Richard P. Werbner

Regional Cults

Association of Social Anthropologists: A Series of Monographs

Turner’s Exclusive and Inclusive Domains

Elitist versus Egalitarian Regional Cults

Hierarchy and the Waxing and Waning of Cults

Part One: Islamic Cult Regions: Historical Interaction or Symbolic Congruence

1. Ideological Change and Regional Cults: Maraboutism and Ties of “Closeness” in Western Morocco

Ideologies and the Social Order

Maraboutism as a Part-Ideology

2. Communal and Individual Pilgrimage: The Region of Saints’ Tombs in South Sinai

Introduction: The Region and the Wider Universe in the Cult

Three Tribes and their Setting in the Peninsula

‘Tribal Organization’ as Ideology

Annual Migration and Pilgrimage

The Symbolism of Saints’ Tombs

Part Two: Regional and Non-Regional Alternatives: The Waxing and Waning of Cults

3. Disparate Regional Cults and a Unitary Ritual Field in Zimbabwe

Introduction: The Interpenetration of Cults

Lineal and Territorial Aspects of a Regional Cult

Expansion and the Regional Medium

The Linking of Local and Territorial Cults

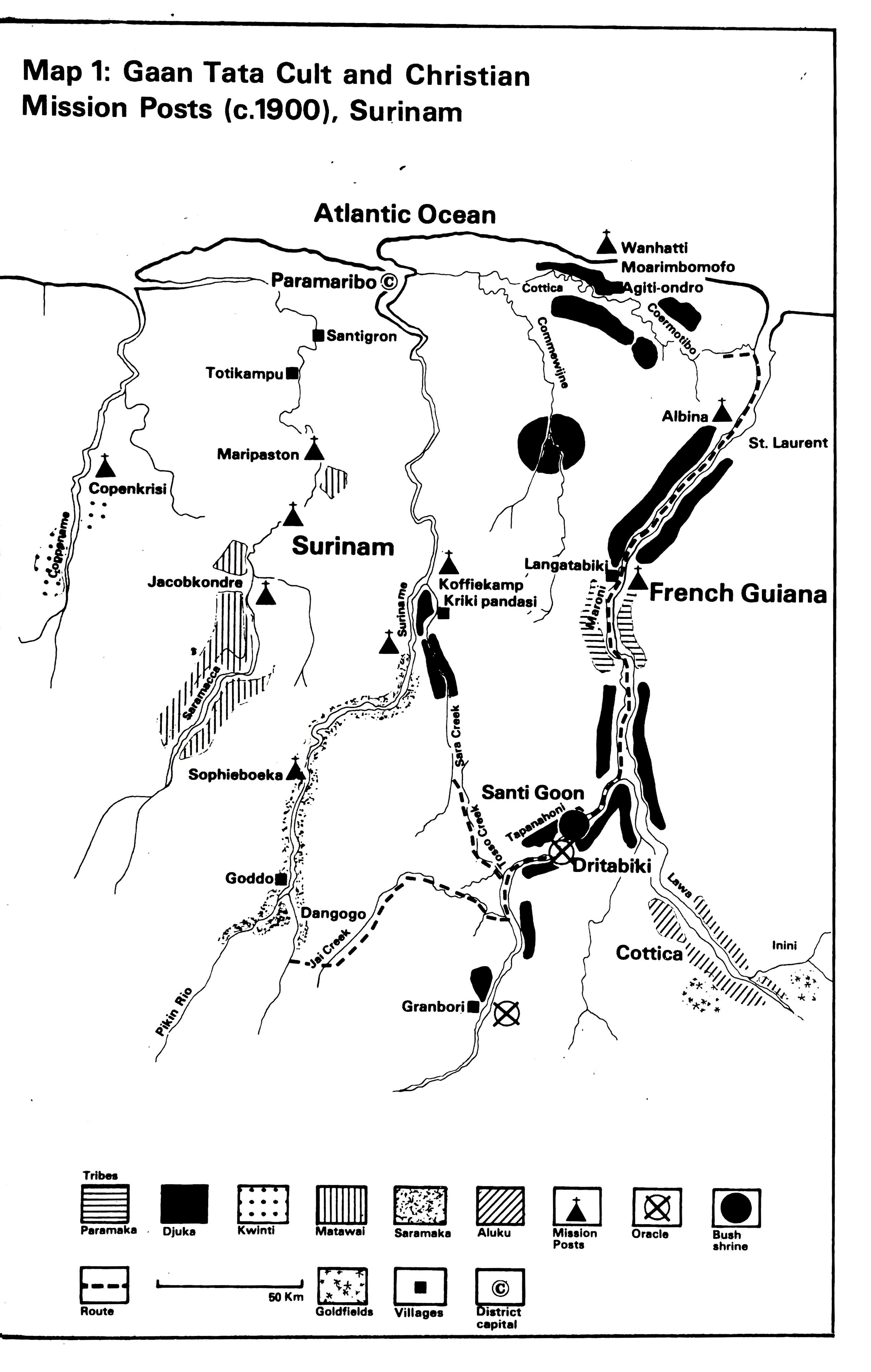

4. Bush Negro Regional Cults: A Materialist Explanation

Introduction: Radical Economic Change and Cults

The spread of a regional cult and its centralization

Allocation of resources and internal distribution

Gaan Tata’s Bulwark on the Tapanahoni

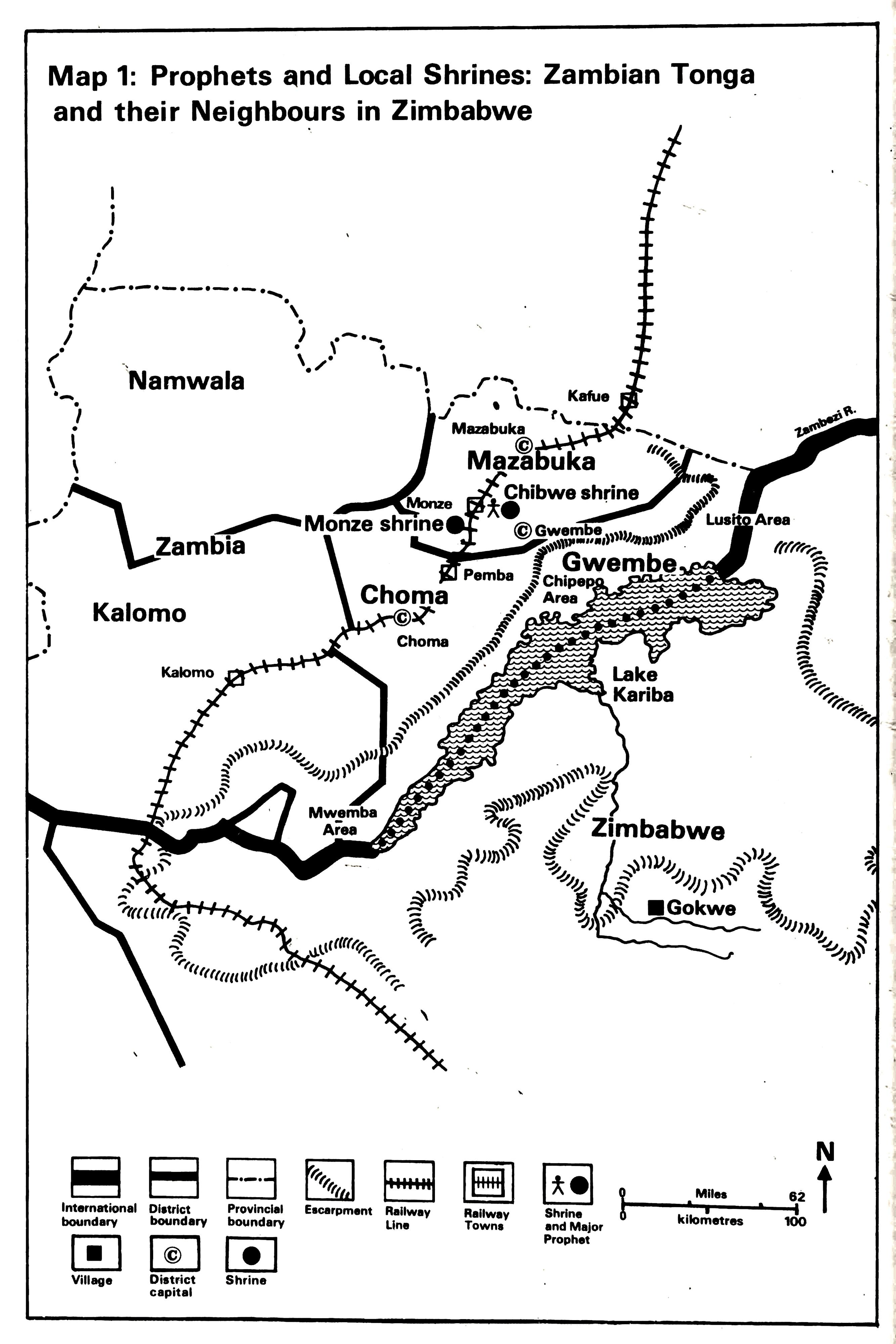

5. A Continuing Dialogue: Prophets and Local Shrines among the Tonga of Zambia by Elizabeth Colson

Prophets and the Greater Community

The Diversification of Society

Continuity and Change in the Cults

The Gwembe Resettlement: A Test Case

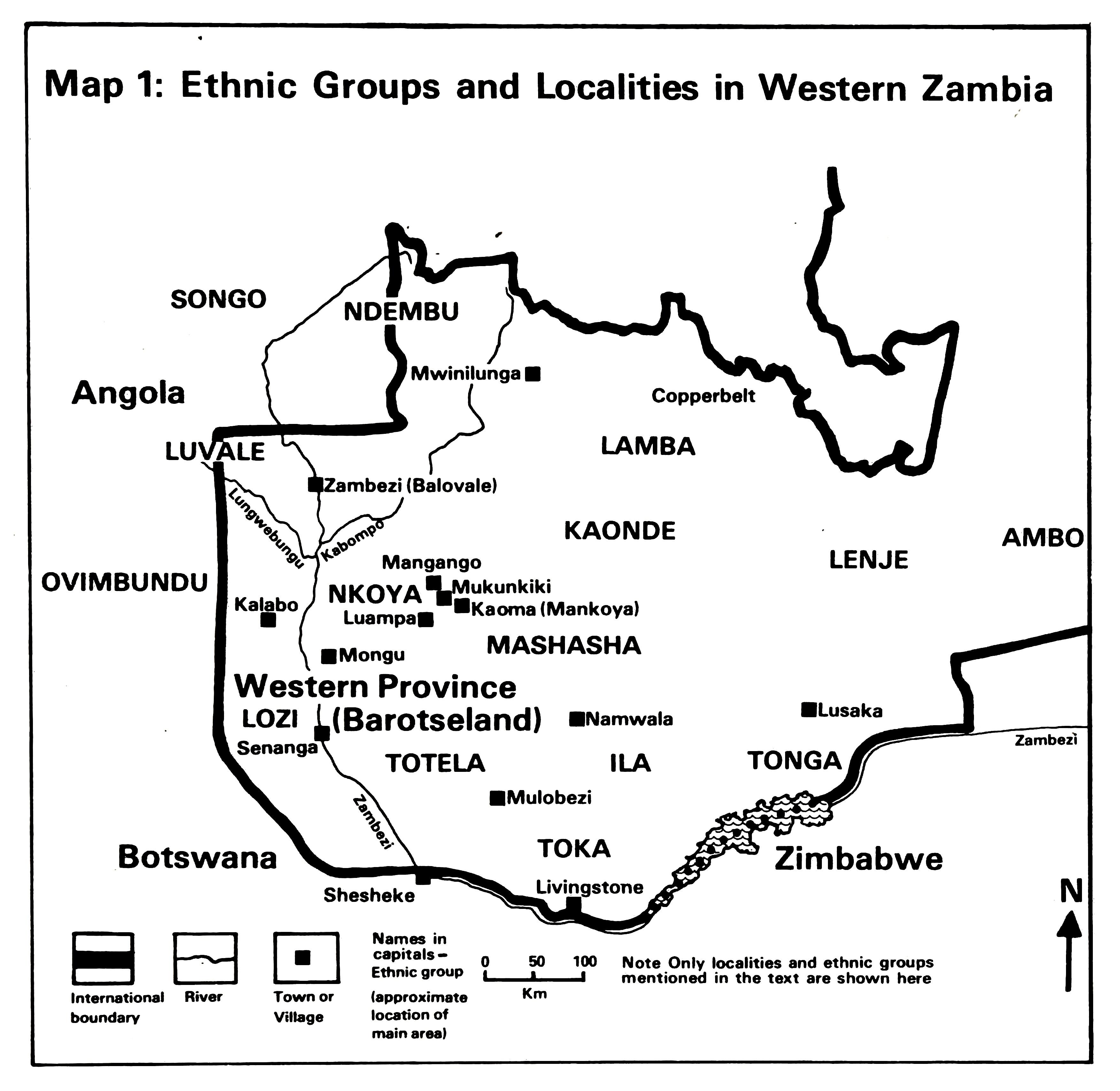

6. Regional and Non-regional Cults of Affliction in Western Zambia

2. Non-Regional Cults of Affliction

2.4 Roles, Personnel and Organization

2.5 Ritual Leadership as a Callin

3. Regional Cults of Affliction in Western Zambia: General Characteristics

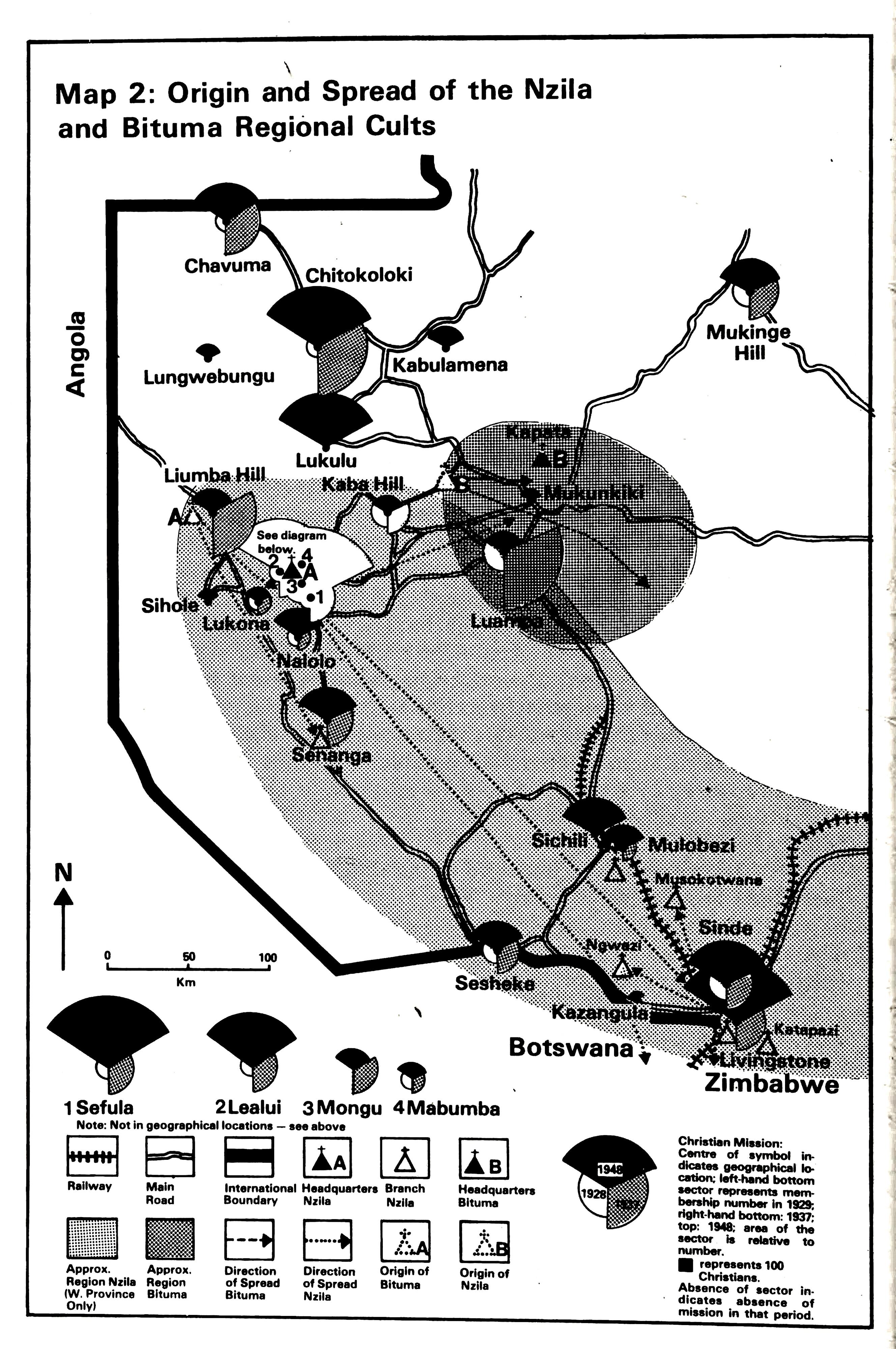

4. The Development of Nzila and Bituma as Regional Cults

4.3 Bituma and Nzila compared from within

4.4 Nzila’s and Bituma’s Regions Compared

Part Three: Regional Instability: Cult Policy and Competition for Resources

7. Continuity and Policy in Southern Africa’s High God Cult

Introduction: The Definition of Regions

The Development of a Region and the Limits of its Expansion

The Priesthood and Its Managerial Problems

Hierarchy and the Making of Oracular Policy

8. Cult Idioms and the Dialectics of a Region

The Formal Organisation of the Cult

The Spirit Medium and the Informal Operation of the Cult

The Mbona Medium and the Chiefs

The Encounter between Medium and Principals

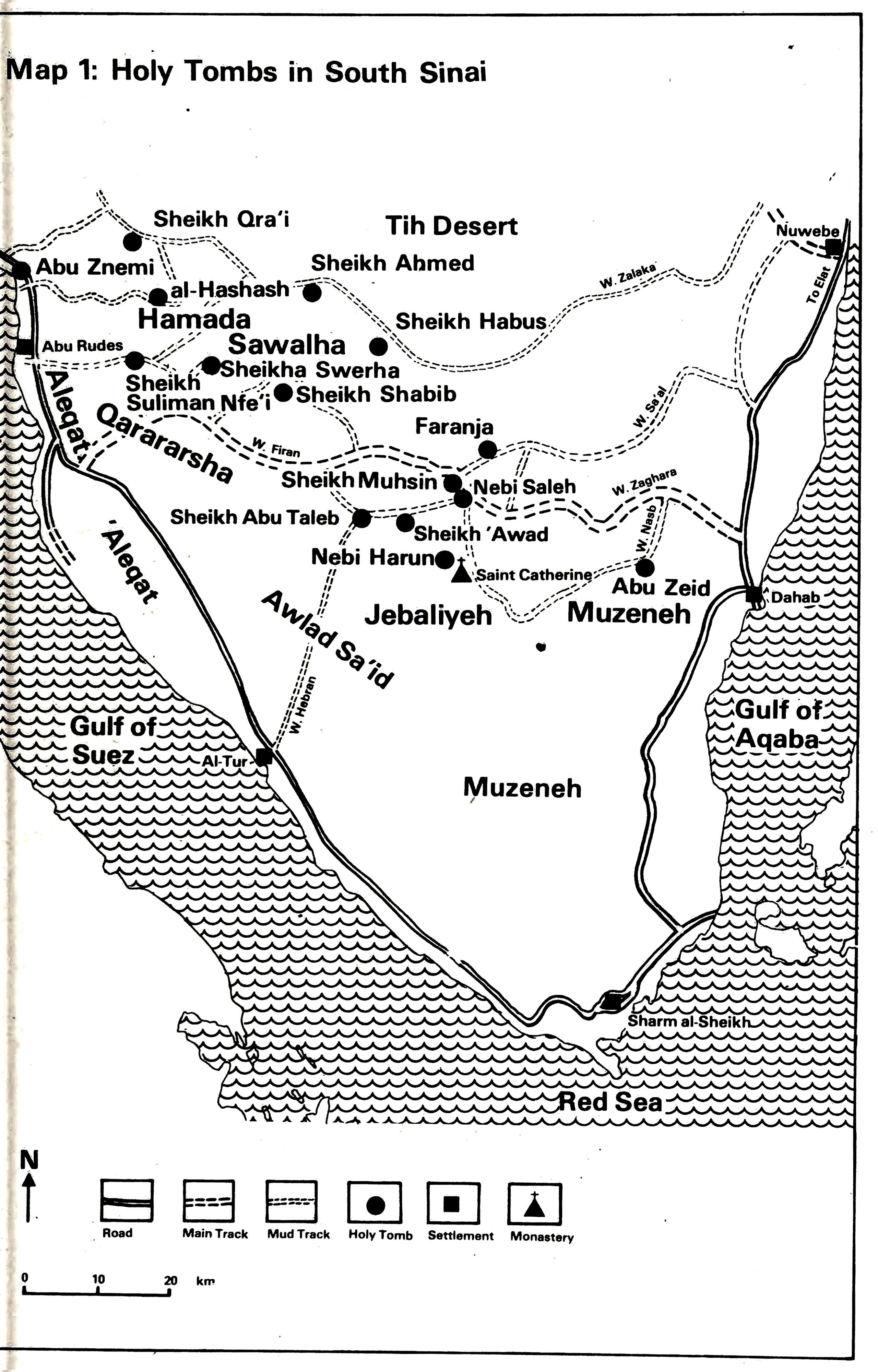

[Front Matter]

[Synopsis]

From the introduction:

“Regional cults are found in many parts of the world. They are cults of the middle range — more far-reaching than any parochial cult of the little community, yet less inclusive in belief and membership than a world religion in its most universal form. Their central places are shrines in townsand villages, by cross-roads or even in the wild, apart from human habitation, where great populations from various communities or their representatives come to supplicate, sacrifice or simply make pilgrimages.”

This book (which is derived from the 1976 ASA Conference) is the first attempt by social anthropologists to create a theoretical framework for the comparative analysis of these cults. It gives the study of religious organizations a new perspective on major historical transformation from the pre-colonial past to the neo-colonial present, in North and South-central Africa, South America and the Middle East. It advances a basic debateabout opposed theories of religion and society inspired by Robertson Smith, Durkheim and Marx. The focus is on the problems of change in trans-cultural symbolism and relationships which cross political, economic or ethnic boundaries. Most of the case studies are from South-central Africa, allowing a comprehensive view of cults in a core area over a long period of time. The overall coverage is also inclusive of Islamic marabouts, Christian and non-Christian prophets, local territorial mediums, High God oracles. Numerous maps, diagrams and charts illustrate the distribution and regional patterns of the various cults.

The book introduces new concepts and a rich body of data of interest to social anthropologists, sociologists, students of comparative religion, history, politics, economic development and cultural evolution.

Association of Social Anthropologists: A Series of Monographs

13. J.B. Loudon, Social Anthropology and Medicine — 1976

14. I. Hamnett, Social Anthropology and Law — 1977

15. J. Blacking, The Anthropology of the Body. In preparation

16. R.P. Werbner, Regional Cults — 1977

[Title Page]

A.S.A. MONOGRAPH 16

Regional Cults

Edited by

R.P.WERBNER

Department of Social Anthropology

University of Manchester, England

1977

ACADEMIC PRESS

London • New York • San Francisco

A Subsidiary of Harcourt Brace Jovanovich, Publishers

[Copyright]

ACADEMIC PRESS INC. (LONDON) LTD.

24/28 Oval Road,

London NW1

United States Edition published by

ACADEMIC PRESS INC.

111 Fifth Avenue,

New York, New York 10003

Copyright© 1977 by

association of Social Anthropologists of the Commonwealth

All Rights Reserved

No part of this book may be reproduced in any form by photostat, microfilm, or any other means, without written permission from the publishers

This volume derives mainly from material presented at a conference on regional cults

sponsored by the Association of Social Anthropologists of the Commonwealth

held at Langdale Hall, University of Manchester, March 31st—April 3rd 1976

Library of Congress Catalog Card Number: 77–71803

ISBN: 0-12-744950-7

Printed in Great Britain by

Whitstable Litho, Whitstable, Kent

[Dedication]

For Max Gluckman

In Memory

Contents

Introduction

RICHARD P. WERBNER

Beyond Naive Holism

Level Specific Analysis

Turner’s Exclusive and Inclusive Domains

The ‘Correspondence’ Theory

Elitist versus Egalitarian Regional Cults

Hierarchy and the Waxing and Waning of Cults

The Interpenetration of Cults

Future Research

References

Part One: Islamic Cult Regions: Historical Interaction or Symbolic Congruence

1. Ideological Change and Regional Cults: Maraboutism and Ties of ‘Closeness’ in Western Morocco

DALE F. EICKELMAN

Ideologies and the Social Order

Maraboutism as a Part-Ideology

The Sherqawi Zawya

Maraboutism and “Closeness”

Maraboutic Descent

Ideology and Practice

Sacrifices and Social Groups

Conclusion

References

2. Communal and Individual Pilgrimage: The Region of Saints’ Tombs in South Sinai

EMANUEL MARX

Introduction: The Region and the Wider Universe in the Cult

Three Tribes and their Setting in the Peninsula

‘Tribal Organization’ as Ideology

Annual Migration and Pilgrimage

The Symbolism of Saints’Tombs

References

Part Two: Regional and Non-Regional Alternatives: The Waxing and Waning of Cults

3. Disparate Regional Cults and a Unitary Field in Zimbabwe KINGSLEY GARBETT

Introduction: The Interpenetration of Cults

The Region of Mutota

The Land-Shrine Community

Lineal and Territorial Aspects

Change in Ritual Territories

Expansion and the Regional Medium

The Decline of Chthonic Cults

Kupara’s Recruitment

The Linking of Local and Territorial Cults

Conclusion

References

4. Bush Negro Regional Cults: A Materialist Explanation

BONNO THODEN VAN VELZEN

Introduction: Radical Economic Change and Cults

Heydays

The Spread of a Regional Cult and its Centralization

Theology

Allocation of Resources and Internal Distribution

Gaan Tata’s Bulwark on the Tapanahoni

Gaan Tata’s Decline

A New Regional Cult?

Summary

References

5. A Continuing Dialogue: Prophets and Local Shrines among the Tonga of Zambia

ELIZABETH COLSON

Cults and their Publics

The Setting and the Cults

Shrine Custodians

Prophets and the Greater Community

The Diversification of Society

Continuity and Change in the Cults

The Gwembe Resettlement: A Test Case

Prophets and Custodians

References

6. Regional and Non-Regional Cults of Affliction in Western Zambia

WIM M.J. VAN BINSBERGEN

Introduction: Change and Types of Cult

Non-Rcgional Cults of Affliction

Regional Cults of Affliction in Western Zambia:

General Characteristics

The Development of Nzila and Bituma as Regional Cults

Conclusion

References

Part Three: Regional Instability: Cult Policy and Competition for Resources

7. Continuity and Policy in Southern Africa’s High God Cult

RICHARD P. WERBNER

Introduction: The Definition of Regions

Change in Congregations

The Development of a Region and the Limits of its Expansion

The Priesthood and its Managerial Problems

Hierarchy and the Making of Oracular Policy

References

8. Cult Idioms and the Dialectics of a Region

J.M. SCHOFFELEERS

Introduction

The Formal Organisation of the Cult

The Chiefs and the Shrine

The Spirit Medium and the Informal Operation of the Cult

The Medium’s Entourage

The Mbona Medium and the Chiefs

The Encounter between Medium and Principals

Rumour and Possession

The Conceptualization of a Regional Community

References

Notes on Contributors

Author Index

Subject Index

Maps

Introduction

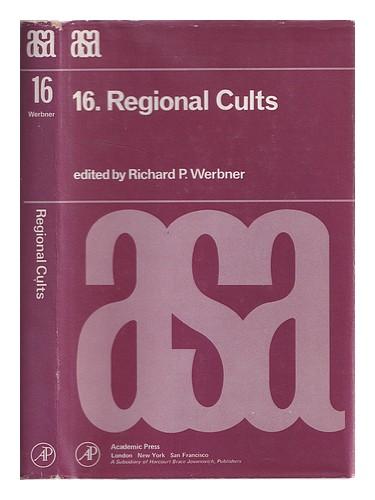

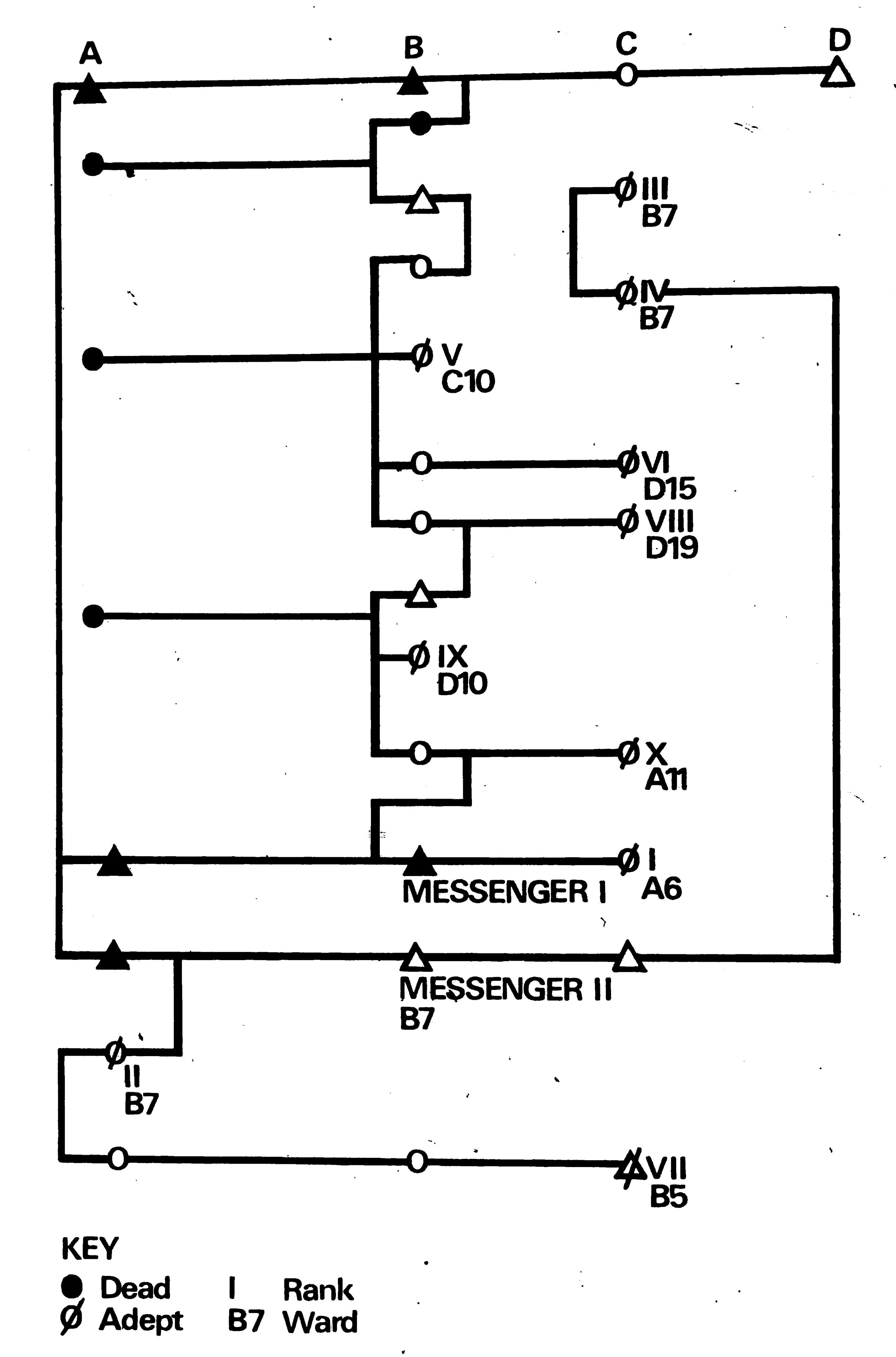

1 Regional Cults in South-Central Africa

Chapter 1

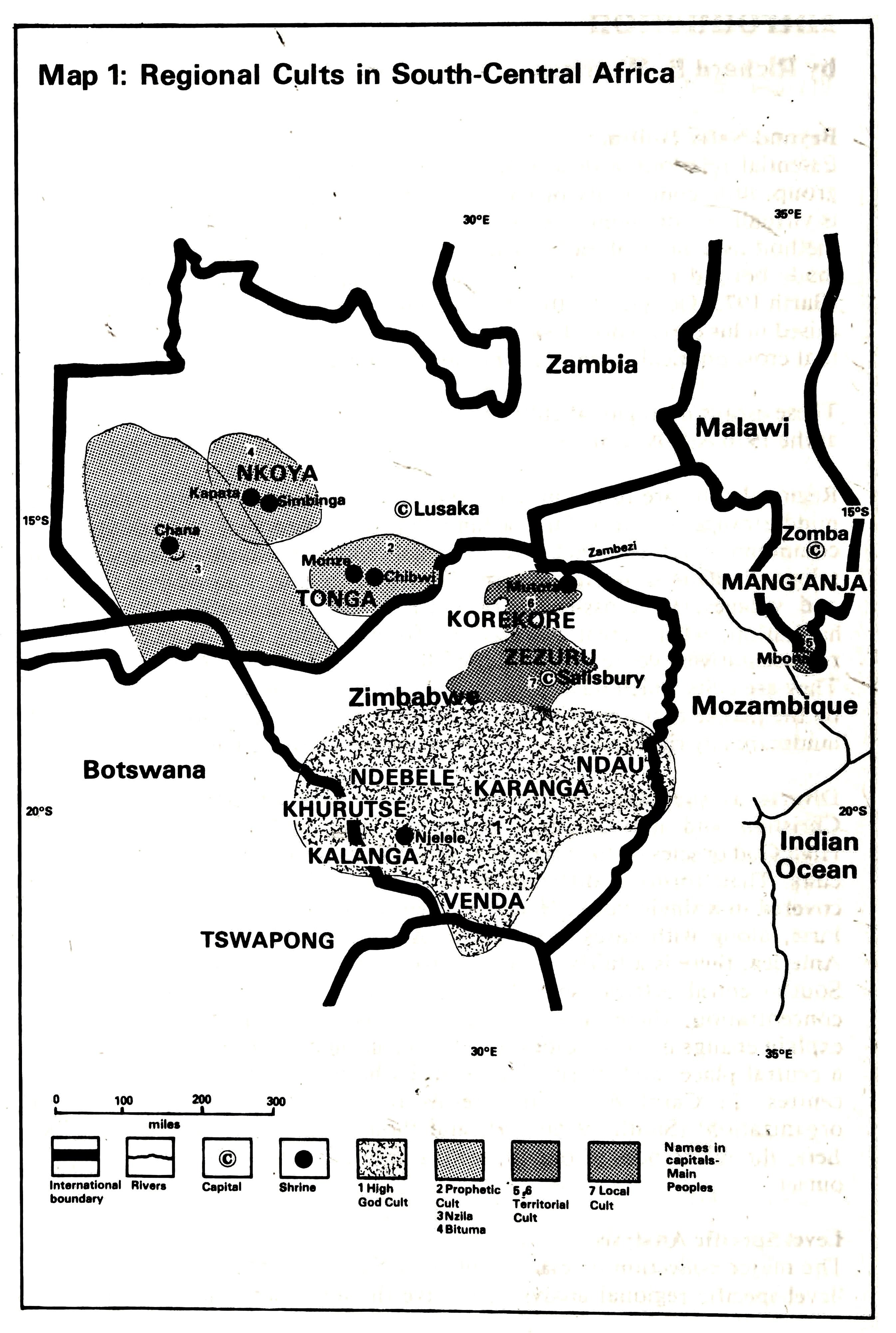

1 Spheres of Sherqawi Influence in Western Morocco

Chapter 2

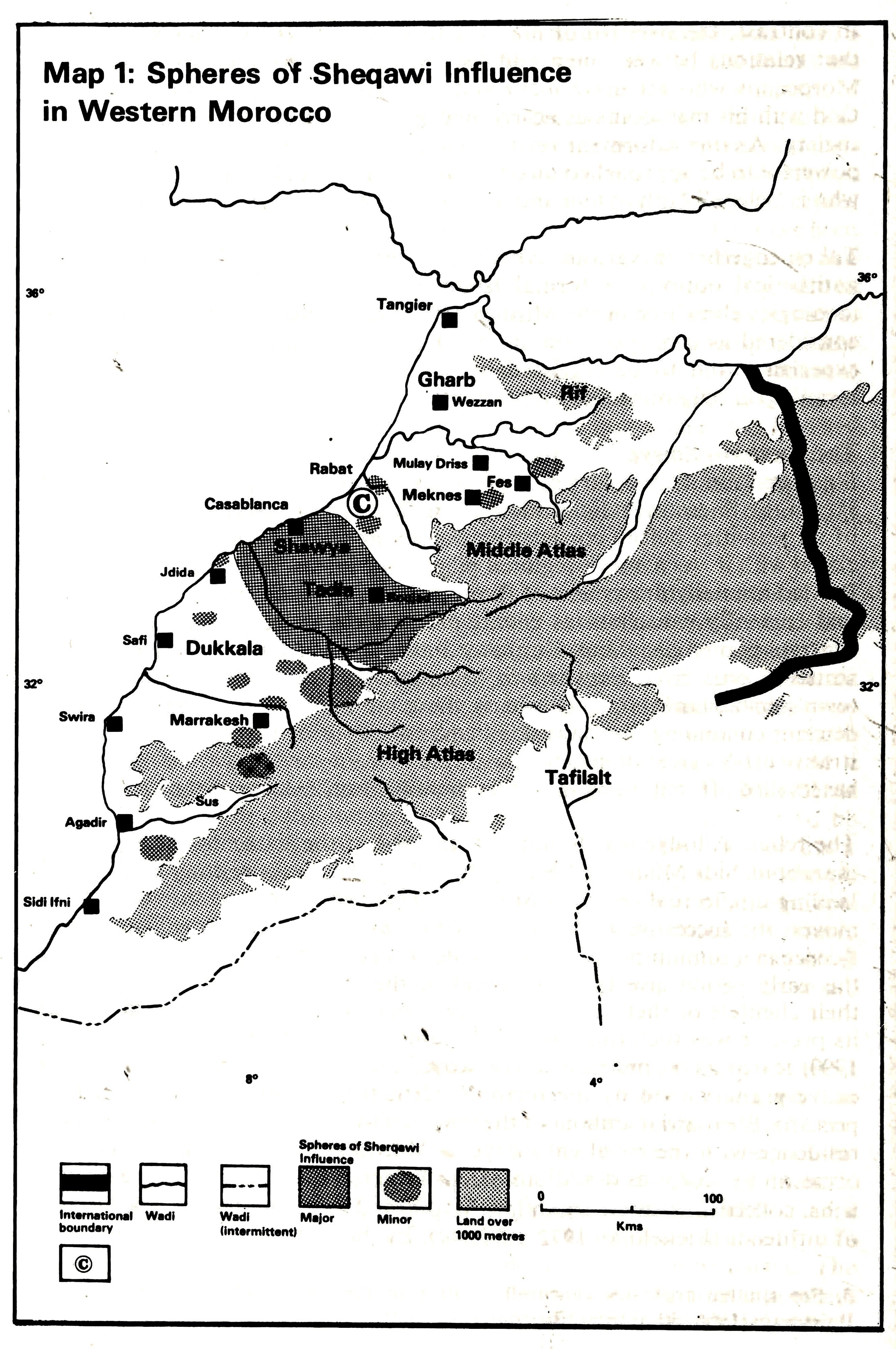

1 Holy Tombs in South Sinai

Chapter 3

1 Region of Mutota: Spirit Provinces and Chthonic Cult Areas, Dande (1963) Zimbabwe

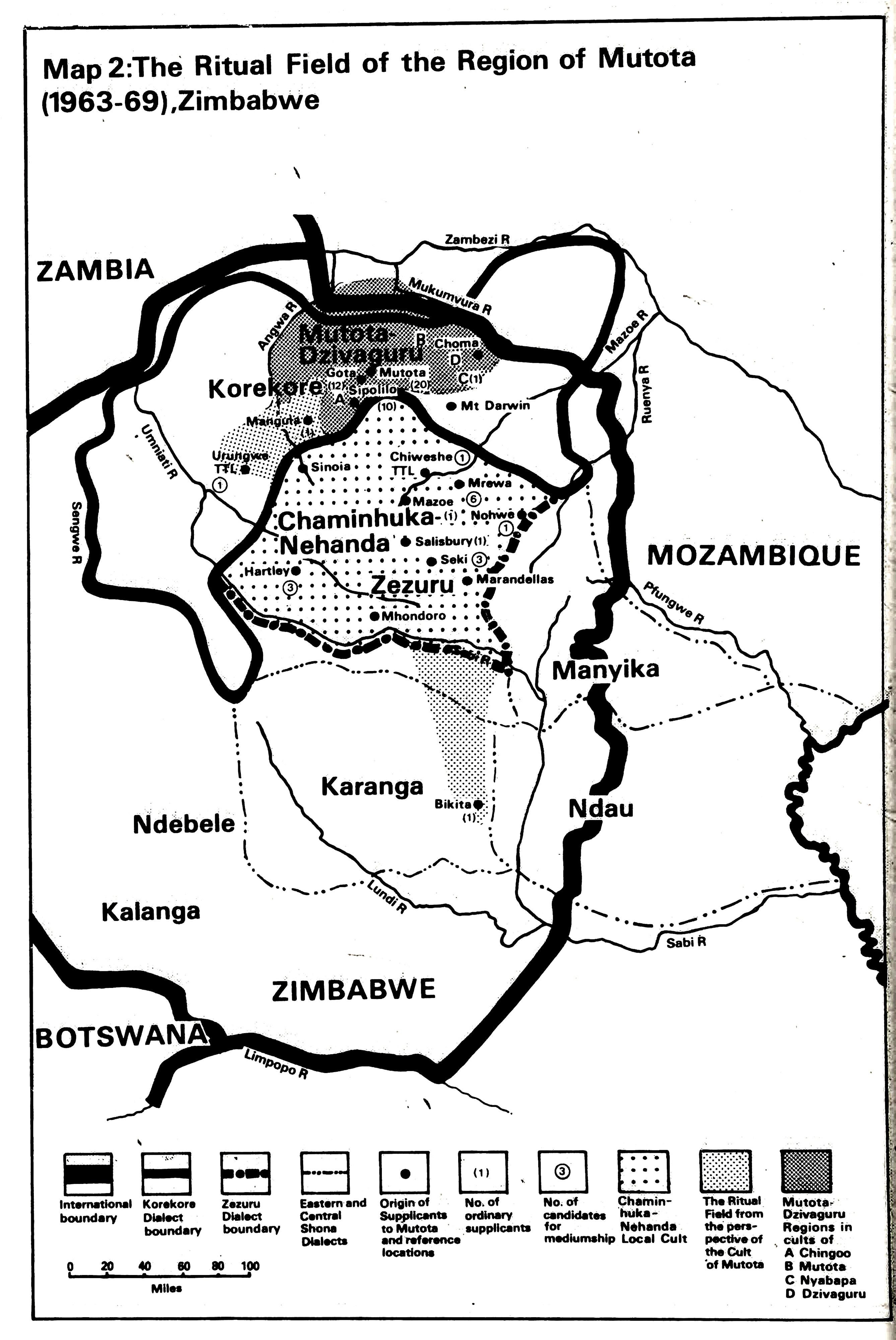

2 The Ritual Field of the Region of Mutota (1963–69), Zimbabwe

Chapter 4

1 Gaan Tata Cult and Christian Mission Posts (c. 1900), Surinam

Chapter 5

1 Prophets and Local Shrines: Zambian Tonga and their Neighbours in Zimbabwe

Chapter 6

1 Ethnic Groups and Localities in Western Zambia

2 Origin and Spread of the Nzila and Bituma Regional Cults

Chapter 7

1 Congregations and Shrines of the High God Cult, Northeastern Botswana facing

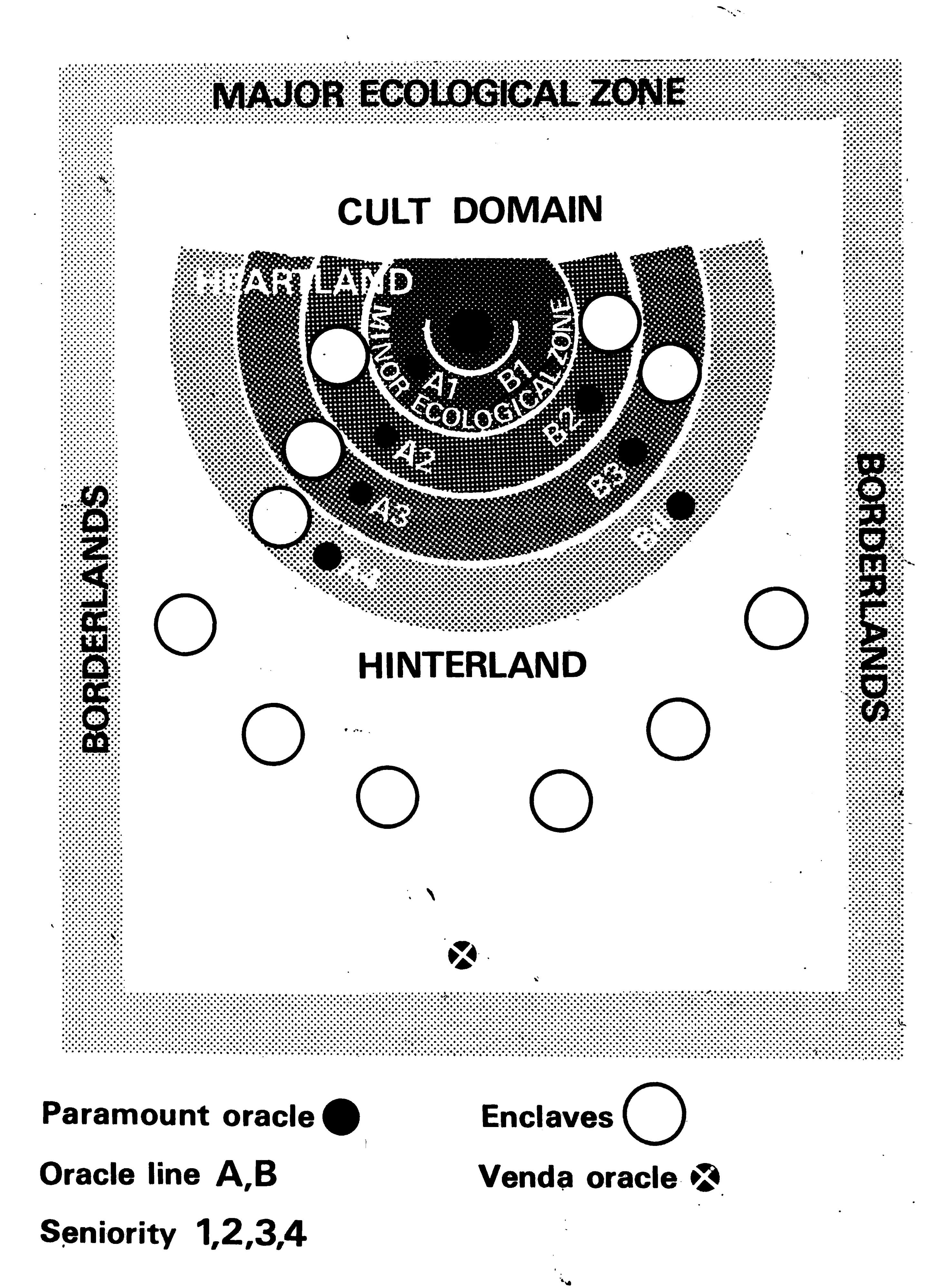

2 Territorial Divisions in Northeastern Botswana

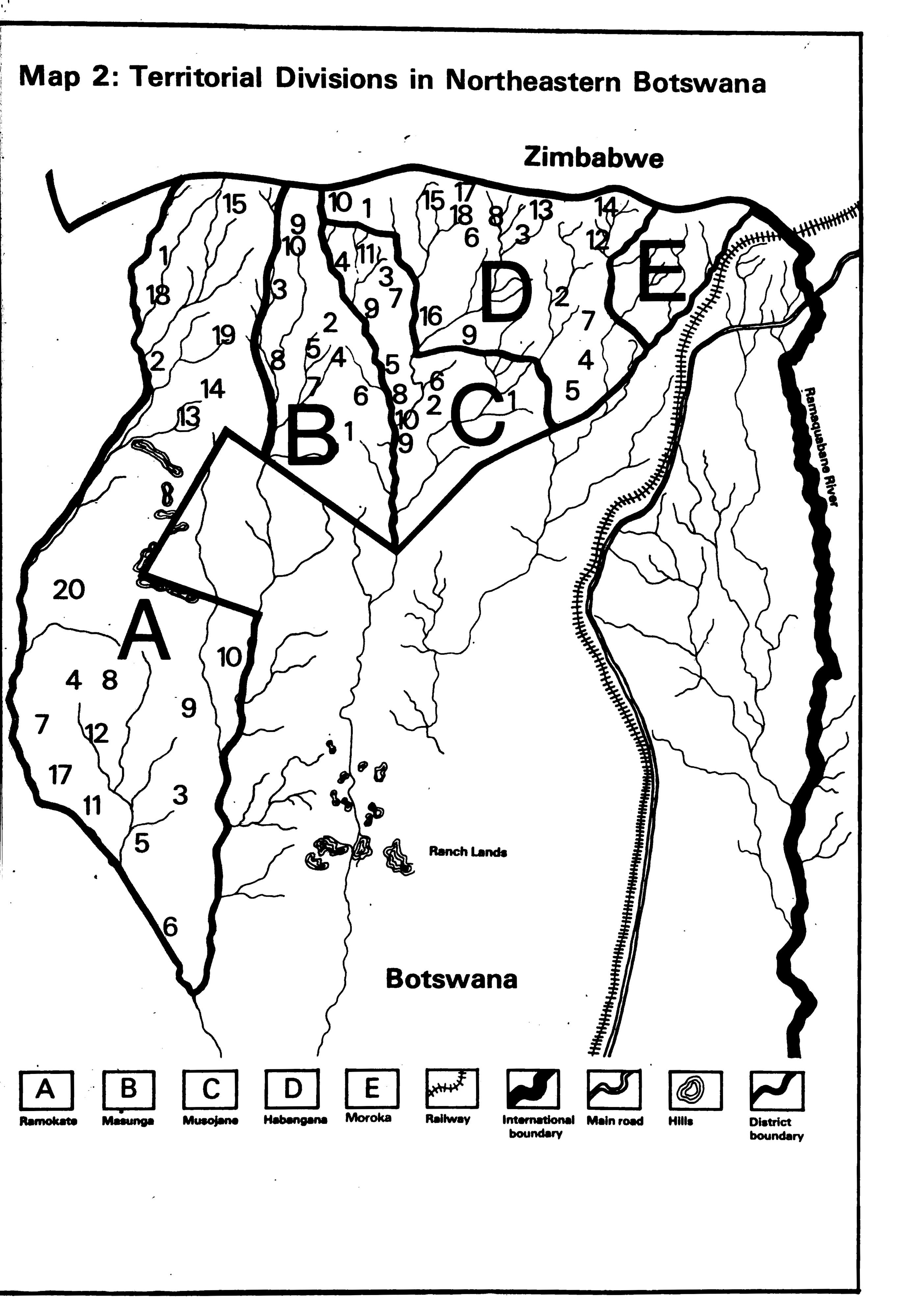

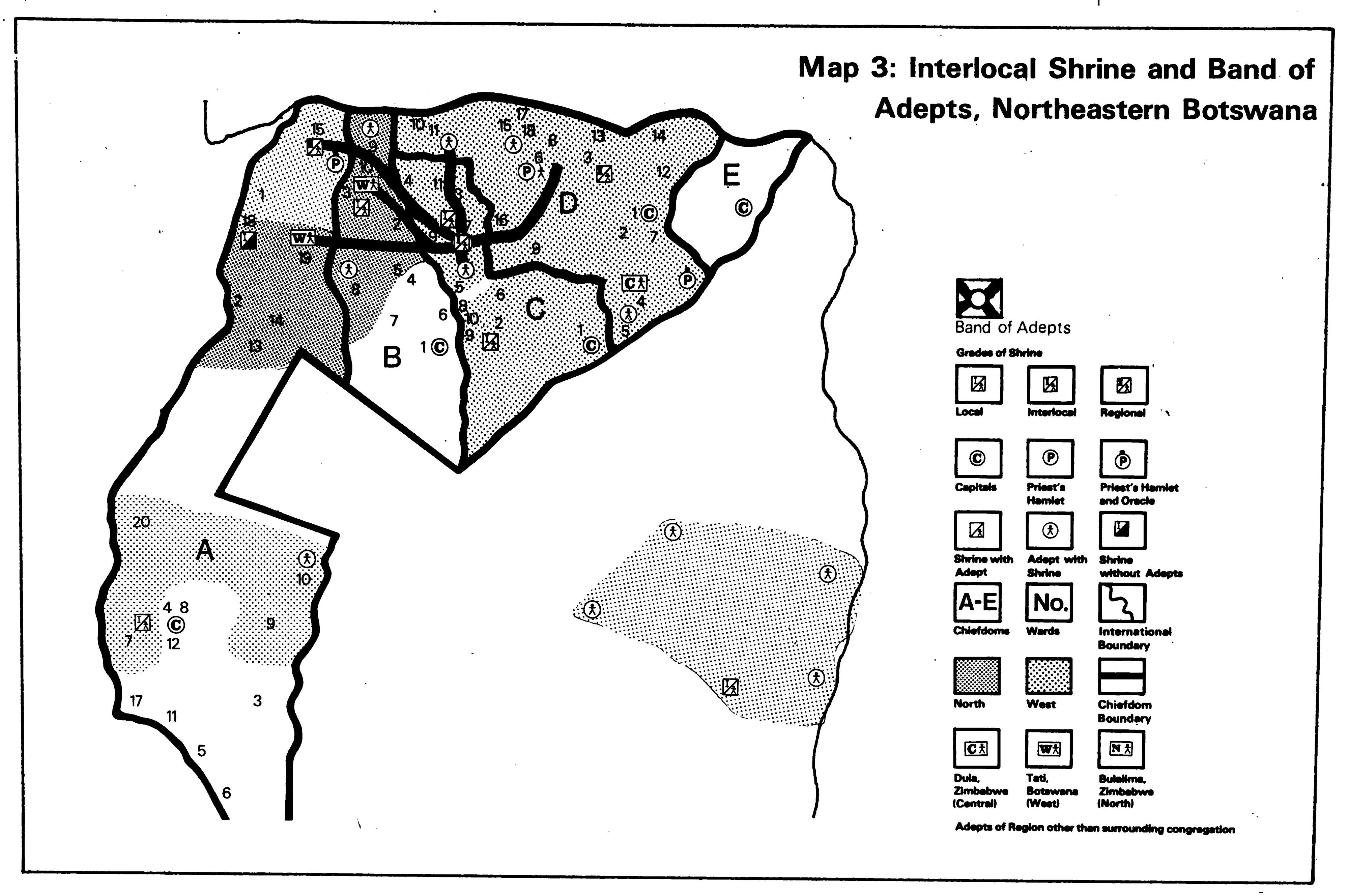

3 Interlocal Shrine and Band of Adepts, Northeastern Botswana

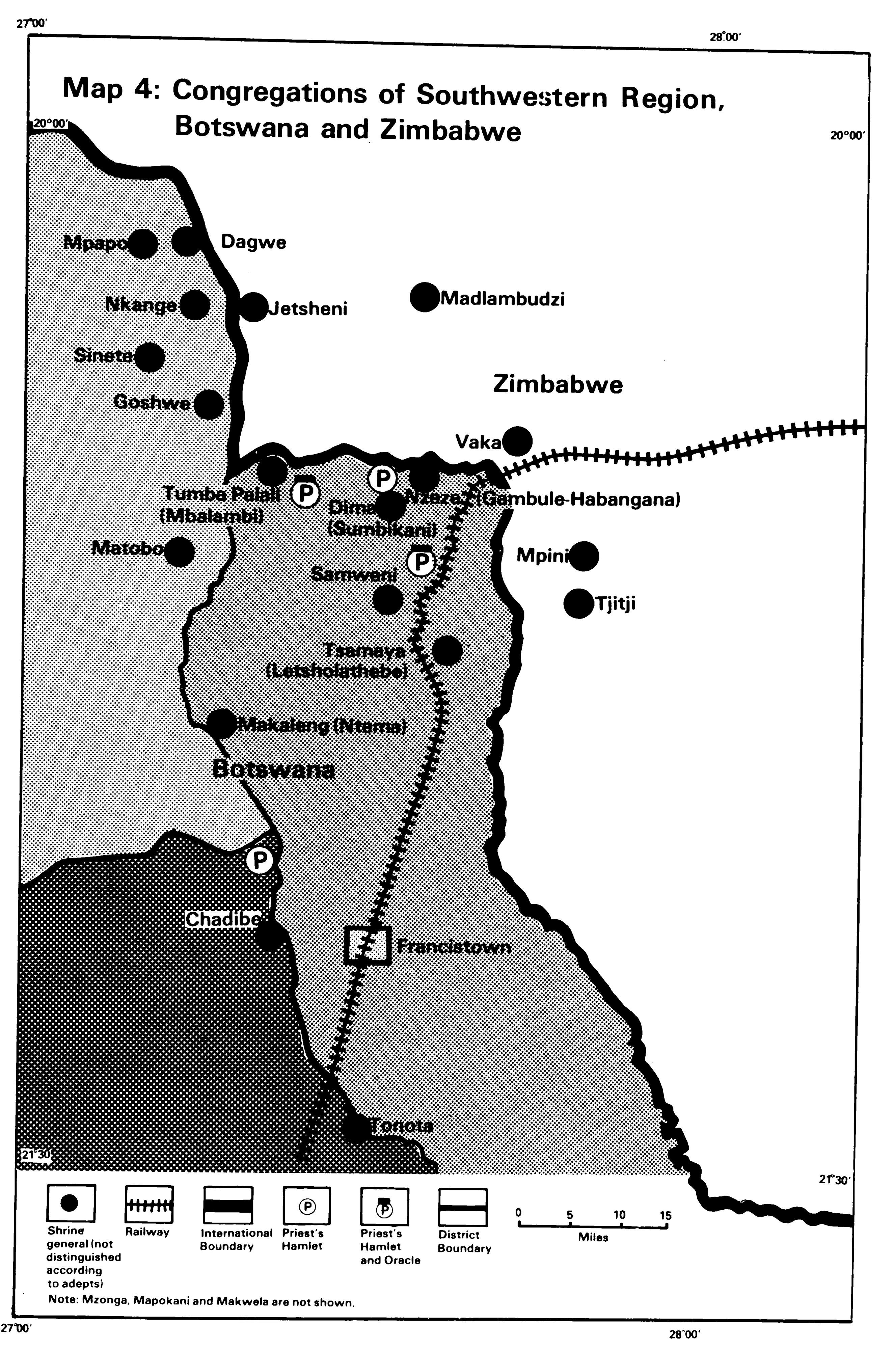

4 Congregations of Southwestern Region, Botswana and Zimbabwe

Chapter 8

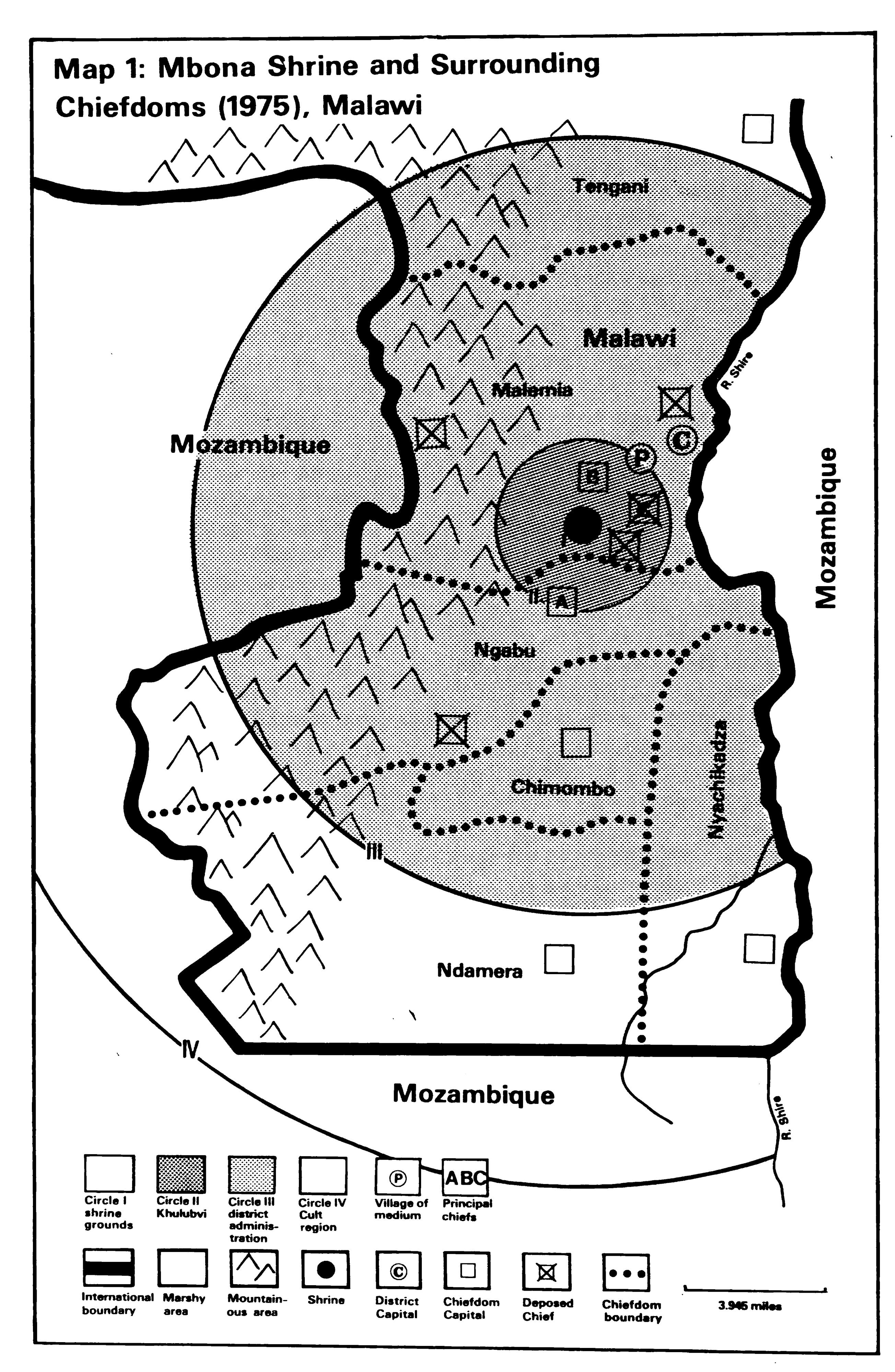

1 Mbona Shrine and Surrounding Chiefdoms (1975), Malawi

Diagrams

Chapter 7

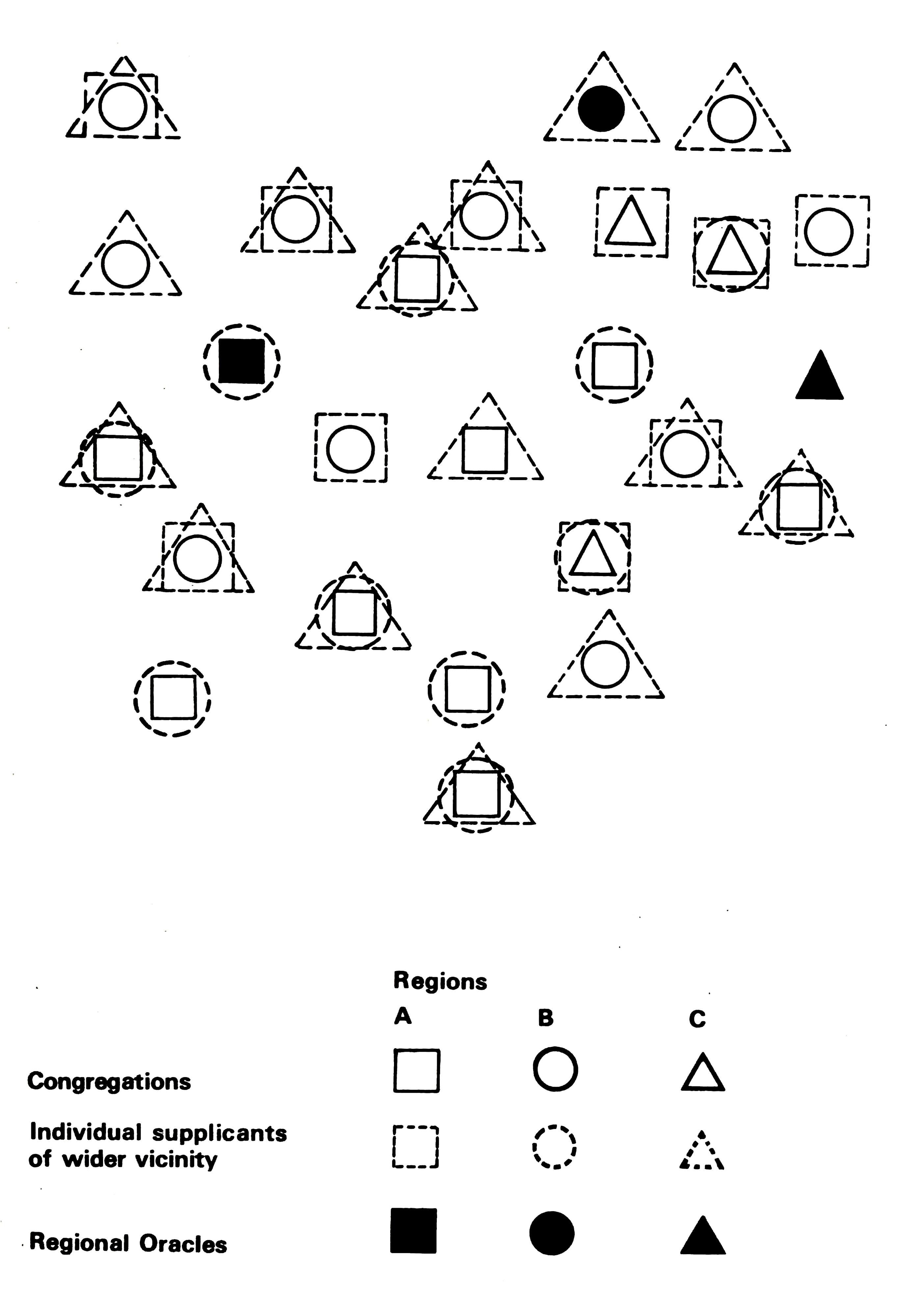

1. Regions and their Surrounding Vicinities

2. Cult Domain and Ecological Zones: Distribution of Oracles

Genealogies

Chapter 3

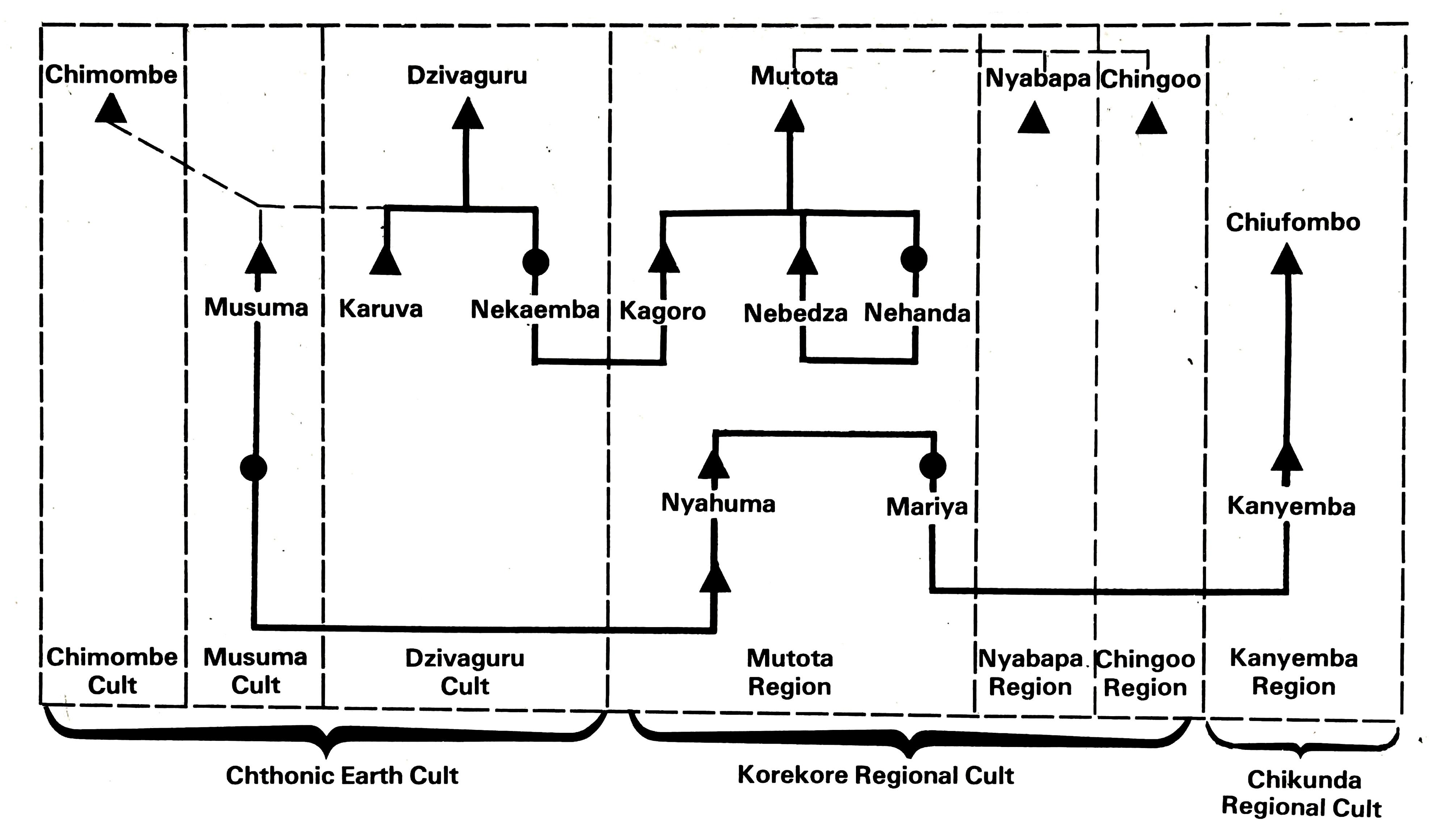

1 Perpetual Relations among Korekore, Chthonic and Chikunda Regional Cults

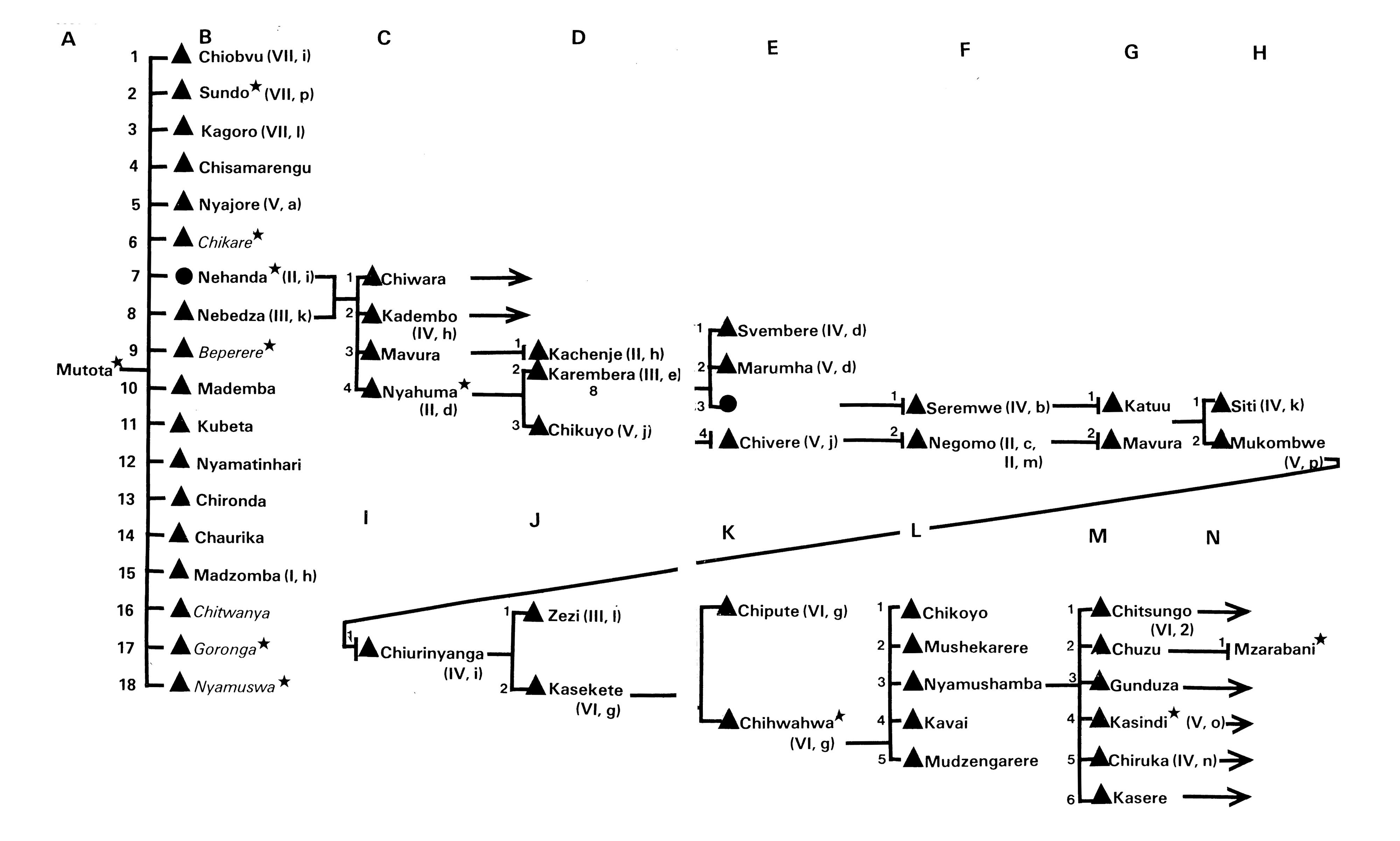

2 Mutota’s Descendants

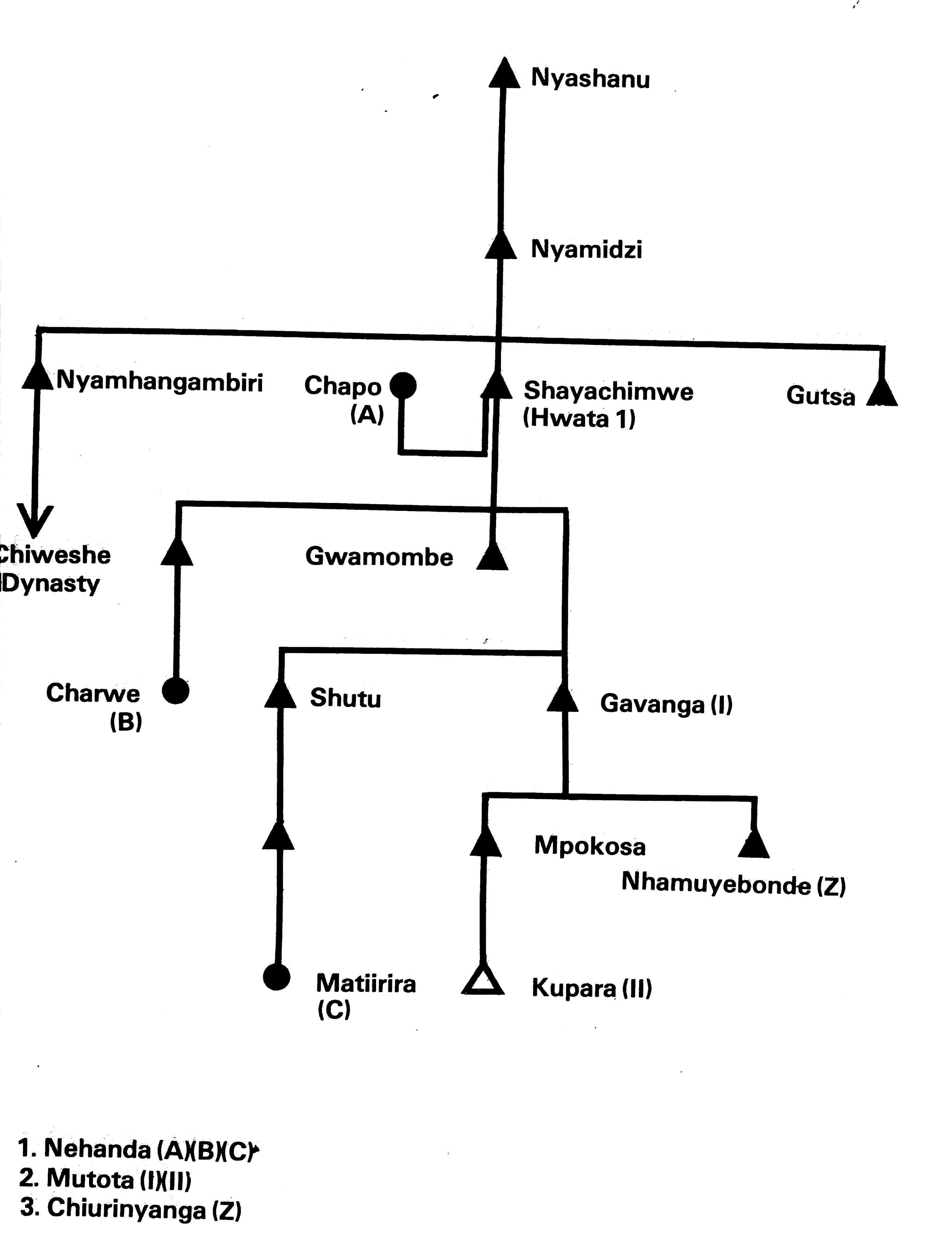

3 Succession to Mediumships

Chapter 7

1 Genealogy of a Band of Adepts

Tables

Chapter 2

1 Bedouin Tribes of South Sinai

Chapter 3

1 Index of Spirit Provinces shown in Map I

Chapter 7

1 Succession of Adepts

2 Recruitment of Junior Adepts

3 Recruitment of Senior Adepts

Charts

Chapter 7

1 Grades of Shrine

2 Western Regions of the High God Cult

Chapter 8

1 Resume of Origin Myths of Two Principals

2 Mbona Mediums in the Twentieth Century

Introduction

by Richard P. Werbner

Beyond Naive Holism

Essential relations with a wider context get stripped away when a small group, little community or tribe is studied as an isolated whole. This idea is virtually a commonplace, and it is now conventional, also, to reject the method as a fault of earlier studies. Yet relatively little advance has been made beyond naive holism — indeed, it may be winning new advocates (Barth 1975; Douglas 1970). The challenge remains one that Max Gluckman raised in his early work (1940, 1942): to analyse change in fields of relations that cross political, economic or ethnic boundaries.

These essays on regional cults, which derive mainly from papers presented at the 1976 A.S.A. Conference in Manchester, take up that challenge.

Regional cults are found in many parts of the world. They are cults of the middle range — more far-reaching than any parochial cult of the little community, yet less inclusive in belief and membership than a world religion in its most universal form. Their central places are shrines in towns and villages, by cross-roads or even in the wild, apart from human habitation, where great populations from various communities or their representatives, come to supplicate, sacrifice, or simply make pilgrimage. They are cults which have a topography of their own, conceptually defined by the people themselves and marked apart from other features of cultural landscapes by ritual activities (on ritual topography see Turner 1974 : 183).

Diverse as the cases in this book are — cults of Islamic marabouts, Christian and non-Christian prophets, local and territorial mediums, High God oracles — they represent much less than the full range of regional cults. Their forms in different parts of the world are far too many to be covered in a single book. Hence this selection is concentrated in two ways. First, along with cases from North Africa, the Middle East and South America, there is a fairly representative coverage in one part of the world, South-Central Africa (see Map 1). Second, besides such ethnographic concentration, there is a theoretical focus: our primary concern is to explain change in the ideology and organization of cults which are based on a central place and its relations with its hinterland or smaller dependent centres. In Carol A. Smith’s terms these cults are ‘nodal forms of organization’ (Smith 1976b : 9), and though our focus is somewhat like hers, the differences in our theoretical interests need to be seen from the outset.

Level Specific Analysis

The major collection of essays edited by Smith (1976a, 1976b) develops a ‘level-specific regional analysis’, to give the approach a label of its own. Concerned primarily with complex societies, this approach relies on a model of levels — local, regional, national — and focuses specifically on the level (this may be a set, rather than a single level) that is always intermediate between the other levels in the model, namely the regional. Analytically, the limitation to a specific level has considerably force, at least for the comparative purposes which Smith and her contributors have in mind. Their cross-societal generalizations apply to standard units; they avoid the misplaced comparison of unlike orders of relations. But the gain in comparability is costly. Indeed, without radical modification it is too costly for the approach to be applied in order to make sense of change in regional cult organization and ideology.

In empirical terms, the cost arises because the approach makes no room for certain activities and phenomena which are crucial in regional cults. As Smith stresses, regional analysis aims to show how

‘flows of goods, services, information, and people through [a] network of centres ... structure and maintain internodal relations’ (Smith 1976b : 8, Smith’s italics).

In regional cults such flows run across major political or ethnic boundaries. Hence the characteristic direction of the flows, along with the cult’s distinctive topography, is of specific theoretical interest. However, the level-specific approach ignores activities overriding and not congruent with the boundaries and subdivisions of a nation. Similarly neglected are the phenomena which define international or non-national regions. Theoretically, the approach introduces a bias towards nesting relations and it does not allow for cultural variability, i.e., the variable importance of different conceptions held by the people studied themselves of their fields of relations. To overcome these and other limitations calls for quite a different approach to regional analysis, without the three tiered model or its level-specific assumptions. Hence, our analysis of regional cults takes as problematic and subject to explanation what level-specific regional analysis neglects or takes for granted.

Our theoretical interests lead us to pay most attention to the historical transformation of cult regions. How do the people themselves define and organize their cult regions over time, through radical economic or political change and also in more stable periods? How do religious ideas and practices alter as cult regions become more or less inclusive? What impact do regional and non-regional cults have on each other, and how do they wax and wane in relation to each other? Some of these are problems which Victor Turner, too, considers in a discussion of ‘Pilgrimages as Social Processes’ (1974 : 166–230). Turner’s suggestions differ somewhat from ours, and it is fruitful to clarify some of the differences, particularly because a good part of our work builds on this and other discussions of his (Turner 1957, 1967, 1968, 1975).

Turner’s Exclusive and Inclusive Domains

Parallel dichotomies are at the heart of Turner’s argument: inclusiveness versus exclusiveness, peripherality versus centrality, generic versus particularistic relationships, egalitarianism or homogeneity versus nonegalitarianism or differentiation. For our purposes, the most crucial is a dichotomy

between politico-jural rituals focused on localized subsystems of social groups and structural positions, and rituals concerned with the unity and continuity of wider, more diffuse communities’ (Turner 1974 : 197).

Only a few of his conclusions need concern us here, although it is through these dichotomies that he arrives at a much larger body of conclusions, along with a general perspective on the very process of pilgrimage itself. Three conclusions are relevant here: first, about opposed types of cult; second, about how far cult ideologies represent or correspond with various politico-jural relations; and finally, about the dialectical way that one type of cult becomes its opposite.

The conclusions have to do with opposed types of cult in two kinds of society, once more a dichotomous division. On the one hand, Turner refers, in ‘certain traditional African societies’, to earth and fertility cults (most of which are regional cults in our terms) versus ancestral and political cults (apparently non-regional). On the other hand, he refers, in ‘complex large-scale societies and historical religions’, to pilgrimages and the organization of pilgrimage centres (again, mainly regional) versus localized religious activities focused on local shrines, ‘which are themselves parts of bounded social fields, and which may constitute units in hierarchical or segmentary politico-ritual structures’ (Turner 1974 : 186) (again, apparently non-regional). This is his suggestion about the African cults:

... ancestral and political cults and their local embodiments tend to represent crucial power divisions and classificatory distinctions within and among politically discrete groups, while earth and fertility cults represent ritual bond between those groups, and even, as in the case of the Tallensi tendencies toward still wider bonding. The first type stresses exclusiveness, the second inclusiveness. The first emphasizes selfish and sectional interests and conflict over them; the second, disinterestedness and shared values’ (Turner 1974 : 185).

Similarly, he sees a parallel in the contrasting kind of society:

‘The networks formed by intersecting pilgrimage routes ... represent at the level of pre-industrial, politically centralized, high-agricultural cultures, the homologues of those reticulating the earth shrines and shrines of non-ancestral spirits and deities found in many stateless societies in sub-Saharan Africa with simple agricultural technology.

Here the peripherality of pilgrimage centers distinguishes them from the centrality of state and provincial capitals and other politico-economic units. It further distinguishes them from centers of ecclesiastical structure such as the sees or diocesan centers of arch-bishops and bishops’ (1974 : 197).

The great utility of this contrast is its illumination of extreme cases. Like other ideal typologies, however, it tends to represent as mutually exclusive alternatives — the halves of parallel dichotomies — what are, in fact, aspects which combine in a surprising variety of ways within a range of actual cases. In this book the chapters on Islamic and African cult regions provide such cases not covered by the typology. The point is perhaps best illustrated first by Schoffeleer’s chapter, because he views an earth or territorial cult — the Mbona cult of Malawi and Mozambique — in terms of dichotomies that are comparable to Turner’s Moreover, Schoffeleers resolves a paradox which is important for Turner’s discussion. As Schoffeleers puts it for the Mbona cult:

‘The very organization which asserts social difference and privilege becomes the vehicle through which the denial of difference and privilege is affirmed’.

Boundedness and political divisions are represented by the Mbona cult’s localized congregations and its principals. As chiefs, the latter come from the autochthonous ethnic group, the Mang’anja, with a legendary, or rather, ‘traditional’ realm, i.e., the current bounds of the cult’s region, and in legendary times, all their chiefdoms were under the centralized rule of a single paramount chief. Not that the cult region merely replicates some political organization which exists apart from the cult’s activities: the political communities which it covers are in different countries, and they do not now exist as one body under any paramount ruler or even a single government. Instead, the cult region has its own nodal organization, and its own centre alone provides the focus for the region, quite distinct from any other political or economic centres. Its spirit medium, usually an immigrant rather than an autochthon, but never a chief or cult principal, makes his pronouncements on the public morality of chiefs and criticizes their relations with their people. But he does so only during seances at the region’s innermost shrine, while he is possessed by the spirit of Mbona. For the whole region and from its centre he speaks with an authority that goes beyond that of any central government and is independent of it; thus, he readily becomes a focus of resistance to unpopular measures imposed by the government.

The centre of this territorial cult is the extra-territorial sanctuary, an area beyond the territorial jurisdiction of any government and thus free of its taxes and rules of land tenure. Within it, and well apart from the seat of any legendary paramount is the cult’s innermost shrine. Within the sanctuary also, the cult hero, Mbona, was murdered, according to myth, at the first paramount’s command, after Mbona became a rival for political influence because of his powers as a rainmaker. It is according to the location of events associated with Mbona’s martyrdom that the sanctuary is centralised and set apart in cult topography. Hence the myth about the sanctuary emphasizes more than separateness, externality or even centralization: it ‘projects an image of a region which is unified on the basis of common concerns and a common morality’, but it also presents a paradigm for power struggles and an opposition between chiefly and non-chiefly ritual authority.

Whereas Turner suggests that types of cult fit a ‘polar distinction between cultural domains of exclusivity and inclusivity’ (1974 : 186), Schoffeleers demonstrates that both such domains are polarised within the Mbona cult. Each donjain is emphasized by different protagonists who oppose each other in the cult. From one viewpoint, the Mbona cult appears as an unstable combination of both of Turner’s types, and it is unstable just as the domains themselves are, in relation to each other. Schoffeleers shows that there is a persistent struggle between the representatives of political hierarchy — the cult principals as chiefs — who assert the legitimacy of social differentiation, and the representative of their people — the medium — who puts forward ‘the conception of a non-differentiated society’ [what Turner might call ‘ideological communitas’ (1974 : 1697]. Furthermore, the dialectic in this struggle is such that the representative of the people comes to appeal increasingly to more inclusive conceptions and idioms:

Mbona is now said to be the “Son of God” (Mwana wa Mulungu) and the “black Jesus” (Yesu wakuda), who is the guardian spirit of all ethnic groups, and not just of the Mang’anja.’

Here, to carry the argument a step further, we must turn to Colson’s analysis of cults and their publics among Tonga in different ecological zones of Zambia. In some respects the Tonga prophet cult, compared with the Mbona cult, represents an extreme at the very margin of the range of regional cults. Insofar as a region emerges in the prophet cult, it is characterized by diffuseness and ephemeral, weak, even uncertain centralization, instead of clear ritual demarcation, recognised boundedness, and a firmly anchored nodal organization for the whole region. Hence the Tonga case illuminates the grey, marginal area of relations between cult exclusiveness or inclusiveness and continuities or discontinuities in local communities.

Colson concentrates her analysis on the changing interplay between the local and the prophet cult. The local cult always has a well-defined constituency, unlike the prophetic cult. In the local cult there are numerous ’district’ or neighbourhood land shrines which are the centres of small, discrete ritual areas whose shrine custodians are independent of each other. Neither the custodians nor their land shrines form any hierarchy or more inclusive body. Colson establishes that the local cult and its communal ritual give concrete expression to the continuity and exclusiveness that a particular, highly localized agricultural community may have. The cult is stable in its land shrines and ritual — indeed, more stable than Colson herself understood on the basis of her earliest fieldwork (Colson 1948, reprinted in 1962) In the light of her continuing observation from 1946 to 1973, she now considers that ‘local shrines are remarkably viable’: they survive despite resettlement and the relocation of neighbourhoods. Over the years of her research among Plateau and Gwembe Tonga, she heard of no new local shrines. Her long-term evidence points to a great measure of cult autonomy, rather than immediate responsiveness to local fluctuations and the movements of shifting cultivators. Important as the vagaries of local shifts in villages and their populations are, they do not directly bring about the rise and fall of local shrines: land shrines have a life of their own.

The relation between the local and the prophet cults is, in the main, complementary, though not unproblematic or unchanging. The prophet serves a variable clientele and, while possessed by spirits identified with no known social community (spirits of the wild, of long dead prophets, foreign spirits and most recently, angels and God), provides warnings about personal or communal troubles and guidance about ritual for healing or rain. Most are minor prophets and play their part within an immediate vicinity roughly the same as, or little more than their own local shrine community. Colson observes:

Though they claim a power that stems from beyond the community, and is independent of it, they are subject to the community controls. They link their messages to the local order ... These prophets are, therefore, among the principal upholders of community, the land shrines and the existing custodianships.’

For both prophet and local cults in the narrowest order of relations — the local order — it can be said, in Turner’s terms, that the main emphasis is on the exclusive domain, boundedness and stability.

Beyond the narrowest order, the prophet cult is more flexible. It alters its emphasis, whereas the more rigid local cult does not, and remains virtually contained within the local order. Moreover, the flexibility of the prophet cult threatens to become a danger to the local cult, rather than merely a complement to its rigidity. Recently, prophets have proliferated along with waves of new cults of possession by angels, God, and alien spirits (see chapter six where van Binsbergen explains the importance of this phenomenon in other parts of Zambia, also). Through’ its major prophets the prophet cult addresses itself nowadays to ‘the expanding universe’ of the country at large, and thus more to the changing inclusive domain. These prophets still build shrines where offerings are made for rain and the public good by communal delegations from near and far neighbourhoods. But now clients’ personal needs bring them to major prophets as distant healers. Such prophets appeal to a widespread, heterogeneous clientele from diverse ethnic groups and urban as well as rural areas. It is here, in the wider order of relations, that the prophet cult is most strikingly flexible in response to the economic and ethnic diversification in the country at large.

The Tonga case has telling implications for Turner’s dichotomous typology. Whether a single cult (such as the Tonga prophet cult) gives greater emphasis, during a period of its history, to one domain or another may depend on the order of relations involved: the narrower the order, the greater the emphasis on the exclusive domain, and conversely. Nowadays, the inclusive domain concerns major prophets perhaps more than ever before, and certainly more than it does the run of minor prophets. Clearly, Turner’s typology does not adequately allow for such internal relativity: that is, the variation within a cult according to different orders of relations. Yet, as the Tonga case proves, such internal relativity may be crucially important.

The Tonga case raises a further point about the central places of a cult and the folk conception of regionalism. This point leads aside somewhat from our discussion of Turner’s conclusions. But it must be considered here, because it is important for regional analysis in general, and our perspective in the Tonga case in particular. Colson’s evidence is that, in one sense, regionalism is still in its infancy as a folk conception among Tonga:

‘Even the idea of a social unit of all Tonga is a recent creation and is still likely to be invoked principally in the national political arena though the continued importance of the shrine of Monze may have political overtones of which lam unaware (my italics)’.

In the part I stress Colson allows for something problematic about the most famous Tonga shrine, Monze’s. It is a matter of historical record that Monze’s shrine was the central place of a very great, perhaps the greatest, Tonga prophet of the nineteenth century: he received delegations from Tonga, Ila and Sala neighbourhoods as much as 100 miles away. No longer does any prophet reside by Monze’s shrine, yet it continues to serve a very wide vicinity, and not merely a single local community. Delegations seeking rain still come to Monze’s shrine from near and far and, significantly, from distant neighbourhoods in another ecological zone where rain is even more scarce. Why so? Or rather, what does this imply about the central places of a cult among Tonga?

The clues to the answer are in Colson’s data on prophets. Although my interpretation differs somewhat from hers, it also takes account of the apparent tenuousness of formal regional relations. From time to time, prophets of a distinct kind have arisen — regional prophets, in my view — and they have arisen in the same central area, as shown on Map I of chapter five. This central area is on the escarpment edge in the high rainfall zone. In the nineteenth century Monze was one regional prophet, and close by Chibwe was another, from the 1940’s until her death in the 1960’s when her shrine ceased to be a centre for distant delegations. Colson records, ‘By 1950 various less-noted prophets were attempting to share in her prestige by claiming to have received her authorization to serve as local deputies’ (1958 : 34).

Formally, the regional organisation in this cult is rudimentary, without an extensive chain of formal linkages, elaborate devices for control of delegates, or an effective hierarchy of command. Fluctuations in the reach of particular major prophets or shrines are apparently meteoric. Diffuseness, rather than boundedness, is a characteristic of their catchment areas for the visiting communal delegations or minor prophets, and the cult thus lacks any culturally defined regions like the de jure territory of the Mbona cult. Indeed, the differences in culture between Tonga and their Shona neighbours in another higher rainfall zone represent no barrier to Tonga use of Shona spirit-mediums as prophets: some Tonga delegations from the lower rainfall zone supplicate with the Shona mediums for rain.

What the prophet cult has is a region (or regions) of the de facto kind. It is characterized by the flow of cult traffic, along with dependence for ritual services: a vague hinterland relies on the cardinal points in a central area. These cardinal points are represented by the prophets or shrines that become the focus of the widest communal traffic in the cult. Significantly, the delegations go from the lower rainfall zone’s communities to the cardinal points in a higher rainfall zone, never downwards to the lower rainfall zone’s shrine or prophet. It is a regularity observed in certain other cults also, such as the High God cult which I discuss in chapter seven. The directional cult traffic, flowing along with other trends of migration, carries forward the interdependence between people of different climatic or ecological zones, and a ritual region overlaps or cuts across these zones. Of course, not all cult regions are cross-zonal, as Marx argues for South Sinai in chapter two. However, I must make one further comment first, before I can discuss his argument.

The present sites of major prophets are central places more accessible for a widespread, heterogeneous clientele. Nowadays, Colson reports, ‘the most powerful set up their headquarters on the railway and bus routes rather than in the high rainfall zone’. In that zone, for the time being therefore, it is a prophetless shrine, Monze’s, which serves the communal traffic as a cardinal focus. I infer that despite the diversification in the country at large, cross-zonal interests do continue to underpin ritual centrality and stabilize the prevailing direction of the communal traffic. Even more, the patterns of cult traffic themselves have a resilience which makes for continuity through change.

The ‘Correspondence’ Theory

So far this discussion has explored problems which arise in studies of African cults. Others that Turner would regard as associated with ‘historical religions and complex large-scale societies’ must be considered now. There is a major disagreement in approach to religious organization and ideologies, and some contributors to this book are closer to Turner’s views than others. The disagreement appears most sharply, perhaps, in the studies of Islamic pilgrimage and marabouts’ cults by Marx and Eickelman. Not surprisingly, at the very nub of it lies a classical theory, Robertson Smith’s ‘correspondence theory’, and a long anthropological tradition stemming from him via Durkheim. The theory asserts a correspondence, in Eickelman’s terms, ‘between symbolic representations of the social world and patterns of conduct’. By developing Robertson Smith’s fine insight into the ‘community of the god’, Marx supports the theory. Eickelman rejects it, on the basis of Moroccan data, in order to get a better grasp of the ideology and practice of maraboutism in different historical contexts. Marx concentrates on the interests represented in Bedouin pilgrimages and symbolised by their marabouts and tombs. The issues are critical for the analysis of regional cults elsewhere. Hence Thoden van Velzen, van Binsbergen and I explicitly debate them also. However, here the disagreement is best appreciated against the background of a single historical religion and in two studies which advance our immediate discussion of Turner’s conclusions.

The ‘community of the god’ is a conception of boundedness, within the exclusive domain in Turner’s terms. Membership in the ritual congregation is on a closed basis; its members share rights in resources, recognition of their vital interdependence, or a concern with the maintenance of a group. The correspondence theory suggests that their cult’s spiritual subjects (i.e. marabouts or patron saints) and material objects (tombs, shrine buildings, shrouds and other ‘paraphernalia) stand for something else: there is a symbolic representation — Marx would go so far as to say ‘a very precise image’ — of particular interests (in the case in point, territorial interests). It fits Turner’s understanding of the exclusive domain, also, that the ‘community of the god’ has its own shrines, the foci of segments, in central locations valued for communal control of crucial resources. After all, the contrary — the peripherality of shrines — would express and foster the tendency towards universalism, openness, and emanicipation from the community (Turner 1974 : 193f).

Thus Marx observes the following about the social unit mainly involved in communal pilgrimage among the South Sinai Bedouin: ‘The tribe claims not so much to control a clearly bounded territory, but defined points in it and paths leading through it’. Accordingly, he finds the communal pilgrimage shrines on routes, by water points and at cross-roads that are highly valued for their strategic importance in trade and pastoralism. His evidence is best, and thus he concentrates, on one of two clusters of shrines. It is the one confined to the very heart of South Sinai, with its shrines on or near the main east-west passage through the mountains. These shrines, sited close to the edge of what a tribe claims as its own, are centralized at points where tribes meet or divide, rather than right by the more inaccessible settlements recently built as fastnesses in the mountains. Each shrine, except the peninsula’s most senior one (Nebi Saleh which is near Mount Moses, that worldwide pilgrimage centre for Moslems, Christians and, nowadays, Jews) serves a single tribe and its sections as a central meeting place for communal ritual. Annually, it is a distinct social unit, the section or tribe, that sponsors its own occasion: members share their animal sacrifices in the name of the one, universal God (the marabout is an intercessor, not a lesser god) and create commensal bonds with each other and their guests at the shrine. When the five main tribes of the mountains all make communal pilgrimages to the same shrine, Nebi Saleh, they do so in turn, on separate occasions. For some time, however, even this shrine has had a narrower reach. Communal pilgrimages are now held there only by the largest tribe, the Muzeneh, which of course asserts claims to the peninsula’s most central points and the senior shrine itself. Apparently, the change took place before the Israeli occupation ended smuggling and thus altered the value of passages and intertribal interests.

Marx surmises

‘that the location turned this tomb into the central meeting place of the Bedouin of the mountains; it is situated on the cross-roads of the major east-west and north-south mountain passes, and close to water. In view of the great importance of smuggling in those days (pre-1965), each tribe attached major significance to its rights of passage through the mountains, as well as to co-ordination of activities and maintaining peaceful relations with other tribes’.

Having gone with Marx on pilgrimage to the top of Mount Moses, I am tempted to pursue a wider concern. Cult regionalism is not tribalism writ large. Marx is himself very frankly puzzled by some aspects of the shrines and their significance for Bedouin — in my view, rightly so, because these aspects challenge him to break the frame of his analysis. Furthermore, they go right to the crux of our discussion of the exclusive and inclusive domains in relation to regional cults.

One shrine with its own marabout, shroud, and tomb is enough, at least for the purposes of a single section or tribe as a ‘community of the god’, and from the viewpoint of a correspondence theory. More than one is too many, and several differentiated ones for a certain tribe alone and none of the others does not fit at all. Admittedly, Marx’s understanding of marabouts and tombs goes beyond Robertson Smith’s insight into the religious representation of boundedness. Marx perceives that an enshrined marabout has an inclusive aspect also, ‘a second face’ so to speak, just as ‘tribesmen reserve certain rights in territory for themselves, but ... other rights are expressly opened up to all Tawara [literally, ‘of the Mount’, i.e. Sinai Bedouin collectively] on a mutual basis, i.e. rights to pasture, drinking water and, without prejudice to the tribe’s interests, passage also. However, while this perception of correspondence reaches the common denominator in the general run of instances, it stops our understanding short. Left more of a puzzle is the overall configuration of these shrines and marabouts, which is not a correlate of the pragmatic interests of Bedouin qua tribesmen. What is the significance of the differentiation of cult centres and their more universalistic aspects? How does this relate to their distribution in space, to cult topography? And what does all this imply about the cult itself?

Marx leads us a good part of the way towards the answer, despite the burden of the correspondence theory. He unpacks the symbolic significance of the three marabouts, including the cult’s senior, whose shrines at the geographical heart of the peninsula, so strategic in its mountains and passages, form an innermost cluster around the worldwide pilgrimage centre on Mount Moses (Jebel Musa) and the Christian monastery of Saint Catherine. His interpretation leads me to suggest that this innermost cluster lays down a central configuration in the cult’s topography, and it is defined by the cult’s cardinal orientation. Nowadays, with the largest tribe as hosts, communal pilgrims go from Faranja to Nebi Saleh to Nebi Harun (see Map I in chapter two). Each shrine, as a station in the pilgrimage circuit, has a positional significance, but all together convey the configuration’s pattern. In space it is a movement towards Mount Moses (the peninsula’s holiest place for individual pilgrims, whose holiness the Bedouin compare to Mecca’s) and the monastery (by which the shrine of Harun, the priest Aaron, is fittingly sited). Symbolically, there is an increase in inclusiveness, moving from the most particularistic and tribal marabout, the host pilgrims’ tribal ancestor Faraj, to the senior marabout of the region, the pre-Islamic Arabian prophet (some say, another tribe’s ancestor) Saleh, and last to the most universal figure, Moses’s brother the prophet Harun. Nowhere else is there a repetition of this pattern, just as nowhere else is there a focus for the traffic of individual pilgrims that is comparable in its holiness to the region’s centrally sited holy place, on top of Mount Moses. To have considered individual pilgrimage at length along with the communal would have taken Marx well beyond the limits set for a single essay. But allowing for this limitation, the point here applies to both kinds of pilgrimage. On the whole the pilgrim shrines are central, rather than being instances of ‘sacred peripherality’, in Turner’s terms (1974 : 195); yet neither in organization nor ideology does the cult replicate the rest of what might be called ‘Bedouin society’. The cult has its own cardinal orientation, and this is towards the greatest inclusiveness at its very centre. Moreover, without any permanent staff and for both the individual and communal traffic, a nodal organisation is sustained overall through ritual activities. Here it is ‘sacred centrality’ which expresses and fosters the tendency towards universalism and openness (cf. Turner loc.cit., on Mecca).

Whereas Marx casts light on enshrined marabouts among Bedouin, with their characteristic egalitarianism or rather, subtle, unformalized differentiation, Eickelman illuminates the enshrined along with the living marabouts based in a Moroccan town, Boujad, where an elite is culturally recognized and, even more, legitimized through maraboutism and the notion of baraka or grace. Like Marx, Eickelman recognizes aspects of maraboutism which, taken in isolation, would support a correspondence theory’s one-to-one correlations. However, Eickelman’s data compel him to take account also of disparities which do not fit a correspondence theory whether it be, as he demonstrates, the version of Robertson Smith, Gellner, or Shils. Eickelman observes:

‘Maraboutism is especially linked to two key concepts through which Moroccans make sense of existing social arrangements: obligation (haqq) and closeness (qaraba)’.

With these concepts, some’Moroccans draw an analogy, man is to God as man is to man, which makes sense of both relationships in particularistic terms. There is a flow of benefits in each, and it is contingent upon specific bonds: the greater the obligation and the closer the bond, the greater the flow of benefits ’ (and conversely also, of course). Such reasoning, implicit in belief in marabouts (with the benefits of grace or baraka contingent upon closeness to God), is virtually the correspondence theory in a folk version. It is a great strength in such a folk version, and a crippling weakness in analysis, to absorb differences and give them a semblance of similarity, irrespective of varying historical contexts. Eickelman’s analysis grasps the differences and contextualizes transformations recognized by the people along with others they do not, and perhaps cannot, recognize.

As he shows, change takes place at different rates and with more radical consequences in certain parts of the Sherqawi lodge’s region. Away from town and the regional pilgrimage centre, in tribal sections or rural local communities believers in marabouts continue to seek dyadic bonds with members of a town-based elite. Partly through local feasts and commensality, the aim still is to put under obligation the living marabouts or marabouts’ descendants who come on visits to their clients’ communities. Moreover, some tribal sections are still able to insist, despite opposition from townsfolk, that their annual pilgrimage to the town centre must be an occasion for animal sacrifice, public feasting, commensality and all that this implies in the creation of specific bonds of obligation and the maintenance of covenants. Against such continuity runs a counter tendency which is most apparent at the centre in town, though it is of consequence elsewhere also. Offerings are converted into cash by Sherqawi visitors and the caretakers of major Sherqawi shrines. Moreover, whereas in the past marabouts and the economic and polical elite were virtually one and the same, living marabouts are now few, and not of the Sherqawi elite that has contemporary political and economic importance. Furthermore, many of this Sherqawi elite now dissociate themselves from maraboutic enterprises and ‘seek to redefine the activities of some of their kinsmen and ancestors in the light of the formal doctrines of reformist, modernist Islam’. Thus along with a tendency still most evident in the hinterland of the region, Eickelman points to a counter-tendency which is foremost at the centre, though not restricted to it. The counter-tendency is to favour mediation or the relaying of grace through an enshrined marabout, rather than any living person, and even further, to turn away from the personification of grace towards formal Islam which is universalistic and thus ‘requires no direct analogy with the nature of the local social order’.

Elitist versus Egalitarian Regional Cults

At the risk of being taken to task for a lack of consistency — in the light of my general criticism of dichotomous typologies and Turner’s in particular — lam tempted to make use of one for comparative purposes here: elitist versus egalitarian regional cults. Ralph Waldo Emerson’s homely adage, from his celebrated essay on Self-Reliance, urges me on: ‘A foolish consistency is the hobgoblin of little minds’. I find the typology useful to clarify certain patterns and to show how their permutations are regular in the four cases mainly considered so far. The first kind of cult, the elitist, is characterized by processes which bring an elite and its public into dialectical opposition over the relative emphasis given in the cult to the exclusive or inclusive domains. Our examples of the Mbona cult and the Sherqawi maraboutic lodge illustrate this, and together represent an elementary permutation: the pattern in one appears in the other in reverse.

Briefly, to begin once again with the Mbona cult, the public appeals through its representative — so centrally placed in his extra-territorial sanctuary — to a conception of an undifferentiated society. It turns to universalism without ethnic bounds in the image of the black Jesus, whereas the elite of cult principals asserts its tribal authority and is particularistic in its appeal. By contrast in the case of the Sherqawi lodge, it is the public in the rural local community, the tribal section and elsewhere which appeals to greater particularism and continues to seek ‘closeness’ to a living person with grace or baraka as well as commensal bonds through shared sacrifice at an enshrined marabout’s holyplace. The centrally placed Sherqawi elite, on the other hand, now turn to universalism in the form of reformist Islam or they seek to free the offering of donations from commensality and its association with boundedness and the most particularistic oneness.

Underlying these inverse patterns is one or perhaps several regularities. In the elitist cults the emphasis on the inclusive domain is increased from the cult centre, rather than from elsewhere. Who fosters this increase depends on who is in control of the centre. On the one hand, the public or its representative fosters it where the centre is an extra-territorial one, under a religious authority and beyond the elite’s. Here the Mbona cult is the case in point. On the other hand, the increase comes to be fostered by members of the elite where the religious centre is the political one under the elite’s own control. Further studies of elitist regional cults are needed to clarify what are the limiting conditions for this regularity. But the point that must be stressed is that this is a regularity of cult organization and ideology; it is not a mere reflection or replication of some other social order. Religious change from particularism to greater universalism has its own momentum rather than being a mere correlate or after-effect of other transformations.

Constant in both these cases of elitist regional cults is the stability of the centre. In both this remains in a fixed location and is somewhat like a stationary capital, providing an established point of reference around which cult relations refocus. There is an alternative in which the cult centre is still the cardinal point for refocusing but itself shifts in location and is somewhat like the mobile headquarters of an army on the march, ever ready to be pushed forward with each major advance of the cult. This alternative, especially important under certain conditions of cult expansion, still correlates central control or cult centrality with the greater emphasis on the inclusive domain, as shown by Evans-Pritchard (1949: 70 f) in his classic account of the Libyan based Sanusi Order. Emrys Peters is working on a detailed reanalysis of the Order’s development, which will illuminate our discussion further. Here the comparison between elitist and egalitarian cults has to be explored on the basis of our four cases in order to complete a view of these as one whole set.

Our cases of egalitarian regional cults are the Tonga prophet cult and the South Sinai maraboutic cult. Each is characteristically free of any political elite with special ritual roles in the cult. The South Sinai case is a straightforward instance of a familiar regularity in that the cult’s stable centre is the focus of an increasing inclusiveness. The difference here is a lack of any dialectical opposition between recognised protagonists of the different domains. Perhaps less straightforward and thus more revealing is the Tonga case. Not only is the location of a given center variable within the more enduring focal area of the higher rainfall zone but cult centrality itself is also intermittent, somewhat ambiguous and problematic. Nowadays formerly peripheral points attract prophets and they scatter away from established shrines. Seen in relation to the other cases, it suggests the hypothesis that the greater the central instability, the more cult peripherality comes into its own for refocusing a greater emphasis on the inclusive domain.

So far all of my comments about this set of cases have been made with a general condition, common to them all, left implicit. It must be made explicit now in order to bring the next, contrasting set of cases into relief. Briefly, none of the first are clearly hierarchical whereas four of the second are; as will be seen, this poses further problems for analysis. Along with the lack of hierarchy goes a variation from cult to cult in the degree to which there is a unified ranking of cult shrines and holyplaces, although none rival the more formalized ordering in some of the second set’s cases. The variation is as follows. At one extreme is the Tonga cult which is without overall ranking but whose prophets and shrines are distinguished according to their participation in different orders of relations. Next comes the South Sinai marabout cult with its one acknowledged senior but somewhat ambiguous or unranked standing for other shrines. After these egalitarian regional cults come the two elitist ones, the Mbona cult and the Sherqawi lodge in that order. The regional medium of Mbona alone speaks for the whole of his region, and the lesser territorial mediums are restricted to narrower local constituencies. Finally, apart from the local maraboutic tombs which are points of domestic pilgrimage for women and children, the Sherqawi lodge has two grades of shrine within the pilgrimage center of the town of Boujad. Each quarter has its own shrine for rural and urban pilgrims, and above this grade is the one main shrine for them all, that of the lodge’s founder Sidi Mhammed Sherqi.

Hierarchy and the Waxing and Waning of Cults

To understand the importance of hierarchy and how it develops along with other cult transformations we must now consider our second set of cases. Our analysis of the waxing and waning of cults must be extended to cover a further range of problems, and shifts from non-regional to regional cults have to be explained. Already our discussion has moved towards the third of Turner’s conclusions, which is about cult transformations, and it helps to clarify our views for us to examine this conclusion explicitly, at this point, with further light from the rest of our cases.

Turner argues that ‘Pilgrimage centers, in fact, generate a “field” ’ (1974 : 226). Around pilgrimage centers a process of oscillation takes place or, more forcefully, gets its impetus: shrines, once peripheral and apart from ‘politico-economic centers’, attract people who make them structurally central; and then, over time, they revert back to peripherality. The model of the perpetual pendulum has no hold here, however, because it is a cumulative process, in Turner’s view. He considers that ‘pilgrimages sometimes generate cities and consolidate regions’ and yet ‘they are sometimes also the ritualized vestiges of former sociopolitical systems’ (1974 : 227). In other words, “the field” generated by pilgrimage centers is, at once, more and other than any contemporary ‘sociopolitical system’ with which it is, in fact, in a dialectical relation: increasing boundedness bears within itself the seeds of its own destruction, and conversely. Yet the question which has to be answered here is this. Across which boundaries, and in which respects, can a regional cult extend its hierarchy and yet still assert the kind of boundedness which, by its very nature, the hierarchy requires?

Turner’s own classic studies of the Ndembu cults of affliction, as reconsidered by van Binsbergen in a wider context and within an historical perspective, open the way to an answer. The first step that van Binsbergen takes is to free the concept of cults of affliction from any necessary bondage to the unitary social system. It is a radical departure from Turner’s view which left in the background crucial continuities in the ritual field:

‘But, by and large, the function of maintaining the unity of the widest social unit, the Ndembu people, devolves mainly upon the ritual system, although the ritual system spreads even wider than this’ (Turner 1957 : 292 my italics).

Turner’s view is tied not merely to Ndembu but, more fundamentally, to a single tribe or society taken as a ritually integrated whole. Yet successive cults of affliction sweep like waves of fashion across Western Zambia’s cultural and tribal boundaries. Hence van Binsbergen suggests that

‘The non-ancestral cults of affliction represent an attempt to come to terms (both conceptually and interactionally) with the reality of extensive, inter-ethnic, interlocal contacts’.

It is no paradox, however, that van Binsbergen’s observations, even more than Turner’s, illuminate the significance of local factors in the cults. Elsewhere I have argued (1971 : 318f) that Turner’s evidence does not sustain his conceptual model of rituals of affliction. According to Turner’s model, individuals associate in these rituals on an ad hoc and ephemeral basis; their community is the community of shared suffering, no other; they form a congregation, as van Binsbergen puts it, ‘in a pattern that cuts across, rather than reinforces the structure of distinct local communities’. Turner’s evidence, on the other hand, shows that a major performance of a ritual of affliction has primarily an invited congregation whose members nearly all have prior ties of one kind or another with the sponsors. The occasion provides an index, in effect a Who’s Who, of people and relationships important for the sponsors, but there.is no ritualization of a structure of localized groups, their divisions or boundaries. This kind of indexical occasion mobilizes as a congregation the interpersonal sector which is dispersed around a village, rather than the village itself in ritual isolation. Thus it is not the kind of event which emphasizes virtually random inclusiveness or participation ‘from all over the Ndembu region’ (Turner 1957 : 295). Here van Binsbergen examines the local organization of the cults more closely than Turner does, and thus establishes that, at least among the Nkoya of Western Zambia, cults like those of the Ndembu are fragmented into numerous, small and unstable, localized factions, each with its own leader, distinct songs, and peculiar paraphernalia. Not that van Binsbergen regards merely the politics and economic transactions in the cults; he is careful to bring into perspective also the pull of belief and liturgy in the healing ritual.

The next step van Binsbergen takes follows from his historical approach. He distinguishes types of cult of affliction and examines their development. Already familiar is the non-regional type, which covers the Ndembu examples also: the cult has its pecular emblems, its own highly specific idioms and subjects, and it is widespread, perhaps with many local variations, among a multitude of culturally different people. What it lacks is any central place, hierarchy, or overall organizational focus. Only the regional cult of affliction has these features along with the others and, significantly, even more of a conceptual emphasis on inclusiveness, with a shift towards greater attention to a High God. To explain the transformation, van Binsbergen traces a creative process of religious innovation, with its taproot continuously drawing on (or sloughing away) the transcultural, general idiom of the earlier, but still current, non-regional cults. He rejects an ‘imitation theory’, which reduces the essential dimension of the change, and makes it depend simply on the existence of a Christian church as an organizational model to be copied. Moreover, he shows that innovation itself becomes a proof of spiritual grace: whereas followers of any leader in a non-regional cult regard him as a mere transmitter of a received idiom, the regional cult’s members attribute its basic design to their founder’s prophetic visions and insights. In fact, much of the cult innovation is on a pragmatic, ad hoc basis. It has to be understood as a gradual series of choices in response to growing acceptance or rejection of the cult by a wider public. Furthermore, it is not an evolution in a single direction, and a cult may lapse from the newer type into the older one and become non-regional.

How does one cult — and not another — firmly establish a hierarchy, with secure centralized control of cult assets and services, while expanding the regional catchment area over town and country and the span of cult membership across socio-economic strata and ethnic groups? Detailed historical comparison is necessary for the explanation, and van Binsbergen compares the career of one cult, formerly regional, with another that is now vast, multi-ethnic and still expanding not only in Zambia but in Botswana also: respectively, these are the Bituma and Nzila cults. The relative placement and mobility of the founder’s own group counts along, of course, with the founder’s capacity to mobilize his fellows in it. Nzila’s founder initially appealed to Luvale immigrants like himself and even beyond them to others who also came in a great influx from Angola into an area of Zambia with towns of major economic and political importance. With the increasing penetration of the immigrants went the greater spread of the cult. At first, the diagnosis and final treatment of member’s afflictions remained (with the possible exception of the limited autonomy allowed a single deputy and branch in another district) the monopoly of the founder and his designated heir. They moved the cult’s main shrine to a central place right by one of the two major towns and thus secured a suitable headquarters for urban as well as rural supplicants. Eventually, other branches were also allowed some autonomy in healing, but central control was stabilized by the careful registration of all members, ‘by the Annual Convention at the cult’s headquarters, by the [centralised] distribution of essential paraphernalia, and by formal examinations concerning the cult’s beliefs and regulations’. Not only did this result in an idiom quite distinct from that of any non-regional cult of affliction — and thus made it harder for the new cult to lapse into the old cultic background — but it also established, van Binsbergen argues, ‘clearly recognised principles of legitimation, controlled from headquarters, outside which no cult leader pursuing the Nzila idiom could claim ritual efficacy’.

A more illuminating contrast could hardly be found than the career of the Bituma cult. Having failed from the start to convert many of his fellow Angolans, the founder, himself an Mbunda, concentrated his appeal on rural villagers, mainly Nkoya. His cult became trapped in their relative poverty, their hinterland’s local power-blocks, and the limitations of their labour migration to distant towns where they never gained much of a foothold. Anchorage in their district stultified the further expansion of the cult’s region. The district had only a small township as its administrative centre and was ethnically more homogeneous as well as economically less differentiated than the breeding ground of the Nzila cult. When Bituma’s founder died, the cult fragmented; it became little more than other non-regional cults. Never did it develop, in van Binsbergen’s terms, ‘an adequate structure through which the founder’s charisma could be routinised and channelled without becoming dissipated or usurped’.

In both cases van Binsbergen sees a constant factor as foremost: the structural characteristics of the immediate arena in which the cult arises. His argument is that the viability of the cult is contingent upon these characteristics above all and that the structure of the cult has to be commensurate with them.

It is an argument which Thoden van Velzen takes a stage further in seeking a materialist explanation of the waxing and waning of regional cults in Surinam. Just as waves of cults of affliction sweep across Central Africa, so do High God cults come and go in Surinam among Bush Negroes and, at times, among Creoles also. Like van Binsbergen, Thoden van Velzen considers it essential, therefore, that the cultic background out of which a regional cult emerges and into which it lapses be given its full weight in analysis. But for Thoden van Velzen even more problematic, and thus more central in his argument, is the accumulation by the cult of valuables or assets: How does such accumulation affect the survival and raison d’etre of a cult hierarchy and, even more fundamentally, how does the overall religious transformation relate to change in modes of production and distribution? His argument also contributes to other, perhaps even more general debates, because his main case is about a cult, Gaan Tata, which invites comparison with cargo cults, that favourite concern in dispute about the rationality or irrationality of religious belief and practice. Gaan Tata is, in a sense, a cargo cult in reverse. In it, too, the moral redemption of men, purity, cleansing from sin, all depended on waste, and the waste was on a grand scale: great heaps of European trade goods — household utensils, Victorian bric-a-brac, mantlepiece decorations, gold chains, shoes, plastic ware — were left to rot in dedication to the High God (Gaan Tata). The sudden, unexpected enrichment of the Surinam interior’s boat entrepreneurs, due to the discovery of gold which brought with it a deluge of imported goods quite without precedent, gave the cult its initial opportunity and basic concern. It was not that the cult demanded, as some millenarian movements do (cf. Douglas 1970 : 137), that people reject their own material values or those of Europeans. The wasted goods were quite highly valued imports, as in a cargo cult. For that very reason, they became God’s business: like other new interlocal relations, such new riches, to be made in river transport across communal boundaries, were not to be left to look after themselves, but were made sense of, and controlled, religiously.

If, as Douglas suggests, cargo cults are ‘cults of revolt against the way the social structure seems to be working’ (1970 : 139), then we may say that in reverse what we find is a ‘cult of regularization’ (cf. also Moore 1975 : 219f). A cult of regularization enhances economic inequalities, rather than levels them; and it legitimizes a new status quo, rather than a restoration of the old. Gaan Tata is such a cult. It hid its waste, from outsiders especially, in a secret bush shrine. It reduced the circulation of European material goods and limited them even more to an elite, rather than providing, after the fashion of a cargo cult, the ritual means to bring the goods flowing in from the outside. Moreover, it redirected the circulation away from the main European centre, Surinam’s capital, on the coast and towards the cult’s own headquarters in the interior. Fittingly for a cult of regularization, its headquarters was sited at a centre of current and continuing political importance, the capital of the Paramount Chief (Gaanman) of the largest Bush Negro tribe.

Thoden van Velzen points out:

‘As part of Gaan Tata’s commandments, the [boat] entrepreneurs were given a set of standards that proved their usefulness in contacts between Bush Negroes from various areas and with different cultural backgrounds; the cult, for example, gave religious sanction to peacefulness: even the shedding of a single drop of blood could arouse Gaan Tata’s wrath ... Significantly, any boatsman who established a good relation with the Gaan Tata oracles through timely presents and acts of deference — soliciting help in case of illness — could rest assured that his reputation would be protected [from accusations of witchcraft]’.

He argues further:

‘The cult was directed at eradicating an internal evil, witchcraft, that was felt to dog the steps of the nouveaux riches’.

Hence the cult introduced an alternative to the customary conciliatory ritual for the dead: one treatment for the witches and sinners, another for the “respectable”. Sinners or witches were believed to die from Gaan Tata’s wrath, so no elaborate death rites for them. Their legacies, polluting to their relatives, were brought as “God’s cargoes” to the cult’s priests, who gave back a small, cleansed share, kept part for themselves, and left great heaps dedicated to Gaan Tata. The relatives and local community made a death the occasion for costly celebration among themselves — the customary death rites — only when someone was declared, after a post mortem inquest, to be “respectable”.

Thoden van Velzen argues that the career of the cult was closely geared to radical economic change introduced from outside the cult region. The boom in river transport entrepreneurship produced along with wealth a qualitative change in interlocal and cross-cultural relations which was essential for the cult’s overall centralization and effective hierarchy. Then came a drastic economic slump when the interior’s extractive industries, gold and Balata, collapsed. Not long afterwards the cult itself fragmented into a number of parochial cults, without any central control or uniform ritual practice and dogma. The cult’s career, until the next radical economic change, took the course of what might be described as a downwards spiral. The more the priests retrenched through short term solutions to their own pressing religious and organizational problems, the less was the cult able to respond to the current concerns of its public. Once a new labour elite emerged with the next radical economic change, a different regional cult began in opposition to the remnants of the old one. The opposition was based in a rival political centre within the old cult’s heartland, and the new cult, like the old in its heyday, regularized and legitimized the wax of inequality. Protest and revolt there was, perhaps, but in defense of new privilege: once again a fresh cult gave the newly prosperous members of a rising labour elite protection against witchcraft and also a fresh imprimatur in the form of special certificates to their own innocence of witchcraft.

A key point must be kept in sight, given the stress in Thoden van Velzen’s argument on radical economic change. Yesterday’s cult of regularization becomes today’s anachronism, not merely through external change or radical discontinuities in the milieu of the cult but through cumulative change in the cult itself. Indeed, every regional cult builds up a momentum of its own over time which has to be taken into account in explaining its response to radical economic change or any challenge to the viability of its regional organization. That is why in my own study of a High God cult, southern Africa’s cult of Mwali, I pay special attention, as does Thoden van Velzen, to the underlying orientation of the cult’s leadership and to endemic instability within its organization. The question is, How far does this orientation alter over time, and what directions does such instability take regularly as well as in sudden, perhaps unprecedented shifts?

Historical evidence and my own observation shows that from precolonial times to the present there has been a continuity in orientation within the cult of Mwali. The central concern of the messages from the cult’s oracles was and still is to conserve order in the world and maintain the welfare of the land, its people and their economy. It is not surprising that such conservatism is fostered by a cult with a certain, lasting fixity in its hierarchical centralization. What is surprising is the combination of such fixity with instability in the coverage and definition of regions, impermanence in the sites of oracles, variability in priestly succession and great fluctuations in affiliated congregations and their staff. On the one hand, this High God cult has a small, limited number of regional oracles that are ranked in a stabilized, unified order according to their restricted distribution within a central heartland. Similarly, the ranks of its staff form a hierarchy with relatively exclusive criteria for recruitment: the higher the rank, the narrower and more exclusive are the criteria, and recruitment to the inner circle of priests is on the most exclusive basis. On the other hand, its land shrines lack an overall pecking order; they are widely dispersed and highly variable in standing, a multitude without a known size. Like their congregations, they rise and fall in importance as foci of ritual collaboration (some disappear completely), and pass through what I regard as three grades — local, interlocal, and regional.

Significantly, this cult is one of those to which Turner seems to refer when he suggests that earth cults stress inclusiveness, rather than ‘selfish and sectional interests and conflict over them’ (Turner 1974: 185). Yet the cult fits no polar extreme in Turner’s terms. Admittedly, never does its ritual offer a straightforward representation of the various political divisions within its vast domain (see Map 1). But it does thrive on indexical occasions — on the very stuff of micropolitics — when the relations between competitors are put to the test of ritual collaboration or avoidance, when the scale of local commitment and investment in the cult is proved, when still unresolved territorial and political ambiguities are given a somewhat anticipatory definition, heralding new power divisions. At the same time, its ritual, characteristically rich in symbolism with transcultural meaning, memorializes events that are broadly significant for every congregation, be it mainly Kalanga, Karanga, Venda, Ndau, Khurutse, Ndebele or any other. Moreover, its theology directs attention to the macrocosm, the order beyond that of the congregation or any single community. I show in my essay that the cult’s macrocosmic conceptions ‘are a significant factor in behaviour because they are of such a kind that communities can continue to define their broadest consensus through them irrespective of their differences, hostilities and competition’. With its capacity to override or encompass quite marked cultural differences, the cult continually admits newcomers irrespective of their ethnic origins. Thus highly sensitive and responsive as the cult is to micro-political change, it is no less concerned with ‘wider bonding ... disinterestedness and shared values’ (Turner loc.cit.) Indeed, it is dynamic tension between inclusiveness and exclusiveness which gives the cult much of its momentum and renewed viability from one historical context to another.

It may be, as Turner suggests, that studies of African cults of the earth, most strikingly the Tallensi case, tend to have to say little about ‘factional conflict’ (idem). But the cult of Mwali can hardly be studied adequately without a discussion of politics and policy making in various arenas, from the most petty to one grand enough to embrace the cult’s vast domain across southern Africa. Indeed, it has been much debated in the literature on the cult, though mainly from the viewpoints of white settlers, how the cult responded in crises, especially during an early war against white rule in 1896. I suggest that, even during crises or rather then most of all, the cult has been constrained to favour political compromise in its widest policy — its cardinal oracles make pronouncements which do not commit the whole cult to one side only during a struggle — and that this balancing has been in response to the diversity of peoples and interests which the cult must encompass. In no way does this suggestion deny the cult its part in rallying moral sentiment against exploitation and the abuse of power: some of its songs ring with moral outrage against alien rule; its oracles have urged resistance against the inroads of a cash economy; they have also warned about the dangers of party politics. Rather this suggestion takes account of the fact that the cult’s ultimate dependence is on voluntary consent; its appeal is to the most general consensus, which it may focus but cannot invent.