Radical Anthropology Journal

Part II: On violence and imaginative displacement

IIa: Excursus on transcendent versus immanent imagination

Society as congregation — religion as binding spectacle

Durkheim, the selfish gene — and the anthropological conundrum at the heart of ritual

Anthropology is for everyone — Editorial

Towards a new human universal: rethinking anthropology for our times

The anthropology of unequal society

Managing abundance, not chasing scarcity: the real challenge for the 21st century

Ekila as a guide to proper sharing

Red river hogs: loggers and conservationists

Making the Yaka lifestyle scarce

Abundance as the basis for environmental management

Human nature and the origins of language

Stonehenge: monument of counter-revolution

The material origins of inequality

Trust: self-interest and the common good

Moving testament to an extraordinary life — Book Review

Issue #1 — 2007

Contents

Editorial

Why anthropology matters

Revolution in reverse

The idea of radical change today seems unrealistic. Why? David Graeber investigates

Religion as spectacle

Richard Dawkins may think it’s just a delusion, but religion had a more interesting evolutionary role than that, says Camilla Power

The last word

What Darwinism can tell us about ‘single mums’ and family values

Who we are and what we do

Radical Anthropology is the journal of the Radical Anthropology Group.

Radical: about the inherent, fundamental roots of an issue.

Anthropology: the study of what it means to be human.

Anthropology asks one big question: what does it mean to be human? To answer this, we cannot rely on common sense or on philosophical arguments. We must study how humans actually live — and the many different ways in which they have lived. This means learning, for example, how people in non-capitalist societies live, how they organise themselves and resolve conflict in the absence of a state, the different ways in which a ‘family’ can be run, and so on.

Additionally, it means studying other species and other times. What might it mean to be almost — but not quite — human? How socially self-aware, for example, is a chimpanzee? Do nonhuman primates have a sense of morality? Do they have language? And what about distant times? Who were the Australopithecines and why had they begun walking upright? Where did the Neanderthals come from and why did they become extinct? How, when and why did human art, religion, language and culture first evolve?

The Radical Anthropology Group started in 1984 when Chris Knight’s popular ‘Introduction to Anthropology’ course at Morley College, London, was closed down, supposedly for budgetary reasons. Within a few weeks, the students got organised, electing a treasurer, secretary and other officers. They booked a library in Camden — and invited Chris to continue teaching next year. In this way, the Radical Anthropology Group was born.

Later, Lionel Sims, who since the 1960s had been lecturing in sociology at the University of East London, came across Chris’s PhD on human origins and — excited by the backing it provided for the anthropology of Karl Marx and Friedrich Engels, particularly on the subject of ‘primitive communism’ — invited Chris to help set up Anthropology at UEL. Since its establishment in 1990, Anthropology at UEL has retained close ties with the Radical Anthropology Group.

RAG has never defined itself as a political organisation. But the implications of some forms of science are intrinsically radical, and this applies in particular to the theory that humanity was born in a social revolution. Many RAG members choose to be active in Survival International and/or other indigenous rights movements to defend the land rights and cultural survival of hunter-gatherers. Additionally, some RAG members combine academic research with activist involvement in environmentalist, anti-capitalist and other campaigns. For more on the Radical Anthropology Group, see www.radicalanthropologygroup.org.

Radical Anthropology is edited by Stuart Watkins and Dave Flynn for the Radical Anthropology Group. They also write a blog at http://despairtowhere.blogs.com.

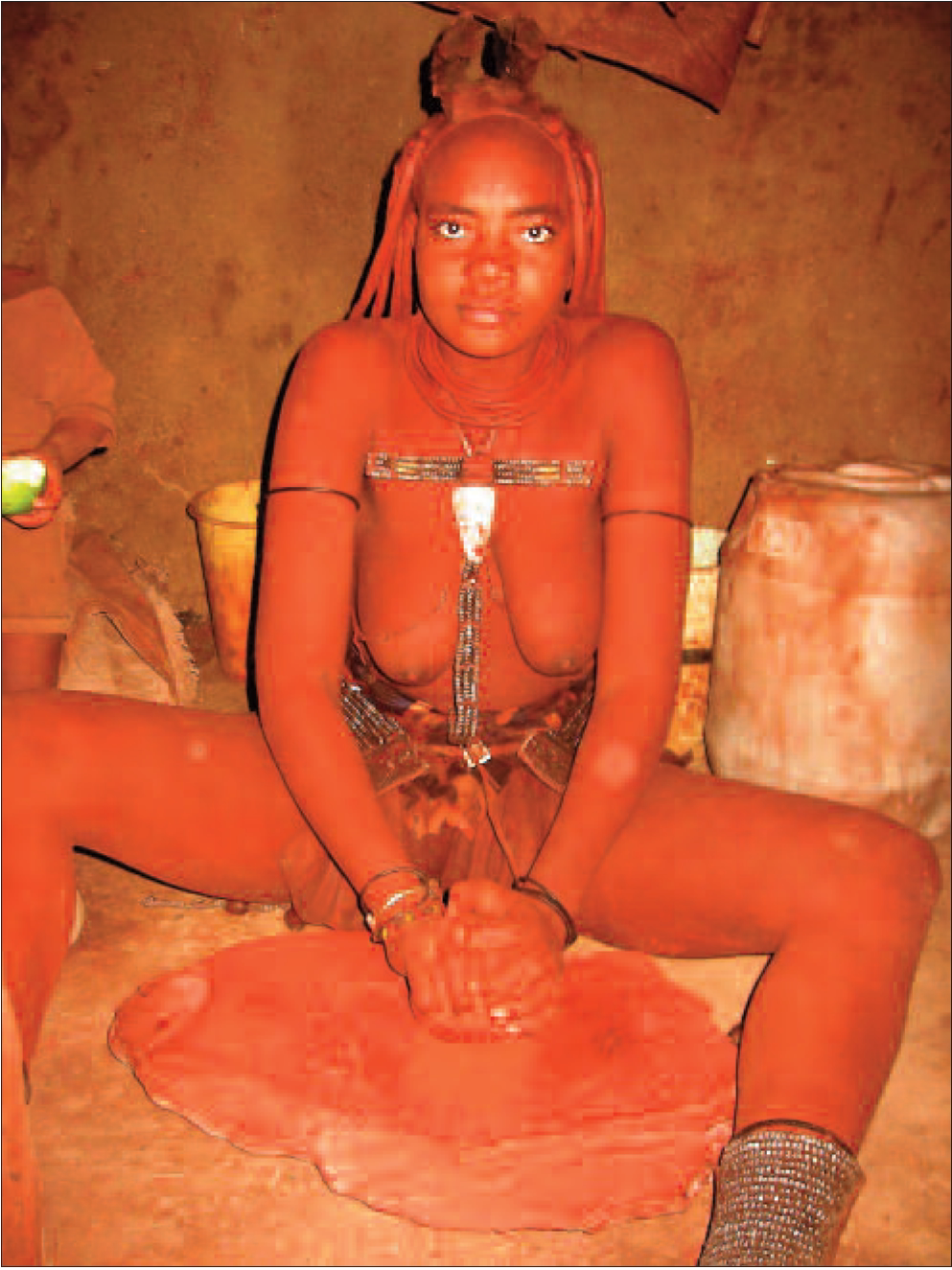

Thanks to Kevin CookFielding for help with the design and layout, and to Martin K. for organising the printing. Pictures in David Graeber’s article and on the cover are by Chris Knight. Pictures of the Himba woman in Camilla Power’s article come from www.askadavid.org.

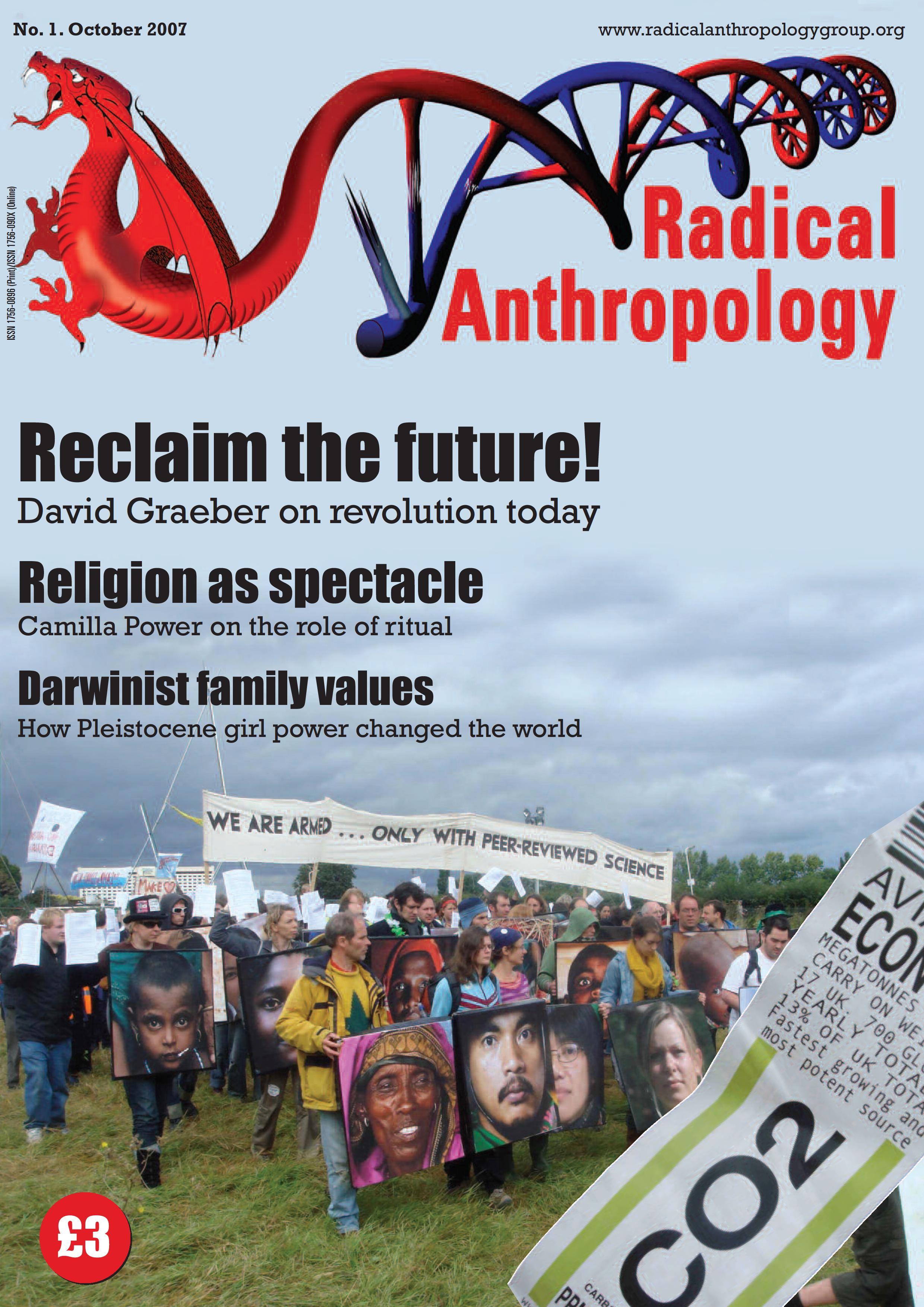

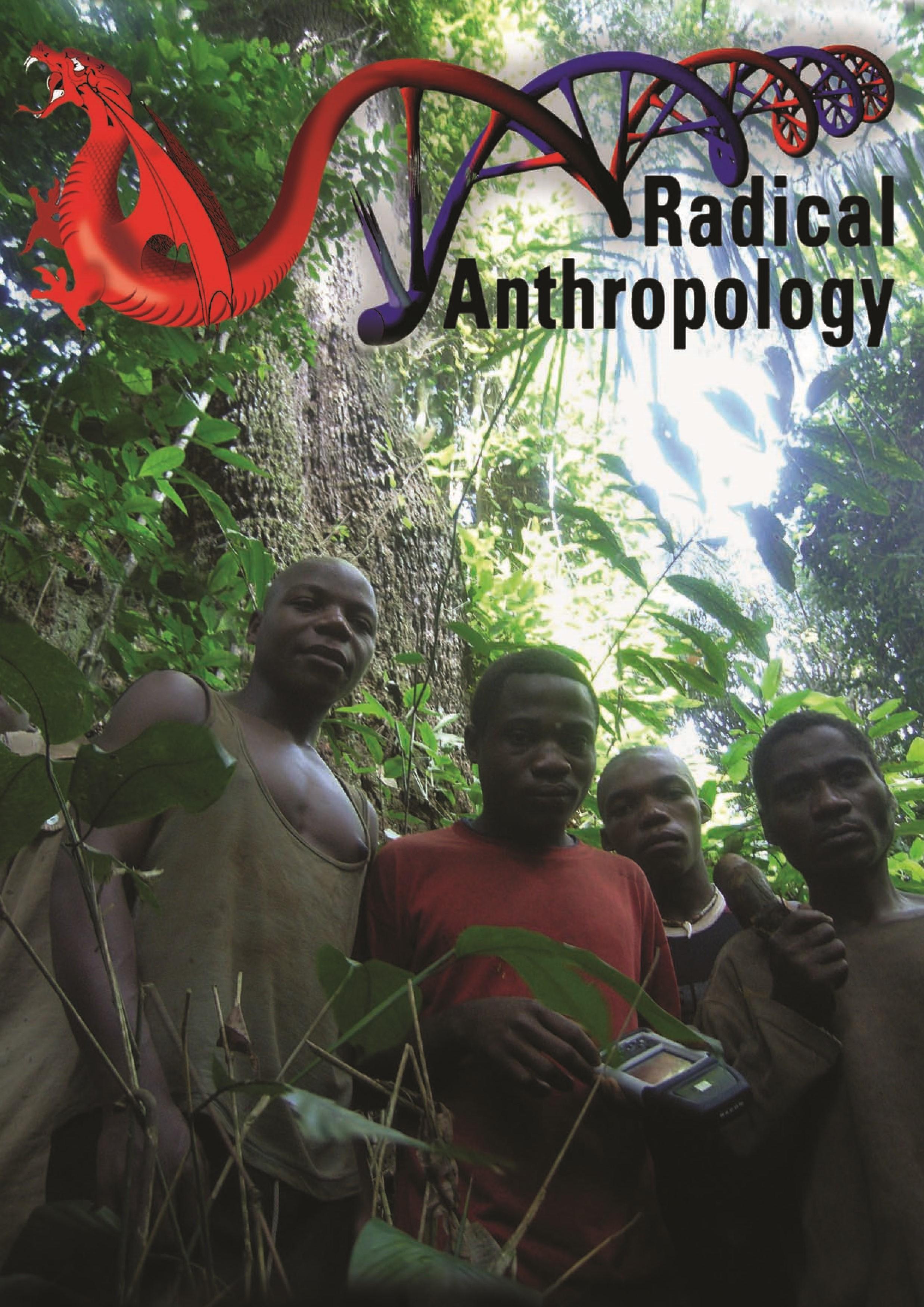

On the cover: The journal’s logo was designed by Kevin CookFielding. It represents the emergence of culture (dragons feature in myths and legends from around the world) from nature (the DNA double-helix, or selfish gene). How this could possibly have happened has long been of especial interest to the Radical Anthropology Group. The dragon is a symbol of solidarity, especially the blood solidarity that was a necessary precondition for the social revolution that made us human. For more on this and related themes, see Radicalanthropologygroup.org

Subscriptions

Radical Anthropology is an annual journal and will appear every October.

In the next issue of Radical Anthropology...

-

Exclusive interview with Noam Chomsky

-

Managing abundance: Jerome Lewis on the Mbendjele hunter-gatherers of Congo-Brazzaville

-

Book reviews

-

And much more...

One issue £3

Two issues £5

Five issues £10

Send a cheque made payable to ‘Radical Anthropology Group’ to RA, c/o Stuart Watkins, 2 Spa View, Leamington Spa, CV31 2HA. Email: stuartrag@yahoo.co.uk.

RA is also available free via our website: www. radicalanthropologygroup.org. Anti-copyright: all material may be freely reproduced for non-commercial purposes, but please mention Radical Anthropology.

We are armed...

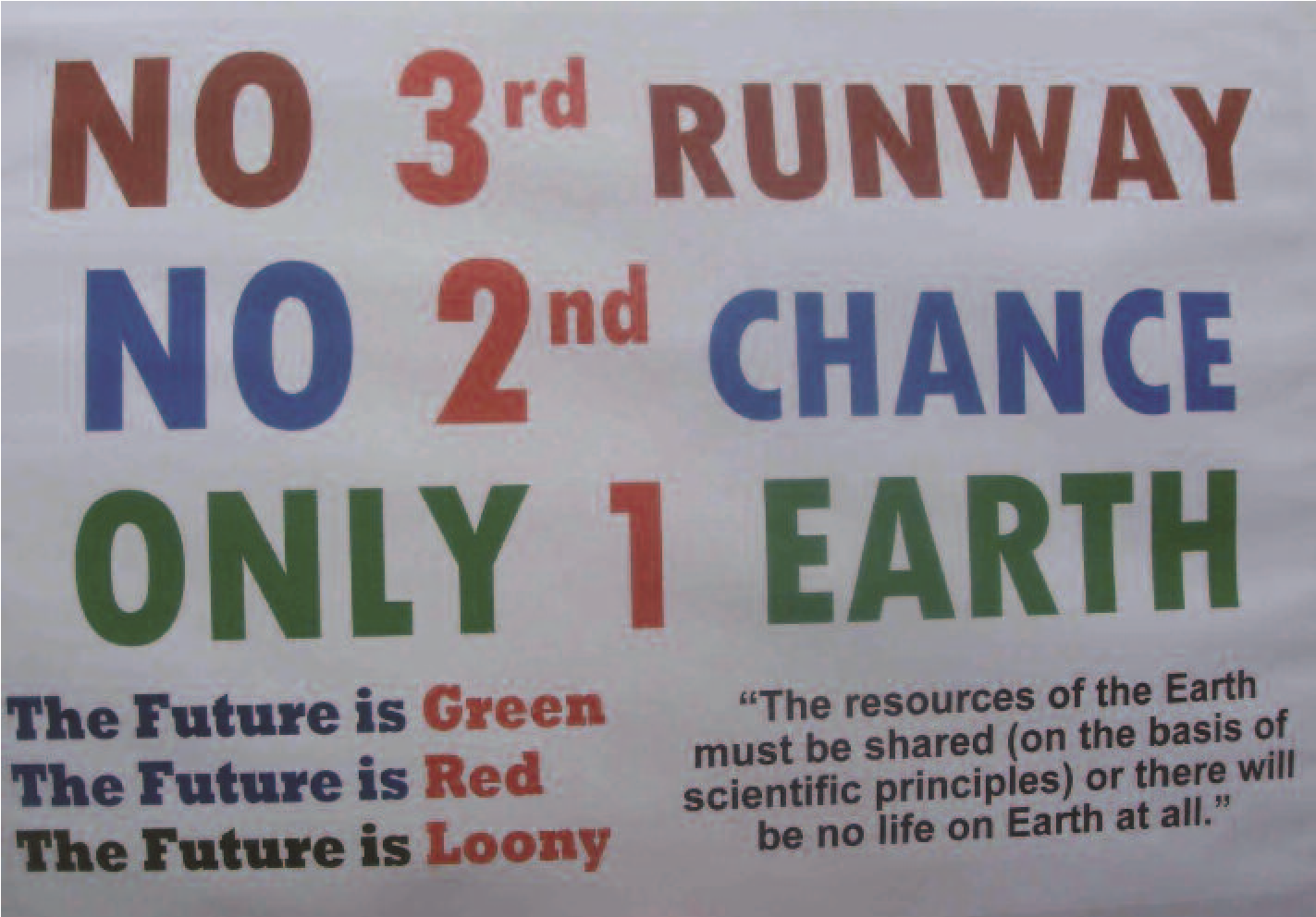

... only with peer-reviewed science. So says the rather brilliant banner that features on the cover of our first issue. The picture was taken at the Climate Camp against the third runway at Heathrow Airport in August of this year. So in this context, the banner obviously refers to the link between independent, peer-reviewed climate science, and the environmental movement that draws strength from its findings. It is here where the battle between science and its discontents takes on its full political importance for the human species. In the case of Darwinists versus creationists and scientists versus postmodernists, it was possible to think that maybe the debates were of purely academic significance. The issues raised by climate science should have shattered that illusion. But we believe that all social activism should arm itself with science, and that scientists should join the social activists. Let us try to explain why.

It can hardly be denied that we live in a troubled world. Even those of us lucky enough to live in a part of the world not actually in a warzone, or where there is access to such human essentials as food and clean water, go through our lives in a constant state of worry about our future. If we are not actually threatened at any one time by the terrorism and crime we are supposed to be most concerned about, we feel anxious and depressed about our future both as individuals (will I have a pension?) and as a species (will there be a planet worth living on?).

The examples could be expanded, but a list of woes is rarely enough to move people to do very much about it. This may be because they think that human life always has and always will be like this. Or, if they fancy themselves more political or radical, because we no longer live in an age of revolutions, or because, with the rise of globalisation, our room for manoeuvre is more limited. Or because previous movements for change have ended in disaster. No amount of philosophical dispute or pub-table arguments can resolve such issues. But if we turn instead to the subjects that have made such concerns their special object of study, we should be delighted to find that, to at least some extent, the answers to these questions are already in. Human societies, in fact, have not always been dominated by conflict and

violence, prioritised material gain over other aspects of our humanity, run economic life according to market principles, worked for wages or for bosses, or been ruled by misery and exploitation. Revolutions have not always ended in disaster. Egalitarian societies in fact still exist — although they, too, face the constant threat of annihilation by capitalist powers.

Pre-eminent among such subjects is anthropology. If what you want is a theory of how humans have lived, and how they might live, and how they bring about and think about change, then anthropology is the most promising place to start looking for one. To use the phrase of one of our contributors to this issue, David Graeber, the “fragments” of such a radical anthropological theory already exist. There is, to continue with Graeber’s argument, an obvious affinity between radical and anthropological thought since both have, as he puts it, a “keen awareness of the very range of human possibilities” (Graeber 2004: 13). Anthropologists sit on a “vast archive of human experience, of social and political experiments no one else really knows about” (2004: 96). And yet it refuses, for the most part, to talk about it. Anthropology, says Graeber, seems like a discipline “terrified of its own potential” (2004: 97). It could so easily, instead, be an “intellectual forum for all sorts of planetary conversations” and make common cause with social activism for the sake of human freedom (2004: 105).

This, then, is the ambition of this journal — to act as just one forum for this planetary conversation. We start, of course, relatively modestly, with two lengthy essays, and one short opinion piece. But we begin appropriately — for in this first issue we feature representatives of what are, for us, the two most exciting trends in the whole of anthropology. The first is David Graeber, and we’ve already heard from him in this editorial. Read more in his sparkling and original essay on page 6. The second, we state rather less modestly, is the school of anthropology of which this is the journal, and some of whose arguments are brilliantly summarised in the essay by Camilla Power (see page 17) and a further editorial by RA (page 26). If Graeber’s project can be glossed as ‘what ethnography can tell us about political practice and human freedom”, Power’s is “what the modern science of human nature can tell us about the same problem”. These themes will be continued in Issue 2, with contributions from linguist Noam Chomsky and social anthropologist Jerome Lewis.

To extend this conversation, we cordially invite letters, articles and book reviews for future issues. Please write to us at the address in the box (bottom left), or email stuartrag@yahoo.co.uk.

Reference: Graeber D. (2004).

Fragments of An Anarchist Anthropology.

Chicago: Prickly Paradigm.

Revolution in Reverse

Revolution in Reverse David Graeber en 2025-12-17T23:20:52 2007 <radicalanthropologygroup.org/journal> anthropology, anarchism, socialism

David Graeber is an anthropologist at Goldsmiths College, University of London. In his previous books, particularly Towards An Anthropological Theory of Value and Fragments of An Anarchist Anthropology, he has spelt out his view of the need for a link between radical politics and anthropology. Here, building on his ethnographic work with direct action activists, he argues that although theories of revolution today seem unrealistic and old-hat, revolutionary practice is in good health. We need, therefore, new theoretical tools. Can anthropology point the way?

“All power to the imagination.” “Be realistic, demand the impossible...” Anyone involved in radical politics has heard these expressions a thousand times. Usually they charm and excite the first time one encounters them, then eventually become so familiar as to seem hackneyed, or just disappear into the ambient background noise of radical life. Rarely if ever are they the object of serious theoretical reflection.

It seems to me that at the current historical juncture, some such reflection wouldn’t be a bad idea. We are at a moment, after all, when received definitions have been thrown into disarray. It is quite possible that we are heading for a revolutionary moment, or perhaps a series of them, but we no longer have any clear idea of what that might even mean. This essay then is the product of a sustained effort to try to rethink terms like realism, imagination, alienation, bureaucracy, and revolution itself. It’s born of some six years of involvement with the alternative globalisation movement and particularly with its most radical, anarchist, direct action-oriented elements. Consider it a kind of preliminary theoretical report.

I want to ask, among other things, why is it that these terms — which for most of us seem rather to evoke long-since forgotten debates of the 1960s — still resonate in those circles? Why is it that the idea of any radical social transformation so often seems “unrealistic”? What does revolution mean once one no longer expects a single, cataclysmic break with past structures of oppression? These seem disparate questions, but it seems to me the answers are related. If in many cases I brush past existing bodies of theory, this is quite intentional: I am trying to see if it is possible to build on the experience of these movements and the theoretical currents that inform them to begin to create something new.

Here is the gist of my argument:

-

Right and left political perspectives are founded, above all, on different assumptions about the ultimate realities of power. The right is rooted in a political ontology of violence, where being realistic means taking into account the forces of destruction. In reply the left has consistently proposed variations on a political ontology of the imagination, in which the forces that are seen as the ultimate realities that need to be taken into account are those (forces of production, creativity...) that bring things into being.

-

The situation is complicated by the fact that systematic inequalities backed by force — structural violence — always produce skewed and fractured structures of the imagination. It is the experience of living inside these fractured structures that we refer to as “alienation”.

-

Our customary conception of revolution is insurrectionary: the idea is to brush aside existing realities of violence by overthrowing the state, then, to unleash the powers of popular imagination and creativity to overcome the structures that create alienation. Over the 20th century it eventually became apparent that the real problem was how to institutionalise such creativity without creating new, often even more violent and alienating structures. As a result, the insurrectionary model no longer seems completely viable, but it’s not clear what will replace it.

-

One response has been the revival of the tradition of direct action. In practice, mass actions reverse the ordinary insurrectionary sequence. Rather than a dramatic confrontation with state power leading first to an outpouring of popular festivity, the creation of new democratic institutions, and eventually the reinvention of everyday life, in organising mass mobilisations, activists drawn principally from subcultural groups create new, directly democratic institutions to organise “festivals of resistance” that ultimately lead to confrontations with the state. This is just one aspect of a more general movement of reformulation that seems to me to be inspired in part by the influence of anarchism, but in even larger part, by feminism — a movement that ultimately aims to recreate the effects of those insurrectionary moments on an ongoing basis. Let me take these one by one.

Part I: “Be realistic...”

From early 2000 to late 2002 I was working with the Direct Action Network in New York—the principal group responsible for organising mass actions as part of the global justice movement in that city at that time. Actually, DAN was not, technically, a group, but a decentralised network, operating on principles of direct democracy according to an elaborate, but strikingly effective, form of consensus process. It played a central role in efforts to create new organisational forms. DAN existed in a purely political space; it had no concrete resources, not even a significant treasury, to administer. Then one day someone gave DAN a car. It caused a minor crisis. We soon discovered that, legally, it is impossible for a decentralised network to own a car. Cars can be owned by individuals, or they can be owned by corporations, which are fictive individuals. They cannot be owned by networks. Unless we were willing to incorporate ourselves as a nonprofit corporation (which would have required a complete reorganisation and abandoning most of our egalitarian principles), the only expedient was to find a volunteer willing to claim to be the owner for legal purposes. But then that person was expected to pay all outstanding fines, insurance fees, provide written permission to allow others to drive out of state, and, of course, only he could retrieve the car if it were impounded. Before long the DAN car had become such a perennial problem that we simply abandoned it.

It struck me there was something important here. Why is it that projects like DAN’s — projects of democratising society — are so often perceived as idle dreams that melt away as soon as they encounter anything that seems like hard material reality? In our case it had nothing to do with inefficiency: police chiefs across the country had called us the best organised force they’d ever had to deal with. It seems to me the reality effect (if one may call it that) comes rather from the fact that radical projects tend to founder, or at least become endlessly difficult, the moment they enter into the world of large, heavy objects: buildings, cars, tractors, boats, industrial machinery. This in turn is not because these objects are somehow intrinsically difficult to administer democratically; it’s because, like the DAN car, they are surrounded by endless government regulation, and effectively impossible to hide from the government’s armed representatives. In America, I’ve seen endless examples. A squat is legalised after a long struggle; suddenly, building inspectors arrive to announce it will take ten thousand dollars worth of repairs to bring it up to code; organisers are forced to spend the next several years organising bake sales and soliciting contributions. This means setting up bank accounts, and legal regulations then specify how a group receiving funds, or dealing with the government, must be organised (again, not as an egalitarian collective). All these regulations are enforced by violence. True, in ordinary life, police rarely come in swinging billy clubs to enforce building code regulations, but, as anarchists often discover, if one simply pretends they don’t exist, that will, eventually, happen. The rarity with which the nightsticks actually appear just helps to make the violence harder to see. This in turn makes the effects of all these regulations — regulations that almost always assume that normal relations between individuals are mediated by the market, and that normal groups are organised hierarchically — seem to emanate not from the government’s monopoly of the use of force, but from the largeness, solidity, and heaviness of the objects themselves.

When one is asked to be “realistic”, then, the reality one is normally being asked to recognise is not one of natural, material facts; neither is it really some supposed ugly truth about human nature. Normally it’s a recognition of the effects of the systematic threat of violence. It even threads our language. Why, for example, is a building referred to as “real property”, or “real estate”? The “real” in this usage is not derived from Latin res, or “thing”: it’s from the Spanish real, meaning, “royal”, “belonging to the king”. All land within a sovereign territory ultimately belongs to the sovereign; legally this is still the case. This is why the state has the right to impose its regulations. But sovereignty ultimately comes down to a monopoly of what is euphemistically referred to as “force” — that is, violence. Just as Giorgio Agamben famously argued that from the perspective of sovereign power, something is alive because you can kill it, so property is “real” because the state can seize or destroy it. In the same way, when one takes a “realist” position in International Relations, one assumes that states will use whatever capacities they have at their disposal, including force of arms, to pursue their national interests. What “reality” is one recognising? Certainly not material reality. The idea that nations are human-like entities with purposes and interests is an entirely metaphysical notion. The King of France had purposes and interests.

“France” does not. What makes it seem “realistic” to suggest it does is simply that those in control of nationstates have the power to raise armies, launch invasions, bomb cities, and can otherwise threaten the use of organised violence in the name of what they describe as their “national interests” — and that it would be foolish to ignore that possibility. National interests are real because they can kill you.

The critical term here is “force”, as in “the state’s monopoly of the use of coercive force.” Whenever we hear this word invoked, we find ourselves in the presence of a political ontology in which the power to destroy, to cause others pain or to threaten to break, damage, or mangle their bodies (or just lock them in a tiny room for the rest of their lives) is treated as the social equivalent of the very energy that drives the cosmos. Contemplate, for instance, the metaphors and displacements that make it possible to construct the following two sentences:

Scientists investigate the nature of physical laws so as to understand the forces that govern the universe.

Police are experts in the scientific application of physical force in order to enforce the laws that govern society.

This is to my mind the essence of rightwing thought: a political ontology that through such subtle means, allows violence to define the very parameters of social existence and common sense.

The left, on the other hand, has always been founded on a different set of assumptions about what is ultimately real, about the very grounds of political being. Obviously leftists don’t deny the reality of violence. Many leftist theorists have thought about it quite a lot. But they don’t tend to give it the same foundational status.

Instead, I would argue that leftist thought is founded on what I will call a “political ontology of the imagination” — though I could as easily have called it an ontology of creativity or making or invention. Nowadays, most of us tend to identify it with the legacy of Marx, with his emphasis on social revolution and forces of material production. But really Marx’s terms emerged from much wider arguments about value, labour, and creativity current in radical circles of his time, whether in the worker’s movement, or for that matter various strains of Romanticism. Marx himself, for all his contempt for the utopian socialists of his day, never ceased to insist that what makes human beings different from animals is that architects, unlike bees, first raise their structures in the imagination. It was the unique property of humans, for Marx, that they first envision things, then bring them into being. It was this process he referred to as “production”. Around the same time, utopian socialists like St. Simon were arguing that artists needed to become the avant garde — or “vanguard”, as he put it — of a new social order, providing the grand visions that industry now had the power to bring into being. What at the time might have seemed the fantasy of an eccentric pamphleteer soon became the charter for a sporadic, uncertain, but apparently permanent alliance that endures to this day. If artistic avant gardes and social revolutionaries have felt a peculiar affinity for one another ever since, borrowing each other’s languages and ideas, it appears to have been insofar as both have remained committed to the idea that the ultimate, hidden truth of the world is that it is something that we make, and could just as easily make differently. In this sense, a phrase like “all power to the imagination” expresses the very quintessence of the left.

To this emphasis on forces of creativity and production, of course the right tends to reply that revolutionaries systematically neglect the social and historical importance of the “means of destruction”: states, armies, executioners, barbarian invasions, criminals, unruly mobs, and so on. Pretending such things are not there, or can simply be wished away, they argue, has the result of ensuring that left-wing regimes will in fact create far more death and destruction than those that have the wisdom to take a more realistic” approach.

Obviously, this dichotomy is very much a simplification. One could level endless qualifications. The bourgeoisie of Marx’s time, for instance, had an extremely productivist philosophy — one reason Marx could see it as a revolutionary force. Elements of the right dabbled with the artistic ideal, and 20th-century Marxist regimes often embraced essentially rightwing theories of power.

Nonetheless, I think these are useful terms because even if one treats imagination” and “violence” not as the single hidden truth of the world but as immanent principles, as equal constituents of any social reality, they can reveal a great deal one would not be able to see otherwise. For one thing, everywhere, imagination and violence seem to interact in predictable, and quite significant, ways.

Let me start with a few words on violence, providing a very schematic overview of arguments that I have developed in somewhat greater detail elsewhere.

Part II: On violence and imaginative displacement

I’m an anthropologist by profession and anthropological discussions of violence are almost always prefaced by statements that violent acts are acts of communication, that they are inherently meaningful, and that this is what is truly important about them. In other words, violence operates largely through the imagination.

All of this is true. I would hardly want to discount the importance of fear and terror in human life. Acts of violence can be — indeed, often are — acts of communication. But the same could be said of any other form of human action, too. It strikes me that what is really important about violence is that it is perhaps the only form of human action that holds out the possibility of operating on others without being communicative. Let me put this more precisely. Violence may well be the only way in which it is possible for one human being to have relatively predictable effects on the actions of another without understanding anything about them. Pretty much any other way one might try to influence another’s actions, one at least has to have some idea who they think they are, who they think you are, what they might want out of the situation, and a host of similar considerations. Hit them over the head hard enough, all this becomes irrelevant. It’s true that the effects one can have by hitting them are quite limited. But they are real enough, and the fact remains that any alternative form of action cannot, without some sort of appeal to shared meanings or understandings, have any sort of effect at all.

What’s more, even attempts to influence another by the threat of violence, which clearly does require some level of shared understandings (at the very least, the other party must understand they are being threatened, and what is being demanded of them), requires much less than any alternative. Most human relations — particularly ongoing ones, such as those between longstanding friends or longstanding enemies — are extremely complicated, endlessly dense with experience and meaning. They require a continual and often subtle work of interpretation; everyone involved must put constant energy into imagining the other’s point of view. Threatening others with physical harm, on the other hand, allows the possibility of cutting through all this. It makes possible relations of a far more schematic kind: ie, ‘cross this line and I will shoot you and otherwise I really don’t care who you are or what you want’. This is, for instance, why violence is so often the preferred weapon of the stupid: one could almost say, the trump card of the stupid, since it is the form of stupidity to which it is most difficult to come up with any intelligent response.

There is, however, one crucial qualification to be made. The more evenly matched two parties are in their capacity for violence, the less all this tends to be true. If one is involved in a relatively equal contest of violence, it is indeed a very good idea to understand as much as possible about them. A military commander will obviously try to get inside his opponent’s mind. It’s really only when one side has an overwhelming advantage in their capacity to cause physical harm that this is no longer the case. Of course, when one side has an overwhelming advantage, they rarely have to actually resort to actually shooting, beating, or blowing people up. The threat will usually suffice. This has a curious effect. It means that the most characteristic quality of violence — its capacity to impose very simple social relations that involve little or no imaginative identification — becomes most salient in situations where actual, physical violence is likely to be least present.

We can speak here (as many do) of structural violence: that systematic inequalities that are ultimately backed up by the threat of force can be seen as a form of violence in themselves. Systems of structural violence invariably seem to produce extreme, lopsided structures of imaginative identification. It’s not that interpretive work isn’t carried out. Society, in any recognisable form, could not operate without it. Rather, the overwhelming burden of the labour is relegated to its victims.

Let me start with the household. A constant staple of 1950s situation comedies, in America, were jokes about the impossibility of understanding women. The jokes, of course, were always told by men. Women’s logic was always being treated as alien and incomprehensible. One never had the impression, on the other hand, that women had much trouble understanding the men. That’s because the women had no choice but to understand men: this was the heyday of the patriarchal family, and women with no access to their own income or resources had little choice but to spend a fair amount of time and energy understanding what the relevant men thought was going on.

Actually, this sort of rhetoric about the mysteries of womankind is a perennial feature of patriarchal families: structures that can, indeed, be considered forms of structural violence insofar as the power of men over women within them is, as generations of feminists have pointed out, ultimately backed up, if often in indirect and hidden ways, by all sorts of coercive force. But generations of female novelists — Virginia Wolfe comes immediately to mind — have also documented the other side of this: the constant work women perform in managing, maintaining, and adjusting the egos of apparently oblivious men — involving an endless work of imaginative identification and what I’ve called interpretive labour. This carries over on every level. Women are always imagining what things look like from a male point of view. Men almost never do the same for women. This is presumably the reason why in so many societies with a pronounced gendered division of labour (that is, most societies), women know a great deal about what men do every day, and men have next to no idea about women’s occupations. Faced with the prospect of even trying to imagine a women’s perspective, many recoil in horror. In the US, one popular trick among high school creative writing teachers is to assign students to write an essay imagining that they were to switch genders, and describe what it would be like to live for one day as a member of the opposite sex. The results are almost always exactly the same: all the girls in class write long and detailed essays demonstrating that they have spent a great deal of time thinking about such questions; roughly half the boys refuse to write the essay entirely. Almost invariably they express profound resentment about having to imagine what it might be like to be a woman.

It should be easy enough to multiply parallel examples. When something goes wrong in a restaurant kitchen, and the boss appears to size things up, he is unlikely to pay much attention to a collection of workers all scrambling to explain their version of the story. Likely as not he’ll tell them all to shut up and just arbitrarily decide what he thinks is likely to have happened: “you’re the new guy, you must have messed up — if you do it again, you’re fired.” It’s those who do not have the power to fire arbitrarily who have to do the work of figuring out what actually happened. What occurs on the most petty or intimate level also occurs on the level of society as a whole.

Curiously enough it was Adam Smith, in his Theory of Moral Sentiments (1761), who first made notice of what’s nowadays labeled “compassion fatigue”. Human beings, he observed, appear to have a natural tendency not only to imaginatively identify with their fellows, but also, as a result, to actually feel one another’s joys and pains. The poor, however, are just too consistently miserable, and as a result, observers, for their own self-protection, tend to simply blot them out. The result is that while those on the bottom spend a great deal of time imagining the perspectives of, and actually caring about, those on the top, it almost never happens the other way around. That is my real point. Whatever the mechanisms, something like this always seems to occur, whether one is dealing with masters and servants, men and women, bosses and workers, rich and poor. Structural inequality — structural violence — invariably creates the same lopsided structures of the imagination. And since, as Smith correctly observed, imagination tends to bring with it sympathy, the victims of structural violence tend to care about its beneficiaries, or at least, to care far more about them than those beneficiaries care about them. In fact, this might well be (aside from the violence itself) the single most powerful force preserving such relations.

It is easy to see bureaucratic procedures as an extension of this phenomenon. One might say they are not so much themselves forms of stupidity and ignorance as modes of organising situations already marked by stupidity and ignorance owing to the existence of structural violence. True, bureaucratic procedure operates as if it were a form of stupidity in that it invariably means ignoring all the subtleties of real human existence and reducing everything to simple pre-established mechanical or statistical formulae. Whether it’s a matter of forms, rules, statistics, or questionnaires, bureaucracy is always about simplification. Ultimately the effect is not so different from the boss who walks in to make an arbitrary snap decision as to what went wrong: it’s a matter of applying very simple schemas to complex, ambiguous situations.

The same goes, in fact, for police, who are after all simply low-level administrators with guns. Police sociologists have long since demonstrated that only a tiny fraction of police work has anything to do with crime. Police are, rather, the immediate representatives of the state’s monopoly of violence, those who step in to actively simplify situations (for example, were someone to actively challenge some bureaucratic definition). Simultaneously, police have become, in contemporary industrial democracies, America in particular, the almost obsessive objects of popular imaginative identification. In fact, the public is constantly invited, in a thousand TV shows and movies, to see the world from a police officer’s perspective, even if it is always the perspective of imaginary police officers, the kind who actually do spend their time fighting crime rather than concerning themselves with broken tail lights or open container laws.

IIa: Excursus on transcendent versus immanent imagination

To imaginatively identify with an imaginary policeman is, of course, not the same as to imaginatively identify with a real one (most Americans, in fact, avoid real policeman like the plague). This is a critical distinction, however much an increasingly digitalised world makes it easy to confuse the two.

It is here helpful to consider the history of the word “imagination”. The common ancient and medieval conception, what we call “the imagination”, was considered the zone of passage between reality and reason. Perceptions from the material world had to pass through the imagination, becoming emotionally charged in the process and mixing with all sorts of phantasms, before the rational mind could grasp their significance. Intentions and desires moved in the opposite direction. It’s only after Descartes, really, that the word “imaginary” came to mean, specifically, anything that is not real: imaginary creatures, imaginary places (Middle Earth, Narnia, planets in faraway galaxies, the Kingdom of Prester John...), imaginary friends. By this definition, of course, a “political ontology of the imagination” would actually be a contradiction in terms. The imagination cannot be the basis of reality. It is by definition that which we can think, but has no reality.

I’ll refer to this latter as “the transcendent notion of the imagination” since it seems to take as its model novels or other works of fiction that create imaginary worlds that presumably remain the same no matter how many times one reads them. Imaginary creatures — elves or unicorns or TV cops — are not affected by the real world. They cannot be, since they don’t exist. In contrast, the kind of imagination I have been referring to here is much closer to the old, immanent, conception. Critically, it is in no sense static and free-floating, but entirely caught up in projects of action that aim to have real effects on the material world, and, as such, always changing and adapting. This is equally true whether one is crafting a knife or a piece of jewelry, or trying to make sure one doesn’t hurt a friend’s feelings.

One might get a sense of how important this distinction really is by returning to the ‘68 slogan about giving power to the imagination. If one takes this to refer to the transcendent imagination — preformed utopian schemes, for example — doing so can, we know, have disastrous effects. Historically, it has often meant imposing them by violence. On the other hand, in a revolutionary situation, one might by the same token argue that not giving full power to the other, immanent, sort of imagination would be equally disastrous.

The relation of violence and imagination is made much more complicated because while in every case structural inequalities tend to split society into those doing imaginative labour, and those who do not, they do so in very different ways.

Capitalism here is a dramatic case in point. Political economy tends to see work in capitalist societies as divided between two spheres: wage labour, for which the paradigm is always factories, and domestic labour — housework, childcare — relegated mainly to women. The first is seen primarily as a matter of creating and maintaining physical objects. The second is probably best seen as a matter of creating and maintaining people and social relations. The distinction is obviously a bit of a caricature: there has never been a society, not even Engels’ Manchester or Victor Hugo’s Paris, where most men were factory workers or most women worked exclusively as housewives. Still, it is a useful starting point since it reveals an interesting divergence. In the sphere of industry, it is generally those on top that relegate to themselves the more imaginative tasks (ie, that design the products and organise production), whereas when inequalities emerge in the sphere of social production, it’s those on the bottom who end up expected to do the major imaginative work (for example, the bulk of what I’ve called the ‘labour of interpretation’ that keeps life running).

No doubt all this makes it easier to see the two as fundamentally different sorts of activity, making it hard for us to recognise interpretive labour, for example, or most of what we usually think of as women’s work, as labour at all. To my mind it would probably be better to recognise it as the primary form of labour. Insofar as a clear distinction can be made here, it’s the care, energy, and labour directed at human beings that should be considered fundamental.

The things we care most about — our loves, passions, rivalries, obsessions — are always other people; and in most societies that are not capitalist, it’s taken for granted that the manufacture of material goods is a subordinate moment in a larger process of fashioning people. In fact, I would argue that one of the most alienating aspects of capitalism is the fact that it forces us to pretend that it is the other way around, and that societies exist primarily to increase their output of things.

Part III: On alienation

In the 20th century, death terrifies men less than the absence of real life. All these dead, mechanised, specialised actions, stealing a little bit of life a thousand times a day until the mind and body are exhausted, until that death which is not the end of life but the final saturation with absence.

Raoul Vaneigem, The Revolution of Everyday Life

Creativity and desire — what we often reduce, in political economy terms, to “production” and “consumption” — are essentially vehicles of the imagination. Structures of inequality and domination, structural violence if you will, tend to skew the imagination. They might create situations where labourers are relegated to mindnumbing, boring, mechanical jobs and only a small elite is allowed to indulge in imaginative labour, leading to the feeling, on the part of the workers, that they are alienated from their own labour, that their very deeds belong to someone else. It might also create social situations where kings, politicians, celebrities or CEOs prance about oblivious to almost everything around them while their wives, servants, staff, and handlers spend all their time engaged in the imaginative work of maintaining them in their fantasies. Most situations of inequality I suspect combine elements of both.

The subjective experience of living inside such lopsided structures of imagination is what we are referring to when we talk about “alienation”.

It strikes me that, if nothing else, this perspective would help explain the lingering appeal of theories of alienation in revolutionary circles, even when the academic left has long since abandoned them. If one enters an anarchist Infoshop, almost anywhere in the world, the French authors one is likely to encounter will still largely consist of situationists like Guy Debord and Raoul Vaneigem, the great theorists of alienation (alongside theorists of the imagination like Cornelius Castoriadis).

For a long time I was genuinely puzzled as to how so many suburban American teenagers could be entranced, for instance, by Raoul Vaneigem’s The Revolution of Everyday Life — a book, after all, written in Paris almost 40 years ago. In the end I decided it must be because Vaneigem’s book was, in its own way, the highest theoretical expression of the feelings of rage, boredom, and revulsion that almost any adolescent at some point feels when confronted with the middle-class existence. The sense of a life broken into fragments, with no ultimate meaning or integrity; of a cynical market system selling its victims commodities and spectacles that themselves represent tiny false images of the very sense of totality and pleasure and community the market has in fact destroyed; the tendency to turn every relation into a form of exchange, to sacrifice life for “survival”, pleasure for renunciation, creativity for hollow homogenous units of power or “dead time” — on some level all this clearly still rings true.

The question though is why. Contemporary social theory offers little explanation. Poststructuralism, which emerged in the immediate aftermath of ‘68, was largely born of the rejection of this sort of analysis. It is now simple common sense among social theorists that one cannot define a society as unnatural unless one assumes that there is some natural way for society to be, inhuman unless there is some authentic human essence, that one cannot say that the self is fragmented unless it would be possible to have a unified self, and so on. Since these positions are untenable — since

there is no natural condition for society, no authentic human essence, no unitary self — theories of alienation have no basis. As arguments, all this seems hard to refute. But, if so, how do we account for the experience?

Still, if one really thinks about it, what are academic theorists saying? They are saying that the idea of a unitary subject, a whole society, a natural order, are unreal. That all these things are simply figments of our imagination. True enough. But then: what else could they be? And why is that a problem? If imagination is indeed a constituent element in the process of how we produce our social and material realities, there is every reason to believe that it proceeds through producing images of totality. That’s simply how the imagination works. One must be able to imagine oneself and others as integrated subjects in order to be able to produce beings that are in fact endlessly multiple, imagine some sort of coherent, bounded “society” in order to produce that chaotic open-ended network of social relations that actually exists, and so forth. Normally, people seem able to live with the disparity. The question, it seems to me, is why in certain times and places, the recognition of it instead tends to spark rage and despair, feelings that the social world is a hollow travesty or malicious joke. This, I would argue, is the result of that warping and shattering of the imagination that is the inevitable effect of structural violence.

Part IV: On revolution

The situationists, like many ‘60s radicals, wished to strike back through a strategy of direct action: creating “situations” by creative acts of subversion that undermined the logic of the spectacle and allowed actors to at least momentarily recapture their imaginative powers. At the same time, they also felt all this was inevitably leading up to a great insurrectionary moment — “the” revolution, properly speaking. If the events of May ‘68 showed anything, it was that if one does not aim to seize state power, there can be no such fundamental, one-time break. The main difference between the situationists and their most avid current readers is that the millenarian element has almost completely fallen away. No one thinks the skies are about to open any time soon. There is a consolation though: that as a result, as close as one can come to experiencing genuine revolutionary freedom, one can begin to experience it immediately. Consider the following statement from the CrimethInc collective, probably the most inspiring young anarchist propagandists operating in the situationist tradition today:

We must make our freedom by cutting holes in the fabric of this reality, by forging new realities which will, in turn, fashion us. Putting yourself in new situations constantly is the only way to ensure that you make your decisions unencumbered by the inertia of habit, custom, law, or prejudice — and it is up to you to create these situations.

Freedom only exists in the moment of revolution. And those moments are not as rare as you think. Change, revolutionary change, is going on constantly and everywhere — and everyone plays a part in it, consciously or not.

What is this but an elegant statement of the logic of direct action: the defiant insistence on acting as if one is already free? The obvious question is how it can contribute to an overall strategy, one that should lead to a cumulative movement towards a world without states and capitalism. Here, no one is completely sure. Most assume the process could only be one of endless improvisation. Insurrectionary moments there will certainly be. Likely as not, quite a few of them. But they will most likely be one element in a far more complex and multifaceted revolutionary process whose outlines could hardly, at this point, be fully anticipated.

In retrospect, what seems strikingly naïve is the old assumption that a single uprising or successful civil war could, as it were, neutralise the entire apparatus of structural violence, at least within a particular national territory: that within that territory, right-wing realities could be simply swept away, to leave the field open for an untrammeled outpouring of revolutionary creativity. But if so, the truly puzzling thing is that, at certain moments of human history, that appeared to be exactly what was happening. It seems to me that if we are to have any chance of grasping the new, emerging conception of revolution, we need to begin by thinking again about the quality of these insurrectionary moments.

One of the most remarkable things about such moments is how they can seem to burst out of nowhere — and then, often, dissolve away as quickly. How is it that the same “public” that two months before, say, the Paris Commune, or Spanish Civil War, had voted in a fairly moderate social-democratic regime will suddenly find itself willing to risk their lives for the same ultra-radicals who received a fraction of the actual vote? Or, to return to May ‘68, how is it that the same public that seemed to support or at least feel strongly sympathetic toward the student/worker uprising could almost immediately afterwards return to the polls and elect a right-wing government? The most common historical explanations — that the revolutionaries didn’t really represent the public or its interests, but that elements of the public perhaps became caught up in some sort of irrational effervescence — seem obviously inadequate.

First of all, they assume that “the public” is an entity with opinions, interests, and allegiances that can be treated as relatively consistent over time. In fact what we call “the public” is created, produced, through specific institutions that allow specific forms of action — taking polls, watching television, voting, signing petitions or writing letters to elected officials or attending public hearings — and not others. These frames of action imply certain ways of talking, thinking, arguing, deliberating. The same “public” that may widely indulge in the use of recreational chemicals may also consistently vote to make such indulgences illegal; the same collection of citizens are likely to come to completely different decisions on questions affecting their communities if organised into a parliamentary system, a system of computerised plebiscites, or a nested series of public assemblies. In fact the entire anarchist project of reinventing direct democracy is premised on assuming this is the case.

To illustrate what I mean, consider that in America the same collection of people referred to in one context as “the public” can in another be referred to as “the workforce”. They become a “workforce”, of course, when they are engaged in different sorts of activity. The “public” does not work — at least, a sentence like “most of the American public works in the service industry” would never appear in a magazine or paper — if a journalist were to attempt to write such a sentence, their editor would certainly change it. It is especially odd since the public does apparently have to go to work: this is why, as leftist critics often complain, the media will always talk about how, say, a transport strike is likely to inconvenience the public, in their capacity of commuters, but it will never occur to them that those striking are themselves part of the public, or that whether if they succeed in raising wage levels this will be a public benefit. And certainly the “public” does not go out into the streets. Its role is as audience to public spectacles, and consumers of public services. When buying or using goods and services privately supplied, the same collection of individuals become something else (“consumers”), just as in other contexts of action it is relabeled a “nation”, “electorate”, or “population”. All these entities are the product of institutions and institutional practices that, in turn, define certain horizons of possibility. Hence when voting in parliamentary elections one might feel obliged to make a “realistic” choice; in an insurrectionary situation, on the other hand, suddenly anything seems possible.

A great deal of recent revolutionary thought essentially asks: what, then, does this collection of people become during such insurrectionary moments? For the last few centuries the conventional answer has been “the people”, and all modern legal regimes ultimately trace their legitimacy to moments of “constituent power”, when the people rise up, usually in arms, to create a new constitutional order. The insurrectionary paradigm, in fact, is embedded in the very idea of the modern state. A number of European theorists, understanding that the ground has shifted, have proposed a new term, “the multitude”, an entity that cannot by definition become the basis for a new national or bureaucratic state. For me the project is deeply ambivalent.

In the terms I’ve been developing, what “the public”, “the workforce”, “consumers”, “population” all have in common is that they are brought into being by institutionalised frames of action that are inherently bureaucratic, and therefore, profoundly alienating. Voting booths, television screens, office cubicles, hospitals, the ritual that surrounds them — one might say these are the very machinery of alienation. They are the instruments through which the human imagination is smashed and shattered. Insurrectionary moments are moments when this bureaucratic apparatus is neutralised. Doing so always seems to have the effect of throwing horizons of possibility wide open. This is only to be expected if one of the main things that apparatus normally does is to enforce extremely limited ones. (This is probably why, as Rebecca Solnit has observed, people often experience something very similar during natural disasters.) This would explain why revolutionary moments always seem to be followed by an outpouring of social, artistic, and intellectual creativity. Normally-unequal structures of imaginative identification are disrupted; everyone is experimenting with trying to see the world from unfamiliar points of view. Normally- unequal structures of creativity are disrupted; everyone feels not only the right, but usually the immediate practical need to recreate and reimagine everything around them.

Hence the ambivalence of the process of renaming. On the one hand, it is understandable that those who wish to make radical claims would like to know in whose name they are making them. On the other, if what I’ve been saying is true, the whole project of first invoking a revolutionary “multitude”, and then to start looking for the dynamic forces that lie behind it, begins to look a lot like the first step of that very process of institutionalisation that must eventually kill the very thing it celebrates. Subjects (publics, peoples, workforces...) are created by specific institutional structures that are essentially frameworks for action. They are what they do. What revolutionaries do is to break existing frames to create new horizons of possibility, an act that then allows a radical restructuring of the social imagination. This is perhaps the one form of action that cannot, by definition, be institutionalised. This is why a number of revolutionary thinkers, from Raffaele Laudani in Italy to the Collectivo Situaciones in Argentina, have begun to suggest it might be better here to speak not of “constituent” but “destituent power”.

IVa: Revolution in reverse

There is a strange paradox in Marx’s approach to revolution. Generally speaking, when Marx speaks of material creativity, he speaks of “production”, and here he insists, as I’ve mentioned, that the defining feature of humanity is that we first imagine things, and then try to bring them into being. When he speaks of social creativity it is almost always in terms of revolution, but here, he insists that imagining something and then trying to bring it into being is precisely what we should never do. That would be utopianism, and for utopianism, he had only withering contempt. The most generous interpretation, I would suggest, is that Marx on some level understood that the production of people and social relations worked on different principles, but also knew he did not really have a theory of what those principles were. Probably it was only with the rise of feminist theory — that I was drawing on so liberally in my earlier analysis — that it became possible to think systematically about such issues. I might add that it is a profound reflection on the effects of structural violence on the imagination that feminist theory itself was so quickly sequestered away into its own subfield where it has had almost no impact on the work of most male theorists.

It seems to me no coincidence, then, that so much of the real practical work of developing a new revolutionary paradigm in recent years has also been the work of feminism; or anyway, that feminist concerns have been the main driving force in their transformation. In America, the current anarchist obsession with consensus and other forms of directly democratic process traces back directly to organisational issues within the feminist movement. What had begun, in the late ‘60s and early ‘70s, as small, intimate, often anarchist-inspired collectives were thrown into crisis when they started growing rapidly in size. Rather than abandon the search for consensus in decision-making, many began trying to develop more formal versions on the same principles. This, in turn, inspired some radical Quakers (who had previously seen their own consensus decision-making as primarily a religious practice) to begin creating training collectives. By the time of the direct action campaigns against the nuclear power industry in the late ‘70s, the whole apparatus of affinity groups, spokes councils, consensus and facilitation had already begun to take something like it’s contemporary form. The resulting outpouring of new forms of consensus process constitutes the most important contribution to revolutionary practice in decades. It is largely the work of feminists engaged in practical organising — a majority, probably, tied to the anarchist tradition. This makes it all the more ironic that male theorists who have not themselves engaged in on-the-ground organising so often feel obliged to include, in otherwise sympathetic statements, a ritualised condemnation of consensus.

The organisation of mass actions themselves — festivals of resistance, as they are often called — can be considered pragmatic experiments in whether it is indeed possible to institutionalise the experience of liberation, the giddy realignment of imaginative powers, everything that is most powerful in the experience of a successful spontaneous insurrection. Or if not to institutionalise it, perhaps, to produce it on call. The effect for those involved is as if everything were happening in reverse. A revolutionary uprising begins with battles in the streets, and if successful, proceeds to outpourings of popular effervescence and festivity. There follows the sober business of creating new institutions, councils, decision-making processes, and ultimately the reinvention of everyday life.

Such at least is the ideal, and certainly there have been moments in human history where something like that has begun to happen — much though, again, such spontaneous creations always seems to end up being subsumed within some new form of violent bureaucracy. However, as I’ve noted, this is more or less inevitable since bureaucracy, however much it serves as the immediate organiser of situations of power and structural blindness, does not create them. Mainly, it simply evolves to manage them.

This is one reason direct action proceeds in the opposite direction. Probably a majority of the participants are drawn from subcultures that are all about reinventing everyday life. Even if not, actions begin with the creation of new forms of collective decision making: councils, assemblies, the endless attention to “process” — and uses those forms to plan the street actions and popular festivities. The result is, usually, a dramatic confrontation with armed representatives of the state. While most organisers would be delighted to see things escalate to a popular insurrection, and something like that does occasionally happen, most would not expect these to mark any kind of permanent breaks in reality. They serve more as something almost along the lines of momentary advertisements — or better, foretastes, experiences of visionary inspiration — for a much slower, painstaking struggle of creating alternative institutions.

One of the most important contributions of feminism, it seems to me, has been to constantly remind everyone that “situations” do not create themselves. There is usually a great deal of work involved. For much of human history, what has been taken as politics has consisted essentially of a series of dramatic performances carried out upon theatrical stages. One of the great gifts of feminism to political thought has been to continually remind us of the people who are in fact making and preparing and cleaning those stages, and even more, maintaining the invisible structures that make them possible — people who have, overwhelmingly, been women.

The normal process of politics of course is to make such people disappear. Indeed, one of the chief functions of women’s work is to make itself disappear. One might say that the political ideal within direct action circles has become to efface the difference; or, to put it another way, that action is seen as genuinely revolutionary when the process of production of situations is experienced as just as liberating as the situations themselves. It is an experiment one might say in the realignment of imagination, of creating truly nonalienated forms of experience.

Conclusion

Obviously it is also attempting to do so in a context in which, far from being put in temporary abeyance, state power (in many parts of the globe at least) so suffuses every aspect of daily existence that its armed representatives intervene to regulate the internal organisational structure of groups allowed to cash cheques or own and operate motor vehicles. One of the remarkable things about the current, neoliberal age is that bureaucracy has come to seem so all-encompassing — this period has seen, after all, the creation of the first effective global administrative system in human history — that we don’t even see it any more. At the same time, the pressures of operating within a context of endless regulation, repression, sexism, racial and class dominance, tend to ensure many who get drawn into the politics of direct action experience a constant alternation of exaltation and burn-out, moments where everything seems possible alternating with moments where nothing does. In other parts of the world, autonomy is much easier to achieve, but at the cost of isolation or almost complete absence of resources. How to create alliances between different zones of possibility is a fundamental problem.

These however are questions of strategy that go well beyond the scope of the current essay. My purpose here has been more modest. Revolutionary theory, it seems to me, has in many fronts advanced much less quickly than revolutionary practice; my aim in writing this has been to see if one could work back from the experience of direct action to begin to create some new theoretical tools. They are hardly meant to be definitive. They may not even prove useful. But perhaps they can contribute to a broader project of re-imagining.

[Adverts]

Capital & Class 93

SPECIAL ISSUE: THE LEFT AND EUROPE

cseoffice@pop.gn.apc.org www.cseweb.org.uk

Tel & Fax: 020 7607 9615

Since 1977 Capital & Class has been the main independent source for a Marxist critique of global capitalism. Pioneering key debates on value theory, domestic labour, and the state, it reaches out into the labour, trade union, anti-racist, feminist, environmentalist and other radical movements. Each issue analyses the important political, economic and social developments of our time and applies a materialist framework unconstrained by divisions into economics, politics, sociology or history.

The current (Autumn) issue is a special issue on The Left and Europe with 198 pages on:

-

The British Left & Europe: Historical Dimensions

-

Europe the Nation State and the Global Political Economy

-

The European Union Regionalism and the ‘Third Way’:

-

Rearticulating Social Democracy

-

The European Union and the Former Communist Bloc

It includes articles and book reviews by John Callaghan, Andy Mullen, Hugo Radice, Magnus Ryner, LarryWilde, Mark Bainbridge, Brian Burkitt, Philip Whyman, Owen Worth, Gerard Strange, Andreas Bieler, Ines Hofbauer, Christoph Herman, Michael Homes, Simon Lightfoot, Ian Barnes, Claire Randerson and Stuart Shields.

SUBSCRIBE TO CAPITAL & CLASS

Subscribers receive three issues of Capital & Class per year, plus unlimited access to the journal’s online electronic archive containing the entire back catalogue of the journal from 1977 to present day. An easy-to-use search engine makes it possible to search the full text of more than 1400 articles and over 700 book reviews, and subscribers can download high quality printable .pdf files.The Capital & Class on-line archive is a major contribution to contemporary Marxist scholarship.

Each issue of Capital & Class includes both in-depth papers and an extensive book reviews section.

For further details please contact:

Capital & Class / CSE

Unit 5

25 Horsell Raod

London N5 IXL

Blood Relations

“Revolutions in science seldom appear ready made... But I suspect that the basis of a new synthesis [of] anthropology and biology may well lie within. this book.” Robin Dunbar, Times Higher Educational Supplement

“This book may be the most important ever written on the evolution of human social organisation. It brings together observation and theory from social anthropology, primatology, and paleoanthropology in a manner never before equalled. The author.is up to date on all these fields and has achieved an extraordinary synthesis.”

Alex Walter, Department of Anthropology, Rutgers University

“.a very readable, witty, lively treasure-trove of anthropological wisdom.”

RE Davis-Floyd, Journal of the Royal Anthropological Institute

“.an immense work of documentation and close argument. For all its obvious risks, the model offers no hypothesis which is not rigorously testable. Not only this, but it appears to solve most of the outstanding conundrums in contemporary anthropology.”

Peter Redgrove, Times Literary Supplement

Buy from BookDepository.co.uk

Society as congregation — religion as binding spectacle

Camilla Power is senior lecturer in anthropology at the University of East London and a member of the Radical Anthropology Group. She has published many articles on the evolutionary origins of ritual, gender and the use of cosmetics in African initiation. Here, she looks at the legacy of sociology’s founding father, Emile Durkheim.

He implied that society was born in a communistic revolution. Does this theory still stand up?

Emile Durkheim’s The Elementary Forms of the Religious Life is a frustrating and astonishing work. Published just before the First World War, the book reached the brink of the conclusion that human culture was created through communistic revolution. In Durkheim’s understanding, the necessary vehicle for experience sufficiently intense and collective to create and structure society was ritual — periodically reiterated performance of a religious character, associated by Durkheim with totemic cult action. The object of worship, under the “flag” of the totem, was society itself, or, as he puts it, “the determined society called the clan” (1915: 206). Durkheim does not allow that social thought, with its efficacy greater than individual thought (1915: 228), can come into being and be established except through the violent and intense emotional solidarity attained in sacred ritual, the “collective effervescence” involving all members of the constituted group as participants. In other words, the origin of collective thought, of symbolic culture, and of language itself, is unimaginable without religious ritual. At origin, religion is no more and no less than a group’s collective consciousness of itself as a group expressed through symbolism: “social life, in all its aspects and in every period of its history, is made possible only by a vast symbolism” (1915: 231).

The crucial, central chapters of Elementary Forms are entitled ‘Origins of These Beliefs’. The entire work is an argument, which Durkheim considered to be fully scientific, concerning the origin of religion, therefore of human culture itself. Yet Durkheim tiptoed back from the edge of declaring a revolutionary emergence of communistic ritual to be the source of earliest human society. He implied it certainly: that thought and reason could only be born out of intense collectivity — the group’s lived experience of “the sacred” creating and sustaining ideal collective representations. He defined the sacred, as against profane, in terms of the power to arouse and nourish those collective representations. Through sacred ritual, the members of the group experienced collective intelligence as a material power greater than mere individual intelligence, a power manifested visibly in the summoning of the ritual congregation.

For Durkheim and Mauss: “the first logical categories were social categories; the first classes of things were classes of men” (1963 [1902]: 82). In the ‘Conclusion’ to Elementary Forms, Durkheim expounded the idea of logical/conceptual thought and religious thought as coeval. The emergence of conceptual thought was implicitly bound up in the first symbolic construction of ‘society’. Before all, religion “is a system of ideas with which the individuals represent to themselves the society of which they are members...This is its primary function...” (1915: 225). As Lévi- Strauss stated the case later, writing within Durkheim’s tradition: “Things cannot have begun to signify gradually” (1987: 59). The revolutionary emergence of symbolic thought required the explosive motor and transformational power of ritual. Drawing mainly on the ethnographies of Howitt, and Spencer and Gillen, Durkheim described the fevered pitch of excitement, emotion and intensive bouts of activity that marked periods of ritual aggregation among Australian tribes. The terms of this description — of violent frenzy harnessed through regularity of rhythm and unifying movement in chant and dance — do not admit of any gradualist notion of the emergence of collective consciousness. It is revolutionary through and through.

Yet, into his introduction, Durkheim had inserted a cautionary disclaimer regarding his investigation of “the old problem” of the origin of religion. “To be sure,” wrote Durkheim, “if by origin we are to understand the very first beginning, the question has nothing scientific about it, and should be resolutely discarded. There was no given moment when religion began to exist...” (1915: 8). This statement is at odds with Durkheim’s own procedure throughout the book, which aims to identify the essential character of the religious and to define religious representation by examining the most ‘primitive’ forms of religion. And it is at odds with his own sharp distinction, drawn at the end of the book, between animals who “know only one world” and men who “alone have the faculty of conceiving the ideal, of adding something to the real” (1915: 421). Durkheim rejected any explanation of this in terms of men’s “natural faculty for idealising” which, he said, merely changes the terms of the problem, and does not at all resolve it. For him, religion (hence culture) is purely a social product. But Durkheim adopts positions which are contradictory. He cannot simultaneously maintain the distinction between human collective consciousness and animal individual consciousness, reject out of hand any godlike intervention in human consciousness, and also assert that “religion did not commence anywhere”. Somewhere along the line of human evolution religion arose; something created it; we must presume with Durkheim that humans did so. This was an event, a revolution in human social life.

Within a few years of the publication of Elementary Forms, the Russian revolution had galvanised massive military and political reaction in the capitalist west. This inevitably had repercussions in western science, not least in anthropology. To press the argument on human origins any further down Durkheim’s road, towards validation of primitive communism, became completely ideologically unacceptable.

Malinowski’s and Radcliffe-Brown’s various statements discrediting speculation on origins provide evidence enough for this. The door was firmly slammed on discussion of human cultural evolution within social anthropology — the only discipline which had sound claims to discuss the subject. For the best part of a century, progress in a science of religion and mythology has come solely through the work of Lévi-Strauss. The founder of structuralism was able to evade the political implications of carrying on this work only by means of an extreme idealism and a point-blank refusal to discuss the question of ritual at all. The current standing of Durkheim’s theory that religion made us human is best assessed by Ernest Gellner’s remarks in Reason and Culture: “I do not know whether this theory is true, and I doubt whether anyone else knows either: but the question to which it offers an answer is a very real and serious one. No better theory is available to answer it” (1992: 37).

Gellner acknowledges that since Durkheim’s discussion of the role of religion and ritual in human culture there has been no scientific progress on the subject. At the same time, he doubts whether the theory as it stands is testable. One social anthropologist who does consider that Durkheim’s theory, with refinement and modification, can be subject to scientific testing is Chris Knight.

A marxist and structuralist, Knight (1991) developed a model of human cultural origins which incorporates several key elements from Durkheim’s work on religion — notably ‘totemic’ relations as central to earliest ritual; an ideology of blood as the conceptual root of clan solidarity; and particularly menstrual taboos as the organising principle behind rules of exogamy (for the latter see especially Durkheim’s Incest: the nature and origin of the taboo, which may be regarded as an early draft for Elementary Forms). Knight’s more recent work on the origin of ritual and language (1999) continues the tradition of Durkheim’s thinking on religious representations as collective representations. In this essay I will point to the convergences between Durkheim’s and Knight’s arguments. This modifies the theme of ‘Society realised in spectacle’ — implying the passive status of onlooker — to one of ‘Society realised through pantomime’, with active participation and involvement of all group members in the performance.

In his commentary on Durkheim’s scenario, Gellner refers to the doctrine that in worshipping its god-symbol of solidarity a society unwittingly worships itself. This he considers “far less interesting and important than the view that what makes us human and social is our capacity to be constrained by compulsive concepts, and the theory that the compulsion is instilled by ritual” (1992: 37). Gellner’s précis of the Durkheimian argument is apt, if tongue-in-cheek:

“In the crazed frenzy of the collective dance around the totem, each individual psyche is reduced to a trembling suggestive jelly: the ritual then imprints the required shared ideas, the collective representations, on this malleable proto-social human matter. It thereby makes it conceptbound, constrained and socially clubbable.

“The morning after the rite the savage wakes up with a bad hangover and a deeply internalised concept. Thus, and only thus, does ritual make us human” (1992: 36–7).

The problem Durkheim addresses is how a construct (such as ‘god’ or ‘supernatural potency’) can be sufficiently identical in the minds of members of any group to be labelled and collectively referred to. Once this has happened, the concept can be summoned up by any member of the collective at any time. As Gellner suggests, an extremely tight — compulsive — constraint is needed to ensure that the concept be faithfully transmitted. Error of transmission would erode the process of collectivisation. How can I be sure my concept is the same as your concept, so that one label will summon up both? The solution proposed by Durkheim is that collectivisation occurs through a precise ritual sequence, demanding unity and synchrony of action, highly stereotyped, amplified and repetitive — hence pantomime. In Durkheim’s words: