writers,” is a preposterous hodgepodge. Eunapius calls the Huns “a people formerly unknown,”[56] only to suggest in the next line their identity with Herodotus’ Royal Scythians. As an alternative he referred to the “snub-nosed and weak people who, as Herodotus says, dwell near the Ister [Danube].” What he had in mind was Herodotus V, 9, 56, but he changed the horses of the Sigynnae, “snubnosed and incapable of carrying men,” into “snub-nosed and weak people” (at/zov; xai ativvarovs d’vdpa; cpEQEiv into xai aaOsvsa^ avOga)-

TtOV?).[57]

Ammianus Marcellinus

Seen against this background of indifference, superstition, and arbitrary equations, Ammianus’ description of the Huns cannot be praised too highly. But it is not eine ganz realistische Sittenschilderung, as Rostovtsev called it.[58] For its proprer evaluation one has to take into account the circumstances under which it was written, Ammianus’ sources of information, and his admiration for the styli veteres.

He most probably finished his work in the winter 392/3,[59] that is, at a time when the danger of a war between the two partes of the empire was steadily mounting. In August 392, the powerful general Arbogast proclaimed Eugenius emperor of the West. For some time Theodosius apparently was undecided what to do; he may have thought it advisable to come to an agreement with the usurper who was “superior in every point of military equipment.”[60] But when he nominated not Eugenius but one of his generals to hold the consulship with him, and on January 23, 393, proclaimed his son Honorius as Augustus, it became clear that he would go to war against Eugenius as he had against Maximus in 388. There can be little doubt that the sympathies of Ammianus, the admirer of Julian, lay from the beginning not with the fanatic Christian Theodosius but with the learned pagan Eugenius.[61] Ammianus must have looked with horror at Theodosius’ army, which was Roman in name only. Although it cannot be proved that the emperor owed his victory over Maximus to his dare-devil Hun cavalry,[62] they certainly played a decisive role in the campaign. Theodosius’ horsemen were “cafried through the air by Pegasi”;[63] they did not ride, they flew.[64] No other troops but the Hun auxiliaries could have covered the sixty miles from Emona to Aquileia in one day.[65] Ammianus had all reasons to fear that in the apparently inevitable war a large contingent of the Eastern army would again consist of Huns. It did.[66]

Ammianus hated all barbarians, even those who distinguished themselves in the service of Rome:[67] He called the Gallic soldiers, who so gallantly fought the Persians at Amida, dentatae bestiae[68] he concluded his work with an encomium for Julius, magister militiae trans Taurum, who, on learning of the Gothic victory at Adrianople, had all Goths in his territory massacied. But the Huns were the worst. Both Claudian[69] and Jordanes[70] echoed Ammianus when they called the Huns “the most infamous offspring of the north,” “fiercer than ferocity itself.” Even the headhunting Alans were “in their manner of life and their habits less savage” than the Huns.[71] Through long intercourse with the Romans, some Germans had acquired a modicum of civilization. But the Huns were still primeval savages.

Besides, Ammianus’ account is colored by the bias of his informants. He went to Rome sometime before 378 where, except for a short while in 383, he spent the rest of his life. The possibility that he met there some Hun or other cannot be entirely ruled out,[72] but it is inconceivable that a Hun who at best understood a few Latin orders could have told Ammianus how his people lived and how they fought the Goths. The account of the war in South Russia and Rumania is based largely on reports which Ammianus received from Goths. Munderich, who had fought against the Huns, later dux limitis per Arabias,[73] may have been one of his informants. One could almost say that Ammianus wrote his account from a Gothic point of view. For example, he described Ermanaric as a most warlike king, dreaded by the neighboring nations because of many and varied deeds of valor;[74] fortiter is a praise which Ammianus did not easily bestow on a barbarian. Alatheus and Saphrax were “experienced leaders known for their courage.”[75] Ammianus names no less than eleven leaders of the Goths,[76] but not one of the Huns. They were a faceless mass, terrible and subhuman.

Ammianus’ description is distorted by hatred and fear. Thompson, who believes almost every word of it, accordingly places the Huns of the later half of the fourth century in the “lower stage of pastoralism.”[77] They lived, he says, in conditions of desperate hardship, moving incessantly from pasture to pasture, utterly absorbed by the day-long task of looking after the herds. Their iron swords must have been obtained by barter or capture, “for nomads do not work metal.” Thompson asserts that even after eighty years of contact with the Romans the productive power of the Huns was so small that they could not make tables, chairs, and couches. “The productive methods available to the Huns were primitive beyond what is now easy to imagine.” To this almost unimaginable primitive economy corresponds an equally primitive social structure, a society without classes, without a hereditary aristocracy; the Huns were amorphous bands of marauders. Even the Soviet scholars, who still hate the Huns as the murderers of their Slavic ancestors, reject the notion that the economy and society were in any way primitive.[78]

Had the Huns been unable to forge their swords and cast their arrowheads, they never could have crossed the Don. The idea that the Hun horsemen fought their way to the walls of Constantinople and to the Marne with bartered and captured swords is absurd. Hun warfare presupposed a far-reaching division of labor in peacetime. Ammianus emphasizes so strongly the absence of any buildings in the country of the Huns that the reader must think they slept the year round under the open sky; only in passing does Ammianus mentions their tents and wagons. Many may have been able to make tents, but only a few could have been cartwrights.

The passage which, more than any other, shows that Ammianus’ description must not be accepted as it stands is the following, often quoted and commented on: Aguntur autem nulla severitate regali; sed tumultuario primatum ductu conlenti, perrumpunt quidquid incident.[79] In Rolfe’s translation, “They are subject to no royal constraint, but they are content with the disorderly government of their important men, and led by them they force their way through every obstacle.” It is not very important that this statement is at variance with Cassiodorus-Jordanes’ account of the war between the Goths and Balamber, king of the Huus, who later married Vadamerca, the granddaughter of the Gothic ruler Vinitharius;[80] whoever Balamber was, Cassiodorus would not have admitted that a Gothic princess could have become the wife of a man who was not some sort of a king. More important is the discrepancy between Ammianus’ statement and what he himself tells about the deeds of the Huns. Altough the cultural level of Ermanaric’s Ostrogoths and the cohesion of his kingdom must not be overrated, its sudden collapse under the onslaught of the Huns would be inexplicable if the latter were nothing but an anarchic mass of howling savages. Thompson calls the Huns mere marauders and plunderers. In a way, he is right. But to plunder on the scale the Huns did was impossible without a military organization, commanders who planned a campaign and coordinated the attacking forces, men who gave orders and men who obeyed them. Altheim defines tumultarius ductus as eine aus dein. Augenblick erwachsene, improvisierte Fuhrung,[81] which renders Ammianus’ words better than Rolfe’s “disorderly government.” However, the warfare of the Huns reveals at no time anything that could be called improvised leadership.[82]

For some time the misunderstanding of the Hunnic offensive tactics— sudden, feigned flight and renewed attack—was, perhaps, inevitable.[83] But Ammianus wrote the last books fourteen years after Adrianople. He must by then have known or, at least, suspected that the early reports on the Huns’ improvised leadership were not true. Yet he stuck to them, for those biped beasts had only “the form of men.”[84] He maintained that their missiles were provided with sharp bone points.[85] He may not have been entirely wrong. But the tanged Hun arrowheads of which we know are all made of iron. Ammianus made the exception the rule.

In describing the Huns, Ammianus used too many phrases from earlier authors. Because the Huns were northern barbarians like the Scythians of old and because the styli veteres wrote so well about the earlier barbarians, Ammianus, the Greek from Antioch, thought it best to paraphrase them. One of the authors he imitated was the historian Trogus Pompeius, a contemporary of the emperor Augustus. Ammianus wrote: “None of them ever ploughs or touches a colter. Without permanent seats, without a home, without fixed laws or rites, thye all roam about, always like fugitives... restless roving over mountains and through woods. They cover themselves with clothes sewed together from the skins of forest rodents.” (Nemo apud eos aval nec stivam aliquando contingit. Omnes sine sedibus fixis, absque lore vet lege aut ritu stabili dispalantur, semper fugientium similes... vagi monies peragrantes el silvas. Indumentis operiuntur ex pellibus silvestrium murum consarcinatis.)[86] This clearly is patterned on Trogus’ description of the Scythians: “They do not till the fields. They have no home, no roof, no abode... used to range through uncultivated solitudes. They use the skins of wild animals and rodents.” (Neque enim agrum exercent. Neque domus Ulis ulla aut tectum aut sedes est... per incultas solitudines errare solitis. Pellibus ferinis ac murinis utuntur.)[87]

It could be objected that such correspondences are not so very remarkable because the way of life of the nomads throughout the Eurasian steppes was, after all, more or less the same. But this cannot be said about other statements of Ammianus which he took from earlier sources. “From their horses,” he wrote, “by day and night every one of that nation buys and sells, eats and drinks, and bowed over the narrow neck of the animal relaxes in a sleep so deep as to be accompanied by many dreams.”[88] His admiration of Trogus here got the better of him. He had read the following description of the Parthians: “All the time they let themselves be carried by their horses. In that way they fight wars, participate in banquets, attend public and private business. On their backs they move, stand still, carry on trade, and converse.” (Equis omni tempore vectantur; Ulis bella, Ulis convivia, Ulis publica et privata officia obeunt; super illos ire, consistere, mercari, colloqui.)[89] Ammianus took Trogus too literally; he rendered “all the time” (omni tempore) by “day and night” (pernox et perdiu) and had, therefore, to keep the Huns on horseback even in their sleep.

Ammianus’ description of the eating habits of the Huns is another example of his tendency to embroider what he read in old books. The Huns, he says, “are so hardy in their form of life that they have no need of fire nor of savory food, but eat the roots of wild plants and the halfraw flesh of any kind of animals whatever, which they put between their thighs and the backs of their horses, and thus warm it a little.”[90] This is a curious mixture of good observation and a traditional topos. That the Huns ate the roots of wild plants is quite credible; many northern barbarians did. Ammianus’ description of the way the Huns warmed raw meat while on horseback has been rejected as a misunderstanding of a widespread nomad custom; the Huns are supposed to have used raw meat for preventing and healing the horses’ wounds caused by the pressure of the saddle.[91] However, at the end of the fourteenth century, the Bavarian soldier, good Hans Schiltberger, who certainly had never heard of Ammianus Marcellinus, reported that the Tatars of the Golden Horde, when they were on a fast journey, “took some meat and cut it into thin slices and put it into a linen cloth and put it under the saddle and rode on it.... When they felt hungry, they took it out and ate it.”[92]

The phrase “Their mode of living is so rough that they eat half-raw meat” (ita uictu sunt asperi, ut semicruda carne uescantuf) is taken from the geographer Pomponius Mela (fl. 40 a.d.), who described the Germans as “Their mode of living is so rough and crude that they even eat raw meat” (uictu ita asperi incultique ut cruda etiam carne uescantur)[93] The Cimbri, too, were said to eat raw meat.[94] Syroyadtsy, a Russian word for the Tatars, possibly means “people who eat raw [meat],” syroedtsy[95] Like so many northern peoples, the Huns may, indeed, have eaten raw meat. Ammianus, however, goes one step further; he maintains that the Huns did not cook their food at all, which is disproved by the big copper cauldrons for cooking meat, one of the leitmotifs of Hunnic civilization. But Ammianus felt he had to force the Huns into the cliche of the lowest of the barbarians.[96]

All this is not meant to dismiss Ammianus’ account as untrustworthy. It contains a wealth of material which is repeatedly confirmed as good and reliable by other literary testimony and by the archaeological evidence. We learn from Ammianus how the Huns looked and how they dressed. He describes their horses, weapons, tactics, and wagons as accurately as any other writer did.

Cassiodorus, Jordanes

In his Hunnophobia, Ammianus was equaled by Cassiodorus (487–583), of whose lost Gothic History much has been preserved in Jordanes’ The Origin and Deeds of the Getae, commonly called Getica. But Cassiodorus had to explain why the Huns could make themselves the lords of his heroes, the Ostrogoths, and rule over them for three generations. His Huns have a wicked greatness. They are greedy and brutal, but they are a courageous people. Attila was a cruel and voluptuous monster, but he did nothing cowardly; he was like a lion.[97] According to Ammianus,[98] the Huns “furrowed the cheeks of children with the iron from their very birth,” words which Cassiodorus copied. But whereas Ammianus continued “in order that the growth of hair, when it appears at the proper time, may be checked by the wrinkled scars,” Cassiodorus wrote “so that before they receive the nourishment of milk they must learn to endure wounds.”[99]

In his account of the early history of the Goths, Jordanes followed Cassiodorus, though not always verbatim. For the proper evaluation of the Gothic tradition about the struggle against the Huns in South Russia, one has to keep in mind that it has come down to us in an expurgated and “civilized” form. In Ostrogothic Italy the memory of the great wars fought side by side with the Huns and against them must still have been alive. Cassiodorus’ sources were songs, cantus maiorum, cantiones, carmina prisca, and stories, some of them told “almost in the way historical events are told” (pene storico ritii). The pene must not be taken seriously. Cassiodorus wrote his Gothic History “to restore to the Amal line the splendor that truly belonged to it.” He wrote for an educated Roman public whose taste would have taken offense at the crude, cruel, and bloody aspects of early Germanic poetry. A comparison of the Getica with Paul the Deacon’s History of the the Langobards shows to what extent Cassiodorus purged the tradition of his Gothic lords all of barbaric features.

But this is not all. The Origo gentis Langobardorum, written about 670, one of Paul’s sources, is full of pagan lore. More than two hundred years after the conversion of the Danes to Christianity, the old gods, scantily disguised as ancient kings, still were wandering through the pages of Saxo Grammaticus. In the 530’s when Cassiodorus wrote his history, there still were alive men whose fathers, if not they themselves in their youth, had sacrificed to the old gods. The Gothic “Heldenlieder” were certainly as pagan as those of the Danes and Langobards. The original breaks through in a single passage in the Getica, taken over from Cassiodorus: “And because of the great victories the Goths had won in this region, they thereafter called their leaders, by whose good fortune they seemed to have conquered, not mere men but demigods, that is, ansis.”[100] Even here Cassiodorus euhemerized the tradition. Everywhere else the pagan elements are radically discarded. The genealogy of the Amalungs, which in the carmina and fabulae was almost certainly full of gods, goddesses, murder, and homicide, reads like a legal document.

Where, as in the account of the war between the Ostrogoths and the Huns, Cassiodorus-Jordanes and Ammianus differ, Ammianus’ version is, without the slightest doubt, the correct one. We cannot even be sure that Cassiodorus’ quotations from Priscus are always exact. However, because so much of our information on the Huns is based on these quotations, they have to be taken as they are. Occasionally (as, for instance, in the story of Attila and the sacred sword, or in the description of Attila’s palace) Cassiodorus renders the Priscus text better than the excerpts which the scribes made for Constantine Porphyrogenitus in the tenth century. And for this alone we must be grateful to the stammering, confused, and barely literate Jordanes. But to elevate him to the ranks of the great historians, as some years ago Giunta tried, is a hopeless undertaking.[101]

II. History

From the Don to the Danube

The first chapters of Ammianus Marcellinus’ last book contain the only extant coherent account of the events in South Russia before 376. From his Gothic informants Ammianus learned that the Huns “made their violent way amid the rapine and slaughter of the neighboring peoples as far as the Halani.”[102] Who those peoples were obviously no one could tell him, and the monumenta vetera supplied no information about them; they were among those “obscure peoples whose names and customs are unknown.”[103] Ammianus’ actual information begins with the Hun attack on the Alans: The Huns overran “the territories of those Halani (bordering on the Greuthungi [Ostrogoths]) to whom usage has given the surname Tanaitae [Don people].”

This passage has been variously interpreted.[104] How far to the east and west did the “Don people” live? In one passage Ammianus locates all Alans—and that would include the Tanaitae—“in the measureless wastes of Scythia to the east of the river,”[105] only to say a few lines later that the Alans are divided between the two parts of the earth, Europe and Asia,[106] which are separated by the Don.[107] The Greuthungi-Ostrogoths[108] were the western neighbors of the Tanaitae, but in another passage Ammianus puts the Sauromatae, not the Greuthungi, between the Don and the Danube,[109] and in still another one (following Ptolemy, Geography V, 9, 1) also east of the Don.[110]

Ammianus suffered from a sort of literary atavism, garbling the new reports with the old.[111] The chapter on the Alans in book XXXI includes a lengthy dissertation on the peoples whom the Alans “by repeated victories incorporated under their own national name.”[112] Ammianus promises to straighten out the confused opinions of the geographers and to present the truth. Actually, he offers the queerest hodgepodge of quotations from Herodotus, Pliny, and Mela,[113] naming the Geloni, Agathyrsi, Melanchlaeni, Anthropophagi, Amazons, and Seres, as if all these peoples were still living in his time.

The Huns clashed with Alanic tribes in the Don area. This is all we can retain from Ammianus’ account. If Ammianus had used the term Tanailae as Ptolemy used it,[114] the “Don people” would have lived in European Sarmatia. But a river never formed a frontier between seminomadic herdsmen, and certainly not the “quietly flowing” Don. The archaeological evidence is unequivocal: In the fourth century Sarmatians grazed their flocks both east of the Don as far as the Volga and beyond it, and west of the river to the plains of Rumania. Exactly where the Huns attacked cannot be determined; like the later invaders, their main force probably operated on the lower course of the river.

Ammianus’ account of an alliance between a group, or groups, of Alans and the Huns cannot be doubted. In the 370’s and 380’s Huns and Alans are so often named together, that some kind of cooperation of the two peoples would have to be assumed even without Ammianus’ explicit statement: