Steven E. Jones

Against Technology

From the Luddites to Neo-Luddism

1. The Boom, the Bust, and Neo-Luddites in the 1990s

The 1990s Moment of Neo-Luddism

Ned Ludd and the Anti-Globalization Movement

Antiglobalization, Antitechnology

2. The Mythic History of the Original Luddites

Romantic Robin Hood, Romantic Ned Ludd

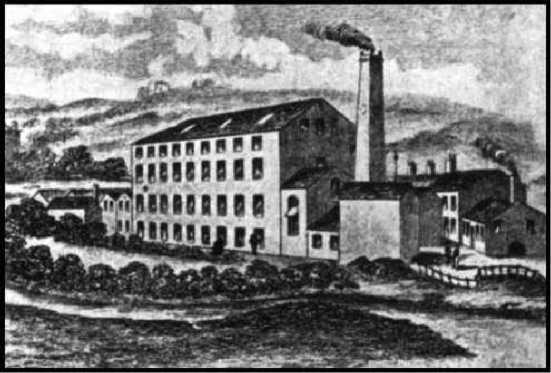

The Romantic Siege of Rawfolds Mill

The Dumb Steeple at the Crossroads (of Folklore and History)

4. Frankenstein and the Monster of Technology

The Shelley Circle and the Luddites

The Shelley Circle and the Ideal of Scientific Progress

Neo-Luddites Reading Frankenstein

Monstrous Science, Mad Scientist

A Golem in the Underground City of Metropolis

The Monster of Autonomous Technology

The Making of the English Working Class

Scarlea Grange or, a Luddite’s Daughter

Through the Fray: a Tale of the Luddite Riots

Coda: Novelizing History and Legend

6. Counterculture and Countercomputer in the 1960s

Counterculture Against the Machine

The Appropriate-Technology Subculture

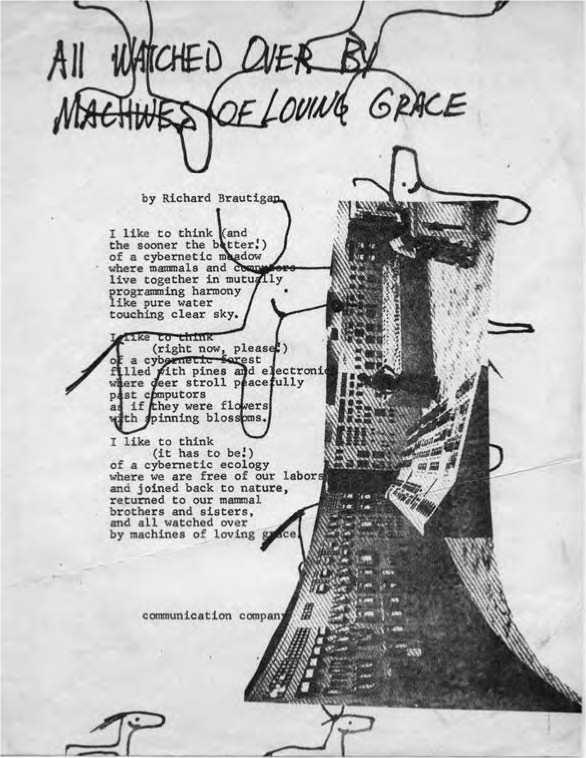

Mimeograph Machines of Loving Grace

Counterculture to Hacker Subculture

Stewart Brand’s Alternative Technology

Counterculture and Countercomputer

Thomas Pynchon’s Neo-Luddite Paranoia

7. Ned Ludd in the Age of Terror

Remember York, the Florence Manifesto

Front Matter

Publisher Details

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

New York London

Routledge is an imprint of the

Taylor & Francis Group, an informa business

"All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace," in The Pill versus The Springhill Mine Disaster 1968 by Richard Brautigan is reprinted with permission of Sarah Lazin Books.

Published in 2006 by Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group 270 Madison Avenue New York, NY 10016

Published in Great Britain by

Routledge

Taylor & Francis Group

2 Park Square

Milton Park, Abingdon

Oxon OX14 4RN

2006 by Taylor & Francis Group, LLC

Routledge is an imprint of Taylor & Francis Group

Printed in the United States of America on acid-free paper

10987654321

International Standard Book Number-10: 0-415-97867-X (Hardcover) 0-415-97868-8 (Softcover)

International Standard Book Number-13: 978-0-415-97867-5 (Hardcover) 978-0-415-97868-2 (Softcover)

Library of Congress Card Number 2005031322

No part of this book may be reprinted, reproduced, transmitted, or utilized in any form by any electronic, mechanical, or other means, now known or hereafter invented, including photocopying, microfilming, and recording, or in any information storage or retrieval system, without written permission from the publishers.

Trademark Notice: Product or corporate names may be trademarks or registered trademarks, and are used only for identification and explanation without intent to infringe.

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Jones, Steven E., 1959-

Against technology : from the Luddites to Neo-Luddism / Steven E. Jones.

p. cm.

Includes bibliographical references and index.

ISBN 0-415-97867-X (hb) -- ISBN 0-415-97868-8 (pb)

1. Technology--Social aspects. 2. Technology and civilization. 3. Luddites. I. Title.

T14.5.J66 2006

303.48'3--dc22 2005031322

Taylor & Francis Group is the Academic Division of Informa plc.

Visit the Taylor & Francis Web site at http://www.taylorandfrancis.com

and the Routledge Web site at http://www.routledge-ny.com

Dedication

To the memory of Alvin Addison Snider

Acknowledgments

Everybody knows that writing a book requires a network of distributed support and production. In writing this one I was helped by other scholars, curators, Webmasters, collectors, friends, and family. I’m grateful first of all to the self-described Luddite informants I cite anonymously (and, I hope, sympathetically) in the Introduction and Chapter 7. Among my colleagues, Kevin Binfield, then at the University of Nottingham, shared his work in progress on Luddite texts (we once exchanged e-mails on the punctuation of “General Ludd’s Triumph,” I in the coffee shop at the Public Record Office outside of London, he at that time here in the U.S.). Later he offered valuable advice on this book in progress, and he has continued to share knowledge and texts. Adriana Craciun invited me to Nottingham for a lecture at just the right time and saved time in my schedule for some reading in the library as well as a wonderful special tour of Byron’s Newstead Abbey. Huddersfield local historian Lesley Kipling was very helpful in correspondence. So was John H. Rumsby, Museums Collections Manager at the Kirklees Community History Service, Huddersfield (and the museum staff was cheerful in person); I am grateful to Mr. Rumsby for permission to reproduce the images of Luddite artifacts and the drawing of Rawfolds Mill held in that collection, and to his colleague Chris Yeates for taking the photographs of those artifacts. John F. Barber was warmly encouraging in a series of e-mail exchanges about Richard Brautigan; as a result, I eventually found and purchased a copy of the broadside used as an illustration in Chapter 6. To Sarah Lazin Books I am grateful for permission to quote from the pivotal Richard Brautigan poem originally printed in that broadside, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace.” Marilyn Gaull, as always, was there when needed — even to the point of correcting the style of an early partial draft. Along those lines, my thanks go to an anonymous reader at Routledge for suggestions that greatly improved the manuscript. It has also benefited from the editorial efforts of William Germano and especially Matthew Byrnie. My American Studies colleague Christopher Castiglia kindly read and commented on Chapters 6 and 7 (even though he’s not too crazy about technology himself). Neil Fraistat read early drafts and shared them with the students in his Techno-Romanticism class. Several classes of my own at Loyola University Chicago helped me formulate and test portions of various chapters. Orianne Smith, who was beginning her own dissertation as I started thinking about this book and has just taken the Ph.D. as I complete it, read the first draft of Chapter 1 and talked with me about the project over coffee at the Unicorn Cafe. She also served as an able research assistant, here and in the U.K. Some research and travel support was granted by Loyola University Chicago; those same forms of support — as well as so many more, and much more significant ones — were granted by the incomparable Emi and Henry, and the always generous Heidi S. Jones, who associates many things with many things.

Introduction

Are you a Luddite? Do you know someone who is? Someone who is fed up with technology and resists its dominance over our daily lives — even if in little ways, by avoiding computers or video games, the daily commute in the car, or a cell phone? Or, since it seems increasingly impossible to relinquish or escape from these forms of ever-present technology, at least the contemporary Luddite may (with some irony, to be sure) speak out against its dominance, may question the authority of technology even as it continues to be exercised all around him or her. What else can one do? Is it even possible any more (if it ever was) to resist technology? This book addresses the question of what it might mean nowadays to call oneself a Luddite — to take a position against technology.

On the urban campus where I teach, just like on campuses everywhere, students walk along with one iPod earbud dangling free so they can talk on their cell phones while listening to music. When evening classes let out, their ring tones begin to play all at once as the phones flip open, screens glow, and they migrate across the lawns like giant schools of cyborg jellyfish. Of course, many of these students also have in their backpacks laptops on which they write papers and store huge collections of MP3s, some to be transferred to their iPods, most of them probably downloaded in their dorm rooms using peer-to-peer file-sharing programs over the same network that allows them to register for classes and instant-message their friends. The network also allows me to input their grades, post syllabi, create course Weblogs, or access their transcripts. Every year some of these same students tell me that they think there is too much technology in modern life. Some of them, usually green-activists , ironically refer to themselves as Luddites — but this does not necessarily mean they’re not just as wired, as saturated with technology, as their classmates. They assume, like everyone else, that technology is a fact of life — the air they breathe, the water in which they swim, like it or not.

I know that many of these students will go on to careers in what is called “knowledge work.” More of them than ever before will make their living by producing or maintaining or processing technology and (even more likely) the forms of information and commerce that technology makes possible. Even many of those with less obviously technological jobs will spend their leisure hours engaged with technology and media, video games and large-screen TVs and personal computers. The degree to which they get it (or don’t) when it comes to this governing idea — that technology is the central fact of the modern global economy — will often help to define their status, determine their livelihoods, and shape their work and leisure time. This is not about having specific technical skills — I’m not talking about engineers and computer science graduates. It’s about the willingness to buy into two widely shared assumptions: (1) that technology’s place in our daily lives is central; and (2) that it will inevitably increase in the future.

In the face of this seeming inevitability, this done-deal with technology, a low-level anxiety persists about what technology is doing to us: the environmental consequences of genetically modified foods, children’s dependence on antidepressants, reduced social interaction among the “pod-people” lost in their own soundtracks or people who compulsively flip open their phones every time they are out in public. Everyone participates but everyone from time to time worries — often with a wry irony that only partly covers their anxiety — that technology is taking over, dominating our lives. The revival of interest in Isaac Asimov’s theories of robotics, as seen in the recent movie, I, Robot (2004), by which humankind attempts to formulate laws to prevent such a takeover, is only one symptom among many of this persistent cultural anxiety. Some worry enough to adopt an attitude of general resistance, an antitechnology philosophy based on doubts about the whole idea of technological progress. Nonetheless, these quixotic dissidents within the technological society often share with happy technocrats the fundamental assumption that technology is taking over — or has already done so, for all practical purposes. Those who resist the inevitable (so the story goes) by adopting a general antitechnology philosophy are called Luddites. Some defiantly pin the label on themselves, as if the name itself counted as a form of resistance. But today what does it mean to identify yourself as a Luddite?

First, it’s often an ironic gesture, even a kind of gallows humor. Many assume that to resist technology is a folly (if a noble one). The original historical Luddites in England circa 1811, the workers from whom we get the name, have mistakenly been made into the poster children for this assumption. Today “Luddite” often means “deluded technophobe,” even to some self-declared neo-Luddites. The historical record suggests something altogether different. The original Luddites were in fact skilled English laborers, mostly textile workers, who from about 1811 to 1817 organized into secret bands, sometimes referred to as an “army of redressers” under the supposed leadership of “General Ned Ludd.” They systematically smashed the kinds of machinery they saw as unfair to their craft and their trade. For the most part, this book is not about those historical Luddites. Instead, it’s more about how they have been interpreted and mythologized. It’s about how British workers in Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire and Lancashire somehow came to stand for a global antitechnology philosophy, how an anonymous collective movement came to be identified with an individualistic personal conviction. How determined weavers and cloth finishers, skilled artisans demanding fair wages and control over their own trade, were often wrongly interpreted as champions of the simple life and of nature, as voluntary primitives and Romantics. In other words, this is a book about the image and the myth of the Luddites, how the myth was made and how it was transformed over time into modern neo-Luddism.

I’m an English professor, not a historian. But I do study and interpret literary works from the past, along with their historical and cultural contexts. I’m deeply interested in both Romantic poetry (written roughly 1789-1832) and the history of technology (including its uses in the present), and I work in humanities computing as well as in literary studies. Industrialization and the story of the Luddites have always formed part of the historical context of the Romantic-period literature I study and teach. Since the mid 1990s, especially, I’ve noticed that the history of the Luddites has increasingly become a pressing “text” in itself, a topic that keeps coming up in class discussion, keeps getting cited in our reading, and seems to require interpretation in its own right. My students’ reactions to Luddite texts suggest that the Luddites were as much a part of our historical moment as of their own (circa 1811). At the beginning of the twenty-first century, the Luddites still seem like our contemporaries.

But of course they are not. The alien qualities of historical events, the vast differences between the past and the present, often provide more profound lessons than simplistic identifications or too-easy connections. The widespread use of the term “Second Industrial Revolution” is a prime example of the kind of oversimplification I have in mind, since it’s a term that assumes exactly what it should be examining: the distance traveled between then and now — the birth of the factory system and the current global economy.

So I began skeptically to think about and research the cultural history of the idea of the Luddites, how Luddism has been mediated and translated by way of various representations — novels, poetry, films, images in popular culture, activist subcultures — between 1811 and the present. My goal was to take seriously the dialectical, historical differences between then and now, between Luddites and neo-Luddites. Only in this way, I believed, could we understand the roots and specific branches of our own profound anxieties about technology.

While doing research, I asked people I talked to on campus, on the street, and at parties if they knew anything about the Luddites. More than one person thought the Luddites must have been an obscure religious sect. But many responded confidently that a Luddite is anyone who hates technology (by which in most cases they turned out to mean anyone who hates computers or doesn’t watch television or refuses to carry a cell phone). Some went further and equated Luddites with politically “green” environmentalists or anyone who longs for unspoiled nature — the rainforest instead of the city. A few mentioned Ted Kaczynski, the notorious Unabomber. Wasn’t he the most famous recent Luddite? A few fellow academics compared the Luddites to British Romantic authors such as Wordsworth and American Romantics such as Thoreau in their veneration of nature and hatred of factory smokestacks.

Some of those I spoke with, especially among my academic colleagues or younger political activists, actually knew a little about the history of the British textile workers in the early nineteenth century who were threatened with redundancy and fought back under the banner of General Ned Ludd, and many of those who knew about the original Luddites viewed them sympathetically, as doomed and tragic fighters against “progress” and the factory system of the Industrial Revolution. But even those who began with only a vague knowledge of the historical Luddites, once I began to tell about them, often leapt to identify with what they took to be the Luddite cause or philosophy (though I had been careful not to explain the events of 1811 to 1816 in those terms). Whereas I told the story of, say, Yorkshire Luddites protesting new cloth-finishing machines by smashing them with sledgehammers, they would extrapolate from this and eagerly express their agreement and solidarity with the Luddites’ “philosophy,” by which they meant that they often feel too dependent on their cars or enraged at their desktop computers. This extrapolation — so evidently asymmetrical and so forced — interested me. It seemed significant that people nowadays moved so quickly from the Luddites’ story to their own philosophy or lifestyle, and I began to realize that I was hearing in their excitement the power of a persistent myth. Through this myth, I came to understand, the Luddites get transformed into today’s neoLuddism — a kind of sleight-of-hand trick that conceals important shifts in meaning around the topic of technology.

The desire to connect with the past, to find lessons in history, is of course admirable, but simply leaping across the gap of two hundred years can only distort the history one seeks to understand. It’s a kind of short-circuit: from them to us, then to now, mechanized loom to digital computer, more willful analogy than real historical understanding and, as I began to see, also an interesting cultural symptom. “So did the Luddites” or “just like the Luddites,” so many recent explanations begin. Historical connections that seem this obvious and automatic — like the one between Luddites and neo-Luddites — often turn out to paper over a whole series of transformations and unconscious assumptions. Neo-Luddism ultimately derives from representations of the historical Luddites, texts and myths and legends, which are all we really have, as well as the not-always-conscious influence of those representations. Someone may have read or heard the basic plot of Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley, say, and also read a sonnet on nature by Wordsworth, learned about agricultural enclosures and the birth of the factory system, then put that together with a phrase about “Satanic Mills” from Blake. To them, all this is bound together as “Luddism.” They may have once read Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein (or seen one of the many movies and other cultural artifacts it inspired), and applied that story metaphorically to the recent history of the mad-scientist Unabomber, Ted Kaczynski. They may even have read the historical and political interpretations of Kirkpatrick Sale (who read E. P. Thompson’s social history) and have come to accept the vague collective wisdom that all of these cultural products and events have one thing in common: “the Luddite philosophy.”

In connecting the dots, however, they are in fact constructing the very philosophy they claim to discover in all this “history.” This book aims instead to trace the history of this history, to examine some of these popular assumptions and representations — including poetry, novels, films, works of history and popular culture — in order to look at how the idea of the Luddites has been translated over time, and in order to see what has been lost (or added) in the translation. The influence of the original Luddites is sometimes even more powerful when people have a distorted understanding of their history, what they did and what they “stood for” — which, aside from its primary political meaning (as in “take a stand”), is also a way of saying what they stand for, are signs for, what they represent.

Even many self-described neo-Luddites unwittingly participate in what historian E. P. Thompson called the “enormous condescension of posterity” by confusing the Luddites with cliches associated with Romantic poetry, for example, or by giving the Luddites too little credit for helping to make their own myths. Some assume that Luddism is just another form of Romanticism, a version of the transcendental philosophy that would rise above its own times and reject “the future,” projecting an alternative, utopian possibility that, paradoxically, involves a nostalgic return to an older way of life, one reconciling humanity and nature in voluntary simplicity.

This oddly philosophical, abstract view of Luddism has very little to do with the historical Luddites. It overemphasizes the Romantic idea of nature and the problem of individual consciousness (and “ideas” and “problems” in general) when the actual movement (or labor subculture) was all about anonymous, collective action. It ignores the engagement of the Luddites in the hotly contested moment of their own hard-fought history. In general, to Romanticize the Luddites is to read the modes of thought and expression associated with academic philosophy or the history of ideas back into a working-class subculture with its own, very different discursive traditions. More subtly, I think, it is to project a tone of earnest piety (which is how Romantic idealism is itself usually imagined) onto a movement rooted in a very different, very old, but highly adaptive guild-ethos, one that was often satirical and irreverent (think of the invention of “King” or “General” Ludd himself, who may very well have been named after a simpleton), violent in its rhetoric and as direct as a sledgehammer in its actions.

It’s not the primary purpose of this book to correct such distortions. One point I make repeatedly in the pages that follow is how inevitable are distortions of this kind in symbolic or mythic acts of transhistori- cal identification. People will make what they need to make out of the mythical past. A historian might well wish to correct such distortions of hindsight, as far as this is possible. A literary and cultural critic like me, however, wants primarily to show how those distortions reveal their own meanings, and, like others who interpret dreams and visions, wants to trace the patterns revealed in the swerves and distortions as well as in the apparently clearer memories of the past. Instead of clearing away all distortions to reveal what the Luddites really did or meant to do, I choose to ask: What do people say the Luddites did, and why do they say it (and then become convinced that the Luddites did it)? What have the Luddites meant to later antitechnologists and what do they continue to mean today? In the process, I hope to reveal the truly interesting and complex features of the Luddite legacy, which is too often oversimplified as a linear descent or the “inheritance” of a social or political legacy (to allude to the title of one of the Luddite novels I discuss below). The legacy of the Luddites includes our own meaningful (if not always conscious) distortions of Luddite history.

So what is the fascination of the Luddites? Why are they still remembered with such fervor? I think many people today look back to the Luddites to find what they are afraid we have lost forever. Mostly intellectuals or middle-class white-collar workers, today’s neoLuddites look to the Luddites for the moral authority of working-class experience, a grounding in material realities that seem increasingly elusive in today’s alienated, technologically mediated, virtual economy. Disaffected neo-Luddites also look back to the historical Luddites to identify reassuringly clear-cut targets — machines one could still destroy with a sledgehammer — in an age of ubiquitous computing, biotech agents, micro-surveillance, and data mining, a seemingly omnipresent and increasingly autonomous, “liquid” technology. Some neo-Luddites look back to the Luddites as a model of an effective subcultural style, of a “made” identity that inspired fear and hope in a national audience long before the media age. These are causes of great anxiety for neo-Luddites: the immateriality of intellectual labor, the ubiquity and autonomy of the oppressive system, and the lack of effect on the hyper-mediated public consciousness of any appeal for change or opposition. But connecting with the original Luddites is not that simple, and often involves one of several forms of distortion.

As I have suggested, neo-Luddites often Romanticize the Luddites, one form of which is to naturalize them. Given today’s concerns about the global ecology, it is common to read the original Luddites as anticipating our need to defend nature against industrial (and now postindustrial) development. Romantic poetry written at the time of the Luddites does frequently idealize nature apart from what humanity has done to it (which is one definition of technology), and it is tempting to see the Luddites’ reaction against certain developments in their trade as a reaction to the loss of nature. More generally, recent sympathizers often bring to their study of the Luddites a very modern, highly abstract concept of “technology” itself. The Luddites and their contemporaries spoke of “machinery,” and the early Victorian writer, Thomas Carlyle, for example, saw it increasing its influence over everyday life. Others began to use the term to name a problem: in Victorian parlance, “the machinery question.” But that was still a long way from the kind of inhuman and yet personified power often attributed to technology today. Modern technology is commonly seen as a monolithic, autonomous, and malevolent force with a life of its own. Technology serves to give a local habitation and a name to a host of modern evils (which are often enough very real). Since the mid-twentieth century, as writings by everyone from Jacques Ellul to Langdon Winner and Edward Tenner have argued and documented, we have increasingly spoken of technology as “wanting” something, as tending to “bite back” or “take over” or dominate us, of “threatening” to rule over us after the fashion of Victor Frankenstein’s unfortunate creature. (Mary Shelley’s novel is repeatedly cited as a prophecy of this recent condition.)

By contrast, we have to remember, the historical Luddites were themselves technologists — that is, they were skilled machinists and masters of certain specialized technes (including the use of huge, heavy hand shears, complicated looms, or large, table-sized cropping or weaving machines), by which they made their living. That living and their right to their technology was what they fought to protect, not some Romantic idyll in an imagined pretechnological nature.

Along with technology’s increasing abstraction and autonomy, many today assume its ubiquity. Technology seems to be everywhere at once, pervading every aspect of life, leaving us no refuge from e-mail or voice mail — or the vague guilt that comes from not paying attention to these things even for a weekend. A side effect of this perceived increase in the autonomy and ubiquity of technology is a general anxiety and suspicion of anything technological, an anxiety that borders on a collective form of apophenia (the tendency to see patterns everywhere), which is only one step away from paranoia.

Since the rise of what Dwight D. Eisenhower named the “militaryindustrial complex,” and especially since Hiroshima and Nagasaki, we have lived with the feeling that technology itself (autonomous and omnipresent) is a system not to be trusted, that it is out to get us, and, concomitantly, that whatever is systematic and is out to get us is likely to be insidiously technological. Anyone who has read Thomas Pynchon’s or Don DeLillo’s novels or seen reruns of the X-Files on TV or films like The Matrix or I, Robot understands this commonplace feeling. (For many, this feeling was only ironically reinforced by events such as the tech-stock bust of spring 2000, the great North American blackout of August 2003, or the almost-weekly invasions of new computer viruses.) What is less often acknowledged is that a kind of not-fully-abandoned utopian wish for an appropriate, even benign kind of technology, a machine in the garden humans could live with, lives alongside or lies behind modern neo-Luddism and, more often than not, is the symmetrical flipside to the paranoid suspicions of the neoLuddites. Many neo-Luddites react to the secrets and lies, the broken promises, of technological progress with the profound disappointment of the brokenhearted.

The chapters that follow focus on contemporary neo-Luddism (Chapters 1 and 7), on historical moments when Luddite or neoLuddite myths began to be made (Chapters 2 and 6), and on readings of literary works, films, or other cultural representations of the Luddites (Chapters 3-5). Chapter 1 begins near the present, tracing some of the forms taken by neo-Luddism in the age of the tech-stock boom and bust and antiglobalization protests. In Chapter 2 I look back at the original Luddites as makers of their own myth, as those who set in motion the process of Luddite mythmaking still at work today. Chapter 3 examines the popular association between the Luddites and Romantic poetry, where the association makes a certain limited sense but where it has nonetheless created a distorting lens through which to perceive Luddism. Chapter 4 takes up the great Romantic-period work of science fiction, Frankenstein, and tries to explain how it has come to be read as the first Luddite novel. The chapter looks at the ongoing reception of the Frankenstein myth alongside the Luddite myth — including in the numerous films and other popular variations on the Frankenstein story. Chapter 5 offers a practical survey of key novels about the Luddites, from Charlotte Bronte’s Shirley to relatively obscure Victorian fiction, twentieth-century historical novels, and one “steampunk” fantasy novel. But I also include in the list Frank Peel’s novelized local history and E. P. Thompson’s highly influential social history, which owes something to Peel and other novelizers and has been immeasurably influential on modern ideas of the Luddites. Whether modern neo-Luddites are aware of it or not, their idea of the original Luddites has been powerfully influenced by the novelization of Luddite history.

But neo-Luddism is also a product of larger cultural shifts in the very meaning of technology, including what it means to resist it. Chapter 6 locates a crucial historical moment in the 1960s, when modern neo-Luddism surfaced from the midst of the counterculture to become a powerful and popular social attitude in the culture at large. This midcentury neo-Luddism, I suggest, was born of a deep ambivalence, beginning with a counterculture already split along the line of utopian technophilia and apocalyptic technophobia — but closely and uncertainly split along this (fine) line. Finally, in Chapter 7, I return to the recent past and the present by way of a look at the Unabomber in the 1990s and beyond — a troubling exemplar of many of the characteristics of neo-Luddism in this age of terror. It is clear that any future position against technology will take shape in an environment of potential techno-terror as well as the terrifying threats posed by technology itself.

I researched this book mostly in the traditional way, by reading and taking notes (often on a computer) in historical archives and libraries in Chicago, New York, London, Kew, and Nottingham. But research these days inevitably includes the Internet, which, as everyone likes to point out — usually in an ironic voice — is chock-full of Web pages on Luddism. As this book will make clear, this is not so surprising, since modern neo-Luddites are often fighting an idea of technology from within the information culture. I have made a point of citing relevant online resources, in part to demonstrate the role the net has played in spreading the idea of Luddism. At any rate, the Internet was a logical place for me to look, since I was already online all the time, doing a great deal of my own work there, including various digital scholarly editing and humanities computing projects. Some of my research was conducted and my writing was done in coffee shops as I traveled or in a beach house in Florida, over a wirelessly networked laptop, a constant reminder of what is means today to be a “knowledge worker,” and how different that is from the kind of work done by the original Luddites.

Sometimes while researching and writing I would take a break, close the laptop, and go for a walk. Often I’d talk to neighbors, such as my friend the retired educator and organic gardener. She loves Rachel Carson’s books, monitors the population of local birds, worries about the environment, and proudly calls herself a Luddite — but, for obvious ecological reasons, also drives a complex, computerized, hybrid gas-electric car. On another walk I might drop in on another neighbor and friend, a professor who says he hates computers but of course has had to use one almost every day of his professional life. He’s another self-identified Luddite, at least in certain moods, but he put in a wireless Internet connection so he can answer e-mail and conduct research while sitting in the back corner of his lavish, nineteenth-century-style perennial garden.

I don’t mean to imply that these two thoughtful and ethically aware friends are being hypocritical — far from it. Many in my experience are, like them, Luddites in the philosophical sense, with strong convictions mixed with a sense of irony, who are pained by the compromising situations of modern society. In fact, as I began to suspect, their neo-Luddism is often a product of those very compromising situations, the result of being themselves deeply embedded within technology and uncomfortable about what that might mean. Like the enslaved podpeople of The Matrix — though somewhat less dramatically — they fear that they are being used. They engage in impassioned debate and voluntarily give up certain specific technologies — choose to do without TV or (less often, since many of them are, after all, knowledge workers) avoid computers — but they would never actually smash a machine, except perhaps as performance art. Mostly this is because they know that things are not that simple.

But I wrote Chapter 7 after talking with two antiglobalization and ecology activists. Some of the protesters in their circle may have worn “Ned Ludd Lives!” T-shirts to demonstrations, but I have absolutely no reason whatsoever to believe these two ever engaged in or condoned any sort of violence against property, whether SUVs, earthmoving equipment, power lines, or Starbucks windows. But some in their widely distributed and decentralized network may very well have at least encouraged or applauded such acts of symbolic direct action. And these two were at least at one time not necessarily opposed, in principle, to such acts.

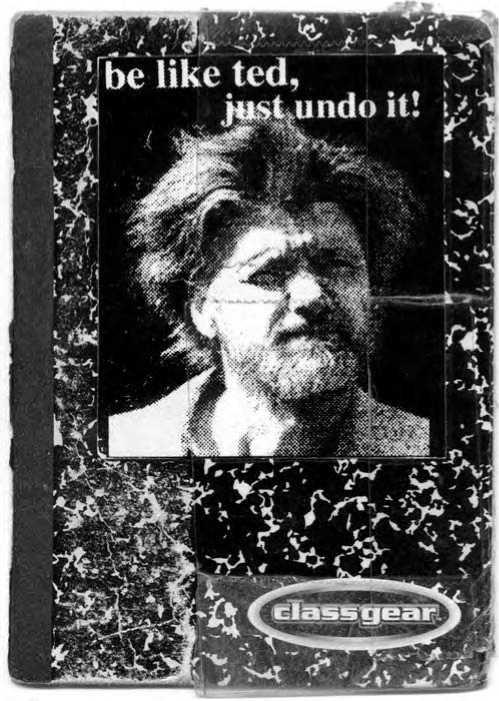

One night at the kitchen table, one of the activists told me bluntly that if I wanted the real story on contemporary neo-Luddism I should just “write to Ted” — and it took me a startled moment to realize he meant Ted Kaczynski, the infamous Unabomber. On another occasion I noticed that his friend carried a notebook with a black-and-white sticker on it: Kaczynski’s scary, bearded face (just after his arrest) looking out from beneath the words: “be like ted, just undo it!” The motto (with its ironic echo of not one but two of Nike’s ad campaigns) united the Unabomber’s neo-Luddism with the antiglobalization, anticapitalist movement. While I was immediately repulsed by the image of the serial killer on the idealist’s sticker (and by the often simplistic justifications of the murders by the Unabomber and his apologists), I was reminded of similar, deliberately offensive gestures by punk rockers in the 1970s, the use of swastikas and images of Charles Manson, for example, and I tried to understand this identification with “Ted” in context, as a dark joke, a symbolic rallying point and, at bottom, a gesture of subcultural style meant precisely to shock middle-class liberals like me. In fact, as I discovered, some form of qualified, more or less ironic, sympathy for the Unabomber can be found among all sorts of people who identify themselves as neo-Luddites, not all of them radical anarchists. I know that my friends the ecologically mindful gardener and the anticomputer professor would be repulsed by the use of the Unabomber as an icon; but on a great deal else when it comes to technology and its evils I suspect that they and the more radical neo-Luddites displaying Ted’s face would probably agree.

What about my own views on technology? Well, I do some of my work in the field of “humanities computing,” as I said, and that odd, mixed term is itself a clue to my ambivalence. Most of the time, I try to respond specifically to specific technologies. A skeptic in other things as well, I tend not really to believe in a monolithic “Technology” that one must declare oneself to be for or against. Computing, for example, can be used by global corporations to exploit consumers for profit or by governments for acts of oppression. But it is also a set of tools and media networks for studying texts and other works of art and cultural artifacts in fascinating new ways. I don’t mean that I think technology is essentially neutral. I don’t think it’s essentially anything. For me, technology is always a human system (not merely an inert “tool”) that must be understood and confronted in specific human contexts: it includes not just operators but owners, shapers, programmers, and participants. Self-conscious and knowledgeable participants are better.

My own work is deeply networked, and I think it’s important for humanists and artists and scholars to claim space within the network and help to shape it to humane ends. I mentioned my work editing digital texts, and this means that I collaborate online via e-mail and videoconferences daily or weekly. I serve on the boards of several digital projects in the humanities, which involves marking up literary texts for digital processing, carrying on e-mail discussions (and sometimes having real meetings), writing papers, and giving demonstrations about all of this, which I see as important, valuable work. Computing in general, and the Internet in particular, are changing literary and cultural studies in many positive ways, making possible new ways of producing and disseminating knowledge, introducing new forms of classroom teaching and student research, and offering one way to respond to a crisis in academic publishing by moving more scholarship online, to name just a few examples. So, yes, I have a professional investment in a generally positive view of at least information technology, which I see mostly in terms of its potential for communication and collaboration, but also for new ways of archiving, distributing, and analyzing our cultural heritage. I try to maintain a wary skepticism, however, about other ends that might be derived from the same technological means, and about ways the humanities might be absorbed into the larger information economy.

As I’ve indicated, I wrote this book in the typical twenty-first-century way, in various locations on a wirelessly connected laptop computer, in my case a battered, aluminum-skinned, Apple PowerBook, toward which I feel the usual Mac-user’s not-quite-rational affection (but that’s another topic). I like to think that the result of my double engagements, with Romantic literature and technology — which is to say the stuff of the present book — is more than a reflection of my own complicated ambivalence, but I know it is in part inevitably just that.

I hope to capitalize on that situation in the chapters that follow. I strongly suspect that my interested ambivalence isn’t unique to me, that a similar ambivalence (if with a different emphasis) lies at the heart of a great deal of recent neo-Luddism as well as recent tech- nophilia. I am not a Luddite. But I know where my neo-Luddite friends and acquaintances are coming from. I, too, am worried about the consequences of some technological experiments and believe I see through most forms of market-driven techno-hype. I share some of the neo-Luddites’ political views and get their jokes, and to some degree I share their larger concerns. I like going offline sometimes, and I really, really hate it when people talk on cell phones at the beach. More seriously, I oppose shortsighted exploitation of the environment (drilling for oil in the Alaska wilderness, for example), much of which is driven by the larger petrochemical economy. With Amory Lovins and some others, however, I think that certain strategic technologies may be the best hope for offsetting some of this environmental damage. All in all, my ambivalence toward technology is on most days somewhat hopefully inflected. I think the problems we face — many of which are indeed bound up with specific technologies and their applications — will not be solved by recourse to a mystified idea of a disembodied and all-powerful enemy called Technology. I think we can learn something from the typical “white-hat” (nonsabotaging) computer hacker’s demystifying attitude toward large systems. They are not really monolithic and all-powerful, once you get your hands on them. In the end I believe in mindfully engaging and reengineering specific technologies rather than renouncing Technology as a whole.

This general attitude toward technology, I think, I got in part from my great-grandfather. Whether or not I inherited it from him genetically, I certainly did culturally — by way of family history and legend. He was an itinerant schoolteacher and a socialist, a union organizer among the coal miners of rural southeastern Oklahoma. I’ve heard many stories (no doubt including multilayered embellishments) about the dark-lantern rallies held in his front yard, marches on Washington he joined, strikes and work actions he helped organize against the mine owners, whose technology included as many “hands” as the machinery required (and no more). He was adamantly opposed to technological “progress” and profit at the expense of these workers’ jobs (and lives). His favorite poem was Oliver Goldsmith’s 1770 “Deserted Village,” a nostalgic portrait of a fictional English village suffering changes, some of which are brought about by industrialization. I have his copy (a cheap New York pamphlet version from 1890), which I use in the classroom when I teach the poem, often alongside Luddite ballads such as “General Ludd’s Triumph.”

The thing is that my autodidact great-grandfather was also famous in his rural county as a tinkerer and inventor. He always had automatic washing machines and perpetual motion machines half-assembled in his shed. He liked to master machinery by taking it apart, was a familiar kind of do-it-yourself technologist who distrusts authority but thinks he can make something humanly useful out of technology, especially if he “repurposes” it. In other words, to commit a deliberate anachronism, my great-grandfather was a geek.

Anyway, that’s how I choose to understand him. I don’t mean to commit the same error I’ve attributed to some neo-Luddites, to find in 1920s and ’30s Oklahoma a simple mirror of my own attitudes toward technology. I know there are vast and significant differences between those coal mines and the outsourced call center in Bangalore that I may well have phoned this morning, between his Rube Goldberg machines and the networked PowerBook on which I am writing these words. On the other hand, the differences are not entirely immeasurable, and they are probably worth the effort of measuring. It’s the complexity and engagement of his attitude that I find useful as a positive example in my great-grandfather’s life, his hands-on, engaged ambivalence toward technology. This seems to me a fruitful place from which to begin pursuing the important questions of who owns and uses specific technologies and for what particular ends — which are I think the real problems of technology in the twenty-first century. So this book is dedicated to the example set by my great-grandfather — or at least by his story, his legend, as it has been told to me.

1. The Boom, the Bust, and Neo-Luddites in the 1990s

It is universally acknowledged that we live in the most technological age in history — because, it is widely believed, technology has become universal. Embodied in the Internet and bound up with the system of global capital, technology is now everywhere from San Jose to Tokyo, Bangalore to Helsinki, London to New York. How is it possible in the face of such an unprecedented and ubiquitous force to be “against” technology? What does it mean even to imagine such a position, to call yourself a Luddite at this late date in the history of technological society?

For one thing, it means you’re a neo-Luddite, someone whose choice of philosophy or lifestyle is a deliberately symbolic act, a back-formation based on the received idea of a historical labor movement. This book is about that process — the making of modern neo-Luddism out of the historical legacy of the Luddites. It begins with the original British Luddites of 1811 to 1816, who created a myth (of Ned Ludd) and then became themselves mythologized, ultimately inspiring a very different modern phenomenon, the philosophy of neo-Luddism, an idea that has flourished in America in particular. The differences between the original Luddites and today’s neo-Luddism are greater than most neoLuddites have acknowledged, and understanding those differences is crucial if we are to understand our complicated relationship to technology. My purpose is to trace the process of historical reception and distortion by which the Luddites — whose community-based actions targeted unfair labor practices — became neo-Luddism, a personal philosophy pitted against technology as an abstract force.

The book’s scope is basically transatlantic. Although forms of neoLuddism may appear anywhere in the world that technology has taken hold, for practical reasons I examine only British and American culture. I am aware that a great deal more could be said about resistance to technology in other contexts (especially in Asian contexts, for example). But my focus is on the reception history of explicit neo-Luddism, as it were, on how the Luddite name was adopted and reinterpreted, from England in 1811 to America today. Along the way I gather evidence from a wide range of cultural phenomena — poetry, novels, movies, plays, and newspaper columns, but also historical events, protest demonstrations, speeches, and subcultural styles — in short, anything that reflects (or refracts) the image of the Luddites. That image is my focus. My aim is to understand where we are now by looking at how we got here.

The 1990s Moment of Neo-Luddism

So where are we now when it comes to technology? In many ways, we are still living in the aftermath of the great Internet bubble with which the twentieth century ended. It may seem like a relatively quiet aftermath. Technology IPOs may have lost their mystique, but in the years since the bust, the idea of technology has not ceased to dominate the culture; on the contrary, it has settled in as a primary fact of life. There is now less obsessive talk about the technological future, because in many ways that future is already here, more or less, and has become a matter of regular press releases from product development offices and laboratories about the latest version of whatever many of us are already using in our daily lives.

But back in the mid-1990s, during the run-up to the boom, futures (in more than one sense) fueled both the stock market and (thanks to the media) the public imagination. Expectations were inflated right up until the boom was revealed to be a bubble. Those heightened expectations affected more than the market; they altered the collective mood of the culture. When you think about it, the techno-optimism of the 1990s now seems very strange, as if it happened to some other culture, a long time ago. It may take a special effort to remember how almost any new technology was instantly marketed as a prophetic event. For a time, the ironic term “vaporware” carried almost exclusively positive connotations. It was exciting because it was immaterial, just talk or whiteboard sketches. The mere idea of new technology not yet realized — in fact, so much the better if it was not yet realized — attracted venture capital. Even speculative information about new technology, the information about information, was treated as an important form of social capital, and the Internet was understood as the ubiquitous arena where it all played out, and as a synecdoche for global technology.[1]

Late in the decade things accelerated exponentially and even many former curmudgeons or skeptics felt compelled to “get online.” As everyone knows, that phrase meant something like “get with the program” or “get onboard.” In America it has always been easy to confuse the marketplace with the “marketplace of ideas,” and to believe that the capital of new technologies can be leveraged to reinvent the world. Being online in the 1990s involved buying stock in technology companies. Those truly in the know had (stock) options and actually referred to themselves as the “digerati” or “true believers.” Their techno-optimism as much as their technical skill set defined them as being among the truly cool. Full members of the club were said to have been “drinking the Koolaid,” an ironic reference either to the 1960s (LSD-laced punch) or to the 1970s (cyanide that killed deluded cult members), depending on your point of view.

In the midst of all this speculation and hype, just when it might have seemed that resistance was futile, a relatively small number of authors, activists, journalists, and pundits began perversely to identify themselves as Luddites or (often interchangeably) neo-Luddites. They published books and articles, held meetings, and formed into loosely overlapping coalitions that some called a movement. They claimed as their ancestors a number of earlier intellectuals who had promoted simplicity and ecology but also those textile workers in England in 1811 who first invented Ned Ludd as their mythical leader. The press treated them sometimes as a fascinating curiosity, sometimes as a movement worth watching, and more often merely as an amusing headline: “Luddites in the 1990s!”

A few years later, of course, the tech bubble burst and a kind of penitence spread among the formerly wired. By spring 2001, the idea of traditional manufacturing, “bricks and mortar,” again possessed an aura of respectability in investing circles, as if a return to rock-hard material reality could restore reason and balance to the culture. Never mind that technology companies — especially the large, established ones that had survived — continued to flourish and be taken as general economic indicators. Never mind that the downsizing that then took over was in most cases dependent on technological “solutions” to replace the redundant workers. The popular idea was that the great build-up was over for now. To many, technological skepticism in the new millennium seemed a necessary tonic, a karmic as well as economic compensation, like going to church the morning after a binge. Some degree of Luddism, mixed with equal doses of irony and schadenfreude, served — to use the language of the markets — as a “necessary correction.”

Within a few years, the correction corrected itself, to a degree. People began to buy new gadgets, if more modest ones (camera-phones or elegant iPods instead of flashy multimedia workstations), and even, cautiously, to invest again in tech stocks and to talk about the comeback of Silicon Valley. Google was in the news as an exemplary survivor with its own IPO. The prices of technology stocks across the board began to ease back up. In December 2003, a U.N.-sponsored technology conference resumed discussion of what had been an urgent agenda of the 1990s — how to wire the remaining roughly 90 percent of the world’s population still without Internet access. And of course the marketing continued apace into the new century, a series of products that became buzzwords signifying both investment and consumer appeal: WiFi, Blackberries, text messaging, voice over Internet, video games on an array of platforms, TiVo, iPods, digital cameras, and camera-phones, Weblogs and podcasts, Amazon and e-Bay, and Google’s latest data- mining applications.

The moment of neo-Luddism’s emergence, however, of its most intense self-representations, took place at the height of the boom years. The timing is not as surprising as it appeared to many observers at the time. The boom was based largely on a collective ideation (you might say hallucination) about the infinite power of technology (“You will,” one ad campaign promised vaguely). Yes, companies did lay miles of fiber-optic cable (some of it even now going unused), and they did hire programmers and create new Web sites and software applications, but it was the abstract idea of technology as an autonomous, inevitable force, as much as it was actual applications, that fueled the economic and cultural effects of the boom. High neo-Luddism was the negatively inflected mirror image of this ideation: It too was based on the idea that technology is a powerful, autonomous, inevitable force — but in this case, a force for destruction and the diminishment of humanity. Neo-Luddism was the resistance that gave the “future” its traction. If it hadn’t existed, the technophiles would have had to invent it.

Under the surface, the general reaction against the technology juggernaut was more widespread than can be measured by the columns and books and lectures of a handful of neo-Luddite authors. But those authors did provide the public voice of neo-Luddism, a self-conscious, self-styled resistance movement constructed in part out of selected and reprocessed historical facts and legends about the original Luddites. Much of the neo-Luddism of the 1990s was inspired by one book and its author: Kirkpatrick Sale’s Rebels Against the Future (1995) became a source of quotations and a rallying point for activists, because it explicitly connected late twentieth-century antitechnology sentiments to a legendary “origin”: the Luddites of 1811.[2]The book is divided into two parts: Historical Luddism and neo-Luddism, and its argument for continuity of philosophy and political purpose is implicit in that structure. It is a critique of global capitalism aimed at its cornerstone: the ideology of technological progress, which it sees as essentially unchanged since the eighteenth-century industrial era. Sale’s second subtitle is Lessons for the Computer Age. His public readings and lectures in support of the book opened with a theatrical gesture as he smashed a beige personal computer with a large sledgehammer, splintering the plastic case and CRT monitor to enthusiastic applause.

Other neo-Luddites — Sven Birkerts, David Noble, Clifford Stoll, Theodore Roszak, and Neil Postman — to varying degrees shared with Sale the basic outlook of neo-Luddism. They wrote against computers, the Internet, and the spread of hypertext browsing versus traditional reading, the supposed “death of the book.” Threats to the environment posed by technology were the chief topic of Chellis Glendenning, John Zerzan, and other green or anarchist neo-Luddites.[3] Neo-Luddism included a wide range of the technologically disaffected, an affinity group that looked for a few years like an emergent movement. But the most active promoters of the name itself and the myth of continuity with Luddism were part of the larger antiglobalization movement that reached its peak at the same moment in the mid-to-late 1990s.

Ned Ludd and the Anti-Globalization Movement

The writer Edward Tenner aptly sums up the shift from the original historical Luddism to recent neo-Luddism as “the indignation of nineteenth century producers” being replaced by “the irritation of late-twentieth-century consumers.”[4] Neo-Luddism is largely a concerned consumer’s response to the modern global marketplace, and it came to the public’s attention just as the first demonstrations of the antiglobalization movement were being televised. This movement began as a loose coalition of “green” (ecology activists), “red” (leftists), and “black” (anarchists), but there seem to have been some self-identified neo-Luddites in many of these groups and all of them identified Western technology as both cause and effect of the global dominance of capitalism.

A recent novel by Robert Newman, The Fountain at the Center of the World, effectively captures the ideological conflict of the 1990s over the connection between technology and world capital.[5] The author was in real life an activist with Reclaim the Streets and Earth First!, among other groups. His book tells the improbable, Dickensian story of two brothers born in Mexico and separated at birth. One becomes a radical saboteur and the other becomes a public relations consultant for corporations. Their paths cross, portentously enough, in Seattle, during the first major street protests against the World Trade Organization in 1999. The activist brother, Chano, bombs a pipeline belonging to a chemical company operating in Mexico, following a debate on the strategy of sabotage versus the nonviolent strategy of “speaking truth to power” (14).

On the other side, the corporate consultant, Evan, uses technology as a diversion from the ideological conquests of capitalism:

In our countries we just have to depoliticize. We make it a technical question, the great science problem of our time which, as it happens, Company X is closest in the world to solving, so just get out of its way. (71)

A brutal policeman in Mexico sees eye to eye with Evan and refers to the protesters as motivated by “Fear of the modern world, fear of change, fear of technology” (104). When one of the protesters in Seattle argues that “all the different issues are all part of the one issue” — the global dominance of capitalism — his detailed analysis of the interconnected ownership of corporate conglomerates is edited down by the TV news to a human-interest sound bite about the Red Monarch butterfly and genetically-modified crops, falsely representing him as a singleissue “green” (296-97). The neo-Luddite resistance against technology, the novel suggests, takes place in a larger context in which technology promotes global capital at the expense of nature as well as local human culture. Significantly, both sides assume that technology is the overarching force that makes possible the empire of capital.

This novel is based on the fact that the antitechnology worldview was at the center of the antiglobalization movement of the 1990s. Neo-Luddite writers and activists set out deliberately to make it so, to connect with the young and relatively unfocused protest movement, aiming to make philosophical resistance to technology one of the key planks in its emerging anticapital platform.

In April 1996, the widely publicized “Second Luddite Congress” met in Ohio. The first Luddite congress was presumably some meeting of the original Luddites in 1811, but this was just a convenient fiction, retroactively created as it were out of the need for such an origin. The 1996 meeting was organized by the Quaker Center for Plain Living and the Foundation for Deep Ecology in San Francisco, which had earlier (in 1993) sponsored a neo-Luddite group of writers and intellectuals under the direction of Helena Norberg-Hodge and Jerry Mander and inspired by a neo-Luddite treatise published as far back as the March 1990 Utne Reader, Chellis Glendenning’s “Notes toward a Neo-Luddite Manifesto.” Glendenning dramatically declared: “Like the early Luddites, we too are a desperate people seeking to protect the livelihoods, communities, and families we love, which lie on the verge of extinction.” Glendenning’s piece conveys a sense of desperation, a distrust of anything technological, and an almost theological belief that technology was already everywhere, along with an emotional, symbolic identification with the historical Luddites (“we too”). Neo-Luddism, Glendenning says, will be a “leaderless movement of passive resistance to consumerism and the increasingly bizarre and frightening technologies of the Computer Age.”[6] Therein lie key characteristics of 1990s neo-Luddism, features that differentiate it from the Luddism of 1811: passive resistance, consumerism, and an almost paranoid response to technology as a “bizarre and frightening” force.[7]

The Second Luddite Congress explicitly took up Glendenning’s charge. Its general topic, “The Second Industrial Revolution,” already indicated how neo-Luddism intended to build on a partly constructed historical precedent (“we too”). Kirkpatrick Sale addressed the Congress, reportedly opening this time not with his sledgehammer but with a vivid bit of storytelling:

In April 1812, General Ned Ludd looked across the face of England and saw, with sorrowing heart, the desperate, dire condition to which the onrushing Industrial Revolution had reduced those weavers and combers, those finishers and dyers, whose leader and whose mythical creation — he was.[8]

The whole scene, like the first Luddite congress, is openly imaginary (“whose mythical creation — he was”). The passage reads like the dialogue in a certain kind of historical fiction, where the author imagines what was said on the battlefield or in bed by more or less famous figures long dead. In Chapter 5, I cite examples of this kind of writing in actual novels (and histories) about the Luddites.

As Sale knows, almost certainly a single historical General Ned Ludd never existed. Instead, Ludd was a potent collective fiction that named a movement and united the Luddites, though some at the time, government officials — mill owners, spies — did mistake the fiction for a real revolutionary leader, just as the Luddites surely intended. Most of all, especially in Nottinghamshire and Yorkshire, where Luddism began, General Ludd was a name to conjure with. But, as Kevin Binfield has cogently demonstrated, Luddism varied regionally in its use of the central eponymous symbol.[9] In Lancashire, for example, and especially the Manchester region, Ludd was a kind of out-of-towner, an imported symbol who functioned more artificially as a device to unite the diverse interests of spinners, colliers, and other workers with those of Jacobins and radical reformers already active in the area. In Nottingham, by contrast, where Ned Ludd was “born,” a customary labor culture was already in place, a local subculture out of which he arose “organically” as a name for the movement. In Manchester, however, Ned Ludd functioned more like a “metonym,” an imported figure that the local Luddites, mostly cotton weavers, used to unify their cause (Binfield, Writings, 46-47).

Kirkpatrick Sale’s attempt to revive Ned Ludd in the 1990s in one sense merely extends this kind of rhetorical tradition, especially as it developed in the secondary wave of Luddism in the cotton districts. Nineteenth-century Manchester, with its relatively diverse and rootless new industrial society, was perhaps more like many modern neoLuddites’ own cultural contexts than was the guild-based customary labor subculture of the Nottingham weavers. For Sale, as for many Manchester radicals in the time of Luddism, the goal was to unite disparate interests under a single banner. Sale’s rhetoric in the speech reveals, as it enacts by expressing, the unifying goal of “restoring Ned Ludd to life again,” as a symbol and an imaginary comrade in arms.

Neo-Luddism came to life in the late 1990s, the collective creation of a group of activists, writers, and journalists. Its focus was on a particular version of the past, on an elegiac gesture of solidarity with long-dead workers (who were often treated as noble historical losers), a lost way of life, and their quixotic, imaginary leader. Modern neo-Luddism was born in anticipatory regret and resentment, with a doomed sense of championing a lost cause. To some degree it was (literally) an antitechnology philosophy in search of a political movement to which it could become attached.

One 1998 article demonstrates this neo-Luddite desire for a movement worthy of its philosophy. It attacks modern “Technolatry,” and optimistically describes a growing coalition of grassroots organizations. Though it cannot give an exact number of neo-Luddites, the article estimates that the numbers are growing and amount to a movement based in local grassroots organizations with a “Luddite feel,” including “homeschooling networks, watch groups protecting specific bits of wilderness or common land, activist groups confronting specific cases of industrial damage, communal gardening, and farm markets.”[10]

Not every neo-Luddite would wish to be grouped with the Christian home-schooling movement, but the populist, Libertarian bent and general cultural conservatism of this list is a reminder that the antitechnology philosophy makes strange bedfellows. Neo-Luddism seemed for a time almost capable of bringing together anticapitalist anarchists with neoconservative cultural critics and radical deep ecologists.

Five years later, a year after the stock market crash, the International Forum on Globalization held a conference at Hunter College in New York (February 24, 2001), a “Teach-in on Technology and Globalization.” The conference brought together the antiglobalization protest movement with what its organizer, the author Jerry Mander, called “the leading critics of technologies, luddites if you will.”[11] Activists shared the program with neo-Luddite authors such as Kirkpatrick Sale and Jeremy Rifkin. Speakers addressed the threat posed by the Internet, “Frankenfood” (genetically modified crops or organisms, “GMO”s), genetic engineering, nanotechnology, micromachinery, molecular computing, and the danger of runaway self-replication — “gray goo.”

The IFG conference began where the Second Luddite Congress left off and attempted to create an affinity group across the boundaries of various activist organizations. Sale’s 1995 Rebels Against the Future had claimed to notice a growing neo-Luddism, which it said

seems capable of developing along more self-conscious lines in the years ahead, particularly as the kinds of tenuous links now being made among previously separate groups grow stronger and as the sorts of issues once regarded as distinct — biotechnology and free trade, clear-cutting and tribal extinction — are increasingly seen as parts of the same rough beast. (259)

The revenant General Ned Ludd, raised from the dead in 1995 to ’96, was called on to serve as the presiding spirit of the New York meeting in 2001.

Green Ludd

Ecology groups participating in the antiglobalization coalition, such as Earth First! and the (perhaps affiliated) Earth Liberation Front (ELF), had already for years identified themselves as neo-Luddites, a shared secret handshake or inside joke among members of the resistance movement. Earth First! published books under the imprint Ned Ludd Books and sold T-shirts reading “Ned Ludd Lives!” The Earth First! Journal ran for years a column titled “Dear Ned Ludd,” which offered nuts-and-bolts, how-to advice on eco-sabotage. A compilation was published in book form as Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching, with a preface by Edward Abbey. The disclaimer on the Webpage says that the column serves only as “a forum for discussion of creative and diverse means to effectively defend the Earth.” [12]

Neither the EF! movement nor the Earth First! Journal, nor any of our friends, family, neighbors, lovers or pets necessarily encourage anyone to do the things discussed on this page, and the contents should not be legally construed as anything other than mindless entertainment. Please write to Ned via the EF!J with your top tips on ecodefense.

Despite the disclaimers, the column offers direct advice. To one correspondent upset about genetic engineering and asking what could be done, “Ned” responds,

Dear Franklin P., I think I know what you mean. It’s pretty upsetting to read about how these fascist doctors are creating glow-in- the-dark monkeys and super-trees that can withstand massive doses of Monsanto’s Roundup. As you know, arson was a favorite tactic of mine along with equipment sabotage when our merry band struggled against the Industrial Revolution in England

The columnist refers to the political and ethical questions surrounding arson, citing the ELF attacks on Vail, Colorado, as an example, but nevertheless ends by directing Franklin P. to online information on how to make an incendiary device.

Just before Thanksgiving 1998 near Berkeley, a group calling itself the “California Croppers” posted a warning flyer, then held a rowdy football game in the Gill Tract gardens owned by the University of California, wiping out a patch of genetically engineered corn. The activists’ press release said the game was an ironic “welcome-wagon gesture” aimed at the biotech firm Novartis, which had just signed a multimillion-dollar research contract with the university.

the Croppers would like to make it clear to Novartis that we will take similar actions against any future biotech experiments. Don’t let our unseriousness make you think this isn’t serious: the security of the world’s food supply is at stake. Giant corporations have set mad scientists loose upon the world, and as responsible citizens and farmers, we have no choice but to stop them [13]

The satirical yet threatening press release was signed “Captain Swing,” the name of another mythical figure, the immediate descendant as it were of General Ludd, the symbolic leader of agricultural protestors and incendiaries in England during the Swing riots of the 1830s. A letter from the original Captain Swing, sent to nineteenth-century farmers who were using a new kind of threshing machine, combines direct threat with mythic authority:

This is to inform you what you have to undergo. Gentlemen if providing you don’t pull down your meshenes and rise the poor mens wages the maried men give tow and six pence a day a day the singel tow shillings. or we will burn down your barns and you in them this is the last notis

From Swing[14]

Putting the two letters together highlights key differences between Luddites then and now across a gap of almost two hundred years and widely divergent cultural contexts. For example, whoever they are, the mysterious California Croppers are clearly not agricultural laborers. There is no direct demand for higher wages (or in fact any direct link to the issue of jobs). Also, the 1998 incarnation of Swing appears to have more formal education than his/her namesake (who was probably the creation of semi-literate farm workers), including some knowledge of nineteenth-century British history — at least the legendary history of the original Captain Swing.

That name Swing is a powerful allusion, for anyone who gets it. The intended primary audience of these letters and target of their actions is not made up of laborers and farmers, but is those who are “invested” in technology, either financially or professionally. The California Croppers are mostly speaking to the genetics researchers and officials at Berkeley and at Novartis. To achieve an ironic yet ominous effect (unserious seriousness), the Croppers deliberately align themselves with the historical legacy of agricultural protest. Among other things, this establishes their own wit and implicit right to the tradition. The name Croppers is another significant secondary historical allusion — in this case a pun — referring to the crops they threaten to destroy or “crop” from experimental fields, as well as identifying with the nineteenthcentury textile workers, croppers (cutters or finishers of large pieces of cloth) in Yorkshire especially, who were among the original Luddites.

The neo-Luddite Croppers continued to apply pressure by publishing more threatening letters. This one, for instance:

As for the security measures taken at Gill Tract, good luck! You cannot stop a determined group of people (elves? knomes?) from ridding their community of this menace. Continue to plant genetically engineered crops and take money from multinational companies and the results will be predictable.[15]

The Croppers aimed to remake a myth in order to make a difference. A game of football: What could be more harmless and communal? In the context of the agricultural Swing riots, the anti-GMO football even invoked old-fashioned sports on the village common, communal play in the preindustrial era. Canny political theater, playful seriousness, this is a teasing game of threatening more violence against property, a standard tactic in today’s mediagenic protests. The Croppers and probably overlapping groups of eco-activists working under other clever names, the Lodi Loppers, the Cropatistas, the Minnesota Bolt Weevils, and the Seeds of Resistance, see themselves as within the Luddite tradition.[16] From the original Luddites they take the idea of direct physical action as symbolism, and for them this includes games of language, disguises, and shifting identities.

Antiglobalization, Antitechnology

Speakers at the 2001 IFG conference included Kirkpatrick Sale, Jeremy Rifkin, and Langdon Winner. Stephanie Mills opened the first session by listing the alarming signs of an ecological extinction crisis and regretting the pace with which new technologies were being introduced without precaution. “No wonder there are Luddites still among us,” she remarked. Mills also cited a cautionary article recently published in Wired magazine by Bill Joy, cofounder and Chief Scientist of Sun Microsystems (an article I’ll come back to below). She endorsed Joy’s dystopian projections and joined his call for voluntary relinquishment of certain dangerous technologies, especially nanotechnology and bioengineering.

Mills introduced Kirkpatrick Sale with a joke about his recent “off-Broadway debut in the role of Ned Ludd” — referring to his computer-smashing act. Sale said that he had not brought his sledgehammer but that he would be talking about technology. He described the unintended economic and political consequences of Fulton’s steamboat technology in nineteenth-century America, concluding with a parody of the peroration of the Communist Manifesto (with Marx’s “chains” turned into personal computers): “all you have to lose are your boxes, the boxes on your desks, in your offices, in your laps. For they are all, as we now know, Pandora’s boxes.” The shift is telling: from proletarian workers shaking off the chains of capitalism — in Marx’s terms the revolutionary overthrow of “all existing social conditions” — to mostly white-collar knowledge workers giving up (or refusing to open) their computers (“Pandora’s boxes”).

These conferees were defiantly proud of their Luddism at a moment when the term “Luddite” was more often heard as an insult. At a conference of the Liberal Democratic Party in England, a prospective parliamentary candidate attacked the anti-GMO lobby and its “tabloid hysteria and cynical populism” driven by “the reborn Luddite movement.”[17] Robert Shapiro, CEO of Monsanto, said in February 2000 that the anti-GMO protestors were know-nothings and — what was worse — anticapitalists.

Those of us in the Industry can take comfort of a sort from such obvious Luddism. After all, we’re the technical experts. We know we’re right. The “antis” obviously don’t really understand the science, and are just as obviously pushing a hidden agenda — probably to destroy capitalism.[18]

In January 2001, at the World Economic Forum in Davos, Switzerland, ICC President Richard D. McCormick scornfully referred to antiglobalization protestors as “modern-day Luddites who want to make the world safe for stagnation.”[19]

Fernando Henrique Cardoso, President of Brazil, drew the familiar historical parallel between the original Luddites and demonstrators in Porto Alegre (who had attacked a Monsanto seed plant): “You can’t just smash machines. It doesn’t make sense. Imagining that you can turn the clock back in the world, stopping telecommunication and rapid financial information — that’s not possible.”[20] In response, the U.S. Secretary of Interior Bruce Babbitt counseled openness:

When thousands of young Americans and people around the world gather in the streets, it’s an enormous mistake to dismiss them as a group of overindulgent, dissatisfied technological Luddites who ought to be disregarded. That cry is a voice of skepticism about the hubris of modern technology, about science, and other forms of globalization.[21]

The antiglobalization movement was noticeably muted after the terrorist attacks of September 11, 2001. The attacks of that morning were figured by the terrorists as part of a parallel campaign against American global hegemony, and this put the movement in an awkward rhetorical position. In the ensuing “war on terror” members of al-Qaeda were often represented as Luddites (they were literally living in caves in Afghanistan at the time), just as the legitimate antiglobalist protesters had often been in previous years. The conservative consultant George Gilder, who had boosted the Internet in the 1990s, referred to the terrorists as “Osama Bin Luddites” and suggested that it was American technology that was under attack:

The Bin Luddites could no more build a 767 — much less a World Trade Center, or even a flashlight — than they can feed (never mind, free) the oppressed masses whose interests they claim to advance. But armed with hijacked technologies and apocalyptic grudges, they pose a devastating menace to all civilization.[22]

This was written in the heat of the moment. But its rhetoric is very strange indeed, its naming of fundamentalist religious terrorists after nineteenth-century working-class saboteurs, a comparison that unintentionally lends undeserved moral authority to al-Qaeda. The column is, however, further evidence of the emotional charge carried by the recognition that technology is a major force behind capital, as well as a symbolic token of American-identified “civilization” and power.

There is one demonstrable historical connection between original Luddism and the antiglobalization movement, one reason the gesture of solidarity across the intervening centuries makes political sense for the neo-Luddites. Like other militant trade movements in the nineteenth century, certain groups of the original Luddites did situate their machine breaking in a larger discursive and political context of radicalism.[23] Some openly fought against what they perceived as a larger economic system (Binfield, Writings, 40), a laissez-faire philosophy lying behind “free trade” during the Napoleonic wars.