Sylviane Gold

The Possession of Julie Taymor

The project of a lifetime pushes a prodigious artist to new levels of accomplishment

Writing about Julie Taymor should be easy, says the choreographer Garth Fagan. “Just start with genius, end with genius and make sure all the words in between are genius.” He’s at the New Amsterdam Theatre, and so is she, trying to restructure the opening scene of The Lion King—that awesome, spine-tingling, wholly dazzling opening scene—so it will fill the much larger stage of Radio City Music Hall during the Tony awards presentation.

There are a PBS film crew, a reporter and an assortment of assistants on hand to witness the rehearsal. But Taymor is focused, efficient and completely unrelenting as she tries to make sure that every inch of the stage will be filled with activity, and that both the audience in the theatre and the television viewers at home will have something special to look at as the show’s ringing African anthem segues into the bouncy pop cadences of its best-known song, “The Circle of Life.”

She is low-key and unfailingly pleasant, but no detail is too small for her attention, no disturbance large enough to distract her. And, of course, two weeks later at the Tony ceremonies, Taymor would reap the rewards of that single-minded care: a Tony and a standing ovation for her direction of The Lion King, another Tony for designing its costumes, and the thanks of all the other Lion King recipients for her vision, the vision that made the Disney production the Tony-winner for best musical as well as a runaway box-office success.

Taymor, says Fagan, who won one of those other Lion King Tonys, was born under the same Chinese astrological sign that he was—the Dragon. “We’re the ones who go for perfection,” he says. “There’s gotta be a word in the English language that describes it,” he muses, searching for a term to explain the kind of commitment she brought to The Lion King. Finally, he comes up with it: “Possessed. It was as if it had taken over her being.”

Taymor’s ability to focus is apparent when you talk to her. Once you have her attention, she is intent on every word you say, thoughtful and utterly direct in her responses. When something else is occupying her, you could just as well be on the moon. “She has that in common with several of the great artists I’ve known,” says Rick Elice, the creative director at Serino-Coyne, the company that worked on the marketing for Lion King. “She’s an incredibly intense, incredibly energized, extremely present individual. She can make you feel you’re the only person in the world.”

He sees that as part of her technique for getting the very best out of collaborators. “It’s incredibly flattering to have this bright, attractive, articulate woman telling you exactly what she wants,” says Elice. “And because she does tell you exactly, you don’t have to waste any time or energy trying to figure out how to win her approval.”

She is up-front—she is always up-front—about her belief that for women directors, honey catches more flies. “I think the veneration for the powerful male doesn’t carry over to a powerful woman,” she says as we talk in the spacious kitchen of her Lower Broadway apartment, where turn-of-the-century woodwork is a clue to the room’s previous identity as an office. “So women have had to develop the ability to conduct what needs to be conducted without head-on collisions. You can hear horror stories about powerful women who, if they were men, would be considered powerhouse genius mavericks. But it’s just not acceptable, in American culture, for a woman to come on that way. I think that closes doors for them. There is a way to be strong without being a pit bull.”

Moreover, Taymor says, women directors have never won the kind of instant acclaim that greeted, say, Peter Sellars at the start of his career. “It’s hard to know if my career would be any different if I were a man,” she says. But “there is an excitement about the 20-year-old male director, and women directors have not really been part of that club. A woman who’s that young and doing that much is still ‘risky,’ rather than the next bandwagon everyone wants to hop on. When it was JoAnne Akalaitis or Anne Bogart or whoever, they never got that kind of attention. Neither did I until I got Lion King. And yet look at what I’ve done.”

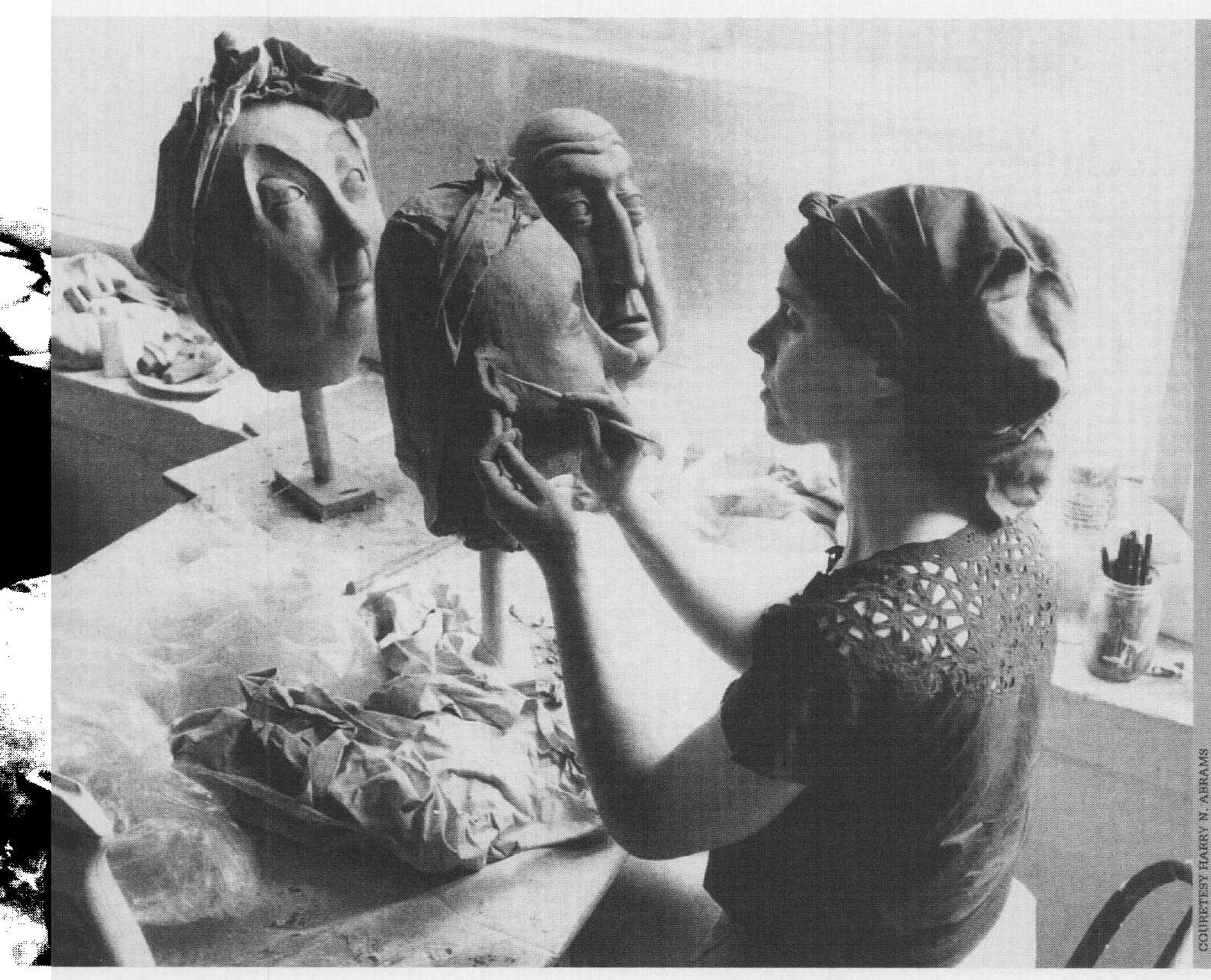

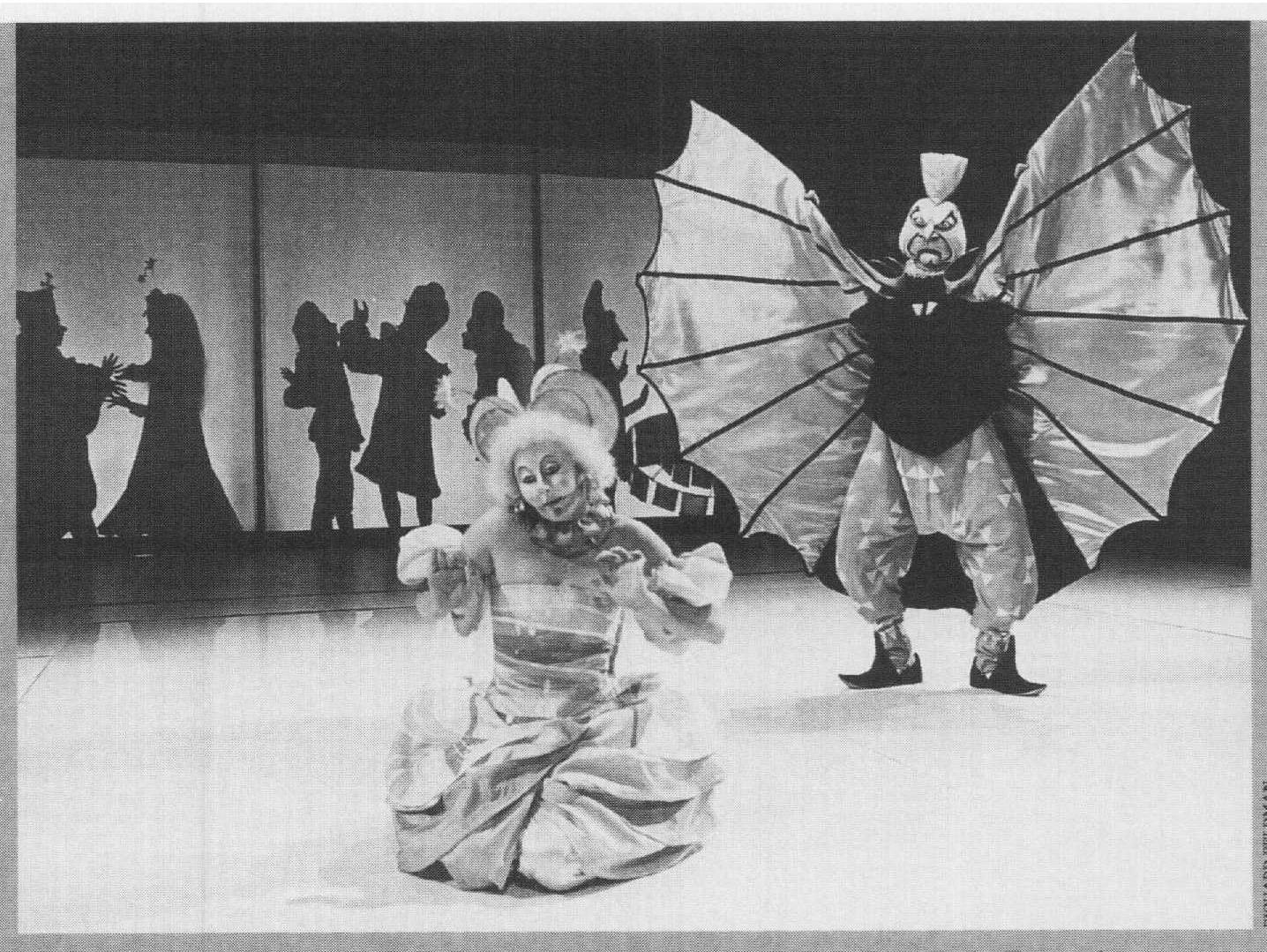

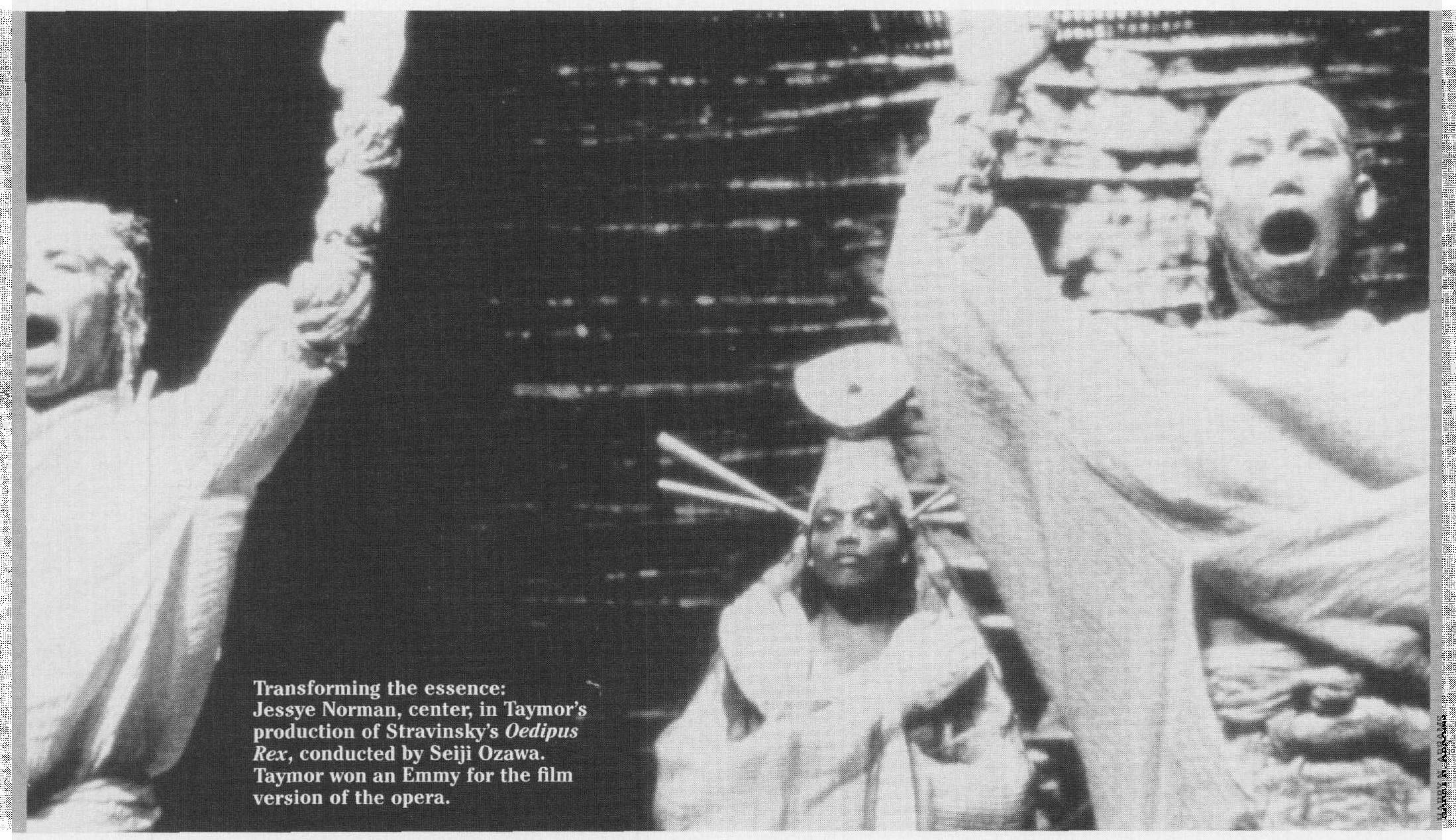

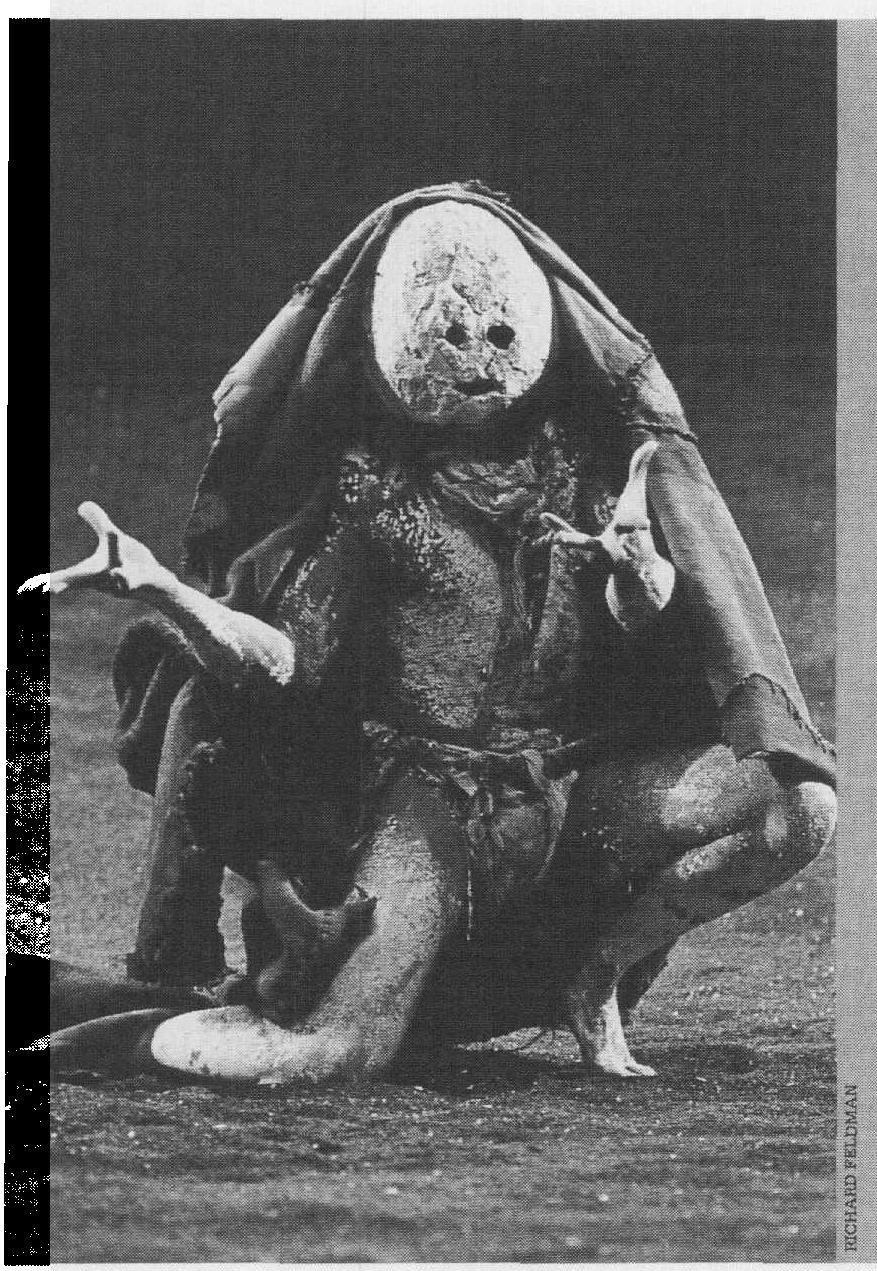

What she’s done is amass a remarkable body of work since she wrote, directed and designed her first professional theatre piece 24 years ago. It was in 1980, when she created the expressionistic sets, costumes, masks and puppetry for Elizabeth Swados’s Haggadab at the New York Shakespeare Festival, that Taymor emerged as a powerful presence in New York’s Off-Broadway theatre. Her work has garnered her packs of awards and a reputation she has taken abroad to stage prestigious operas, including Stravinsky’s Oedipus Rex with Jessye Norman. She gave Andrei Serban’s production of The King Stag at the American Repertory Theater in Cambridge, Mass., its fanciful look of a deck of cards come to life. And she directed several of the most admired of the Shakespeare plays mounted by Theater for a New Audience.

You won’t find the 49-year-old Taymor minimizing her accomplishments. “I love working with other great artists,” she’ll say, in the course of telling you who’s in the cast of the movie she’s making of her 1994 production of Titus Andronicus. “It’s all these geniuses coming together,” she’ll say, explaining why she didn’t also design the sets on Lion King. But there’s nothing superior in her attitude, and instead of coming off as conceited, she comes off as merely matter-of-fact. When you consider her thoroughly exceptional biography, it becomes obvious where the self-assurance comes from.

The first play Julie Taymor saw was A Midsummer Nights Dream, when she was six or seven. By the time she was nine, she had already acted in it, playing Hermia with the artistically sophisticated Children’s Theatre of Boston. For the backyard plays she presented with her siblings in their Boston suburb, she created props and sets as well as performing. Her parents, a Harvard Medical School professor and his wife, eventually allowed her to do some professional acting, although, she says, “They didn’t push it.”

When she outgrew the children’s company, she became the youngest member of Boston’s experimental Theater Workshop, breezing through school all the while. “It was the Grotowski era,” she says, “and we created theatre from scratch. Being part of a company like that gave me a very early understanding of how to be a creative theatremaker—a theatremaker, as opposed to a playwright or an actor.”

By the time she was 16, Taymor had finished high school and was off to Paris to study mime with Jacques LeCoq. When she thanked her parents in her Tony acceptance speech for allowing her to “play, play, play,” she wasn’t just being cute. “I was given enormous freedom as a child,” she says. “My parents allowed me to indulge my imagination and my desire to be theatrical and to create—they allowed it and supported it and never questioned my choices about going into Boston every day after school or going to Paris for a year. These are things most parents would be terrified to do with a young girl. But I know it was the right way for me.”

In Paris, she got her first exposure to masks, which would play a dominant role in her work from then on. Taymor followed that up with a work-study arrangement at Oberlin College in Ohio that allowed her to take acting classes in New York and to apprentice with the Bread and Puppet Theater, where Peter Schumann encouraged her talents as a sculptor. At Oberlin, she majored in folklore and mythology. ‘I wasn’t interested in studying theatre,” she says. “I was always kind of moving toward being an anthropologist. I loved to study the culture of other people, and that included religion and theatre, and the origins of theatre in shamanism. That provided a very good basis for the kind of work that I’ve done since.”

Back full time at Oberlin, she found herself working seven hours a day with Kraken, the company Herbert Blau created at the school in 1972. “That was probably the most formidable, exciting, creative time for me,” she says. “Seven incredible people [one of them was Bill Irwin] locked in a gymnasium in Ohio, where you could really concentrate. It was a very idealistic period, and it couldn’t have happened in New York. There would have been too many distractions. And the work was exceptional, though probably more interesting as process than as product.”

New’ York theatregoers got a chance to judge for themselves when Kraken’s The Danner Party and The Seeds of Atreus were done at the Performing Garage. Playing with Fire, the handsome Abrams book that chronicles Taymor’s pre-L/ow King career in words and pictures, has a fascinating photograph of a young but unmistakably vibrant Taymor clad in a long plaid skirt, completely immersed in the role of Tamsen Donner.

She could have continued with Blau after graduation. Instead, “excited by Indonesian shadow puppetry and masked dance and a lot of Asian forms of theatre,” she accepted a Watson Fellowship to study visual theatre in Eastern Europe, Indonesia and Japan: “So 20 years ago, I went to Indonesia for three months and stayed four years.” When the multi-ethnic troupe she put together there presented her first play, Way of Snow, she says, “It wasn’t like I was just starting. It was a sort of seminal work that put together 10 years of theatre experience.” (And it was the first in a long line of pieces that would combine theatre techniques from disparate cultures into a unique tapestry.)

Running her company, Teatr Loh, taught her how to walk the very fine line between exercising control and maintaining the refined posture expected of women in Indonesia’s tradition-bound, essentially Islamic culture. “It was very hard to do,” she says. “So it was extraordinary, to come into my own as an artist in a place like that. It was a total contradiction.”

But contradiction is par for the course for Taymor, who manages to reconcile opposites in all facets of her personality. As a theatre artist, she balances her passion for masks and elaborate costuming with a thorough devotion to actors and acting. She is a vocal and whiling poster child for the not-for-profit theatre, while simultaneously pursuing commercial work with what could be seen in some quarters as unseemly zeal. And her openness about her life in the theatre co-exists with a surprising reticence about her private life.

“Theatre,” says Taymor, “is my skin.” She tosses this off in a casual way, yet the metaphor is telling. She doesn’t say theatre is under her skin or in her skin or on her skin. When theatre is your skin, it acts both as a barrier to and a point of contact with the outside world. It is intrinsic to your being, but also just the container for it. Coming from Taymor, who chooses her imagery with extraordinary care, it betrays a lot.

Her directness fades away when she’s asked to talk about what’s under that skin. Even a routine question about her 14-year relationship wfith the composer Elliot Goldenthal produces a kind of stony avoidance. “We worked together for five years,” she says, “and then we ...” She pauses. What is she going to say? Slept together? Got married? Became a couple? Finally, it’s out: .. went to the next step.” She will go so far as to say, “We work together and we live together and we adore it.” But no further. A question about children draws a quick glance that sends an unmistakable message: that is too private for even an oblique answer.

The question of children has come up primarily because Taymor talks so long and so passionately about the kind of theatre children are entitled to see. One of the things that pleases her most about Lion King—and there are any number of things about it that please her—is that it will be for many children their first experience of theatre. But she wants it clear that it was in no w’ay designed for children. “I hate children’s theatre,” she says. “I don’t believe in children’s theatre.”

She hastens to add that she doesn’t mean to condemn the w’hole genre, or to imply that none of it is any good. But, she says, “I don’t believe in patronizing children. I personally can’t do something that is, quote, ‘for children.’ And the guys at Disney knew this. When I lived in Indonesia, they would do the Mahabharata and the Ramayana for nine hours, and the children would get all excited about the clowns and fall asleep during the philosophical sections, or they’d run around and watch the shadow puppeteer from the other side. But it was part of living with the adults. 1 like it when parents and children are there together, but 1 don’t want the parents to be bored.”

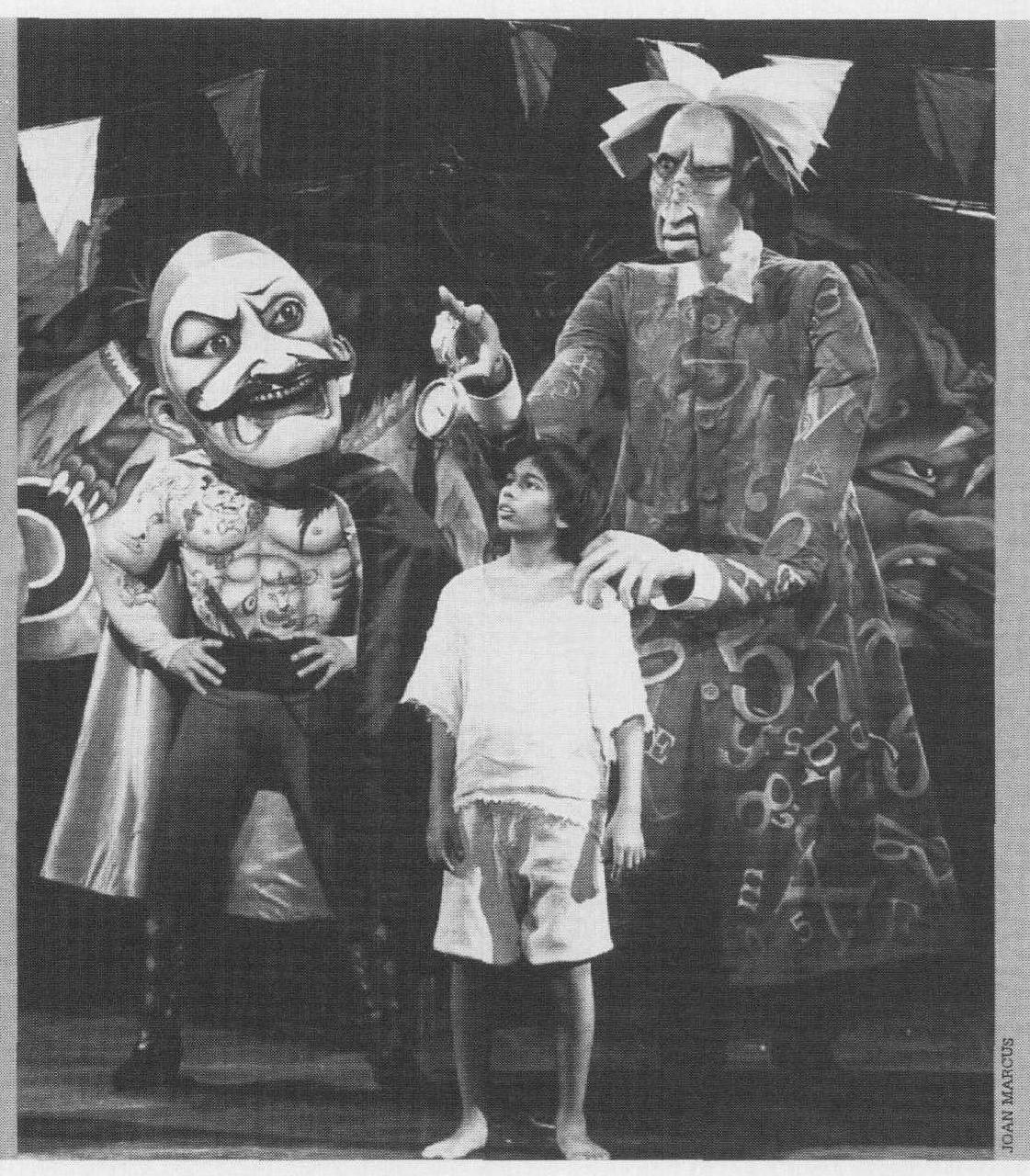

Taymor scoffs at the idea that in some way she sold out her artistic integrity by teaming up with Disney and creating the huge money-making machine that is The Lion King. Deep down, she sees it occupying a place in American culture analogous to the place the Mahabharata occupies in a Balinese village; Disney has allowed her to create a piece of theatre that can be embraced by the entire American village, that can work as high art and low, comedy and epic drama, for adults and children. And now’ that it has made her something of a marquee attraction, she is hoping that productions like Juan Darien: A Carnival Mass and The Green Bird, originally’ presented in limited runs by institutional theatres, will be brought to Broadway.

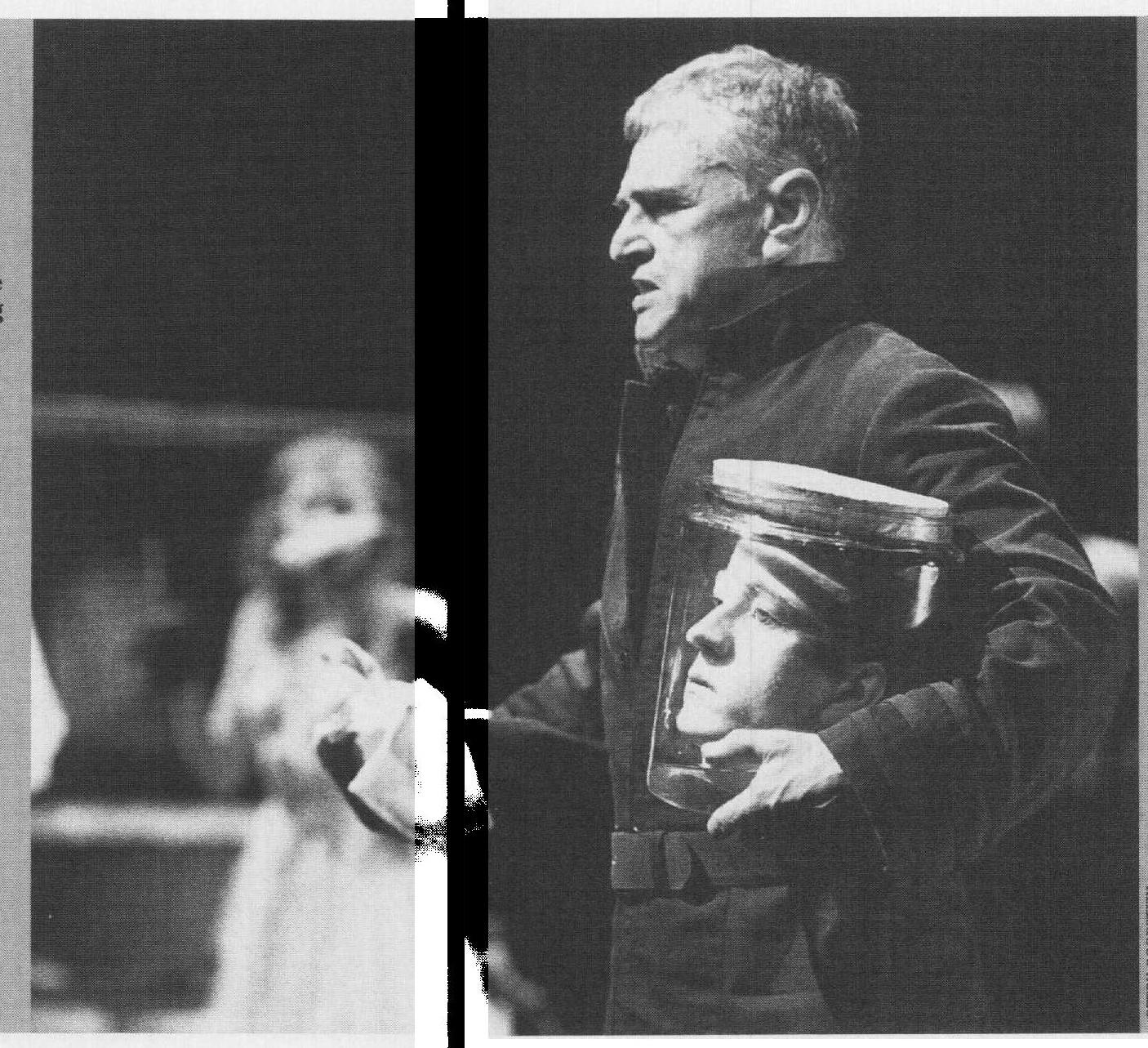

“What appeals to me as an artist about commercial producers,” she says, “is that you know they w’ant it to run. Therefore, they’re going to support it to make sure it works, so that it does run— they’re not interested in closing after three weeks or nine weeks. After two years of work on Oedipus Rex, I had two performances. Thank God there’s a movie of it, or I’d be slitting my throat. It’s hard to work on something so long and have it be a limited thing.”

Although Taymor wall announce to anyone who wi 11 listen that The Lion King could not exist if not for the not-for-profit theatre and the NEA, she doesn’t accept the notion that not-for-profit theatre is by definition not commercial. “The W’ord commercial is such a silly w’ord,” she says, “because it’s all perception. No one absolutely knows w’hat’s going to be commercial and what isn’t.” She points out that Juan Darien, her dark, poetic adaptation of a short story by Horacio Quiroga, did very good box office in France and Israel, Edinburgh and San Francisco, although an unenthusiastic Neiv York Times review killed its commercial potential when it was presented in New York last year at Lincoln Center Theater.

“I like the idea of reaching a wide audience with this kind of Work,” she says. “Any artist would probably like that. There may be some who like being only in little teeny places and just having their neighborhood see their work. But I find it extremely satisfying that little children and very sophisticated adults who hate Broadway and hate musicals like The Lion King.”

But she took on the project because she was genuinely interested in the material, not because it would make her a star. “If I find something that sparks my imagination or moves me, intellectually and emotionally, I will find a way to do it. It doesn’t mean I loved everything about the movie—it wasn’t an automatic, glove-fits-perfectly thing. The esthetic of the Disney film, as successful as it is, is not my esthetic. But I thought I knew what was powerful about it. I knew why people flocked to the movie.”

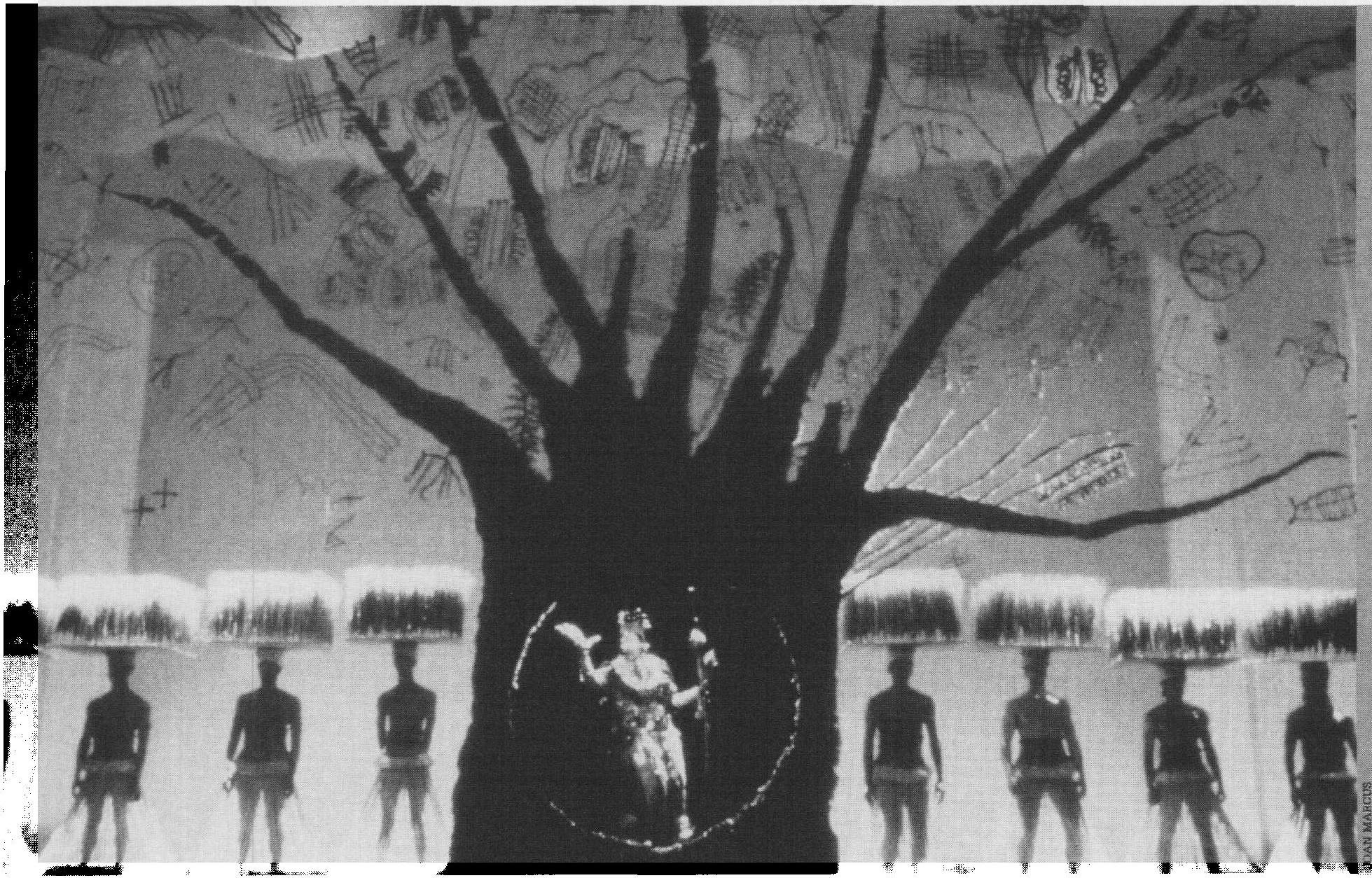

She compares its simple story to the Mababharata or the Odyssey or the Iliad: “It’s not the story,” she says, “it’s how you tell it in the theatre. Some critics don’t understand that spectacle is storytelling. They think theatre communicates only through language. When people say they’re incredibly moved and touched by the Lion King opening, it’s not just that it’s pretty and it’s a circus and you go ‘Ooh, ooh, ooh!’ Something is getting people on a very deep, very old level. I’ve watched it enough now to realize that the opening of The Lion King is really the origin of theatre. You’re there, and you’re seeing Creation again, a ritual pageant of Creation. But you’re being asked to fill in the blanks, so you’re a participant as well. It reasserts your place in your own culture, and that’s what ‘The Circle of Life’ is about.”

The Lion King arrived at the perfect time for Taymor: the five years of financial support she was awarded by the MacArthur Foundation were just ending. Taymor had no qualms about accepting the much-vaunted grant along with its popularly conferred title of “genius.” “Eliot and I had lived in one room for 10 years,” she says. She concedes that the accolade can become a problem when it arrives too soon. “But I had done enough work; I already knew where I was and what I wanted to do.”

The money helped them buy the Broadway space that houses their apartment and their two studios, and freed her to pursue projects regardless of what they paid. “And,” she says, “people start to pay attention if you have a MacArthur— it’s a stamp of approval.”

An even more visible stamp of approval came when American Express tapped her for a television commercial after the opening of Lion King. “They showed me the Vera Wang commercial they had done, and it seemed to be a very nice little promo for her. Also, American Express put money into Juan Darien. They have always been a supporter of the arts. I felt it was not an uncomfortable commercial to be associated with, and it was a nice little chunk of money.”

The money helped because even with her Lion King success, even with stars like Jessica Lange and Anthony Hopkins committed, she’s having trouble raising money for her current project. It’s the Titus Andronicus movie, and it’s yet another of her contradictions. “I’m a huge Shakespeare fanatic, because his landscape, his vision, is so vast,” she says. “He wasn’t limited by writing for the theatre. So he’s the best film writer we have. He should get one of those lifetime achievement awards.” But she’s basically committing to film her stage version, a swirling, blood-spattered phantasmagoria of horrific, often surreal black-and-white imagery.

“What I love about theatre is that it is a poetic medium. It is about finding essence, and that to me makes it such a liberating medium. I love when someone says, ‘Do a snow field,’ or, ‘You’ve got the savanna,’ or, ‘There’s a stampede,’ or, ‘This is an entire village and a child is being burned alive.’ But with a lot of my theatre projects, when I love them, I want to bring them into another medium. It’s a challenge to say, ‘Okay, what made it good in the theatre? We’ll let that go. Now, how do you take this and make it a film?’”

Sylviane Gold is a New York-based writer on the arts.