Ted Kaczynski's Letter Correspondence With Gary Greenberg

1988

January

1. Gary to Ted

January 24, 1998

Dear Mr. Kaczynski:

Please forgive my intrusion into your life. I am not sure if this letter will gain a sympathetic reading, or any reading for that matter. But after thinking long and hard about writing it, I’m taking the chance.

I would like you to consider allowing me to write a biography of you. I am sure you have had many requests from other people to do this, and for all I know you are already working with someone. Or, for that matter, you may be opposed in principle to the very idea. In the event, however, that neither of these are the case, I hope you’ll read on and think about my request.

I know nothing of you, of course, except what the news media have decided to tell me, so what I am about to say is no doubt presumptuous – it's just my reading between the Iines. It seems to me that you are one of the notable antimodemists of our age. At least since saboteurs hurled their sandals into machines and Luddites rioted in factories, people have deeply (and sometimes violently) objected to the fundamental tenets of the modem world. This protest is not against one or the other work of technology - against, say, nuclear weapons or automobiles - but rather against the world view that underlies and makes possible the creation of any particular machine or device. And, as many antimodernists have discovered, this world view does not tolerate radical protest. It must either co-opt it or eradicate its opposition, the latter through outright killing or mere discrediting. I believe this is one of the reasons that there has been so much interest in finding a psychiatric diagnosis for you: not, as the various lawyers have claimed, to ensure that you are competent or sane to stand trial, but rather to dismiss your protest as the ravings of a lunatic.

I should acknowledge here that I have firsthand knowledge of this misuse of the mental health profession, as I am a psychologist. My research and writing, however, have always been deeply critical of many of the practices of my profession, particularly insofar as it tends to pathologize what it does not understand or cannot tolerate. I have no wish to understand you as "schizophrenic" or "paranoid" or any of the other labels that have seen thrown at you. To the contrary, I wish to tell your story partly in order to show how limiting and harmful those labels can be, both for the person who is labeled and for the society which might otherwise benefit from listening to him or her.

I should also mention that I know something of what it is like to try to live by antitechnological principles. Like many of our generation, I spent a number of years in a cabin in the woods with no plumbing or electricity, trying to live off the land. Circumstances forced me out of my refuge, but I will always remember both the difficulty and the joy of life off the grid. I will always remember the suspicion and outright dislike I aroused in people who could not understand what I was doing. and how precious the few who did understand were to me. Without wishing to seem presumptuous, I think I recognize in your story some of my own, and I think I see in your decision to live as you have an integrity that I deeply respect.

I believe your story deserves to be told with a sympathetic voice in a manner that does justice to the deep truth of your principles. I feel certain that I can tell it this way. I am an experienced writer and interviewer, and I would greatly appreciate the chance to use my skills and talents on your behalf.

If you are interested in pursuing this any further, you are welcome to use the enclosed envelope to write me or to call collect if you can arrange for that. Or, if you like, I can come to see you. Whatever you decide, I wish you well, and I hope to hear from you soon.

Regards,

Gary Greenberg

Unknown Date

2. Ted to Gary

Gary: I wanted to write a magazine profile, perhaps even an entire book, about him. I was, I told him, primarily interested in the way that he had been labeled a madman, a paranoid schizophrenic, when nothing that had appeared in the media about him (except the psychiatrists’ conclusion that he was crazy) supported that view.

My prospective subject was interested enough in the project to ask, through his lawyer, for more information about me. So, during the spring, I wrote Kaczynski a short autobiography. I told him about my therapy practice and my teaching, even a little about my personal life, and I sent him some of my academic writings: two articles and a book. I heard nothing directly, and in midMay 1998, after he’d been transferred to the Supermax prison in Florence, Colorado, I sent him a gentle reminder of my existence. His first letter came in response.

The letter was four pages long. It was written in a precise and blocky print on college-ruled paper. There were no signs of erasures or corrections. The prose didn’t so much flow as march steadily from the beginning of an idea to its end, a flawless parade of logic. The letter was courteous, reasonable, and promising.

First thing he did was he apologized for being so long and getting back to me. Then he told me that he wanted me to know that there were other writers who were interested in his story, but that he was glad to have correspondence with me. It would seem, he said from the articles I'd sent him. I didn't think there was any such thing as objective truth. Did I really think that was the case? For instance? He said. If a nuclear bomb explodes, the consequences are going to be the same for the people who believe that there's such a thing as objective truth and the people who don't. Fairly provocative example. Given who he was.

It would have been easy, in fact, to forget who my correspondent was, if it weren’t for the question with which he started our exchange.

Do I infer correctly that you believe that there is no such thing as objective truth? That all truth is relative to culture, values, attitudes and the like? If this is what you believe, then how would you answer the following objection? Consider the truths of nuclear physics. They tell us that if a device is constructed using a certain quantity of plutonium in such-and-such a configuration, a nuclear explosion will be produced. Anyone within range of that explosion will be incinerated regardless of his culture, values, attitudes, etc. So, just what can you mean by saying that the truths of nuclear physics are relative?

Kaczynski wanted to know about my relativism. But I wanted to know why he chose that particular example.

Even more, I wanted to know how the person who had fashioned this note, with its politeness and sensitivity, its levelheaded clarity, its measured expression of frustration—how this person had spent seventeen years of his life perfecting a technique for building bombs and delivering them to people he didn’t know. It’s hard to square murder or other depraved acts with rationality and the other hallmarks of mental health. But this might be more about the way that medicine, and in particular psychiatry, goes proxy for morality than about the psychopathology of Ted Kaczynski or any other murderer.

Kaczynski had thought about this, which is probably why he responded to my pitch. He had a personal stake in this question, after all. He wanted to prove that he wasn’t mentally ill. Or, to put it another way, that his behavior needed to be debated in the old- fashioned terms of good and evil.

A. Gary to Ted

Gary: I wrote the preface to Michael Mellows book, the Forward actually, where I sort of systematically picked apart these psychiatric evaluation. I sent that to Kaczynski.

And all of this time he and I were engaged in this long cat and mouse game about whether or not he was going to sit for an interview with me. Would I be the first person to get an interview with the elusive Unabomber? Wouldn't that put me on the map landing the great white whale of the interview with Kaczynski, lunch with people in New York, a contract? All sorts of ****.

Think of this as an audition. Here's how I'll write about you. And I sent him the forward.

B. Ted to Gary

Gary: And he loved it. Superb. I got an A from Professor Kaczynski on my paper.

On the basis of this audition, I got the job of coming out to Colorado to interview him.

C. Ted to Gary

Gary: [Micheal Mello had] gotten a letter from Kaczynski expressing anger and disappointment in me for lying to him about certain arrangements. He thinks you have a contract to write an article about him for the New York Times Magazine, which I that just wasn't true. And I said, Ohh well, it sounds like a big misunderstanding. You know, it's like bound to happen. Then I got the letter. What Mel hadn't told me was that the source for all this information was. Michael Mello. Kaczynski, you know, quoted me in classic Ted Kaczynski. Footnotes and everything else. He quoted me. Passages from Michael Mellon's letters to him, which made it clear that Michael had been talking about me to Kozinski for months.

D. Gary to Ted

Gary: I was on the inside and yet simultaneously I was on the outside. For a moment there I could see from his point of view. Here's a guy he's in jail. He doesn't really know what's going. On he's never met any of these people. He's got an obscured view. He's got all sorts of people whispering in his ear about everything. He's gone a long way toward trusting me. He gets this information. It's disturbing to him because he feels really exposed, really vulnerable. I sent the letter off. I just said, hey, you know, this is what's been going on. There's no New York Times magazine article. There's no agent. I've been discussing these things. It's not made-up out of whole cloth, but there's been some embroidery here.

E. Ted to Gary

Gary: Your explanation is perfectly acceptable. He says it's quite satisfactory, and then he expresses relief. I'm glad that you are able to explain yourself because I have come to think of you as one of my favorite correspondents and I, you know, essentially he didn't want to. Have to write me off.

In the mean time, Michael Mello, his response to that was to write essentially a poison pen letter. He said to Kaczynski that he was forced to conclude that I was untrustworthy and irresponsible and a braggart. Because I must have been telling mellow stories. That was a fatal blow, and I knew that as soon as I saw it.

A couple weeks later, I got another letter retracting the apology. You know, "I've been aware of these inconsistencies for some time, but I refrained from saying anything because I wanted to see how far you would go."

F. Gary to Ted

Gary: It was impossible to argue with any of this. Of course I wanted to use Kaczynski's stories to tell my own. So I agreed with him:

While I am disappointed with your turning me down, I am neither surprised nor mystified.... I know I am a pig in a poke from your perspective, and I am pleased to have gotten so far with you as to even be talking about these things. While I remain hopeful that you might change your mind (and grateful that you hold that possibility open), I respect your decision and the reasoning on which it is based. As I have said many times, I don't know how I would act, were I in your situation.

I reassured him about my scholarly intentions:

I think that the best reassurance I can give you is to remind you that I have no interest in offering you a "better" evaluation and/or diagnosis than the other shrinks have. I'm not interested in diagnosing you; I would be hard-pressed to think of a less interesting way to write about you than trying to fit you into one of the categories in the DSM. Even if I could find one, then what would I have said? The way that my expertise as a psychologist enters into this picture (besides giving me a credential that will make it possible that people will actually listen to me; I know that's cynical, but it's true) is that I know from the inside the inadequacies of diagnosis, and in general the problems related to power embedded in the mental health industry. In my last letter to you, I tried to outline how I can use my credentials and knowledge to this end.

And my personal intentions:

I don't think you are doing me an injustice, nor is there any reason (from my end) that your decision should strain our relations. I only hope that I have not strained our relations by asking in the first place. I think I have already told you that there is no quid pro quo in my request for a meeting. We can continue, I hope, to correspond, and as circumstances change perhaps your decision will change as well. In the meantime, this process (where-Ver it leads) can only help us to get to know one another better.

I pushed:

Here is an idea. If what I have written here inclines you to further contact with me, then consider my proposal [for an interview} to you in the last letter. Think of it as a trial run, an audition.... You can let me interview and write about you and then see if you like what I do in a relatively low-risk setting. This will give you a crucial piece of information about me: whether or not I can be trusted with your words, and whether or not I am true to my own. It will also give you the chance to meet me face-to-face and fill in your picture of me. Again, I think the bird-to-stone ratio is favorably high.

I backed off:

I know it remains possible that all my reassurances and attempts to address your concerns might not be enough. Thus far, that is the case, and so I have no choice but to give up on [the interview] for now and seek other ways to enlist your aid.

And it almost worked.

1999

May

G. Gary to Ted

Gary: In early May, I wrote Kaczynski to register my protest at his unauthorized use of my paper. By then, a version of the ex-foreword; called "Diagnosis and Dissent," was out for peer review, and I didn't think that its use in his brief was going to be helpful to my cause, particularly since I hadn't disclosed it to the editor. It might seem like I was trying to use an academic journal as a platform for a Unabomber apologia, so I asked Kaczynski to help me clarify the situation for the peer reviewers. And, I told him, it rankled me that he was the one who spoke out of church; I wanted an explanation.

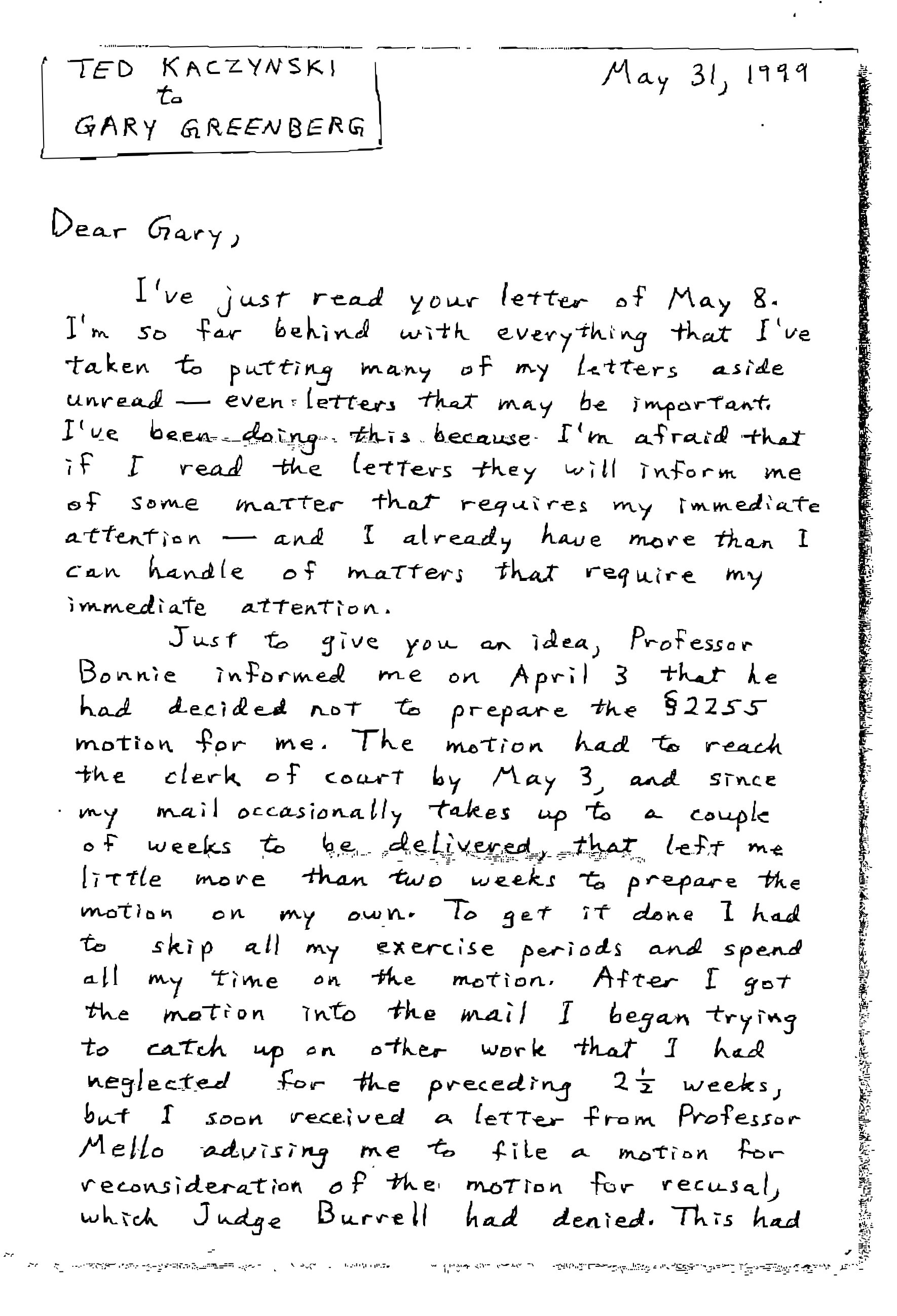

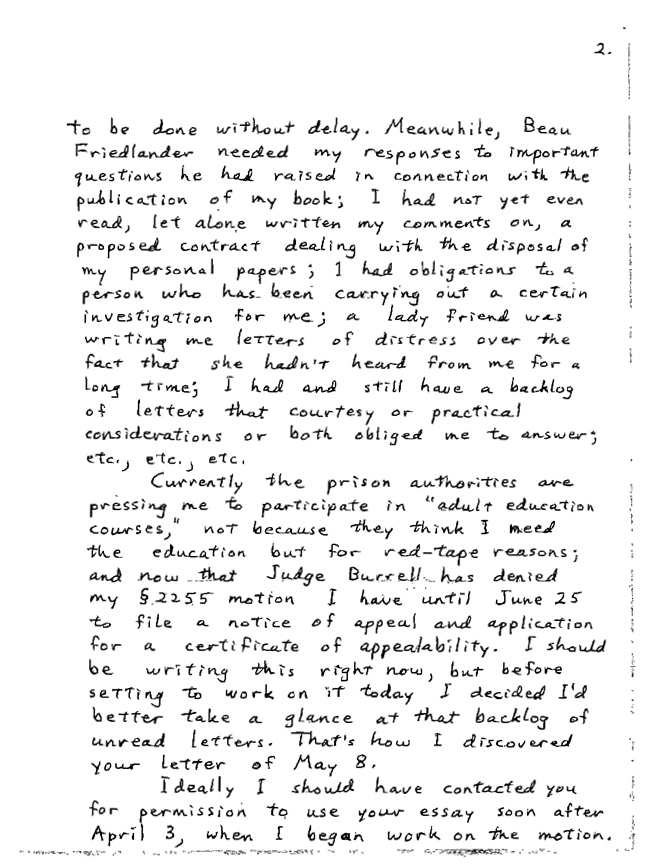

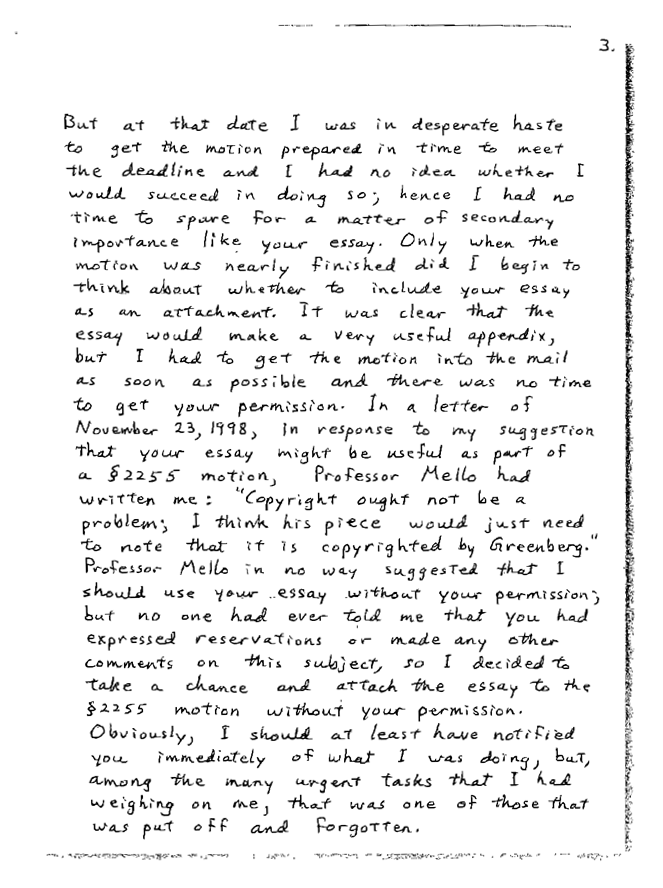

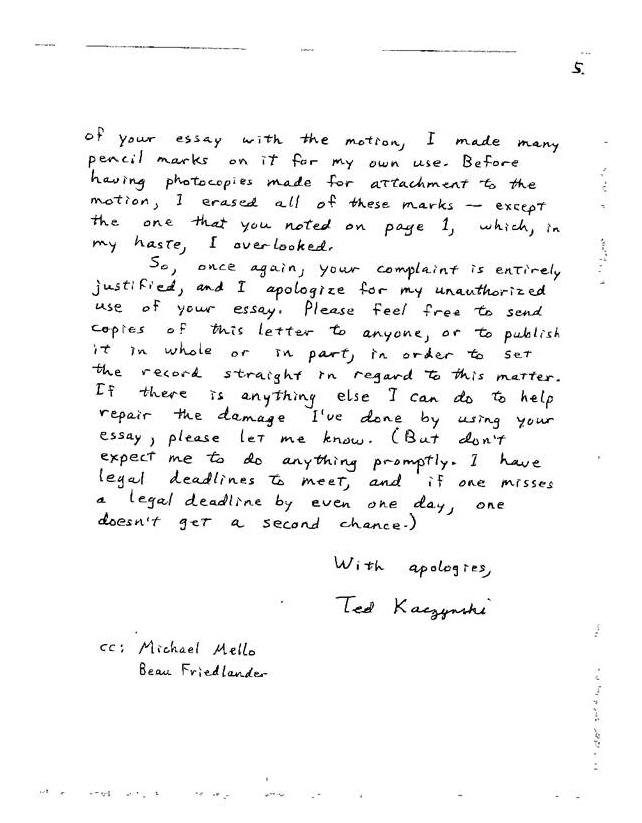

H. Ted to Gary #1

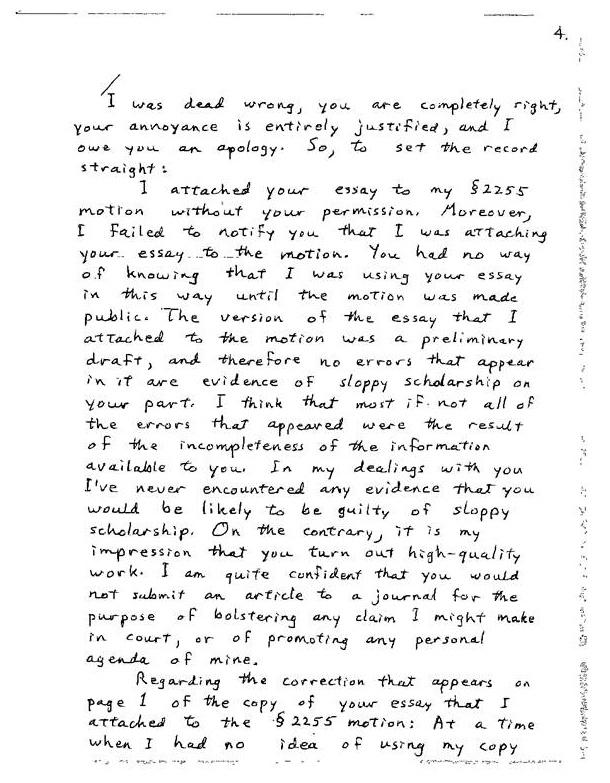

Gary: Kaczynski apologized. Completely and unconditionally. In two separate letters. The first, signed, "With apologies," was about the logistical reasons that he had used my essay without permission.

I. Ted to Gary #2

The personal part came in a second letter, signed with our familiar "Best regards," acknowledging that his betrayal was in response to mine, and adding that he liked my essay about Hugh Scrutton, aversion of which I had sent him some months before.

June

J. Ted to Gary #3

I got a third letter the next day. In it, he told me that he'd had some time for leisure reading, and he'd come across something in The New York Review of Books that he thought I'd be interested in. It was a passage from an article by Edmund S. Morgan about slavery.

Running away [from slavery] could be treated as abnormal, deviant behavior. One New Orleans physician diagnosed it as "drapetornania, or the disease causing Negroes to run away." It was, he insisted, "as much a disease of the mind as any other species of mental alienation." The norm was happy childlike Negroes who loved their masters and deserved punishment if they failed to do what they were told.

One last thing: to set the record straight, Kaczynski gave me permission to publish the apology letter.

Unknown Date

K. Ted to Gary

I got this letter from him. It's a very provocative letter. It's a chilling letter, ongoing argument about whether or not there's such a thing as objective truth. He says. “I thought we'd settled that long ago,” and indeed it was the subject of his 1st letter to me. “This is something that you would do well to remember, either about nuclear explosions. Or about other little tricks that physics can play. Best regards, Ted.”