Rodolpho Hockmuller Menezes

Against Modernity

Domestic Terrorism in the United States and the Television Series "Manhunt: Unabomber"

Theoretical-methodological support

1. North American Traditions of Dissent In “Manhunt: Unabomber”

1.2 Criticism of the modern world

1.1.1 Henry D. Thoreau as dissent in the United States

1.1.2 Symbol for North Americans: Thoreau's log-cabin in Walden

1.2.4 The production of Manhunt and the log house

1.3 North American wilderness tradition: the aesthetic choice in Manhunt

1.3.1 The idea of wilderness in United States History

1.3.2 Nature as a component of North American identity

1.3.3 The choice of nature aesthetics in Manhunt: scenes and images

2. Intellectuals, Anti-intellectualism AND The Man of Action In “Manhunt: Unabomber”

2.1 Against elitism: anti-intellectualism in the United States

2.1.1 Anti-intellectualism in Manhunt

2.1.2 Images of the intellectual versus the man of action

2.2 Elements of the construction of James Fitzgerald and Theodore Kaczynski’s characters

2.3 The target audience for Manhunt

3.1 The creative process and the original script

3.2 A scripted series on the Shark Week television channel

3.2.1 Discovery's programming in the years before Manhunt (2012 - 2014)

3.2.2 The dispute with Netflix: Discovery's attempt to adapt to the market

3.3 The production of Manhunt: Unabomber

3.4 Interpretations and disputes over the narrative of the Unabomber case

3.4.1 Contesting the narrative: retired FBI agents

3.4.3 Manhunt and the recovery of Theodore Kaczynski on social media

Front Matter

Title Page

University of São Paulo Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences Department of History Postgraduate Program in Social History

Rodolpho Hockmuller Menezes

Against Modernity: Domestic Terrorism in the United States and the Television Series “Manhunt: Unabomber” (2017)

Dissertation presented to the Postgraduate Program in Social History of the History Department of the Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, of the University of São Paulo, as part of the requirements for obtaining the Master's degree.

Advisor: Prof. Dr Mary Anne Junqueira

Corrected version

I authorize the total or partial reproduction and dissemination of this work, by any conventional or clerical means, for the purposes of study and research, as long as the source is cited.

Cataloging in Publication

Library and Documentation Service

Faculty of Philosophy. Letters and Human Sciences at the University of São Paulo

Hc

Hockmuller Menezes, Rodolpho

Against modernity: domestic terrorism in

United States and the television series "Manhunt: Unabomber" (201*7) / Rodolpho Hockmuller Menezes; advisor Mary Anne Junqueira - São Paulo, 2023.

188 f.

Dissertation (Master’s) – Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo. Department of History. Area of concentration: Social History.

1. History of the United States. 2. Series (Genre). 3. Television. 4. Anti-Intellectualism. 5. Dissent. I. Junqueira, Mary Anne, orient. II. Title.

fflch

UNIVERSITY OF SAO PAULO

FACULTY OF PHILOSOPHY, LETTERS AND HUMAN SCIENCES

SUBMIT THE CORRECTED COPY OF THE DISSERTATION/THESIS

Advisor’s Term of Consent

Student name: Rodolpho Hockmuller Menezes

Defense date: 04/14/2023

Name of Professor, advisor: Mary Anne Junqueira

In accordance with current legislation, I declare to be AWARE of the contents of this EXEMPLARY ÇQRRICjIDQ prepared in consideration of suggestions from members of the Judging committee in the work defense session, expressing myself fully in favor of its forwarding to the Janus System and publication on the U$ Digital Theses Portal Q

São Paulo, 06/04/2023

HOCKMULLER MENEZES, Rodolpho. Against modernity: domestic terrorism in the United States and the television series “Manhunt: Unabomber” (2017). 2023. 188 f Dissertation (Master's) presented to the Postgraduate Program in Social History of the Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences of the University of São Paulo, to obtain the title of Master

Approved in:

Examination Board

Dedication

To B, your love and patience

made this work possible

Thanks

I would like to thank the Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo, for granting the master's scholarship and for the financial support to carry out this research, process number 2019/21042-0 Institution which provided me with the means, since graduation, to carry out research inside and outside Brazil The opinions, hypotheses and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of FAPESP

To the Department of History and the Faculty of Philosophy, Literature and Human Sciences, for the opportunity to take the course, together with the many workers and professors, who helped my research trajectory.

To Prof. Dr Mary Anne Junqueira, this research is the result of all the years of work together. I would like to thank you for your guidance since Scientific Initiation, which in these years of coexistence has taught me a lot, contributing to my training and scientific and intellectual growth

I would like to thank Prof. Dr. Mariana Martins Villaça, Prof. Dr. Eduardo Morettin and Prof. Dr. Alexandre Busko Valim for reading my work, for the recommendations, criticisms and suggestions, which are essential for us to develop this research

To Prof. Dr. Stacy Takacs, from Oklahoma State University, who in our dialogues has been guiding me about television and media. Thank you for your patience and for showing me that academic research can be something more fun and light-hearted. Thank you for welcoming me to Oklahoma, where I felt at home, even in a deeply Republican state.

To Oklahoma State University, especially the Department of English and the Screen Studies program, which provided me with all the necessary infrastructure to carry out this research while abroad. To the friends I made during my stay in the United States: Santiago Neira, Jonathan Howell, Ryan and Hugo.

To the producers and creators of Manhunt: Unabomber Greg Yaitanes, Andrew Sodroski, James Fitzgerald and Tony Gittleson, who made time and material available for this research. Without the testimony of these cultural industry workers, much of the analysis of this work would be incomplete.

I thank the workers at the Joseph A Labadie collection at the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, especially Julie Herrada, curator responsible for Kaczynski's correspondence Giden Gooodrich who welcomed me to the archive and made available all the materials I requested My thanks to Gabriel Mordoch, former -FFLCH student and Labadie worker, whom it was a great surprise to meet, thanks for bringing an air of familiarity to the Michigan winter

For my family, my dear grandfather, Pedro Moura de Almeida and my mother Irene Hockmuller, who are always a source of constant inspiration. I also express my thanks to the friends who motivated me during this journey: Mauricio Helfstein, Rodrigo Kuester, Lucas Tomasi, Yan Kalled and Leonardo Nogueira To my friend and colleague, US History researcher, Gustavo Sivi, thank you for the conversations about audiovisual and wilderness To Maria José, who during my most difficult moments, showed that life, like research, is a great learning experience

To Bruna B Fontes, historian, my companion, who carefully discussed the problems of my research. Thank you for the countless hours of reviewing my text, patience and attention you dedicated to me. Your support made it possible to write this dissertation and overcome all the obstacles that appeared.

Epigraph

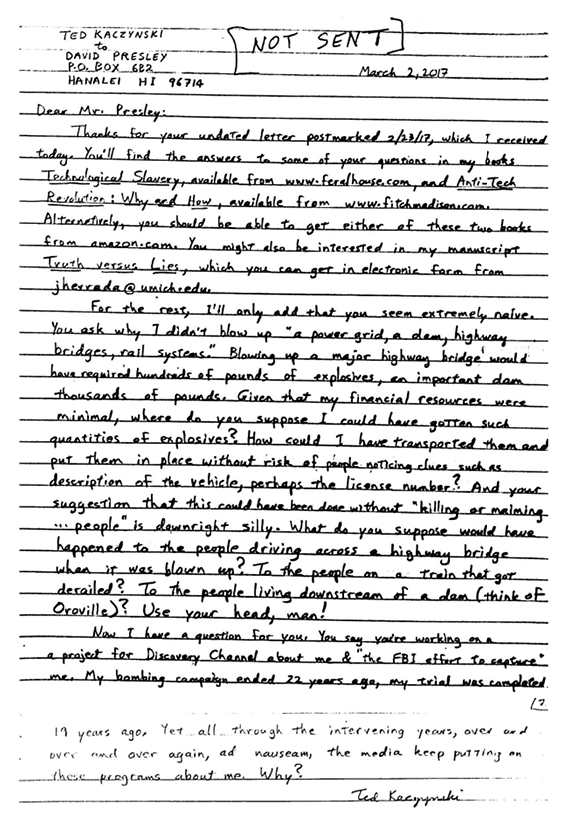

“Now I have a question for you. You say you're

working on a project for Discovery Channel about me &

“the FBI effort to capture me” My bombing campaign

ended 22 years ago, my trial was completed 19 years ago.

Yet all through the intervening years, over

and over and over again, ad nauseam, the media keep putting on

these programs about me, why?”Theodore Kaczynski[1]

Summary

HOCKMULLER MENEZES, Rodolpho Against modernity: domestic terrorism in the United States and the television series “Manhunt: Unabomber” (2017). 2023. 188 f Dissertation (Master's) - Faculty of Philosophy, Letters and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2023.

The Master's thesis analyzes the television series Manhunt: Unabomber, originally shown in 2017 in the United States on the Discovery Channel and on the streaming service Netflix The series represents the investigation of Theodore Kaczynski, an American domestic terrorist, from the point of view of James Fitzgerald, an FBI agent. Known as the Unabomber because his targets were initially airlines and universities, Kaczynski sent homemade bombs by mail, taking more than 17 years to be identified and arrested. The terrorist was identified based on the linguistic analysis of his manifesto, The Industrial Society and its future, which criticizes technological and modern society Manhunt tells the final phase of the case at the same time time in which it represents the reasons and events that led Kaczynski to carry out such acts of violence. Our objective was to think about traditions of dissent in the United States and the representations of wild nature in the narrative, as a counterpoint to life Modern. We address how representations of anti-intellectualism and institutions have roots in a reaction to American elitism. We proposed understanding Manhunt as a cultural product of its time, the result of negotiations by the series' production team. Therefore, we set out to discuss the changes in the industry that led Discovery to invest in a scripted series, considered elaborate and “of quality” in 2017.

Keywords: History of the United States; Series (Genre); Television; Dissent; Wilderness; Anti-Intellectualism.

Abstract

HOCKMULLER MENEZES, Rodolpho Against-modernity: domestic terrorism in the United States and the TV series “Manhunt: Unabomber” (2017). 2023.188 f. Dissertation (Master's) - Faculty of Philosophy, Literature and Human Sciences, University of São Paulo, São Paulo, 2023.

The master's thesis analyzes the TV series Manhunt: Unabomber, originally aired in 2017 by Disco very Channel in the United States, and available in the streaming service Netflix. The series portrays the investigation of Theodore Kaczynski, an American domestic terrorist, from the point of view of James Fitzgerald, an FBI agent Known as the Unabomber, as his targets were initially airlines and universities, Kaczynski sent homemade bombs by mail, taking more than 17 years to be identified and arrested The terrorist was identified by the linguistic analysis of his manifesto, The Industrial Society and its future, which criticizes the technological and modem society Manhunt dramatizes the final stages of the investigation while also portraying the reasons and events that led Kaczynski to carry out such acts of violence Our objective was to discuss the tradition of dissent in the United States and the representations of wilderness in the narrative, as the antithesis to modern life. We address the representations of anti-intellectualism and institutions as an answer to American elitism. We proposed to understand Manhunt as a cultural product of its time, the result of negotiations by the series' production team. Thus, we discuss the changes in the industry that led Discovery to invest in “Quality TV”, producing a scripted series in 2017.

Keywords: US History; Television; Series; Dissent; Wilderness; Anti-intellectualism.

List of Illustrations

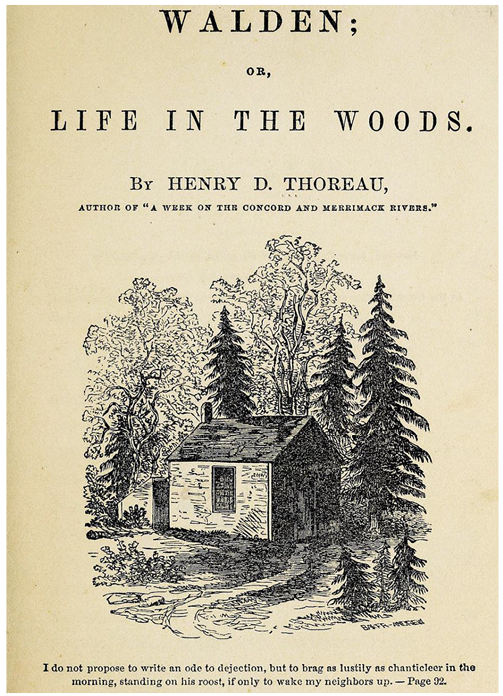

Figure 1 Title page of the first printed version of walden

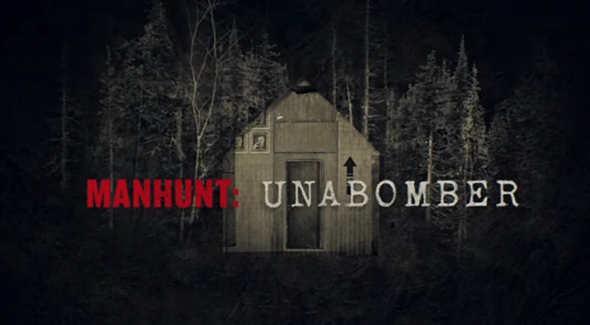

Figure 2 Image of the Series Opening Sequence

Figure 3 Log House in Transport

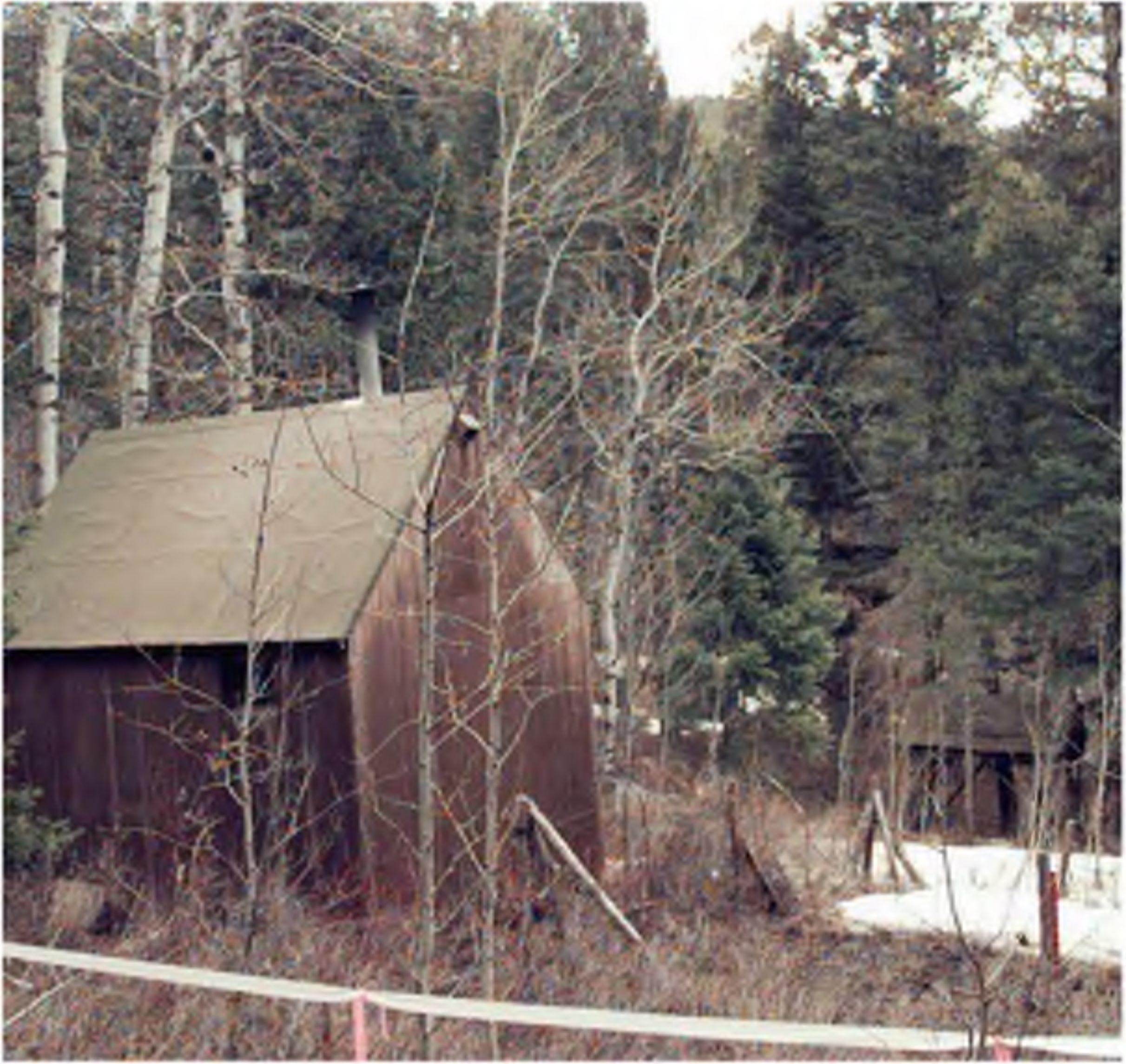

Figure 4 Photograph of Kaczynski's House in Lincoln, Montana

Figure 5 Scene of the Log House in the FBI Warehouse

Figure 6 Log House by Polish Artist Robert Kusmirowski

Figure 7 Log House on Display Over Kaczynski

Figure 8 Reassembly of the Log House on the FBI Premises

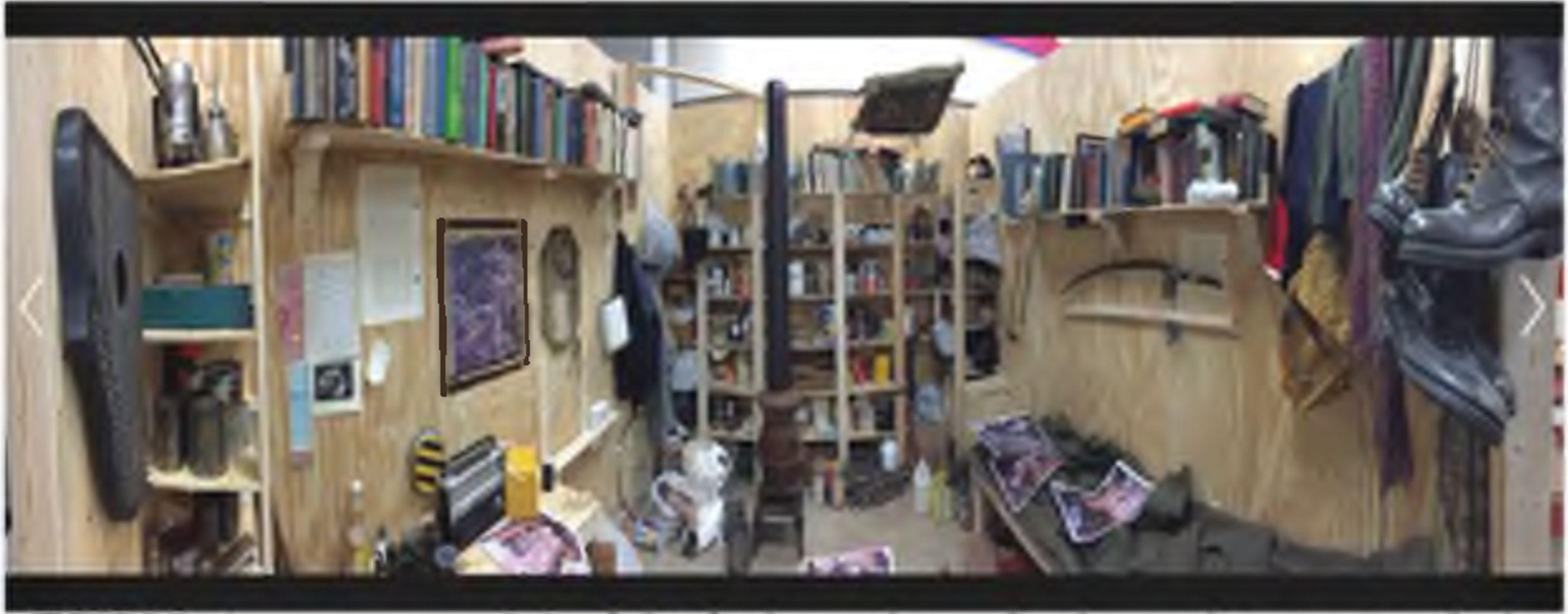

Figure 9 Panoramic Image of Log House Interior

Figure 10 Log House In Studio

Figure 11 Deleted Scene From Manhunt

Figure 12 First Page of Tony Gittleson's Script

Figure 13 kindred Spirits (1849) By Asher Durand

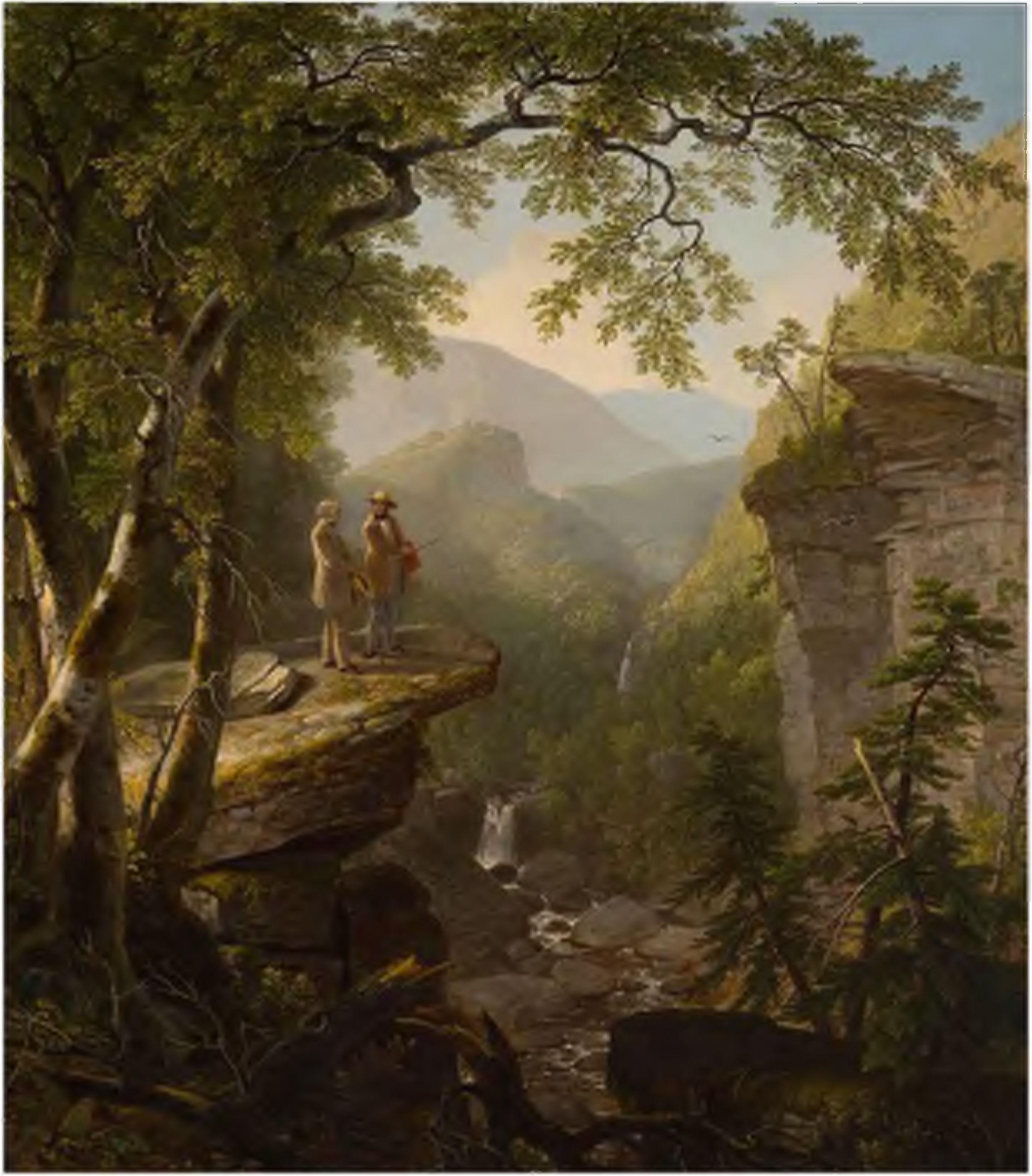

Figure 14 The Protagonist, Fitzgerald, Contemplates wilderness.

Figure 15 Graduation As profiler From the FBI

Figure 16 Kaczynski Dancing Freely In Wilderness

Figure 17 Director Yaitanes Analyzing the Camera Framing

Figure 18 Kaczynski Under Maximum Security Pressure

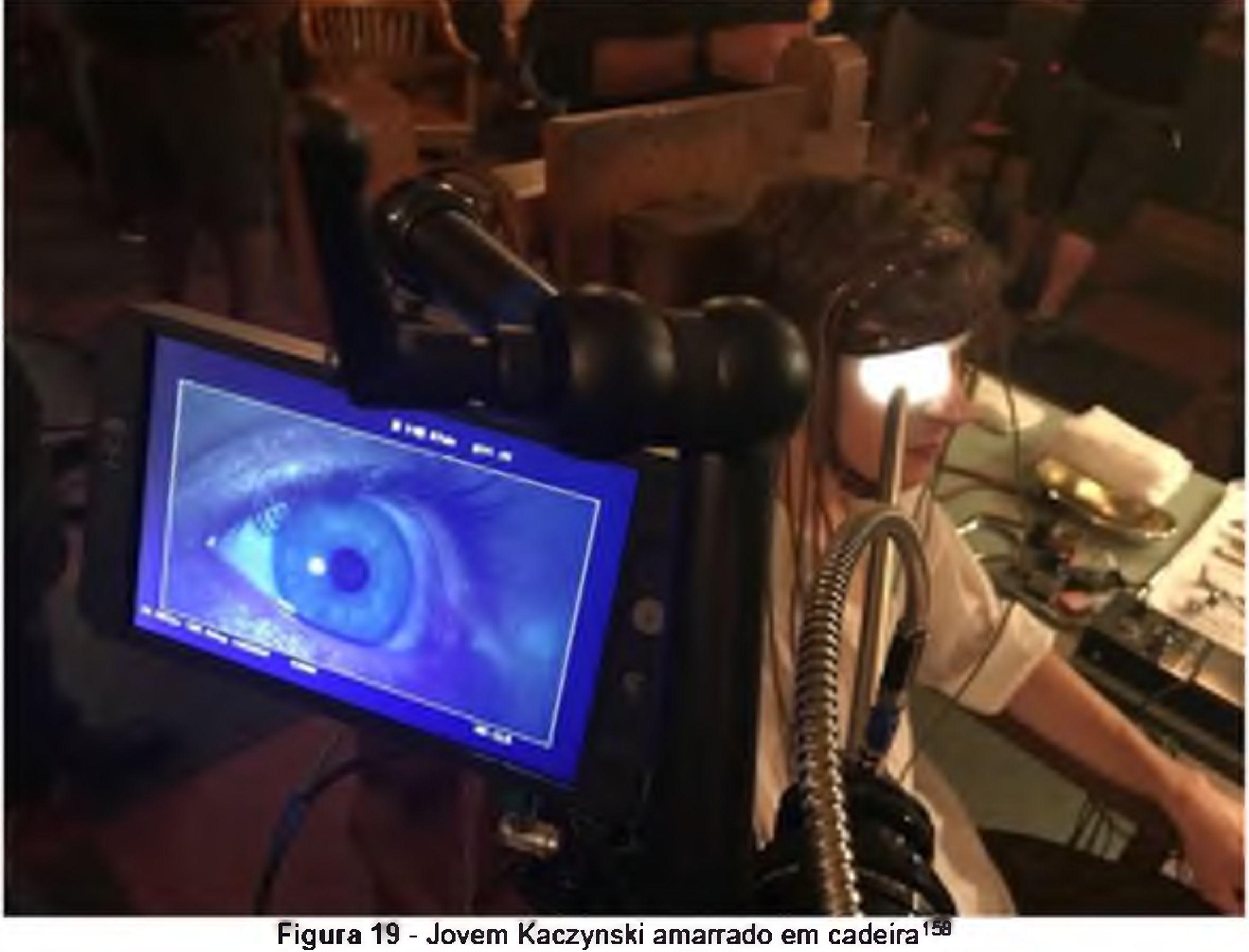

Figure 19 Young Kaczynski Tied to Chair

Figure 20 Kaczynski Recalls Torture Session at Harvard

Figure 21 Ackerman Analyzes Crime Scene Photos

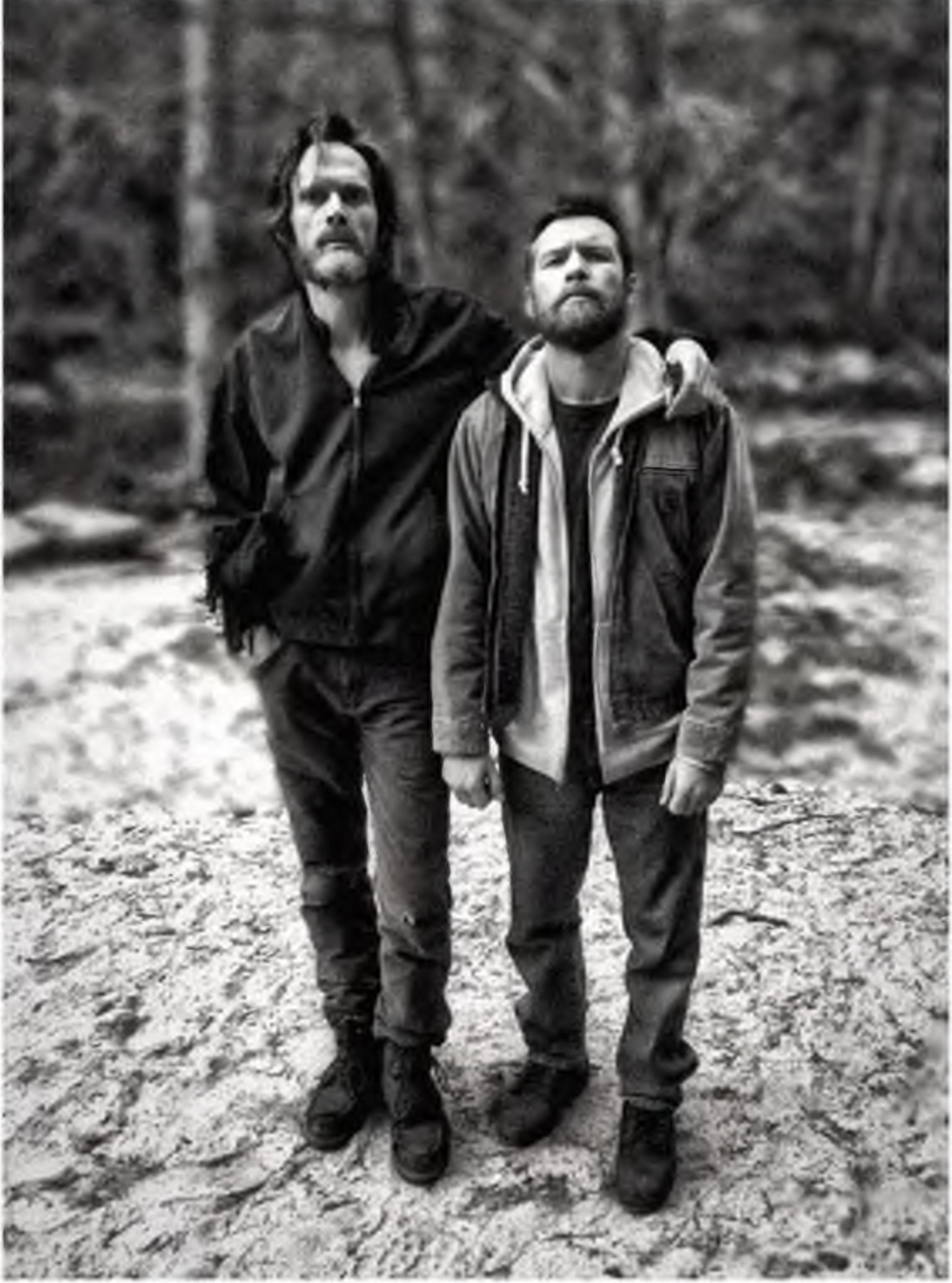

Figure 22 Behind the Scenes, Actors Paul Bettany and Sam Worthington

Figure 23 Scene Between FBI Agent Cole and Fitzgerald on the Stairs

Figures 24 and 25 Scenic and Original Objects Photographed from Kaczynski's House

Figure 26 Photos of Original Materials and Reproductions

Figure 27 James Fitzgerald On Foxnews Program (2018)

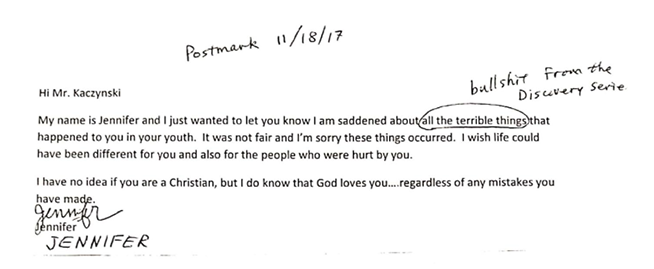

Figure 28 Letter Sent to Theodore Kaczynski. Authored by “Jennifer”

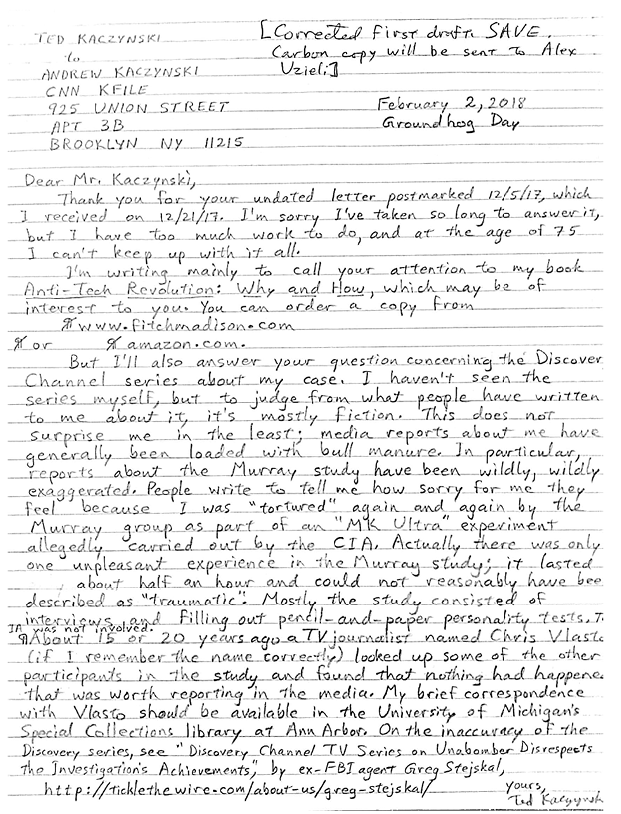

Figure 29 Theodore Kaczynski's Response to Journalist A. Kaczynski

Figure 30 Letter From D. Presley, From Manhunt Production, To Kaczynski

Figure 31 Vice Article About the Far Right

Introduction

Our Master's thesis aims to analyze the television series Manhunt: Unabomber (2017), originally shown by Discovery Channel and available in the Netflix catalog The series premiered in the United States between August 1st and September 12th, 2017 Totaling eight episodes, each lasting around forty minutes, it was shown weekly Although historians have already advanced in the studies of History and Cinema, research about television series are rare in Brazil and equally in the United States. Thus, it was a challenge to deal with a topic where the bibliography is summary. However, we consider that first with cable TV and then with streaming services there is an urgent need to address this type of cultural product. In other words, the series we studied tells us the speed at which the consumption of this type of cultural product has changed, showing how the act of watching television has been modified since the end of the 20th century. We thus explored this path given the popularity of television series in both the United States and Brazil. However, our purpose was not to study the reception of the product cultural in our country, but rather the series as a piece that deals with a specific North American cultural universe, although its inclusion in the Netflix catalog has expanded the target audience beyond the North American borders. American

The series chronicles the FBI investigation that captured and arrested Theodore Kaczynski (Paul Bettany), known as the Unabomber (acronym forUniversity and AirlineBomber). So it's about case that actually happened adapted for television, using fiction for the presentation[2] The series seeks to reconstruct the events involving the investigation of the domestic terrorist case, starring James Fitzgerald (Sam Worthington) In this way, the series has as its central character Fitzgerald, who used an unconventional method to analyze the clues in the case. Even though Kaczynski is also the protagonist of the plot. After years of trying to capture the terrorist, the FBI agent, as opposed to other police officers who followed traditional forensic leads, insisted on the possibility of linguistic analysis of the letters and texts written by the Unabomber, especially his manifesto, as a viable way for the FBI to reach the criminal. In the narrative, based on a critical reading of Kaczynski's texts, Fitzgerald, without formal academic training, tried to extract clues that would help to create a profile (profile), analyzing linguistic marks that informed gender, race, age, region of origin and training of the terrorist In the end, the capture of the Unabomber occurred not through the traditional forensic method, but through linguistic analysis of the text that the terrorist had written. Details of the series are found at the beginning of the first chapter of this dissertation

We understand Manhunt as a cultural product of its time, the result of negotiation and disputes in its production process. When narrating about the past, the program says more about its present than about the past period. We discuss why Manhunt Unabomber uses the representation of the investigation of the case, in the 1990s, to dialogue with the period of its exhibition, period of Donald Trump's presidency (2017-2021). The series aimed to reach a conservative audience and aired during a period of the rise of the far right in the United States

Our central objective was to discuss some North American traditions already mobilized in Hollywood, television and other media such as literature. This is how we identified at least three traditions from that country mobilized by the series: dissent, the idea of wilderness and the valorization of a certain anti-intellectualism in the country. All very well known to the North American public and little to Brazilian. In other words, it is possible to approach the series without taking these traditions into account, but the analysis would not gain density. Furthermore, as indicated, we defend thinking of our object as the result of negotiations and disputes. It is not possible to understand the television series outside the context of Discovery Channel and the emergence of streaming services such as Netfíix.

On the one hand, the door to enter North American traditions was given to us by Mary Anne Junqueira, supervisor of this work, and specialist in the History of the United States in Brazil[3]. Since North Americans are so immersed in these traditions, many

Sometimes they consider them as part of the world of economic liberalism, or the universe of the civilized world. However, they are an important reference and mark North American culture and politics. On the other hand, this work is a beneficiary of the important field of studies with which we had contact during the period we were in the United States. There, in addition to interviews with the team that created and directed the series, we had access to the field of Media Industry Studies, whose texts were important for the consolidation of this work[4]

In addition to the series itself, this work made use of documents found in the United States during a six-month stay, thanks to the support of FAPESP - Fundação de Amparo à Pesquisa do Estado de São Paulo Lá, in addition to access to important bibliography for the audiovisual, we were able to visit the archive where the documentation of Theodore Kaczynski, the Unabomber, is located. Through the letters exchanged by the domestic terrorist, we were able to evaluate part of the series' reception, including with the criminal seeking to have control over the narrative. The terrorist's Manifesto was another relevant document consulted by us. However, most important during our stay in the United States were the interviews that we were able to carry out with the series team. Without them, we are sure that the work would lose in density.

Kaczynski's documentation is on the main campus of the University of Michigan, in the city of Ann Arbor. This set of documents was named after a labor activist and anarchist from Detroit, Joseph Labadie (1850-1933). At the beginning of the 20th century, the activist donated books , newspapers, pamphlets, magazines, manuscripts and memorabilia that he collected over the years. Begun in the 1930s, the collection expanded from its initial focus, anarchism, to encompass broader dissident thought, especially in the United States, from the 19th century to the present[5]. In an article written by the curator, one of the reasons for preserving Kaczynski's texts is that he is part of a broader political tradition in the United States. Therefore, the material we researched in The Ted Kaczynski Papers is part of the main documentary collection on these social movements recognized in the country.

Most of the material available in the archive was acquired by donations from Kaczynski. He continues to send his manuscripts, correspondence and legal documents to the archive, as part of an agreement made between his lawyers and the University in the late 1990s[6] The documents are divided into eight series: Correspondence, Legal, Prison, Publications, Writings by Ted Kaczynski, Newspaper Clippings and Articles, Audiovisual and FBI Files[7] Added together, these series represent ninety-eight boxes of documents, each organized into dozens of folders, dating from before his arrest in 1996 until the recent year 2018.

Therefore, given the enormous amount of material that makes up the collection, it was necessary to reduce the scope of the research before visiting the archive. Focusing on the theme, we concentrated on the Correspondences Our goal was to study the letters for a broader understanding of the reception of Manhunt. As the majority of the correspondence series is composed of letters sent by individuals from 1996 to 2018, and the television program premiered in August 2017, we were able to collect letters in which the research object was discussed

Theoretical-methodological support

As we propose to analyze an audiovisual object, specific methodologies for this category of source become necessary for the historian, considering the support in which it is inserted, the particular challenges in interpretation and its own limits. Marcos Napolitano argues that when analyzing audiovisual sources, the historian must articulate the elements of the internal structure of language with the representation of reality. According to the author, a first decoding is of a technical-aesthetic nature, that is, the researcher must be attentive to the “ specific mechanisms mobilized by audiovisual language. In this sense, according to Napolitano, for the specificity of television one must think about the “text/image/soundtrack” relationship. Thus, the framing of the scene, duration, editing, colors used, chosen vocabulary and reiteration strategies are elements central to making sense of the work[8]

Another layer of decoding the audiovisual source, according to Napolitano, is in the representation "of the historical or social reality contained therein”. Therefore, seeking to understand the socially constructed representations with the content of the narrative structure (theme, characters and constructions of events) For Napolitano, the audiovisual source carries a tension between evidence and representation Therefore, the researcher must seek to understand representations by groups, institutions and actors at the same time as analyzing the source as “evidence of a process or event that occurred whose establishment of raw data is only the beginning of an interpretation process with many variables”[9]

Napolitano points out that some historians “tributary to the tradition initiated by Marc Ferro” seek to make a division between “actuality films (documentaries) and featured films (staged films)." These historians , according to the author, would be more identified with a “positivist conception of document". In this way, documentaries would be more preferable for analysis in comparison to staged films, because “according to this vision, each shot, sequence, or complete production is a primary record of the past and its edited set become a document in itself"[10].

Eduardo Morettin criticizes Marc Ferro, especially regarding the search for “authenticity” in the audiovisual source. According to Morettin, Ferro's analysis reveals an idea that it is possible to seek to rescue a “historical reality” in the film. The French historian sought to establish a methodology in which it would be possible to identify “deliberate manipulations” through the “angle adopted when taking the scene”, the legibility of the images, lighting, marks on the film, among others. In this way, it would be up to the historian to identify and separate possible "tampering" attempts from document analysis[11]

Morettin disagrees with Ferro about the analytical framework in the cinema-history relationship. In the author's analysis, Ferro places the written sources in the foreground in relation to the filmic document. Consequently, for Ferro the film would appear in the light of a historical knowledge already established a priori to “deny, confirm or complement” the bibliography Morettin criticizes Ferro for this procedure biasing the analysis with a teleological vision "the return , with the knowledge of what has already happened', within a teleological reading of history permeates Ferro's criticism. It is in the light of knowledge originating from the written tradition that cinema will be interpreted and made prisoner”[12]

Morettin then proposes that the filmic document should be treated for what it is: a document. In this way, questions, to avoid teleological conclusions, must arise from the analysis of these documents and not to give light to previous historical knowledge. Considering that the image has a polysemic character, the edits made should not be identified as “manipulations”, but as an integral part of the film that must be properly analyzed and questioned. Thus, the audiovisual document, as an object of study, must be understood in its singularity at the same time as it is investigated through the tensions it has with ideological projects that converge and/or conflict[13].

Manhunt: Unabomber has a specificity in that it is not a two-hour long film that shows first in theaters[14] As a series, it was originally shown at a certain time and is now available on the streaming from Netflix To discuss the television industry, we based ourselves on the studies of Amanda Lotz in The television will be revolutionized[15] The author analyzes the formats of programs based on their financing, distribution and consumption models Lotz states that much of what is used to think about television today was written during its initial period. According to her, television as a medium, between the 1950s and 1980s, was a broadcasting The few broadcasters were able to reach thousands of people. In the United States, during that period, there were only three broadcasters NBC, CBS and ABC Watching television was a habit that took place at home and in groups, due to less accessibility to the device. In this way, television programs were types ofwater coolers,as they should appeal, in some way, to different age groups, races, genders and political options[16]

However, current television in the United States is a narrowcasting medium, and no longer broadcasting The audience is fragmented among hundreds of free-to-air and cable television channels, broadcast services, and streaming (Netflix, Amazon Prime Video), video-on-demand platforms (iTunes, Hulu, Xfinity) and video-sharing sites (Youtube, Vimeo, DailyMotion). Furthermore, these different forms of television have different economic and regulatory processes that contribute to their operating standards and that influence the possibility of programs they can create[17].

As we have already indicated, television watching habits have changed, becoming increasingly individualized. The availability of reproduction platforms such as computers, notebooks, cell phones and video game consoles, in addition to the greater ease of purchasing a traditional television set, has contributed to the individualization of television. practice This new habit of watching television is also related to the fragmentation of the audience by particular interests. This initially happened on specific channels for sports, news and culture: “Initially, this niche programming was aimed at a more general audience, with channels like CNN looking for those interested in news, ESPN serving the sports audience and MTV targeting youth culture”[18].

Fragmentation increased in the early 2000s, when, for example, women's channels began to emerge (Lifetime, Oxygen, and WE) that distinguished themselves by providing programming for interests. divergent In other words, the audience began to be fragmented by age group, religion, gender and political spectrum[19]. In Lotz's example, it would be difficult for an American liberal to follow aFox News program[20]. Discovery Channel,a TV channel available on basic subscription plans, seeks to please a specific group. Because it is dependent on advertising to finance itself, the entertainment company sells inserts to companies that wish to promote products to their audience. In this dissertation, we explored how this method of financing had an impact on the narrative and the choice of Manhunt itself as a series to be broadcast on the channel.

We organize this dissertation into three chapters. In the first of them, entitled “North American traditions of dissent in Manhunt: Unabomber”, we discuss how criticism of the modern world and dissent, central to the message that Kaczynski sought pass through in his manifesto, are part of the North American tradition and imagination[21] Based on the symbolism of Henry David Thoreau and his log house in his book Walden, we contextualize Kaczynski's house in forest of Montana[22] Thus, we argue that, in order to understand various elements and images present in the television series, we need to discuss the dissent, combined with the idea of wilderness wild nature, within the History of the States United

In the second chapter, 'Intellectuals, anti-intellectualism and the man of action in Manhunt: Unabomber', we analyze the anti-elitist roots of American anti-intellectualism. In this second chapter of the dissertation, we deal with the representations of intellectuality and institutions in Manhunt, as well as its opposition to the man of action We articulate how the narrative uses the resources of mirroring and voice over to construct the characters of James Fitzgerald and Theodore Kaczynski In the end, we defend the need to understand the historical moment — 2017, Trump's election year in the United States — as well as the series' target audience, white, working-class men, over 35 years old, generally not very intellectualized — a reference to the North American “common man”,

The third and final chapter, “The Cultural Product Manhunt creation, production and narrative disputes in a television series”, focuses on the creative and production processes of the series, by theDiscovery Channel ,and some of the readings of its viewers. We trace how, since the original script, the production of Manhunt was marked by the dispute over the narrative on the part of its creators. Therefore, we argue that it is necessary to study Discovery and its traditional programming to understand why the channel chose to produce a "quality" scripted series. in the different readings and interpretations of Manhunt Unabomber We explored some of them, such as reports from other agents who worked on the case, letters sent to Kaczynski in prison and the recovery of the terrorist's ideas by far-right groups

1. North American Traditions of Dissent In “Manhunt: Unabomber”

The television series Manhunt: Unabomber seeks to reconstruct the events involving the investigation — led by FBI agent James Fitzgerald — of a sequence of attacks in the United States between 1978 and 1995, attributed to the Unabomber (University and Airline Bomber)[23]. The series chronicles the final months of the FBI investigation. Agent Fitzgerald, in opposition to the other characters who followed traditional forensic leads, sought to carry out a linguistic analysis of the letters and texts written by the Unabomber, especially the manifesto The Industrial Society and its future. It appears that the case was a pioneer in defining a new investigation instrument: Forensic Linguistics In the narrative, based on a critical reading of Kaczynski's texts, the agent tried to extract clues that would help to create a profile (profile), analyzing linguistic markers that provided clues about the identity and training of the perpetrator of the attacks

Represented in the plot, domestic terrorist Theodore Kaczynski was born in Chicago in 1942, the eldest son of a Polish-American family, a housewife mother and a working-class father. He was raised in a working-class suburb Often remembered as a “brilliant student” , began studying Mathematics at Harvard University at the age of 16, graduating in 1962. He then decided to pursue an academic career and began his doctorate at the University of Michigan, under the guidance of mathematician Allen Shields. He completed his doctorate in 1967 to then teach at the University of California Berkeley, in the position of Assistant Professor, where he remained until 1969[24] In 1971, he abandoned academic life and moved to a small isolated log house that he built in Lincoln, Montana[25 ]

In 1978, Kaczynski sent a bomb by mail addressed to an engineering professor at Northwestern University, beginning a series of 16 attacks on representatives of technology and modernity, such as academics and airlines. His campaign of terror continued for 17 years, causing the deaths of three people and injuring 23 more.[26] In 1995, a year before he was identified and arrested, he was published by the newspapers The Washington Post and in The New York Times his philosophical treatise, called by the FBI a “manifesto”, entitled Industrial Society and Its Future[27] Signing as “FC” (Freedom Club) ,the publication of the material was his demand to put an end to his campaign of attacks.

Arrested in 1996, he was tried and sentenced to serve four consecutive life sentences without the possibility of parole. Kaczynski appealed the sentence in every instance, reaching the Supreme Court in 2002, where it was rejected. maximum security prison in Florence, Colorado During these years, he was imprisoned in a block called Bombers Row, serving time with the most notorious terrorists in recent United States history such as: Timothy McVeigh ( Oklahoma City Bombing), Erick Rudolph (Olympic Park Bombing) and Ramzi Yousef (1993 attack on the World Trade Center)[29] The friendship that Kaczynski was held in prison with McVeigh, a far-right anti-government terrorist executed in 2001[30].

Kaczynski was transformed into a popular culture icon in the United States. There are numerous books, articles, exhibitions, photos, films, series, podcasts, documentaries and works of art about the terrorist and his famous log house[31]. After the premiere of Manhunt, several groups on Twitter and Facebook were created to discuss their ideas.

These communities created by far-right young people disseminate memes with their image and phrases from their manifesto[32]

Another central character in Manhunt is James Fitzgerald, a retired FBI agent (criminal profiler) represented as the person responsible for the arrest of the Unabomber. In real life, Fitzgerald wrote a trilogy of books about his police investigations, including A Journey to the center of the mind: Book III, which tells his experience with the Unabomber case[33] In addition, he works as a university professor at PennWest California, in the Department of Criminal Justice and Psychology

Fitzgerald has a long history in the entertainment industry. His work began while he was still working for the FBI, participating as a “technical consultant” in the third and fourth seasons ofCriminal Minds (2005 - 2020)[34] After debut of Manhunt, he gained greater notoriety in the media Since then, he has been invited to present Forensic Linguistics in lectures, interviewed in podcasts and occasionally invited to comment on topics related to security public on Fox News[35].

The first episode of the series, titled UNABOM: Task Force, begins with an opening text informing the audience that the fiction is based on real events[36] Afterwards, a narrator introduces the viewer to the functioning of the postal service in the United States[37] In this first sequence, which lasts around two minutes, the audience follows the journey of a post in the postal service. The camera focuses on a collection box, installed in a public place. In the foreground, we see an employee, whose face cannot be seen, collecting letters and packages contained inside the collection box and positioning them inside a vehicle. Once at the post office, the package reappears on a conveyor belt, in what appears to be a sort of sorting process, where it receives a stamp, by another anonymous employee. Efficiency and automation are seen as evidence of the modern world. The package is then transported to its destination, an office building. A secretary delivers the mail to one of the offices, where a man begins to open the box. Now, in a long shot, the camera is positioned outside the building where a large explosion ensues.

It is interesting to note that the narrator identifies himself by using the first person “I want you to think about the mail”, “I can send you cookies on the other side of the world”, “I write an address and they just… obey” [38] (Unabom, Ep.01). In other words, enough information is given so that the viewer can identify that the narrator is responsible for the act. In the first scenes, it is already possible to identify the intention of the series in establishing the terrorist's main criticism of the functioning of modern society: an employee passed the bomb without question, without knowing that he was releasing a deadly artifact to its recipient. In other words, he acted like an automaton, carrying out what he had to do, but alienated of the meaning of your work and its results.

Even in these first minutes of the series, attention is drawn to the moments in which the narrator speaks directly to the audience, comparing the viewer to a “sheep”, “obedient”, part of a society made up of “automatic” individuals.

Stop taking it for granted, like a complacent, sleepwalking sheep, and really think about it [...] And see, this only works because everyone along the chain acts like automatons [...] well, it's not your fault . Society made you this way. But you are a sheep and you live in a world of sheep. And because you are all sheep, because all you do is obey, I can reach and touch anyone anywhere. I can reach out and touch you... Now[39]

We understand that the series is dialoguing with a particular frame of reference recognized by North Americans, a tradition of dissent, criticism of modernity and the idea of wilderness

1.1 Henry David Thoreau

In Brazil, the United States is seen, in part, as powerful and almost ruthless in international terms, however, a strong tradition of dissent little known to Brazilians is part of the country's history. Dissent is a broad phenomenon, difficult to establish precise contours In In general, it is linked to questioning the government or an established order. Within this expanded scope are reformists, non-conformists, radicals, and those who operate from the perspective of civil disobedience

According to Saul Cornell, since its founding, the nation has undergone strong questioning with suspicion of centralized authority, the consequences of which have taken root in North American History. The author refers to the anti-federalists who, in debate with the federalists, were important in forging the country's Constitution. This is not about describing all the country's traditions of dissent, but it is important to highlight the role of the transcendentalists, commented on throughout this chapter and who were a reference for the series Manhunt

The transcendentalists were those who pointed out the contradictions of the modern world that was emerging. Although much of the dissent is linked to progressive radicals, it is not correct to establish the link exclusively to this field of politics, since there are radicals on the right who are also involved in dissenting actions[40 ] We believe that the TV series Manhunt dialogues with traditions of dissent from the past and present. Therefore, addressing how these elements are mobilized by the series means understanding the cultural product on its own terms.

1.2 Criticism of the modern world

In North American culture, among many other factors, there was a strong questioning about the modern world, which is opposed to an idea of wild nature, as we observed with the representation and images of wilderness in the series This is because an almost nostalgic look at nature is part of North American traditions. Wild, or even “untouched” nature is the counterpoint to the industrial and modern world, which was the choice of the United States to reach a certain social level, despite of the country's inequality, and their place in the world Authors, painters, writers used nature as a dissent, a contrast, to the modern world. More than that, nature is seen as a locus privileged for the encounter with the divine In nature, man could access the divine within himself. To this end, in the series Manhunt we seek to understand the issue of nature by following the narrative and the elements mobilized from its characters and scenes. In a similar way, we sought to study this issue based on interviews with production members given to us or media outlets.

It is important to note that Manhunt mobilizes an iconic image of American culture. We refer to the small log cabin (log cabin) by Henry David Thoreau, in addition to the imagery about the nature of that country. We emphasize that the television program never refers directly to this author, but uses symbols that refer directly to him. Even though the series is on a streaming service and is seen by the North American public , whose reading can do without the traditions discussed here, it gains a lot in meaning when we understand these elements that guide the look and interpretation of the North American public. The components of these traditions were selected, chosen by those who wrote, produced and directed the plot.

Henry David Thoreau, considered a dissenter in the 19th century, and his work Walden are part of the North American frame of reference and have been important since the conception of the series. The iconic author is recovered to legitimize and justify certain attitudes taken by the protagonists. In this way, the program, by referring the domestic terrorist's house to Thoreau's small house, points to Theodore Kaczynski as someone who acts within this tradition of dissent. the figure of the American poet and philosopher, to show how Manhunt projects Thoreau's legitimacy onto its protagonists

Given the importance of Henry David Thoreau, we seek to contextualize him in relation to a 19th century political-religious movement, known as transcendentalism, which has Ralph Emerson as one of its main exponents. Based on these elements, we seek to show the multiple meanings of Thoreau's log house: as a temple and place of contemplation of wilderness wild nature, symbol of non-conformity and rejection of modernity and its problems

1.1.1 Henry D. Thoreau as dissent in the United States

Henry D Thoreau (1817-1862), philosopher and poet, born in Concord, Massachusetts, was one of the heirs of the “John Thoreau & Co” pencil factory. With the proceeds from the manufacture, his family made it possible for him to study at Harvard University. After his graduation, Thoreau taught at a public school in his hometown, where he remained only a few weeks, when, faced with his refusal to corporally punish his students, he resigned.[41] Shortly afterwards he established a high school, where he worked until his death. of his brother and partner John Thoreau Jr. Between 1841 and 1843, Henry Thoreau lived on the property of Ralph Waldo Emerson (1803-1882) and his family Emerson, his intellectual mentor, was one of the founders of the religious-philosophical movement that became known as transcendentalism.

Transcendentalism is inserted in a North American context of reaction to industrialization, the mechanization of the world and bourgeois capitalist society. Elements that can be seen in the series both in the construction of Kaczynski's character and in that of the federal police agent, a specialist in building suspect profiles, James Fitzgerald Emerson pointed out that there were two forms of knowledge. The first is understanding, the formal and academic knowledge imposed by externality, and the second is reason. would be an innate and intuitive knowledge, present in the self We would all be able to recognize what is beautiful, not needing the teaching of this capacity When we share these universal morals, we would be, in some way, connecting with the “creative force" Seeing nature in a positive way, we ended up placing it as a living entity, the same divine spark present in the human was present in the non-human[42]

We recognize truth and beauty the moment we are connecting with the creative force of the universe. Emerson called this creative force 'oversold* and our individual souls would be part of the oversold. We are all part of divinity. We all have a spark of divinity within us. When we see this, we find self-realization, we recognize our connection with nature, with the universe, with all living creatures. In this sense we see that there is no difference between humans, there is no difference at the soul level between races or genders. Thus, self-realization leads us to a deeper engagement with the world[43]

Transcendentalists saw a correspondence between the lower plane of the physical world and the higher spiritual sphere[44]. In this sense, nature assumed central importance. If observed correctly, it could reveal universal spiritual truths: “nature is the symbol of the spirit... the world is emblematic”[45] In other words, it acquired a spiritual role as it was like a privileged portal of access to the superior laws that emanate from God.

For transcendentalists, man belonged to the material world, but had the potential to transcend this condition using imagination and intuition. In the same way, he could discover his correspondence with the divine and his capacity for moral improvement. All individuals would have the capacity to transcend ; however, this was a difficult and delicate path, which could only be found in individuality[46].

This movement placed the self and the solitary search for this connection with the creative force as central. Society demands obedience from its individuals, the suppression of the self, said Emerson. In response, he defended non-conformity, the subject should think and live based on the self, that that everyone considers divine. Institutions and legislation should be questioned if they affirm how a man should live. Each individual should be self-sufficient, to think and govern their life, even if they do not correspond to the expectations of others or society:

Everywhere society is in conspiracy against the humanity of all its members. A Public Limited Company, in which the members agree, in order to better ensure their bread for the shareholder, to give up the freedom and culture of those who feed. The most requested virtue is conformity. Self-sufficiency is his aversion. She doesn't like reality and creators, but names and customs. He to be a man, must be a nonconformist[47]

Authors consider the transcendentalist movement, and, therefore, Henry David Thoreau as a dissent. If Emerson was a highly relevant exponent, Thoreau is the one who took the principles of transcendentalism further. In addition to criticisms of the industrial capitalist way of life, the author also defended , in the book Resistance to Civil Government (1849), the individual's "duty" to oppose laws considered "unjust"[48] Although the first edition received little attention, from its reprinted in 1866, the text gained fame and came to be considered one of the most influential works of North American literature[49]

One of the reasons why the text became known was the way the author composed the topic of civil disobedience, which was consolidated as an active rejection of enlistment in the War with Mexico (1846-1848), laws and/or institutions considered unjust, even if this action was against the "status quo" Thoreau's book gained great popularity in the 1960s and flourished among those in the counterculture and protests against the Vietnam War. More than that, Thoreau's text became a reference for protests and non-violent demonstrations in the United States and beyond Proposing actions such as non-payment of taxes (carried out by Thoreau as a protest against the financing of the war against Mexico and slavery), his proposals served as the basis for interpretations about non-violent resistance. violence of leaders such as Martin Luther King[50] and Mahatma Gandhi[51].

The popularity of the author's works also leads us to realize their impact on the country's popular culture. Thoreau's figure is disputed by different groups, who often have conflicting interests. He is celebrated by libertarians, who see in his search for autonomy and objection to the State a man to be remembered. On the other hand, during the struggle for civil rights, individuals and groups saw in him peaceful methods to question unjust authorities in different institutions. In addition, in the counterculture, hippies saw transcendentalism and Thoreau as a form of spirituality alternative to the Judeo-Christian tradition[52] Buell points out that everyone finds something in the philosopher to appropriate, his image appears as a symbol in different places in North American culture[53] Therefore, it is not surprising that Thoreau is referenced in cinema and on television.

It is possible to find references to Thoreau in animations such as South Park, The Simpsons and in comics from the New York Times. Films such as Amazing Grace and Chuck ( 1987), Dead Poets Society (1989) and Awakenings (1990) represent the figure[54] More recently, it had a symbolic presence in critically acclaimed features such as Into the Wild(2007) The film, based on the true story of Christopher McCandles (Emile Hirsch), narrates the journey of a young man represented as successful in his studies and with a promising future. However, upon feeling that he was being "corrupted" by modern society, donates his savings to charity, burns his identity and credit cards In this adventure drama film, the character abandons his belongings and adopts a new name, crossing the United States with the aim of reaching an isolated region of Alaska, where he wanted a simpler life[55] Thoreau is symbolically present in this film, just like the philosopher, the film's character, McCandles, saw wild nature in wilderness , solution to your discontent with civilization and its problems

In television series, just to give one example, there is The Society (2019), available on Netflix aimed at a young audience. The narrative begins with the disappearance of the adult population of a city, in which children and teenagers find themselves surrounded by wild nature. After some time, when they decide to enter this unknown jungle, one of the characters quotes an iconic excerpt from the work Waldenby Thoreau “I went to the forest because I wanted to live deliberately, to face only the essential facts of life, and see if I could learn what it had to teach, and not, when I die, discover that I never I lived”[56]

Both Emerson and Thoreau are treated as prominent thinkers, whether from the perspective of an expert in academia or popular culture. This is because a wide audience continues to explore his image and representations of Walden as a metaphor or ideal to be followed[57] Manhunt follows this same path, by making constant references to the setting, aesthetics and values associated with Thoreau. Therefore, it is necessary to briefly look into the content of Wafcten to show how these issues appear in the series and in the speeches of the production members

1.1.2 Symbol for North Americans: Thoreau's log-cabin in Walden

Walden, Thoreau's most famous work, was written between 1845 and 1847, during the author's two-year retreat at Walden Lake, Emerson's estate, in the middle of the forest, near Concord, Massachusetts[ 58] The book is a report of personal experience, indicating that it is possible to live autonomously, beyond the barriers of materialism and social impositions, exploring spiritual progress through a connection with nature[59] The author's livelihood, for most of his time at the lake, he depended on a small garden that had beans, potatoes, corn, peas and turnips. Another part of his diet came from hunting small animals and collecting fruits in the forest[60]

We highlight in the image above Thoreau's small house already printed in the first version of Walden, in 1854; It is, therefore, an imaginary that spans almost 170 years. It is precisely in reference to this house that the series opens, showing Kaczynski's way of life in the midst of nature and mobilizing the entire framework of dissent against the world modern.

Thoreau built his own house plank by plank and reported how much material and money he needed to build his own house and reported step by step in Walden In the same way, as we will see below, Kaczynski built his own he marries mathematical rigor, as reported by his brother in the series. According to him, it was perfect. Thoreau's house, in the 19th century, measuring 3x4 5 m2[62]. As furniture, it only had a bed, table, three chairs, mirror and lamp. As for household utensils, it had a kettle, frying pan, pan, molasses jug, dishwashing bucket, ladle, spoon, three plates and two forks and knives. Man only needed “food, shelter, clothing and fuel” to survive[63].

The thinker stated that, between civilized man and savage, the first lived better, in palaces, compared to the second, however, he was poorer, because the civilized man's home is much more expensive[64] The civilized world imprisoned man , even if there was the speech of freedom It means that Thoreau's little house is symbolic for North American culture So that, when a little wooden house is designed, it is immediately linked to Thoreau

The author defines the costs of the modern world as "what I call life that is required to be exchanged for something, immediately or in the long term.”[65] In his context, the author pointed out that only a fraction of those who lived in the city could acquire a house, since the majority paid rent. Those who had the means and ventured into buying a house, exchanged around fifteen years of work, or even half of their life, to acquire a "luxury box", in this way, " would the savage be wise to exchange his hut for a palace on these terms?”[66] This house would be comparable to a box or a cave because it was an obstruction, which prevented the contemplation of nature “birds do not sing in caves, nor do pigeons show their innocence in a nest.”[67] As we see in the image above, the image of Thoreau's construction, represented on the title page of the first version of the book, appears inserted and in harmony with nature

Thoreau observed and questioned the first effects of industrialization, not only in the sense of the expansion of the number of factories, but how this accompanied a new way of perception, meaning and values on the part of society — or the emergence of a new culture. The clock occupied a central place in Thoreau's economic model. This is representative of the role the instrument played in the expansion of industrialism in 19th century New England. With the construction of factories and railroads, large-scale access to accurate time became essential. In the previous period, watches were relatively expensive and luxury items, made only by master craftsmen[68]

Being manufactured on a large scale, Thoreau observed that the tool of the industrial apparatus began to govern the worker's way of life, who became a machine. The individual became an automaton, as his life began to be strictly guided by an apparently impersonal and autonomous technology[69] In this way, the philosopher warned that men had lost control of their own inventions, which began to dictate the his own way of life “man has become the tool of his tools”[70] We will see that part of this criticism can be found in the series Manhunt The series is inserted within a larger theme in the audiovisual When the audience see Kaczynski's log house, there is a series of images and narratives that can be mobilized.

1.2.3 Kaczynski's log house

In this section we will work on the different meanings of Theodore Kaczynski's small house in the series. The character is represented, in a large part of the narrative, as someone who built his own wooden house. We will show how this place has different layers of meanings: it can be a place where it is possible to dream a different reality; as a symbol of dissent to industrial society; as a representation of danger, as it is an isolated space for the manufacture of explosive materials; a place where life’s traumas are relived in an isolated and solitary way.

The log house represented in the series is a symbol of the character's dissidence towards American society Kaczynski lives isolated, in a primitive way, without electricity or running water, collects food in the forest, eats game and from his small garden He does occasional and manual work , living on about four hundred dollars a year (Apri, Ep. 05) Lives alone in his 3 x 3 6 m2 house, therefore, similar to the size of the house of Thoreau, far from any neighbors, but close to a village where there is access to newspapers. Like Thoreau, Kaczynski was not completely isolated. Still, we use the adjective isolated here to refer to Kaczynski's location because the village was small and just a center to provide for necessities. However, he and Thoreau were not hermits far from everything and everyone. In Lincoln, Montana, Kaczynski easily traveled by bicycle to this town where he bought what he needed, maintained some relationships and visited the library. He had feelings for the librarian and her son, to whom he taught math (Ted, Ep 06)

In the opening sequence of the series Manhunt there is the image of a mailbox with stamps and conventional marks, which folds like an origami. The upper ends retract and shape themselves, until forming the log house by Kaczynski In the foreground, the title of the series appears, Manhunt written in red, Unabomber, imitating typewriter typography Little by little, in the third plane, in the background, The silhouette of several trees surrounding the house is revealed, forming a contrast to the black background. We emphasize the importance of the opening sequence, present in all episodes of the series. In this first moment, there is no image of Kaczynski, the central character of the series; however, the viewer is introduced to the nature of the log house. Such a perspective indicates that the image of the small house and the sign is enough for the audience to understand the message.

The dark and shadowy background that surrounds it stands out. The house seems to float in the air, as it does not have a well-defined floor. The material with which it is made, a cardboard box, refers to the material used by Kaczynski to send his bombs, but it can also refer to the use itself, a place to reserve something or someone's refuge and hiding place, in this case, Kaczynski (FIGURE two)

Note in the figure above, the image similarity with the title page of the first printed version of Walden (FIGURE 2) Although in Thoreau's book the house is more delineated, the elements used for the representation, such as the theme of the simple house surrounded by nature, it remains in the series. Thus, Kaczynski's home is a clear reference to Henry David Thoreau in the terrorist's life and in the product we analyzed.

By mobilizing this symbol, the series communicates with North Americans in general All it takes is an image of a small wooden house in the middle of nowhere to remind you of Thoreau's house A symbol of nonconformity is recovered from the past, although it is difficult for those unfamiliar with these North American traditions to understand the layers of meaning mobilized This symbol evokes the rejection of materialism, modern society and its hierarchies Again, for a Brazilian viewer, this may go unnoticed, but the North American recognizes Thoreau within the frame of the country's political culture. This does not mean that every American agrees with the philosopher's ideas, but that they recognize the codes and identify the figure of the thinker within a historical context of dissent. In this sense, the legitimacy of this icon is projected onto the character of Theodore Kaczynski

The series, by bringing the domestic terrorist closer to Thoreau, places him as a dissenter, despite the fact that the choices made by Kaczynski are not the same as those of the 19th century thinker. While Thoreau proposed civil disobedience in a peaceful way, the Unabomber when disagreeing with the modern world, he chose an extreme form of violence: sending bombs by mail to symbolic people of the world he questioned

Soon after the opening commented here, the second reference to the log house appears, in more detail, in a dialogue between James Fitzgerald and David Kaczynski during the most advanced phase of the investigation, after the terrorist's brother and his wife recognized the ideas and the text from the Unabomber and contact the FBI (Abrí[71], Ep. 05). When the FBI agent goes to his house, Theodore Kaczynski's brother shows a photo of the terrorist's log house. Soon after, the camera, in travelling, brings us closer and shows Theodore's address The house is surrounded by trees, some are dry, others have vibrant yellow leaves, although a grayish tone predominates in the background. The narrative turns its attention to the dialogue, the brother says that he had some contact with Theodore, when he returned to do small jobs, but all that changed when he left after a disagreement. David continues and says that his brother went to nature because of his convictions, but also because the relationship between the two was broken.

David Kaczynski tells FBI agent James Fitzgerald about his brother's way of life in Montana: “It's perfect simplicity [...] he lives outside the system”[72]. The house appears inserted in nature at the same time as, in a certain way, hidden from the viewer's view, as the scene only surrounds the house, not offering us any more details about the environment (Abri, Ep. 05). David dedicates himself to life in a different way to his brother. In the series he lives in a characteristic house in a North American suburb. Living with his wife in the state of New York, he is represented within a domestic environment common to North Americans, inhabiting a spacious house, with car in the garage. In this way, he is a typical middle-class North American (Abri, Ep. 05).

David is representative, in this way, of the lifestyle that his older brother rejects The character serves as a strong contrast that highlights the life choices, material and emotional, that Theodore disapproved of The scenes in which he and his wife are represented inside the residence are marked by the use of a gray color palette, with a predominance of close-up shots. Somehow, both the brother and the FBI agent are complex characters who completely reject Kaczynski's terrorist actions, but admire him due to his awareness of the modern life and having the courage to give another direction to life, it is possible to notice this perspective when the brother describes the log house as having “perfect simplicity” (Abri, Ep.05)[73] .

The centrality of the log house in understanding the character's narrative is highlighted. It is also in that space that he relives his traumas, moving away from human relationships. In the village near his small house, when the boy, the son of the librarian to whom Theodore teaches mathematics and advises on problems at school, invites him to his birthday party, Kaczynski builds a simple musical instrument for the boy with his own hands. . Upon arriving at the door of the house, he observes the exact moment in which the smiling birthday boy is presented with a modern electronic keyboard. The people around are impressed with the technological instrument. The gift had already dazzled the boy and Theodore, disappointed, did not enter the residence, returning in the middle of the dark night to the log house, where he locked the door and closed himself off for socializing. social (Ted, Ep.06)

The log house, in reference to log-cabin, so prominent in the North American imagination is also the place where Kaczynski prepares and stores the explosives. It is there that he gathers the tools and chemical ingredients necessary to, With care and dexterity, build your destructive artifacts. During the narrative, it is revealed that he keeps a bomb under his bed, indicating the impulse to continue with his campaign and the risk he exposes himself to by sleeping on top of the explosive object. In this sense, the log house can also mean danger to your table , where he builds destruction, is also the privileged space of his typewriter, which he uses to write the manifesto against industrial society. The document was sent to newspapers across the country, being published in the hope that the Unabomber would stop the attacks

After Kaczynski is detained by the FBI, the house is removed from Montana. In one scene, an electric saw is shown cutting the supporting stumps of the house, the loud noise of the electrical equipment causes a feeling of discomfort, disturbing animals and the spectator himself (FIGURE 3) To add, the noise of the helicopter propeller, necessary for the removal of the log house in the midst of wilderness the disturbance increases Modernity and its machines disturb the natural order The scene is violent and quite symbolic: technological objects are brought to uproot the house, at the same time at the same time as it amplifies the sounds of machines, strange in that environment, but known in the urban scene (USA vs Theodore Kaczynski, Ep. 08).

Below, images of the moment when the helicopter transports the house over the forest and the river, in an unimaginable scene. It then passes over a city until it is transferred to a train We also notice an aesthetic that recalls the Hudson River school paintings of the 19th century, as we will see below The proportions throughout the sequence highlight the enormity of the natural landscape in relation to technologies human In many ways, the series shows the predatory relationship that man, in this case North Americans, has with nature in the past and present.

We highlight the importance of discussing how the series presents and represents Kaczynski's home in Montana, the log house in the middle of the forest, and its similarity to that of Thoreau in Walden For the North American viewer , this is not a simple cabin The house belongs to the North American imagination, to a frame of references that have different meanings from that of the Brazilian spectator. This aesthetic of the log house in the middle of nature is then part of an American tradition that is linked to idea of wilderness, a concept that we will discuss below. In addition to the comparison between Kaczynski's houses in the series and the title page of Walden, we can think about housing in a more wide

Next, we insert a photograph of Kaczynski's real home in its original context in Montana (FIGURE 4). The house only makes sense in a natural context. It is the "minimum" that allows man to survive in the hostile environment of the forest. Whether with Thoreau or Kaczynski, the important thing was the experience in this environment.

Let's go back to the series Manhunt and see another image of the house in a completely different setting. In this scene, the house is represented in a cold and sterile FBI warehouse, completely losing its meaning, size and condition (FIGURE 5)

In an article from the New York Times about the exhibition by Polish artist Robert Kusmirowski, we identified yet another representation of the log house (FIGURE 6) This time it is a reproduction of the house by the artist Na description, the reporter highlights that “the theme of the Unabomber's cabin has been exhausted by American art, and perhaps in Europe.”[77] In other words, both the Unabomber and his small house go beyond police and judicial means. They reach streaming services and art galleries We highlight the similarities between the representations of the houses: the first in the series when in the FBI warehouse and the second in the exhibition, as art They are in "sterile" places '', alien to its original idea, thought to be somewhere else, in the context of nature.

Let us now see a decontextualization and reconstitution of meaning in an exhibition at Kaczynski's house, at the interactive museum Newseum dedicated to journalism, in Washington, DC, an object for artists, a place of visitation, an interest for onlookers and a highlight in the series In the background of the photograph, captured at the exhibition, we can read on a plaque “a madman and his manifesto” (FIGURE 7)

With the closure of the museum in 2019, Kaczynski's log house returned to the FBI's premises. In a short video posted on the investigative agency's official website, the reconstruction of the log house is reproduced, now inside the institution's museum (FBI Experience) In other words, in these museum exhibitions the log house appears as an object of curiosity and entertainment (FIGURES 7 and 8)

On the sign: "Kaczynski carried out 16 bomb attacks that killed three people and injured 24 others"

1.2.4 The production of Manhunt and the log house

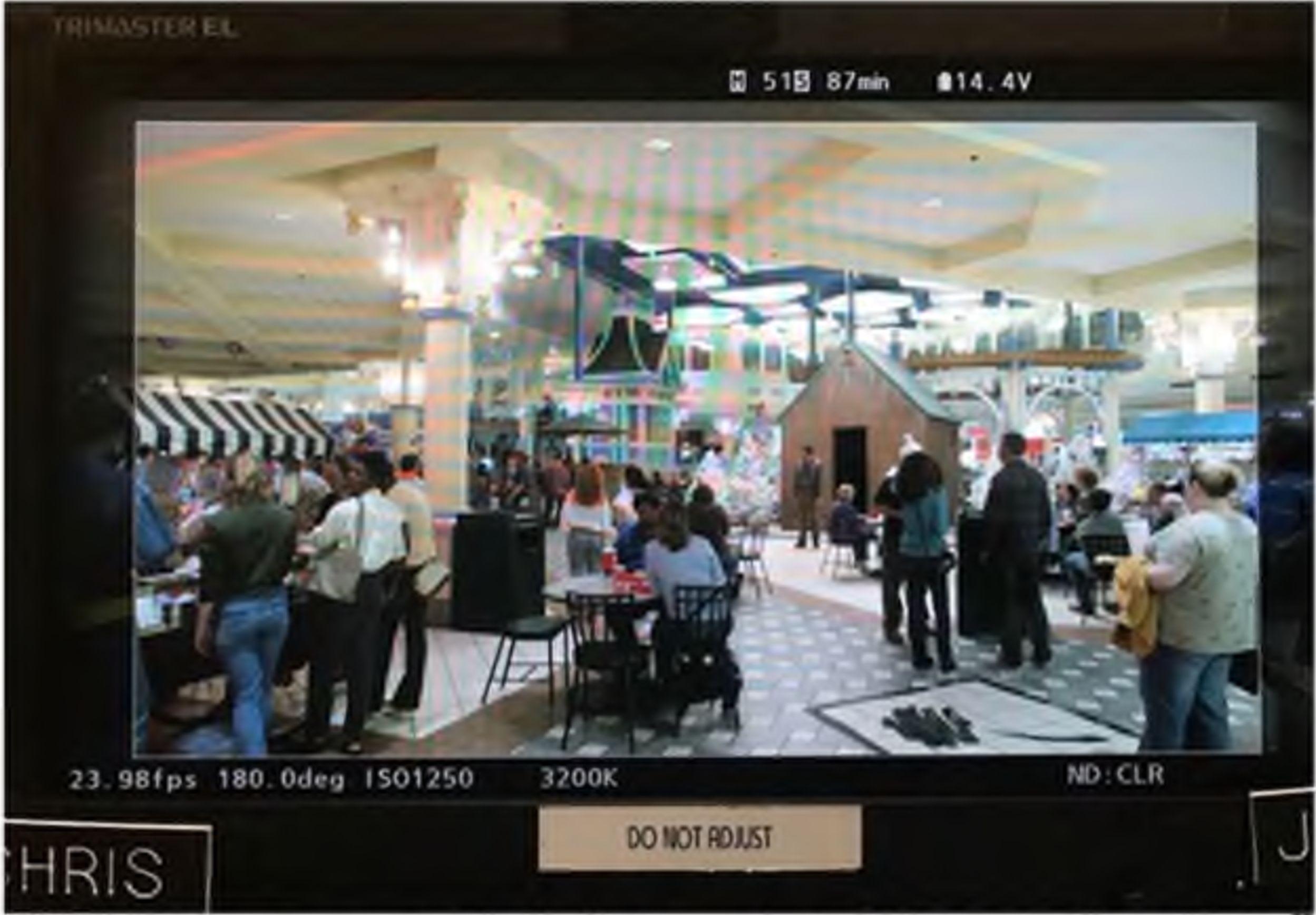

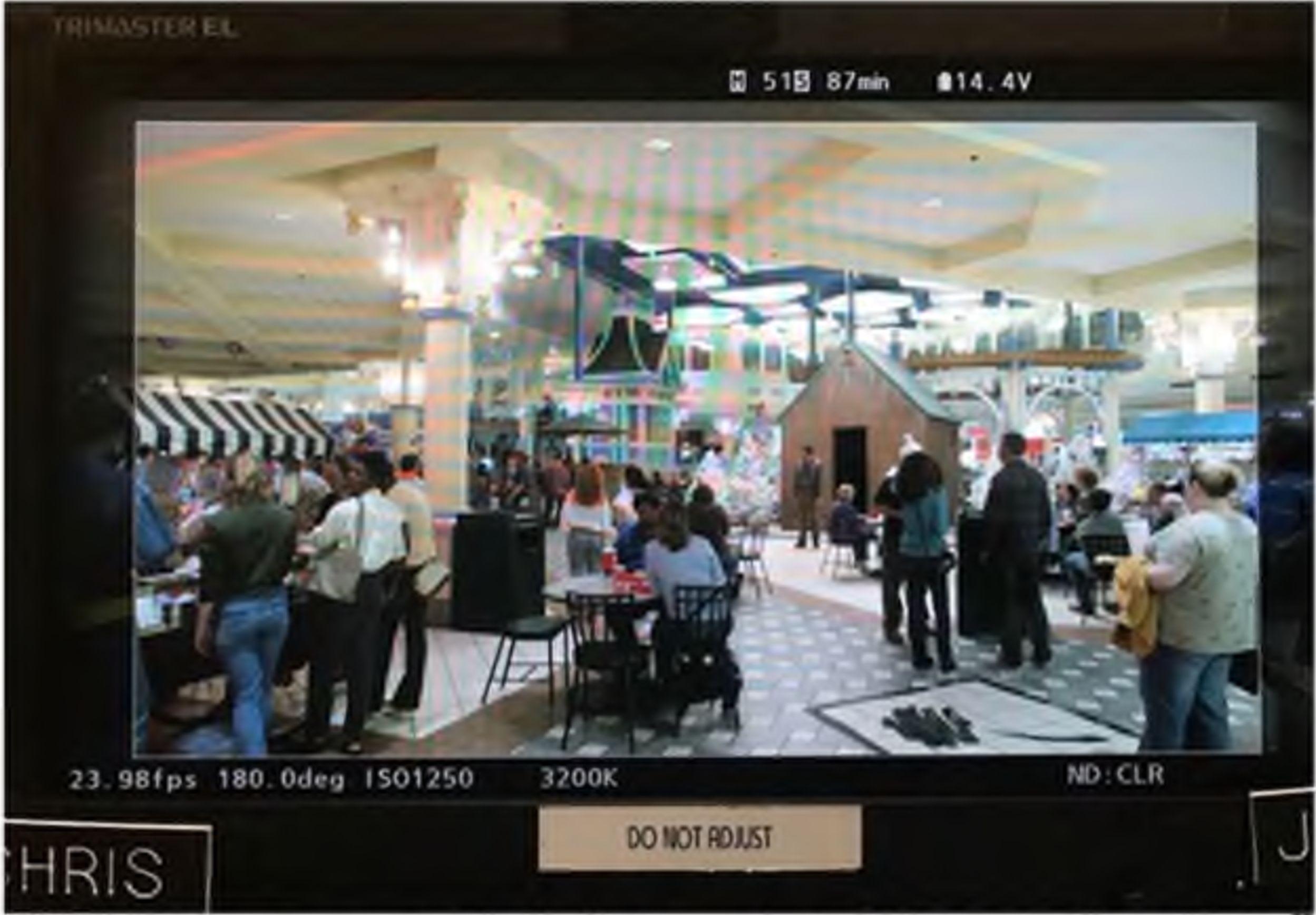

The construction of the log house for the filming of Manhunt was a process that took considerable time and effort. In our interview, Greg Yaitanes, director of the series, said that his intention was recreate Kaczynski's house down to the smallest detail[81] To do this, Yaitanes went on a work trip to visit the Newseum in Washington DC, where the terrorist's house was on display. On that occasion, he observed and took photos to reconstruct “every inch and texture”. Furthermore, he revealed that the interior of the house was the only element filmed in the studio.

The only thing we had in the studio was the inside of his house. We took a work trip to the Newseum in Washington DC, I don't think the house is there anymore, just that back then it was and we studied every inch and texture. It was meticulously recreated, except for the height, because Paul [actor] is taller than Ted, so we added a few inches so he wouldn't be hunched over in there. Excluding that, everything was perfectly recreated. Erik Carlson who did our product design and his team were excellent. We have photos [that allowed us to recreate this and that], the evidence and where things were, we had a lot of documentation [to prove what the house was like] and it was absolutely incredible to recreate[82]

Erik Carlson, responsible for the scenography, commented on the commitment to reproducing the house. Three different versions were built: one that was in the forest, another that could be erected and transported, and the third in the studio for easy filming of the scenes(FIGURES 9 and10). With each new scene, if a different version was used, it became necessary to rearrange and organize the objects.

As an emblematic and recognized element, it was important to reproduce the details in detail: “that house was going to have a central character, being so iconic that it is one of those things that you can put on Google and see where the We made mistakes or we were lazy. We made it closer to reality based on the photos”[85] As the objects in the house were not in the museum, FBI photographs were used [to remake them], as well as the books present in the cabin[86], acquired for the filming , were printed before 1995, the year before Kaczynski's arrest

It was possible to note that the importance of faithfully recreating Kaczynski's log house was, for Yaitanes, another of the elements that legitimized the series as “extremely based on facts”[87]. According to him, this provided "credibility” and “authenticity” to the narrative. These characteristics were decisive for Discovery executives to support the production of Manhunt.

It is important to highlight that the creative and production workers had different interpretations of the meaning of the log house. The series, as already indicated, featured different versions of the script Tony Gittleson and Andrew Sodroski, at different times, were responsible for two scripts and versions distinct from the series[88] But both were guided by Thoreau when dealing with Kaczynski's house

Sodroski, who wrote the script for the final product, never read Gittleson's original text. The result is that they were contrasting versions of the Unabomber case, yet both used the 19th century philosopher as a reference to think about the domestic terrorist

Gittleson, who kindly provided us with the original script purchased by Discovery (titled Manifesto) begins the first paragraph, or what would be the first scene, describing Kaczynski's house (FIGURE 12)[89]. The screenwriter establishes a direct parallel with Thoreau in Walden. Despite this approach, Gittleson makes clear the difference between the two environments and characters: far from the North American philosopher's paradise of contemplation, that is the pernicious house of the villain[90].

Like Thoreau's house... only in that house everything is evil. Less [close] to the lake in Walden and closer to the fox hole in Little Red Riding Hood. A light snow falls. Slowly we are PULLED... [91]

Gittleson, Sodroski and Kaczynski shared the same references, but with different interpretations[92] They all studied at Harvard (25 km from Walden) and lived in Massachusetts. However, Sodroski, compared to Gittleson, establishes a different relationship with the log house.

In our interview, the screenwriter and showrunner said that the Unabomber's house invokes an aesthetic beauty like Thoreau's. It would be what attracted many people to think about Kaczynski and consequently watch the series. Sodroski recalled, positively, that in his childhood he visited, on multiple occasions, the iconic space where the philosopher's house was located.

The screenwriter demonstrated a certain empathy, but also fascination, when revealing that, during the production of the series, he entered the log house built in the forest, sitting on several occasions “in the same chair as Ted". One of the reasons that motivated him to do this work was to imagine living in the same conditions as Thoreau and Theodore Kaczynski

For me, this is what captivates me. When I think about the Unabomber, I think part of what might draw a lot of people to this story is getting a glimpse of that house. And it looks really pretty, like Thoreau, you know? Thoreau's house. I grew up in Massachusetts and we used to go to Walden Lake all the time, it's a big tourist attraction because people want to imagine that life. So being part of this series for me, [is related] to my own fantasy of putting myself in that world, and could I live in that house? Could you live like that? The house [in the series] was built in the woods and I remember going there and sitting in the same chair as Ted for a long, long time and it's very fascinating.[93]

Thus, in different cycles of the series, whether in creation or production, the central screenwriters started from the reference of Walden. While for Gittleson we had a well-defined opposition between the houses of Thoreau and Kaczynski, with Sodroski there was a convergence There was, in Gittleson's text, something evil in that Kaczynski environment. For Sodroski, there was something beautiful to be glimpsed, imagined and fantasized

British actor Paul Bethany, when promoting the premiere of Manhunt, commented that he had immersed himself to play Theodore Kaczynski Bethany revealed that, for a few days, he sought to live in an isolated house. However, he highlighted that the place it was different from the log house, as it had comforts, such as running water and electricity. The actor sought the experience of isolation, distancing himself from the excesses of contemporary society

Yes, but I had running water and electricity and it was very beautiful, thank you very much, but [...] it was days and weekends, and I think the longest period I was [isolated] was three days. I'm a father, I have to be in contact [with family], but I wanted to experience a kind of solitude for three days. Because we don't have that with all this exchanging of messages, emails, being online all the time and watching the news, and being able to really switch off, not have any of that for three days and not have contact with people [during isolation ]. It's funny that when I went back to work in the morning my voice broke because [during those three days] I didn't need to speak[94]

It is interesting to note that the actor, when he reported his experience, was at a Build series studio in Manhattan. The place, which is on the ground floor of a building, has external walls made of glass. Thus, while the interviewer and interviewee were talking, the audience saw in the background the intense movement of vehicles and pedestrians on the streets of the metropolis, indicating their awareness of Kaczynski's environment and the modern world he criticized

In a similar way, Australian actor Sam Worthington, who played James Fitzgerald, promoting the premiere of Manhunt in a radio program, established a parallel between his individual experience and the series. The actor says that, when turned thirty, sold most of his objects to live in his car Not because of economic necessity, as he was already a recognized actor in Australia On the contrary, in his justification, he reports that excessive consumption was transforming him as an individual, modifying his your behavior and personality. Thus, he saw the solution as a way out of getting rid of his material possessions and living with the bare minimum[95]

Worthington does not quote Thoreau Obviously, as an Australian, North American references were not as striking to him However, he demonstrated awareness of the costs of modern life. The log house is also not literally referenced by the actor, but for him, living in a car passed symbolizing autonomy and rebellion against contemporary society. At the same time, it represented a sign of austerity, living with the minimum, as a counterpoint to the excesses that permeate everyday life.