Syracuse University, Syracuse, New York 13244-1170 pparnold@syr.edu

Philip P. Arnold

Comments on the Appearance of the Journal for the Study of Religion, Nature and Culture

Abstract

In Native American religions there has been a shift from expert knowledge to collaborative knowledge—working with indigenous communities on issues of urgent mutual concern. Most urgent are environmental issues. This article explores collaborative relationships with the Onondaga Nation, near Syracuse New York, the Central Fire of the Haudenosaunee (‘People of the Longhouse’ Six Nations Iroquois) Confederacy. The Onondaga Nation is still organized and run according to the ancient ceremonial process—the Great Law of Peace. Because of their strong traditional orientation they have led international efforts for the recognition of indigenous people at the United Nations. Leaders like Oren Lyons and Audrey Shenandoah have brought their message of peace and environmental justice to the world. On 11 March 2005 they filed their ‘Land Rights Action’. Native and non-native have been inspired by this action and several collaborative events have resulted from this bold and principled stand on behalf of the environment.

It would be difficult to overestimate the importance of the appearance of this journal at this time. An environmental crisis of enormous proportions looms large over all aspects of our lives. The news is filled with stories about global warming and its consequences, such as stronger and more active hurricanes, tornados, drought, flooding, species extinction, insect migrations, and the rise of viral infections, just to name a few. More and more people, even in the United States, are beginning to appreciate the full scope of our inability to interact appropriately with the natural world. The questions that arise are: ‘How have we found ourselves in such a fix?’ and ‘What should be my appropriate response to such dire predictions?’. I have found that more people are looking for alternatives to American culture by turning to indigenous people. Living and teaching in upstate New York, in Onondaga Nation Territory, has transformed the way I do my scholarship and teaching. I have found it necessary to turn away from an ‘expert’ understanding of knowledge production that has organized the university, to a ‘collaborative’ one. This move to cross-cultural collaboration connects my field of the history of religions with the urgency of environmental concerns. It makes teaching ‘Native American Religions’ and ‘Indigenous Religions’, for me and my students, of vital importance.

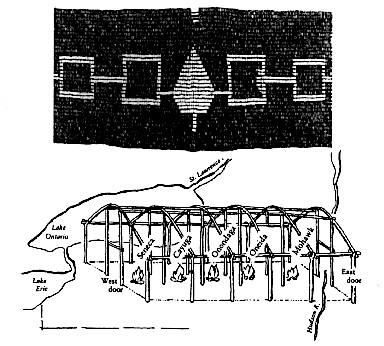

My wife, Sandy Bigtree (who is Mohawk from St Regis) grew up in Syracuse, and in 1996 we moved here with our twin boys, to the heart of Haudenosaunee country. This move changed everything. Being in Syracuse has transformed my work because my physical location now allows me better to reflect on my cultural location with a greater sense of urgency. The Haudenosaunee translates as ‘People of the Longhouse’, or ‘People Building a Longhouse’. They are more generally known as the ‘Six Nations Iroquois Confederacy’. Above is an image of the ‘Confederacy Belt’, or ‘Hiawantha Belt’, which is an ancient belt made of wampum (a worked shell bead of purple and white from the quoahog shell found along the Atlantic seaboard from Cape Cod to Long Island). From left to right, the symbols represent the Seneca, Cayuga, Onondaga (as a Great Tree of Peace), Oneida, and Mohawk Nations.[1] Underneath the Hiawantha Belt is a depiction of a Longhouse that extends across upstate New York, with five fires, representative of the five original nations in the Confederacy. The Hiawantha Belt was repatriated to the Haudenosaunee in the early 1980s from a museum of anthropology at SUNY-Albany. Since then it has become the flag of the Haudenosaunee and can be seen displayed prominently by Haudenosaunee people throughout the Central New York region.

Syracuse University is located five miles north of the Onondaga Nation. As the Hiawantha Belt indicates, Onondaga is the Central Fire of the Haudenosaunee and where the Confederacy was founded on the shore of Onondaga Lake. Three men joined together at Onondaga Lake and convinced the Haudenosaunee to dedicate themselves to the Great Law of Peace by throwing their weapons of war into the roots of the Great Tree of Peace.[2] Of the 563 tribal entities recognized by the United States federal government today, only three are still governed by their ancient ceremonial systems. All three are Haudenosaunee, and one of these is the Onondaga Nation. Onondaga territory is still controlled by the Longhouse system of government. All Longhouse people at the Onondaga Nation hold their clan through their mother. Male chiefs are ‘raised’ through their matrilineal clans by clan-mothers. The Haudenosaunee system of governance impressed and influenced the ‘Founding Fathers’ of the United States constitution and also women in the 1840s at Seneca Falls, who were the impetus for the women’s movement in the United States.

On 11 March 2005, the Onondaga Nation filed its historic ‘Land Rights’ action in federal court. In some ways this legal action was not new. Various Haudenosaunee nations have also filed ‘land-claims’ throughout upstate New York, including the Mohawk, Seneca, Cayuga, and Oneida. Since the mid-1970s ‘Indian land-claims’ have come to dominate local media attention, if not the attention of national and international media. There has been an intensely negative reaction among non-native residents of New York to these actions. Nothing in American culture raises controversy faster than contestation of land title. But the Onondaga legal action is completely unique. It is based in the traditional values of the Longhouse tradition—values of peace, justice, environmental healing of the land—and particularly Onondaga Lake, which is simultaneously the site of the indigenous root of democracy and the most polluted lake in the United States. Although the Onondaga action is based in the same legal history as the actions of other Haudenosaunee nations, it is fundamentally different. Rather than a monetary settlement, or one that includes a casino deal with the state, the Onondaga Nation seeks to restore the integrity of the environment: it seeks to restore Creation to a pristine state—hence the emphasis on ‘land-rights’ as oppose to ‘landclaims’.[3] Because of the strong values of environmental healing, several non-Haudenosaunee people, including myself, have become motivated to promote the Onondaga Land Rights action. Neighbors of the Onondaga Nation (NOON) is an organization that has grown among residents of the greater Syracuse area to inform local non-native groups about the positive aspects of this legal action for this region. Various institutions like the Syracuse Peace Council, SUNY-College of Environmental Science and Forestry, and Syracuse University, with the support of Chancellor Nancy Cantor, have combined forces to hold a year-long educational series titled ‘Onondaga Land Rights and Our Common Future’. Several other events have been planned for the near future that bring together environmental issues, global politics, social justice and cultural identity around matters of ‘religion’.

(NOON [www.peacecouncil.net/NOON/index.htm])

In my experience in the academy, these kinds of ongoing collaborations between native and non-natives are unprecedented. In many ways it has to do with our living and working in Onondaga Nation territory and the Nation’s bold and principled stance on behalf of environmental healing. In some respects this is connected with the leadership at Syracuse University and SUNY-College of Environmental Science and Forestry. In other respects these events are made possible by the many citizens of upstate New York who tenaciously hold and work for the things in which they believe. Whatever the reasons, living and working in central New York makes teaching ‘Native American religions’ more urgent and controversial, but at the same time more satisfying. Working in this area has changed the way I think about teaching and doing academic work. My training as a historian of religion, however, aids greatly in helping to interpret these new methodological moves, and at the same time it transforms the ways I think about the discipline. One example will make my point here.

Over the last few generations, anthropologists of religion and others working to refine the descriptive task of the history of religions have been vexed about how to do their work. At least since Edward Said’s work on ‘Orientalism’ forty years ago, questions about how the scholar of religion can adequately describe ‘the other’ without interrupting or destroying them are among the most pressing methodological discussions in our field. Likewise, in the history of religions the methodological issues have become even more perplexing when dealing with the contentious nature of ‘religion’ itself. One of the first things that Onondaga people tell my classes, for example, is that they have no word or concept of ‘religion’.

The shift from an expert model of knowledge production to a collaborative model goes some way toward solving this methodological quandary. Rather than my asking questions about what the Onondaga believe, or what ceremonies they perform, which will always be regarded suspiciously, instead I ask myself, and them: What are the issues of most urgent mutual concern? For one thing this requires of me an ability to interpret my own urgent questions—what do I want to know?—and then find answers through a collaborative process of discussion and action. No longer are the Haudenosaunee, nor the Aztec, nor the Lakota, my ‘informants’. Instead they are my collaborators in generating new ways of communicating solutions to urgent issues. This may sound to some in the academy like I am shirking my academic responsibility in producing objective, unbiased knowledge. But I now realize that generating collaborations, like colleagues, has been one of the primary motivations in my academic work. It is a natural extension of what I regard as the work of the history of religions.

I am fortunate to be teaching ‘Native American religions’ in Onondaga Territory. Our graduate students in the Department of Religion gain another perspective on the topic and on the history of religions, whether their primary area of interest is in postmodern theology, Buddhism, religion and popular culture, or Indigenous religions. Undergraduates, whether they are native or non-native, greatly benefit from a collaborative orientation. One consequence is the development of new courses like ‘Religion and Sports’ (which emphasizes the roots of lacrosse in Haudenosaunee culture), ‘Religious Dimensions of Whiteness’, ‘Religion and the Conquest of America’, and ‘Religion and American Consumerism’. These are cultural phenomena best explored together. The history of these mythic landscapes is traumatic but I find that students almost always benefit from these explorations. These classes are particularly effective because we all live and work in central New York.

References

Mann, Barbara, and Jerry L. Fields

1997 ‘A Sign in the Sky: Dating the League of the Haudenosaunee’, American Indian Culture and Research Journal 21.2: 105-63.

[1] The Tuscarora Nation became the sixth to join the Haudenosaunee in the 1720s when they came north from South Carolina to escape the slave traders and aggressive appropriations of their lands by European settlers.

[2] Dating the origins of the Haudenosaunee Confederacy is a matter of scholarly debate. The best estimate, however, is 1142 CE (Mann and Fields 1997).

[3] The preamble of the legal action states these values clearly. As it says, ‘The Onondaga people wish to bring about a healing between themselves and all others who live in this region that has been the homeland of the Onondaga Nation since the dawn of time. The Nation and its people have a unique spiritual, cultural, and historic relationship with the land, which is embodied in Gayanashagowa, the Great Law of Peace. This relationship goes far beyond federal and state legal concepts of ownership, possession, or other legal rights. The people are one with the land and consider themselves stewards of it. It is the duty of the Nation’s leaders to work for a healing of this land, to protect it, and to pass it on to future generations. The Onondaga Nation brings this action on behalf of its people in the hope that it may hasten the process of reconciliation and bring lasting justice, peace, and respect among all who inhabit this area’ (Onondaga Nation vs. New York State, Civil Action No. 05-CV-314).