Alan Barnard

Primitive communism and mutual aid

Kropotkin visits the Bushmen

Authority and Sharing Among the Bushmen

Communism, Capitalism, and ‘acculturated Bushmen’

Primitive Communism and the Foraging Ethos

But still we know that when the Europeans came, the Bushmen lived in small tribes (or clans), sometimes federated together; that they used to hunt in common, and divided the spoil without quarrelling; that they never abandoned their wounded, and displayed strong affection to their comrades.

Peter Kropotkin (1987a [1902]:83)

Concepts such as ‘anarchist’, ‘communist’, ‘socialist’, and even ‘Bushman’, are artificially constructed. This does not mean that they have no meaning. On the contrary, it means that their meanings are contingent on the anthropological and sometimes the political perspectives of the commentators. Each ethnographer’s understanding of the ‘Bushmen’ is mediated through a desire to represent them within a larger theory of society.

For the last seventy years or so, ‘primitive communism’ has erroneously been equated with either ‘revolutionary communism’ or ‘Marxism’. My intention in this chapter is to provide an alternative, very much non-Marxist view of primitive communism—namely that of Peter Kropotkin, anarchist Russian prince, geographer, and an early mentor of A.R. Radcliffe-Brown. Whereas Marx and Engels perceived history as a sequence of stages, Kropotkin saw it in terms of a continuity of fundamental human goodness. His own contribution on ‘Anarchism’ in the eleventh edition of the Encyclopaedia Britannica (1910; reprinted in Kropotkin 1987c: 7—22) is a classic summary of the historical setting for his social theory. After hearing a lecture entitled ‘On the law of mutual aid’ by the Russian zoologist Karl Fredorovich Kessler in 1880, and reading The Descent of Man (Darwin 1871) in 1883, Kropotkin resolved to put forward his own version of Darwinism (Kropotkin 1987a:13—14; see also 1988a [1899]:298—301). The result was Mutual Aid (Kropotkin 1987a [1902]). This was conceived as an answer to the Social Darwinists, who saw in nature a mutual struggle which validated the aims of capitalism.

Among other noteworthy writings are Kropotkin’s influential comments on ‘Anarchist Communism’ (1987b [1887]) and The state’ (1987d [1897]). The former was originally published in The Nineteenth Century as two separate articles—‘The scientific bases of anarchy’ and ‘The coming anarchy’. The titles are revealing, for they reflect Kropotkin’s twin concerns: the theoretical understanding of society, and the practical solution to its problems. The practical solution was much the simpler aspect, as abolition of the state was seen as the easy answer. The state, in its turn, was a problematic concept. For many, including some anarchists in Kropotkin’s day, the state and society were synonymous. Yet Kropotkin (for example, 1987d [1897]:9—16) argued strongly against this assumption. For Kropotkin, society predates the state, and his notion includes both animal societies and human, ‘primitive communist’ societies.

Authority and Sharing Among the Bushmen

Two specific concerns in Bushman ethnography have been the degree of authority in the hands of leaders, and the extent of sharing as a mechanism for redistributing wealth and preventing the development of a social hierarchy.

Among the earliest true ethnographers of Bushmen was Dorothea Bleek. In 1920 and 1921 she conducted field research with the Nharo (whom she called Naron) and the Southern !Kung or •Au//eisi (Auen), who lived along the Bechuanaland-South West Africa border. Her comments are interesting because she implies a change, in the time not long before her fieldwork, from hierarchical to egalitarian organization among those she classified as Northern and Central Bushmen.

Both Naron [Central Bushmen] and Auen [Northern Bushmen] had chiefs when the old men were young. The middle-aged men just remember them.... Among Southern Bushmen there were no chiefs and they had no name for chieftainship.. There are no class distinctions among Naron and Auen, nor, excepting the medicine men, are there any trades.

(Bleek 1928:36, 37)

Contrast this statement with the comments of a more recent ethnographer George Silberbauer on the G/wi, a Central group who live east of the Nharo in what became (at Silberbauer’s own instigation) the Central Kalahari Game Reserve of Botswana:

There are no chiefs or headmen and every adult member of the band has rights equal to those of all the other members who reside in the band’s territory.... In the regulation of the band’s affairs, none has any more authority than any other by reason of superior status and, except for the obligations within his or her kinship group toward senior kin., no man or woman yields to the superior authority of any other member.

(Silberbauer 1965:73)

Silberbauer, like most of his contemporaries, has emphasized the lack of hierarchy. Elsewhere (1982:31, 34), he proposes consensus as the basis of Bushman political power. Power, he suggests, lies not in the ability of individuals to force a consensus, but in their perceiving the mood of the band and compromising and creating opportunities to have their goals realized when the time is appropriate.

Has Bushman social organization really changed, or has its perception, by Bushmen themselves or by Europeans, changed? Is there really a north/south difference in this issue, as Bleek’s statement suggests, or is the difference dependent on the respective insights of northern and southern ethnographers? In my view, when Bleek argued that there were chiefs in the past, even placing the statement in the mouths of her Bushman informants, she was trying to counter potential claims arising from the descriptions of Bushmen common in her day. Kropotkin’s (1987a [1902]: 83—4) understanding of the Bushmen hails from the same writings known to Bleek.[1] Yet he perceived them as representatives of a primitive communist and not a hierarchical social structure. He also perceived Bushman society as in a state of decline from its high degree of mutual aid, a point I shall return to later.

Bushman society is commonly characterized in late twentieth-century sources as being based on sharing. These statements by Tanaka, on the G//ana and G/wi, and Marshall, on the Zu/’hoa^si or Central !Kung, are typical.

The integrating and governing principles of egalitarian San society are the principles of sharing and cooperation.. For outsiders, the San ideology of equal sharing is very difficult to comprehend, and its practice is even more difficult. It was this point that gave me the most trouble when I began living among the San.

(Tanaka 1980:95–6)

They lived in a kind of material plenty.... They borrow what they do not own. With this ease, they have not hoarded, and the accumulation of objects has not become associated with status.

(Marshall 1961:243–4)

Sahlins (1974:9–10) quotes this last passage, from Marshall’s ‘Sharing, talking, and giving’ (1961), as a keynote to his theory of the ‘original affluent society’. In reprints of her paper, Marshall has amended the last sentence to read: ‘I believe that for these reasons they have not developed permanent storage, have not hoarded, and the accumulation of objects has not become associated with admirable status’ (for example, 1976:308–9). In the original version she goes on to say: ‘they mitigate jealousy and envy, to which they are prone, by passing things on to others’ (1961:244). In the later versions, she specifies: ‘by passing on to others objects that might be coveted’ (1976: 309). Although 1 doubt whether these alterations mark any significant changes in Marshall’s thinking, much less any transformations in !Kung society itself, they nevertheless display subtle changes in emphasis, first with reference to storage, and secondly with reference to the reasons why an individual might want to pass objects on to others. In mentioning storage, Marshall in fact amplifies Sahlins’ theory, which, of course, is built on her own ethnography. In mentioning coveting, she not only clarifies her original statement but also gives emphasis to the point, made in the meantime by Lee (for instance, 1965 passim; cf. Lee 1979:370–400; Draper 1978), that ! Kung society is fraught with dispute and violence.

Marshall’s addition on coveting is a far cry from Sahlins’ reading of her original statement, or from Tanaka’s, which gives emphasis to sharing in its positive sense by coupling it with cooperation. ‘Sharing’ is an emotive word, and one must be careful not to misconstrue its ethnographic meanings. Marshall’s amplified description has grown simultaneously towards and away from that of Sahlins, while Tanaka here has picked up on only one aspect of her discussion—one which concerned him especially in his role as fieldworker. It is perhaps worth further reflection that the groups studied by Tanaka—the G//ana and the G/wi (Central Kalahari Bushmen)—lack any notion of formalized, delayed-reciprocal giving on non-consumable property. Their ‘sharing’ is less formal than that found among the !Kung.

According to Schapera (1930:147): ‘The economic life of the [Bushman] band, although in effect it approaches a sort of communism, is really based on a notion of private property.’ He does go on to point out that land is held in common ownership, but movable property is individually owned, as are meat, vegetable food, and water (1930:147— 9). Lee (1979:333—400) places particular emphasis on relations of production as determinants of !Kung politics. Although they do have words to express notions of leadership and authority (for example, kx’au n!a, headman or ‘great owner’), !Kung have no formal political structures. Rights to land and resources are inherited bilaterally, and kinship bonds provide a framework for both production and political organization. The core group of kinsmen within each band are known as the kx’ausi (owners) of the n!ore (band territory). Membership of the core group, seniority of residence, age, and personal qualities are all factors in ascribed leadership, but boastfulness and attempts to dominate are strongly discouraged.

Virtually all Bushman groups possess systems of universal kin categorization (Barnard 1978; 1981). This ideology of classifying everyone as a member of some kin category affords them the mechanism for distributing both movable property and rights over natural resources (cf. Keenan 1981: 16—18). Other forms of social classification, either kinship based or non-kinship based, define the social limits of particular arenas of distribution. Marshall (for instance, 1976:156—312) emphasizes the significance of both kinship and sharing for maintaining cooperation within the band, and between bands. In particular, !Kung society is characterized by strict rules of meat-sharing. Hunters lend arrows to one another, and the ‘owner’ of the kill is the owner of the killing arrow even though it will have been shot by another hunter. The owner shares his meat with the other hunters, with his affines, with the members of his band, and often with members of other, nearby bands too. Those who receive meat then distribute it to their families, to name relatives, and to others.

Some twenty years after Marshall’s field work, Wiessner took up in more detail the problem of the formalized giving of non-consumables and succeeded in uncovering a wide network (Wiessner 1977; 1982; 1986). This has come to be known by the !Kung term hxaro, which means roughly ‘giving in formalized exchange’. By the time of marriage, the average !Kung will have between ten and sixteen hxaro partners, including both close kin and distant relatives and friends (Wiessner 1982: 72—4). Underlying the hxaro system of delayed, balanced reciprocity is an assumption that these giftgiving partners exist in a state of mutual generalized reciprocity of rights to water and plant resources (1982:74— 7).

In addition to exchange within !Kung society, there has long been trade contact between !Kung and other peoples (see, for example, Wilmsen 1986). The evidence is extensive: all of Zii/’ho,^ (Central ! Kung) country and beyond ‘seems to have been crisscrossed with well- developed trading networks’ (Gordon 1984:207). Implicit in the accounts of Gordon and Wilmsen is an assumption that other recent ethnographers have been blinded by their desire to see the !Kung as isolated remnants of primitive purity untouched by wider economic structures. But does this mean that they, or their even more ‘acculturated’ southern neighbours, have long since lost their primitive communism and mutual aid?

Communism, Capitalism, and ‘acculturated Bushmen’

In his definition of primitive communism, Lee (1988) recognizes a relative egalitarianism and emphasizes the communal ownership of land, rather than specifically the lack of hierarchical institutions. For Lee (1988: 254—5), even chiefly societies qualify as retaining primitive communist principles in a ‘semi-communal’ social structure (cf. Testart 1985; Flanagan 1989; Gulbrandsen 1991).

But to what extent are the Bushmen communistic? This dilemma lies at the root of the quarrel in the mid-1970s between Elizabeth Wily and H.J. Heinz. Wily argued (for example, 1973a; 1973b; 1976) that Bushman social organization exemplified principles of collective ownership and communal will, while Heinz argued (1970; 1973; 1975) that on the contrary it exhibited the incipient capitalist principles of private ownership and free enterprise. Each had interpreted their respective experiences at the !X settlement at Bere, where Wily had served as teacher and Heinz as benefactor and development planner, as evidence for the equation of Bushman ideology with their own.

Heinz established livestock-rearing at Takathswaane, on the main road across the Kalahari, in 1969. By 1971 he had moved a number of Takathswaane families to a new settlement at Bere, a few miles to the west. At Heinz’s instigation, !Xo« families from Okwa were invited to join the scheme too. The only requirement was that they should each own at least one cow. At that point, with two bands of different geographical origin, Bere was declared a ‘closed’ settlement. Early on in the project a shop and a school were built. Each was a success in some sense, but each also marked the onset of unanticipated difficulties. The shop was run by Heinz’s !Xo« wife, who because of her status and her financial skills soon found herself in a difficult position in the community. The school became the preserve of Liz Wily, who proved to be an excellent teacher but whose ideas were at odds with those of Heinz. The latter had explicitly set up Bere on capitalist principles, while Wily was said to have espoused at least some of the principles of Maoist China. Their well-publicized quarrel resulted in Wily leaving the scheme and taking up a post as Botswana’s first Basarwa (Bushman) Development Officer.

Today Bere is run by the Botswana government. It is fair to say that the !Xo are neither successful capitalists nor Maoists, though they may be, in Kropotkin’s loosest sense, ‘anarchist communists’. The greatest problem with the Bere scheme has always been the reluctance on the part of the !Xo residents to invest the time required to keep herds of animals. The small scale of livestock ownership also militated against subsistence by herding. Heinz was right to maintain that Bushman economics is predicated on individualism as much as on collectivism, but individual ownership of very small herds (often one beast per family) does not permit sufficient sales of livestock for the accumulation of capital, much less the maintenance of a fully fledged capitalist system.

In an earlier paper (Barnard 1986:49—50), I noted the tendency towards buying and selling meat, rather than exchanging or sharing it, between Nharo groups at Hanahai, another government settlement scheme to the north of Bere. It is significant, however, that despite such new buying and selling arrangements between social groups previously defined spatially as ‘band clusters’, these Nharo give meat freely, in the traditional manner, within the bands that make up a given band cluster. There is a temptation to regard buy ing/selling relationships as indicative of social change, simply because they have not occurred before. Yet it could well be that they define age-old divisions between social and territorial units—units which would not previously have had any contact at all with one another. It is hence not surprising that they buy and sell meat, and it would be more surprising if they did give meat freely across band cluster boundaries. If Bushmen are communists, then their communism is confined to the ‘commune’.

Primitive Communism and the Foraging Ethos

One element in a complex debate which has recently graced the pages of Current Anthropology (Solway and Lee 1990; Wilmsen and Denbow 1990) is the question of a primitive communist mode of production. The main protagonists in the wider, more implicit, debate are Richard Lee (for example, 1979; 1984), Lorna Marshall (1976), George Silberbauer (1981), and the many others who have described Bushman society as an entity in itself (the ‘isolationists’ or ‘traditionalists’); and Edwin Wilmsen (for instance, 1983; 1989), Carmel Schrire (1980), James Denbow (1984), Robert Gordon (1984), and others who have emphasized historical contacts between Bushmen and non-Bushmen (the ‘integrationists’ or ‘revisionists’). Jacqueline Solway and Richard Lee (1990) have bent considerably towards the revisionists in recognizing historical links, yet they nevertheless reject the radical criticisms of those who deny the existence of a mode of production based on foraging or sharing. Wilmsen and Denbow (1990) also accuse Lee in particular of a shift from describing Bushmen as exemplars of a ‘foraging’ (Lee 1981), to a ‘communal’ (Lee 1988; 1990) mode of production. This seems to be unacceptable to Wilmsen and Denbow because of their emphasis on external trade, but the simple existence of trade need not undermine Lee’s position. The key point, as Solway and Lee (1990:119) imply, is that foraging and communalism generally do go together. I prefer instead to think of a foraging mode of thought, which is linked to communal as well as individual interests. This mode of thought persists after people cease to depend on hunting and gathering as their primary means of subsistence.

Foraging remains very much in the ethos of Bushman society, even where groups look after boreholes and livestock, keep their own animals, and grow crops. The Bushmen on the margins of the larger, non-Bushman society are essentially foragers. To them wage-labour and seasonal changes in subsistence pursuits are but large-scale foraging strategies (Guenther 1986a; Motzafi 1986; Barnard 1988a). If the concept of ‘mode of production’ makes any sense at all, it makes sense as a broad characterization of all these activities. Bushman are ‘foragers’ in many ways. Kin classification and gift-giving involve social ‘foraging’, for relatives and for relationships of exchange (cf. Barnard 1978; Wiessner 1977). Their religious ideology is characterized as ‘foraging’ for ideas (cf. Guenther 1979; Barnard 1988b). Even the Khoekhoe word saan or san, so popular as an ethnic label for ‘Bushmen’, means simply ‘foragers’—with all the negative as well as the positive connotations ‘foraging’ conjures (cf. Guenther 1986b).[2]

Kropotkin used the splendidly sympathetic and detailed account of Peter Kolb (Kolben 1731) as his main source on the Khoekhoe or ‘Hottentots’ (Kropotkin 1987a [1902]:84–5). Kropotkin describes the Khoekhoe as being the same in ‘social manner’, but ‘a little more developed than the Bushmen’ (1987a [1902]:84). Indeed, he generalizes from Kolb’s description of the ‘Hottentots’ to ‘savages’ almost universally in one crucial regard— food sharing.

If anything is given to a Hottentot, he at once divides it among all present —a habit which, as is known, so much struck Darwin among the Fuegians. He cannot eat alone, and, however hungry, he calls those who pass by to share his food. And when Kolben expressed his astonishment thereat, he received the answer: ‘That is Hottentot manner.’ But this is not Hottentot manner only: it is an all but universal habit among the ‘savages’.

(Kropotkin 1987a [1902]:84)

Kropotkin goes on to quote at length Kolb’s views of Khoekhoe morality. For example: ‘One of the greatest Pleasures of the Hottentots certainly lies in their Gifts and Good Offices to one another’ (Kolben 1731:89—90). From the ‘Hottentots’, Kropotkin goes on to tell of the ‘natives of Australia’, the ‘Papuas’, the ‘Eskimos’, and others. The ‘Eskimos’ receive special commendation for their ‘communism’ (Kropotkin 1987a [1902] :88—9), which, like ‘communism’ among the Bushmen, Kropotkin thought was fast disappearing as a result of foreign influence.

There are two related problems here. First, there is the problem of the disappearing culture. Secondly, there is the problem of hunter-gatherer/ herder divide, so significant in modern anthropology that it overrides the more obvious unity of what later came to be called Khoisan culture. The first problem is simple. Cultures are always ‘disappearing’, just after they are studied. The phenomenon occurs consistently across the globe, with much the same frequency as, say, that cannibals are always found on the other side of the hill and not among one’s own kind (Arens 1979). The second problem concerns the failure of modern anthropologists to take in the idea of the unity of the Khoisan culture area. This unity seems to have been obvious to Kolb, and, I think, also to Kropotkin, but it is sadly lacking in recent work on both sides of the current ‘Great Bushman Debate’.

The Golden Age of Sharing

Price (1975) and Bird-David (1990) have drawn attention to the differences between ‘sharing’ and ‘reciprocity’. ‘Sharing’ is defined as an internal, integrative process of giving without the expectation of return, and resembles Sahlins’ notion of ‘generalized reciprocity’. It is frequently found within small groups such as bands. Beyond that, it ‘may be found universally, to varied extents and in varied realms, just as [balanced and negative reciprocity] are’ (Bird-David 1990:195). Indeed, it could well be ‘the most universal form of human economic behavior, distinct from and more fundamental than reciprocity’ (Price 1975:3). Price and Bird- David define ‘reciprocity’ as giving with the expectation of return—‘the gift’ in Mauss’s (1990 [1925]) sense.

It is commonplace to regard hunter-gatherers as having distinctive political and especially economic forms of organization, and sharing is often seen as especially significant in hunting and gathering societies. Yet, while some of these typically hunter-gatherer features of social structure (for example, egalitarianism) are much more applicable to Khoisan foragers than to Khoisan herders, there are nevertheless similarities which have until now escaped notice. In Khoekhoe and Damara society, institutionalized gift-giving and meat-sharing are as important as in some Bushman societies (Barnard 1992:169, 189—91, 203—5). Likewise, marital exchanges involving the transfer of goods, often cited as a typical feature of pastoralist societies, are found among Kalahari hunter-gatherers (Barnard 1980:120–2; Lee 1984:74–7). The existence of ‘sharing’ practices among the Khoekhoe and ‘reciprocity’ among Bushmen should cause us to rethink our notions of what constitutes a typical ‘hunting’ or ‘herding’ society, and indeed to consider the notion of a pan-Khoisan constellation of economic institutions. Kropotkin grasped this, and expressed this view accurately in his very brief discussion of mutual aid among the Bushmen and Khoekhoe.

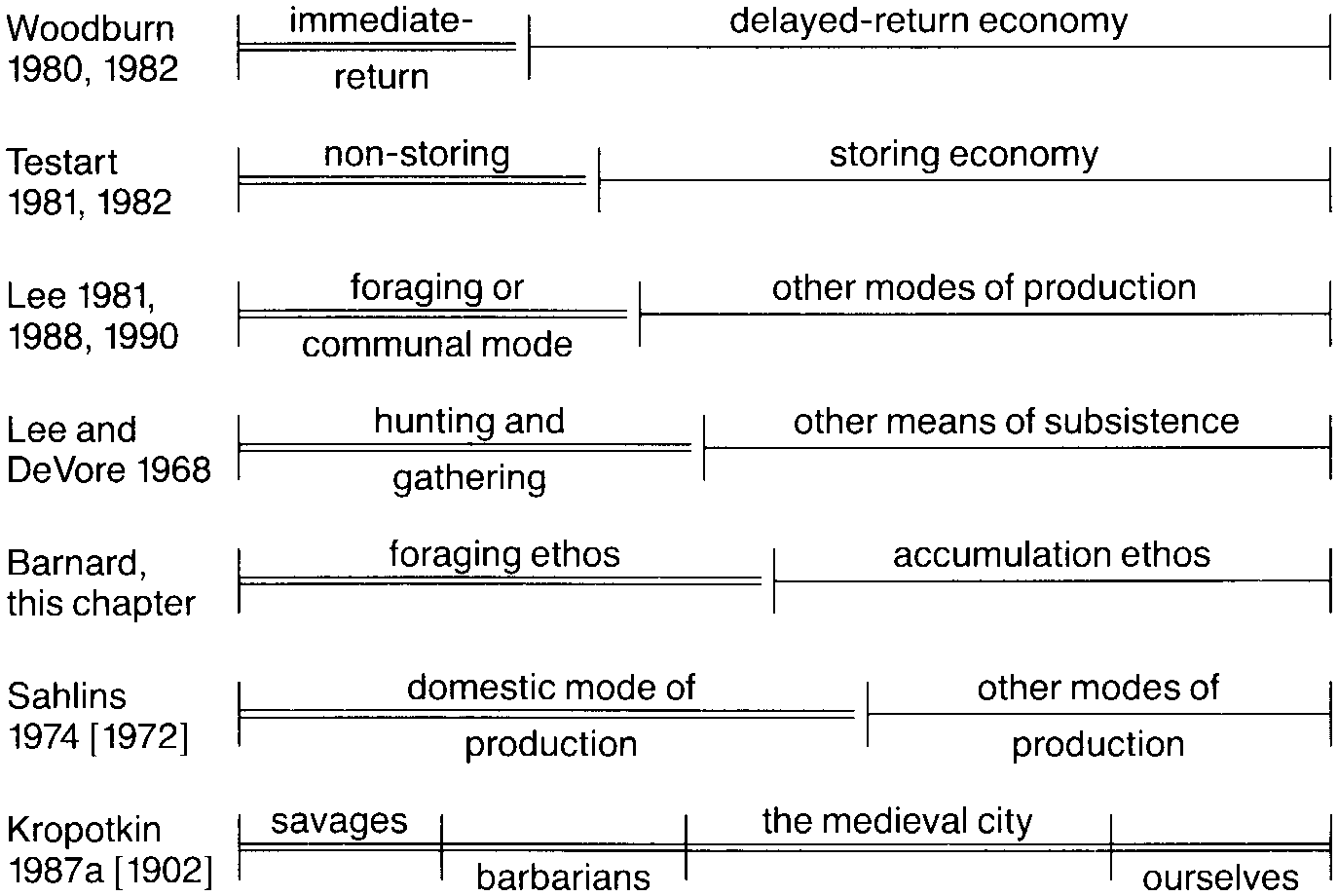

Most modern attempts to draw boundaries between ‘our kind of society’ and ‘other kinds’ have placed the boundary right down the middle— between ‘hunter-gatherers’ and ‘others’, between ‘Khoe’ and ‘San’ (for example, Lee and DeVore 1968). However, attempts to temper classification on the basis of means of subsistence with a closer look at the ideology of sharing and reciprocity have yielded different results. Thus the Golden Age of Sharing can be defined either more narrowly than the hunter-gatherer (for instance, Woodburn 1980, 1982; Testart 1981; 1982, Lee 1981, 1988, 1990), or more widely (Sahlins 1974). I prefer to see the notion of ‘sharing’ defined in cultural, ideological terms. My vision of a foraging ethos is not far from Lee’s, except that, unlike him, I do not conceive of such an ethos as dependent in any sense on the mode of production of the larger society. It could apply just as well, and with positive associations, to the san of any society, including the urban homeless of modern Western societies. Figure 1.1 illustrates, very loosely (with a double line), the relative extent of the Golden Age of Sharing according to each of the various theorists who have commented on the question.

I suggest that the idea of ‘foraging’ can help us to identify the central characteristics of Bushman society, not quite in the literal sense of Ingold (1986:79–100, 101–29; 1988), who emphasizes non-deliberate action, but in a sense which connotes a lack of concern about the specific result of the activity. When a Bushman man goes ‘hunting’, he will almost certainly stop to pick berries or nuts (cf. Barnard 1980:116–17). He might even bring some home, especially if the hunt proper is unsuccessful. His wife, in her turn, may go off to collect firewood and come back with some roots to roast. I find the term ‘foraging’ is useful as a description of these kinds of activity, and even more useful in designating the ethos and ideology of Bushman society.[3]

A Summary of Characterizations of Bushman Society

Bushman society has been characterized in any number of ways. The following list represents only a few of the characterizations which have been made since Kropotkin’s time:

-

primitive communism, or

-

incipient capitalism;

-

mutual aid, or

-

anarchy (in its negative sense);

-

universal kinship, or

-

immediate-return economies;

-

foraging mode of production, or

-

domestic mode of production;

-

natural purity and a mystical awareness of nature, or

-

technological simplicity, but with an ingenuity associated with a foraging ethos;

-

isolation from the wider regional politico-economic system of Southern Africa, or

-

integration into that system, as traders, labourers, and servants.

Some of these are contradictions of others. Indeed, I have deliberately paired a number of characterizations which can be taken as opposites, though not all pairings are really opposed in quite this manner. Nevertheless, characterizations emerge which highlight alternative understandings of Bushman society. Are they poor or rich? Violent or peaceful? Practical or mystical? Traditionally isolated from their neighbours or integrated in a network of widespread trade links? In a sense, each of these oppositions expresses a contradictory truth about Bushman society. They are poor because their wants are many; rich because their needs are few. They are violent because of the relatively high incidence of homicide; peaceful because of the lack of warfare in living memory. They are practical because of their successful adaptation to both the natural environment and changing social conditions; mystical because their adaptation to nature expresses a harmony lacking in ‘advanced’ societies. They are traditionally isolated, in the sense that both they and outsiders define them in terms of their relation to nature; yet they are integrated, in the sense that they have long traded and shared their land and resources with members of other ethnic groups. Each characterization identifies a different aspect of the same society.

This does not mean that the Bushmen are not really anarchists or communists. They are simultaneously both and neither. They are communists because they hold land in common. They are noncommunists because they each own movable property as individuals. They are anarchists because they possess no form of indigenous overlordship. They are non-anarchists because they recognize, and have long recognized, the overlordship of the neighbouring tribal chief, the colonial state, or the nation-state.

Conclusion

The descriptions available to Schapera when compiling his magnificent Khoisan Peoples of South Africa (1930) suggested that both the Khoekhoe and the Bushmen had a system of communal ownership over land. Neverthless, Schapera (1930:319, 321) rejected the idea that either this system or the widespread systems of sharing and exchange of food, livestock, and material culture, indicated a form of true ‘communism’, whereas earlier writers (such as von Francois 1896:222) had suggested it did. Schapera’s position seems to be part of a wider phenomenon. As Lee (for example, 1990:231—5) and Leacock (1983) have at least hinted, anthropologists writing in the decades following the Bolshevik Revolution had quite a different notion of ‘primitive communism’ than did those writing before it. Generally speaking, the term seems to have carried few political overtones before that time, whereas afterwards only Marxists have seen fit to use it at all. Not only did the authoritarian communists appropriate the state, they appropriated the word ‘communist’ too. Their intellectual descendants jealously guard it to this day, while others refrain from using it lest they be branded ‘Marxists’ or worse.

Kropotkin’s Mutual Aid was at the same time primitivist and evolutionist. Mutual aid is found in all human societies and in nature; that is, in animal societies. Yet, at the end of the day, Kropotkin’s understanding of Bushman society actually approaches the ‘revisionist’ view more closely than it does that of Lee, Marshall, Tanaka, and Silberbauer. In a speech to English anarchists in 1888, Kropotkin (1988a [1888]:102) described ‘Anarchist-Communism’ simply as a combination of the ‘two great movements’ of the nineteenth century: ‘Liberty of the individual’ and ‘social co-operation of the whole community’. It is worth some reflection that Kropotkin’s descriptions of societies he considered ‘communist’ might still serve as models of ethnographic generalization, if not as charters for political action.

I would like to thank Chris Hann, Adam Kuper, and Ed Wilmsen for their comments on earlier drafts.

References

Arens, W. (1979) The Man-eating Myth: Anthropology and Anthropophagy, Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Barnard, A. (1978) ‘Universal systems of kin categorization’, African Studies, 37: 69–81.

—— (1980) ‘Sex roles among the Nharo Bushmen of Botswana’, Africa, 50: 115–24.

—— (1981) ‘Universal kin categorization in four Bushman societies’, L’Uomo, 5: 219–37.

—— (1986) ‘Rethinking Bushman settlement patterns and territoriality’, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 7(1):41–60.

—— (1988a) ‘Cultural identity, ethnicity and marginalization among the Bushmen of southern Africa’, in R.Vossen (ed.) New Perspectives on Khoisan, Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag (Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 7).

—— (1988b) ‘Structure and fluidity in Khoisan religious ideas’, Journal of Religion in Africa, 18:216–36.

—— (1992) Hunters and Herders of Southern Africa: A Comparative Ethnography of the Khoisan Peoples, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bird-David, N. (1990) ‘The giving environment: another perspective on the economic system of gatherer-hunters’, Current Anthropology, 31:189–96.

Bleek, D.F. (1928) The Naron: A Bushman Tribe of the Central Kalahari, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bleek, W.H.I. (1875) A Brief Account of Bushman Folklore and Other Texts, Cape Town: Juta.

Burchell, W.J. (1822–24) Travels in the Interior of Southern Africa (2 vols), Glasgow: MacLehose.

Darwin, C. (1871) The Descent of Man, and Selection in Relation to Sex (2 vols), London: John Murray.

Denbow, J.R. (1984) ‘Prehistoric herders and foragers of the Kalahari: the evidence of 1500 years of interaction’, in C.Schrire (ed.) Past and Present in Hunter Gatherer Studies, Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Draper, P. (1978) ‘The learning environment for aggression and anti-social behavior among the !Kung’, in A.Montagu (ed.) Learning Non-aggression: The Experience of Non-literate Societies, New York: Oxford University Press.

Flanagan, J.G. (1989) ‘Hierarchy in simple “egalitarian” societies’, Annual Review of Anthropology, 18:245–66.

Francois, H.von (1896) Nama und Damara. Deutsch Sud-West Afrika, Magdeburg: Baensch.

Fritsch, G. (1868) Drei Jahre in Sud-Afrika, Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt.

—— (1872 [1863]) Die Eingeborenen Sud-Afrikas, Breslau: Ferdinand Hirt.

Gordon, R. (1984) ‘The !Kung in the Kalahari exchange: an ethnohistorical perspective’, in C.Schrire (ed.) Past and Present in Hunter Gatherer Studies, Orlando, FL: Academic Press.

Guenther, M.G. (1979) ‘Bushman religion and the (non)sense of anthropological theory of religion’, Sociologus, 29:102—32.

—— (1986a) ‘From foragers to miners and bands to bandits: on the flexibility and adaptability of Bushman band societies’, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 7(1): 133–59.

—— (1986b) ‘“San” or “Bushmen”?’, in M.Biesele, with R.Gordon and R.Lee (eds) The Past and Future of !Kung Ethnography: Critical Reflections and Symbolic Perspectives, Essays in Honour of Lorna Marshall, Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag (Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung, 4).

Gulbrandsen, 0. (1991) ‘On the problem of egalitarianism: the Kalahari San in transition’, in R.Gr0nhaug, G.Henriksen, and G.Haaland (eds) Ecology of Choice and Symbol: Essays in Honour ofFredrik Earth, Bergen: Alma Mater.

Heinz, H.J. (1970) Experiences Gained in a Bushman Pilot Settlement Scheme (Interim Report), Johannesburg: Dept. of Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand (Occasional Paper No. 1).

—— (1973) Bere: A Balance Sheet, Johannesburg: Dept. of Pathology, University of the Witwatersrand (Occasional Paper No. 4).

—— (1975) ‘Acculturation problems arising in a Bushman development scheme’, South African Journal of Science, 71:78–85.

Ingold, T. (1986) The Appropriation of Nature: Essays on Human Ecology and Social Relations, Manchester: Manchester University Press.

—— (1988) ‘Notes on the foraging mode of production’, in T.Ingold, D.Riches, and J.Woodburn (eds) Hunters and Gatherers, Vol. 2: Property, Power and Ideology, Oxford: Berg Publishers.

Keenan, J. (1981 [1977]) ‘The concept of the mode of production in huntergatherer societies’, in J.S.Kahn and J.R.Llobera (eds) The Anthropology of Precapitalist Societies, London: Macmillan.

Kolben [Kolb], P. (1731) The Present State of the Cape of Good-Hope, Vol. I (trans. G. Medley), London: W.Innys.

Kropotkin, P. (1910) ‘Anarchism’, Encyclopaedia Britannica (11th edn), Vol. 1, pp. 914–19. (Also reprinted in Kropotkin 1987c.)

—— (1987a [1902]) Mutual Aid: A Factor of Evolution, London: Freedom Press.

—— (1987b [1887]) Anarchist Communism: Its Basis and Principles. (In Kropotkin 1987c:23–60.)

—— (1987c) Anarchism and Anarchist Communism, N.Walter (ed.), London: Freedom Press.

—— (1987d [1897]) The State: Its Historic Role (translated from the French), London: Freedom Press.

------- (1988a) Act for Yourselves: Articles from Freedom, 1886—1907, N.Walter and H. Becker (eds) London: Freedom Press.

—— (1988b [1899]) Memoirs of a Revolutionist, London: The Cresset Library.

Leacock, E. (1983) ‘Primitive communism’, in T.Bottomore (ed.) A Dictionary of Marxist Thought, Oxford: Blackwell Reference.

Lee, R.B. (1965) ‘Subsistence ecology of !Kung Bushmen’, Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of California at Berkeley.

—— (1979) The !Kung San: Men, Women, and Work in a Foraging Society, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1981 [1980]) ‘Is there a foraging mode of production?’, Canadian Journal of Anthropology, 2(1):13–19.

—— (1984) The Dobe !Kung, New York: Holt, Rinehart & Winston.

—— (1988) ‘Reflections on primitive communism’, in T.Ingold, D.Riches, and J. Woodburn (eds), Hunters and Gatherers, Vol. 1: History, Evolution and Social Change. Oxford: Berg Publishers.

—— (1990) ‘Primitive communism and the origins of social inequality’, in S.Upham (ed.) The Evolution of Political Systems: Sociopolitics in Small-scale Sedentary Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Lee, R.B. and DeVore, I. (1968) ‘Problems in the study of hunters and gatherers’, in R.B.Lee and I.DeVore (eds), Man the Hunter, Chicago: Aldine.

Lichtenstein, M.H.C. (1811—12) Reisen im sudlichen Afrika in dem Jahren 1803, 1804, 1805 und 1806 (2 vols), Berlin: C.Salfeld.

Marshall, L. (1961) ‘Sharing, talking, and giving: relief of social tensions among ! Kung Bushmen’, Africa, 31:231—49. (Reprinted with amendments in Marshall 1976.)

—— (1976) The !Kung of Nyae Nyae, Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Mauss, M. (1990 [1925]) The Gift: The Form and Reason for Exchange in Archaic Societies, London: Routledge.

Moffat, R. (1842) Missionary Labours and Scenes in Southern Africa, London: Snow.

Motzafi, P. (1986) ‘Whither the “true Bushmen”: the dynamics of perpetual marginality’, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 7(1):295—328.

Philip, J. (1828) Researches in South Africa, Illustrating the Civil, Moral and Religious Condition of the Native Tribes (2 vols), London: Duncan.

Price, J.A. (1975) ‘Sharing: the integration of intimate economies’, Anthropologica (n.s.), 17:3–27.

Reclus, E. (1878–94) La Nouvelle geographic universelle, la terre et les hommes (19 vols), Paris: Librairie Hachette et Cie.

Sahlins, M. (1974 [1972]) Stone Age Economics, London: Tavistock Publications.

Schapera, I. (1930) The Khoisan Peoples of South Africa: Bushmen and Hottentots, London: George Routledge & Sons.

Schrire, C. (1980) ‘An inquiry into the evolutionary status and apparent identity of San hunter-gatherers’, Human Ecology, 8:9–32.

Silberbauer, G.B. (1965) Report to the Government of Bechuanaland on the Bushman Survey, Gaberones [Gaborone]: Bechuanaland Government.

—— (1981) Hunter and Habitat in the Central Kalahari Desert, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1982) ‘Political process in G/wi bands’, in E.Leacock and R.Lee (eds) Politics and History in Band Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Solway, J.S. and Lee, R.B. (1990) ‘Foragers, genuine or spurious? Situating the Kalahari San in history’, Current Anthropology, 31:109—46.

Tanaka, J. (1980) The San, Hunter-gatherers of the Kalahari (trans. D.W.Hughes), Tokyo: University of Tokyo Press.

Testart, A. (1981) ‘Pour une typologie des chasseurs-cueilleurs’, Anthropologie et Societes 5(2):177–221.

------- (1982) Les chasseurs-cueilleurs ou l’origine des inegalites, Paris: Societe d’Ethnographie.

—— (1985) Le communisme primitif, I: Economie et ideologie, Paris: Editions de la Maison des Sciences de l’Homme.

Waitz, T. (1860) Anthropologie der Naturvdlker, Vol. II: Die Negervdlker und ihre Verwandten, Leipzig: G.Gerland.

Wiessner, P.W. (1977) ‘Hxaro: a regional system of reciprocity for reducing risk among the !Kung San’ (2 vols), Unpublished Ph.D. dissertation, University of Michigan, Ann Arbor.

—— (1982) ‘Risk, reciprocity, and social influence on !Kung San economies’, in E. Leacock and R.Lee (eds) Politics and History in Band Societies, Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

—— (1986) ‘!Kung San networks in a generational perspective’, in M.Biesele, with R.Gordon and R.Lee (eds) The Past and Future of !Kung Ethnography: Critical Reflections and Symbolic Perspectives, Essays in Honour of Lorna Marshall, Hamburg: Helmut Buske Verlag (Quellen zur Khoisan-Forschung 4).

Wilmsen, E.N. (1983) ‘The ecology of an illusion: anthropological foraging in the Kalahari’, Reviews in Anthropology, 10:9—20.

—— (1986) ‘Historical process in the political economy of San’, Sprache und Geschichte in Afrika, 7(2):413—32.

—— (1989) Land Filled with Flies: A Political Economy of the Kalahari, Chicago and London: University of Chicago Press. and J.R.Denbow (1990) ‘Paradigmatic history of San-speaking peoples and current attempts at revision’, Current Anthropology, 31:489—524.

Wilson, M.L. (1986) ‘Notes on the nomenclature of the Khoisan’, Annals of the South African Museum, 97(8):251—66.

Wily, E.A. (1973a) ‘An analysis of the Bere Bushman settlement scheme’, Unpublished report to the Ministry of Local Government and Lands, Gaborone, Botswana.

—— (1973b) ‘Bere as a prototype for further development’, Unpublished report to the Ministry of Local Government and Lands, Gaborone, Botswana.

—— (1976) ‘Bere and Ka/Gae’, Unpublished report to the Ministry of Local Government and Lands, Gaborone, Botswana.

Woodburn, J. (1980) ‘Hunters and gatherers today and reconstruction of the past’, in E.Gellner (ed.) Soviet and Western Anthropology, London: Duckworth.

------- (1982) ‘Egalitarian societies’, Man (n.s.), 17:431—51.

[1] Kropotkin’s knowledge of Bushmen was entirely second-hand. In contrast, Dorothea Bleek grew up with Bushmen. Her father, Wilhelm Bleek, was the world’s foremost authority on Bushman languages and folklore. After his untimely death in 1875, his work was continued by Dorothea’s aunt Lucy Lloyd, and ultimately by Dorothea herself. Kropotkin’s main source on the Bushmen seems to have been Volume 2 of Theodor Waitz’s six-volume survey, Anthropologie der Naturvdlker (Waitz 1860). Among primary sources he cites Lichtenstein (1811—12), Fritsch (1872 [1863]; 1868) and W.H.I.Bleek (1875), and mentions in passing Philip (1828), Burchell (1822—24) and Moffat (1842), all cited by Waitz. Kropotkin also refers to Elisee Reclus’s nineteen-volume Geographic universelle (1878—94). Like Kropotkin, Reclus was both a geographer and an anarchist, and the two had worked closely together in France in the 1870s.

[2] It is a peculiar irony that this term is the one favoured by both Lee (who calls these people ‘San’) and Wilmsen (who calls them ‘San-speaking peoples’), when most other specialists have returned to other labels—most commonly ‘Bushmen’. The subject of what to call ‘Bushmen’ is also an ongoing debate, and one with a grand history. The first recorded usage seems to have been in 1682, in the journal of Olof Bergh (Wilson 1986: 257). In the early days of Dutch settlement at the Cape, Soaqua or Sonqua (the Cape Khoekhoe masculine plural form; San is common gender plural) seems to have been more common, but Bosjesmans, Bushmen, and other variants gained predominance by the late eighteenth century. Peter Kolb (or Kolben), for example, referred to ‘a Sort of Hottentot Banditti ... call’d Buschies or High-way Men’ (Kolben 1731:89–90). Kolb’s account was probably far better known in the eighteenth than it has been in the twentieth century. From the seventeenth to the nineteenth centuries, Bushmen were frequently described as part of ‘Hottentot’ society, and indeed late twentieth-century work by some of the revisionists (such as Schrire 1980) suggests a return to this view.

[3] Ingold shares with Kropotkin the idea of a continuity between animal and human societies, though the modern scholar also points to a number of significant contrasts. I share many of the specific views Ingold espouses, but disagree with his restriction of the term ‘foraging’ to non-human activities alone. In my view this places undue emphasis on the intentionality of human activities.