Anonymous, Snorri Sturluson, William Morris, Jennie Hall, J. Lesslie Hall

Saga Six Pack (Beowulf, The Prose Edda and More)

INTRODUCTION: WHAT THE SAGAS WERE

I. THE LIFE AND DEATH OF SCYLD

II. SCYLD’S SUCCESSORS.—HROTHGAR’S GREAT MEAD-HALL.

IV. BEOWULF GOES TO HROTHGAR’S ASSISTANCE.

VI. BEOWULF INTRODUCES HIMSELF AT THE PALACE.

VIII. HROTHGAR AND BEOWULF.—Continued.

X. BEOWULF SILENCES UNFERTH.—GLEE IS HIGH.

XVI. HROTHGAR LAVISHES GIFTS UPON HIS DELIVERER.

XVII. BANQUET (continued).—THE SCOP’S SONG OF FINN AND HNAEF.

XVIII. THE FINN EPISODE (continued).—THE BANQUET CONTINUES.

XIX. BEOWULF RECEIVES FURTHER HONOR.

XXI. HROTHGAR’S ACCOUNT OF THE MONSTERS.

XXII. BEOWULF SEEKS GRENDEL’S MOTHER.

XXIII. BEOWULF’S FIGHT WITH GRENDEL’S MOTHER.

XXIV. BEOWULF IS DOUBLE-CONQUEROR.

XXV. BEOWULF BRINGS HIS TROPHIES.—HROTHGAR’S GRATITUDE.

XXVI. HROTHGAR MORALIZES.—REST AFTER LABOR.

XXVIII. THE HOMEWARD JOURNEY.—THE TWO QUEENS.

XXX. BEOWULF NARRATES HIS ADVENTURES TO HIGELAC.

XXXII. THE HOARD AND THE DRAGON.

XXXIII. BRAVE THOUGH AGED.—REMINISCENCES.

XXXIV. BEOWULF SEEKS THE DRAGON.—BEOWULF’S REMINISCENCES.

XXXV. REMINISCENCES (continued).—BEOWULF’S LAST BATTLE.

XXXVI. WIGLAF THE TRUSTY.—BEOWULF IS DESERTED BY FRIENDS AND BY SWORD.

XXXVII. THE FATAL STRUGGLE.—BEOWULF’S LAST MOMENTS.

XXXVIII. WIGLAF PLUNDERS THE DRAGON’S DEN.—BEOWULF’S DEATH.

XXXIX. THE DEAD FOES.—WIGLAF’S BITTER TAUNTS.

XLI. THE MESSENGER’S RETROSPECT.

XLII. WIGLAF’S SAD STORY.—THE HOARD CARRIED OFF.

XLIII. THE BURNING OF BEOWULF.

THE STORY OF GUNNLAUG THE WORM-TONGUE AND RAVEN THE SKALD

CHAPTER I. Of Thorstein Egilson and his Kin.

CHAPTER II. Of Thorsteins Dream.

CHAPTER III. Of the Birth and Fostering of Helga the Fair.

CHAPTER IV. Of Gunnlaug Worm-tongue and his Kin.

CHAPTER V. Of Raven and his Kin.

CHAPTER VI. How Helga was vowed to Gunnlaug, and of Gunnlaug's faring abroad.

CHAPTER VII. Of Gunnlaug in the East and the West.

CHAPTER VIII. Of Gunnlaug in Ireland.

CHAPTER IX. Of the Quarrel between Gunnlaug and Raven before the Swedish King.

CHAPTER X. How Raven came home to Iceland, and asked for Helga to Wife.

CHAPTER XI. Of how Gunnlaug must needs abide away from Iceland.

CHAPTER XII. Of Gunnlaug's landing, and how he found Helga wedded to Raven.

CHAPTER XIII. Of the Winter-Wedding at Skaney, and how Gunnlaug gave the Kings Cloak to Helga.

CHAPTER XIV. Of the Holmgang at the Althing.

CHAPTER XV. How Gunnlaug and Raven agreed to go East to Norway, to try the matter again.

CHAPTER XVI. How the two Foes met and fought at Dingness.

CHAPTER XVII. The News of the Fight brought to Iceland.

[Copyright]

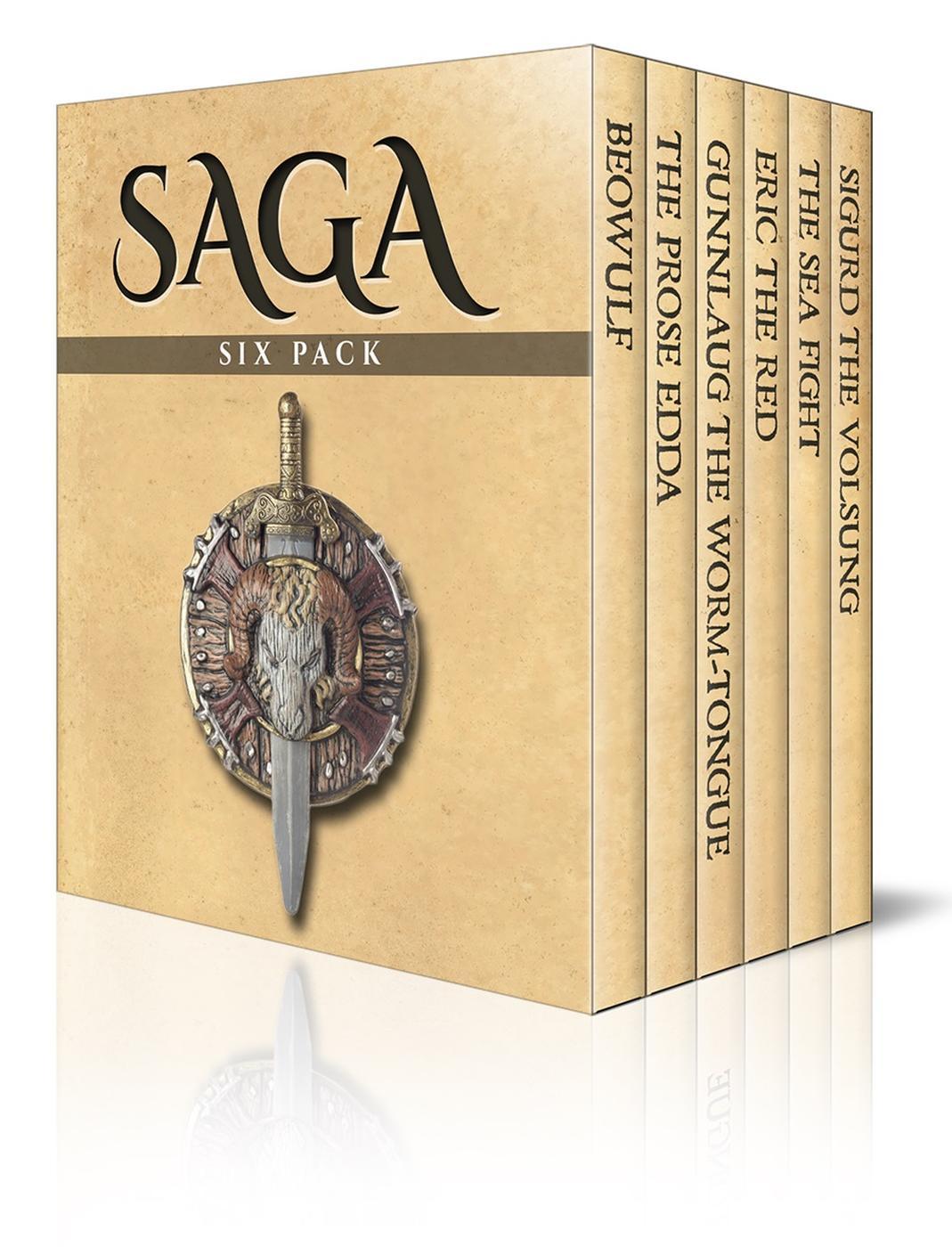

SAGA SIX PACK

BEOWULF

THE PROSE EDDA

GUNNLAUG THE WORM-TONGUE AND RAVEN THE SKALD

ERIC THE RED

THE SEA FIGHT

SIGURD THE VOLSUNG

Saga Six Pack – Beowulf, The Prose Edda, Gunnlaugh The Worm-Tongue and Raven the Skald, Eric The Red, The Sea Fight, Sigurd the Volsung.

Beowulf by Anonymous. Translated by J. Lesslie Hall. First published in 1892. Originally published in manuscript form c. 975–1025. Date of poem - c. 700–1000.

The Prose Edda by Snorri Sturluson. Translated by Arthur Gilchrist Brodeur. First published in 1916. Originally written or compiled c. 1220.

The Story Of Gunnlaug The Worm-Tongue and Raven The Skald by Anonymous. Translated by William Morris. First published in 1875. Originally written at end of 13th Century.

Eric The Red and The Sea Fight from Viking Tales by Jennie Hall. First published in 1902.

Sigurd The Volsung by William Morris. First published in 1876.

What The Sagas Were by Jennie Hall. From Viking Tales by Jennie Hall. First published in 1902.

This book or any portion thereof may not be reproduced or used in any manner whatsoever without the express written permission of the publisher except for the use of brief quotations in a book review.

Printed in the United States of America.

First printing, 2015.

Enhanced Media Publishing.

Copyright © Enhanced Media 2015.

All rights reserved.

SAGA SIX PACK

INTRODUCTION: WHAT THE SAGAS WERE

Iceland is a little country far north in the cold sea. Men found it and went there to live more than a thousand years ago. During the warm season they used to fish and make fish-oil and hunt sea-birds and gather feathers and tend their sheep and make hay. But the winters were long and dark and cold. Men and women and children stayed in the house and carded and spun and wove and knit. A whole family sat for hours around the fire in the middle of the room. That fire gave the only light. Shadows flitted in the dark corners. Smoke curled along the high beams in the ceiling. The children sat on the dirt floor close by the fire. The grown people were on a long narrow bench that they had pulled up to the light and warmth. Everybody's hands were busy with wool. The work left their minds free to think and their lips to talk. What was there to talk about? The summer's fishing, the killing of a fox, a voyage to Norway. But the people grew tired of this little gossip. Fathers looked at their children and thought:

"They are not learning much. What will make them brave and wise? What will teach them to love their country and old Norway? Will not the stories of battles, of brave deeds, of mighty men, do this?"

So, as the family worked in the red fire-light, the father told of the kings of Norway, of long voyages to strange lands, of good fights. And in farmhouses all through Iceland these old tales were told over and over until everybody knew them and loved them. Some men could sing and play the harp. This made the stories all the more interesting. People called such men "skalds," and they called their songs "sagas."

Every midsummer there was a great meeting. Men from all over Iceland came to it and made laws. During the day there were rest times, when no business was going on. Then some skald would take his harp and walk to a large stone or a knoll and stand on it and begin a song of some brave deed of an old Norse hero. At the first sound of the harp and the voice, men came running from all directions, crying out:

"The skald! The skald! A saga!"

They stood about for hours and listened. They shouted applause. When the skald was tired, some other man would come up from the crowd and sing or tell a story. As the skald stepped down from his high position, some rich man would rush up to him and say:

"Come and spend next winter at my house. Our ears are thirsty for song."

So the best skalds traveled much and visited many people. Their songs made them welcome everywhere. They were always honored with good seats at a feast. They were given many rich gifts. Even the King of Norway would sometimes send across the water to Iceland, saying to some famous skald:

"Come and visit me. You shall not go away empty-handed. Men say that the sweetest songs are in Iceland. I wish to hear them."

These tales were not written. Few men wrote or read in those days. Skalds learned songs from hearing them sung. At last people began to write more easily. Then they said:

"These stories are very precious. We must write them down to save them from being forgotten."

After that many men in Iceland spent their winters in writing books. They wrote on sheepskin; vellum, we call it. Many of these old vellum books have been saved for hundreds of years, and are now in museums in Norway. Some leaves are lost, some are torn, all are yellow and crumpled. But they are precious. They tell us all that we know about that olden time. There are the very words that the men of Iceland wrote so long ago—stories of kings and of battles and of ship-sailing. Some of the more famous Icelandic stories are presented in this book, as well as examples from other Northern European countries like Denmark, Germany and England.

BEOWULF

By Anonymous

Translated by J. Lesslie Hall

I. THE LIFE AND DEATH OF SCYLD

The famous race of Spear-Danes

The folk-kings’ former fame we have heard of,

How princes displayed then their prowess-in-battle.

Oft Scyld the Scefing from scathers in numbers

From many a people their mead-benches tore.

Since first he found him friendless and wretched,

The earl had had terror: comfort he got for it,

Waxed ’neath the welkin, world-honor gained,

Till all his neighbors o’er sea were compelled to

Bow to his bidding and bring him their tribute:

A son and heir, young in his dwelling,

Whom God-Father sent to solace the people.

He had marked the misery malice had caused them,

That reaved of their rulers they wretched had erstwhile

Long been afflicted. The Lord, in requital,

Wielder of Glory, with world-honor blessed him.

Famed was Beowulf, far spread the glory

Of Scyld’s great son in the lands of the Danemen.

The ideal Teutonic king lavishes gifts on his vassals.

So the carle that is young, by kindnesses rendered

The friends of his father, with fees in abundance

Must be able to earn that when age approacheth

Eager companions aid him requitingly,

When war assaults him serve him as liegemen:

’Mong all of the races. At the hour that was fated

Scyld dies at the hour appointed by Fate.

Scyld then departed to the All-Father’s keeping

Warlike to wend him; away then they bare him

To the flood of the current, his fond-loving comrades,

As himself he had bidden, while the friend of the Scyldings

Word-sway wielded, and the well-lovèd land-prince

Long did rule them. The ring-stemmèd vessel,

Bark of the atheling, lay there at anchor,

Icy in glimmer and eager for sailing;

By his own request, his body is laid on a vessel and wafted seaward.

The belovèd leader laid they down there,

Giver of rings, on the breast of the vessel,

The famed by the mainmast. A many of jewels,

Of fretted embossings, from far-lands brought over,

Was placed near at hand then; and heard I not ever

That a folk ever furnished a float more superbly

With weapons of warfare, weeds for the battle,

Bills and burnies; on his bosom sparkled

Many a jewel that with him must travel

On the flush of the flood afar on the current.

And favors no fewer they furnished him soothly,

Excellent folk-gems, than others had given him

He leaves Daneland on the breast of a bark.

Who when first he was born outward did send him

Lone on the main, the merest of infants:

High o’er his head, let the holm-currents bear him,

Seaward consigned him: sad was their spirit,

Their mood very mournful. Men are not able

No one knows whither the boat drifted.

Soothly to tell us, they in halls who reside,

Heroes under heaven, to what haven he hied.

II. SCYLD’S SUCCESSORS.—HROTHGAR’S GREAT MEAD-HALL.

Beowulf succeeds his father Scyld

Belovèd land-prince, for long-lasting season

Was famed mid the folk (his father departed,

The prince from his dwelling), till afterward sprang

Great-minded Healfdene; the Danes in his lifetime

He graciously governed, grim-mooded, agèd.

Four bairns of his body born in succession

Woke in the world, war-troopers’ leader

Heorogar, Hrothgar, and Halga the good;

Heard I that Elan was Ongentheow’s consort,

The well-beloved bedmate of the War-Scylfing leader.

Then glory in battle to Hrothgar was given,

Waxing of war-fame, that willingly kinsmen

Obeyed his bidding, till the boys grew to manhood,

A numerous band. It burned in his spirit

To urge his folk to found a great building,

A mead-hall grander than men of the era

Ever had heard of, and in it to share

With young and old all of the blessings

The Lord had allowed him, save life and retainers.

Then the work I find afar was assigned

To many races in middle-earth’s regions,

To adorn the great folk-hall. In due time it happened

Early ’mong men, that ’twas finished entirely,

The greatest of hall-buildings; Heorot he named it

The hall is completed, and is called Heort, or Heorot.

Who wide-reaching word-sway wielded ’mong earlmen.

His promise he brake not, rings he lavished,

Treasure at banquet. Towered the hall up

High and horn-crested, huge between antlers:

Ere long then from hottest hatred must sword-wrath

Arise for a woman’s husband and father.

Then the mighty war-spirit endured for a season,

Bore it bitterly, he who bided in darkness,

That light-hearted laughter loud in the building

Greeted him daily; there was dulcet harp-music,

Clear song of the singer. He said that was able

To tell from of old earthmen’s beginnings,

That Father Almighty earth had created,

The winsome wold that the water encircleth,

Set exultingly the sun’s and the moon’s beams

To lavish their lustre on land-folk and races,

And earth He embellished in all her regions

With limbs and leaves; life He bestowed too

On all the kindreds that live under heaven.

The glee of the warriors is overcast by a horrible dread.

So blessed with abundance, brimming with joyance,

The warriors abided, till a certain one gan to

Dog them with deeds of direfullest malice,

A foe in the hall-building: this horrible stranger

Was Grendel entitled, the march-stepper famous

Who dwelt in the moor-fens, the marsh and the fastness;

The wan-mooded being abode for a season

In the land of the giants, when the Lord and Creator

Had banned him and branded. For that bitter murder,

The killing of Abel, all-ruling Father

The kindred of Cain crushed with His vengeance;

In the feud He rejoiced not, but far away drove him

From kindred and kind, that crime to atone for,

Meter of Justice. Thence ill-favored creatures,

Elves and giants, monsters of ocean,

Came into being, and the giants that longtime

Grappled with God; He gave them requital.

III. GRENDEL THE MURDERER.

Grendel attacks the sleeping heroes

The lofty hall-building, how the Ring-Danes had used it

For beds and benches when the banquet was over.

Then he found there reposing many a noble

Asleep after supper; sorrow the heroes,

Misery knew not. The monster of evil

Greedy and cruel tarried but little,

He drags off thirty of them, and devours them

Fell and frantic, and forced from their slumbers

Thirty of thanemen; thence he departed

Leaping and laughing, his lair to return to,

With surfeit of slaughter sallying homeward.

In the dusk of the dawning, as the day was just breaking,

Was Grendel’s prowess revealed to the warriors:

Morning-cry mighty. The man-ruler famous,

The long-worthy atheling, sat very woeful,

Suffered great sorrow, sighed for his liegemen,

When they had seen the track of the hateful pursuer,

The spirit accursèd: too crushing that sorrow,

Too loathsome and lasting. Not longer he tarried,

But one night after continued his slaughter

Shameless and shocking, shrinking but little

From malice and murder; they mastered him fully.

He was easy to find then who otherwhere looked for

A pleasanter place of repose in the lodges,

A bed in the bowers. Then was brought to his notice

Told him truly by token apparent

The hall-thane’s hatred: he held himself after

Further and faster who the foeman did baffle.

So ruled he and strongly strove against justice

Lone against all men, till empty uptowered

King Hrothgar’s agony and suspense last twelve years.

The choicest of houses. Long was the season:

The friend of the Scyldings, every affliction,

Endless agony; hence it after became

Certainly known to the children of men

Sadly in measures, that long against Hrothgar

Grendel struggled:—his grudges he cherished,

Murderous malice, many a winter,

Strife unremitting, and peacefully wished he

Life-woe to lift from no liegeman at all of

The men of the Dane-folk, for money to settle,

No counsellor needed count for a moment

On handsome amends at the hands of the murderer;

Grendel is unremitting in his persecutions.

The monster of evil fiercely did harass,

The ill-planning death-shade, both elder and younger,

Trapping and tricking them. He trod every night then

The mist-covered moor-fens; men do not know where

Witches and wizards wander and ramble.

So the foe of mankind many of evils

Grievous injuries, often accomplished,

Horrible hermit; Heort he frequented,

Gem-bedecked palace, when night-shades had fallen

(Since God did oppose him, not the throne could he touch,

The light-flashing jewel, love of Him knew not).

’Twas a fearful affliction to the friend of the Scyldings

The king and his council deliberate in vain.

Soul-crushing sorrow. Not seldom in private

Sat the king in his council; conference held they

What the braves should determine ’gainst terrors unlooked for.

They invoke the aid of their gods.

At the shrines of their idols often they promised

Gifts and offerings, earnestly prayed they

The devil from hell would help them to lighten

Their people’s oppression. Such practice they used then,

Hope of the heathen; hell they remembered

In innermost spirit, God they knew not,

The true God they do not know.

Judge of their actions, All-wielding Ruler,

No praise could they give the Guardian of Heaven,

The Wielder of Glory. Woe will be his who

Through furious hatred his spirit shall drive to

The clutch of the fire, no comfort shall look for,

Wax no wiser; well for the man who,

Living his life-days, his Lord may face

And find defence in his Father’s embrace!

IV. BEOWULF GOES TO HROTHGAR’S ASSISTANCE.

Hrothgar sees no way of escape from the persecutions of Grendel

His long-lasting sorrow; the battle-thane clever

Was not anywise able evils to ’scape from:

Loathsome and lasting the life-grinding torture,

Greatest of night-woes. So Higelac’s liegeman,

Good amid Geatmen, of Grendel’s achievements

Heard in his home: of heroes then living

He was stoutest and strongest, sturdy and noble.

He bade them prepare him a bark that was trusty;

He said he the war-king would seek o’er the ocean,

The folk-leader noble, since he needed retainers.

For the perilous project prudent companions

Chided him little, though loving him dearly;

They egged the brave atheling, augured him glory.

The excellent knight from the folk of the Geatmen

Had liegemen selected, likest to prove them

Trustworthy warriors; with fourteen companions

The vessel he looked for; a liegeman then showed them,

A sea-crafty man, the bounds of the country.

Fast the days fleeted; the float was a-water,

The craft by the cliff. Clomb to the prow then

Well-equipped warriors: the wave-currents twisted

The sea on the sand; soldiers then carried

On the breast of the vessel bright-shining jewels,

Handsome war-armor; heroes outshoved then,

Warmen the wood-ship, on its wished-for adventure.

The foamy-necked floater fanned by the breeze,

Likest a bird, glided the waters,

Till twenty and four hours thereafter

The twist-stemmed vessel had traveled such distance

That the sailing-men saw the sloping embankments,

The sea cliffs gleaming, precipitous mountains,

Nesses enormous: they were nearing the limits

At the end of the ocean. Up thence quickly

The men of the Weders clomb to the mainland,

Fastened their vessel (battle weeds rattled,

War burnies clattered), the Wielder they thanked

That the ways o’er the waters had waxen so gentle.

They are hailed by the Danish coast guard

Then well from the cliff edge the guard of the Scyldings

Who the sea-cliffs should see to, saw o’er the gangway

Brave ones bearing beauteous targets,

Armor all ready, anxiously thought he,

Musing and wondering what men were approaching.

High on his horse then Hrothgar’s retainer

Turned him to coastward, mightily brandished

His lance in his hands, questioned with boldness.

“Who are ye men here, mail-covered warriors

Clad in your corslets, come thus a-driving

A high riding ship o’er the shoals of the waters,

And hither ’neath helmets have hied o’er the ocean?

I have been strand-guard, standing as warden,

Lest enemies ever anywise ravage

Danish dominions with army of war-ships.

More boldly never have warriors ventured

Hither to come; of kinsmen’s approval,

Word-leave of warriors, I ween that ye surely

He is struck by Beowulf’s appearance.

Nothing have known. Never a greater one

Of earls o’er the earth have I had a sight of

Than is one of your number, a hero in armor;

No low-ranking fellow adorned with his weapons,

But launching them little, unless looks are deceiving,

And striking appearance. Ere ye pass on your journey

As treacherous spies to the land of the Scyldings

And farther fare, I fully must know now

What race ye belong to. Ye far-away dwellers,

Sea-faring sailors, my simple opinion

Hear ye and hearken: haste is most fitting

Plainly to tell me what place ye are come from.”

V. THE GEATS REACH HEOROT.

Beowulf courteously replies

War-troopers’ leader, and word-treasure opened:

And Higelac’s hearth-friends. To heroes unnumbered

My father Ecgtheow was well-known in his day.

My father was known, a noble head-warrior

Ecgtheow titled; many a winter

He lived with the people, ere he passed on his journey,

Old from his dwelling; each of the counsellors

Widely mid world-folk well remembers him.

Our intentions towards King Hrothgar are of the kindest.

We, kindly of spirit, the lord of thy people,

The son of King Healfdene, have come here to visit,

Folk-troop’s defender: be free in thy counsels!

To the noble one bear we a weighty commission,

The helm of the Danemen; we shall hide, I ween,

Is it true that a monster is slaying Danish heroes?

Naught of our message. Thou know’st if it happen,

As we soothly heard say, that some savage despoiler,

Some hidden pursuer, on nights that are murky

By deeds very direful ’mid the Danemen exhibits

Hatred unheard of, horrid destruction

And the falling of dead. From feelings least selfish

I can help your king to free himself from this horrible creature.

I am able to render counsel to Hrothgar,

How he, wise and worthy, may worst the destroyer,

If the anguish of sorrow should ever be lessened,

Comfort come to him, and care-waves grow cooler,

Or ever hereafter he agony suffer

And troublous distress, while towereth upward

The handsomest of houses high on the summit.”

The coast-guard reminds Beowulf that it is easier to say than to do.

Bestriding his stallion, the strand-watchman answered,

The doughty retainer: “The difference surely

’Twixt words and works, the warlike shield-bearer

Who judgeth wisely well shall determine.

This band, I hear, beareth no malice

I am satisfied of your good intentions, and shall lead you to the palace.

To the prince of the Scyldings. Pass ye then onward

With weapons and armor. I shall lead you in person;

To my war-trusty vassals command I shall issue

To keep from all injury your excellent vessel,

Your boat shall be well cared for during your stay here.

Your fresh-tarred craft, ’gainst every opposer

Close by the sea-shore, till the curved-neckèd bark shall

Waft back again the well-beloved hero

O’er the way of the water to Weder dominions.

He again compliments Beowulf.

To warrior so great ’twill be granted sure

In the storm of strife to stand secure.”

Onward they fared then (the vessel lay quiet,

The broad-bosomed bark was bound by its cable,

Firmly at anchor); the boar-signs glistened

Bright on the visors vivid with gilding,

Blaze-hardened, brilliant; the boar acted warden.

The heroes hastened, hurried the liegemen,

The land is perhaps rolling.

Descended together, till they saw the great palace,

The well-fashioned wassail-hall wondrous and gleaming:

’Mid world-folk and kindreds that was widest reputed

Of halls under heaven which the hero abode in;

Its lustre enlightened lands without number.

Then the battle-brave hero showed them the glittering

Court of the bold ones, that they easily thither

Might fare on their journey; the aforementioned warrior

Turning his courser, quoth as he left them:

“’Tis time I were faring; Father Almighty

Grant you His grace, and give you to journey

Safe on your mission! To the sea I will get me

’Gainst hostile warriors as warden to stand.”

VI. BEOWULF INTRODUCES HIMSELF AT THE PALACE.

A by-path led the liegemen together.

Firm and hand-locked the war-burnie glistened,

The ring-sword radiant rang ’mid the armor

As the party was approaching the palace together

They set their arms and armor against the wall.

In warlike equipments. ’Gainst the wall of the building

Their wide-fashioned war-shields they weary did set then,

Battle-shields sturdy; benchward they turned then;

Their battle-sarks rattled, the gear of the heroes;

The lances stood up then, all in a cluster,

The arms of the seamen, ashen-shafts mounted

With edges of iron: the armor-clad troopers

Were decked with weapons. Then a proud-mooded hero

Asked of the champions questions of lineage:

Gilded and gleaming, your gray-colored burnies,

Helmets with visors and heap of war-lances?—

To Hrothgar the king I am servant and liegeman.

’Mong folk from far-lands found I have never

Men so many of mien more courageous.

I ween that from valor, nowise as outlaws,

But from greatness of soul ye sought for King Hrothgar.”

Then the strength-famous earlman answer rendered,

The proud-mooded Wederchief replied to his question,

We are Higelac’s table-companions, and bear an important commission to your prince.

Hardy ’neath helmet: “Higelac’s mates are we;

Beowulf hight I. To the bairn of Healfdene,

The famous folk-leader, I freely will tell

To thy prince my commission, if pleasantly hearing

He’ll grant we may greet him so gracious to all men.”

Wulfgar replied then (he was prince of the Wendels,

His boldness of spirit was known unto many,

His prowess and prudence): “The prince of the Scyldings,

Wulfgar, the thane, says that he will go and ask Hrothgar whether he will see the strangers.

The friend-lord of Danemen, I will ask of thy journey,

The giver of rings, as thou urgest me do it,

The folk-chief famous, and inform thee early

What answer the good one mindeth to render me.”

He turned then hurriedly where Hrothgar was sitting,

Old and hoary, his earlmen attending him;

The strength-famous went till he stood at the shoulder

Of the lord of the Danemen, of courteous thanemen

The custom he minded. Wulfgar addressed then

His friendly liegelord: “Folk of the Geatmen

He thereupon urges his liegelord to receive the visitors courteously.

O’er the way of the waters are wafted hither,

Faring from far-lands: the foremost in rank

The battle-champions Beowulf title.

They make this petition: with thee, O my chieftain,

To be granted a conference; O gracious King Hrothgar,

Friendly answer refuse not to give them!

Hrothgar, too, is struck with Beowulf’s appearance.

In war-trappings weeded worthy they seem

Of earls to be honored; sure the atheling is doughty

Who headed the heroes hitherward coming.”

VII. HROTHGAR AND BEOWULF.

Hrothgar remembers Beowulf as a youth, and also remembers his father

His father long dead now was Ecgtheow titled,

Him Hrethel the Geatman granted at home his

One only daughter; his battle-brave son

Is come but now, sought a trustworthy friend.

Seafaring sailors asserted it then,

Beowulf is reported to have the strength of thirty men.

Who valuable gift-gems of the Geatmen carried

As peace-offering thither, that he thirty men’s grapple

Has in his hand, the hero-in-battle.

God hath sent him to our rescue.

The holy Creator usward sent him,

To West-Dane warriors, I ween, for to render

’Gainst Grendel’s grimness gracious assistance:

Hasten to bid them hither to speed them,

To see assembled this circle of kinsmen;

Tell them expressly they’re welcome in sooth to

The men of the Danes.” To the door of the building

Wulfgar went then, this word-message shouted:

The East-Danes’ atheling, that your origin knows he,

And o’er wave-billows wafted ye welcome are hither,

Valiant of spirit. Ye straightway may enter

Clad in corslets, cased in your helmets,

To see King Hrothgar. Here let your battle-boards,

Wood-spears and war-shafts, await your conferring.”

The mighty one rose then, with many a liegeman,

An excellent thane-group; some there did await them,

And as bid of the brave one the battle-gear guarded.

Together they hied them, while the hero did guide them,

’Neath Heorot’s roof; the high-minded went then

Sturdy ’neath helmet till he stood in the building.

Beowulf spake (his burnie did glisten,

His armor seamed over by the art of the craftsman):

“Hail thou, Hrothgar! I am Higelac’s kinsman

And vassal forsooth; many a wonder

I dared as a stripling. The doings of Grendel,

In far-off fatherland I fully did know of:

Excellent edifice, empty and useless

To all the earlmen after evenlight’s glimmer

’Neath heaven’s bright hues hath hidden its glory.

This my earls then urged me, the most excellent of them,

Carles very clever, to come and assist thee,

Folk-leader Hrothgar; fully they knew of

His fight with the nickers.

The strength of my body. Themselves they beheld me

When I came from the contest, when covered with gore

Foes I escaped from, where five I had bound,

The giant-race wasted, in the waters destroying

The nickers by night, bore numberless sorrows,

The Weders avenged (woes had they suffered)

Enemies ravaged; alone now with Grendel

He intends to fight Grendel unaided.

I shall manage the matter, with the monster of evil,

The giant, decide it. Thee I would therefore

Beg of thy bounty, Bright-Danish chieftain,

Lord of the Scyldings, this single petition:

Friend-lord of folks, so far have I sought thee,

That I may unaided, my earlmen assisting me,

This brave-mooded war-band, purify Heorot.

I have heard on inquiry, the horrible creature

Since the monster uses no weapons,

From veriest rashness recks not for weapons;

I this do scorn then, so be Higelac gracious,

My liegelord belovèd, lenient of spirit,

To bear a blade or a broad-fashioned target,

A shield to the onset; only with hand-grip

I, too, shall disdain to use any.

The foe I must grapple, fight for my life then,

Foeman with foeman; he fain must rely on

The doom of the Lord whom death layeth hold of.

Should he crush me, he will eat my companions as he has eaten thy thanes.

I ween he will wish, if he win in the struggle,

To eat in the war-hall earls of the Geat-folk,

Boldly to swallow them, as of yore he did often

The best of the Hrethmen! Thou needest not trouble

A head-watch to give me; he will have me dripping

In case of my defeat, thou wilt not have the trouble of burying me.

And dreary with gore, if death overtake me,

Will bear me off bleeding, biting and mouthing me,

The hermit will eat me, heedless of pity,

Marking the moor-fens; no more wilt thou need then

Should I fall, send my armor to my lord, King Higelac.

Find me my food. If I fall in the battle,

Send to Higelac the armor that serveth

To shield my bosom, the best of equipments,

Richest of ring-mails; ’tis the relic of Hrethla,

Weird is supreme

The work of Wayland. Goes Weird as she must go!”

VIII. HROTHGAR AND BEOWULF.—Continued.

Hrothgar responds

Thou soughtest us hither, good friend Beowulf.

Reminiscences of Beowulf’s father, Ecgtheow.

The fiercest of feuds thy father engaged in,

Heatholaf killed he in hand-to-hand conflict

’Mid Wilfingish warriors; then the Wederish people

For fear of a feud were forced to disown him.

Thence flying he fled to the folk of the South-Danes,

The race of the Scyldings, o’er the roll of the waters;

I had lately begun then to govern the Danemen,

The hoard-seat of heroes held in my youth,

Rich in its jewels: dead was Heregar,

My kinsman and elder had earth-joys forsaken,

Healfdene his bairn. He was better than I am!

That feud thereafter for a fee I compounded;

O’er the weltering waters to the Wilfings I sent

Ornaments old; oaths did he swear me.

Hrothgar recounts to Beowulf the horrors of Grendel’s persecutions.

It pains me in spirit to any to tell it,

What grief in Heorot Grendel hath caused me,

What horror unlooked-for, by hatred unceasing.

Waned is my war-band, wasted my hall-troop;

Weird hath offcast them to the clutches of Grendel.

God can easily hinder the scather

From deeds so direful. Oft drunken with beer

My thanes have made many boasts, but have not executed them.

O’er the ale-vessel promised warriors in armor

They would willingly wait on the wassailing-benches

A grapple with Grendel, with grimmest of edges.

Then this mead-hall at morning with murder was reeking,

The building was bloody at breaking of daylight,

The bench-deals all flooded, dripping and bloodied,

The folk-hall was gory: I had fewer retainers,

Dear-beloved warriors, whom death had laid hold of.

Sit down to the feast, and give us comfort.

Sit at the feast now, thy intents unto heroes,

Thy victor-fame show, as thy spirit doth urge thee!”

A bench is made ready for Beowulf and his party.

For the men of the Geats then together assembled,

In the beer-hall blithesome a bench was made ready;

There warlike in spirit they went to be seated,

Proud and exultant. A liegeman did service,

Who a beaker embellished bore with decorum,

The gleeman sings

And gleaming-drink poured. The gleeman sang whilom

The heroes all rejoice together.

Hearty in Heorot; there was heroes’ rejoicing,

A numerous war-band of Weders and Danemen.

IX. UNFERTH TAUNTS BEOWULF.

Unferth, a thane of Hrothgar, is jealous of Beowulf, and undertakes to twit him

Who sat at the feet of the lord of the Scyldings,

Opened the jousting (the journey of Beowulf,

Sea-farer doughty, gave sorrow to Unferth

And greatest chagrin, too, for granted he never

That any man else on earth should attain to,

Gain under heaven, more glory than he):

“Art thou that Beowulf with Breca did struggle,

On the wide sea-currents at swimming contended,

Where to humor your pride the ocean ye tried,

’Twas mere folly that actuated you both to risk your lives on the ocean.

From vainest vaunting adventured your bodies

In care of the waters? And no one was able

Nor lief nor loth one, in the least to dissuade you

Your difficult voyage; then ye ventured a-swimming,

Where your arms outstretching the streams ye did cover,

The mere-ways measured, mixing and stirring them,

Glided the ocean; angry the waves were,

With the weltering of winter. In the water’s possession,

Ye toiled for a seven-night; he at swimming outdid thee,

In strength excelled thee. Then early at morning

On the Heathoremes’ shore the holm-currents tossed him,

Sought he thenceward the home of his fathers,

Beloved of his liegemen, the land of the Brondings,

The peace-castle pleasant, where a people he wielded,

Had borough and jewels. The pledge that he made thee

Breca outdid you entirely.

The son of Beanstan hath soothly accomplished.

Then I ween thou wilt find thee less fortunate issue,

Much more will Grendel outdo you, if you vie with him in prowess.

Though ever triumphant in onset of battle,

A grim grappling, if Grendel thou darest

For the space of a night near-by to wait for!”

Beowulf answered, offspring of Ecgtheow:

O friend Unferth, you are fuddled with beer, and cannot talk coherently.

Thou fuddled with beer of Breca hast spoken,

Hast told of his journey! A fact I allege it,

That greater strength in the waters I had then,

Ills in the ocean, than any man else had.

We made agreement as the merest of striplings

Promised each other (both of us then were

We simply kept an engagement made in early life.

Younkers in years) that we yet would adventure

Out on the ocean; it all we accomplished.

While swimming the sea-floods, sword-blade unscabbarded

Boldly we brandished, our bodies expected

To shield from the sharks. He sure was unable

He could not excel me, and I would not excel him.

To swim on the waters further than I could,

More swift on the waves, nor would I from him go.

Then we two companions stayed in the ocean

After five days the currents separated us.

Five nights together, till the currents did part us,

The weltering waters, weathers the bleakest,

And nethermost night, and the north-wind whistled

Fierce in our faces; fell were the billows.

The mere fishes’ mood was mightily ruffled:

Hand-jointed, hardy, help did afford me;

My battle-sark braided, brilliantly gilded,

A horrible sea-beast attacked me, but I slew him.

Lay on my bosom. To the bottom then dragged me,

A hateful fiend-scather, seized me and held me,

Grim in his grapple: ’twas granted me, nathless,

To pierce the monster with the point of my weapon,

My obedient blade; battle off carried

The mighty mere-creature by means of my hand-blow.

X. BEOWULF SILENCES UNFERTH.—GLEE IS HIGH.

Sorrow the sorest. I served them, in quittance,

My dear sword always served me faithfully.

With my dear-lovèd sword, as in sooth it was fitting;

They missed the pleasure of feasting abundantly,

Ill-doers evil, of eating my body,

Of surrounding the banquet deep in the ocean;

But wounded with edges early at morning

They were stretched a-high on the strand of the ocean,

I put a stop to the outrages of the sea-monsters.

Put to sleep with the sword, that sea-going travelers

No longer thereafter were hindered from sailing

The foam-dashing currents. Came a light from the east,

God’s beautiful beacon; the billows subsided,

That well I could see the nesses projecting,

Fortune helps the brave earl.

The blustering crags. Weird often saveth

The undoomed hero if doughty his valor!

But me did it fortune to fell with my weapon

Nine of the nickers. Of night-struggle harder

’Neath dome of the heaven heard I but rarely,

Nor of wight more woeful in the waves of the ocean;

Yet I ’scaped with my life the grip of the monsters,

After that escape I drifted to Finland.

Weary from travel. Then the waters bare me

To the land of the Finns, the flood with the current,

I have never heard of your doing any such bold deeds.

The weltering waves. Not a word hath been told me

Of deeds so daring done by thee, Unferth,

And of sword-terror none; never hath Breca

At the play of the battle, nor either of you two,

Feat so fearless performèd with weapons

Glinting and gleaming .

I utter no boasting;

You are a slayer of brothers, and will suffer damnation, wise as you may be.

Though with cold-blooded cruelty thou killedst thy brothers,

Thy nearest of kin; thou needs must in hell get

Direful damnation, though doughty thy wisdom.

I tell thee in earnest, offspring of Ecglaf,

Never had Grendel such numberless horrors,

The direful demon, done to thy liegelord,

Harrying in Heorot, if thy heart were as sturdy,

Had your acts been as brave as your words, Grendel had not ravaged your land so long.

Thy mood as ferocious as thou dost describe them.

He hath found out fully that the fierce-burning hatred,

The edge-battle eager, of all of your kindred,

Of the Victory-Scyldings, need little dismay him:

The monster is not afraid of the Danes,

Of the folk of the Danemen, but fighteth with pleasure,

Killeth and feasteth, no contest expecteth

but he will soon learn to dread the Geats.

From Spear-Danish people. But the prowess and valor

Of the earls of the Geatmen early shall venture

To give him a grapple. He shall go who is able

Bravely to banquet, when the bright-light of morning

On the second day, any warrior may go unmolested to the mead-banquet.

Which the second day bringeth, the sun in its ether-robes,

O’er children of men shines from the southward!”

Then the gray-haired, war-famed giver of treasure

Hrothgar’s spirits are revived.

Was blithesome and joyous, the Bright-Danish ruler

Expected assistance; the people’s protector

The old king trusts Beowulf. The heroes are joyful.

Heard from Beowulf his bold resolution.

There was laughter of heroes; loud was the clatter,

The words were winsome. Wealhtheow advanced then,

Queen Wealhtheow plays the hostess.

Consort of Hrothgar, of courtesy mindful,

Gold-decked saluted the men in the building,

And the freeborn woman the beaker presented

She offers the cup to her husband first.

To the lord of the kingdom, first of the East-Danes,

Bade him be blithesome when beer was a-flowing,

Lief to his liegemen; he lustily tasted

Of banquet and beaker, battle-famed ruler.

The Helmingish lady then graciously circled

’Mid all the liegemen lesser and greater:

Treasure-cups tendered, till time was afforded

That the decorous-mooded, diademed folk-queen

Then she offers the cup to Beowulf, thanking God that aid has come.

Might bear to Beowulf the bumper o’errunning;

She greeted the Geat-prince, God she did thank,

Most wise in her words, that her wish was accomplished,

That in any of earlmen she ever should look for

Solace in sorrow. He accepted the beaker,

Battle-bold warrior, at Wealhtheow’s giving,

Beowulf states to the queen the object of his visit.

Then equipped for combat quoth he in measures,

Beowulf spake, offspring of Ecgtheow:

I determined to do or die.

When I boarded my boat with a band of my liegemen,

I would work to the fullest the will of your people

Or in foe’s-clutches fastened fall in the battle.

Deeds I shall do of daring and prowess,

Or the last of my life-days live in this mead-hall.”

These words to the lady were welcome and pleasing,

The boast of the Geatman; with gold trappings broidered

Went the freeborn folk-queen her fond-lord to sit by.

Then again as of yore was heard in the building

Courtly discussion, conquerors’ shouting,

Heroes were happy, till Healfdene’s son would

Go to his slumber to seek for refreshing;

For the horrid hell-monster in the hall-building knew he

A fight was determined, since the light of the sun they

No longer could see, and lowering darkness

O’er all had descended, and dark under heaven

Shadowy shapes came shying around them.

Hrothgar retires, leaving Beowulf in charge of the hall.

The liegemen all rose then. One saluted the other,

Hrothgar Beowulf, in rhythmical measures,

Wishing him well, and, the wassail-hall giving

To his care and keeping, quoth he departing:

But thee and thee only, the hall of the Danemen,

Since high I could heave my hand and my buckler.

Take thou in charge now the noblest of houses;

Be mindful of honor, exhibiting prowess,

Watch ’gainst the foeman! Thou shalt want no enjoyments,

Survive thou safely adventure so glorious!”

XI. ALL SLEEP SAVE ONE.

Hrothgar retires

Folk-lord of Scyldings, forth from the building;

The war-chieftain wished then Wealhtheow to look for,

The queen for a bedmate. To keep away Grendel

God has provided a watch for the hall.

The Glory of Kings had given a hall-watch,

As men heard recounted: for the king of the Danemen

He did special service, gave the giant a watcher:

His warlike strength and the Wielder’s protection.

His armor of iron off him he did then,

His helmet from his head, to his henchman committed

His chased-handled chain-sword, choicest of weapons,

And bade him bide with his battle-equipments.

The good one then uttered words of defiance,

Beowulf Geatman, ere his bed he upmounted:

“I hold me no meaner in matters of prowess,

In warlike achievements, than Grendel does himself;

Hence I seek not with sword-edge to sooth him to slumber,

Of life to bereave him, though well I am able.

We will fight with nature’s weapons only.

No battle-skill has he, that blows he should strike me,

To shatter my shield, though sure he is mighty

In strife and destruction; but struggling by night we

Shall do without edges, dare he to look for

Weaponless warfare, and wise-mooded Father

The glory apportion, God ever-holy,

God may decide who shall conquer

On which hand soever to him seemeth proper.”

Then the brave-mooded hero bent to his slumber,

The pillow received the cheek of the noble;

The Geatish warriors lie down.

And many a martial mere-thane attending

Sank to his slumber. Seemed it unlikely

They thought it very unlikely that they should ever see their homes again.

That ever thereafter any should hope to

Be happy at home, hero-friends visit

Or the lordly troop-castle where he lived from his childhood;

They had heard how slaughter had snatched from the wine-hall,

Had recently ravished, of the race of the Scyldings

But God raised up a deliverer.

Too many by far. But the Lord to them granted

The weaving of war-speed, to Wederish heroes

Aid and comfort, that every opponent

By one man’s war-might they worsted and vanquished,

God rules the world.

By the might of himself; the truth is established

That God Almighty hath governed for ages

Kindreds and nations. A night very lurid

Grendel comes to Heorot.

The trav’ler-at-twilight came tramping and striding.

The warriors were sleeping who should watch the horned-building,

One only excepted. ’Mid earthmen ’twas ’stablished,

Th’ implacable foeman was powerless to hurl them

To the land of shadows, if the Lord were unwilling;

But serving as warder, in terror to foemen,

He angrily bided the issue of battle.

XII. GRENDEL AND BEOWULF.

Grendel comes from the fens

Grendel going, God’s anger bare he.

The monster intended some one of earthmen

In the hall-building grand to entrap and make way with:

He went under welkin where well he knew of

The wine-joyous building, brilliant with plating,

Gold-hall of earthmen. Not the earliest occasion

This was not his first visit there.

He the home and manor of Hrothgar had sought:

Hardier hero, hall-thanes more sturdy!

Then came to the building the warrior marching,

His horrid fingers tear the door open.

Bereft of his joyance. The door quickly opened

On fire-hinges fastened, when his fingers had touched it;

The fell one had flung then—his fury so bitter—

Open the entrance. Early thereafter

The foeman trod the shining hall-pavement,

He strides furiously into the hall.

Strode he angrily; from the eyes of him glimmered

A lustre unlovely likest to fire.

He beheld in the hall the heroes in numbers,

A circle of kinsmen sleeping together,

He exults over his supposed prey.

A throng of thanemen: then his thoughts were exultant,

He minded to sunder from each of the thanemen

The life from his body, horrible demon,

Ere morning came, since fate had allowed him

Fate has decreed that he shall devour no more heroes. Beowulf suffers from suspense.

The prospect of plenty. Providence willed not

To permit him any more of men under heaven

To eat in the night-time. Higelac’s kinsman

Great sorrow endured how the dire-mooded creature

In unlooked-for assaults were likely to bear him.

No thought had the monster of deferring the matter,

Grendel immediately seizes a sleeping warrior, and devours him.

But on earliest occasion he quickly laid hold of

A soldier asleep, suddenly tore him,

Bit his bone-prison, the blood drank in currents,

Swallowed in mouthfuls: he soon had the dead man’s

Feet and hands, too, eaten entirely.

Nearer he strode then, the stout-hearted warrior

Beowulf and Grendel grapple.

Snatched as he slumbered, seizing with hand-grip,

Forward the foeman foined with his hand;

Caught he quickly the cunning deviser,

On his elbow he rested. This early discovered

The master of malice, that in middle-earth’s regions,

’Neath the whole of the heavens, no hand-grapple greater

The monster is amazed at Beowulf’s strength.

In any man else had he ever encountered:

Not off could betake him; death he was pondering,

Would fly to his covert, seek the devils’ assembly:

Long in his lifetime. The liege-kinsman worthy

Beowulf recalls his boast of the evening, and determines to fulfil it.

Of Higelac minded his speech of the evening,

Stood he up straight and stoutly did seize him.

His fingers crackled; the giant was outward,

The earl stepped farther. The famous one minded

To flee away farther, if he found an occasion,

And off and away, avoiding delay,

To fly to the fen-moors; he fully was ware of

The strength of his grapple in the grip of the foeman.

’Twas a luckless day for Grendel.

’Twas an ill-taken journey that the injury-bringing,

Harrying harmer to Heorot wandered:

Dwellers in castles, to each of the bold ones,

Earlmen, was terror. Angry they both were,

Archwarders raging. Rattled the building;

’Twas a marvellous wonder that the wine-hall withstood then

The bold-in-battle, bent not to earthward,

Excellent earth-hall; but within and without it

Was fastened so firmly in fetters of iron,

By the art of the armorer. Off from the sill there

Bent mead-benches many, as men have informed me,

Adorned with gold-work, where the grim ones did struggle.

The Scylding wise men weened ne’er before

That by might and main-strength a man under heaven

Might break it in pieces, bone-decked, resplendent,

Crush it by cunning, unless clutch of the fire

In smoke should consume it. The sound mounted upward

Grendel’s cries terrify the Danes.

Novel enough; on the North Danes fastened

A terror of anguish, on all of the men there

Who heard from the wall the weeping and plaining,

The song of defeat from the foeman of heaven,

Heard him hymns of horror howl, and his sorrow

Hell-bound bewailing. He held him too firmly

Who was strongest of main-strength of men of that era.

XIII. GRENDEL IS VANQUISHED.

Beowulf has no idea of letting Grendel live

Leave in life-joys the loathsome newcomer,

He deemed his existence utterly useless

To men under heaven. Many a noble

Of Beowulf brandished his battle-sword old,

Would guard the life of his lord and protector,

The far-famous chieftain, if able to do so;

While waging the warfare, this wist they but little,

Brave battle-thanes, while his body intending

No weapon would harm Grendel; he bore a charmed life.

To slit into slivers, and seeking his spirit:

Of all on the earth, nor any of war-bills

Was willing to injure; but weapons of victory

Swords and suchlike he had sworn to dispense with.

His death at that time must prove to be wretched,

And the far-away spirit widely should journey

Into enemies’ power. This plainly he saw then

Who with mirth of mood malice no little

Had wrought in the past on the race of the earthmen

(To God he was hostile), that his body would fail him,

But Higelac’s hardy henchman and kinsman

Held him by the hand; hateful to other

Grendel is sorely wounded.

Was each one if living. A body-wound suffered

The direful demon, damage incurable

Was seen on his shoulder, his sinews were shivered,

His body did burst. To Beowulf was given

Glory in battle; Grendel from thenceward

Must flee and hide him in the fen-cliffs and marshes,

Sick unto death, his dwelling must look for

Unwinsome and woeful; he wist the more fully

The monster flees away to hide in the moors.

The end of his earthly existence was nearing,

His life-days’ limits. At last for the Danemen,

When the slaughter was over, their wish was accomplished.

The comer-from-far-land had cleansed then of evil,

Wise and valiant, the war-hall of Hrothgar,

Saved it from violence. He joyed in the night-work,

In repute for prowess; the prince of the Geatmen

For the East-Danish people his boast had accomplished,

Bettered their burdensome bale-sorrows fully,

The craft-begot evil they erstwhile had suffered

And were forced to endure from crushing oppression,

Their manifold misery. ’Twas a manifest token,

Beowulf suspends Grendel’s hand and arm in Heorot.

When the hero-in-battle the hand suspended,

The arm and the shoulder (there was all of the claw

Of Grendel together) ’neath great-stretching hall-roof.

XIV. REJOICING OF THE DANES.

At early dawn, warriors from far and near come together to hear of the night’s adventures

Stood round the gift-hall, as the story is told me:

Through long-stretching journeys to look at the wonder,

The footprints of the foeman. Few of the warriors

Few warriors lamented Grendel’s destruction.

Who gazed on the foot-tracks of the inglorious creature

His parting from life pained very deeply,

How, weary in spirit, off from those regions

In combats conquered he carried his traces,

Fated and flying, to the flood of the nickers.

Grendel’s blood dyes the waters.

There in bloody billows bubbled the currents,

The angry eddy was everywhere mingled

And seething with gore, welling with sword-blood;

He death-doomed had hid him, when reaved of his joyance

He laid down his life in the lair he had fled to,

His heathenish spirit, where hell did receive him.

Thence the friends from of old backward turned them,

And many a younker from merry adventure,

Striding their stallions, stout from the seaward,

Heroes on horses. There were heard very often

Beowulf is the hero of the hour.

Beowulf’s praises; many often asserted

That neither south nor north, in the circuit of waters,

He is regarded as a probable successor to Hrothgar.

O’er outstretching earth-plain, none other was better

’Mid bearers of war-shields, more worthy to govern,

’Neath the arch of the ether. Not any, however,

’Gainst the friend-lord muttered, mocking-words uttered

But no word is uttered to derogate from the old king

Of Hrothgar the gracious (a good king he).

Oft the famed ones permitted their fallow-skinned horses

To run in rivalry, racing and chasing,

Where the fieldways appeared to them fair and inviting,

Known for their excellence; oft a thane of the folk-lord,

The gleeman sings the deeds of heroes.

A man of celebrity, mindful of rhythms,

Who ancient traditions treasured in memory,

New word-groups found properly bound:

He sings in alliterative measures of Beowulf’s prowess.

Wisely to tell of, and words that were clever

To utter skilfully, earnestly speaking,

Everything told he that he heard as to Sigmund’s

Also of Sigemund, who has slain a great fire-dragon.

Mighty achievements, many things hidden,

The strife of the Waelsing, the wide-going ventures

The children of men knew of but little,

The feud and the fury, but Fitela with him,

When suchlike matters he minded to speak of,

Uncle to nephew, as in every contention

Each to other was ever devoted:

They had slain with the sword-edge. To Sigmund accrued then

No little of glory, when his life-days were over,

Since he sturdy in struggle had destroyed the great dragon,

The hoard-treasure’s keeper; ’neath the hoar-grayish stone he,

The son of the atheling, unaided adventured

The perilous project; not present was Fitela,

Yet the fortune befell him of forcing his weapon

Through the marvellous dragon, that it stood in the wall,

Well-honored weapon; the worm was slaughtered.

The great one had gained then by his glorious achievement

To reap from the ring-hoard richest enjoyment,

As best it did please him: his vessel he loaded,

Shining ornaments on the ship’s bosom carried,

Kinsman of Waels: the drake in heat melted.

He was farthest famed of fugitive pilgrims,

Mid wide-scattered world-folk, for works of great prowess,

War-troopers’ shelter: hence waxed he in honor.

Heremod, an unfortunate Danish king, is introduced by way of contrast.

Afterward Heremod’s hero-strength failed him,

His vigor and valor. ’Mid venomous haters

To the hands of foemen he was foully delivered,

Offdriven early. Agony-billows

Unlike Sigemund and Beowulf, Heremod was a burden to his people.

Oppressed him too long, to his people he became then,

To all the athelings, an ever-great burden;

And the daring one’s journey in days of yore

Many wise men were wont to deplore,

Such as hoped he would bring them help in their sorrow,

That the son of their ruler should rise into power,

Holding the headship held by his fathers,

Should govern the people, the gold-hoard and borough,

The kingdom of heroes, the realm of the Scyldings.

Beowulf is an honor to his race.

He to all men became then far more beloved,

Higelac’s kinsman, to kindreds and races,

To his friends much dearer; him malice assaulted.—

Oft running and racing on roadsters they measured

The dun-colored highways. Then the light of the morning

Was hurried and hastened. Went henchmen in numbers

To the beautiful building, bold ones in spirit,

To look at the wonder; the liegelord himself then

From his wife-bower wending, warden of treasures,

Glorious trod with troopers unnumbered,

Famed for his virtues, and with him the queen-wife

Measured the mead-ways, with maidens attending.

XV. HROTHGAR’S GRATITUDE.

He stood by the pillar, saw the steep-rising hall-roof

Gleaming with gold-gems, and Grendel his hand there):

“For the sight we behold now, thanks to the Wielder

Early be offered! Much evil I bided,

Snaring from Grendel: God can e’er ’complish

Wonder on wonder, Wielder of Glory!

I had given up all hope, when this brave liegeman came to our aid.

But lately I reckoned ne’er under heaven

Comfort to gain me for any of sorrows,

While the handsomest of houses horrid with bloodstain

Gory uptowered; grief had off frightened

Each of the wise ones who weened not that ever

The folk-troop’s defences ’gainst foes they should strengthen,

’Gainst sprites and monsters. Through the might of the Wielder

A doughty retainer hath a deed now accomplished

Which erstwhile we all with our excellent wisdom

If his mother yet liveth, well may she thank God for this son.

Failed to perform. May affirm very truly

What woman soever in all of the nations

Gave birth to the child, if yet she surviveth,

That the long-ruling Lord was lavish to herward

In the birth of the bairn. Now, Beowulf dear,

Hereafter, Beowulf, thou shalt be my son.

Most excellent hero, I’ll love thee in spirit

As bairn of my body; bear well henceforward

The relationship new. No lack shall befall thee

Of earth-joys any I ever can give thee.

Full often for lesser service I’ve given

Hero less hardy hoard-treasure precious,

Thou hast won immortal distinction.

To a weaker in war-strife. By works of distinction

Thou hast gained for thyself now that thy glory shall flourish

Forever and ever. The All-Ruler quite thee

With good from His hand as He hitherto did thee!”

Beowulf replies: I was most happy to render thee this service.

Beowulf answered, Ecgtheow’s offspring:

The combat accomplished, unquailing we ventured

The enemy’s grapple; I would grant it much rather

Thou wert able to look at the creature in person,

Faint unto falling, the foe in his trappings!

On murder-bed quickly I minded to bind him,

With firm-holding fetters, that forced by my grapple

Low he should lie in life-and-death struggle

’Less his body escape; I was wholly unable,

I could not keep the monster from escaping, as God did not will that I should.

Since God did not will it, to keep him from going,

Not held him that firmly, hated opposer;

Too swift was the foeman. Yet safety regarding

He suffered his hand behind him to linger,

His arm and shoulder, to act as watcher;

He left his hand and arm behind.

No shadow of solace the woe-begone creature

Found him there nathless: the hated destroyer

Liveth no longer, lashed for his evils,

But sorrow hath seized him, in snare-meshes hath him

Close in its clutches, keepeth him writhing

In baleful bonds: there banished for evil

The man shall wait for the mighty tribunal,

God will give him his deserts.

How the God of glory shall give him his earnings.”

Then the soldier kept silent, son of old Ecglaf,

Unferth has nothing more to say, for Beowulf’s actions speak louder than words.

From boasting and bragging of battle-achievements,

Since the princes beheld there the hand that depended

’Neath the lofty hall-timbers by the might of the nobleman,

Each one before him, the enemy’s fingers;

Each finger-nail strong steel most resembled,

The heathen one’s hand-spur, the hero-in-battle’s

Claw most uncanny; quoth they agreeing,

No sword will harm the monster.

That not any excellent edges of brave ones

Was willing to touch him, the terrible creature’s

Battle-hand bloody to bear away from him.

XVI. HROTHGAR LAVISHES GIFTS UPON HIS DELIVERER.

Heorot is adorned with hands

With hands be embellished: a host of them gathered,

Of men and women, who the wassailing-building

The guest-hall begeared. Gold-flashing sparkled

Webs on the walls then, of wonders a many

To each of the heroes that look on such objects.

The hall is defaced, however.

The beautiful building was broken to pieces

Which all within with irons was fastened,

Its hinges torn off: only the roof was

Whole and uninjured when the horrible creature

Outlawed for evil off had betaken him,

Hopeless of living. ’Tis hard to avoid it

(Whoever will do it!); but he doubtless must come to

The place awaiting, as Wyrd hath appointed,

Soul-bearers, earth-dwellers, earls under heaven,

Where bound on its bed his body shall slumber

Hrothgar goes to the banquet.

When feasting is finished. Full was the time then

That the son of Healfdene went to the building;

The excellent atheling would eat of the banquet.

Ne’er heard I that people with hero-band larger

Bare them better tow’rds their bracelet-bestower.

The laden-with-glory stooped to the bench then

(Their kinsmen-companions in plenty were joyful,

Many a cupful quaffing complaisantly),

Doughty of spirit in the high-tow’ring palace,

Hrothgar’s nephew, Hrothulf, is present.

Hrothgar and Hrothulf. Heorot then inside

Was filled with friendly ones; falsehood and treachery

The Folk-Scyldings now nowise did practise.

Hrothgar lavishes gifts upon Beowulf.

Then the offspring of Healfdene offered to Beowulf

A golden standard, as reward for the victory,

A banner embossed, burnie and helmet;

Many men saw then a song-famous weapon

Borne ’fore the hero. Beowulf drank of

The cup in the building; that treasure-bestowing

He needed not blush for in battle-men’s presence.

Four handsomer gifts were never presented.

Ne’er heard I that many men on the ale-bench

In friendlier fashion to their fellows presented

Four bright jewels with gold-work embellished.

’Round the roof of the helmet a head-guarder outside

Braided with wires, with bosses was furnished,

That swords-for-the-battle fight-hardened might fail

Boldly to harm him, when the hero proceeded

Hrothgar commands that eight finely caparisoned steeds be brought to Beowulf.

Forth against foemen. The defender of earls then

Commanded that eight steeds with bridles

Gold-plated, gleaming, be guided to hallward,

Inside the building; on one of them stood then

An art-broidered saddle embellished with jewels;

’Twas the sovereign’s seat, when the son of King Healfdene

Was pleased to take part in the play of the edges;

The famous one’s valor ne’er failed at the front when

Slain ones were bowing. And to Beowulf granted

The prince of the Ingwins, power over both,

O’er war-steeds and weapons; bade him well to enjoy them.

In so manly a manner the mighty-famed chieftain,

Hoard-ward of heroes, with horses and jewels

War-storms requited, that none e’er condemneth

Who willeth to tell truth with full justice.

XVII. BANQUET (continued).—THE SCOP’S SONG OF FINN AND HNAEF.

Each of Beowulf’s companions receives a costly gift

Who the ways of the waters went with Beowulf,

A costly gift-token gave on the mead-bench,

Offered an heirloom, and ordered that that man

The warrior killed by Grendel is to be paid for in gold.

With gold should be paid for, whom Grendel had erstwhile

Wickedly slaughtered, as he more of them had done

Had far-seeing God and the mood of the hero

The fate not averted: the Father then governed

All of the earth-dwellers, as He ever is doing;

Hence insight for all men is everywhere fittest,

Forethought of spirit! much he shall suffer

Of lief and of loathsome who long in this present

Useth the world in this woful existence.

There was music and merriment mingling together

Hrothgar’s scop recalls events in the reign of his lord’s father.

Touching Healfdene’s leader; the joy-wood was fingered,

Measures recited, when the singer of Hrothgar

On mead-bench should mention the merry hall-joyance

Of the kinsmen of Finn, when onset surprised them:

“The Half-Danish hero, Hnaef of the Scyldings,

On the field of the Frisians was fated to perish.

Sure Hildeburg needed not mention approving

The faith of the Jutemen: though blameless entirely,

Queen Hildeburg is not only wife of Finn, but a kinswoman of the murdered Hnaef.

When shields were shivered she was shorn of her darlings,

Of bairns and brothers: they bent to their fate

With war-spear wounded; woe was that woman.

Not causeless lamented the daughter of Hoce

The decree of the Wielder when morning-light came and

She was able ’neath heaven to behold the destruction

Of brothers and bairns, where the brightest of earth-joys

Finn’s force is almost exterminated.

She had hitherto had: all the henchmen of Finn

War had off taken, save a handful remaining,

That he nowise was able to offer resistance

Hengest succeeds Hnaef as Danish general.

To the onset of Hengest in the parley of battle,

Nor the wretched remnant to rescue in war from

The earl of the atheling; but they offered conditions,

Compact between the Frisians and the Danes.

Another great building to fully make ready,

A hall and a high-seat, that half they might rule with

The sons of the Jutemen, and that Folcwalda’s son would

Day after day the Danemen honor

When gifts were giving, and grant of his ring-store

To Hengest’s earl-troop ever so freely,

Of his gold-plated jewels, as he encouraged the Frisians

On the bench of the beer-hall. On both sides they swore then

A fast-binding compact; Finn unto Hengest

With no thought of revoking vowed then most solemnly

The woe-begone remnant well to take charge of,

His Witan advising; the agreement should no one

By words or works weaken and shatter,

By artifice ever injure its value,

Though reaved of their ruler their ring-giver’s slayer

They followed as vassals, Fate so requiring:

Then if one of the Frisians the quarrel should speak of

In tones that were taunting, terrible edges

Should cut in requital. Accomplished the oath was,

And treasure of gold from the hoard was uplifted.

Danish warriors are burned on a funeral-pyre.

The best of the Scylding braves was then fully

Prepared for the pile; at the pyre was seen clearly

The blood-gory burnie, the boar with his gilding,

The iron-hard swine, athelings many

Fatally wounded; no few had been slaughtered.

Hildeburg bade then, at the burning of Hnaef,

Queen Hildeburg has her son burnt along with Hnaef.

The bairn of her bosom to bear to the fire,

That his body be burned and borne to the pyre.

The woe-stricken woman wept on his shoulder,

In measures lamented; upmounted the hero.

The greatest of dead-fires curled to the welkin,

On the hill’s-front crackled; heads were a-melting,

Wound-doors bursting, while the blood was a-coursing

From body-bite fierce. The fire devoured them,

Greediest of spirits, whom war had off carried

From both of the peoples; their bravest were fallen.

XVIII. THE FINN EPISODE (continued).—THE BANQUET CONTINUES.

The survivors go to Friesland, the home of Finn

Reaved of their friends, Friesland to visit,

Their homes and high-city. Hengest continued

Hengest remains there all winter, unable to get away.

Biding with Finn the blood-tainted winter,

Wholly unsundered; of fatherland thought he

Though unable to drive the ring-stemmèd vessel

O’er the ways of the waters; the wave-deeps were tossing,

Fought with the wind; winter in ice-bonds

Closed up the currents, till there came to the dwelling

A year in its course, as yet it revolveth,

If season propitious one alway regardeth,

World-cheering weathers. Then winter was gone,

Earth’s bosom was lovely; the exile would get him,

He devises schemes of vengeance.

The guest from the palace; on grewsomest vengeance

He brooded more eager than on oversea journeys,

Whe’r onset-of-anger he were able to ’complish,

The bairns of the Jutemen therein to remember.

Nowise refused he the duties of liegeman

When Hun of the Frisians the battle-sword Láfing,

Fairest of falchions, friendly did give him:

And savage sword-fury seized in its clutches

Bold-mooded Finn where he bode in his palace,

Guthlaf and Oslaf revenge Hnaef’s slaughter.

When the grewsome grapple Guthlaf and Oslaf

Had mournfully mentioned, the mere-journey over,

For sorrows half-blamed him; the flickering spirit

Could not bide in his bosom. Then the building was covered

With corpses of foemen, and Finn too was slaughtered,

The king with his comrades, and the queen made a prisoner.

The jewels of Finn, and his queen are carried away by the Danes.

The troops of the Scyldings bore to their vessels

All that the land-king had in his palace,

Such trinkets and treasures they took as, on searching,

At Finn’s they could find. They ferried to Daneland

The excellent woman on oversea journey,

The lay is concluded, and the main story is resumed.

Led her to their land-folk.” The lay was concluded,

The gleeman’s recital. Shouts again rose then,

Bench-glee resounded, bearers then offered

Skinkers carry round the beaker.

Wine from wonder-vats. Wealhtheo advanced then

Going ’neath gold-crown, where the good ones were seated

Queen Wealhtheow greets Hrothgar, as he sits beside Hrothulf, his nephew.

Uncle and nephew; their peace was yet mutual,

True each to the other. And Unferth the spokesman

Sat at the feet of the lord of the Scyldings:

Though at fight he had failed in faith to his kinsmen.

Said the queen of the Scyldings: “My lord and protector,

Treasure-bestower, take thou this beaker;

Joyance attend thee, gold-friend of heroes,

Be generous to the Geats.

And greet thou the Geatmen with gracious responses!

So ought one to do. Be kind to the Geatmen,

In gifts not niggardly; anear and afar now

Peace thou enjoyest. Report hath informed me

Thou’lt have for a bairn the battle-brave hero.

Now is Heorot cleansèd, ring-palace gleaming;

Have as much joy as possible in thy hall, once more purified.

Give while thou mayest many rewards,

And bequeath to thy kinsmen kingdom and people,

On wending thy way to the Wielder’s splendor.

I know good Hrothulf, that the noble young troopers

I know that Hrothulf will prove faithful if he survive thee.

He’ll care for and honor, lord of the Scyldings,

If earth-joys thou endest earlier than he doth;

I reckon that recompense he’ll render with kindness

Our offspring and issue, if that all he remember,

What favors of yore, when he yet was an infant,

We awarded to him for his worship and pleasure.”

Then she turned by the bench where her sons were carousing,

Hrethric and Hrothmund, and the heroes’ offspring,

Beowulf is sitting by the two royal sons.

The war-youth together; there the good one was sitting

’Twixt the brothers twain, Beowulf Geatman.

XIX. BEOWULF RECEIVES FURTHER HONOR.

More gifts are offered to Beowulf

Graciously given, and gold that was twisted

Pleasantly proffered, a pair of arm-jewels,

Rings and corslet, of collars the greatest

I’ve heard of ’neath heaven. Of heroes not any

More splendid from jewels have I heard ’neath the welkin,

A famous necklace is referred to, in comparison with the gems presented to Beowulf.

Since Hama off bore the Brosingmen’s necklace,

The bracteates and jewels, from the bright-shining city,

Eormenric’s cunning craftiness fled from,

Chose gain everlasting. Geatish Higelac,

Grandson of Swerting, last had this jewel

When tramping ’neath banner the treasure he guarded,

The field-spoil defended; Fate offcarried him

When for deeds of daring he endured tribulation,

Hate from the Frisians; the ornaments bare he

O’er the cup of the currents, costly gem-treasures,

Mighty folk-leader, he fell ’neath his target;

The corpse of the king then came into charge of

The race of the Frankmen, the mail-shirt and collar:

When the fight was finished; the folk of the Geatmen

The field of the dead held in possession.

The choicest of mead-halls with cheering resounded.

Wealhtheo discoursed, the war-troop addressed she:

“This collar enjoy thou, Beowulf worthy,

Young man, in safety, and use thou this armor,

Gems of the people, and prosper thou fully,

Show thyself sturdy and be to these liegemen

Mild with instruction! I’ll mind thy requital.

Thou hast brought it to pass that far and near

Forever and ever earthmen shall honor thee,

Even so widely as ocean surroundeth

The blustering bluffs. Be, while thou livest,

A wealth-blessèd atheling. I wish thee most truly

May gifts never fail thee.

Jewels and treasure. Be kind to my son, thou

Living in joyance! Here each of the nobles

Is true unto other, gentle in spirit,

Loyal to leader. The liegemen are peaceful,

The war-troops ready: well-drunken heroes,

Do as I bid ye.” Then she went to the settle.