Simon Critchley

Infinitely Demanding

Ethics of Commitment, Politics of Resistance

Introduction: The possibility of commitment

Demanding approval – a theory of ethical experience

Justifying reasons and exciting reasons

Kant, for example – the fact of reason

The auto-authentification of the moral law – some contemporary Kantians

The autonomy orthodoxy and the question of facticity

Dividualism – how to build an ethical subject

Alain Badiou – situated universality

Knud Ejler Løgstrup – the unfulfillable demand

Emmanuel Levinas – the split subject

Jacques Lacan – the Thingly secrecy of the neighbour

We still have a great deal to learn about the nature of the super-ego

Anarchic metapolitics – political subjectivity and political action after Marx

The names are lacking – the problem of political subjectivity

One needs to search for the struggle

Politics as interstitial distance within the state

Ethics as anarchic meta-politics

A new language of civil disobedience

Appendix: Crypto-Schmittianism – the Logic of the Political in Bush’s America

[Front Matter]

Table of Contents

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Contents

Introduction: The Possibility of Commitment

a. Nihilism – active and passive

b. Motivational deficit

c. The argument

1: Demanding approval – a theory of ethical experience

a. Ethical experience

b. Ethical subjectivity

c. Justifying reasons and exciting reasons

d. Kant, for example – the fact of reason

e. The auto-authentification of the moral law – some contemporary Kantians

f. The autonomy orthodoxy and the question of facticity

2: Dividualism – how to build an ethical subject

a. Alain Badiou – situated universality

b. Knud Ejler Løgstrup – the unfulfillable demand

c. Emmanuel Levinas – the split subject

d. Jacques Lacan – the Thingly secrecy of the neighbour

3: The problem of sublimation

a. Happiness?

b. The tragic-heroic paradigm

c. Humour

d. We still have a great deal to learn about the nature of the super-ego

e. Having a conscience

4: Anarchic metapolitics – political subjectivity and political action after Marx

a. Marx’s truth

b. Capitalism capitalizes

c. Dislocation

d. The names are lacking – the problem of political subjectivity

e. One needs to search for the struggle

f. Politics as interstitial distance within the state

g. True democracy

h. Ethics as anarchic meta-politics

i. A new language of civil disobedience

j. Dissensus and anger

k. Conclusion

Appendix: Crypto-Schmittianism – the Logic of the Political in Bush’s America

Explanatory note

Notes

[Title Page]

[Title Page]

Published by Verso 2012

First published in paperback by Verso 2008

First published by Verso 2007

© Simon Critchley 2012

All rights reserved

The moral rights of the author have been asserted

Verso

UK: 6 Meard Street, London W1F 0EG

US: 20 Jay Street, Suite 1010, Brooklyn, NY 11201

[[http://www.versobooks.com][www.versobooks.com

Verso is the imprint of New Left Books

ISBN-13: 978-1-78168-017-9

eISBN-13: 978-1-78168-029-2 (US)

eISBN-13: 978-1-78478-004-3 (UK)

British Library Cataloguing in Publication Data

A catalogue record for this book is available from the British Library

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

A catalog record for this book is available from the Library of Congress

v3.1

[Dedication]

For my mother, Sheila Patricia Critchley

Contents

Cover

Title Page

Copyright

Dedication

Introduction: The possibility of commitment

a. Nihilism – active and passive

b. Motivational deficit

c. The argument

1 Demanding approval – a theory of ethical experience

a. Ethical experience

b. Ethical subjectivity

c. Justifying reasons and exciting reasons

d. Kant, for example – the fact of reason

e. The auto-authentification of the moral law – some contemporary Kantians

f. The autonomy orthodoxy and the question of facticity

2 Dividualism – how to build an ethical subject

a. Alain Badiou – situated universality

b. Knud Ejler Løgstrup – the unfulfillable demand

c. Emmanuel Levinas – the split subject

d. Jacques Lacan – the Thingly secrecy of the neighbour

3 The problem of sublimation

a. Happiness?

b. The tragic-heroic paradigm

c. Humour

d. We still have a great deal to learn about the nature of the super-ego

e. Having a conscience

4 Anarchic metapolitics – political subjectivity and political action after Marx

a. Marx’s truth

b. Capitalism capitalizes

c. Dislocation

d. The names are lacking – the problem of political subjectivity

e. One needs to search for the struggle

f. Politics as interstitial distance within the state

g. True democracy

h. Ethics as anarchic meta-politics

i. A new language of civil disobedience

j. Dissensus and anger

k. Conclusion

Appendix: Crypto-Schmittianism – the Logic of the Political in Bush’s America

Explanatory note

Notes

Introduction: The possibility of commitment

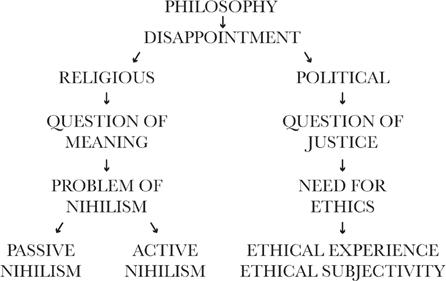

Philosophy does not begin in an experience of wonder, as ancient tradition contends, but rather, I think, with the indeterminate but palpable sense that something desired has not been fulfilled, that a fantastic effort has failed. Philosophy begins in disappointment. Although there might well be precursors, I see this as a specifically modern conception of philosophy. To give it a name and a date, one could say that it is a conception of philosophy that follows from Kant’s Copernican turn at the end of the eighteenth century. The great metaphysical dream of the soul moving frictionless towards knowledge of itself, things-in-themselves and God is just that, a dream. Absolute knowledge or a direct ontology of things as they are is decisively beyond the ken of fallible, finite creatures like us. Human beings are exceedingly limited creatures, a mere vapour or virus can destroy us. The Kantian revolution in philosophy is a lesson in limitation. As Pascal said, we are the weakest reed in nature and this fact requires an acknowledgement that is very reluctantly given. Our culture is endlessly beset with Promethean myths of the overcoming of the human condition, whether through the fantasy of artificial intelligence, contemporary delusions about robotics, cloning and genetic manipulation or simply through cryogenics and cosmetic surgery. We seem to have enormous difficulty in accepting our limitedness, our finiteness, and this failure is a cause of much tragedy.

One could give an entire taxonomy of disappointment, but the two forms that concern me most urgently are religious and political. These forms of disappointment are not entirely separable and continually leak into one another. Indeed, we will see how ethical and religious categories are rightly difficult to distinguish at times, and in my discussions of ethics I will often have recourse to religious traditions. In religious disappointment, that which is desired but lacking is an experience of faith. That is, faith in some transcendent god, god-equivalent or, indeed, gods. Philosophy in the experience of religious disappointment is godless, but it is an uneasy godlessness with a religious memory and within a religious archive.

The experience of religious disappointment provokes the following, potentially abyssal question: if the legitimating theological structures and religious belief systems in which people like us believed are no longer believable, if, to coin a phrase, God is dead, then what becomes of the question of the meaning of life? It is this question that provokes the visit of what Nietzsche refers to as the uncanniest of guests: nihilism. Nihilism is the breakdown of the order of meaning, where all that we previously imagined as a divine, transcendent basis for moral valuation has become meaningless. Nihilism is this declaration of meaninglessness, a sense of indifference, directionlessness or, at its worst, despair that can flood into all areas of life. For some, this is the defining experience of youth – witness the deaths of numerous young romantics, whether Keats, Shelley, Sid Vicious or Kurt Cobain, and their numbers continue to multiply – for others it lasts a whole lifetime. The philosophical task set by Nietzsche and followed by many others in the Continental tradition is how to respond to nihilism, or better, how to resist nihilism. Philosophical activity, by which I mean the free movement of thought and critical reflection, is defined by militant resistance to nihilism. That is, philosophy is defined by the thinking through of the fact that the basis of meaning has become meaningless. Our devalued values require what Nietzsche calls revaluation or trans-valuation. All the difficulty here consists in thinking through the question of meaning without bewitching ourselves with new and exotic forms of meaning, with imported brands of existential balm, the sort of thing that Nietzsche called ‘European Buddhism’ – although there is a lot ‘American Buddhism’ around too.

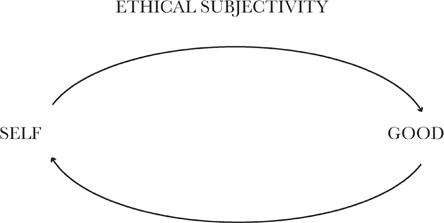

However, this book will be concerned with the other major form of disappointment, political disappointment. In the latter, the sense of something lacking or failing arises from the realization that we inhabit a violently unjust world, a world defined by the horror of war, a world where, as Dostoevsky says, blood is being spilt in the merriest way, as if it were champagne. Such an experience of disappointment is acutely tangible at the present time, with the corrosion of established political structures and an unending war on terror where the moods of Western populations are controlled through a politics of fear managed by the constant threat of external attack. As I try to show in the Appendix to this book, this situation is far from novel and might be said to be definitional of politics from antiquity to early and considerably later modernity. My point is that if the present time is defined by a state of war, then this experience of political disappointment provokes the question of justice: what might justice be in a violently unjust world? It is this question that provokes the need for an ethics or what others might call normative principles that might enable us to face and face down the present political situation. The main task of this book is responding to that need by offering a theory of ethical experience and subjectivity that will lead to an infinitely demanding ethics of commitment and politics of resistance (See Figure 1).

Nihilism – active and passive

Yet, the latter is not the only option offered up by the present situation. This is why I mentioned religious disappointment and the problem of nihilism. Keeping that problem in mind, the present situation can provoke coherent, but in my view misguided, responses that we might describe as ‘passive nihilism’ and ‘active nihilism’. The passive nihilist looks at the world from a certain distance, and finds it meaningless. He is scornful of the pretensions of liberal humanism with its metaphysical faith in progress, improvement and the perfectibility of humankind, beliefs that he claims are held with the same dogmatic assurance that Christianity was held in Europe until the late eighteenth century. The passive nihilist concludes that we are simply animals, and rather nasty aggressive primates at that, what we might call homo rapiens, rapacious animals. Rather than acting in the world and trying to transform it, the passive nihilist simply focuses on himself and his particular pleasures and projects for perfecting himself, whether through discovering the inner child, manipulating pyramids, writing pessimistic-sounding literary essays, taking up yoga, bird-watching or botany, as was the case with the aged Rousseau. In the face of the increasing brutality of reality, the passive nihilist tries to achieve a mystical stillness, calm contemplation: ‘European Buddhism’. In a world that is all too rapidly blowing itself to pieces, the passive nihilist closes his eyes and makes himself into an island.[1]

The active nihilist also finds everything meaningless, but instead of sitting back and contemplating, he tries to destroy this world and bring another into being. The history of active nihilism is fascinating and a consideration of it would take us back into various utopian, radical political and even terrorist groups. We might begin this history with Charles Fourier’s utopian phalansteries of free love and leisure, before moving on to late nineteenth-century anarchism in Russia and elsewhere, through to the Promethean activism of Lenin’s Bolshevism, Marinetti’s Futurism, Maoism, Debord’s Situationism, the Red Army Fraction in Germany, the Red Brigades in Italy, the Angry Brigade in England, the Weather Underground in the USA, without forgetting the sweet naivety of the Symbionese Liberation Army.

At the present time, however, the quintessence of active nihilism is al-Qaeda, this covert and utterly postmodern, rhizomatic quasi-corporation outside of any state control. Al-Qaeda uses the technological resources of capitalist globalization – elaborate and coded forms of communication, the speed and fluidity of financial transactions, and obviously transportation – against that globalization. The explicit aim of the destruction of the World Trade Center was the initiation of a new series of religious wars. The sad truth is that this aim has been hugely successful. The legitimating logic of al-Qaeda is that the modern world, the world of capitalism, liberal democracy and secular humanism, is meaningless and that the only way to remake meaning is through acts of spectacular destruction, acts which it is no exaggeration to say have redefined the contemporary political situation and made the pre-9/11 world seem remote and oddly quaint. We are living through a chronic re-theologization of politics.

In my view, one should approach al-Qaeda with the words and actions of bin Laden resonating against those of Lenin, Blanqui, Mao, Baader-Meinhof, and Durruti. The more one learns about figures like Sayyid Qutb, who was murdered by the Nasser government in Egypt in 1966 after a period of imprisonment when he wrote many texts that would influence intellectuals like al-Zawahiri, Osama bin Laden’s mentor, the more one sees the connection between Jihadist revolutionary Islam and more classical forms of extreme revolutionary vanguardism.[2] Although bin Laden’s language is always couched in terms of opposing the ‘Zionist – Crusader chain of evil’ and ‘global unbelief’, the political logic of Jihadism is an active nihilist revolutionary vanguardism which is far more deeply committed to martyrdom and the rewards of the hereafter than the establishment of any positive social programme. In the savage intensity of his piety, Osama bin Laden is a quasi-kissing cousin of Turgenev’s Bazarov.[3]

Motivational deficit

Although they are opposed, both active and passive nihilism are Siamese twins of sorts, as they both agree on the meaninglessness of reality, or rather its essential unreality, which inspires either passive withdrawal or violent destruction. I will be following a different path. It seems to me that that we have to think through and think out of the situation in which we find ourselves. We have to resist and reject the temptation of nihilism and face up to the hard reality of the world. What does that reality teach us? It shows violent injustice here and around the world; it shows growing social and economic inequalities here and around the world; it shows that the difference between what goes on here and around the world is increasingly fatuous. It shows the populations of the well-fed West governed by fear of outsiders, whose current names are ‘terrorist’, ‘immigrant’, ‘refugee’ or ‘asylum seeker’. It shows populations turning inward towards some reactionary and xenophobic conception of their purported identity, something which is happening in a particularly frightening manner all across Europe at present. It shows that because of an excessive diet of sleaze, deception, complacency and corruption liberal democracy is not in the best of health. It shows, in my parlance, massive political disappointment.

It is here that we have to recognize the force of al-Qaeda’s position and their diagnosis of the present. In a word, the institutions of secular liberal democracy simply do not sufficiently motivate their citizenry. On the contrary, at this point in time, the political institutions of the Western democracies appear strangely demotivating. There is increasing talk of a democratic deficit, a feeling of the irrelevance of traditional electoral politics to the lives of citizens, and an uncoupling of civil society from the state, at the same time as the state seeks to extend ever-increasing powers of surveillance and control into all areas of civil society. I think it might be claimed that there is a motivational deficit at the heart of liberal democratic life, where citizens experience the governmental norms that rule contemporary society as externally binding but not internally compelling.[4] They are simply not part of our mindset, the dispositions of our subjectivity. If secular liberal democracy doesn’t motivate subjects sufficiently, then – returning to active and passive nihilism – what seems to motivate subjects are frameworks of belief that call that secular project into question. Whatever one may think about it, one has to recognize that there is something powerfully motivating about the Islamist or Jihadist worldview, or indeed its Christian fundamentalist obverse. Yet, the source of that motivation is metaphysical or theological. What is most depressing about the many depressing features of the current US administration is the sort of metaphysical or theological symmetry between George W. Bush and Osama bin Laden. This is what I mean when I say that we have entered a period of new religious war.

The hypothesis here is that there is a motivational deficit at the heart of secular liberal democracy and that what unites active and passive nihilists is a metaphysical or theological critique of secular democracy, whether in terms of a Jihadist or Christian fundamentalist activism or a Buddhistic passivity. Now, crucially, this motivational deficit is also a moral deficit, a lack at the heart of democratic life that is intimately bound up with the felt inadequacy of official secular conceptions of morality. Indeed, following Jay Bernstein here, one might go further and argue that modernity itself has had the effect of generating a motivational deficit in morality that undermines the possibility of ethical secularism.[5] I am not so sure I want to nail my colours to the mast of a defence of secularism, but it brings me to the premise behind the opening chapters of this book. What is required, in my view, is a conception of ethics that begins by accepting the motivational deficit in the institutions of liberal democracy, but without embracing either passive or active nihilism, although each of these positions represents a potent temptation: the sense that the world is irreparably flawed in a way that behoves either passive withdrawal or active destruction. What is lacking at the present time of massive political disappointment is a motivating, empowering conception of ethics that can face and face down the drift of the present, an ethics that is able to respond to and resist the political situation in which we find ourselves. This brings me to my initial question: if we are going to stand a chance of constructing an ethics that empowers subjects to political action, a motivating ethics, we require some sort of answer to what I see as the basic question of morality. It is to this that I would now like to turn.

The argument

How does a self bind itself to whatever it determines as its good? In my view, this is the fundamental question of ethics. To answer it we require a description and explanation of the subjective commitment to ethical action. My claim will be that all questions of normative justification, whether with reference to theories of justice, rights, duties, obligations or whatever, should be referred to what I call ‘ethical experience’. Ethical experience elicits the core structure of moral selfhood, what we might think of as the existential matrix of ethics. As such, and this is what really interests me, ethical experience furnishes an account of the motivational force to act morally, of that by virtue of which a self decides to pledge itself to some conception of the good. My polemical contention is that without a plausible account of motivational force, that is, without a conception of the ethical subject, moral reflection is reduced to the empty manipulation of the standard justificatory frameworks: deontology, utilitarianism and virtue ethics.

The initial task of Chapter 1 is twofold: first, to outline a theory of ethical experience based on the concepts of approval and demand; and second, to show how this theory presupposes a model of ethical subjectivity. I then go on to explore this notion of ethical experience with particular attention to Kant’s notion of practical reason and how that notion is picked up and adapted in an influential way by contemporary Kantians, such as Rawls, Korsgaard and Habermas. The central focus of the discussion of Kant will be the peculiar doctrine of the ‘fact of reason’ which attempts to unify the justification of moral norms on the basis of universality with the motivation to act on those norms.

My overall argument can be broken down into meta-ethical and normative parts. I understand meta-ethics to be inquiry into the nature of ethics and what makes ethics the thing that it is, i.e. what makes ethics ethical; I understand normative ethics to be the recommendation of a specific conception of morality. On the basis of my meta-ethical argument about ethical experience in Chapter 1 and illustrated with the example of Kant, I will go in on in Chapters 2 and 3 to construct a normative model of ethical subjectivity. I will recommend this model most warmly, although I don’t think it is the business of moral argument to be able to provide watertight proofs for its propositions. Ethical argument is neither like logic, which is deductively true, nor science, which is inductively true. There is a point at which the rationality of moral argumentation gives way to moral recommendation, even exhortation, an appeal to the individual reader from an individual writer.

The central philosophical task in my approach to ethics is developing a theory of ethical subjectivity. A subject is the name for the way in which a self binds itself to some conception of the good and shapes its subjectivity in relation to that good. To be clear, I am not making the questionable claim that it is the job of philosophers to manufacture moral selves. They exist already as the living, breathing products of education and socialization. What I am seeking to offer is a model of ethical subjectivity with some normative force that might both describe and deepen the activity of those living, breathing moral selves. I construct a model of ethical subjectivity by borrowing three concepts from three thinkers. From Alain Badiou, I borrow the idea of fidelity to the event as the central ethical experience, which I link to the neglected and much-maligned concept of commitment. From the little-known Danish theologian Knud Ejler Løgstrup, I take the idea of the ethical demand, which is a one-sided, radical and – crucially, for me – unfulfillable demand. From Emmanuel Levinas, I take the idea that the unfulfillability of the ethical demand, what he sometimes calls ‘the curvature of intersubjective space’, is internal to subjectivity. The thought here is that the Levinasian ethical subject is a subject defined by the experience of an internalized demand that it can never meet, a demand that exceeds it, what he calls infinite responsibility. For Levinas, the experience of the demand is affective and the affect that constitutes the ethical subject is trauma. Following this clue, I seek to reconstruct the basic operation of Levinas’s work in psychoanalytic terms, borrowing the notion of trauma in the later Freud. This means that the ethical subject is, in my parlance, hetero-affectively constituted. It is a split subject divided between itself and a demand that it cannot meet, a demand that makes it the subject that it is, but which it cannot entirely fulfill. The sovereignty of my autonomy is always usurped by the heteronomous experience of the other’s demand. The ethical subject is a dividual.

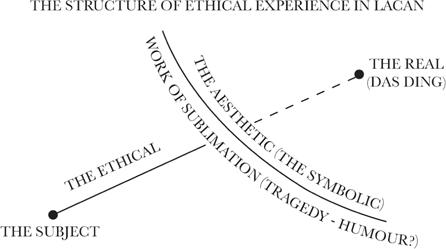

In Chapter 3, I show how this conception of the ethical subject runs the risk of chronically overloading – indeed masochistically persecuting – the self with responsibility in a way that calls for an experience of what psychoanalysts call sublimation. Drawing heavily from Lacan, the problem of sublimation will take us into psychoanalytic discussions of art and, more specifically, tragedy. I argue that the psychoanalytic discourse on sublimation is hostage to a ‘tragic-heroic paradigm’ that extends back through Heidegger to German Idealism. Against this paradigm, I will show how humour can be conceived as a practice of minimal sublimation that both maintains and alleviates the division of the ethical subject.

So, on my view, the ethical subject is defined by commitment or fidelity to an unfulfillable demand, a demand that is internalized subjectively and which divides subjectivity. Now, such a divided subjectivity is, I would argue, the experience of conscience, which is a concept that I want to place back at the heart of ethics. Despite Nietzschean claims about conscience culminating in self-hatred or Freudian claims about the cruelty of the super-ego, I am proposing an ethics of discomfort, a hyperbolic ethics based on the internalization of an unfulfillable ethical demand. Such a conscience is not, as Luther puts it, the work of God in the heart of man, but rather the work of ourselves upon ourselves. Such formulations bring Foucault’s late work to mind. But I do not understand this work of the self upon itself in Foucault’s sense, which always seems to be orientated around practices of self-mastery, what he calls ‘care for the self as a practice of freedom’.[6] On the contrary, for me, the experience of conscience is that of an essentially divided self, an originally inauthentic humorous self that can never attain the autarchy of self-mastery.

The question then becomes, and this is the theme of the final chapter: what is the link between conscience and political action? I pursue this through a reading of Marx, particularly the early Marx and more particularly still the figure of what he calls ‘true democracy’ in his early critique of Hegel. I see this figure as a clue for a thinking of the political in Marx’s work against the tendency towards economistic reductionism that was emphasized by Engels and became an article of faith for the Marxism of the Second International. My use of Marx is not scholarly or philological, but diagnostic. I am interested in his work because some of his analyses and concepts tell us a good deal about who we are, where we are, and how we might change who and where we are. This chapter turns around, to coin a phrase, what is living and what is dead in Marx’s work. On the one hand, I defend Marx’s diagnosis of capitalism and argue that his socio-economic insights have become more plausible in the face of what we all too glibly call globalization. Yet, on the other hand, I criticize the belief that the development of capitalism leads ineluctably to the simplification of the class structure into the opposed poles of bourgeoisie and proletariat, where the latter becomes the political subject of revolutionary communist praxis. Yet, if the proletariat is no longer the revolutionary subject, then this raises a deep question as to the nature of political subjectivity. After a discussion of the formation of political subjectivity that draws on Gramsci’s concept of hegemony and Ernesto Laclau’s recovery and elaboration of that concept, I go on to consider the possibility of political organization at the present time. In particular, I consider the meaning that can be given to figures like association and coalition in the face of the radical dislocations of global capitalism. I discuss the politics of indigenous identity as a powerful example of the invention of a new political subject, before moving on to the spectacular tactical politics of contemporary anarchism, which I think has forged a new language of civil disobedience.

Circling back to the main argument of the book, I conclude by arguing that at the heart of a radical politics there has to be what I call a meta-political ethical moment that provides the motivational force or propulsion into political action. If ethics without politics is empty, then politics without ethics is blind. Taking my cue from a heterodox reading of Levinas, I claim that this meta-political moment is anarchic, where ethics is the disturbance of the political status quo. Ethics is anarchic meta-politics, it is the continual questioning from below of any attempt to impose order from above. On this view, politics is the creation of interstitial distance within the state, the invention of new political subjectivities. Politics, I argue, cannot be confined to the activity of government that maintains order, pacification and security while constantly aiming at consensus. On the contrary, politics is the manifestation of dissensus, the cultivation of an anarchic multiplicity that calls into question the authority and legitimacy of the state. It is in relation to such a multiplicity that we may begin to restore some dignity to the dreadfully devalued discourse of democracy.

Demanding approval – a theory of ethical experience

Ethical Experience

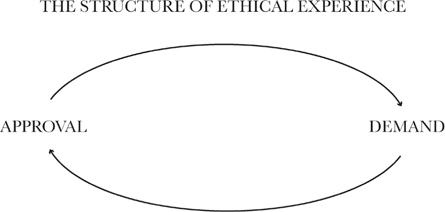

What do I mean by ethical experience? I would like to begin by trying to pick out the formal structure of ethical experience, or what, with Dieter Henrich, we can call the grammar of the concept of moral insight.[7] Firstly, with the word ‘experience’ in the ethical domain I do not mean a passive display of externally received images in the theatre of consciousness. Experience is not sheer passivity. Rather, ethical experience is an activity whereby new objects emerge for a subject involved in the process of their creation. This distinction between passive and active experience broadly follows that between Erlebnis and Erfahrung in Hegel, where the latter suggests the ongoing, processual character of experience. Ethical experience is activity, the activity of the subject, even when that activity is the receptivity to the other’s claim upon me – it is an active receptivity.

In my view, ethical experience begins with the experience of a demand to which I give my approval. There are two key components to ethical experience: approval and demand (See Figure 2). Let me begin by unpacking the notion of approval. I claim that there can be no sense of the good – however that is filled out at the level of content, and I understand it for the moment in an entirely formal and empty manner – without an act of approval, affirmation or approbation. That is, the ethical statement ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’ differs from the epistemic claim that ‘I am now seated in a chair’. Why? Because my ethical statement implies an approval of the activity of loving one’s neighbour, whereas I can be quite indifferent to the chair I am sitting on. If I say, to use a less common moral example, that ‘it would be good for parrots to receive the right to vote in elections’, then my saying this implies that I approve of this development.

However, this is not to say that approval is absent from epistemic claims or factual statements. One might legitimately object that if I say ‘there is a large portion of baltic herring on the table’, then my saying this implies a tacit approval of that fact, for I am particularly partial to the aforementioned herring. Alternatively, if I say ‘there is a dead rat in my fridge’, or, with Peter Sellars’s Inspector Clouseau that, ‘there is a bomb in my room’, then my factual statements imply strong disapproval, a disapproval, moreover, bordering on the moral assertion that it is not good for me to have a rat in my fridge or a bomb in my room. On this view, the difference between factual and moral statements with respect to approval is a difference of degree and not a difference of kind. My point is simply that there is a difference of degree and that moral statements imply strong approval or disapproval of the states of affairs under discussion, e.g. ‘war is always wrong!’ or ‘evil must not be appeased but attacked!’; ‘abortion is murder!’ or ‘every woman should have the right to choose!’; ‘Famine relief is essential!’ or ‘charity begins at home!’ Both factual and moral statements imply an experience of approval and the difference between them might be said to consist in the strength of that approval, ranging from a more or less indifferent assent or neutral acquiescence to an existential affirmation or commitment that leads to action.

However, although the good only comes into view through approval, it is not good by virtue of approval. That approval is an approval of something, namely a demand that demands approval. In my example, the approval of parrots receiving the right to vote is related to the fact that – at least in my singular moral imagination – parrots make a certain demand, namely the demand for political representation. Ethical experience is, first and foremost, the approval of a demand, a demand that demands approval. As is suggested by Figure 2, ethical experience has to be circular, although hopefully only virtuously so. As Heidegger famously shows against the accusation of the circularity of Cartesian reasoning, not all circles are vicious.

Leaving parrots to one side, and turning to the history of philosophy and religion, we can think about how this formal concept of demand can be filled out with various contents. Here is a list of demands for approval that can be inserted on the right side of Figure 2: Mosaic Law in the Bible, the Good beyond Being in Plato, the resurrected Christ in Paul and Augustine, the Good as the goal of desire for Aquinas, the practical ideal of generosity for Descartes, the experience of benevolence for Hutcheson, and of sympathy for Adam Smith and Hume, the greatest happiness of the greatest number for Bentham and Mill, the moral law in Kant, practical faith as the goal of subjective striving in Fichte, the abyssal intuition of freedom in Schelling, the creature’s feeling of absolute dependency on a creator in Schleiermacher, pity for the suffering of one’s fellow human beings in Rousseau or for all creatures in Schopenhauer, the thought of eternal return in Nietzsche, the ethico-teleological idea in the Kantian sense for Husserl, the call of conscience in Heidegger, the relation to the Thou in Buber, the claim of the non-identical in Adorno, etc., etc. This list might be extended.

The point is that each of these positions is the expression of a demand to which the self gives its approval, and that this structure of demand and approval gives the shape of ethical experience. The essential feature of ethical experience is that the subject of the demand – the moral self – affirms that demand, assents to finding it good, binds itself to that good and shapes its subjectivity in relation to that good. We will extend this very short history of ethics with the example of Kant and some contemporary Kantians and post-Kantians, but note that my little list has some big gaps, some of which will be discussed presently.

What I called above the virtuous circularity of ethical experience raises the following question: which comes first, demand or approval? Prima facie, one is perhaps inclined to say that the demand comes first; that is, without some sort of demand there is nothing to approve. This would appear to be true experientially. Let me take two examples: (i) Bob Geldof, London-based Irish rockstar turned activist and philanthropist, and (ii) the resurrection of Christ. In late autumn 1984, Bob Geldof experienced the demand of Ethiopian famine victims during an enormously distressing BBC newscast. Approving of this demand, he became subjectively committed to doing something to alleviate their plight, and thus the Band-Aid and Live-Aid projects were born. Much money was raised, much good was done, and Bob eventually became Sir Bob. Indeed, an even more dreadful version of the Band-Aid single was released late in 2004 and outsold all other songs on the UK Christmas market, and the twentieth anniversary of Live-Aid was marked with ‘Make Poverty History’ concerts in July 2005 which were rather neatly coopted by the vapid universalism of Blair’s New Labour. QED for the priority of demand over approval, it would seem. However, another person watching the same newscast as Sir Bob in 1984 might have experienced no demand at all. Or indeed, in the case of the immoralist whom we shall meet in a moment, they might have approved of the demand, but nonetheless done nothing about it.

If this seems to be an argument from moral callousness, then consider another example, that of Christ’s resurrection. To the believer, the resurrection is a fact, a fact which places a demand upon the self, and it is in relation to that demand that Christian subjectivity takes shape. Yet, to the non-believer there is just an empty tomb, the grave of the troublesome radical rabbi Jesus executed by the occupying Roman authorities with the connivance of the Pharisees. The point is that the demand is not somehow objectively given in the state of affairs. Rather, the demand is only felt as a demand for the self who approves of it. Therefore, although experientially (in the life of the believer or Sir Bob) it is as if the demand precedes the approval of the demand, one is obliged to conclude that demand and approval arise at the same time and that the demand is only felt as a demand by a subject who approves of it. Hence, once again, the circularity of ethical experience.

Yet, one might object to this picture of ethical experience in the following terms: if moral statements are, on my account, characterized by strong approval or disapproval of a state of affairs, then how can one deal with the fact that such statements can be made ironically or sarcastically? It is admittedly incontestable that the words ‘love thy neighbour as thyself’ can be uttered with a sneer rather than be sincere. But this simply shows that the statement is being made without strong approval or affirmation, where its implications for action are held at a safe ironic distance rather than becoming internal to the dispositions of moral selfhood. It is a case of excessively weak approval. But this opens onto a more far-reaching objection, that of the immoralist who might approve of statements such as ‘make poverty history’ or ‘famine relief is essential’, but do nothing about them. When the famine relief volunteer knocks at the front door, the immoralist refuses to get off his sofa. In this case, a moral statement might be acknowledged to be legitimate, but is rejected as a maxim for action; the ethical demand is recognized as a demand, but its approval does not entail that one does anything about it. In an important sense, there can be no knock-down response to this objection because the immoralist, like the ironist, can always slip away from making any commitments that would lead from the approval of a demand to action based on that approval. My point is twofold: first that the model of ethical experience provides a way of approaching morality in terms of an affirmation or approved demand that hopefully elicits what I called above the existential matrix of ethics. Second, ethical experience furnishes a possible acount of the motivational force to act morally, of the way in which a conception of the good can move the will to act. This does not imply that an approved demand, say in the case of the immoralist, must move the will to act. Indeed if it did make that implication, then it would be self-defeating as it would eliminate the free activity of the self from the moral realm. The possibility of bad faith is and has to be the long shadow cast by moral commitment. One might exhort, cajole or quarrel with the immoralist, but one must not force him or her to act morally.

Ethical subjectivity

It might already be apparent that my claim about ethical experience being constituted in a demand which I approve is also a claim about the nature of the self. Let me try and clarify this concept of selfhood or ethical subjectivity by advancing two theses, one hopefully uncontroversial and the other a little more controversial.

-

The self is something that shapes itself through its relation to whatever it determines as its good, whether that is the Torah, the resurrected Christ, the moral law, the community in which I live, suffering humanity, all God’s creatures, or whatever. That is, if the demand of the good requires the approval of that demand in order to be experienced as a demand, then that approval is given by a self. Who else could give it? The demand of the good requires the strong approval of the self, otherwise we would be either in the uneasy Rousseauesque dilemma of forcing people to be free, or accepting that moral action consists in the ironic manipulation of norms for which one has no personal commitment – a particularly brutal form of moral externalism. If we turn now to Figure 3, an ethical subject can be defined as a self relating itself approvingly, bindingly, to the demand of its good. Ethical experience presupposes the existence of an experiencing subject. Hopefully, that’s uncontroversial. It’s a simple deduction.

-

Now, more controversially, this claim about the relation of presupposition between ethical experience and the subject of that experience can be deepened in the following way. I have argued that the demand of the good requires approval by a self in order to be experienced as a demand. As such, moral life is an aspect of what it means to be a self, that can be placed alongside other areas of life: epistemic, aesthetic, political and so on. So far, so good. However, one can go on and argue more forcefully that this demand of the good founds the self; or, better, that the demand of the good is the fundamental principle of the subject’s articulation. What we think of as a self is fundamentally an ethical subject, a self that is constituted in a relation to its good, a self – our self – that is organized around certain core values and commitments. Of course, this is another way of claiming the primacy of practical reason to which we will return when we examine Kant.

This second thesis is best argued negatively, through the experience of failure, betrayal and evil. Namely, that if I act in such a way that I know to be evil, then I am acting in a manner destructive of the self that I am, or that I have chosen to be. I have failed myself or betrayed myself. Once again, such a claim is quite formal and does not presuppose any specific content to the good, let alone any moralistic prudishness. For example, my good could be perpetual peace or permanent revolution, merciful meekness or bloody vengeance, the Kantian moral law or the Sadean droit de jouir, where the Divine Marquis believed that one’s right to have an orgasm with whosoever one chose whenever one felt so inclined required the construction of specifically designated sex houses in the streets of Paris. The point here is that the ethical subject is constituted in relation to a demand that is determined as good, and that this can be felt most acutely when I fail to act in accordance with that demand or when I deliberately transgress it and betray myself. I can be as much a failing Sadist as a failing Kantian.

This is why Plato is perfectly consequent when he claims that vice is destructive of self, the deeper point being that the experience of whatever we determine as vice reveals in a negative profile the self that I have chosen to be. Anyone who has tried – and failed – to cure themselves of some form of addiction, whether cigarettes, alchohol, merciful meekness or Sadism, will understand what is meant here. Let me take an example close to my own heart (or lungs), that of smoking. Let’s say that having been a committed smoker for most of my adult life, I decide to quit. I might say to myself repeatedly in the manner of a mantra: ‘I am a non-smoker, my conception of the good excludes smoking, which is bad. It killed my father and I won’t let it kill me. I promised my mother, my sister and my partner that I would stop.’ And yet, I find myself at a party, perhaps in a strange place at the end of a stressful journey, where I am due to give a lecture on a topic that I find particularly difficult. It is a summer’s evening, the fresh trout at dinner is exquisite, the local wine is pleasingly robust, the company is new and charming. A few drinks later, I am offered and accept a cigarette and enjoy the transgression immeasurably. The transgression is repeated several times until late in the night. The following morning I wake up with a throbbing head, a sore throat and a mind full of self-loathing. In the shower, I convince myself I can feel a malignant cancerous growth under my left shoulder blade.

What has taken place here is that the ethical subject that I have chosen to be enters into conflict with the self that I am, producing a divided experience of self as self-failure. As will be familiar to many of us, the affect or emotion that accompanies this experience is guilt. Guilt is the affect that produces a certain splitting or division in the subject, something that Saint Paul understood rather well, ‘For the good that I would I do not: but the evil which I would not, that I do’.[8] This experience of self-division is the genesis of the morsus conscientiae, the sting of bad conscience, what Joyce – in Anglo-Irish – Middle English – calls ‘the agenbite of inwit’. Nietzsche, who in many ways is the Siamese twin of Saint Paul, calls bad conscience ‘This most uncanny and most interesting plant of all our earthly vegetation.’[9] The guilty conscience is a strange fruit, for Nietzsche a late fruit, and we shall return to the question of split ethical subjectivity in some detail below when we turn to that most oddly perfect of Nietzscheans, Emmanuel Levinas.

However, the point at issue here is that the phenomenon of guilty conscience reveals – negatively – the fundamentally moral articulation of the self. Namely, that ethical subjectivity is not just an aspect or dimension of subjective life, it is rather the fundamental feature of what we think of as a self, the repository of our deepest commitments and values. Ethical experience presupposes an ethical subject disposed towards the approved demand of its good.

Justifying reasons and exciting reasons

In my view, all questions of normativity, whether universalistic or relativistic, have to follow from some conception of what I am calling ethical experience. That is, without the experience of a demand to which I am prepared to bind myself, to commit myself, the whole business of morality would either not get started or would be a mere manipulation of empty formulae. At the basis of ethics, there has to be some experience of an approved demand, an existential affirmation that shapes my ethical subjectivity and which is the source of my motivation to act.

In this regard, as a contemporary illustration, consider Axel Honneth’s quasi-Humean critique of Habermas’s moral rationalism on the point that discourse ethics lacks an adequate account of motivation to moral action because there is a gap between universal pragmatics and everyday experience.[10] Honneth attempts to respond to this lack by supplementing the Habermasian theory of justice with a conception of the good based in an account of recognition (Anerkennung). This is the recognition of a demand, in Honneth’s case the demand for love as the basic prerequisite for self-realization. The claim here is that it is only on the basis of such a story about recognition that what Habermas calls ‘the other of justice’, namely solidarity, can be more than an abstraction. Of course, the irony is that Honneth’s critique of Habermas replicates precisely the guiding intention of Habermas’s early work, namely the attempted unification of knowledge and human interests in a critical and emancipatory concept of reflection that would escape any reductive positivistic explanation. It remains an open question, however, to what extent Habermas’s later work succeeds or falls short of this laudable intention.

As is always the case in philosophy, this is really a much older debate that goes back at least to Francis Hutcheson’s critique of moral rationalism in the 1720s and his useful distinction between justifying reasons that legitimate an action on the grounds of generality or universality, or indeed custom, authority and tradition, and exciting reasons that would lead a subject to perform such an action in the first place. For Hutcheson, the springs of morality find their source in the sentiment of benevolence that he believed to be common to all persons. For Hutcheson, and for the tradition of moral sense theory that he inspires, namely Adam Smith and Hume, but also Rousseau and Schopenhauer, there can be no account of exciting reasons, and hence no motivating moral theory, without a theory of moral sentiments, affections or passions.[11] This is the role of sympathy for Smith and Hume, and compassion or pity for Rousseau and Schopenhauer. We shall have occasion to go back to the question of the passions when we turn to psychoanalysis later in this book.

However, the basic problem with Hutcheson, and this is something one finds in Hume’s and Kant’s critiques of moral sense theory, is the following: whilst the critique of Mandeville’s moral egoism is admirable, and the critique of moral rationalism with reference to moral sense, affection or passion might well be justified, what is not justified is the assumption of commonality that Hutcheson assumes for his position. Namely, how can one assume that the feeling of benevolence is universal? More pointedly, why should I approve of Hutcheson’s benevolence rather than Mandeville’s egotistical self-interest? The commonality of benevolence is simply an assumption, and the argument for its priority over self-interest is sheer assertion.[12] Thus, Hutcheson’s account of moral sense lacks universality and risks reducing morality to simple empirical inclination.

This raises the following vast question: can ethics be both generalizable and subjectively felt, both universalizable and rooted in our moral selfhood, or are these two halves of a dialectic that cannot be reconciled? Such is what Michael Smith describes as ‘the moral problem’, which for him is essentially a problem for philosophers although I believe it points towards something much deeper in the relation between moral theory and moral life.[13] In Smith’s terms, beginning from a Humean psychology, there is a contradiction between beliefs and desires, that is, between moral beliefs which can be rationally vindicated, and the desires which motivate action on those beliefs, but which may or may not attach themselves to such beliefs. To return to the example of the immoralist, I may be rationally convinced that giving to famine relief is the right thing to do and yet not give because I am insufficiently motivated due to indifference, distraction or laziness. For Smith, there is a contradiction between the objectivity of morality, namely that we want to believe that our moral views are right independent of our subjective inclinations and can be rationally defended, and the practicability of morality, where having a moral view is supposed to be linked to what we are motivated to do. If the objectivity and practicability of moral judgement are pulling in opposite directions, if morality is not both generalizable and subjectively felt, then perhaps the very idea of morality is incoherent. Although this is not Smith’s concern and certainly not his solution to the moral problem, it is to this threat of incoherence that I believe Kant responds. We will see whether or not it is a coherent response.

Kant, for example – the fact of reason

Kant calls that which would produce the power to act morally, the motivational force that would dispose the self towards the good, ‘the philosopher’s stone’.[14] However, for Kant, such a story about motivation cannot, as for Hutcheson and the moral sense theorists, resolve itself with reference to the passions or moral sentiments like benevolence, sympathy or compassion because that would reduce morality to inclination, and rationality to what Kant calls ‘pathology’. The key question of Kant’s critical philosophy insofar as it subscribes to the primacy of practical reason is simply: how can pure reason be practical? Kant recognizes that the response to this question requires some sort of account of the connection of reason to interest or motivation, but this cannot be an empirical or pathological interest (particular beliefs, inclinations and desires), but must be what he calls a ‘pure interest’ or, even more oddly, an ‘a priori feeling’, namely respect for the moral law.

So how can Kant find the philosopher’s stone? The question of ethical experience in Kant resolves itself in the seemingly contradictory notion of the fact of reason (das Faktum der Vernunft).[15] I say ‘seemingly contradictory’ for how could reason, which is the faculty of apriori cognitions, take on aposteriori, factual form? How could there be a facticity of reason? Wouldn’t that require the sort of intellectual intuition explicitly forbidden by the epistemological strictures of the First Critique? For Kant, the fact of reason is the claim that there is a Faktum which places a demand on the subject and to which the subject assents. That is, there is a demand of the good, for Kant the consciousness of the moral law, of which the subject approves, and this demand has an immediate, incontrovertible, even apodictic certainty that is analogous to the binding power of an empirical fact or Tatsache. The difference between the apodicticity of a Faktum der Vernunft and an empirical Tatsache is that the demand of the fact of reason is only evident insofar as the subject approves it. Of such an apodictic Faktum, Kant insists, no example can be found: ‘The moral law is given, as an apodictically certain fact, as it were, of pure reason, a fact of which we are a priori conscious, even if it is granted that no example could be found in which it has been followed exactly.’[16] The fact of reason is only experienced as the certainty of demand by the subject who approves of – it virtuous circularity once again.

However things may stand with the doctrine of the fact of reason, Dieter Henrich argues, rightly I think, that the entire rational universality of the categorical imperative and Kantian moral theory follows from this experience of moral insight, or what I am calling ‘ethical experience’. The function of the fact of reason in Kant is to try to close the gap between justification and motivation. The philosopher’s stone would consist precisely in establishing the link between the motivational power of the fact of reason and the rational universality of the categorical imperative. In this way, reason would be identical with the will to reason and the perennial question, ‘why should I be moral?’, would be answered.

The auto-authentification of the moral law – some contemporary Kantians

Let me try to unpack this Kantian argument in a little more detail by turning to some contemporary Kantians, in particular John Rawls’s compelling reconstruction of the fact of reason in his Lectures on the History of Moral Philosophy.[17] The ambition of Kant’s ethics is twofold: firstly, to show that the moral law has objective validity, that it is binding upon practical reasoning; and secondly, that the moral law applies to us, it is something we can act from and not merely in accordance with. In Michael Smith’s terms, Kant is trying to address the moral problem by reconciling objectivity with practicability. To achieve this twofold ambition, Rawls identifies four conditions that must be met by the categorical imperative.

-

The content condition – that the categorical imperative must not be formal and empty, but must specify requirements on moral deliberation, i.e. that maxims or norms of action must be shown to be capable of deliberation on the basis of the categorical imperative.

-

The freedom condition – that the categorical imperative must represent the moral law as something we freely will, i.e. morality must flow from the principle of autonomy.

However, in order for the moral law to be authoritative for us, such that we act from it and not merely in accordance with it, two further conditions are required.

-

The fact of reason condition – that the authority of the moral law must be practically located in our everyday moral thought, feeling and judgement.

-

The motivation condition – that the consciousness of the moral law as supremely authoritative for us must be so rooted in our person that this law, by itself, is sufficient motive for us to act.

In order to actualize pure practical reason, all four conditions must be met. Conditions 1 and 2, although absolutely essential, would remain abstract and remote without conditions 3 and 4; that is, we would have moral objectivity without practicability. Condition 4 provides the deep structure of 3, showing how the consiousness of the moral law is so rooted in our ethical subjectivity, regardless of natural desires and animal inclinations, that it is sufficient motive for us to act. Kant’s most lyrical moments are those when he describes the manner in which the subject is filled with awe at ‘the starry heavens above me and the moral law within me’.[18]

The fact of reason is our consciousness of the moral law as supremely authoritative and regulative for us, as something we act from and not merely in accordance with. If we keep this is mind, then we can see the huge problem that it solves for Kant’s critical project. It cannot be that our knowledge of the moral law is based upon a consciousness of freedom because that would require the kind of intellectual intuition forbidden by the argument of the First Critique and reintroduced in diverse ways by Fichte and Schelling. Rather, Kant’s position is the reverse: the fact of reason is the basic fact from which our moral conception of ourselves as free must begin. Rawls writes,

The significance of the fact of reason is that pure practical reason exhibits its reality in this fact and in what this fact discloses, namely our freedom. Once we recognize the fact of reason and its significance, all disputations that question the possibility of pure practical reason are vain. No metaphysical or scientific theories can put it in jeopardy.[19]

This raises the following fascinating question in Kant’s ethics: namely, what kind of authentification does the moral law have? Famously, Kant claims that whilst freedom is the ratio essendi of the moral law, we can have no intuition of freedom for the reasons set out in the First Critique. Therefore, the moral law is the ratio cognoscendi of freedom. However, the only authentification of the moral law as binding upon us is the fact of reason. The latter is the subjective guarantee of the determination of the will by the moral law. Rawls continues,

In the Second Critique, Kant recognizes … and accepts the view that pure practical reason, with the moral law (via the categorical imperative) as its first principle, is authenticated by the fact of reason and in turn by that fact’s authenticating, in those who accept the moral law as binding …[20]

That is to say, the only authentification or justification for the moral law as binding upon us follows from the fact that there are subjects who recognize that the moral law has this binding power. To push this a little further, the fact of reason is the auto-authentification or self-justification of the moral law. Kant closes the gap between justification and motivation or objectivity and practicability in ethics by making the fact of reason the self-justifying motivational force for moral action.

What the problem of the fact of reason shows, I think, is the fragile necessity at the heart of Kant’s ethics, and indeed the entire critical project insofar as freedom is the ‘keystone of the whole architecture of the system of pure reason’.[21] Morality is rooted in the self-justifying or auto-authenticating approval of the demand of the fact of reason, a fact that is not reducible to empirical intuition and of which ‘no example can be found’. If Kant offered more empirical or experiential substance to the fact of reason, then he would risk relativizing it in the way we saw criticized in Hutcheson and we would have practicability without objectivity. If Kant offered less subjective appeal to the fact of reason, then he would risk reducing the moral law to an abstraction and we would have objectivity without practicability.

This problematic of the fact of reason can be shown to be at work in other contemporary moral philosophers of Kantian inspiration. Let me take the examples of Jürgen Habermas, Onora O’Neill and Christine Korsgaard. In the very final words of his 1972 Postscript to Knowledge and Human Interests, Habermas notes that the ambition of a theory of communicative action would be to show how transcendental features of reasoning and argumentation are built into the very praxis of social life. In other words, the formal universality of Kantianism has its feet set in the concrete of Hegelian ethical life. He then makes the following fascinating remark, which we have already anticipated in Honneth’s critique discussed above,

Since empirical speech is only possible by virtue of the fundamental norms of rational speech, the cleavage between a real and an inevitably idealized (if only hypothetically ideal) community of language is built not only into the process of argumentative reasoning but into the very life-praxis of social systems. In this way, perhaps the Kantian notion of the fact of reason can be revitalized.[22]

In other words, the ambition of Habermas’s theory of communicative action is the revitalization of the Kantian notion of the fact of reason where the implicit rationality of discourse would reconcile justification and motivation, objectivity and practicability in morality.

In Towards Justice and Virtue, O’Neill recognizes the problem of motivation as a real problem for her post-metaphysical reworking of Kantian ethics. O’Neill redescribes universalizability as follow-ability, namely that reasons for action must be reasons for all, but she remains silent on the topic of motivation, although follow-ability must be followable by an ethical subject and hence implicitly motivating.[23] A rather different variation on the Kantian position can be found in Christine Korsgaard’s The Sources of Normativity.[24] On the one hand, she defends the Kantian view that reflective endorsement is morality itself: namely, that maxims or norms of action have to be subject to critical scrutiny before being either rejected or endorsed. Negatively stated, this means that if maxims cannot be willed as universal laws, then they must not be accepted. This is classically Kantian. However, on the other hand, Korsgaard acknowledges the implicitly Hegelian critique of this Kantian position, as indeed does Habermas, namely that reflective endorsement is open to the charge that the price of universality in ethics is abstraction and formality, where the Kantian subject – like some latter day Stoic – resolutely wills universal maxims that have no place in actual ethical life. To counter this objection, Korsgaard advances the notion of practical identity, which is her attempt to rework and ‘thicken’ Kant’s notion of the Kingdom of Ends: namely, that one’s moral action is as a self embedded in personal relationships and the networks of family, community and the like. The notion of practical identity has a distinct family resemblance to the problem that Kant wishes to address in the fact of reason, namely to show how moral motivation takes root in our very person and its willed commitments.[25]

The autonomy orthodoxy and the question of facticity

The basic principle of Kant’s ethics is autonomy. That is, the only maxims upon which I should act are ones that I will myself, that I give myself. Thus, I am the only source of moral authority and Kantians are and have to be self-legislators. If this were not the case, then I would not be acting freely, but would be acting on norms that I had not myself chosen. If the source of moral authority lies outside myself, in God, the monarch, my employer, tradition, or any norm or norms which I feel as externally binding, then I am acting heteronomously, not autonomously.

However and this is the basic operation of Kant’s ethics – I am a rational being and furthermore all human beings are rational. For Kant, rationality is the principle of humanity, which is what Rawls calls in one florid moment, ‘the aristocracy of all’.[26] If human beings are rational beings, then the norms that govern the practical lives of humans must be chosen from reason rather than sentiment, which is always particular and contingent. Therefore, in choosing norms rationally for myself I necessarily choose them for all humanity. In making the law for myself, I am making the law for any human being. Therefore, autonomy in ethics entails universality: the only norms upon which I can legitimately act are those which I can consistently will as a universal law. Such is the argument for the categorical imperative in Kant.

Returning to our earlier argument, we have seen that the fact of reason is our consciousness of the determination of the will by the moral law, and therefore the condition of possibility of morality. Now, because Kant’s moral theory is based on the principle of autonomy, the fact of reason has to correspond to the will of the subject. The fact of reason is, indeed, a fact. Experientially, it is the otherness of a demand. But this demand has to correspond to the subject’s autonomy. It is a fact that has to be an act. In other words, the ethical subject has to be apriori equal to the demand that is placed on it otherwise it would lapse into heteronomy.

In my view, the problem of the fact of reason is the index of a dilemma that determines and arguably divides post-Kantian philosophy. The claim at the basis of the fact of reason is that in order to deal with the problem of motivation, interest or practicability, there has to be a moment of facticity within reason, although this facticity is not the empirical moral feeling of Hutcheson or Hume, but the pure feeling of respect or reverence for the moral law, an apriori feeling. Now, crucially, although reason has to include this moment of facticity within itself in order to explain the problem of motivation, this fact cannot itself be explained. This is the problem that Kant wrestles with in the final, agonised paragraphs of the Grundlegung. Philosophically throwing his hands in the air, Kant writes, ‘how pure reason can be practical – all human reason is totally incapable of explaining this, and all the effort and labour to seek such an explanation is in vain’.[27] In other words, we have to accept that the universality of the moral law should interest us without being able to explain the cause of that interest. That is to say – and mark the strangeness of this claim – that all we can comprehend of the determination of our will by freedom is its incomprehensibility.

Now, the question is whether this incapacity of explanation is a weakness or a strength. For Fichte, it is a weakness and he attempts to unify theoretical and practical reason through a notion of intellectual intuition. The latter, however, is nothing particularly occult. Rather, Fichte’s argument is simply that the moral law becomes internalized in the subject and moral autonomy takes place in and as the self-reflective activity of the subject. He writes, ‘Intellectual intuition is the immediate consciousness that I act and of what I do when I act.’[28] For Fichte, intellectual intuition is the self-consciousness of oneself as active; ‘Without self-consciousness there is no consciousness whatsoever, but self-consciousness is possible only in the way we have indicated: I am only active.’[29] One might say that Fichte replaces Kant’s fact of reason with an act of reason. But rather than seeing this as a critique of Kant, and despite all of Kant’s protestations against the possibility of intellectual intuition, Fichte sees the basic principle of his Wissenschaftslehre as entirely consistent with the fundamental, animating principle of Kant’s system. Fichte asks, ‘For Kant would certainly maintain that we are conscious of the categorical imperative, would he not?’ And he goes on, ‘Our consciousness of the categorical imperative is undoubtedly immediate, but it is not a form of sensory consciousness. In other words, it is precisely what I call “intellectual intuition”.’[30] Intellectual intuition is obviously not sensuous intuition. However, nor is it intuition of a metaphysical entity of some kind, like God or the soul. Rather, intellectual intuition is simply the self-intuiting of the subject as active, more specifically as actively determining itself by and through the categorical imperative. Intellectual intuition in Fichte is the consciousness of the moral law. The facticity of reason becomes the activity of the subject.

Hegel also rejects the Kantian version of moral insight in the strongest terms as that ‘cold duty, the last undigested lump (Klotz) in our stomach, a revelation given to reason’.[31] He criticizes Fichte and locates moral autonomy not in the self-awareness of the activity of the subject but in relations of intersubjectivity which are constituted by a struggle for recognition.[32] Following Terry Pinkard’s reading, we might say that Hegel socializes Kantian practical reason.[33] On a Hegelian view, the dilemma at the heart of the Kantian project takes the following form: how can I be subject to a law of which I am the author, given that I can only be legitimately subject to such a law because of the governing principle of autonomy. Hegel shows how this Kantian dilemma requires an intersubjective solution, namely that it is necessary to show, firstly, that reason is social, and secondly, that the sociality of reason unfolds historically and cannot be reduced to the formal decision procedure of the Kantian categorical imperative or the solitary activity of the Fichtean ego.

We might also mention Marx in this connection. When Marx writes in the famous eleventh thesis on Feuerbach that ‘philosophers have only interpreted the world in different ways, the point however is to change it’,[34] what he means is that practical reason must be located in actual praxis, in shared human life. This is what Marx will call, with an implicit nod back to Fichte, ‘subjectivity’ or ‘living activity’. For Marx, the philosophical and political task is the location, description and auto-emancipation of a group who will make philosophy practical and make praxis philosophical. This is the role he assigns to the proletariat who are designated as the universal class and the index of humanity. If Hegel socializes autonomy, then Marx communizes it, where the Kantian kingdom of ends moves from being a postulate of practical reason to an actual realm on earth without kings. Of course, this does not mean that Marx’s profession of materialism removes him from the idealist tradition with its focus on the question of autonomy. On the contrary, what we might call Marx’s ‘materialism of practice’ can be seen as the consummation of that tradition that locates autonomy in the life-practice of the proletariat who are what Etienne Balibar calls ‘the people of the people’ (le peuple du peuple), the party of humanity.[35]

Counter-intuitive as it might appear, one can find the inheritance of the Kantian problem of the fact of reason in Heidegger’s analysis of the conscience of Dasein or the human being in Being and Time. The experience of conscience is that of a call (Ruf) or appeal (Anruf) which seems to come from outside Dasein, but which is really only Dasein calling to itself. Heidegger writes, ‘In conscience Dasein calls itself.’[36] In this sense, the structure of ethical experience in the early Heidegger, at least in the analysis of authenticity, is an existential deepening of Kantian autonomy. When I pull myself out of the slumber of my inauthentic existence and learn to approve the demand of conscience, which for Heidegger is the demand of my finitude confronted in being-towards-death, then I become authentic, I become who I really am. This is what Heidegger means by ‘resoluteness’ (Entschlossenheit), which is best understood as a form of autarchy, self-legislation or self-origination. Heidegger recognizes as a ‘positive necessity’ the Faktum that has to be presupposed in any analysis of Dasein. The Kantian fact of reason becomes, in Heideggerese, the ontic testimony or attestation (Zeugnis) of conscience. Crucially, Dasein is not determined by reason, but rather in terms of a pre-rational realm of moods (Stimmungen) and a basic mood (Grundstimmung) of anxiety, but the autarchic structure of authentic Dasein is an existential echo of the Kantian subject.[37]

Other examples could be given, but the point is that for Fichte, Hegel, Marx and Heidegger and their many heirs in the philosophical tradition, the philosophical goal remains some conception of autonomy, whether the individual ego, individualized Dasein, the intersubjectively constituted realm of Spirit, the collective praxis of the proletariat as the index of humanity, or whatever. Let’s say that post-Kantian philosophy, from left to right, from Marx to Heidegger, is dominated by what we might call the autonomy orthodoxy.[38]

Another possible line of inheritance from Kant that I would like to open in the construction of a model of the ethical subject takes precisely the opposite course from the autonomy orthodoxy. This approach would see the moment of ineliminable facticity in Kantian moral reflection as a strength rather than a weakness. On such a view, what Kant implicitly acknowledges in the doctrine of the fact of reason is that the discovery of the philosopher’s stone is dependent upon the experience of a demand that halts the philosopher in their tracks and prevents the possession of any miraculous stone. The self confronts a Faktum that places an overwhelming demand upon it, and in relation to which it shapes itself as an ethical subject, yet that Faktum seems to resist being either explained or understood. As Kant acknowledges in the paradoxical penultimate sentence of the Grundlegung alluded to above, ‘While we do not comprehend the practical unconditioned necessity of the moral imperative, we do comprehend its incomprehensibility.’[39] It is this moment of incomprehensibility in ethics that interests me, where the subject is faced with a demand that does not correspond to its autonomy: in this situation, I am not the equal of the demand that is placed on me. I will now go on to discuss various beneficiaries of this alternative inheritance, whether it is the face of the other person in Levinas, the unfulfillable and one-sided character of the ethical demand in Løgstrup, or the relation to the real in Lacan. For each of them – and us – ethics is obliged to acknowledge a moment of rebellious heteronomy that troubles the sovereignty of autonomy.

Dividualism – how to build an ethical subject

We never know self-realization.

We are two abysses – a well staring at the sky.Fernando Pessoa, The Book of Disquiet

Let me review where we have got to in the argument of this book. I began by laying out how I see philosophy beginning in disappointment. That is, philosophy, modern post-Kantian philosophy, begins not in an experience of wonder at what is, but from an experience of failure and lack. One senses that things are not simply wonderful. The two main forms of disappointment analyzed here are religious and political: religious disappointment provokes the question of meaning (what is the meaning of life in the absence of a transcendent deity who would act as a guarantor of meaning?) and opens the problem of nihilism; political disappointment provokes the question of justice (how is justice possible in a violently unjust world?) and provokes the need for an ethics.

In the Introduction, I engaged in a little Zeitdiagnose and tried to paint a picture of the present age. I considered a couple of coherent, tempting, but in my view deeply misguided, diagnoses of our times, social pathologies if you prefer. I labelled them ‘active nihilism’, where I talked about those who seek a violent destruction of the purportedly meaningless world of capitalism and liberal democracy; and ‘passive nihilism’, where I discussed forms of ‘European or American Buddhism’, contemplative withdrawal, where one faces the meaningless chaos of the world with eyes wide shut. I rejected both forms of nihilism, but suggested that each of them expresses a deep truth: namely, their identification of a motivational deficit at the heart of liberal democracy, a sort of drift, disbelief and slackening that is both institutional and moral. In the drift of this deficit, we experience the moral claims of our societies as externally compulsory, but not internally compelling. We approach ethical issues in a spirit of Diogenean cynicism rather than free commitment, a spirit in which, as Yeats writes, the best lack all conviction, whilst the worst are full of passionate intensity. The question, then, is how might we fill the best with passionate intensity? I claimed that what was required to deal with this motivational deficit was a motivating, empowering ethics of commitment and political resistance.