Richard Joseph

WANTED: Paying Guests To Trace the Lost Cities of Peru,

Locate Gold and Jewels, Hunt, Fish, Skin Dive. Must Like Incas.

Are you tired of shooting Hons on Kilimanjaro? Bored with the business of a tiger shikar in Bengal? Does the suggestion of hunting polar bears on Aleutian icebergs sound a bit chilly, and the idea of searching for Nepal’s Abominable Snowman leave you cold? Then, sated voyager, you might be interested in one of the last great travel adventures left on an overpopulated globe.

How are you grabbed by the prospect of finding lost Inca cities in the high jungles of Peru, or seeking out the golden treasures of El Dorado? This was the fabled land that drove the frustrated conquistadores mad. the place where the Gilded Man supposedly used gold dust as talcum after swims in mountain lakes. Rumor had it sited all over South America, but the Spaniards never were able to track it down. Could be that you might, as a paying participant on an aerial safari organized by the Andean Explorers Club. On file at club headquarters in a Lima hotel are scores of reports of forgotten Inca and pre-Inca temples and cities and potentially treasure-laden lakes that have filtered in from jungle Indians. Many have been authenticated by obscure sixteenth-century Spanish chronicles, found mostly in Augustinian monasteries scattered around the country. Lacking funds to follow them up. the club sets up share-the-expense expeditions—and that’s where you might come in.

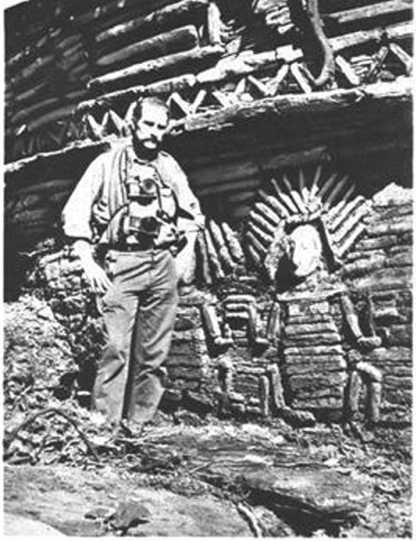

Prime mover of the Andean Explorers Club is its President and Chief Explorer—that's his title—Gene Savoy, a forty-year-old, long-maned and drooping-reddish-moustached American who looks like General Custer or a young Buffalo Bill. Savoy, who describes himself as an archaeological explorer, writer and photographer, has spent the past ten years roaming the expanses of Peru’s Andean and Amazonian wilderness.

“I find the sites mainly by tracing old Inca and pre-Inca highways from the air,” Savoy says. “On the ground, we explore the site and clear away enough of the underbrush to see what we have, and then move out. leaving the actual digging to the scientists.

“The expeditions certainly aren't commercial tours; club members contribute their time, and our guests split only the actual cost. This can run anywhere from fifteen-hundred dollars per person up. depending on where we go. how we get there, how long we stay, and the number of people in the party. And we’re not looking for passive sightseers: we want people who are seriously interested in exploration and archaeology and will take an active part in planning an expedition and carrying on its work. Who knows, they might help us find another Machu Picchu.”

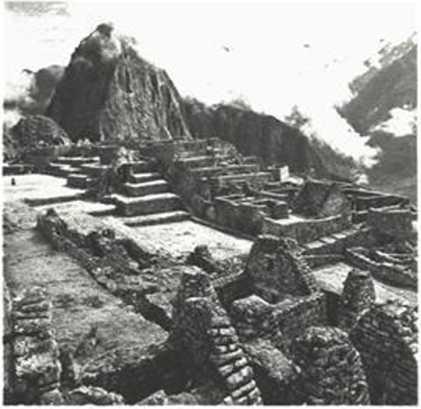

Savoy himself has already done better than that. Three years ago he caused an archaeological furor with his exploration of Vilcabamba, the lost capital of the Incas—which is what Hiram Bingham thought Machu Picchu was when he discovered it in 1911, but it wasn’t. Bingham, the young Yale archaeologist who later became Connecticut’s Governor and Senator, did reach the ruins of Vilca-bamba. and he wrote about it in his Lost City of the Incas, but his native carriers were frightened off by the spears and arrows of primitive Indians living in the area, and he was forced to move out without realizing the extent of his discovery.

Savoy had been prowling the Andean wilds for six years when he joined forces in 1963 with Antonio Santander Cascelli, a sixty-two-year-old Peruvian explorer who also was convinced that Bingham's Machu Picchu was not Vilcabamba. to try to find the lost capital. After many months of preparation, their expedition reached the Plain of the Spirits by muleback. Local Indians at first refused to guide them, remembering tribal legends which said that the gods would kill anyone disclosing the location of the city. They finally agreed, though, and after a three-day jungle march the party reached the first moss-covered ruins.

Two weeks of exploration uncovered indications that Spaniards who had deserted had joined the Indians in their mountain redoubt. Two rooms of the Inca palace were connected by a Spanish-style doorway, and Spanish tiles and a Spanish horseshoe were also found in the ruins.

Meanwhile their Indians were growing as jumpy as Bingham’s guides had been when their fears had forced him to leave the area. One by one they started drifting away. Savoy and Santander stayed on the site, despite the desertions, until Savoy was hurt dodging a falling tree, and they decided to pull out while they still were able to.

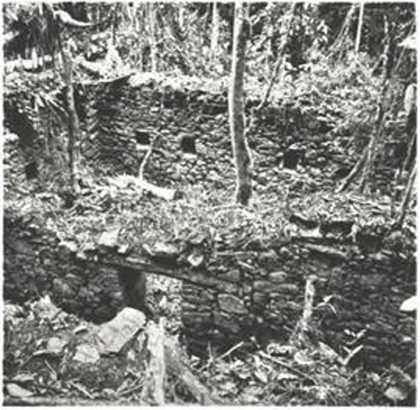

On Savoy’s first and two succeeding expeditions to Vilcabamba. he explored about five hundred acres of the forbidding Plain of the Spirits, uncovering a luxurious palace and sixteen separate communities of granite and limestone houses, fountains, courtyards and terraces once occupied by Inca nobles, surrounded by the lesser dwellings of their followers. All had been covered by the jungle. Great trees had clamped their roots around the walls and over the terraces, and their branches were interlaced by vines as thick and strong as telephone cables. Orchids grew from the vines and the trees, white-faced monkeys ruled their matted green kingdom, and the whole scene looked as Angkor, the lost capital of the Khmer Empire in Cambodia, must have looked when it was uncovered by French explorers more than a century ago. The ruins of Vilcabamba stretch out over three plateaus ranging from about forty-five hundred feet to twelve or thirteen thousand feet high. Savoy has been able to explore only the first plateau so far. but it alone is four times the size of spectacular Machu Picchu.

Chronicles of Spanish explorers described Vilcabamba as the last great capital of the Incas, supposedly situated somewhere in the Andes of southern Peru. It was to this Inca Berchtesgaden that four thousand Indians retreated before the conquering Spaniards, building huge palaces and temples and a military base from which they forayed against the conquistadores for almost forty years. The Spaniards killed the last Inca chieftain in 1572. and after that his followers evidently left their city to the jungle.

The same early Spanish records that clued Savoy onto Vilca-bamba also led to three expeditions to what he believes to be the El Dorado region of the Peruvian Amazon jungle. History tells how Francisco Pizarro and his conquistadores. not the most gentle of souls, captured the Inca Atahualpa. held him for ransom, then butchered him when enough loot had come in. But more Inca treasure was supposed to have been on the way at the time of the murder.

"Only a small part of the Inca gold and jewels were ever recovered." Savoy says, "and I have reason to believe that the Indians threw the rest of it into lakes and caves rather than have it fall into the hands of the Spaniards. On previous expeditions I found lakes that weren’t on any maps, and uncharted walled-up tunnels. If we get some skin divers to go along with us on future trips, 1 think they might be able to come up with something.

"Anything we find, though, will be turned over to the Peruvian government, to be put into the museums. The Spaniards melted down the Inca jewels and altarpieces, so we have no idea what they looked like. Certainly their historical and archaeological value will be much greater than any monetary worth.”

Savoy hopes that his paying expeditioners will finance return trips to Vilcabamba or El Dorado, but he’s also ready to take them to likely sites for new discoveries, or to other areas he has already discovered and/or explored. These include Gran Pajaten, the remnant of a lost pre-Inca civilization in the eastern Andes; Monte Peru via and Muyoc Viejo, believed to have been built by the Chacha-poyas. a race of fair-skinned warriors which the Incas conquered only after an extremely long war; and Pueblo de los Muertos (village of the dead), a cliff dwelling of human figures in the Amazon country.

Participating guests on previous trips organized by Savoy and the Andean Explorers Club have included archaeologists, naturalists, engineers, newspapermen and a task force from the BBC. Working with him on the aerial safaris is Gonzalo Del Solar, a forty-five-year-old Peruvian charter-flight operator, helicopter pilot and local representative for Cessna planes and Bell helicopters. The optimum number of participants on an expedition is six or seven, according to Savoy; these include himself, and another member of the Andean Explorers Club to hire Indian guides, carriers, machete men and muleteers, set up camp in advance of the main party and act as Field Chief: four or five expense-sharing guests; and an Explorers Club photographer, if the guests want a still or movie record of the expedition. And most of the guests seem to want this kind of remembrance.

Intending guests write to Savoy at club headquarters in the Hotel Savoy (no relation) in Lima, giving him an idea of who they are. what they’re interested in, when they want to come to Peru, and how much time they can spend in the field. Savoy then suggests itineraries and dates and estimates the cost. He needs a lead time of at least a month to set up arrangements, and prefers a couple of months between the setting of the schedule and the actual takeoff from Lima.

“We’ll take visitors out to explored sites on trips as short as three days to a week, but we need at least a month for any sort of exploration.” Savoy says. "We supply all field and camping equipment and tailor our trips to fit the interests of our guests. They can fish in virgin streams and lakes for varieties of fish that haven’t even been classified yet, and shoot wild turkey. Andean bear. puma, deer and all sorts of local game. But we don’t encourage jaguar hunting: we haven’t lost a guest yet. and we don’t want to.”

Guests arrive in Lima about a week before takeoff. Long before then the Field Chief has left to set up camp, check airstrips and clear helipads. During the Lima stopover, guests are taught rudimentary Spanish, if they don’t already have some command of the language, and briefed on how to treat the natives, the weather and health conditions they’re likely to encounter in the high jungle (most of the archaeological sites lie between four thousand and nine thousand feet high), and the handling of a machete. The final plans for the expedition are set and jobs in the field are assigned at this time.

Because of the amount of equipment carried, the expeditions usually leave Lima on one of Del Solar’s charter planes rather than on commercial aircraft. The group changes to small planes or helicopters at Trujillo for sorties into the north country, at Cuzco for the eastern Andes, or at Iquitos for the Amazon area. On an expedition to Vilcabamba, the party would fly helicopters a hundred fifty miles northwest out of Cuzco, over the L’rubamba River gorge and Machu Picchu, to a jungle clearing about a day’s march from the ruins.

The Explorers Club will also arrange desert safaris to fly over ancient Indian roads and land at abandoned adobe cities and surrounding fortresses, some of them with eighteen-foot-high wails several city blocks long.

Savoy’s favorite project right now. though, is a twenty-five-hundred-mile cruise from Trujillo up the Pacific to the west coast of Central America and Mexico in a forty-foot-Jong reed sailboat similar to those used by the Indians on I-ake Titicaca. The trip would be made against prevailing winds and currents, but Savoy's explorations have led him to believe that there were important connections between the Inca and Maya civilizations. He also points to similarities between the legends of Viracocha. an Inca god who drifted away on a raft, and that of the Mexican god Quetzalcoatl.

He has lined up a Peruvian radio operator and a cameraman for a trip he's planning for sometime next year, and right now he’s seeking a backer and an experienced navigator who knows the west coasts of South and Central America—preferably the same man.

“We’ll try to make the whole voyage in ninety days—after that the reed boat sinks.” Savoy says. “If we make it. fine—if not . . . well, anyway, we’ll make headlines’”