Shanti Escalante-de Mattei

In Ted Kaczynski, Artists Found a Means of Exploring the Horror of Living in America Today

Over the span of nearly 20 years, Ted Kaczynski mailed out at least 16 homemade bombs, killed three people, injured 23, and avoided arrest before his brother went to the FBI with damning clues following the Washington Post’s publication of Kaczynski’s manifesto, Industrial Society and Its Future. He also inspired some of the top artists working today, whom he seemed to both enchant and repel.

Richard Prince published his memoir, in which Kaczynski attempts to show that “I am very different from the kind of person that the media portrayed with the help of my mother and brother,” insisting he was not what they always claimed him to be, “a sicko.” Julie Ault and Danh Vo are rumored to own his archive; the latter even exhibited Kaczynski’s typewriter as an artwork in his 2018 Guggenheim Museum survey. Many others paid homage to aspects of Kaczynski’s life through installations, photographs, sculptures, and more.

Following the arrest of Kaczynski, better known as the Unabomber, in 1996, artists began exploring his life and politics. Industrial Society and Its Future was particularly influential not just to artists but to environmentalists of the anarcho-primitivist bent. His manifesto was oddly prescient, outlining the risk our hyper-industrialized society posed to its environment at a time when climate change was secretly being studied by oil giants like Chevron while the public remained oblivious. He wrote of technology’s effect on society, how it prompts psychological suffering and a sense of purposelessness, before Mark Zuckerberg was even conceived.

Kaczynski, who died on Saturday at 81, has come to embody the lone wolf, made dangerous, it seems, only because he actually took the world’s issues seriously. The artists who engaged with Kaczynski were just beginning to scratch the surface of what Kaczynski has come to represent, if only because such issues as climate change, AI, and social media were themselves nascent issues at the time that these works were being made.

What these first famous works about Kaczynski did was secure him as a symbol of Americana. A closer look at these pieces reveals the very act of historicizing as it occurs.

Perhaps the best-known artwork to tap into Kaczynski’s history is Richard Barnes’s 1998 “Unabomber Cabin” series. Two years after the FBI apprehended Kaczynski, Barnes managed to persuade authorities to allow him to photograph Kaczynski’s cabin, which the authorities had lifted wholesale from the Montana mountainside and placed in a warehouse.

In Unabomber Cabin, Sacramento, CA, Barnes captured the cabin sitting in the wide expanse of a warehouse, looking like a readymade installation, the rustic, compact structure at odds with the harsh fluorescent lighting and industrial setting. In Unabomber Cabin Exhibit A, B, C, and D, the cabin floats in darkness, its front and sides exposed in each respective photograph.

Barnes then captured the cabin in the inverse: he went to Montana to capture the spot from which the cabin had been removed. Unabomber Cabin Site, Lincoln, Montana shows a wooded spot strewn with pine needles. Absurdly, a chainlink fence topped with barbed wire encloses nothing, just a bit of tall grass and a plastic chair where the cabin used to stand. Outside the chainlink perimeter is a short stack of firewood, presumably put in place by Kaczynski.

This urge to document Kaczynski’s surroundings is found again in The Unabomber’s View (2006) by photographer Alec Soth. The photo shows what appears to be a simple, bucolic scene, a bit of Montana forest, whose beautiful, indifferent landscape housed a terrorist.

Barnes wasn’t the only one fascinated by Kaczynski’s cabin, which Kaczynski built as an homage to another piece of classic American history: Henry David Thoreau’s abode on Walden Pond. Daniel Joseph Martinez also tapped into this American tradition when he created his installation The House America Built in 2004. Martinez’s cabin is split in half, tilting open from the middle like a blossoming flower. In a reversal, Martinez’s house is painted in wide horizontal planes of orange and yellow, with a green window and a periwinkle roof: all colors Martha Stewart pushed as the season’s palette from her line of interior paints.

Martinez made a connection between Stewart and Kaczynski, two Polish Americans of the same generation who went on to be arrested for crimes that represent “an implication of the normalization of politics and hyper-capitalists, even terrorist positions, within the United States itself,” Martinez told ARTnews in a 2018 profile.

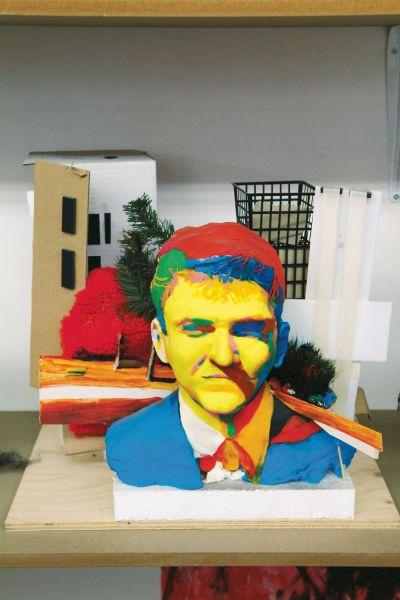

In 2008, Polish artist Robert Kuśmirowski made his own copy of a copy by remaking Kaczynski’s cabin for Unacabine. The piece was exhibited at a 2009 Palais de Tokyo exhibition called “Chasing Napoleon” that was thematically centered around 1977, the year Kaczynski began building his cabin. Kuśmirowski’s impulse to reproduce and replicate was also picked up in Ola Pehrson’s video Hunt for the Unabomber (2005), a scene-for-scene remake of a 30-minute cable documentary on the FBI’s investigation of Kaczynski. To make the work, Pehrson painstakingly built dioramas of cities and models of government buildings, painted backdrops, created plasticine busts of FBI agents and Kaczynski’s victims. Pehrson even played every talking head.

In prison, Kaczynski continued to grip the public’s imagination: people wrote him thousands of letters. He replied to many of them, and even found the time to work on his journal and a play, The Ship of Fools. The work centers around passengers on a boat who discuss and argue over the conditions on the boat but make no move to correct the course the captain is taking. Reflecting on this failure to seize control, one of the passengers says, “And then your wages, your blankets, and your right to suck cocks won’t do you any good, because we’ll all drown.”

Norwegian artist Gardar Eide Einarsson staged that play in 2006 during the run of “Chasing Napoleon” at the Palais de Tokyo. The performance is spare, the only prop a ship’s wheel, the only costume some striped shirts. Einarsson filmed the work in black and white, offering footage of actors who hardly seem to engage with one another, simply grandstanding when it’s their turn to vent their dissatisfactions. The effect is depressing, encapsulating exactly the defanged preciousness of modern discourse.

Why this urge to trace over Kaczynski, to repeat his words, to rebuild his cabin? In the wake of 9/11, terrorists took on new significance, perhaps prompting artists to look at a domestic one like Kaczynski. It’s difficult not to read these works as a means of harvesting the raw ingredients of history and distilling them into potent symbols. By now that’s all Kaczynski is, a bundle of associations that artists helped twine around our collective memory of him.

As the years passed, less work was made about this notorious figure as he aged and a new generation unfamiliar with the atmosphere of fear he created during the 1980s grew up. But like Marilyn Monroe or the Manson family, Kaczynski now belongs to the violent tapestry of American history. For better or worse, his face, his manifesto, and his cabin in the woods is likely to only increase in relevance.

The artists who earlier took up Kaczynski have in some cases furthered their famed projects. After the “Unabomber Cabin” series, Barnes would continue to photograph Kaczynski’s belongings and trace their presence, or absence, in the surrounding environment. As recently as 2015, Barnes photographed Kaczynski’s utilitarian jacket and the folksy, disturbing face covering he made for himself.

But Barnes also went back to the cabin in 2004. Press Conference with Cabin shows the press and their cameras surrounding the structure, which was moved outside to a parking lot for a media event. Amid all the commotion, the cabin sits there, solid, foreboding, its open door a portal into blackness. We are all familiar with what lies in that darknes: the undercurrent of American discontent that constantly threatens to spill out into the wider world.