Rob Maslen

‘Towards an Archaeology of the Future’: Theodora Kroeber and Ursula K Le Guin

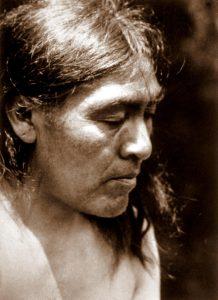

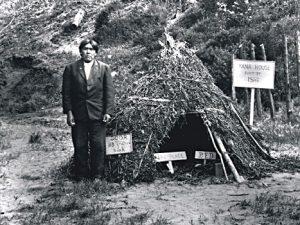

On 20th August, 1911, an amazing thing happened: a man walked out of one world and entered another. He had walked further perhaps than any other man in history: several thousand years, by some people’s reckoning, from the Stone Age to the Age of Steam, from ‘Inside the World’ (as the Kesh would call it) to a place ‘Outside’ it, from the country of his people, the Yahi, to the country of the twentieth-century Californians.[1] He was infected by the experience; within five years of his emergence from the wilderness he died of tuberculosis, like so many other indigenous Americans. Nobody knows the man’s name; he kept it secret because names were not to be lightly spoken in his culture.[2] The name he was given by the strangers who befriended him was Ishi, which means simply ‘man’ in the Yahi language. Fifty years later, a woman called Theodora Kroeber wrote a book about him, Ishi in Two Worlds, (1961); and this book haunted her daughter, Ursula Kroeber Le Guin, throughout her extraordinarily varied literary career. I would like here to consider a few of the ways in which Kroeber’s Ishi continued to make himself felt in the narratives of Le Guin; how he kept wandering out of his world into ours in different forms and different contexts from her earliest published stories to her mature works of the 1980s and 90s; and the questions about the relationship between our culture and other cultures, between the ‘civilized’ and the ‘barbarous’, the past and the future, as well as the tentative answers (usually couched in the form of further questions) he brought with him.

In the course of his lifetime Ishi lived in two different places he called home. The first was the country of the Mill Creek Indians, as settlers called them, which occupied the space between two tributaries of the Sacramento River, and from which he emerged in the first fifty years of his life only to mount forays into adjacent territories as he and his family found their traditional food sources rapidly dwindling. The second was the University of California’s Museum of Anthropology in San Francisco, where he lived out his last five years, emerging from the city only to make one last brief trip to his former home. Kroeber’s account of Ishi’s sojourn in the museum is extraordinarily moving in its evocation of the loneliness of the last stages of his life. His people had been wiped out, for the most part by the guns of settlers, but also by the diseases they brought with them as a gift. His family – twelve individuals, reduced to five, then four, then none in the course of the decades – had survived in hiding for forty years after the rest of the Yahi people had been massacred – an astonishing feat of endurance. There was no one else left alive who spoke his language. From before he reached puberty there was no one left alive with whom he could have contemplated having a sexual relationship. He lived in the museum as a walking exhibit, demonstrating the skills of house-building, arrow-making, fire-lighting and shooting that had constituted his vital contribution to the community he came from, and observing with amusement and occasional wonder the bizarre behaviour of the new friends he found among the inhabitants of San Francisco. He spoke a unique mixture of the English and the Yahi languages, and he seems to have changed the lives of the people he met as profoundly as they changed his.

In Ishi in Two Worlds we are privileged to witness an encounter between two wholly different cultures – each one studying, each one studied – in the same small space at the beginning of the last century. Such a two-way encounter occurs a number of times in Le Guin’s writing, and it often takes place in an academic context. In her early short story ‘April in Paris’ (1962) a lonely twentieth-century scholar finds himself transported back to fifteenth-century France to meet his medieval counterpart.[3] In The Dispossessed (1974) a scientist from a society of anarchists finds himself trapped in a university run by capitalists, and gradually comes to recognize the extent of his isolation in this new environment. But in neither of these cases does the protagonist find himself as lonely and disoriented as Ishi must have done. Like Le Guin and her husband Charles, the medieval scholar is fluent in Middle French and Latin, and the scientist Shevek in The Dispossessed shares with his captors the language of physics. More acute states of isolation occur elsewhere in Le Guin’s work: the clone Kaph in ‘Nine Lives’ (1969), for instance, ‘a lost piece of a broken set, a fragment, inexpert in solitude’, who has lost eight-ninths of himself when eight of his fellow clones were killed in an earthquake;[4] the loneliness of the alien Falk in City of Illusions (1967), stranded on a broken world with no memory of where he came from. But Kaph shares the language and the technological skills of his fellow workers, and Falk is eventually given the chance to return to his home planet. For all their highly-developed sense of being cut off, none of Le Guin’s characters finds herself in a state of isolation as extreme as Ishi’s, except perhaps for a man and a woman in the first of her novels, Rocannon’s World (1966), published only five years after Ishi in Two Worlds. Le Guin’s other solitaries acknowledge this man and woman as their ancestors, and continue to respond to the problems they first faced in ever more complex variations on Ishi’s predicament.

The man is Rocannon, left alone on a strange world when his fellow scientists are obliterated in an instant by a bomb dropped by a faceless enemy. Like Kroeber, Le Guin conveys Rocannon’s isolation primarily in linguistic terms: ‘Mogien understood no word he said, for he spoke in his own tongue, the speech of the starlords; and there was no man now in Angien or in all the world who spoke that tongue’.[5] For Rocannon, as for Ishi, this linguistic isolation is irreversible: return is denied him, and he must learn to make what he can of the alien environment in which he has been stranded. In fact he makes it his own in a double sense. By the end of the book he has learned to call it ‘home’ (presumably in the new language he has been forced to adopt); but after his death, the League of All Worlds (of which he was an envoy) baptizes the planet as a whole with Rocannon’s name. This last development is an interesting one. Is the name of a non-native scientist, however thoroughly he has been naturalized, really an appropriate designation for a planet with a long history of its own? The name suggests not so much that the world has domesticated Rocannon as that the League of All Worlds has domesticated the world; and it suggests too that for the League the most interesting moment in a planet’s history is the moment when it loses its autonomy, when it settles into its humble place in interplanetary discourse. And what of the other occupants of the place Rocannon came to call home? The men, and above all the women, who made him welcome in their dwelling-places?

The fate of these nameless householders is hinted at in the prologue to Rocannon’s World, first published as a short story, ‘Dowry of the Angyar’, in 1964.[6] In it a woman called Semley, from the planet that will one day bear Rocannon’s name, appears out of the darkness between the worlds to reclaim one of the exhibits in a Museum of Anthropology, an exquisite necklace, and is observed with wonder by the anthropologist Rocannon. The fact that it is a necklace she has come to reclaim might be read as an allusion to Kroeber’s book. In the foreword to Ishi in Two Worlds Lewis Garnett elaborates on a metaphor Kroeber uses to describe the biographer’s difficult art:

This book, as the author herself says, is like an archaeologist’s reconstruction of a bead necklace from which some pieces are missing, others scattered. She puts together two necklaces: first, the story of a tribe that survived almost unchanged, along the streams of the Mount Lassen foothills, from what we call the Age of Pericles to the period of our gold rush; of its decay and its murder. The second necklace is the story of Ishi’s adjustment to the trolley-world of San Francisco – proof, as the author says, that Stone Age man and modern man are essentially alike.[7]

For the anthropologist Rocannon in the prologue to Rocannon’s World, Semley’s necklace is transformed from a museum exhibit into the fragment of a story to which he has no access – the story of Semley, which is what later prompts him to travel to her planet in his turn. In much the same way, Ishi invested the exhibits in the Californian museum with new meaning and new life – for instance, by objecting to the practice of leaving camping gear untended in a room that housed the dead (in Ishi’s world this might have resulted in unwelcome interference with the equipment by restless ghosts, no matter how completely the dead had been assimilated into the discourse of science).[8] Semley’s necklace comes to stand for the gap between the narratives favoured by different cultures and the ways in which encounters between these cultures may exacerbate the gap even as they seek to bridge it. For Semley the necklace has a value and a function of which the curators of the museum have no knowledge: she needs it as a dowry for her husband, an emblem of the status of her family. But unknown to her it has acquired a different function in a new cultural context since it was lost to her family in the distant past. It was exchanged with the voyagers by one of the races on her planet who privilege the values of barter over those of heredity; exchanged, in fact, for the very same starship that carried Semley to the museum. And as a result of this initial change in the valuation of the necklace, another change is brought about. Unknown to her, it has lost the function for which she sought it even as she travelled through space towards its resting-place. ‘The gap of time bridged by our light-speed ships’ means that she will return to her world years after her husband’s death; and with him dead, her friends aged, her daughter grown to adulthood, the necklace will no longer have any use as a dowry.[9] Instead it will acquire for her family the status of a cursed object, until it is returned again to Rocannon, who will eventually give it to his wife – a woman of Semley’s people – as a dowry. In the meantime, for readers of the novel it will perhaps acquire a further meaning still: it will come to stand for the deadliness of misunderstandings between cultures, and for the impossibility of returning to the precise historical point from which one has started.

Semley’s necklace becomes, in fact, a sign that changes its meaning in the space between past and present, like a word from a language that is no longer spoken which has been assimilated into a different tongue. The consciousness of such profound linguistic changes, which accompany and even bring about changes within communities that share a common language, is always present in the work of Le Guin; and for her, as for her mother Theodora Kroeber, the task of charting these changes – or recording a diversity of different understandings and ways of speaking within a text that is written in a single language, rooted in a particular time and place – is the principal problem that confronts a writer, whether she is an archaeologist or a novelist. Indeed, the language used by Le Guin herself has changed as her ideas have changed. This is most obviously the case with her use of the personal pronoun. In her preface to the 1989 edition of her essay-collection The Language of the Night, first published ten years previously, she explains the dilemma with which she was confronted when faced with her earlier essays:

In general, I feel that revising published work is taboo. You took the risk then, you can’t play safe now… And also, what about the readers of the first version – do they have to trot out loyally and buy the recension, or else feel that they’ve been cheated of something? It seems most unfair to them. All the same, I have in this case broken my taboo. The changes I wanted to make were not aesthetic improvements, but had a moral and intellectual urgency to me… The principal revision involves the so-called ‘generic pronoun’, he. It has been changed, following context, euphony or whim, to they, she, you, or we. This is, of course, a political change (just as the substitution of he for they as the correct written form of the singular generic pronoun – see the OED – was a political act).[10]

In the collection, the essay that is most seriously affected by this change in linguistic and ideological stance is inevitably the one that discusses her exploration of a genderless culture in The Left Hand of Darkness (1969): the celebrated essay ‘Is Gender Necessary?’.[11] In the 1989 edition of the collection, Le Guin prints the essay along with a commentary, as if it had been a text from a previous epoch that requires annotating to be understood by the modern reader. At this point the collection resembles an archaeological dig, the different layers or columns representing different stages of Le Guin’s development. The novel she describes as an attempt at an ‘archaeology of the future’, Always Coming Home (1985), is written in two languages: for the most part it is in English, but to overcome the ideological assumptions that are ingrained in that imperialist tongue she occasionally lapses into the language of the future, Kesh, to describe concepts that have no equivalent in ‘Western’ thinking.[12] In other words, Semley’s necklace initiated a linguistic revolution – a revolution that was carried on in The Dispossessed by the anarchist Odo, who invented a new language for her tender new-born society. In the same way, the relationship between the woman Semley and her male observer, Rocannon, foreshadows the revolution in Le Guin’s thinking about the relationship between the reader (or writer) who thinks like a twentieth-century man and the text that reaches towards other modes of being.

The prologue to Rocannon’s World raises another question that Le Guin went on to consider in greater depth in her later work: the question of how the writer’s perspective or philosophical stance affects her subject. Inevitably in a book about an unfamiliar culture the writer is likely to adopt a point of view that can be understood by the bulk of her projected readership; and inevitably such a point of view tends to obscure or distort the subject under scrutiny. Theodora Kroeber was acutely conscious of this problem as she tried to chart Ishi’s career. There was a danger, for instance, that the gaps in what was known about Ishi’s life would tempt the writer into irresponsible imaginative speculation, or that her readers – and she herself – might be tempted from time to time into allowing their contempt for a ‘primitive’ culture to colour their response to the story they were reading. Kroeber found some startling ways to avert such reactions. For one thing, she wittily records Ishi’s amusement at what he saw as the absurdity of the ambitions of white civilization – his dismissal, for instance, of aeroplanes and impressive buildings as inadequate and unnecessary copies of mountains and birds. For another, she keeps slipping Ishi into unexpected roles in the world of technology. ‘It is a curious circumstance,’ she writes at one point,

that some of the questions which arise about the concealment [of Ishi’s family for forty years] are those for which in a different context psychologists and neurologists are trying to find answers for the submarine and outer space services today. Some of these are: What makes for morale under confining and limiting life conditions? What are the presumable limits of claustrophobic endurance? What temperament and build should be sought for these special and confining situations? It seems the Yahi might have qualified for outer space had they lasted into this century.[13]

This unexpected juxtaposition of the close community of the Yahi with the close community of astronauts in space might almost have provided the seed for the idea of the crew of clones in ‘Nine Lives’, or the problems of forming a healthily cooperative society in a spaceship explored in ‘Vaster than Empires and More Slow’ (1971) or ‘The Shobies’ Story’ (1990). In Rocannon’s World, however, Le Guin had not yet found satisfactory solutions to the other problem confronted by her mother: the problem of making both her readers and her narrator receptive to cultural difference. Her account of the story-teller’s art in the prologue shows this:

In trying to tell the story of a man, an ordinary League scientist, who went to such a nameless half-known world not many years ago, one feels like an archaeologist amid millennial ruins, now struggling through choked tangles of leaf, flower, branch and vine to the sudden bright geometry of a wheel or a polished cornerstone, and now entering some commonplace, sunlit doorway to find inside a darkness, the impossible flicker of a flame, the glitter of a jewel, the half-glimpsed movement of a woman’s arm.[14]

The peculiarity as well as the wit of this passage lies in the fact that the archaeological metaphor applies not to the subject under examination by anthropologists in the museum, Semley, but to one of the anthropologists themselves, an ‘ordinary League scientist’ who went to Semley’s world and became part of its mythology. This is particularly odd when one considers that the prologue was originally a short story – one that concerned itself with the adventures of Semley, and made no mention at all of the adventures of an ordinary male League scientist. It is as if at this stage in Le Guin’s career, and in the history of science fiction, the only conceivable protagonist of a story must be a man who shares the cultural assumptions of his readers; the only conceivable objects of interest must be recognizable elements in the progress of ‘Western’ culture, the wheel that was of no importance to the indigenous peoples of the New World, the cornerstone of a stone-built house, never the baskets or dancing-clothes of Ishi’s family. Le Guin repeatedly states in her critical writings that that in those days – in the days when she penned Rocannon’s World – she had not yet learned to write from a woman’s perspective.[15] She seems to be right, at least in part: the woman in this passage is only a half-glimpsed movement in the dark. Writing about women and writing convincingly about cultural difference seem to have been skills that Le Guin had to learn in conjunction.

In the narratives that followed Rocannon’s World, the relationship between scientists and the cultures they study undergoes a succession of remarkable metamorphoses. Already in her second novel, Planet of Exile (1966), the scientists have come closer to the people they scrutinize; indeed they have become dependent on them. The Terran colonists in this second book have been stranded as a community on alien soil; they must integrate themselves with the inhabitants of the world they occupy or perish as Ishi perished, as a result of the incompatibility of their bodies with their new environment. The indigenous inhabitants of the planet, like so many of Le Guin’s ‘primitive’ peoples, have much in common with the Yahi; they will not meet each other’s eyes (Yahi men would not look into the eyes of Yahi women); they practice polygamy; they have summer and winter houses; they cremate their dead (the Yahi were the only native Californians to do so).[16] But by the time we meet a descendant of these two races, Falk in City of Illusions, they seem to have become entirely technologized, and little trace of the indigenous people of Alterra can be found in them. This is partly a natural result of the perspective from which Le Guin’s second novel is told. As in Rocannon’s World it is never quite clear who the narrator is in Planet of Exile, but there is nothing to suggest she does not share the expectations of a twentieth-century ‘Westerner’, since she commits the bulk of her novel to the task of tracing the movement of the main female character – a native Alterran – from the ‘primitive’ homes of her ancestors to the relatively ‘civilized’ city of the Exiles. In the same way, The Left Hand of Darkness persistently reminds its readers that they inhabit a patriarchal society; as Le Guin acknowledges in her essays, the narrator’s use of the ‘so-called generic pronoun he’ inevitably colours the reader’s response to the androgynous Gethenians. The protagonist Genly Ai may become a kind of sibling or lover of the principal Gethenian, Estraven, but that pronoun ensures that the reader never become wholly naturalized to the genderless cultures of the world called Gethen.

Le Guin’s frustration at the distortion this linguistic bias entails finds angry expression in her novella The Word for World is Forest (1972). The title of the novella alludes to a radical linguistic difference between Terran colonists and the inhabitants of a tree-covered planet. Those colonists who give much thought to such things believe they can exploit the logging opportunities afforded by this forested terrain without materially affecting the wellbeing of its human inhabitants; but they fail to recognize the extent to which the identities of these people are inextricably bound up with the woods they live in. Once again, the natives of the world called Forest, the Athsheans, have something in common with Ishi’s people. Men and women in this culture speak different dialects, as the Yahi did; male activities are rigorously distinguished from female ones; and they regard their dreams as instructive, as sometimes seems to have been the case among the Yahi. More importantly, perhaps, the men who ‘translate’ these dreams – those who convert them into speech and action – are among the most highly respected members of society. The word for translator and the word for god are identical, and the elision of these two concepts acknowledges the profound and sometimes terrible power of transmitting meaning from one form to another. Whatever is translated is changed irrevocably, so that the indigenous translator who is central to The Word for World is Forest, Selver, is also the individual responsible for transforming the culture of the Athsheans dreadfully and for ever. In this narrative, as we might expect, the proximity of what we would call the anthropologist – the ‘hilfer’ or scholar of ‘High Intelligence Life Forms’ – to the subject of study affects the subject more drastically than in any of Le Guin’s previous novels. Selver effectively merges with his hilfer friend Lyubov, and after Lyubov’s death the Terran’s ghost drifts sadly in and out of Selver’s consciousness, bringing with it the horrifying new ideas with which Lyubov is familiar. Once Lyubov’s knowledge has been translated into Selver’s language, Selver and the people he incites to violence against the colonists can never be the same again. The Athsheans avenge the Yahi nation on the colonists, destroying them with spears and bare hands as the Yahi themselves never could; but in the process they learn a new way of life; they learn the skill of genocide, and can never forget what they have learned. The precarious balance which kept Selver’s people free from war – uniquely free in the known universe, as the novella suggests, a situation as precarious as the ecological and cultural balance that enabled Ishi’s people to survive – has been destroyed, and they will never again be exempt from this infection.

The acute pain expressed in The Word for World is Forest – Le Guin observes that in contrast to her other work ‘this story was easy to write and disagreeable’[17] – springs from its fusion of the issues encountered in Ishi in Two Worlds with those of contemporary American politics. Throughout its length the parallels between the world called Forest and 1960s Vietnam are often made explicit.[18] The military leader of the Terran colonists is a Vietnamese soldier called General Dongh, who is despised as the scion of an untrustworthy race by his eurafran subordinates; and the eurafran soldiers among the colonists dull their sensibilities, as American combatants did in Vietnam, with the intensive use of hallucinogenic drugs. But the most aggressive of the colonists, Captain Davidson, bears an uncanny resemblance to an earlier manifestation of American colonialism, a man called Anderson who was the most prominent of the Indian-killers in Kroeber’s book.[19] Like Anderson, Davidson inspires unthinking devotion among his followers; as with Anderson, his concern for preserving a sense of his own masculinity is a driving force behind his violent xenophobia; and like Anderson he is a man adrift, a loose cannon who begins by being exploited by the colonial administration for their own ends but who rapidly develops an agenda of his own and loses all contact with his superior officers.[20] Kroeber attributes the savagery of the suppression of the Yahi in part to the aggressive individualism of the gold-seeking Forty-niners, stranded as they were hundreds of miles from the national government, with its inadequate but sometimes well-intentioned laws concerning the treatment of native Americans.[21] Like a forerunner of Marlon Brando’s General Kurz in Francis Ford Coppola’s Apocalypse Now Davidson quickly detaches himself from the chain of command and begins to act as a god on his own account. His actions as much as Lyubov’s awareness of his actions contribute to the translation of the peaceful Athsheans into killers – just as Kroeber judges that the killing of Yahi children taught the Yahi how to kill the children of the whites. Lyubov cannot help bringing Davidson into the Athsheans’ world, and at the end of the story Davidson is still alive years after Lyubov’s death, living among the Athsheans as implacably as the anthropologist lives on in Selver’s dreams. In this way Le Guin offers her most terrible and despairing word on the relationship between anthropologist and anthropologized, between the student and the studied: an impassioned cri de coeur on the impossibility of dissociating the dominant culture of the writer from the culture she strives to represent.

The Dispossessed responds to this problem by smashing the form of the conventional linear narrative. In its account of the career of the physicist Shevek, chapters on his early life in the anarchist world of Anarres alternate with chapters on his later stay in the capitalist world of Urras. Neither period in the scientist’s life is privileged over the other, and both phases make an equal contribution to his eventual reconciliation of the theories of Sequency and Simultaneity in post-Einsteinian physics. In the process, the problem of time which dogged Kroeber’s account of the life of Ishi reaches tentatively towards a solution. The problem is that in Kroeber’s text, for all the qualities that would have made Ishi and his people so well suited to life in the twentieth century, they remain firmly locked in the past – all are dead by the time the book is written – while Kroeber’s own people inhabit another period, the present; and the two periods remain as rigorously segregated from each other as Anarres is from Urras, despite all the writer’s efforts to bring them together. This is a problem of narrative technique as well as of chronology. A linear form of narrative insists that one thing follows another; it invites its readers to believe in the inexorable progression of a uniform ‘human race’ towards some sort of apotheosis, and so encourages the dominant culture to regard itself as possessing exclusive rights to the future. In The Dispossessed, by contrast, the past and the future coexist with the present. Anarchy has emerged from capitalism, and is continuing to emerge from it as the text unfolds thanks to the efforts of revolutionaries; at the same time, without constant vigilance on the part of the anarchists capitalism may swiftly reemerge from anarchy. In the course of the novel, discontented elements on Anarres are returning to capitalist values as conditions on the planet deteriorate, while dissidents on Urras struggle to forge anarchy in their disintegrating homeland. The point of narrating the two processes in parallel, as Shevek sees it, is that without an awareness of where they come from the Anarresti are in constant danger of repeating the mistakes of history. By returning to the Anarrestis’ point of origin, Urras, Shevek hopes (among other things) to remind the inhabitants of Anarres of the need to be perpetually renewing the revolution. At the same time he hopes that he will serve as a beacon of hope for the future to the revolutionaries on Urras. Without addressing themselves to both cultures simultaneously, neither he nor they can ever hope to find a way forward, either in science or in politics.

In addressing two antagonistic societies, Shevek might be said to offer a model for addressing two phases of American history, one of which has been privileged in textbooks to the virtual exclusion of the other. At one point in the dual narrative he hints at this in terms that must be startlingly familiar to Le Guin’s American readers:

He was a frontiersman, one of a breed who had denied their past, their history. The Settlers of Anarres had turned their backs on the Old World and its past, opted for the future only. But as surely as the future becomes the past, the past becomes the future. To deny is not to achieve. The Odonians who left Urras had been wrong, wrong in their desperate courage to deny their history, to forgo the possibility of return. The explorer who will not come back or send back his ships to tell his tale is not an explorer, only an adventurer; and his sons are born in exile.[22]

This way of describing the relationship between Urras and Anarres, the Old World and the New, may seem to place Shevek in the position of the heroic frontiersman of the legendary Wild West; an Anderson, say, who has suddenly become aware of his European ancestry and has returned to Europe to learn about the origins of the American republic – and to teach his ancestors a lesson. But Shevek has something in common with Ishi as well as with Anderson. Like Ishi he is baffled by the possessiveness of the people he encounters; like him he is amused by much of the gadgetry they are so proud of (and with Ishi he finds pockets one of the most amusing of these gadgets).[23] Moreover Shevek, like Ishi, is given to reversing the usual criteria for distinguishing civility from barbarism. The operations of capitalism ‘were as meaningless to him as the rites of a primitive religion, as barbaric, as elaborate, and as unnecessary’.[24] The history he learns on Urras is as much the history of those who opposed the barbarism of the capitalists as it is that of the capitalists themselves; it is the history of the freedom fighters who are branded barbarous by the society they challenge, and whose forebears have been banished to a harsh environment that resembles the barren land set aside by the American government for Indian reservations.[25] For this reason one might imagine that Shevek would have found as much to admire in the Yashi as in their European successors.

On the other hand, it is quite possible that he would not. If the Anarresti had been presented somewhat differently – or if Le Guin had written about them a few years later – they might have resembled a fusion of Native Californian culture with the culture of the pioneers. But The Dispossessed resists such a fusion. The moon to which Le Guin’s anarchists were exiled was uninhabited apart from a small colony of miners; and there seem to be no surviving aboriginal inhabitants of Urras. The one development of their society that the anarchists refuse is what the narrator calls a regression to ‘pre-urban, pre-technological tribalism’.[26] Le Guin’s utopian vision had to wait another eleven years before it could embrace a post-urban, post-technological culture as something better than a regression.

Which brings us to the most complex of her fictions, the unique compilation of stories, poems, recipes, songs, plays, maps and commentaries produced by the nonexistent future inhabitants of the Napa Valley, Always Coming Home (1985). In this book at last a people who bear some resemblance to the Yahi take over the various narratives contained in the volume, and adopt the role of instructors with respect to the ‘editor’ of the text; a very different role form that of the anthropologist’s so-called ‘informant’. Once again, the title of the book deserves to be dwelt on. Throughout Le Guin’s work two motifs recur repeatedly: the motif of the journey and the motif of the home. As we have seen, Ishi’s journey between two times was also a journey between two homes: his home by the Sacramento River and his home in the museum. Shevek traces a similar journey between two homes: his childhood home of Anarres and his ancestral home on Urras. The title of Always Coming Home combines the notion of travel with the notion of domestic stability – the spaces traditionally allocated to men and to women in European history. It suggests, as Ishi’s story suggests, that they are inextricably linked; that sequency need not be privileged over simultaneity, that constant movement can work hand in hand with an awareness of, and a respect for, where one is. It suggests that the culture of the Kesh need not inhabit an inaccessible future, but that it has always been present, always available to those who permit themselves to see it: like the woman who is glimpsed for a moment among the crowds of San Francisco in the story called ‘A Hole in the Air’.[27] The man of the Kesh who sees her is another Ishi, an exile who has strayed from the far future into the twentieth century through the mysterious hole of the story’s title, and who dies, as Ishi did, of an infection caught during his visit. The woman, on the other hand, is presumably still living in San Francisco at the time Le Guin is writing the story; waiting, perhaps, to find her way through another hole in the air to the Valley of the future, the place where she will finally be at home.

In addition, the title of Always Coming Home evokes the dual nature of the texts in that collection. Some are accounts of journeys, dominated by the history related by Stone Telling; others are celebrations of life among the Kesh, made up of the poems, songs and recipes interspersed with the prose throughout the book. The prose stories in the collection recount for the most part incidents in which the delicate balance of Kesh life is challenged or disrupted: breaches of Kesh etiquette, incursions by hostile intruders on the Valley, disturbances in the domestic environment – like the story of the vampiric consumer Dira (an anthropomorphic tick)[28] who almost eats a Kesh woman out of house and home, or the story of two angry old women who destroy their households, ‘Old Women Hating’. These narratives look familiar enough to a twentieth-century reader; they are appropriate components of what we take to be a literary work, although they also serve to strengthen the reader’s awareness of the difference between our culture and that of the Kesh. The recipe, on the other hand, is perhaps the most characteristically Kesh of the genres contained in the book. It is a text to be returned to time and again, to be modified, reduced or expanded as occasion demands, refusing to assert its authority over the reader, and ready t be forgotten as soon as it has lost its usefulness. It offers a witty analogy for the way the Kesh regard their literature; they ‘do poetry’, as Le Guin explains in an essay, ‘as a common skill, the way people do sewing or cooking, as an essential part of being alive’.[29] By reading or performing the poetry, by playing the music that accompanies the text (the first edition was accompanied by a CD), by cooking from the recipes, we bring the population of the book alive by inviting it into our homes; and in doing so we bring together the present and the future, what might be and what is, more fully perhaps than in any of our previous literary encounters. When we participate in Always Coming Home we find ourselves haunted by the Kesh as the translator Selver was haunted by the anthropologist Lyubov: changed by, rather than changing, the subject of study.

We might also find ourselves haunted by the ghost of Theodora Kroeber. The recipe is a mode of writing (like the anthropological biography) that Le Guin seems to have associated with her mother. In her introduction to the 1985 edition of Kroeber’s book of Native American stories, The Inland Whale (1959), Le Guin observes that ‘Theodora’s native gift was for the brilliant shortcut that reveals an emotional or dramatic truth, the event turned legend – not raw fact, but cooked fact, fact made savory and digestible. She was a great cook both of food and words’.[30] By combining cookery and Native American legend in Always Coming Home Le Guin might be said to have combined two periods of Kroeber’s life: the first sixty years, when she gave her energies to creating a home, and the last two decades, when she gave herself to creating books. In an essay on women who have succeeded in combining motherhood and writing Le Guin asks herself what her own mother might have achieved if she had not chosen, or been constrained, to separate the two roles chronologically.[31] The Kesh would have had a kind of answer: the roles are not fundamentally dissimilar, and both are equally creative. By the end of her life Kroeber was at ease with them both, as she was with the many surnames (Kracaw, Brown, Kroeber, Quinn) that marked out the successive stages of her personal history.[32] This is not, perhaps, an answer that will satisfy many women; but it is an answer that looks forward to a time when choices will no longer be determined by the gender, race, class or wealth of the chooser; a time that is always leaking into ours through the holes in the air made by the experimental writings of Ursula K. Le Guin.

[1] ‘Inside’ the world and ‘Outside’ the world are terms coined by Le Guin in Always Coming Home (1985; London: Grafton Books, 1988). The terms are explained in the section called ‘Time and the City’, pp. 149–72.

[2] For Yahi naming conventions see Theodora Kroeber, Ishi in Two Worlds (Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1962), pp. 126–8.

[3] ‘April in Paris’ can be found in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters (London etc.: Granada, 1978), vol. 1, pp. 31–45.

[4] ‘Nine Lives’ is also in the Wind’s Twelve Quarters, vol. 1, pp. 128–57.

[5] Rocannon’s World and Planet of Exile (London: W.H. Allen and Co., 1983), p. 27.

[6] ‘Dowry of the Angyar’ can be found under its later title, ‘Semley’s Necklace’, in The Wind’s Twelve Quarters, vol. 1, pp. 9–30.

[7] Ishi in Two Worlds, ‘Foreword’.

[8] Ishi in Two Worlds, p. 206.

[9] Rocannon’s World and Planet of Exile, p. 4.

[10] Ursula K. Le Guin, The Language of the Night (London: The Women’s Press, 1989), pp. 1–2.

[11] The Language of the Night, pp. 135–47.

[12] ‘Towards an Archaeology of the Future’ is the title of the book’s first section, Always Coming Home, pp. 3–5.

[13] Ishi in Two Worlds, pp. 97–8.

[14] Rocannon’s World and Planet of Exile, p. 4.

[15] For instance, in her essay ‘The Fisherwoman’s Daughter’, reprinted in Dancing at the Edge of the World (New York: Doubleday, 1972), p. 126.

[16] See Ishi in Two Worlds, Chapter Two, ‘A Living People’.

[17] See Again, Dangerous Visions, ed. Harlan Ellison (New York: Doubleday, 1972), p. 126.

[18] See Le Guin’s essay on The Word for World Is Forest in The Language of the Night, pp. 125–9. It is worth noting that the original title of the novella was The Little Green Men, alluding not just to the generic Martians but to racist descriptions of Vietnamese people in terms of size and colour that were prevalent in the language of the pro-war lobby in the 1960s.

[19] See Ishi in Two Worlds, pp. 63–8 etc.

[20] Anderson’s concern for his own masculinity is hinted at by his admiring disciple Sim Moak: ‘Anderson was twenty-five years old and as fine a specimen of manhood as one would wish to see… you can imagine a great tall man with a string of scalps from his belt to his ankle’ (Ishi in Two Worlds, pp. 65–6). Davidson too is a ‘big, hard-muscled man’ who ‘enjoyed using his well-trained body’ (Again, Dangerous Visions, p. 36).

[21] See Ishi in Two Worlds, pp. 43–5 etc.

[22] The Dispossessed (London etc.: Grafton Books, 1975), p. 80.

[23] The Dispossessed, p. 62; Ishi in Two Worlds, p. 162.

[24] The Dispossessed, p. 113.

[25] Attempts to resettle the Yana people on reservations proved abortive; see Ishi in Two Worlds, pp. 62–3 and 72–4.

[26] The Dispossessed, p. 85.

[27] Always Coming Home, pp. 154–7.

[28] I am grateful to Ursula Le Guin for pointing out to me that Dira was a tick when she read this essay in typescript.

[29] Dancing at the Edge of the World, p. 186.

[30] Dancing at the Edge of the World, p. 139.

[31] Dancing at the Edge of the World, pp. 231–2.

[32] Dancing at the Edge of the World, p. 138. Tenar in Tehanu inherits Kroeber’s multiplicity of names.