Tanya Horeck

From documentary to drama

Nick Broomfield’s and Joan Churchill’s documentary Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (UK/USA, 2003) captures the last thoughts and moments of death row inmate Aileen Wuornos, the woman who was convicted of murdering seven men between 1989 and 1990 and who was sensationally referred to in the media as ‘America’s first female serial killer’.[1] In her final interview before execution, the camera zooms in for an extreme closeup as an exhausted and angry Wuornos delivers a disturbing rant: ‘You sabotaged my ass, society. And the cops. And the system. A raped woman got executed and was used for books and movies and shit’. The next day, 9 October 2002, she was executed.

The promotional material for Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer states that it provides ‘a disturbing and humane insight into the mind of a deeply paranoid yet sympathetic person’.[2] This, too, is the apparent objective of first-time director Patty Jenkins’s much-hyped independent feature film Monster (USA/Germany, 2003). Released in cinemas a few months after Broomfield’s and Churchill’s documentary, the film, which features glamorous Hollywood actress Charlize Theron in the role of Wuornos, announces that it is ‘based on a true story’. In an attempt to humanize the ‘monster’ of the media reports, Jenkins focuses on a fictionalized version of the real-life relationship between Wuornos and her lover Tyria Moore.[3] Monster is marketed as a film ‘that burrows deep beneath the tabloid-sized headline stories to the abusive neglect, doomed romance and lost opportunities that plagued Aileen’s life’.[4]

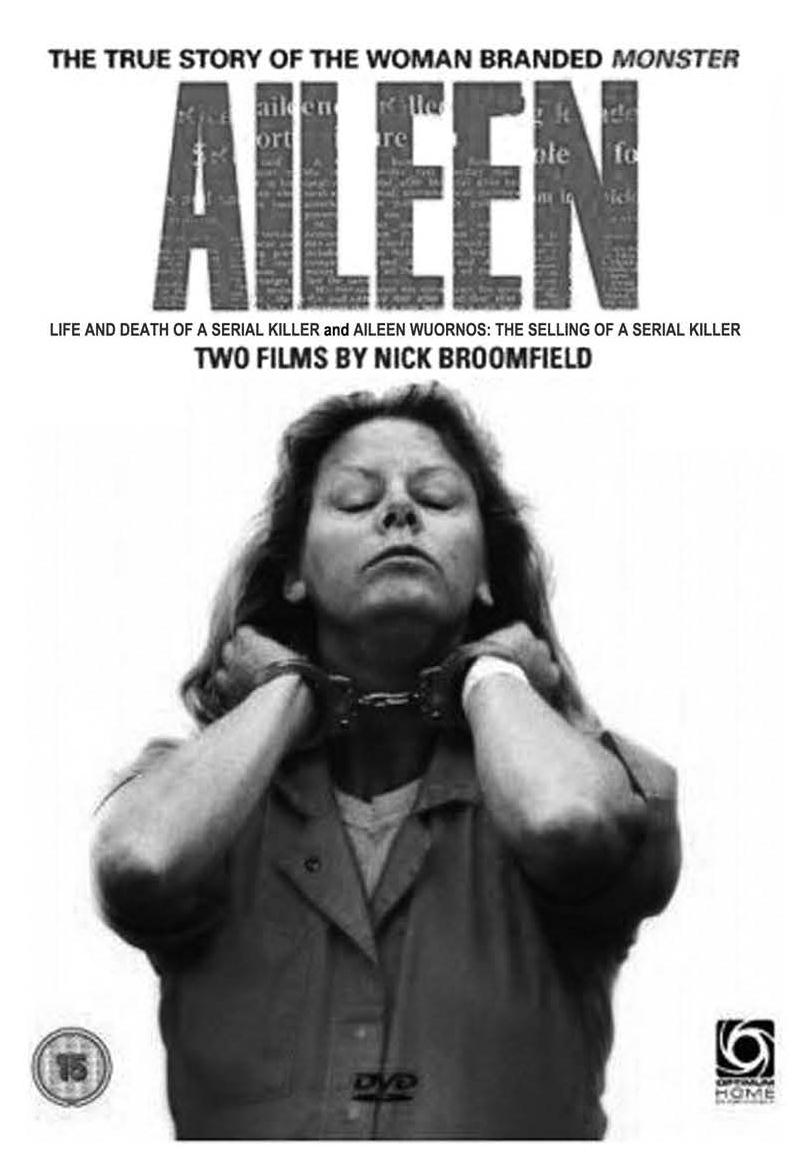

The extent to which the documentary and the feature film are packaged together is notable. Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer is presented as ‘the true story of the woman branded Monster’. The DVD box set of Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer and the earlier Broomfield documentary, Aileen Wuornos: the Selling of a Serial Killer (1992), includes the theatrical trailer for Monster. Information on the DVD also announces that ‘both films were used by Charlize Theron as the basis of her Oscar-winning performance as Aileen in Monster’. Another commercial tie-in has appeared in the form of a DVD box set that brings together Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer and Monster. In Spring 2005, Channel 4’s Film4 screened them as a double bill, showing first Monster (‘worth watching for the physical transformation alone - the preposterously beautiful Theron assumes an uncanny likeness of Wuornos’), then Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (‘For a closer look at the real Ms. Wuornos, should anyone who watches this still desire one’).[5] The cross-promotion between the documentary and the drama is thus overt.

One of the results of this corporate synergy is that spectators are invited to watch and interpret the documentary and the drama together. As seen above, the documentary advertises itself as the true story not merely of Aileen Wuornos but of the Aileen Wuornos played by Charlize Theron in Monster. The incestuous intermingling between these two films is such that Rolling Stone reviewer Peter Travers suggests that ‘Aileen makes a better Aileen than Theron’.[6] Odd though it sounds, Travers’s point is that the real Wuornos is far more compelling than the fictionalized character played by Theron, a view shared by other reviewers such as The Guardian’s John Patterson, who notes that ‘no acting can compete with such reality’.[7] He further contends that ‘Broomfield’s and Churchill’s search for truth inevitably trumps Jenkins’s fictionalization’. In contrast, David Denby of The New Yorker asserts that it takes a good actress in a good fictional piece to make us really care about the damaged Wuornos. As Denby notes: ‘This is one instance in which art clearly trumps documentary “truth”. The real Wuornos is too will-driven to show us more than one side of herself. In the end, you need a sane persona and an artist to bring out the humanity in a crazy person’.[8]

The debate about whether the documentary or the drama has the most to offer is staged as a contest between reality and fiction. A close examination of this debate reveals the extent to which the categories of reality and fiction are in fact interwoven, with interpretation of both films reliant not only on how they relate to actuality but also how they relate to each other. I am not interested in deciding which film offers us the ‘best’ depiction of Wuornos and her story, rather I want to consider how the two films trade in images of her as a monstrous other, and how that trade is revealing about the perceived status of and relationships between documentary and dramatizations of real life, and the kind of work these different forms of fact-based films are seen to perform in public culture. It is important, I argue, for the documentary and dramatic versions of the Wuornos story to be considered each in the context of the other, given their commingling and close ties.

In her book, Regarding the Pain of Others, Susan Sontag states that ‘photographs that everyone recognizes are now a constituent part of what a society chooses to think about, or declares that it has chosen to think about’.[9] She further argues that ‘collective memory is a stipulating: that this is important, and this is the story about what happened, with the pictures that lock the story in our minds. Ideologies create substantiating archives of images, representative images’.[10] From documentary to drama and back again, the story of Aileen Wuornos is now inseparably intertwined with the representative images found in these official filmic depictions of reality.[11] Through exploring the filmic evolution of her story from documentary to drama, I want to question some of the ideological uses underlying the construction of her public image in true- crime representations that lay claim to authenticity.

Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer is a documentary investigation into the weeks leading up to the execution by lethal injection of Aileen Wuornos. It can be situated in terms of a rise in the popularity of documentary filmmaking, exemplified by the massive boxoffice success of Michael Moore’s Bowling for Columbine (2002) and Fahrenheit 9/11 (2004). In his recent exploration of what might lie behind this ‘public craving for authenticity’, Blake Morrison argues that documentaries ‘give us what Hollywood won’t - fantastic stories’.[12] It is a perspective that runs through reviews that explicitly compare Life and Death with Hollywood films.

Broomfield is a British documentary filmmaker who draws on elements of the ‘traditional observational style’ but whose work is shaped by ‘personal interventions’ into the stories and the people he is documenting.[13] Although Life and Death is codirected with Churchill, Broomfield’s former partner, it is significant that she remains - with one notable exception to be discussed later - behind the scenes, operating the camera. As with his other films, Broomfield and his onscreen performance as documentary filmmaker take centre stage. A typical Broomfield film shows him making phone calls to prospective interviewees and driving in his car to track down subjects. Although his documentaries have a linear structure in so far as they are constructed around the objective of obtaining the interview, there is often a strong sense of repetition and circularity as Broomfield, in Columbo-like fashion, returns to his interviewees to clarify certain points, or to see whether he can press them to reveal more.

The cinematic trailer for Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer contains clues as to how the film positions the spectator in relation to its subject matter. After foregrounding the film’s status as a piece by an auteur, ‘A new film by Nick Broomfield’, the trailer begins by focusing on a black and white photograph of a smiling little blonde girl. We then hear Broomfield’s voice (but do not see him): ‘Aileen, let me ask you one question: do you think if you hadn’t had to leave your home and sleep in the cars it would have worked out differently?’ The screen fades to black and we are given an extreme closeup of the adult Aileen, looking manic and worn-down, as she responds:

If I could do my life all over again ... and I came from a family that was supportive, we didn’t have split sister/half sister and brother stuff and all of that, [if] it was all true blood, real blood and everything was financially stable and everybody was really tight I would have became more than likely an outstanding citizen of America who would have either been an archaeologist, a police officer, a fire department gal or an undercover worker for DEA or a ... did I say archaeology? Or a missionary.

Screen fades back to black, a soundtrack begins playing and a caption reads: ‘Aileen Wuornos was executed for the murder of seven men on October 9, 2002. This is her story.’

Situating his documentary in the tradition of a cinema of social concern, Broomfield has said that Life and Death is an attempt to bring public attention to the injustice of the death penalty and the inhumanity of the state in putting a mentally disturbed individual to death.[14] Whatever the audience may or may not know about her crimes before seeing the film, what comes across is the extent of Wuornos’s mental disturbance. The extreme closeups of Wuornos, in the trailer as well as in the documentary itself, are presented as visual verification of this disturbance. Mary Ann Doane notes that ‘the scale of the close-up transforms the face into an instance of the gigantic, the monstrous, it overwhelms’.[15] The closeups of Wuornos contribute to her monstrosity and demonstrate the degree of her anguish; they also present her face as a ‘text’ to be read.[16] There is a tension in Broomfield’s documentary between his desire to explore the psychical and social determinants of the crimes of his subject and his tendency to rely upon the visual, in the form of closeup images of Wuornos. Because Wuornos will not share details of the crimes she committed with Broomfield, or offer stories of her own history of victimization, her damaged visage and the obvious pain and anger in her voice are offered to us by Broomfield as indicators of traumatic experience.

Much of what makes Broomfield’s Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer so luridly captivating is the awareness that we are watching a woman condemned to death; an already dead woman who is going to die. As Roland Barthes notes of the photograph of Lewis Payne, who was hanged by state execution for the attempted assassination in 1865 of the Secretary of State, W.H. Seward, the emotional pull of the image comes from the knowledge that ‘he is dead and he is going to die’.[17] For Barthes, this uneasy knowledge comes with all photos and is indicative of the intimate relationship that photography has with death. Although its fundamental aim is to ‘preserve life’, the photograph ultimately ‘produces Death’: ‘Life/Death: the paradigm is reduced to a simple click, the one separating the initial pose from the final print’.[18] As if to emphasize this very point, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer begins by showing us the childhood black and white photograph of a smiling Wuornos, the same one used to open the trailer. This image of Wuornos as a child signals that the documentary will attempt to tell us a life story (the image of the smiling blonde child is an emblem of childhood innocence); it also points to the status of the documentary as a memorial to Wuornos who will be dead by the end of filming and who is thus dead when we view the documentary. The documentary is presented as a gesture of reparation and redemption, an attempt to rework and rethink aspects of the story not considered in Broomfield’s first documentary on Wuornos, The Selling of a Serial Killer.[19] Broomfield’s voiceover tells us that in this second documentary, he will explore Wuornos’s childhood in Troy, Michigan, in the hopes of ‘finding out more’.

The film’s action begins with a point-of-view shot from behind the windscreen of a car as it drives deep into the woods. A creepy soundtrack begins to play as Broomfield’s voiceover announces: ‘It was here, in these woods off Florida’s I-75, that in the space of one year the police found the bodies of seven men’. Broomfield includes a mug shot of Wuornos with the following voiceover: ‘On January ninth, 1991, Aileen Carol Wuornos was arrested in Daytona Beach Florida. She worked as a hitchhiking hooker.’

Footage of the original video of her police confession is followed by two freeze-frame shots of Wuornos in her prison attire. The first image, which features prominently in the film’s promotion, shows Wuornos in her orange prison jumpsuit, her eyes closed, her mouth turned down, with handcuffs on her wrists. Her head is thrust back and her arms are stretched back under her hair, with the handcuffs pulled taut across her neck. Her elbows are thrust towards us. This is an image of Wuornos attempting to flip her hair back, a gesture we see her performing countless times throughout Broomfield’s documentary. Despite the innocuous nature of the movement, Wuornos looks defiant and intimidating. Her skin is sallow and dull, and dark shadows play across the image. It looks as if she is trying to strangle or choke herself. As Karen Beckman notes more generally of death row photography, it ‘eerily doubles the death row prisoner’s uncertain condition of waiting, of being suspended between life and death’.[20] The second image captures Wuornos with her mouth open as she yawns. She is rubbing her eyes, which, as a consequence, appear distorted. She looks grotesque, even deformed. The freakish effect of the image is exploited by a review of Life and Death in Entertainment Weekly, which reproduces it with the following caption: ‘SCARY MOVIE: Documentary “Aileen” offers a new look at the real-world monster’.[21] These images, while only shown momentarily in Life and Death, are significant because they constitute the visual iconography of Wuornos and are frequently reproduced in reviews of the film.

The images of Wuornos are related to a long history of visual classification and documentation of criminals, but they are also startlingly reminiscent of the photographs taken by the famous French doctor and hypnotist Jean-Martin Charcot, who in late nineteenth century France ran a clinic for hysterical women. Charcot, who was interested in the visual manifestation of mental illness, compiled thousands of photos of these women, described as the ‘dregs of society’.[22] The images show closeups of the women in various contorted poses - examples include a photo of a woman with her tongue hanging out of her mouth. These images are arresting but problematic in their ‘obliteration of privacy that casts the hysteric in the role of grotesque’.[23] Such an intimate surveillance of the female face and body, as Vicky Lebeau notes, is also part of cinema’s representation of women as objects of display.[24] Like Charcot’s images of hysterics, Broomfield’s visual presentation of Wuornos is an attempt at classification, which often puts her ‘in the role of grotesque’. As the freeze-frame images are being shown to us, Broomfield’s voiceover starts: ‘The idea of a woman killing men - a man-hating lesbian prostitute who tarnished the reputations of all her victims - brought Aileen Wuornos a special kind of hatred’. Though Broomfield is reporting on how the press perceived Wuornos, and referring to the construction of her by the media as a ‘man-hating lesbian’, the deadpan reportage underscores the visual images of her as a freak.

Freaks, as Mary Russo notes, ‘are, by definition, apart, as beings to be viewed. In the traditional sideshow, they are often caged, and most often they are silent while a barker narrates their exotic lives’.[25] Broomfield’s starring role in Life and Death, along with his first-person voiceover, can produce that barker-like effect. He narrates details of her indubitably strange and tragic life, while images of Wuornos, handcuffed or shackled, are presented to us on screen. There are many images in the documentary of Wuornos raging against the world, shouting to reporters as she is bundled into cars, overlaid by Broomfield’s running commentary and narration. These documentary images play a pivotal role in the reception of Monster. Broomfield believes that his films ‘authenticate[d] [Charlize Theron’s] performance’ and it is to a discussion of debates surrounding the authenticity of that performance that I now want to turn.[26]

After a short prologue at the beginning of Monster, we are provided with a closeup of the fictionalized character of Wuornos. As her face fills the screen, she looks up at the audience. It is an important moment because the film introduces us to the downtrodden woman for whom we are to feel sympathy; and because the moment foregrounds what emerged as the central issue in popular discussions of the fiction film: the question of performance. For many reviewers, the challenge is to find the actress behind the fictional ‘monster’.[27] The urge is to look for the beauty in the ugliness, the so-called ‘truth’ behind filmic appearances.

Reviewers of Monster focus their discussion of the film almost exclusively on what has been described as ‘one of the most startling transformations in cinematic history’.[28] The blonde, blue-eyed Charlize Theron went from ‘chic model-turned-actress to desperate-hooker-turned serial killer’ by gaining thirty pounds, undergoing an intensive makeup job and wearing prosthetic teeth and brown contact lenses.[29] At the 2004 Oscar ceremony, these efforts bore fruit when she won the Academy Award for Best Actress. Critics, however, are strongly divided over her performance. On the one hand, there is Roger Ebert’s hyperbolic declaration that it ‘is one of the greatest performances in the history of cinema’.[30] On the other hand, there is the cynicism of Laura Sinagra from the Village Voice who describes it as ‘an Oscar-angling performance’. In a review titled ‘The Butcher Girl: white trash + lesbian + prostitute + serial killer = Oscar?’, Sinagra wryly notes that: ‘If you’re willing to glug a few hundred cans of Ensure, wear prosthetic teeth, conjure terminal impairment/homosexuality, and dredge up an OxyContin-slurred drawl that would scare the banjo off the inbred Deliverance boy, importance can be yours’.[31]

I agree there is something disquieting about this beauty-to-beast transformation, which points more generally to the gender, class and race politics of representations of Wuornos. What is particularly interesting to explore in this regard is how Theron’s offscreen performance as a ‘star’ feeds into interpretations of her performance as Wuornos. Theron, who appears at awards events dressed in the style of classical Hollywood cinema and who is often likened to actresses of the Golden Age of the 1930s, is in the mould of what Richard Dyer calls the ‘angelically glowing white woman’.[32] Reviews invariably describe Theron as a ‘dazzling blonde movie star’.[33] She is described as ‘svelte and luminous’,[34] a ‘silky golden South African beauty’.[35] The shocking disappearance of this beauty and its transformation into abject ‘ugliness’ are the subject of great media fascination. It is a ‘performance’, writes David Rooney of Variety, ‘that erases the actress’s creamy-skinned softness and classic beauty in a radical transformation rendering her virtually unrecognisable’.[36]

The focus on Theron’s physical transformation repeatedly returns to the fact of her whiteness; the fetishization of her ‘creamy’ white skin points to what bell hooks has described as ‘the obsession to have white women film stars be ultra white’.[37] Furthermore, the attention paid to the blonde beauty of Theron has the effect of underlining the racialized ‘white trash’ otherness of ‘hitchhiking prostitute’ Wuornos. As Annalee Newitz argues, ‘whiteness emerges as a distinct and visible racial identity when it can be identified as somehow primitive or inhuman’.[38] Referring to discussions of the hillbilly in Hollywood film, Newitz notes that the ‘hillbilly figure designates a white who is racially visible not just because he is poor, but also because he is sometimes monstrously so’.[39] Wuornos’s poverty and homelessness in both Life and Death and Monster are presented as connected to her monstrosity. Of further significance for a reading of visual depictions of Wuornos is Newitz’s argument that ‘when middle-class whites encounter lower-class whites, we find that often their class differences are represented as the difference between civilized folks and primitive ones. Lower-class whites get racialized, and demeaned, because they fit into the primitive/civilized binary as primitives’.[40] Wuornos’s class difference, in other words, is racialized and her much reported ugliness further contributes to her racial visibility as ‘white trash’. Against Theron’s movie-star luminosity, we have the documentary images of Wuornos in handcuffs and an orange prison jumpsuit, which set her apart as one of the ‘masculine, insufficiently white women on death row’ who are perceived by dominant culture as ‘born both to kill and be killed’.[41] In order to mimic the ‘insufficient whiteness’ of Wuornos, with her worn and darkened skin, Theron must make herself up in a manner that calls to mind a tradition of actors wearing blackface.

Jenkins’s retort to those who criticize her decision to cast a beautiful actress in Monster is that there simply are not women who look like Aileen Wuornos wandering around Hollywood casting agencies. ‘Hollywood is driven by beautiful faces. Always has been,’ she declares.[42] Some critics agree with this common-sense view of the casting decision and suggest it is not fair to criticize Theron’s performance on the grounds of her beauty. ‘Well, it’s not Theron’s fault that she doesn’t look as rough as Wuornos’, claims Jonathan Romney.[43] It is possible, in fact, to take a different tack and argue that Theron’s beauty is what helps to make the story of Wuornos palatable for a wide, mainstream audience. In her promotional work for the film, Theron earnestly explains her interest in the role and states why she believes Monster to be a worthwhile project, helping potential (middle-class) viewers of the film to understand the impoverished and deeply troubled nature of Wuornos’s life.

In her analysis of photographs of women on death row, Beckman argues that there are problems with the idea that beauty brings certain ethical issues to the fore and that it ‘invites us to reflect on other “less beautiful” faces’.[44] The ‘media’s care about people on death row is intimately connected to an individual’s race and gender’, she explains, with the most concern and attention directed towards those who conform to societal ideals of white female beauty.[45] Following Beckman, I would argue for the importance of interrogating some of the class and racial implications at work in discussions of Theron’s beauty. Wherever one happens to stand on the debate about the politics of Hollywood actresses ‘going ugly’,[46] it is undeniable that the extratextual discussions of Theron’s beauty are central to perceptions and interpretations of Monster.

If the beautiful Hollywood actress disappears into the figure of Aileen Wuornos, there is a sense, too, in which Aileen Wuornos disappears into the figure of the beautiful Hollywood actress. Not only did Theron make the dramatic physical transformation of which Hollywood is so fond, she had her own remarkable story of emotional transformation to accompany it. Around the time of Monster’s release, it emerged that Theron, who grew up on a farm in South Africa, had a violent childhood that culminated in her mother shooting and killing her father in self-defence when Theron, a witness to the event, was fifteen. Theron and her mother (who was never charged for the killing, which was called justifiable homicide) then moved to the USA and struggled to make the shift from rags to riches. As a profile of Theron in Hello! magazine narrativizes it: ‘The road has not always been a smooth one ... and the actress has had to overcome trauma and tragedy before finding happiness’.[47] I would suggest that the news of Theron’s violent past functions as an alternative story of female violence, one with a much more appealing ending for Hollywood than that of the Wuornos story: at the Oscar ceremony, the glamorous Theron, back to her ‘svelte and luminous’ self, arrived with her mother and her handsome fiance, the actor Stuart Townsend.[48] In an emotional acceptance speech, Theron expressed love and thanks to her mother for all the sacrifices she made in order for her to be able to attain fame and fortune in America and make her ‘dreams come true’. The disturbing questions raised in Life and Death and Monster, about violence and sexual abuse and deprivation, about poverty and the lives of the underclass, are subsumed beneath this story of the American dream come good. Broomfield picks up on this elision when he expresses disappointment ‘that there has been so little discussion of Wuornos’s life’ in amidst all the hoopla about ‘the idea of the beautiful Theron transforming herself into the overweight, boozy, psychotic Wuornos’.[49]

It is possible, however, to interpret the moment when the beautiful Hollywood actress receives her Oscar as extending both the documentary’s and the drama’s attempts to redeem Wuornos. This impulse towards redemption is apparent in the opening lines of Monster, a voiceover spoken by Theron in the role of Wuornos:

I always wanted to be in the movies. When I was little I thought for sure one day I could be a big, big star or maybe just beautiful.

Beautiful and rich like the women on TV...... Whenever I was down I would just escape into my mind to my other life where I was someone else ... I was always secretly looking for who was going to discover me ... they would somehow believe in me just enough. They would see me for what I could be and think I was beautiful They would take me away to a new life ... where everything would be different.

Collapsing Theron into Wuornos and vice versa, Monster seeks to fulfil the wish expressed here, transporting Wuornos to a fictional space where she is washed clean and renewed in the figure of the beautiful actress. A similar impulse is present in Life and Death, with its use of childhood photos of Wuornos and its evocation of the life she might have lived if she ‘hadn’t had to leave [her] home and sleep in the cars’ during the cold Michigan winters.

The play on appearance and disappearance generated by the synergy between the two films, and the crossing of the boundaries between reality and fiction, seems connected to a desire on the part of audiences to uncover or unveil the difference between Theron and Wuornos. This desire works both ways: we search not only for Wuornos in the performance of Theron, but also for glimpses of Theron in Wuornos’s performance. The ‘real’ Wuornos found in Broomfield’s documentary is scrutinized to see how the performance of the stunning actress in Monster matches up. For example, in his review of the documentary, Stephen Holden of The New York Times finds himself recalling Theron’s performance while watching Wuornos and is impressed at the recreation of ‘Wuornos’s crooked teeth’. He concludes that the ‘vocal similarity between the fictional and the actual Aileens, although not exact, is striking’.[50] A conflation of Theron and Wuornos occurs in such passages. But it is Ebert’s review of Broomfield’s documentary that is perhaps most interesting for what it has to say about the relationship between reality and performance and the collapse between the two:

Wuornos herself is onscreen for much of the film. Charlize Theron has earned almost unanimous praise for her portrayal of Aileen in the current film Monster, and her performance stands up to direct comparison with the real woman. There were times, indeed, when I perceived no significant difference between the woman in the documentary and the one in the feature film. Theron has internalized and empathized with Wuornos so successfully that to experience the real woman is only to understand more completely how remarkable Theron’s performance is.[51]

Here, reality is contrasted with performance but in a way that conflates the two categories completely: by this account, there is no longer any real or discernible difference between the actress and the ‘real woman’. What is being expressed here, I would like to suggest, is a powerful desire to be fooled by appearances, a desire to find the ‘truth’ in something fictional. The question of ‘truth’ is central to Broomfield’s documentary pursuit of his subject. Feeding into a strong cultural desire to access a terrible, unbelievable ‘real’, Broomfield’s role as filmmaker merges with those of the detective and the psychoanalyst. At the beginning of Life and Death, Wuornos tells Broomfield that she killed in cold blood and that she was lying when she said it was in selfdefence. The purpose of Broomfield’s second documentary is apparently to get Wuornos to retract this dramatic turnabout and admit to the truth of her earlier testimony - ‘What I did was what anybody else would do, I defended myself’ - something that he does rather dubiously achieve, as I will shortly discuss.

It is possible to read Life and Death in terms of the generic codes and conventions of film noir: Broomfield’s onscreen persona is that of the intrepid male investigator of the mysterious femme fatale. In this regard, it is telling that the female coauthor of the film, Joan Churchill, remains for the most part invisible in the documentary, an absence that is repeated in the promotion surrounding the film, as well as in reviews. The gender politics underlying the documentary are explicitly revealed in Channel Four’s advertising campaign, which heralded its television release. Beside a closeup of a serious-looking Broomfield runs the following caption: ‘She [Wuornos] killed the last man who got this close’. Noting that Wuornos is ‘already the subject ofan Oscar-winning film “Monster”’, the advertisement promises a thrilling night’s television viewing in which we see Broomfield getting ‘up close to the real monster’ (my italics). Although Broomfield has said he objected to this sensationalist advertisement,[52] its depiction of him as the one man who can get close to the notorious female serial killer is revealing, I think, of how the documentary plays on the gender codes of film noir. Consider, for example, this description of film noir from E. Ann Kaplan:

In the typical film noir, the world is presented from the point of view of the male investigator, who often recounts something that happened in the past. The investigator, functioning in a nightmare world where all the clues to meaning are deliberately hidden, seeks to unravel a mystery with which he has been presented. He is in general a reassuring presence in the noir world: we identify with him and rely on him to use reason and cunning, if not to outwit the criminals then at least to solve the enigma.[53]

Broomfield is certainly a ‘reassuring’ presence in the film, although he never does ‘solve the enigma’. Of Broomfield’s recent documentaries on infamous women, including Heidi Fleiss, Margaret Thatcher and Courtney Love, Jon Dovey writes that ‘there is clearly no smoking gun of “the true story” to be found The “final truth” is unattainable, cannot be expressed but can only be hinted at, evoked but never spoken.’[54] It is this ambiguity of character and motivation that is perhaps the most compelling element of Broomfield’s documentary account of Wuornos. In spite of, or perhaps because of, the amount of staging and constructing that has gone into filming, it is the unpredictable moments of emotional insight inevitably captured by the camera which are gripping. For the contemporary audiences of reality television and ‘new documentary’,[55] what is of primary interest is the presentation and transformation of reality through contrived moments of revelation. There is an interesting link to be drawn between the contemporary renegotiation of the boundaries between reality and fiction and Tom Gunning’s account of early cinema audiences. Gunning argues that early film spectators did not simply mistake film images for ‘reality’, as is often asserted. Rather, they were enthralled with the illusion of reality on offer. As Gunning writes, in the early ‘cinema of attractions’, the ‘spectator does not get lost in a fictional world and its drama, but remains aware of the act of looking, the excitement of curiosity and its fulfillment’.[56] Gunning’s discussion of the contradictory role of the spectator, who ‘vacillates between belief and incredulity’[57] is significant for interpreting the play on questions of appearance/disappearance, truth/falsity and reality/ fiction, which appears in the exchange between Life and Death and Monster.

It is important, for example, to note the extent to which the interviews in Life and Death are presented to us as a dramatic staging of reality. Wuornos is shown preparing herself for interviews. ‘Let me do this thing over one more time’, she tells Broomfield as she readies herself, fixing her microphone and bending over to flip her hair out of her face. In her interviews with Broomfield, Wuornos delivers performances, not in the sense of a ‘“trained” demonstration’, but in the sense that there is a ‘conscious desire to present, explain and justify [herself] through a display of action to the camera and, by implication, to the 58 viewer’.

One scene is especially relevant in thinking through the issue of truth and performance in Life and Death. It is Broomfield’s second interview with Wuornos at Broward Prison. A buoyant Wuornos is happy to see ‘Nick’, as she always calls him. During the interview, Wuornos becomes angry about the delays in her execution: ‘I’m so fucking mad I can’t see straight. They’re daring me to kill again’. The camera is then turned off, or at least Wuornos thinks it is turned off. We are presented with a shot of the wall, which Broomfield voices over with the following: ‘Aileen waited till she thought we weren’t filming to talk about the murders’. The next shot is of Broomfield’s profile as he leans closer to the pane of glass separating him from Wuornos, and we hear her whisper that it was, in fact, self-defence but that she cannot admit to it on tape because the officials are ‘too corrupt’: ‘They will never do me right. They will just fuck me over some more so I can only go to the death’. As Wuornos goes to leave the interview room, Churchill appears onscreen, holding the camera, and the two women acknowledge each other. Wuornos, still unaware that Churchill has been secretly filming her, says it was nice to see her.

Broomfield says that they did not set out to trick Wuornos deliberately, but felt it was important the ‘truth’ be heard. Still, it is a difficult moment, and many writing in the field of documentary ethics would take issue with the decision to film Wuornos without her knowledge.[59] Others might contend that at least Broomfield and Churchill openly show us the documentary process by revealing the ‘covert’.[60] What I find most interesting to examine, however, is how the above scene positions the audience, and how that relates to the distinctions between truth and performance, reality and contrivance at work in the documentary. With our knowledge that the camera remains on, we are placed in a conspiratorial relation to Broomfield; what Stella Bruzzi notes of Broomfield’s documentary on Heidi Fleiss is applicable here, we are ‘lulled into a sense that we are indeed, once more, to occupy the privileged position of those whom Broomfield lets in on the act’.[61] The question of performance is central: the film suggests that it is only when Wuornos stops performing for the camera that the ‘truth’ emerges. At the same time, however, Churchill’s sudden and unexpected appearance in the documentary is an unintended moment of disruption, which calls attention to the constructed nature of Broomfield’s onscreen persona as the lone male investigator. It reminds the viewer of a world beyond the screen to which we are not privy and underscores the fact that Broomfield’s persona is, as Bruzzi notes, ‘an act, a ploy on [his] part to get the material he wants’.[62]

Joel Black argues that ‘while reality has never been more in demand, it has also never been more at issue. Reality in liberal, democratic, mass-mediated societies no longer is self-evident, but is constantly contested and up for grabs’.[63] Our yearning for the real is powerful, if elusive, so this is why, perhaps, in reviews of the films, Wuornos is found to be as good or less good and either more or less ‘real’ than Theron and vice versa. ‘It isn’t merely that movies compete with reality’, suggests Black, but that ‘movies compete with other movies (and studios with other studios) in rendering an authentic - that is, graphic - view of reality’.[64]

The presentation - or more to the point the sensationalization - of reality in both documentary and drama revolves around Wuornos’s class background. For if images of Wuornos as poor ‘white trash’ were used to vilify her in the popular press, in the filmic renditions of her story they are used to generate sympathy, albeit in troubling ways. By uncovering her violent past, Broomfield shows compassion for Wuornos as a damaged and abused person but at times the relationship between his voiceover and the images he shows presents ‘her working-class family background and physical traits as evidence of her capacity for crime’.[65] When he visits Wuornos’s childhood friend, Dawn Botkins, Broomfield comes across a series of family photographs. These photographs of Wuornos’s family members are screened as Broomfield reads what develops into a catalogue of horror:

Aileen aged four. Her brother Keith aged six. Aileen’s biological mother Diane who abandoned Aileen when she was just six months old. Aileen’s father Leo who was convicted of kidnapping and sodomizing an eight-year old boy. He committed suicide in prison. Aileen’s grandfather Lowry who she called dad and who is rumoured to be Aileen’s biological father. He abused both Aileen and her mother. Aileen aged 13 when she got pregnant and had a baby boy that was put up for adoption.

However sympathetic Broomfield is to his subject, a certain sense of ‘us and them’ emerges at such moments. In her essay, ‘A question of class’, Dorothy Allison writes of the intense pain she experienced when she overheard people talk about her and her poor white Southern family in the context of ‘they’. ‘They, those people over there, those people who are not us, they die so easily, kill each other so casually. They are different. We, I thought. Me.’[66] Wuornos appears to experience a similar pain and there are poignant moments in the documentary when she wants to ‘set the record straight’, insisting that she came from a ‘good, clean family’. Although there is little question that Wuornos had a very troubled and indeed tragic upbringing, the problem is that Broomfield does not openly discuss or engage with questions of class. Paige Schilt persuasively argues in her incisive analysis of Broomfield’s first documentary on Wuornos, The Selling of a Serial Killer, that he tends to reify rather than explore the discourses of class, gender and sexuality that frame Wuornos’s story. As Schilt suggests, ‘He does not provide viewers with the tools to critique the gender, sexual, and class biases embedded in dominant media images of Wuornos’.[67] The omission ofan analytical or critical framework effectively reinforces dominant ideas of Wuornos as a ‘white trash’ woman who killed or a woman who killed because she was ‘white trash’.[68]

There is occasionally also a tabloid tone to Broomfield’s voiceover of Wuornos’s life story, which can come across as glib:

Aileen, aged sixteen, left Michigan and travelled down here to Florida looking for sun and friends. She was young and pretty and earning good money as a hooker but with a violent temper and soon in trouble. She knocked one man out with a beer bottle, another with a billiard ball. She particularly liked it here near Daytona Beach. This is one of the motels, the Fairview, where she frequently stayed. It was all so new and exciting.

This is the stuff of true crime and pulp fiction and the risk is that it tends towards ‘lurid redescription’ rather than critical investigation.[69] The images that Broomfield chooses to signify Wuornos’s lifestyle and sexual relationship can also be problematic. When recounting her relationship with Tyria Moore, Broomfield tells us that their ‘favourite pastime was drinking beer and firing their pistols in the wood’; the documentary then supplies us with the ideologically loaded visual signifier of a broken television set on a stump in the forest.

Although it is not discussed in reviews of the film or in the promotional material, the love story in Monster is similarly framed through the issue of what Lisa Henderson calls ‘class pathology’.[70] The class difference between Wuornos and her girlfriend, Tyria Moore, was referred to quite extensively in the real-life case and appeared to influence the police’s treatment of Moore (the idea being that she was a ‘good’ girl from a middle-class family, whereas Wuornos was a ‘bad’ girl who came from a long line of poor trash). Monster continually reaffirms the fact that the women come from very different social positions; Selby, the fictional character based on Moore but whose name is changed in the film for legal reasons, is surrounded by people who care about her and stays in a comfortable, suburban home, whereas the character of ‘Lee’ (short for Aileen) is a ‘street person’ (the term used to describe her in the film) who has no family and keeps what few possessions she has in a storage garage.

A waif-like Christina Ricci plays the role of Selby. The visual contrast between the fictionalized character of Selby and Wuornos’s real-life lover could not be more extreme, and given the extraordinary lengths to which Theron was transformed to look like Wuornos, it seems a significant casting decision. In real life, Wuornos’s girlfriend was her physical approximation and the two women strongly resembled each other. However, in Monster, the difference in physical size between the actresses is considerable, with a hulking Theron towering over Ricci in every scene. Theron is tall and chunky with long dirty blonde hair; Ricci is small and dark-haired and dressed to appear cute and boyish. According to Jenkins: ‘It wasn’t about making someone look just like her real girlfriend, it was about capturing that essence. To put another actress next to Charlize and to have her missing teeth and be fat I just thought would push the audience away.’[71] Too much sameness between the women might be threatening therefore the difference has to be exaggerated so that spectators can distance themselves from the odd couple. At the same time, the difference is never too extreme and Lee and Selby’s relationship works according to familiar paradigms readily recuperable by a middle-class, heterosexual audience.

If Life and Death is film noir, then Monster is pure melodrama, firmly establishing itself as a women’s film with a focus on romantic love. Judith Halberstam has noted how Boys Don’t Cry (Kimberly Peirce, 1999) turns the complex true-life story on which it is based into a universal ‘streamlined humanist romance’.[72] The same can be said of Monster. The trailer shows several images of Lee and Selby in romantic clinches, accompanied by the following captions on screen: ‘Every Chance. Every Risk. Everything She Did. She Did for Love.’ Monster is shorn of many details of the actual story such as the police investigation, the intense media interest in the case, the various trials and Wuornos’s twelve years on death row. What we are left with is the love story between Lee and Selby and the depiction of Wuornos’s killing spree, with the film making associations between the sex and the death.

The title Monster is meant to refer to the media’s construction of Wuornos, an issue the film itself does not explore in any detail. There is also a poetic reference to a ‘monster’, which is the name of a giant ferris wheel that Lee fantasized about going on as a little girl. I would argue, though, that the title Monster primarily signals the film’s status as a monster movie in the way of a film such as King Kong or Frankenstein, with Lee as the tragic monster who horrifies us but for whom we are made to feel sympathy. As James Snead suggests, monster movies are interesting to analyze for the collective fears and fantasies they reveal about a culture; the figure of the monster functions as scapegoat and repository for a number of guilty desires. Ultimately these desires are dealt with and contained through the death of the monster at the film’s conclusion.[73]

Discussing the real-life case, Lynda Hart notes how Wuornos was reluctant to conform to the theory that she was a victim of past childhood trauma. Hart writes that ‘there is something fascinating, and unnerving, in [Wuornos’s] implacable self-defense, her disregard for a linear narrative of a life’s trajectory that begins with victimization and ends in retaliation’.[74] It is therefore interesting to explore how both documentary and drama are keen to develop just such a linear tale of victimization and retaliation. Broomfield and Jenkins present Wuornos as a traumatized victim. Where the fiction film visualizes moments of traumatic experience and death, the documentary must evoke trauma in other ways,[75] through the use of confession, testimony and the exploration of what Mark Seltzer in Serial Killers calls ‘lethal spaces’.[76] Broomfield includes footage of himself driving up and down highways past restaurants and service stations, evoking what Seltzer has referred to as the ‘pathologized experience of public spaces’ exposed in stories of serial killers.[77] In the scenes in the woods and in the images of the streets and houses of the area where Wuornos grew up, as well as on the highways where she met with strange men, ‘the landscape becomes imbued with meaning; in this case memorials for traumatic events, possibly deaths’.[78] Scenes shot from the interior of houses that Broomfield visits to interview various people from Wuornos’s past, such as her biological mother who abandoned her when she was still a baby, also strongly evoke personal and familial trauma.

As a fiction film, Monster is able to represent traumatic experience much more explicitly. The defining trauma of the film, which is presented early on, is Lee’s rape in the woods by one of her johns. The scene is based on Wuornos’s courtroom testimony regarding the first man she murdered, Richard Mallory. In Monster, Mallory is depicted as a violent, psychotic rapist who knocks Lee unconscious and ties her up on the front seat of the car. When she awakens, he rapes her with a tire iron. He pours cleaning fluid over her genitals and is about to rape her again, when Lee breaks loose and shoots him. In keeping with other recent representations of rape in contemporary cinema, this disturbing visualization of sexual violation is designed to show the graphic brutality of the crime.[79] The rape is the primal scene of the film and it overlays the other scenes in which Lee murders her johns. I would suggest that the rape scene in Monster largely derives its dramatic charge from its close association with Wuornos’s powerful courtroom testimony of the rape, as presented in Broomfield’s documentary. That testimony is rendered here in visual detail and offered up to us as a truthful spectacle of the real.

In Life and Death, Broomfield’s persistent attempts to get Wuornos to admit to the ‘truth’ culminate in his final interview with her the day before her execution, where his investigative technique is more aggressive than previously. As in other Broomfield documentaries, ‘the moments when “Nick gets angry on camera” are deliberately constructed as narrative climaxes’.[80] When he questions her on why she killed the seven men, an exasperated Wuornos tells him: ‘Oh you are lost Nick. I was a hitchhiking hooker, running into trouble. I’d shoot the guy if I ran into trouble, physical trouble.’ When Broomfield insists on pressing further: ‘but how come there was so much physical trouble - because it was all in one year - seven people in one year?!’ Wuornos snaps. The interview ends in dramatic fashion with Wuornos in an extreme closeup in which she speaks directly both to Broomfield and to the camera: ‘You’re an inhumane bunch of fucking living bastards and bitches ........................................................................................................................

You don’t just take human life like this and sabotage it and rip it apart like Jesus on the cross and say thanks a lot for all the money I made off you and not care about a human being and the truth being told.’ Wuornos cuts the interview short and gives the camera the finger. Broomfield shouts out that he is sorry as Wuornos is led away by prison guards.

The scene is distressing. Broomfield himself has described it as ‘biblical’ and states that he finds it difficult to watch: ‘it’s hard not to feel the comment is aimed at you [the viewer]‘.[81] It is perhaps in order to cope with the ramifications of that sentiment that the next shot brings us back to a familiar position - behind the windscreen of a car, Broomfield’s favoured point of view shot. Dawn Botkins, Wuornos’s childhood friend, tells Broomfield that Wuornos is sorry: ‘She didn’t give you the finger. She gave the media the finger and the attorneys the finger ... she knew if she said much more it could make a difference at her execution tomorrow so she just decided not to.’ The moment seems intended to assuage Broomfield and the viewer that Wuornos’s rage was not directed towards him (or us). This sense that we are somehow outside of the ghoulish media exploitation of her life and death, as evidenced in the tabloid television footage that announces her execution as a ‘Date with Death’, is reinforced in the next image, a shot of the prison in the early morning on the day of execution. Broomfield drives by the crews of media teams waiting to report on her death. Focusing on the glare of the media lights and the journalists talking into their microphones, the suggestion is that Broomfield is distanced from this brouhaha, even though shortly afterwards he will release his documentary as a package with a major feature film. Indeed the last time we see Broomfield in the documentary he is wearing his trademark white shirt surrounded by a media scrum eager to hear his story. At the documentary’s conclusion, music begins playing and the following caption comes onscreen: ‘Aileen requested to be cremated with her bible and to have this song played at her wake’. The final image is of Dawn Botkins walking towards her house as a caption tells us that ‘Dawn scattered Aileen’s ashes here at her farm’.

In contrast to this personalized tableau, the conclusion of Monster occurs in the public space of the courtroom. Lee breaks down in tears as Selby testifies against her. As Lee receives a sentence of execution, she has a final rant against the judge and society for sending a ‘raped woman to death’. Her ironic voiceover lists a number of platitudes, including ‘Love conquers all’ and ‘Every cloud has a silver lining’. She looks directly at the audience. ‘Hmph. They gotta tell you something’. The prison guards lead her through a doorway into a glowing white light. A black caption comes on screen: ‘Aileen and Selby never spoke again’. And then the final printed message: ‘Aileen Wuornos was executed on October 9th, 2002, after 12 years on Florida’s Death Row’.

The dramatic ending of Monster universalizes Wuornos’s story as a tale of love and betrayal. Despite its earlier exploration of trauma, Monster ultimately suggests that Lee is executed because of her great love for Selby whose demands were what pushed her to commit the string of murders in the first place. The excessive demands of queer love, as presented in Monster, lead to death and destruction. Where Broomfield presents his film as an anti-death-penalty polemic, it is interesting to note that Jenkins has stated she is not against the death penalty per se and that in the case of Wuornos, there was no other way out: ‘it was a ruined life, it was not salvageable’, she is quoted as saying.[82] Monster glosses over and aestheticizes Wuornos’s death (represented symbolically by the white light). And, while Monster elsewhere seeks to go where the documentary cannot, using the force of fiction to imagine scenes from Wuornos’s final days with her lover,[83] it is significant that it concludes with Theron performing or ‘impersonating’ one of Wuornos’s courtroom outbursts (included in Broomfield’s documentary). As throughout the film, Theron’s performance here works through repetition and reiteration. Following Judith Butler’s theory of performativity,[84] one might argue, finally, that Theron’s ‘uncanny’ impersonation of Wuornos’s gestures and mannerisms brings Wuornos into being - another reason, perhaps, why her performance is seen as so ‘real’. But by choosing to replay this courtroom moment in the film’s final scenes, Monster also firmly situates Wuornos in the realm of the law, a gesture that would appear, on some level, to reconsolidate the legitimacy of the legal order and its containment of Wuornos as violent other. For while Monster invites us to feel sympathy for the ‘creature’ that has lumbered before us on screen, committing a number of sexual and social transgressions, any sympathy is contained by the ‘otherness the monster represents’.[85]

Acknowledgements

I am indebted to Tina Kendall for her thoughts on the relationship between reality and fiction, redemption and performance and the ‘cinema of attractions’. Thanks also to Catherine Silverstone, Sarah Barrow and Hugh Perry for their helpful comments.

[1] Wuornos argued that it was not the number of men she killed that was important, but ‘the principle’, the fact that on each occasion she was defending herself. See Lynda Hart, Fatal Women: Lesbian Sexuality and the Mark of Aggression (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1994), p. 136, for arguments about why Wuornos does not fit the profile of a serial killer.

[2] Blurb included on the back of the DVD of Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer and Aileen Wuornos: the Selling of a Serial Killer, distributed by Optimum Releasing.

[3] Promotional synopsis of the film found on http:// www.monsterfilm.com.

[4] Blurb found on back of the DVD for Monster, distributed by Metrodome. & The Author 2007. Published by Oxford University Press on behalf of Screen. All rights reserved. doi:10.1093/screen/hjm012

[5] See The Guide section of The Guardian, 30 April 2005, p. 65.

[6] Peter Travers, ‘Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer’. URL: http://www. rollingstone.com/ reviews/movie/_/id/5947795?rnd = 1112614407687&has [accessed 20 April 2005].

[7] John Patterson, ‘The ugly chair’, The Guardian, 23 January 2004.

[8] David Denby, in Decca Aitkenhead, ‘The gift of a killer’, The Guardian, 27 March 2004.

[9] Susan Sontag, Regarding the Pain of Others (London: Penguin, 2003), p. 76.

[10] Ibid., p. 77.

[11] See Paul Ward’s interesting discussion of the relationship between Life and Death, Monster and the made-for-television movie Overkill, in Documentary: the Margins of Reality (New York, NY and London: Wallflower Press, 2005), pp. 40-8.

[12] Blake Morrison, ‘Who needs fantasy? How the documentary came back to life’, The Guardian, 5 March 2004, pp. 4-6.

[13] Nick Broomfield, in Kevin MacDonald and Mark Cousins (eds), Imagining Reality: the Faber Book of Documentary (Boston, MA and London: Faber & Faber, 1996), pp. 364-5.

[14] See Nick Broomfield’s discussion of the documentary in Jason Wood, Nick Broomfield: Documenting Icons (London: Faber & Faber), pp. 211-34.

[15] Mary Ann Doane, Femmes Fatales: Feminism, Film Theory, Psychoanalysis (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1991), p. 47.

[16] Ibid., pp. 47-8.

[17] Roland Barthes, Camera Lucida (London: Vintage, 1993), p. 95.

[18] Ibid., p. 92.

[19] Broomfield’s first documentary on Wuornos explores the attempts made by the unscrupulous, including her lawyer and her adoptive mother, to profit from the story of her crimes.

[20] Karen Beckman, ‘Dead woman glowing: Karla Faye Tucker and the aesthetics of death row photography’, Camera Obscura, vol. 19, no. 1 (2004), p. 11.

[21] Owen Gleiberman, ‘Serial killer’.

URL: http://www.ew.com/ew/ article/review/movie/ 0,6115,576609 1 0,00.html [accessed 20April2005].

[22] Ilza Veith, in Vicky Lebeau (ed.), Psychoanalysis and Cinema: the Play of Shadows (New York, NY and London: Wallflower Press, 2001), p. 14.

[23] Lebeau, Psychoanalysis and Cinema, p. 18.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Mary Russo, The Female Grotesque: Risk, Excess and Modernity (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1995), p. 80.

[26] Broomfield, in Wood, Nick Broomfield, p. 232.

[27] Thomas Doherty suggests that this impulse continues to the end of the film, when, after the credits, ‘one half expects the actress to appear, Scooby-Doo-like, and rip off the mask to expose the babe beneath the prosthetics’. See Doherty, ‘Aileen Wuornos superstar’, Cineaste, vol. 29, no. 3 (2004), p. 4.

[28] Gleiberman, ‘Serial killer’.

[29] Rob Mackie, ‘Monster’, The Guardian, 30 July 2004.

[30] Roger Ebert, ‘Monster: Theron makes ordinary movie extraordinary’. URL: http:// www.rogerebert.suntimes.com/ apps/pbcs.d11 /article?AID=/ 20040330/REVIEWS/403 [accessed 5 April 2005].

Laura Sinagra, ‘The Butcher Girl: white trash+lesbian+ prostitute+serial killer=Oscar?’, URL: http:// www.villagevoice.com / generic / show print.php?id 49687&page=sinagra&issue [accessed 4 April 2005].

<br><br>Richard Dyer, in Beckman, ‘Dead woman glowing’, p.6.

<br><br>Stephanie Zacharek, ‘Monster’. URL: [[http://www.salon.com/][http://www.salon.com/]] ent/movies/ review/2003/12/ 25/monster/print.html [accessed 4 April 2005].

<br><br>Jenny McCartney, ‘Terrified and terrifying: cinema’, Sunday Telegraph, 4 April 2004.

<br><br>Liam Lacey, ‘Monster’, The Globe and Mail, 16 January 2004.

<br><br>David Rooney, ‘Monster’, URL: [[http://www.variety.com/][http://www.variety.com/]] index.asp?layout awardcentral2004& content=jump&nav= re [accessed 5 April 2005].

bell hooks, ‘The oppositional gaze: black female spectators’, in Amelia Jones (ed.), The Feminism and Visual Culture Reader (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2003), p. 97.

Annalee Newitz, ‘White savagery and humiliation, or a new racial consciousness in the media’, in Annalee Newitz and Matt Wray (eds), White Trash: Race and Class in America (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1997), p. 134. Ibid.

Ibid.

Beckman, ‘Dead woman glowing’, p. 11.

[42] Patty Jenkins, in Aitkenhead, ‘The gift of a killer’.

[43] Jonathan Romney, ‘Dying is an art. And she does it very well: Monster’, The Independent, 4 April 2004, p. 18.

[44] Beckman, ‘Dead woman glowing’, p. 16.

[45] Ibid., p. 9.

[46] There is a recent history in Hollywood of beautiful actresses ‘deglamorizing’ themselves for roles; for example, Cameron Diaz in Being John Malkovich (Spike Jonze, 1999) and Nicole Kidman in The Hours (Stephen Daldry, 2002). In recent years, several Hollywood actresses have won Best Actress Oscars for their portrayals of poor white women who are victims of violence. In addition to Hilary Swank’s performance in Boys Don’t Cry, other prominent examples include Jodie Foster in The Accused (Jonathan Kaplan, 1989), and Swank again for Million-Dollar Baby (Clint Eastwood, 2005). I do not wish simply to conflate these individual films, but it is important to consider what kind of public fantasies are being woven around the figure of the poor white woman in contemporary popular cinema.

[47] ‘Charlize Theron profile’. URL: http://www.hellomagazine.com/ profiles/charlizetheron/ [accessed 7 April 2005].

[48] B. Ruby Rich makes a similar point in her discussion of Hilary Swank’s Academy Award winningperformance as a transgender individual in Boys Don’t Cry. As Rich suggests, the difficult questions explored in the film about gender and identity are somewhat undermined when, at the Academy Awards, ‘the boyish Brandon transmutes back again into sexy babe as Swank shows up in form-hugging dress, batting her eyes and thanking her husband. The good news? That was all acting. The bad news? The same.’ See Rich, ‘Queer and present danger’, Sight and Sound, vol. 10, no. 3 (2000), p. 25.

[49] Broomfield, in Steve Rose, ‘I thought I was really watching her’, The Guardian, 24 March 2004.

[50] Stephen Holden, ‘Real life behind “Monster”: a serial killer’s last days’, The New York Times, 9 January 2004.

[51] Ebert, ‘Monster’.

[52] See Broomfield’s discussion of this in Wood, Nick Broomfield, p. 230.

[53] E. Ann Kaplan (ed.), ‘The place of women in Fritz Lang’s The Blue Gardenia’, Women in Film Noir (London: British Film Institute, 2000), p. 81.

[54] Jon Dovey, Freakshow: First Person Media and Factual Television (London: Pluto Press, 2000), p. 35.

[55] See Stella Bruzzi’s discussion of contemporary documentary in New Documentary: a Critical Introduction (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2000).

[56] See Tom Gunning, ‘An aesthetic of astonishment: early film and the (in)credulous spectator’, in Leo Braudy and Marshall Cohen (eds), Film Theory and Criticism: Introductory Readings (New York, NY and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1999), p. 825.

[57] Ibid., p. 823.

[59] Brian Winston, ‘The tradition of the victim’, in Larry Gross, John Stuart Katz and Jay Ruby (eds), Image Ethics: the Moral Rights of Subjects in Photographs, Film, and Television (New York, NY and Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1988), pp. 34-57; Calvin Pryluck, ‘Ultimately we are all outsiders: the ethics of documentary filmmaking’, in Alan Rosenthal and John Corner (eds), New Challenges for Documentary (New York, NY and Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1988), pp. 255 - 68.

[60] Jay Ruby, ‘The ethics of image making; or, “They’re going to put me in the movies. They’re going to make a big star out of me...”’, in Rosenthal and Corner (eds), New Challenges for Documentary, p. 210.

[61] Bruzzi, New Documentary, p. 178.

[62] Ibid., p. 171.

[63] Joel Black, The Reality Effect: Film Culture and the Graphic Imperative (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2002), p. 15.

[64] Ibid., pp. 15-6.

[65] Miriam Basilio, ‘Corporal evidence: representations of Aileen Wuornos’, Art Journal, vol. 55, no. 4 (1996), p. 58.

[66] Dorothy Allison, Skin: Talking About Sex, Class and Literature (London: Pandora, 1995), p. 13.

[67] Paige Schilt, ‘Media whores and perverse media: documentary film meets tabloid TV in Nick Broomfield’s Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer’, Velvet Light Trap, no. 45 (Spring 2000), p. 57.

[68] See Schilt, ‘Media whores’, for an excellent analysis of how Broomfield’s first documentary, The Selling of a Serial Killer, actively constructs an idea of Wuornos as ‘white trash’, pp. 58-9.

[69] Mark Seltzer, Serial Killers: Death and Life in America’s Wound Culture (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1998), p. 8.

[70] See Lisa Henderson, ‘The class character of Boys Don’t Cry’, Screen, vol. 42, no. 3 (2001), p. 302.

[71] Cited in The Making of a Monster included on Monster DVD.

[72] Judith Halberstam, ‘The transgender gaze in Boys Don’t Cry’, Screen, vol. 42, no. 3 (2001), p. 298.

[73] James Snead, White Screens/ Black Images: Hollywood from the Dark Side (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1994).

[74] Hart, Fatal Women, p. 152.

[75] The most interesting recent work on documentary considers its status as an art form uniquely poised for an exploration of trauma. As Anita Biressi notes, what documentary has in common with ‘true crime and talk show confession’ is ‘an attempt to construct a topography of unrepresentable elements such as interior states: memory, trauma and fear’. See Biressi, ‘Inside/out: private trauma and public knowledge in true crime documentary’, Screen, vol. 45, no. 4 (2004), p. 405 and Heather Nunn, ‘Errol Morris: documentary as psychic drama’, Screen, vol. 45, no. 4 (2004), pp. 413-22.

[76] Seltzer, Serial Killers, pp. 45-8.

[77] Seltzer, Serial Killers, p. 304.

[78] Biressi, ‘Inside/out’, p. 407.

[79] Recent representations of rape are notable for their explicitness. Gaspar Noe’s Irreversible (2002), for example, includes a nine- minute rape scene, which was passed by the British Board of Film Classification on the grounds that it is a ‘harrowing and vivid portrayal of the brutality of rape’ and is ‘not designed to titillate’. See ‘BBFC passes Irreversible uncut for adult cinema audiences’. URL: http://www.bbfc.co.uk/ website/2000Aboutnsf/News/ $first?OpenDocument&AutoFra... [accessed 3 November 2002]. The idea is that the spectacle of rape is so real, so harrowing, that it demands to be seen, reinforcing a powerful conception of cinema as a medium that educates and transforms the spectator. See a more detailed exploration of this issue in my work Public Rape: Representing Violation in Fiction and Film (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 2004).

[80] Dovey, Freakshow, p. 32.

[81] Broomfield, in Wood, Nick Broomfield, p. 231.

[82] Jenkins, in Aitkenhead, ‘The gift of a killer’.

[83] Working on the premiss that ‘truth’ can be derived from fiction, Jenkins draws on a familiar rationale for docudrama in explaining Monster’s project: ‘It was a period of time a documentary could never make a film about’. A narrative film, suggests Jenkins, is best equipped to ‘really examine what happened’ and delve into the time (1989-90) when Wuornos was living with her girlfriend and began killing men. See The Making of a Monster, on the Monster DVD.

[84] See Judith Butler, Gender Trouble: Feminism and the Subversion of Identity (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1990) and Bodies That Matter: On the Discursive Limits of ‘Sex’ (New York, NY and London: Routledge, 1993).

[85] Snead, White Screens, p. 23.