Paul Kingsnorth

The Heads of the Hydra

The globalisation of resistance is a new phenomenon. Only in the last few years have campaigners around the world joined up to resist the globalisation of the economy. Yet for decades before that, people all over the world were opposing environmental, social and economic destruction destruction which, though not always obvious, was often the result of globalisation.

Though most of the world’s politicians, industrialists and ‘opinion-formers’ don’t seem to have noticed yet, what is likely to be the key struggle of the early 21st century has already begun. In time, the 1990s may come to be seen as the defining decade in the formation of this struggle the time when the first stirrings of co-ordinated, worldwide resistance to the global economy began.

But it is only relatively recently, perhaps only in the last five or ten years, that activists around the world have begun to put their local struggles — against environmental damage, social decay, the destruction of local economies and cultures, the exploitation of labour and so forth — into a global context. Only in the 1990s has resistance, like capital itself, begun to become truly globalised.

But while this globalisation of resistance — characterised by struggles such as last year’s anti-MAI campaign, and the forthcoming June 18th events — is a recent phenomenon, people around the world have long been campaigning against destructive projects which, though it may not always have been obvious, were themselves linked to globalisation. Road schemes, new power plants, giant dams, deforestation, privatisation, expropriation of land — these are among the many individual threads in the global economic web. Campaigners against them have been, in effect, trying to slice off some of the many heads of the Hydra; it is only now that they are beginning to join together to aim their swords at its heart.

The Infrastructure of the Global Economy

As we have already seen, a global economy needs a global infrastructure to support it. It needs roads, railways, ports and airports to move increasing volumes of goods across borders. It needs power stations, dams, mines and pylons to provide fuel for the cities in which most consumers live, and the warehouses and offices of corporations. It needs quarries, landfill sites, factories, industrial estates, oil rigs, vast areas of chemical cropland and all the other components of a truly global economy. And as the market increases, as the number of consumers expands, it needs more of these things all the time.

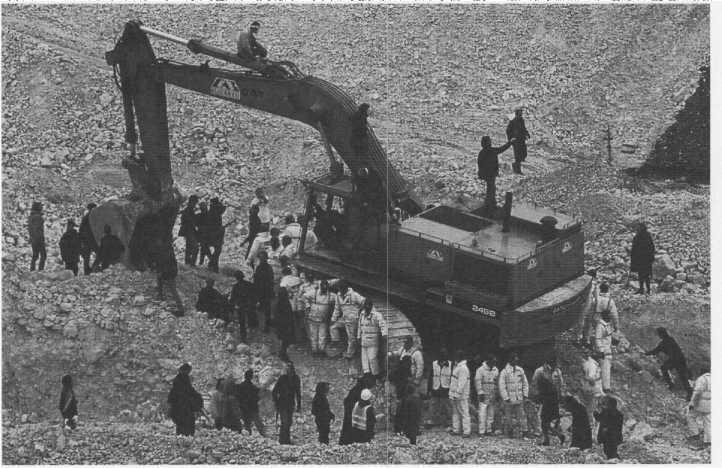

But their construction and expansion invariably leads to environmental destruction and social dislocation, and protests against infrastructure development have been some of the most significant and popular of recent years. The 1990s saw the birth of a massive road protest movement in Europe, where the expansion of the ‘Trans-European Road Network’ (TERN) has led to massive environmental damage. The most widespread and successful European anti-roads movement was in Britain, where hundreds of treehouses, tunnels and protest camps succeeded in derailing the government’s £22 billion road construction programme in just five years. Destructive roads have also been fought against in the ‘Third World’ — the Trans-Amazonian highway in Brazil, and other large schemes in Venezuela, Indonesia and elsewhere have been blockaded by thousands of indigenous people, protesting against the destruction of their forests and their traditional lands.

Extractive industries, particularly mining and oil-drilling, have also been foci of resistance. The world’s longest-running campaign against a single corporation the campaign against RTZ mining, led by ‘PaRTiZans’, has united indigenous people and environmental campaigners against the massive forest destruction, dislocation and pollution caused by mining and quarrying in Australia, Indonesia, South America and across Europe. Anti-Shell campaigns have sprung up across the world, and that corporation’s dubious alliance with the military regime in Nigeria, and the destruction of the lands of the Ogoni and jaw peoples, has been linked with the attempt by oil companies to expand drilling into Antarctica, the only continent left mostly untouched by industrial destruction. And in Venezuela, as you read this, thousands of Indians are blockading roads in the Imataca forest reserve, to try to prevent the construction of an electrical grid that will help power the gold mines destroying their forests.

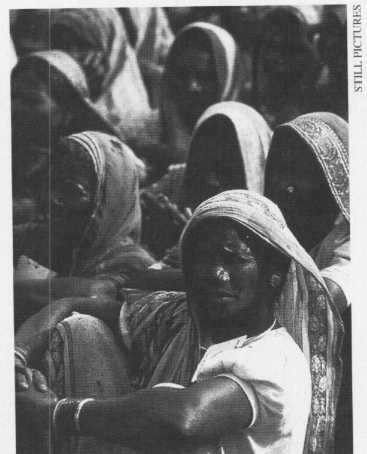

The construction of large dams in the Third World, often funded by the World Bank or Western governments, has combined environmental damage with the dislocation of thousands of people, and anti-dam battles have been some of the most bitterly fought in the world. India’s Narmada dam alone was set to force over 30,000 villagers from their homes, and thousands of local people, often led by groups of women villagers, have staged sit-ins, festivals and protests against the government’s plans for years.

The Battle for the Land

Linked with the expansion of the economic infrastructure is the issue of ownership and control of the land itself. From the deforestation of the Amazon to the construction of dams in India, from the transmigration programme in Indonesia to the expansion of industrial farming in Europe, land is increasingly being expropriated for large-scale projects that power the onward movement of the global market. Some of the fiercest battles across the Third World in recent decades have been over the issue of land ownership. The Amazon rubbertappers’ battles against deforestation and the expansion of plantations; the Maori independence movement in New Zealand and the aboriginal rights campaigns in Australia; the Kalahari bush-people and the Masai of Africa, fighting to retain their land rights in the face of mass tourism; tribal peoples in Borneo and West Papua, resisting the Indonesian government’s transmigration schemes — all these, and many more such movements are focussed on securing land rights for local and traditional peoples.

Throughout the 1990s, awareness of land rights issues has grown across the world. and even in ‘developed’ countries, movements like the UK’s ‘The Land Is Ours’ are working to persuade people that control of, and access to, land is a key component of any alternative economic system. In Brazil, what Noam Chomsky has called “the world’s most important social movement” — the Movimento Sem Terra (MST) — has been responsible for occupying vast tracts of unused land, and resettling over 140,000 dispossessed peasant families on small-scale, co-operative farming communities since the beginning of the 1990s. They organise nationwide campaigns of direct action against industrial farming, labour casualisation and dispossession, and have a growing base of support amongst Brazil’s vast underclass of landless people. The Economist magazine, the parish newsletter for followers of the Church of Global Capitalism, has said that, aside from currency fluctuations, the MST is the only force with the power to derail Brazil’s globalisation train.

The Deepening of Environmental Activism

The growing environmental destruction perpetrated in the name of globalisation has produced a rise in direct action aimed at protecting what remains of wilderness areas and important habitats. The emergence of ‘Earth First!’ and the more radical ‘Earth Liberation Front’ (ELF) firstly in the USA and then in Europe, was a response to the invasion of wilderness areas by loggers, miners, roadbuilders and industry in general, and the direct-action tactics they pioneered were soon taken up in protests against environmental destruction all over the world. Today, direct action to protect wilderness and countryside areas for their own sake — rather than for their potential usefulness to humanity — has become commonplace in many countries. Often linked closely with issues of land rights and dispossession, environmental direct action campaigns have been seen in Canada’s temperate rainforests (where the successful campaign to protect Clayoquot Sound has served as a model for many others), in Colombian Indian villages, on logging roads in Sarawak, on proposed port sites in India and in woodlands threatened by golf courses or holiday villages in Europe. There have been, and will be, many more of them.

Social and Labour Movements

Globalisation is also responsible for eroding legal protection for workers, destroying small businesses and leaving millions unemployed. Any nation or corporation that tries, today, to maintain decent employee protection regulations or environmental standards is likely to be driven out of business by those competitors who have fewer scruples about using child labour or spewing their toxic by-products into the nearest river. This ‘race-to-the-bottom’ is one of the key features of the opening-up of markets, and its consequences are leading to a resurgence in labour and social movements.

Across Europe and North America, in the last few years, there have been widespread demonstrations by farmers, postal workers, dockers, miners, truckers, train drivers and many others, all protesting about casualisation, unemployment and growing job insecurity. And elsewhere, alliances of labour and social movements have achieved remarkable results.

In Indonesia last year, for example, an alliance of students, workers, farmers and others succeeded in bringing down the dictator Suharto after thirty years of rule. The ‘Peasant Movement of the Philippines’ has organised marches, rallies and a national caravan to protest against the opening-up of the country’s forests, fields and villages to foreign mining and logging companies, and the country’s ‘New Peoples’ Army’ is continuing its armed struggle against globalisation, and the unemployment and homelessness it brings with it. And in India, campaigns against ‘biopiracy’ by Western scientists, and against Monsanto and other producers of GM crops, are inspired by the need to protect India’s peasant farmers from being steamrollered by the global economy.

This brief summary of some of the better-known campaigns against the effects of globalisation gives some idea of how far-reaching resistance already is. As awareness of the globalisation project and its effects becomes more widespread, it is likely that more and more of these diverse movements will begin to unite and turn their fire on their mutual enemy — the global market.