Ted Kaczynski

Kaczynski and his lawyers

Kaczynski had a close relationship with his legal team — especially attorney Judy Clarke, to whom he wrote a letter trying to explain why he became the Unabomber. But he felt betrayed when his lawyers pursued a mental health defense and has distrusted the legal profession ever since.

Letter #1

Judy, there is a question you’ve raised with me a couple of times that I tried to answer as best I could, but I didn’t feel that I did a very good job of answering it. Since the issue is one that you seem to find disturbing, I’ll try to answer your question more clearly now.

You asked how someone like me, who seems to be sensitive to other people’s feelings and not vicious or predatory, could do what I’ve done. Probably the biggest reason why you find my actions incomprehensible is that you have never experienced sufficiently intense anger and frustration over a long enough period of time. You don’t know what it means to be under an immense burden of frustrated anger or how vicious it can make one.

Yet there is no inconsistency between viciousness toward those whome one feels are responsible for one’s anger, and gentleness toward other people. If anything, having enemies augments one’s kindly feelings toward those whome one regards as friends or as fellow victims.

I want to make it clear that I am offering these remarks not as justification, but only as explanation. I don’t expect you to feel that my actions were justified.

Do I feel that my actions were justified? To that I can give you only a qualified yes. My feelings at a given time depend in part on whether I am winning or losing. When I am losing (for example now, when the system has me in jail) I have no doubts or regrets about the means that I’ve used to fight the system. But when I feel that I’m winning (for example, between the time when the manifesto was published and the time of my arrest), I start feeling sorry for my adversaries, and then I have mixed emotions about what I’ve done.

Thomas Mosser, for instance, was a practitioner of what I consider to be the slimy technique of public relations, which corporations and other large organizations use to manipulate public opinion, but it does not necessarily follow that he was ill-intentioned. He may simply have felt that the system as it exists today is inevitable, and that he could accomplish nothing by going into another line of work. And of course his death hurt his wife and children, too.

So I can’t blame you for feeling troubled about what I’ve done. In fact, I respect you the more because you have raised this difficult question, even though it makes me uncomfortable to try to answer it. I suppose that to sympathize with my actions one has to hate the system as I hate it, or at least one has to have experienced the kind of prolonged, frustrated anger that I’ve experienced. I think you have the good fortune never to have gone through anything like that.

I’m grateful that, in spite of your feelings about my actions, you are working so hard to win my case for me.

Not as justification, but only to put things in perspective, I offer the following comment.

During the latest U.S. invasion of Panama at least 300 civilians (some say 1,000 or more) were killed through the actions of the U.S. forces. Yet, as far as I know George Bush has never expressed any remorse or even any mixed feelings about ordering the invasion. (He didn’t know in advance that civilians would be killed, but he must have realized that there would be a very high risk of civilian deaths, since that sort of thing is commonplace in war).

What was George Bush’s motive for ordering the invasion? Certainly it was not to topple a nasty dictator, since there are lots of equally nasty dictator, since there are lots of equally nasty two-bit dictators that the U.S. doesn’t bother about. Bush claimed his motive was to stop Noriega’s participation in drug trafficking, but it seems to be agreed that by the time the invasion Noriega was no longer of central importance to the drug trade, and obviously this dictator’s removal has done nothing to slow the flow of drugs to the U.S.

Speculations as to Bush’s real motive include; a desire to gain political advantage by carrying out a successful military operation; or a desire to install in Panama a government favorable to the United States’s retention of control over the Canal Zone when the current treaty expires. But I’ve heard of no plausible motive for the Panama invasion that would justify 300 civilian deaths.

Yet mainstream opinion does not regard Bush’s action as criminal. Why? Because his way of killing people is conventionally acceptable in our society.

Letter #2

December 25, 1996

To All Members of my Defense Team

I want to thank you all for the beautiful dictionary that you gave me as a Christmas gift. I very much appreciate your kindness. And I would like to repeat my thanks for the hard work that all of you are doing on my case. I hope that all of you are enjoying your holiday season.

Gratefully,

Ted Kaczynski

Letter #3

Evidence of “winding down” the operation:

1. Most, if not all, of the kinds of pipes used in devices had been disposed of.

2. Steel rods for making plugs for pipes had been disposed of.

3. Of the type of copper tubing used in devices, all had been disposed of except a few short pieces that were in containers of copper scraps slated for disposal — I think. I did have a lot of ⅜” (outside diameter) copper tubing left, but it was of a thicker-walled type not used for any devices or even tests.

4. Most of the redwood I had was burned.

5. All the mahogany I had was burned.

6. The remains of the other types of wood used in devices had all been burned.

7. Except for one small piece that got left out, all my magnesium had been melted down with aluminum.

8. The aluminum bar from which I cut pieces for building triggers had been melted down.

9. My supply of 1/32” steel sheet had been disposed of.

10. I had disposed of the very heavy copper wire (about ⅛” thick or more) that I used not for wiring but to make copper parts.

11. I may have disposed of all my steel wire of the type used not for ignition but to reinforce pipes or other casings.

12. I had probably disposed of all my brown wrapping paper.

13. I had probably disposed of, or at least melted the zinc off of, and placed with stuff to be dumped, all of the roofing nails of the type used to make pins to secure the plugs in detonating caps.

14. I had disposed of the ceramic cup, pieces of which I had pulverized to make filler material for mixing with epoxy.

15. I had disposed of all the limestone that I used to pulverize to make filler material for epoxy.

16. My tools had all been “cleaned up” by having their working surfaces filled so that they could not be identified by the marks they left on devices.

17. I had stuff loaded on a pack frame to be carried away for disposal.

18. I had a lot of material segregated from my other belongings and marked for disposal.

19. The list of potential targets was in the cut-down plastic jug with other papers that were being disposed of by being used as toilet paper and then burned.

20. I had disposed of all batteries that I had, except maybe one 9-volt battery and the batteries in my radios.

21. I may have disposed of my supply of taps (tools for threading screw-holes). If not, then I had them with other stuff that was slated for disposal.

22. The device in cabin was not “set” — I.e. it still had the safety pin in place, so it would not blow up FBI agents in cas of an arrest. I sort of felt sorry for the FBI agents — before I was arrested. After I was arrested ...

23. The following home-made devices had been partly or wholly dismantled or destroyed:

(a) My home-made chemical balance. This was partly dismantled and the sheet-metal and mahogany parts had been disposed of. The remaining parts were in the cabin.

(b) Two devices for wrapping wire tightly around a cylindrical object were completely destroyed. These were sketched in my notebooks.

c) A mold for casting lead sheets was completely destroyed. I think this was sketched, and I know it was described verbally in my notebooks.

(d) A device for holding a small-diameter copper tube while it was being loaded with explosive, so as to provide protection in case of an accidental explosion. This was sketched in my notebooks.

(e) Two jigs for holding cylinders while they were being packed with explosives. These may have been sketched in my notebooks.

Regarding the items sketched or described in the notebooks: I don’t know whether or not the relevant parts of the notebooks were destroyed.

Letter #4

To Judy, Scharlette, and Gary

What you three told me at our meeting of April 17 about the possibilities of freedom makes no sense to me.

Assuming that we lose on the search warrant, and barring some unforeseen and highly improbable development, I can’t see how my chances of freedom could be anything but minimal – say one chance in a hundred, or less.

1. As for winning the sympathy of a jury, bear in mind some of the things that my early (1970’s) writings indicate: indiscriminate, homicidal hostility towardd society in general, not just toward the corporate-governmental-technological elite; I hunted game illegaly and in a few cases even wasted meat; in a few cases I tortured small animals that had made me angry.

2. As for making a jury think they might have done what I did if they’d been in my shoes, consider the Menendez case. The Menedez brothers killed the parents who abused them – probably more severely than my parents abused me – and anyone can identify with that. Yet the Menendez brothers can expect to be in prison for a very long time, if not for life.

3. As for an insanity or mental-state defense, that too is implausible. Possibly some neurolgical damage might be demonstrated, but it is crystal-clear that I was fully in control of my own actions, I was well aware of what I was doing, I acted with a cool head, and I had no difficult in understanding the difference between what our society considers right and what our society considers wrong. Furthermore, little remorse can be shown in my case.

Contrast the case of Susan Smith: She was an obviously troubled young woman who acted under emotional stress and probably without long premeditation. Furthermore, if I remember correctly, she was very remorseful. Yet she's in prison for life.

4. You say that a substantial proportion of the American public is sympathetic toward my message. But most are not sympathetic toward my methods, and they will be even less sympathetic toward them when they learn about the things mentioned at 1 above.

5. The fact that O.J. Simpson got off has repeatedly been mentioned in order to encourage me. But the O.J. Simpson case is not comparable to mine because: (a) In Simpson's case there was the race angle -- he had a mostly black jury. (b) Problems with the evidence in Simpson's case left room for reasonable doubt. I didn't follow the case closely, but from what I did learn about it, it seemed that Simpson was probably guilty, but that his guilt was not proved beyond a reasonable doubt, because the abundant evidence of incompetence and virulent racism among the cops made it conceivable that the appearance of guilt might have been the result of some combination of evidence-tampering and laboratory incompetence. But in my case the evidence leaves no room for reasonable doubt. (c) Simpson had only one trial to go through.

6. As for the argument that expense or "embarrassment" might prevent the govt. from trying me more than once -- it seems absurd.As I pointed out at our meeting, since the govt. probaby spent at least 70 million dollars trying to catch the Uabomber, thecertainly won't hesitate to spend another 5 million or whatever it costs for a new tria

It would be difficult enough for you just to get me off at the first trial; that you could defeat the prosecution so soundly at the first trial that they would be too embarrassed to try me again -- is simply implausible. And what could be more embarrassing to the govt. than letting me go free? Surely they will make maximum effort to convict.

So I cannot understand how you can say -- as you did at our meeting -- that when the trial is about to begin you may perhaps be able to offer me a 20%, 30%, or even 60% chance of freedom. You say you need to know more about the case before you could make a judgement about that. But what more do you need to know? You are already familiar in a general way with the evidence and with what my life has been like. Surely at this stage it is improbable that you are going to come across something unexpected and of major importance either in the evidence or in my life history.

Consequently, the fact that you decline to describe my chances of freedom as minimal (if we lose on the search warrant) id something that I can only ascribe to one of two causes. Either an excess of professional caution makes you reluctant to commit yourself, or you are trying to encourage me and make me more hopeful.

If it's the latter, you're not doing me a favor. I'm better off with a realistic estimate of my chances.

Unless you can give me arguments that I find more plausible than those you've already given me, I will assume that my chances of freedom are minimal if we lose on the search warrant.

I invite your comments.

P.S. I forgot to mention -- Regarding the likelihood of my being tried in a state court if I get off in the federal courts, I assume that Quin and Judy would not be able to defend me in state courts, since they are federal defenders. This would encourage state prosecutors to try me, since they would expect me to be defended by less able counsel.

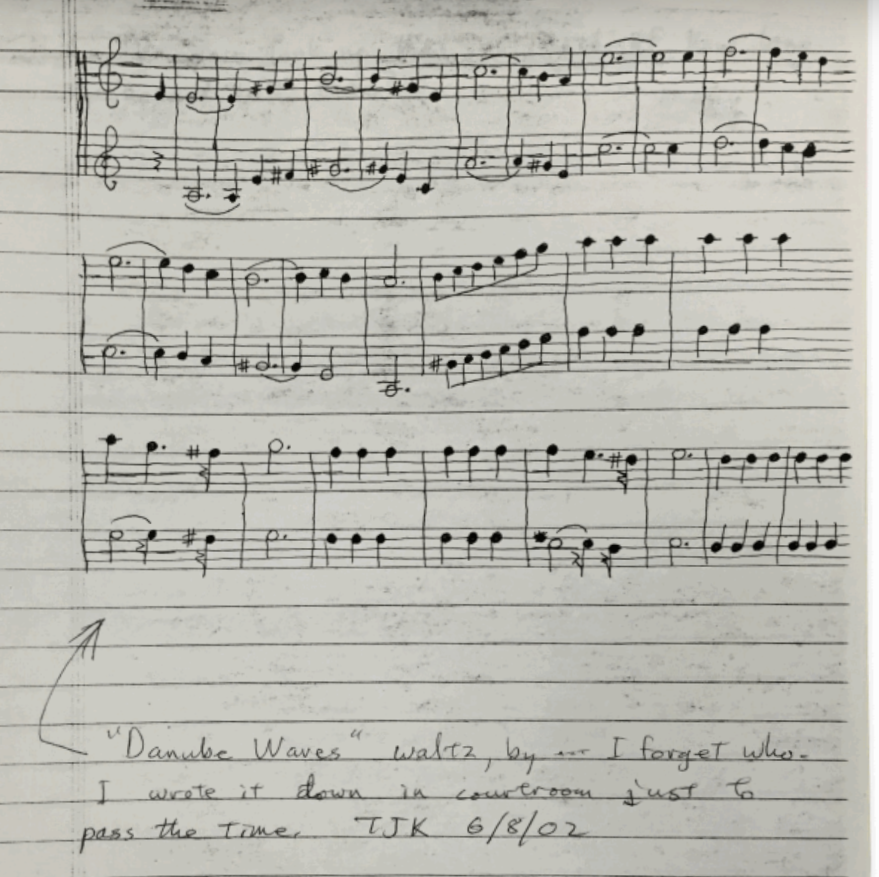

Musical notation

[Note written much later:] "Danube Waves" waltz, by ... I forget who. I wrote it down in courtroom just to pass the time. TJK 6/8/02

Letter to π

Dear π,

I enjoyed your letter of November 19 ...

Letter #6

Written in December or Late Nov. of 1997

Quin, Gary, Scharlette, and (most of all) Judy -

Of all the things you could have done to me, what you have done to me is the cruellest. I would rather have been killed, crucified, blinded – anything but this. The only thing you could do now to alleviate the unspeakable torment you are causing me would be to withdraw from the case. But I will bet that not one of you will in fact withdraw, and, whatever rationalizations you may invent, the reason you won’t withdraw is that remaining in the case satisfies your own needs, whether your career ambitions, or your emotional needs, or whatever. In order to satisfy your own needs you will continue to cause me this torment rather than withdraw.

What tortures me is not merely what you are doing with the case. If some attorney who was a stranger to me did the same things, it wouldn’t cause me nearly so much pain. What tortures me is the fact that you made yourselves my friends and now you do this to me.

It is a matter of principle with me to have nothing to do with the mental health professions. This is a principle to which I have not always adhered strictly. People often fail to adhere strictly to their own principles, but that doesn’t mean that the principles aren’t genuine.

At any rate, during the months of preperation for this trial, my attorneys Michael Donahoe, and later Gary Sowards, put me under heavy pressure to undergo examination by certain mental-health professionals. I was extremely reluctant to undergo such examination, but I eventually agreed to do so for two reasons: First, both Mr. Donahoe and Mr. Sowards professed warm friendship for me; they won my affection and I wanted to please them. Second, both Mr. Donahoe and Mr. Sowards assured me repeatedly that the examinations were covered by attorney-client privilege, and that the results of the examinations and even the fact that the examinations took place, would not be divulged to anyone outside the defence team without my permission. Both Judy Clarke and Quin Denvir were aware that these promises had been made to me. And all of my attorneys knew that the issue was extremely important to me.

On Teusday, November 25, in this courtroom, I learned for the first time that my attorneys had divulged to the prosecutors the fact that I’d undergone various mental-health examinations, and moreover had divulged my scores on certain neuropsychological tests. In view of the promises that had been made to me I was horrified and shocked. During the noon break I angrily confronted my attorneys, and they seemed contrite, but they had essentially no excuse to give for what they had done, except that they claimed they thought it was in my best interest as interpreted by them.

During the preparation for this trial, I was very worried about the possibility that my attorneys might misrepresent me and my life in various ways in order to win their case. I repeatedly raised the issue with Mr. Sowards and Ms. Clarke, telling them that I was afraid that their instincts as lawyers would lead them to pursue their single professional concern of winning the case without regard to important concerns of mine, such as my desire to be portrayed truthfully before the world. Mr. Sowards and Ms. Clarke repeatedly assured me that they would help me to pursue my concerns, even when these might conflict with their professional concerns as lawyers.

On Wednesday, November 26, I met with Quin Denvir, Judy Clarke, and Gary Sowards to discuss their breach of promise that I had found out about on the preceding day. I reminded them of the promise they had made me. They admitted that the promises had been made, and they expressed regret at having made them, but that what they said was essentially, “Tough luck. Promises or no promises, we are going to pursue our professional goal of winning the case, even if the methods we use are destructive toward your concerns, and there’s nothing you can do about it.” They put it a little more diplomatically than that, but that is what it amounted to.

This would have been sufficiently painful and humiliating to me in any case, but what made it infinitely worse was the fact that in the year and a half during which I’ve worked with the members of my defense team they have professed warm friendship for me, they have actively cultivated my friendship, so that I developed a strong affection for most of them. Some of them I even loved..

And to have them do this to me – to exploit a lonely man’s hunger for friendship in order to manipulate him and deceive him and then to tell him “Tough luck. We’re breaking our promises and you’re stuck with it.” - I’ve had some very painful and humiliating experiences in my life, but this is by far the worst. It Is many times worse than my brother’s denouncing me to the FBI and telling lies about me. If at the time I was arrested, I had been offered a choice between being crucified and having lawyers who would do this to me, I would unhesitatingly have chosen crucifixion as the lesser evil. I know that sounds like an exaggeration, but it’s the sober truth. I think my defense team will at least be honest enough to confirm I am not prone to exaggeration.

My feelings are such that there is no possible way I can continue to cooperate with these lawyers. Even just to see them makes me sick at heart. So I would ask your honor to do one of three things:

(a) Allow me to represent myself.

Failing that,

(b) Appoint new counsel for me.

Failing that,

(c) In view of the profound conflict of interest between me and my attorneys, appoint an attorney to represent me against my own attorneys.

Letter #7

This evening Judy Clarke gave me an outline of the opening statement she intends to give tomorrow. I was horrified. It's evident that she intends to give a picture of me that essentially supports the lies of my brother and mother. For example, she in effect denies the reality of the verbal abuse I suffered, saying that I was "oversensitive" and hurt by things my mother said would have "bounced off" most people. This in spite of the fact that in my refutation I showed that the abuse was real; that Meister's declaration states that my mother verbally abused me; that Dr. Kriegler concluded the abuse was real; and that according to Dr. Kriegler my brother said that when our mother got angry it was "close to feeling like what violence would feel like."

I would think that Judy Clarke just hasn't done her homework, but since she is a highly-regarded lawyer, that doesn't seem likely. The most probable explanation I think is this. Judy Clarke is a highly conventional person in the sense that she believes implicitly in all of the fundamental myths of our society. Since I was accused of being the Unabomber, she assumed from the outset that I was mentally ill, and thereafter she intepreted all information to fit that conclusion. Thus, she saw my perception of abuse as due to abnormal sensitivity on my part and tended to overlook the statements of psychologists (Meister, Kriegler) and others that the abuse was real.

What is disturbing is that, even though she knew all along that the abuse issue was extremely important to me, she never revealed to me until now, at the last minute, that she believed the abuse was at least partly imaginary and that she intended to present it that way at the trial.

It's true that when I objected to her statement about the abuse, she said she would consider changing it, but even if she does so, the warped picture of me she presents at least in the first draft of her opening statement bodes ill for the future. I can foresee a constant and largely unsuccessful struggle with her to try to get her to present an accurate picture of me.

My situation is simply grotesque. It is acutely demeaning and it progressively breaks down my strength, my energy, my will to resist, and my self-respect. It is impossible to distinguish between friends and enemies. My lawyers supposedly are charged with defending my interests, but they do so not as human beings making their own free choices; they do so as part of a more-or-less mechanistic system that processes me according to more-or-less rigid rules. They consider it their duty to portray me as mentally ill, against my strenuous opposition, because by doing so they may be able to "save" me from the death penalty (which I would prefer to a life in prison anyway). I bitterly resent their portrayal of me, yet on a personal level they are mostly very likeable people who treat me very kindly and never get angry at me even when I take actions intended to frustrate their "benign" efforts in my behalf. The prosecution, on the other hand, wants to cause my death, but in order to do sot hey can be expected to do me the favor of trying to refute my own lawyers' attempts to prove me crazy. The judge, who superintends the whole humiliating process, is a kindly and very conscientious man. The Federal Marshals treat me very kindly and take the greatest care to protect my physical safety; the jail is a wretched place, but that results from laziness and incompetence among the jail staff, and from the mere fact of confinement; it is not the result of any malice. So where is my enemy? There isn't any. I am simply caught in a machine that is subjecting me to intolerably humiliating conditions. The people who keep me locked up, my lawyers, the prosecutors, the judge are all just gears in that machine; they inflict misery and degradation on me merely by conscientiously performing their respective duties.

Since I can do very little for myself while locked up, I am completely helpless and dependant on others, especially my lawyers. Over time, it erodes one's elf-confidence. It forces one into a position of demeaning obedience: If I were to attempt to resist the jail people it would only result in my being made still more helpless - more closely watched.

[Missing page.]

no more compunction than I would have in squashing a cockroach.* Yet Judy Clarke thinks the Murrays were just wonderful people. She seems to hold this opinion uncritically and without reservation. In spite of this, I find her personality so attractive that I think I enjoy talking with her more than with any other person I've ever known, and I have a strong sense of rapport with her. So is she a friend or an enemy? In practical terms se is an enemy of me and of everything I stand for, but in terms of personal relations she is very friendly toward me and I have warm feelings of friendship toward her.

* In contrast, I take very seriously the suffering that David Gelernter underwent. Gelernter is no cliche, but a highly intelligent, thoughtful, talented, and sensitive man whom no one could describe as a mere stereotype. I consider that he deserved what he got, but that is a judgement that I do not adopt lightly and it is one about which I have mixed feelings.

Letter #8

Quin and Judy--

The Federal Defenders have screwed me roughly.

You talked me out of meeting with Serra while there was still time. Whatever his failings may be, Serra at least could have combated the image of me as a madman and would have helped me to make my public statement; and I would have been able to preserve the suppression appeal.

By keeping me in the dark until the trial was in progress, you lost me my chance to preserve the suppression appeal by defending myself.

Through your public statements and the declarations of your experts, you've reinforced the public's perception of me as a madman.

You prevented me from answering my brother's and mother's allegations earlier; and now the image of me as a madman is so strongly established that there is scarcely any chance of changing it.

I doubt that you fully appreciate the suffering I am undergoing as a result of the way you've dealt with me. Yet I realize that you acted as you did because you felt compelled to do so by the professional principles you adhere to (though your interpretation of those principles seems to me to be oddly mechanical and rigid). I could have forgiven you completely ...

Once you guys are no longer my legal representatives, if you ever want to visit me or write to me I will be very pleased to communicate with you, since we get along much better on a personal level than we do in our legal relationship.

I don't know whether you fully realize how much grief it causes me to think of breaking off with you. I was not exaggerating when I said the defense team had become like a family to me. On my side, at least, the emotional ties are too strong to be broken by any conflicts we may get into, no matter how bitter. So I hope that our personal friendship can be maintained permanently. But, as I've explained, I feel I have to find other legal advisors.

Letter Fragment to John Zerzan (Pages 2 & 8)

Page 2

[REDACTED] gets migraines, and my father used to get them too, so I know they can be pretty bad.

As I write this you must be just finishing your talk in the Gerlinger Lounge. Well, how did it go? You get a $500 honorarium for your talk? Impressive! I hope that success won't spoil you. (That's a joke; I'm confident that you won't be spoiled.)

Unlike you, I am not relieved that the death penalty is out of the picture. In order to get that deal I had to sign away my right to an appeal that might possibly have led to my release. I signed only because I had no other way of preventing my attorneys from putting on a defense that would have portrayed me essentially as insane. My attorneys are very able lawyers and they have been very kind to me on a personal level, but my relationship with them has been a tragic and disastrous mis-match.

Have you heard anything lately from our acquaintance at Stanford, Professor A? I have not. He's probably lost interest in the case. I have an impression that he is an emotional person and perhaps not very steady or consistent. ...

Page 8

The fact that Quin Denvir is actually encouraging me to speak with an outside lawyer means that I no longer feel I have to seperate myself from the Fed Defenders (provided that our mutual friend does not consider my relationship with them to be an obstacle to his meeting with me), because for all practical purposes the Fed Defs will no longer be representing me except at the May 15 sentencing. And it will be convenient for me to keep them formally as my representatives until May 15 because that way they will be able to continue to perform many services for me, such as bringing me documents, etc. Really, they are so helpful and kind to me that I often feel guilty about having had such conflicts with them over the defense strategy.

Please let me know what our mutual friend thinks about this.

One more piece of news: It's been announced that I will not be prosecuted on a California state charge. I don't know whether that's good or bad.

I guess that's enough for one letter.

With many thanks for your support,

Ted

P.S. John, I suggest that you save this letter permanently.

Letter X

Dear Mr. Bowden:

I'm sorry I've taken three months to answer your letter...

The following is from a letter dated ... sent to me by Carol Sessions, formerly a secretary at the Federal Defender's Office in Sacramento:

Judy Clarke and I butted heads quite a few times while working on your case. I thought sure she was going to remove me from the case, but I was too valuable a worker and was made sure she had nothing on me. I made it. She's a machine -- treats her employees like a military sergeant. Makes them jog every morning, etc. Told her no way would I ever work for her.

As I've said, work on the new book leaves me no time for nonessential correspondence, so I've dropped the correspondence with Carol ...

Letter Y

Dear Gerry,

In your letter of June 19 you offer to send me a couple of your books, and you ask whether the prison authorities will let me have them. Assuming that your books do not encourage violence, give instrucitions for making weapons, or anything of that sort, the answer is “yes;” though hardcover books must have their covers removed before being sent into the prison.

However, inmates are allowed to keep only a limited number of books in their cells, and at present I am overstocked with books. Perhaps you would like to send your books to a friend of mine whose address is [REDACTED] and who will forward the books to me when I am ready for them. By the way, I have read your book From Freedom to Slavery, which you sent to me through Mr. Donahoe shortly after my arrest.

You write, “I run a pro bono trial lawyer’s college at my ranch to teach young lawyers how to beat the corporate slave master and its minion, the government.” I assume this is your answer to my question, “What are you doing to make a difference?” The most critical problems in the world today are inevitable outgrowths of modern technology, and they can be solved only through the breakdown of the entire technological system. If, as I suspect, what you teach young lawyers does nothing to increase the likelihood of such a breakdown, then you are not helping to make the kind of difference that would really count.

As for myself, I write articles for small radical journals and correspond with various people, the object being to form a revolutionary movement specifically directed toward the overthrow of the technoindustrial system. There already is a revolutionary movement of sorts; they call themselves “Green Anarchists”, “Anarchoprimitivists,” “ELF,” “ALF,” etc. But I believe that this movement is of low effectiveness and that something better is needed.

Sincerely yours,

Ted Kaczynski