Raymond H. Prince

Trance and Possession States

Part I: the Phenomena: Distribution and Patterns

World Distribution and Patterns of Possession States

Explanations of Trance Behavior: Naturalistic and Supernaturalistic

Naturalistic Explanations: Positive and Negative

Supernaturalistic Explanations: Possession and Non-Possession Beliefs

Non-Possession Beliefs: Soul-Absence

Possession Beliefs: Spirit-Presence

Influence of the Explanatory System on Trance Behavior

Possession Belief and Non-Trance Behavior

Notable Features of the Scheme of Explanatory Systems

Typological Division of Trance and Possession States

Distribution of Trance and Possession States

The Sociology of !Kung Bushman Trance Performances

Spatial Arrangements in the Dance

Division of Sex Roles in the Dance

Typical Dance-Trance Sequences

Phase I — Working Up — chaxni chi (‘dance and song)

Phase II — Entering Trance — n/um n/i nluma (‘causing medicine to boil’)

Phase III — ‘Half Death’ — Kweli (‘like dead’)

Folk View of Trance Performances

Recruitment and Training of Trance Performers

Bushman Trance in the Context of Altered States of Consciousness (ASC)

Trance, Shamanism, and Witchcraft

Trance States and Ego Psychology

Transcultural Comparison of Hypnosis and Other Trance States

Altered States of Consciousness

General Characteristics of ASC’s

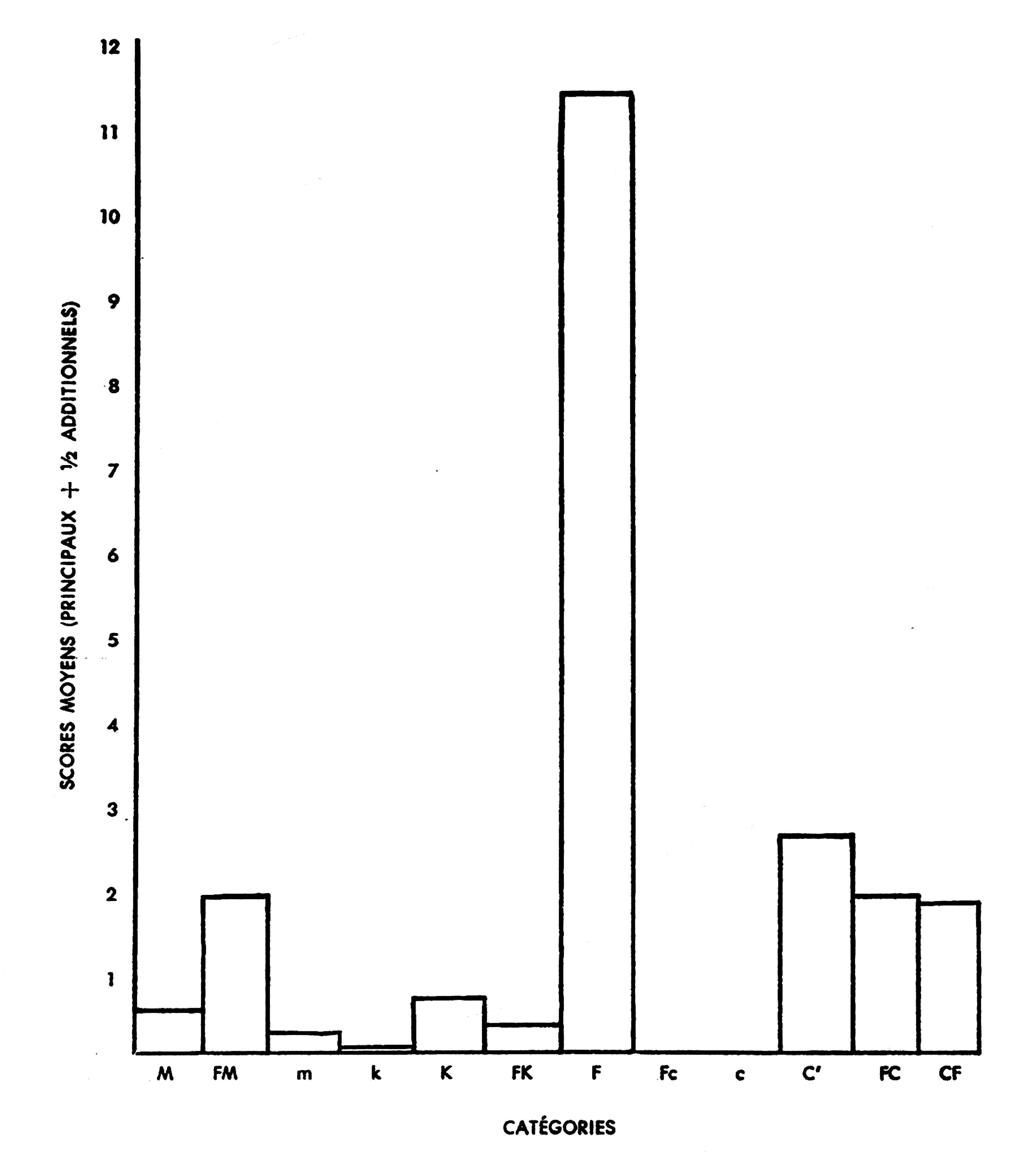

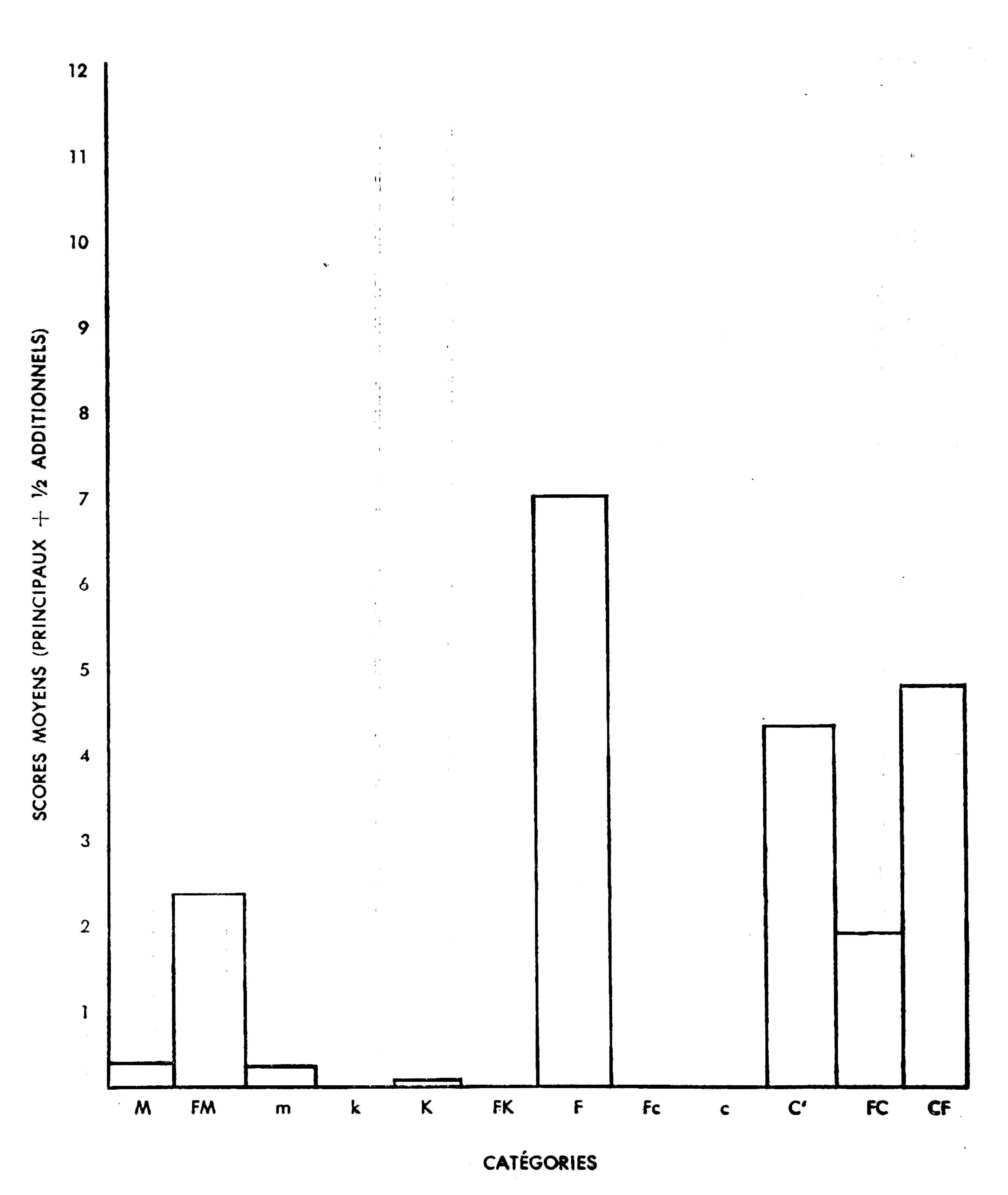

L’examen Au Rorschach Des Vaudouisants Haïtiens

Analyse Quantitative (Selon Les Categories)

Analyse Qualitative (Selon Les Protocoles)

Can the EEG Be Used in the Study of Possession States?

Psychomotor Amnesic States and the EEG

Features of Possession States Suggesting an Altered Neurophysiology

Sargant and Therapeutic Collapse

Telemetering the Electroencephalogram

Possession States as Psychotherapy

The Psychotherapeutic Value of Spirit-Possession in Haiti

Possession Cults and Social Cybernetics

Social Disintegration and Psychiatric Disorder

Possession Cults and Cybernetics

The Religious Meaning of Possession States (with Indo-Tibetan Emphasis)

The Meaning of Possession States

Universal Religions View Possession States: A Panel Discussion

The Attitude of Catholicism Towards Possession States

The Attitudes of Catholic Missionaries in Eastern Nigeria

The Islamic Attitude Towards Possession States

Proceedings

Second Annual Conference

R. M. Bucke Memorial Society

4–6 March 1966

Montreal

Copyright Canada 1968

R. M. Bucke Memorial Society

All rights reserved

Library of Congress catalogue card number: 68–19908

Printed in Canada

by l’Imprimerie Electra

Preface

The R. M. Bucke Memorial Society was founded in the summer of 1964 and is devoted to the study of areas common to religion and psychiatry, particularly to the study of mystical or transcendental states of consciousness.

The society commemorates a distinguished nineteenth-century Canadian psychiatrist. A graduate of the McGill Medical School, Dr. Bucke was a pioneer in the movement towards humane treatment of the mentally ill. He was superintendent of the Ontario Hospital, London, for twenty-five years and a president of the American Medico-Psychological Association. Bucke was also interested in mystical experience and wrote several papers and books on the subject, including the well-known Cosmic Consciousness.

It might be asked why a society devoted to the study of mystical states should interest itself in possession states. At first glance there seems to be little similarity: the one suggesting a solitary illumination, the other an orgiastic dance. And yet there are basic similarities. The most obvious is the belief of those involved that these states represent the point of intersection of the human and the divine. Mystical states are believed by many to be the experience of the self in the presence of God; or to represent the immersion of the personal ego within the Infinite, a fusion of the self with the One. Possession states too, are regarded as circumstances in which a spirit or minor deity takes control, or, as it is frequently formulated, mounts and directs the devotee.

Both states, moreover, are considered to be psychotherapeutic. The Bhagavad Gita says regarding the mystical state, samadhi:

When one thoroughly abandons all cravings of the mind, and is satisfied in the self, through the self, then he is called stable of mind.... The self-controlled practitioner, while enjoying the various sense objects through the senses, which are disciplined and free from likes and dislikes, attains placidity of mind. With the attainment of such placidity of mind, all his sorrows come to an end and the intellect of such a person of tranquil mind soon withdraws itself from all sides and becomes firmly established in the supreme reality.

Many authors have pointed out that apart from any supernatural attributes, mystical experiences often result in states of placidity and well-being which sound very much like good mental health. Possession states too, as will become apparent during this present conference, may be psychotherapeutic. In many cultures, the emotionally disturbed are directed by their healer-priest to join possession cults in order to be healed.

Both kinds of states are, in fact, alterations of consciousness. There are, of course, differences in the level or quality of consciousness. In most possession states the individual, when he returns to normal consciousness, forgets what happened during the possession state; he is simply aware of having lad a lapse. On the other hand, mystical states occur in a clearer state of consciousness, and there is some degree of recollection. The experience during the mystical state, however, is difficult to describe; the ineffable quality of mystical states is well known.

In the spite of these differences, descriptions of the entry into the two states are sometimes similar. Consider the following two descriptions; one refers to a Voodoo possession state, the other to a mystical state:

There is no way out. The white darkness moves up the veins of my leg like swift tide rising, rising; is a great force which I cannot sustain or contain, which surely will burst my skin. It is too much, too bright, too white for me; this is darkness. ‘Mercy!’ I scream within me. I hear it echoed by the voices, shrill and unearthly; ‘Erzulie.’ The bright darkness floods up through my body, reaches my head, engulfs me. I am sucked down and exploded upward at once. That is all.[1]

It was as if houses, doors, temples and everything else vanished all together, as if there was nothing anywhere! And what I saw was an infinite shoreless sea of light; a sea that was consciousness. However far and in what direction I looked, I saw shining waves, one after another, coming towards me. They were raging and storming upon me with great speed. Very soon they were upon me; they made me sink down into unknown depths. I panted and struggled and lost consciousness.[2]

The first of these describes Maya Deren’s entry into a Voodoo possession state. The second describes Ramakrishna’s entry into samadhi. The similarity is striking.

It is true that there is often a difference in the setting in which the two states occur. Typically, mystical states are sought through medication, mortification, and solitude; possession states, on the other hand, generally occur as a group phenomenon, and there is often drumming, music, and dancing. Yet in certain cults this distinction becomes blurred. For example, Sufi practices otherwise representative of the mystical experience, are often accompanied by dance and music. Listen to Landolt’s description:

On several occasions, Sufis used to sit together and to listen to a singer reciting profane or mystical love poetry, until one or the other rose up in ecstasy, sometimes tearing up his garb. Simulation of ecstatic movements (tawajod) was also allowed, in order to induce real ecstasy. In certain groups, there exists in connection with listening to music dance ritual.[3]

The idea upon which this conference is based, then, is that possession states are to the more archaic forms of religious life what mystical states are to its more evolved forms. It is to be hoped that, as well as expanding our knowledge of the nature of possession states and primitive religions, we may, by throwing light on the more primitive states, also illuminate the meaning and function of mystical states.

RAYMOND PRINCE, M.D.

President

Acknowledgments

The generous financial support of the Parapsychology Foundation and of the Aquinas Fund is gratefully acknowledged.

Dr. William Sargant kindly agreed to introduce the conference by si owing and discussing his excellent collection of films demonstrating possession states in the West Indies and in various African countries, as well as in England and the USA. Professor Werner Cohn gave us an impromptu report of his work on glossolalia and personality which is being conducted at the University of British Columbia. He illustrated his discussion with a film showing glossolalia as he has been able to produce it in the laboratory. Through the courtesy of Mr. and Mrs. Lawrence K. Marshall we were able to view their excellent film on Bushman trance states which Richard Lee used to illustrate his paper.

Mr. J. A. Zielinski handled the complex audio-visual components on the conference. Prof. H. B. M. Murphy gave us much helpful advice. Linda Parsons, Grace Prince, and Clifford Brown helped in a variety of ways.

Contents

Preface

Acknowledgements

Contents

Part I: The Phenomena: Distribution and Patterns

Erika Bourguignon

World Distribution and Patterns of Possession States

Richard B. Lee

The Sociology of !kung Bushman Trance Performances

Part II: Nature and Methods of Study

Peter H. Van Der Walde

Trance States and Ego Psychology

Arnold M. Ludwig

Altered States of Consciousness

Emerson Douyon

L’examen Au Rorschach Des Vaudouisants Haitians

Raymond Prince

Can the Eeg Be Used in the Study of Possession States

Part III: Meaning and Purpose

Possession States as Psychotherapy

Ari Kiev

The Psychotherapeutic Value of Spirit-possession in Haiti

Taghi Modarressi

The Zar Cult in South Iran

Raymond Prince

Possession Cults and Social Cybernetics

Alex Wayman

The Religious Meaning of Possession States (With Indo-tibetan Emphasis)

Universal Religions View Possession States

D. H. Salman

The Attitude of Catholicism Towards Possession States

L. H. Pazder

The Attitudes of Catholic Missionaries in Eastern Nigeria

Dale Eickelman

The Islamic Attitude Towards Possession States

Monroe Peaston

Possession and Trance States: A Protestant View

Concluding Remarks

Part I: the Phenomena: Distribution and Patterns

Chairman Professor F. Henry

Department of Anthropology

McGill University

World Distribution and Patterns of Possession States[4]

Erika Bourguignon

Department of Anthropology

Ohio State University, Columbus

Before beginning our discussion of world distribution and patterns of possession states, we shall need to introduce some distinctions and definitions and to indicate just what sort of states and beliefs we shall be talking about. As far as world distribution of these states is concerned, our program will take us to the Bushman, to northern India, to Haiti, to Nigeria, and to Iran, as well as to various times and places of the Western world. This fact alone seems to indicate a very broad range indeed. We shall, therefore, consider some distribution maps, later on, which will attempt to provide geographic orientation for our discussions.

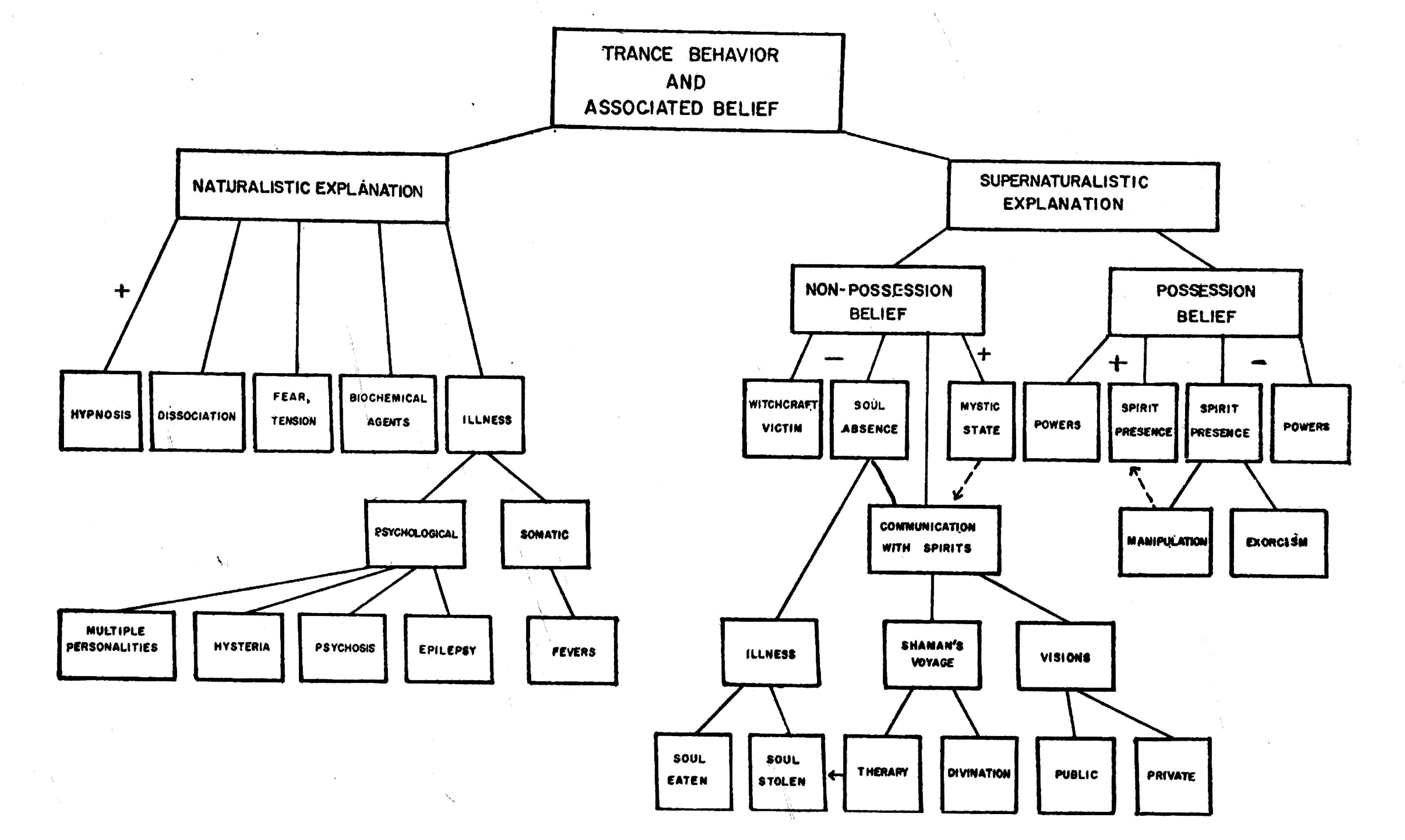

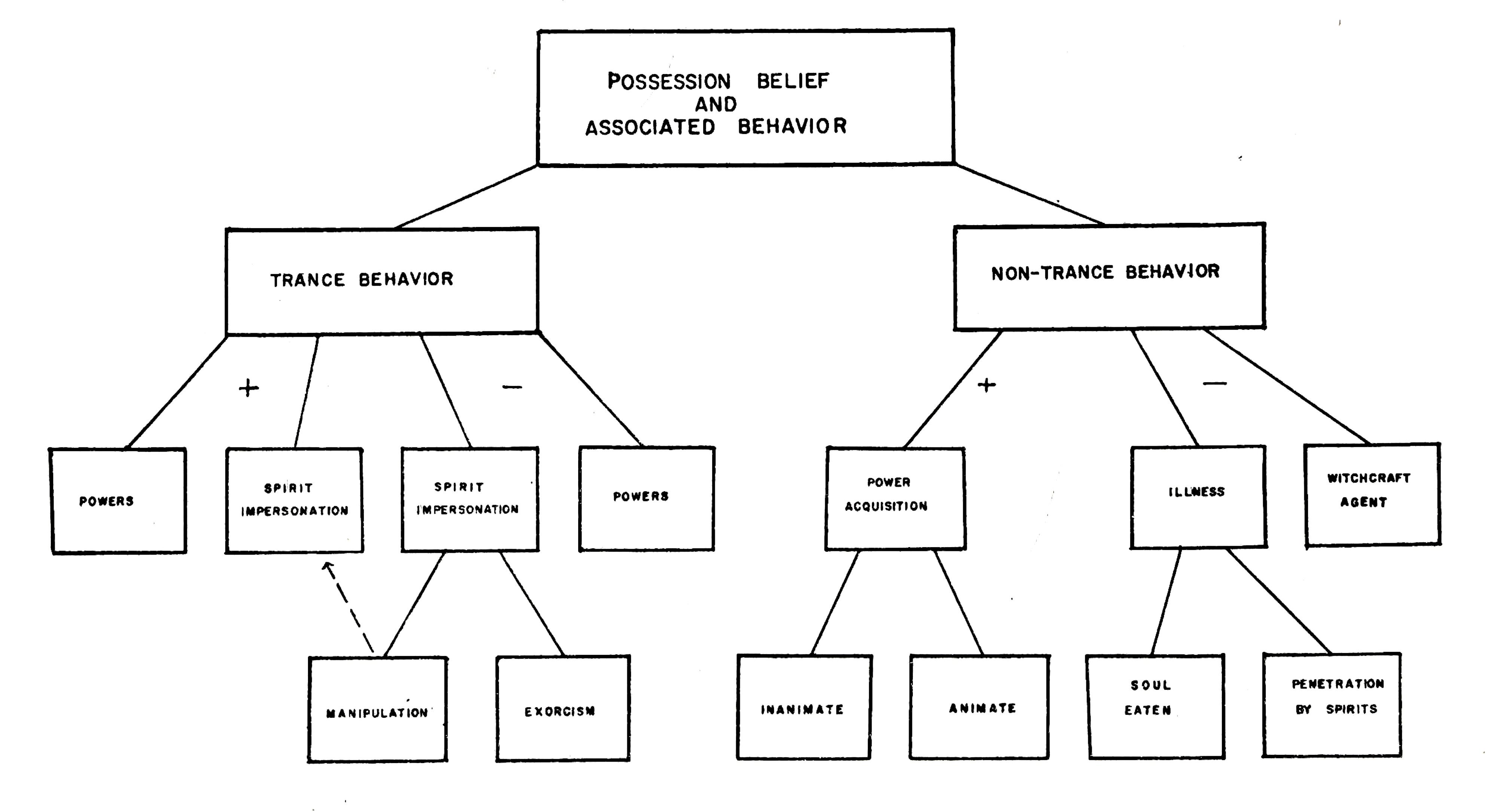

For almost three years a group of us at Ohio State University has been involved in a broadly conceived cross-cultural study of dissociational states and of the explanatory systems to which they are linked in the societies in which they occur. We discovered early in our investigations that dissociation or trance, itself a complex and variable phenomenon, might or might not be interpreted and experienced as possession in a particular society, and that the concept of possession, in turn, might or might not be utilized to account for forms of behavior other than those of dissociation. We have, herefore, found it useful in our work to distinguish between trance behavior and associated beliefs on the one hand (as represented in Table I) and possession beliefs and associated behavior on the other (as represented in Table II).

The two categories meet and overlap in the constellation which will concern us most in the discussions of this conference, namely trance behavior linked to possession belief. These states we shall refer to in the following pages as states of ‘possession trance’. We shall return to this in a moment.

Tables I and II represent an attempt to bring some order into the vast quantities of highly varied materials that we have encountered in an analysis of descriptive accounts of some seven hundred cultural groups from all parts of the world. In these accounts, the terms ‘trance’ and ‘possession’ recur, but seem to refer to a variety of phenomena. We have attempted to organize our materials to show what conceptual relations, if any, exist between them.

Explanations of Trance Behavior: Naturalistic and Supernaturalistic

We may begin, then, with a closer look at Table I. Here we are concerned with a somewhat heterogeneous class of behavioral patterns, for which we have decided to use the term ‘trance’, and with the ways in which this class of behavioral patterns is interpreted or explained. We are concerned with the interpretations which are current in the societies in which the behavior is found, rather than with interpretations which claim to be supra-cultural or extra-cultural, such as those which we, as Western anthropologists or psychiatrists, might make. We are not asking here how we would interpret, for example, Yoruba trance behavior; but rather how, on the one hand, the Yoruba themselves account for trance, and how, on the other hand, members of our own societies (American or Canadian, as the case may be) account for trance states occurring within our own social environment.

Generally, explanations of trance may be divided into two types. We shall call them, for lack of better terms, ‘naturalistic’ and ‘supernaturalistic’. The former term has been chosen as the clearest opposite to the latter, and denotes explanations that take into account only natural processes and forces, and not supernatural and spiritual ones. ‘Supernaturalistic’ explanations of trance, as the name implies, draw on spiritual or supernatural processes, entities, or forces to account for the phenomena observed.

While we find naturalistic explanations of trance widely used in the Western world, they are not the only explanations used there. Indeed, the sub-cultural differences in modern mass societies make it particularly difficult to discuss trance behavior and spirit-possession beliefs in relation to these societies. On the other hand, we must also admit that ‘naturalistic’ explanations are not the exclusive property of modern Western society. Thus, for example, the Samburu, a pastoral tribal people of East Africa related to the Masai, believe that trance states, which occur with some frequency among their young men, are due to the pecuriarities of their status and the tensions associated with it. No supernaturalistic explanations of these states are offered (Spencer, 1965).

Naturalistic Explanations: Positive and Negative

Naturalistic explanations may be listed as either ‘positive’ or ‘negative,’ indicating whether they are considered desirable or undesirable, or, in some cases, can be listed as neither. In this naturalistic classification, we may interpret negative to mean pathological,’ and positive and neutral to mean ‘non-pathological’. We may note, in this connection, that in contemporary scientific literature the term ‘trance’ is found in only one context outside of ethnography, and that is in the context of hypnosis. We may consider hypnotic trance phenomena as being non-pathological; also non-pathological are those types of dissociation which are not part of a disease situation. Whether the artist’s and the poet’s inspiration or the actor’s impersonation (his identification with his role) are to be listed here is perhaps debatable, and we have not included them in our table. Some states of dissociation brought about by biochemical agents, such as drugs and alcohol, must undoubtedly be included here. The states produced by them (for example, those produced by the so-called psychedelic drugs) are eagerly sought by some as a positive good and, at least in some instances, without any supematuralistic explanations. On the other hand, the greatest likelihood exists that we will encounter more complex dissociational states in the context of illness, on the negative side of our diagram. Illness may be linked to the use of biochemical agents, as in the case of addiction. Then again, illness may be considered as involving disorders of a primarily psychological or psychiatric character (psychosis, hysteria, multiple personalities, epilepsy) or of a primarily somatic character, as in certain types of fever-producing illnesses.

While this discussion of naturalistic explanations of trance in Western society and elsewhere could be considerably elaborated, it is included here in its abbreviated form primarily for the sake of balance and completeness.

Supernaturalistic Explanations: Possession and Non-Possession Beliefs

Under the heading of super naturalistic explanation of trance behavior, we may distinguish between those explanations which involve concepts of possession and those which do not Several categories are to be examined among the latter. Perhaps the rarest or most atypical is that kind of trance thought to be due to being bewitched, or more generally, due to the power of witches and others (for example, the presumably hypnotic powers of the Pawnee medicine men) to cause persons to experience various types of alterations in their perceptual awareness of their bodies or their environment.

Of undoubtedly greater significance are the mystic states of Eastern and Western religious experience,[5] often associated with preliminary exercises of meditation, concentration, and certain rules of bodily manipulation (abstinence, fasting, breathing exercises, and the like). Some of these bear a relationship, mutatis mutandis, to methods used in attempts to communicate with spirits, as in the vision-quest of some American Indian tribes. Communication with spirits may occur in a private search or in a public seance, be it that of the Western spirit medium or of the Eskimo or Siberian shaman.

Non-Possession Beliefs: Soul-Absence

Various forms of absence of the soul, or of one of several souls, are also to be found among explanations for the existence of trance states. While permanent absence of the soul commonly serves as an explanation of death, temporary absence of the soul may serve to explain illness-producing trance states as situations in which the soul has been stolen by evil forces or spirits, or has been devoured by them. On the positive side, soul-absence may involve communication with spirits, in that the soul (or one soul) of the shaman may be thought to have gone or a voyage to the land of the spirits to divine the cause of the patient’s illness or of other difficulties, or even to fight hostile spirits and bring back the soul of his patient and, thus, to effect a cure. In this instance, as in many others, the line between the positive and the negative sides of our diagram is difficult to draw, for the shaman’s positive diagnostic and curative powers may have been acquired only as the result of a previous illness in which a temporary soul-loss was involved.

While the shamanistic trance, as well as the vision-quest trance in other cultural contexts, may sometimes be aided by the use of biochemical or physical agents, the factors inducing trance are not our concern in the present analysis. Rather, we wish to distinguish here the various explanatory systems used in the cultural contexts in which these states occur. While many South American Indian groups, for example, recognize the need to swallow great quantities of tobacco juice or tobacco smoke as a preliminary to their trance states (Dole, 1964), it is the reported contacts with supernatural beings during these trance states that are of primary interest to us here. The physiological factors associated with the trance state, its induction, and its termination, all require a separate analysis.

Soul-absence, either in the form of the shaman’s voyage to the beyond or in the form of soul-loss illness, rivals possession as one of the major explanatory systems of trance. Like possession, as we shall see later, it has both a positive application (to the activity of the shaman) and a negative application (to illness). And like possession it applies not only to trance states but to other types of illness as well. Furthermore, it is also applied to shamanistic performances of the non-inspired type, so widespread among the Indians of North America, where there is no clear-cut evidence of trance states (Loeb, 1929). However, a discussion of the non-trance application of soul-absence would take us too far afield.[6]

As Luc de Heusch has pointed out (1962), belief in spirit-possession necessarily implies a belief in the temporary absence of a soul; for in order for possession to take place, particularly that type of possession involved in trance behavior, the displacement of a soul by the possessing spirit must occur. While this may be logically indisputable, nonetheless people with highly developed possession theories usually appear to pay little attention to this concomitant facet of their interpretation. A notable exception is found among the Yaruro Indians of Venezuela. According to Yaruro beliefs, the shaman journeys to the spirit land and urges the spirits to help his people, and the spirits in turn “arrive in the husk of the shaman, which he has left behind as a channel of communication for the other-wordly beings while his divisible self travels abroad” (Leeds, 1960). Among the Senoi and Samai of Malaya (Dentan, n.d.), the shaman may either send his soul away or be possessed; both interpretations of trance behavior and of communication with spirits during trance states are known to exist.

Generally speaking, however, in spite of these overlappings and occasional difficulties of interpretation, we may say that super-naturalistic interpretations of trance may or may not involve spirit-possession, and, among those which do not, theories of soul-absence are prominent. It should be noted, moreover, that both theories may occur in the same society, as alternative explanations of the same observations, as complementary explanations (as in the case of the Yaruro), or, more frequently, as applying to different social contexts.

Possession Beliefs: Spirit-Presence

We may now proceed to take a closer look at trance behavior interpreted as spirit-possession. This is charted at the right of Table I and to the left of Table II, which shows belief in spirit-possession. Here, we may again divide the experiences into positive and negative ones, i.e., into desired and undesired states. This parallels Oesterreich’s distinction (1922) between voluntary and non-voluntary possession. Another similar distinction is made by Murphy (1964) when she speaks of ‘spirit-intrusion’ as a cause of illness, but limits the term ‘spirit-possession’ to its positive application, as in the case of shamanistic seizures. In both instances, possession may be either by spirits or by non-personalized powers. The spirits may be those of greater or of lesser gods, of dead or of living human beings, or even of animals; the dead may be ancestors, fellow tribesmen, or strangers; and so may the living. (The variety here is very great, but much of the information needed for systematic classification of this material is unavailable in the literature on the subject.) It is striking, however, that where there is a belie in a High God, belief in possession by such a God is rare. In Christian tradition, there exists a belief in possession by the Holy Ghost, but not, with some dubious exceptions, by the other persons of the Trinity. There is no correlation apparent to us, as yet, between the type of possessing spirit and positively or negatively evaluated possession; nor with other differences to be discussed in the following paragraphs.

While we may contrast positive types of possession trance with undesired types, we may also compare these states along other lines. When we are dealing with a belief in possession by spirits rather than powers, we find that the trancer acts out an impersonation of the spirit. The behavior will, therefore, vary in conformity with the concept of the spirit which is to be impersonated. It may vary from the chaotic behavior of participants in the Kentucky revival to the formal and orderly behavior of the Balinese child trance dancers. It may be stereotyped, as in Bali, or individuated, as in the case of the Haitian voodoo pantheon; it may be traditional and prescribed drama, as in Bali, or commedia dell’arte improvisation, as in Haiti. In both of these instances we find dramatic performances, whereas in the behavior of the shaman among the Nuba we find only a verbal impersonation. The range of possibilities is very broad here and the comparisons and contrasts which have been drawn in the literature have been predicated on whichever of the two, the similarities or the contrasts, has been focused upon. (Each of these cultural instances, I venture to say, is unique in its combinations of elements, some of which, in any given case, are comparable to elements in one society while others are comparable to elements in caite another society. Thus, even in the Afro-American cults, significant differences between one cultural or sub-cultural variety and another exist, and are to be understood in terms of a particular history and a particular sociocultural context.)

In possession trance, we find a very clear expression of the influence of learning and expectation on the behavior of the trancer. From a cultural and psychological point of view, it is important to stress that there is great variation in the amount of leeway which is permitted for the direct or symbolic expression of personal motivations and psychological themes. The more ritualistic, stereotypic, and formalized the proceedings, and the more the trancer must follow a dramatic ‘script,’ the less room will there be for a satisfaction of idiosyncratic needs.

Where spirit-possession is seen as undesired, either the spirits may be exorcised, expelled, and dispatched, or they may be manipulated and, within certain limits, transformed into helpful spirits. In this case, only the initial possession is negative; indeed, later ones, having been brought under control, may be positively evaluated. Shamanism, with its frequently associated initial state of illness, may involve either this type of situation in the context of possession trance, or, as we have seen earlier, trance without possession in the context of the shamanistic voyage or other types of communication between shaman and spirits.

Possession trance may also involve a belief in powers or forces (rather than in individuated spirits) which take over the person of the trancer. On the positive side, this is seen in the case of the Navaho hand-trembler, or curer, whose power resides in his arm and provides a diagnosis in response to his questioning (Kaplan and Johnson, 1964). Localized trance, however, may also be found in connection with spirits, rather than powers, as in Bali.

Influence of the Explanatory System on Trance Behavior

It is clear that whatever the physiological sources and constants of trance behavior, the explanatory system to which it is linked will necessarily influence the behavior exhibited. In some of its facets, therefore, trance behavior explained as possession may be expected to differ significantly from trance behavior not so interpreted, although these categories are not so truly distinct nor even so contradictory as might appear to be the case on purely / logical grounds. We may consider that where spirit voices speak through the shaman in trance we are dealing with possession trance, and that where he, in trance, is heard to converse with spirits, we are dealing with non-possession trance. Yet the spirit voices, however altered, are still produced by him, and the distinction may not be an entirely meaningful one to the people involved. Furthermore, we also find cases of shamans or conjurors who are reported to be conversing with spirit voices, but who are also reported as not being in trance nor in ecstatic states. Indeed much has been said on the ventriloquist abilities of North American shamans or conjurors. We have already referred to Loeb’s famous distinction between shaman and seer (op. cit.), which Hallowell (1942) has quoted and applied to the Saulteaux conjurors. The data on North American conjurors are primarily historical and the psychological materials are sparse. Generally, we must consider most of these materials outside the context of trance simply because the data required for their inclusion are absent. And yet Hallowell’s material raises some tantalizing questions; as, for example, when he tells us that the Saulteaux conjurors were probably generally of good faith, and that some claimed to have seen the spirits in the conjuring lodge. The problem is not very different from that presented by Boas (1930), and analyzed by Lévi-Strauss (1958), for the Kwakiutl. However, we are, I believe, on safe ground in asserting that, whatever the situation of the conjuror from the point of view of his culture, it is not likely that he experienced a truly altered state of consciousness, and furthermore that there was no discontinuity of personality functions, of sensory modalities, of memory, or even of behavior patterns, all of which we must necessarily consider criteria of dissociation. While much has been written on the question of extra-sensory perception among conjurors, there simply are no adequate data available on which to base a discussion.

Possession Belief and Non-Trance Behavior

Possession, as indicated earlier, need not be expressed through trance behavior. Here again, we may bifurcate our materials into positive (desired) possessions and negative (undesired) possessions. In the negative variety, possession is due to a personalized, animate being. We again find that such possession may cause illness or may transform a person into an agent of a witchcraft being. Such a being may cause illness in others and its physical presence in its agent will be found upon the agent’s death and the performance of an autopsy on his body. This is a notion which appears to be limited to Africa, as far as our present data show, but which is rather widespread on that continent. Illness blamed on possession may be thought of as being due to the entry of illness spirits into the body. More specifically, such spirits cause illness by attempting to eat the soul or one of the souls of the victim and, indeed, cause death if they succeed in doing so. The positive type of possession, on the other hand, involves the presence of a power, either inanimate or that of a previously living spirit. Such possessions are permanent and confer power, and although they are not expressed through trance states, the first acquisition of the power may indeed be expressed through a brief state of dissociation, as in the installation ceremonies of the Nyikang, the king of the Shilluk (Lienhardt, 1954). Here, the soul of the first king enters the body of the new king during his installation and this occurrence is observed as a brief seizure. The possession itself, however, is permanent. Among the Jivaro, on the other hand, the souls acquired through headhunting confer power through possession. There is, however, neither trance, seizure, nor personality alteration (Harner, 1962). On the other hand, the possessing power may be inanimate, like that which resides in the Navaho or Havasupai medicine man, and which makes his cures possible.

Notable Features of the Scheme of Explanatory Systems

Our scheme makes no claim to finality of any kind. It is to be considered merely as a heuristic device, which has, it seems to me, permitted us to bring some order into a bewilderingly vast and diverse mass of materials. In developing this scheme, we are considering the materials from the perspective of culturally divers tied systems of cognition and explanation. For an ordering of other data (for example, the factors involved in trance induction) one would require a totally different scheme, built on such supra-cultural categories as those of biochemistry, physiology, pharmacology, etc. (On the other hand, it is tempting to suggest at least one hypothesis that links the two systems: it is my impression that possession trance is much less likely to involve biochemical and physical agents for trance induction than do trance states associated with other explanatory systems.)

As we examine the categories of explanation included in Tables I and II, we note the recurrence of several features. The most striking of these is the recurrence of both negative and positive evaluations of trance, both in the naturalistic and the several supernaturalistic explanations of trance, and in the application of possession concepts to non-trance behavioral states as well. This contrast is so striking that, as we have pointed out earlier, Oesterreich (op. cit.), who did not distinguish between trance and possession, used it as the basic organizing concept of his pioneering work by speaking of voluntary (positive) and involuntary (negative) types of possession.

The observation that a limited set of common explanatory categories serves for both positively and negatively evaluated experiences deserves special mention. The significance of this fact is further highlighted by the observation that negative experiences may be transformed into positive ones. Illness involving types of trance (for example, loss of consciousness, fugue states, visions, etc.) and variously interpreted as soul-loss, as possession, or as a supernatural call, often precedes the acquisition of supernatural powers. We may cite, choosing our examples almost at random, the Balinese of Indonesia (Belo, 1960), the Dards of Pakistan (Snoy, 1960), and the Akan-Ashanti shrine cults of Ghana (Field, 1960), in addition to well-known examples from Siberian shamanism (Bogoras, 1907). A less drastic transformation occurs in the various possession cults of East Africa, in particular in the zar cult of the Amhara and their neighbors. Here, possession is seen as the cause of illness, and possession-trance is induced in order to question the spirit as to its demands. However, the spirit is not exorcised or dispatched. Rather, attempts are made to meet its demands and a modus vivendi is worked out between the patient and the spirit, which involves, apparently, a degree of manipulation of the patient’s social environment. And while the patient, generally, does not become a shaman, a therapeutic result is achieved. Moreover, future instances of possession-trance are evaluated positively, rather than negatively, and possession thereafter is voluntary rather than involuntary (Leiris, 1958; Messing, 1958).

Combinations of trance experience with several types of explanation, and combinations of possession theories with various types of behavioral manifestations, may co-exist in the same society.

An example is provided by the For of Dahomey. Here soul-loss trance, in the form of ‘tempora ry death,’ precedes possession trance (Verger, 1957). In Azande society we have another constellation, this time involving divination. In this case, divination through possession trance is found only among women, and trance divination without possession only among men (Evans-Pritchard, 1937, 1962). Here, two forms of trance coexist in the same society, but in varying socio-cultural contexts within it.

Typological Division of Trance and Possession States

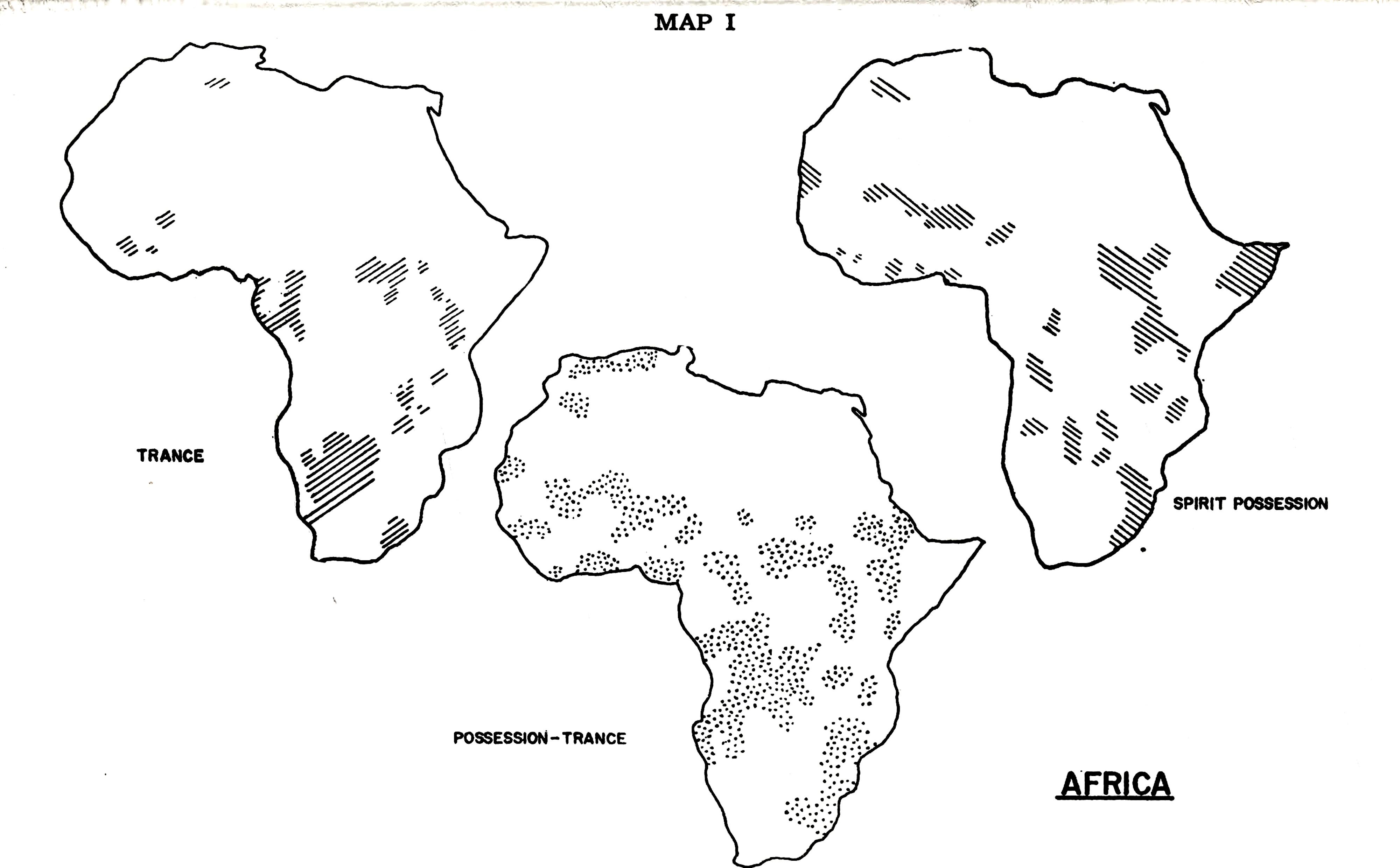

If we now wish to examine the worldwide distribution of the phenomena under disci ssion, we shall not be able to do justice to the various detailed aspects considered so far. Rather, we shall have to limit ourselves to a somewhat cruder analysis. In the following, then, we shall distinguish only between possession-trance (PT), trance linked to other explanatory theories (T), and possession linked to other behaviors (P). Theoretically, presence or absence of any or all of these three variables gives us eight possible types, as shown in Table III. And indeed, we do find various instances of each of these eight theoretically possible types represented in our ethnographic sample. Some random examples are indicated in Table III.

TABLE III

| Type | T | P | PT | Ethnographic Examples |

| 1 | — | — | — | Pygmies, Tiv |

| 2 | x | — | — | Bushmen, Amahuaca |

| 3 | — | x | — | Nyakyusa, Aymara |

| 4 | — | — | x | Trinidadians |

| 5 | x | x | — | Ayoreo, Riffians |

| 6 | x | — | x | Yoruba, Azande |

| 7 | — | x | x | Haitians, Ndembu, Shilluk |

| 8 | x | x | x | Fiji |

-- absent x present

Two preliminary words of caution are called for, however, before we proceed to a discussion of our distributional maps. These refer (1) to the problem of the absence of a cultural trait, and (2) to the heterogeneity of the types represented in Table HI.

1) Absence of a cultural trait. This is the great handicap in all distribution studies. It is as important to identify the societies and regions in which a given trait or trait-complex (here PT, T, or P) is absent as it is to identify those in which it is present, and this fact is implied in our typology. Furthermore, any correlational studies would need to contrast groups in which a trait or trait-complex is absent with those in which it is present. And yet, specific concrete information on absence of trance practices or possession beliefs is virtually non-existent in ethnographic literature. And since we now know that the presence of PT does not necessarily imply the absence of T, nor the presence of T the absence of P, our discussions of presence or absence depend mostly on inference and circumstantial evidence, tend to be equivalent to ‘not reported,’ and stand to be corrected.

2) Heterogeneity of types. As must be evident from our discussion of the variety of subdivisions which we have found for our categories PT, T, and P, combinations of these are not likely to yield homogeneous types. Thus, for example, our Type 2 is represented by the African Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert (Marshall, 1962) and the Amahuaca Indians of the interior Amazon region (Carneiro, 1964). In both instances, trance involves communication with spirits and no concept of possession is reported; and also in both instances, it is the men who go into trance. However, the Bushman trance appears to be induced by dance and by psychological factors; it is a collective phenemenon, primarily concerned with curing. On the other hand, neither curing nor dancing are relevant in the case of the Amahuaca. Other differences, differences of a geographic, ecological, economic, social, and cultural nature, also exist between these two groups. To cite another example: Type 3 is represented by the Aymara of Bolivia and by the Nyakyusa, a Northeast Bantu people of East Africa. Both of these groups have a belief in possession which is not related to trance behavior. The Aymara believe that possession causes illness (LaBarre, 1948). On the other hand, the Nyakyusa believe that only certain men are possessed and that such possession turns them into witches. Witchcraft is thought of, in concrete terms, as the presence of a python in the abdomen of the possessed person (Wilson, 1951). For neither society do we have reports of possession-trance (PT) or trance without possession (T). Again, these two groups differ greatly with respects to general economic, geographic, social, and cultural factors.

I do not wish to labor the point. Our distribution maps contain a great deal of information, but are modest in intent. A map showing the distribution of possession beliefs in Africa, beliefs which are not associated with trance, tells us nothing about the great variety of specific beliefs involved. More refined studies concerning, for example, possession as an explanation of illness still remain to be made. Yet we feel that, by separating PT, T, and P, we have taken a step beyond the broad and undefined categories of either ‘trance’ or ‘possession’ as they occur in ethnographic literature.

As to our eightfold typology, its usefulness has yet to be tested, beyond its application to the plotting of distribution maps. While the types appear to group together some dissimilar phenomena, as our discussion has just attempted to show, we must recognize that our predicament is not peculiar to this particular enterprise. Socio-cultural systems, like individual personalities, are unique, complex wholes, and it is only by abstracting certain common features and ignoring other features that we can ever hope to find any order in our mass of data. The problem is to find the features which, are truly diagnostic with reference to the questions at hand.

Distribution of Trance and Possession States

Africa

With these preliminaries in mind, we may now take a look at the first of our maps.[7] We have found it necessary to utilize a method of sampling that is heavily influenced by the availability of data. However, we have attempted to balance our sample by including materials from all the culture areas of the world, following in this respect Murdock’s ‘World Ethnographic Sample’. We start with Africa because, for a number of reasons, we have made several special studies of African materials. We present three maps, one each for possession, trance, and possession-trance. Possession-trance exists in all culture areas of sub-Saharan Africa, with the exception of the Pygmy and the Bushman-Hottentot areas. Trance is found primarily among the Bushman-Hottentot groups and in the Upper Nile area. It is also found among some groups of the Guinea Coast, particularly in Liberia, and among the Fang and Kpe of the equatorial Bantu. Absence of trance, as well as of possession trance, appears among the Pygmies, as well as in the Nigerial Plateau area, in the Upper Nile, and in neighboring areas of Ethiopia, where there is, however, some evidence of a progressive advance of the possession-trance complex among the Galla. A comparison of the maps reveals a considerable degree of overlap between the distribution of the three groups of traits. This is particularly striking in southeastern Africa, among the Southern Bantu, where possession-trance, possession-illness, and trance coexist in a number of groups.

While the African picture as a whole is highly varied, there is one configuration which recurs again and again and which therefore deserves special mention. This is the cult group in which possession-trance is encouraged and in which women predominate, if not as members, then certainly as trancers. This is exemplified in the complex and elaborate cult groups of the Guinea Coast, in the intertribal societies of East and Central Africa, such as the Cwesi cult, and in the zar cult of Ethiopia and adjoining areas. A great many other examples could be cited, and while there are some important variations, here, the striking common features involve cult organizations, possession-trance, and a predominance of women in the possession-trance activities.

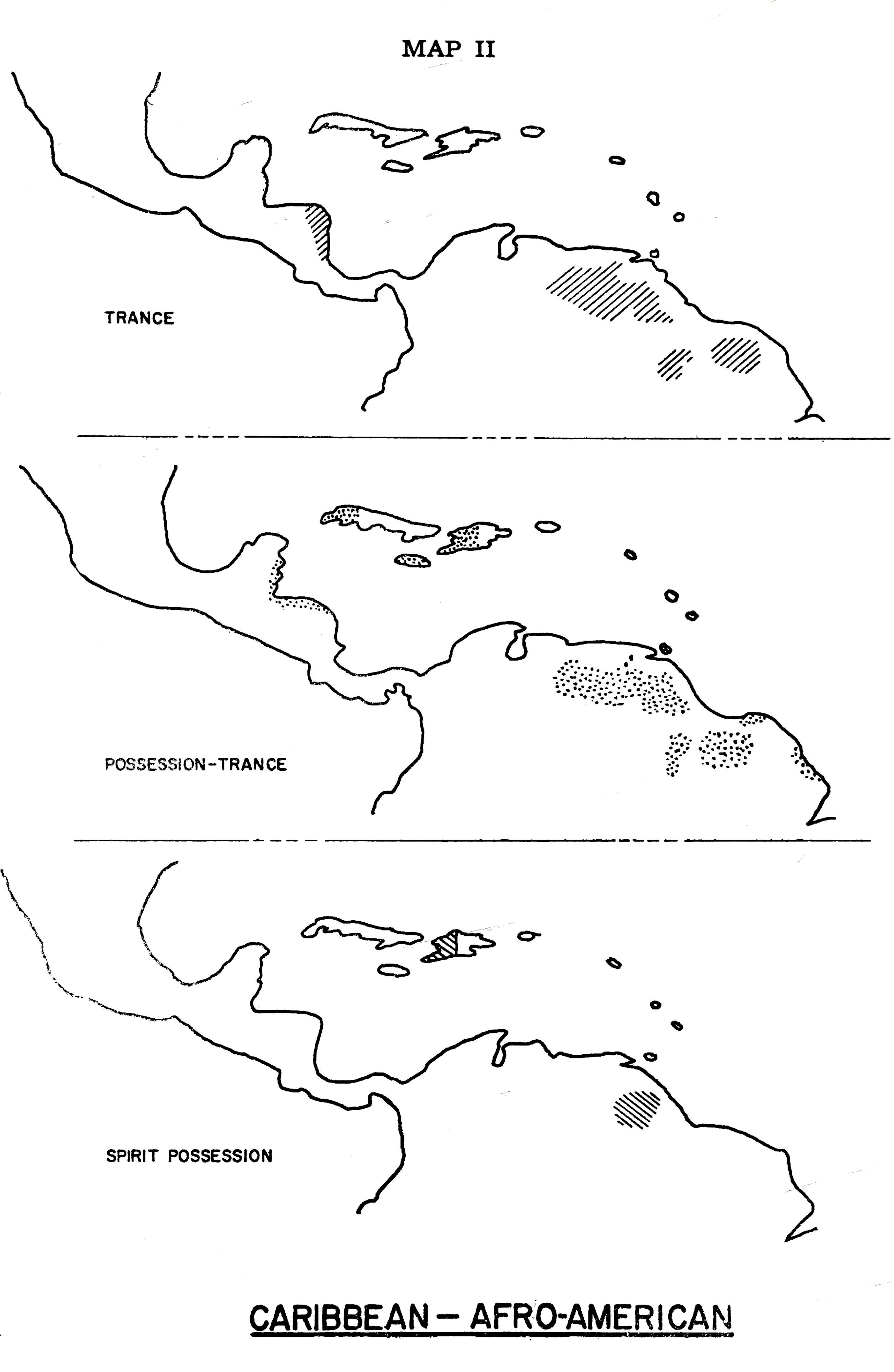

Afro-America

The slave trade, which lasted well into the nineteenth century, distributed the pattern described above into that portion of the New World which is referred to as Afro-America (Map II) and

into the Islamic areas adjoining Negro Africa. In Afro-America, cult groups of varying complexity have been reported in the Caribbean area and coastal Brazil. It is likely that New Orleans once represented an outpost of such cults in the United States. The Afro-American cults are heavily overlaid with Christian syncretism and there is a good deal of regional variety. It is striking, however, that while such cult groups have been described for Cuba, Jamaica, Haiti, Trinidad, the Guianas, and coastal Brazil, there appears to be a notable absence of such groups in the Dominican Republic, in Puerto Rico, and in the smaller islands from the Bahamas through the Virgin Islands to the Lesser Antilles. The reasons for this unsual absence will have to be sought in historical and socio-cultural factors. In Cuba, in Puerto Rico, and probably elsewhere, there is an important element of spiritualism which involves possession-trance séances (but no dancing or active group participation) and which is largely devoted to therapeutic tasks. The role of evangelistic Protestantism, with possessions by the Holy Ghost, is beginning to be investigated more closely throughout this area. In the United States this represents one institutional area, for bo th Negroes and whites, where possession-trances find expression.

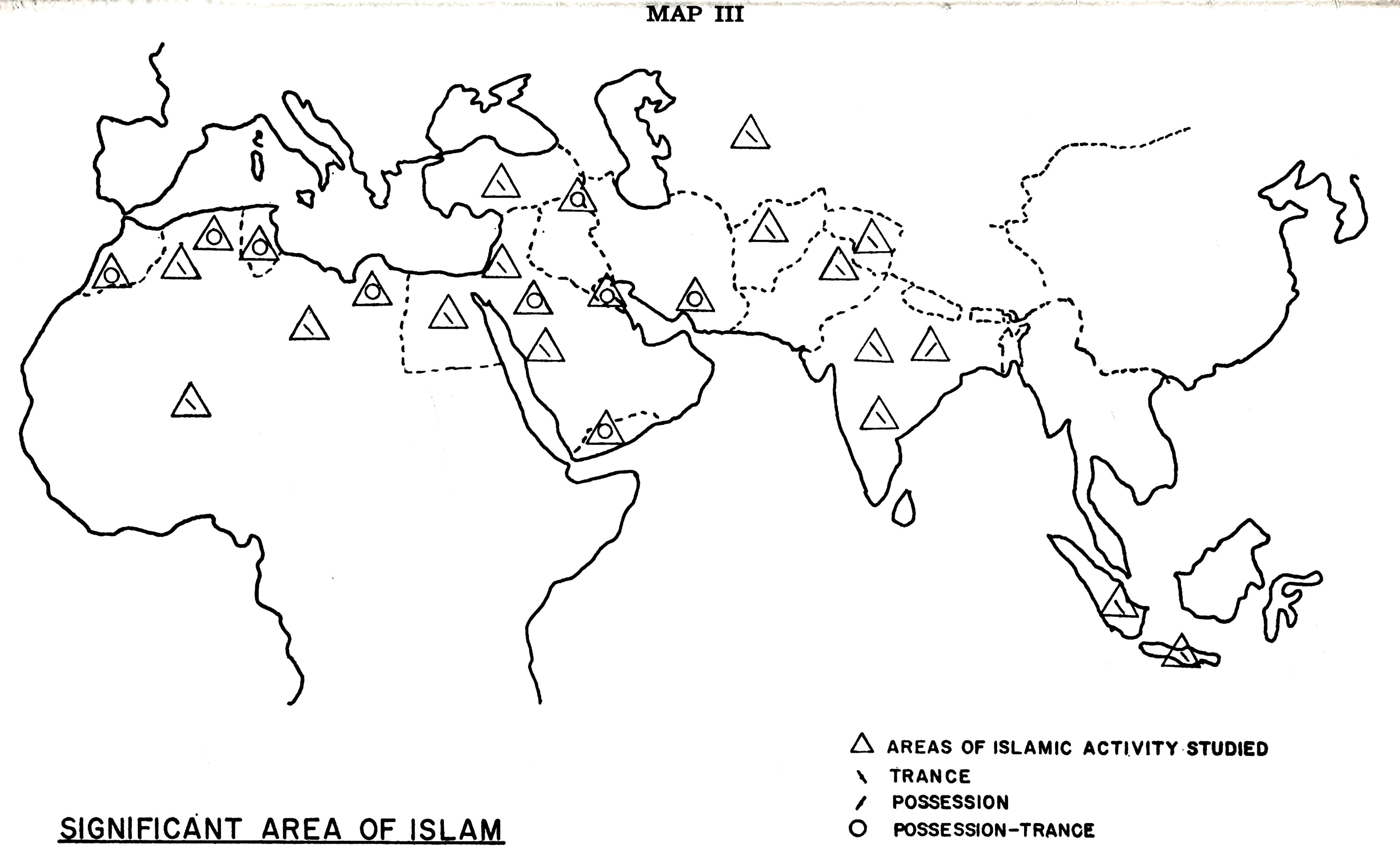

Islamic Area

The other area into which Negro-African religions have expanded is that of Islam. Both the zar cult and the Negro Islamic brotherhoods of North Africa (in which women frequently play an important role) show an extension of the cult group, possession-trance pattern to the north and east of the Negro-African area (Paques, 1965).

Islam, like the other world religions, presents us with a difficult problem. Its broad area of diffusion reaches from Northwest Africa to Indonesia. It has placed the stamp of a ‘Great Tradition,’ in Redfield’s terminology (1956), on a great many peoples of diverse history and culture. On the village level, we still find an expression of the local Little Traditions, though often tightly wed to elements from the general Islamic Great Tradition. Map III indicates our sampling in a major segment of this vast area.

Among the generally shared patterns to be observed among Islamic peoples, we find the presence of Moslem brotherhoods with their exercises of meditation and breathing, notably expressed in the zikr, which is practised in Indonesia and in Morocco. Trance states are at times sought and achieved in these exercises (Landolt, 1965). Self-torture, such as flagellation, occurs in the context of pilgrimages (Chelod, 1963) and this, too, rnay lead to ecstatic states. Such practices, as well as breathing exercises or meditational exercises, are characteristically absent in Negro Africa. We also find a very widespread belief in diseases caused by possession by a jinn or sheitan, and these require exorcism. Such beliefs and practices connected with illness recur among people as distant from each other as the Tuareg and the Kurds, as well as among the Bedouins of the Negev, but need not be connected to any type of trance behavior. In the exorcism which these beliefs call for (again in contrast to Negro Africa), whipping of the patient may be resorted to (Chelod, 1965). On the other hand possession by certain souls of the dead, which permit the trancer to establish communication between his clients and the departed, seems to be a rarer phenomenon, notably reported from Egypt (Winkler, 1936). The zar cult, as already mentioned, has established itself not only among Negroes but also among Egyptian women of various classes, and was made to accept syncretic Moslem elements (Salima, 1902). It is also found in Arabia, in Kuwait, and in Southern Iran, as well as in Ethiopia and in Somaliland.

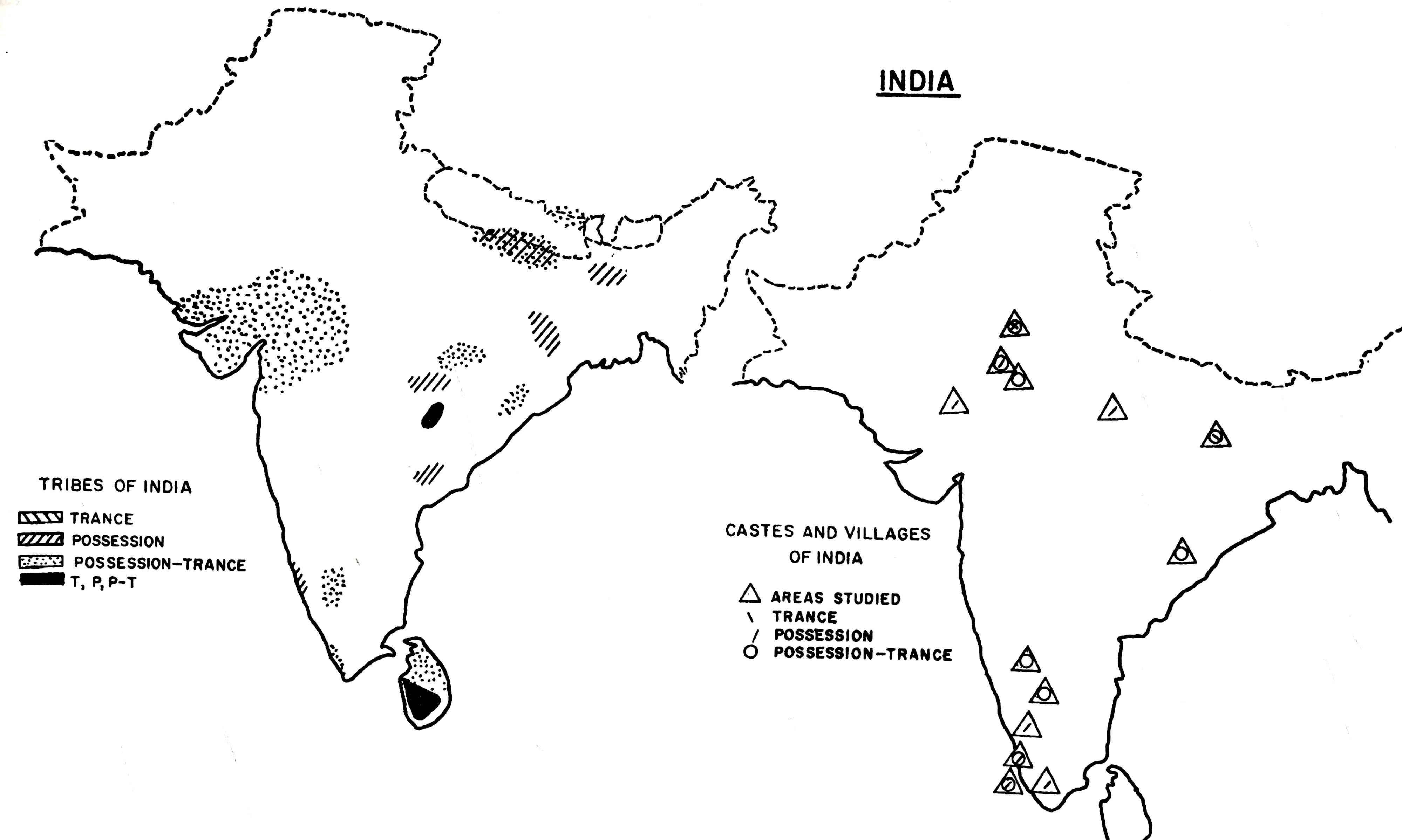

India

We may move on to look at the distribution map of the Indian subcontinent (Map IV). Here the symbols on a single map distinguish the presence and the co-existence of the patterns under consideration. In this area, in addition to the presence of Islam (in India as well as in Pakistan), we find the Hindu Great Tradition, not to mention various local traditions, on the village level as well as among other tribal peoples. The data are sometimes reported in terms of a particular village or in terms of a particular region, and sometimes in terms of a particular caste or sub-caste, which may have a sizable regional extension. We have attempted to express all information on villages, caste groups, and tribal groups in purely geographic terms for the purposes of this quick survey.

Trance and possession-trance related primarily to meditation and to the festivals of the great Hindu gods occur in the context of the Hindu tradition. On the village level we find possession illness and possession-trance illness, as reported by the Freeds (1962, 1964) and by Opler (1958), among others. The victims frequently appear to be young women. Possession-trance also occurs in a positive form, in a diagnostic and therapeutic context, in the person of the healer or diagnostician. In Bengal and Madras, possession-trance appears to center around the worship of Kali, and this practice has been strongly established in the New World in British Guiana by Indian migrants (Rauf, n.d.). Similarly, possession illness has been reported among Indians in Trinidad (Klass, 1961), where some syncretism with African-derived patterns « appears to have taken place.

While trance patterns and possession beliefs have not been reported for some of the tribal peoples of India, for example the Chenchu (von Fiirer-Haimendorf, 1943), they have been reported for many others, as the map shows. We may once again refer to the contrasts with Africa: possessing, illness-causing spirits may be questioned in trance and their demands may be met, as in the zar cult; but unlike the latter, the aim here is the expulsion of the troubling spirit. Sometimes, beatings and fumigations may be resorted to in an effort to drive out the spirit and these, as newspaper reports occasionally show, may have disastrous consequences for the patient. There are no cult groups and there is no accommodation with the spirits. The mediumistic aspects of possessiontrance are prominent in India, among tribal peoples as well as among villagers (cf. description of Bhil shamans in Hermanns, 1964).

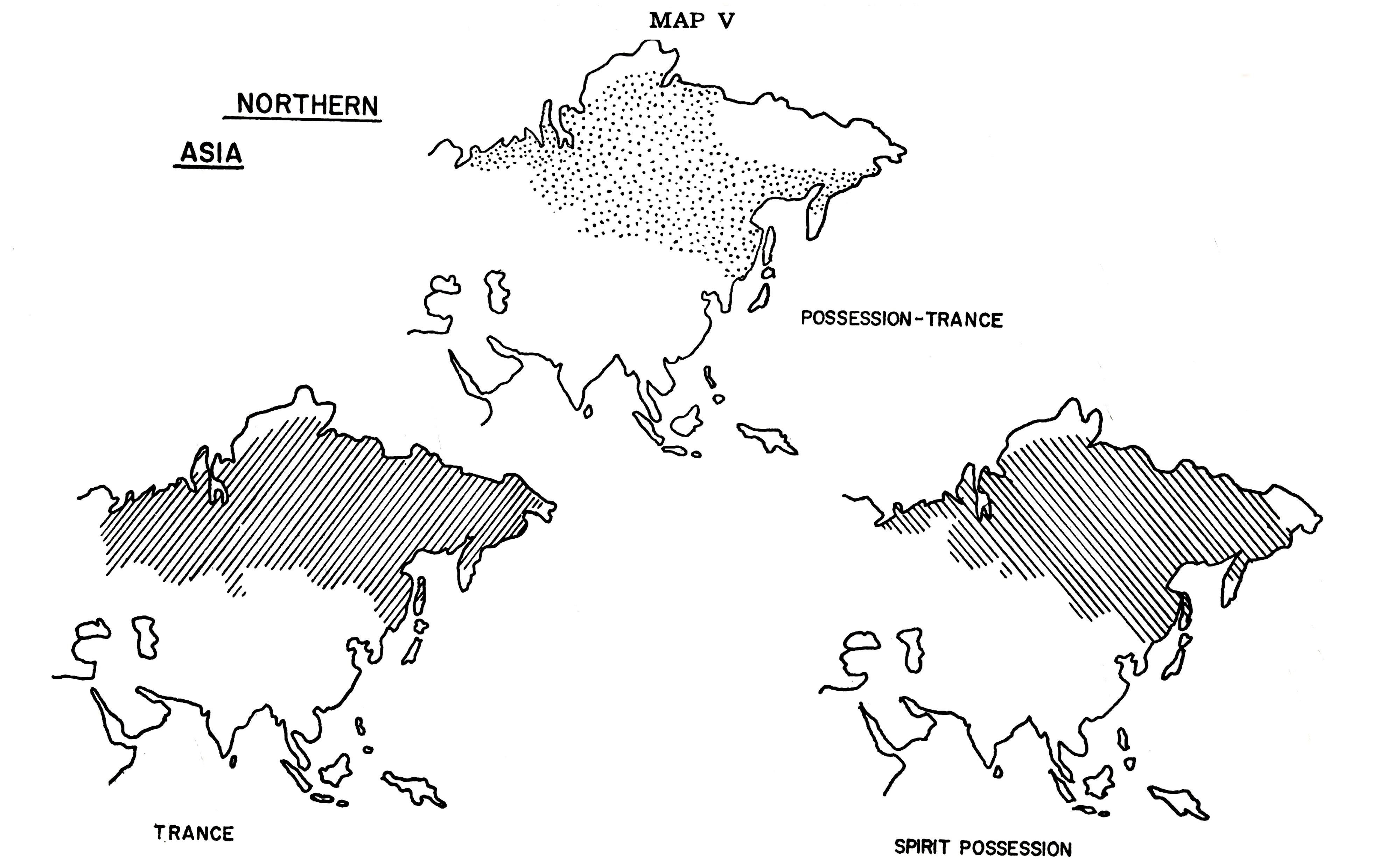

Northern Asia

Mediumistic patterns are widespread in other portions of Asia as well (Map V). Once again, we have three maps which present PT, T, and P separately. It is interesting to speculate to what extern the mediumistic processes in this area derive from tie great shamanistic tradition of the circumpolar regions. This has been shown clearly by Shirokogoroff (1935) for the Manchus. The Chinese varieties of mediumism were brought by Chinese migrants to Singapore, to Hong Kong, and to Hawaii, where they have been documented. Chinese influence also appears in the mediumistic traditions of Southeast Asia, Korea, and Japan, although it appears likely that in all these regions indigenous patterns were overlaid with Chinese syncretic influence. In addition to mediumistic possession-trances, we find references to possession by fox spirits in China and Japan, and these involve a context of deviancy and/or illness (Yap, 1960). The circumpolar region, which includes the Eurasian and American Arctic, is, of course, the classical area of shamanism, where we find both soul-loss illness and possession illness, as well as shamanistic trances which involve either possession of the shaman by various spirits or the absence of one of the shaman’s souls, which travels in search of information or to retrieve the lost or stolen soul of the parient. Sometimes, however, it is not the shaman’s soul which makes the trip, but rather one or more of the shaman’s familiar spirits. The shaman’s performance may be very elaborate and theatrical, the prime content being a report of his trip, a conversation with the various spirits, or communication by the spirits. There are striking similarities here with shamanism among, for example, the Senoi-Semai of Malaya and some South American groups. Depending on the tribe, shamans may be male or female, and some transvestites have been reported. Asiatic shamanism reaches into Europe in Hungary, in Finland, and in Lapland. Interestingly, it has been reported that Lapp Protestantism has a peculiar character, with ecstatic states that are unknown to the neighboring Swedes (Pearson, 1949).

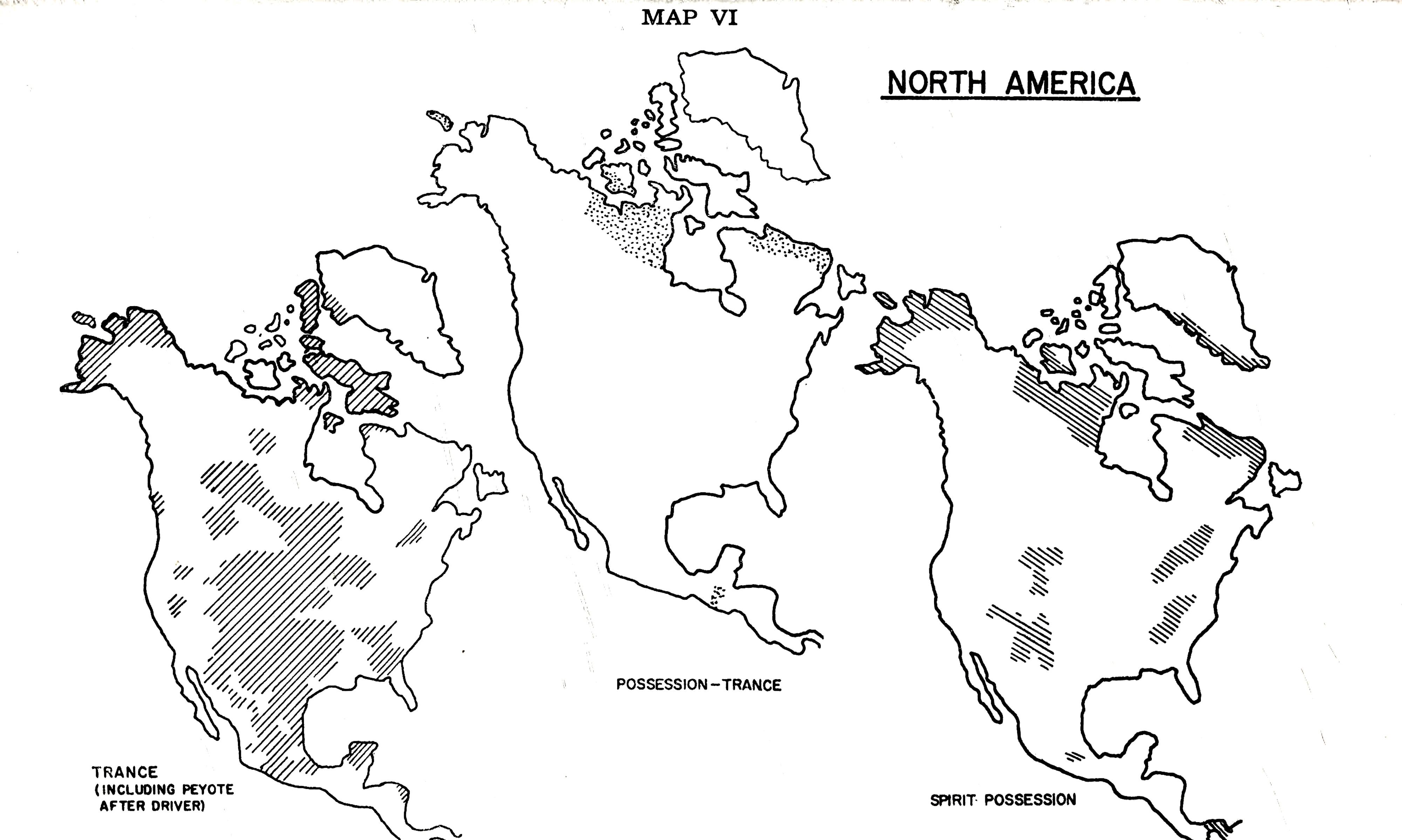

North America

In our quick survey we now rush on to North America (Map VI). Here we may distinguish between, on the one hand, the Eskimo, whose shamanistic patterns clearly relate them to the remainder of the circumpolar region, and, on the other hand, North American Indians. While there is a great and voluminous ethnographic literature on North American Indians, the materials relating to trance and possession are particularly difficult to interpret. While it was long believed that possession illness was absent in North America (e.g., Koeber, 1962), Teicher (1960) has demonstrated that this is not quite so, by showing that some reports of windigo psychosis among the Indians of northeastern Canada do refer to possession by a windigo spirit, rather than to the patient’s turning into a windigo spirit. Illness has sometimes been explained as possession by a power, as in the previously mentioned case of the Navaho (op. cit., Kaplan and Johnson). However, it is true that soul-loss and object-intrusion were much more widespread as explanations of illness in North America and in South America as well. There are many references in the literature on North American Indians to visions and to the vision-quest, and while the distinction is not always made between visions and dreams, it is clear that in a good many instances we are dealing with visions occuring in trance states, states brought on by fasting, isolation, self-mutilation, etc. The use of biochemical inducers of trance and vision states is now widespread in the Peyote cult, but this has its pre-Columbian precursors both in the southwestern United States and in Mexico. Trance states were clearly part of the shamanistic patterns of some Indian groups, such as the Yorok of California, and possession-trance appears to be clear-cut among the Kwakiutl of the Northwest Coast.

However, the whole matte of possession-trance has given us so much difficulty with reference to North America, that we have preferred to omit it from the present mapping. (A very peculiar instance is found among the Acoma Indians of the Southwest, where, Leslie White implies (1932), the masked dancers are believed to be possessed by the visiting katchina spirits, although there is no indication that they are in trance.) Much North American shamanism, we must repeat, appears to have been of the non-inspirational type, and although shamans communicated with spirits, sent their spirit-helpers on trips, and performed various sleight-of-hand tricks reminiscent of the activities of the arctic shaman, there are few references here to true trance or to any belief in possession.

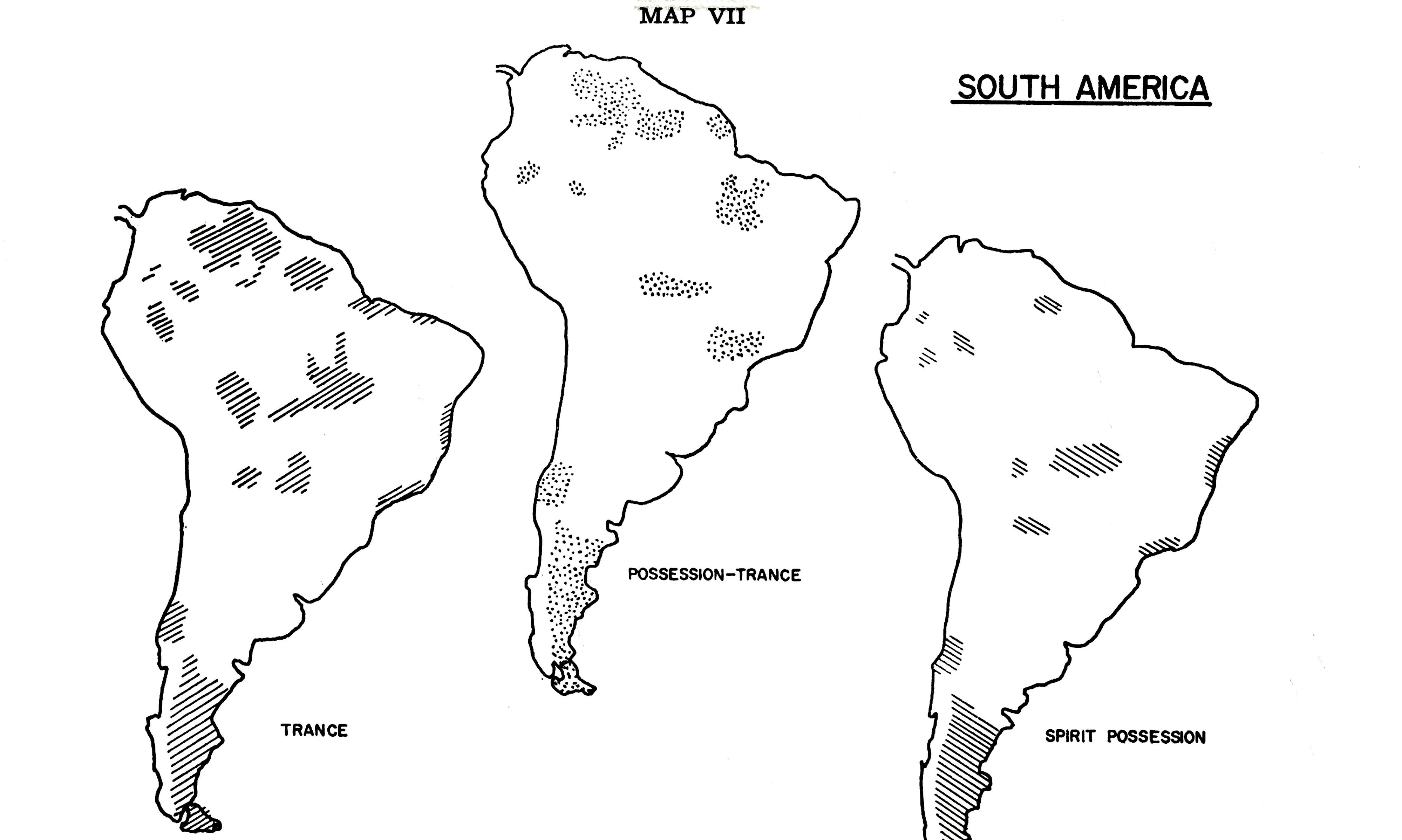

South America

Among South American shamans, on the other hand, trance activities were, and to some extent are, widespread, as our next group of maps shows (Map VII). Various drugs and tobacco were used to induce these states, some of which may have involved prolonged unconsciousness (op. cit., Dole). Possession beliefs, whether or not associated with trance, appear to have been relatively rare. One group for whom they have been reported are the Aymara, and LaBarre (1948) links a belief in possession

illness among these people to trepanations practised among them in pre-Columbian times. However, there is no reference here to possession-trance. Indian shamanistic practices have been syncretized with Afro-American cult practices in the Amazon area of Brazil (Leacock, 1964) and among the Black Caribs of British Honduras (Taylor, 1951).

Judeo-Christian Tradition

While this very rapid survey of the worldwide distribution of possession and trance states makes no claim to completeness, we must make one more brief reference, and that is to the Judeo-Christian tradition. We have made no attempt at mapping the area involved, bi t we have already had occasion to refer to this tradition several times in the context of syncretism. The New Testament makes ample reference to possession illness and exorcism, and ideas of demoniac possession have been accumulating ever since the time of Christ, in Judaism, in Catholicism, and in Protestantism. The French psychiatrists of the nineteenth century were very much interested in these phenomena, particularly in connection with their studies of hysteria. These beliefs are still very influential, not only in a religious context, but even as a theme in films, in novels, and in other areas of popular culture. Apart from possession states, mystic trance states have a long and complex history in the Western world. The concept of mystic states has recently been somewhat secularized in the term ‘peak experiences’ (Maslow, 1964), as well as in the pursuit of psychedelic experiences through drugs. Eastern techniques of meditation have made inroads in Europe and America, as for example in the Subud sect, which originated in Indonesia (Kiev and Francis, 1964, for England; Pfeiffer, 965, for Germany).

While we have centered our attention here on traditional, so-called primitive societies, the problems of trance in its naturalistic and supernaturalistic interpretations are clearly of considerable relevance even in the modern world.

References

Belo, Jane (1960). Trance in Bali. New York.

Boas, Franz (1930). The Religion of the Kwakiutl Indians. Columbia Contributions of Anthropology, Number 10, Part 2. New York.

Bogoras, Waldemar (1967). The Chukchee Religion. Memoirs of the American Museum of Natural .History, Number I Part 2. New York.

Carneiro, Robert L. (1964). The Amahuaca and the Spirit World, Ethnology, 3: 6–11.

Chelod, Joseph (1963). Pélérinage à Kadzimain, lieu saint d’Islam, Objets et Mondes, 3: 253–60.

(1965). Surnaturel et guérison dans le Négueb, Objets et Mondes, 5: 149–73.

Dentan, Robert. MS. Senoi-Semai Mental Illness.

Dole, Gertrude E. (1964). Shamanism and Political Control among the Kuikuru, Völkerkundliche Abhandlungen, 1: 53–62.

Evans-Pritchard, E. E. (1937). Witchcraft, Oracles and Magic among the Azande. Oxford.

1936). Zande Theology, Sudan Notes and Records, 19: 1–46. Reprinted (1964) in Social Anthropology and Other Essays. New York.

Field, M. J. (1960). Search for Security. Evanston.

Freed, Ruth S., and A. Stanley (1962). Two Mother Goddess Ceremonies of Delhi State in the Great and Little Traditions, Southwestern Journal of Anthropology ? 18: 246–77.

(1964). Spirit Possession as Illness in a Northern Indian Village, Ethnology, 3: 152–71.

Fürer-Haimendorf, Christoph von (1943). The Chenchus. London.

Gillin, John (1948). Magic Fright, Psychiatry, 11: 387–400.

Halowell, A. Irving ‘1942’. Conjuring in Salteaux Society. Philadelphia.

Harner, Michael J. (1962). Jivaro Souls, American Anthropologist, 64: 258–72.

Hermanns, Matthias (1964). Die Bhagoria Bhil. Wiesbaden.

Heusch, Luc de (1962). Culte de possession et religions initiatiques de salut en Afrique, Religions de salut. Annales du Centre d’Etudes des Religions, 2. Brussels.

Kaplan, Bert, and Dade L. Johnson (1964). The Social Meaning of Navaho Psychopathology and Psychotherapy, in Magic, Faith, and Healing, ed. Ari Kiev. New York.

Kiev, Ari, and J. L. Francis (1964). Subud and Mental Illness: Psychiatric Illness in a Religious Sect, American Journal of Psychotherapy, 18: 66–78.

Klass, Morton (1961). East Indians in Trinidad. New York and London.

Kroeber, A. L. (1962). A Roster of Civilizations and Cultures. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, Number 33.

LaBarre, Weston (1948). The Aymara Indians of the Lake Titicaca Plateau, Bolivia. Memoirs of the American Anthropological Association, Number 68.

Landolt, Hermann (1965). Mystical Experiences in Islam, Proceedings of the Conference on Personality Change and Religious Experience, The R. M. Bucke Memorial Society for the Study of Religious Experience.

Leacock, Seth (1964). Fun-Loving Deities in an Afro-Brazilian Cult, Anthropological Quarterly, 37: 94–109.

Leeds, Anthony 1960). The Ideology of the Yaruro Indians in Relation to Socio-Economic Organization, Antropológica, 9: 1–10.

Leiris, Michel (1958). La possession et ses aspects théâtraux chez Ies Ethiopiens de Gondar, UHomme, Cahiers d’Ethnologie, de Géographie et de Linguistique, nouvelle série, numéro 1. Paris.

Lévi-Strauss, Claude (1958), Anthropologie structurelle. Paris.

Lienhardt, Godfrey 1954). The Shilluk of the Upper Nile, in African Worlds, ed. Daryll Forde. London.

Loeb, E. M. (1929). Shaman and Seer, American Anthropologist, 31: 60–84.

Maslow, Abraham (1964). Religions, Values, and Peak Experiences.. Columbus.

Marshall, Lorna (1962). !Kung Bushman Religious Beliefs, Africa, 32: 22152.

Messing, Simon D. (1958). Group Therapy and Social Status in the Zar Cult of Ethiopia, American Anthropologist, 60: 1120–26.

Murdock, George P. (1957). A World Ethnographic Sample, American Anthropologist, 59: 664–87.

Murphy, Jane M. (1964). Psychotherapeutic Aspects of Shamanism on St. Lawrence Island, Alaska, in Magic, Faith, and Healing, ed. Ari Kiev. New York.

Oesterreich, T. K. (1922). Die Bessessenheit. Halle.

Opler, Morris E. (1958). Spirit Possession in a Rural Area of Northern India, in Reader in Comparative Religion, ed. Cessa and Vogt. Evanston.

Pâques, Viviana (1964). U Arbre Cosmique dans la Pensée Populaire et dans la Vie-Quotidienne du Nord-Ouest Africain. Institut d’Ethnologie, Musée de FHomme. Paris.

Pehrson, Robert Neiî (1949–50). Culture Contact without Conflict in Lapland, Man, 49–50, 86–87. London.

Pfeiffer, Wolfgang M. (1965). Versenkungsund Trancezustände bei indonesischen Volksstämmen, Nervenarzt, galley proofs.

Rauf, Mohammed A. Unpublished field notes.

Red field, Robert (1956). Peasant Society and Culture. Chicago.

Rubel, Arthur J. (1964). The Epidemiology of a Folk Illness: Susto in Hispanic America, Ethnology, 3: 268–83.

Selima, Riya (1902). Harems et Musulmanes. Paris.

Shirokogoroff, S. M. 1935). Psychomental Complex oi the Tungus. London.

Snoy, P. (1960). Darden-Nordkestpakistan {Gilgitbezirk)..Shamanistischer Tanz. Filmbeschreibung. Cinematographies, Institut für den Wissenschaftlichen Film. Göttingen.

Spencer, Paul (1965). The Samburu. Berkeley and Los Angeles.

Taylor, Douglas (1951). The Black Caribs of British Honduras. Viking Fund Publications in Anthropology, Number 17.

Teicher, Morton I. (1960). Windigo Psychosis, in Proceedings of the 1960 Annual Spring Meeting of the American Ethnological Society, ed. Verne F. Ray.

Verger, Pierre (1957). Notes sur le Culte des Orisa et Vodun, Mémoire dTfan, numéro 51. Dakar.

White, Leslie (1932). The Acoma Indians. U.S. Bureau of Ethnology, Annual Report, Vol. 47. Washington.

Wilson, Monica (1951). Good Company. Oxford.

Winkler, H. A. (936). Die Reitenden Geister der Toten. Stuttgart.

Yap, P. M. (1960). The Possession Syndrome: A comparison of Hong Kong and French Findings, Journal of Mental Science, 106: 114–37.

The Sociology of !Kung Bushman Trance Performances[8]

Richard B. Lee

Department of Social Relations

Harvard University

Ethnographic Background

The !Kung Bushmen, a non-Bantu, click-speaking people in the Kalahari Desert of Bechuanaland, are one of the last peoples of the world to maintain a hunting and gathering way of life. As such, they offer an excellent opportunity for studying a way of life which was, until 10,000 years ago, the universal mode of human organization. Aspects of !Kung culture have been described by Lorna Marshall (1959, 1960, 1962), and by Elizabeth Marshall Thomas in her wed-known book, The Harmless People (1959).

My field work among the !Kung was carried out from August, 1963, to January, 1965. The focus of the study was an isolated population of 430 Bushmen living in the northwestern corner of the Bechuanaland Protectorate (Lee, 1965).

About 75 per cent of the population were organized into fifteen independent nomadic camps of from ten to sixty individuals each. These camps were entirely dependent on hunting and gathering for their subsistence. They lacked agriculture, firearms, and, except for the dog, domesticated animals. The remaining 25 per cent of the people lived in association with the Bantu cattle posts located in the area. Although this latter 25 per cent subsisted on foods provided by the Bantu, they shared fully in the ritual and religious life which I am going to describe.

The Bushmen of the study population had had minimal direct contact with Europeans prior to my arrival. Officers of the British Colonial Administration made infrequent tours of duty to this isolated area three of four times a year, and missionary influence was completely lacking. However, the Protectorate of Bechuanaland gained independence in September, 1966, and one can expect the tempo of acculturation to increase in the coming years.

Trance in Bushman Ritual Life

The trance phenomenon in the Bushman context is a culturally stereotyped set of behaviors which indices an altered state of consciousness by means of auto-suggestion, rhythmic dancing, intense concentration, and hyperventilation. These exertions produce symptoms of dizziness, spatial disorientation, hallucinations, and muscular spasms. The Bushmen were never observed to use any drug or other external chemical means of inducing these states. The social functions of these trances are to cure the sick, to influence the supernatural, and to provide mystical protection for all members of the group.

The features I want to stress include: (1) the high incidence of trance in the population; (2) the public and routine nature of trance performances; (3) the lack of awe surrounding the performer; (4) the long period of close social contact which characterizes the apprenticeship of a performer; and (5) the unusual native belief that their power comes from men, and not directly from the gods or spirits.

Trance performance is the dominant mode of religious expression among the !Kung. One striking fact is the unusually high proportion of active performers in the population; of the 131 adult males, at least sixty are practising trance performers. I was fortunate enough to see thirty-five of these in action and I learned about twenty-five more during census work. It is likely that I missed a few and therefore would safely estimate that 50 per cent of the male adult !Kung are trance performers.

The trance is not exclusively confined to men. In recent years a drum dance has developed among the women and is gaining

ncreasing adherents. One of the founders of the dance, a woman over eighty years old, was still alive in 1964. However, this paper concerns the Bushman ‘curing dance’. This is the major setting for the trances and is an institution with the deepest roots in Bushman tradition. The curing dance has been recorded from all Bushman cultures and is known to have been practised by the now extinct Cape Bushmen in the eighteenth century (Scl apera, 1930: 202–7). There is no historical basis for suggesting that the !Kung version of the curing dance is a cult which arose as the result of outside acculturation pressure.

Spatial Arrangements in the Dance

The dancing circle has a tight symbolic organization. In the center is the fire, representing medicine. It must be kept burning throughout the all-night dances. Surrounding the fire and within the circumference of the circle, the women sit shoulder to shoulder facing inwards. Primari y, the women sing, and dance only occasionally. The men dance in the circular rut, stamping around and around, hour after hour, now clockwise and now counter-clockwise. Beyond these two tight circles of singers and dancers, sit the spec tators, the chi dren, and the dancers who are temporarily resting.

Division of Sex Roles in the Dance

There is a basic asymmetry of roles in the curing dance. Only the men dance and enter trances. Therefore, the emotional satisfaction derived from the trance experience is confined to the men. Yet the participation of the women is fundamental, for it is they who provide the musical framework which makes the trance experience possible. The men are quick to acknowledge this, and say that the success of the dance is dependent on the perseverance and sustained enthusiasm of the women.

Scheduling of Dances

Apart from a male initiation ceremony, called choma, which takes place during the winter every four or five years, the Bushmen have no ceremony which is tied to the annual cycle, such as the first-fruits rituals of the Australian aborigines. The Bushmen dance at all seasons of the year, winter and summer, with no discernable changes in frequency.

There are, however, marked differences between camps in the frequency of occurrence of dances. Small camps, of less than twenty people, held dances about once a month. Large camps, with forty to sixty people, danced about once a week. At one camp, a camp which had a reputation for fine music, dances occurred as often as four nights a week. There is some indication that the Bushmen prefer to dance at the time of the full moon, but I could discover no reason for this preference beyond the fact that the light is better.

A dance is a major all-night affair that involves the majority of the adult members of the camp. It is worth noting that the dance is a social and recreational event as well as a context for trance performances. Many of the younger men dance for no reason other than to show off their fine footwork. There is a juxtaposition of the sacred and the profane in the dance, with the intense involvement of the trance performers contrasting with the background of casual social chatter, laughter, and flirtation.

A dance will spring up spontaneously if the informal organizers can talk up enthusiasm for it. Three kinds of circumstances favor its initiation:

1) The presence of meat in a camp. The Bushmen are conscientious though not particularly success J hunters. Often days go by when their diet consists solely of wild vegetable foods. When a large antelope is killed and its meat is shared out among the camp members, a dance is likely to occur. I might add that there was no explicit suggestion of giving thanks to the deity or of ensuring success in future hunts. The main rationale seemed to be: since there is abundant food in the camp today, we can afford to dance all night without being concerned about the necessity of going out for food tomorrow.

2) The arrival of visitors. The joy of seeing old friends from other camps and the presence of a number of visiting trance performers in the camp usually provide sufficient incentive for holding a dance.

3) The presence of sickness in a camp. Trance performers will come from far and wide to work on a patient.

Typical Dance-Trance Sequences

The dance begins about two hours after dark when a handful of women light the central fire and begin to sing. The songs are sung without words, in the form of yodelling accompanied by syncopated hand-clapping. There is a genera ly-known repertoire of about ten named songs (each commemorating game animals or natural phenomena), such as the Giraffe, Rain, God, and Mongongo Nut.[9] Each has a recognizable tune and associated dance steps, although there is no attempt to imitate in the dance the behavior or locomotion of the animal denoted by the name of the dance.

One can distinguish five phases of trance.

Phase I — Working Up — chaxni chi (‘dance and song)

Soon after the women begin singing, some of the men enter the circle to dance. The elements of the men’s dancing are: (1) tight, lunched posture; arms close to the sides and semi-flexed; parsimony of movement; body stiff from the waist up; (2) short, heavy footfalls, describing complex, rhythmic figures built on quarterand eighth-notes, into five- and seven-beat phrases; (3) objects used include chains of rattles tied around the ankles, a walking stick to support the torso, and a fly whisk; (4) men move in a line around the circle, occasionally reversing direction.

A dance lasts from five to ten minutes, after which there is a short break followed by another dance of equal length. The women determine the beginning and tie end of each number and the choice of songs. For the first two hours of dancing the atmosphere is casual and jovial.

Phase II — Entering Trance — n/um n/i nluma (‘causing medicine to boil’)

Several of the dancers appear to be concentrating intently; they look down at their feet or stare ahead without orienting to distractions around them. The body is tense and rigid. Footfalls are heavy, and the shock waves can be seen rippling through the Y

body. The chest is heaving, veins are standing out on the neck and forehead, and there is profuse sweating. This phase lasts from thirty to sixty minutes.

The actual entrance into trance may be gradual or sudden. In the first instance, the trancer staggers and almost loses balance. Then other men, who are not in trance, come to his aid and lead him around in tandem until the trancer shouts and falls down in a comatose state, a state called ‘half death’ by the Bushmen. The sudden entrance, on the other hand, is characterized by a violent leap or somersault and an instant collapse into the ‘half death’.

Phase III — ‘Half Death’ — Kweli (‘like dead’)

Now the trancer is stretched out on the ground outside the dance circle. While the others continue dancing, some men work over the trancer. They rub his body with their hands and with their heads. The purpose of this is to keep the body warm and to make it shine with sweat. The trance performer is rigid, with arms stiff at the sides or extended. His body may be trembling and he is moaning and uttering short shrieks.

It is noteworthy that many of the older medicine men, with years of experience in trance states, do not go through the ‘half death’ phase.

The culmination of the trance episode occurs when the performer rises up to move among the participants and spectators to ‘cure’. The technique used is ‘the laying on of hands’. The performer’s eyes are half closed. He staggers, but never loses his balance completely. He rubs the subject with trembling hands and utters moans of rising intensity, punctuated by abrupt piercing shrieks. The trance performer goes from person to person repeating this action, ensuring that every person present is treated. He may break off curing to dance for a few minutes and this appears to reinforce the t’anced state and to forestall a premature return to the normal state. If there is a sick person present at the dance, each trance performer will make a special effort, often giving from ten to fifteen minutes of treatment to this one individual.

The active curing phase lasts about an hour, after which the trance performer usually lies down and falls asleep. It is common for medicine men to have two trance episodes per night, one around midnight and the other just after dawn. The dance continues all night, reaching a peak of intensity between midnight and 2 a.m., when the maximum number of medicine men are in trance. It slackens off in the predawn hours and then builds up to full strength again at sunrise with a renewed round of trances. The dance continues until midmorning and usually terminates by 10 or 11 a.m. Some memorable dances, however, continue throughout the day and into the following night, terminating thirty-six hours after they have started. What makes these marathon dances possible is the constant change-over of personnel. Although there are always from ten to thirty people actively participating in the dance, individuals are constantly entering or leaving the circle in four-to six-hour shifts.[10]

Variations in Trance

Throughout southern Africa the Bushman trance performances are known for their dramatic and mystifying forms of behavior such as fire-walking, fire-handling, and running amok. I observed many such episodes during my field work. However, it should be emphasized that such behaviors were not typical of the mature trancers of long experience. These violent exertions were largely confined to the young novices who would plunge into trance and exhibit uncontrolled reactions. They had to be forcibly restrained by the older men from injuring both themselves and others. The discipline displayed by the older men is the result of years of training, during which they learn to bring their reactions under control.

Fire-walking and fire-handling are the most dramatic forms of behavior among the novices. A dancer who is entering trance will breach the inner circle of seated women and dance through the flames of the central fire, scattering coals on the singers. Or he may reach into the fire, pick up handfuls of live coals, and rub them on his chest, face, and head. The latter action singes the eyelashes and eyebrows, and sets the hair on fire. Variations include somersaulting, squatting, kneeling, and crawling in or through the fire. Direct contact with fire varies in duration from one to five seconds, and often produces burns.

Another characterictic behavior of the novice is to run out of the camp into the bush at top speed. If he is not caught and dragged back to the dance, the novice may scratch himself severely or crash headlong into a tree. These exertions are regarded by the society as expectable of trancers who cannot yet control their medicine.

Several behavioral patterns occurred on only one occasion. I offer this list as an indication of the range of behavioral patterns defined as unusual by the Bushmen: (1) attacking a dog, grabbing it by the hind legs, and flinging it into the bush; (2) retching violently at the moment of entering the trance; (3) acting out sexual intercourse by pelvic thrusts; and (4) attempting to expose the genitals. All these actions were strongly disapproved of and the respective actors were forcibly restrained.

Folk View of Trance Performances