Saxton T. Pope

Hunting with the Bow & Arrow

I. The Story of the Last Yana Indian

II. How Ishi Made His Bow and Arrow and His Methods of Shooting

III. Ishi's Methods of Hunting

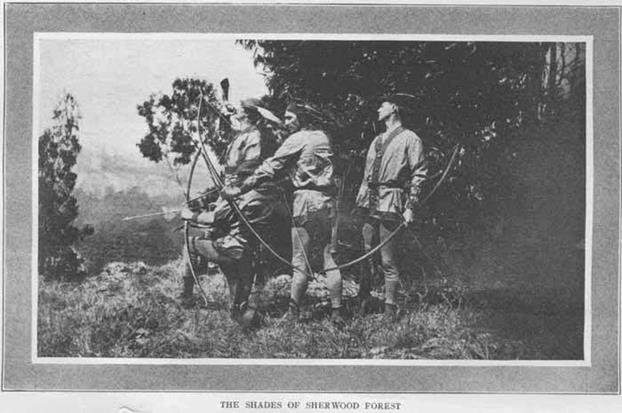

Dedicated to

Robin Hood

A Spirit That at Some Time Dwells in the Heart of Every Youth

I. The Story of the Last Yana Indian

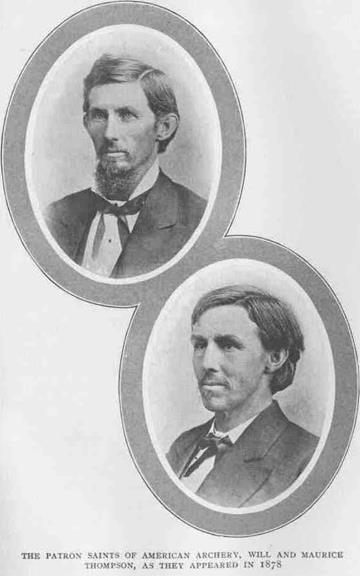

The glory and romance of archery culminated in England before the discovery of America. There, no doubt, the bow was used to its greatest perfection, and it decided the fate of nations. The crossbow and the matchlock had supplanted the longbow when Columbus sailed for the New World.

It was, therefore, a distinct surprise to the first explorers of America that the natives used the bow and arrow so effectively. In fact, the sword and the horse, combined with the white man's superlative self-assurance, won the contest over the aborigines more than the primitive blunderbuss of the times. The bow and arrow was still more deadly than the gun.

With the gradual extermination of the American Indian, the westward march of civilization, and the improvement in firearms, this contest became more and more unequal, and the bow disappeared from the land. The last primitive Indian archer was discovered in California in the year 1911.

When the white pioneers of California descended through the northern part of that State by the Lassen trail, they met with a tribe of Indians known as the Yana, or Yahi. That is the name they called themselves. Their neighbors called them the Nozi, and the white men called them the Deer Creek or Mill Creek Indians. Different from the other tribes of this territory, the Yana would not submit without a struggle to the white man's conquest of their lands.

The Yana were hunters and warriors. The usual California natives were yellow in color, fat and inclined to be peaceable. The Yana were smaller of stature, lithe, of reddish bronze complexion, and instead of being diggers of roots, they lived by the salmon spear and the bow. Their range extended over an area south of Mount Lassen, east of the Sacramento River, for a distance of fifty miles.

From the earliest settlement of the whites, hostilities existed between them. This resulted in definitely organized expeditions against these Indians, and the annual slaughter of hundreds.

The last big round-up of Mill Creek Indians occurred in 1872, when their tribe was surprised at its seasonal harvest of acorns. Upon this occasion a posse of whites killed such a number of natives that it is said the creek was damned with dead bodies. An accurate account of these days may be obtained from Watterman's paper on the Yana Indians.[1]

During one of the final raids upon the Yana, a little band of Indian women and children hid in a cave. Here they were discovered and murdered in cold blood. One of the white scouting party laconically stated that he used his revolver to blow out their brains because the rifle spattered up the cave too much.

So it came to pass, that from two or three thousand people, the Yana were reduced to less than a dozen who escaped extermination. These were mainly women, old men and children. This tribal remnant sought the refuge of the impenetrable brush and volcanic rocks of Deer Creek Canyon. Here they lived by stealth and cunning. Like wild creatures, they kept from sight until the whites quite forgot their existence.

It became almost a legend that wild Indians lived in the Mount Lassen district. From time to time ranchers or sheep herders reported that their flocks had been molested, that signs of Indians had been found or that arrowheads were discovered in their sheep. But little credence was given these rumors until the year 1908, when an electric power company undertook to run a survey line across Deer Creek Canyon with the object of constructing a dam.

One evening, as a party of linemen stood on a log at the edge of the deep swift stream debating the best place to ford, a naked Indian rose up before them, giving a savage snarl and brandishing a spear. In an instant the survey party disbanded, fell from the log, and crossed the stream in record-breaking time. When they stopped to get their breath, the Indian had disappeared. This was the first appearance of Ishi,[2] the Yana.

Next morning an exploring expedition set out to verify the excited report of the night before. The popular opinion was that no such wildman existed, and that the linemen had been seeing things. One of the group offered to bet that no signs of Indians would be found.

As the explorers reached the slide of volcanic boulders where the apparition of the day before had disappeared, two arrows flew past them. They made a run for the top of the slide and reached it just in time to see two Indians vanish in the brush. They left behind them an old white-haired squaw, whom they had been carrying. She was partially paralyzed, and her legs were bound in swaths of willow bark, seemingly in an effort to strengthen them.

The old squaw was wrinkled with age, her hair was cropped short as a sign of mourning, and she trembled with fear. The white men approached and spoke kindly to her in Spanish. But she seemed not to understand their words, and apparently expected only death, for in the past to meet a white man was to die. They gave her water to drink, and tried to make her call back her companions, but without avail.

Further search disclosed two small brush huts hidden among the laurel trees. So cleverly concealed were these structures that one could pass within a few yards and not discern them. In one of the huts acorns and dried salmon had been stored; the other was their habitation. There was a small hearth for indoor cooking; bows, arrows, fishing tackle, a few aboriginal utensils and a fur robe were found. These were confiscated in the white man's characteristic manner. They then left the place and returned to camp.

Next day the party revisited the site, hoping to find the rest of the Indians. These, however, had gone forever.

Nothing more was seen or heard of this little band until the year 1911, when on the outskirts of Oroville, some thirty-two miles from the Deer Creek camp, a lone survivor appeared. Early in the morning, brought to bay by a barking dog, huddled in the corner of a corral, was an emaciated naked Indian. So strange was his appearance and so alarmed was the butcher's boy who found him, that a hasty call for the town constable brought out an armed force to capture him.

Confronted with guns, pistols, and handcuffs, the poor man was sick with fear. He was taken to the city jail and locked up for safekeeping. There he awaited death. For years he had believed that to fall into the hands of white men meant death. All his people had been killed by whites; no other result could happen. So he waited in fear and trembling. They brought him food, but he would not eat; water, but he would not drink. They asked him questions, but he could not speak. With the simplicity of the white man, they brought him other Indians of various tribes, thinking that surely all "Diggers" were the same. But their language was as strange to him as Chinese or Greek.

And so they thought him crazy. His hair was burnt short, his feet had never worn shoes, he had small bits of wood in his nose and ears; he neither ate, drank, nor slept. He was indeed wild or insane.

By this time the news of the wild Indian got into the city papers, and Professor T. T. Watterman, of the Department of Anthropology at the University of California, was sent to investigate the case. He journeyed to Oroville and was brought into the presence of this strange Indian. Having knowledge of many native dialects, Dr. Watterman tried one after the other on the prisoner. Through good fortune, some of the Yana vocabulary had been preserved in the records of the University. Venturing upon this lost language, Watterman spoke in Yana the words, Siwini, which means pine wood, tapping at the same time the edge of the cot on which they sat.

In wonderment, the Indian's face lighted with faint recognition. Watterman repeated the charm, and like a spell the man changed from a cowering, trembling savage. A furtive smile came across his face. He said in his language, I nu ma Yaki--"Are you an Indian?" Watterman assured him that he was.

A great sense of relief entered the situation. Watterman had discovered one of the lost tribes of California; Ishi had discovered a friend.

They clothed him and fed him, and he learned that the white man was good.

Since no formal charges were lodged against the Indian, and he seemed to have no objection, Watterman took him to San Francisco, and there, attached to the Museum of Anthropology, he became a subject of study and lived happily for five years. From him it was learned that his people were all dead. The old woman seen in the Deer Creek episode was his mother; the old man was his uncle. These died on a long journey to Mt. Lassen, soon after their discovery. Here he had burned their bodies and gone into mourning. The fact that the white men took their means of procuring food, as well as their clothing, contributed, no doubt, to the death of the older people.

Half starved and hopeless, he had wandered into civilization. His father, once the chieftain of the Yana tribe, having domain over all the country immediately south of Mt. Lassen, was long since gone, and with him all his people. Ranchers and stockmen had usurped their country, spoiled the fishing, and driven off the game. The acorn trees of the valleys had been taken from them; nothing remained but evil spirits in the land of his forefathers.

Now, however, he had found kindly people who fed him, clothed him, and taught him the mysteries of civilization. When asked his name, he said: "I have none, because there were no people to name me," meaning that no tribal ceremony had been performed. But the old people had called him Ishi, which means "strong and straight one," for he was the youth of their camp. He had learned to make fire with sticks; he knew the lost art of chipping arrowheads from flint and obsidian; he was the fisherman and the hunter. He knew nothing of our modern life. He had no name for iron, nor cloth, nor horse, nor road. He was as primitive as the aborigines of the pre-Columbian period. In fact, he was a man in the Stone Age. He was absolutely untouched by civilization. In him science had a rare find. He turned back the pages of history countless centuries. And so they studied him, and he studied them.

From him they learned little of his personal history and less of that of his family, because an Indian considers it unbecoming to speak much of his own life, and it brings ill luck to speak of the dead. He could not pronounce the name of his father without calling him from the land of spirits, and this he could only do for some very important reason. But he knew the full history of his tribe and their destruction.

His apparent age was about forty years, yet he undoubtedly was nearer sixty. Because of his simple life he was in physical prime, mentally alert, and strong in body.

He was about five feet eight inches tall, well proportioned, had beautiful hands and unspoiled feet.

His features were less aquiline than those of the Plains Indian, yet strongly marked outlines, high cheek bones, large intelligent eyes, straight black hair, and fine teeth made him good to look upon.

As an artisan he was very skilful and ingenious. Accustomed to primitive tools of stone and bone, he soon learned to use most expertly the knife, file, saw, vise, hammer, ax, and other modern implements.

Although he marveled at many of our inventions and appreciated matches, he took great pride in his ability to make fire with two sticks of buckeye. This he could do in less than two minutes by twirling one on the other.

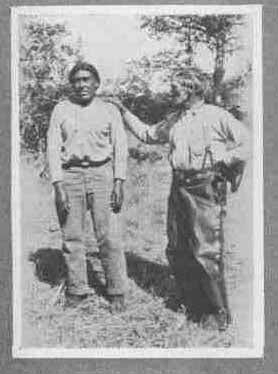

About this time I became an instructor in surgery at the University Medical School, which is situated next to the Museum. Ishi was employed here in a small way as a janitor to teach him modern industry and the value of money. He was perfectly happy and a great favorite with everybody.

From his earliest experience with our community life he manifested little immunity to disease. He contracted all the epidemic infections with which he was brought in contact. He lived a very hygienic existence, having excellent food and sleeping outdoors, but still he was often sick. Because of this I came in touch with him as his physician in the hospital, and soon learned to admire him for the fine qualities of his nature.

Though very reserved, he was kindly, honest, cleanly, and trustworthy. More than this, he had a superior philosophy of life, and a high moral standard.

By degrees I learned to speak his dialect, and spent many hours in his company. He told us the folk lore of his tribe. More than forty myths or animal stories of his have been recorded and preserved. They are as interesting as the stories of Uncle Remus. The escapades of wildcat, the lion, the grizzly bear, the bluejay, the lizard, and the coyote are as full of excitement and comedy as any fairy story.

He knew the history and use of everything in the outdoor world. He spoke the language of the animals. He taught me to make bows and arrows, how to shoot them, and how to hunt, Indian fashion. He was a wonderful companion in the woods, and many days and nights we journeyed together.

After he had been with us three years we took him back to his own country. But he did not want to stay. He liked the ways of the white man, and his own land was full of the spirits of the departed.

He showed us old forgotten camp sites where past chieftains made their villages. He took us to deer licks and ambushes used by his people long ago. One day in passing the base of a great rock he scratched with his toe and dug up the bones of a bear's paw. Here, in years past, they had killed and roasted a bear. This was the camp of Ya mo lo ku. His own camp was called Wowomopono Tetna or bear wallow.

We swam the streams together, hunted deer and small game, and at night sat under the stars by the camp fire, where in a simple way we talked of old heroes, the worlds above us, and his theories of the life to come in the land of plenty, where the bounding deer and the mighty bear met the hunter with his strong bow and swift arrows.

I learned to love Ishi as a brother, and he looked upon me as one of his people. He called me Ku wi, or Medicine Man; more, perhaps, because I could perform little sleight of hand tricks, than because of my profession.

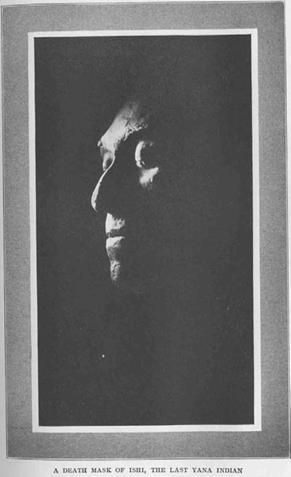

But, in spite of the fact that he was happy and surrounded by the most advanced material culture, he sickened and died. Unprotected by hereditary or acquired immunity, he contracted tuberculosis and faded away before our eyes. Because he had no natural resistance, he received no benefit from such hygienic measures as serve to arrest the disease in the Caucasian. We did everything possible for him, and nursed him to the painful bitter end.

When his malady was discovered, plans were made to take him back to the mountains whence he came and there have him cared for properly. We hoped that by this return to his natural elements he would recover. But from the inception of his disease he failed so rapidly that he was not strong enough to travel.

Consumed with fever and unable to eat nourishing food, he seemed doomed from the first. After months of misery he suddenly developed a tremendous pulmonary hemorrhage. I was with him at the time, directed his medication, and gently stroked his hand as a small sign of fellowship and sympathy. He did not care for marked demonstrations of any sort.

He was a stoic, unafraid, and died in the faith of his people.

As an Indian should go, so we sent him on his long journey to the land of shadows. By his side we placed his fire sticks, ten pieces of dentalia or Indian money, a small bag of acorn meal, a bit of dried venison, some tobacco, and his bow and arrows.

These were cremated with him and the ashes placed in an earthen jar. On it is inscribed "Ishi, the last Yana Indian, 1916."

And so departed the last wild Indian of America. With him the neolithic epoch terminates. He closes a chapter in history. He looked upon us as sophisticated children--smart, but not wise. We knew many things and much that is false. He knew nature, which is always true. His were the qualities of character that last forever. He was essentially kind; he had courage and self-restraint, and though all had been taken from him, there was no bitterness in his heart. His soul was that of a child, his mind that of a philosopher.

With him there was no word for good-by. He said: "You stay, I go."

He has gone and he hunts with his people. We stay, and he has left us the heritage of the bow.

II. How Ishi Made His Bow and Arrow and His Methods of Shooting

Although much has been written in history and fiction concerning the archery of the North American Indian, strange to say, very little has been recorded of the methods of manufacture of their weapons, and less in accurate records of their shooting.

It is a great privilege to have lived with an unspoiled aborigine and seen him step by step construct the most perfect type of bow and arrow.

The workmanship of Ishi was by far the best of any Indian in America; compared with thousands of specimens in the museum, his arrows were the most carefully and beautifully made; his bow was the best.

It would take too much time to go into the minute details of his work, and this has all been recorded in anthropologic records,[3] but the outlines of his methods are as follows:

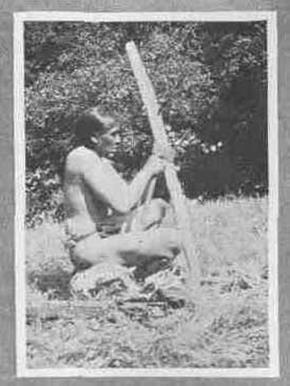

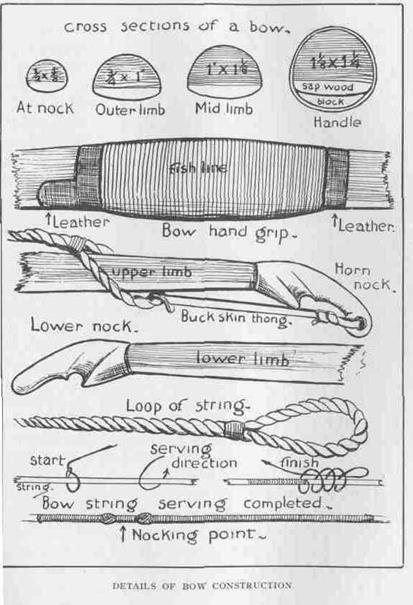

The bow, Ishi called man-nee. It was a short, flat piece of mountain juniper backed with sinew. The length was forty-two inches, or, as he measured it, from the horizontally extended hand to the opposite hip. It was broadest at the center of each limb, approximately two inches, and half an inch thick. The cross-section of this part was elliptical. At the center of the bow the handgrip was about an inch and a quarter wide by three-quarters thick, a cross-section being ovoid. At the tips it was curved gently backward and measured at the nocks three-quarters by one-half an inch. The nock itself was square shouldered and terminated in a pin half an inch in diameter and an inch long.

The wood was obtained by splitting a limb from a tree and utilizing the outer layers, including the sap wood. By scraping and rubbing on sandstone, he shaped and finished it. The recurved tips of the bow he made by bending the wood backward over a heated stone. Held in shape by cords and binding to another piece of wood, he let his bow season in a dark, dry place. Here it remained from a few months to years, according to his needs. After being seasoned he backed it with sinew. First he made a glue by boiling salmon skin and applying it to the roughened back of the bow. When it was dry he laid on long strips of deer sinew obtained from the leg tendons. By chewing these tendons and separating their fibers, they became soft and adhesive. Carefully overlapping the ends of the numerous fibers he covered the entire back very thickly. At the nocks he surrounded the wood completely and added a circular binding about the bow.

During the process of drying he bound the sinew tightly to the bow with long, thin strips of willow bark. After several days he removed this bandage and smoothed off the edges of the dry sinew, sized the surface with more glue and rubbed everything smooth with sandstone. Then he bound the handgrip for a space of four inches with a narrow buckskin thong.

In his native state he seems never to have greased his bow nor protected it from moisture, except by his bow case, which was made of the skin from a cougar's tail. But while with us he used shellac to protect the glue and wood. Other savages use buck fat or bear grease.

The bowstring he made of the finer tendons from the deer's shank. These he chewed until soft, then twisted them tightly into a cord having a permanent loop at one end and a buckskin strand at the other. While wet the string was tied between two twigs and rubbed smooth with spittle. Its diameter was one-eighth of an inch, its length about forty-eight inches. When dry the loop was applied to the upper nock of his bow while he bent the bow over his knee and wound the opposite end of the string about the lower nock. The buckskin thong terminating this portion of the string made it easier to tie in several half hitches.

When braced properly the bowstring was about five inches from the belly of the bow. And when not in use and unstrung the upper loop was slipped entirely off the nock, but held from falling away from the bow by a second small loop of buckskin.

Drawn to the full length of an arrow, which was about twenty-six inches, exclusive of the foreshaft, his bow bent in a perfect arc slightly flattened at the handle. Its pull was about forty-five pounds, and it could shoot an arrow about two hundred yards.

This is not the most powerful type of weapon known to Indians, and even Ishi did make stronger bows when he pleased; but this seemed to be the ideal weight for hunting, and it certainly was adequate in his hands.

According to English standards, it was very short; but for hunting in the brush and shooting from crouched postures, it seems better fitted for the work than a longer weapon.

According to Ishi, a bow left strung or standing in an upright position, gets tired and sweats. When not in use it should be lying down; no one should step over it; no child should handle it, and no woman should touch it. This brings bad luck and makes it shoot crooked. To expunge such an influence it is necessary to wash the bow in sand and water.

In his judgment, a good bow made a musical note when strung and the string is tapped with the arrow. This was man's first harp, the great grandfather of the pianoforte.

By placing one end of his bow at the corner of his open mouth and tapping the string with an arrow, the Yana could make sweet music. It sounded like an Aeolian harp. To this accompaniment Ishi sang a folk-song telling of a great warrior whose bow was so strong that, dipping his arrow first in fire, then in the ocean, he shot at the sun. As swift as the wind, his arrow flew straight in the round open door of the sun and put out its light. Darkness fell upon the earth and men shivered with cold. To prevent themselves from freezing they grew feathers, and thus our brothers, the birds, were born.

Ishi called an arrow sa wa.

In making arrows the first thing is to get the shafts. Ishi used many woods, but he preferred witch hazel. The long, straight stems of this shrub he cut in lengths of thirty-two inches, having a diameter of three-eighths of an inch at the base when peeled of bark.

He bound a number of these together and put them away in a shady place to dry. After a week or more, preferably several months, he selected the best shafts and straightened them. This he accomplished by holding the concave surface near a small heap of hot embers and when warm he either pressed his great toe on the opposite side, or he bent the wood backward on the base of the thumb. Squinting down its axis he lined up the uneven contours one after the other and laid the shaft aside until a series of five was completed. He made up arrows in lots of five or ten, according to the requirements, his fingers being the measure.

The sticks thus straightened he ran back and forth between two grooved pieces of sandstone or revolved them on his thigh while holding the stones in his hand, until they were smooth and reduced to a diameter of about five-sixteenths of an inch. Next they were cut into lengths of approximately twenty-six inches. The larger end was now bound with a buckskin thong and drilled out for the depth of an inch and a half to receive the end of the foreshaft. He drilled this hole by fixing a long, sharp bone in the ground between his great toes and revolved the upright shaft between his palms on this fixed point, the buckskin binding keeping the wood from splitting.

The foreshaft was made of heavier wood, frequently mountain mahogany. It was the same diameter as the arrow, only tapering a trifle toward the front end, and usually was about six inches long. This was carefully shaped into a spindle at the larger end and set in the recently drilled hole of the shaft, using glue or resin for this purpose. The joint was bound with chewed sinew, set in glue.

The length of an arrow, over all, was estimated by Ishi in this manner. He placed one end on the top of his breast-bone and held the other end out in his extended left hand. Where it touched the tip of his forefinger it was cut as the proper length. This was about thirty-two inches.

The rear end of his arrow was now notched to receive the bowstring. He filed it with a bit of obsidian, or later on, with three hacksaw blades bound together until he made a groove one-eighth of an inch wide by three-eighths deep. The opposite end of the shaft was notched in a similar way to receive the head. The direction of this latter cut was such that when the arrow was on the bow the edge of the arrowhead was perpendicular, for the fancied reason that in this position the arrow when shot enters between the ribs of an animal more readily. He did not seem to recognize that an arrow rotates.

At this stage he painted his shafts. The pigments used in the wilds were red cinnabar, black pigment from the eye of trout, a green vegetable dye from wild onions, and a blue obtained, he said, from the root of a plant. These were mixed with the sap or resin of trees and applied with a little stick or hairs from a fox's tail drawn through a quill.

His usual design was a series of alternating rings of green and black starting two inches from the rear end and running four inches up the shaft. Or he made small circular dots and snaky lines running down the shaft for a similar distance. When with us he used dry colors mixed with shellac, which he preferred to oil paints because they dried quicker. The painted area, intended for the feathers, is called the shaftment and not only helps in finding lost arrows, but identifies the owner. This entire portion he usually smeared with thin glue or sizing.

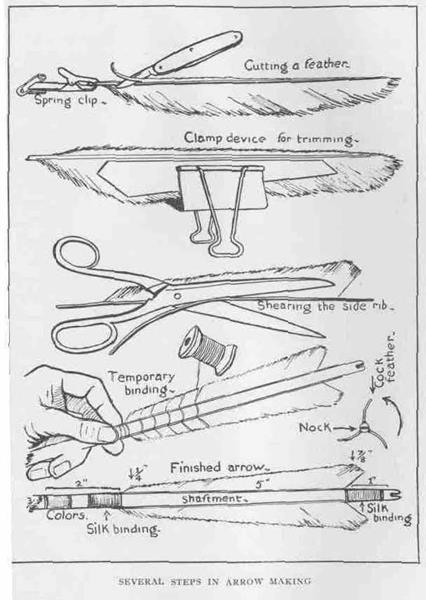

A number of shafts having been similarly prepared, the Indian was ready to feather them. A feather he called pu nee. In fledging arrows Ishi used eagle, buzzard, hawk or flicker feathers. Owl feathers Indians seem to avoid, thinking they bring bad luck. By preference he took them from the wings, but did not hesitate to use tail feathers if reduced to it. With us he used turkey pinions.

Grasping one between the heel of his two palms he carefully separated the bristles at the tip of the feather with his fingers and pulled them apart, splitting the quill its entire length. This is called stripping a feather. Taking the wider half he firmly held one end on a rock with his great toe, and the other end between the thumb and forefinger of his left hand. With a piece of obsidian, or later on a knife blade, he scraped away the pith until the rib was thin and flat.

Having prepared a sufficient number in this way he gathered them in groups of three, all from similar wings, tied them with a bit of string and dropped them in a vessel of water. When thoroughly wet and limp they were ready for use.

While he chewed up a strand of sinew eight or ten inches long, he picked up a group of feathers, stripped off the water, removed one, and after testing its strength, folded the last two inches of bristles down on the rib, and the rest he ruffled backward, thus leaving a free space for later binding. He prepared all three like this.

Picking up an arrow shaft he clamped it between his left arm and chest, holding the rear end above the shaftment in his left hand. Twirling it slowly in this position, he applied one end of the sinew near the nock, fixing it by overlapping. The first movements were accomplished while holding one extremity of the sinew in his teeth; later, having applied the feathers to the stick, he shifted the sinew to the grasp of the right thumb and forefinger.

One by one he laid the feathers in position, binding down the last two inches of stem and the wet barbs together. The first feather he applied on a line perpendicular to the plane of the nock; the two others were equidistant from this. For the space of an inch he lapped the sinew about the feathers and arrow-shaft, slowly rotating it all the while, at last smoothing the binding with his thumb nail.

The rear ends having been lashed in position, the arrow was set aside to dry while the rest were prepared.

Five or ten having reached this stage and the binding being dry and secure, he took one again between his left arm and chest, and with his right hand drew all the feathers straight and taut, down the shaft. Here he held them with the fingers of his left hand. Having marked a similar place on each arrow where the sinew was to go, he cut the bristles off the rib. At this point he started binding with another piece of wet sinew. After a few turns he drew the feathers taut again and cut them, leaving about a half inch of rib. This he bound down completely to the arrow-shaft and finished all by smoothing the wet lapping with his thumb nail.

The space between the rib and the wood he sometimes smeared with more glue to cause the feather to adhere to the shaft, but this was not the usual custom with him. After all was dry and firm, Ishi took the arrow and beat it gently across his palm so that the feathers spread out nicely.

As a rule the length of his feathers was four inches, though on ceremonial arrows they often were as long as eight inches.

After drying, the feathers were cut with a sharp piece of obsidian, using a straight stick as a guide and laying the arrow on a flat piece of wood. When with us he trimmed them with scissors, making a straight cut from the full width of the feather in back, to the height of a quarter of an inch at the forward extremity. On his arrows he left the natural curve of the feather at the nock, and while the rear binding started an inch or more from the butt of the arrow, the feather drooped over the nock. This gave a pretty effect and seemed to add to the steering qualities of the missile.

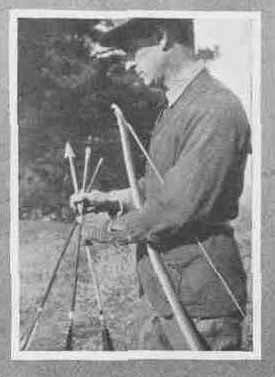

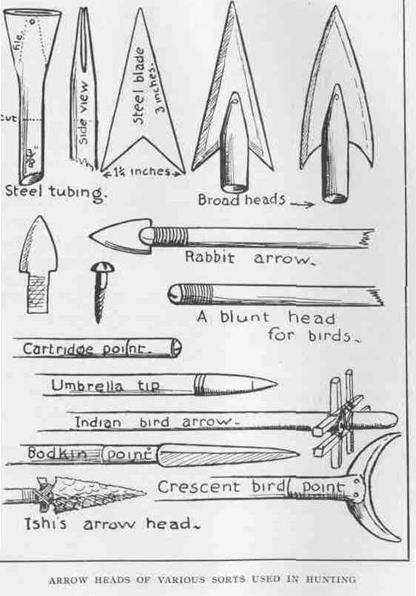

Two kinds of points were used on Ishi's arrows. One was the simple blunt end of the shaft bound with sinew used for killing small game and practice shots. The other was his hunting head, made of flint or obsidian. He preferred the latter.

Obsidian was used as money among the natives of California. A boulder of this volcanic glass was packed from some mountainous districts and pieces were cracked off and exchanged for dried fish, venison, or weapons. It was a medium of barter. Although all men were more or less expert in flaking arrowheads and knives, the better grades of bows, arrows, and arrow points were made by the older, more expert specialists of the tribe.

Ishi often referred to one old Indian, named Chu no wa yahi, who lived at the base of a great cliff with his crazy wife. This man owned an ax, and thus was famous for his possessions as well as his skill as a maker of bows. From a distant mountain crest one day Ishi pointed out to me the camp of this Indian who was long since dead. If ever Ishi wished to refer to a hero of the bow, or having been beaten in a shot, he always told us what Chu no wa yahi could have done.

To make arrowheads properly one should smear his face with mud and sit out in the hot sun in a quiet secluded spot. The mud is a precaution against harm from the flying chips of glass, possibly also a good luck ritual. If by chance a bit of glass should fly in the eye, Ishi's method of surgical relief was to hold his lower lid wide open with one finger while he slapped himself violently on the head with the other hand. I am inclined to ascribe the process of removal more to the hydraulic effect of the tears thus started than to the mechanical jar of the treatment.

He began this work by taking one chunk of obsidian and throwing it against another; several small pieces were thus shattered off. One of these, approximately three inches long, two inches wide and half an inch thick, was selected as suitable for an arrowhead, or haka. Protecting the palm of his left hand by a piece of thick buckskin, Ishi placed a piece of obsidian flat upon it, holding it firmly with his fingers folded over it.

In his right hand he held a short stick on the end of which was lashed a sharp piece of deer horn. Grasping the horn firmly while the longer extremity lay beneath his forearm, he pressed the point of the horn against the edge of the obsidian. Without jar or blow, a flake of glass flew off, as large as a fish scale. Repeating this process at various spots on the intended head, turning it from side to side, first reducing one face, then the other, he soon had a symmetrical point. In half an hour he could make the most graceful and perfectly proportioned arrowhead imaginable. The little notches fashioned to hold the sinew binding below the barbs he shaped with a smaller piece of bone, while the arrowhead was held on the ball of his thumb.

Flint, plate glass, old bottle glass, onyx--all could be worked with equal facility. Beautiful heads were fashioned from blue bottles and beer bottles.

The general size of these points was two inches for length, seven-eighths for width, and one-eighth for thickness. Larger heads were used for war and smaller ones for shooting bears.

Such a head, of course, was easily broken if the archer missed his shot. This made him very careful about the whole affair of shooting.

When ready for use, these heads were set on the end of the shaft with heated resin and bound in place with sinew which encircled the end of the arrow and crossed diagonally through the barb notches with many recurrences.

Such a point has better cutting qualities in animal tissue than has steel. The latter is, of course, more durable. After entering civilization, Ishi preferred to use iron or steel blades of the same general shape, or having a short tang for insertion in the arrowhead.

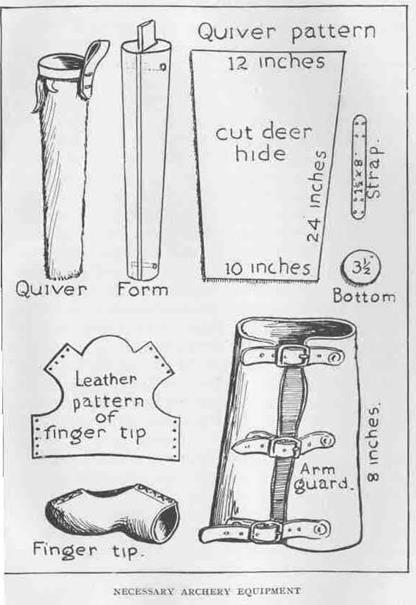

Ishi carried anywhere from five to sixty arrows in a quiver made of otter skin which hung suspended by a loop of buckskin over his left shoulder.

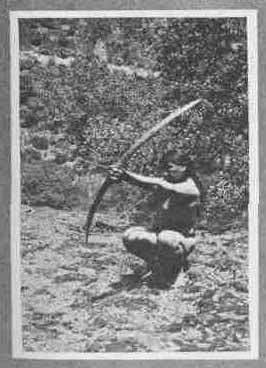

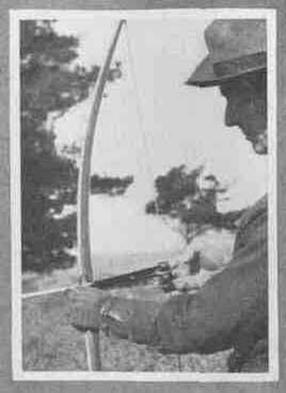

His method of bracing or stringing the bow was as follows: Grasping it with his right hand at its center, with the belly toward him, and the lower end on his right thigh, he held the upper end with his left hand while the loop of the string rested between his finger and thumb. By pressing downward at the handle and pulling upward with the left hand he so sprung the bow that the loop of the cord could be slipped over the upper nock.

In nocking his arrow, the bow was held diagonally across the body, its upper end pointing to the left. It was held lightly in the palm of the left hand so that it rested loosely in the notch of the thumb while the fingers partially surrounded the handle. Taking an arrow from his quiver, he laid it across the bow on its right side where it lay between the extended fingers of his left hand. He gently slid the arrow forward until the nock slipped over the string at its center. Here he set it properly in place and put his right thumb under the string, hooked upward ready to pull. At the same time he flexed his forefinger against the side of the arrow, and the second finger was placed on the thumb nail to strengthen the pull.

Thus he accomplished what is known as the Mongolian release.

Only a few nations ever used this type of arrow release, and the Yana seem to have been the only American natives to do so.[4]

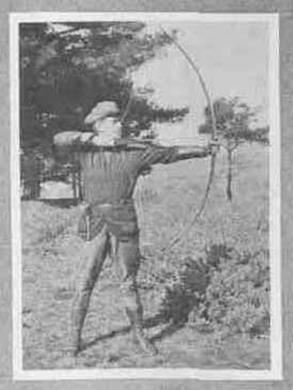

To draw his bow he extended his left arm. At the same time he pulled his right hand toward him. The bow arm was almost in front of him, while his right hand drew to the top of his breast bone. With both eyes open he sighted along his shaft and estimated the elevation according to the distance to be shot.

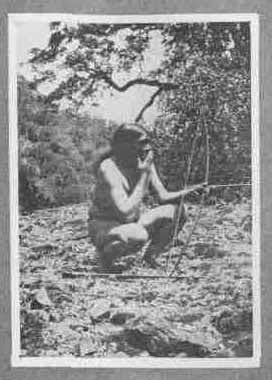

He released firmly and without change of position until the arrow hit. He preferred to shoot kneeling or squatting, for this was most favorable for getting game.

His shooting distances were from ten yards up to fifty. Past this range he did not think one should shoot, but sought rather to approach his game more closely.

In his native state he practiced shooting at little oak balls, or bundles of grass bound to represent rabbits, or little hoops of willow rolled along the ground. Like all other archers, if Ishi missed a shot he always had a good excuse. There was too much wind, or the arrow was crooked, or the bow had lost its cast, or, as a last resource, the coyote doctor bewitched him, which is the same thing we mean when we say it is just bad luck. While with us he shot at the regulation straw target, and he is the first and only Indian of whose shooting any accurate records have been made.

Many exaggerated reports exist concerning the accuracy of the shooting of American Indians; but here we have one who shot ever since childhood, who lived by hunting, and must have been as good, if not better, than the average.

He taught us to shoot Indian style at first, but later we learned the old English methods and found them superior to the Indian. At the end of three months' practice, Dr. J. V. Cooke and I could shoot as well as Ishi at targets, but he could surpass us at game shooting.

Ishi never thought very much of our long bows. He always said, "Too much man-nee." And he always insisted that arrows should be painted red and green.

But when we began beating him at targets, he took all his shafts home and scraped the paint off them, putting back rings of blue and yellow, doubtless to change his luck. In spite of our apparent superiority at some forms of shooting, he never changed his methods to meet competition. We, of course, did not want him to.

Small objects the size of a quail the Indian could hit with regularity up to twenty yards. And I have seen him kill ground squirrels at forty yards; yet at the same distances he might miss a four-foot target. He explained this by saying that the target was too large and the bright colored rings diverted the attention. He was right.

There is a regular system of shooting in archery competition. In America there is what is known as the American Round, which consists of shooting thirty arrows at each of the following distances: sixty, fifty, and forty yards. The bull's-eye on the target is a trifle over nine inches and is surrounded by four rings of half this diameter. Their value is 9, 7, 5, 3, 1, successively counting from the center outward. The target itself is constructed of straw, bound in the form of a mat four feet in diameter, covered with a canvas facing.

Counting the hits and scores on the various distances, a good archer will make the following record. Here is Arthur Young's best score:

March 25, 1917.

| At 60 yards | 30 hits | 190 score | 11 golds |

| 50 yards | 30 hits | 198 score | 9 golds |

| 40 yards | 30 hits | 238 score | 17 golds |

| Total | 90 hits | 626 score | 37 golds |

This is one of the best scores made by American archers.

Ishi's best record is as follows:

October 23, 1914.

| At 60 yards | 10 hits | 32 score | |

| 50 yards | 20 hits | 92 score | 2 golds |

| 40 yards | 19 hits | 99 score | 2 golds |

| Total | 49 hits | 223 score | 4 golds |

His next best score was this:

| At 60 yards | 13 hits | 51 score |

| 50 yards | 17 hits | 59 score |

| 40 yards | 22 hits | 95 score |

| Total | 52 hits | 205 score |

My own best practice American round is as follows:

May 22, 1917.

| At 60 yards | 29 hits | 157 score |

| 50 yards | 29 hits | 185 score |

| 40 yards | 30 hits | 196 score |

| Total | 88 hits | 538 score |

Anything over 500 is considered good shooting.

It will be seen from this that the Indian was not a good target shot, but in field shooting and getting game, probably he could excel the white man.

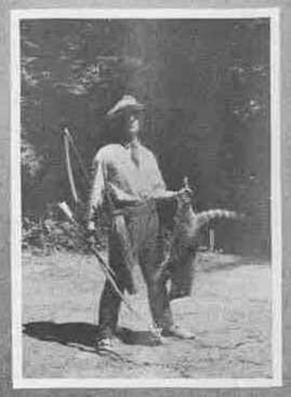

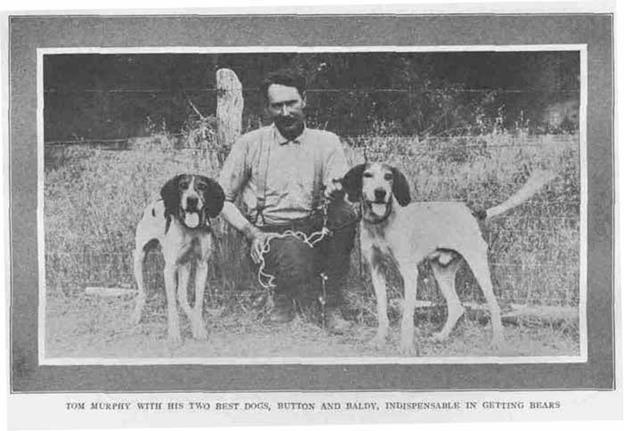

III. Ishi's Methods of Hunting

Hunting with Ishi was pure joy. Bow in hand, he seemed to be transformed into a being light as air and as silent as falling snow. From the very first we went on little expeditions into the country where, without appearing to instruct, he was my teacher in the old, old art of the chase. I followed him into a new system of getting game. We shot rabbits, quail, and squirrels with the bow. His methods here were not so well defined as in the approach to larger game, but I was struck from the first by his noiseless step, his slow movements, his use of cover. These little animals are flushed by sound and sight, not scent. Another prominent feature of Ishi's work in the field was his indefatigable persistence. He never gave up when he knew a rabbit was in a clump of brush. Time meant nothing to him; he simply stayed until he got his game. He would watch a squirrel hole for an hour if necessary, but he always got the squirrel.

He made great use of the game call. We all know of duck and turkey calls, but when he told me that he lured rabbits, tree squirrels, wildcats, coyote, and bear to him, I thought he was romancing. Going along the trail, he would stop and say, "Ineja teway--bjum--metchi bi wi," or "This is good rabbit ground." Then crouching behind a suitable bush as a blind, he would place the fingers of his right hand against his lips and, going through the act of kissing, he produced a plaintive squeak similar to that given by a rabbit caught by a hawk or in mortal distress. This he repeated with heartrending appeals until suddenly one or two or sometimes three rabbits appeared in the opening. They came from distances of a hundred yards or more, hopped forward, stopped and listened, hopped again, listened, and ultimately came within ten or fifteen yards while Ishi dragged out his squeak in a most pathetic manner. Then he would shoot.

To test his ability one afternoon while hunting deer, I asked the Yana to try his call in twelve separate locations. From these twelve calls we had five jackrabbits and one wildcat approach us. The cat came out of the forest, cautiously stepped nearer and sat upon a log in a bright open space not more than fifty yards away while I shot three arrows at him, one after the other; the last clipped him between the ears.

This call being a cry of distress, rabbits and squirrels come with the idea of protecting their young. They run around in a circle, stamp their feet, and make great demonstrations of anger, probably as much to attract the attention of the supposed predatory beast and decoy him away, as anything else.

The cat, the coyote, and the bear come for no such humane motive; they are thinking of food, of joining the feast.

I learned the call myself, not perfectly, but well enough to bring squirrels down from the topmost branches of tall pines, to have foxes and lynx approach me, and to get rabbits.

Not only could Ishi call the animals, but he understood their language. Often when we have been hunting he has stopped and said, "The squirrel is scolding a fox." At first I said to him, "I don't believe you." Then he would say, "Wait! Look!" Hiding behind a tree or rock or bush, in a few minutes we would see a fox trot across the open forest.

It seemed that for a hawk or cat or man, the squirrel has a different call, such that Ishi could say without seeing, what molested his little brother.

Often have we stopped and rested because, so he said, a bluejay called far and wide, "Here comes a man!" There was no use going farther, the animals all knew of our presence. Only a white hunter would advance under these circumstances.

Ishi could smell deer, cougar, and foxes like an animal, and often discovered them first this way. He could imitate the call of quail to such an extent that he spoke a half-dozen sentences to them. He knew the crow of the cock on sentinel duty when he signals to others; he knew the cry of warning, and the run-to-shelter cry of the hen; her command to her little ones to fly; and the "lie low" cluck; then at last the "all's well" chirp.

Deer he could call in the fawn season by placing a folded leaf between his lips and sucking vigorously. This made a bleat such as a lamb gives, or a boy makes blowing on a blade of grass between his thumbs.

He also enticed deer by means of a stuffed buck's head which he wore as a cap, and bobbing up and down behind bushes excited their curiosity until they approached within bow-shot. Ordinarily in hunting deer, the Indian used what is termed the still hunt, but with him it was more than that. First of all he studied the country for its formation of hills, ridges, valleys, canyons, brush and timber. He observed the direction of the prevailing winds, the position of the sun at daybreak and evening. He noted the water holes, game trails, "buck look-outs," deer beds, the nature of the feeding grounds, the stage of the moon, the presence of salt licks, and many other features of importance. If possible, he located the hiding-place of the old bucks in daytime, all of which every careful hunter does. Next, he observed the habits of game, and the presence or absence of predatory beasts that kill deer.

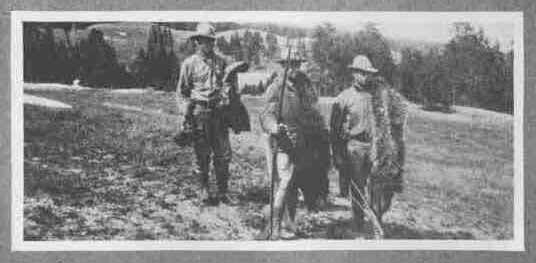

Having decided these and other questions, he prepared for the hunt. He would eat no fish the day before the hunt, and smoke no tobacco, for these odors are detected a great way off. He rose early, bathed in the creek, rubbed himself with the aromatic leaves of yerba buena, washed out his mouth, drank water, but ate no food. Dressed in a loin cloth, but without shirt, leggings or moccasins, he set out, bow and quiver at his side. He said that clothing made too much noise in the brush, and naturally one is more cautious in his movements when reminded by his sensitive hide that he is touching a sharp twig.

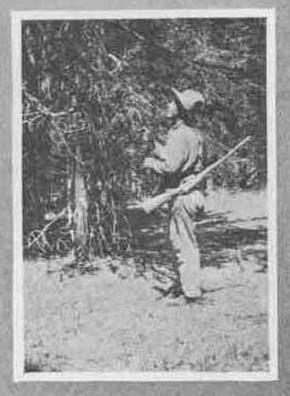

From the very edge of camp, until he returned, he was on the alert for game, and the one obvious element of his mental attitude was that he suspected game everywhere. He saw a hundred objects that looked like deer, to every live animal in reality. He took it for granted that ten deer see you where you see one--so see it first! On the trail, it was a crime to speak. His warning note was a soft, low whistle or a hiss. As he walked, he placed every footfall with precise care; the most stealthy step I ever saw; he was used to it; lived by it. For every step he looked twice. When going over a rise of ground he either stooped, crawled or let just his eyes go over the top, then stopped and gazed a long time for the slightest moving twig or spot of color. Of course, he always hunted up wind, unless he were cutting across country or intended to flush game.

At sunrise and sunset he tried always to get between the sun and his game. He drifted between the trees like a shadow, expectant and nerved for immediate action.

Some Indians, covering their heads with tall grass, can creep up on deer in the open, and rising suddenly to a kneeling posture shoot at a distance of ten or fifteen yards. But Ishi never tried this before me. Having located his quarry, he either shot, at suitable ranges, or made a detour to wait the passing of the game or to approach it from a more favorable direction. He never used dogs in hunting.

When a number of people hunted together, Ishi would hide behind a blind at the side of a deer trail and let the others run the deer past. In his country we saw old piles of rock covered with lichen and moss that were less than twenty yards from well-marked deer trails. For numberless years Indians had used these as blinds to secure camp meat.

In the same necessity, the Indian would lie in wait near licks or springs to get his food; but he never killed wantonly.

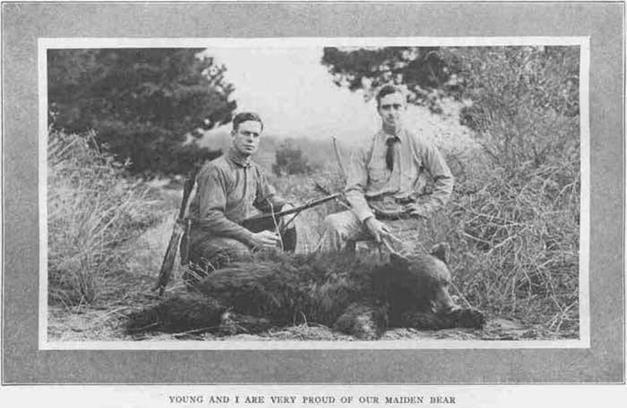

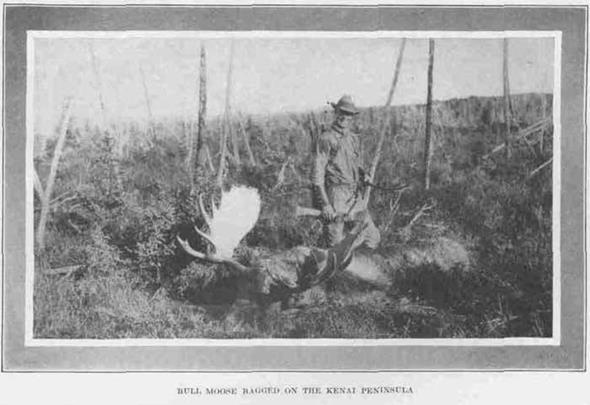

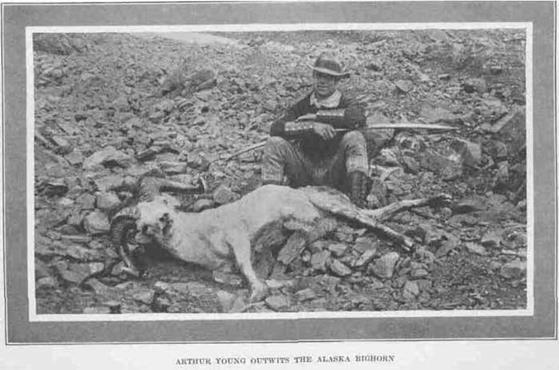

Although Ishi took me on many deer hunts and we had several shots at deer, owing to the distance or the fall of the ground or obstructing trees, we registered nothing better than encouraging misses. He was undoubtedly hampered by the presence of a novice, and unduly hastened by the white man's lack of time. His early death prevented our ultimate achievement in this matter, so it was only after he had gone to the Happy Hunting Grounds that I, profiting by his teachings, killed my first deer with the bow.

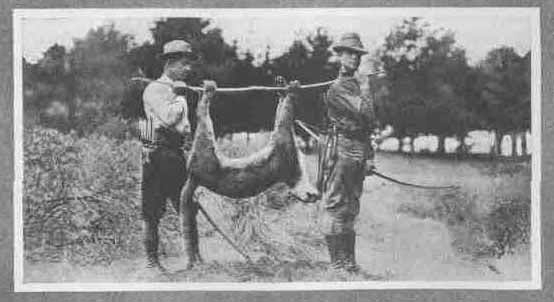

That he had shot many deer, even since boyhood, there was no doubt. To prove that he could shoot through one with his arrows, I had him discharge several at a buck killed by our packer. Shooting at forty yards, one arrow went through the chest wall, half its length; another struck the spine and fractured it, both being mortal wounds.

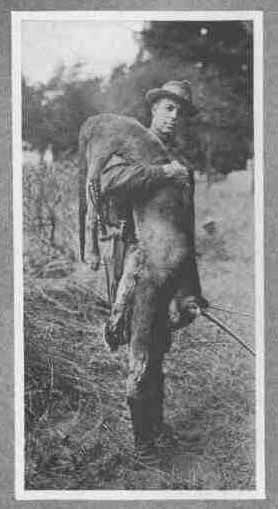

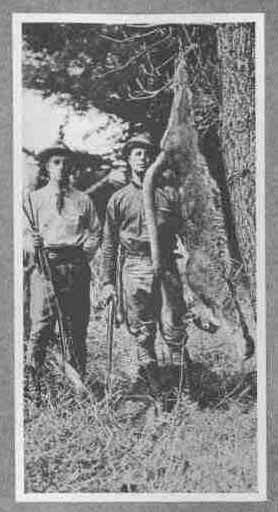

It was the custom of his tribe to hunt until noon, when by that time they usually had several deer, obtained, as a rule, by the ambush method. Having pre-arranged the matter, the women appeared on the scene, cut up the meat, cooked part of it, principally the liver and heart, and they had a feast on the spot. The rest was taken to camp and made into jerky.

In skinning animals, the Indian used an obsidian knife held in his hand by a piece of buckskin. I found this cut better than the average hunting knife sold to sportsmen. Often in skinning rabbits he would make a small hole in the skin over the abdomen and blow into this, stripping the integument free from the body and inflating it like a football, except at the legs.

In skinning the tail of an animal, he used a split stick to strip it down, and did it so dextrously that it was a revelation of how easy this otherwise difficult process may be when one knows how. He tanned his skins in the way customary with most savages: clean skinning, brain emulsion, and plenty of elbow grease.

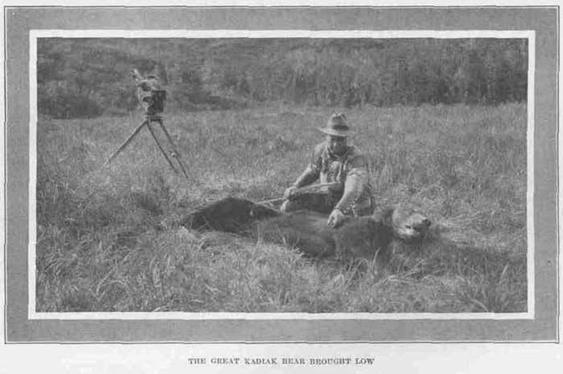

His people killed bear with the bow and arrow. Ishi made a distinction between grizzly bear, which he called tet na, and black bear, which he called bo he. The former had long claws, could not climb trees, and feared nothing. He was to be let alone. The other was "all same pig." The black bear, when found, was surrounded by a dozen or more Indians who built fires, and discharging their arrows at his open mouth, attempted to kill him. If he charged, a burning brand was snatched from the fire and thrust in his face while the others shot him from the side. Thus they wore him down and at last vanquished him.

In his youth, Ishi killed a cinnamon bear single handed. Finding it asleep on a ledge of rock, he sneaked close to it and gave a loud whistle. The bear rose up on its hind legs and Ishi shot him through the chest. With a roar the bear fell off the ledge and the Indian jumped after him. With a short-handled obsidian spear he thrust him through the heart. The skin of this bear now hangs in the Museum of Anthropology in mute testimony of the courage and daring of Ishi. Had this young man been given a name, perhaps they would have called him Yellow Bear.

While he shot many birds, I never saw Ishi try wing shooting except at eagles or hawks. For these he would use an arrow on which he had smeared mud to make it dark in color. A light shaft is readily discerned by these birds, and I have often seen them dodge an arrow. But the darker one is almost invisible head on. The feathers of the arrows were close cropped to make them swift and noiseless.

The sound of a bowstring is that of a sharp twang accompanied by a muffled crack. To avoid this and make a silent shot, the Indian bound his bow at the nocks with weasel fur; this effectually damped the vibration of the string, while the passage of the arrow across the bow, which gives the slight crack, is abolished by a heavy padding of buckskin at this point.

Ishi never wore an arm guard or glove or finger stalls to protect himself as other archers do. He seemed not to need them. When he released the arrow, the bow rotated in his hand so that the string faced in the opposite direction from which it started. His thumb alone drew the string, and this was so toughened that it needed no leather covering.

In a little bag he carried extra arrowheads and sinews, so that in a pinch he could mend his arrows.

When not actually in use, he promptly unstrung his bow, and gently straightened it by hand. In cold weather he heated it over a fire before bracing it. The slightest moisture would deter him from shooting, unless absolutely necessary--he was so jealous of his tackle. If his bowstring stretched in the heat or dampness, as sinew is liable to do, he shortened it by twisting one end prior to bracing it.

Before shooting he invariably looked over each arrow, straightened it in his hands or by his teeth, re-arranged its feathers, and saw that the point was properly adjusted. In fact, he gave infinite attention to detail. With him, every shot must count. Besides arrows in his quiver, he carried several ready for use under his right arm, which he kept close to his side while drawing the bow.

In all things pertaining to the handicraft of archery and the technique of shooting, he was most exacting. Neatness about his tackle, care of his equipment, deliberation and form in his shooting were typical of him; in fact, he loved his bow as he did no other of his possessions. It was his constant companion in life and he took it with him on his last long journey.

IV. Archery in General

Our experience with Ishi waked the love of archery in us, that impulse which lies dormant in the heart of every Anglo-Saxon. For it is a strange thing that all the men who have centered about this renaissance in shooting the bow, in our immediate locality, are of English ancestry. Their names betray them. Many have come and watched and shot a little, and gone away; but these have stayed to hunt.

From shooting the bow Indian fashion, I turned to the study of its history, and soon found that the English were its greatest masters. In them archery reached its high tide; after them its glory passed.

But the earliest evidence of the use of the bow is found in the existence of arrowheads assigned to the third interglacial period, nearly 50,000 years ago.

That man had material culture prior to this epoch, there is no doubt, and the use of the bow with arrows of less complicated structure must have preceded this period.

All races and nations at one time or another have used the bow. Even the Australian aborigine, who is supposed to have been too low in mental development to have understood the principles of archery, used a miniature bow and poisoned arrow in shooting game. In the magnificent collection of Joseph Jessop of San Diego, California, I saw one of these little bows scarcely more than a foot long. The arrows, he stated, the natives carried in the hair of their heads.

Those who are interested in the archaeology of the bow should read the volume on archery of the Badminton Library by Longmans.

Various peoples have excelled in shooting, notably the Japanese, the Turks, the Scythians, and the English. Others have not been suited by temperament to use the bow. The Latins, the Peruvians, and the Irish seem never to have been toxophilites. The famous long bow of Merrie Old England was brought there by the Normans, who inherited it from the Norsemen settled along the Rhine. Here grew the best yew trees in days gone by, and this, doubtless, was a strong determining factor in the superior development of their archery.

Before the battle of Hastings, the Saxons used the short, weak weapon common to all primitive people. The conquered Saxon, deprived of all arms such as the boar-spear, the sword, the ax, and the dagger, naturally turned to the bow because he could make this himself, and he copied the Norman long bow.

Although the first game preserves in England were established by William the Conqueror at this time, the Saxon was permitted to shoot birds and small beasts in his fields and therefore was allowed to use a blunt arrow, headed with a lead tip or pilum, hence our term pile, or target point. If found with a sharp arrowhead, the so-called broad-head used for killing the king's deer, he was promptly hanged. The evidence against such a poacher was summed up thus in the old legend:

Dog draw, stable stand

Back berond, bloody hand.

One found following a questing hound, posed in the stand of an archer, carrying game on his back, or with the evidence of recent butchery on his hands, was hanged to the nearest tree by his own bowstring.

It was under these circumstances that outlawry took the form of deer killing and robust archery became the national sport. In these days the legendary hero, the demi-myth, Robin Hood, was born. What boy has not thrilled at the tales of Greenwood men, the well-sped shaft, the arrow's low whispering flight, and the willow wand split at a hundred paces?

Every boy goes through a period of barbarism, just as the nations have passed, and during that age he is stirred by the call of the bow. I, too, shot the toy bows of boyhood; shot with Indian youths in the Army posts of Texas and Arizona. We played the impromptu pageants of Robin Hood, manufactured our own tackle, and carried it about with unfailing fidelity; hunted small birds and rabbits, and were the usual savages of that age.

But when it comes to the legends of the bow, the records of these past glories are so vague that we must accept them as a tale oft told; it grows with the telling.

It seems that distances were measured in feet, paces, yards, or rods with blithe indifference, and the narrator added to them at will. Robin is supposed to have shot a mile, and his bow was so long and so strong no man could draw it. In sooth, he was a mighty hero, and yet the ballads refer to him as a "slight fellow," even "a bag of bones." As a youth he slew the king's deer at three hundred yards, a right goodly shot! And no doubt it was.

Of all the bows of the days when archery was in flower, only two remain. These are unfinished staves found in the ship Mary Rose, sunk off the coast of Albion in 1545. This vessel having been raised from the bottom of the ocean in 1841, the staves were recovered and are now in the Tower of London. They are six feet, four and three-quarters inches long, one and one-half inches across the handle, one and one-quarter inches thick, and proportionately large throughout. The dimensions are recorded in Badminton. Of course, they never have been tested for strength, but it has been estimated at 100 pounds.

Determined to duplicate these old bows, I selected a very fine grained stave of seasoned yew and made an exact duplicate, according to the recorded measurements.

This bow, when drawn the standard arrow length of twenty-eight inches, weighed sixty-five pounds and shot a light flight arrow two hundred and twenty-five yards. When drawn thirty-six inches, it weighed seventy-six pounds and shot a flight arrow two hundred and fifty-six yards. From this it would seem that even though these ancient staves appear to be almost too powerful for a modern man to draw, they not only are well within our command, but do not shoot a mile.

The greatest distance shot by a modern archer was made by Ingo Simon, using a Turkish composite bow, in France in 1913. The measured distance was four hundred and fifty-nine yards and eight inches. That is very near the limit of this type of bow and far beyond the possibilities of the yew long bow. But the long bow is capable of shooting heavier shafts and shooting them harder.

Since archery is fast disappearing from the land, and the material for study will soon become extinct, I have undertaken to record the strength and shooting qualities of a representative number of the available bows in preservation, together with the power of penetration of arrows.

To do this, through the mediation of the Department of Anthropology of the University of California, I have had access to the best collection of bows in America. Thousands of weapons were at my disposal in various museums, and from these I selected the best preserved and strongest to shoot.

The formal report of these experiments is in the publications of the University, and here 'tis only necessary to mention a few of the findings.

In testing the function of these bows and their ability to shoot, a bamboo flight arrow made by Ishi was used as the standard. It was thirty inches long, weighed three hundred and ten grains, and had very low cropped feathers. It carried universally better than all other arrows tested, and flew twenty per cent farther than the best English flight arrows.

To make sure that no element of personal weakness entered into the test, I had these bows shot by Mr. Compton, a very powerful man and one used to the bow for thirty years. I myself could draw them all, and checked up the results.

It is axiomatic that the weight and the cast of a bow are criteria of its value as a weapon in war or in the chase. Weight, as used by an archer, means the pull of a bow when full drawn, recorded in pounds.

The following is a partial list of those weighed and shot. They are, of course, all genuine bows and represent the strongest. Each was shot at least six times over a carefully measured course and the greatest flight recorded. All flights were made at an elevation of forty-five degrees and the greatest possible draw was given each shot. In fact we spared no bows because of their age, and consequently broke two in the testing.

| Weight | Distance Shot | |

| Alaskan | 80 pounds | 180 yards |

| Apache | 28 " | 120 " |

| Blackfoot | 45 " | 145 " |

| Cheyenne | 65 " | 156 " |

| Cree | 38 " | 150 " |

| Esquimaux | 80 " | 200 " |

| Hupa | 40 " | 148 " |

| Luiseno | 48 " | 125 " |

| Navajo | 45 " | 150 " |

| Mojave | 40 " | 110 " |

| Osage | 40 " | 92 " |

| Sioux | 45 " | 165 " |

| Tomawata | 40 " | 148 " |

| Yurok | 30 " | 140 " |

| Yukon | 60 " | 125 " |

| Yaki | 70 " | 210 " |

| Yana | 48 " | 205 " |

The list of foreign bows is as follows:

| Weight | Distance Shot | |

| Paraguay | 60 pounds | 170 yards |

| Polynesian | 49 " | 172 " |

| Nigrito | 56 " | 176 " |

| Andaman Islands | 45 " | 142 " |

| Japanese | 48 " | 175 " |

| Africa | 54 " | 107 " |

| Tartar | 98 " | 175 " |

| South American | 50 " | 98 " |

| Igorrote | 26 " | 100 " |

| Solomon Islands | 56 " | 148 " |

| English target bow (imported) | 48 " | 220 " |

| English yew flight bow | 65 " | 300 " |

| Old English hunting bow | 75 " | 250 " |

It will be seen from these tests that no existing aboriginal bow is very powerful when compared with those in use in the days of robust archery in old England. The greatest disappointment was in the Tartar bow which was brought expressly from Shansi, China, by my brother, Col. B. H. Pope. With this powerful weapon I expected to shoot a quarter of a mile; but with all its dreadful strength, its cast was slow and cumbersome. The arrow that came with it, a miniature javelin thirty-eight inches long, could only be projected one hundred and ten yards. In making these shots both hands and feet were used to draw the bow. A special flight arrow thirty-six inches long was used in the test, but with hardly any increase of distance gained.

After much experimenting and research into the literature,[5] I constructed two horn composite bows, such as were used by the Turks and Egyptians. They were perfect in action, the larger one weighing eighty-five pounds. With this I hoped to establish a record, but after many attempts my best flight was two hundred and ninety-one yards. This weapon, being only four feet long, would make an excellent buffalo bow to be used on horseback.

In shooting for distance, of course, a very light missile is used, and nothing but empirical tests can determine the shape, size, and weight that suits each bow. Consequently, we use hundreds of arrows to find the best. For more than seven years these experiments have continued, and at this stage of our progress the best flight arrow is made of Japanese bamboo five-sixteenths of an inch in diameter, having a foreshaft of birch the same diameter and four inches long. The nock is a boxwood plug inserted in the rear end, both joints being bound with silk floss and shellacked. The point is the copper nickel jacket of the present U. S. Army rifle bullet, of conical shape. The feathers are parabolic, three-quarters of an inch long by one-quarter high, three in number, set one inch from the end, and come from the wing of an owl. The whole arrow is thirty inches long, weighs three hundred and twenty grains, and is very rigid.

With this I have shot three hundred and one yards with a moderate wind at my back, using a Paraguay ironwood bow five feet two inches long, backed with hickory and weighing sixty pounds. This is my best flight shot.

It is not advisable here to go further into this subject; let it stand that the English yew long bow is the highest type of artillery in the world.

Although the composite Turkish bows can shoot the farthest, it is only with very light arrows; they are incapable of projecting heavier shafts to the extent of the yew long bow, that is, they can transmit velocity but not momentum; they have resiliency, but not power.

Besides these experiments with bows, many tests were made of the flight and penetration of arrows. A few of the pertinent observations are here noted.

A light arrow from a heavy bow, say a sixty-five pound yew bow, travels at an initial velocity of one hundred and fifty feet per second, as determined by a stopwatch.

Shooting at one hundred yards, such an arrow is discharged at an angle of eight degrees, and describes a parabola twelve to fifteen feet high at its crest. Its time in transit is of approximately two and one-fifth seconds.

Shooting straight up, such an arrow goes about three hundred and fifty feet high, and requires eight seconds for the round trip. This test was made by shooting arrows over very tall sequoia trees, of known height.

The striking force of a one-ounce arrow shot from a seventy-five pound bow at ten yards, is twenty-five foot pounds. This test is made by shooting at a cake of paraffin and comparing the penetration with that made by falling weights. Such a striking force is, of course, insignificant when compared with that of a modern bullet, viz., three thousand foot pounds. Yet the damage done by an arrow armed with a sharp steel broad-head is often greater than that done by a bullet, as we shall see later on.

A standard English target arrow rotates during flight six complete revolutions every twenty yards, or approximately fifteen times a second. Heavy hunting shafts turn more slowly. This was ascertained by shooting two arrows at once from the same bow, their shafts being connected by a silk thread, so that one paid off as the other wound up the thread. The number of complete loops, of course, indicated the number of revolutions. A sand-bank makes a good butt to catch them. In rotating, much depends on the size and shape of the feather.

Shooting a blunt arrow from a seventy-five pound bow at a white pine board an inch thick, the shaft will often go completely through it. A broad hunting head will penetrate two or three inches, then bind. But the broad-head will go through animal tissue better, even cutting bones in two; in fact, such an arrow will go completely through any animal but a pachyderm.

To test a steel bodkin pointed arrow such as was used at the battle of Cressy, I borrowed a shirt of chain armor from the Museum, a beautiful specimen made in Damascus in the 15th Century. It weighed twenty-five pounds and was in perfect condition. One of the attendants in the Museum offered to put it on and allow me to shoot at him. Fortunately, I declined his proffered services and put it on a wooden box, padded with burlap to represent clothing.

Indoors at a distance of seven yards, I discharged an arrow at it with such force that sparks flew from the links of steel as from a forge. The bodkin point and shaft went through the thickest portion of the back, penetrated an inch of wood and bulged out the opposite side of the armor shirt. The attendant turned a pale green. An arrow of this type can be shot about two hundred yards, and would be deadly up to the full limit of its flight.

The question of the cutting qualities of the obsidian head as compared to those of the sharpened steel head, was answered in the following experiment:

A box was so constructed that two opposite sides were formed by fresh deer skin tacked in place. The interior of the box was filled with bovine liver. This represented animal tissue minus the bones.

At a distance of ten yards I discharged an obsidian-pointed arrow and a steel-pointed arrow from a weak bow. The two missiles were alike in size, weight, and feathering, in fact, were made by Ishi, only one had the native head and the other his modern substitute. Upon repeated trials, the steel-headed arrow uniformly penetrated a distance of twenty-two inches from the front surface of the box, while the obsidian uniformly penetrated thirty inches, or eight inches farther, approximately 25 per cent better penetration. This advantage is undoubtedly due to the concoidal edge of the flaked glass operating upon the same principle that fluted-edged bread and bandage knives cut better than ordinary knives.

In the same way we discovered that steel broad-heads sharpened by filing have a better meat-cutting edge than when ground on a stone.

In our experience with game shooting, we never could see the advantage of longitudinal grooves running down the shaft of the arrow, such as some aborigines use, supposed to promote bleeding. In the first place these marks are inadequate in depth, and secondly it is not the exterior bleeding that kills the wounded animal so much as the internal hemorrhage.

A sufficiently wide head on the arrow cuts a hole large enough to permit the escape of excess blood, and, as a matter of fact, nearly all of our shots are perforating, going completely through the body.

Conical, blunt, and bodkin points lack the power of penetration in animal tissue inherent in broad-heads; correspondingly they do less damage.

Catlin, in his book on the North American Indian, relates that the Mandans, among other tribes, practiced shooting a number of arrows in succession with such dexterity that their best archer could keep eight arrows up in the air at one time.

Will Thompson, the dean of American archery, writing in Forest and Stream of March, 1915, says very definitely that the feat of the legendary hero, Hiawatha, who is supposed to have shot so strong and far that he could shoot the tenth arrow before the first descended, is manifestly absurd. Thompson contends that no man ever has, or ever will keep more than three arrows up in the air at once.

Having read this and determined to try the experiment of dextrous shooting, I constructed a dozen light arrows having wide nocks and flattened rear ends so they might be fingered quickly. Then I devised a way of grasping a supply of ready shafts in the bow hand, and invented an arrow release in which all the fingers and thumb held the arrow on the string, yet remained entirely on the right side of it.

After quite a bit of practice in accurate, later in rapid, nocking, I succeeded in shooting seven successive arrows in the air before the first touched the ground. I used a perpendicular flight. Upon several occasions I almost accomplished eight at once. I feel that with considerable practice eight, and even more, are possible, proving again that there is an element of truth in all legends.

It has long been a bone of contention among archers which element of the yew, the sap wood or the heart, gives the greater cast. To obtain experimental evidence, I constructed two miniature bows, each twenty-two inches long, one of pure white sap wood, the other of the heart from the same stave. I made them the same size, and weighing about eight pounds when drawn eight inches.

Shooting a little arrow on these bows, the sap wood shot forty-three yards; the red wood sixty-six yards, showing the greater cast to be in the red yew.

Corroborating this, Mr. Compton relates that while working in Barnes's shop in Forest Grove, Oregon, during the last illness of that noted bowyer, he came across a laminated bow made entirely of sap wood. Barnes stated that he had constructed it at the instigation of Will Thompson. The cast of this bow was slow, flabby, and weak. As a shooting implement it was a failure.

Taking two pieces of wood, one white and one red, each twelve inches long, I placed them in a bench vise and fastened a spring scale to the top of each. Drawing the sap wood four inches from the perpendicular, it pulled eight pounds. Drawing the heart wood the same distance it pulled fourteen pounds, showing the greater strength of the latter. When drawn five inches from a straight line, the red piece broke. The sap wood could be bent at a right angle without fracture.

It is obvious from this that the sap wood excels in tensile strength the red wood in compression strength and resiliency. In fact, they are reciprocal in action. The red yew on the belly of the bow gives the energy, the sap wood preserves it from fracture. It is, in fact, equivalent to sinew backing, and though less durable, probably adds more to the cast of the bows.

In our experiments with a catgut and rawhide backing, we have not found that they add materially to the cast of a bow, only insure it against fracture. On the other hand, sap wood and hickory backing materially add to the power of the implement.

The little red yew bow used in the previous experiment was backed heavily with rawhide and catgut. It then weighed ten pounds, but only shot sixty-three yards, showing a decrease in cast. But the backing permitted its being drawn to ten inches, when it shot a distance of eighty-five yards. A draw of twelve inches fractured it across the handle.

In a similar experiment it was shown that two pieces of wood of the same size, but one being of a coarse-grained yew running sixteen lines to the inch, the other a fine-grained piece running thirty-five lines to the inch, the finer grain had the greater strength and resiliency up to the breaking point, but the yellow coarse-grained piece was more flexible and less readily broken.

The question often arises, "How would an arrow fly if the bow is held in a mechanical rest and the string released by a mechanical release?" Such an apparatus would permit of several experiments. It would answer some of the queries that naturally pass through the mind of every archer. Question 1. How accurate is the bow and arrow as a weapon of precision, or as they say in ballistics, "What is the error of dispersion?"

Question 2. What is the angle of declination to the left of the point of aim in the flight of such an arrow?

Question 3. What is the effect of placing the cock feather next the bow?

Question 4. What is the effect of shooting different arrows? How do they group? Would not such a machine give accurate data regarding the flight of new arrows and help in the selection of shafts for target shooting?

Question 5. What effect does the time of holding a bow full drawn have on the flight of an arrow?

Question 6. What is the result of changing the weight of bows when the arrows remain the same?

Therefore, we devised a rest, consisting of a post set firmly in the ground, with a rigid cross arm and a vise-like hand grip. This latter was padded thickly with rubber, so that some resiliency was permitted. The bow was fastened in this mechanical hand by sturdy set screws.

At the other end of the cross arm a hinged block was attached, from which projected two short wooden fingers, serving the exact function of the drawing hand. These were spaced so that the arrow nock fitted between them, and when the string was pulled into position and caught upon these fingers, the bow was drawn 28 inches.

We adopted a system of loading, drawing and releasing on count, so that every shot was delivered with equal time factors.

Answer 1. Using the same arrow each time, with the target set at 60 yards, we found, of course, that the arrow always flies to the left when drawn on the left side of the bow, and that the angle of divergence for a 50 pound bow and a 5 shilling English target arrow was between six and seven degrees. Using a stronger bow this angle was increased,--also that with a weaker arrow the angle was greater,--but six degrees might be designated as the normal declination.

Answer 2. Every rifle expert knows what his gun is capable of, in accuracy, and an archer should know just what to expect of an arrow under the most favorable conditions. We therefore tried shooting the same arrow over the same course with the same release, under these fairly stable conditions: The day was calm. We shot an arrow ten times in succession and all the shots centered in a six inch bull's-eye; that is, none went out of a circle of this diameter. In other words, at sixty yards a bow can shoot arrows with an error of dispersion of no more than six inches. This is surprisingly accurate for a weapon of this sort, when it is considered that the best rifles of today will average between one and a half to three inches dispersion at 100 yards.

Answer 3. Placing the cock feather next the bow diverts the arrow to the left and causes it to drop lower on the target. The group formed by six flights was fairly close and consistent.

Answer 4. Out of nine arrows tested, five consistently made a good close group and four as consistently went out. The "outs," however, were uniform in the direction and distance they took. It would be possible by this machine to select arrows that would make co-incidental patterns. It is obvious, however, that differences in individual arrows are greatly exaggerated by the apparatus, because it was quite apparent by this test that any good archer could group these hits much closer than the machine delivered them.

Answer 5. In our shooting, we universally allotted five seconds for drawing, setting and discharging. However, when this time was increased to fifteen seconds, we found that our groups averaged seven and one-half inches lower. This shows the decided loss of cast incidental to long holding of the bow.

Answer 6. Placing a 65 pound bow in the frame immediately showed increased reactions throughout. The lateral divergence in arrow flight was increased to fifteen degrees and all individual reactions were correspondingly increased. The flight of the individual arrow was less consistent, showing plainly the necessity of a proper relation in weight between the arrow and bow,--a very essential factor in accurate shooting.