Peter Tupper

A Lover’s Pinch

A Cultural History of Sadomasochism

Introduction: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Chapter One: Saints and Shamans

Voluntary Suffering in Christianity

Chapter Two: The Pornography of the Puritan

Chapter Three: Virtue in Distress

Rise of Secular Flagellation in Fiction

Sensibility and Virtue in Distress

Greek War of Independence and Its Consequences

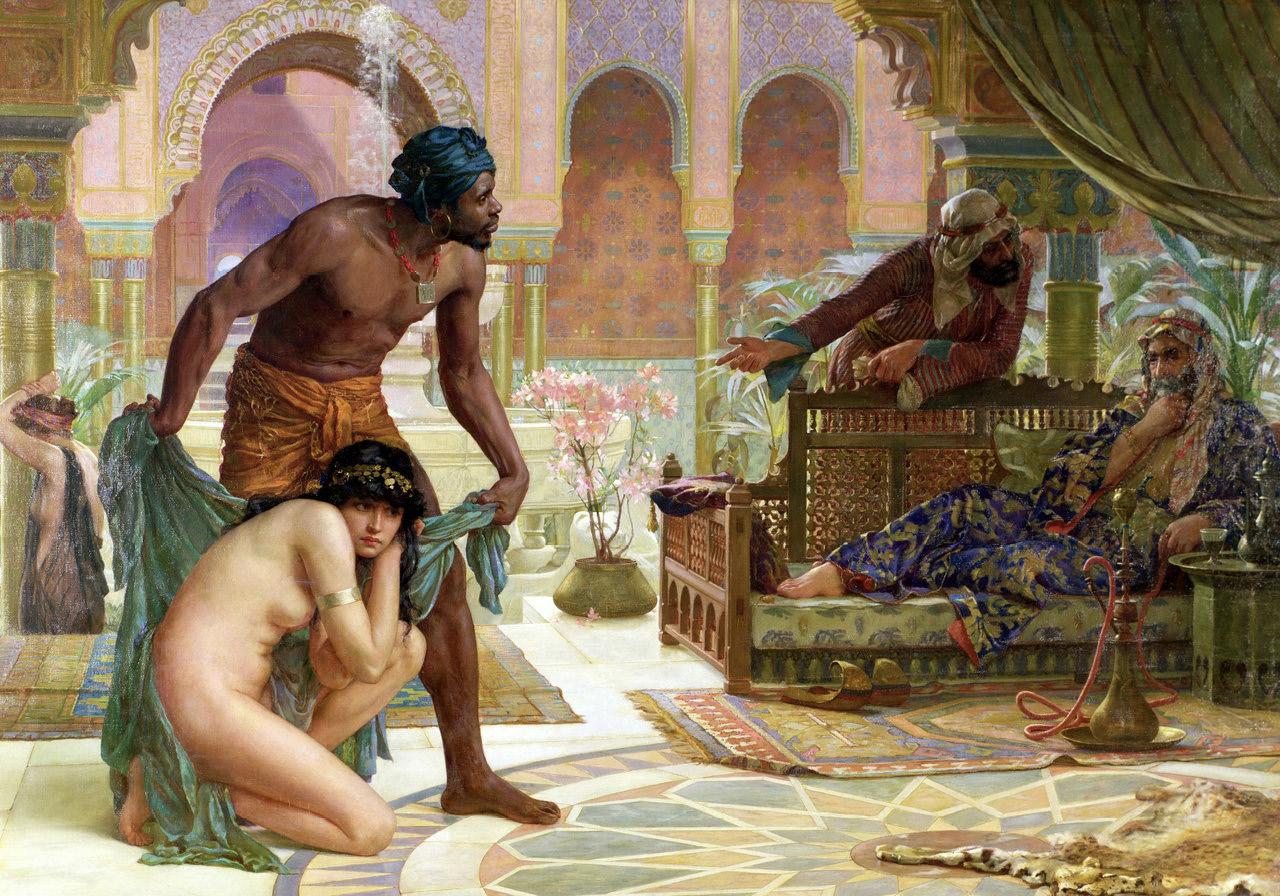

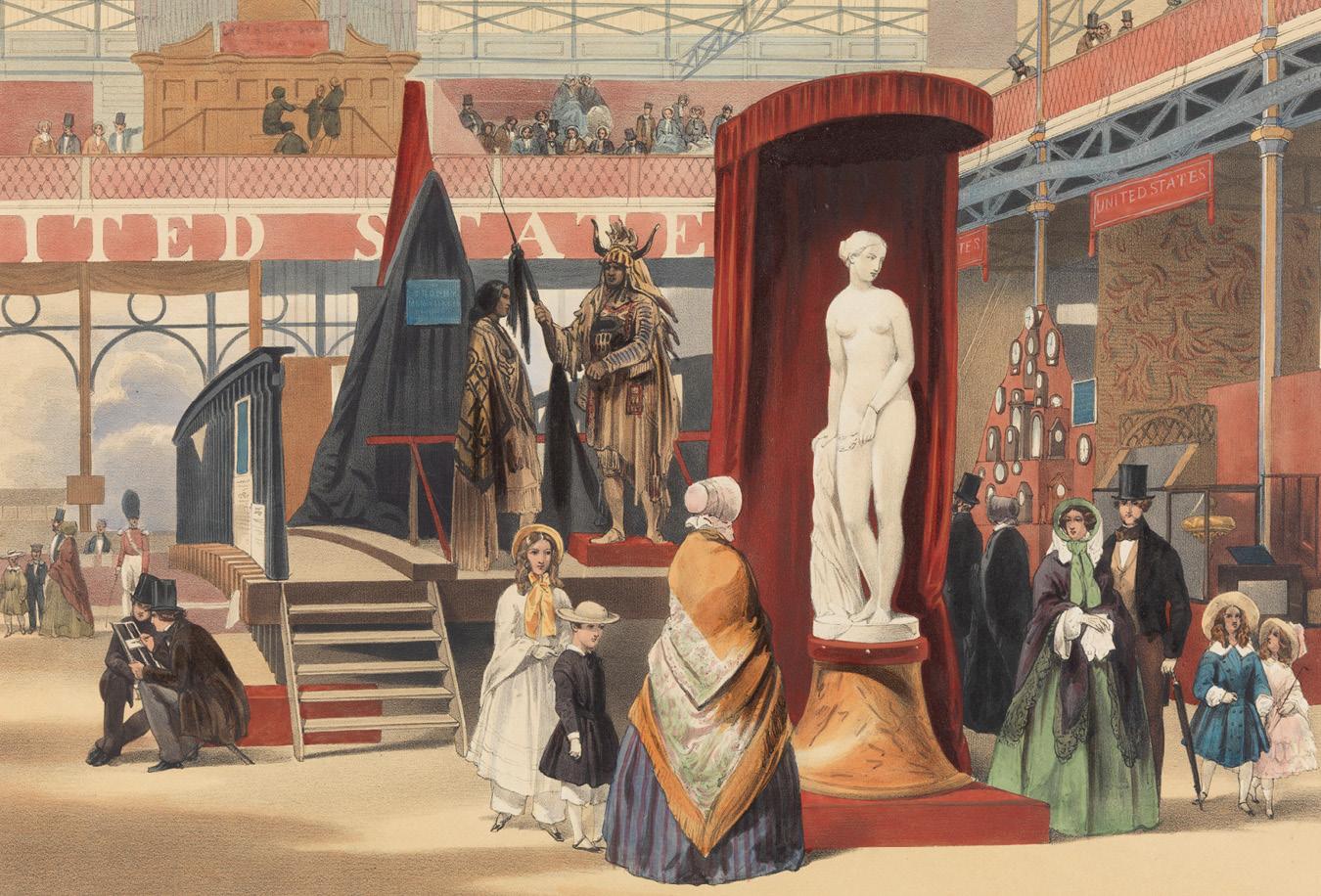

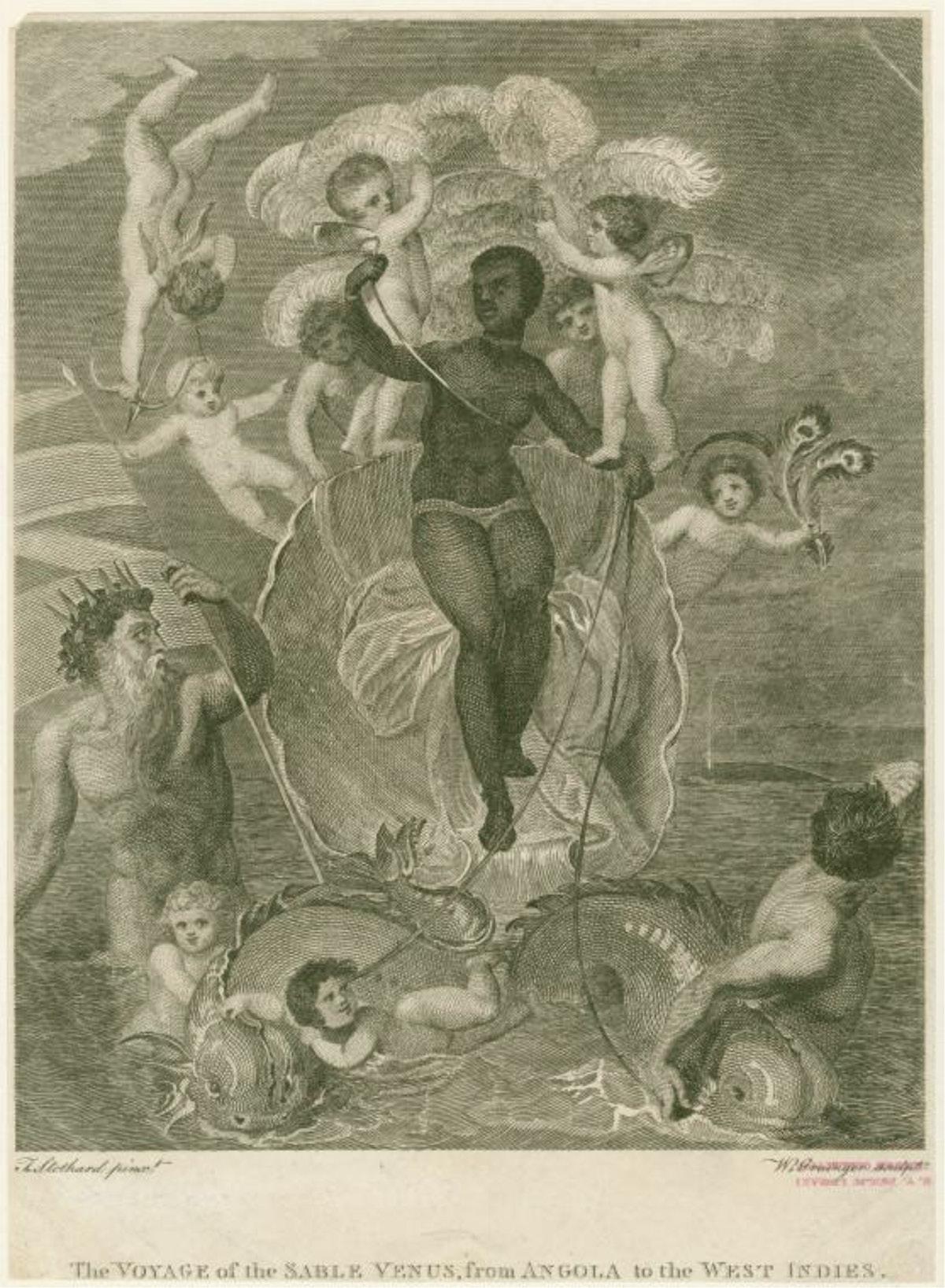

Chapter Five: The Peculiar Institution

Slavery as Place of Sexual Anarchy

Chapter Six: Romance of the Rod

Chapter Seven: Class and Classification

Krafft-Ebing and the Man from Berlin

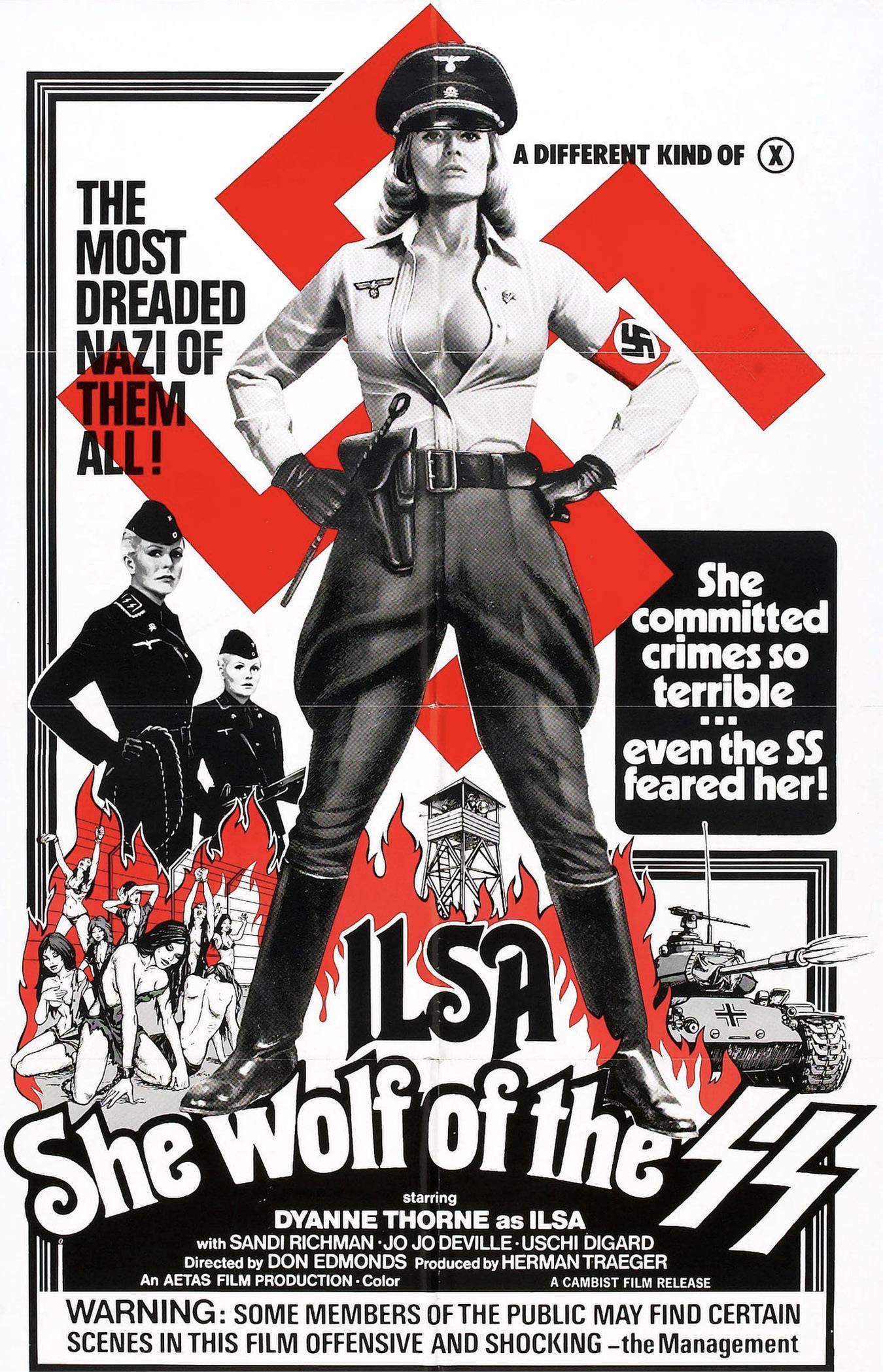

Chapter Eight: Every Woman Adores a Fascist

You Don’t Think I’m a Nazi, Do You?

Chapter Nine: The Velvet Underground

[Front Matter]

[Title Page]

A Lover’s Pinch

A Cultural History of Sadomasochism

Peter Tupper

Rowman & Littlefield

Lanham • Boulder • New York • London

[Copyright]

Published by Rowman & Littlefield

A wholly owned subsidiary of The Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group, Inc.

4501 Forbes Boulevard, Suite 200, Lanham, Maryland 20706

Unit A, Whitacre Mews, 26–34 Stannary Street, London SE11 4AB

Copyright © 2018 by Peter Tupper

All rights reserved. No part of this book may be reproduced in any form or by any electronic or mechanical means, including information storage and retrieval systems, without written permission from the publisher, except by a reviewer who may quote passages in a review.

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Information Available

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Tupper, Peter, author.

Title: A lover’s pinch : a cultural history of sadomasochism / Peter Tupper.

Description: Lanham : Rowman & Littlefield,[2018]| Includes bibliographical references and index.

Identifiers: LCCN 2017055887 (print)| LCCN 2017058499 (ebook)| ISBN 9781538111185 (Electronic)| ISBN 9781538111178 (cloth : alk. paper)

Subjects: LCSH: Sadomasochism—History.| Sex—History.

Classification: LCC HQ79 (ebook)| LCC HQ79 .T87 2018 (print)| DDC 306.77/509—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2017055887

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI/NISO Z39.48–1992.

Printed in the United States of America

[Epigraphs]

“The stroke of death is as a lover’s pinch,

Which hurts and is desir’d.”

—Shakespeare, Antony and Cleopatra, Act V, Scene 2, Ln. 292–93

“You never know what is enough unless you know what is more than enough.”

—William Blake, “Proverbs of Hell,” The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

Introduction: The Marriage of Heaven and Hell

It’s a Saturday night in any major urban center in the Western world, in a darkened hall, in the early years of the twenty-first century. The people here are unmistakable in their hyper-skins of leather, rubber, and lace, their collars and cuffs, their boots, and of course, lots and lots of black.

As the music pulses, people hang suspended in webs of hemp rope from wood and metal frames. Leather straps smack against bare buttocks, evoking moans of pleasure. A man accepts dozens upon dozens of fine needles pierced through his skin. Cool blue alcohol flames ripple across a woman’s naked body, only to be extinguished by the man standing over her. A woman carefully slips her entire, well-lubricated fist into the vagina of another, and they never break eye contact. A man leans against a wall, shuddering in pleasure each time another man snaps a single-tailed whip at his bare back, with a sound like a rifle shot. A French maid in black-and-white rubber minces across the room on six-inch heels. A man rains his fists down on the soft, meaty parts of his lover’s body, and stops the instant she says “Yellow.”

Their actions are paradoxical. They speak of “punishment” and “torture,” and their bodies are beaten, cut, pierced, burned, and bound, but the mutual goal is pleasure. They precisely measure sensation, exploring to find the outer limits. There is endless variation, innovation, experimentation, transformation. The weak become strong, the old become young, men become women, women become men, pain becomes pleasure, confinement becomes freedom. This is a laboratory for developing new pleasures and intimacies that cannot be had any other way. Yet there is an order to this, a precise etiquette that regulates but does not confine.

Beyond these night rituals, sadomasochism has spread into the greater culture. Surf through channels, page through magazines, click through the web. Heroes and villains wear black leather and rubber. Whip-wielding dominatrices sell everything from cars to breath mints. Pop singers rhapsodize over pain mixed with pleasure, captivity, submission, and dominance. Every fashion designer has their momentary dalliance with high-heeled boots; dark, shiny coats; wasp-waisted corsets. The aesthetic is so ubiquitous that it is scarcely noticeable, almost cliché.

The question I have to ask is: Where did all this come from? Where did the idea that pain and pleasure are intertwined begin? How did black leather acquire its potent erotic charge?

Today, there are many instructive works on BDSM, ranging from techniques to relationships. But to understand the history is difficult. In my readings and conversations, I usually found only myths and generalizations. Some people tell tall tales of slave-owning houses that date back to pre-Revolutionary France or even the Roman Empire. Others allude to physical ordeal rituals in indigenous cultures but are vague about any connection to modern practices. Some recite a list of the usual suspects—Sade, Sacher-Masoch, motorcycle gang culture, medieval flagellants, Story of O—but there is no coherent history, no genealogy linking these people, groups, texts, and artifacts together and showing how they grew together into the modern BDSM culture. The name itself is a slightly awkward portmanteau of Bondage and Discipline, Dominance and Submission, Sadism and Masochism, and Slave and Master. It is apt for a subculture and a style that conglomerated together haphazardly instead of being designed.

Michel Foucault, the French philosopher and practicing sadomasochist, wrote,

Sadism [and masochism] is not a name finally given to a practice as old as Eros; it is a massive cultural fact which appeared precisely at the end of the eighteenth century, and which constitutes one of the greatest conversions of Western imagination: unreason transformed into delirium of the heart, madness of desire, the insane dialogue of love and death in the limitless presumption of appetite. Sadism appears at the very moment that unreason, confined for over a century and reduced to silence, reappears, no longer as an image of the world, no longer as a figura, but as language and desire.[1]

However, nothing is created spontaneously. There are always antecedents and contributing circumstances. Before “the end of the eighteenth century” there must have been, and were, people and things who contributed. This book will examine customs and relationships that may resemble BDSM, and may be the source material for the fantasy that drives BDSM, but are not. This is a story of transformation.

Somewhere, hidden beneath secrecy and mythology and ignorance, is the network that connects all those different things together and leads to other, unexplored worlds. These are not the main thoroughfares of history, but the “cunning passages, [and] contrived corridors.”[2]

The hidden history of consensual sadomasochism needs to be told.

Criminality

Modern advocates of the BDSM community are quick to state that consensual sadomasochism is not rape or abuse, and that terms like “master and slave” or “punishment” should not be taken literally. However, to explore this particular branch of history requires confronting humanity’s legacy of violence and oppression. The grotesque crimes of the Marquis de Sade, the tyranny of American slavery, the corporal punishment of Victorian children, and the atrocities of fascism are just a few of the disturbing subjects that must be examined to discover the links between them and consensual sadomasochism.

Acknowledging the relationships between modern BDSM and this history is not to condone or excuse these events. The link between the horrors of slavery and the consensual, pleasurable Master-slave relationships of the early twenty-first century is long and winding. It is comparable to the connection between the athleticism and discipline of modern Olympic fencing and the brutal business of thrusting a piece of sharpened steel through the vital organs of a fellow human being on the battlefield. They are related, but one is violence and the other is an art or game, an indirect reflection of reality, bounded by rules.

There are few, if any, straight lines in the history of BDSM. The most apt metaphor for this particular field of human endeavor is not a branching tree, or a labyrinth, or even Foucault’s “archeology,” but a house of mirrors. Instead of direct imitation, there is endless reflection, distortion and mimicry, collage and parody, copies of copies. The sadomasochistic imagination is both mobile and transformative.

In Sigmund Freud’s essay “A Child Is Being Beaten” (1919), he explored his patients’ masochistic fantasies, asking:

Who was the child that was being beaten? The one who was himself producing the phantasy or another? Was it always the same child or as often as not a different one? Who was it that was beating the child? A grown-up person? And if so, who? Or did the child imagine that he himself was beating another one? Nothing could be ascertained that threw any light upon all these questions—only the hesitant reply: “I know nothing more about it: a child is being beaten.” ...

In these circumstances it was impossible at first even to decide whether the pleasure attaching to the beating-phantasy was to be described as sadistic or masochistic.

Freud later established that the fantasizer is constantly shifting their point of view, and the meaning they attach to the fantasy. Even if the fantasizer explicitly identifies with one position, the subjective experience of the other does matter. In a sadomasochistic relationship, the masochist/submissive’s subjective experience matters very much to the sadist/dominant’s involvement. There’s no point in playing with an automaton that merely goes through the motions. The submissive also has his or her expectations about the dominant’s subjectivity.

Freud’s daughter, Anna Freud, wrote another essay that explored the sadomasochistic imagination, “Beating Fantasies and Daydreams” (1922),[3] which showed how the fantasizer repeatedly revises the fantasy scenario.

She described a girl (herself), who buried her childhood beating fantasies under a layer of “nice stories,” full of affectionate, orderly families. In her adolescence, she happened across a boy’s book about the Middle Ages and read a story, which she only remembered in vague detail, that she then turned into the master narrative for a new set of fantasies. These bore only slight resemblance to the original story.

The original story had been so cut up into separate pieces, drained of their content, and overlaid by new fantasy material that it was impossible to distinguish between the borrowed and the spontaneously produced elements. All we can do therefore—and that was also what the analyst had to do—is to drop this distinction, which in any event has no practical significance, and deal with the entire content of the fantasied episodes regardless of their sources.

The material she used in this story was as follows: A medieval knight has been engaged in a long feud with a number of nobles who are in league against him. In the course of a battle a fifteen-year-old noble youth (i.e., the age of the daydreamer) is captured by the knight’s henchmen. He is taken to the knight’s castle where he is held prisoner for a long time. Finally, he is released.

Instead of spinning out and continuing the tale (as in a novel published in installments), the girl made use of the plot as a sort of outer frame for her daydream. Into this frame she inserted a variety of minor and major episodes, each a completed tale that was entirely independent of the others, and formed exactly like a real novel, containing an introduction, the development of a plot which leads to heightened tension and ultimately to a climax.[4]

There are only two essential characters in this variable scenario: the innocent youth and the brutish knight. The fantasizer plays the narrative out in many different ways. For example:

The prisoner has strayed beyond the limits of his confine and meets the knight, but the latter does not as expected punish the youth with renewed imprisonment. Another time the knight surprises the youth in the very act of transgressing a specific prohibition, but he himself spares the youth the public humiliation which was to be the punishment for this crime. The knight imposes all sorts of deprivations and the prisoner then doubly savors the delights of what is granted again.

All this takes place in vividly animated and dramatically moving scenes. In each the daydreamer experiences the full excitement of the threatened youth’s anxiety and fortitude. At the moment when the wrath and rage of the torturer are transformed into pity and benevolence—that is to say, at the climax of each scene—the excitement resolves itself into a feeling of happiness.[5]

The narrative was rewritten to suit the momentary desires of the fantasizer. Rape became ravishment became seduction became love. The stereotypical rape fantasy does not mean the fantasizer wants to be raped, but that the imagination takes a real-world experience (directly experienced or not) and revises it until it becomes a scenario for personal satisfaction that allows pleasures that are not available in other ways. The fantasizer re-channels anxiety into a source of pleasure by heightening dramatic tension and delaying the release.

Thus, early twenty-first-century consensual Master-slave relationships are not a direct imitation of antebellum American slavery (or any other form of violence throughout history), but a scenario that has been told and retold, with certain elements subtracted and others added, until it bears only the slightest resemblance to the original. The relationship between reality and BDSM cannot be reduced to simple imitation. It is a process of interpretation, becoming a performance or ritual.

Over the centuries, people have drawn upon different cultural anxieties to derive fantasy pleasures, such as the fears of the Roman Catholic Church, the Islamic societies of North Africa and the Middle East, antebellum American slavery, the Nazis, alien invaders, and others. All of these fantasies have little to do with the historical realities, and are instead more like myths, archetypal stories with different set dressing and costumes.

Definition

A fundamental problem is the question of what is and isn’t sadomasochism? American Justice Potter Stewart famously said, “I know it when I see it,” with regards to pornography, but that won’t suffice. Were Chinese foot binders or medieval Christian flagellants practicing sadomasochism? Or were they doing something else that resembled sadomasochism but wasn’t? “Just erotic. Nothing kinky. It’s the difference between using a feather and using a chicken,” as the saying goes.[6] For some people, kinky is sex with the lights on.

Like “pornography,” “sadomasochism” is strongly defined by the legal and medical attempts to regulate it. “Sadism” and “masochism” were originally like “homosexuality,” medical terms that designated aberrant sexual behaviors exhibited by individuals. However, this book is less interested in sadistic or masochistic individuals than in sadomasochistic interactions between individuals, which are the root of sadomasochistic culture.

Kinky can be defined as the opposite of vanilla—that is, “normal,” but that definition is tautological. Scientists don’t even like to use the term “normal” anymore. They prefer words like “normative.” Alfred Kinsey and his followers showed that what “normal” people do is quite varied, and shifts throughout lives and over time. Kink as a distinct entity becomes even fuzzier when it starts to influence the mainstream. Some fetishes are so common they have effectively become normative: high-heeled shoes, for instance. Other fetishes, such as corsets or smoking, were once nearly universal in common life and are now rare. For nineteenth-century European women, corsets were everyday wear, but now are worn almost solely as costume. Only a few generations ago, smoking was a ubiquitous habit, but it has become increasingly rare in North America. We may one day see smoking become primarily or solely a fetishized practice, done as an erotic performance.

To create a working definition as a starting point: “BDSM is a form of consensual erotic play.”

While “erotic” may seem self-evident, it is actually more complex. Sadomasochism and fetishism, along with homosexuality, became visible in the late nineteenth century because certain people were being aroused by things that did not fit the standard definition of “normal” sex: heterosexual coitus leading to conception. However, many people practice BDSM or similar activities for reasons other than sexual arousal or release, and prefer to keep their sexuality separate from their play.

In a broader definition, BDSM is playing with the body: testing, modifying, experimenting. The goal of this may be physical pleasure, which may or may not include sexual arousal, or it may produce other sensations that the person desires. Implicit in the definition of BDSM is the idea that people have a right to do with their bodies as they wish, and to pursue pleasure by whatever means. That can be expanded to mean that people have a right to use their bodies to pursue things other than pleasure.

Many people who practice BDSM also participate in the modern primitive and body modification subcultures. For them, sadomasochism is a spiritual practice, not sexual. I once witnessed a suspension piercing event, which involved people being suspended by metal hooks embedded in their bodies. This was not considered a sexual event; teenage minors were allowed into the space to observe, though not participate. I likened the practice to BDSM to the organizer. “It’s not SM,” she told me indignantly. “It’s just people playing around with their pain thresholds.”

“That sounds like SM to me,” I told her.

She disagreed.

Throughout human history, there are many examples of people voluntarily undergoing physical ordeals. However, for the most part these are religious or military practices. They must be performed at certain times and in certain ways by people who are properly authorized. While they are technically consensual, they are culturally prescribed, and to refuse them is to face social disapproval.

BDSM is a form of human play, however, and therefore is optional, not obligatory. There is no social cost to not doing BDSM. Play also allows for experimentation and variation. Participants can try new things, invent new roles, props, and techniques. People enter a BDSM interaction with the tacit understanding that they choose their role, one that has nothing to do with the role society assigns to them. To be dominant or submissive, top or bottom, is recognized as a personal choice, not determined by a person’s gender, race, or other characteristics.

Roger Callois, in his book Man, Play and Games (1961),[7] defined four different modes of play which can be combined in various ways. The modes are agon, or competition; alea, or randomness; mimesis, or mimicry and playing roles; and ilinx, meaning the alteration of perception. Sadomasochism is a form of play that includes one or both of ilinx, as perception is altered by bondage, flagellation, sexual stimulation, or other methods; and mimesis, as the participants perform the roles of master/slave, cop/criminal, interrogator/prisoner, et cetera.

Callois also defined a continuum between ludus, structured activities with rules, and paidia, unstructured and spontaneous activities. BDSM falls towards the ludus end of that continuum, and the most important rule is consent.

Unlike the other elements mentioned above, this one is not optional. In both “Safe, Sane and Consensual” and “Risk-Aware Consensual Kink” philosophies, consent is essential. Without consent in the interaction, it isn’t BDSM. It is brutality and victimization. Consent can turn what would be a traumatizing experience into a life-affirming one. Consent, as we define it, couldn’t really exist until the creation of modern liberal ideas of personhood, self-determination, and rights.

Though this definition doesn’t cover the full range of topics this book will discuss, it is enough to identify a core group of symbols and practices.

Problems to Surmount

There are many difficulties in uncovering the history of a subculture buried beneath layers of shame, secrecy, and censorship.

The history of alternative sexuality is full of holes left by records lost or destroyed by their owners out of shame, or by others trying to suppress the ideas and images. For every person in the past who left evidence of their sexual interests and activities, there are untold numbers who didn’t. We can only guess how many other Victorians led secret lives like Arthur Munby and Hannah Cullwick, or whoever really wrote The Lustful Turk or Memoirs of Dolly Morton.

During the excavation of Pompeii, unearthed erotic art and phallic icons were destroyed on the spot, locked up in secret collections in museums, or hidden away from tourists.[8] The complete, unpublished manuscript of Richard Francis Burton’s The Perfumed Garden was burnt after his death by his wife Isabel. The bulk of Henry Spencer Ashbee’s collection of erotica was destroyed by the trustees of the British Museum. In 1913, the American censor Anthony Comstock bragged he had disposed of 160 tons of “obscene literature” over his career.[9] The Nazis immolated a hundred thousand books and manuscripts from the library of Dr. Magnus Hirschfeld’s Institute of Sexology, while a brass band played.[10] Even in recent times, a corset aficionado’s collection was destroyed after his death by his family.[11] It’s more by luck than anything else that the evidence of the secret lives of Hannah Cullwick and Arthur Munby has survived.

Simple neglect has caused the loss of even more records. Most people consider pornographic broadsheets, magazines, newspapers, films, and other media unworthy of archiving. Only a few institutions, such as the Kinsey Institute, the Leather Archives and Museum, or the Carter-Johnson Memorial Library, work to preserve such material.

Even the records that do survive may not be truthful. My Secret Life, a massive sexual autobiography of a Victorian gentleman, is frequently cited by scholars of sexual history, but its authorship is a mystery. Stephen Marcus, in The Other Victorians (1964), says that the author was a real person, while Ian Gibson’s The Erotomaniac (2001) says it is a composite of anecdotes and fantasies from upper-middle-class gentlemen, compiled by Henry Spencer Ashbee. The true identity of the author, “Walter,” will probably never be known.

Some sources may exaggerate out of bravado. Was Richard Burton sincere in his offer to bring back the skin of an African maiden (preferably taken while she was alive) so that his friend Frederick Hankey would have something to bind his copy of the Marquis de Sade’s Justine?[12] Or was it just a bit of colonialist black humor?

Other sources may misrepresent out of wishful thinking. Henry Spencer Ashbee, perhaps the first person to study pornography academically, was an exhaustive bibliographer, but he wasn’t a critical reviewer. He described a novel called The Mysteries of Verbena House; or, Miss Bellasis Birched for Thieving as “a most minute and truthful description of a fashionable Brighton seminary for young ladies, of the present day, and the tale turns upon the corporal punishments administered to the fair inmates.”[13] Whether he actually believed this, or just played along with the fantasy, is impossible to say.

This investigation requires a balance between sticking to the historical record and erring on the side of caution, and drawing connections between the different sources to tell the story.

In the absence of hard facts about the history of sadomasochism, people have filled in the gaps with mythology. In her keynote speech at the 2005 South Plains Leatherfest, erotica writer Laura Antoniou asked the question, “And how can we even begin to address [BDSM] history seriously when so much of who and what we are is partial—if not purely—fiction?” Antoniou wrote the Marketplace books, which draw upon the widespread and long-running fantasy of a secret network of modern-day slave markets and aristocratic estates.[14] This put Antoniou in the awkward position of the debunker of a myth she helped spread.

Thus, we have a culture of people with self-chosen titles, rules, and roles, often based on fictitious sources, such as the Marketplace books or John Norman’s Gor novels. The BDSM scene has persistent legends of “training houses,” secret establishments where masters, mistresses, and slaves are trained in “real” BDSM. If such institutions ever existed, they conceal themselves better than the CIA and the Mafia.

The so-called Old Guard, the first generation of leathermen that grew out of the post–World War II biker culture, is frequently invoked to proclaim some way of doing BDSM as more authentic or “real” than others. The early leather culture was far from monolithic, with a wide variation in customs, symbols, and practices, and also far less diverse in membership and interests than the modern BDSM scene.

Myths can make for entertaining and arousing fantasies, but they can also obscure understanding. Twisted Monk, one of the leading bondage rope suppliers in North America, wrote on his blog in 2006:

Honorable samurai and secret European houses did not write our history; rather it was born in back alleys and leather bars by pornographers, queers and sexual outlaws. We should celebrate this rather than attempt to re-imagine it.[15]

***

The true history of consensual sadomasochism is a story of misfits, hustlers, and visionaries, dreams and nightmares, and the strange vicissitudes of human nature, transforming pain and hatred into pleasure and love. To understand it requires the human ability to accept and embrace irony and paradox. The connection between the self-flagellating Christians of the first century and the twenty-first-century bondage burlesque performers is long and winding, but it is there.

Gay writers speak of “your first lover’s first lover,” a lineage of chosen bonds instead of familial ties, which in principle can go back for centuries. I would like to find a similar lineage of shared desire and imagination for kinky people, “your first play partner’s first play partner.” This is that untold story.

Chapter One: Saints and Shamans

Where to begin? A researcher can’t just start with the BDSM subculture of the early twenty-first century and proceed backwards. The historical record soon dissolves into clouds of myth and speculation, if not ignorance. The problem can be approached from another angle: Take what we know of early societies and look for examples of sadomasochistic activity. That has its own problems, as other cultures have very different views of pain and pleasure, or sex and religion.

That humans fear and avoid pain would seem to be obvious, hence the use of pain in punishment throughout history. But a moment’s thought shows that humans have willingly accepted pain in many times and in many places. Not only do they engage in activities to which pain and suffering is incidental, such as surgical treatment, warfare, or athletic competition, but they also do things in which pain is essential. Depending on the context, experiencing pain can be seen as having positive value.

Transcendence through Pain

The most common example of this is religious customs. Many faiths have some form of physical ordeal ritual, performed in both ancient times and the present day, both individually and collectively, privately and publicly.

The Sioux and other Plains peoples of North America perform the Sun Dance, a complex four-day ritual of spiritual renewal in which some participants pierce the skin of their chests with sticks or eagle claws and then lean away from a sacred tree until the piercings rip free. Other participants drag buffalo skulls or even hang suspended off the ground from their piercings.[16]

In India, the Tamil people celebrate Thaipusam in honor of the war god Murugan, and perform the Kavadi Attam dance of carrying burdens. Devotees ritually fast, abstain from alcohol, and perform other austerities in preparation. While most of the worshipers carry small pots of milk on their heads or other offerings, a few practice more radical devotions involving piercing their cheeks or tongues with vel skewers, hanging weights from hooks embedded in their back or chest, or carrying the vel kavadi, a portable altar supported by 108 vels embedded into the bearer’s chest and back. Their symbolic labor is made sacred by doing it in as difficult and painful a way as possible.[17]

On the Day of Ashura in the Islamic calendar, some Shiite Muslims mourn the death of the prophet Mohammed’s grandson by practicing Tatbir, striking themselves on the head with a blade or hitting their back and chest with blades attached to chains.[18]

The Yoruba people of West Africa engage in mutual flagellation with whips, switches, or staves as part of their festivals.[19]

In these examples, people voluntarily receive pain as part of a religious experience, and not as a sexual act. It’s important to note that these are not “primitive” forms of religious expression that certain human cultures have evolved beyond. These acts of flagellation and other forms of asceticism occur in specific religious contexts as well-established customs, in order to minimize lasting injury.

Western Classical societies had their own uses for the physical in the sacred. For example, the Etruscan “Tomb of the Whipping,” built circa 490 BCE, includes frescoes of people in sexual acts. One of the frescoes shows two men in intercourse with one woman. One man appears to be slapping the woman’s back with an open hand, while the other man has raised a small stick or cane over the woman’s buttocks. Etruscans added erotic art to their tombs to repulse demons, suggesting that flagellation and spanking had both sexual and spiritual aspects.

Plutarch described the Roman festival of Lupercalia: “At this time many of the noble youths and of the magistrates run up and down through the city naked, for sport and laughter striking those they meet with shaggy thongs. And many women of rank also purposely get in their way, and like children at school present their hands to be struck, believing that the pregnant will thus be helped in delivery, and the barren to pregnancy.”[20]

The ancient Roman city of Pompeii, buried by a volcanic eruption in CE 79 and rediscovered in 1749, is rife with sexual art. The ubiquity of sexual imagery led early archaeologists to theorize that Pompeii was full of brothels and that ancient Rome was a sex-obsessed culture. Later archaeologists stated that these phalli were symbols of protection, health, and fertility, something the Romans just felt comfortable having around.

Flagellation appears in a semi-erotic context in a fresco in one of the city’s buried houses. The Villa of the Mysteries is a large house that scholars initially thought to be a brothel or temple because of the nude frescoes on the walls. Later archaeologists decided it was actually a private home and the art depicted a sequential narrative about preparing a young bride for marriage in the mystery cult of Dionysius.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

Reading the images around the room, the narrative starts with a woman in street clothes, then a mother with son, then a pregnant woman with a laurel crown carrying cakes, and so on. The images are tranquil until a woman is startled; she draws away from something in surprise, her cape in violent motion over her.

Courtesy Wikimedia Commons

As one enters the room, the first image visible is Dionysius sitting with his head almost in the lap of his lover, Ariadne (see Figure 1.1). To the right of them is an undressed woman kneeling before a large phallus in a basket, covered with purple cloth. Immediately to the right of that is a standing female figure with dark wings, identified as a “female demon.” Unlike the other female figures in the fresco, who are nude or in dresses, she wears boots or sandals, a knee-length skirt, and a belt suitable for fighting or another athletic activity. Her right hand wields a cane or switch, in full backswing, apparently beating the kneeling woman on the other side of the room’s corner (see Figure 1.2). Here, a woman kneels, back and buttocks exposed, resting her face in the lap of another, clothed woman. After that, a nude woman dances with cymbals. The final image is a maidservant arranging a young woman’s hair in the style reserved for brides.

Although there are other interpretations to this work, the connection between sexual pleasure, physical pain, and fertility is clear. The narrative shows flagellation as part of the marriage/fertility rite.[21]

Ritual

These voluntary physical ordeals, found across the world and throughout history, are aspects of rituals. Ritual is a powerful force in human affairs, used to resolve conflicts, regulate social change, and guide individuals and societies through their lives. In some rituals, individuals transition from one social role to another, such as weddings, initiations into military, religious or fraternal orders, or graduations from school. Other rituals are periodic events in which social roles change for prescribed periods of time, such as holidays or sporting events. Rituals may be widespread social practices of a given culture, or small groups or individuals may develop their own rituals for their purposes. By viewing sadomasochistic practice as ritual, we can understand how sadomasochism works in the context of culture, instead of viewing it as a pathology of individuals.

Anthropologist Victor Turner, in his book The Ritual Process (1969), defined ritual as a three-step process of separation, liminality (derived from limen or threshold), and aggregation. Fittingly, a modern sadomasochistic interaction is often called a “scene,” suggesting the theatricality and performance that is a key aspect of ritual. The archetypal BDSM scene repeats the three stages of the ritual.

In separation, ritual participants break from their usual routine and their social role in it by fasting, changing clothing, or traveling away from regular places. In the BDSM scene, participants abandon their regular attire and dress in a particular fashion (leather or latex fetishwear, lingerie, costume, or nudity), travel to a particular place of seclusion (a dungeon or playspace), adopt different names or titles (scene names, “Master,” “Mistress”), and otherwise separate from their everyday lives.

In the liminal phase of the ritual, participants inhabit a social space with new social rules that can be inversions of normal society (e.g., women dominate men, blacks dominate whites) or exaggerations (e.g., wives become slaves). People experience a heightened awareness, a sense of expressing their true selves. Sexual arousal may be a part of this, but the release from the usual social roles is the bigger appeal. Mundane objects acquire great symbolic value; for example, bread and wine becomes the body and blood of Christ, to be consumed as a symbolic act of cannibalism. States that are avoided and discouraged in the regular world are embraced and encouraged: dirtiness, sexual aggression, captivity, dependency, and so on. Turner writes:

Liminal entities, such as neophytes in initiation or puberty rites, may be represented as possessing nothing. They may be disguised as monsters, wear only a strip of clothing, or even go naked, to demonstrate that as liminal beings they have no status, property, insignia, secular clothing indicating rank or role, position in a kinship system—in short, nothing that may distinguish them from their fellow neophytes or initiands. Their behavior is normally passive or humble; they must obey their instructors implicitly, and accept arbitrary punishment without complaint. It is as though they are being reduced or ground down to a uniform condition to be fashioned anew and endowed with additional powers to enable them to cope with their new station in life.[22]

Turner contrasts social structure, the rules and roles of society, with what he calls communitas, the sense of being emotionally, intuitively integrated into humanity, soul to soul contact. The purpose of a rite of passage is to take a person out of structure, make them experience communitas so they understand that society is more than just rules and roles, and put them back into society.

People can experience liminality without necessarily reaching communitas, and may not want to. Liminality may be its own reward, as in liminoid rituals, in which the participants don’t experience lasting changes in social status. As Turner wrote, “For the hippies—as indeed for many millenarian and ‘enthusiastic’ movements—the ecstasy of spontaneous communitas is seen as the end of human endeavor.”[23]

Liminality is not always achieved through gentle means, and may employ literal or symbolic ordeals of discomfort, deprivation, or outright pain.

We very often do find that the concept of threat or danger to the group—and, indeed, there is usually real danger in the form of a circumciser’s or cicatrizer’s knife, many ordeals, and severe discipline—is importantly present. And this danger is one of the chief ingredients in the production of existential communitas, like the possibility of a “bad trip” for the narcotic communitas.[24]

Radically changing a person’s sensory experience is a common method of altering his or her consciousness to experience liminality. There are many techniques toward this end, including dancing, chanting, drumming, flagellation, burning, cutting, fasting, dehydration, immersion in cold water, ingesting psychoactive drugs, sweat lodges, or piercing; paradoxically, the same effect may be achieved by under-loading the sensorium by blindfolding, psychoactive drugs, or isolation.

Ariel Glucklich’s book Sacred Pain (2001) explains how pain, or other disruptions in a person’s sensorium, is used in ritual.

To sum up three chapters in three sentences, the more irritation one applies to the body in the form of pain, the less output the central nervous system generates from the areas that regulate the signals on which a sense of self relies. Modulated pain weakens the individual’s feeling of being a discrete agent; it makes the “body-self” transparent and facilitates the emergence of a new identity. Metaphorically, pain creates an embodied “absence” and makes way for a new and greater “presence.”[25]

Pain is both a sign that psychological transformation is happening and an agent of that change. The anticipation of pain, such as from the sight of weapons, even if they are not used, can have the same effect.

Hurting initiates in rites of passage and initiations is a form of applying force on them. Force, or power, is brought to bear by those who already belong to the adult world, or to the society of the initiated. But initiates are not simply brutalized, and highly ritualized force becomes sacrificial pain. Rites of passage are rites of supercession. In order to become adults, the initiates sacrifice or give up their lesser identity as boys or girls. Instead of being victims—however symbolic—the children must hurt in a voluntary manner. Only then can the psychological mechanism of self-sacrifice become effective.... If adults were to hurt their children in a brutal manner and with no ritual, the pain would not be transformative.[26]

The ritual structure creates a social container for the violence, a time and place in which transgression from norms are prescribed and performed in a controlled manner, understood by the ritual’s officiants.

In the BDSM scene, the participants inflict or experience deprivation, confinement, and threatened or actual violence, through bondage (such as rope, handcuffs, or restrictive clothing), sensory deprivation (such as blindfolds), impact play (such as spanking or flogging), sensation play (such as scratching or ice), or other methods. Particular objects are assigned great symbolic meanings, both of arousal and of power or submission: fetishized items like high-heeled shoes, leather or rubber clothing, or cigarettes. Social roles related to age, gender, race, and other categories may be radically different, exaggerated or even inverted, through ageplay, genderplay, or raceplay. Derogatory terms like “slut” or “whore” or “pig” become expressions of desire, worthiness, and even affection. Transgression is not just allowed, but encouraged.

In the final step, aggregation, the participants have achieved psychological renewal, and reintegrate into society, either in their new social status in liminal rituals or in original social status in liminoid rituals. The students graduate, the bride and groom become husband and wife, the sports or music fans take off their subcultural uniforms and return to everyday life until the next game or concert. After the BDSM scene, the arousal and endorphins fade, and the participants go through physical and emotional aftercare to ease the transition back into everyday life. The dominant may provide water, snacks, cuddling, or verbal reassurance to the submissive. At the end, they return to their original social roles. This transition is not always smooth, and sometimes, after intense scenes, participants experience “drop,” feelings of depression, just as other people experience disappointment at having to shift from the heightened reality of a holiday or another major life event to mundane routine.

The sadomasochistic scene is a temporary ritual of transgression in which people take a vacation from everyday life and experience a radically different existence. It functions on the same ritual principles as other secular rituals, such as a fraternity initiation or a university graduation, or the religious rituals of many faiths, such as a wedding or a Catholic mass. Ritual is both a temporary rebellion against mundane life and a supporter of it.

Cognitively, nothing underlines regularity so well as absurdity or paradox. Emotionally, nothing satisfies as much as extravagant or temporarily permitted illicit behavior. Rituals of status reversal accommodate both aspects. By making the low high, and the high low, they reaffirm the hierarchical principle. By making the low mimic (often to the point of caricature) the behavior of the high, and by restraining the initiatives of the proud, they underline the reasonableness of everyday culturally predictable behavior between the various estates of society.[27]

Sadomasochism is a ritual for the modern age.

Voluntary Suffering in Christianity

The distant ancestors of modern consensual sadomasochism can be found in Christianity’s own rituals of transgression and pain. Christianity has two conflicting ways of thinking about physical suffering: the penitential and the ascetic.

The first is the idea that physical punishment is a necessary means of disciplining a subordinate, be it a wife, slave, child, apprentice, or other underling. This is not just a self-serving means of ensuring that your orders are carried out. Physical discipline is supposed to be good for the subordinate, spiritually. This recurs all through Proverbs in the Bible: For example, “For whom the Lord loveth he correcteth; even as a father the son in whom you delighteth.”[28] “He that spareth his rod hateth his son: but he that loveth him chasteneth him betimes.”[29] “Thou shalt beat him with the rod, and shalt deliver his soul from hell.”[30]

Early Christians thought God was an awe-inspiring, even terrifying being, and the fear and pain one would feel in the presence of God meant one was even closer to the divine. This was the driving idea behind penitential self-flagellation, that one would punish oneself for one’s sins on behalf of the divine.

The second idea is attaining spiritual advancement by voluntarily accepting pain, in imitation of the Passion of Christ. This depends on the argument that Christ allowed himself to be beaten and crucified, and this must be spiritually significant. “Christ’s suffering merged with the suffering of the believer and removed or mitigated it.”[31] The image of Christ’s suffering body was a means to healing and transcendence. The word “ascetic” comes from the Greek word askein, meaning “work,” “to practice,” or “to train.” It is not merely suffering or the absence of comfort or pleasure, but an intentional undertaking. Thus Christianity adopted flagellation from other religions, just as it absorbed other pagan rituals and practices.

As explored earlier, intense physical sensations are a common method of achieving liminality. This opens the person experiencing them to altered states of consciousness, including sexual arousal. Niklaus Largier wrote in his history of flagellation:

If we could state any specific thesis that emerges from this overview of flagellation, it would be that voluntary flagellation and the texts that cover it are concerned not so much with “sexuality” (as all the sexual pathologists hold), but with the arousal of emotion and imagination.... Erotica and religious flagellation emerge as rituals that aim to unfetter desire, imagination, and the passions.[32]

Early Christian mystics struggled with the content of those unfettered passions. Saint Jerome, who lived as an ascetic in the desert for years, wrote, “Yet that same I, who for fear of hell condemned myself to such a prison, I the comrade of scorpions and wild beasts was there, watching the maidens in their dance ... and the Lord himself is witness, after many tears, and eyes that clung to heaven, I would sometimes seem to myself to be one with the angelic hosts.”[33]

As Christianity became a more established religion, rituals became more regulated. In the great monastic orders that began in the eleventh century, life was a never-ending ritual, a permanent state of liminality, in which monks and nuns segregated themselves from profane, everyday life and lived according to rules that regulated every aspect of conduct. This included flagellation and self-mortification.

Saint Peter Damian, an eleventh-century reforming monk, was so known for his extreme self-mortification that he is traditionally depicted holding a knotted cord (disciplina). Disciplina originally meant living under monastic rule, but it gradually shifted to the knotted cord as a symbol of religious discipline.

Peter was part of a postmillennial movement in Christendom that believed divine judgment was imminent, and the body had to be renewed through suffering to make it acceptable to God.[34] To live the austere life of a monk or hermit was a good start, but to be truly purified, one had to go further. Members of Peter’s monastic community wore iron bands next to their flesh, prayed with their arms extended in the form of a cross, and beat themselves with scourges.

Peter held up as example the hermit Dominic, known as Loricatus for the iron corselet and bands he wore. Peter described how Dominic completed nine psalters with flagellation in a day and a night, and “his whole appearance seemed to be so beaten with scourges and so covered with livid welts, as if he had been bruised like barley in a mortar.”[35] Dominic’s “whole life was for him a Good Friday crucifixion, but now with festive splendor he celebrates the eternal glory of the resurrection.”[36] In other words, Dominic’s life was a permanent state of ritual preparation for spiritual renewal.

Nuns could also practice mortification of the flesh, such as St. Rita of Cascia. In 1442, she prayed before an image of Christ, asking to participate in the pain caused by the Crown of Thorns. Reportedly, the image wounded her in the forehead, and the wound remained until her death.[37]

Lay worshipers also practiced flagellation and other mortifications. The Cistercian lay brother Arnulf was one such spiritual athlete. As an illiterate lay brother, Arnulf could not participate in most devotions, and compensated with elaborate discipline. He wore a hair shirt made of hedgehog pelts, with their quills inward. He self-flagellated, with a cane enhanced with quills or a scourge of thorny branches, while singing a vernacular song: “Got to be braver, got to be manly, manly I’ve got to be! Friends need it badly: this stroke for this one, that stroke for that one; take that in the name of God!”[38]

Arnulf also wrapped knotted ropes around his waist, supposedly so tight that his flesh began to rot. His biographer Goswin described this as purification from a feminine deity: “Oh, the happiness of this newborn child, for whom Mother Grace is so solicitous that she not only nourishes him with the sweetness of her milk but ... there in his infant cradle, she swaddles him in the bands of these piercing cords, and with so sharp a flint-knife, she circumcises away any lewdness in his flesh.”[39] Arnulf’s “manly” self-inflicted violence paradoxically returned him to infancy, an echo of the moment in the Passion when Mary cradles her dead son, all part of a ritual of spiritual renewal.

The ascetics created a feedback loop: the disease of the flawed, pleasure-seeking body is cured by physical punishment and denial, which produces more pleasure, which requires more punishment. This cycle continues until the ecstatic climax, follow by relaxation, which is only temporary.[40]

The Catholic hierarchy remained highly ambivalent about flagellation and other physical ordeals, particularly when performed by lay worshipers outside of church control. Flagellation as a method of correction was acceptable, even sanctioned by the monastic Rule of Benedict and the laws of the Church, as was asceticism as spiritual exercise. But the voluntary self-mortification advocated by Peter Damian was seen as an overly radical innovation. The clerics of Florence argued that “if it is sanctioned and observed, all the sacred canons will surely be destroyed, the precepts of the ancient fathers will disappear, and, as the Jew said, the traditions of our fathers will be reduced to nothing.” Peter Damian countered that flagellation was solidly grounded in Christian tradition, and the austerities of his followers were sanctioned by the lives of Christ, the apostles, and the early martyrs. He also critiqued the church’s hypocrisy for sanctioning flagellation as punishment but not as devotion.[41]

In the thirteenth century, during the years of plagues and famines, radical lay Christians took flagellation as a sacrament. The leaders of the movement, lay “masters” and “fathers,” claimed that God had written a heavenly letter threatening to destroy sinful humanity. The Virgin Mary interceded on man’s behalf to save those who joined a flagellant procession for thirty-three and one-half days, representing the span of Jesus’s life on Earth in years. Flagellants gathered into groups of fifty to five hundred members. The masters heard confession and granted absolution, and maintained strict discipline: no shaving, bathing, changing clothes, or interacting with women. People fed and lodged them as living saints. They gathered around churches to flog themselves with metal-tipped scourges, sing hymns, pray, and cry, while the master read aloud the alleged heavenly letter. Flagellants claimed that their suffering would absolve others, along with other supernatural powers such as exorcism and speaking with the Virgin Mary.

Here it was not only a question of a penitential gesture, but of a system of actions in which the salvation of the world would be attained through flagellation and through a radical likeness to Christ. Thus, every flagellant would work on the spectator like “a new Christ” and thereby actually change the entire population into an image of Christ.[42]

The earliest organized flagellant processions emerged in Italian cities in 1260, and spread to Hungary, the Low Countries, and France by the mid-fourteenth century.[43]

By 1348, the flagellant movement had grown too large to be ignored. In response to the plague reaching southern France, Pope Clement VI approved and instituted public mass flagellations in the streets of Avignon in which men and women participated.

By October 1349, however, the movement had grown too large to be tolerated. Not only were the flagellants an organized populist movement that threatened both clergy and aristocracy, they committed grave doctrinal errors. Flagellation was an accepted monastic practice, common among Franciscan clergy. For the lay worshipers to use it as a sacramental penance, however, threatened the Church’s monopoly on repentance. Clement VI issued a papal bull condemning the flagellants, ordering that their “masters of error” be arrested and burned if necessary. Clerical and secular authorities immediately forbade flagellant processions, punishable by excommunications and executions. Ironically, some members of the flagellant movements did penance by being beaten, by clerics instead of lay leaders, at St. Peter’s in Rome.[44] However, the pope’s ban explicitly excepted self-flagellation at home or elsewhere if not done in connection with heretic groups.[45]

Devotional manuals like Francis de Sales’s Introduction to the Devout Life (1609) deemphasized religious empathy with the suffering body of Christ or saints in favor of viewing saints as moral exemplars.[46] Officially, the path to ecstasy through personal bodily experience had been closed.

In practice, it survived in many scattered forms. Despite persecution by church and state, secretive flagellant groups cropped up intermittently for centuries. The last covert group of flagellants were executed in the 1480s.[47] The lay confraternities of Renaissance Bologna included flagellation as part of their ritual devotions, though these were indoor, carefully regulated, collective activities by people who hardly considered themselves revolutionaries.[48] In early modern France, flagellant lay worshipers organized into confraternities, which accepted men from all social classes. Women were accepted into some confraternities, but they did not flagellate themselves in public. Supposedly, women already had their burden of pain, from menstruation and childbirth, so they didn’t need additional self-inflicted pain.[49]

In the twenty-first century, lay members of the Catholic organization Opus Dei continue to practice mild forms of mortification of the flesh, such as fasting or wearing a cilice, a small version of the hair shirt, which has been reduced to a studded chain worn around the upper thigh.

Religious Art and Literature

Christians who could not or would not practice flagellation or other mortification could vicariously experience spiritual renewal by contemplating art.

Beginning in the thirteenth century, the Franciscans developed a complex system of iconography detailing the via crucis, the fourteen stages of the Cross, depicted in a wide variety of formats, from wall-covering paintings inside churches to handheld devotional booklets. Later artists interpolated even more scenes of the familiar story. Images of the Passion were a key part of public and private devotional practice, creating a link from human suffering to Christ’s suffering to the divine. The viewer suffered with Christ intimately, via imagining the same suffering, and experienced resurrection (spiritual renewal) in the same way.[50] Instead of being a mortal coil, the suffering body was the medium by which the believer knew God. The narrative of the Passion and Resurrection of Christ forms a ritual cycle of separation, liminality, and integration, and to read or see it is to vicariously experience the ritual. The image of the Passion was ubiquitous throughout Christian Europe and spread to the Americas in the colonial era centuries later.

While some artists depicted Christ with supernatural endurance, smiling and serene through his torments, other artists emphasized his human vulnerability, his mental and physical anguish, depicting him as the Man of Sorrows. Mathias Grünewald’s The Crucifixion (1500–1508) depicted Christ as dead, or as good as, his skin gray, his face anguished, his body contorted in agony, his five wounds visible in great detail.[51] Other artists literalized the connection between suffering Christ and viewer. Francisco Ribalta’s Saint Francis Embracing the Crucified Christ (c. 1620) showed Francis literally drinking blood from the wound in Christ’s side, while Christ placed the crown of thorns on his follower’s head.[52] Diego Velazquez’s Christ after the Flagellation Contemplated by the Christian Soul (c. 1630) showed Christ tied to the pillar with chords, just after his beating, with a winged angel guiding a child (representing the soul) to look at him; a ray of light reached from Christ’s head to the child’s heart.[53]

The Legenda aurea, or Golden Legend, is a collection of biographies of Christian saints, created in the late thirteenth century. It is full of stories of the martyrdom of saints: Laurence is roasted alive, Sebastian is pierced with arrows, Agatha’s breasts are severed, and others are stabbed, stoned, boiled, and decapitated. Such a book was used by preachers as a reference for sermons and readings on feast days. It became one of the most widely read and reproduced works of the period.

The manuscript of the Golden Legend kept in the Huntington Library is notable for its lavish illuminations, which contain many graphic images of violence. In fact, the imagery is far more violent than the text, which may only describe the saint’s torture briefly after telling of his or her acts of faith, good works, and miracles. For example, the text only says that St. Felicula was “tortured on the rack” after rejecting the sexual advances of a nobleman, but the illustration shows the martyr suspended from a rack, nude from the waist up with sharp combs being raked across her body and orange-red blood evident.

These images of violence and death had mnemonic functions, fixing each saint’s method of torture and/or death in the reader’s mind as a memory device. Thomas Aquinas wrote that “we are less able to remember things that have subtle and spiritual aspect, while those that are gross and sensible are able to be remembered.” A book like the Huntington Library’s Golden Legend would likely have been used for meditative personal devotion, not public display, with the graphic images intensifying the experience of contemplating these moral exemplars.[54]

The concepts of religious ordeal appeared in religious art for the masses as well, in scenes that have no basis in the Gospels or other scripture.

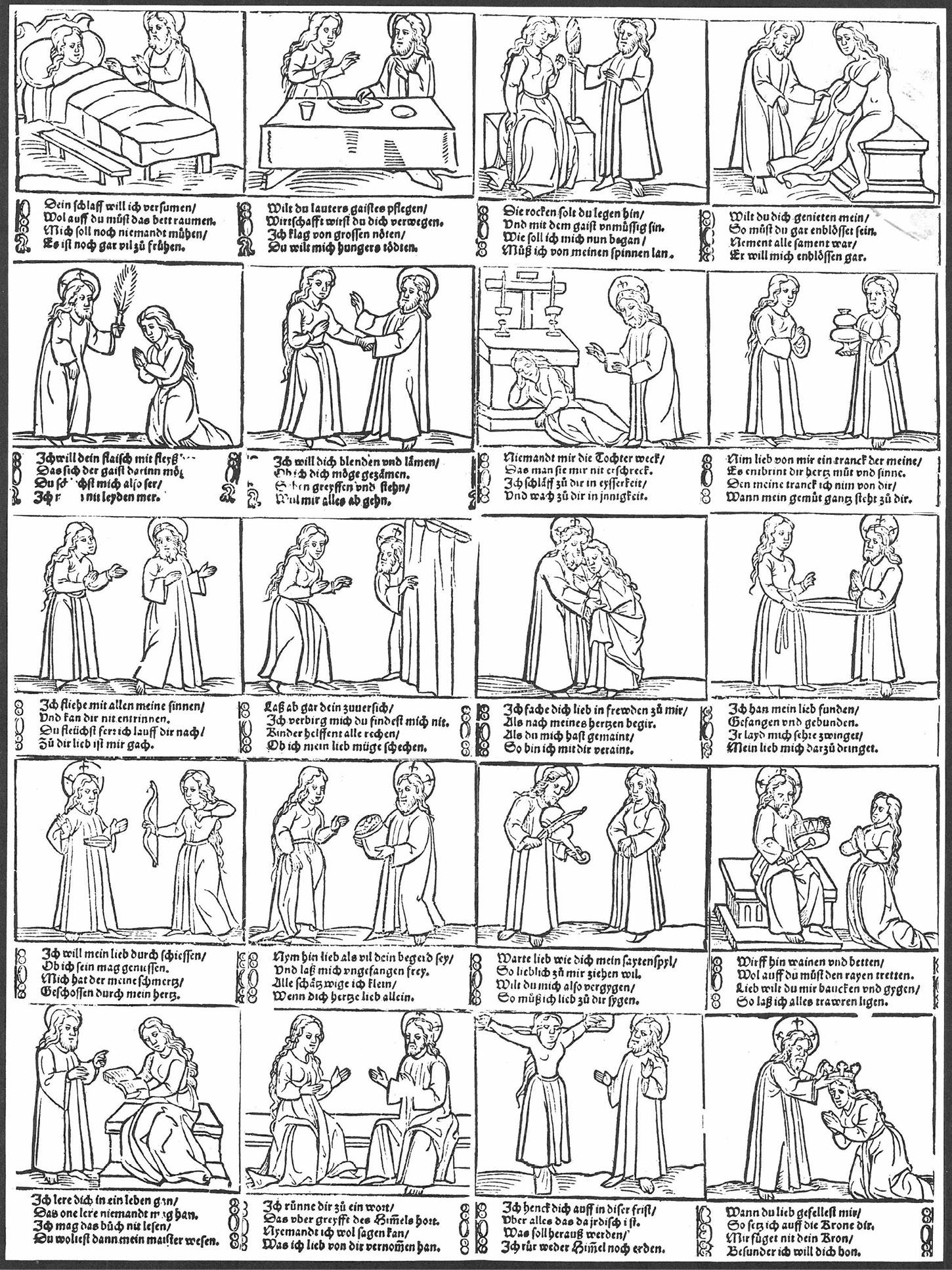

Courtesy David Kunzle Collection

“Jesus Courting the Christian Soul,” a broadsheet printed in German sometime between 1460 and 1480, shows the relationship between Jesus (a bearded man with a halo) and the Christian soul (a young woman) in terms that are not only sensual, but sadomasochistic (see Figure 1.3). Each of the twenty panels in this narrative contains a simple woodcut illustration and accompanying text, like an early comic strip.

Jesus wakes the Soul out of bed (panel 1), says she must forgo food (2) and other pursuits, symbolized by the distaff (3), and has her strip bare (4). The Soul complains: “I do not wish to be disturbed, it is too early yet.” “I suffer in dire necessity, you will starve me to death.” “Look at the way he wants to strip me bare.”

Jesus ramps things up in panels 5 and 6:

Jesus: “I shall castigate your flesh severely, to let the spirit thrive.”

Soul: “You are beating me so sorely, I cannot bear it anymore.”

Jesus: “I will blind and cripple you, so as to tame you.”

Soul: “I am unable to walk, stand or grasp.”

However, in panel 7, Jesus proves he’s a good dominant by looking after the Soul while she sleeps before an altar:

Jesus: “Let no-one waken the girl, lest she be frightened.”

Soul: “I go to sleep before you in outwardness, and awaken to you in inwardness.”

The relationship takes an unexpected turn when the Soul chases after Jesus (9) and finds where he is hiding (10). At first they are reconciled harmoniously (11), then the positions reverse. In 12, the Soul ties a cord around Jesus’s waist.

Soul: “I have found my love, caught him and bound him.”

Jesus: “Her pain overpowers me, my love forces me (to submit).”

In panel 13, she shoots arrows into Jesus.

Soul: “I shoot arrows at my love, so that I may enjoy him.”

Jesus: “The pains of love have pierced my heart.”

Jesus turns seductive again. He offers her gold, which she refuses out of love (14), then plies her with music (15, 16).

Jesus: “Stop your weeping and praying, come and join the dance.”

Soul: “Love, if you thus entice me with drum and fiddle, all my sorrow is gone.”

In panels 17 and 18, their bond is close again, with Jesus as teacher/dominant.

Jesus: “I’ll teach you to lead a life that no-one can have without my teaching.”

Soul: “I cannot read a book unless you are my master.”

Jesus: “I shall whisper a word to you that surpasses the treasure of heaven.”

Soul: “I will tell no-one, love, what I have heard from you.”

Finally, Jesus puts the Soul up on a cross, described in ecstatic terms.

Jesus: “I now hang you up over all earthly things during your temporal existence.”

Soul: “What will become of me, I touch neither heaven nor earth.”

The narrative ends with Jesus putting a crown on the Soul’s head, who refuses material reward.

Jesus: “Since you delight me, love, I set a crown upon you.”

Soul: “I do not deserve a crown, I want to have just you.”

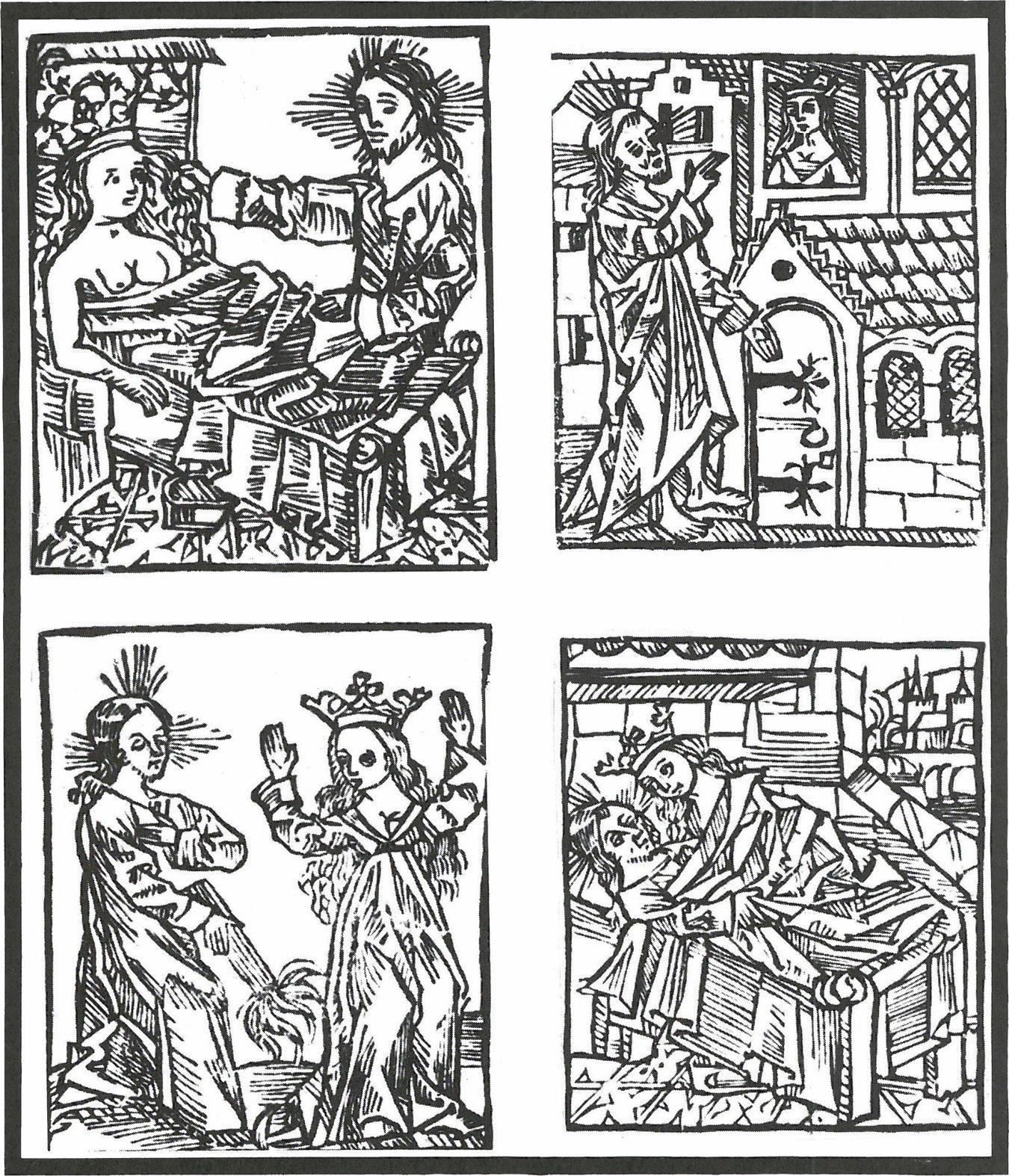

Courtesy David Kunzle Collection

This was one example of this genre of broadsheet stories. Another four-panel story, dated about 1500 CE, was titled “Of the Innermost Soul, How God Chastises Her and Makes Her Suited to Him” (see Figure 1.4). Jesus wakes the Soul from slumber, by pulling her out of bed by her hair. Persistently, he stands out in the rain and knocks on her door. In the third panel, he lights her clothes on fire with a candle. Finally, they are shown in bed together, face-to-face. “How they lie in bed together ... and attain eternal rest.” Again, the narrative follows Jesus waking a young woman out of bed, being resisted by her in her own stubbornness and pride, overwhelming her with his own forcefulness, and finally their erotic union. In another example of this genre, Jesus awakens the sleeping woman by setting her bed on fire.

The broadsheet’s story was a ritual in written form, depicting the relationship between humanity and God as an initiation, expressed in physical terms of giving and receiving pain and pleasure, commands, and confinement. The soul is liberated and blessed via ritualized submission and suffering at the hands of a higher power, an idea that had entered the mass consciousness of the Christian world, even as authorities condemned it. What had been banned from religion survived in other forms.

Chapter Two: The Pornography of the Puritan

If pain and suffering were once sacred, when and how did that change? And how did eroticism become attached to those concepts? Christianity has always had a complicated and conflicted relationship with the body and bodily experience, and in the early Modern era, physical ordeal rituals were slowly but steadily pushed out of the sacred and into the profane.

Council of Trent

In 1563, the twenty-fifth session of the Council of Trent declared:

Moreover, in the invocation of saints, the veneration of relics, and the sacred use of images, every superstition shall be removed, all filthy lucre be abolished; finally, all lasciviousness be avoided; in such wise that figures shall not be painted or adorned with a beauty exciting to lust; nor the celebration of the saints, and the visitation of relics be by any perverted into revellings and drunkenness; as if festivals are celebrated to the honour of the saints by luxury and wantonness.[55]

The imagery had not changed. What had changed was people’s perception of them. People could no longer not see sexuality in what had once been only images of religious ecstasy.

For example, Saint Teresa of Ávila, a sixteenth-century Carmelite reformer and nun, practiced intense mortification of the flesh and claimed to have experienced a violent encounter with an angel, her “transverberation,” which she described thus:

I saw in his hand a long spear of gold, and at the iron’s point there seemed to be a little fire. He appeared to me to be thrusting it at times into my heart, and to pierce my very entrails; when he drew it out, he seemed to draw them out also, and to leave me all on fire with a great love of God. The pain was so great, that it made me moan; and yet so surpassing was the sweetness of this excessive pain, that I could not wish to be rid of it. The soul is satisfied now with nothing less than God. The pain is not bodily, but spiritual; though the body has its share in it. It is a caressing of love so sweet which now takes place between the soul and God, that I pray God of His goodness to make him experience it who may think that I am lying.[56]

From a modern, post-Freudian perspective, St. Teresa’s account sounds obviously sexual. Religious ecstasy is merely a cover story for an escape of repressed sexuality; the soul is just a metaphor for the body. The metaphor cuts both ways, however, and St. Teresa could be read as a spiritual experience expressed in terms of physical violation.

St. Teresa’s divine encounter was depicted by Gian Lorenzo Bernini in his sculpture Ecstasy of Saint Teresa (completed 1652), which shows the nun swooning while the angel stands over her with a spear. In the life-size sculpture, Teresa’s face is young and beautiful, her garment is soft and flowing, and one shapely bare foot dangles in plain view. Even in Bernini’s own time, an anonymous reviewer of the newly unveiled work wrote that it “dragged that most pure Virgin down to the ground ... transforming her into a Venus who was not only prostrate, but prostituted as well.”[57]

Religious leaders were concerned about the confusion of the erotic with the holy, the sacred with the profane. The fifteenth-century Italian preacher Bernardino of Siena wrote, “I know of a person who, while contemplating the humanity of Christ suspended on the cross (I am ashamed to say and it is terrible even to imagine) sensually and repulsively polluted and defiled themselves.”[58] In 1402, Jean Gerson, bishop of Paris, complained of “the filthy corruption of boys and adolescents by shameful and nude pictures offered for sale at the very temples and sacred places.”[59]

In an earlier time in Christian Europe, phenomena like St. Teresa’s ecstasy, and any depiction of it, would have been accepted as sacred without question, universally. By the sixteenth century, the medieval worldview was no longer universal, and religious views of the body and mystical experience were being challenged by the new rationalist, materialist philosophies. For many viewers, St. Teresa was profane, not sacred. Experiencing pain was no longer an expression of piety, but of physical indulgence or insanity. The Vatican’s gradual shift in emphasis to saints as moral exemplars, rather than holy figures in themselves, also moved worship away from the idea that the human body could be a medium to divinity.[60]

Over centuries, the Church’s power to define human experience gradually eroded. By the time of Bernini and his anonymous critic, there were other ways of understanding the body and its physical experiences, which studied the material, natural world as an explanation for human experience. Flagellation and other forms of asceticism were no longer a way of communicating with the divine, but expressions of internal desires.

Academic

Perhaps the earliest discussion of voluntary flagellation in secular, material terms came in 1503, in an astrology treatise published by Pico della Mirandola,[61] which included a prototype of a case history of a sexual masochist.

There is now, says he, a Man of a prodigious, and almost unheard of kind of Lechery: For he is never inflamed to Pleasure, but when he is whipt; and yet he is so intent on the Act, and logs for the Strokes with such an Earnestness, that he blames the Flogger that uses him gently, and is never thoroughly Master of his Wishes unless the Blood starts, and the Whip rages smartly o’er the wicked Limbs of the Monster. This Creature begs this Favour of the Woman he is to enjoy, brings her a Rod himself, soak’d and harden’d in Vinegar a Day before for the same Purpose, and intreats the Blessing of a Whipping from the Harlot on his Knees; and the more smartly he is whipt, he rages the more eagerly, and goes the same Pace both to Pleasure and Pain. A singular Instance of one who finds a Delight in the Midst of Torment; and he is not a Man very vicious in other Respects, he acknowledges his Distemper, and abhors it.[62]

When I seriously enquir’d of him the Cause of this uncommon Plague, his Reply was, I have used my self to it from a Boy. And upon repeating the Question to him, he added, That he was educated with a Number of wicked Boys, who set up this Trade of Whipping among themselves, and purchased of each other these infamous stripes at the expence of their Modesty.[63]

The “childhood experience” explanation of sexual masochism proved popular and was referenced by other sixteenth-century writers. This is not to say that the man Pico discussed was the first sexual masochist in human history, but that this is one of the earliest discussions of such behavior in terms of individual psychology.

Shakespeare’s play Measure for Measure (first performed circa 1604) criticized religious asceticism and flagellation by linking it with deviant sexuality and political tyranny. The Duke of Vienna, the judge Angelo, and the novice nun Isabella claim to be pious and chaste, while their repressed sexuality emerges as voyeurism, sadism, or masochism, respectively. “By drawing parallels to historical or topical events, Shakespeare suggests that the protagonists’ very asceticism, ironically, causes these deviant desires and that they associate their austere religious practices with pleasurable feelings.”[64]

The plot revolves around a couple, Claudio and Juliet, who have not properly observed all the rules of engagement and marriage. The judge Angelo decides to make an example of Claudio and condemn him to death for unlawful fornication. Claudio’s friend Lucio asks Isabella, a novice nun and Claudio’s sister, for help. Angelo offers to free Claudio in exchange for sex with Isabella.

The trio of the Duke, Angelo, and Isabella are all ascetics (though none are actually clergy), and are hostile to sexual desires, believing that “pain kills the libido and thus subjecting themselves and others to physical abuse.”[65] Shakespeare used puns and allusions to characterize Angelo as a flagellant by comparing him to stockfishes,[66] which were cured by drying and beating with clubs, and mentioning his attempt to “rebate and blunt his natural edge,”[67] with “rebate” suggesting “to beat out.” Both Angelo and Isabella speak of sexuality in terms of plunder and violence, of men victimizing women. Lucio claims Angelo “puts transgression to’t,” not only punishing harshly but deriving perverse pleasure from the act, and “put to” can also mean engage in sexual intercourse.[68]

Shakespeare alluded to the nuns’ sexual restraints and their restricted interaction with men, but Isabella finds that insufficient for her: “And have you nuns no farther privileges?,” she asks.[69] This repression cannot destroy the libido, but only makes it express in perverse ways. “Actual intercourse being forbidden, they develop a sexuality based primarily on fantasy, a cerebral kind of satisfaction, in which they savor the writhing of victims who fearfully wait for the blow from their persecutor.”[70]

Throughout the play, characters claim the highest motives when they are actually indulging their perverse sexuality. Even Lucio plays on Isabella’s masochism to persuade her to plead with Angelo, using the language of seduction, rather than her love of her sibling. Eager to cast herself into the role of supplicating victim before a cruel man, Isabella agrees. Angelo offers to free Claudio in exchange for Isabella’s sexual submission, expressed in the terms of horse riding with references to “now I give my sensual race the rein: / Fit thy consent to my sharp appetite.”[71] Isabella’s response reveals her masochistic desires, even as she refuses him:

Th’ impression of keen whips I’d wear as rubies,

And strip myself to death as to a bed

That longing have been sick for, ere I’d yield

My body up to shame.[72]

Shakespeare’s play was a scathing indictment of the upper-class ideals of religious asceticism, demonstrating that expressions of piety mask personal indulgences, and repressed sexuality only fosters sadism and masochism, which leads to injustice. Such a criticism would have been scandalous at an earlier time, but by the early seventeenth century was unavoidable.

The next major treatise to consider the voluntary experience of pain from a secular perspective came from German doctor Johann Heinrich Meibom (1590–1655), in his treatise De flagorum usu in re veneria et lumborum renumque officio (1629).

Meibom (also Latinized as “Meibomius”) disagreed with Pico della Mirandola’s environmental explanation for erotic flagellation, and proposed a physiological explanation. He thought that certain men, particularly the aged, were “colder” than normal, and required more intense stimulus to achieve erection and orgasm.

I further conclude, that Strokes upon the Back and Loins, as Parts appropriated for the Generating of the Seed, and carrying it to the Genitals, warm and inflame those Parts, and contribute very much to the irritation of Lechery. From all which, it is no wonder that such shameless Wretches, Victims of a detested Appetite, such as we have mention’d, or others exhausted by too frequent a Repetition, the Loins and their Vessels being drain’d have sought for a Remedy by FLOGGING. For ’tis very probably, that the refrigerated Parts grow warm by such Stripes, and excite a Heat in the Seminal Matter, and that more particularly from the Pain of the flogg’d Parts, which is the Reason that the Blood and Spirits are attracted in a greater Quantity, ’till the Heat is communicated to the Organs of Generation, and the perverse and frenzical Appetite is satisfied, and Nature, tho’ unwilling drawn beyond the Stretch of her common Power, to the Commission of such an abominable Crime.[73]

Meibom’s ideas on the physiology of flagellation were still referenced well into the nineteenth century.

The Abbe Jacques Boileau’s book Historia flagellantium (1700) accused flagellants of perversion, madness, shamelessness, and superstition. In his earlier works, he also railed against low-cut dresses on women for inflaming sensuality and libertinage. Boileau was anti-Jesuit, claiming there was no scriptural basis for flagellation, which was pagan in origin, and therefore had no place in Christian practice.

He distinguished between sursum disciplina, applied to the bare shoulders, and dorsum disciplina, applied to the bare buttocks and thighs. The latter is particularly dangerous, Boileau said, because of the physical connection between the loins, buttocks, and pubis. As a result from flagellation on the buttocks, “the animal spirits are forced back violently towards the os pubis and that they excite lascivious movements on account of the proximity of the genitals.”[74] Boileau cites examples from both Pico della Mirandola and Meibom to support this.

Three years later, Jean-Baptiste Thiers, a doctor of theology, published a rebuttal, arguing that flagellation was practiced in the early church and it was a valid practice in his time, as an imitation of Christ. Thiers did not disprove Meibom’s theory, as presented by Boileau, and was conspicuously silent about the sexual implications of “lower discipline.”[75] The debate between Thiers and Boileau shows that the field was tilted against Thiers, who could not contradict Boileau’s argument.

Boileau’s better-known brother, the poet Nicolas Boileau Despréaux, contributed a satirical verse on this paradox, which translated read, “Which, under the pretence of extinguishing our voluptuousness, by that very austerity and by penance knows how to ignite the flame of lubricity.”[76]

The debate was continued by other scholars and clergy in France, Germany, and England in later centuries, with citations in debates over school beatings, where advocates of the rod denied any sexual aspect to beating. Flagellation became a point of contention between Catholics and Protestants, and clergy and the laity. It was a metonym for what Enlightenment thinkers and Protestants saw as the corrupt and perverse Catholic Church.

Anti-Catholicism

There’s a long tradition of linking deviant sexuality with deviant politics, a historical habit that will recur many times in the future. Sexualized anti-Catholic propaganda goes back at least as far as Boccaccio’s Decameron, a collection of allegorical stories from the mid-fourteenth century, which included lecherous clerics and randy nuns. The word “pervert” itself could refer to both religious and sexual deviance, and it wasn’t until the late nineteenth century that it had a mainly sexual definition.

It was during the “long eighteenth century” (usually defined as running from the English Glorious Revolution of 1688 to the battle of Waterloo in 1815) that the anticlerical propaganda that used sexual deviance gradually shaded into pornography that used the trappings of Catholicism as costumes, props, and sets. It’s impossible to identify any dividing line between the two.