Ted Kaczynski’s Letter Correspondence with August Hampton

Ted to August — Apr. 30th, 2001

Ted to August — Aug. 29th, 2001

Ted to August — Nov. 16th, 2001

List of known letters

-

August to Ted (unknown date)

-

Ted to August (unknown date)

-

August to Ted — Apr. 6th, 2001

-

Ted to August — Apr. 30th, 2001

-

August to Ted — Aug. 2nd, 2001

-

Ted to August — Aug. 29th, 2001

-

August to Ted — Sep. 17th, 2001

-

Ted to August — Nov. 16th, 2001

-

Ted to August — Feb. 26th, 2002

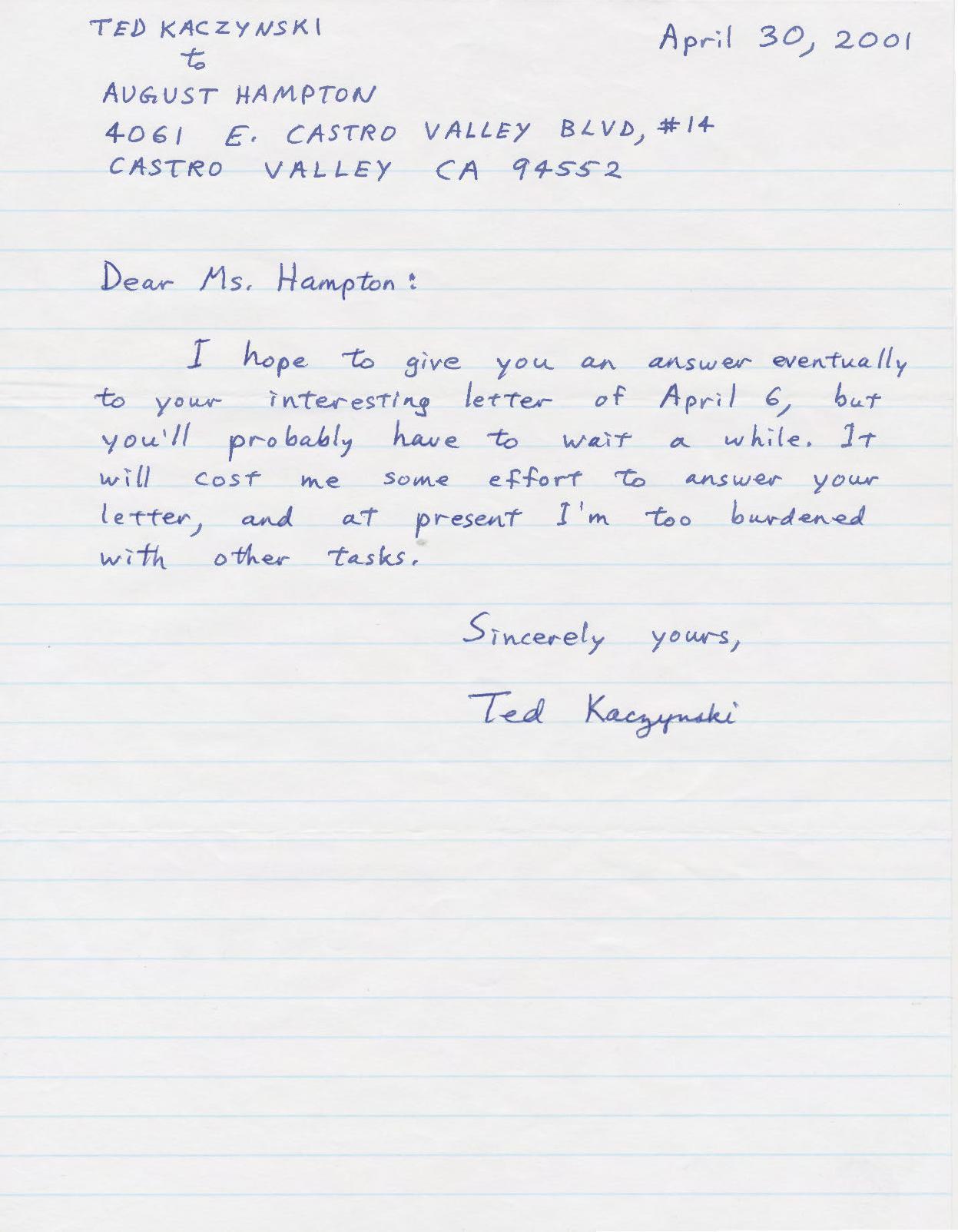

Ted to August — Apr. 30th, 2001

Dear Ms. Hampton,

I hope to give you an answer eventually ...

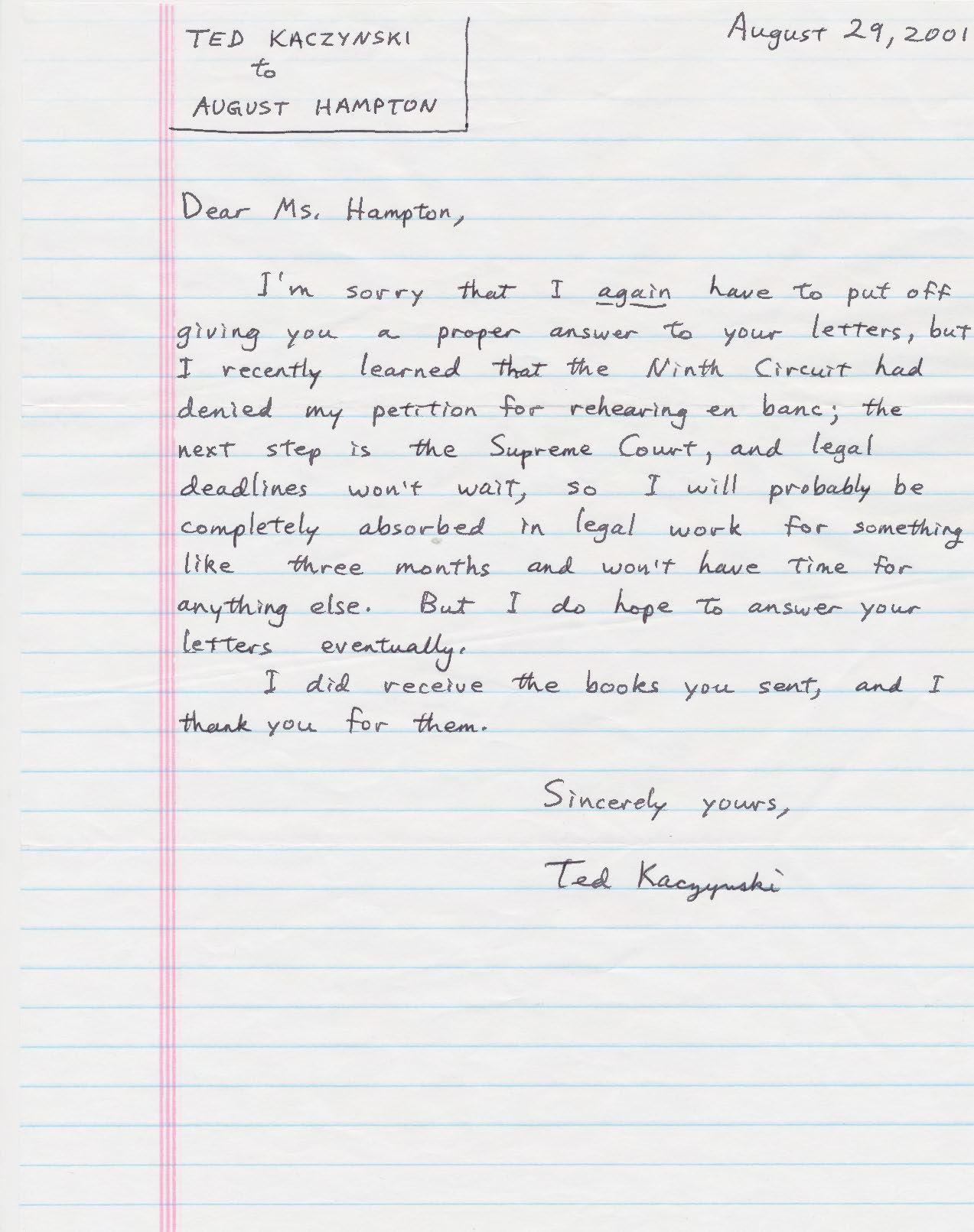

Ted to August — Aug. 29th, 2001

Dear Ms. Hampton,

I’m sorry that I again have to put off giving you a proper answer to your letters, but I recently learned that the Ninth Circuit had denied my petition for rehearing en banc; the next step is the Supreme Court, and legal deadlines won’t wait, so I will probably be completely absorbed in legal work for something like three months and won’t have time for anything else. But I do hope to answer your letters eventually.

I did receive the books you sent, and I thank you for them.

Sincerely yours,

Ted Kaczynski

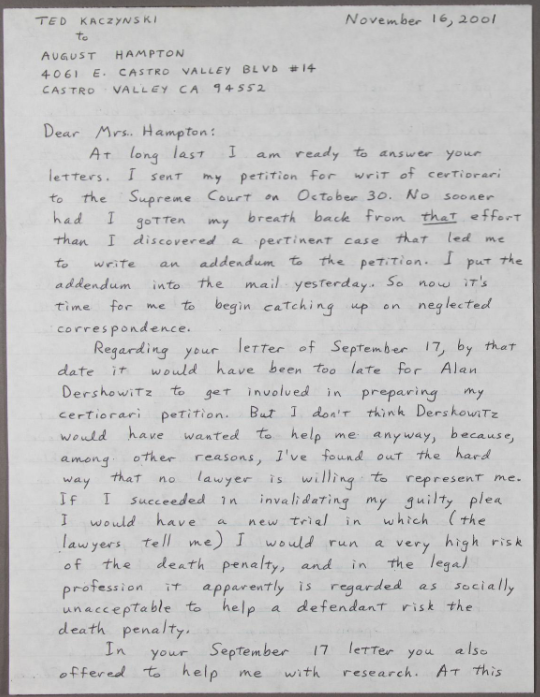

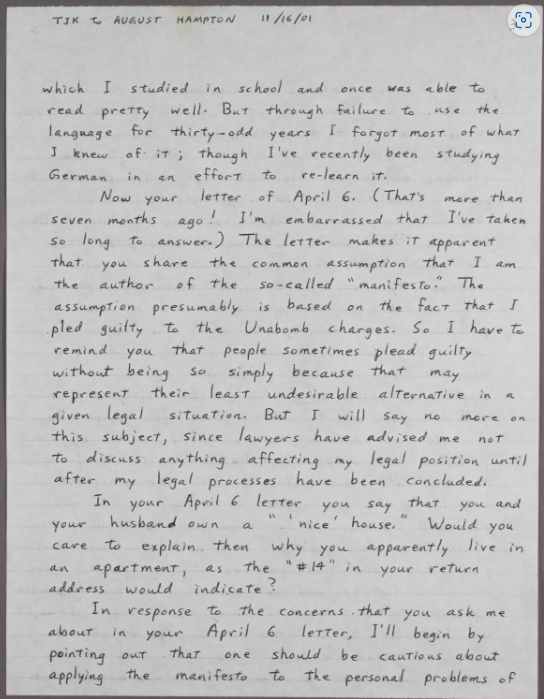

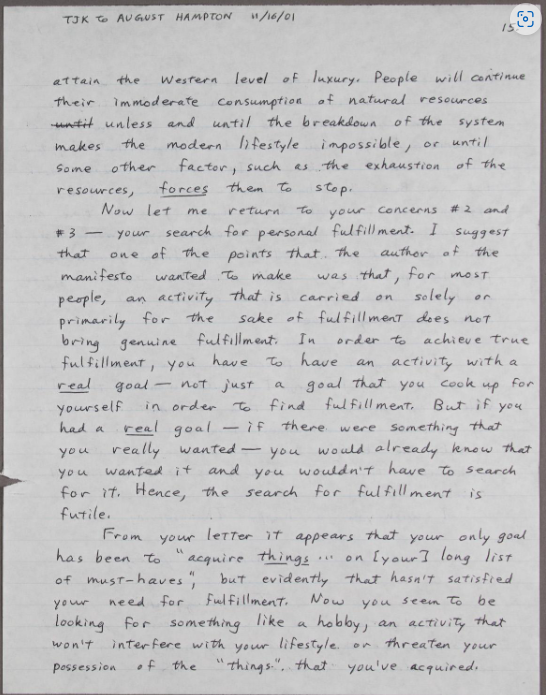

Ted to August — Nov. 16th, 2001

TED KACZYNSKI

to

AUGUST HAMPTON

4061 E. CASTRO VALLEY BLVD #14

CASTRO VALLEY CA 94552

Dear Mrs. Hampton:

At long last I am ready to answer your letters. I sent my petition for writ of certiorari to the Supreme Court on October 30 ...

... it would have been too late for Alan Dershowitz to get involved in preparing my certiorari petition. I don’t think Dershowitz would have wanted to help me anyway ...

... I’ve found out the hard way that no lawyer is willing to represent me ...

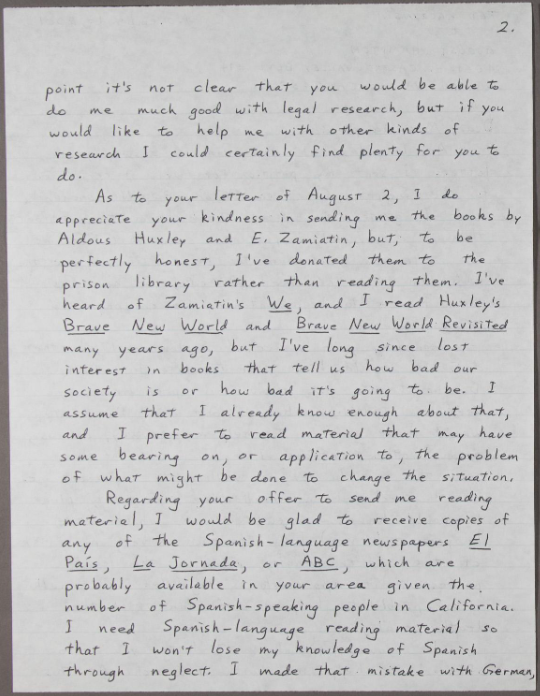

As to your letter of August 2, I do appreciate your kindness in sending me the books by Aldous Huxley and E. Zamiatin, but, to be perfectly honest, I’ve donated them to the prison library rather than reading them. I’ve heard of Zamiatin’s We, and I read Huxley’s Brave New World and Brave New World Revisited many years ago, but I’ve long since lost interest in books that tell us how bad our society is or how bad it’s going to be. I assume that I already know enough about that, and I prefer to read material that may have some bearing on, or application to, the problem of what might be done to change the situation.

Regarding your offer to send me reading material, I would be glad to receive copies of any of the Spanish-language newspapers El Pais, La Jornada, or ABC, which are probably available in your area given the number of Spanish-speaking people in California. I need Spanish-language reading material so that I won’t lose my knowledge of Spanish through neglect. I made that mistake with German, which I studied in school and once was able to read pretty well. But through failure to use the language for thirty-odd years I forgot most of what I knew of it; though I’ve recently been studying German in an effort to re-learn it.

Now your letter of April 6. (That’s more than seven months ago! I’m embarrassed that I’ve taken so long to answer.) The letter makes it apparent that you share the common assumption that I am the author of the so-called “manifesto”. The assumption presumably is based on the fact that I pled guilty to the Unabomb charges. I have to remind you that people sometimes plead guilty without being so, simply because that may be their least undesirable alternative in a given legal situation. But I will say no more on this subject, since lawyers have advised me not to discuss anything affecting my legal position until after my legal processes have been concluded.

In your April 6 letter you say that you and your husband own a “‘nice’ house.” Would you care to explain then why you apparently live in an apartment, as the “#14” in your return address would indicate?

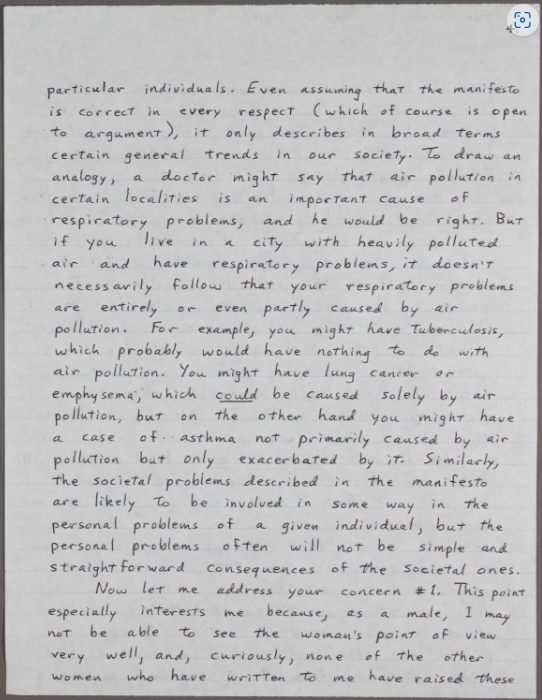

In response to the concerns that you ask me about in your April 6 letter, I’ll begin by pointing out that one should be cautious about applying the manifesto to the personal problems of particular individuals. Even assuming the manifesto is correct in every respect (which of course is open to argument), it only describes in broad terms the certain general trends in our society. To draw an analogy, a doctor might say that air pollution in certain localities is an important cause of respiratory problems, and he would be right. But if you live in a city with heavily polluted air and have respiratory problems, it doesn’t necessarily follow that your respiratory problems are entirely or even partly caused by air pollution. For example, you might have tuberculosis, which probably would have nothing to do with emphysema, which could be caused solely by air pollution, but on the other hand you might have a case of asthma not primarily caused by air pollution but only exacerbated by it. Similarly, the societal problems described in the manifesto are likely to be involved in some way in the personal problems of a given individual, but the personal problems often will not be simple and straightforward consequences of the societal ones.

Now let me address your concern #1. This point especially interests me because, as a male, I may not be able to see the woman’s point of view very well, and, curiously, none of the other women who have written to me have raised these issues to any great extent.

To me it looks as if your conception of the disadvantages faced by women in non-modern societies is vastly exaggerated. I wonder whether you’ve gotten a lot of your information from feminist propaganda. If you read the writings of certain anarchoprimitivists you’ll get propaganda of the opposite kind: they will tell you that before the advent of civilisation everyone had “gender equality.” Information from people who have an ideological axe to grind commonly is highly unreliable.

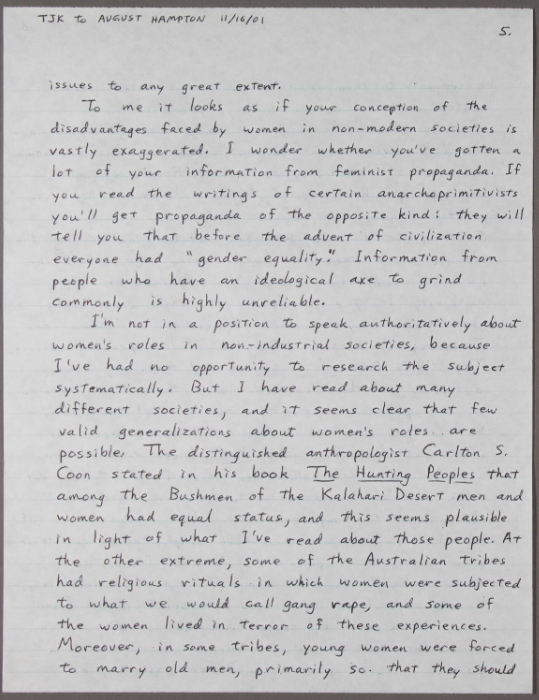

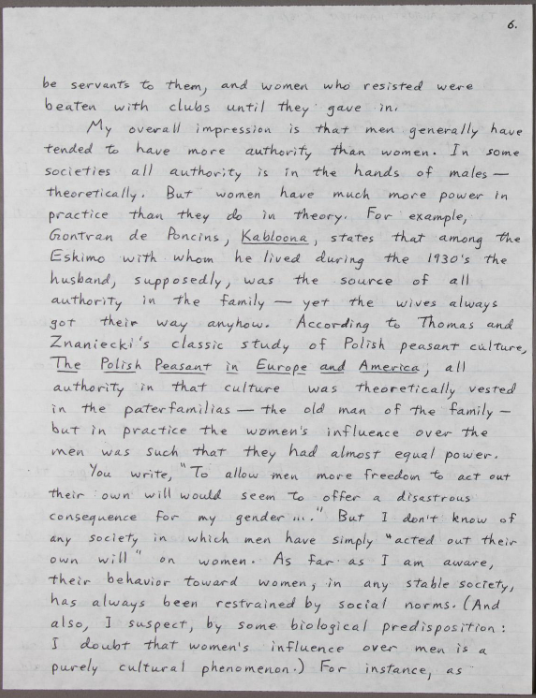

I’m not in a position to speak authoritively about women’s roles in non-industrial societies, because I’ve had no opportunity to research the subject systematically. But I have read about many different societies, and it seems clear that few valid generalizations about women’s roles are possible. The distinguished anthropologist Carlton S. Coon stated in his book The Hunting Peoples that among the Bushmen of the Kalahari Desert men and women had equal status, and this seems plausible in light of what I’ve read about those people. At the other extreme, some of the Australian tribes had religious rituals in which women were subjected to what we would call gang rape, and some of the women lived in terror of these experiences. Moreover, in some tribes, young women were forced to marry old men, primarily so that they should be servants to them, and women who resisted were beaten with clubs until they gave in. My overall impression is that men generally have tended to have more authority than women. In some societies all authority is in the hands of males — theoretically. But women have much more power in practice than they do in theory. For example, Gontran de Poncins, Kabloona, states that among the Eskimo with whom he lived during the 1930’s the husband, supposedly, was the source of all authority in the family — yet the wives always got their way anyhow. According to Thomas and Znaniecki’s classic study of Polish peasant culture, The Polish Peasant in Europe and America, all authority in that culture was theoretically vested in the paterfamilias — the old man of the family — but in practice the women’s influence over the men was such that they had almost equal power.

You write, “To allow men more freedom to act out their own will would seem to offer a disastrous consequence for my gender ....” But I don’t know of any society in which men have simply “acted out their own will” on women. As far as I am aware, their behavior toward women, in any stable society, has always been restrained by social norms. (And also, I suspect, by some biological predisposition: I doubt that women’s influence over men is a purely cultural phenomenon.) For instance, as horrifying as the practices of the Australian tribes seem to us (and apparently also to many of the women concerned), the rapes and beatings were not carried out at the random will of the men but only in particular circumstances prescribed by custom.

The situation of women under the Taliban in Afghanistan I think was an aberration of a disordered and disrupted society.

You state that “Female infanticide, genital mutilation, forced prostitution, forced marriage, and widespread economic and legal discrimination are a fact of life in most of the world.”

There have been and no doubt still are cultures that practice female infanticide, but I would be very surprised if it were a frequent and accepted practice over most of the world. Excision cultures, and it still is in some parts of the not practiced over most of the Middle East, much less over most of the world.{1} I’ve never heard of a traditional culture in which forced prostitution was an accepted practice. Maybe examples could be found, but they certainly would be the exception and not the rule. Forced marriage occurs, but it’s probably less common than you think. Arranged marriages are, or were, very widespread in traditional cultures, but one has to distinguish between arranged marriages and forced marriages. An arranged marriage is carried out under the supervision and control of the family as being a matter that affects the whole family and not just the prospective spouses. But it’s my understanding that the wishes of the prospective spouses commonly are taken into consideration and they usually are not forced to marry if either of them has a decided objection to the match. (Certainly there are exceptions, such as the Australian custom described above.) Furthermore, spirited individuals may often find ways of thwarting their families intentions with regard to marriage. TO take an example from Elizabeth Marshall Thomas’s book The Harmless People, a Bushman fell in love with a beautiful girl and arranged with her parents to make her his wife. He took her back to his hut, but she refused to enter it and slept the night outside. In the morning she got up and walked back to her parents’ camp, and that was the end of the marriage. Even among the Australian Aborigines a young woman might avoid a forced marriage to an old man by eloping with her boyfriend — though in doing so she risked death if her and her boyfriend’s totems were such as to prohibit their marriage. (Aldo Massola, *The Aborigines of Southeastern Australia.)

Economic and legal discrimination against women, in the sense in which I think you mean it, is a trait of societies in a state of transition from traditional to modern culture. In all traditional cultures, men and women had different roles. Through force of custom, the traditional differences in sex roles were carried over into the economic and legal arrangements of societies that were in the process of modernization, and the difference still persists in those societies that have not yet reached the advanced stage of modernization that exists in the West. But the economic and legal discrimination that exists in incompletely modernized countries is a very different phenomenon from the traditional differences in sex roles. You can disapprove of the traditional differences in sex roles if you like, but they still are not the same thing as the economic and legal discrimination that exists in the modern world.

But it is difficult to talk about women’s roles in terms of generalities. ONe gets a much better picture by reading accounts of life in particular cultures. If you’re sufficiently interested, you might want to read some of the books I’ve cited above, or such books as Angie Debe, Geronimo, Colin Turnbull, Wayward Servants and The Forest People, Louis Sarno, Song From the Forest, John D. Hunter, Manners and Customs of the Indians ... (etc, — long title), which will give you some inkling of what life was like for women in certain premodern societies.

My readings in history and anthropology have left me with the impression that, apart from extreme examples such as the Australian customs I’ve mentioned, women in traditional societies undisturbed by Western influence have not ordinarily been dissatisfied with their position as women. But it still seems that, on average, life in traditional societies was harder for women than for men. For one thing, women faced the dangers of childbirth without modern medicine to intervene if anything went wrong. For another thing, treatment of women that we would consider unfair, or at times abusive, was common in some of those societies.

Nevertheless — and I make this suggestion with difference since I’m not a woman, and can’t blame you if you disagree with me vehemently — I venture to propose that the unfairness to women of many traditional cultures was less important than the conditions that modern society imposes on both sexes. Take yourself as an example. You are under medication for depression. Would you have been depressed if you had lived in a male-dominated traditional society? Maybe not. Reportedly, one anthropologist went to New Guinea to study depression there, but was unable to carry out his project because he couldn’t find any depression. So it would seem that any unfairness to which women are subjected in New Guinea is not sufficient to make them depressed; whereas under modern conditions depression is very common.

But so far, for the most part, I’ve been discussing only traditional societies. Today, most of the world has been thrown into cultural disorder by the intrusion of industrial civilization. Societies outside the West may still retain many elements of their traditional cultures, but there are very few in any places left where traditional culture remains reasonably intact. In this disordered state of the world it is certain that, outside of the well-policed West, atrocities are far more common than they were at the hunting-and-gathering stage of human existence. I would guess that atrocities are more common now than they were in most of the older civilized societies too, but that is open to argument. It’s not clear to me whether women are victims of atrocities to a greater extent than men are, but it may not matter anyway, since to a woman who is forced into prostitution it can’t be much of a consolation that a man has been killed, mutilated, or enslaved.

If the existing system breaks down in thee industrialized world, it seems safe to assume that the result will be massive social disorder. Presumably there will be atrocities. Whether women or men will suffer more is an open question, but, again, it may not matter much. However, I see no reason to assume that there would bee a “worldwide backlash against Feminism.”

You can take your choice: You can either desire a collapse of the existing system and accept the disastrous consequences that would ensue; or for the sake of present physical safety you can desire that the system should survive as long as possible, and reconcile yourself to letting technology take us wherever it will take us. You may feel that both alternatives are unacceptable, but I believe that there are no other choices: If the technological system survives at all, there will be no way of taming it, controlling it, or making it harmless.

I’ve now addressed your concern #1 at considerable length; I can respond more briefly to your other concerns.

What you say under #2 seems inconsistent with your earlier statement that you “incur new [bills] just as quickly as the old ones disappear.” Can you clarify? In any case, in #2 and #3 you seem to be asking me to tell you how to achieve personal fulfillment. Even if I were qualified to offer that kid of advice — and I am not qualified — I would not be able to offer it without knowing you well. However I will make some relevant remarks further on in this letter.

Under #3 you say you feel guilty for not having contributed more to people outside of your extended family. But throughout the past history of the world most people have worked only for themselves and for their extended families, or for others to whom they’ve had strong personal ties, and I’m not aware of any indication that anyone ever felt guilty about it prior to modern times.

In your items #4 and #5, you seem to be arguing that the continued development of the system will lead to physical disaster for the human race. I don’t know whether it will or not. The point is much disputed. I do believe that if the development of the system does not lead to physical disaster it will at any rate prove disastrous to traditional human values such as freedom. (Though this doesn’t necessarily mean that most people will some day think they have lost their freedom. Probably they will simply redefine the word “freedom” so that it describes whatever way of life they happen to be leading. In fact, such a redefinition of “freedom” has already taken place.)

I’m not going to address your point #6. My answer would have to be long-winded and probably would not interest you much anyway. So I will only say: (i) It’s not clear to me why you think opponents of industrial society would have to seek solitude. (ii) I’ve never said it would be easy for rebels or revolutionaries to hasten the breakdown of the system, nor do I claim to know to a certainty that it would be feasible at all. (iii) Nevertheless, I think it should be tried.

Your point #7: Without a breakdown of the entire technological system, sympathy for wild nature would mean very little. The reason is clear: Immoderate consumption of natural resources is necessary to maintain the modern lifestyle. Apart from a minority of radicals and rebels, people just will not give up their modern luxuries in order to reduce their impact on the environment. You yourself are a case in point. It’s clear from your letter that your standard of living — and consequently your level of consumption of natural resources — is higher than that of the average person in this country, and incomparably higher than that of Third-World people. Are you going to give up all of your luxuries in order to reduce your impact on nature? Not likely! Of course, other people won’t give up their luxuries either; and Third-World people won’t stop aspiring to attain the Western level of luxury. People will continue their immoderate consumption of natural resources unless and until the breakdown of the system makes the modern lifestyle impossible, or until some other factor, such as the exhaustion of the resources, forces them to stop.

Now let me return to your concerns #2 and #3 — your search for personal fulfillment. I suggest that one of the points the author of the manifesto was trying to make was that, for most people, an activity that is carried on solely for the sake of fulfillment does not bring genuine fulfillment. In order to acheive true fulfillment, you have to have an activity with real goal — not just a goal that you cook up for yourself in order to find fulfillment. But if you had a real goal — if there were something that you really wanted — you would already know that you wanted it and you wouldn’t have to search for it. Hence, the search for fulfillment is futile.

From your letter it appears that your only goal has been to “acquire things ... on [your] long list of must-haves”, but evidently that hasn’t satisfied your need for fulfillment. Now you seem to be looking for something like a hobby, an activity that won’t interfere with your lifestyle or threaten your posession of the “things”. that you’ve acquired.

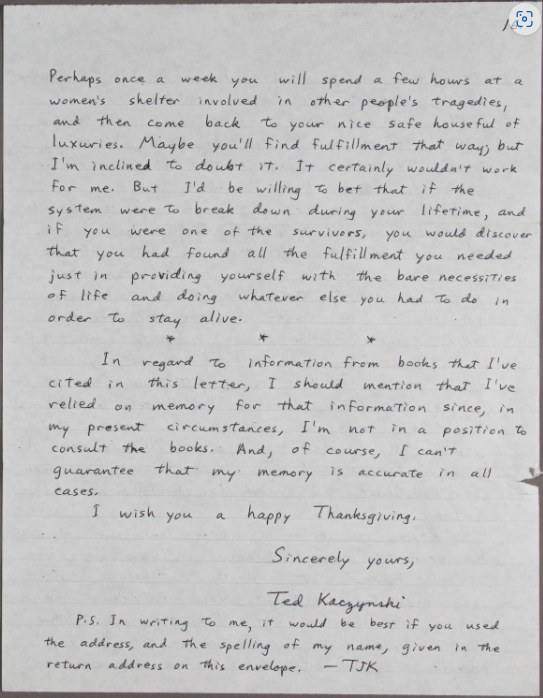

Perhaps once a week you will spend a few hours at a women’s shelter involved in other people’s tragedies, and then come back to your nice safe house full of luxuries. Maybe you’ll find fulfillment that way; but I’m inclined to doubt it. It certainly wouldn’t work for me. But I’d be willing to bet that if the system were to break down during your lifetime, and if you were one of the survivors, you would discover that you had found all the fulfillment you needed just in providing yourself with the bare necessities of life and doing whatever else you had to do in order to stay alive.

* * *

In regard to information from books that I’ve cited in this letter, I should mention that I’ve relied on memory for the information since, in my present circumstances, I’m not in a position to consult the books. And, of course, I can’t guarantee that my memory is accurate in all cases.

I wish you a happy Thanksgiving.

Sincerely yours,

Ted Kaczynski

P.S. In writing to me, it would be best if you used the address and the spelling of my name, given in the return address on this envelope. --TJK

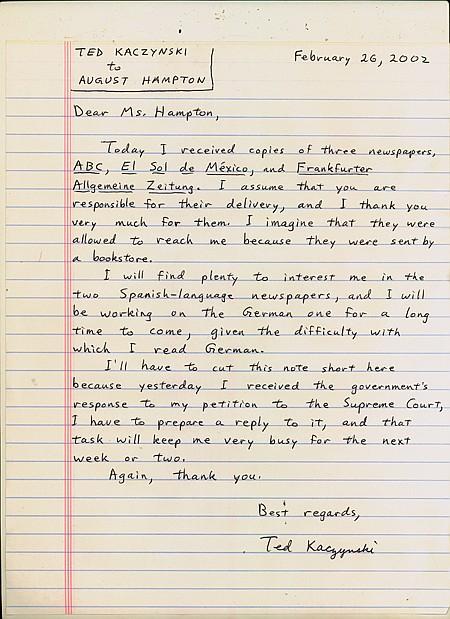

Ted to August — Feb. 26th, 2002

Dear Ms. Hampton,

Today I received copies of three newspapers, ABC, El Sol de Mexico and Frankfurter Allgemeine Zeitung. I assume that you are responsible for their delivery, and I thank you very much for them. I imagine that they were allowed to reach me because they were sent by a bookstore. ...

Best regards,

Ted Kaczynski

Ted to August — Mar. 19th, 2002

Dear Ms Hampton, Of the material that you sent me ...

... to me, Colorado seems almost subtropical. ...

... You asked about my Supreme Court case. I was ...

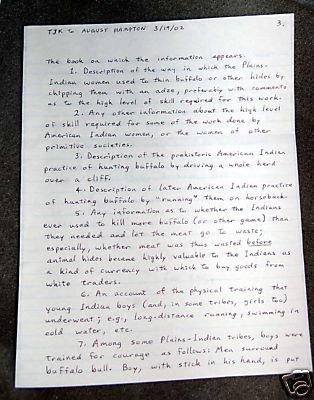

... the book on which the information appears.

1. Description of the way in which the Plains-Indian women used to skin buffalo or other hides by chipping them with an adize, preferably with comments as to the high level of skill required for this work.

2. Any other information about the high level of skill required for some of the work done by American Indian women, or the women of other primitive societies.

3. Description of the prehistoric American Indian practice of hunting buffalo by driving a whole herd over a cliff.

4. Description of later American Indian practice of hunting buffalo by "running" them on horseback.

5. Any information as to whether the Indians ever used to kill more buffalo (or other game) than they needed and let the meat go to waste; especially, whether meat was thus wasted before animal hides became highly valuable to the Indians as a kind of currency with which to buy goods from white traders.

6. An account of the physical training that young Indian boys (and, in some tribes, girls too) underwent; e.g., long-distance running, swimming in cold water, etc.

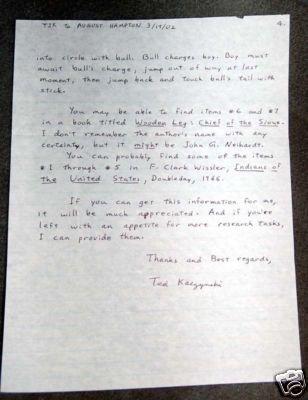

7. Among some Plains-Indian tribes, boys were trained for courage as follows: Men surround buffalo bull. Boy, with stick in his hand, is put into circle with bull. Bull charges boy. Boy must await bull's charge, jump out of way at last moment, then jump back and touch bull's tail with stick.

You may be able ot find items #6 and #7 in a book titled Wooden Leg: Chief of the Sioxe. I don't remember the other's name with any certainty, but it might be John G. Neihardt. You can probably find some of the items #1 through #5 in F. Clark Wissler, Indians of the United States, Doubleday, 1996.

If you can get this information for me, it will be much appreciated. And if you're left with an appetite for more research tasks, I can provide them.

Thanks and Best regards,

Ted Kaczynski

{1} I’ve read that older, traditional people where clitoridectomy is practiced, of both sexes, fail to understand why Westerners get so upset about it. Apparently it is the younger, Wester-influenced people who raise objections. I personally am repelled by the idea of clitoridectomy, but then, I’m a westerner.