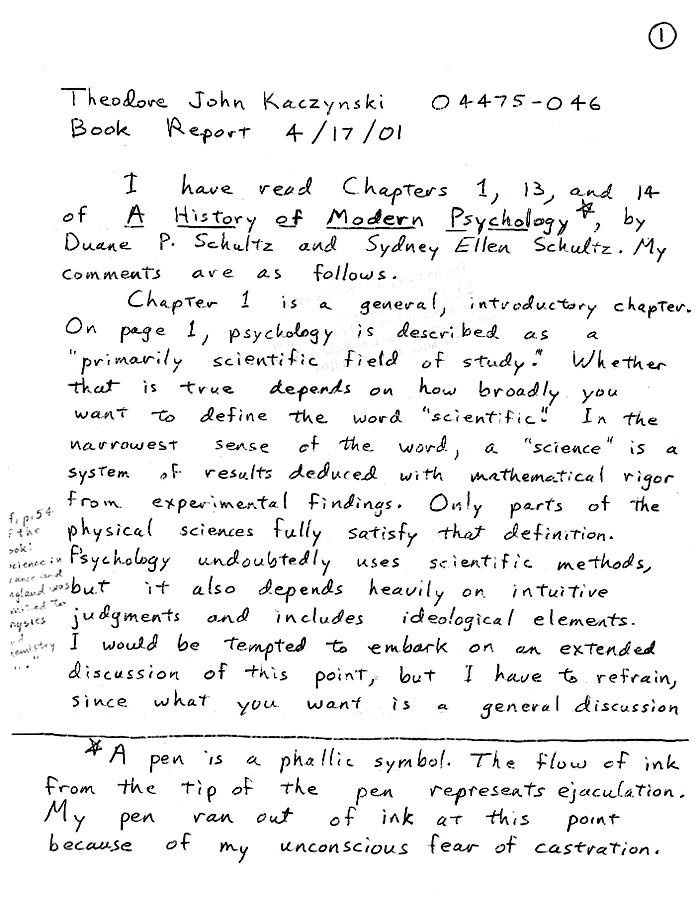

Ted Kaczynski’s Review of ‘A History of Modern Psychology’

Theodore John Kaczynski 04475–046

Book Report 4/17/01

I have read Chapters 1, 13, and 14 of A History of Modern Psychology{1}, by Duane P. Schultz and Sydney Ellen Schultz. My comments are as follows.

Chapter 1 is a general, introductory chapter. On page 1, psychology is described as a “primarily scientific field of study.” Whether that is true depends on how broadly you want to define the word “scientific.” In the narrowest sense of the word, a “science” is a system of results deduced with mathematical rigor from experimental findings. Only parts of the physical sciences fully satisfy that definition. Psychology undoubtedly uses scientific methods, but if also depends heavily on intuitive judgments and includes ideological elements. I would be tempted to embark on an extended discussion of this point, but I have to refrain, since what you want is a general discussion of what I’ve read and not an in-depth exploration of a single issue.

[IN MARGIN LEFT OF ABOVE PARAGRAPH: ILLEGIBLE, POSSIBLY “p.54 of the book: Science in France and England was limited to physics and chemistry”]

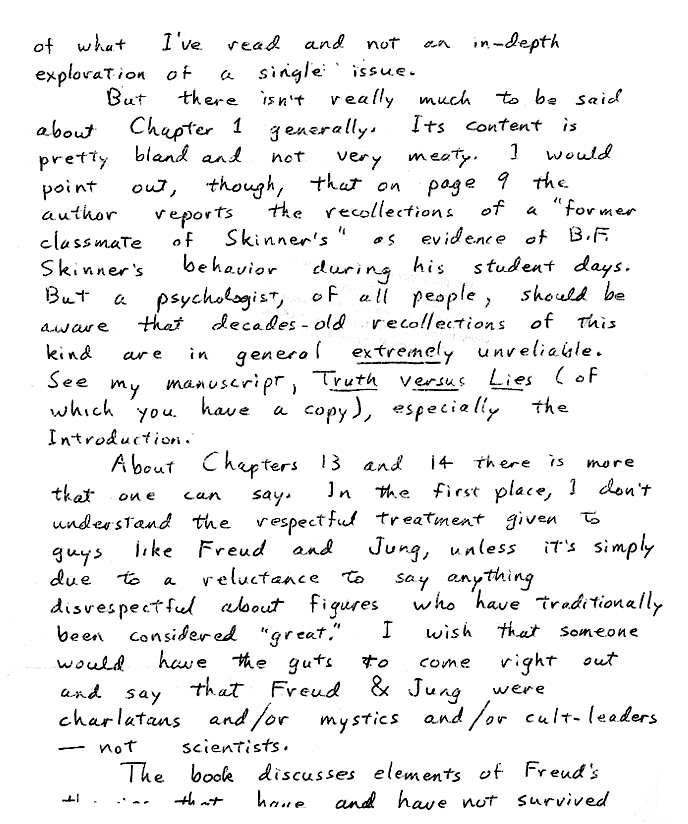

But there isn’t really much to be said about Chapter 1 generally. Its content is pretty bland and not very meaty. I would point out, though, that on page 9 the author reports the recollections of a “former classmate of Skinner’s” as evidence of B.F. Skinner’s behavior during his student days. But a psychologist, of all people, should be aware that decades-old recollections of this kind are in general extremely unreliable. See my manuscript, Truth versus Lies (of which you have a copy), especially the Introduction.

About Chapters 13 and 14 there is more that one can say. In the first place, I don’t understand the respectful treatment given to guys like Freud and Jung, unless it’s simply due to a reluctance to say anything disrespectful about figures who have traditionally been considered “great”. I wish that someone would have the guts to come right out and say that Freud & Jung were charlatans and/or mystics and/or cult-leaders — not scientists.

The book discusses elements of Freud’s [ILLEGIBLY CUT OFF BY SCAN, POSSIBLY “thinking”] that have and have not survived scientific testing (pages 396–97) (to a slight extent also Jung’s theories, pp. 411–12, Adler’s theories, pp.416–17, and those of others). But I think this is somewhat beside the point. It’s obvious that at least some of the phenomena described by Freud are real. Anyone who has ever had a wet dream knows that dreams can be an outlet for urges that are suppressed during waking hours; anyone who is carefully introspective will sometimes catch himself rationalizing or displacing aggression; and some of the other phenomena listed on page 390 of the book can be at least speculatively inferred from informal observation of human behavior. If such observations can seldom be proved, they at any rate provide plausible hypotheses about what makes certain people tick in certain circumstances.

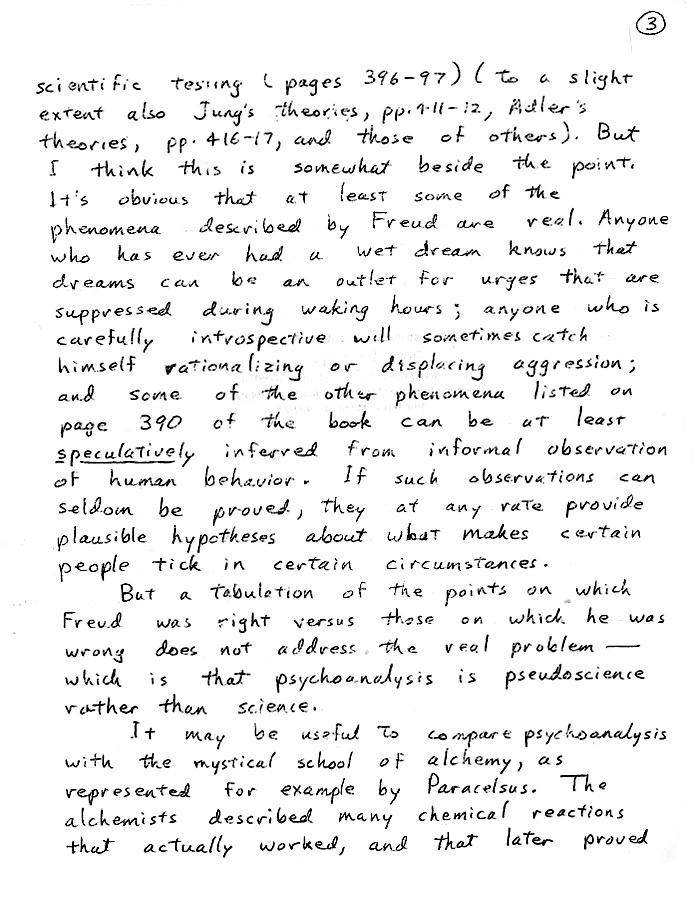

But a tabulation of the points on which Freud was right versus those on which he was wrong does not address the real problem — which is that psychoanalysis is pseudoscience rather than science.

It may be useful to compare psychoanalysis with the mystical school of alchemy, as represented for example by Paracelsus. The alchemists described many chemical reactions that actually worked, and that later proved useful to genuine scientists. But what was really important to the alchemists was not their experimental results but the mystical theories and the mumbo-jumbo that they built up around those results.

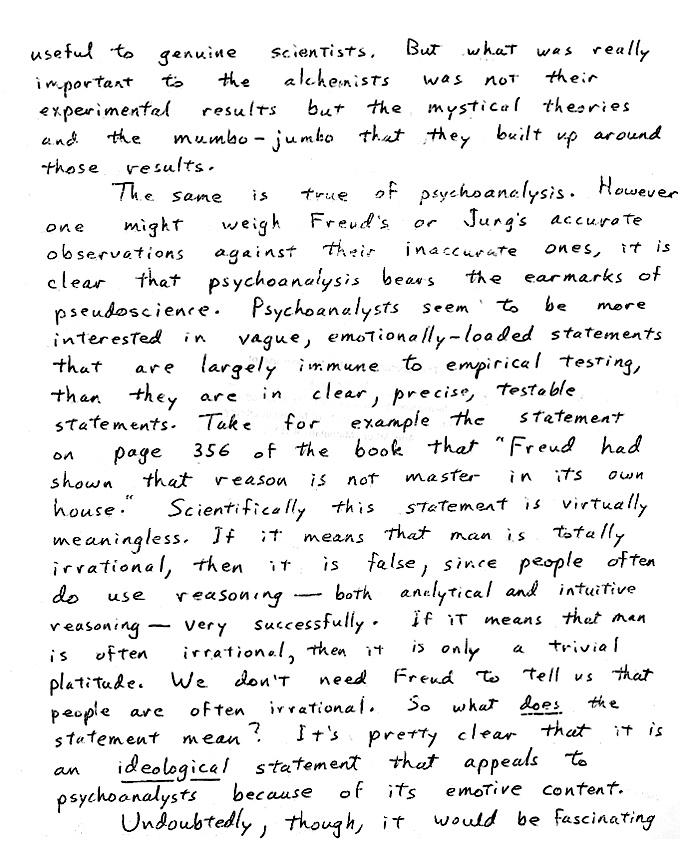

The same is true of psychoanalysis. However one might weigh Freud’s or Jung’s accurate observations against their inaccurate ones, it is clear that psychoanalysis bears the earmarks of pseudoscience. Psychoanalysts seem to be more interested in vague, emotionally-loaded statements that are largely immune to empirical testing, than they are in clear, precise, testable statements. Take for example the statement on page 356 of the book that “Freud had shown that reason is not master in its own house.” Scientifically this statement is virtually meaningless. If if means that man is totally irrational, then it is false, since people often do use reasoning — both analytical and intuitive reasoning — very successfully. If it means that man is often irrational, then it is only a trivial platitude. We don’t need Freud to tell us that people are often irrational. So what does the statement mean? It’s pretty clear that it is an ideological statement that appeals to psychoanalysts because of its emotive content.

Undoubtedly, though, it would be fascinating to know more — scientifically, to the extent possible — about unconscious processes in our brains. The book, on page 397 cites some [ADDED LATER: purportedly scientific] books and articles on unconscious processes. I don’t know whether it is within the scope of your job description to get copies of articles for inmates, but if it is, I would be interested to read the following articles cited in the book:

-

N. Brody, “Introduction: Some thoughts on the unconscious,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13, 293–98 (1987)

-

Jacoby & Kelley, “Unconscious influences of memory for a prior event,” Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 13, 314–336 (1987)

-

Motley, “Slips of the Tongue,” Scientific American, 253, 116–127 (1985)

-

Silverman, “Psychoanalytic Theory: ‘The reports of my death have been greatly exaggerated,’” American Psychologist, 31, 621–637 (1976)

Regarding Henry A. Murray, discussed on pages 424–27 of the book: Scharlette Holdman, the chief investigator of my case, did some poking in Murray’s background and, among other things, she learned that Murray and his mistress, Christiana Morgan, had a whip that they called “the black whip that hurts.” They used to get sexual gratification from chasing each other around the room with the whip and whipping each other. I hasten to add that I received this information from Holdman orally, and her oral reports (as opposed to her written ones) have not proved reliable.

{1} A pen is a phallic symbol. The flow of ink from the tip of the pen represents ejaculation. My pen ran out of ink at this point because of my unconscious fear of castration.