Ted Kaczynski

Morality and Revolution (1st Edition)

“Morality, guilt and fear of condemnation act as cops in our heads, destroying our spontaneity, our wildness, our ability to live our lives to the full...

I try to act on my whims, my spontaneous urges without caring what others think of me....

I want no constraints on my life; I want the opening of all possibilities....

This means... destroying all morality.”

— Feral Faun, “The Cops in Our Heads: Some Thoughts on Anarchy and Morality.” in The Quest Tor the Spiritual

It is true that the concept of morality as conventionally understood is one of the most important tools that the system uses to control us, and we must liberate ourselves from it.

But suppose you’re in a bad mood one day. You see an inoffensive but ugly old lady; her appearance irritates you, and your “spontaneous urges” impel you to knock her down and kick her. Or suppose you have a “thing” for little girls, so your “spontaneous urges” lead you to pick out a cute four-year-old, rip off her clothes, and rape her as she screams in terror.

I would be willing to bet that there is not one anarchist reading this who would not be disgusted by such actions, or who would not try to prevent them if he saw them being carried out. Is this only a consequence of the moral conditioning that our society imposes on us?

I argue that it is not. I propose that there is a kind of natural “morality” (note the quotation marks), or a conception of fairness, that runs as a common thread through all cultures and tends to appear in them in some form or other, though it may often be submerged or modified by forces specific to a particular culture. Perhaps this conception of fairness is biologically predisposed. At any rate it can be summarized in the following Six Principles:

-

Do not harm anyone who has not previously harmed you, or threatened to do so.

-

PRINCIPLE OF SELF-DEFENCE AND RETALIATION: You can harm others in order to forestall harm with which they threaten you, or in retaliation for harm that they have already inflicted on you.

-

ONE GOOD TURN DESERVES ANOTHER: If someone has done you a favor, you should be willing to do her or him a comparable favor if and when he or she should need one.

-

The strong should have consideration for the weak.

-

Do not lie.

-

Abide faithfully by any promises or agreements that you make.

To take a couple of examples of the ways in which the Six Principles often are submerged by cultural forces, among the Navajo, traditionally, it was considered “morally acceptable” to use deception when trading with anyone who was not a member of the tribe (WA. Haviland, Cultural Anthropology, 9th ed., p. 207), though this contravenes principles 1, 5, and 6. And in our society many people will reject the principle of retaliatory action, we are trained to suppress our retaliatory impulses and leave any serious retaliation (called ‘justice’) to the legal system.

In spite of such examples, I maintain that the Six Principles tend toward universality. But whether or not one accepts that the Six Principles are to any extent universal, I feel safe in assuming that almost all readers of this article will agree with the principles (with the possible exception of the principle of retaliation) in some shape or other. Hence the Six Principles can serve as a basis for the present discussion.

*

I argue that the Six Principles should not be regarded as a moral code, for several reasons.

First: The principles are vague and can be interpreted in such widely ways that there will be no consistent agreement as to their application in concrete cases. For instance, if Smith insists on playing his radio so loud that it prevents Jones from sleeping, and if Jones smashes Smith’s radio for him, is Jones’s action unprovoked harm inflicted on Smith, or is it legitimate self-defense against harm that Smith is inflicting on Jones? On this question Smith and Jones are not likely to agree! (All the same, there are limits to the interpretation of the Six Principles. I imagine it would be difficult to find anyone in any culture who would interpret the principles in such a way as to justify brutal physical abuse of unoffending old ladies or the rape of four-year-old girls.)

Second: Most people will agree that it is sometimes “morally” justifiable to make exceptions to the Six Principles. If your friend has destroyed logging equipment belonging to a large timber corporation, and if the police come around to ask you who did it, any green anarchist will agree that it is justifiable to lie and say, “I don’t know”.

Third: The Six Principles have not generally been treated as if they possessed the force and rigidity of true moral laws. People often violate the Six Principles even when there is no “moral” justification for doing so. Moreover, as already noted, the moral codes of particular societies frequently conflict with and override the Six Principles. Rather than laws, the principles are only a kind of guide, an expression of our more generous impulses that reminds us not to do certain things that we may later look back on with disgust.

Fourth: I suggest that the term “morality” should be used only to designate socially imposed codes of behavior that are specific to certain societies, cultures, or subcultures. Since the Six Principles, in some form or other, tend to be universal and may well be biologically predisposed, they should not be described as morality.

Assuming that most anarchists will accept the Six Principles, what the anarchist (or, at least, the anarchist of individualistic type) does is claim the right to interpret the principles for himself in any concrete situation in which he is involved and decide for himself when to make exceptions to the principles, rather than letting any authority make such decisions for him.

However, when people interpret the Six principles for themselves, conflicts arise because different individuals interpret the principles differently. For this reason among others, practically all societies have evolved rules that restrict behavior in more precise ways than the Six Principles do. In other words, whenever a number of people are together for an extended period of time, it is almost inevitable that some degree of morality will develop. Only the hermit is completely free. This is not an attempt to debunk the idea of anarchy. Even if there is no such thing as a society perfectly free of morality, still there is a big difference between a society in which the burden of morality is light and one in which it is heavy. The pygmies of the African rain forest, as described by Colin Turnbull in his books The Forest People and Wayward Servants: The Two Worlds of the African Pygmies, provide an example of a society that is not far from the anarchist ideal. Their rules are few and flexible and allow a very generous measure of personal liberty. (Yet, even though they have no cops, courts or prisons, Turnbull mentions no case of homicide among them.)

In contrast, in technologically advanced societies the social mechanism is complex and rigid, and can function only when human behavior is closely regulated. Consequently such societies require a far more restrictive system of law and morality. (For present purposes we don’t need to distinguish between law and morality. We will simply consider law as a particular kind of morality, which is not unreasonable, since in our society it is widely regarded as immoral to break the law.) Old-fashioned people complain of moral looseness in modern society, and it is true that in some respects our society is relatively free of morality. But I would argue that our society’s relaxation of morality in sex, art, literature, dress, religion, etc., is in large part a reaction to the severe tightening of controls on human behavior in the practical domain. Art, literature and the like provide a harmless outlet for rebellious impulses that would be dangerous to the system if they took a more practical direction, and hedonistic satisfactions such as overindulgence in sex or food, or intensely stimulating forms of entertainment, help people to forget the loss of their freedom.

At any rate, it is clear that in any society some morality serves practical functions. One of these functions is that of forestalling conflicts or making it possible to resolve them without recourse to violence. (According to Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’s book The Harmless People, Vintage Books, Random House, New York, 1989, pages 10, 82, 83, the Bushmen of Southern Africa own as private property the right to gather food in specified areas of the veldt, and they respect these property rights strictly. It is easy to see how such rules can prevent conflicts over the use of food resources.)

Since anarchists place a high value on personal liberty, they presumably will want to keep morality to a minimum, even if this costs them something in personal safety or other practical advantages. It’s not my purpose here to try to determine where to strike the balance between freedom and the practical advantages of morality, but I do want to call attention to a point that is often overlooked: the practical or materialistic benefits of morality are counterbalanced by the psychological cost of repressing our “immoral” impulses. Common among moralists is a concept of “progress” according to which the human race is supposed to become ever more moral. More and more “immoral” impulses are to be suppressed and replaced by “civilized” behavior. To these people morality apparently is an end in itself. They never seem to ask why human beings should become more moral. What end is to be served by morality? If the end is anything resembling human well-being then an ever more sweeping and intensive morality can only be counterproductive, since it is certain that the psychological cost of suppressing “immoral” impulses will eventually outweigh any advantages conferred by morality (if it does not do so already). In fact, it is clear that, whatever excuses they may invent, the real motive of the moralists is to satisfy some psychological need of their own by imposing their morality on other people. Their drive toward morality is not an outcome of any rational program for improving the lot of the human race.

This aggressive morality has nothing to do with the Six Principles of fairness. It is actually inconsistent with them. By trying to impose their morality on other people, whether by force or through propaganda and training, the moralists are doing them unprovoked harm in contravention of the first of the Six Principles. One thinks of nineteenth-century missionaries who made primitive people feel guilty about their sexual practices, or modern leftists who try to suppress politically incorrect speech.

Morality often is antagonistic toward the Six Principles in other ways as well. To take just a few examples:

The morality of modern society tells us to prevent suicide, if necessary by interfering forcibly. This may not always be a violation of the Six Principles. In some cases a person may be driven towards suicide by some temporary grief that he will soon get over, and if you prevent him from killing himself, he will thank you for it afterward. But there are other cases in which a person has good reason to commit suicide to escape prolonged suffering, say, or because in some situations death may be the only alternative that is consistent with an individual's dignity. Under the circumstances, to prevent a person from committing suicide can be serious cruelty and a violation of the first principle of fairness. (compare the attitude towards suicide among certain Eskimos, as described by Giontran de Poncins in his book Kabloona)

In our society private property is not what it is among the Bushmen — a simple device for avoiding conflict over the use of resources. Instead, it is a system whereby certain persons or organizations arrogate control over vast quantities of resources that they use to exert power over other people. In this they certainly violate the first and fourth principles of fairness. By requiring us to respect property, the morality of our society helps to perpetuate a system that is clearly in conflict with the six Principles.

The military is expected to kill or refrain from killing in blind obedience to orders from the government; policemen and judges are expected to imprison or release persons in mechanical obedience to the law. It would be regarded as “unethical” and “irresponsible” for soldiers, judges, or policemen to act according to their own sense of fairness rather than in conformity with the rules of the system. A moral and “responsible” judge will send a man to prison if the law tells him to do so, even if the man is blameless according to the six Principles.

A claim of morality often serves as a cloak for what would otherwise be seen as the naked imposition of one’s own will on other people. Thus, if a person said,

I am going to prevent you from having an abortion (or from having sex or eating meat or something else) just because I personally find it offensive,

His attempt to impose his will would be considered arrogant and unreasonable. But if he claims to have a moral basis for what he is doing, if he says, “I’m going to prevent you from having an abortion because it’s immoral”, then his attempt to impose his will acquires a certain legitimacy, or at least tends to be treated with more respect than it would be if he made no moral claim.

People who are strongly attached to the morality of their own society often are oblivious to the principles of fairness. The highly moral and Christian businessman John D. Rockefeller used underhand methods to achieve success, as is admitted by Allan Nevin in his admiring biography of Rockefeller. Today, screwing people in one way or another is almost an inevitable part of any large-scale business enterprise. Willful distortion of the truth, serious enough so that it amounts to lying, is in practice treated as acceptable behavior among politicians and journalists, though most of them undoubtedly regard themselves as moral people.

I have before me a flyer sent out by a magazine called The National Interest. In it I find the following:

Your task at hand is to defend our nation’s interests abroad, and rally support at home for your efforts. You are not, of course, naive. You believe that, for better or worse, international politics remains essentially power politics-- that as Thomas Hobbes observed, when there is no agreement among states, clubs are always trumps.

This is a nearly naked advocacy of Machiavellianism in international affairs, though it is safe to assume that the people responsible for the flyer I’ve just quoted are firm adherents of conventional morality within the United States. For such people, I suggest, conventional morality serves as a substitute for the Six Principles. As long as these people comply with conventional morality, they have a sense of righteousness that enables them to disregard the principles of fairness without discomfort.

Another way in which morality is antagonistic toward the Six Principles is that it often serves as an excuse for mistreatment or exploitation of persons who have violated the moral code or the laws of a given society. In the United States, politicians promote their careers by “getting tough on crime” and advocating harsh penalties for people who have broken the law. Prosecutors often seek personal advancement by being as hard on defendants as the law allows them to be. This satisfies certain sadistic and authoritarian impulses of the public and allays the privileged classes’ fear of social disorder. It all has little to do with the Six Principles of fairness. Many of the “criminals” who are subjected to harsh penalties--for example, people convicted of possessing marijuana--have in no sense violated the Six Principles. But even where culprits have violated the Six Principles their harsh treatment is motivated not by a concern for fairness, or even for morality, but politicians’ and prosecutors’ personal ambitions or by the public’s sadistic and punitive appetites. Morality merely provides the excuse.

In sum, anyone who takes a detached look at modern society will see that, for all its emphasis on morality, it observes the principles of fairness very poorly indeed. Certainly less well than many primitive societies do.

Allowing for various exceptions, the main purpose that morality serves in modern society is to facilitate the functioning of the technoindustrial system. Here’s how it works:

Our conception both of fairness and of morality is heavily influenced by self-interest. For example, I feel strongly and sincerely that it is perfectly fair for me to smash up the equipment of someone who is cutting down the forest. Yet part of the reason why I feel this way is that the continued existence of the forest serves my personal needs. If I had no personal attachment to the forest I might feel differently. Similarly, most rich people probably feel sincerely that the laws that restrict the ways in which they use their property are unfair. There can be no doubt that, however sincere these feelings may be, they are motivated largely by self-interest.

People who occupy positions of power within the system have an interest in promoting the security and the expansion of the system. When these people perceive that certain moral ideas strengthen the system or make it more secure, then, either from concious self-interest or because their moral feelings are influenced by self-interest, they apply pressure to the media and to educators to promote these moral ideas. Thus the requirements of respect for property, and of orderly, docile, rule-following, cooperative behavior, have become moral values in our society (even though these requirements can conflict with the principles of fairness) because they are necessary to the functioning of the system. Similarly; harmony and equality between different races and ethnic groups is a moral value of our society because interracial and interethnic conflict impede the functioning of the system. Equal treatment of all races and ethnic groups may be required by the principles of fairness, but this is not why it is a moral value of our society. It is a moral value of our society because it is good for the technoindustrial system. Traditional moral restraints on sexual behavior have been relaxed because the people who have power see that these restraints are not necessary to the functioning of the system and that maintaining them produces tensions and conflicts that are harmful to the system.

Particulary instructive is the moral prohibition of violence in our society. (By “violence” I mean physical attacks on human beings or the application of physical force to human beings.) Several hundred years ago, violence per se was not considered immoral in European society. In fact, under suitable conditions, it was admired. The most prestigious social class was the nobility, which was then a warrior caste. Even on the eve of the Industrial violence was not regarded as the greatest of all evils, and certain other values--personal liberty for example--were felt to be more important than the avoidance of violence. In America, well into the nineteenth century, public attitudes toward the police were negative, and police forces were kept weak and inefficient because it was felt that they were a threat to freedom. People preferred to see to their own defense and accept a fairly high level of violence in society rather than risk any of their personal liberty.

Since then, attitudes toward violence have changed dramatically. Today the media, the schools, and all who are committed to the system brainwash us to believe that violence is the one thing above all others that we must never commit. (Of course, when the system finds it convenient to use violence--via the police or the military--for its own purposes, it can always find an excuse for doing so.)

It is sometimes claimed that the modern attitude toward violence is a result of the gentling influence of Christianity, but this makes no sense. The period during which Christianity was most powerful in Europe, the Middle Ages, was a particularly violent epoch. It has been during the course of the Industrial Revolution and the ensuing technological changes that attitudes toward violence have been altered, and over the same span of time the influence of Christianity has been markedly weakened. Clearly it has not been Christianity that has changed attitudes toward violence.

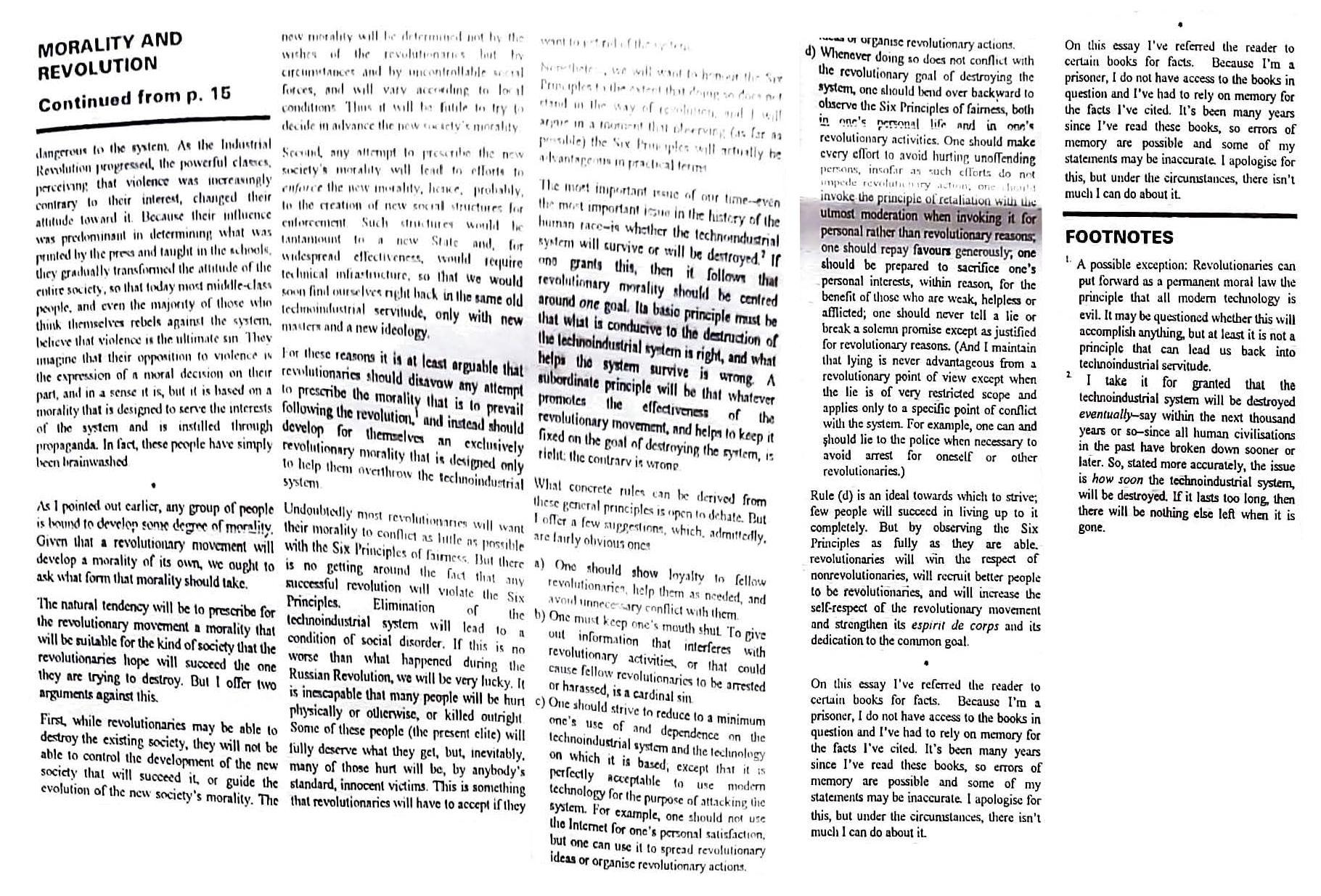

It is necessary for the functioning of modern industrial society that people should operate in a rigid, machine-like way, obeying rules, following orders and schedules, carrying out prescribed procedures. Consequently, the system requires, above all, human docility and social order. Of all human behaviors, violence is the one most disruptive of social order, hence the one most dangerous to the system. As the Industrial Revolution progressed, the powerful classes, perceiving that violence was increasingly contrary to their interest, changed their attitude toward it. Because their influence was predominant in determining what was printed by the press and taught in the schools, they gradually transformed the attitude of the entire society, so that today most middle class people, and even the majority of those who think themselves rebels against the system, believe that violence is the ultimate sin. They imagine that their opposition to violence is the expression of a moral decision on their part, and in a sense it is, but it is based on a morality that is designed to serve the interests of the system and is instilled through propaganda. IN fact, these people have simply been brainwashed.

*

As I pointed out earlier, any group of people is bound to develop some degree of morality. Given that a revolutionary movement will develop a morality of its own, we ought to ask what form that morality should take.

The natural tendency will be to prescribe for the revolutionary movement a morality that will be suitable for the kind of society that the revolutionaries hope will succeed the one they are trying to destroy. But I offer two arguments against this.

First, while revolutionaries may be able to destroy the existing society, they will not be able to control the development of the new society that will succeed it, or guide the evolution of the new society's morality. The new morality will be determined not by the wishes of the revolutionaries, but by the circumstances and by uncontrollable social forces, and will vary according to local conditions Thus it will be futile to try to decide in advance the new society's morality.

Second, any attempt to prescribe the new society's morality will lead to efforts to enforce the new morality, hence, probably to the creation of new social structures for enforcement. Such structures would be tantamount to a new state and, for widespread effectiveness, would require technical infrastructure, so that we would soon find ourselves right back in the same old techno industrial servitude, only with new masters and a new ideology.

For these reasons, it is al least arguable that revolutionaries should disavow any attempt to prescribe the morality that is to prevail following the revolution,[1] and instead should develop for themselves and exclusively revolutionary morality that is designed only to help them overthrow the techno industrial system.

Undoubtedly most revolutionaries will want their morality to conflict as little as possible with the Six Principles of fairness. But there is no getting around the fact that any successful revolution will violate the Six Principles Elimination of the techno industrial system will lead to a condition of social disorder If this is no worse than what happened during the Russian Revolution, we will be very lucky. It is inescapable that many people will be hurt physically or otherwise, or killed outright. Some of these people (the present elite) will fully deserve what they get, but, inevitably, many of those hurt will be. by anybody s standard, innocent victims. This is something that revolutionaries will have to accept if they want to get rid of the system.

Nonetheless, we will want to honor the Six Principles to the extent that doing so does not stand in the way of revolution, and I will argue in a moment that observing (as far as possible) the Six Principles will actually be advantageous in practical terms.

The most important issue of our time—even the most important issue in the history of the human race—is whether the techno industrial system will survive or will be destroyed.[2] If one grants this, then it follows that revolutionary morality should be centered around one goal. Its basic principle must be that what is conducive to the destruction of the techno industrial system is right, and what helps the system to survive is wrong. A subordinate principle will be that whatever promotes the effectiveness of the revolutionary movement, and helps to keep it Fixed on the goal of destroying the system, is right; the contrary is wrong.

What concrete rules can be derived from these general principles is open to debate. But I offer a few suggestions, which, admittedly, are fairly obvious ones.

a) One should show loyalty to fellow revolutionaries, help them as needed, and avoid unnecessary conflict with them.

b) One must keep one’s mouth shut. To give out information that interferes with revolutionary activities, or that could cause fellow revolutionaries lo be arrested or harassed, is a cardinal sin.

c) One should strive to reduce to a minimum one's use of and dependence on the techno industrial system and the technology on which it is based; except that it is perfectly acceptable to use modern technology for the purpose of attacking the system. For example, one should not use the Internet for one's personal satisfaction, but one can use it to spread revolutionary ideas or organize revolutionary actions.

d) Whenever doing so does not conflict with the revolutionary goal ol destroying the system, one should bend over backward to observe the Six Principles of fairness, both in one’s personal life and in one’s revolutionary activities. One should make every effort to avoid hurting unoffending persons, insofar as such efforts do not impede revolutionary action, one should invoke the principle of retaliation with the utmost moderation when invoking it for personal rather than revolutionary reasons; one should repay favors generously, one should be prepared to sacrifice one's personal interests, within reason, for the benefit of those who are weak, helpless or afflicted; one should never tell a lie or break a solemn promise except as justifies for revolutionary reasons. (And I maintain that lying is never advantageous from a revolutionary point of view except when the lie is of very restricted scope and applies to only a specific point of conflict with the system. For example, one can and should lie to the police when necessary to avoid arrest for oneself or other revolutionaries.)

Rule (d) is an ideal way towards which to strive; few people will succeed in living up to it completely. But by observing the Six Principles as fully as they are able, revolutionaries will win the respect of nonrevolutionaries, will recruit better people to be revolutionaries, and will increase the self-respect of the revolutionary movement and strengthen its espirit de corps and its dedication to the common goal.

*

On this essay, I’ve referred the reader to certain books for facts. Because I m a prisoner, 1 do not have access to the books in question and I’ve had to rely on memory for the facts I’ve cited. It’s been years since I’ve read these books. so errors of memory are possible and some of my statements may be inaccurate. I apologize for this, but under the circumstances, there isn’t much I can do about it.

[1] A possible exception Revolutionaries can put forward as a permanent moral law the principle that all modern technology is evil. It may be questioned whether this will accomplish anything, but at least it is not a principle that can lead us back into techno industrial servitude.

[2] I take it for granted that the techno industrial system will be destroyed eventually—say within the next thousand years or so—since all human civilizations in the past have broken down sooner or later. So, stated more accurately the issue is how soon the techno industrial system, will be destroyed. If it lasts too long, then there will be nothing else left when it is gone.