Perspectives on Terrorism; Volume IX, Issue 6

A Journal of the Terrorism Research Initiative

Radical Groups’ Social Pressure Towards Defectors: The Case of Right-Wing Extremist Groups

Future Behaviour towards Group

Group Reaction Differentiation According to Defector Type

How Groups Arrive at a Strategy

Discussion of Findings and Future Directions for Research

Group Decision Making Processes

Annex: Brief Case Descriptions

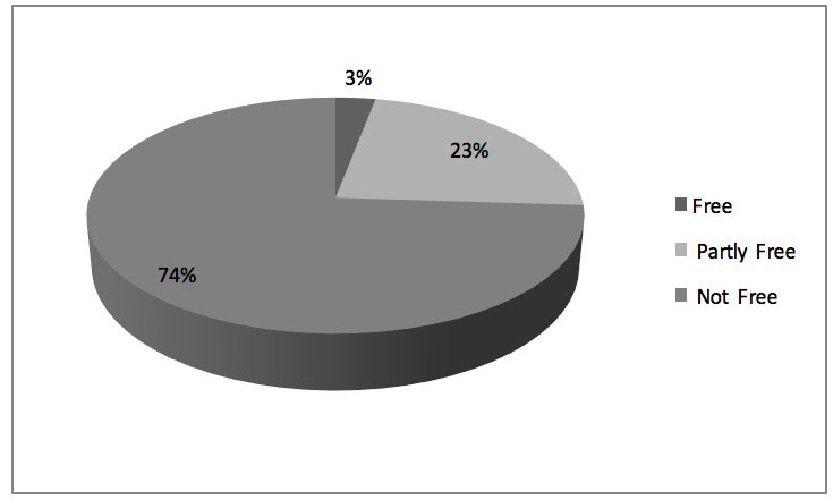

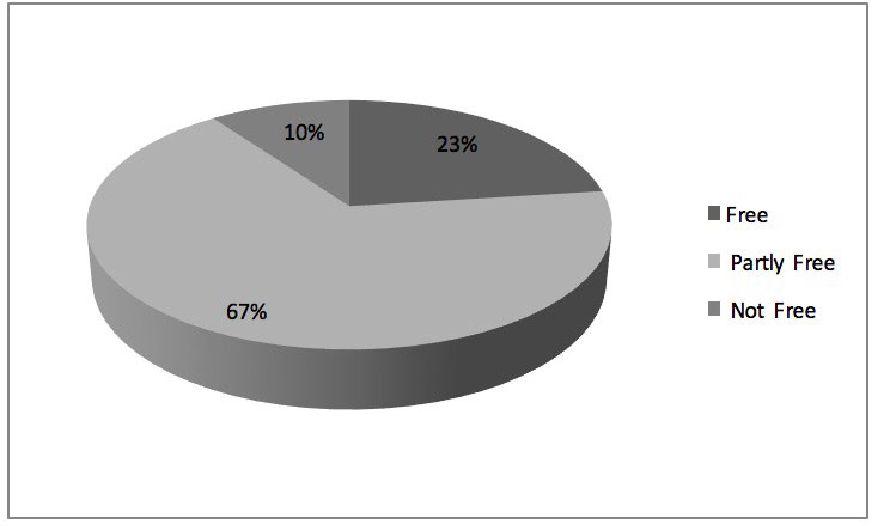

Religion, Democracy and Terrorism

The Democracy-Terrorism Debate

Religion and Variations in Terrorist Targeting

Religious Security and Terrorism

20 Years Later: A Look Back at the Unabomber Manifesto

Attracting, Maintaining, and Molding Followers

Securing Adoption of the Ideology by the Larger Structure

Reacting to Resistance from the Larger Structure

“Rhetorical Problems” and “Rhetorical Strategies”

Appendix: Sections of Theodore Kaczynski’s “Industrial Society and its Future”

Re-Examining the Involvement of Converts in Islamist Terrorism: A Comparison of the U.S. and U.K.

Appendix 1. List of American converts included in the sample

Appendix 2. List of British converts included in the sample

Terrorist Practices: Sketching a New Research Agenda

Unsolved Puzzles and Questionable Assumptions

Social Practice and Terrorist Society

Leveraging Practice Disaggregation: The Case of Religious Culture

Research and Policy Implications

Interview Protocols and Sample Description (n = 13)

Motivations and the Positive Benefits for Those Joining IS

Process of Indoctrination by Charismatic Trainers

Military Training, Weapons, & Battle Field Practices

Warnings to those Westerners Who Might be Attracted to IS

Bibliography: Homegrown Terrorism and Radicalisation

Bibliographies and other Resources

Journal Articles and Book Chapters

Counterterrorism Bookshelf: 40 Books on Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism-Related Subjects

A Word of Appreciation for Our External Peer Reviewers

TRI Award for Best PhD Thesis 2015: Call for Submissions

TRI National/Regional TRI Networks (Partial) Inventory of Ph.D. Theses in the Making

Expected date of completion: December 2016.

Job Announcement: Open Rank Faculty Search at CTSS, UMass Lowell

[Front Matter]

Table of Contents

Welcome from the Editor

I. Articles

The Evolution of Al Qaeda’s Global Network and Al Qaeda Core’s Position Within it: A Network Analysis

by Victoria Barber

Radical Groups’ Social Pressure Towards Defectors: The Case of Right-Wing Extremist Groups

by Daniel Koehler

Religion, Democracy and Terrorism

by Nilay Saiya

20 Years Later: A Look Back at the Unabomber Manifesto

by Brett A. Barnett

II. Research Notes

Re-Examining the Involvement of Converts in Islamist Terrorism: A Comparison of the U.S. and U.K

by Sam Mullins

Terrorist Practices: Sketching a New Research Agenda

by Joel Day

Eyewitness Accounts from Recent Defectors from Islamic State: Why They Joined, What They Saw, Why They Quit

by Anne Speckhard and Ahmet S. Yayla

III. Resources

Bibliography: Homegrown Terrorism and Radicalisation

Compiled and selected by Judith Tinnes

IV. Book Reviews

Counterterrorism Bookshelf: 40 Books on Terrorism & Counter-Terrorism-Related Subjects

Reviewed by Joshua Sinai

<strong>V. Notes from the Editor

A Word of Appreciation for Our External Peer Reviewers

from the Editorial Team

TRI Award for Best PhD Thesis 2015: Call for Submissions

TRI National/Regional TRI Networks (Partial) Inventory of Ph.D. Theses in the Making

by Alex P. Schmid (Network Coordinator)

Job Announcement: Open Rank Faculty Search at CTSS, UMass Lowell

About <em>Perspectives on Terrorism

Welcome from the Editor

Dear Reader,

We are pleased to announce the release of Volume IX, Issue 6 (December 2015) of Perspectives on Terrorism at www.terrorismanalysts.com. Our free online journal is a joint publication of the Terrorism Research Initiative (TRI), headquartered in Vienna (Austria), and the Center for Terrorism and Security Studies (CTSS), headquartered at the Lowell Campus of the University of Massachusetts (United States).

Now completing its ninth year, Perspectives on Terrorism has over 5,800 regular subscribers and many more occasional readers and visitors worldwide. The Articles of its six annual issues are fully peer-reviewed by external referees while its Research Notes, Policy Notes and other content are subject to internal editorial review.

This issue begins with analysis by Victoria Barber on the relationship between al Qaeda core and other identifiable groups within the so-called “global jihadist movement.” She finds that many groups’ ideological affinity seems to give way to more worldly concerns, and globalization to regional concerns, indicating limited evidence of a truly cohesive global network. Then Dan Koehler looks at how right-wing extremist groups react - emotionally and strategically - when individuals defect from the group. In the next article, Nilay Saiya describes how states that provide religious security for their citizens undercut the ideological narratives disseminated by religious militants (that their faith is under attack), and thus dampening the resonance of their appeal for violent action. Finally, Brett Barnett examines how and why the manifesto of “Unabomber” Theodore Kaczynski has resonated with some radical environmentalists.

Our Research Notes section begins with a piece by Sam Mullins examining how religious converts compare with non-converts in the U.S. and U.K. with regard to involvement in terrorist activities 1980-2013. Next, Joel Day proposes an innovative mixed methods approach to the study of terrorist cultural, ritual and community practices. And in the final piece of this section, Anne Speckhard and Ahmet Yayla provide some preliminary results of their Islamic State Interviews Project, based here on a sample of thirteen Syrian IS defectors who spoke about life inside the “Islamic State” and now warn others not to join what they gradually came to see as a totally disappointing, ruthless and un-Islamic organization.

The Resources section features an extensive bibliography by Judith Tinnes on homegrown terrorism and radicalization, and 40 short book reviews by Joshua Sinai. And the issue concludes with a sincere word of thanks to our external peer reviewers; an announcement for the annual TRI Award for Best Thesis; an inventory of Ph.D. theses underway by members of the TRI National/Regional Networks; and a faculty job announcement from the CTSS at UMass Lowell.

This issue of the journal was prepared by the co-editor of Perspectives on Terrorism, Prof. James Forest at the University of Massachusetts Lowell, who offers a special thank you to our new Editorial Assistant Jared Mello and to CTSS Co-Op Scholar Danielle Thibodeau for their considerable assistance. The next issue (February 2016) will be prepared in the European offices of the Terrorism Research Initiative (TRI) by Prof. em. Alex P. Schmid.

I. Articles

The Evolution of Al Qaeda’s Global Network and Al Qaeda Core’s Position Within it: A Network Analysis

by Victoria Barber

Abstract

There has been much discussion in recent decades regarding the nature of the threat posed by terrorism. In doing so, many have cited the existence of a vast and amorphous global terrorist network, with Al Qaeda at the helm. But is that model a truly accurate one? By using social network analysis to map and track Al Qaeda’s global network from 1996 to 2013, this article seeks to determine whether the global movement is as cohesive and ideologically-driven as it has been made out to be. Ultimately, it finds that not only is that model no longer reflective of Al Qaeda’s global network, it likely never was. In the end, ideological affinity seems to give way to more worldly concerns, and globalization to regional concerns, leaving the idea of a global movement lacking.

Keywords: Al-Qaeda; networks; influence

Introduction

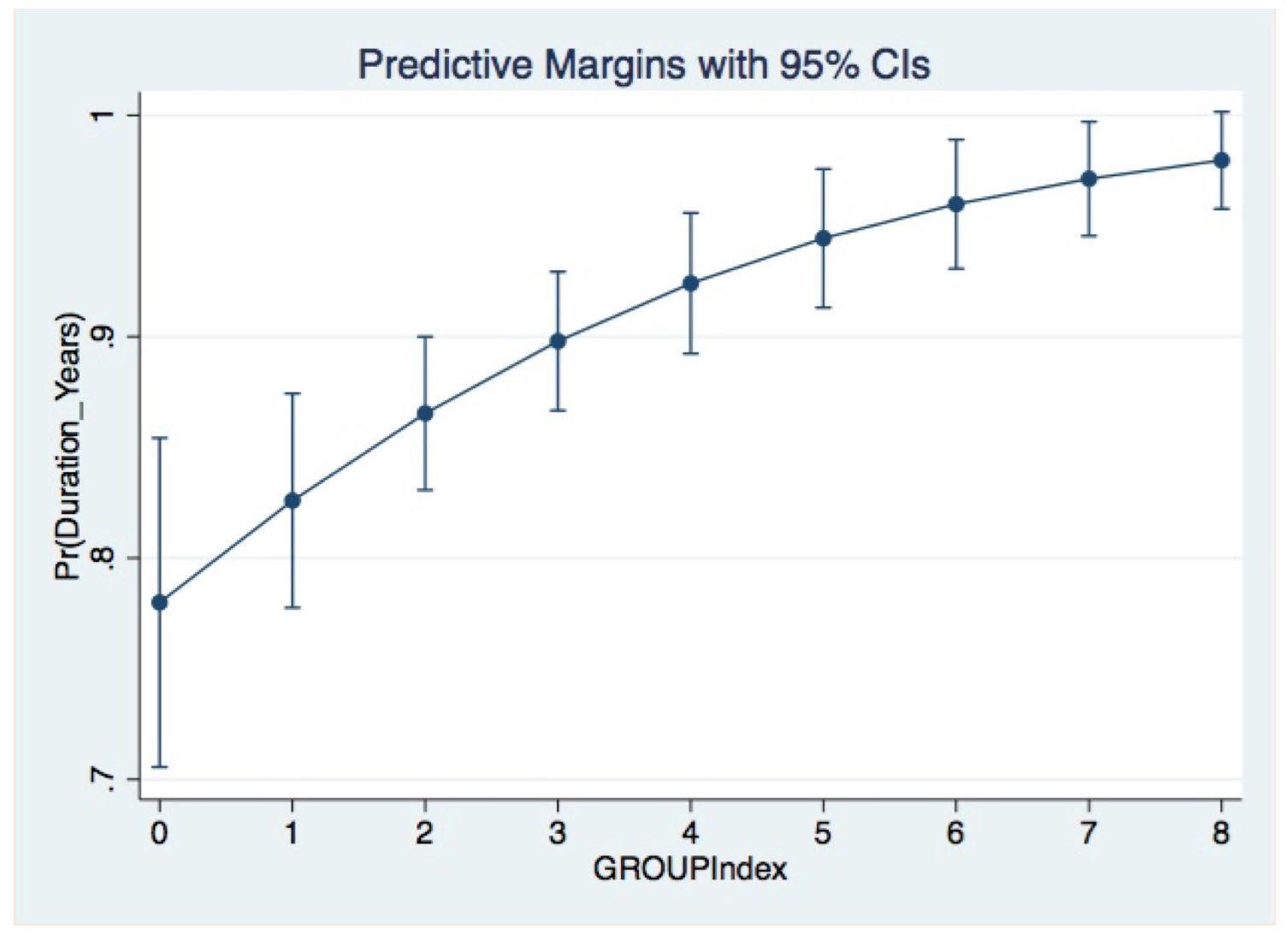

There has been much debate in recent years over the nature of the threat posed by terrorism in the 21st century. A prominent question within this debate concerns how the terrorist threat is structured: Is it within traditional groups and their affiliates or individuals taking their own initiative, rendering the traditional group structure irrelevant?[1] The impact of this answer will dictate strategies for intervention. For example, should the threat lie in individual self-motivated actors, the often-used strategy of decapitation is of limited use. While there are certainly arguments to be made for the threat posed by the rise of lone wolves[2] and their origins in more familiar movements within the counter-terrorism field,[3] this article will focus on established groups, as its primary concern is in relationships between them.

Such relationships have changed in recent decades, as advances in technology and more affordable travel have made communication and coordination much easier.[4] This has given rise to transnational terrorist movements and allowed these established groups to move beyond the national and regional struggles they had engaged in before.[5] As part of this transition, many groups moved from the traditional hierarchical organization observed in non-state armed groups in the past and toward a more horizontal structure,[6] leading researchers to study terrorist organizations as networks.[7] There is much debate over the relative merits of these organizational structures. On the one hand, size can be a limiting factor for a networked structure, as large networks can be difficult to control and coordinate.[8] However, becoming networked can make a group more resilient to intervention and can therefore be an attractive choice for clandestine organizations.[9]

The rise of Al Qaeda provides an excellent example of this transition and the globalization of the terrorist threat.[10] Arguably the group with the greatest reach and influence in the last several decades, Al Qaeda Core began as a small and highly selective group that arose out of the Soviet-Afghan War.[11] They maintained this status throughout the 1990s, quietly influencing uprisings throughout the Middle East and biding their time until they entered the world stage with the September 11th attacks.[12] By September 12th, 2001, Al Qaeda and Osama bin Laden were household names, and Al Qaeda Core was in the position to foster other militant groups on a much broader scale. It was seen as the hallmark of a new kind of terrorist threat, one that was no longer confined to a specific conflict or geographic area and could pose a legitimate threat to even the most powerful states.[13]

The most common contemporary image of Al Qaeda is that of a global movement with Al Qaeda Core as the vanguard for a network of affiliated groups that could be utilized within the movement, but did not require the same maintenance and control as a hierarchical organization.[14] This affiliation could be anything from sending members to Al Qaeda affiliated training camps or publishing statements in support of Al Qaeda to formally pledging one’s group to Al Qaeda Core. What emerged was a structure that could loosely be described as a set of concentric circles, with Al Qaeda Core at the center, immediately surrounded by the lucky few groups that were allowed to call themselves its regional branches, followed by affiliate groups who benefitted from Al Qaeda in some way, and finally the independent cells or individuals, who were inspired by Al Qaeda, but lacked any tangible connection to the Core.[15]

There is much debate over the nature and genesis of this structure.[16] Some scholars argue that the networked approach was adopted consciously, with key members of the organization advocating for the early versions of the structure even before 9/11.[17] Others argue that much effort was placed on maintaining a strict hierarchy within the group, which made it less able to combat more networked organizations, such as ISIS.[18] On this side of the debate, the structure emerged in response to counter-terrorism efforts, rather than as a conscious choice by the leadership.[19]

Regardless of where one falls in these discussions, Al Qaeda as an organization evolved into being part of a larger network that spanned the globe, though whether it maintains a position as a member or leader of that network remains to be seen. But is the idea of a sustained global terrorist network an accurate one or is that image overblown or out-of-date? The remainder of this article will attempt to address this concern by looking at what makes groups cooperate and where Al Qaeda Core lies within the network.

There are many schools of thought surrounding the best way to measure the strength of a network, be it density of connections, leadership roles, or number and independence of sub-groups.[20] However, while these could certainly be useful when evaluating an organization as a whole, this research approaches the idea of the network in a slightly different way. Rather than looking at Al Qaeda Core’s network in terms of strength and weakness, the purpose of this research is to determine whether this image of a sustained, cohesive global movement with Al Qaeda Core at the center was an accurate one.[21] To answer this question, Al Qaeda Core’s leadership role within the network and whether those actors with which it cooperates are in line with its ideology serve as key variables. As an ideologically based organization, it follows that working with groups that have similar objectives would denote the maintenance of its image and that of a global movement. As with any coalition, agreement on objectives is central to the maintenance of a multi-actor campaign. As such, within the context of this research, Al Qaeda Core’s global network is considered “strong” when it maintains a clear leadership role and engages largely with actors that are in line with its objectives.

The discussion that follows will track trends in cooperation and competition in Al Qaeda’s global network as it grows and Al Qaeda Core’s place within it to determine the validity of this global network model. Ultimately, the argument is made that we can use these variables to determine whether the image of a cohesive global network is an accurate one.

Methodology

The primary analytical approach used within this article is network analysis. A networked dataset was created largely from the data supplied by the Mapping Militants Project (MMP),[22] run by Professor Martha Crenshaw of Stanford University, and the Global Terrorism Database (GTD).[23] To create the dataset, this project began with the list of groups and the links between them that were included within the Al Qaeda Global Network portion of the MMP. From there, all of the incidents that involved two or more groups were pulled from the GTD, provided that at least one group was in the original list from the MMP. The research was restricted to these two sources in an effort to contain the scope of this project. This restriction does give rise to some limitations in the research, which are elaborated upon in more detail later in this article. However, future research could expand the source material in order to further test the conclusions found here.

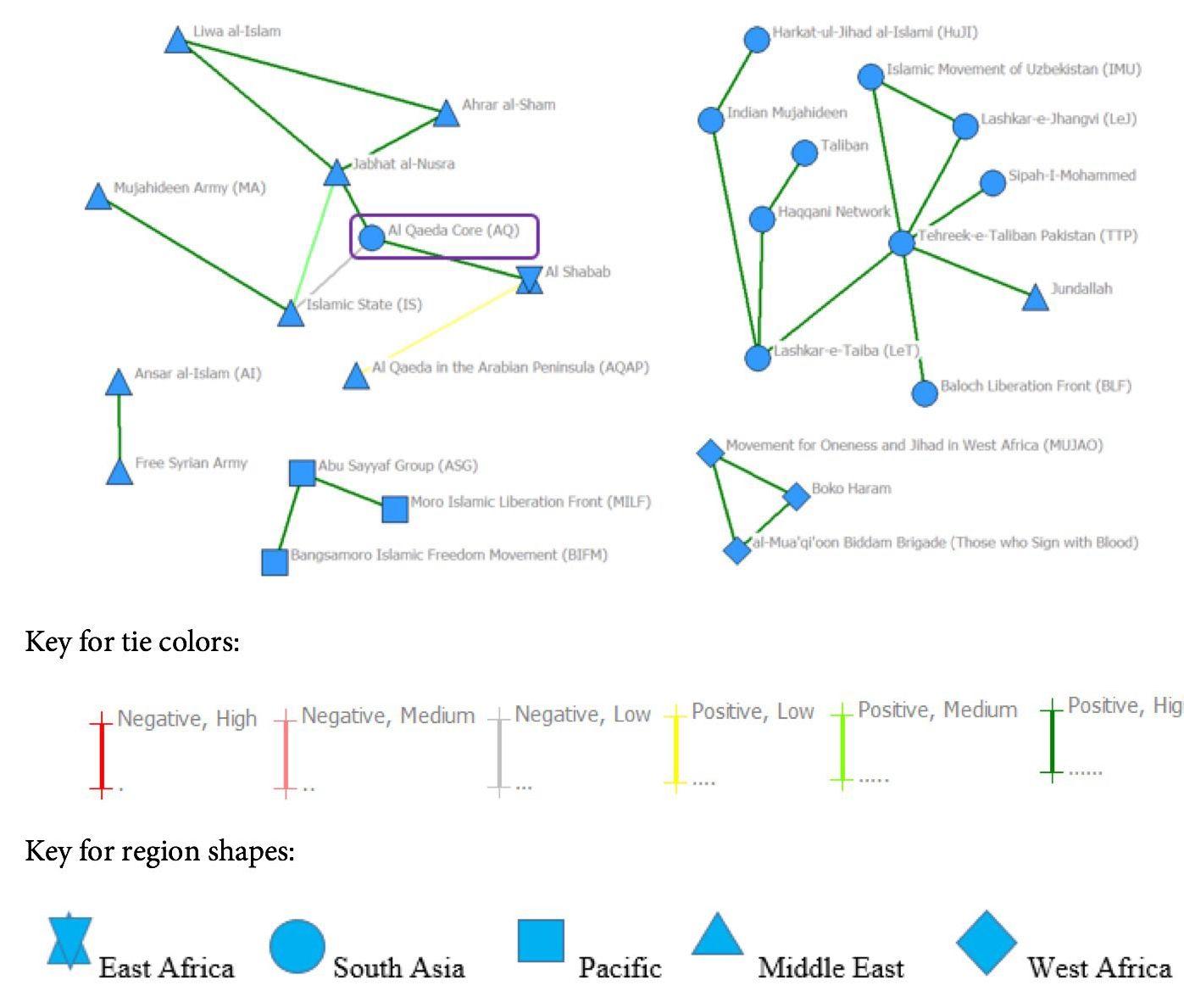

This methodology was chosen to highlight the connections between these groups and the character of those connections. In the interest of showing the development of relations over time, the analysis was broken into four time periods, each of which spans roughly five years. In the diagrams and analyses that follow, a tie between two groups represents one or more incidents that involved those two groups during that time period. In the instances where there were multiple incidents involving two groups that occurred in the same time period, those incidents were aggregated according to an averaging method that will be elaborated upon in the sections that follow.

Ultimately, this methodology allows the researcher to track the evolution and devolution of relationships between groups within the larger Al Qaeda network, as ties are not cumulative between time periods. As ties appear between groups, it indicates that there were incidents involving those two groups within the time block in question. As they disappear between time periods, the lack of tie indicates that there was not an additional incident within the more recent time block present in either the MMP or GTD datasets. In doing so, this analysis reveals changes in cooperative behavior between groups within the network, as well as patterns within the network as a whole.

Groups

In this analysis, all groups that were included within MMP or the subset of the GTD previously mentioned were considered, regardless of their status as terrorist organizations, level of affiliation with Al Qaeda Core, etc. An assortment of demographic information was collected on each one in an effort to determine whether there was a pattern or change in the nature of groups admitted into the Al Qaeda network over time. These included: country of origin/primary activity, level of Al Qaeda affiliation, primary target(s), organizational objective(s), umbrella organization(s), and a series of yes/no features that are described in more detail below. Ultimately, a total of 56 organizations were considered, all of which are listed below in alphabetical order.[24]

-

313 Brigade

-

Abu Sayyaf Group (ASG)

-

Adan Abyan Islamic Army (AAIA)

-

Ahlu-sunah Wal-jamea (Somalia)

-

Ahrar al-Sham

-

Al Jama’a Al-Islamiya

-

Al Qaeda Core (AQ)

-

Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula (AQAP)

-

Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb (AQIM)

-

Al Qaeda in Yemen (AQY)

-

Al Shabab

-

Al Mua’qi’oon Biddam Brigade (Those who Sign with Blood)

-

Al Qaeda Kurdish Battalions

-

Al Tawhid Islamic Front (TIF)

-

Ansar al-Islam (AI)

-

Asif Raza Commandos

-

Baloch Liberation Front (BLF)

-

Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Movement (BIFM)

-

Black Banner Brigade

-

Boko Haram

-

Egyptian Islamic Jihad

-

Free Aceh Movement (GAM)

-

Free Syrian Army

-

Hamas (Islamic Resistance Movement)

-

Haqqani Network

-

Harkat-ul-Jihad al-Islami (HuJI)

-

Harkat-ul-Mujahedeen

-

Hizb-I-Islami

-

Hizbul al Islam (Somalia)

-

Hizbul Mujahideen (HM)

-

Indian Mujahideen

-

Islamic Army in Iraq

-

Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan (IMU)

-

Islamic State (IS)

-

Jabhat al-Nusra

-

Jaish-e-Mohammad (JeM)

-

Jamaat-E-Islami (India/Pakistan)

-

Jamiat ul-Mujahedin (JuM)

-

Jemaah Islamiyah (JI)

-

Jundallah

-

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (LeJ)

-

Lashkar-e-Jhangvi Al-Alami

-

Lashkar-e-Taiba (LeT)

-

Lashkar-e-Zil

-

Liwa al-Islam

-

Moro Islamic Liberation Front (MILF)

-

Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group (GICM)

-

Movement for Oneness and Jihad in West Africa (MUJAO)

-

Mujahideen Army (MA)

-

Mutassim Bellah Brigade

-

Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF)

-

Rajah Solaiman Revolutionary Movement

-

Second Soran Unit (SSU)

-

Sipah-I-Mohammed

-

Taliban

-

Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (TTP)

The following analysis focuses mainly on whether or not a group’s organizational objectives are in line with the stated objectives of the Core, its country of origin/primary activity, and the level of affiliation each group has with Al Qaeda Core. Further discussion of the data collection methods for those three features can be found below, though it is worth noting that the variables collected on the groups were treated as static. In other words, attribute data were not collected separately for each time period. A full explanation of the data that were collected but not addressed in this paper can be found in Appendix I.

Organizational Objective(s)

For coding purposes, each of the publicized organizational objectives, as specified in the MMP dataset and supplemental source material, were recorded without any limitation on the number of objectives ascribed to each group. The list of organizational objectives used in coding are as follows; few of the groups had only one of them, while many have expressed a combination of any number of these as primary objectives:

-

Government Overthrow[25]

-

Establish Islamic Government

-

Wahhabi

-

Anti-Shia

-

Anti-Western

-

Incorporation of Kashmir into Pakistan

-

Nationalist

In the analysis, the primary focus was on whether or not groups aligned with the publicized organizational objectives of Al Qaeda Core—namely a combination of Anti-Shia, Anti-Western, and Establishing an Islamic Government objectives.[26] As such, any organization with at least two of Al Qaeda Core’s organizational objectives was treated as being ideologically aligned with Al Qaeda Core’s goals. For the purposes of this analysis, a new binary variable was created to denote whether a group matched the above description or not.

Region

In an effort to determine whether geography was a factor in the admission of groups into the network, the countries in which organizations originated—or, in the cases in which the leadership was forced to relocate, primarily operate—were recorded. For the sake of more efficient analysis, the countries were divided into regions, which were then used as the primary geographical identifiers for groups. The list of such countries, divided by region, is as follows.

-

South Asia

-

Afghanistan

-

India

-

Pakistan

-

Pacific

-

Indonesia

-

Malaysia

-

Philippines

-

Singapore

-

Middle East

-

Iran

-

Iraq

-

Iraq (Kurdistan)

-

Israel

-

Palestine

-

Saudi Arabia

-

Syria

-

Turkey

-

Yemen

Northern Africa

-

Algeria

-

Egypt

-

Morocco

East Africa

-

Ethiopia

-

Somalia

West Africa

-

Mali

Nigeria

Level of Al Qaeda Affiliation

The first four levels of Al Qaeda affiliation were drawn from Hoffman and Reinares’s definitions of the four types of affiliation with Al Qaeda Core.[27] There was, however, a need for two more categories within the dataset, in addition to a category for groups with no apparent relationship with Al Qaeda Core. The first, Anti-AQI (Al Qaeda in Iraq), though limited to groups in Iraq, did not easily fit into any of the four categories. These groups generally work against AQI, now the Islamic State (IS), though have occasionally worked with it. In both instances, their interactions with the group earned them places within the network and, by extension, an additional category. The second addition, “Many members were veterans of the Soviet- Afghan War”, describes groups that have no obvious Al Qaeda affiliation, other than the fact that their members served in the Soviet Afghan war with the original Al Qaeda Core members. They could potentially be categorized within the fourth category, Independent Cell (Inspired by AQ), but the fact that the fourth category specifies that Al Qaeda provided inspiration to the groups or individuals within it make that argument problematic, as many of them were founded before or contemporaneously with Al Qaeda Core. As such, they were given their own category of affiliation. Those groups with no apparent relationship with Al Qaeda Core were coded as “no affiliation”. The full list of levels of affiliation is outlined below.

-

AQ Central / Core

-

AQ-Directed Branch / Territorial Extension

-

Autonomous Affiliate

-

Independent Cell (Inspired by AQ)

-

Anti-AQI (though occasional ally)

-

Many members were veterans of the Soviet-Afghan War

-

No affiliation

Links

To achieve a more nuanced view of the network, the links between the groups were also coded. The two features of particular concern, other than which groups were involved in each incident and when it happened, were the type of link and where that type fell on a scale of what level of commitment that action represented on the part of the groups involved. More detail on both of those features is provided in the sections below.

Type of Link

The type of link denotes the nature of the relationship between the two groups for that data point. Each link describes an incident in which two groups were involved. As such, the links between the groups describe a wide variety of actions that one group can take with or against another. All links described within the MMP dataset were included in this analysis, regardless of the relationship’s nature, relative importance, or ultimate outcome. Likewise, the only requirements for GTD incidents to be included in this analysis were that at least one of the groups from the MMP was involved, and collaborative action was at least suspected. In other words, if the incident was recorded within the GTD as having two groups involved because it was listed as potentially being committed by either one organization or the other, rather than it being the product of joint effort, it was excluded from this study. The 20 types of links between groups identified within the dataset are listed below:

-

Documented Alliance

-

Joint Operation

-

Training

-

Host Leader

-

Material Aid

-

Shared Leader (i.e. the leader of one organization belonged to the other at some point)

-

Establishes Contact

-

Parent-Child Organizations

-

Public Statement of Support

-

Oath of Allegiance

-

Merger

-

Humanitarian Aid

-

Split

-

Personal Friendship Between Leaders

-

Documented Rivalry

-

Sanctuary (i.e. one group provided sanctuary to a number of members of the other during a time of persecution)

-

Public Statement of Condemnation

-

Armed Conflict

-

Rejected Merger

-

Training/Financial Aid

Link Level

To aid in analysis, the types of link were further categorized into six groups, based on two main criteria: positive or negative (which describes whether the link between the two organizations was cooperative or competitive, respectively), and high, medium, or low (which denoted the strength of the connection). The distinction between positive and negative links is fairly straightforward, but the demarcation between high, medium, and low level links is more subjective and, therefore, warrants further description.

The category “Low” was limited to those links that were either primarily based on public statements or individual relationships. These are considered low-level links because they involve relatively less effort on the part of the group (or even individual) or involve taking one group “out of the game” (e.g. hiding members of another group during a time of persecution).

Medium-level links describe either relationships documented from an outside source (e.g. a government report describing two groups as allies) or the provision of some sort of aid without one group taking the extra step of performing a joint operation with the other. Again, this is a higher level of commitment than the low- level category in that there are additional steps taken (e.g. providing funds to support another group, rather than simply praising them in public), but this relationship falls short of physically acting together.

Finally, high-level links are reserved for events that either change or establish organizational structures (e.g. merging organizations, pledging allegiance, or splitting) or involve the groups actively working with or against each other. These links denote the highest level of commitment, as they involve either the fundamental structures of the groups or placing “boots on the ground” for an operation or conflict. As such, they were awarded the highest weight.

A detailed breakdown of where each type of link was placed within this framework can be found in Table 1:

Table 1: Types of Links Between Organizations

| Low | Medium | High | |

| Positive |

Public Statement Hosting Leader Shared Leader Establishing Contact Personal Friendships Sanctuary |

Documented Alliance Training/Financial Aid Humanitarian Aid Material Aid |

Oath of Allegiance Merger Parent-Child Organizations Joint Operation |

| Negative | Public Statement | Documented Rivalry |

Armed Conflict Split Rejected Merger |

Analysis

In an effort to examine the changes within the network before and after the 9/11 attacks, the analysis here is limited to the period between 1996 and 2013, when the MMP dataset ends. Moreover, the data is separated into four intervals of time in order to both show the progression in the network over time and have enough data in each interval of time to be meaningful.

Within the discussion of each interval, there is a network map to illustrate the structure of the network and the types of links found between the groups that were active within that time period. Also included is a series of network measures to assess Al Qaeda’s role within the network and trends in the groups with which it chooses to interact.

The two measures this research focuses on are centrality and cohesion. Centrality denotes the role of an individual actor within the network. There are several measures to determine centrality, each with its own implications. For these purposes, three have been selected: betweenness, eigenvector, and closeness. For comparison, each interval discussion includes the top three groups for each measure. Before discussing these measures in the context of this research, it is worth defining each in order to ensure clarity in their implications.

Betweenness denotes the number of paths between groups. Actors with high betweenness scores are couriers of information. They connect groups to each other and can act as both bottlenecks and facilitators.[28] Within the context of this research, one would expect Al Qaeda Core to have a high betweenness score for each time interval, if it is truly the “mastermind” of the network.

Eigenvector centrality measures the level of connection to other well-connected nodes. Those with high eigenvector scores are informal leaders, who have influence over more overt power players.[29] As with betweenness, one would expect Al Qaeda Core to have a very high score for eigenvector centrality, meaning that it is pulling the strings behind the regional clusters of groups.

Closeness determines how many steps are required for each group to reach every other group within the network. Groups with low closeness scores have fewer steps to get to the others in the network. Within the context of this research, this is the number of other groups one actor would have to work through to reach every other actor. Again, one would expect Al Qaeda Core to have a low closeness score in each time block. This implies that AQC has relatively few steps to go through to get to each of its affiliates, as compared to the rest of the network, which would have to go through AQC to reach another affiliate.

To assess the cohesion of the network, or how often groups tend to work with other groups that are similar to them in some respect, this analysis uses an E-I Index. This measure reports on a scale of -1.00 to 1.00 how often a group (or all groups within the network as a whole) interacts with another group with whom it shares a given characteristic. A score of -1.00 denotes that a group only works with groups that are like it and 1.00 describes an actor that only works with groups that are unlike it. A characteristic used within this analysis is region of primary activity. If the E-I Index is taken for a group based in the region of primary activity for actors within the network, then the score a group receives describes how likely that group is to work with other groups from its region. If an actor scores a -1.00, that means that it interacts entirely with other actors from the same region.

For the purposes of this analysis, an E-I Index for both Al Qaeda Core and the network as a whole are included, with the “in-group” defined in four different ways:

1. Those who are considered in line with Al Qaeda Core’s objectives, as defined in the Methodology section of this article

2. Those that originate from or primarily operate in a given region

3. Those who fall into the category of being Al Qaeda Core, a Regional Branch, or an Autonomous Affiliate (i.e. have an established and tangible relationship with Al Qaeda Core)

4. Those who are either Al Qaeda Core or a Regional Branch.

These categories were chosen to examine whether Al Qaeda Core is more likely to interact with groups that are ideologically or organizationally similar to it, as demonstrated by similar objectives or an established relationship, respectively.

Combined, these measures speak to the strength of Al Qaeda Core’s position within the network. With high centrality measures, AQC is in a position of power within the network, with that power defined by both controlling the flow of information and affiliation (with Betweenness and Closeness) and maintaining connections to other well-connected actors (with Eigenvector centrality). Cohesion speaks to the idea that Al Qaeda Core is maintaining control over its message and goals within the network by maintaining ties to groups that are ideologically similar to itself.

One important note in the centrality and cohesion measures is that, unlike network maps, only positive links were included. In other words, the cohesion score represents how likely Al Qaeda Core is to work together with another group, not how likely the two groups are to simply interact. This was done to prevent the negative ties from skewing the measures toward actors that often clash with others, as this research is chiefly concerned with Al Qaeda’s positive control over its network.

The following sections include an analysis of Al Qaeda Core’s network at four time intervals, including a network map, centrality measures to determine Al Qaeda’s position within that network, and cohesion measures to quantify the features of groups that make Al Qaeda Core more or less likely to work with them.

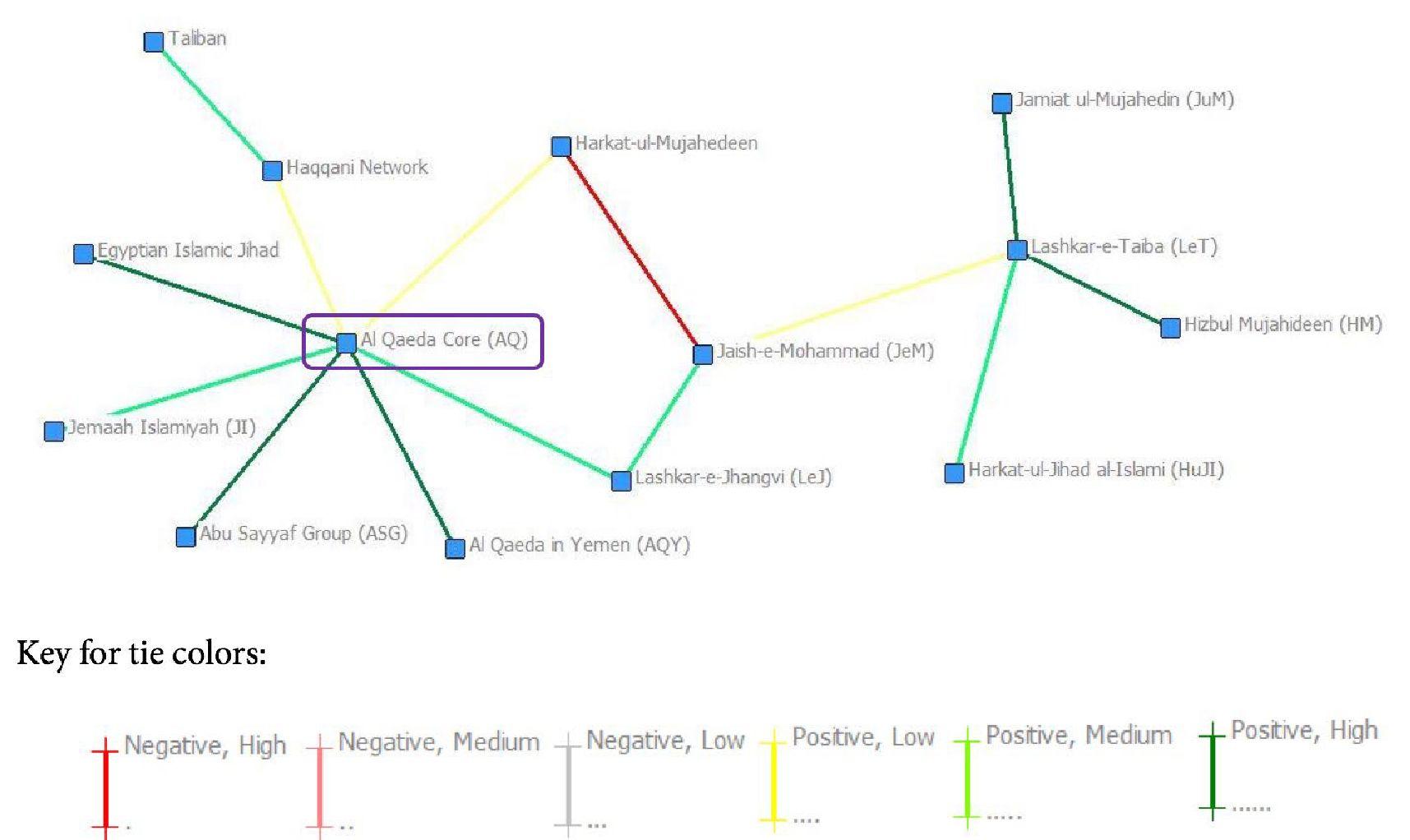

1996-2000

This block represents the period leading up to the September 11th attacks. This was when the network was in its infancy, as Al Qaeda Core was planning the attack under the watchful eye of Khalid Sheikh Mohammed. It was also during this period that the networked structure and “homegrown” jihad movement were developed. [30] At this point, Al Qaeda Core certainly had ties to other groups, as evidenced below. However, the familiar concentric circle model has yet to take shape. In Figure 1 below, the colors represent the average commitment level between those groups during this time period, a method that will carry forward for every subsequent diagram within this paper. To obtain this average, each link level was given a weight (i.e. Negative, High = 1, Negative, Medium = 2, up to Positive, High = 6) and an average level was taken based on the number of links between the groups.

In the map above, the network has a hub-and-spoke structure, with Al Qaeda Core at the center, not unlike the star network proposed by Arquilla, which requires information and planning to flow through the hub. [31] This is especially interesting to observe, given the previously mentioned debates surrounding when and why Al Qaeda adopted a networked approach to its activities. Regardless of whether it was done intentionally before counter-terrorism measures put pressure on the organization after 2001, it does appear that Al Qaeda Core had been developing a network among its associates before that time. Al Qaeda Core tends to enjoy strong positive links (i.e. Positive High and Medium), while the rest of the network is defined by weaker positive and even negative links. In short, Al Qaeda is securely positioned at the center of a network that is defined by its relationships.

It is worth noting that much care was taken to code each tie independently of external factors to maintain both the integrity of the dataset and the ability to observe the network as it evolved. For example, a reader who is familiar with the case may view the positive-low link weight between Al Qaeda Core and the Haqqani Network as reductive of the relationship between the two groups. However, in the interest of consistency,

every instance of one group hosting the leadership of another, or providing safe-haven for that group, is coded as a low-positive tie, regardless of the long-term implications of that tie. Additional relations that, admittedly, likely grew out of the affiliation cemented during this period will be coded and analyzed separately in subsequent sections as they arise.

Centrality

Unsurprisingly, Al Qaeda is a strong frontrunner in all three measures of centrality, as shown in Table 2, below. To reiterate, a high betweenness measure indicates that Al Qaeda Core is the path through which information and planning flows. Having the highest eigenvector measure indicates that Al Qaeda Core is the most strongly connected to other well-connected groups. Finally, having the lowest closeness score means that Al Qaeda Core can connect with other groups within the network by going through the lowest number of other groups, (i.e. has the least degree of separation from other actors). In combination, leading each of these categories denotes that Al Qaeda Core has a firm grasp on the network.

Table 2: Analysis of Data on Centrality, 1996-2000

| First | Second | Third | |

| Betweenness | Al Qaeda Core (62.000) | Laskar-e-Jhangvi (40.000) | Jaish-e-Mohammad (36.000) |

| Eigenvector | Al Qaeda Core (0.453) | Laskar-e-Jhangvi (0.380) | Haqqani Network (0.362) |

| Closeness | Al Qaeda Core (26.000) | Laskar-e-Jhangvi (28.000) | Jaish-e-Mohammad (32.000) |

Not only does it control the flow of information between the groups with its high betweenness measure, but it also enjoys a position that is both well connected to other well-connected groups, such as they are in a network like this, and requires very few steps to reach any other group. This implies that there is little that gets done involving multiple actors within network without Al Qaeda Core’s involvement.

Cohesion

Once again, cohesion measures indicate a group’s likelihood to work with another that shares some characteristic with it. This analysis also included cohesion measures along each parameter for a variety of datasets, including two different ways to consolidate multiple ties within a time interval and subsequently eliminate negative ties.

Thus far, this analysis has focused on the average commitment level between groups for a given time interval. However, to thoroughly test the aggregation methods, cohesion measures were also taken using the highest level of commitment between two groups, rather than the average. For example, if two groups had two ties, one with a strength of 1 and the other with a strength of 4, they would average to 2.5, which would be excluded from the average-based analysis, as it would round to a level 3 tie, which corresponds to a Negative Low score. However, in running the measures for the highest tie between groups, this relationship would be included, as the highest commitment level between them is 4, a Positive Low score.

In addition, not only were cohesion measures run for all positive ties, but they were also run for only the highest levels of commitment. In other words, cohesion measures were determined both for a network of all positive ties between groups (i.e. low, medium, and high), and for only the Positive High ties.

As a result, the EI index was taken for each interval in four different ways:

1. Taking the average commitment level between two groups and eliminating all negative ties (i.e. Weights of 1-3 are eliminated, leaving only positive commitment levels)

2. Taking the highest commitment level between two groups and eliminating all negative ties (i.e. Weights of 1-3 are eliminated, leaving only positive commitment levels)

3. Taking the average commitment level between two groups and eliminating all but the Positive High (6) commitment (i.e. Weights of 1-5 are eliminated, leaving only Positive High commitment levels)

4. Taking the highest commitment level between two groups and eliminating all but the Positive High (6) commitment (i.e. Weights of 1-5 are eliminated, leaving only Positive High commitment levels)

This was done in order to determine whether the choice of analyzing only positive average commitment levels obscured other results, which may have come to light in using another method of consolidating the data. However, the results for all methodologies were comparable, and therefore all cohesion measures within the body of this article will be average positive ties going forward. A table of all cohesion results can be found in Appendix II.

The cohesion measures for our four key characteristics for the average positive commitment level between 1996 and 2000 are displayed in Table 3 below. Once again, the EI Index used for this analysis is on a -1.00 to 1.00 scale, with groups scoring a -1.00 interacting exclusively with those who are the same as they are. In other words, if a group should score a -1.00 for the “Same Region” category, it means that said group interacts exclusively with other groups from its region.

Table 3: Analysis of Data on Cohesion, 1996-2000

| Similar Objectives | Same Region | Core/Regional Branch/ Independent Affiliate | Core/Regional Branch Only | |

| Al Qaeda Core | 0.231 | 0.231 | -0.692 | 0.692 |

| Whole Network | -0.405 | -0.568 | -0.189 | -0.405 |

Interestingly enough, even in these early stages, Al Qaeda Core is slightly more likely to interact with groups that are not in line with their objectives. There is a stronger tendency within the network for groups that are in-line with AQC’s objectives to work with each other and those who are not to work together. However, the tendency is not very strong, implying that links are not necessarily ideologically motivated. One possible explanation is that ideologically dissimilar groups are brought into the network in an effort to indoctrinate them. However, it is impossible to prove that thesis definitively within the context of this project.

There is also a slight tendency for Al Qaeda Core to work with groups that are not focused within its region, which is expected given its global agenda. There is also a moderate tendency for groups to work with others within their region, which is, again, expected as the global network is still developing.

There is a fairly strong tendency for AQC to work primarily with those with whom it has an established relationship, at least when affiliates are included. However, that tendency reverses when affiliates are not included in the “in-group”, which is to be expected given the timing, as many of the regional branches had yet to take shape within the network.

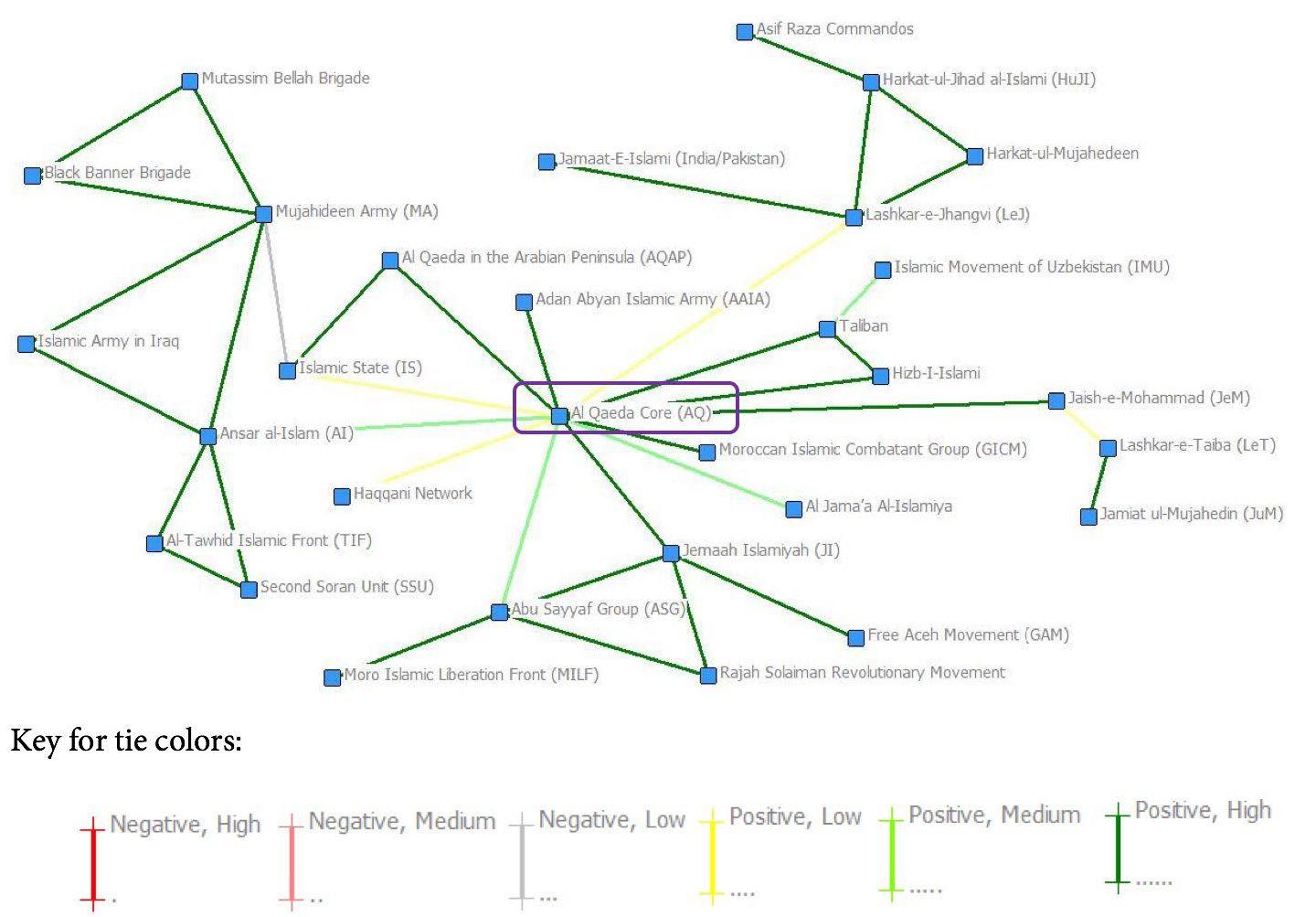

2001-2005

The period including and following the September 11th attacks was one of expansion in the network.

Suddenly, groups were clamoring to be affiliated with the Al Qaeda brand,[32] which is reflected in Figure 2 below.

Once again, one can see a hub-and-spoke structure with Al Qaeda Core at the center and roughly the same breakdown of the level of direct ties between AQC and others.[33] However, there is a significant development that was not present in the previous time period. In the 2001-2005 period, we begin to see not only affiliate groups connecting with each other on a large scale, but strong positive links between those groups. In particular, the network begins to display small groups of two or three that are typically connected to Al Qaeda Core through one member of the cohort, for example the cohort of Second Soran Unit (SSU) Al Tawhid Islamic Front (TIF) and Ansar al Islam (AI), who are connected to the Core through AI. This development is significant in that it denotes the decentralization of power within the network. Al Qaeda Core still enjoys its place as the hub, connecting a vast array of spokes, but other hubs are beginning to emerge among the groups in its network.

Centrality

Once again, there is little surprise in the centrality measures, as displayed in Table 3 below. Al Qaeda Core maintains its place at the top of every centrality measure, with Ansar al-Islam often staking out second place. Despite the expansion of the network and the increasing connections between affiliates, AQC is still the main source of direction and information within the network.

Table 4: Analysis of Data on Centrality, 2001-2005

| First | Second | Third | |

| Betweenness | Al Qaeda Core (349.000) | Ansar al-Islam (107.000) | Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (103.000) |

| Eigenvector | Al Qaeda Core (0.616) | Abu Sayyaf Group and Jemaah Islamiyah (0.254) | Ansar al-Islam (0.253) |

| Closeness | Al Qaeda Core (49.000) | Ansar al-Islam (65.000) | Lashkar-e-Jhangvi and the Islamic State (69.000) |

Cohesion

The EI Index for the four characteristics of interest during the 2001-2005 time interval are displayed in Table 5. The results are very similar to those of the previous interval, with most of the patterns established remaining largely unchanged.

Table 5: Analysis of Data on Cohesion, 2001-2005

| Similar Objectives | Same Region | Core/Regional Branch/ Independent Affiliate | Core/Regional Branch Only | |

| Al Qaeda Core | 0.231 | 0.231 | -0.692 | 0.692 |

| Whole Network | -0.368 | -0.579 | -0.158 | -0.368 |

The paradoxically inclusive nature of Al Qaeda Core continues into this period, as there is a slight tendency for AQC to interact with groups that are not in line with their objectives, as compared to the slight tendency of the rest of the network to stay within their “in-group”, with regards to AQC’s ideology, though that effect appears to be weakening compared to the previous time period. Moreover, while AQC’s tendency to seek out groups outside of its region has continued, the regional focus of the network has only increased.

Likewise, there is still a strong tendency for Al Qaeda Core to interact with those groups, with which they have an established connection. However, the tendency reverses when independent affiliates are removed from the “in-group”, implying that Al Qaeda Core is largely limiting its activities to its independent affiliates, as many of the regional branches are still forming.

In short, Al Qaeda Core remains the main hub of activity in a growing network. It is the key connection between smaller networks of groups that share similar ideology and regional focus, without pigeon-holing itself by excluding connections based on ideology or region. While this inclusion may or may not have been a strategic decision, it reveals that even in the early stages, the Global Al Qaeda network does not meet the characterization of strength in a global movement as provided within this research.

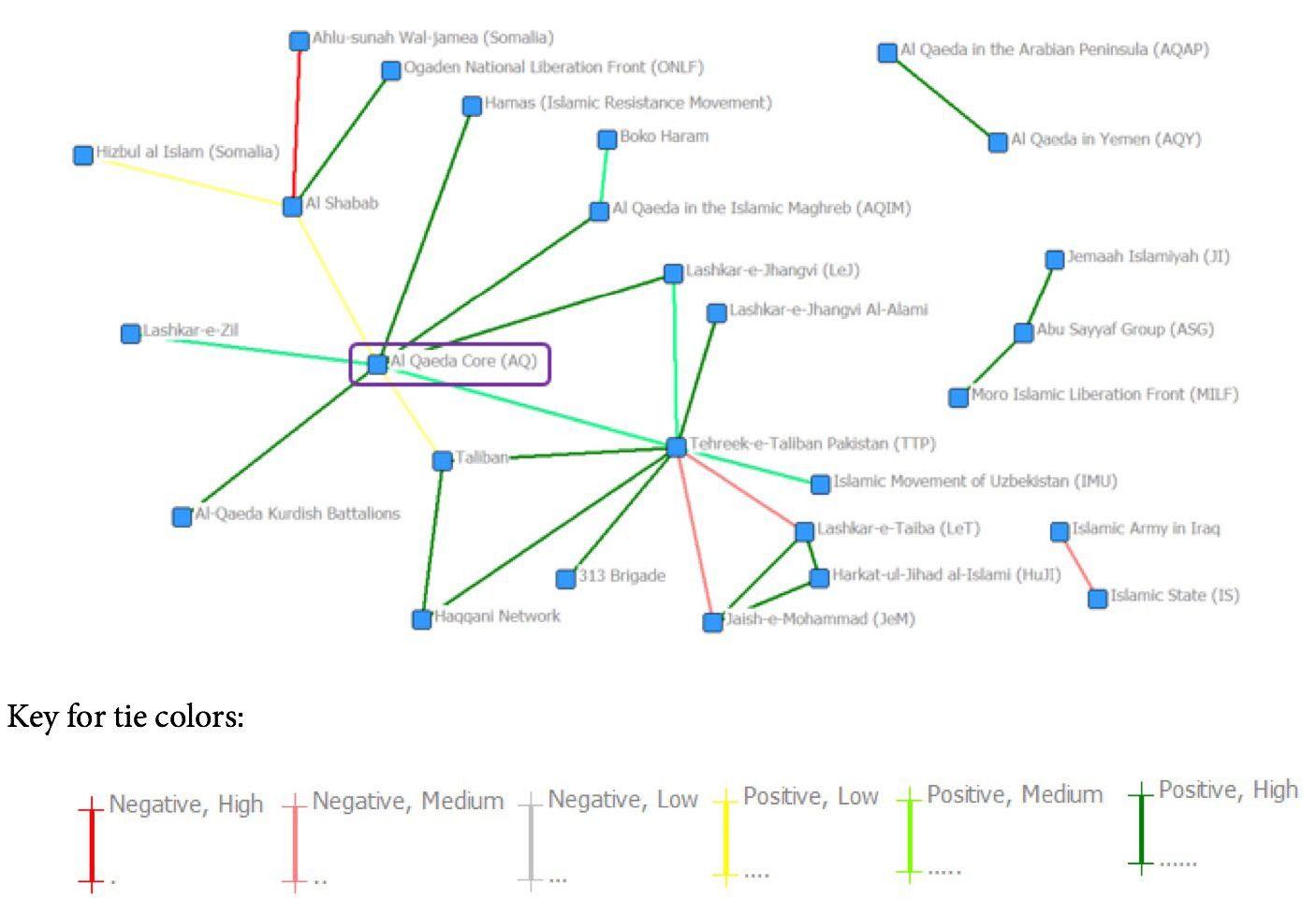

2006-2010

The 2006-2010 time block shows a flurry of activity within the network. Not only have several new actors emerged, but the structure of the network has changed dramatically, as displayed in Figure 3.

Once again, the number and breakdown of ties directly to Al Qaeda Core remained relatively constant. However, the ties between affiliates with little interaction with AQC has increased exponentially, with both a high proportion of strong positive ties and the highest number of negative ties that have appeared thus far.

Most significantly, while there is still a hub and spoke structure surrounding Al Qaeda Core, it no longer has the monopoly on that structure. Figure 3 reveals the development of Al Shabab and Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan as hubs in their own rights. This is where one may begin to believe that the network may have overextended itself. For more empirical data to that effect, this analysis will turn to centrality and cohesion measures.

Centrality

While Al Qaeda Core managed to hold onto the top centrality scores, maintaining its position as a broker of information, TTP is hot on its heels, as shown in Table 6.

Table 6: Analysis of Data on Centrality, 2006-2010

| First | Second | Third | |

| Betweenness | Al Qaeda Core (80.500) | Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (45.000) | Al Shabab (27.000) |

| Eigenvector | Al Qaeda Core (0.535) | Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (0.509) | Taliban (0.355) |

| Closeness | Al Qaeda Core (214.000) | Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (218.000) | Taliban (222.000) |

In previous time intervals, there was rarely such consistency in the second and third positions in each measure. A group may have one or two of the second-place spots. However, having a “clean sweep” of second place and such little variety in third implies the solidification of other centers of power that are well- positioned to challenge that of Al Qaeda Core.

Cohesion

In Al Qaeda Core we can observe near perfect external cohesion, perfect internal cohesion, and perfect indifference, as evidenced in Table 7. Within the 2006-2010 time period, Al Qaeda almost exclusively interacted with groups that were not in line with its organizational objectives, but with whom it had an established relationship. However, it appeared that autonomous affiliates were still the preferred groups. It also appeared to lose its preference for groups that were not part of its region, as it displays no preference either way.

Table 7: Analysis of Data on Cohesion, 2006-2010

| Similar Objectives | Same Region | Core/Regional Branch/ Independent Affiliate | Core/Regional Branch Only | |

| Al Qaeda Core | 0.75 | 0 | -1 | 0.25 |

| Whole Network | -0.403 | -0.583 | -0.667 | -0.417 |

This implies that the ideology of the groups with which it interacted did not matter, so long as they were a known ally. Moreover, it demonstrates the disconnect between the objectives of the affiliates and branches AQC chose to foster in this period of expansion and the ideology of Al Qaeda Core itself. Although AQC has displayed a pattern of being slightly biased toward bringing in groups that have different ideologies, there has previously been a stronger base of those groups that are in line with its objectives to balance it out. In this latest time period, it would seem that as the network has expanded, Al Qaeda Core has lost some measure of control of its message via its affiliates.

Interestingly enough, groups in the rest of the network have displayed a moderate to strong preference for those of with the same features that they do. In other words, groups with objectives in line with Al Qaeda tend to work with each other, as do groups that operate within the same region, or have the same or similar levels of affiliation with Al Qaeda. This implies that even as Al Qaeda’s control over the network begins to wane, its influence on the groups within it has remained. Still, while it has maintained one aspect of strength, as defined within this context,[34] it seems to have abandoned the pursuit of the other.[35]

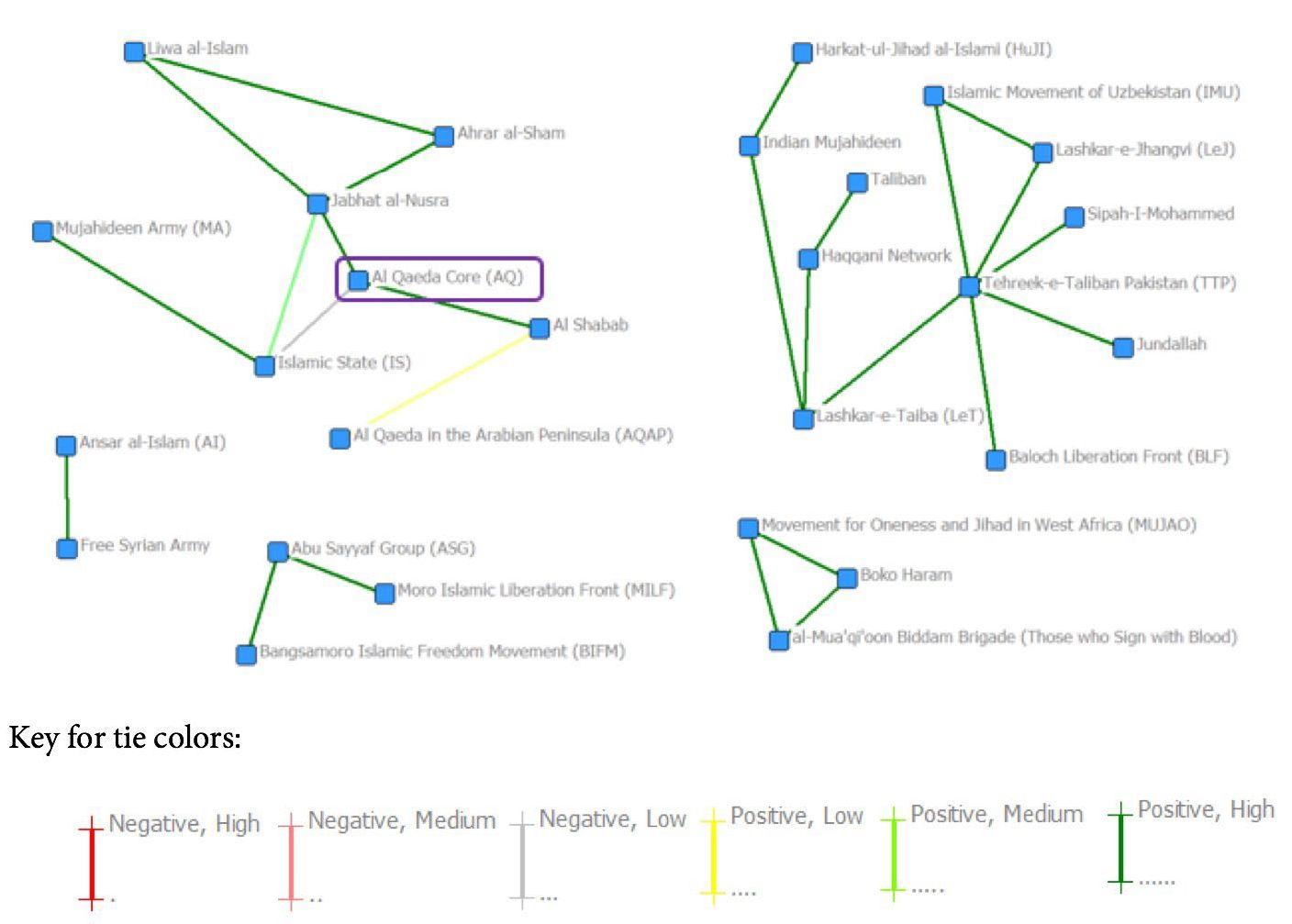

2011-2013

The shift in the network from the 2006-2010 time period to this one is clear in Figure 4. The number of links has been dramatically reduced, as has the number of groups within the network.[36] Part of that reduction may have been a function of the limitation of the MMP and GTD datasets, which only included links up to 2013, two years short of the full five-year interval that the other time periods were allotted. Another possible explanation is the death of Osama bin Laden in 2011. One of Al Qaeda Core’s greatest strengths was the cult of personality around its leadership[37] and the loss of Osama bin Laden was a significant blow to the organization, which may have translated into a period of inactivity within the network as the power void was filled.

The period is significant, however, as it includes the first negative tie between Al Qaeda Core and one of its affiliates, the Islamic State. Up until now, direct connections between Al Qaeda Core and its affiliates have been fairly predictable - a roughly equal mix of positive high, medium, and low ties. Now, however, it only has two Positive High ties and one Negative Low. It would appear that Al Qaeda Core is becoming more selective with its links, only allowing for open affiliation in occasions of high commitment or public censure for its affiliates stepping out of bounds (i.e. the Islamic State).

Centrality

This interval brings a change in centrality as well, as Al Qaeda Core is no longer the top score in each centrality measure, displayed in Table 8. Indeed, it is not even in the top three for any of the measures.

Table 8: Analysis of Data on Centrality, 2011-2013

| First | Second | Third | |

| Betweenness | Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (34.000) | Lashkar-e-Taiba (28.000) | Jabhat al-Nusra (16.000) |

| Eigenvector | Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan (0.642) | Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan and Lashkar-e-Jhangvi (0.366) | Lashkar-e-Taiba (0.335) |

| Closeness | Tehreek-e- Taliban Pakistan (448.000) | Lashkar-e-Taiba (449.000) | Islamic Movement of Uzbekistan, Lashkar- e-Jhangvi, Indian Mujahideen, and Haqqani Network (456.000) |

As was foreshadowed in the 2006-2010 interval, Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan has taken over as the best- connected group in the network.[38] This is likely at least in part because of the larger size of the sub-network in which it is central. Indeed, the network structure of the 2011-2013 interval implies the breakdown of the global network into smaller, more easily managed groups that share some characteristic that binds them together. Just what that characteristic is will be the subject of the subsequent section of this discussion.

Cohesion

The pattern for Al Qaeda Core in the 2011-2013 interval is one of extremes, as displayed in Table 9. It exclusively works with groups that are not in line with its organizational objective, are from a different region, and with which it has some type of established relationship. However, it does not have a preference between regional branches and non-regional branches.

Table 9: Analysis of Data on Cohesion, 2011-2013

| Similar Objectives | Same Region | Core/Regional Branch/ Independent Affiliate | Core/Regional Branch Only | |

| Al Qaeda Core | 1 | 1 | -1 | 0 |

| Whole Network | -0.12 | -0.68 | -0.44 | -0.6 |

Even more compelling are the results from the rest of the network. The pattern established in the previous interval has held, in that groups still tend to work with those that are similar. The preference for groups to work with those who match their alignment (or lack thereof) with Al Qaeda’s objectives has almost disappeared, but the regional preference has increased to be the strongest factor in interaction between groups, followed by whether the group is a regional branch of Al Qaeda. However, the strong preference for working with groups that match one’s own status as a regional branch of Al Qaeda is likely skewed by the small number of regional branches included within the 2011-2013 interval. The regional affinity of the network is especially apparent in Figure 5, which displays the same network map as Figure 4, but with the groups coded by region. There is clearly a division along regional lines within the larger network.

Clearly, the network has lost any semblance of strength as a global AQC-led movement, as it does not meet either criteria required for strength within the context of this project. Rather, the network appears to have taken on a life of its own and returned to the regional focus that was the norm before Al Qaeda’s rise.

Conclusion

While Al Qaeda Core’s network of affiliates has certainly grown over time, the data do not support the doomsday image of a vast and amorphous enemy that its reach implies. Rather, the network ultimately appears to have overextended itself for Al Qaeda Core’s purposes, and the group has gradually lost control.

The period leading up to the 9/11 attacks saw a small, but stable network. Al Qaeda Core was well-positioned as a power-player within a hub-and-spoke network. It did have a mix of groups that were in line with its organizational objectives and those that were not, so it did not meet that aspect of strength. However, the presence of both implies the maintenance of its ideological base, while logistical or doctrinal motivations may account for the presence of dissimilar groups. All in all, it is the organized, tight-knit network that one fears in the image of a Global Al Qaeda.

The five years following 9/11 did not see major changes in the nature of the network, as outlined above. Al Qaeda Core still enjoyed its status as a hub and maintained a mix of ideologically similar and dissimilar affiliates. However, this period saw an expansion in the network as groups flocked to AQC’s banner. More importantly, those groups began to form connections with each other. So while groups maintained their connections with Al Qaeda Core, they no longer relied on it as their sole source of information or direction - they began to rely on each other.

The true breakdown in Al Qaeda Core’s control came during the 2006-2010 interval, where it was not yet ousted as the sole source of information and direction within the network, but its affiliates were clearly poised to take active leadership roles. Even more damaging, it abandoned efforts to maintain ties with ideologically similar groups altogether. There could be any number of logistical or tactical motivations for this, but the ultimate implication is that the ideology of the group is not as important. For an ideologically motivated organization like Al Qaeda, this represents a dangerous departure from its rhetoric and the loss of control over its overall message.

The final interval, although incomplete, is important in that it represents both the increasing regionalization of the network, and the introduction of competition between Al Qaeda Core and its regional branch. Al Qaeda Core had previously been insulated from such negative ties, implying that this new period marks the end of Al Qaeda’s unquestioned leadership. It also seems to point to the end of a global network, as groups increasingly focus on regional conflicts and objectives. The ultimate function of Al Qaeda Core was to inspire the rise of militant organizations and then connect them to each other. As the network grew and Al Qaeda Core’s power waned, rather than prop up its creator, the movement fractured into regional networks. Given the ongoing regionally focused conflicts in which many of these groups operate today, the trend towards regionalism is unlikely to change. However, without additional data, it would be unwise to draw firm conclusions from this interval.

The use of only two datasets, particularly ones that only include data up to 2013 has certainly limited the number and types of links available for this research. In the interests of maintaining data integrity, only data points included within the MMP and GTD datasets were considered. Moreover, links between groups were only included when and how they were presented in the dataset. For example, Al Qaeda Core and Lashkar- e-Jhangvi had a close relationship beginning in the 1990s and continuing through the early 2000s. However, there were only two specific links listed between them in the MMP dataset and none in the GTD - one in 1998 and another in 2001. To preserve consistency in coding, additional ties were not extrapolated from this implied ongoing relationship and therefore these were the only ties between the two groups included within this dataset. However, this methodology does have a trade-off in leaving the dataset open to some gaps. Some of the more prominent omissions have been denoted in the footnotes of this paper for reference, though they are not exhaustive.

In addition, the methods of aggregation—i.e. condensing multiple incidents involving groups into a single tie within a given time period—did not take into account the relative importance of those events. In other words, if there was a public statement of support that went largely unmarked and a joint operation with far reaching consequences for the relationship between two groups, they were weighted the same within the average (i.e. the tie would be weighted 5, as the joint operation is weighted 6 and the public statement 4). Relative importance of ties was partially addressed in the weights themselves, however they do not address specific instances in which a given event that may have a low score within this framework because of its type, but has far reaching consequences on the relationship. This could lead to students of this network noting ties that are weighted higher or lower than they would expect within the network maps. Some notable examples have been highlighted in the text and footnotes, but these are also not exhaustive.

The inclusion of additional links or the expansion of the timeline could certainly alter or strengthen these conclusions. In particular, recent developments with the Islamic State would have likely given the network map in the 2011-2013 time block a very different shape, had it extended to present day. Moreover, as the GTD is almost exclusively a database of terrorist attacks, all incidents taken from it were coded as the highest level of either positive or negative commitment. This has the potential for biasing any results toward a higher level of commitment than might otherwise be observed with access to a greater number of medium and low level incidents.

Finally, the use of a single coder, who is also the researcher, opens the dataset to questions of subjectivity. As such, those interested in continuing research on the topic should do so using more rigorous coding methods, as well as a more expansive dataset.

Ultimately, the image of a vast and tightly controlled network of organizations with Al Qaeda Core pulling all the strings does not seem to be realistic. While that may have been the case on a smaller scale, during the group’s time “under the radar”, its leap to infamy with the September 11th attacks appears to have marked the end of that structure. Indeed, it never fully met the requirements of a strong network, as defined within this project. Rather, we have a large, increasingly regionalized network that, while at least inspired and sometimes aided by Al Qaeda, does not maintain the idea of a unified, globalized movement. In the end, with great networks comes a great lack of control.

About the Author: Victoria Barber is a second-year Master’s student at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, concentrating on International Security Studies. In her research, she utilizes social network analysis to study inter- and intra-group networks of non-state armed groups.

Bibliography

Abdoulaye, Ibbo Daddy, Jason Hanna, and Pierre Meilhan. “Report: Islamist Militants Claim 2 Deadly Attacks in Niger.” CNN: Africa. CNN, 23 May 2013. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Aden Abyan Islamic Army (AAIA).” Terrorist Organization Profile - Aden Abyan Islamic Army (AAIA). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

“al-Badr.” Terrorist Organization Profile - al-Badr. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

“al-Mansoorain.” Terrorist Organization Profile - al-Mansoorain. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Atwan, Abdel Bari . The Secret History of Al-Qa’ida, London: Saqi Books, 2006, p.265-66.

“Asif Raza Commandos.” Asif Raza Commandos. Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Asif Reza Commando Force.” Asif Reza Commando Force. South Asia Terrorism Portal. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Baloch Liberation Front (BLF).” Terrorist Organization Profile - Baloch Liberation Front (BLF). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Berger, J.M.. “ISIS/The Islamic State.” Lecture at the Fletcher School of Law and Diplomacy, Medford, MA, February 17, 2015.

Brams, J. Steven, Mutlu Hande, and S. Ling Ramirez, “Influence in Terrorist Networks: From Undirected to Directed Graphs,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29, 2006, p.703-718.

Carley, M. Kathleen, Diesner Jana, Reminga Jeffrey and Tsvetovat Maksim, “Toward an Interoperable Dynamic Network Analysis Toolkit,” Decision Support System, 43, 2006, p.1324-1347

Carley, M. Kathleen, Ju-Sung, Lee and Krackhardt, David, “Destabilizing Network,” Connections 24 (3), 2002, p.79-92.

Chalk, Peter. “The Bangsamoro Islamic Freedom Fighters: The Newest Obstacles to Peace in the Southern Philippines?” Combating Terrorism Center at West Point, 26 Nov. 2013. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Chapter 6. Foreign Terrorist Organizations.” U.S. Department of State, n.d. Web. 12 Nov. 2014.

Cozzens, Jeffery B. and Magnus Ranstorp, “The Enduring Al Qaeda Threat: A Network Perspective,” in Contemporary Debates on Terrorism, ed. Richard Jackson and Samuel Justin Sinclair, London: Routledge, 2012, 90-97.

Cozzens, Jeffrey B.. “Approaching Al-Qaeda’s Warfare: Function, Culture and Grand Strategy,” in Mapping Terrorism Research: State of the Art, Gaps and Future Directions, ed. Magnus Ranstorp, London: Routledge, 2007, p.127-64, 132

Crenshaw, Martha. “Abu Sayyaf.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 20 July 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Qaeda in the Arabian Peninsula.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 12 May 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Qaeda in the Islamic Maghreb.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 20 Jan. 2013. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Qaeda in Yemen.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 18 July 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Qaeda Kurdish Battalions.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 9 Aug 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Qaeda.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 28 Nov 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al Shabab.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 30 Sep 2013. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Al-Tawhid Islamic Front.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 23 July 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Ansar al-Islam.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 14 Aug 2014. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Boko Haram.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 20 Feb 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Egyptian Islamic Jihad.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 9 Aug 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Global Al-Qaeda.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, n.d. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Haqqani Network.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 15 May 2015.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Harkat-ul-Jihadi al-Islami.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 28 Nov 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Harkat-ul-Mujahedeen.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 28 Nov 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Hizbul Islam.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 10 July 2013. Web.

9 June 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Islamic Army in Iraq.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 23 July 2014. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Jabhat al-Nusra.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 12 Nov 2014.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Jaish-e-Mohammad.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 25 June 2015. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Jemaah Islamiyah.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 8 July 2015.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Lashkar-e-Jhangvi.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 7 July 2015.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Lashkar-e-Taiba.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 3 Aug 2012.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Lashkar-e-Zil.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 25 Aug 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Jaish al-Islam” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 5 Nov 2014. Web. 9

June 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Moro Islamic Liberation Front.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 18 July 2013. Web. 9 June 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Moroccan Islamic Combatant Group.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford

University, 6 Aug 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Mujahideen Army.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 11 Aug 2014.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Second Soran Unit.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 11 Aug 2014.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “Tehreek-e-Taliban Pakistan.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 7 Aug 2012. Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “The Islamic State.” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 15 May 2015.

Web. 4 March 2015.

Crenshaw, Martha. “The Taliban” Mapping Militant Organizations. Stanford University, 2 July 2013. Web. 4 March 2015.

Cronin, Audrey Kurth. “Cyber Mobilization: The New Levee en Masse,” Parameters 36(2), 2006 p.77-87.

“Free Aceh Movement (GAM)” Terrorist Organization Profile - Free Aceh Movement (GAM). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

“Free Syrian Army Founded by Seven Officers to Fight the Syrian Army.” Syria Comment RSS. Syria Comment, 29 July 2011. Web. 9 June 2015.

Gunaratna, Rohan, “Al Qaeda’s Trajectory During and After Bin Laden,” in Terrorism and Counterterrorism, Howard and Hoffman (eds.) Terrorism, p. 206-237.

“Hamas.”Terrorist Organization Profile - Hamas. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Hamzawy, Amr, and Sarah Gebowski. “From Violence to Moderation: Al-Jama’a Al-Islamiya and Al- Jihad.” Carnegie Papers 20 (2010). Print.

Helfstein, Scott and Wright, Dominic. “Covert or Convenient? Evolution of Terror Attack Networks,” Journal of Conflict Resolution, October 2011, pp. 785-813

“Hizb-I-Islami.” Terrorist Organization Profile - Hizb-I-Islami. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

“Hizbul Mujahideen (HM).” Terrorist Organization Profile-Hizbul Mujahideen (HM). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Hoffman, Bruce, “Al Qaeda, Trends in Terrorism, and Future Potentialities: An Assessment,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 26, 2003, p.429-442.

Hoffman, Bruce. “The Myth of Grass-Roots Terrorism,” Foreign Affairs 87(3), 2008, p.133-138.

Hoffman, Bruce. Inside Terrorism. Rev. and expanded ed. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006. 63-71

Hoffman, Bruce and Fernando Reinares, “Conclusion,” in The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat, p. 618639

Holzer, Georg-Sebastian. “Somalia’s New Religious War.” Digital Library. International Relations and Security Network, 31 July 2009. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Islamic Great Eastern Raiders Front (IBDA-C).” Terrorist Organization Profile: Islamic Great Eastern Raiders Front (IBDA-C). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

“Jamaat-e-Islami.” Military. Global Security.org. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Jamiat ul-Mujahedin (JuM).” Terrorist Organization Profile - Jamiat ul-Mujahedin (JuM).

National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Jenkins, Brian Michael. “Statement on Terrorism: Current and Long-Term Threats”, Senate Armed Services Committee on Emerging Threats, November 15,2001. RAND Testimony Series. 2001.

Krebs, E. Valdis, “Mapping Networks of Terrorist Cells,” Connections 24 (3), 2002, p.43-52.

Koschade, Stuart, “A Social Network Analysis of Jemaah Islamiyah: The Applications to Counterterrorism and Intelligence,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism 29 (6), 2006, p.559-575.

Laszlo-Barabasi, Albert, and Eric Bonabeau, “Scale-Free Networks.” Scientific American 288(5), 2003, p.60-69.

“Mahdi Army.” Terrorist Organization Profile - Mahdi Army. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Mayntz, R, “Hierarchy or network? On the Organizational Forms of Terrorism,” Berliner Journal fur Soziologie 14 (2), 2004, p.251.

“Mutassim Bellah Brigade.” Mutassim Bellah Brigade. Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF).” Terrorist Organization Profile - Ogaden National Liberation Front (ONLF). National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Pedahzur, Ami and Perliger, Arie, “The Changing Nature of Suicide Attacks: A Social Network Perspective.” Social Forces 94 (4), 2006.

Pedahzur, Ami and Perliger, Arie, Jewish Terrorism in Israel, New York: Columbia University Press (2009).

Perliger, Arie and Pedahzur, Ami, “Social Network Analysis in the Study of Terrorism and Political Violence,” Political Science and Politics, 44(1), 2011, p.45-50.

Perlinger, Arie. “Terrorist Networks’ Productivity and Durability: A Comparative Multi-Level Analysis.”

Perspectives on Terrorism, 8(4), 2014. http://www.terrorismanalysts.com/pt/index.php/pot/article/ view/359/712.

Picarelli, John T. “The Future of Terrorism.” NIJ Journal, no. 264 (n.d.). https://www.ncjrs.gov/pdffiles1/ nij/228387.pdf.

“Rajah Solaiman Movement.” Rajah Solaiman Movement. United National Multilingual Terminology Database. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Rajah Solaiman Revolutionary Movement.” Terrorist Organization Profile - Rajah Solaiman Revolutionary Movement. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Raufer, Xavier, “Al Qaeda: A Different Diagnosis,” Studies in Conflict & Terrorism, 26 (2003): 391-398.

Rana, Amir. “Vengeance, Frictions Reviving LJ and Sipah-e-Muhammad.” Daily Times Archives. Daily Times, 7 Apr. 2004. Web. 9 June 2015.

Reynolds, Paul. “Iraq Strategy Tough to Enforce.” BBC News. BBC, 4 Oct. 2004. Web. 9 June 2015.

Ryan, Michael W. S. Decoding Al-Qaeda’s Strategy ; the Deep Battle against America. Columbia Studies in Terrorism and Irregular Warfare. New York: Columbia University Press, 2013, p. 227-229.

Sageman, Marc, Understanding Terror Networks. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press 2004.

Sageman, Marc. Leaderless Jihad: Terror Networks in the Twenty-First Century. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press, 2008.

Sahimi, Muhammad. “Who Supports Jundallah?” PBS. PBS, 20 Oct. 2009. Web. 9 June 2015.

Sakhuja, Vijay. “Terrorism or Freedom Struggle: The Free Aceh Movement by Vijay Sakhuja.” TerrorismArticles. Institute of Peace & Conflict Studies, 1 Dec. 2002. Web. 9 June 2015.

Sciolino, Elaine and Eric Schmitt, “A Not Very Private Feud over Terrorism,” New York Times, June 8, 2008.

“Signers in Blood Battalion.” Signers in Blood Battalion. Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Web. 9 June 2015.

“Sirri Powz.” Sirri Powz. Terrorism Research and Analysis Consortium. Web. 9 June 2015.

“The Daily Star Web Edition Vol. 4 Num 338.” The Daily Star Web Edition Vol. 4 Num 338.

The Daily Star, 13 May 2004. Web. 9 June 2015.

“The Holders of the Black Banner.” Terrorist Organization Profile - The Holders of the Black Banner. National Consortium for the Study of Terrorism and Responses to Terrorism (START). Web. 9 June 2015.

Thomas, Timothy L.. “Al Qaeda and the Internet: The Danger of Cyberplanning,” Parameters 23(1) 2003, p.112-123.

Tunnard, Christopher, “Consulting Firm-Analyzing.” Lecture at the Fletcher School of Law and

Diplomacy, Medford, MA, 30 September 2014.

Vennesson, Pascal. “Globalization and al Qaeda’s Challenge to American Unipolarity,” in Recalling September 11th: Is Everything Different Now?, ed. James Burk, New York: Cambridge University Press, 2013, p232-61, 242.

Vidino, Lorenzo, “The Evolution of the Post-9/11 Threat to the U.S. Homeland,” in The Evolution of the Global Terrorist Threat, p. 3-28

Zurutuza, Karlos. “’We Are Suffering Genocide at the Hands of Pakistan’: An Interview with BLF Commander Allah Nazar | VICE News.” VICE News RSS. Vice News, 15 Apr. 2015. Web. 9 June 2015.

Other Coded Data for Groups

Analysis of these features of the dataset was eliminated for the sake of time and space within the article. However, future research could certainly delve more deeply into how these features of the groups relate to patterns of interactions within the network, as well as the longevity of the groups themselves.

Primary Target(s)

In an effort to determine where groups focused their operations, the dataset included the primary targets of each group. The number of primary targets each group could have was not restricted, but rather all of those identified within the Stanford project and other sources were recorded. This allowed for analysis on the combination of targets, (e.g. groups that target primarily western institutions and foreign combatants would likely be more sympathetic to the domestic population than those who target civilians and domestic combatants). The primary target groups identified were as follows:

-

Civilians

-

Foreign Combatants

-

Domestic Combatants

-

Political Figures

-

Western Institutions