Richard B. Lee & Irven DeVore

Man the Hunter

The First Intensive Survey of a Single, Crucial Stage of Human Development—Man's Once Universal Hunting Way of Life

1. Problems in the Study of Hunters and Gatherers

The Representativeness of Our Sample of Hunters

Social and Territorial Organization

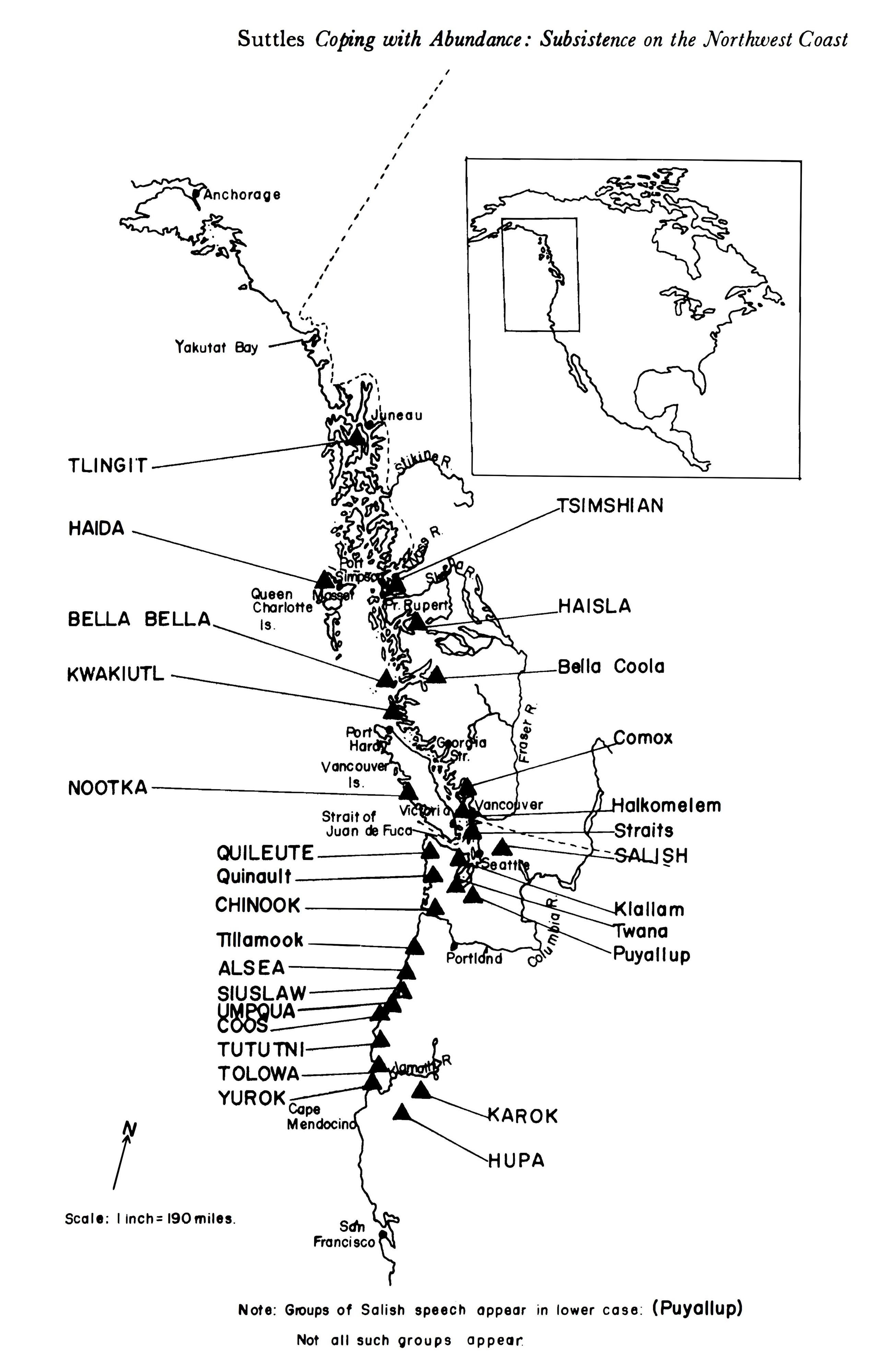

Flexibility and the Resolution of Conflict by Fission

Order and Chaos in Hunter-Gatherer Society

Marriage Arrangements in Australia

Demography and Population Ecology

“Nomadic Style”: A Trial Formulation

2. The Current Status of the World’s Hunting and Gathering Peoples

Part II: Ecology and Economics

4. What Hunters Do for a Living, or, How to Make Out on Scarce Resources

Abundance and VarieD’ of Resources

Range Size and Population Density

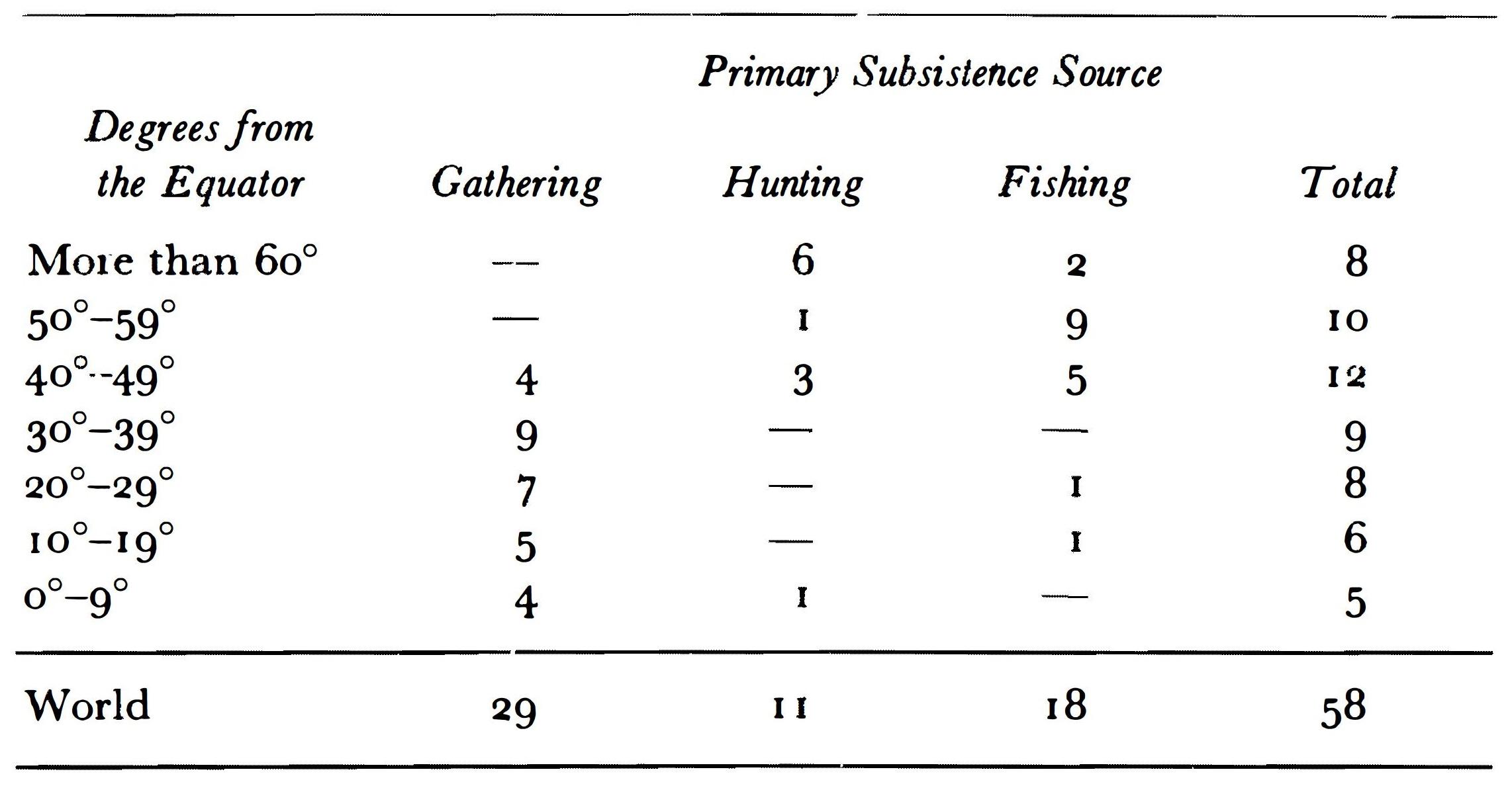

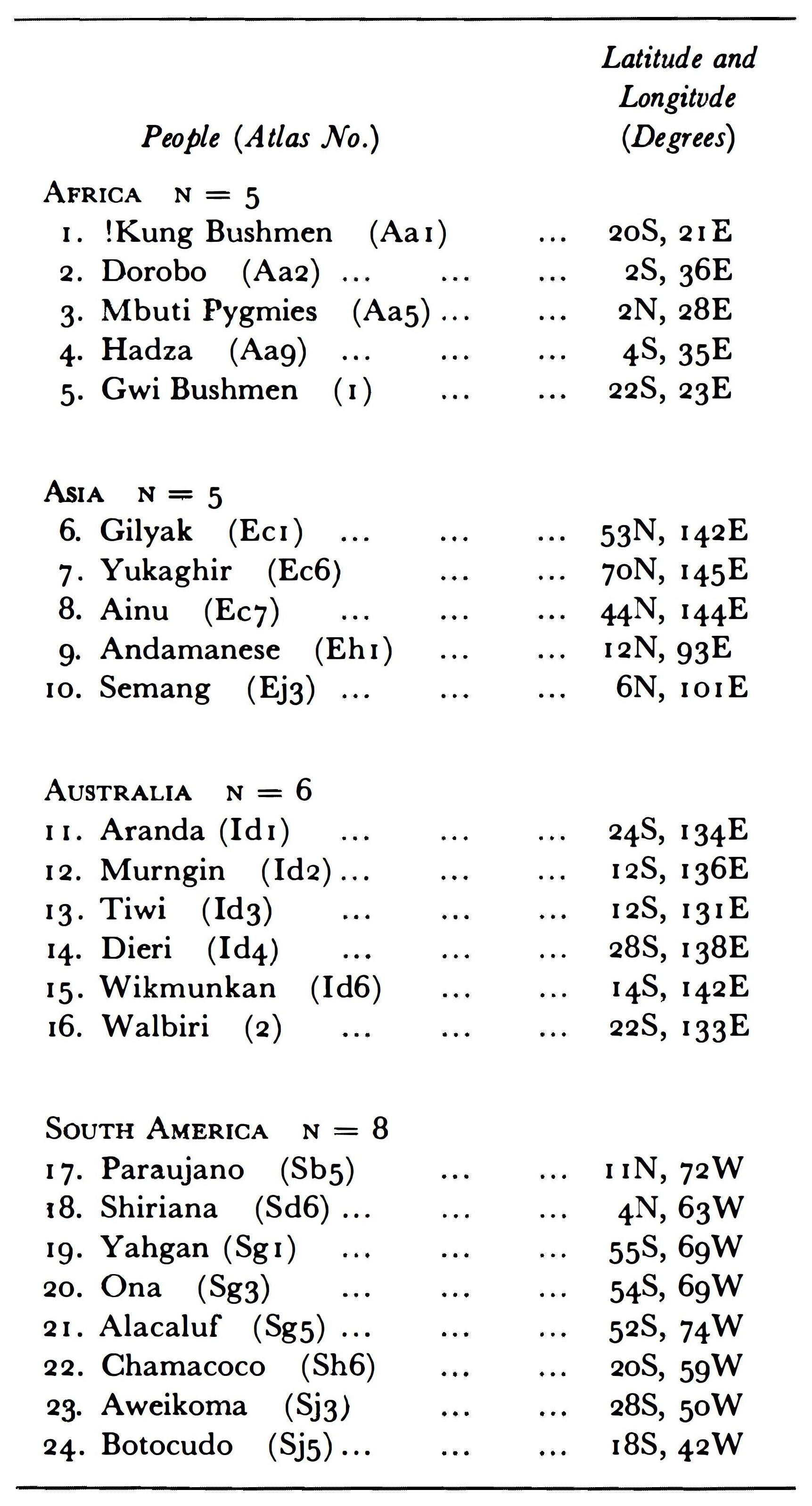

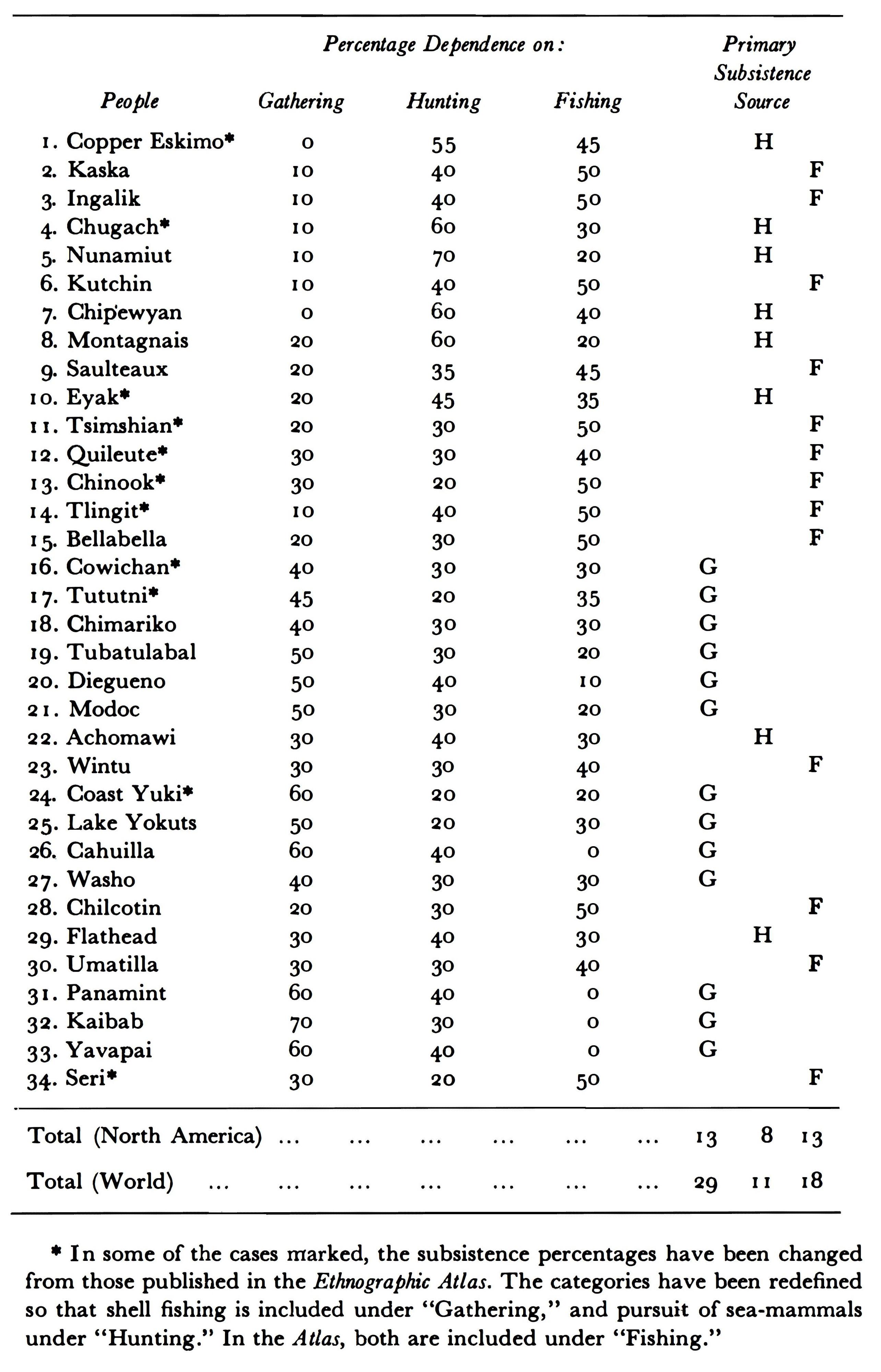

What Hunters Do for a Living: A Comparative Study

The Relation of Latitude to Subsistence

5. An Introduction to Hadza Ecology

6. Coping with Abundance: Subsistence on the Northwest Coast

Values and Social Organization

7. Subsistence and Ecology of Northern Food Gatherers with Special Reference to the Ainu

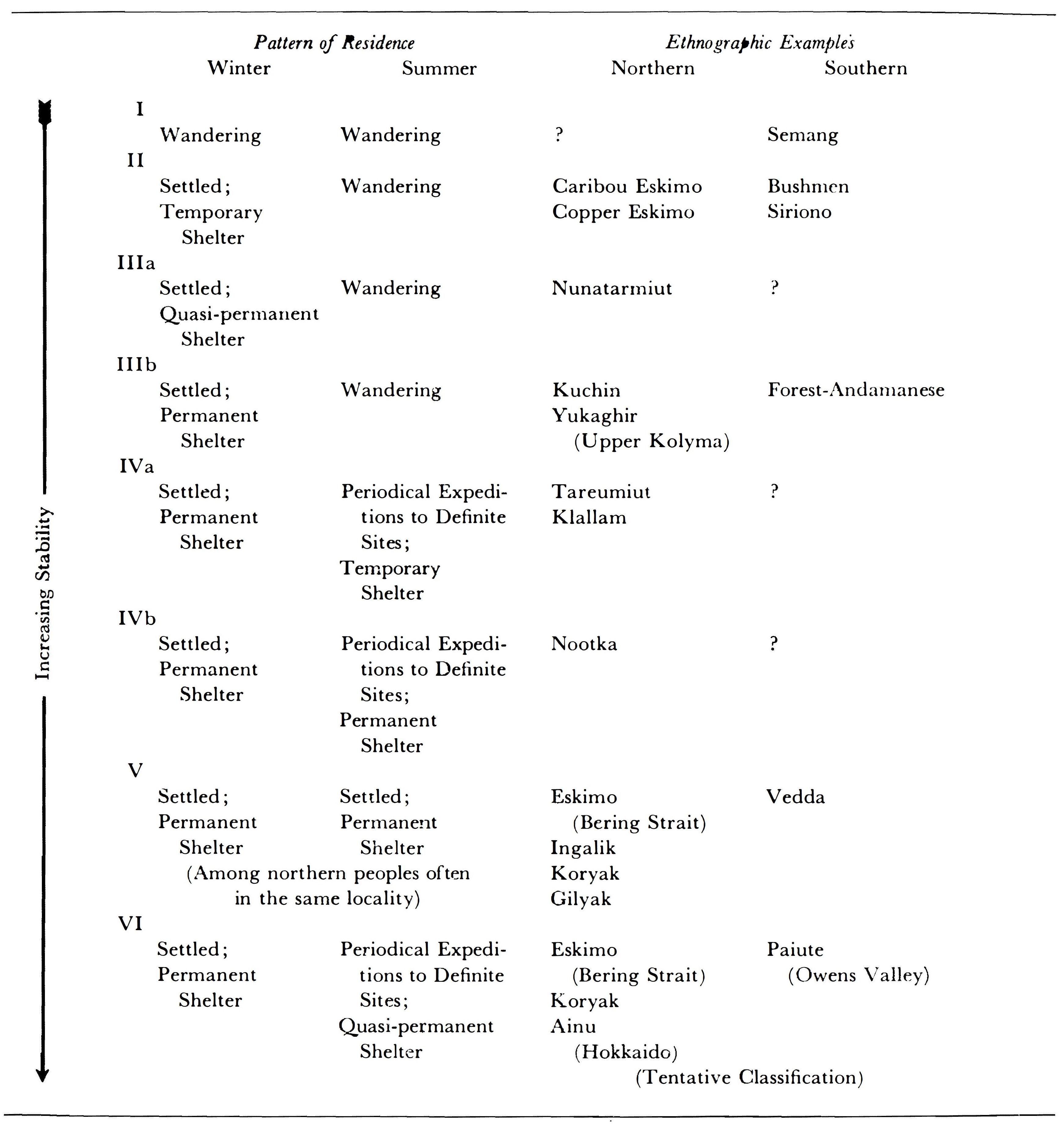

The Problem of “Semi-Nomadism”

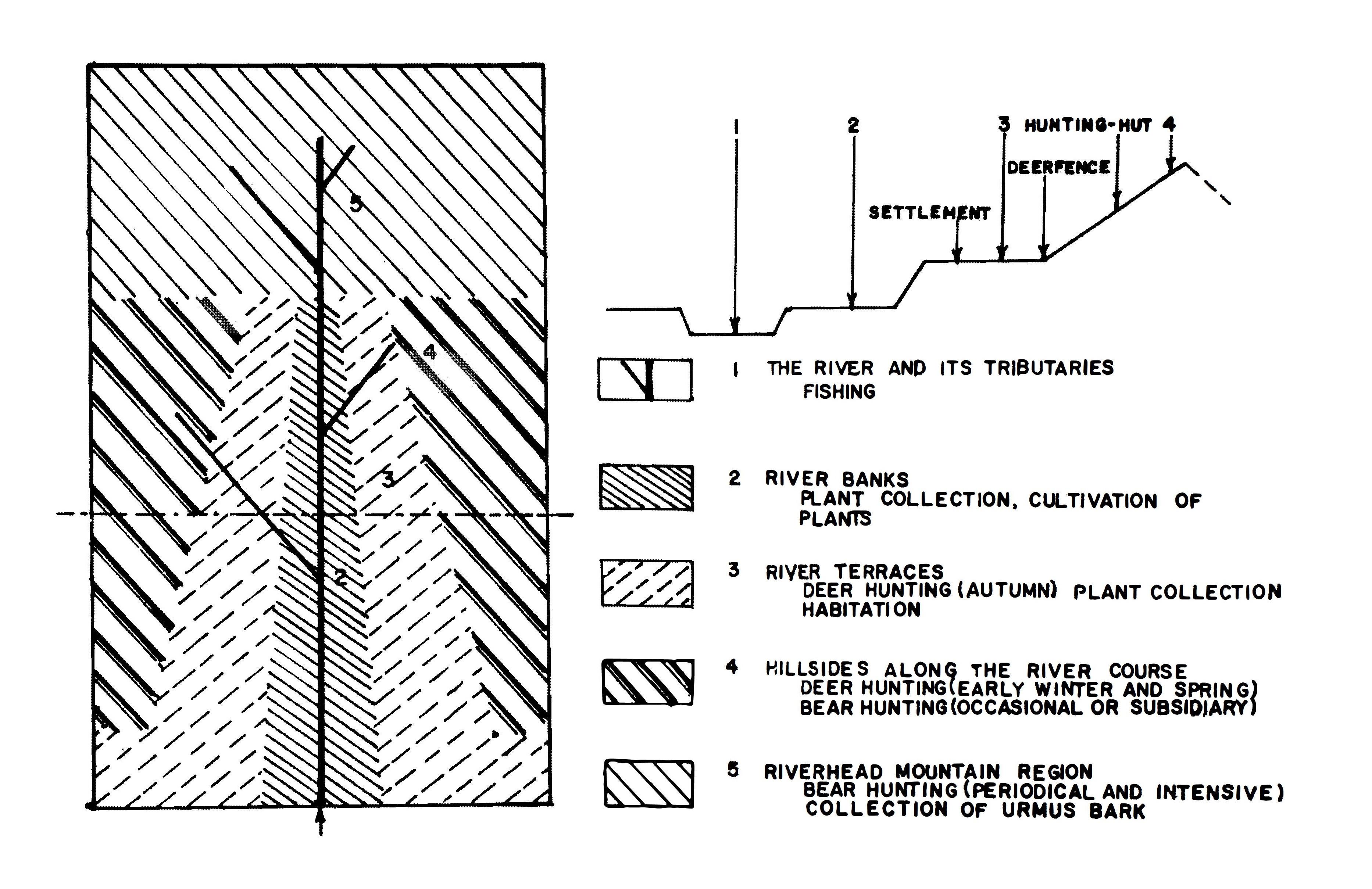

Residential Shifts and the Food-quest

Residential Stabili(y, Ecological Zones, and Habitat

Variability of the Residential Stability at the Level of the Individual

Hunting as an Occupation of Males

Individualistic or Noncommunal Hunting of Larger Mammals

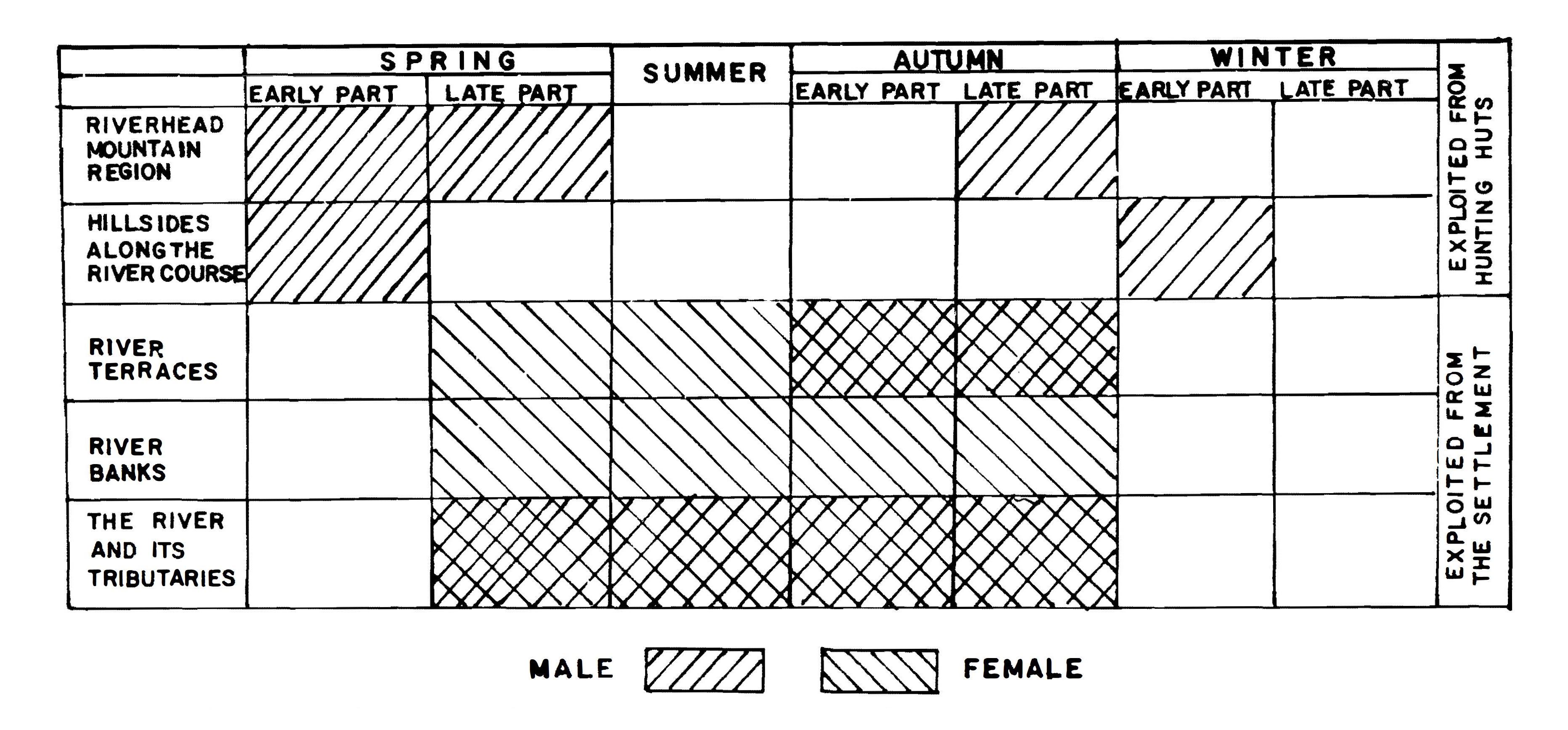

Dife rentiation of the Activiry Field according to Sex

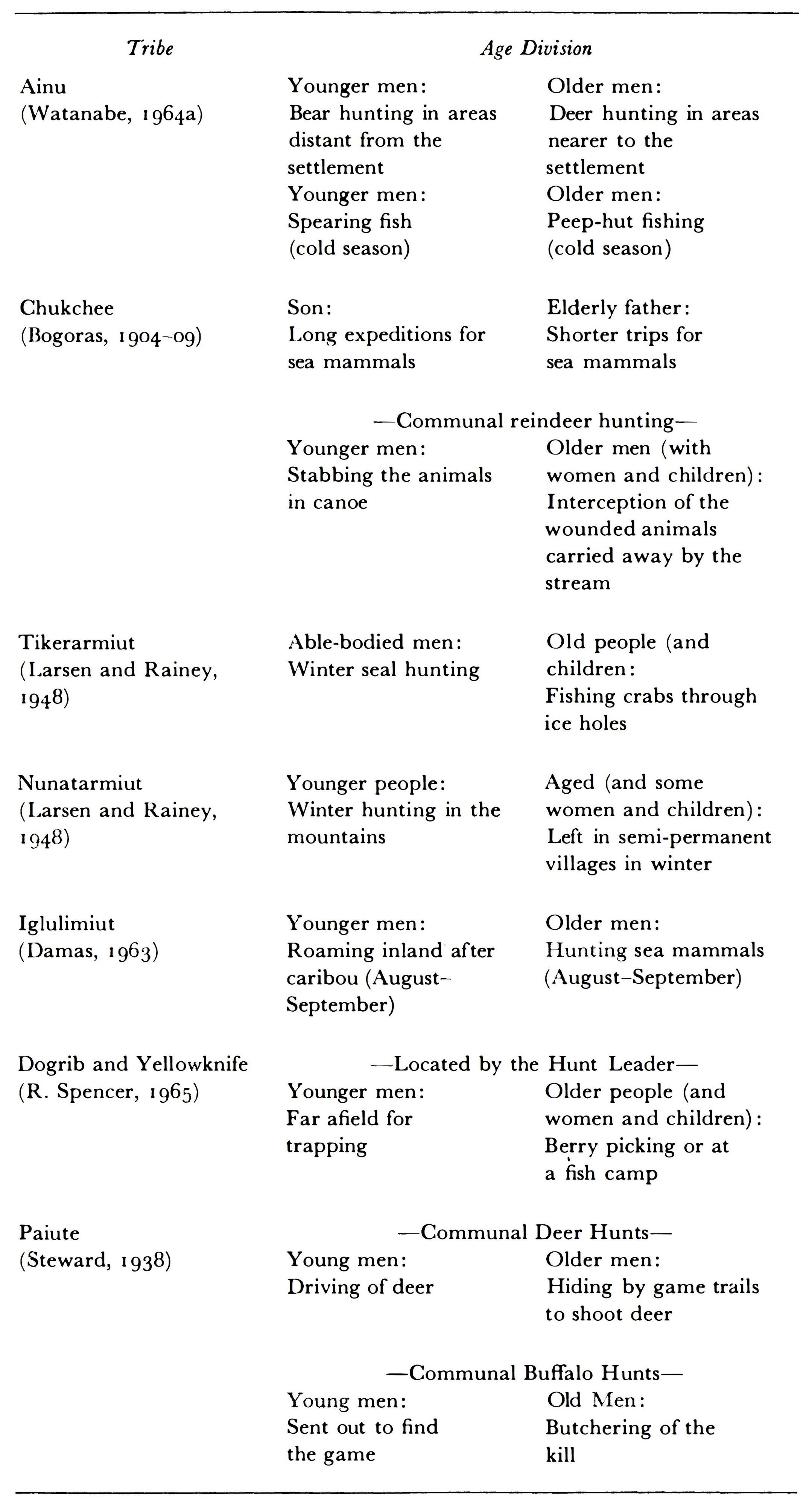

Tendency toward Age Division of Labor

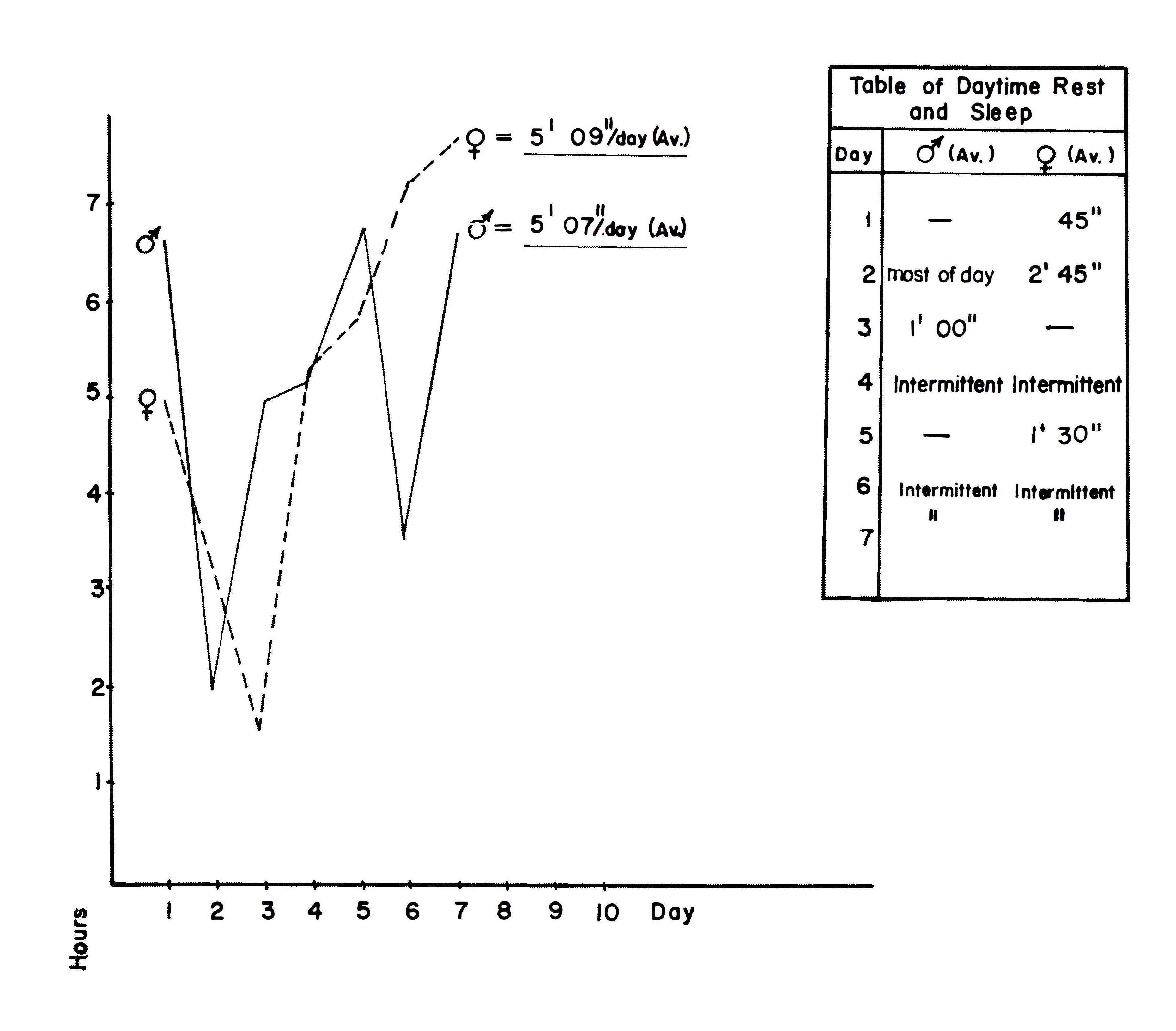

8. The Netsilik Eskimos: Adaptive Processes

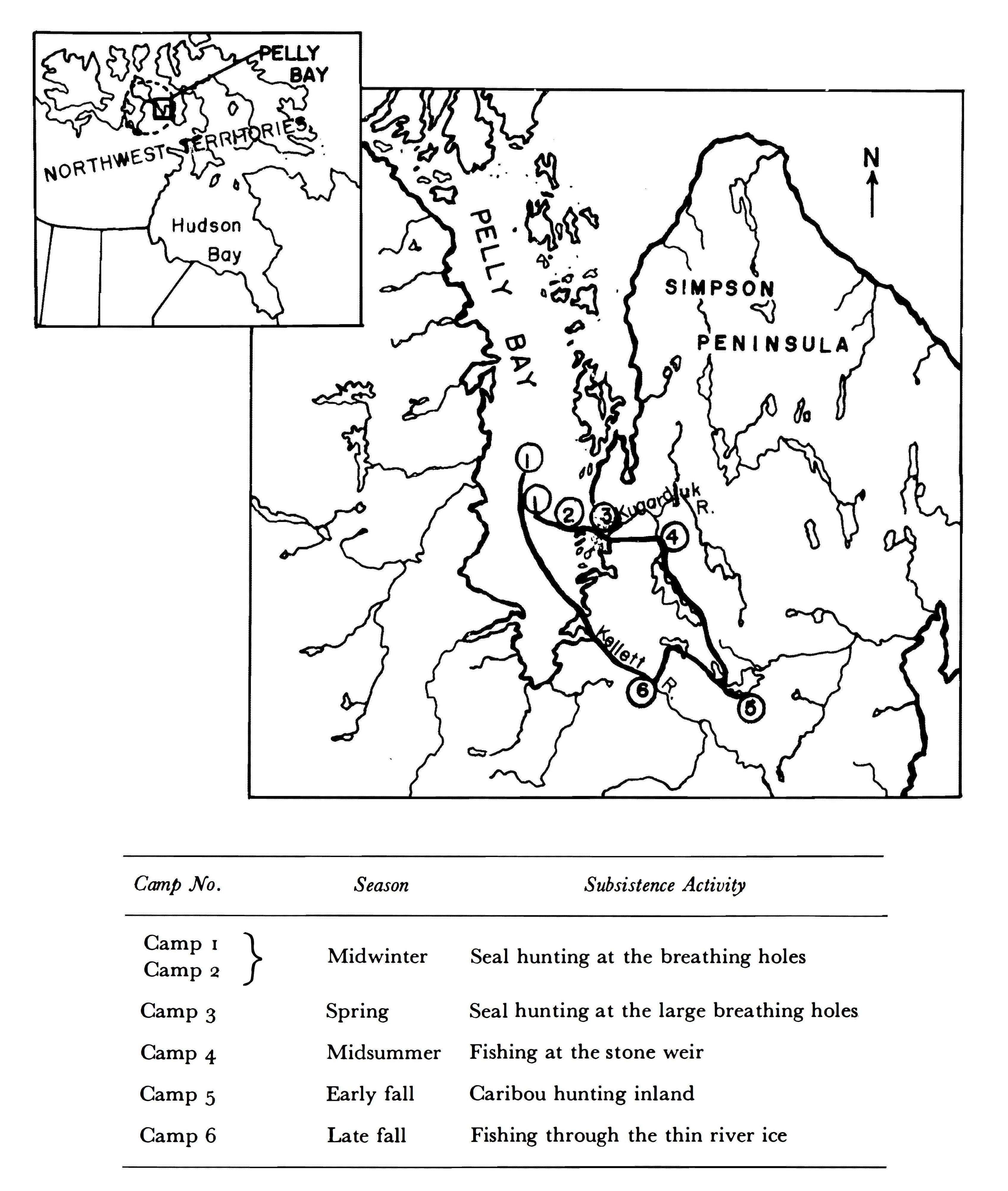

Order and Predictability in the Annual Round

Alternatives and Substitutions in Subsistence Strategy

Flexibility of Group Structure

9a. The Central Eskimo: A Marginal Case?

9b. Notes on the Original Affluent Society

9c. Does Hunting Bring Happiness?

9d. Hunting vs. Gathering as Factors in Subsistence

9e. Measuring Resources and Subsistence Strategy

Part III: Social and Territorial Organization

10. Ownership and Use of Land aIYlOng the Australian Aborigines

Ethology and Primitive Hunters

11. Stability and Flexibility in Hadza Residential Groupings

The Geographical Divisions of the Country of the Eastern Hadza

Camp Size, Composition and Nomadic Movement

Regularities in Camp Composition

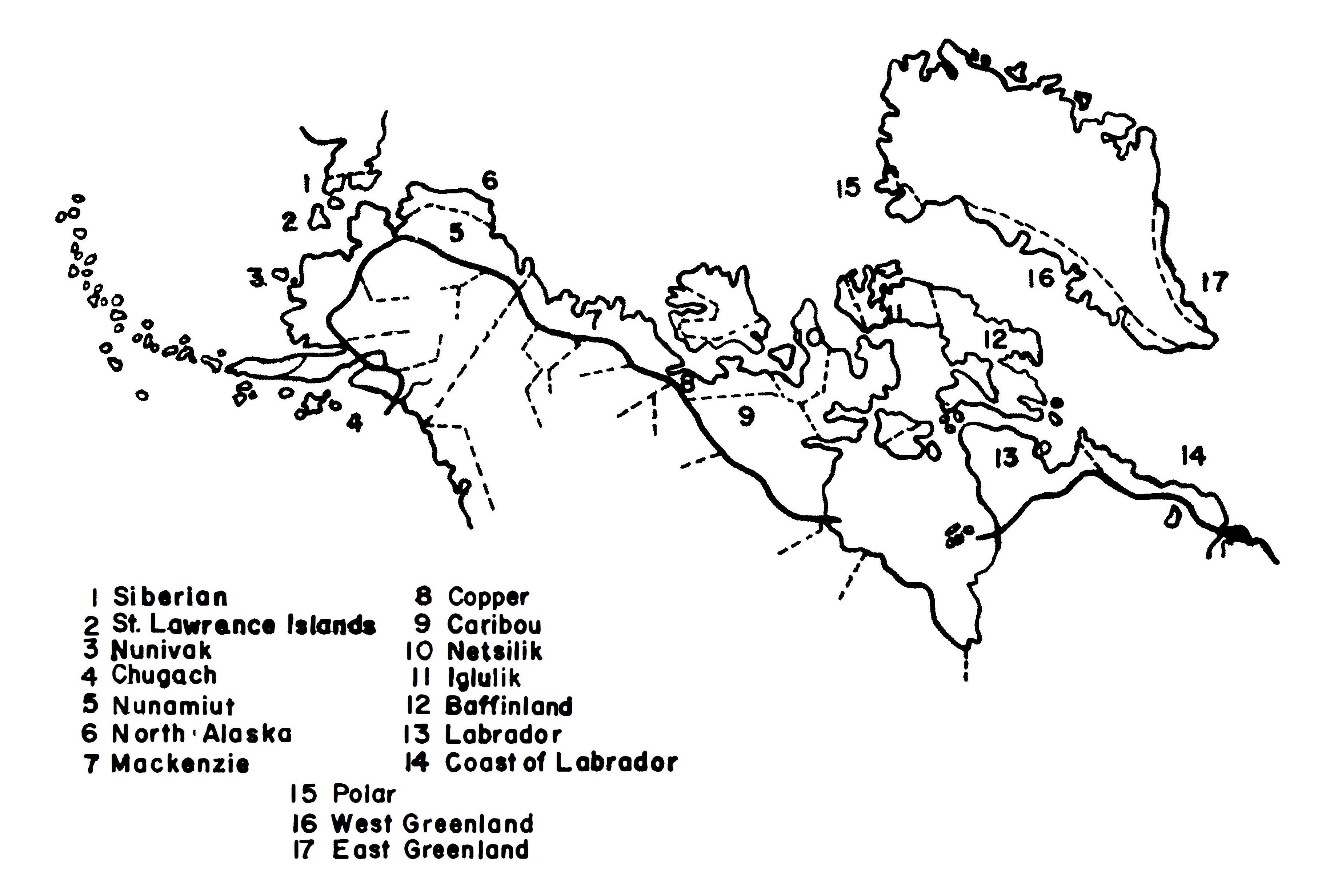

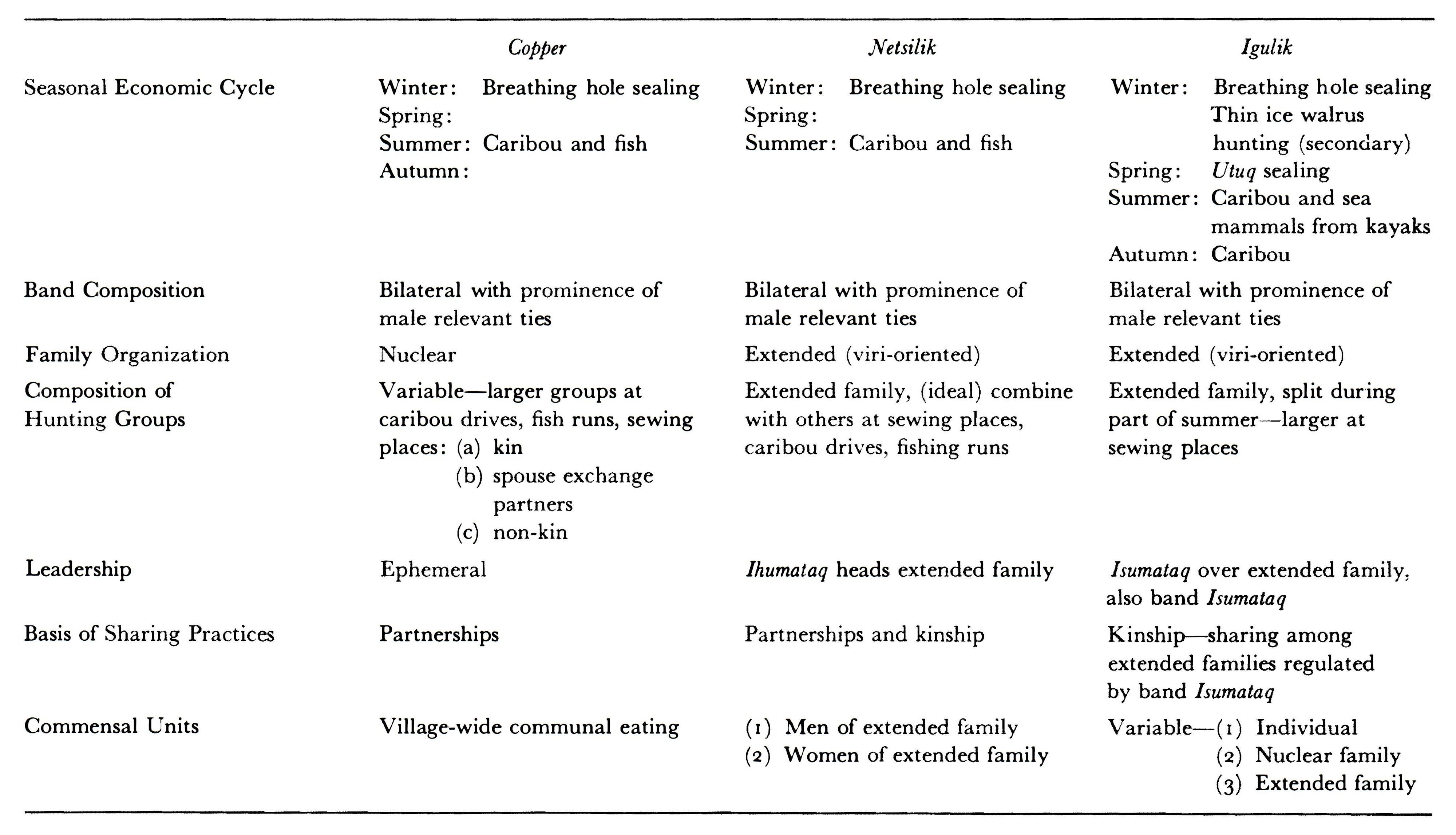

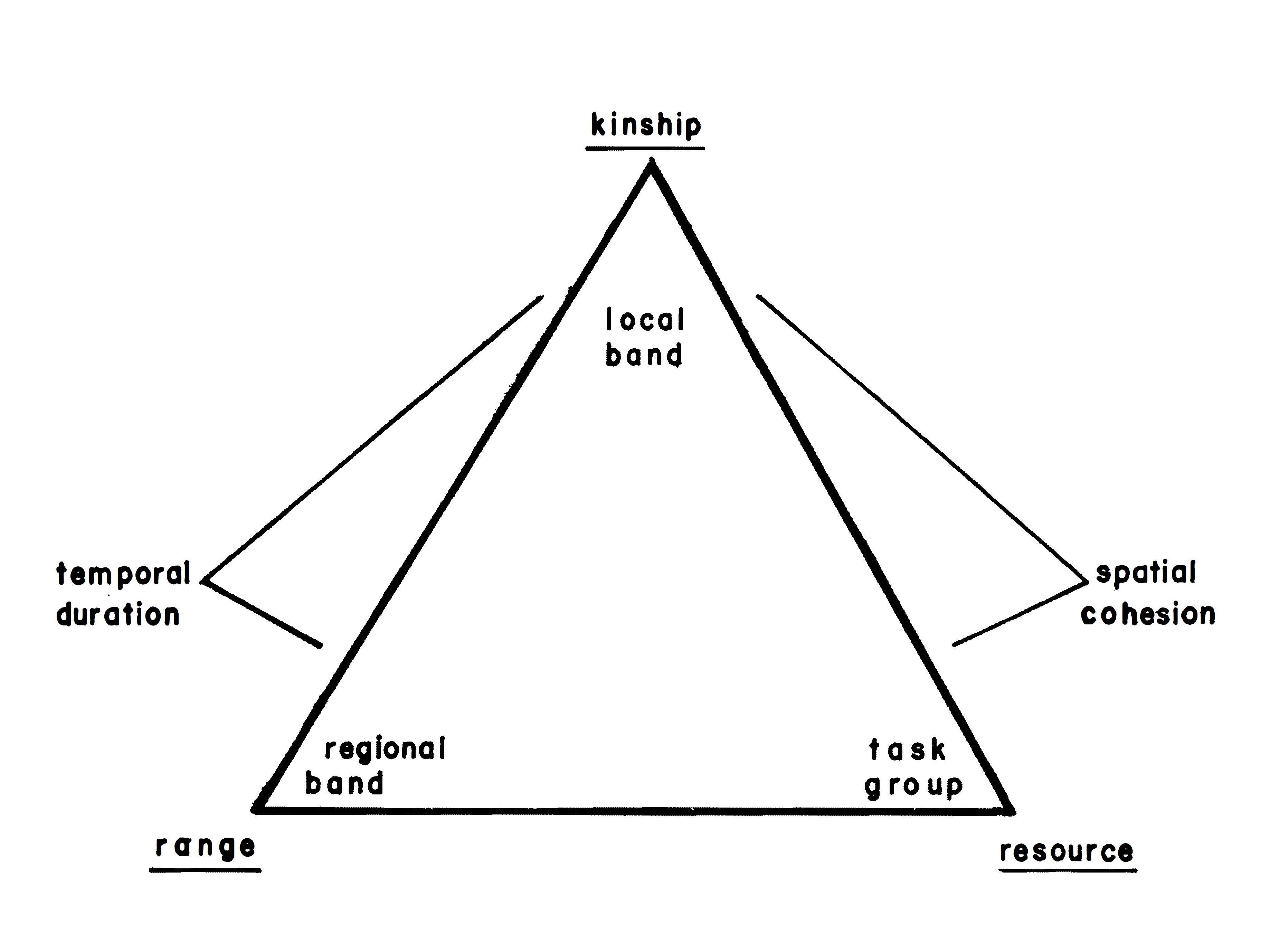

12. The Diversity of Eskimo Societies

Three Central Eskimo Societies

Relationship to Other Studies of Hunting Societies

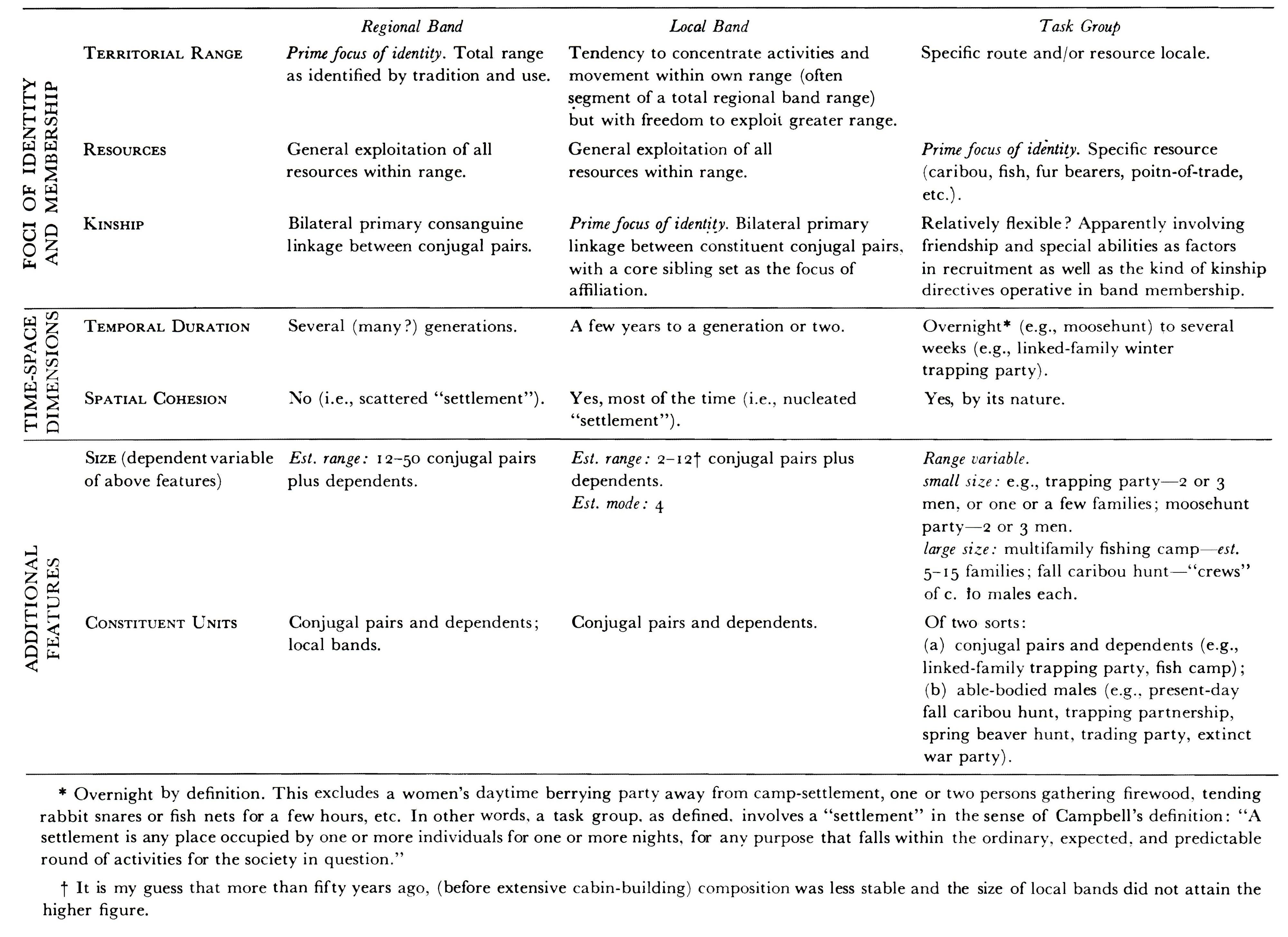

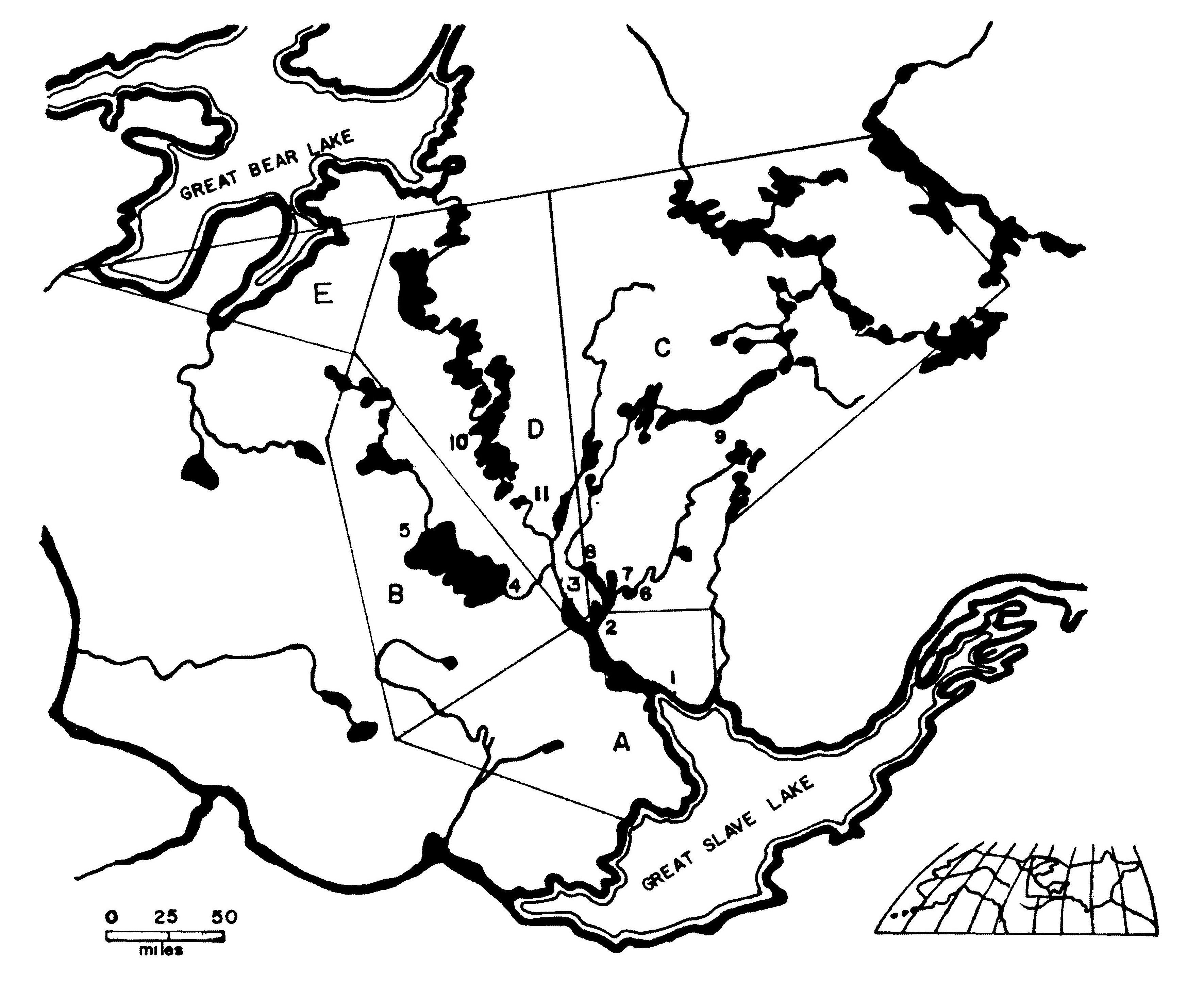

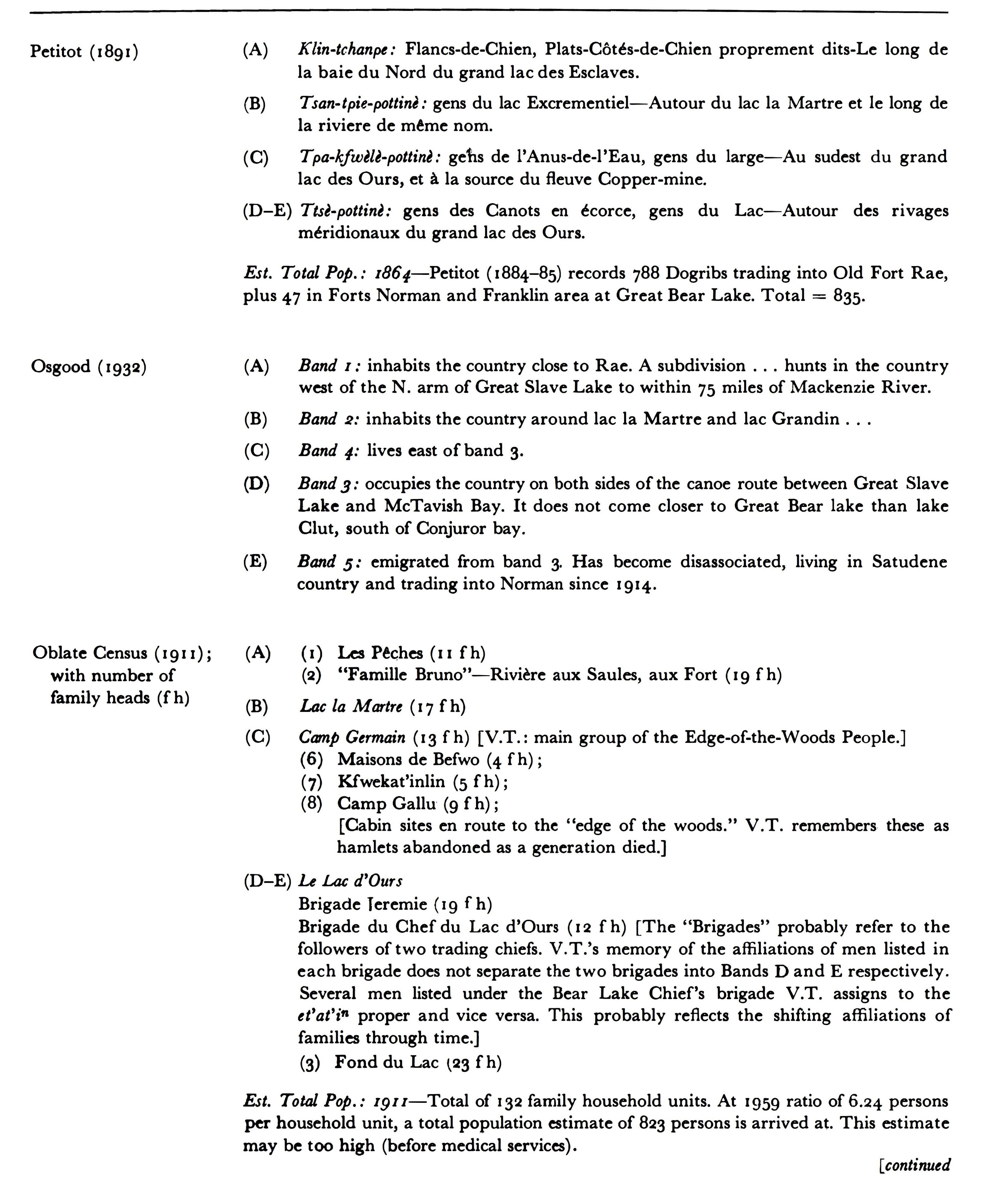

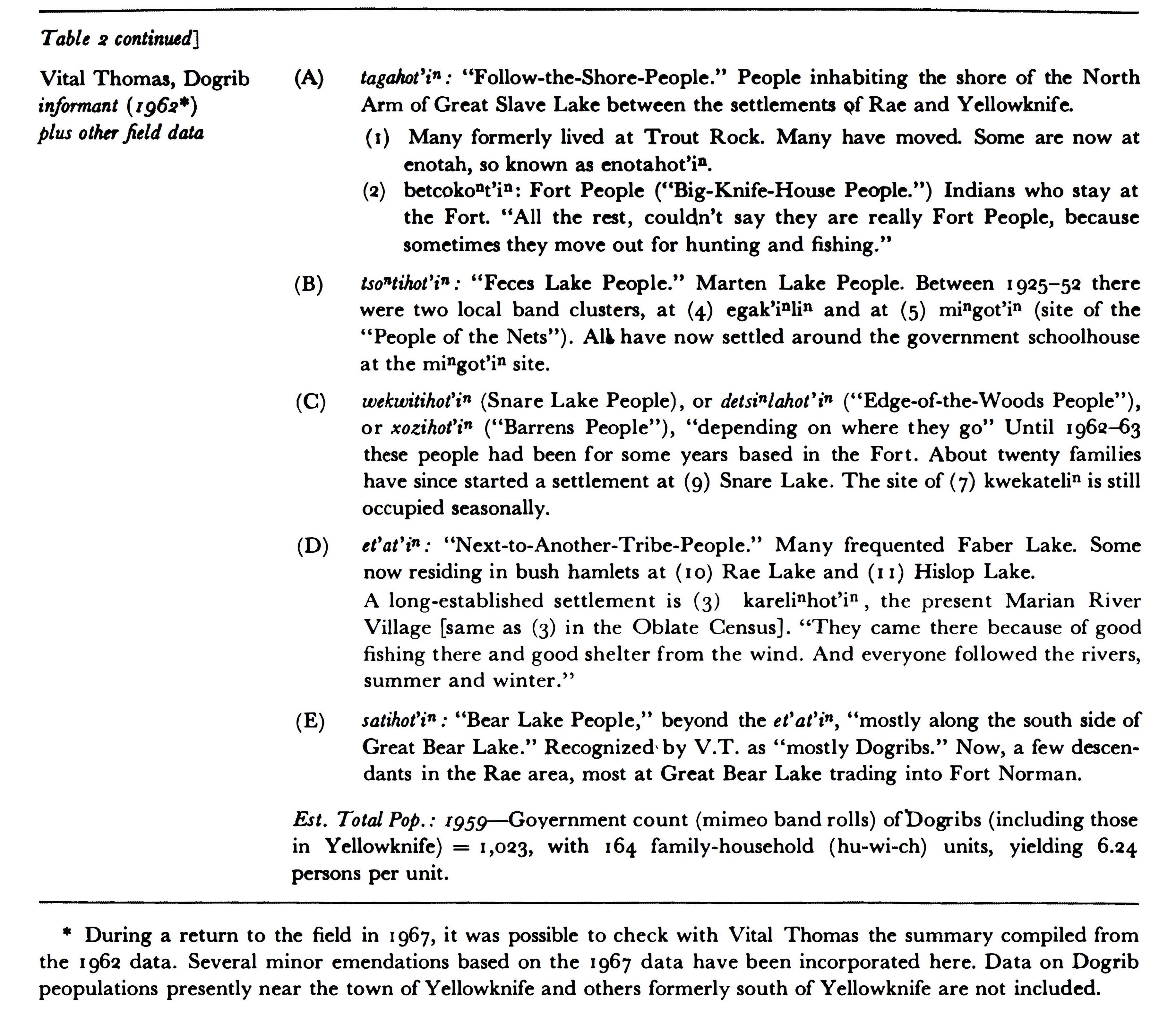

13. The Nature of Dogrib Socioterritorial Groups

Conclusions and Theoretical Considerations

14. The Birhor of India and Some Comments on Band Organization

15. The Importance of Flux in Two Hunting Societies

16. Southeastern Australia: Level of Social Organization

Complexity of Social Organization

17a. On Ethnographic Reconstruction

17b. The Problem of Lineage Organiza1 Ion

17c. Analysis of Group Composition

17d. Social Determinants of Group Size

17e. Resolving Conflicts by Fission

17h. Hunter Social Organization: Some Problems of Method

The Importance of Longer Field Studies

The Application of Role Theory

17i. Typology and Reconstruction: A Shoshoni Example

Part IV: Marriage and Models in Australia

18. Gidjingali Marriage Arrangements

Section 1: Kinship groups and terminology

Models, Facts, and Feeling Cheated

Conclusion: Communication or Competition?

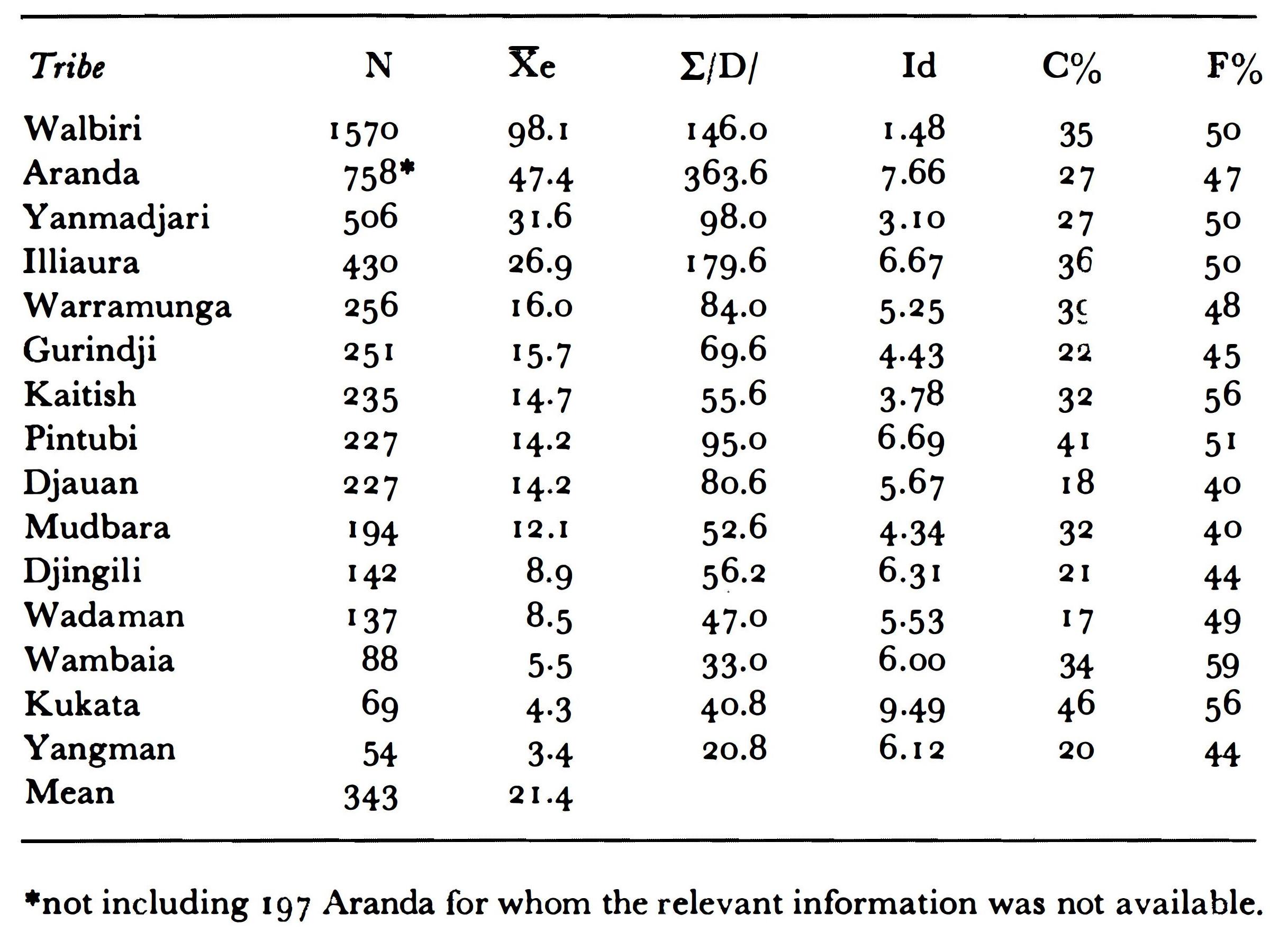

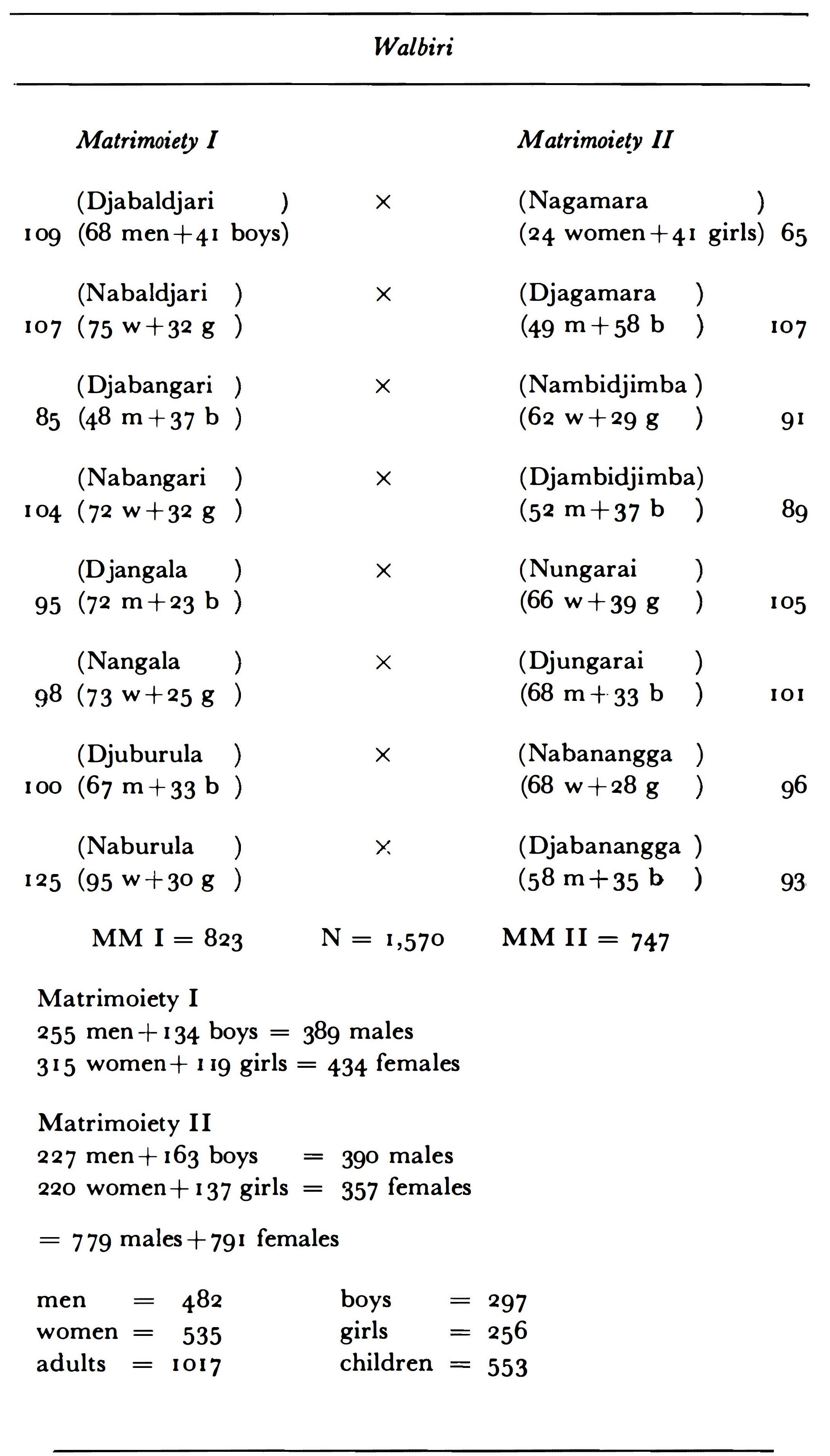

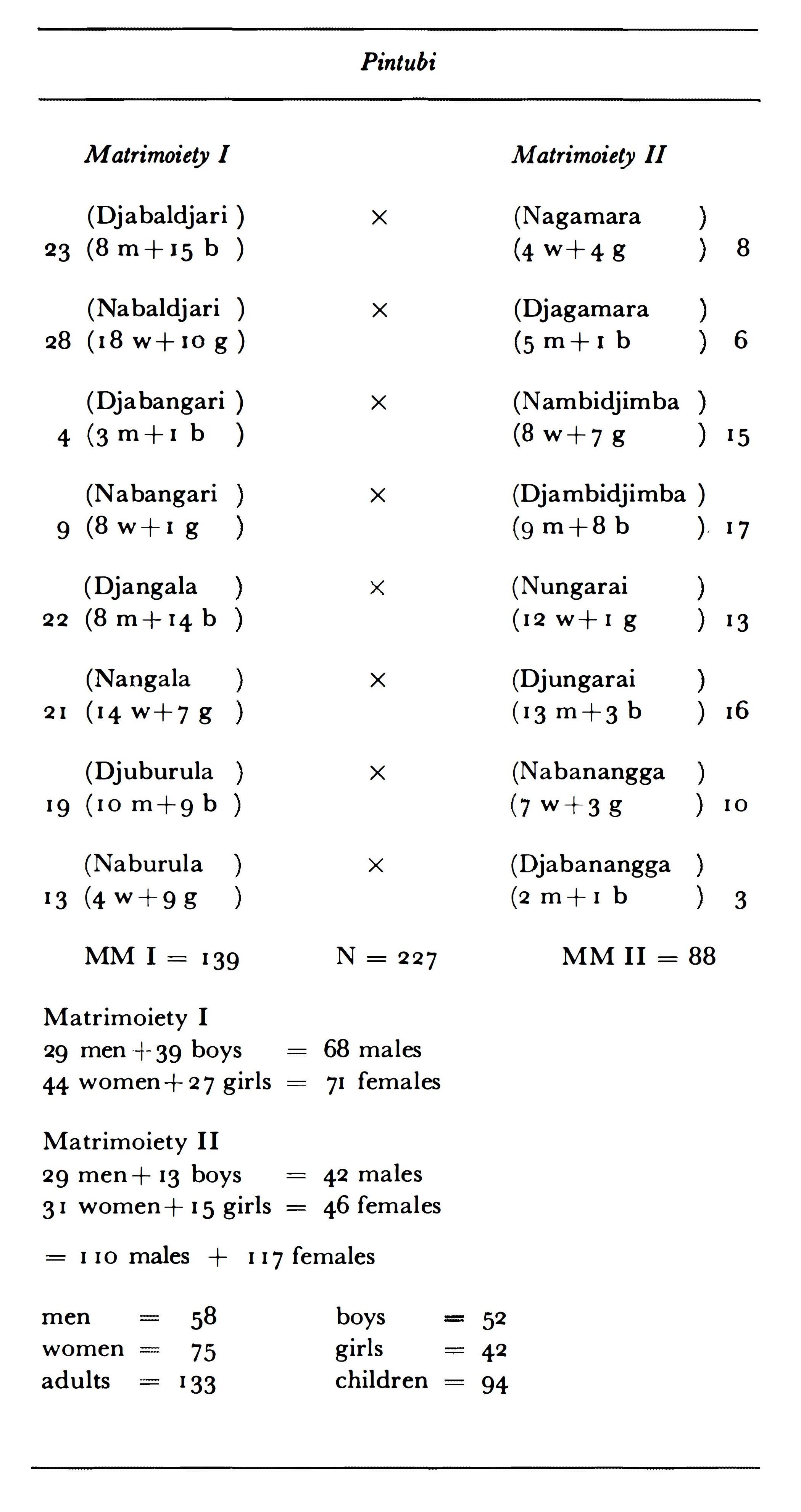

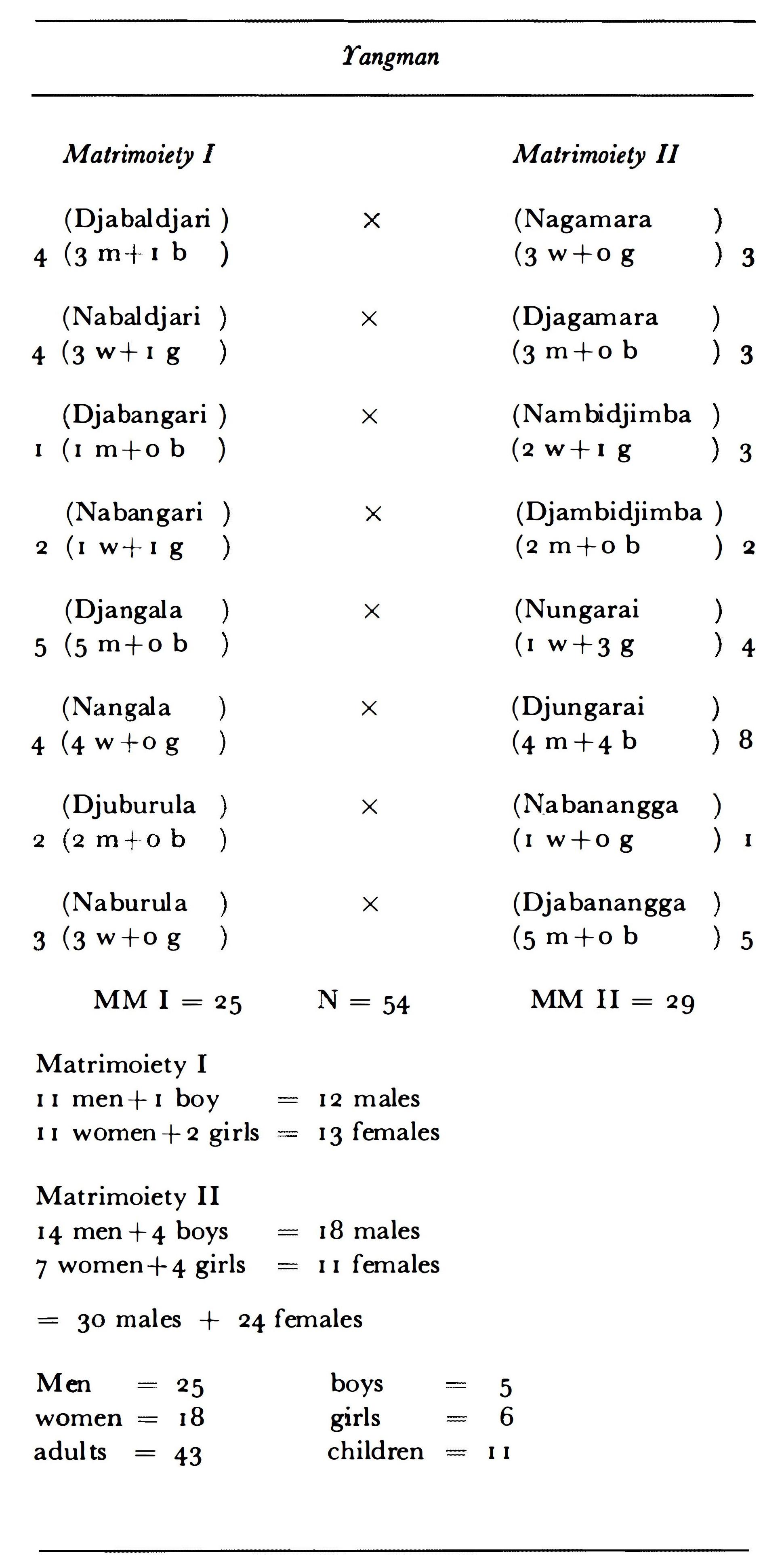

19. “Marriage Classes” and Demography in Central Australia

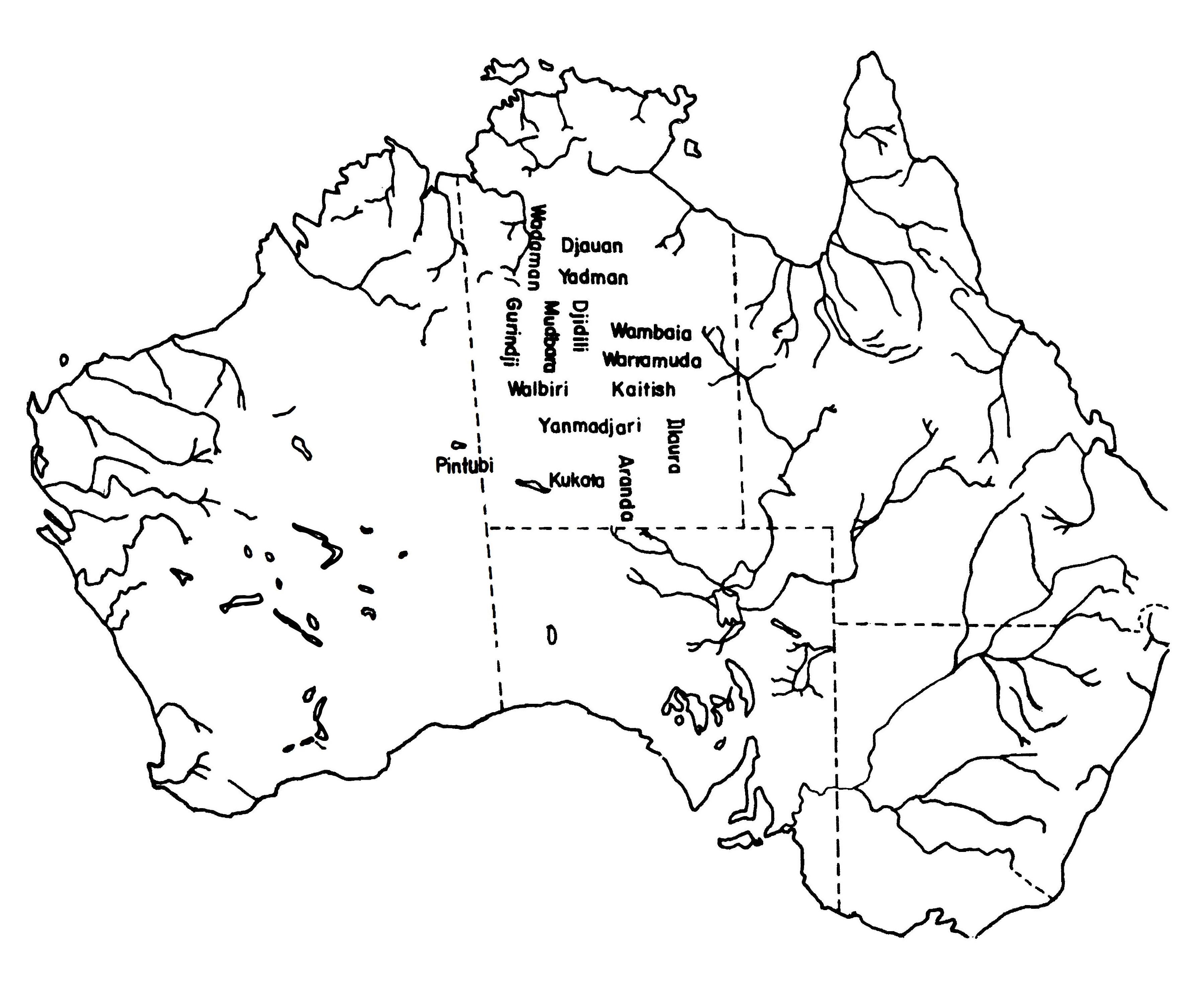

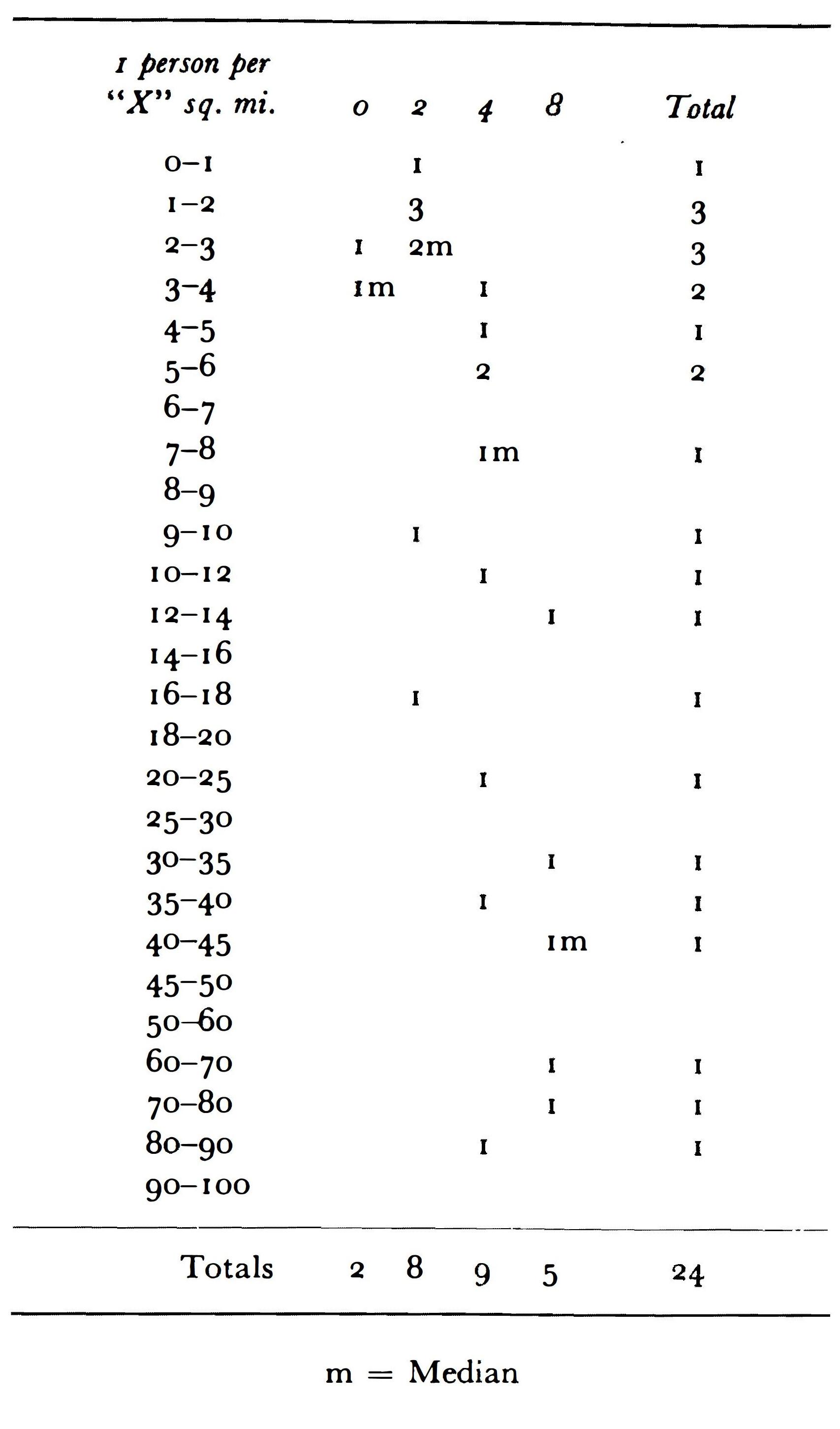

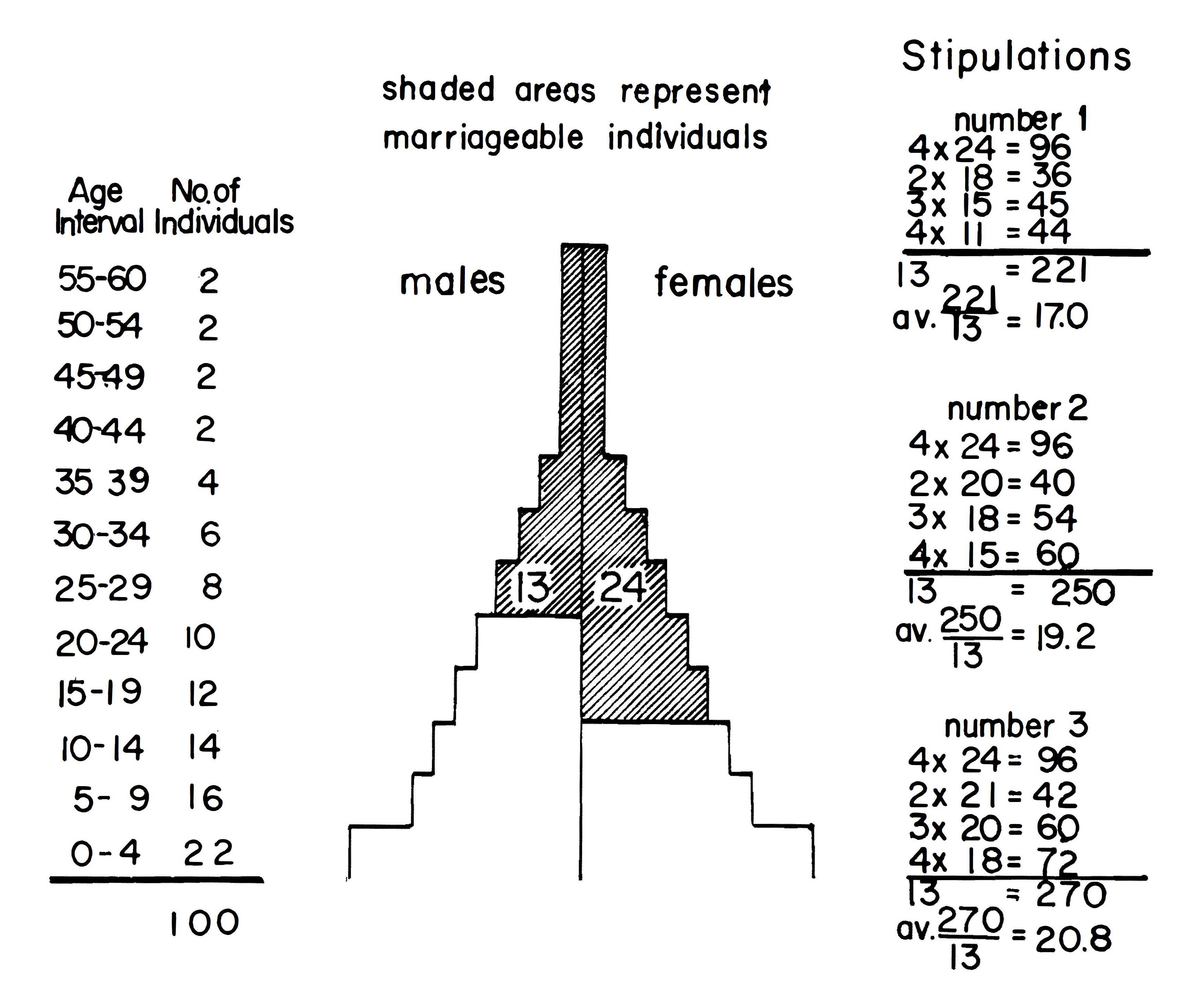

20. Demographic and Ecological Influences on Aboriginal Australian Marriage Sections

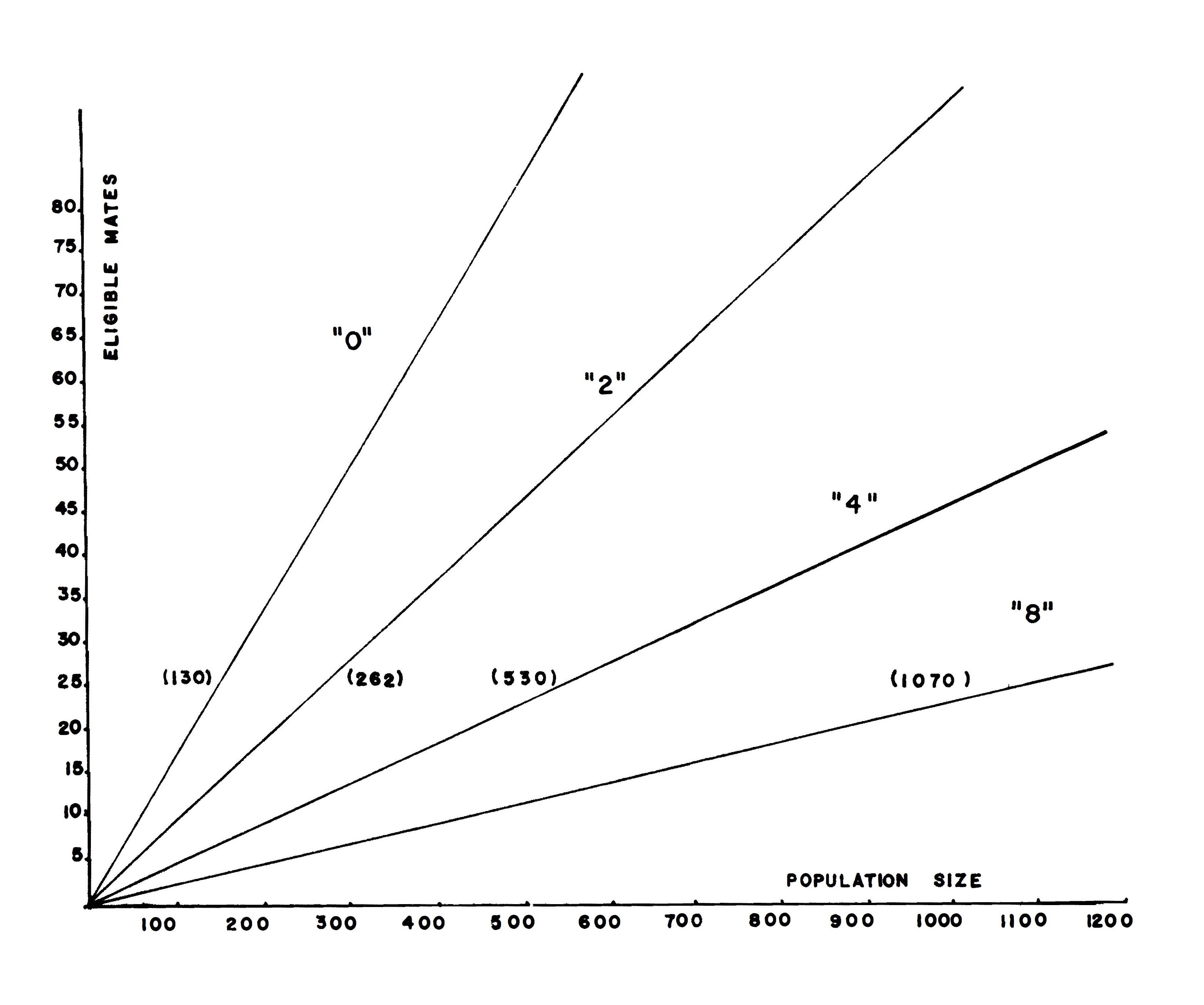

Section Systems and the Population Parameter

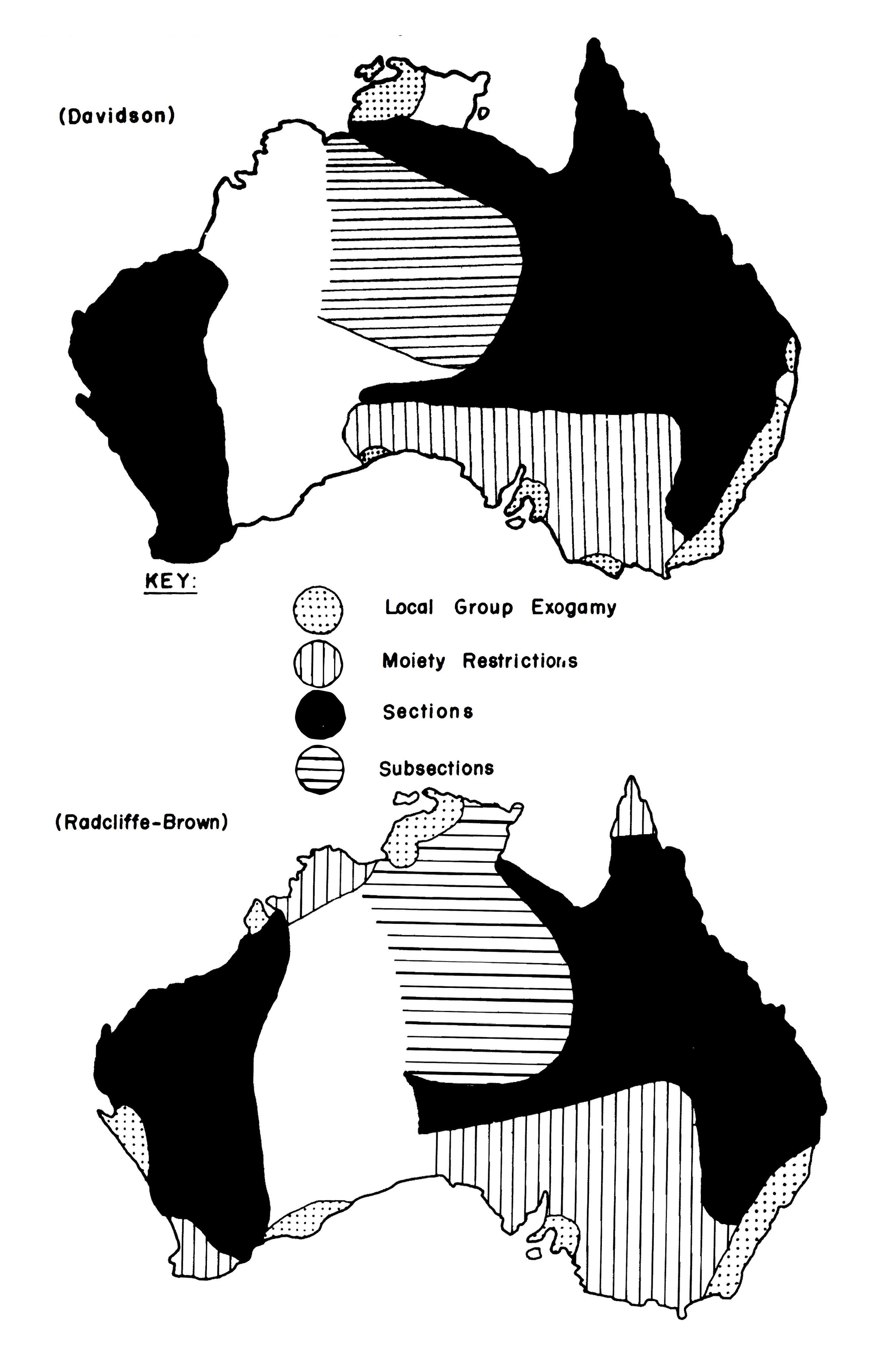

Australia. Upper: After Davidson; Lower: After Radcliffe-Brown.

21. Australian Marriage, Land-Owning Groups, and Initiations

Marriage and the Land-Owning Group

Sahlins’ Original Aifiuent Society,’ A Comment

Marriage Gerontocracy in Australia

Interpretation of Marriage Gerontocracy

22a. Gerontocracy and Polygyny

22b. Gidjingali Marriage Arrangements: Comments and Rejoinder

22c. The Use and Misuse of Models

22d. Statistics of Kin Marriage: A Non-Australian Example

Part V: Demography and Population Ecology

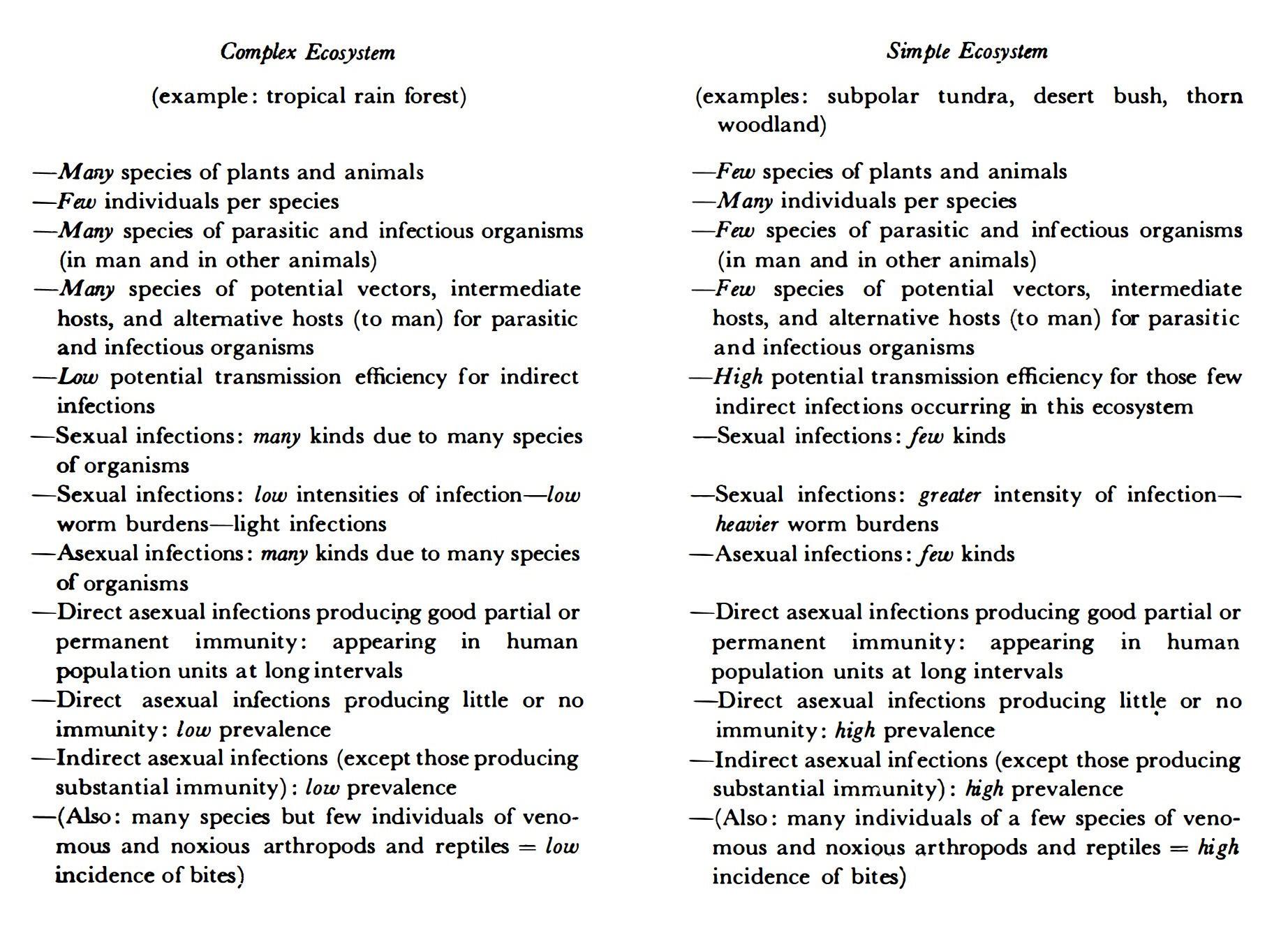

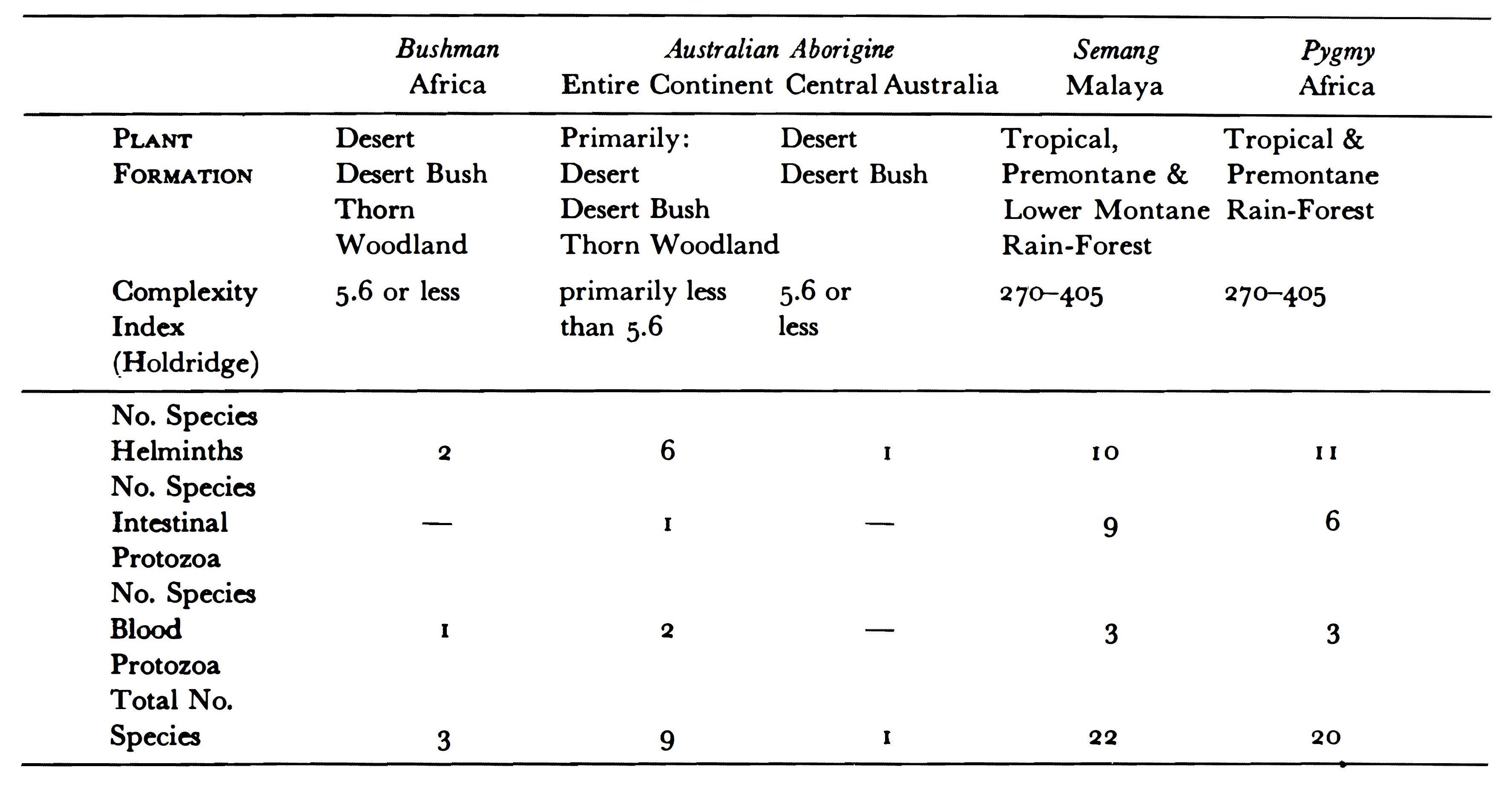

23. Epidemiological Factors: Health and Disease in Hunter-Gatherers

Disease in the Population Equation

Mortality and Disease in Hunter-Gatherers

24. Some Predictions for the Pleistocene Based on Equilibrium Systems among Recent Hunter-Gatherers

The Density Equilibrium System

Predictions for the Pleistocene

Communication Eq.uilibrium System

Predictions for the Pleistocene

Local Group Eqiltillbriltm Systems

Predictions for Pleistocene Hunters

Required Research Jor the Future

Predictions for Pleistocene Populations

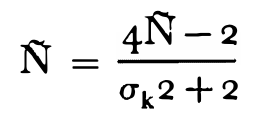

Equilibrium in the Size of the Effective Breeding Population

Predictions for Pleistocene Populations

25a. The Demography of Hunters: An Eskimo Example

25b. Population Control Factors: Infanticide, Disease, Nutrition, and Food Supply

25c. The Magic Numbers “25” and “500”: Determinants of Group Size in Modern and Pleistocene Hunters

25d. Pleistocene Family Planning

Part VI: Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers

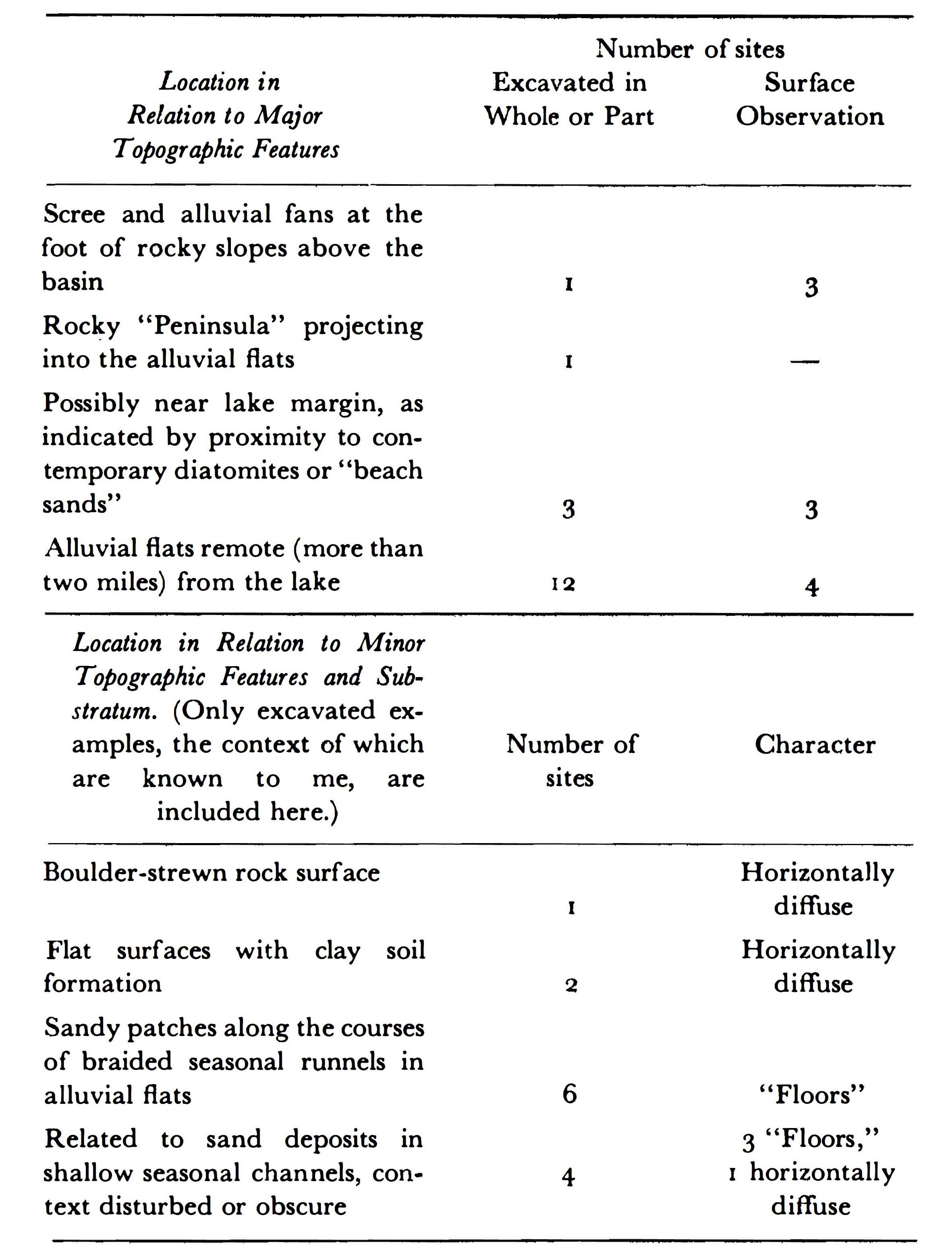

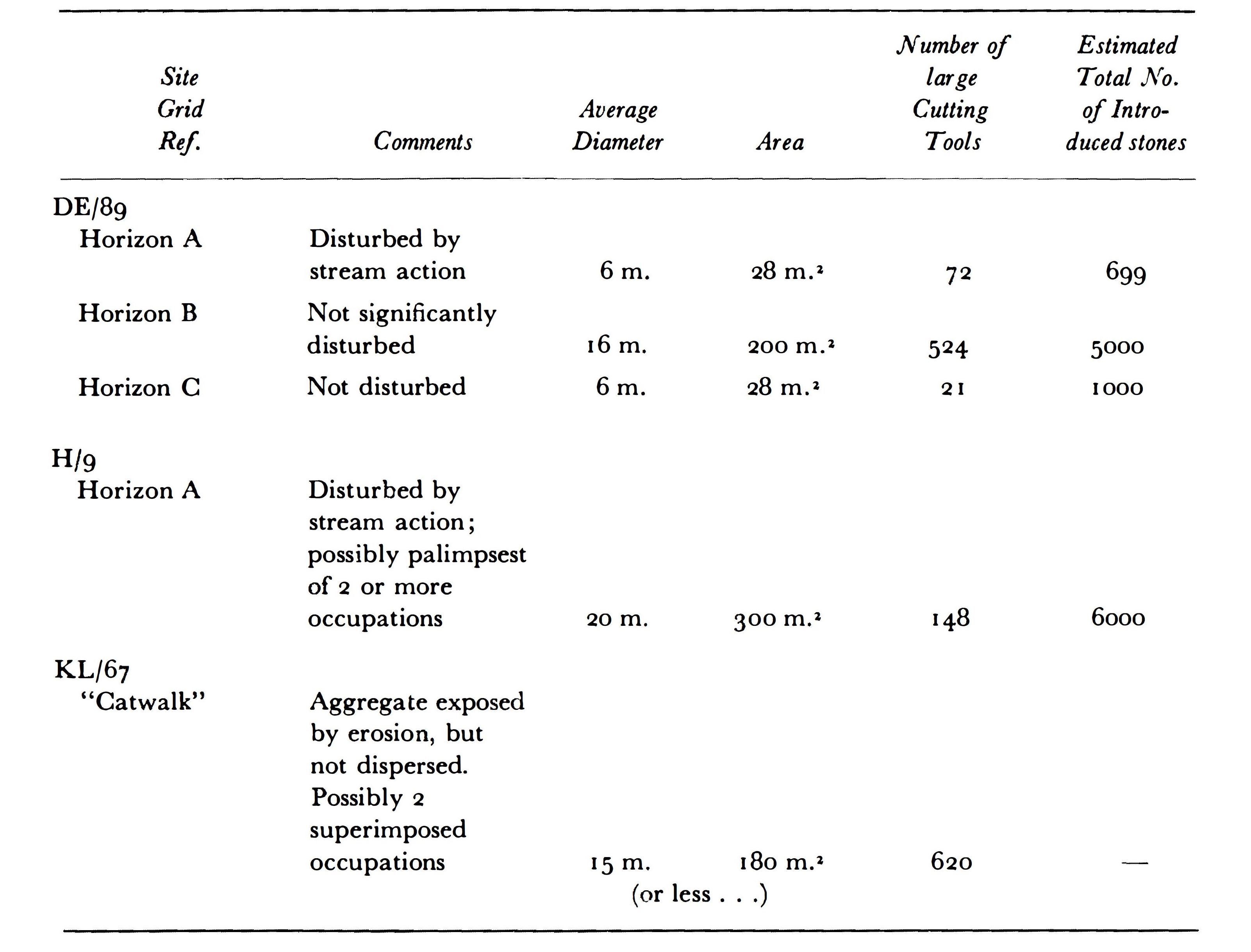

26. Traces of Pleistocene Hunters; An East African Example

The Occurrence of Archeological Evidence

Location and Character of Occupation Sites

27. A Theoretical Framework for Interpreting Archeological Materials

A General Illustration of the Use of the model

28. Methodological Considerations of the Archeological Use of Ethnographic Data

29. Ethnographic Data and Understanding the Pleistocene

30. Studies of Hunter-Gatherers as an Aid to the Interpretation of Prehistoric Societies

Prehistoric Settlement Sites and Survival Patterns

31a. Hunters in Archeological Perspective

31b. Archeological Visibility of Food-Gatherers

31c. The Use of Ethnography in Reconstructing the Past

Part VII: Hunting and Human Evolution

The Social Organization of Human Hunting

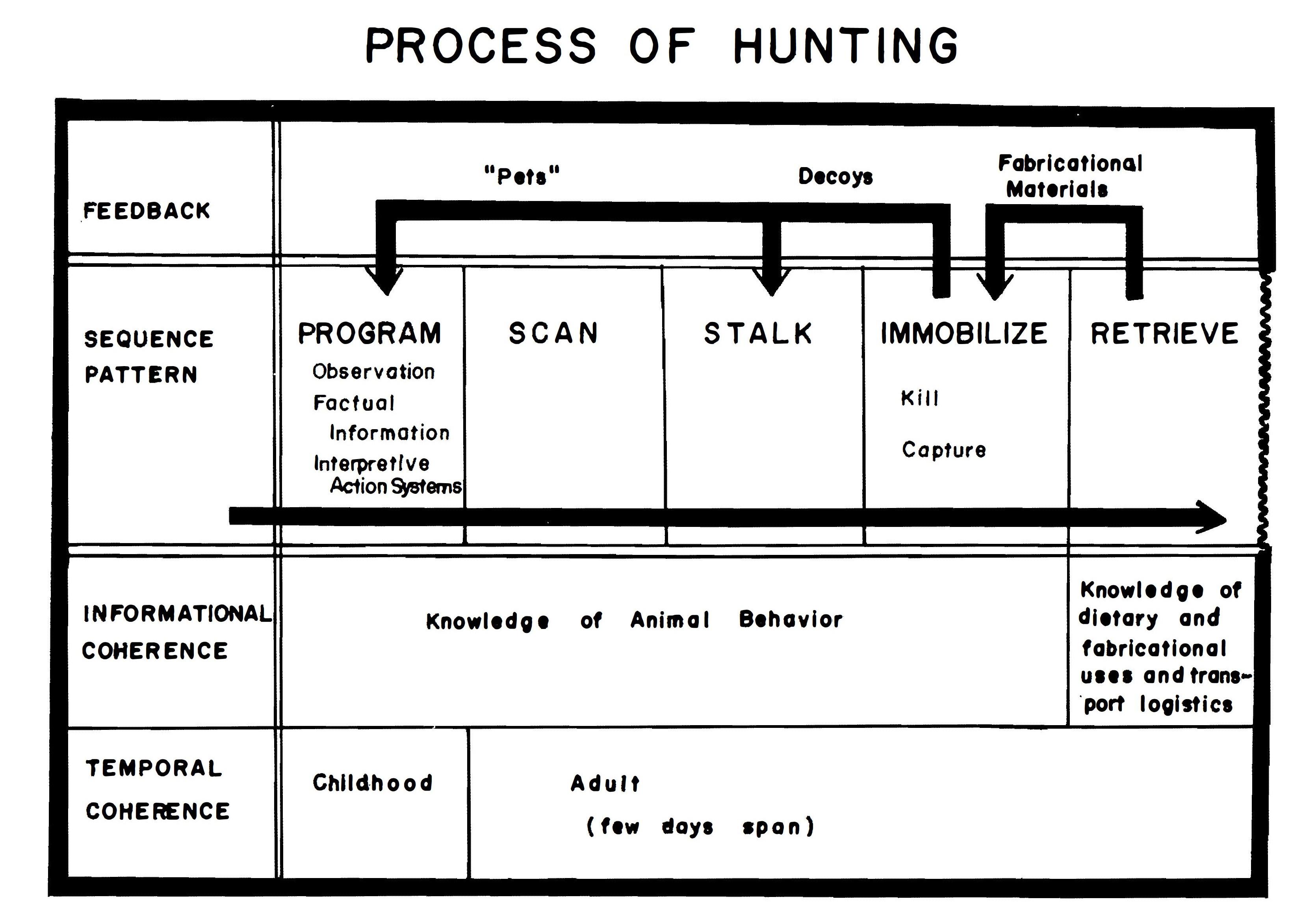

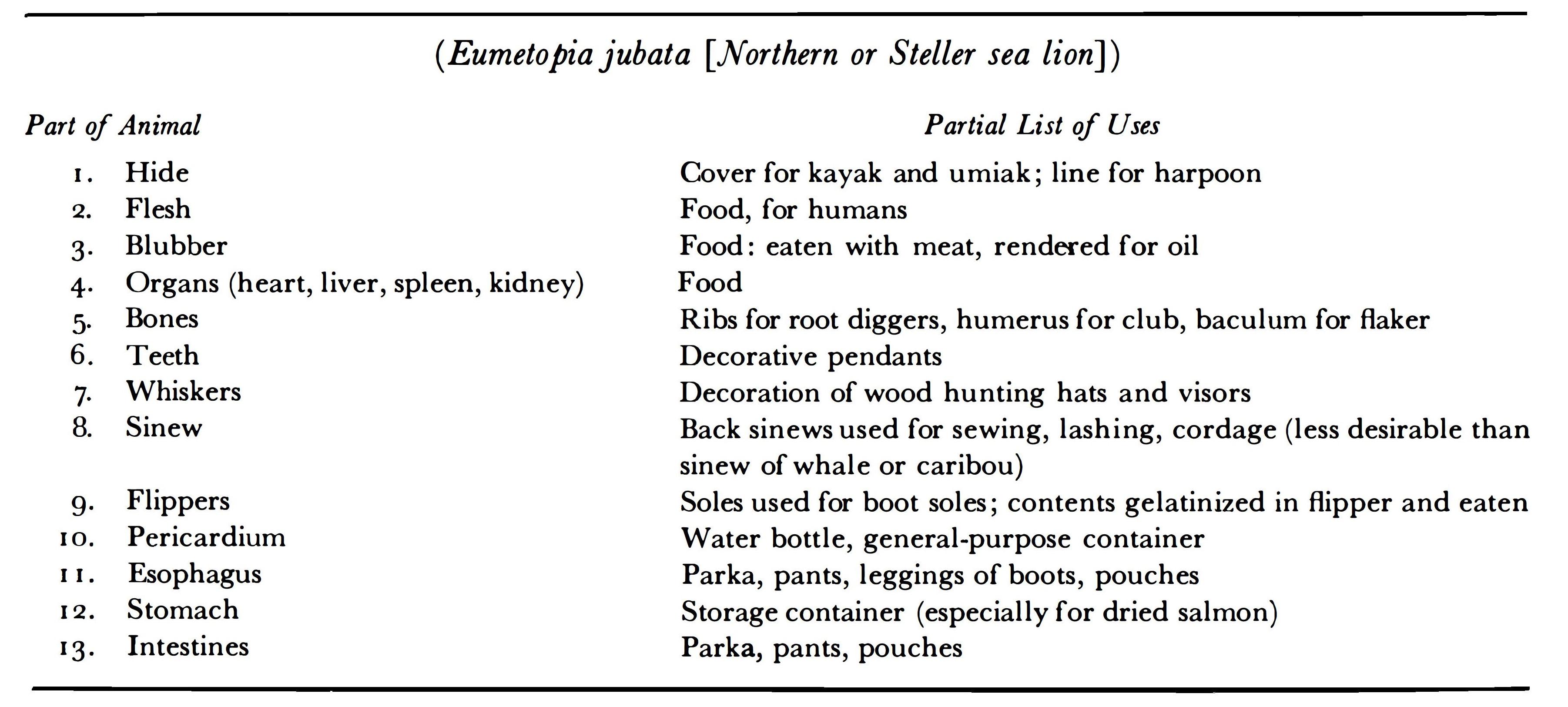

33. Hunting: An Integrating Biobehavior System and Its Evolutionary Importance

Immobilization, Killing, and Capture

The Physical Superiorities of Man

Simplicity of Basic Technology

Hunter’s Sophisticated Knowledge of Behavior and Anatomy

Genetic Mechanisms in Hunting Societies

34. Causal Factors and Processes in the Evolution of Pre-farming Societies

Evolutionary Factors and Processes

35a. Are the Hunter-Gatherers a Cultural Type?

35b. Primate Behavior and the Evolution of Aggression

Part VIII: The Concept of Primitiveness

36. The Concept of Primitiveness

Archivists Appendix: Digitizations of Tables

Part II: Ecology and Economics

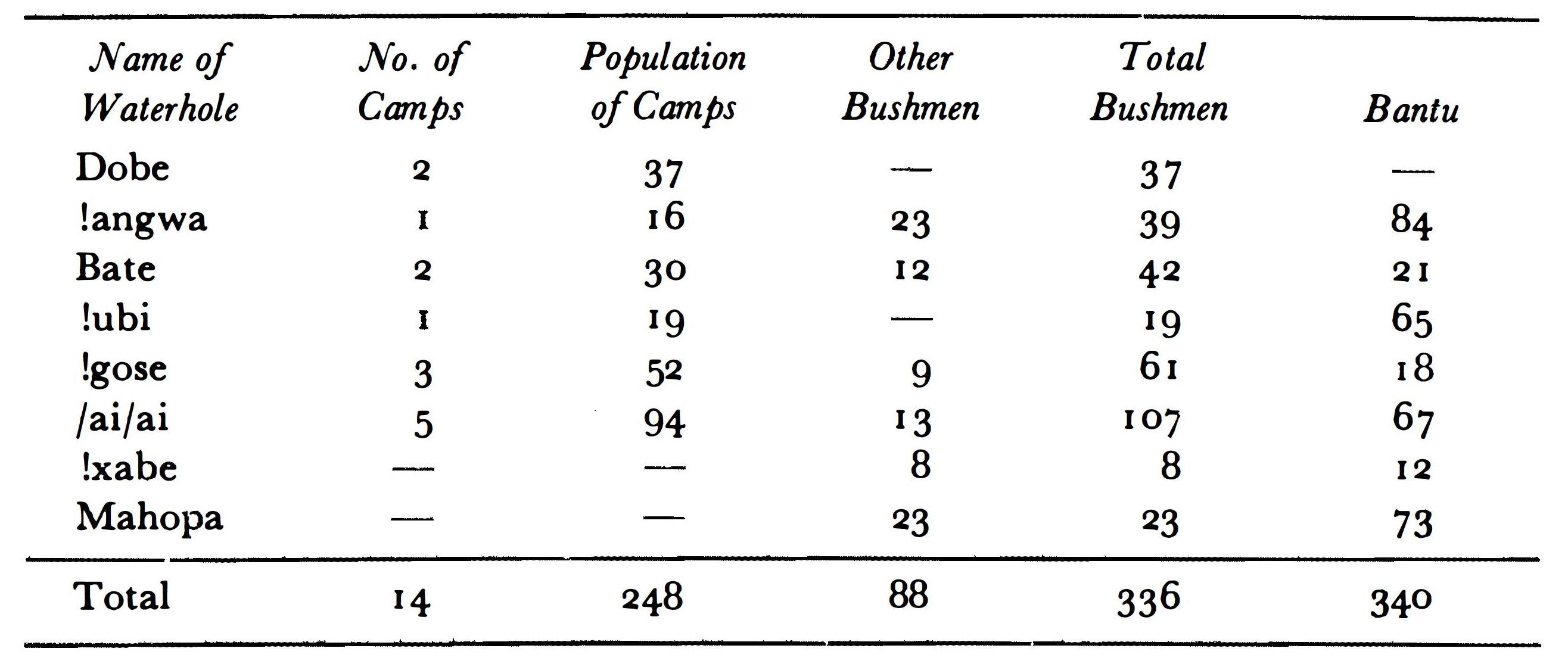

Table 1. Numbers and Distribution of Resident Bushmen and Bantu by Waterhole

[Front Matter]

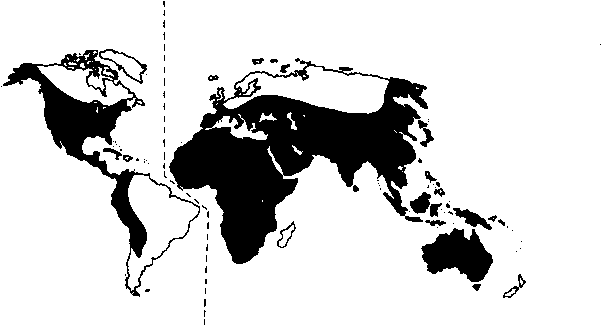

Hunters of the World

World Population: 10 million

Per Cent Hunters: 100

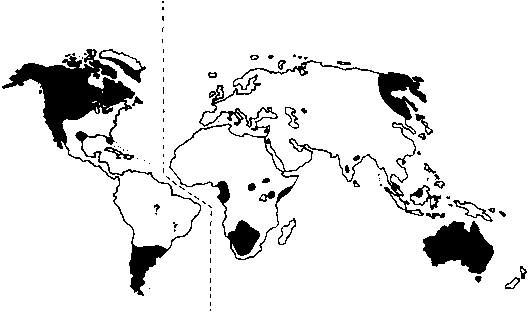

World Population: 350 million

Per Cent Hunters: 1.0

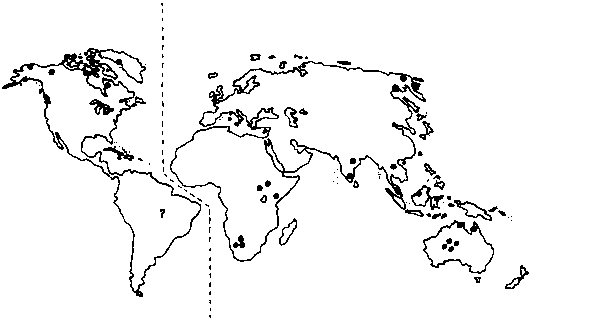

World Population: 3 billion

Per Cent Hunters: 0.001

[Title Page]

MAN THE HUNTER

Edited by

Richard B. Lee

and

Irven DeVore

with the assistance of

Jill Nash-Mitchell

ALDINE DE GRUYTER / New York

[Copyright]

Copyright © 1968 by the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research, Inc.

All rights reserved. No part of this publication may he reproduced or transmitted in any form or by any means, electronic or mechanical, including photocopy, recording, or ally information storage and retrieval system, without permission in writing from the publisher.

ALDINE DE GRUYTER

A Division of Walter de Gruyter, Inc.

200 Saw Mill River Road

Hawthorne, N.Y. 10532

Eleventh printing, 1987

ISBN 0-202-33032-X

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number 67–17603

Designed by Chestnut House

Printed in the United States of America

[Dedication]

To Claude Levi-Strauss

Preface

In November, 1965, Sol Tax asked us to organize a symposium on current research among the hunting and gathering peoples of the world. This meeting was conceived to follow logically from an earlier symposium on the Origin of Man held at the University of Chicago in April, 1965. There were a number of reasons why we felt a conference devoted exclusively to the hunting way of life would be appropriate at this time. Current ethnographic studies have contributed substantial amounts of new data on hunter-gatherers and are rapidly changing our concept of Man the Hunter. Social anthropologists generally have been reappraising the basic concepts of descent, filiation, residence, and group structure. In archeology the recent excavation of early living floors has led to a renewed interest in and reliance on hunter-gatherer data for reconstruction, and current theories of society and social evolution must inevitably take into account these new data on the hunter-gatherer groups. Finally, hunting and gathering, as a way of life, is rapidly disappearing and it was hoped that the symposium would serve to stimulate further research while there were still viable groups to study.

It was clear, however, that the first order of business was to present the new data on hunters and to clarify a series of conceptual issues among social anthropologists as a necessary background to broader discussions with archeologists, biologists, and students of human evolution. A preliminary canvass was made in January, 1966, of seventeen younger anthropologists who had recently completed field work among hunting peoples, and their enthusiastic response led us to contact an additional fifty scientists in social anthropology, human biology, archeology, demography, and ecology, particularly those who in their writings had shown an interest in hunter-gatherer data and theory. The positive response of this larger group insured the success of the symposium, and the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research generously agreed to sponsor the meeting and to cover traveling and living expenses for the participants.

The symposium on Man the Hunter was held at the Center for Continuing Education at the University of Chicago, April 6–9, 1966. In attendance were some 75 scholars from as far afield as India, Japan, Australia, Uganda, Kenya, and the German Democratic Republic, as well as from centers in France, England, Canada, Latin America, and the United States. In an intensive four-day meeting, those present heard 28 background papers and twelve formal discussions, and participated in over ten hours of open debate. Since most of the papers had been distributed in advance, it was possible to limit formal presentations to ten minutes each in order to leave time for discussion. Our impression is that most participants found this intensive format exhausting but rewarding.

With three exceptions, all of the original papers presented at the symposium are published here. The majority have been substantially revised in the light of our discussions in Chicago. In addition, two new papers, one by Yengoyan and the other by Washburn and Lancaster, are included in the book although they were not presented at the meeting.

The format of this book follows closely that of the symposium. The introductory section contains a general statement by the editors of the problems and issues to be discussed and an inventory by Professor G. P. Murdock of the current status of the world’s hunting and gathering peoples. Each of the remaining sections corresponds to one of the topical sessions of the symposium, and each section contains the relevant papers as well as the edited transcript of the symposium discussion. As editors we are aware that publishing verbatim material from symposia docs not always work out successfully; we hope that our attempt at editing has eliminated redundancy and inconsequential material while still conveying some of the excitement and the confrontation of different viewpoints that characterized the symposium itself.

On behalf of all the participants we want to thank the Wenner-Gren Foundation for Anthropological Research for providing the financial support that made possible the symposium and the preparation of this volume. Mrs. Lita Osmundsen and the excellent staff of the Foundation in New York solved the complex problems of travel, visas, and financing with their usual efficient dispatch, enabling all of us to converge miraculously on Chicago on the appointed day.

Sol Tax conceived the idea of a symposium on Man the Hunter and brought it to fruition. As chairman of the meetings he brought us together on time and skillfully kept speakers within their time limits; on behalf of a group of anthropologists who had a great deal to say, we offer Sol our affectionate resentment. The staff of Current Anthropology worked to distribute advance papers, to compile accurate transcripts and address lists, and generally to keep the symposium running smoothly.

Our thanks go as well to Lee Pravatiner and the staff of the Center for Continuing Education. With accommodations, food service, press, duplicating facilities, and meeting rooms all under one roof, the Center was an ideal place for a symposium of this size and complexity. Few of the participants realized the contribution that Mr. Pravatiner made to the success of the meeting; he attended to countless details of seating arrangements, reservations, messages, transcription, and mimeographing, and did so tactfully and unobtrusively. Personally we were struck by the contrast between the complex social and technological system that enabled us to meet and the much simpler systems of the hunting and gathering peoples we were discussing.

In addition we should mention the pleasant evening that many of us spent at the American Indian Center in north Chicago. Our thanks go to members of the Center and to its director Robert Rietz, for their hospitality.

The transcription and editing of the twenty hours of tapes from the sessions provcd to be a formidable job; we are particularly grateful to Paul L. DeVore of the University of Chicago for the 180 pages of transcription and to Jill Nash of Harvard University for her aid in editing the transcript and for many other editorial services. Miss Nash also r8ad through the entire manuscript and made many helpful suggestions which have been incorporated in the final version. Dr. David A. Horr of Harvard undertook the compilation of the references and handled many editorial details in the latter half of the book.

The drawings were executed by Judith Tempkin and Jane Britton; the former also assisted in the final preparation of the bibliography. lv1rs. Marcia Harding Anderson, Mrs. Elizabeth Burnham, and Mrs. Linda Moseley, all of the staff of the Department of Social Relations of Harvard University, typed portions of the manuscript; the final version was produced by Mrs. Nellie Miller.

Richard Lee offers a special vote of thanks to the students in Social Relations 251 and 252, graduate seminars at Harvard in the spring semesters of 1966 and 1967, respectively. The members of these seminars read most of the preliminary manuscripts and their lively discussions did much to clarify the core issues presented in the book.

Both of us wish to thank our colleagues in the Department of Social Relations at Harvard for providing a congenial intellectual atmosphere and for making a number of useful suggestions on specific portions of the manuscript; we appreciate particularly the help of John W. M. Whiting, A. Kimball Romney, Evon Z. Vogt and David H. P. Maybury-Lewis. We also want to thank our publisher, Alexander J. Morin, for his patience and forbearance while we labored to complete the manuscript before our departure for further field work among the Bushmen.

Finally we acknowledge our major debt to our contributors, many of whom are huntergatherers in spirit as well as in professional interest. No two anthropological field workers share exactly the same motivations and worldview, except perhaps a common interest in understanding the human condition. We cannot avoid the suspicion that many of us were led to live and work among the hunters because of a feeling that the human condition was likely to be more clearly drawn here than among other kinds of societies.

RICHARD B. LEE

IRVEN DEVORE

Contents

Part I: Introduction

-

Problem in the Study of Hunters and Gatherers, Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore

2. The Current Status of the World’s Hunting and Gathering Peoples, George Peter Murdock

Part II: Ecology and Economics

3. The “Hunting” Economies of the Tropical Forest Zone of South America: An Attempt at Historical Perspective, Donald W. Lathrap

4. What Hunters Do for a Living, or, How To Make Out on Scarce Resources, Richard B. Lee

5. An Introduction to Hadza Ecology, James Woodburn

6. Coping with Abundance: Subsistence on the Northwest Coast, Wayne Suttles

7. Subsistence and Ecology of Northern Food Gatherers with Special Reference to the Ainu, Hitoshi Watanabe

8. The Netsilik Eskimos: Adaptive Processes, Asen Balikei

9. Discussions, Part II

a. The Central Eskimo: A Marginal Case?

b. Notes on the Original Affluent Society

c. Does Hunting Bring Happiness?

d. Hunting vs. Gathering as Factors in Subsistence

e. Measuring Resources and Subsistence Strategy

Part III: Social and Territorial Organization

10. Ownership and Use of Land among the Australian Aborigines, L. R. Hiatt

11. Stability and Flexibility in Hadza Residential Groupings, James Woodburn

12. The Diversity of Eskimo Societies, David DaT(IQSs

13. The Nature of Dcgrib Socioterritorial Groups, June Helm

14. The Birhor of India and Some Comments on Band Organization, B. J. Williams

15. The Importance of Flux in Two Hunting Societies, Colin M. Turnbull

16. Southeastern Australia: Level of Social Organization, Arnold R. Pilling

17. Discussions, Part III

a. On Ethnographic Reconstruction

b. The Problem of Lineage Organization

c. Analysis of Group Composition

d. Social Determinants of Group Size

e. Resolving Conflicts by Fission

f. Territorial Boundaries

g. Predation and Warfare

h. Hunter Social Organization: Some Problems of Method

i. Typology and Reconstruction: A Shoshoni Example

Part IV: Marriage and Models in Australia

18. Gidjingali Marriage Arrangements, L. R. Hiatt

19. “Marriage Classes” and Demography in Central Australia, M. J. Meggitt

20. Demographic and Ecological Influences on Aboriginal Australian Marriage Sections, Aram A. rengoyan

21. Australian Marriage, Land-Owning Groups, and Initiations, Frederick C. C. Rose

22. Discussions, Part IV

a. Gerontocracy and Polygyny

b. Gidjingali Marriage Arrangements: Comments and Rejoinder

c. The Use and Misuse of Models

d. The Statistics of Kin Marriage: A Non-Australian Example

Part V: Demography and Population Ecology

23. Epidemiological Factors: Health and Disease in Hunter-Gatherers, Frederick L. Dunn

24. Some Predictions for the Pleistocene Based on Equilibrium Systems among Recent Hunter-Gatherers, Joseph B. Birdsell

25. Discussions, Part V

a. The Demography of Hunters: Eskimo Example

b. Population Control Factors: Infanticide, Disease, Nutrition, and Food Supply

c. The Magic Numbers “25” and “500”: Determinants of Group Size in Modern and Pleistocene Hunters

d. Pleistocene Family Planning

Part VI: Prehistoric Hunter-Gatherers

26. Traces of Pleistocene Hunters: An East African Example, Glynn L. Isaac

27. A Theoretical Framework for Interpreting Archeological Materials, L. G. Freeman, Jr.

28. Methodological Considerations of the Archeological Use of Ethnographic Data, Lewis R. Binford

29. Ethnographic Data and Understanding the Pleistocene, Sally R. Binford

30. Studies of Hunter-Gatherers as an Aid to the Interpretation of Prehistoric Societies, J. Desmond Clark

31. I. Discussions, Part VI

a. Hunters in Archeological Perspective

b. The Archeological Visibility of Food Gatherers

c. The Use of Ethnography in Reconstructing the Past

Part VII: Hunting and Human Evolution

32. The Evolution of Hunting, Sherwood L. Washburn and C. S. Lancaster

33. Hunting: An Integrating Biobehavior System and Its Evolutionary Importance, William S. Laughlin

34. Causal Factors and Processes in the Evolution of Pre-farming Societies, Julian H. Steward

35. Discussions, Part VII

a. Are the Hunter-Gatherers a Cultural Type?

b. Primate Behavior and the Evolution of Aggression

c. Future Agenda

Part VIII: The Concept of Primitiveness

36. The Concept of Primitiveness, Claude Levi-Strauss

References

Index

Symposium on Man the Hunter

WENNER-GREN FOUNDATION FOR ANTHROPOLOGICAL RESEARCH

PARTICIPANTS

Sol Tax, Chairman

University of Chicago

Alexander A. Alland

Columbia University

James N. Anderson

University of California, Berkeley

Asen Balikci

Universite de Montreal

Marco Bicchieri

Central Washington State College

Lewis R. Binford

University of New Mexico

Sally R. Binford

Los Angeles, California

Joseph B. Birdsell

University of California, Los Angeles

Jean Briggs

Memorial University of Newfoundland

Ralph Bulmer

University of Auckland

Napoleon A. Chagnon

Pennsylvania State University

J. Desmond Clark

University of California, Berkeley

Georges Condominas

Ecole Pratique des Hautes Etudes, Paris

William Crocker

Smithsonian Institution

Ralph Crocombe

Australian National University

David Damas

McMaster University

James Deetz

Brown University

Edward Deevey, Jr.

Dalhousie University

P. E. de Josselin de Jong

Leiden University

Irven DeVore

Harvard University

A. Jorge Dias

Lisbon

Frederick L. Dunn

Hooper Foundation

University of California, San Francisco

Fred Eggan

University of Chicago

Leslie G. Freeman, Jr.

University of Chicago

Peter M. Gardner

University of Texas

David M. Hamburg

Stanford University

June Helm

University of Iowa

L. R. Hiatt

University of Sydney

F. Clark Howell

University of California, Berkeley

Roger C. Owen

City University of New York

Angel Palerm

Pan American Union, Mexico

Arnold R. Pilling

Wayne State University

Merrick Posnansky

University of Ghana

Edward S. Rogers

Royal Ontario Museum, Toronto

Frederick G. G. Rose

Institut fur Volkerkunde, Berlin

James R. Sackett

University of California, Los Angeles

Marshall D. Sahlins

University of Michigan

Edward Schieffelin

University of California

Glynn L. Isaac

University of California, Berkeley

Irawati Karve

University of Poona

C. S. Lancaster

Rutgers University

Donald W. Lathrap

University of Illinois

William S. Laughlin

University of Connecticut

Duhyan Lee

Seoul National University

Richard B. Lee

University of Toronto

Claude Levi-Strauss

College de France

Toichi Mabuchi

Tokyo Metropolitan University

Lorna Marshall

Cambridge, Mas .

M. J. Meggitt

City University of New York

George Peter Murdock

University of Pittsburgh

Chie Nakane

University of Tokyo

David M. Schneider

University of Chicago

William Shack

University of California, Berkeley

Lauriston Sharp

Cornell University

Surajit Sinha

Indian Institute of Management, Calcutta

Richard Slobodin

McMaster University

Julian H. Steward

University of Illinois

Stuart Struever

Northwestern University

Wayne Suttles

Portland State College

Reina Torres de Arauz

Universidad de Panama

Colin M. Turnbull

Hofstra University

Sherwood L. Washburn

University of California, Berkeley

Hitoshi Watanabe

University of Tokyo

James Woodburn

London School of Economics

Aram A. Yengoyan

University of Michigan

John W. M. Whiting

Harvard University

B. J. Williams

University of California, Los Angeles

Part I: Introduction

1. Problems in the Study of Hunters and Gatherers

Richard B. Lee and Irven DeVore

Cultural Man has been on earth for some 2,000,000 years; for over 99 per cent of this period he has lived as a hunter-gatherer. Only in the last 10,000 years has man begun to domesticate plants and animals, to use metals, and to harness energy sources other than the human body. Homo sapiens assumed an essentially modern form at least 50,000 years before he managed to do anything about improving his means of production. Of the estimated ISO billion men who have ever lived on earth, over 60 per cent have lived as hunters and gatherers; about 35 per cent have lived by agriculture and the remaining few per cent have lived in industrial societies.

To date, the hunting way of life has been the most successful and persistent adaptation man has ever achieved. Nor does this evaluation exclude the present precarious existence under the threat of nuclear annihilation and the population explosion. It is still an open question whether man will be able to survive the exceedingly complex and unstable ecological conditions he has created for himself. If he fails in this task, interplanetary archeologists of the future will classify our planet as one in which a very long and stable period of small-scale hunting and gathering was followed by an apparently instantaneous efflorescence of technology and society leading rapidly to extinction. “Stratigraphically,” the origin of agriculture and thermonuclear destruction will appear as essentially simultaneous.

On the other hand, if we succeed in establishing a sane and workable world order, the long evolution of man as a hunter in the past and the (hopefully) much longer era of technical civilization in the future will bracket an incredibly brief transitional phase of human history—a phase which included the rise of agriculture, animal domestication, tribes, states, cities, empires, nations, and the industrial revolution. These transitional stages are what cultural and social anthropologists have chosen as their particular sphere of study. We devote almost all of our professional attention to organizational forms that have emerged within the last 10,000 years and that are rapidly disappearing in the face of modernization.

It is appropriate that anthropologists take stock of the much older way of life of the hunters. This is not simply a study of biological evolution, since zoologists have come to regard behavior as central to the adaptation and evolution of all species. The emergence of economic, social, and ideological forms are as much a part of human evolution as are the developments in human anatomy and physiology.

The time is rapidly approaching when there will be no hunters left to study. Our aim in convening the symposium on Man the Hunter was to bring together those who had recently done field work among the surviving hunters with other anthropologists, archeologists, and evolutionists who are interested in the results of these studies. But it was also clear that there were a series of issue8 among social anthropologists that required clarification before a dialogue with others could become meaningful. Therefore, the first half of this book is devoted to the presentation of new data on cOI1lemporary hunters, along with discussion and evaluation of current issues. The later chapters consider the relevance of these data to the reconstruction of life in the past.

A number of divergent viewpoints are represented in this volume and many of the issues to be raised remain unsolved. As both editors and partisans, it is our task to point out areas of general agreement while trying to avoid glossing over real differences where they occur. Considering the many points of view presented at the symposium, it would be impossible to touch on all of the interesting material. We make no apologies for our selection but offer it as a partial guide to the papers and discussions.

Defining Hunters

The symposium considered the definition of “hunters” but did not succeed in satisfying everyone. An evolutionary definition would have been ideal; this would confine hunters to those populations with strictly Pleistocene economies-no metal, firearms, dogs, or contact with nO!1-hunting cultures. Unfortunately such a definition would effectively eliminate most, if not all, of the peoples reported at the symposium since, as Marshall Sahlins pointed out, nowhere today do we find hunters living in a world of hunters.

Murdock (Chapter 2, this volume) and others took an organizational view which equated hunting and gathering with the “band” level of social organization. However, not all hunters live in bands. Suttles, for example (Chapter 6), documents the quite substantial non-agricultural tribal societies of the Northwest coast of North America. Judging from recent archeological evidence from the Paleolithic of France and of European Russia, a number of ancient hunting societies may have operated on a similar scale.

A further consideration was introduced by Lathrap (Chapter 3) and others who cited a number of hunting peoples who were “failed” agriculturalists. This readaptation to hunting, or “devolution” as it has been called, characterized such classic “hunters” as the Siriono of South America and the Veddas of Ceylon.

It was clear that there was much to be learned even from the ambiguous cases of tribal hunters, “devolved” hunters, and reformed hunters. To throw out impure cases was to lose the chance of gaining any significant understanding of modes of adaptation, group structure, social control, and settlement patterns. The symposium agreed to consider as hunters all cases presented, at least in the first instance. It was also generally agreed to use the’ term “hunters” as a convenient shorthand, despite the fact that the majority of peoples considered subsisted primarily on sources other than meat—mainly wild plants and fish.

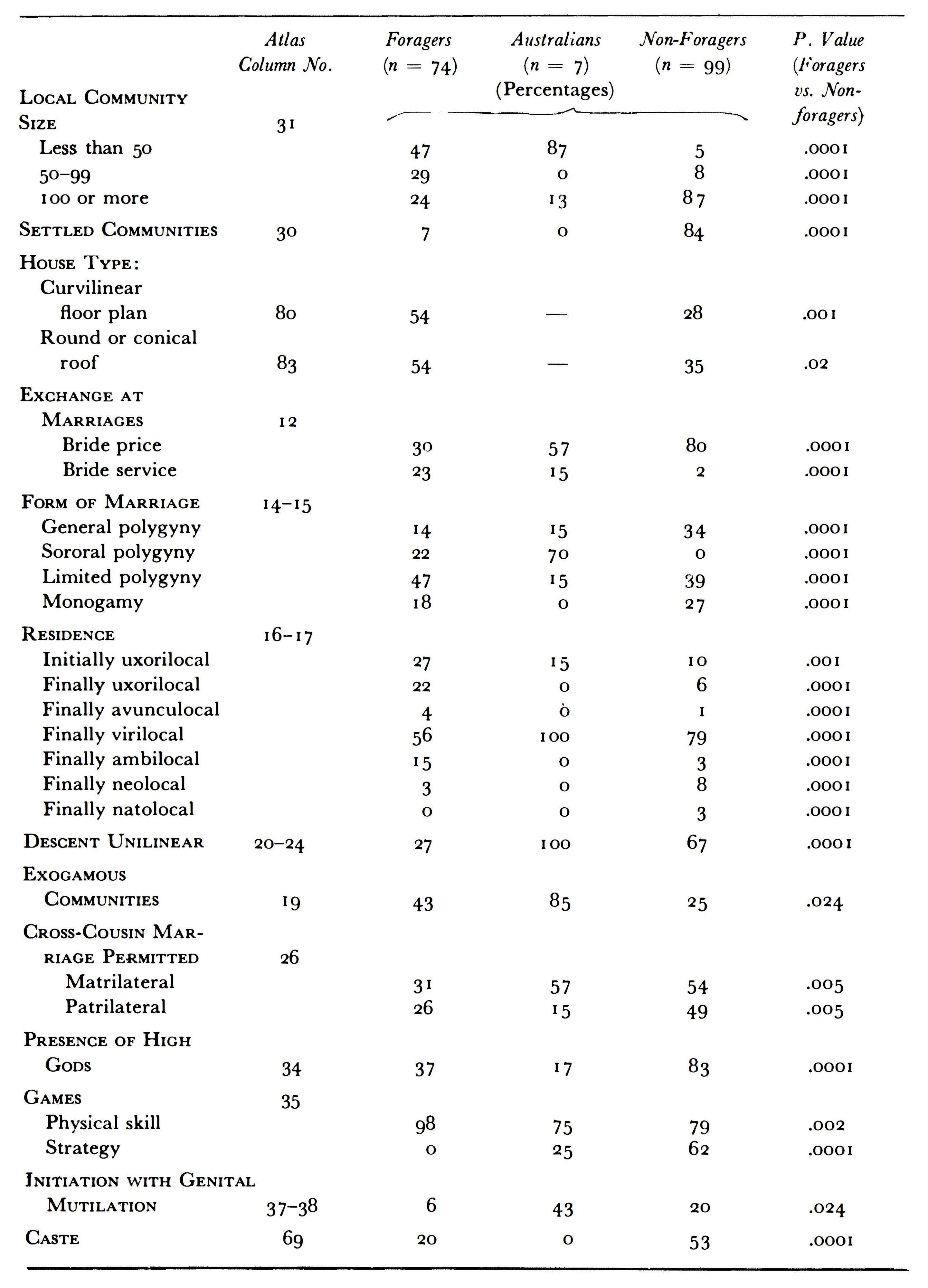

The Representativeness of Our Sample of Hunters

There has been a burst of field research on hunting peoples in the last ten years, and this symposium was the first opportunity to bring together this diverse group of field workers.

The Australian contingent included L. R. Hiatt (Arnhem Land), M. J. Meggitt (Walbiri), Arnold Pilling (Tiwi), and Aram Yengoyan, all of whom have done field work in the 1950’s and 1 960’S, as well as Birdsell, Rose, and Sharp whose field work dates to the 1930’s and 1940’s. Workers from Africa included Bicchieri, Turnbull (Mbuti), Woodburn (Hadza), and Marshall, Lee, and DeVore on the!Kung Bushmen. Field work in Asia was reported by Dunn, Gardner, Sinha, Watanabe, and Williams. Lathrap and Crocker presented data on the part-time hunters of tropical South America. The largest group had done field work in North America: Balikci, Damas, and Laughlin on the Eskimos; Helm, Rogers, and Slobodin on subarctic Indians; and Owen and Suttles on Indians of the Pacific coast. Julian H. Steward, in many ways the founder of modern hunter-gatherer studies, submitted a paper, but was prevented by illness from attending the conference itself.

One of the first questions considered at the symposium was whether the sample currently available to ethnographers is representative of the range of habitats which hunters occupied in the past. Ever since the origin of agriculture, Neolithic peoples have been steadily expanding at the expense of the hunters. Today the latter are often found in unattractive environments, in lands which are of no use to their neighbors and which pose difficult and dramatic problems of survival. The more favorable habitats have long ago been appropriated by peoples with stronger, more aggressive social systems.

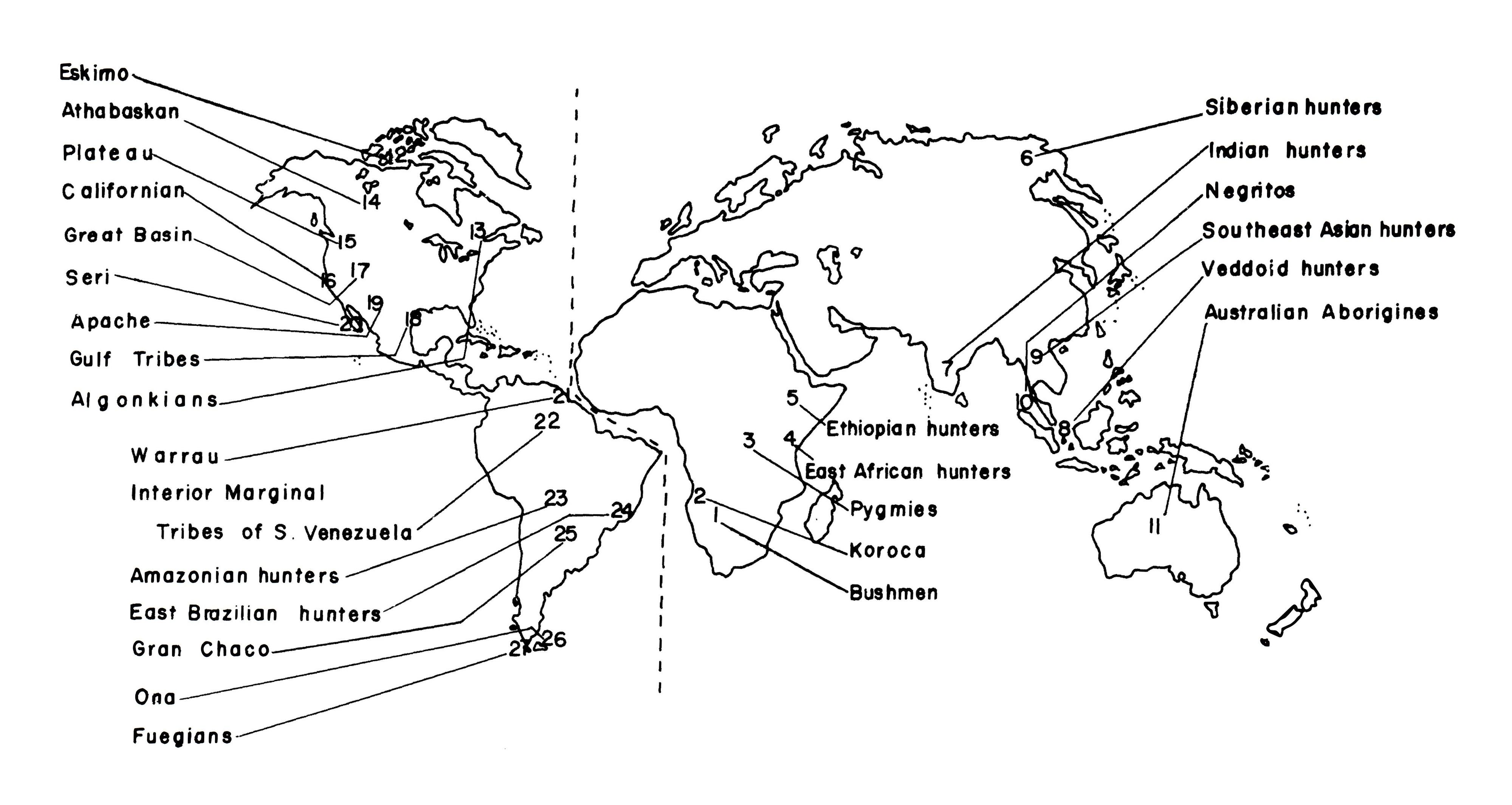

Taking hunters as they are found, anthropologists have naturally been led to the conclusion that their life (and by implication the life of our ancestors) was a constant struggle for survival. The three maps presented in the frontispiece show a radiGally different picture. In 10,000 B.C., on the eve of agriculture, hunters covered most of the habitable globe, and appeared to be generally most successful in those areas which later supported the densest populations of agricultural peoples. By A.D. 1500 the area left to hunters had shrunk drastically and their distribution fell largely at the peripheries of the continents and in the inaccessible interiors. However, even at this late date, hunting peoples occupied all of Australia, most of western and northern North America, and large portions of South America and Africa. This situation rapidly changed with the era of colonial expansion, and by IgOO, when serious ethnographic research got under way, much of this way of life had been destroyed. As a result, our notion of unacculturated huntergatherer life has been largely drawn from peoples no longer living in the optimum portion of their traditional range.

To mention a few examples, the Netsilik Eskimos, the Arunta, and the!Kung Bushmen are now classic cases in ethnography. However, the majority of the precontact Eskimos, Australian aborigines, and Bushmen lived in much better environments. Two-thirds of the Eskimos, according to Laughlin, lived south of the Arctic circle, and the populations in the Australian and Kalahari deserts were but a fraction of the populations living in the well-watered regions of southeast Australia and the Cape Province of Africa. Thus, within a given region the “classic cases” may, in fact, be precisely the opposite: namely, the most isolated peoples who managed to avoid contact until the arrival of the ethnographers. In order to understand hunters better it may be more profitable to consider the few hunters in rich environments, since it is likely that these peoples will be more representative of the ecological conditions under which man evolved than are the dramatic and unusual cases that illustrate extreme environmental pressure. Such a perspective may better help us to understand the extraordinary persistence and success of the human adaptation.

Ethnographic Reconstruction

Many of the best-known studies of huntergatherers have relied on ethnographic reconstructions of situations that were no longer intact. In the early years of field anthropology, Kroeber in California, Boas on the Northwest coast, and Radcliffe-Brown in the Andaman islands and Australia compiled the recollections of older informants to produce a picture of the culture and society. The “facts” of the case were thought to include the verbalized cultural tradition—language, myths, folktales, and kin terms—and concrete expressions— rituals, house types, tools, dress, and religious objects. As anthropology developed, however, a different view emerged about what constituted the ethnographic facts. More attention was paid to the study of individuals and groups in ongoing social systems. The interest in ideology was retained, but this was tempered by the task of comparing stated norms with observed behavior. When discrepancies between “real” and “ideal” came to light, the ethnographer could then make further inquiries and observations and attempt to explain “how the system really works.”

The shortcoming of the reconstructive method is that there is no means of testing and rechecking hypotheses. After the socioeconomic system ceases to function, the only check available is the test of internal consistency, and the early ethnographers were more or less successful in constructing models of social systems that were self-consistent.

The controversy on this question is very much alive in current social anthropology and the issue forms a central theme in this volume (Chapters 10, qa, 17c, 17h, 18, Ig, 22b, and 22(’). The relevance for methodology hinges on the question of how much of an ongoing system can be reconstructed 25–50 years after the event, solely on the basis of informants’ accounts. Birdsell and others take the pessimistic view that such important features as group structure and territorial relations vanish with contact (Chapter 17a). Williams, in the same vein, reports that he was unable to reconstruct the residence arrangements of a Birhor group whose campsite had been mapped in detail by another anthropologist only six years previously. Woodburn notes that the Badza present themselves as having a matrilineal descent system, when in fact the kinship and the group structure are bilateral; the fiction is used by the Hadza to emulate their agricultural, matrilineal neighbors. This fact is significant in itself, but more important, it would make impossible an accurate reconstruction of Badza social organization at a later date, if one had to rely solely on the memory of informants.

On the other hand, several participants were more sanguine about the persistenee of cultural traditions into the postcontact period. Levi-Strauss cited the example of the retention of marriage ideology by Australian aborigines in the face of acculturation and demographic reverses (Chapter 17b, 17c). In addition, careful reconstructions of precontact ecological situations were presented by Watanabe, for the Ainu of the 1880’S (Chapter 7), and by Balikci, for the Netsilik Eskimos in 1919–20 (Chapter 8).

Finally, June Helm pointed out that the group structure of such diverse peoples as the Dogrib Indians, the!Kung Bushmen, and the Nambikwara showed striking similarities in spite of widely differing social ideologies (Chapter 13). This suggests that small-scale societies may arrive independently at similar solutions to similar demographic and ecological problems. Without the opportunity of observing behavior, however, such an important point would be impossible to establish. This problem is discussed further by Anderson (Chapter 17c).

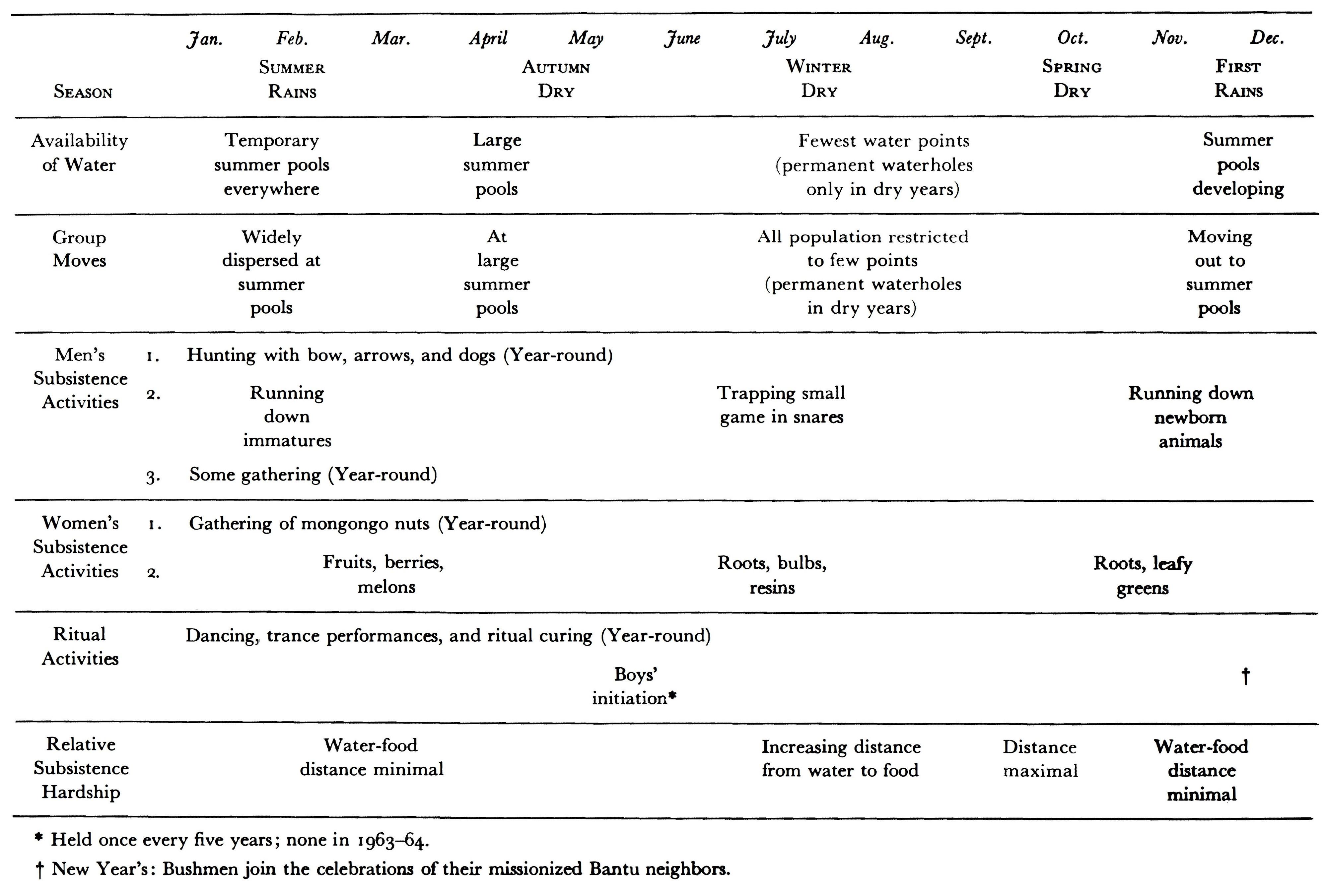

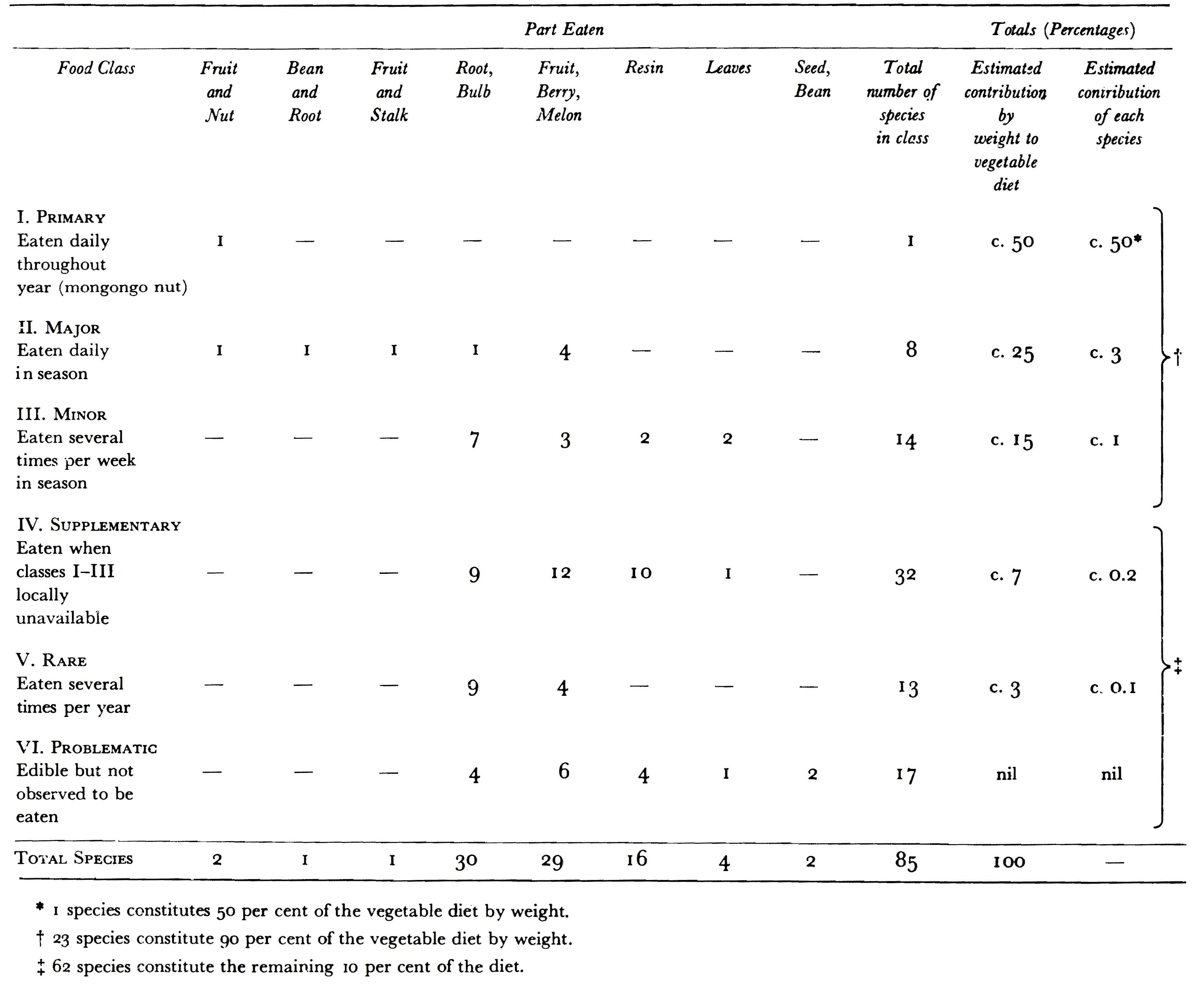

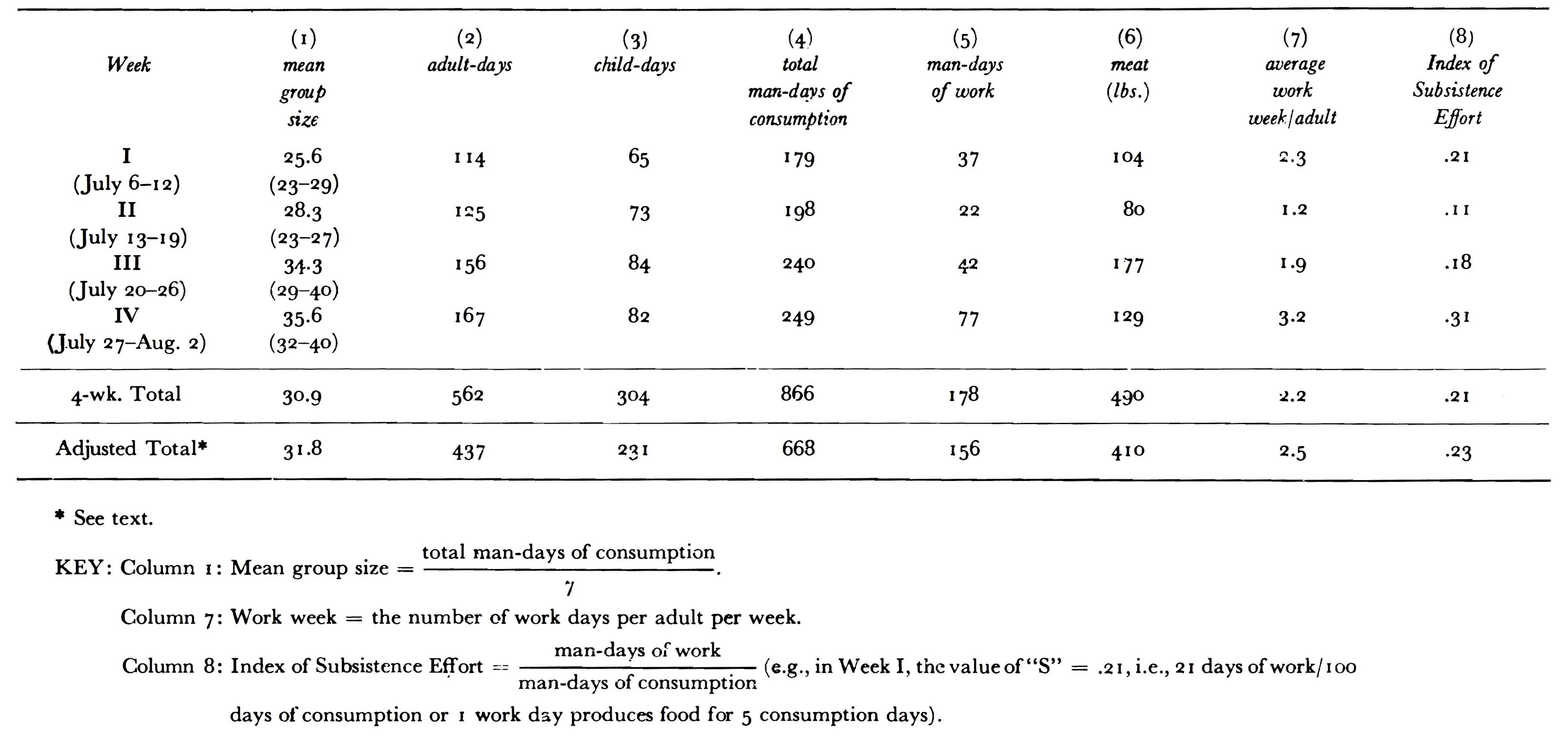

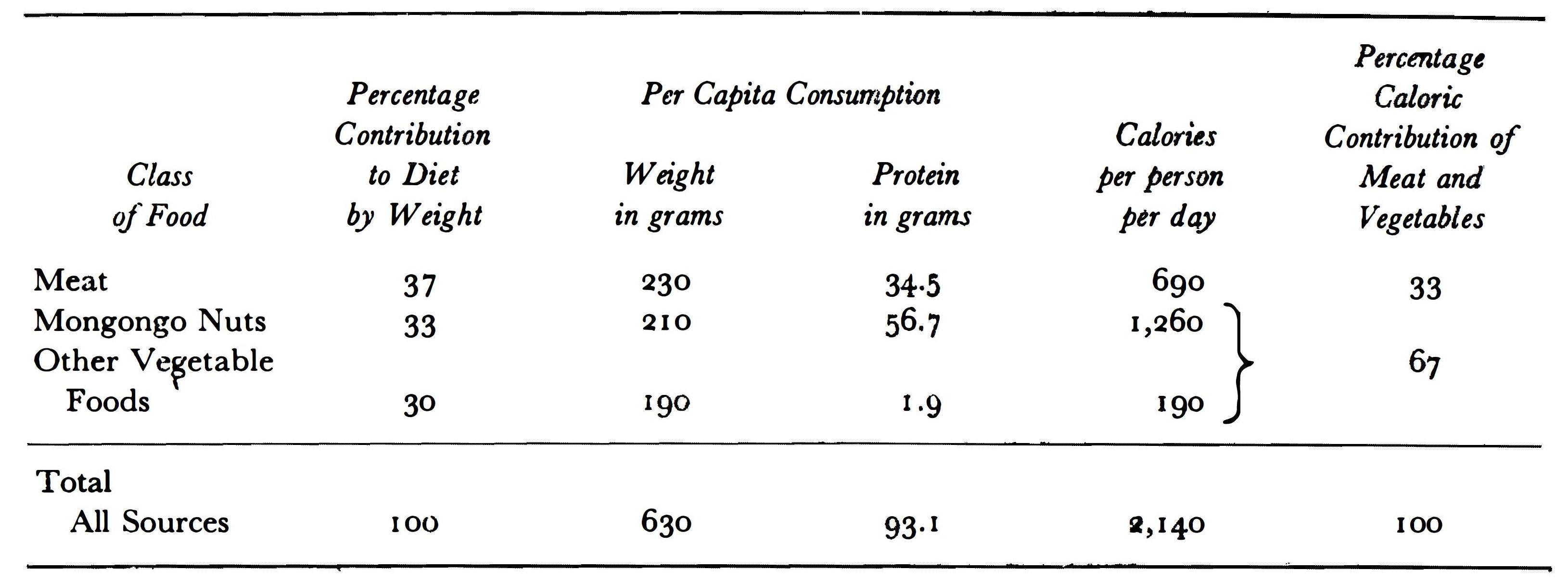

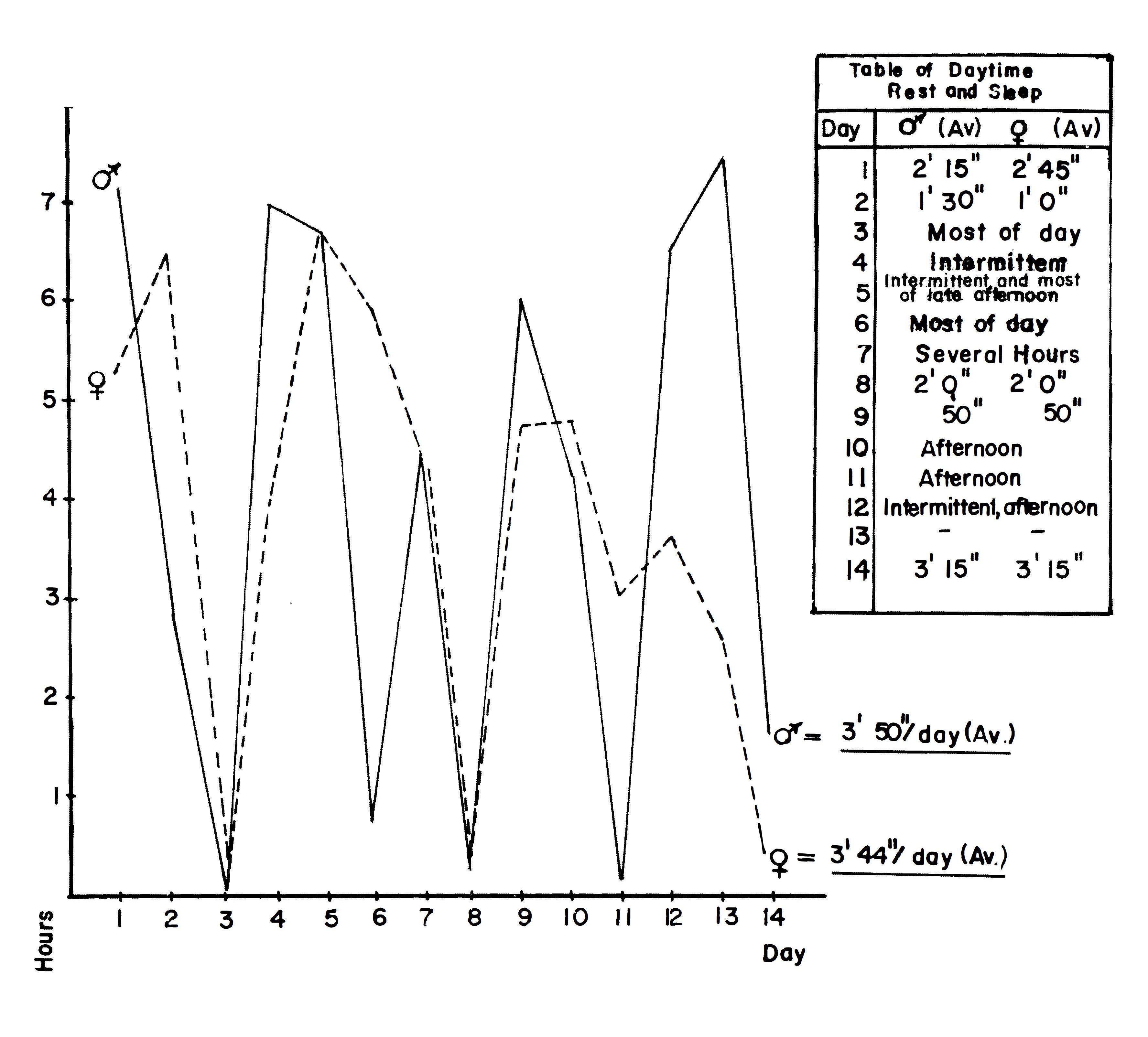

The Subsistence Base

Strictly speaking, hunting apd gathering refers to a mode of subsistence, and many of the conference papers discussed problems of ecology and economic organization. Several field workers pointed out that the subsistence base of hunters was much more substantial than had been previously supposed. It came as a surprise to some that even the “marginal” hunters studied by ethnographers actuallywork short hours and exploit abundant food sources. Several hunting peoples lived well on two to four hours of subsistence effort per day and were not observed to undergo the periodic crises that have been commonly attributed to hunters in general (Chapters 4, 5, and gb). Other peoples for whom detailed activity data were unavailable were nevertheless reported to show a “lack of concern” about the problem of finding food. This led the conference participants to speculate whether lack of “future orientation” brought happiness to the members of hunting societies, an idyllic attitude that faded when changing subsistence patterns forced men to amass food surpluses to bank against future shortages (Chapter gc).

Dissenting views were reported. Balikci spoke of a “constant ecological pressure” which caused real hardship and anxiety among the Netsilik Eskimos (Chapter 8). Williams (Chapter gc) found that the Birhor of India not only worked hard for their food but often went hungry. It was clear that Sahlins’ characterization of the hunters (Chapter gb) as the “original affluent society” would not apply in all cases. However Sahlins’ argument served to underline the point that anthropologists have tended to view the hunters from the vantage point of the economics of scarcity. Viewed on their own terms, the hunters appear to know the ibod’ire-sources of their habitats and are quite capable of taking the necessary steps to feed themselves. It is unlikely that hunters would have deliberately chosen the catch-as-catch-can existence that has been ascribed to them. Since a routine and reliable food base appears to be a common feature among modern huntergatherers, we suspect that the ancient hunters living in much better environments would have enjoyed an even more substantial food supply.

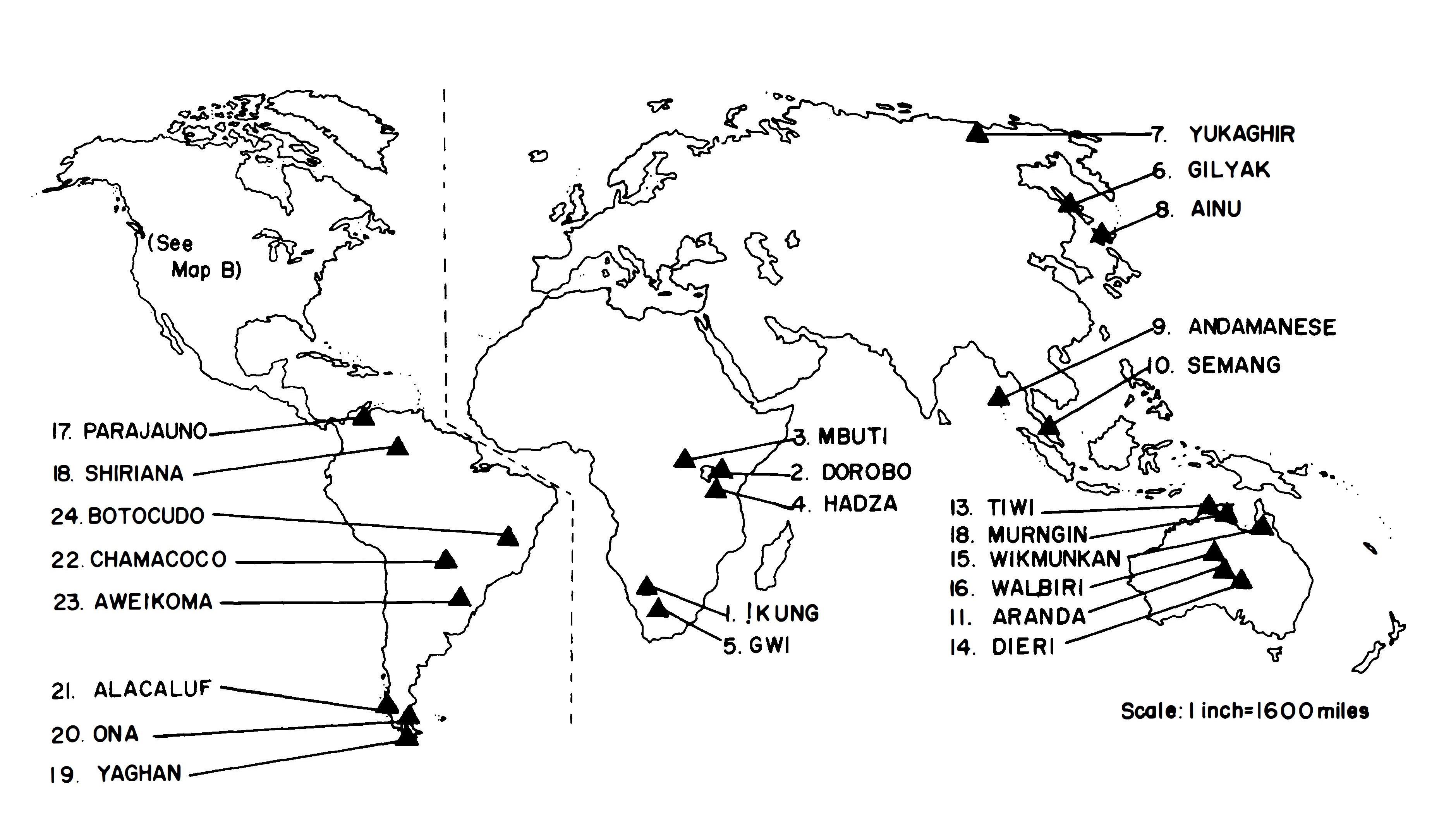

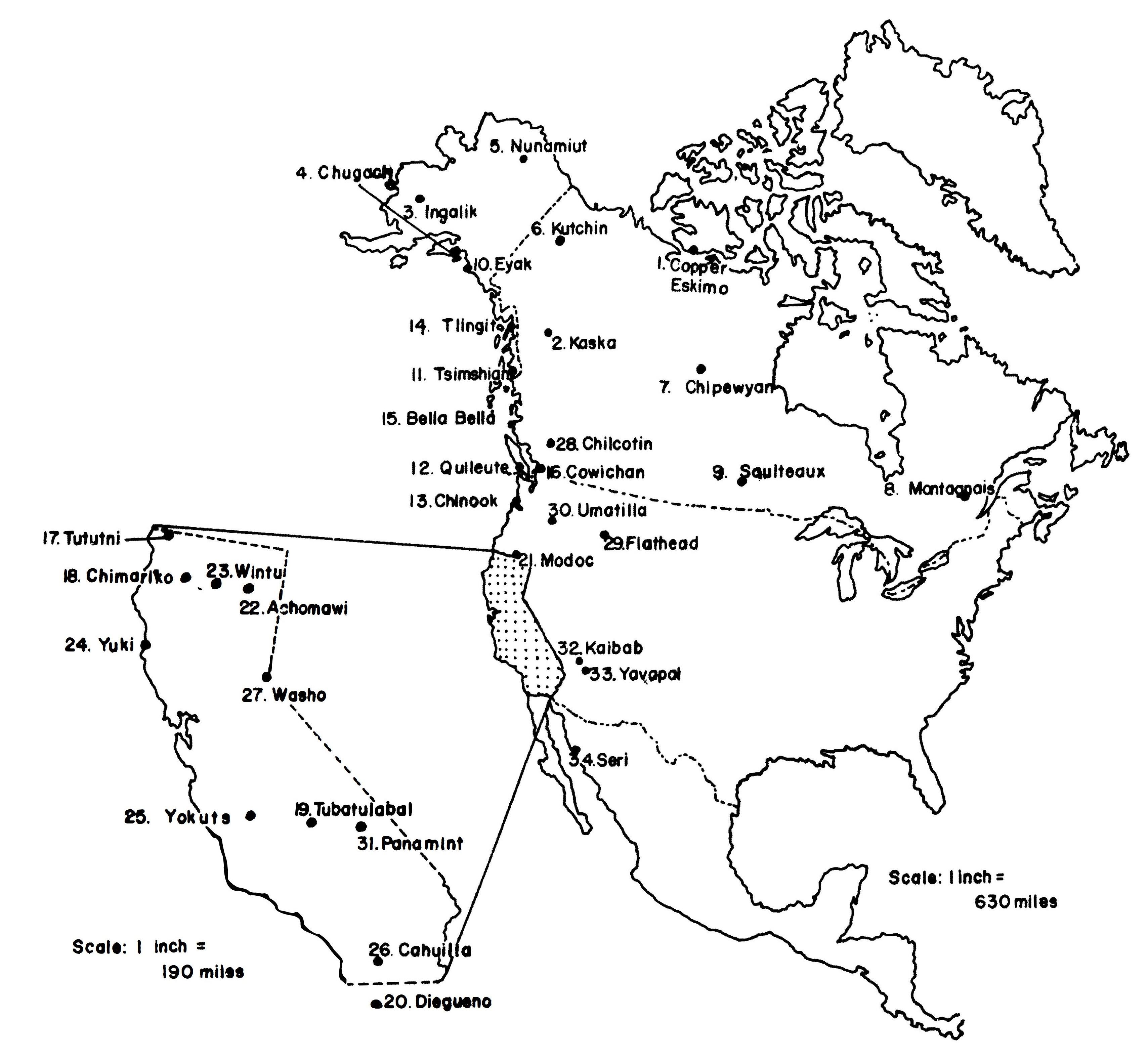

Hunting vs. Gathering

The hunting of mammals has been considered the characteristic feature of the subsistence of early man, and two chapters in this volume explore the implications of hunting for human evolution (Washburn and Lancaster, Chapter 32; and Laughlin, Chapter 33). Modern hunters, however, depend for most of their subsistence on sources other than meat, mainly vegetable foods, fish, and shell fish. Only in the arctic and subarctic areas where vegetable foods are unavailable do we find the textbook examples of mammal hunters. Over the rest of the world, hunting appears to provide only 20 to 40 per cent of the diet (Lee, Chapter 4).

Binford, Washburn and Lancaster, and others expressed the view that fishing, seedgrinding, and hunting with dogs are late adaptations, dating from the Mesolithic and therefore not characteristic of Pleistocene conditions. Thus, the eclectic diet of the modern hunters may tell us little about the food habits of early man. Our own view is that vegetable foods in the form of nuts, berries, and roots were always available to early man and were easily exploited by even the simplest of technologies. It is also likely that early woman would not have remained idle during the Pleistocene and that plant foods ^which are so important in the diet of inland huntergatherers today, would have played a similar role in the diet of early peoples. We agree, however, that hunting would become increasingly important as populations migrated out of the tropics into areas where plant foods are scarce. In addition, hunting is so universal and is so consistently a male activity that it must have been a basic part of the early cultural adaptation, even if it provided only a modest proportion of the food supplies.

Social and Territorial Organization

The analysis of the social structure of the hunting and gathering peoples proved to be a particularly difficult area of investigation because of the ambiguous conditions in which hunters are currently found. Fluidity of band composition appeared to be the most characteristic feature of the modern hunters, but participants disagreed on whether this flexibility was basic to the hunting way of life or whether it was a product of recent acculturation. We will briefly outline the history of band theory from Radcliffe-Brown, through Steward to Service and then go on to consider the evidence from recent field . research.

The Patrilocal Band

Radcliffe-Brown gave this concept its modern expression in “Social Organization of Australian Tribes,” where he described the patrilineal, patrilocal, territorial, exogamous horde as “the important local group throughout Australia” (1931, p. 35). The horde was a group of patri-laterally related males who lived and worked within their totemic estate and exchanged women with other such male-centered groups. Steward, in a general review of huntergatherers, admitted the horde or “patrilineal band” as one of three types of group structure, but he added the composite bands of the Northern Athapaskans and the family bands of Great Basin Shoshoneans (1936, 1955). This three-part division was later called into question by Elman Service (1962), who took the view that the “patrilocal band,” as he called it, was not only the characteristic form of local organization in Australia but was also the basic form for all hunter-gatherers in the past (1962, pp. 65–67, 107–109). The composite and family bands, in Service’s view, were artifacts of recent acculturation and breakdown.

Recent research has cast doubt on the model of the patrilocal band. Hiatt, reviewing the literature on Australian local organization (1962), failed to find a single indisputable example of Radcliffe-Brown’s horde. The existence of patrilineal totemic clans has been well documented, but these functioned in ritual contexts and not as residential or economic units. Hiatt concludes:

It is now clear that over a great deal of the continent the male members of totemic descent groups did not live together on separate pieces of land. They commonly lived in communities that contained male members of several totemic descent groups and regularly sought food over areas that included totemic sites other than their own. Investigators that failed to find the horde in particular tribes were not (as some of them thought) observing aberrant forms of local organization. They were probably looking for something that never existed in any tribe (1962, p. 286).

Other ethnographers who had worked among “patrilocal band” peoples also Jailed to find this form of organization operating now or at any discoverable period in the past. Turnbull among the Mbuti Pygmies (Chapter 15), Lee^and Marshall among the Bushmen (Chapters 4 and I7c) and Meggitt (Chapter 19) all repo.^t the occurrence of composite and flexible local groups. Others have studied the ethno-historic record of peoples that Service claimed had patrilocal organization in the past. Helm on the Athapaskans (Chapter 13), Damas on the Eskimo (Chapter 12), and Pilling on the southeastern Australians (Chapter 16) present evidence that the composite bands observed in the present were characteristic of the earliest contact periods as well.

The patrilocal band, however, is not an empty category; cases are presented in which a patrilocal organization was in evidence, including the Ona of South America (Bridges, 1949, cited by Lathrap in Chapter 9d), the Kaiadilt of Australia (Tindale, 1962b, cited by Birdsell in Chapter 17a) and the Birhor of India (Williams in Chapter 14).

On the basis of present evidence, it appears that the patrilocal band is certainly not the universal form of hunter group structure that Service thought it was. Anderson (Chapter 17c), Turnbull (Chapter 15), Eggan (Chapter 17i), and others pointed out that the fluid organization of recent hunters has certain adaptive advantages, including the adjustment of group size to resources, the leveling out of demographic variance, and the resolution of conflict by fission.These features are independent of the effects of acculturation and would have been no less adaptive in precontact situations. Given these advantages, few of the conferees would endorse Service’s view that the patrilocal band “seems almost an inevitable kind of organization” or that “the composite band ... is obviously a product of the near destruction of aboriginal bands after contact with civilization” (1962, p.108). In fact Service himself has recently revised his opinion that the patrilocal band is inevitable.

Service has correctly drawn attention to the effects of contact on hunter-gatherer social organization, and this remains a difficult problem for the ethnographers. Although fluid organization makes ecological sense for many hunters, and could be shown to be more adaptive than patrilocal organization, in itself this is not evidence for aboriginal conditions.Since all hunting societies have suffered to some extent from contact, we may never be able to prove conclusively that one form or another was typical of the past in any specific case.

The Problem of Corporation

Sharp (Chapter 17h) warns against the use of “prefabricated constructs” in the study of band organization.The prevalence of such constructs may derive from the application of concepts developed in tribal societies to the study of simpler and smaller-scale societies. The social units of tribal societies are based on the control and husbandry of real property usually in the form of agricultural land or livestock (Fortes, 1953). In addition, the formal political institutions such as courts, councils, and chieftainships lends a distinctive character to social relations of tribesmen that is lacking in the smaller-scale societies of hunters and gatherers. Radcliffe-Brown’s well-known views on the universal importance of lineal descent and corporation (1952) may have led him to impose a corporate unilineal model on Australian local groups.

However, the reports in this volume make it clear that the hunter-gatherer band is not a corporation of persons who are bound together by the necessity of maintaining property. A corporation requires two conditions: a group of people must have some resource to incorporate about and there must be some means of defining who is to have rights over this resource. Among most hunter-gatherers one or both of these conditions are lacking. In Australia and among the Birhor, the patrilineal descent groups are present but these groups do not maintain exclusive rights to territorial resources (Hiatt in Chapter 10, Williams in Chapter 14). Among the Mbuti Pygmies the territories are well-defined but the membership in the resource-using group is open and changes frequently (Turnbull in Chapter 15). Among the Dogrib (Helm in Chapter 13), the Bushmen (Lee in Chapter 4), the central Eskimo (Damas in Chapter 12 and Balikci in Chapter 8) and the Hadza (Woodburn in Chapter 1 I), both the composition of the group and the range they exploit may vary from season to season. The existence of this variety makes it difficult to accept a model of hunter local groups that encapsulates each group of males within a territory, with exchange of women as the primary mode of communication between groups.

Flexibility and the Resolution of Conflict by Fission

Turnbull (lg6Sb and Chapter 15) has defined an important means of social control among the Mbuti Pygmies. When disputes arise within the band, the principals simply part company rather than allow the argument to cross the threshold of violence. By this seemingly simple device, harmony is maintained within the cooperating group without recourse to fighting or to formal modes of litigation. The essential condition seems to be the lack of exclusive rights to resources; thus it is a relatively simple matter for individuals and groups to separate when harmony is threatened. The effect of this practice is to keep the population circulating between band territories. Such a form of conflict resolution would not be possible in situations where social units are strictly defined and firmly attached to parcels of real estate. Woodburn and Lee reported a similar mode of conflict resolution among the Hadza and!Kung Bushmen; judging from their generally flexible group structure, resolution of conflict by fission may well be a common property of nomadic hunting societies.

Order and Chaos in Hunter-Gatherer Society

One of the attractions of the patrilocal band model is the neatness of its formulation. In such a model the society is structured by the operation of a small number of fundamental jural rules: territorial ownership by males, band exogamy, and viripatrilocal postmarital residence. However, the model leaves scant room either for local and seasonal variations in food supply or for variance in sex ratios and family size within and between local groups. Nor does the model, in many cases, accord with the observed facts, and in this light it appears to be more a convenience for the analyst than a workable socioeconomic system.

Flexibility of living arrangements presents at first a confusing and disorderly picture. Brothers may be united or divided, marriage may take place within or outside the local group, and local groups may vary in numbers from one week to the next. Helm (lg6sa and Chapter 13) has made a valuable contribution to the methodology of band-composition analysis. By tabulating the primary relative linkages within Athapaskan groups, she has been able to show that married couples always join groups in which a sibling, parent, or child of one of the spouses is already resident. This produces a local group whose members are joined by a series of links through brothers, sisters, and spouses, often centered around a strong core of male siblings. However, the orientation is bilateral rather than lineal and serves to unite persons into effective work groups regardless of whether the kinship ties are patrilateral, matrilateral, or affinal. Application of this method to other hunters reveals a similar mode of affiliation among the Nambikwara, Bushmen, Hadza, and Arnhem Land aborigines. The bilateral nature of hunter local groups is not simply a matter of people failing to conform to their stated jural rules; several of the peoples just mentioned do not express an ideology of fixed membership groups. There is order in hunter-gatherer society, although not necessarily an order imposed by the operation of residence and descent rules.

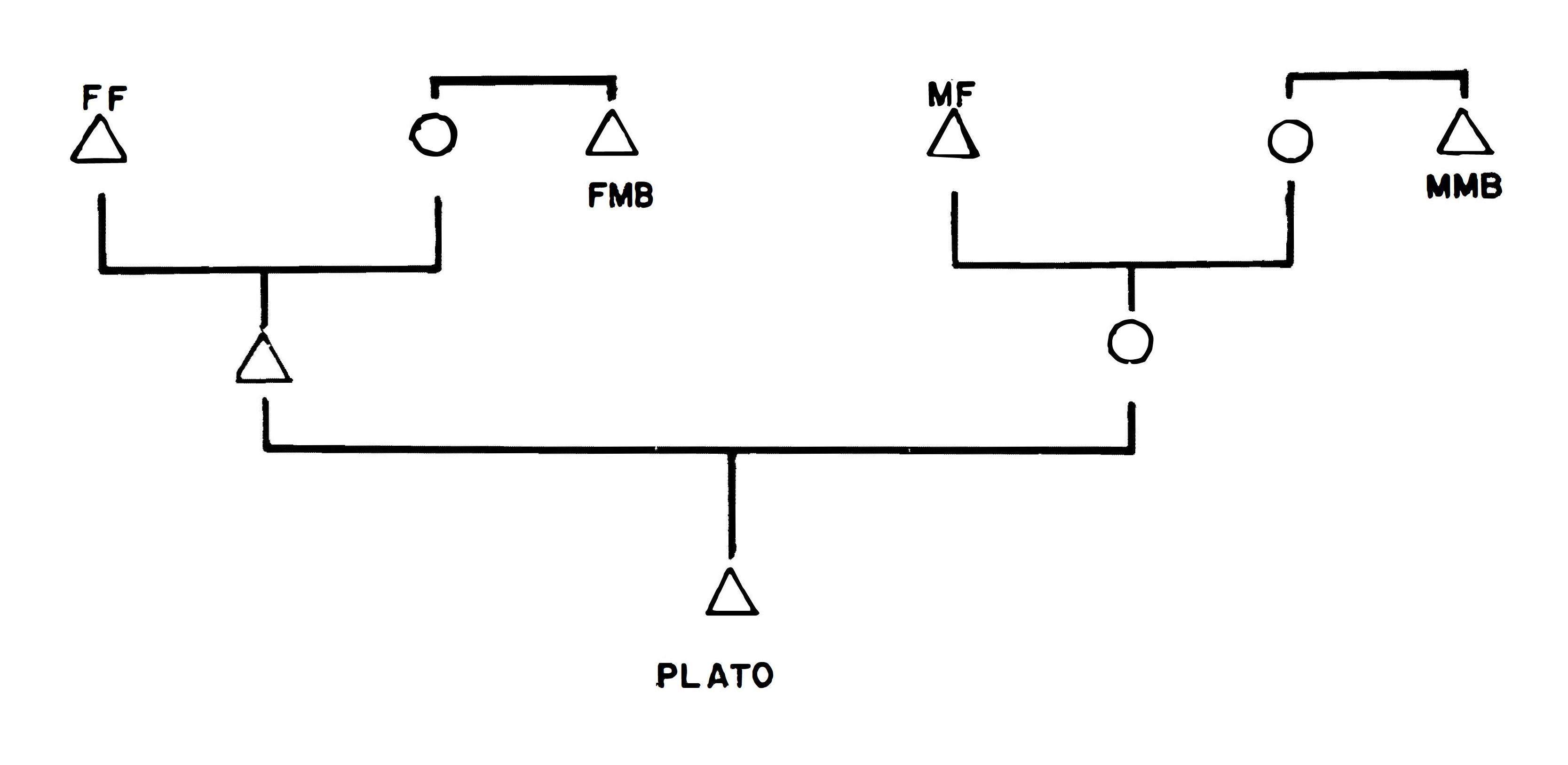

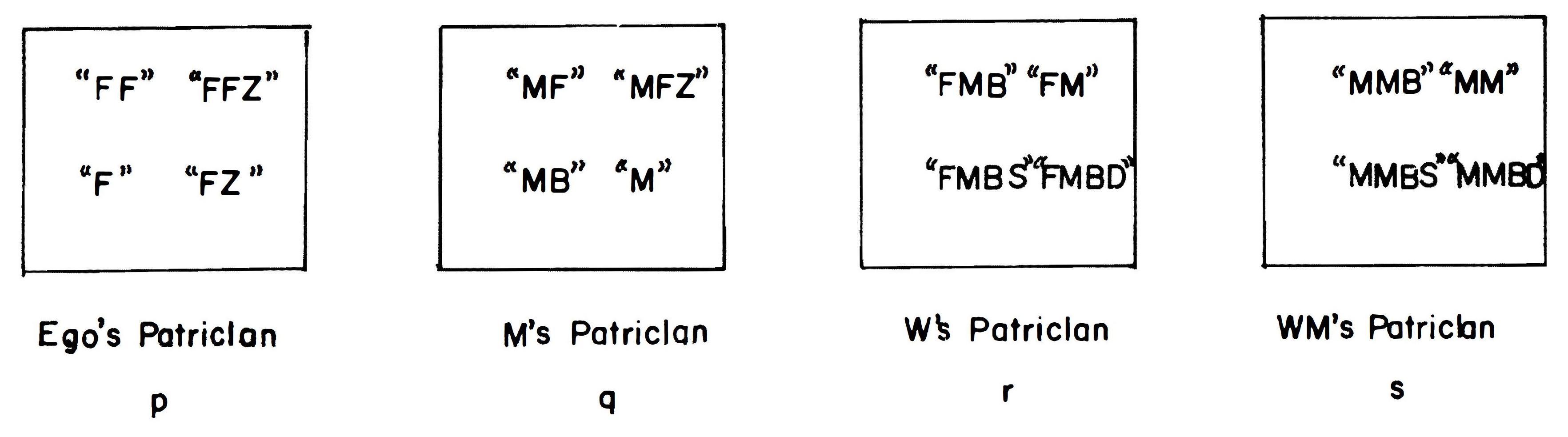

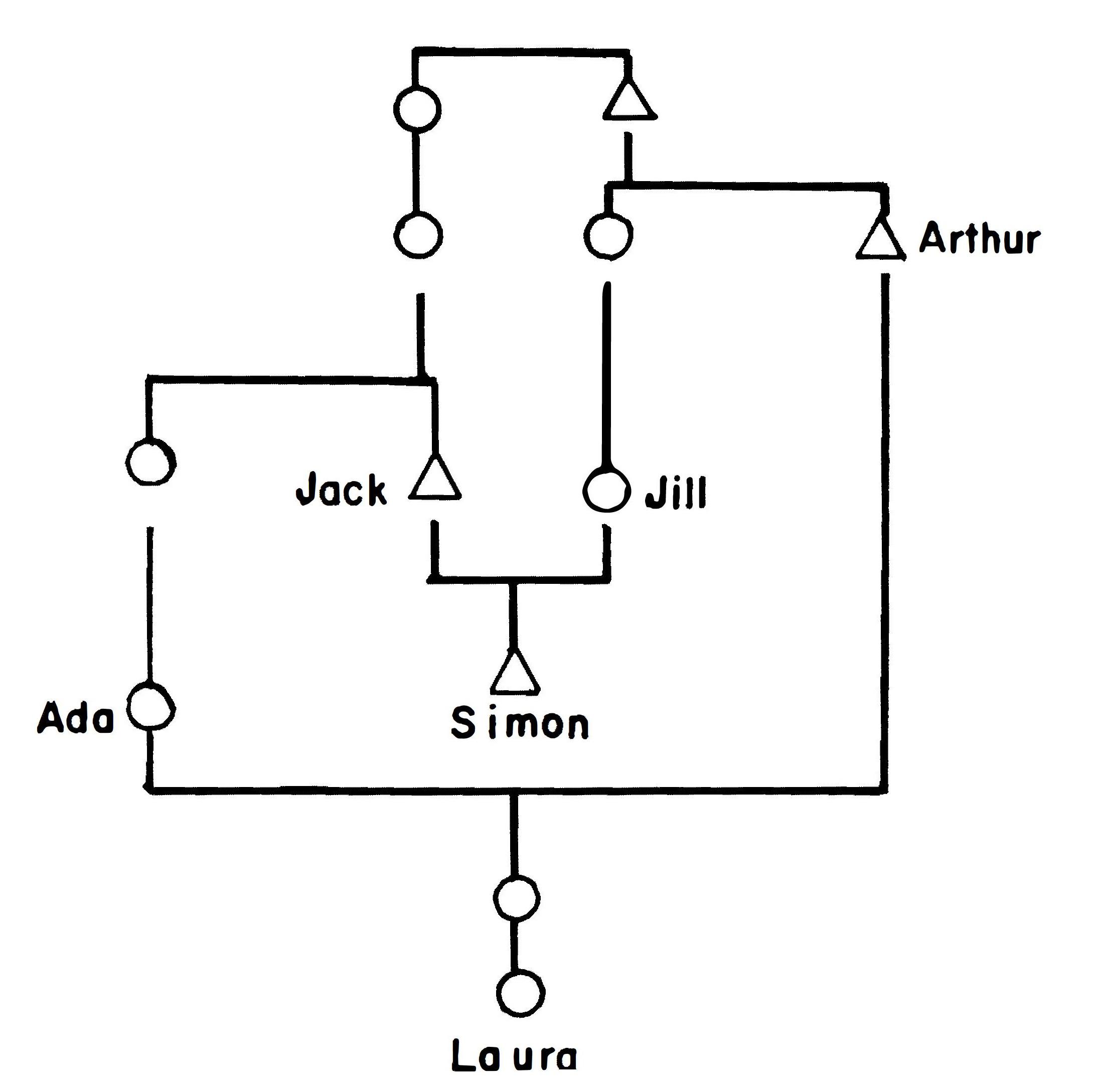

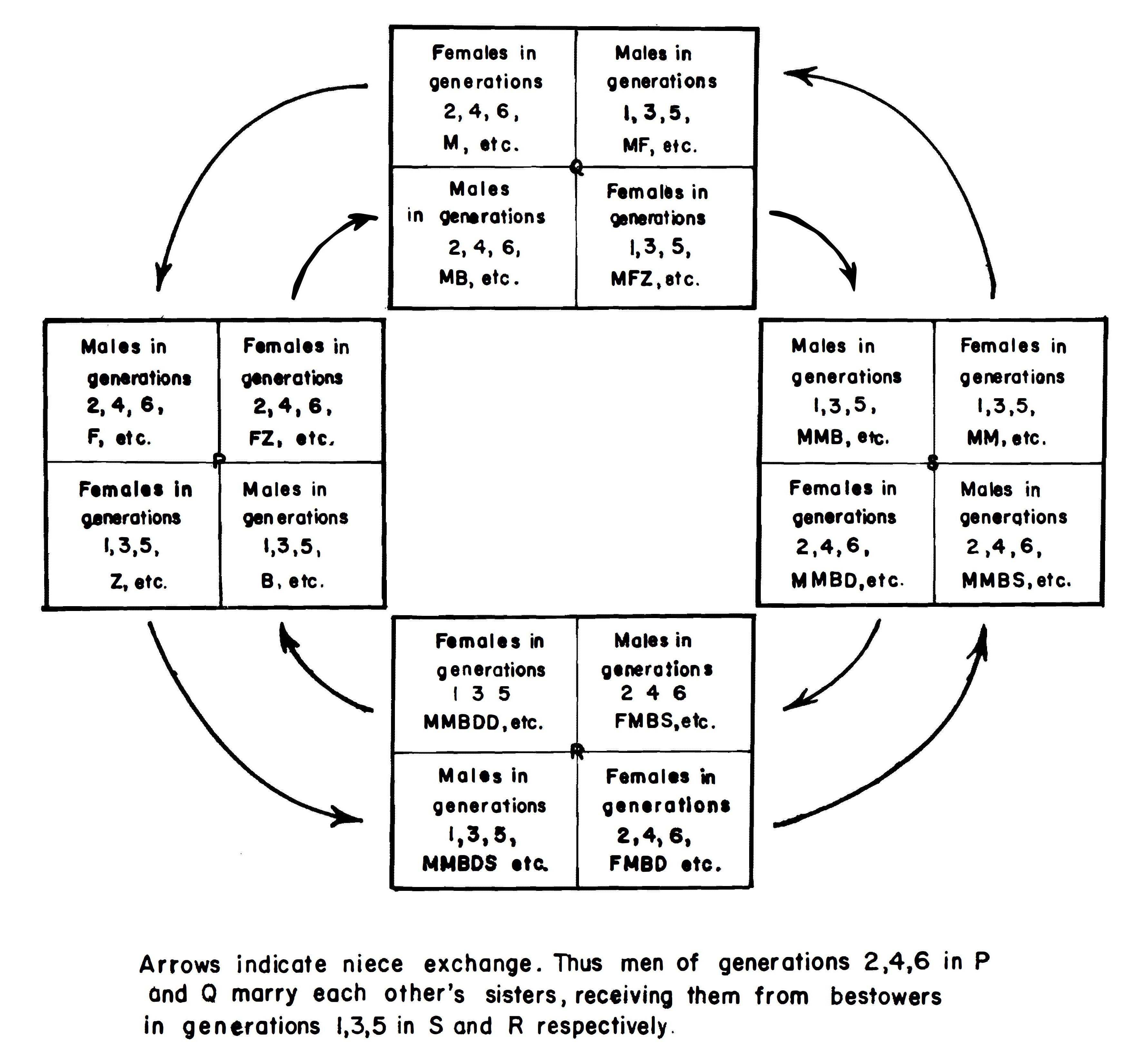

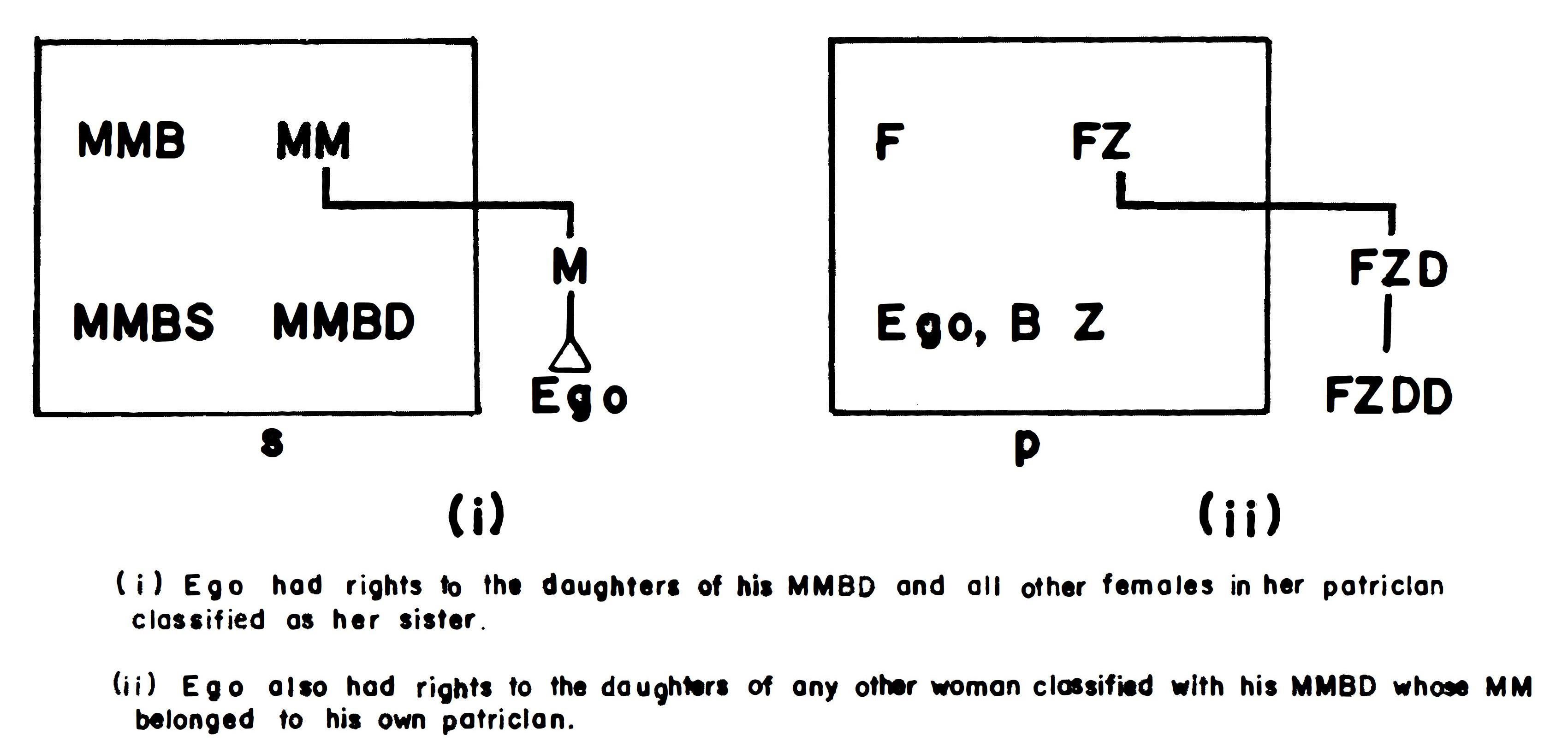

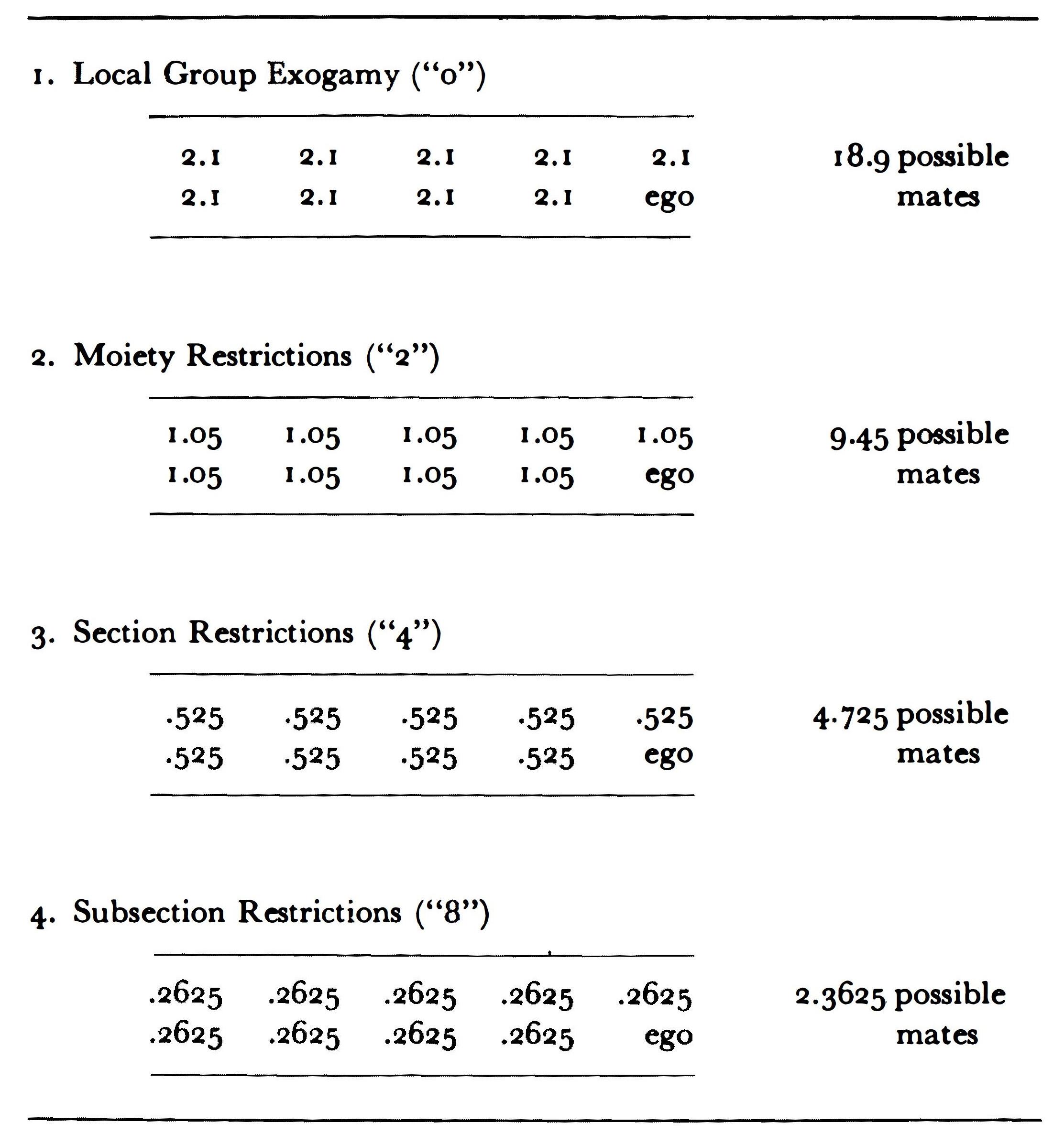

Marriage Arrangements in Australia

The way Australian aborigines marry has held a central place in the anthropological study of kinship. The articulation between kin terms and cross-cousin marriage on the one hand, and moieties, sections and subsections on the other, have provided materials for a number of analysts, including Radcliffe-Brown, Leach, Murdock, Needham, and Levi-Strauss. Since the symposium was concerned with the hunting way of life and not with the study of marriage per se, the several papers on the subject attempted to place Australian marriage and section systems into the general context of hunter-gatherer ecology and demography. Hiatt, for example (Chapter 18) presents a model of the operation of an eight-section systern and then goes on to show that, given the small population of the Gidjingali of Arnhem Land, only a fraction of the marriages can be contracted between the cross-cousins specified by the model. The lack of women of the appropriate kin position makes it necessary for most men to seek a spouse elsewhere. Although over go per cent of the marriages are “morally proper, “ in other words contracted between persons of the correct subsections, the net result is that women do not function as a medium of exchange between descent groups. In his comment (Chapter 22b) Levi-Strauss acknowledges the importance of relating stated norms to demographic variables but he goes on to say that his work in Australian kinship has been “concerned with a different problem: to ascertain what was the meaning of the rules, whether they be applied or not.” He expresses the view that the evidence of a “collapsing Australian tribe” is not sufficient to make us discard the earlier formulations of RadcliffeBrown and others which demonstrated that marriage was indeed regarded by the natives as an exchange of women between descent groups.

Meggitt (Chapter 19) and Yengoyan (Chapter 20) both bring demographic data to bear on the study of section systems, but they arrive at different conclusions. Meggitt notes that a series of fifteen central Australian tribes all exhibit a division into eight subsections, despite the fact that the populations of several of the tribes are less than 200 persons, too small for marriages to be cOEtracted only between the members of appropriate subsections. This fact leads Meggitt to conclude that “among the Australian aborigines, subsections are not necessarily concerned in ...the regulation of marriage” (Chapter 19). Yengoyan argues that subsections do regulate marriage, but only very large tribes can successfully operate an eightsection system. A tribe of 1,100 persons, for example, would have no difficulty in arranging “proper “ marriages since each of the eight divisions would contain about 25 eligible mates. On the other hand, a tribe numbering 200 persons or less would not be able to arrange marriages without considerable deviation from the stated rules and, in fact, few of the small tribes in Yengoyan’s sample exhibited an eightsection organization.

Rose (1960b and Chapter 21) adds a further-demographic variable by demonstrating that among the Australians, men tended to marry women a generation younger than themselves. In combination with polygyny, this practice allows men in their forties and fifties to monopolize the majority of women of marriagable age. The function of this “gerontocracy” as Rose calls it, is to combine the women into effective food-producing units, centered around a male at the peak of his “political” career.

Recent demographic research has added a new dimension to the study of Australian systems. Aboriginal marriage now appears to be more explicable in terms of the economic conditions under which the people actually lived. Yet the basic question raised by Levi-Strauss remains: How are the stated rules of social life articulated into a meaningful whole? It is clear that more work is urgently required in Australia, although we suspect that it may already be too late to establish the relation of ideological forms to the behavior of persons on the ground.

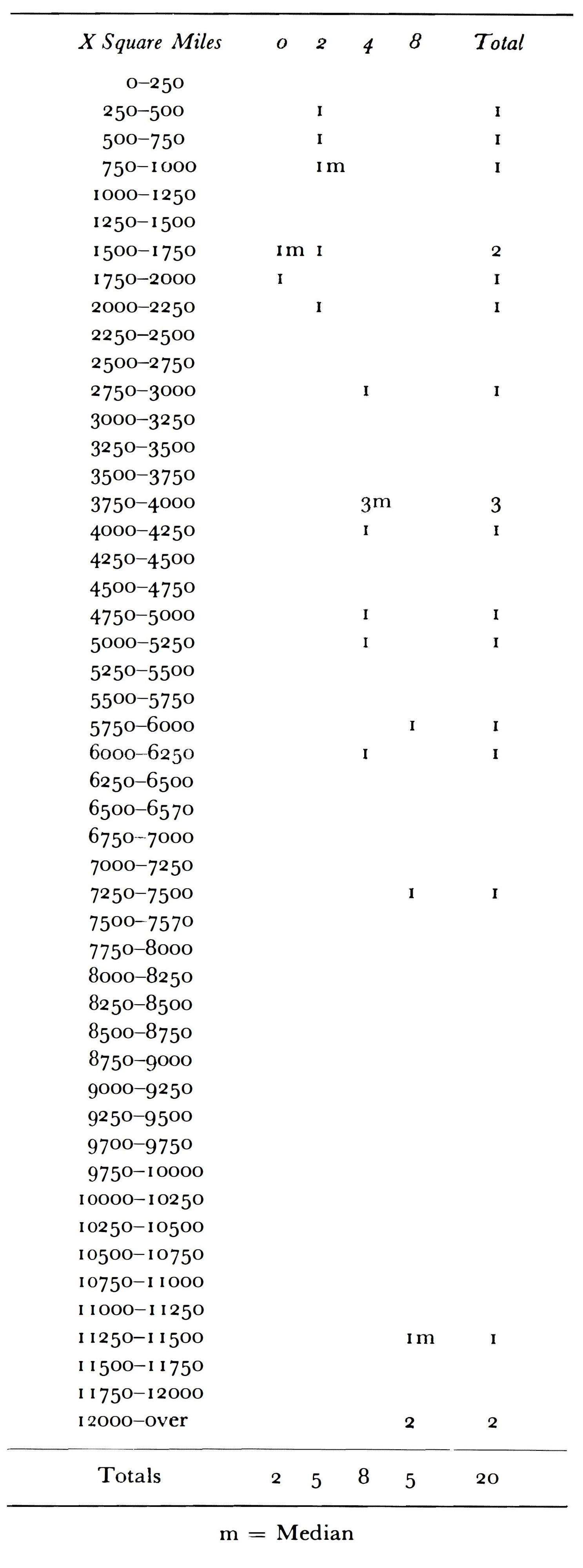

Demography and Population Ecology

Many of the peoples discussed at the symposium live in small-scale societies in which the total population numbers a thousand persons or less. The social and ecological consequences of “smallness” were considered in several papers. Dunn (Chapter 23) made the interesting point that small groups of nomadic peoples living at low population densities would be much more resistant to epidemic diseases than farming peoples who live at higher densities in settled villages. Others speculated on the ideal sizes of hunter local groups and breeding populations, and two figures in particular came to be called the “magic numbers” of huntergatherer demography (Chapter 25C). Birdsell (Chapter 24) cites a figure of 500 as the modal size of tribes in aboriginal Australia; such a population was large enough to insure an adequate recruitment of mates and yet small enough for everyone to know everyone else. There was some evidence that tribes of larger size tended to subdivide into smaller and more manageable units. Twenty-five to fifty persons were the figures most frequently reported for the size of local groups or bands among modern hunter-gatherers, although we failed to arrive at any satisfactory explanation for this central tendency.

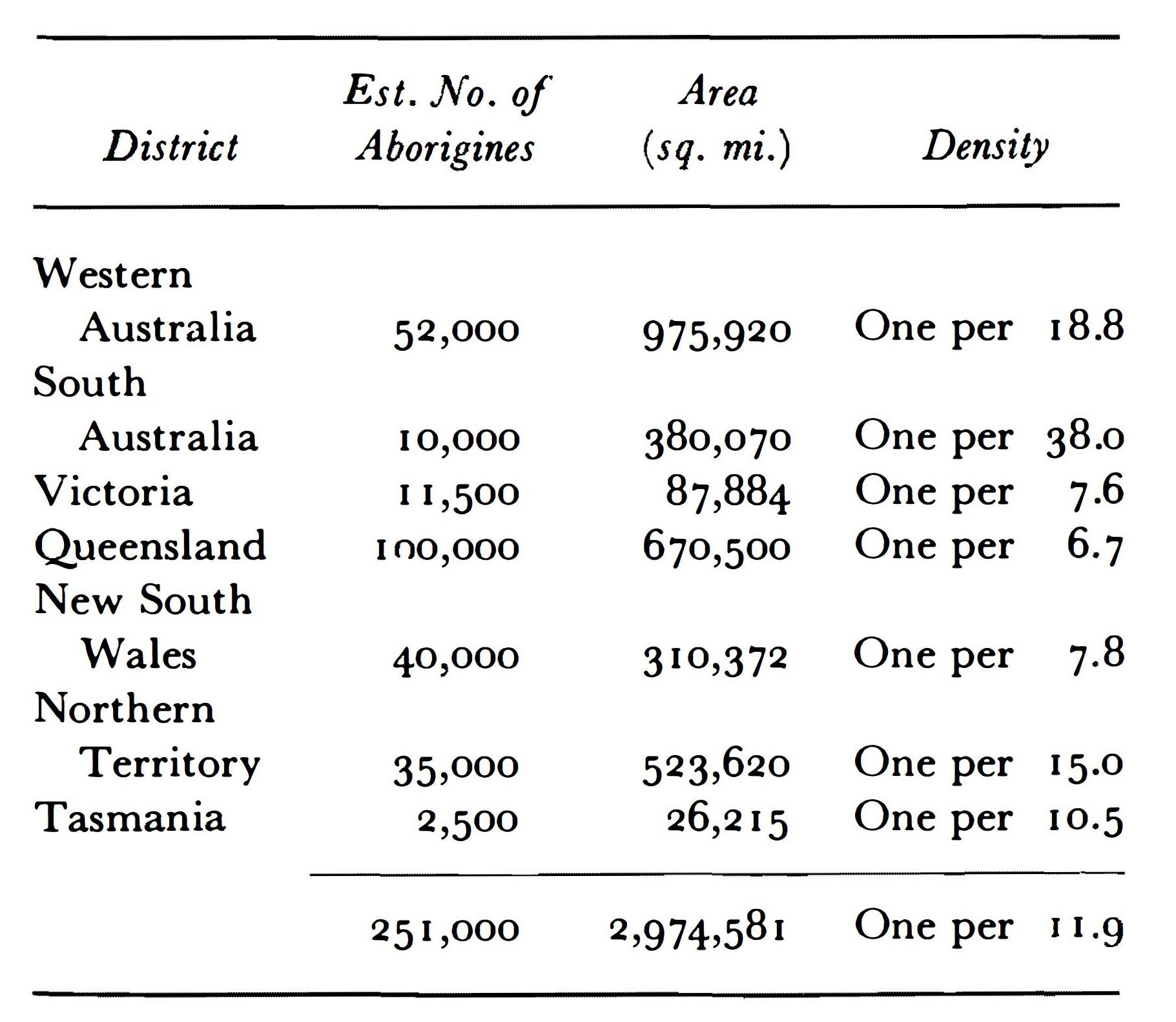

Perhaps the most important demographic issue was the question of what are the factors that keep the populations of hunters in check. Throughout the world hunter densities rarely exceed one person per square mile; most of the accurate figures reported at the conference ranged between one and 25 persons per hundred square miles. We feel that the one-per-square-mile figure is a useful estimate of Pleistocene carrying capacity. It was not until the development of agriculture that human populations were able to break this limit for the first time, while present agricultural densities in most parts of the world exceed the highest hunter densities by a factor of ten to one thousand.

Disease, malnutrition, and infanticide were each considered as possible control mechanisms for hunter-gatherer populations. Since food supply appears to be abundant in modern cases, the constant threat of famine has probably been overestimated as a population control. On the other hand, the management of fertility by means of long lactation, birth control, the killing of twins, and systematic infanticide may have been as frequent in early populations as they are among hunters today. Birdsell and Deevey (Chapters 22b, 22d) went so far as to suggest that a 15–50 per cent incidence of infanticide may have existed throughout the preagricultural history of man.

Helm and Washburn (Chapter 9a) following Bartholomew and Birdsell (1953) suggested that we consider what works in the long run. A population may thrive for several generations and give every appearance of being successfully adapted, Gnly to be cut back severely by an ecological reverse once in a hundred years. Probably the most successful long-term situation is for a population to become stabilized at 20 or 30 per cent of carrying capacity, but at the present it is not possible to determine how such an equilibrium may be achieved. Fortunately, it is still possible to gather the necessary d.emographic data among some of the modern hunter-gatherers, and we hope that these data, plus computer simulation of population models, will yield exceptionally useful results.

“Nomadic Style”: A Trial Formulation

Although the conference on Man the Hunter raised more questions than it answered, there seemed to be a widespread feeling among the participants that a useful beginning had been made in understanding the hunters better. A number of older theories were corrected in light of new data and, where issues were unresolved, we came away at least with a clearer appreciation of our differences, To attempt to draw a general pioture of the hunters at this time would certainly be premature; we would, however, like to offer a trial formulation of our views to serve as a starting point for future research and discussion.

We make two basic assumptions about hunters and gatherers: (i) they live in small groups and (2) they move around a lot. Each local group is associated with a geographical range but these groups do not function as closed social systems. Probably from the very beginning there was communication between groups, including reciprocal visiting and marriage alliances, so that the basic hunting society consisted of a series of local “bands” which were part of a larger breeding and linguistic community. The economic system is based on several core features including a home base or camp, a division of labor—with males hunting and females gathering—and, most important, a pattern of sharing out the collected food resources.

These few broadly defined features provide an organizational base line of the small-scale society from which subsequent developments can be derived. We visualize a social system with the following characteristics. First, if individuals and groups have to move around in order to get food there is an important implication: the amount of personal property has to be kept to a very low level. Constraints on the possession of property also serve to keep wealth differences between individuals to a minimum and we postulate a generally egalitarian system for the hunters.

Second, the nature of the food supply keeps the living groups small, usually under fifty persons. Large concentrations of population would rapidly exhaust the immediate resources, and members would be forced to disperse into smaller foraging units. It is likely, as Mauss observed (1906), that several bands would come together on a seasonal basis, resulting in a division of the year into “public” and “private” periods. Because of the small size of the living groups and the wide variance of family size, bands wax and wane in numbers. It is probably necessary to continually redistribute the population between bands in order to maintain food-gathering units at an effective level.

Third, the local groups as groups do not ordinarily maintain exclusive rights to resources. Variations in food supplyofrom region to region and from year to year create a fluid situation that can best be met by flexible organizations that allow people to move from one area to another. The visiting patterns create intergroup obligations, so that the hosts in one season become the guests in another. We think that reciprocal access to food resources would rank as equal in importance with exchange of spouses as a means of communication between groups. It is likely that food may antedate women as the original medium of exchange (cf. Levi-Strauss, 1949).

Fourth, food surpluses are not a prominent feature of the small-scale society. If inventories of food on hand are minimal, then a fairly constant work effort has to be kept up throughout the year. Since everyone knows where the food is, in effect the environment itself is the storehouse; and since everyone knows the movements of everyone else, there is a lack of concern that food resources will fail or be appropriated by others.

Fifth, frequent visiting between resource areas prevents any one group from becoming too strongly attached to any single area. Ritual sites are commonly associated with specific groups, but the livelihood of the people does not depend on such sites. Further, the lack of impediments in the form of personal and collective property allows a considerable degree of freedom of movement. Individuals and groups can change residence without relinquishing vital interests in land or goods, and when arguments break out it is a simple matter to part company in order to avoid serious conflict. This is not to say that violence is unknown; both homicide and sorcery are found among a number of current hunter-gatherers. The resolution of conflict by fission, however, may help to explain how order can be maintained in a society without superordinate means of social contro!’

At the symposium we presented some of these ideas under the general heading of the “Nomadic Style. “ Several others found this view plausible and suggested ways in which specific cases might have developed out of this baseline. L. Binford noted that northern adaptations required a more elaborate material basis, including fixed facilities such as fish J weirs and game fences, and more substantial dwellings, clothing, and tool kits. Steward pointed out that the development of traction! and water transport would allow northern peoples to own more and yet still retain mobility (Chapter 34). And Suttles (Chapter 6) showed how the fisherman of the Northwest coast may have originally started out in small nomadic bands, but were subsequently led into surplus accumulation, heavy facilities, and ceremonial exchange by the necessity to bank against vagaries in salmon supply.

It seems clear that when the means of production come to depend upon the exclusive control of resources and facilities, then the loose non-corporate nature of the small-scale society cannot be maintained. If this view is: correct, then a major trend in human affairs has been the transformations of social relations as advanced technologies and formal institutions have come to play a more and more dominant role in the human adaptation. The institutions of property, of clan organizado^ of government, and of the state did not spring full-blown in a divine creation. The study of the hunters may help to understand how these things came into being.

2. The Current Status of the World’s Hunting and Gathering Peoples

George Peter Murdock

Ten thousand years ago the entire population of the earth subsisted by hunting and gathering, as their ancestors had done since the dawn of culture. By the time of Christ, eight thousand years later, tillers and herders had ^ replaced them over at least half of the earth.

At the time of the discovery of the New World, only perhaps 15 per cent of the earth’s surface was still occupied by hunters and gatherers, and this area has continued to decline at a progressive rate until the present day, when only a few isolated pockets survive.

Many of the peoples who subsisted by hunting and gathering at the time of Columbus have disappeared entirely and been replaced by stronger peoples. Others have been reduced to dependency-on reservations or as servants or outcaste groups. Still others have made a transition, in some form or other, to modes of subsistence based on agriculture, animal husbandry, or industrial employment. Only a handful still live an independent life of hunting and gathering, nearly all of them under markedly altered conditions. It is time-in-deed, long past time-that we took stock of these dwindling remnants, for it is only among them that we can still study at first hand the modes of life and types of cultural adjustments that prevailed throughout most of human history.

In this paper I shall attempt to enumerate and briefly characterize the regions of the world where peoples with hunting and gathering economies survived long enough to be studied by modern ethnographers, with special reference to those groups amongst whom fundamental field research may still be possible.

The definition of hunting and gathering economies was the subject of considerable discussion at the symposium. For the sake of simplicity in presentation, I shall adopt a strict definition and merely allude here, by way of introduction, to three marginal subsistence categories which some would include with hunting and gathering and others would differentiate.

Mounted Hunters

Several groups of peoples who subsist primarily by hunting depend largely on domestic animals which they ride in pursuing or surrounding their game. Notable among them are the North American Indians of the Plains and the adjacent sections of the Plateau and Great Basin and the South American Indians of Patagonia and the adjacent Gran Chaco, both of which groups hunted with horses during the period of their ethnographic description. Comparable to them are several hunting peoples in Mauritania, including the Nemadi described by Gabus (1951–52), who employ camels in the chase. Mounted hunters approximate pastoral nomads in a number of respects, the chief difference, perhaps, being the fact that their domestic animals do not provide a majot part of their food supply.

Sedentary Fishermen

Various other peoples who lack both agriculture and large domestic animals depend not so much on hunting and gathering as on fishing, shellfishing, or the pursuit of aquatic animals. Where they lead an essentially nomadic mode of life, I classify them with hunters and gatherers. Sometimes, however, their marine food supply is so plentiful and stable that they have been able to adopt an exclusively or predominantly sedentary mode of life. Such conditions offer the possibility of attaining a considerable degree of cultural complexity otherwise achievable only with intensive agriculture. The Indians of the North Pacific coast, for example, seem to me to fall well beyond the range of cultural variation of any known hunting and gathering people. The Calusa, a sedentary fishing people of southern Florida, as Goggin and Sturtevant (1964) have shown, had even elaborated a political system with fairly sizable states. Along the Niger and Congo rivers in Africa, numerous societies which subsist primarily by fishing and trade have cultures in no way inferior in complexity to those of their agricultural neighbors. In northeastern Asia the Ainu, Maritime Chukchee, Gilyak, Kamchadal or Italmen, and Maritime Koryak possibly, though less certainly, fall into the same category.

Incipient Tillers

Not a few peoples, especially though not exclusively in lowland South America, practice agriculture but obtain more of their food supply from hunting, fishing, and gathering and show a clear preference for hunting over tillage. Several participants in the symposium, notably Crocker with reference to the Ge, characterized such incipient agriculturists as having a hunting-gathering ideology. While I freely grant their point, I have preferred to exclude such groups from my survey. After all, I know many American farmers who till the soil for a living but derive considerably more personal gratification from their subsidiary hunting and fishing activities.

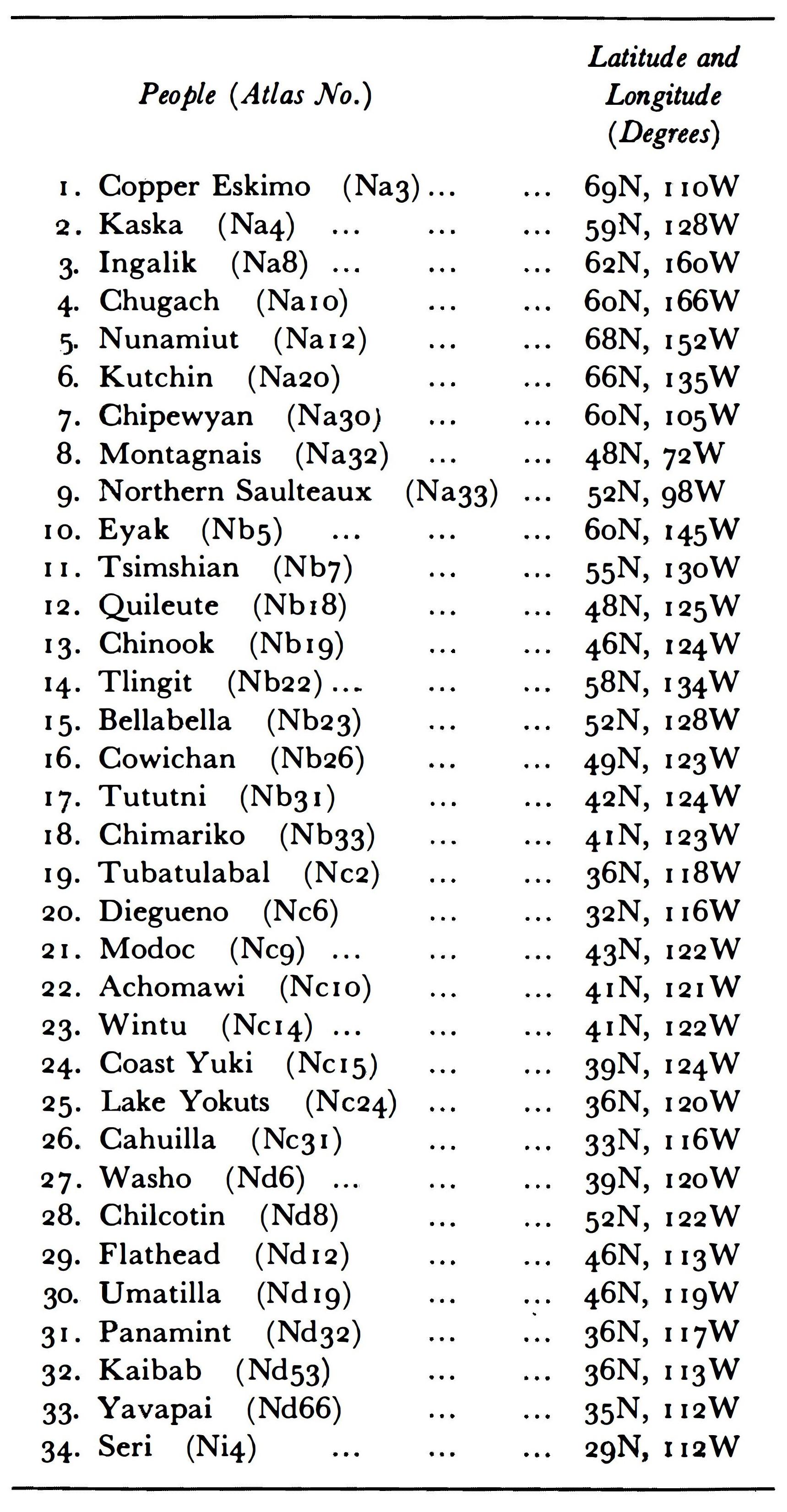

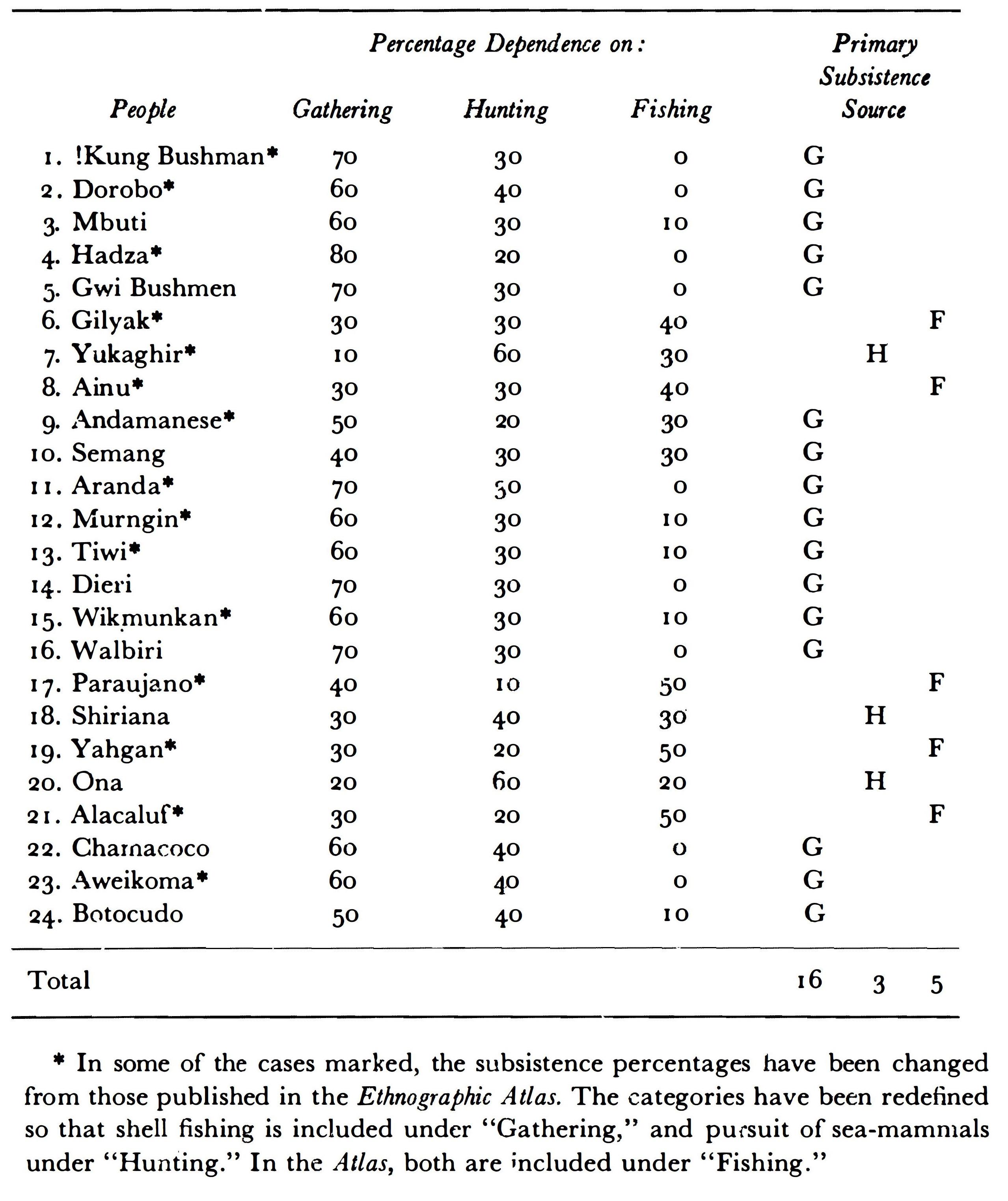

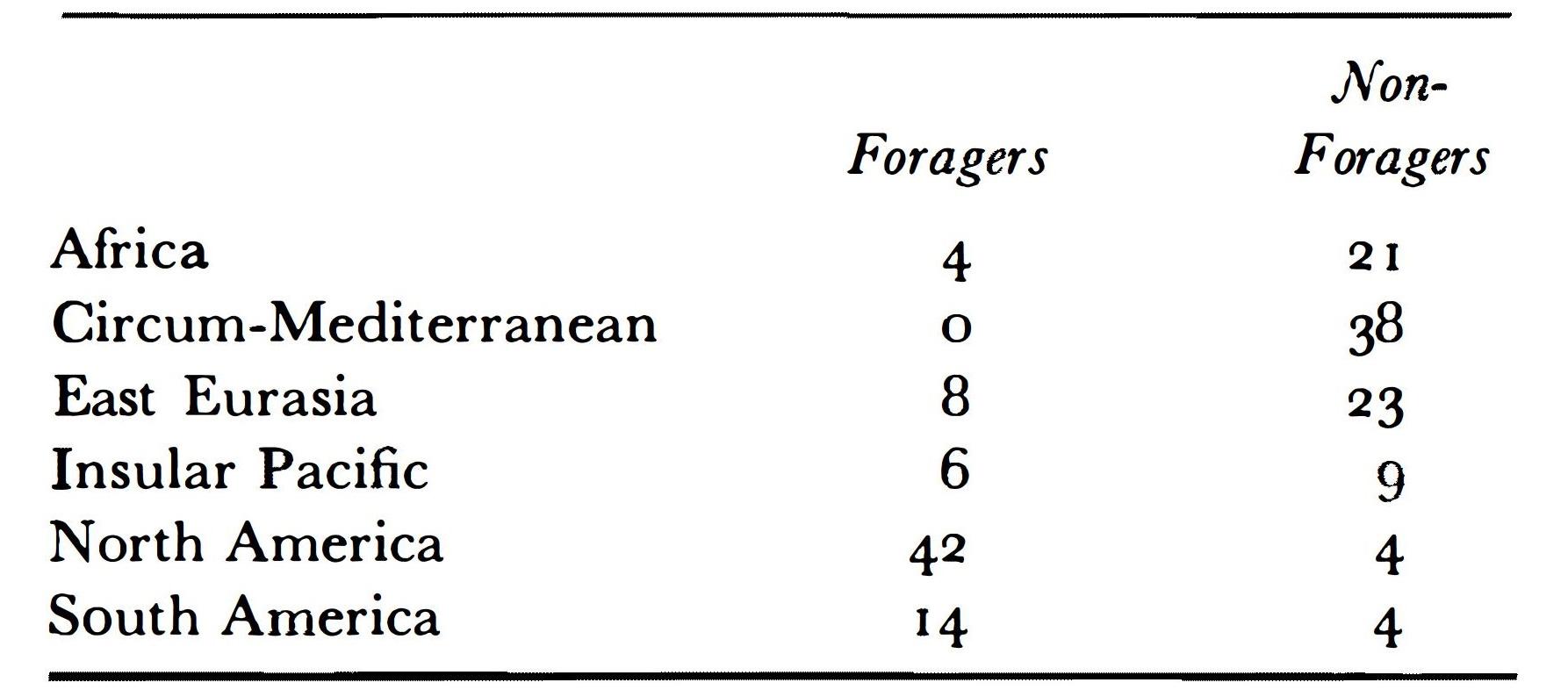

In the listing of hunting and gathering peoples below, consequently, I omit all groups which I would categorize as mounted hunters, sedentary fishermen, or incipient tillers. I gratefully acknowledge the many suggestions made by participants in the symposium which have enabled me substantially to amplify and revise the original draft of this paper. Twenty-seven surviving groups of hunter-gatherers are enumerated in this survey. The geographical distribution of these peoples is plotted in Figure I.

Africa

-

Bushmen

I shall begin my enumeration with the Bushmen of south and southwest Africa, of whom about 45,000 are reported to survive today (Tobias, 1956; Silberbauer, 1965). The vast majority of these, however, are attached to the Tswana as serfs or to Europeans as servants or laborers and have undergone intensive acculturation. Nevertheless, about 5,000 of them still pursue essentially their aboriginal nomadic mode of life. Lorna Marshall (1957, 1959, 1960), in particular, has demonstrated that field work of the highest quality is still possible among them. They are dealt with in greater detail by Richard B. Lee (Chapter 4, this volume).

-

Koroca

On the desert coast and adjacent foothills of southwestern Angola live the Koroca and the related Kwepe and Kwise, who practice no agriculture. From very fragmentary reports, they appear to resemble the Bushmen in culture and the Bergdama in physique (Almeida, 1965). Remarks by Jorge Dias suggest that they merit more intensive study.

Desmond Clark believes that there may also be Bantu hunting tribes in the same general area.

-

Pygmies

About 170,000 Pygmies are reported to survive in the tropical forest region of central Africa, nearly all in a dependent symbiotic relationship with the neighhoring Negro tribes. The majority, especially those in Rwanda, Burundi, and the central portion of the Republic of the Congo, have either adopted agriculture or otherwise become strongly acculturated. In the Ituri Forest region of the northeast, however, the Aka, Efe, and Mbuti groups still preserve large portions of their indigenous culture. For the Mbuti, in particular, we have a substantial monograph by Schebesta (1938–50) and the more intimate and revealing studies by Turnbull (1961, 1965b). There is certainly room for further field work here, and probably also among the inadequately described Pygmies of Cameroon and Gabon.

-

East African Hunters

Until very recently, available information on the surviving hunting populations of east Africa has been exceedingly scanty. Now, however, we have a series of substantial accounts of the Dorobo from Huntingford (1951, 1954, 1955) and the still more recent field work among the Hadza or Kindiga by James Woodburn (Chapters 5, 3, this volume). The Teuso or Ik described by Colin Turnbull, though possibly related to the Dorobo, are not a hunting people in the strict sense adopted here. It is doubtless too late to expect new information on the Asa or Aramanic beyond the scraps contained in Merker(1904),but it still maybe possible to conduct rewarding field work among the Ariangulo, the Boni, or the Sanye.

-

Ethiopian Hunters

William Shack reminded the symposium that there are half a dozen groups of hunters and gatherers in central Ethiopia, extending from the lakes of the Rift valley on the east to the edge of the plateau in the west. He called particular attention to the Fuga, whom he found still flourishing in the Gurage country. I omitted these peoples in my original survey because, from the scanty references available to me, they seemed more like despised outcaste groups than independent tribes. If they do in fact lead independent lives, they certainly deserve early and intensive study.

East Asia

-

Siberian Hunters

The non-agricultural peoples of Siberia have long since been largely converted to a pastoral mode of life in the interior or, on the coast, have come to depend primarily upon fishing and have adopted a relatively sedentary settlement pattern. The only two Siberian peoples who seem to meet our strict definition of hunters and gatherers are the Ket or Yenisei Ostyak, on whom wehave a briefsketch byShimkin (1940), and the Yukaghir, on whom we have a full monograph by Jochelseon (1926). Both tribes have doubtless been so altered by Soviet acculturation policies that further field work among them is unlikely to yield rewarding results.

-

Indian Hunters

There are in India a number of hunting societies, mostly dependent and often approximating the status of specialized castes. The fullest ethnographic account is probably that by Furer-Haimendorf (1943) on the Dravidianspeaking Chenchu, but Majumdar (1944) has contributed a brief account of the Korwa of Uttar Pradesh. B. J. Williams describes the Munda-speaking Birhor in this symposium (Chapter 14), and there is fragmentary information on the Irula and Kurumba of the Nilgiri Hills. Peter Gardner has provided me with a list of additional Indian hunting groups: the Kadar, Malapandaram, Paliyan, and Yanadi, all of whom have been studied, and the still undescribed Allar, Aranadan, Eravallar, Mala Vedan, and Vettuvan.

-

Veddoid Hunters

It is almost certain that no further ethnographic information of consequence is obtainable from the Rock Yedda of Ceylon, who had already practically disappeared when the Seligmans (Igl I) made their classic study. I agree with Gardner that the Yedda are probably a case of “devolution. “ The Senoi or Sakai of Malaya, according to a personal communication from Robert Dentan on the basis of his recent field work among them, have everywhere adopted a substantial dependence upon agriculture. I have no recent information on the peoples of Indonesia who have been called Veddoid, very probably incorrectly, and who have been reported to practice very little agriculture, such as the Kubu of Sumatra (Hagen, Ig08; Schebesta, Ig28) and the Punan of Borneo (Furness, Ig02; Hose and McDougall, Igl I; Roth, 18g6).

9. Southeast Asian Hunters

Participants at the symposium have called my attention to several hunting and gathering peoples in Southeast Asia of whom I had previously been unaware. Thus Georges Condominias cites the Ruc of central Vietnam, Peter Gardner the Penang and Phi Tong Luang, and Lauriston Sharp the Mrabri or Yumbri of northern Thailand. The References at the end of this volume include the following supplied by Sharp on the Mrabri: Bodes (lg63), Flatz (lg63, 1964), Kraisri and Hartland-Swann (1962), Velder (1963, 1964).

10. Negritos

Most of the Negrito tribes of the Philippines practice at least a modicum of agriculture and thus fall outside the range of our discussion. We do, however, possess substantial accounts of two non-agricultural Negrito groups—the Andamanese by Man (1883) and RadcliffeBrown (1933) and the Semang of Malaya by Evans (1937) and Schebesta (1929). I suspect that further field work may still be possible among both of them.

Oceania

11. Australian Aborigines