Samuel P. Nelson and Catherine Prendergast

Murderabilia Inc.: Where the First Amendment Fails Academic Freedom

In August 2006, a federal judge ordered a government foray into the “murderabilia” business. On offer: the property of Theodore John Kaczynski, a.k.a. the Unabomber, seized during the 1996 raid on Kaczynski’s Montana cabin, including his tweezers, empty peanut butter jar, and his papers—forty thousand pages’ worth. The proceeds of the Internet auction would go to Kaczynski’s victims, to whom he owes $15 million in restitution.

This is a sale no one seemed to want—not Kaczynski, who had intended to donate his papers to the University of Michigan Special Collections Library; not librarians and archivists, who argued that these papers were of historic value and should be preserved; and not many of the victims, whose pain was to be made a macabre spectacle. But neither can the U.S. government, which could have avoided the sale had it given Kaczynski his property when he filed a motion for its return in 2003, be considered a winning party in the decision ordering the sale. Troubled by Kaczynski’s plan to add his writings to a collection of social protest and anarchist literature, the government had succeeded in opposing his motion in court, winning at the district court and appellate court levels. The Unabomber, the government had argued, had gained notoriety as a terrorist of letters, and therefore, the archiving of his papers at the University of Michigan would only increase his renown. The U.S. government proposed instead to establish a “prenotoriety” (i.e., negligible) value for Kaczynski’s items through a private “garage sale,” deposit an equivalent amount of taxpayer money in a fund for victims—and keep the stuff. In 2005, however, a panel of judges on the Ninth Circuit Court of Appeals found this plan untenable and determined that the government must either return Kaczynski’s property to him or dispose of it through a public sale. As of fall 2008, the auction is still tied up in court as Kaczynski, currently representing himself, continues to fight it on First Amendment grounds.

We raise the controversy over the auction of Kaczynski’s papers because we believe that investigating both Kaczynski’s efforts to regain possession of his writings so he can send them to a university archive and the government’s motives in blocking him teaches us about forms of academic freedom little considered in debates on the matter. On the one hand, Kaczynski would seem an odd figure through which to look for lessons regarding academic freedom. He is an incarcerated terrorist, mentally ill, and although he was a professor of mathematics at the University of California at Berkeley for a short time in the 1960s, he spent most of his adult life deeply suspicious of academia. The un in the Unabomber moniker the FBI gave him in fact stands for universities, which, besides airports (the a), were Kaczynski’s favorite targets. He was furthermore no fan of academic freedom and regarded the universities as dominated by leftists, whom he despised. David Horowitz’s crabbed take on academic freedom could have been lifted right from this passage from the Unabomber Manifesto: “In the United States, a couple of decades ago when leftists were a minority in our universities, leftist professors were vigorous proponents of academic freedom, but today, in those universities where leftists have become dominant, they have shown themselves ready to take away from everyone else’s academic freedom. (This is ‘political correctness.’)”[1]

We do not offer here a defense of Kaczynski, either his actions or beliefs. We instead look to his case as an instance to investigate the broader principles underlying academic freedom, including First Amendment claims. First Amendment principles have traditionally been established in cases involving those who exceed the bounds of social acceptability—historically, communists, Nazis, pornographers, flag burners, and peace activists.[2] In the United States, we protect unpopular and disfavored speakers such as anarchists, criminals, or vulgar comedians less out of respect for their individual rights (constitutional or human) than for the contribution of their perspectives and arguments to a social process of truth finding. The identity of the particular speaker is, in many ways, irrelevant to a justification of freedom of speech that protects alike the distinguished university professor with a slew of books and the perceived nuisance ranting on a street corner, based on the possibility that either one’s ideas may ultimately be true or otherwise contribute to the social process of truth discovery.[3] The court battle over a high-profile convict’s papers asks us to reconsider whose interests academic freedom is meant to promote and who must be covered under its umbrella in order to secure the benefits promised in conventional defenses of academic freedom.

The controversy over Kaczynski’s papers can also provide an interesting contrast to typical academic freedom cases concerned with institutional practices: granting tenure, retaining employment, making admissions decisions—none of these concerns that generally feature prominently in the current debates over academic freedom have any bearing on the circumstances of an incarcerated ex-professor or the public interest in his writing. Furthermore, the U.S. government is a party in the case; few if any academic freedom cases decided by the U.S. Supreme Court deal with direct acts of censorship by the government rather than through intermediary institutions such as college or university administrations. The key cases on academic freedom all deal primarily with protection for colleges and universities as institutions, affirming their right to make decisions in governance and admissions, so long as those decisions are not seen to abridge any individual’s constitutional rights. While academic freedom is commonly considered to be a kind of super free speech for individual faculty members, it is actually colleges and universities that hold the strongest claim on academic freedom rights in First and Fourteenth Amendment law.[4] Individual faculty members, as a matter of First Amendment law, do not appear to have substantially different speech rights than citizens more generally.[5] To the extent that individual faculty members have academic freedom as a matter of First Amendment law, it comes to them through more general protection of the autonomy of the public institution that employs them. They have, as we will discuss, a very limited First Amendment claim to protection from their institution. In practice the state must be involved in order for the First Amendment to be implicated; however, the American Association of University Professors (AAUP) and other academic professional organizations do not recognize the distinction between state institutions and private institutions.

We search here for more secure grounds on which to base academic freedom and find that those grounds must sustain a broader public than has been conceptualized by advocates of academic freedom to date. The phrase academic freedom currently encompasses distinct rights for individual faculty and for academic institutions. In our view, there is a distinct but analogous freedom of inquiry held by the public. Academic freedom for individuals and institutions will be strengthened by recognition of the public’s freedom of inquiry and by finding more clarity about the boundaries between inquiry and professional academic freedom. Not all groups will receive, or exercise, freedom of inquiry on the same grounds. Justifications of this freedom are context specific and must take into account the circumstances, social relationships, and objectives of each group. It is through investigating freedom of inquiry held by other groups, for example, that we realize that individual academic freedom for faculty is protected because of the professional norms of the professoriate in relation to the universities and colleges with which they are affiliated.[6] However, the public, broadly construed, can be said to have freedom of inquiry, which has not, as of yet, received sufficient recognition by the courts, First Amendment scholars, or the AAUP. Defenses of academic freedom continue to rely on postulating the professoriate as an elite group whose rights and responsibilities exceed those of the public, however curious, inquisitive, or even scholarly that public might be. Instead, we see academic freedom as a particular instance of a more general freedom of inquiry. The general public has a noncontroversial First Amendment right to information, inquiry, and expression. We seek to strengthen the justification of professional academic freedom by better articulating the conception of public freedom of inquiry and its relationship to conventional conceptions of academic freedom described in AAUP documents. We do so by highlighting shared or complementary elements that are widely enjoyed rights rather than special privileges for academics while at the same time emphasizing clear boundaries between institutional and individual academic freedom, on the one hand, and the freedom of inquiry retained by the public, on the other.

The broad concept of freedom of inquiry does not solve all the problems of the academic freedom of individual academic faculty members, especially insofar as faculty seek protection from the actions of their own institutions. As administrations move to urge “useful” or “profitable” knowledge and work to package courses, faculty increasingly worry that the commodification of knowledge through contracts designed to give universities ownership of intellectual property will transfer ultimate control of the knowledge products of faculty to administrators. The greater the extent to which scholarly work is organized under the terms of contract law, the less academic freedom individual scholars worry they will have.[7] Lessons drawn from the battle of Kaczynski’s papers suggest, however, that while such may be the case, more is to be gained in terms of academic freedom by rethinking the relationship of the public to it than by refining a professorial role in the corporate hierarchy.

The Marketplace of Ideas—and Whatever Else Sells

The great paradox in debates over academic freedom with regard to the public’s interests is that those interests are everywhere invoked and nowhere represented. Although the public’s interests are cited in legal cases involving individual and institutional academic freedom and in more theoretical arguments over academic freedom, the public’s direct exercise of anything closely analogous to academic freedom is rarely envisioned. Arguments to justify individual academic freedom (such as the AAUP statements of 1915 and 1940) or by institutions defending autonomy in admissions and personnel matters point to the public benefits provided by the exercise of academic freedom of universities and their faculty but do not go so far as to articulate a right, held by the public itself, to freedom of inquiry. The conventional defense of individual and institutional academic freedom is grounded in the same “marketplace of ideas” rationale commonly found in First Amendment defenses of free speech. Classic free speech arguments and the AAUP statements on individual academic freedom share the consequentialist logic that speakers should be protected as a means to produce a robust public debate that will result in the discovery of objective truth. In John Stuart Mill (1869; On Liberty), Alexander Meiklejohn (1960; Political Freedom), and the U.S. Supreme Court (New York Times v. Sullivan [1964] and Brandenburg v. Ohio [1969]), the speech of individuals is not protected because we value the speakers for themselves, or the speech in itself, but for the dynamic process of debate and discussion that ensues from the speech acts of individual speakers. We value public debate only insofar as it is a means to discover objective truths about the world or about what the best public policy should be.

Given that this consequentialist logic of the search for truth supports both AAUP and key First Amendment cases, it is understandable that many assume individual academic freedom is based in the First Amendment. The 1915 AAUP “Declaration of Principles” is grounded in the traditional liberal account of freedom of speech, extending it to recognize the benefit to the public of the academic search for truth through rigorous, open, and unconstrained debate among scholars. Similarly, in key cases defending free speech and in pronouncements over academic freedom, a shared consequentialist logic blurs the distinction between the two rights. However, a closer look at case law specifically addressing academic freedom reveals ample protection for institutional academic freedom but little support for individual faculty. A series of Supreme Court cases—Sweezy v. New Hampshire (1957), Keyishian v. Board of Regents (1967), Regents of the University of California v. Bakke (1978), University of Pennsylvania v. EEOC (1990), culminating in Grutter v. Bollinger (2003)—appears to protect academic freedom by defining universities as institutions that “occupy a special niche in our constitutional tradition” and to the judgment of which the Court will defer.[8] However, in practice, these cases only protect institutional academic freedom while supporting the freedom of individual faculty members in rhetoric more than substance. Sweezy and Keyishian each involve government conditions on faculty employment that scrutinize the political views or outside political activities of individual faculty members and reference the social value of academic freedom. Paul Sweezy was investigated as a potential “subversive,” and Harry Keyishian refused to sign a paper declaring that he was not a communist—an act that led to the nonrenewal of his lecturer contract by the State University of New York. The cases include stirring statements grounding academic freedom in the First Amendment, including: “Our nation is deeply committed to safeguarding academic freedom, which is of transcendent value to all of us, and not merely to the teachers concerned. That freedom is therefore a special concern of the First Amendment which does not tolerate laws that cast a pall of orthodoxy over the classroom. . . . The classroom is peculiarly the ‘marketplace of ideas.’”[9] Outside the context of now-defunct loyalty oaths, it is not clear that these cases have ever been the basis for a court decision in favor of an individual faculty member challenging an institutional decision. Without discarding the rhetoric of protection of individual faculty members, the Court shifts decidedly to an emphasis on institutional freedom. University of Pennsylvania protects the confidentiality of tenure documents under color of academic freedom, a lack of transparency that benefits the institution that denies tenure far more than it protects the faculty member engaged in legal proceedings to overturn that denial. Bakke concerns affirmative action in admissions, with the Court adopting a circumscribed deference to institutional educational judgments on the grounds that such judgments promote the public interest in well-trained doctors. Finally in Grutter, Justice Sandra Day O’Connor grounds her argument in favor of the University of Michigan Law School’s consideration of race in admissions on the special status Bakke granted to institutions of higher learning. If the “public benefits” rationale for academic freedom is large enough to cover the consideration of race in university admissions, then its umbrella protects a vast range of less controversial institutional decisions over curriculum, marketing, or the commodification of faculty labor.[10]

There is also little in First Amendment law to prevent administrations from bundling courses into marketable units because the gap between business and academic enterprises has been closing in major academic freedom decisions. Although Bakke recognized academic institutions as distinct enterprises from businesses, Justice O’Connor’s opinion in Grutter muddied the distinction by calling heavily on an amicus brief filed by a group of Fortune 500 companies, which avowed that a diversified labor force with varied viewpoints was key to America’s ability to compete in a global economy. Grutter most sharply illustrates the failing of the liberal view that imagines a marketplace of ideas as only a metaphorical marketplace, one in which ideas are freely traded independent of government suppression. Liberal free speech theorists did not expect or account for the recent evolution toward a market in ideas in the literal sense, where ideas become property objects to be bought and sold. Cases over institutional academic freedom have in sum only strengthened the university’s power to act as a business in the interest of profit making.

The underlying questions of who gets to profit from writing, what counts as profit, and the role of reputation in creating property from academic work in universities are central to understanding the evolving context of academic freedom. The academic marketplace of ideas is a complex construct of conventional monetary profit, reputation, celebrity, terms of contract, and social practices. Kaczynski’s case provides a cautionary tale in that the government has invoked a contractual arrangement to control and even co-opt Kaczynski’s notoriety (which they see as a form of profit) through the control of his papers. Through the mechanism of reputation, murderabilia takes speech materials and turns them into artifacts that are then seen as valuable physical property, importantly denying the public interest in the information those artifacts contained. The plea agreement Kaczynski entered that limits his rights in relationship to his writing is of course quite different from a contract offered by a university administration to an individual faculty member. However, Kaczynski’s case makes clear that contracts can serve to shift questions from the familiar legal framework of the First Amendment to the very different framework of property law. In the case of Kaczynski’s papers and in the case of academic labor, contracts have the potential to negate free speech claims through the legal framework of property. Although professors often forgo monetary gain from their research in exchange for the benefits of reputation, reputation affords no safeguard within the property framework. Indeed, we argue that clinging to reputation can continue to obscure from view an important ally in the fight for academic freedom—an active public with research agendas of its own.

An Active Faculty and a Passive Public

The AAUP statements on academic freedom set up a confusing and potentially problematic relationship between professors and the public that serves to reinforce rather than challenge liberal notions of academic freedom. Faculty are quick to recognize the special protections of their speech in AAUP documents but do not always acknowledge the restrictions that also are articulated in these statements. As Frank Donoghue observes, the AAUP’s 1940 “Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure” is actually broadly restrictive of faculty speech, once it identifies faculty as having a “special position” with regard to the public. The statement first accords faculty a place among the public but swiftly separates them:

College and university teachers are citizens, members of a learned profession, and officers of an educational institution. When they speak or write as citizens, they should be free from institutional censorship or discipline, but their special position in the community imposes special obligations. As scholars and educational officers, they should remember that the public may judge their profession and their institution by their utterances. Hence they should at all times be accurate, should exercise appropriate restraint, should show respect for the opinions of others, and should make every effort to indicate that they are not speaking for the institution.[11]

Donoghue notes that the restrictions articulated in the AAUP statement “come not from an employer, but from the professor’s ‘special position.’”[12] He questions whether professors do indeed hold this special position, given that they tend to write for each other rather than for the public. We would further ask if the public recognizes the special position of professors or whether the profession just asserts one. But aside from the power to judge the institution, the public has no active participation in the common good that the statement articulates as the ultimate goal of the exercise of academic freedom.

Although Donoghue’s concern is that the construction of faculty as an elite group hampers their academic freedom, we wish to point out that it also fails to promote the freedom of the public—those not affiliated with universities as professors. The 1940 “Statement” emphasizes promotion of the public interest in truth by treating university faculty as experts with special qualifications to promote the public interest in truth, but simultaneously excludes the public from debate over the outcome. The public should not be reduced to a secondary or passive position in deliberations about matters in its own interest. The 1940 “Statement” itself indirectly testifies to this principle; perhaps the passive construction of the public should not surprise us, as the public did not have a significant role in constructing the 1940 “Statement” in the first place. On the other hand, if we think of academic freedom as protection of a particular type of specialized knowledge in broader public deliberations, the relationship between public interest and professional privileges becomes clearer and less exclusive. We want to forcefully distinguish here our efforts to recognize the scope of the public’s freedom of inquiry from the rancorous and ill-conceived attempts to ascribe students as a public with distinct academic freedom opposed to that of faculty as a professional group. As articulated within the so-called Academic Bill of Rights, student academic freedom partakes of the same misconceptions of the actual protections of First Amendment law evident in the AAUP statements. Proponents of the Academic Bill of Rights, authored and distributed by the organization Students for Academic Freedom, suggest that the professoriate constitutes a corrupt cartel that should be disbanded by appeal to the First Amendment.[13] However, in seeking “balanced” truth from their professors, students remain a passive and circumscribed public, one that merely receives information from a professional group. The AAUP has responded to this attack on professional norms: “It follows that if an instructor has formed an opinion on a controversial question in adherence to scholarly standards of professional care, it is as much an exercise of academic freedom to test those opinions before students as it is to present them to the public at large.”[14] This AAUP report demonstrates that the same professional norms that define individual academic freedom for faculty also effectively protect students from indoctrination and other abuses alleged by conservative critics.

Despite its important clarification of the difference between indoctrination and education, all the problems with the liberal framework for academic freedom—overemphasis on the search for truth, the professor’s special position, and the passive public—are reinforced through the AAUP’s response to the Academic Bill of Rights, which provides an active participatory role for students in scholarly inquiry but still does not manage to articulate an active broader public. It might be rhetorically advantageous to use the threat posed by David Horowitz as an opportunity to make the case to the public for the broader benefits of academic freedom for faculty and its relationship to the general freedom of inquiry shared by all under the First Amendment. Instead, overemphasis on academic freedom as a special right of professors without discussing the complementary freedom of inquiry held by the public undermines the professoriate’s ability to effectively defend professional norms and practices. The right of public access to information is directly raised, however, in the Kaczynski case, through an amicus brief filed by the Freedom to Read Foundation and the Society of American Archivists that maintains that the public as well as scholars have a right to access the original Kaczynski papers. In arguing not only a public interest in participating in open scholarly debate, but an equal right of public access to original materials, the brief importantly differs from the consequentialist argument; it suggests through its argument a crucial analogue to academic freedom belonging not to professional academics but to an actively inquisitive public.[15]

In contrast to the model of opposing forms of academic freedoms— one professorial and one public—suggested through the Academic Bill of Rights, we would move toward a conception of mutually reinforcing, rather than mutually constraining, freedoms of inquiry. If public interests are served by professors at the University of Toledo or University of Illinois studying free speech, they are also served by public intellectuals and independent scholars who happen to live in Toledo or Urbana. Further, since universities are unlikely to serve as legal surrogates to represent public interests beyond those with a direct impact on the institution’s goals or plans, there is ample reason for the government to act to promote First Amendment objectives on behalf of the public’s freedom of inquiry interests. The U.S. government formally recognized the public’s right to active inquiry unmediated through the professoriate when in 1974 it amended the Freedom of Information Act to guarantee public as well as professorial access to government documents. We know that the public, given opportunity and access, does exercise its right to seek information. For example, at the Labadie Collection of Social Protest Material located at the University of Michigan Library—the collection to which Kaczynski wanted to donate his disputed papers and which already houses six linear feet of his papers— roughly one-third of the outside visitors are not affiliated with a college or university.[16] State-supported libraries and government archives preserve information for its potential value to researchers both affiliated with universities and not, including that information’s possible relevance to debates we cannot imagine today.

Here the controversy over Kaczynski’s papers highlights the perils of imagining a passive public. Kaczynski himself is almost entirely focused on his freedom of speech rights and rarely raises the potential public interest in his writing in his second appeal; where he does raise that interest, echoing the archivists’ brief, his construction of the public is limited to one that only receives the messages that he is trying to communicate. In letters and other documents Kaczynski acknowledges the rights of people to say what they like about him and his case, even if he doesn’t agree with it, but the public imagined through his appeal remains composed of completely passive recipients of his truth. Important, however, is a hypothetical public with active research agendas exceeding those that the owner of copyright, the archivists, and the government together can imagine. Despite Kaczynski’s hope that people will leave the archives radicalized by his message, it is just as likely that a reader might leave with impressions contrary to those Kaczynski wished to convey. To illustrate, one of the perennial “truths” Kaczynski tries to communicate is that he is not mentally ill. At the time the appeals of his criminal charges were in process, he spent much of his energy trying to publish a 500-page refutation of his family’s claims that he was mentally ill titled “Truth v. Lies,” the drafts of which are currently housed in the Labadie Collection. Also in the collection, however, are copies of letters Kaczynski wrote while living in near isolation in Montana that reveal his attempts to acquire care for persistent insomnia and stress. Such material could lead one to conclude that Kaczynski (and society) might have benefited from his receiving adequate care for his mental state earlier, even if he would maintain otherwise.

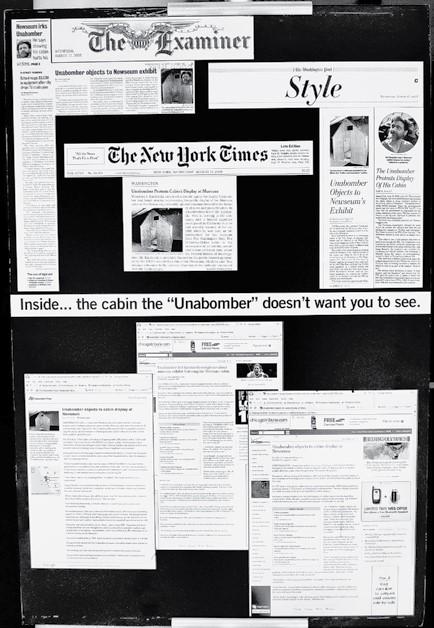

Kaczynski’s charge in his appeal that the government is trying to suppress information through redaction and withholding should nonetheless be given due consideration. The government in general and the FBI in particular have historically advanced numerous rationales to maintain secrecy of their documents. According to Athan Theoharis, the FBI—“a bureaucratic culture hostile to the principle of public access”—sought from 1946 to prevent the release of any of its records, regardless of content, by lobbying Congress, pressuring the Justice Department, and invoking by turns executive privilege and national security.[17] Its efforts to ensure nondisclosure suffered a blow when a 1973 U.S. attorney general’s order to release FBI records to historical researchers was followed the subsequent year by the amendments to the Freedom of Information Act guaranteeing the general public the same rights of access as professors. However, the FBI has since maintained a practice of invoking the FOIA’s exemption provisions to legitimate redacting many files and withholding others. Even absent the larger historical context of the “culture of secrecy” ascribed to the FBI, there is plenty within Kaczynski’s own case, including the government-proposed private “garage sale” of papers that would have produced negligible revenue, to suggest that Kaczynski was right that the government never really was primarily concerned with restituting victims and has only employed the restitution order as a smoke screen to retain possession of the files. But retain possession to what end? While Kaczynski alleged censorship of his ideas, it would seem the government had other reasons to battle for possession of everything it had confiscated in the raid on the Montana cabin, including the cabin. In 2008, Kaczynski’s cabin, his handmade gun and bomb, and the original letter he wrote the New York Times (as FC) demanding publication of his manifesto were loaned by the FBI to the Newseum in Washington, D.C. The Newseum’s exhibit G-Men and Journalists explored the relationships between the press and the FBI in sensational cases. It also featured an interactive display including the names and in many cases photos of all of Kaczynski’s victims. Visitors could use a touch screen to select any of the Unabomber’s victims to learn more about the injuries each one sustained.

The Newseum certainly recognized the value of Kaczynski’s brand name. It not only used Kaczynski’s effects but even his protest of its display for its own self-promotion. Oddly shabbily constructed posters of news clippings documenting Kaczynski’s protests were displayed at the exhibit and outside the front entrance to the Newseum, boasting, “Inside . . . the cabin the ‘Unabomber’ doesn’t want you to see.” But the FBI, we contend, by participating in the Newseum exhibit and loaning the centerpiece, also has sought to use the power of the Kaczynski brand to promote itself. The FBI shows itself willing to display in the G-Men exhibit information (e.g., details about victims) it has claimed to want to keep confidential. Like a candidate trying to control his or her message, the FBI has in such a display used Kaczynski’s notoriety for its own profit, where profit has come to mean, in the case of Kaczynski’s papers, advantage and fame. All of Kaczynski’s effects become murderabilia in the setting of the Newseum. Kaczynski’s papers in this way are no different from his cabin, his protests of the exhibit no different from his empty peanut butter jar, his homemade bomb and gun the FBI loaned the Newseum no different from the poster version of the manifesto the bureau also loaned.

These loans to the Newseum make clear that the government’s real objection to Kaczynski’s plans to donate his papers to the University of Michigan Library was not that his ideas would get out—the Unabomber Manifesto is already in the public domain—but that the government would be deprived of the ability to capitalize on it. The goal of the G-Men exhibit seems to be to polish the image of the FBI and increase its institutional legitimacy at a time when the bureau’s recent failures, chiefly the failure to prevent 9/11, have challenged that legitimacy. If the FBI can convince people that its heroic law enforcement agents prevailed in capturing Kaczynski and foiling other plots, it helps make the bureau more formidable and worthy of public trust. Interestingly, 9/11 is a glaring omission in an exhibit of the “resolved” crises of Waco, Oklahoma City, and the D.C. sniper. In the Newseum, as opposed to the University of Michigan Archives, the FBI is able to construct its chosen narrative without having to deal with contradictory messages from the convict and sharply curtail public engagement with the details of the case. The Newseum asks the public to participate only as passive consumers in the most material sense of the term. The public is not even invited to assume the role of agent of restitution. No portion of the proceeds from the $20 ticket sales to the Newseum will go to the victims, who were supposed to benefit from the proposed public auction of Kaczynski’s memorabilia. Kaczynski’s property may have become murderabilia, but from the FBI’s perspective, it is “its” murderabilia, to profit from as it will.

From Truth to Property

It is not beside the point that the Newseum bills itself as a monument to the First Amendment, drawing dialectical relationships between the freedom of the press guaranteed in that amendment and “truth” at a time when media bias and accuracy are subjects of growing public scrutiny. The Newseum responds to public concerns by presenting a version of the consequentialist position whereby truth is the product of press-mediated discourse. Academics perhaps can more readily see the flaws of this consequentialist argument through the Newseum’s clearly self-interested display than through the AAUP statements that would support the position that truth is a consequence of academic freedom. Even if truth is accepted as the product of discourse, whether mediated by press or by academia, there is little support in academic practice for the consequentialist justification of free speech and academic freedom. Such justification depends on an untested empirical assumption that free discussion more effectively promotes truth than alternative procedures such as hierarchical decision making or expert investigation and analysis. The case for this effectiveness is nothing more than free speech dogma; there is little if any sustained investigation to support such an assumption and much reason to question it. If university research does not effectively or efficiently promote truth in practice (and arguably much of it does not even aspire to), then the consequentialist defense of academic freedom weakens.[18]

Dogma aside, a process that generates truth (however contingently claimed) from intellectual products has recently been replaced in the university by a contractual process by which intellectual products become property that can generate profit or notoriety. Kaczynski sensed a similar process at work in the commutation of his papers into murderabilia, but was too focused on his own process of “truth” revelation to fully appreciate the scope of the government’s possible interests. He didn’t see the Newseum coming. Nevertheless, he usefully did recognize the effect of governmentimposed material constraints on his work. As we discussed, Kaczynski’s chief concern is his ability to communicate his truth to the outside world. According to Kaczynski, such communication requires that he be able to effectively control what he calls his “First Amendment property,” the written material seized from his cabin and that which he continues to produce in prison, in order that he can publicly defend what he believes to be true.[19] In his view, the government would impose a property framework through the restitution lien primarily to deprive him of that opportunity. Kaczynski’s unconventional use of the phrase “First Amendment property” in his second appeal represents his effort to graft a First Amendment argument onto the property framework established by the government. Arguing that the statute authorizing the auction must be unconstitutional on its face because it allows for the possibility that a prisoner’s communication can be cut off entirely, Kaczynski maintains, “If a federal prisoner owes restitution that he cannot pay, then, by taking and selling his copyright, the government can prevent the prisoner from ever publishing anything he may write. If the prisoner is sufficiently well known so that his papers have ‘celebrity’ value, then the government can hold the prisoner virtually incommunicado by seizing for restitution every letter he writes before it leaves the prison.”[20] The court’s order of August 10, 2006, does not go this far and does not allow the government to seize every letter he writes or has written.[21] The statute, as applied to Kaczynski, does not hold him incommunicado. And yet Kaczynski continues to assert that the copies of his work that he would be allowed under the court order are in many cases illegible and constitute material constraints that would affect First Amendment exercise.

Kaczynski is further compromised in his ability to maintain a library or store of his documents by Federal Bureau of Prisons rules that limit the amount of material any convict may possess in his cell. He sometimes has declined offers of books from correspondents on the basis of these rules. He is also forbidden to publish under his name. He complained of this stricture in a 2002 letter to one of his many correspondents: “I can’t publish an article with my name on it in a periodical. Anything I write for a periodical has to be anonymous. This is a goofy rule, and I don’t understand the rationale for it, but the Bureau of Prisons is a bureaucracy, so what can you expect?”[22] Exacting in his citation practices, Kaczynski expresses concern that if he does not possess all the documents confiscated upon his arrest that he will not be able to prove the authenticity of those documents or challenge others’ accounts of the ideas in those papers.[23] In short, Kaczynski maintains that First Amendment freedoms that cannot be exercised because of conditions on property are not First Amendment freedoms at all. At the same time, the government opposes (so far successfully) judicial recognition that the original documents have any relevance to Kaczynski’s First Amendment interests.

Essentially, when faculty express concerns about how the contracts they enter into with their universities might affect their academic freedom, they are expressing concerns as well about the material conditions of their work.

Individual academic freedom relies on certain material preconditions such as access to research materials, opportunity to publish, research resources, and institutional affiliation. Contracts can determine the resources available to faculty, the distribution of research products, participation in publishing and public forums, and other factors relevant to the everyday working conditions necessary to effectively exercise academic freedom. To the extent that these contracts focus on property relations between faculty and institution, they are likely to undermine the possibility for effective exercise of individual academic freedom. Faculty are at a disadvantage in legal disputes over the terms of these contracts as the courts recognize institutional academic freedom and the property rights of employers, thus granting them more power than their faculty employees, effectively denying individual academic freedom for those employees. Even though the university and the FBI are very different institutions with very different goals and even though the FBI’s relationship to Kaczynski is very different from the university’s relationship to any faculty member, the university still has the ability to adopt similar contractual processes to constrain the exercise of undesirable research and use the notoriety of faculty members as well as their desired intellectual products to derive symbolic, if not material, profit.

Professors should, we conclude, be wary of looking to the First Amendment to mediate conflicts between faculty and administration. First Amendment law often must mediate conflicts between speakers since one person’s speech may infringe on another’s, as in the case of hate speech or pornography. So, too, must courts sometimes resolve conflicts between individual faculty members and the institutions that employ them, each of whom claims the protection of academic freedom for their speech. Universities hold the First Amendment cards in these cases, given that institutional academic freedom exists as a matter of law, while no precedent clearly supports the academic freedom of individual faculty members. However, the legal question does not settle the policy question. A university president who decided to turn her or his back on AAUP statements of professional practice on academic freedom just because the university’s legal counsel felt confident of winning the ensuing lawsuits under First Amendment doctrine would still be acting in a self-defeating manner. There are substantial reasons for universities to respect the academic freedom of their faculties, including the disapprobation of professional groups such as the AAUP, faculty resistance, and the likely damage to the public reputation of the institution. Even with the widest possible understanding of the First Amendment, the law may be substantially less protective of individual academic freedom than a rigorous set of professional standards and strong norms of faculty governance over academic decisions.[24]

Academic freedom for individual faculty and for institutions, even though independently justified, should rarely conflict with freedom of inquiry for the public. Professional academics and members of the inquisitive public engage in different projects under distinct frameworks of norms and professional standards, and neither group should interfere beyond the legitimate boundaries of these frameworks. There is no basis on which public freedom of inquiry includes a right to interfere in the professional curricular decisions of universities or individual teachers. Context is important, and people who fill different social roles may need distinct kinds of legal or professional protections, but protection for the public is more likely if freedom of inquiry is not considered the exclusive province of universityaffiliated academics.[25] Should conflicts arise between exercise of public freedom of inquiry and the individual academic freedom of faculty members (finite limits on the number of people who can access a given collection of archival materials, for example), courts can resolve them by balancing a First Amendment guarantee for public freedom of inquiry with institutional academic freedom and the professional norms of the faculty. The public has a stake in a healthy university and vibrant academic culture with strong academic freedom protections as the professoriate plays an important role in knowledge creation with public benefits, as outlined in the AAUP statements on academic freedom.[26] Broader recognition of public freedom of inquiry is important because it is good for the public and good for the professoriate in mutually sustaining ways. Academics need allies against institutional threats to academic freedom, and the public is more likely to support individual academic freedom against the encroachments of institutions if it sees common cause with faculty. As Matthew W. Finkin and Robert C. Post argue, the academic freedom of individual professors depends on public support that would disappear were academic freedom to be seen by the public as merely the privilege of a protected class to research and teach what it pleases, when it pleases.[27] Public freedom of inquiry already can be seen in the examples of public use of archives and the Freedom of Information Act. Public access to government data and documents protects professorial access from being subject to institutional bottlenecks such as an independent review board or some other committee, or a dean or provost concerned about how a certain inquiry might reflect on the university. Because such information is free to all inquirers, academics have more access than they would have if they were “special.”

On our own campuses we also extend access to the public and promote public freedom of inquiry. We have public lectures for which we strive to get as many members of the community as possible to attend and ask questions. A public lecture is an example of professoriate, public, and students engaged in a common experience of inquiry and, when speakers cooperate, discussion. Sometimes we have to balance public and professional or institutional interests. For a popular lecture, access may have to be rationed and decisions made about how many tickets to reserve for the public when demand is high, but we do this all the time in a variety of ways, even within classes closed to the public. Nor does a conception of public freedom of inquiry mean that people can come in off the street to participate in class, sit in on lectures, or determine the content of courses. To say that the public has freedom of inquiry is not to say that it is at liberty to do what it pleases with institutional resources or class time. The distinction between public and closed lectures is one made according to professional norms and institutional structures; we can change it, or not, as we decide through the usual procedures, but the recognition of public freedom of inquiry does not challenge the distinction.

Faculty organizations like the AAUP should of course focus, as they often have, on making the public case for the benefits of freedom in research, scholarship, and teaching. But the argument to protect academic freedom for faculty will be a lot stronger if it avoids a foundation on special rights for professors. We might be tempted in our fight with the institution to mobilize reputation to counter work-for-hire practices that turn faculty into anonymous knowledge workers. Reputation offers protections based on control over one’s persona; however, as the battle for Kaczynski’s papers reminds us, notoriety can also be ceded or co-opted by contract (in Kaczynski’s case, specifically by the disgorgement provision of his plea agreement in which he agrees to forfeit any revenue from interviews or publications to restitution). As Corynne McSherry notes of the mercurial relationships among academic freedom, reputation, and the markets, “It is not hard to imagine that twenty-first-century educational corporations will look to the individual academic persona to provide an organizing principle across a proliferation of ‘learning environments’ and happily use that persona to protect their economic interests.”[28]

The reality is that most faculty labor in anonymity without any celebrity value or public persona, and the public itself is far less interested in shaping the minutiae of what goes on in the university than many of us imagine. All faculty run a far greater risk that they will be compelled to contract away academic freedom or intellectual property rights that they would otherwise hold as unaffiliated citizens than that they will be fired for a expressing a political viewpoint. For instance, were the terms of the AAUP’s 1940 “Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure” to be included in every faculty employment contract, faculty would see a diminution of their academic freedom due to the responsibilities clause. Given the realities of the job market in most disciplines and the weak bargaining position of individual faculty members in most situations, contracts hold as much risk as promise for faculty rights. Faculty might learn from the Kaczynski case that there may be unintended consequences to their freedoms in contracts, and they should be alert that collective bargaining represents the best hope for truly equitable negotiations. Kaczynski’s plea agreement, which was eventually cited as the grounds for the auction, is one he ostensibly entered into voluntarily; had he not signed it, however, he likely would have faced the death penalty. Faculty might be mindful that they are in a much better position than Kaczynski; in facing powerful institutions, their greatest hope for exercising voluntary choices to prevent their work becoming someone else’s property lies not in their uniqueness but in their numbers.

[1] FC, “Industrial Society and Its Future” (unpublished document, 1995). Ted Kaczynski maintained throughout his trial and maintains today that “FC” and not he is the author of “Industrial Society and Its Future” or what is popularly attributed to Kaczynski as the “Unabomber Manifesto.”

[2] See, for example, Brandenburg v. Ohio (1969), Hustler Magazine v. Falwell (1988), and Texas v. Johnson (1989). Those speakers with relatively orthodox or mainstream views rarely need the protection of the speech clauses of the U.S. Constitution.

[3] For a more detailed account of consequentialist free speech arguments, see Samuel P. Nelson, Beyond the First Amendment: The Politics of Free Speech and Pluralism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 2005), 37–41.

[4] Frederick Schauer, “Is There a Right to Academic Freedom?” University of Colorado Law Review 77.4 (2006): 919.

[5] Ibid., 907–8.

[6] Matthew W. Finkin and Robert C. Post argue that “academic freedom consists of the freedom to pursue the scholarly profession according to the standards of the profession” and describe these professional standards in great detail as expressed in the findings of AAUP Committee A in a series of investigations of academic freedom claims. See Matthew W. Finkin and Robert C. Post, For the Common Good: Principles of American Academic Freedom (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2009), 7, 39–48.

[7] This concern is voiced explicitly by Andrew Ross in Malini Johar Schueller and Ashley Dawson, “Academic Labor at the Crossroads? An Interview with Andrew Ross,” Social Text 25.1 (Spring 2007): 117–32.

[8] Grutter v. Bollinger, 539 U.S. 306, 328–29 (2003).

[9] Justice William J. Brennan writing for the Court in Keyishian v. Board of Regents, 385 U.S. 589, 603 (1967).

[10] O’Connor highlights the public interest rationale developed in Justice Lewis F. Powell’s opinion in Regents of the University of California v. Bakke, 438 U.S. 265 (1978) (who in turn quotes Keyishian): “Justice Powell emphasized that nothing less than the ‘nation’s future depends upon leaders trained through wide exposure’ to the ideas and mores of students as diverse as this Nation of many peoples.” Grutter, 539 U.S. at 324.

[11] American Association of University Professors, 1940 Statement of Principles on Academic Freedom and Tenure (Washington, DC: AAUP, 1940), http://www.aaup.org/AAUP/ pubsres/policydocs/contents/1940statement.htm (accessed April 21, 2009).

[12] Frank Donoghue, The Last Professors: The Corporate University and the Fate of the Humanities (New York: Fordham University Press, 2008), 77.

[13] Students for Academic Freedom, Academic Bill of Rights, www.studentsforacademic freedom.org/documents/1925/abor.html (accessed April 21, 2009).

[14] AAUP, “Report: Freedom in the Classroom,” www.aaup.org/AAUP/comm/rep/A/class .htm (accessed May 1, 2009).

[15] Theodore John Kaczynski v. United States, No. 04–10158 (9th Cir. 2005), “Joint Amici Curiae Brief of the Freedom to Read Foundation and the Society of American Archivists,” available at www.archivists.org/news/kaczynski.pdf (accessed April 22, 2009).

[16] Julie Herrada, curator of the Labadie Collection at the University of Michigan (personal e-mail correspondence, July 14, 2008).

[17] Athan G. Theoharis, A Culture of Secrecy: The Government Versus the People’s Right to Know (Lawrence, KS: University Press of Kansas, 1998), 22.

[18] Richard Rorty criticizes customary defenses of academic freedom for their reliance on the search for truth understood in terms of correspondence with reality because this leaves academic freedom vulnerable to changing epistemology. Richard Rorty, “Does Academic Freedom Have Philosophical Presuppositions?” in The Future of Academic Freedom, ed. Louis Menand (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1996), 21–22.

[19] United States v. Theodore John Kaczynski, No. 06–10514 (9th Cir.), “Appellant’s Opening Brief” (filed November 1, 2007), 12.

[20] United States v. Theodore John Kaczynski, No. 06–10514 (9th Cir.), “Appellant’s Motion for Substitution of Counsel, or in the Alternative for Leave to Proceed Pro Se Pursuant to Circuit Rule 4–1(d)” (filed October 4, 2006), 9; “Appellant’s Opening Brief,” 13, 57.

[21] USA v. Kaczynski, no. 2:96–cr-00259–GEB-GGH (E.D. CA), “Order Approving the 7/31/06 Plan” (filed August 10, 2006).

[22] Theodore Kaczynski to unknown, December 24, 2002, Ted Kaczynski Papers, Labadie Collection, Special Collection Library of the University of Michigan, Ann Arbor, box 6, folder 691.

[23] “Appellant’s Motion for Substitution of Counsel,” 7; “Appellant’s Opening Brief,” 69.

[24] The AAUP was initially unsure whether or not it wanted First Amendment law to cover academic freedom, and the organization decided not to file a brief in Sweezy v. New Hampshire, 354 U.S. 234 (1957). J. Peter Byrne, “Academic Freedom: A ‘Special Concern of the First Amendment,’” Yale Law Journal 99 (1989): 251–340, at 291 and 308.

[25] Here Finkin and Post overstate the case for the professoriate’s role in knowledge creation: “academic freedom protects the interests of society in having a professoriate that can accomplish its mission,” where they understand this professional mission to be knowledge creation; “academic freedom rests on a covenant struck between the university as an institution and the general public”; and “academic freedom is the price the public must pay in return for the social good of advancing knowledge.” Finkin and Post, For the Common Good, 39, 42, 44.

[26] Finkin and Post defend this role of the professoriate at length in For the Common Good.

[27] Ibid., 42.

[28] Corynne McSherry, Who Owns Academic Work? Battling for Control of Intellectual Property (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2001), 140.