R. Brian Ferguson

Chimpanzees, War, and History

Are Men Born to Kill?

Advance Praise for Chimpanzees, War, and History

The Imbalance of Power Hypothesis

Competition for Scarce Resources

Initial Views on Territorial Organization

Ambiguous Observations, Defining Concepts

Hunting, Nutrition, and Preferences

6. Explaining the War and Its Aftermath

The Display Violence Hypothesis Applied

The Changing Human Context, post 1983

How These Afflictions Dis-Balanced Gombe Groups

(Relative) Peace Returns, 1984–1997

Territorial Jostling in the North

Mitumba’s Rusambo—A Classic Intergroup Killing?

Intergroup Attacks on Mothers and Infants

8. Interpreting Gombe Violence

The IoPH, RCRH, and Demonic Expectations

Does the IoPH Explain Behavior?

RCRH, Reducing Relative Size of Outside Male Coalitional Strength

Resource Competition and the Human Impact Hypothesis

Leaders, Learning, and Violence

Increasing Human Disruption, Status Turmoil, and Internal Violence

The Gombe Paradigm Found, and Lost

9. Mahale: What Happened to K Group?

The Gombe Paradigm Shapes Interpretations

Boundary Patrols and Incursions

Between-Group Transfers of Females and Sons

Disappeared Does Not Mean Killed

Deposed Alphas—Exiled or Killed within Group

Initial Observations and Provisioning

Inward Violence against Infants and Display

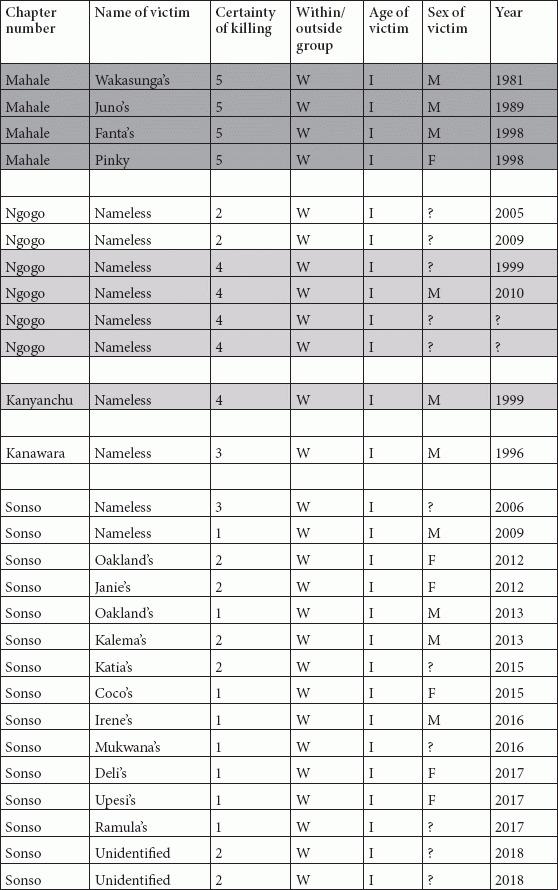

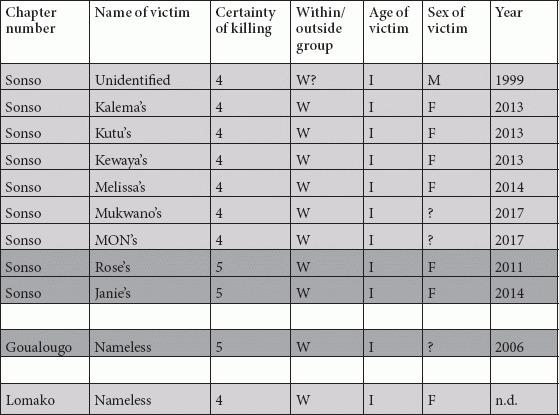

Observed or Suspected Infant Killings

Later Mahale, Not as Bad as Late Gombe (Yet)

Other Impact, Differing Effects

12. Ngogo Territorial Conflict

13. Scale and Geopolitics at Ngogo

14. The Ngogo Expansion, RCH + HIH

Ngogo Population Growth, Again

Hunting and Intergroup Conflict

Understanding the Ngogo Expansion

Ethical Notes and Explanations

Males Behaving Badly, and Females Cutely

“Chimp Girls Play with Dolls” (Handwerk 2010)

16. Budongo, Early Research and Human Impact

Early Research and Human Environment

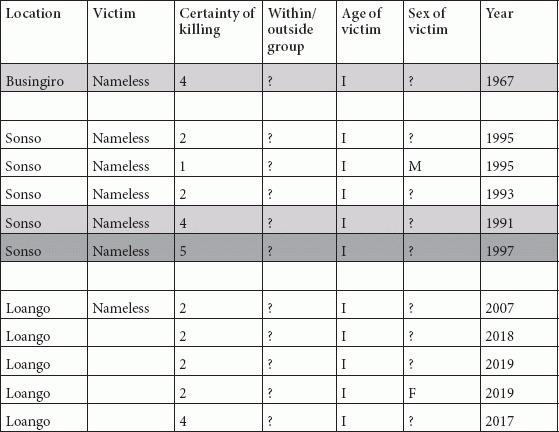

Busingiro and Intergroup Interactions

The Human Touch Becomes Malignant

The Pre–Great Revision Alternative, Unconsidered

Numbers, Territory, and Intergroup Behaviors

Infanticide, Disappearances, and Territorial Pressure

An Internal Killing and Politics

The Great Immigration—That Didn’t Happen, or Did It?

Infant Killers, Both Male and Female

A “Highly Infanticidal Population of Chimpanzees”

A Display Violence and Human Impact

Adaptationism and Historical Disruption at Budongo

18. Eastern Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

Regional Groupings—How Separate?

19. Central Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

20. Western Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus

Across Africa, Variation and Devastation

The Devastation of Tai Chimpanzees

Islandization, but with Different Consequences

22. Sociality and Intergroup Relations

Ranging, Associating, Hunting, and Patrolling

Patterns of Intergroup Conflict

Competition for Scarce Resources

Meat, Nuts, and Territoriality

Human Impact and Territoriality

Internal Politics and External Killings

Provisioning and Intergroup Hostility

New Relations at the Feeding Stations

Bonobo Groups and Their Interactions

25. Social Organization and Why Male Bonobos Are Less Violent

The Species Dichotomy Questioned

The Behavioral Organization of Sex and Hierarchy: Constructing a Social Niche

Intersexual Dominance, Aggression, and Sexual Coercion

26. Evolutionary Scenarios and Theoretical Developments

A Demonic Perspective on Angels

Evolving Males Out of Demonism

The Self Domestication Hypothesis

Evolutionary Developmental Biology

Social Behavior as Inheritance

Revo-Evo Bonobo: Nature/Nurture on the Species Divide

Nature and Nurture on the Species Divide

Finer Points of Behavioral Comparisons

Social Complications in Neurobiology and Endocrinology

Part IX: Adaptive Strategies, Human Impact, and Deadly Violence

The Adaptive Infanticide Paradigm

The Sexual Coercion Hypothesis

Steep Hierarchy and Internal Takeover

Display Killing and Reproductive Success?

Internal Infant Killings by Females

SSI Meets Rival Coalition Reduction Hypothesis (RCRH)

Killing Infants: Adaptive Strategies and Human Impact

28. The Case for Evolved Adaptations, by the Evidence

Intergroup Killing Is Rare, Not Normal

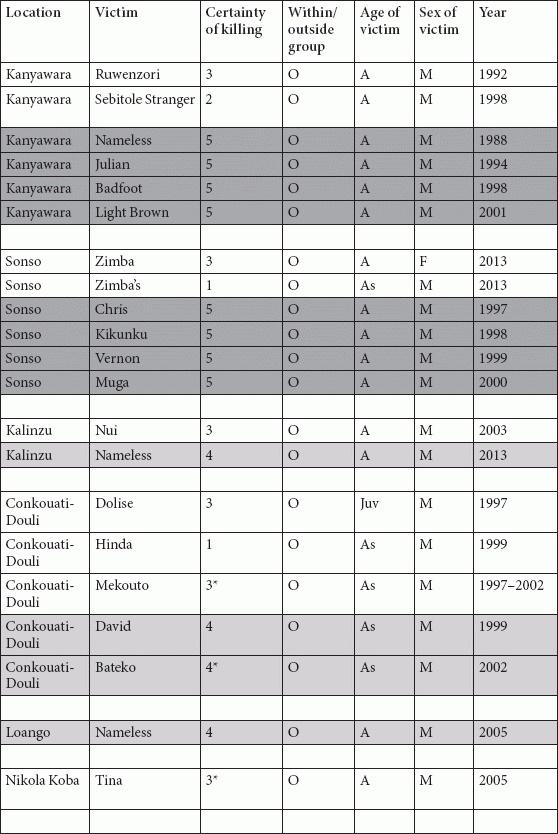

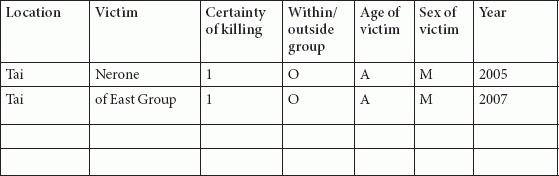

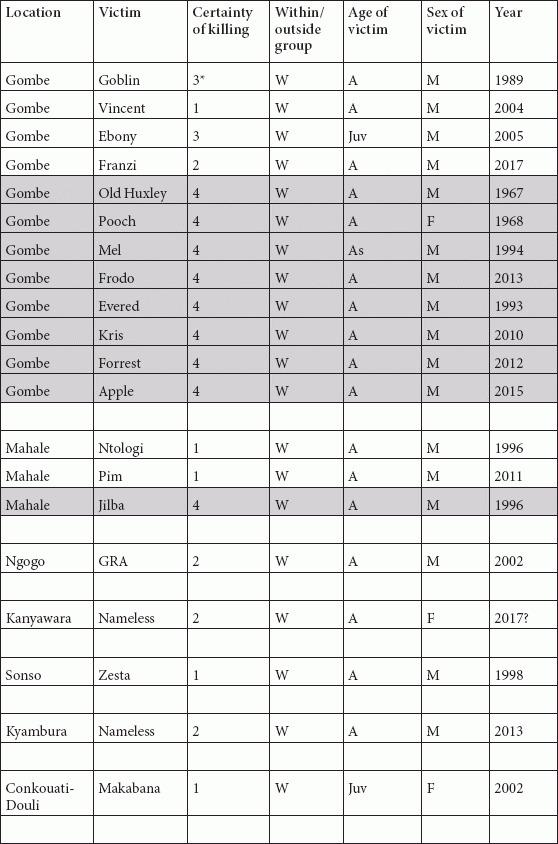

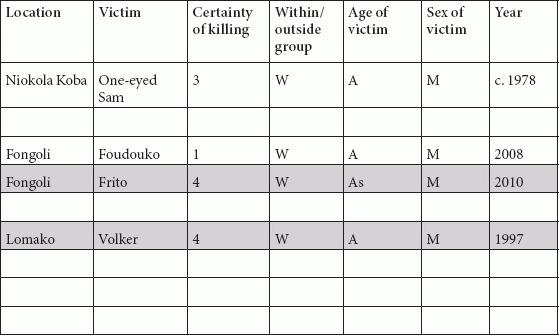

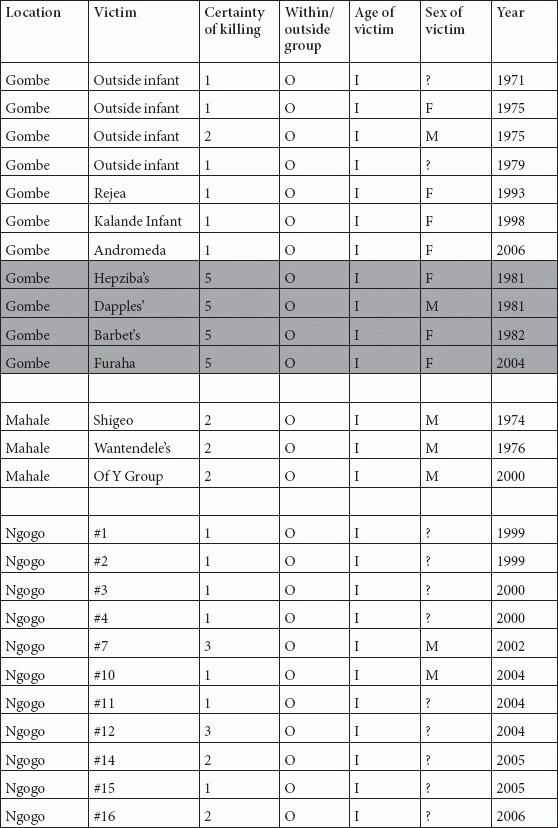

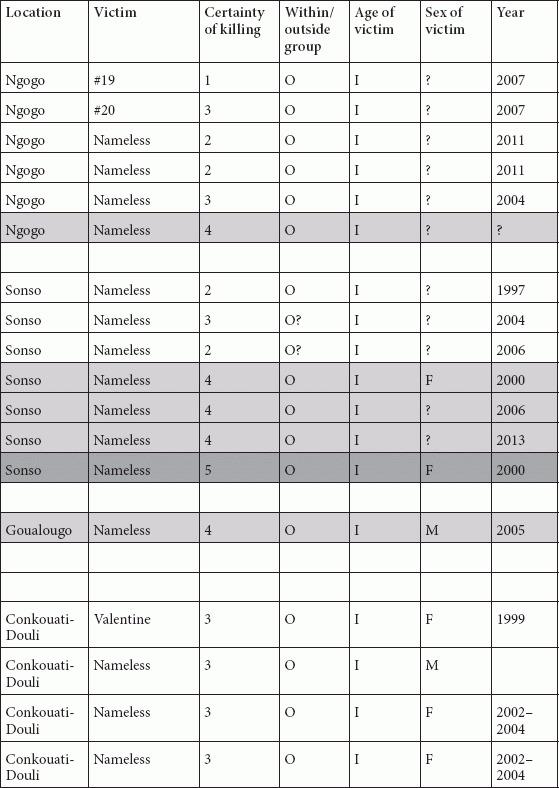

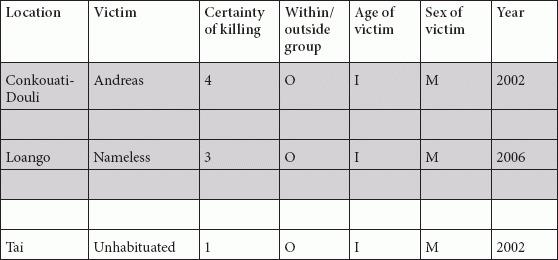

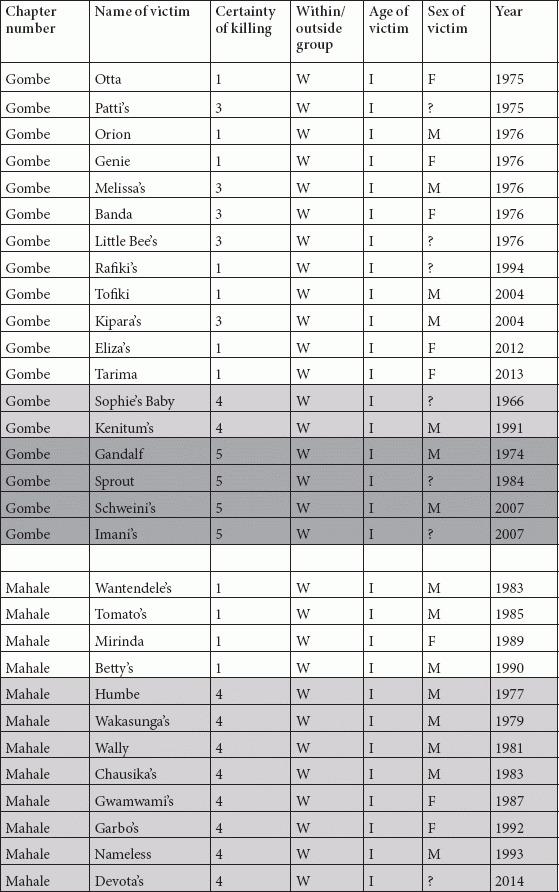

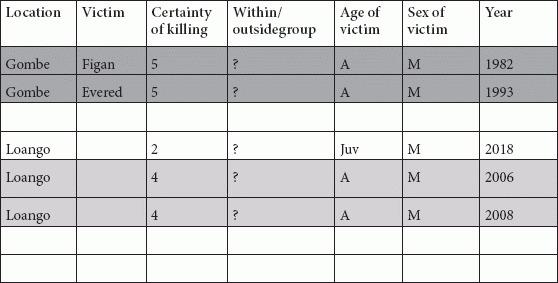

External Adult Killings, Observed And Inferred

The Two “Wars” and Adaptive Benefits

Outside Males Attacked, Tolerated, and How Does It Add Up?

Imbalances of Power—Necessary or Sufficient for Killing?

Tipping the Rival Male Balance?

How Related Are Philopatric Males?

Attacking or Recruiting Outside Females

Recruiting More Females for Mating

Adaptive Variables and Models Summarized

29. Human Impact, Critiqued and Documented

Human Impact, Politics, and Killings: A Narrative Summary

30. The Demonic Perspective Meets Human Warfare

Where Does Demonic/Adaptationist Theory Apply?

The Main Application: Band-and-Village Societies

People Are Not Innately Tribal

How Does the Demonic/Adaptationist Theory Apply?

“Attacking Outgroup Members Only When Safe”

The Cultural Rewards War-Risk Hypothesis

The Territorial Foundation of All Applications

The Roots of Forager “Exclusivity”

31. Species-Specific Foundations of Human War

Great Divide I: Symbol and Language

Practicality and Symbolic Construction in War

Great Divide II: Culture as a Causal System

A Cultural Materialist Paradigm

32. Applications: An Anthropology of War

Application: The “Fierce” Yanomami

Application: War in Tribal Zones

Application: The Origins and Intensifications of War

Application: Comparative Politics

War and Society in Ancient States

Applications: Contemporary War

Structure, Superstructure, and Moral Conversion

[Front Matter]

Advance Praise for Chimpanzees, War, and History

“Are men born to kill? Some have been quick to assume evolved killer tendencies exist in both humans and chimpanzees. Drawing upon a truly impressive body of evidence, R. Brian Ferguson reopens the case. He casts substantial doubt on the assertion that chimpanzees and humans have been selected to kill. Chimpanzees, War, and History is meticulously researched, convincingly argued, and fascinating to read as Ferguson unveils a very different explanation for why chimpanzees kill.”

—Douglas P. Fry, author of Beyond War and co-author of Nurturing Our Humanity

“Debates about the evolutionary ‘nature’ of war and the innateness of male violence are ubiquitous. And our close cousins, the chimpanzees, are often at center stage. In a book sure to enrage some, and please others, R. Brian Ferguson offers a truly comprehensive presentation and analysis of the available data on chimpanzee warfare and violence and opines on its relation to humanity. Agree or disagree with the conclusions, there is no denying the value of this in-depth, historical, socioecological, and sociocultural treatment of the chimpanzee wars. Ferguson furthers our understanding of war and violence in chimpanzees and beyond.”

—Agustín Fuentes, author of Why We Believe: Evolution and the Human Way of Being

“This is a magnificent work by the greatest living scholar of human warfare. Ferguson applies his intellect to chimpanzee warfare, and makes, in my consideration, an air-tight case AGAINST speaking of ‘our chimp ancestors’ when it comes to war. He has turned the standard view (given, for example, in Wrangham and Peterson’s Demonic Males) upside down. He is convincing, and, moreover, he is entertaining. This is an important work not just for scholars of war and chimpanzee researchers but for all people interested in human nature. A single word sums up my view: Magisterial!”

—Jeffrey Moussaieff Masson, author of When Elephants Weep and The Assault on Truth

“Are chimp intergroup killings the evolutionary precursors to human warfare? Has our evolution given us deadly proclivities? From R. Brian Ferguson, in this book, we get a firm and definitive ‘no’. Human killing and warfare cannot, he argues, be attributed to our primate heritage. A fine contribution to an ongoing debate.”

—Vernon Reynolds, Professor Emeritus, School of Anthropology, University of Oxford

“ ‘Men are not born to kill, but they can be cultivated to kill. Don’t blame evolution.’ The last line of Ferguson’s incredible survey of studies of the higher primates, showing definitively that all the analogy-based talk of humans as the killer apes—those ferocious monsters at the beginning of 2001: A Space Odyssey—is just that: talk. In an age when it seems that war will never end, understanding human nature and the distorting effects of culture is vital. There can be no better starting place than Chimpanzees, War, and History.”

—Michael Ruse, author of Why We Hate: Understanding the Roots of Human Conflict

“Many scholars view warfare as inevitable, with deep and ancient roots. But this is a myth, arising from cherry-picking data, confusing mobile and sedentary hunter-gatherers, and ignoring Westernized causes of war among indigenous peoples. Ferguson has led the debunking of this myth. In this superb, important book, he demolishes two of its building blocks—the supposed inevitability of chimpanzee proto-warfare, and our link to a supposed chimpanzee-like past.”

—Robert M. Sapolsky, John A. and Cynthia Fry Gunn Professor of Biology, Neurology, and Neurosurgery, Stanford University

[Title Page]

Chimpanzees, War, and History

Are Men Born to Kill?

R. BRIAN FERGUSON

[Copyright]

Oxford University Press is a department of the University of Oxford. It furthers the University’s objective of excellence in research, scholarship, and education by publishing worldwide. Oxford is a registered trade mark of Oxford University Press in the UK and certain other countries.

Published in the United States of America by Oxford University Press

198 Madison Avenue, New York, NY 10016, United States of America.

© Oxford University Press 2023

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may be reproduced, stored in a retrieval system, or transmitted, in any form or by any means, without the prior permission in writing of Oxford University Press, or as expressly permitted by law, by license, or under terms agreed with the appropriate reproduction rights organization. Inquiries concerning reproduction outside the scope of the above should be sent to the Rights Department, Oxford University Press, at the address above.

You must not circulate this work in any other form and you must impose this same condition on any acquirer.

CIP data is on file at the Library of Congress

ISBN 978–0–19–750675–2

eISBN 978–0–19–750677–6

DOI: 10.1093/oso/9780197506752.001.0001

Contents

List of Illustrations

Preface

Acknowledgments

Part I: Controversies

1.

From Nice to Brutal

2.

The Second Generation

3.

Theoretical Alternatives

Part II: Gombe

4.

From Peace to “War”

5.

Contextualizing Violence

6.

Explaining the War and Its Aftermath

7.

Later Gombe

8.

Interpreting Gombe Violence

Part III: Mahale

9.

Mahale: What Happened to K Group?

10.

Mahale History

Part IV: Kibale

11.

Kibale

12.

Ngogo Territorial Conflict

13.

Scale and Geopolitics at Ngogo

14.

The Ngogo Expansion, RCH + HIH

15.

Kanyawara

Part V: Budongo

16.

Budongo, Early Research and Human Impact

17.

Sonso

Part VI: Eleven Smaller Cases

18.

Eastern Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes schweinfurthii

19.

Central Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes troglodytes

20.

Western Chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes verus

Part VII: Tai

21.

Tai and Its Afflictions

22.

Sociality and Intergroup Relations

23.

Killings and Explanations

Part VIII: Bonobos

24.

Pan paniscus

25.

Social Organization and Why Male Bonobos Are Less Violent

26.

Evolutionary Scenarios and Theoretical Developments

Part IX: Adaptive Strategies, Human Impact, and Deadly Violence: Theory and Evidence

27.

Killing Infants

28.

The Case for Evolved Adaptations, by the Evidence

29.

Human Impact, Critiqued and Documented

Part X: Human War

30.

The Demonic Perspective Meets Human Warfare

31.

Species-Specific Foundations of Human War

32.

Applications: An Anthropology of War

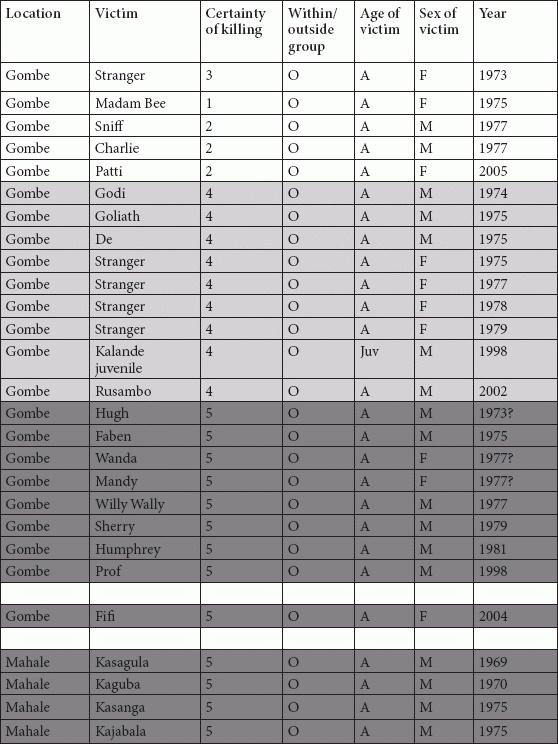

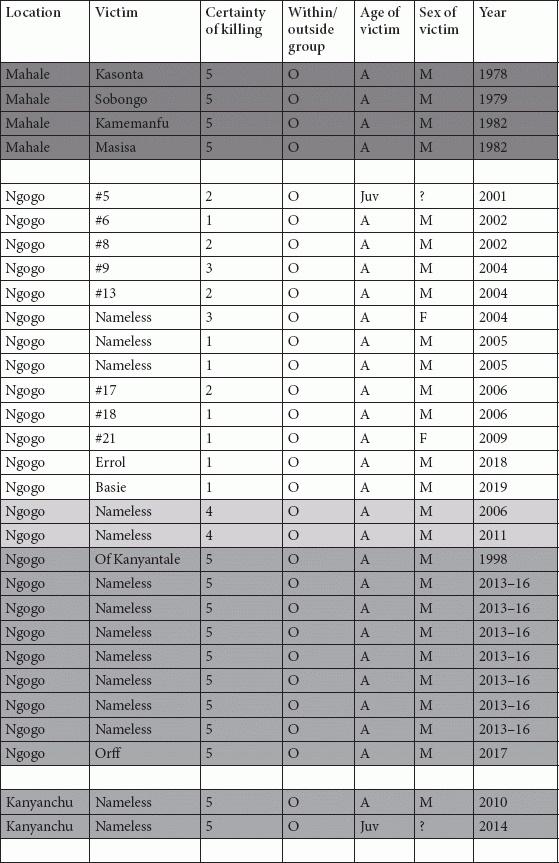

Tables

References

Index

List of Illustrations

Part II

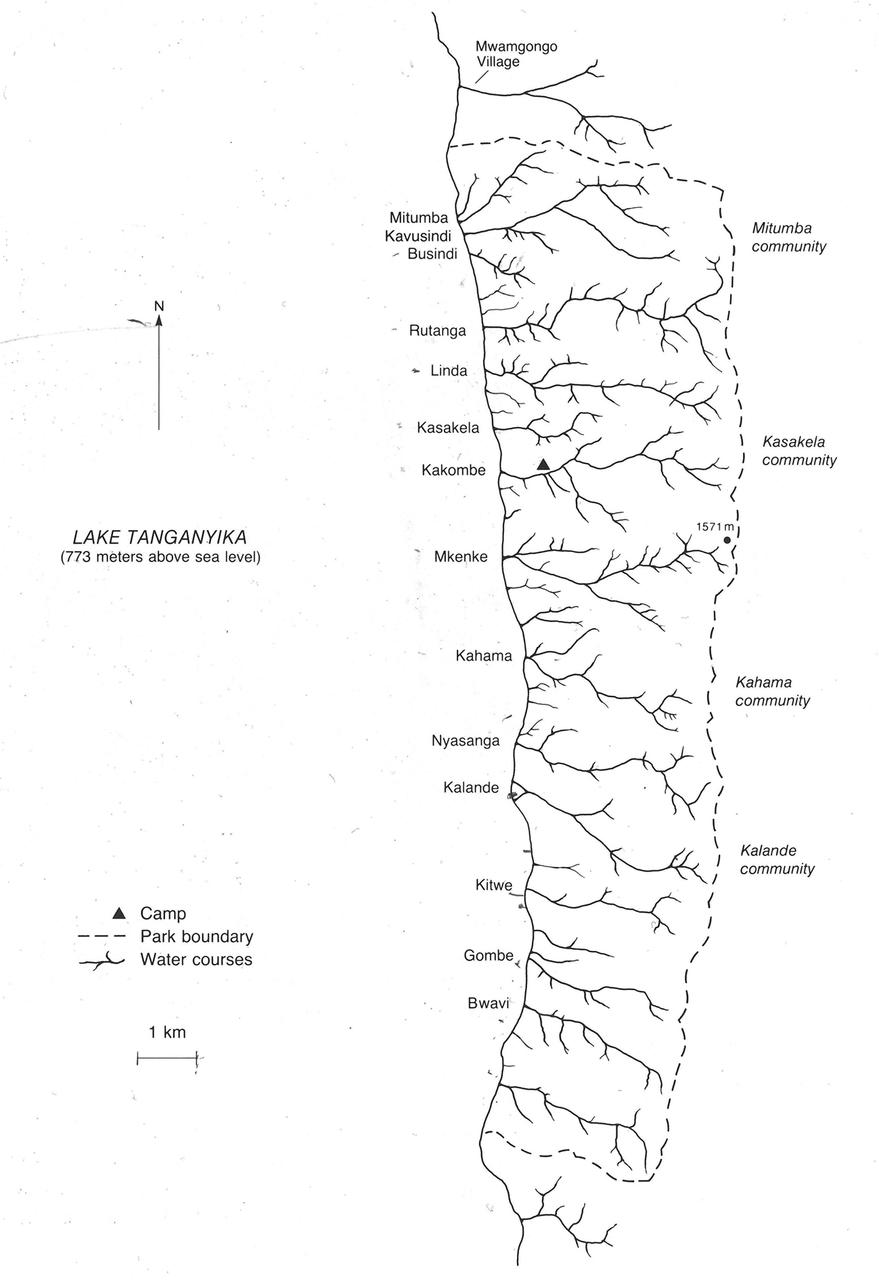

2.1

Gombe Map and Groupings

2.2

Three Researchers Photographing Chimpanzees

2.3

Gombe Feeding Bunker in System E

2.4

Gombe Chimpanzee Body Mass over Time

2.5

Gombe Number of Adult Males and Community Range Size

Part III

3.1

Mahale Territories and Feeding Stations

3.2

Chimpanzees Surrounded by Tourists at Mahale

3.3

Map of Baboon Invasion, Mahale

Part IV

4.1

Composite of Habitat Loss and Chimpanzee Groups

4.2

Ngogo Range with Infant Killings c. 1999

4.3

Ngogo Killings and Range Expansion

4.4

Chimpanzee Population Change at Ngogo 1975–2007, by Encounters along Observation Transects

4.5

Red Colobus Hunts around Ngogo, 1995–1998 and 1999–2002

4.6

Kanyawara Forest Disturbance

4.7

Kanyawara Territorial Encounters and Kills

Part V

5.1

Busingiro Ranges

5.2

Infant Killings and Attacks at Sonso

Part VI

6.1

Chimpanzee Subspecies and Bonobo Research Sites

6.2

Kalinzu Chimpanzee with Snare Injury

6.3

Goualougo Sociogram of Individual Associations

6.4

Lope Fruiting Levels 1987, 2017

Part VII

7.1

Tai Community Numbers

Part VIII

8.1

Average Taxonomic Differences between Species and Locations

8.2

GG Rubbing Positions among Bonobos and Chimpanzees

Part IX

9.1

Relation between Density and Kills Per Year

Preface

Between two World Wars, as a bloodied world grasped at a League of Nations, Albert Einstein asked Sigmund Freud why men can be roused to the carnage of war, a question publicly known as “Why War?” The physicist passingly noted the machinations of “the governing class” and arms makers, supported by organizing minions in schools, press, and church. That much was obvious. But the deeper question, he thought, was why do human beings readily join into such horrific violence? Einstein believed he already knew why. “Only one answer is possible. Because man has within him a lust for hatred and destruction.” What he wanted from Freud was a scientific understanding of this lust. Freud obliged. Psychoanalysis had shown that humans have a biologically based “death instinct”—a fundamental urge of self-destruction that is better turned outward against others. “It may perhaps seem to you as though our theories are a kind of mythology and, in the present case not even an agreeable one. But does not every science come in the end to a kind of mythology like this?” (Einstein 2002 [1932]:189; Freud 2002 [1932]:198). Freud’s death wish does not get much credence today, but other theories of innate depravity are alive and well.

Why do people make war? Why is war so common? Is it human nature for men to kill outsiders? Many say yes. In the 1960s legendary fossil hunter Raymond Dart (1959) traced our blood-drenched heritage in damage done to early hominid bones. Nobel Prize–winning ethologist Konrad Lorenz (1966) explained that we have an innate aggressive drive requiring discharge, and a triggerable program of “militant enthusiasm” to express it. Robert Ardrey (1961:322–323; 1968) crafted the verdict of science for popular consumption: we are “Cain’s children,” “bad-weather animals” born with a “territorial imperative,” and “a natural instinct to kill with a weapon.” We are “killer apes”—but that is a good thing. It made us “free of the forest prison” which still confined our primate cousins. That story went large. In 2001: A Space Odyssey, when those obelisk-apes started killing each other—that was us. Lord of the Flies lies lurking within all men.

Is war an expression of human nature? Of course, no question. People do war. It’s a human thing, mostly a men’s thing. The question is what kind of nature paves our roads to war? On that, anthropologists split between “materialists,” who see war deriving from practical interests in resources and power, and “symbolists,” who see war as acting out scripts of cultural value systems. Both stances make assumptions about human nature, what makes us tick and why we do what we do, but neither suggests that people are born predisposed to war.

Another approach asserts exactly that. “Biological” or “evolutionary” theories claim that humans are not just capable of war, but that we naturally lean into it, we seek it out. Men are innately primed to kill outsiders. Specific wars are culturally molded expressions of a species tendency, which evolved because it promoted male reproductive success in our evolutionary past. That is the ultimate causation behind all proximate causes of war. Born-to-kill tendencies are proposed in countless variations (see Milam 2019), but a touchstone for many is modern research on chimpanzees, Pan troglodytes.

Do chimpanzees make war? Until the 1970s nobody thought so. Then at Gombe National Park in Tanzania, over four years a group of chimpanzees stealthily patrolled their borders, entered a neighbor’s rangeland, and sometimes attacked and killed single individuals. Eventually the targeted group was gone, and the attackers ranged in their territory. Since then, deciding whether chimpanzees make war depends on one’s definition.

I always opted for a minimalist definition of war: collective and potentially lethal action by members of one group, directed against people outside that group (Ferguson 1984:5). By that minimal definition, chimpanzees can make war. But in that definition, I was thinking about people only, and so took much for granted, starting with complex and layered group social and political dynamics, and symbolic configuration of enemies that makes killing them acceptable and meaningful. My definition assumed the presence of culture (see Chapter 30). To anticipate my conclusions, chimpanzees are not cultural, which makes chimpanzee “war” essentially unlike human war. For clarity, their “war” is put in quotes.

I am not a primatologist. As an anthropologist of war I was drawn into the chimpanzee literature very reluctantly, because of prominent assertions that we cannot understand war without recognizing its evolved biopsychological substrate, supposedly shared by chimpanzees and people. Some version of “the first step in controlling war is understanding its biological roots” has been the refrain ever since Lorenz and Ardrey. We humans are born with predispositions to kill outsiders, irrespective of any immediate material needs or competition. This is the initial message from Jane Goodall’s work at Gombe. It is the central point in Richard Wrangham and Dale Peterson’s Demonic Males, and countless other publications.

The basic idea is that males of both species are naturally inclined to kill outsiders when there is little risk involved to themselves. Males are primed to seek opportunities to kill because in our evolutionary past that enhanced males’ access to resources and females, and so enhanced reproductive success. Although advocates of this perspective invariably note qualifying, complicating, and modifying factors of culture, their main point is that ultimately, war is man’s nature.

Wrangham (2005:18) puts this bluntly in Harper’s Magazine, following a discussion of war by human hunter-gatherers:

The principle that underlies the mayhem is simple: When the killing is cheap, kill. In any particular instance it may or may not lead to a bigger territory, but from the perspective of natural selection, killing need only lead to benefits sufficiently often. Just as the first male fig wasp that emerges from pupation will immediately attempt to kill any other males he finds in the same fig, so humans, chimpanzees, and wolves benefit by killing rivals when it’s reasonably safe to do so. The killers may think of their action as revenge, as a rite of manhood, or as placating the gods–or they may not think about it at all. They may do it simply because it’s exciting, as seems to be the case for chimpanzees. The rational doesn’t matter to natural selection. What matters, it seems, is that in future battles the neighbors will have one less warrior.

Chimpanzees, War, and History: Are Men Born to Kill? challenges that perspective. It shows that Pan territorial behavior and intergroup relations vary greatly by circumstance, and sometimes include intergroup mixing and toleration. Intergroup killings of adults are few, and mostly limited to just two situations. Border patrolling is a pattern in only a minority of study sites. Adult males that disappear cannot be presumed dead, much less killed by outside chimpanzees. Chimpanzees have killed as many within their own groups as outsiders. Many other canonical “facts” are similarly contested.

My alternative explanation is that most killings are attributable to anthropogenic change. Killings are not a “normal” expression of evolved reproductive strategies, but situational reactions to specific human disturbance. That is my main argument. Along with human impact, another partly overlapping hypothesis is that killings of defenseless individuals can be related to “political” circumstances within groups. Supporting both those hypotheses with evidence is the task of this book.

The bottom line is that chimpanzee males are not innately predisposed to kill outsiders. To understand where, when, and why they kill, violence must be historically situated in the realities of its time and place. If that is done, the lesson of chimpanzees is that they, like people, are not inclined to war.

Many times a human disturbance explanation has been pronounced dead. The debate is called settled, closed. Killing it is said, is proven beyond reasonable doubt to be an evolved adaptive strategy, not seriously affected by human activities (Wilson et al. 2014a). That proclamation does not stand against the evidence presented here.

This is not an attack on evolutionary explanations but rather an argument for a different perspective on evolution. Humans are animals. Our minds and capacity for culture are ultimately the product of evolution. The question is, where has evolution brought us? To specific violent predispositions—what some still call instincts—or to open coping, with nature and nurture interacting? I argue that deadly violence is but one expression of behavioral plasticity. Many primatologists will say “of course!” Some—more than a few I hope—will agree with positions in this book. But as Part I and subsequent chapters show, that is not primatology’s often proclaimed message to the public.

Who am I, an anthropologist, to contest theory about chimpanzees with researchers who spent years observing in the field? I do not know a single chimpanzee personally. Yet I have been immersed in this literature for over 20 years. Why do primatologists publish research findings if others cannot evaluate their findings independently? In science, theories and evidence must be subject to scrutiny and debate.

The book has ten multichapter Parts. Part I sets up everything to come. It shows how the idea of ape and human demonism—the Gombe paradigm—arose; and lays out major theoretical positions, both within primatology and my own. Parts II through VII go deep into all field observation sites: II Gombe, III Mahale, IV Kibale, V Budongo, VI eleven “smaller” cases across Africa, and VII Tai. Each considers every killing reported or suspected, and contextualizes every one within local history of human disruption and status politics. Part VIII about bonobos examines their territoriality and intergroup behavior; offers a social evolutionary explanation for pattern differences between them and chimpanzees, with the latter enabling violence and killing as political display; and considers nature–nurture interactions in hormonal and other biological characteristics in light of recent developments of evolutionary theory.

The final two Parts are synthetic. Part IX evaluates all that came before, first in two chapters that deconstruct demonic and broader adaptive explanations; beginning with sexually selected infanticide in Chapter 27, then moving to attacks on adults in Chapter 28. Chapter 29 rebuts critiques of human impact explanations and summarizes abundant supporting evidence. Throughout Part IX, special attention goes to refuting recent and widely cited claims that “Lethal aggression in Pan is better explained by adaptive strategies than human impacts” (Wilson et al. 2014a).

Part X wraps up with the biggest question of all, why do people make war? Chapter 29 evaluates all the proposed applications of chimpanzee analogies to human warfare, and finds them less than illuminating. Chapter 30 provides the foundation of my own unifying, species-specific anthropological theory of war, based on two fundamental differences between Pan and Homo. On that foundation, Chapter 31 outlines many ways I have employed that theory, to explain why war happens, the war patterns of particular societies, and actual decisions to go to war. That leads to a closing comment on my subtitle, “Are Men Born to Kill?”

Readers will approach this book from different angles. Researchers will want to scrutinize all the fine points; people just interested in chimpanzees or conservation may skim to get on with the main story; and those most concerned with innate tendencies to war will go for the theoretical discussions and evidentiary summaries (Part 1, Chapters 4, 8, and 26, Parts IX and X). Wherever possible, the narrative is simple and straightforward, with more technical but necessary points discussed in extensive footnotes. But often detail is required in the main text, to challenge existing positions or construct new ones. To avoid any appearance of cherry picking, the text presents a complete record of reports of even suspected killings, from published research on all major research sites, from initial observations to 2021. All this detail is necessary because Chimpanzees, War, and History aims to overturn a disciplinary consensus which concludes that killing is adaptive, and to substantiate a human impact explanation often declared disproven. That is why this book is so comprehensive and detailed, and why it took so long to research and write (and read).

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments are difficult for a two-decade project. I have talked ideas through with many, many people, some whose names I never knew, and surely will not remember even all who were the most involved. Those I omit, I do apologize.

First are my loving and patient wife Leslie Farragher who put up with thousands of “I’m working,” listened attentively every time I went on about something I’d just read, and always encouraged me; and my inspiring daughter Elise Ferguson who literally grew up with this book and inspires me with her smartness and moral commitment. Those two made this long journey possible, and Leslie checked my numbers and made the tables. My larger family also heard about it so many times, and believed in me (even though I’ve been saying “it’s almost done” since 2004): sister Kate, her husband Bob Hirsh, son Ian Ferguson and his husband Ryan Brandau; sister Margaret, husband Mitch Kleinman and children Ben and Alex; brother Phil and his wife Linda; brother Bob, wife Diane, and anthropologist son Michael, with Kathy, not forgetting Charlie and Greer; and in-laws Carla Farragher and Mike McCrobie. To them all—the next book on the origin of gangsters in New York won’t be so bad.

Friends and colleagues who listened and asked clarifying questions include Claudia Amos, Connie Anderson, Pat Antoniello, Gay Bradshaw, Antonio Campos, Charlotte Cerf, Aldo Civico, Ira Cohen, Steve Daley, Chris Duncan, Jeff English, Brian Felicetta, Frank Fischer, Steve Franklin, Douglas Fry, Agustin Fuentes, Rosa Gonzales, Brian Grant, Jonathan Haas, Clay Hartjen, Carol Henderson, Haram (Adam) Henriquez, Alex Hinton, John Horgan, Peter Kincl, Kate Korten, Chris Kyle, Jamie Lew, Jonathan Marks, Bill Mitchell, Sean Mitchell, Bryan Muldoon, Zoe Ngonyama, Hank Penza, The Phantom, Barbara Price, Steve Reyna, Nicole M. Rivera, Isaias Rojas-Perez, Dolores Shapiro, Kurt Schock, Genese Sodikoff, Leslie Sponsel, Allen Steinhauer, Bob Sussman, Joel Wallman, Alisse Waterston, and Maxine Weisgrau. Again, apologies to those left out. A special category is my high school friends, the Delmartians, who check in on progress when we get together every year, always interested and encouraging: Yael Harris, Tim Hewitt, Rob Longley, Janet Mattox, Richard Oldreik, Dick Phelan, Stephen Phelps, Molly Reynolds, Chris Rosaria, and Scott Vonnegut. Two graduate students did most of the bibliography, Alea Rouse and Michael Toomey—thank you! John Driscoll, Joy McDonald, and Dawn Wilson helped keep me going many times. I am grateful to the fabulous librarians at Rutgers—their interlibrary loan can find anything; and to the undergraduate and graduate students at Rutgers University-Newark, especially in the Master’s Program on Peace and Conflict Studies, who heard many of these ideas and asked good questions. It would be remiss to leave out the crews and customers who respected my odd work habit of writing at local bars, and also asked good questions.

The Rutgers University Research Council twice stepped in with important funding when it was really needed.

A special debt is owed to Elizabeth Knoll, formerly at another press. We could not bring the book to publication together, but for years as my editor she encouraged me, asked pointed questions, and made my writing better. This book project might have gone nowhere without her encouragement and editorial advice.

Part I: Controversies

1. From Nice to Brutal

How did chimpanzees get such a killer reputation? Where did the idea come from that people get their mean streak from apes? It wasn’t always that way. Understanding the construction of our image of chimpanzee violence is the first step in evaluating scientific claims about humanity’s supposedly lethal heritage.

An Image of Peace

Robert Ardrey, who called people “killer apes,” had a much nicer opinion of chimpanzees. In being deadly dangerous, humans were different from forest apes, “non-aggressive vegetarians” condemned to “eternal munching.” Although chimpanzees were hostile to neighbors, they “maintain each other’s exclusive space by avoidance,” not killing (Ardrey 1961:322–323; 1968: 245). In a public discussion with Louis Leakey, Goodall’s mentor, Ardrey said that clashes between primate groups were mere “charades,” just stimulating “fun.” Leakey, referring to reports from Gombe, said that the only serious aggression there was between baboons and chimpanzees in the “contrived situation” of banana feeding (Leakey and Ardrey 1971:16–17). Ashley Montagu (1968:12) wrote that studies of wild primates, including Goodall’s, “show these creatures to be anything but irascible. All the field observers agree that these creatures are amiable and quite unaggressive, and there is not the least reason to suppose that man’s pre-human primate ancestors were in any way different.”

Pioneering field studies of chimpanzees seemed to confirm this pacifistic orientation, or go even farther. From his own early observations in Budongo forest and other reports, Vernon Reynolds (1966:444; also Sugiyama 1968) concluded that chimpanzees lived in open groups, that they “recognize and tolerate other individuals in a network of acquaintances extending beyond any local community,” and that old acquaintances reunite with “affectionate greeting.” This he saw as the evolutionary template for hominid social organization.

Goodall (1986:503) recognized that her studied chimpanzees fell into “northern and southern ‘subgroups’ ” where individuals spent most of their time, but thought there was no barrier between them or even beyond. Chimpanzees had open unbroken networks, with strangers being excitedly welcomed among them.

Since chimpanzee groups in the reserve freely unite from time to time without signs of aggression, they cannot be divided into separate communities. It seems likely that only a geographic barrier would constitute a limiting factor on the size of a community, although individuals living at opposite ends of the range might never come into contact. (Goodall 1965:456–457)

One of these “reunions” of separate groups is a central event in her first National Geographic (1967) special, “Miss Goodall and Her Wild Chimpanzees.”

Another pioneer, Toshisada Nishida (1968:167) broke with this consensus by reporting that at Mahale in Tanzania, groups with overlapping territories were closed and antagonistic. Yet the “inter-unit-group interaction is peaceful; the subordinate unit-group avoids the dominant one” (Nishida 1980:21)—as Ardrey said.[1]

Goodall was the great communicator about chimpanzees. Her message was that chimpanzees are like humans, and humans like chimpanzees (Lehman Haupt 1971; Stade 1972; Scarf 1973). In regard to war however, at first there was no comparison.

Two neighboring communities of chimpanzees may occasionally indulge in displays of power as individuals hurl rocks and wave branches or even briefly attack one another. But they show nothing even remotely comparable to the horror of human warfare. (van Lawick-Goodall 1973a:11)

“[C]himpanzees, though very much like us in behavior, were rather nicer” (Goodall with Berman 1999:111).

The Great Revision

That image shattered during what Goodall (1999:127) named “the Four Year War” at Gombe. First, the Kakombe community split into northern (Kasakela) and southern (Kahama) groups. Then, from 1974 to 1977, Kasakela males deliberately, brutally attacked members of the southern group, beating, biting, and sometimes killing those they caught, until none were left. Then Kasakela chimpanzees began to forage in their old range—they took Kahama’s land! This was stunning news. Chimpanzees could brutally kill other chimpanzees. Like men. “Sadly, the ‘noble ape’ was as mythical as the ‘noble savage’ ” (Goodall with Berman 1999:112).

These developments along with findings from Mahale, led to what I call the Great Revision, totally changing our picture of chimpanzee groups and interactions between them. Post-revision, it seemed that early observers were misled by the messy way daily parties of chimpanzees continually break up and reform in new combinations (Ghiglieri 1984:8, 173–174). That masked the existence of hostile, territorially exclusive communities that defined the limits of this “fission/fusion pattern” of association. With little further consideration, the earlier views of wide-ranging sociality were consigned to the dust bin, disappearing from the master narrative of belligerent chimpanzees.

Human Influence

It took time to make any sense of these attacks, and interpretation went through two very different phases. The first is registered in a paper written by Goodall et al. (1979) and seven associates at Gombe. They start with an idea from David Bygott, a doctoral student who did much of the chimpanzee following away from the field station in the early 1970s. “Bygott (1974) has put forward a theory that increasing agriculture outside the boundaries of the park may have driven more chimpanzees into the area, thus increasing their density. This is plausible . . . If the theory is true, it might account for an increased aggressiveness between males of different communities.” However, “it does not seem to us that there is enough overcrowding to account for the severity of the three attacks perpetrated by the Kasakela community against Kahama males” (Goodall et al. 1979:42, 51).

Elsewhere Goodall (1977a:272–273) is even more clear about the impact of human encroachment. “We do not understand this violent behaviour.” But she had good idea. Recent cultivation around the Park may have pushed a large group, later called Kalande, into Kahama’s rangelands.

It is possible that this large community may have moved into the Park from outside and that the density of the chimpanzees within the Park has, therefore, increased. … So far as we can tell, there is, as yet, no serious overcrowding of the chimpanzees at Gombe. Nevertheless, with the encroachment of another large community, there is increasing likelihood of encounters between males of one community and individuals of another.

Human interference was considered as a likely, though not complete, explanation of intergroup violence. Commentators said that “rigorous testing” of the effects of crowding on aggression would need to be done in the future (Trudeau et al. 1981:38). That never happened. The idea that external habitat loss led to crowding within the Park and so to intergroup aggression kept on in a few research publications (Goodall 1983:6; 1986:49–50; Williams et al. 2008:774). But in the theory and master narrative of Gombe, the point rarely surfaces.

Human impact was not limited to habitat impaction. Much fighting occurred over provisioned bananas. The feeding chaos was so intense that research almost ended. Teleki, at Gombe in the late 1960s, believed that the provisioning drew southern chimpanzees northward, to concentrate around the feeding station (Nishida 1979:117). Reynolds (1975) titled an article “How Wild Are the Gombe Chimpanzees?” Margaret Power (1991), the most important critic of the idea that panicide was “natural,” argued that changes in banana provisioning were responsible for the violence between Kasakela and Kahama. That is not the direction Goodall’s thinking would take, nor researchers after her.

Although Goodall never credited banana competition as a cause of intergroup violence, she emphasized conflict over resource territories. With Kahama eliminated and the Kasakela chimpanzees occupying their range, recovering what had been lost became her immediate explanation of the fighting (Goodall 1977b). “The most likely cause of the Four-Year War at Gombe was the Kasakela males’ frustration at being denied access to an area over which they had roamed until it was occupied by the breakaway community” (Goodall with Berman 1999:127–128). Yet resource competition alone was not seen as enough to explain the intensity of attacks.

Tilting toward the Dark Side

Goodall felt that the severity, the brutality of the attacks on chimpanzees that for years had lived together and socialized, had more disturbing implications. In National Geographic (Goodall 1979:594), she told the world that chimpanzees “had their own form of primitive warfare,” and they used it to acquire territory. The caption for an illustration of “warmongering apes” ended with a hint of the perspective to come: “Whatever the reason, the events point up dramatically an aspect of chimpanzees behavior that she finds disturbingly similar to the darker side of human nature” (1979:611; and see Goodall with Berman 1999:117).

Dark Times

Goodall’s view of human nature itself took a sharp turn for the worse at this moment. The mid-1970s was a time of human war near to Gombe. Across Lake Tanganyika in Zaire, Goodall sometimes saw villages in flames. Refugees came in from Burundi. In May 1975 rebels from Zaire crossed the Lake and kidnapped four student researchers, three of them from Stanford University, which had become the sponsor of the Gombe Stream Research Center (New York Times 1975). It took months of seriously strained relations between Stanford and the Ugandan government to get all the captives back. Goodall was enmeshed in nasty fights and recriminations (Peterson 2006:556–557, 567–568). Much of her energy and resources went to countering these criticisms. That was her personal low point. “I only mention it here because it was so devastating at the time, and because it taught me so much about human nature.” “What a horrible commentary on human nature” (Goodall with Berman 1999:104–105).

Besides having a profound impact on Goodall personally, these events marked the “end of an era” in Gombe research (Goodall with Berman 1999:105). Her teaching position at Stanford ended, funding dried up, and the Tanzanian government greatly restricted her or any outsiders’ access to Gombe. In 1976 wealthy friends helped establish the Jane Goodall Institute. Research revived, but for some time would rely primarily on trained Tanzanian observers rather than graduate students.

Goodall tells us that this sudden, dramatic reversal of fortune had a profound effect on her view of human nature. It happened at the same time she was trying to make sense of the Four Year War—and an array of other shocking violence among Gombe chimpanzees. Goodall refers to this period as “Paradise Lost,” “my world turned upside-down” (Goodall with Berman 1999:97).

Meanwhile, events at Mahale, about 160 km to the south in Tanzania, added to the darkening picture. Antagonistic interactions but not serious violence had been observed between two chimpanzee communities: K-group, the initial focus of study, and the larger M-group to its south. Several K group males disappeared over the years with researchers making little of it. After word of the Gombe events spread, Nishida and colleagues thought again. Those and subsequent disappearances were reinterpreted as possibly being killings. Ultimately, with more male disappearances, K-group was gone (Nishida 1980; Nishida et al. 1985).

Many researchers concluded that at two research locations, one chimpanzee community “wiped out” another. Interpretive caution did not rule. For many, by 1985 the verdict was in: the Four Year War was no aberration. It is in the nature of chimpanzees to make war, to conquer territory—just like humans (Ghiglieri 1988:258–259; Goodall 1986:519–522).

Goodall’s Theory

In her magnificent opus The Chimpanzees of Gombe—a true masterpiece of scholarship—Goodall (1986) mapped out the dark side. Chimpanzees had behavioral tendencies that they shared with human beings, which were “precursors” for human warfare. First, they are territorial.

In the chimpanzee, territoriality functions not only to repel intruders from the home range, but sometimes to injure or eliminate them; not only to defend the existing home range and its resources, but to enlarge it opportunistically at the expense of weaker neighbors; not only to protect the female resources of a community, but to actively and aggressively recruit new sexual partners from neighboring social groups. (Goodall 1986:528)

Second, chimpanzees, especially young males, are “often strongly attracted to intergroup encounters, even to the extent of approaching a number of potentially dangerous neighbors.” They are excited by it, they seek it out. “[I]if early hominid males were inherently disposed to find aggression attractive, particularly aggression directed against neighbors, this trait would have provided a biological basis for the cultural training of warriors” (1986:531).

Third, they have “an inherent fear of, or aversion to strangers, expressed by aggressive attack” (1986:531). Yet there is something more complicated here than simple xenophobia. They can draw a line cutting off known individuals, former companions, as Kasakela did to Kahama, in a deadly divide. When Kasakela males attacked, their behavior demonstrated an “intent to kill.” “If they had firearms and had been taught to use them, I suspect they would have used them to kill” (1986:529, 530). Chimpanzees outside the group “may not only be violently attacked, but the patterns of attack may actually differ from those utilized in typical intracommunity aggression. The victims are treated more as though they were prey animals; they are ‘dechimpized,’ ” just as humans dehumanize their enemies through a process of “pseudospeciation” (1986:532).

Years later, after the horrifying human wars of the 1990s, Goodall (with Berman 1999:131) brought the point home. “Our tendency to form select in-groups from which we exclude those who do not share our ethnic background, socioeconomic position, political persuasions, religious beliefs, and so on is one of the major causes of war, rioting, gang violence, and other kinds of conflict.” All of that violence is largely due to the fact that humans share with chimpanzees a tendency to attack and kill members of other groups.

A new paradigm was being born. Not one developed from many researchers working over years on related problems, but from a few startling observations, rapidly reinforced by other events at Gombe and Mahale, and impressed on all the primatologists who would follow.

Jane Goodall is a hero. From humble beginnings, she dared to open up a new field of research. With courage and determination—with pure grit—she overcame self-doubt, physical hardship, malaria, a plane crash, professional scorn, a terrifying night raid, wrenching emotional turns, financial reverses, and personal tragedy. This young, former secretary made the most momentous discoveries in the history of chimpanzee research—that they make and use tools, that they hunt, and that in their emotional and behavioral range they closely resemble human beings. With these three discoveries, she changed forever our cherished notions of human uniqueness within the animal kingdom.

Goodall conducted superb research on many aspects of behavior, and organized a much larger project that resulted in one of the finest monographs of 20th-century science. Perhaps most extraordinary, in The Chimpanzees of Gombe, she faithfully presents information that does not seem to support her own ideas. When she turned from research to activism, she became the world’s conscience about human abuse of chimpanzees. For decades she has worked tirelessly to promote natural conservation and peaceful cooperation among people, even busier during Covid with televisits. She built an organization, The Jane Goodall Institute, that has been a crucial moving force behind many chimpanzee protection programs, as seen repeatedly in this book.

In 1991, from her front porch in Tanzania, she began “Roots and Shoots,” a youth empowerment network. It has operated around the world (Pusey et al. 2007:626), in all 50 US states and over 60 countries. “Since 1991, millions of students have taken on the challenge of making the world a better place for people, other animals and the environment we share. Roots & Shoots youth are not only the future—they are the present—and they are changing the world” (https://www.rootsandshoots.org/about-us/). Goodall is an incomparable role model for young people, especially but not limited to girls (Greene 2005). In 2002 Secretary-General Kofi Annan appointed her a United Nations Messenger of Peace (Hunt 2002:303). Her brilliant ideas in conversation with Douglas Abrams in The Book of Hope (Goodall and Abrams 2021) show not only great knowledge, from individual lives to planetary scale, but also wisdom. Wise hope is very scarce today. The world needs Jane Goodall.

But Dr. Goodall began her career as a scientist, and became one of incalculable influence. I treat her with great respect, as a scientist. It would be a disservice to do otherwise. Science progresses as new ideas are evaluated against new theory and evidence. There has been a lot of both since she gave up active chimpanzee research in the 1980s. All of that is included in this book.

2. The Second Generation

Sociobiology

There was another important development in the middle 1970s, not in chimpanzee behaviors, but in evolutionary theory to explain those behaviors. The year 1975, the middle of the Four Year War, saw the publication of E.O. Wilson’s (1980) extremely influential and controversial Sociobiology: The New Synthesis.

Inclusive fitness theory explained many aspects of animal and human behavior as strategies designed by evolution to maximize an individual organism’s genes in future generations. For males–which were the focus of most theorizing about primates and human origins (see Haraway 1989)—specific behaviors were selected for because they increased access to females, and/or increased food resources, which enabled reproductive success. Since close kin shared genes, nepotistically helping them helped to pass along those shared genes, selecting for behaviors favoring kin, or kin selection. Everything came down to the currency of maximizing genes in future generations.[2]

Goodall’s findings were not inconsistent with the emerging field of sociobiology, but she was not a sociobiologist. She believes “it is pointless to deny that we humans harbor innate aggressive and violent tendencies,” and scorns those who say those are all learned. Yet she pointedly distances herself from those who emphasize the calculus of reproductive success, singling out Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene. “Sociobiological theory, while helpful in understanding the basic mechanism of the evolutionary process, tends to be dangerously reductionist when used as the sole explanation of human—or chimpanzee—behavior” (Goodall with Berman 1999:141). Inclusive fitness approaches “provided an excuse for human selfishness and cruelty. We just couldn’t help it . . . . [Referring to Nazi Germany, she asks, did] Dawkins’s theory help to explain how, in a supposedly cultured, civilized country, mass killing and genocide on such a scale could have taken place?” (1999:119–122). Goodall’s point is that tendencies to war are innate—not that humans or chimpanzees follow an inborn calculus for maximizing genetic success.

Settling In

Goodall was the beginning, not the end, of theory about chimpanzee war and its relevance to humans. Elaborating the evolutionary rationale behind “demonic males” would be taken up by the next generation of chimpanzee researchers, some of them students of Goodall, and they would line up with Dawkins. Ghiglieri (1987) describes the spread of this perspective, explaining how it “plumbed the roots of social structure by seeking to explain it as a result of adaptations to maximize the reproductive success of the social individual.” Despite arguments, “it is generally agreed that social systems have evolved to maximize the reproductive success of individuals in them” (Ghiglieri 1984:2–3). Wrangham’s approach was close (1982a), with some differences.[3]

Where does human violence come from, and why? Of course, there have been great advances in the way we think about these things. Most importantly, in the 1970s, the same decade as the Kahama killings, a new evolutionary theory emerged, the selfish-gene theory of natural selection, variously called inclusive fitness theory, sociobiology, or more broadly, behavioral ecology. Sweeping through the halls of academe, it revolutionized Darwinian thinking by its insistence that the ultimate explanation of any individual’s behavior considers only how the behavior tends to maximize genetic success: to pass that individual’s genes into subsequent generations. The new theory, elegantly popularized in Richard Dawkins’s The Selfish Gene, is now the conventional wisdom in biological science because it explains animal behavior so well. It accounts for selfishness, even killing. And it has come to be applied with increasing confidence to human behavior, though the debate is still hot and unsettled. (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:22–23, my emphasis)

Throughout this book, I will occasionally refer to “sociobiology.” I understand that few primatologists today would use that label for their own work. But the main theory of chimpanzee violence was built on that foundation, and for many explanations, the foundational theory has not changed.

Scientific Methods

Along with the new theories came a new methodology, focused on formulating and testing narrow hypotheses (McGrew 2017:240–242). Goodall exemplified an older, ethnographic, or natural history approach.

Natural history data were the focus of primatology until the 1970s and 1980s, when there was a major shift toward hypothesis-driven research (the collection of a limited set of data used to test specific hypotheses) . … As a result of this shift, natural history data are currently undervalued, and it can be challenging in primatology (and other biological fields) to obtain funding specifically for the collection of broad behavioral and ecological data and to get natural history information published in leading primatological journals (Campbell et al. 2007:703; cf. McGrew 2017:240–242).

That shift is very apparent in this book, for instance in the more restricted information we got about Gombe after Goodall withdrew from field research around 1981.

The New Mindset

By the end of the 1970s, the Four Year War was being reframed in terms of hypotheses about genetic relatedness and reproductive striving. Researchers who had done Gombe fieldwork before the kidnappings proposed that relations between males of different groups were fearful and hostile because males of one group shared common genetic interests, while they competed with less related males of other groups. It was a matter of inclusive fitness (Bauer 1980:117–118; Wrangham 1979a:358).

If it is normally true that the larger party wins the encounter then the community which can most frequently form large parties will achieve territorial gain at the expense of its neighbours . . . the functional consequence of territorial expansion was the acquisition of females, since there is some evidence that they do not always follow a retreating male community. If so, we may view the formation of large parties as improving the reproductive success of a male community . . . (Wrangham 1977:536).

Bygott (1979:423) proposed that because of this reproductive advantage, “there would be strong selection for males to be rapidly aroused to attack strangers, particularly males on sight.”

Wrangham, who would be the most thoughtful, prolific, influential, and provocative theorist on chimpanzee intergroup violence, made the most important contributions toward the adaptive explanation of male belligerence. Much of my disagreement in this book is with his theory. At Gombe he (1977; 1979b) concluded that females ranged alone or with offspring in the center or core of a territory; while males roamed in larger parties over a larger area.[4] The larger range of males surrounding the females, he deduced, enabled males to pursue their own internal political alliances, and simultaneously protect the females from stranger males. The alliances were for reproductive success (Wrangham and Smuts 1980:30).

Interference Mutualism

Deepening the evolutionary selfishness, Wrangham brought in a new principle, interference mutualism. Mutualism occurs when two organisms both benefit by participating in the same behavior at the same time (Clutton-Brock 2009). With chimpanzees, hunting will an example. Single hunters have less chance of catching a monkey than if several try at once. Many have written about mutualism across the animal kingdom as a powerful selective force—those who cooperate both directly benefit (Fry 2018; Sussman and Chapman 2004; Sussman and Cloninger 2011; Sussman and Garber 2004; Sussman et al. 2005; Zihlman and Bolter 2004; cf. Lawler 2011; Sussman et al. 2011).

But as the demonic perspective was being formed, in the salad days of sociobiology, mutualism itself was seen not just as a path to mutual benefit, but also as a way to harm others. “Non-interference mutualism” (NIM) confers benefits to all those participating in a behavior. “Interference mutualism” (IM) confers rewards on cooperators, but also imposes costs on others. IM is expected among genetically related individuals, against nonrelatives. Interferers would thus prosper at the expense of generally cooperative noninterferers. Relatively more of their genes would be passed along (Wrangham 1982b:272–273). This could be the origin of “us” vs. “them.” This is the sort of “hard truth” on which sociobiology thrived.

If true, “individuals should associate with their closest possible relative at all times . . . stable groups of considerable size may develop. Relationships between these groups would normally be aggressive, unlike those between NIM groups” (1982b:274). Within-group conflicts should be limited in violence. “For example winners should refrain from killing defeated rivals . . . Aggression between males of different communities, however, can lead to serious injuries and deaths” (1982b:282).

Building a Theory

A related concept was already in wide use: coalitional aggression. “In ethology, a coalition is defined as cooperation in an aggressive or competitive context . . . the interests of the cooperating parties are served at the expense of the interests of a third party. It is this well-coordinated ‘us’ against ‘them’ character that sets coalition formation apart from other cooperative interactions among conspecifics” (de Waal and Harcourt 1992:2). Goodall (1986) uses the concept frequently in regard to mostly nonviolent conflicts within the group. It was easily applied to intergroup attacks and killings.

By the later 1980s, Wrangham acknowledged that “the value of biology for an understanding of warfare is still a matter of faith” (1988:79). But he was still building. He drew comparisons between intergroup violence among chimpanzees and human hunter-gatherers, arguing that both species shared a common ancestor with “closed social networks, hostile and male-dominated intergroup relationships with stalk-and-attack interactions” (1987:67–71). One statement from this time is crucial for the theory to follow: “The implication from these studies is that natural selection favors unprovoked aggression provided that the target is sufficiently vulnerable, even when the benefits are not particularly high” (1988:81).

Michael Ghiglieri was a graduate student closed out of Gombe in the aftermath of the 1975 rebel raid. He initiated chimpanzee observations in Kibale, Uganda. In 1987 and 1988 Ghiglieri, published a popular article and book supporting the sociobiological explanation of “War among the Chimpanzees,” emphasizing its similarity to human warfare. “Primitive hunting and gathering societies the world over exhibit . . . territorial defense and warfare basically identical in form and function to that of chimpanzees” (1988:259; 1987).

The Imbalance of Power Hypothesis

In 1991, different ideas gelled into a major hypothesis (Manson and Wrangham 1991). The imbalance of power hypothesis (IoPH) grew out of the authors’ long-standing interests in social organization across the primate order. It stressed the importance of two structuring conditions: male philopatry, and fission/fusion association within a group.

Key Concepts and Big Splashes

Male philopatry means that while most chimpanzee females migrate to another group after they reach sexual maturity,[5] males remain in their group of birth. (This generalization is substantially qualified in chapters to come.) A group’s males, it was thought, were more genetically related than the group’s adult females, mostly immigrants. Males thus are seen as likely to act in concert against the male mini-gene-pool of the next group. “If generations of males remain true to the territory of their natal community, then they will be more closely related to one another than to the immigrant females or to the average chimpanzee in their population. Solidarity between these males is predictable on the basis of increased inclusive fitness and kin selection” (Ghiglieri 1984:4). “The hypothesis [is] that the more closely related males form a kin group that cooperates to defend a territory, thereby increasing access to females and resources” (Morin et al. 1994:1195).

The fission-fusion pattern means that within a “unit-group” or larger community, daily foraging groups range from individuals to large parties, continually breaking up and coming together in new combinations.[6] Combining male philopatry and genetic relatedness was inferred to mean that sizable parties of gene-sharing males from one group occasionally encounter a solo genetic competitor from a neighboring group. In the developing adaptationist perspective, this combination set the evolutionary stage for lethal xenophobia and war.

Examination of comparative data on nonhuman primates and cross-cultural study of foraging societies suggests that attacks are lethal because where there is sufficient imbalance of power their cost is trivial, that these attacks are a male and not a female activity because males are the philopatric sex, and that it is resources of reproductive interest to males that determine the causes of intergroup aggression. (Manson and Wrangham 1991:369)

Male chimpanzees are said to be genetically predisposed to kill outside males whenever they can do so with impunity—and human males are too.

This perspective achieved much greater prominence in 1996, with Wrangham and Peterson’s Demonic Males: Apes and the Origins of Human Violence. The “demonic” human male represents one point on a broader great ape spectrum, in the nasty things they do in pursuing genetic selfishness. “We think about this as being demonic male behaviour because, of course, females don’t do it” (Wrangham quoted in O’Connell 2004). Then Ghiglieri (1999) published The Dark Side of Man: Tracing the Origins of Male Violence, with a similar explanation of men behaving despicably.[7]

Specifying an Urge to Kill

What, exactly, does the imbalance of power hypothesis claim about chimpanzees and humans?

We must start with a significant complication, the label “imbalance of power” itself. One ordinary understanding of that label is uncontroversial: whatever the issue, chimpanzees or humans are less likely to attack others when they lack a numerical advantage, and more likely to attack with one. I fully agree that both species normally abide by such elementary calculations. But the imbalance of power hypothesis as advocated by Wrangham and others goes much further than that.

The imbalance of power hypothesis attributes a murderous proclivity to male chimpanzees and humans. Both have “an appetite for lethal raiding,” “a hunt-and-kill propensity” (Wrangham 1999:1, 5), both “are wont to kill adult neighbors” (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:165). “For humans, chimpanzees, and wolves it makes sense to kill deliberately and frequently” (Wrangham 2005:18). “Chimpanzees, our closest ape relatives, also have a tendency to organize into coalitions of related males to defend shared territory and to kill their enemies” (Wrangham 2005:15).

This inborn propensity makes male chimpanzees act “as a gang committed to the ethnic purity of their own set” (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:14). The suite of associated behaviors includes collective border patrols and at other times avoidance of border areas, deep incursions into enemy territory, and coalitionary attacks and kills (Wrangham 1999:6).[8] Intergroup violence as at Gombe is said to be confirmed by research elsewhere as normal (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:12). “[I]ntergroup aggression, including lethal attacks, is a pervasive feature of chimpanzee societies” (Wilson and Wrangham 2003:364).

Does this mean chimpanzees are naturally violent? … Alas, the evidence is mounting and it all points the same way. … In this cultural species, it may turn out that one of the least variable of all chimpanzee behaviors is the intense competition between males, the violent aggression they use against strangers, and their willingness to maim and kill those that frustrate their goals. (Wrangham 1995:7)

“It’s in the nature of chimpanzees to kill” (Wrangham 2006:48).

Sufficient to Kill

A crucial part of this model is that intergroup violence and killing among chimpanzees is not linked to any immediate resource scarcity or competition. Action depends, instead, on the ability to kill without risk of serious injury (Wrangham 1999:14–16) “[U]nrestrained attacks on opponents are favored merely because their cost is low,” “attacks will be restricted to occasions of overwhelming superiority” and “will occur whenever the opportunity arises” (Manson and Wrangham 1991:371, 385). “[A] necessary and sufficient condition for intercommunity aggression is a perception that an opponent is sufficiently vulnerable to warrant the aggressor(s) attacking at low risk to themselves” (Wrangham 1999:14). “[N]o resources need be in short supply at the time of the raid. Instead, unprovoked aggression is favored by the opportunity to attack ‘economically,’ that is at low personal risk” (Wrangham 1999:15; and see Wilson and Wrangham 2003:381). “In theory, killing might be a response to competition: but there’s no indication that it happens more when resources are in short supply—more likely, it happens when food is abundant” (Wrangham 2006:51).

In the imbalance of power hypothesis, killing is not driven by current resource scarcity, intent to acquire more territory or mates.

[T]he killers don’t get immediate matings or even (normally) any immigrating females as a result. Nor is there any short-term benefit in the form of access to contested food supplies. … In the event of a successful attack there is not immediate pay-off other than the satisfaction the aggressors experience from the act itself. The implication is that natural selection has favoured in chimpanzees a tendency to relish the prospect and performance of such brutality. (Wrangham 2006:51, 53)

This disconnect from any current competition or need for resources is an essential point, with huge implications for chimpanzees and humans. Few would dispute that many human wars are over scarce resources. The imbalance of power hypothesis holds that even without immediate scarcity or competition, both species are inclined to war just because individuals are from different groups. It is the difference between a capacity and a predisposition for collective violence. This book turns on that distinction.

The Dominance Drive

So if it is not food or even females that pushes males forward—what does put a fire in their bellies? What motivates them to seek out, attack, and if possible kill males from other groups? It is the “dominance drive,” the motor for males’ struggles for status within the group, the quest to be alpha or close to it. This emotional system has been mobilized for employ in intergroup relations.

The problem is that males are demonic at unconscious and irrational levels. The motivation of a male chimpanzee who challenges another’s rank is not that he foresees more mating or better food or a longer life. Those rewards explain why sexual selection has favored the desire for power, but the immediate reason he vies for status is simpler, deeper, and less subject to the vagaries of context. It is simply to dominate his peers. Unconscious of the evolutionary rational that placed this prideful goal in his temperament, he devises strategies to achieve it that can be complex, original, and maybe conscious. In the same way, the motivation of male chimpanzees on a border patrol is not to gain land or win females. The temperamental goal is to intimidate the opposition, to beat them to a pulp, to erode their ability to challenge. Winning has become an end in itself.

It looks the same with men (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:199).

This is what the fighting is about. “From the raids of chimpanzees at Gombe to wars among human nations, the same emotion looks extraordinarily important, one that we take for granted and describe most simply but that nonetheless takes us deeply back to our animal origins: pride” (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:190).

The immediate causes of wars are as varied as the interests and policies of those who launch them, but deeper analysis leads to a consistent conclusions: Wars tend to be rooted in the competition for status. … We could well substitute for Sparta and Athens the names of two male chimpanzees in the same community, one rising in power, the other anxious to keep his higher status. (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:192)

Comparing chimpanzees to human youth gangs, “the principal biological influence on collective violence is the male’s concern for status. We assume that this status drive is an inherent tendency of both humans and chimpanzees” (Wrangham and Wilson 2004:234).

Gaining Advantage in Numbers

The imbalance of power hypothesis holds that a dominance driven tendency to kill when killing can be done with impunity was favored by natural selection because it reduced the adult males of neighboring groups, thus weakening their strength compared to the killers’ group (Wilson et al. 2001; 2002:1107–1108; Wrangham 1999:15; Wrangham and Peterson 1996:190–193). That leads to “increased probability of winning intercommunity dominance contests (nonlethal battles); this tends to lead to increased fitness of the killers through improved access to resources such as food, females, or safety” (Wrangham 1999:11–12; Wilson and Wrangham 2003:381).

“In any particular instance [killing] may or may not lead to a bigger territory, but from the perspective of natural selection, killing need only lead to benefits sufficiently often” (Wrangham 2005:18).

A strong evolutionary rational for killing derives from the harsh logic of natural selection. Every homicide shifts the power balance in favor of the killers, giving them an increased chance of outnumbering their opponents and therefore of winning future territorial battles. Bigger territories mean more food, and therefore more babies. (Wrangham 2005:18)

Note carefully that the evolved goal is not to kill off all the males of another group, not to exterminate them, but to reduce the relative number of males, so the killers would win in future nonlethal contests when two communities clash. “[E]xterminating all of a rival group’s males is an extreme outcome of a more general strategy: killing individual rivals whenever possible” (Wilson and Wrangham 2003:379–380).

Applied to Humans

Hunter-gatherers are said to share this generalized hostility to any male beyond their primary social group. In both species, “natural selection has favored specific type of motivational systems” that, “over evolutionary time . . . give individuals access to the resources needed for reproduction.”

The motivations that drive intergroup killing among chimpanzees and humans, by this logic, were selected in the context of territorial competition because reproduction is limited by resources, and resources are limited by territory size. Therefore, it pays for groups to achieve dominance over neighboring groups, so that they can enlarge their territories. To achieve dominance, it is necessary to have greater fighting power than the neighbors. This means that whenever the costs are sufficiently low it pays to kill or damage individuals from neighboring groups. Thus, intergroup killing is viewed as derived from a tendency to strive for status. (Wilson and Wrangham 2003:384)

That is, from the dominance drive.

Wrangham asks: “Did humans get their demons after leaving nature, or have we inherited them from our ancient forest lives?” His answer: “We are apes of nature, cursed over 6 million years or more with a rare inheritance” (1995:7). “[S]election has favored, in chimpanzees and humans, a brain that in appropriate circumstances, seeks out opportunities to impose violence on neighbors. In this sense, the hypothesis is that we have evolved a violent brain” (Wrangham 1999:6). “Chimpanzees and hunter gatherers . . . seek, or take advantage of, opportunities to use imbalances of power for males to kill members of neighboring groups” (Wilson and Wrangham 2003:384).

The position is unchanged in his new book, The Goodness Paradox (Wrangham 2019:257–258). After claiming functional similarities between “simple warfare” raiding and chimpanzee intergroup aggression, and noting how New Guinea villagers praised killers, he writes:

Similar accounts, in which warriors perceive no benefits other than the thrill of making a kill, are rife. From an evolutionary perspective, we can explain their action as we can among animals. Why do they kill? The unnerving answer that makes biological sense is that they enjoy it. Evolution has made the killing of strangers pleasurable, because those that like to kill tended to received adaptive benefits. …The rewards do not have to be anticipated consciously. All that is needed is enjoyment of the kill. Sexual reproduction works in a parallel way. A chimpanzee, or wolf, or any other animal, cannot be expected to know that an act of mating will lead to babies. Why do they mate? They enjoy it. (2019:257–258)

If the urge to kill seems alien to us, that is because we do not live in a Pleistocene world.

A popular article hammers the message home.

[S]election has favored a human tendency to identify enemies, draw moral divides, and exploit weaknesses pitilessly across boundaries. Among hunter-gatherer societies, inner-city gangs, and volunteer militias at the fringes of contested national territories, there are similar patterns of violence. The spontaneous aggressiveness of humans is a harsh product of natural selection, part of an evolutionary morality that revels in short-term victory for one’s own community without regard for the greater good. (Wrangham 2005:19)

Ghiglieri’s approach is consistent with Wrangham’s, although not as theoretically nuanced. He (1987:74; 1988:260) concludes that the chimpanzee record shows that war does “run in our genes like addictive behavior, diabetes, and baldness.” “[A]nyone insisting that men do not possess an instinct to kill other men in certain conditions is in factual error” (Ghiglieri 1999:178). His message for mankind is blunt.

Unfortunately, every race, ethnic group, and tribe has its prejudices. Nearly all have led to atrocities, many lethal, often including full-scale war. The message here is that the human psyche has been equipped by kin selection to urge men to eliminate genetic competitors—males first, females second—when such killing can be safely accomplished. War itself, declared or otherwise, is often motivated by these instinctive genocidal goals. I believe this happens because men are born ethnocentric and xenophobic by nature. (Ghiglieri 1999:215)

Are men born to kill? They answer yes. Our DNA whispers from within, “kill thy neighbor.” This was the big picture as the sociobiological generation theorized the trail blazed by Goodall. Although I will spend this book criticizing it, I must acknowledge that this is a very well-developed theory.

Since then, many panologists[9] have written on chimpanzees’ (and humans’) supposedly innate proclivity to attack and kill outside males. With some variations, the basic idea of implacable intergroup hostility, border patrols and avoidance unless in numbers, stealthy penetrations, and attacks with intent to kill as a reproductive strategy, has hardened into dogma as typical chimpanzee behavior. This is what I will refer to as the Gombe paradigm, or Gombe vision, or the demonic perspective. What does it mean for men, and “why war?”

The Moral of the Story

Goodall (with Berman 1999:141–144) is decidedly the most positive, in her Reason for Hope. She sees humans and chimpanzees sharing a tendency to care about others—not the selfish altruism of sociobiology, but true empathy that counters tendencies toward violence. Just as human brutality exceeds that of chimpanzees, so does our benevolence and self-sacrifice. “So here we are, the human ape, half sinner, half saint, with two opposing tendencies inherited from our ancient past pulling us now toward violence, now toward compassion and love.” “[W]e really do have the ability to override our genetic heritage. … Our brains are sufficiently sophisticated; it’s a question of whether or not we really want to control our instincts.”

One does not get this sense of balance in Ghiglieri (1999:256–257). For him rising above our Dark Side

will eventually require us to make a gigantic leap—on a level never before achieved—away from our instincts of individual and kin group selfishness, xenophobia, and distrust, all of which fuel war and the male violence we face in rape and murder. This leap must propel us to patriotic loyalty within our national community and carry us beyond it toward global cooperation between nations. That this latter goal is not a natural human tendency anyone can realistically expect (outside Earth being invaded by hostile aliens) almost goes without saying. But it is the only way to win against men’s violence.

And in Demonic Males?

So does this study of our warts help us at all? Does it help us take the step we would all like, to create a world where males are less violent than they are today? It would be nice to answer yes, of course, but nothing suggests that a long view of the problem can seriously reduce the violence projected outward from a human society: the Us versus Them problem of human aggression. (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:249)

Well that doesn’t sound too good. Yet don’t despair!

But with an evolutionary perspective we can firmly reject the pessimists who say it has to stay that way. Male demonism is not inevitable. [It has typically reflected the interests of men in power, and] the nature of power, its distribution and effects and ease of monopolization, all depend on circumstance. Add to the equation some of the more obvious unknowns, such as the democratization of the world, drastic changes in weaponry, and explosive revolutions in communication, and the possibilities quickly expand in all directions. We can have no idea how far the wave of history may sweep us from our rougher past. (Wrangham and Peterson 1996:251)

True. Earth might be invaded by hostile aliens.