Stephanie Kirchner

Postcard: Berlin

Germans nostalgic for the Cold War can visit Checkpoint Charlie, ride in a Trabant and drink in a secret-police theme bar. In the new Germany, a hankering for the bad old days

“I don’t know if I ever hit anyone. It was always dark,” says Hans-Holger, a 50-year-old truck driver, recalling his days as a 19-year-old border guard for the old German Democratic Republic, when he was required to shoot at fellow citizens trying to flee into West Germany. Hans-Holger, who will give only his first name, later served a 17-month prison sentence himself for attempting to escape. Still, he’s nostalgic for the old East, which is why he’s a regular at Zur Firma, an East Berlin pub whose theme derives from the G.D.R.’s feared secret police, the Stasi. “I feel snug in this place,” he says.

With its orange walls and rustic interior, the bar looks like any other in the former working-class district of Lichtenberg–but instead of a deer head mounted on the wall, Zur Firma has a surveillance camera over its front door. Other appointments include old wiretap devices and furnishings from what appears to be a 1970s interrogation room. Then there’s the venue’s name, which translates as “The Firm,” a sobriquet for the Stasi. And its slogan: “Come to our place–or we’ll come to yours.”

Victims’ organizations don’t see the joke. They reacted furiously when the pub, situated just yards from the massive gray complex that used to house the Stasi, opened last month. The Union of Organizations for the Victims of Communist Oppression called for a boycott, warning that Zur Firma would “negate the suffering of thousands of former political prisoners.” Owner Wolfgang Schmelz dismisses the accusations. “Nothing is being trivialized here; no victims are being mocked,” he insists. “All it is, is satire.”

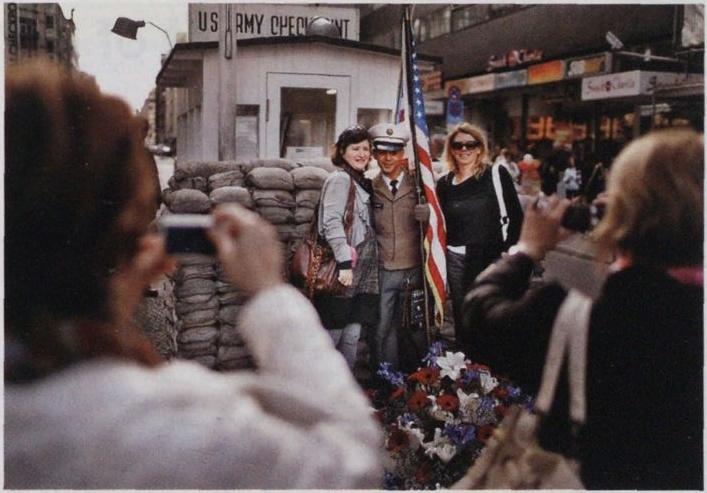

Making light of East Germany’s dark, prereunification past–“ostalgia,” as the phenomenon is known–has come into vogue in recent years. Visitors to the once divided German capital can shop for G.D.R. souvenirs; stay at the Ostel, a G.D.R.-themed hostel; and take a “Trabi-safari,” which involves sightseeing in a Trabant, the notoriously rickety East German automobile. Last month former Berlin senator for cultural affairs Thomas Flierl denounced as “tasteless mockery” a service that allows tourists at Checkpoint Charlie, the former crossing between East and West Berlin, to pose with actors dressed as U.S. and Russian soldiers.

The ostalgia industry leaves observers like Klaus Schroeder speechless. “People really seem to think the G.D.R. was a big joke, which results in such crudities as a Stasi pub,” says the political-science professor at Berlin’s Free University. “What’s next, a Gestapo Inn?” In a recent survey of 5,000 German teens, Schroeder and his colleagues found that many, especially those living in the former East Germany, had an extremely distorted view of it. More than half of respondents believed that the G.D.R. was “not a dictatorship” and that the Stasi was an intelligence service like any other, instead of ruthless secret police who helped detain, torture or harass an estimated 200,000 political prisoners. “What people remember is not the real G.D.R. but a fictitious country that never existed,” says Schroeder.

So why the fond memories of such an oppressive political system? “The older people are aware of what the G.D.R. really was like, but they don’t say it,” Schroeder says. “People generally tend to have a blurred vision of their own past lives. And the public and schools have failed to act as a counterbalance.”

An overwhelming cause of ostalgia, however, is the economic hardship that followed reunification in 1990, as residents of the former G.D.R. struggled to keep up with their capitalist brothers to the west. Unemployment in the region runs close to 13%, more than double that in the rest of the country, prompting idealized memories of a time when the state assigned a job to every citizen. A Zur Firma regular named Jutta, 50, says the memories she shares with her 22-year-old daughter are less of the oppression than of the camaraderie. “I tell her that people were there for each other without expecting something in return,” she says. As Hans-Holger notes over his beer at the bar, “Ostalgia is better than what we have today.”