Ted’s Notes on his Journals (Feb. 1996)

Personal Papers

Series I. Contains ideas and quotations. #6 contains also some personal material, but not overly intimate.

#1. June 7, 1969 to Jan 22, 1970

#2. Feb 1, 1970 to Nov. 19, 1970

#3. Nov 30, 1970 to May 14, 1970

#4. June 7, 1971 to Dec 6, 1972

#5. Dec 9, 1972 to Dec 9, 1974

#6. Jan 3, 1975 to May 19, 1975

#7. Dec 20, 1975 to May 3, 1997

Series II. Outdoor journal — camping out.

#1. June 8, 1972 to Aug 7, 1972

#2. Sept 8, 1972 to Oct 26, 1972

#3. Feb 10, 1974 to Aug 28, 1974

#4. June 5, 1975 to Feb 6, 1976

#5. May 18, 1977 to Jan 26, 1978

#6. June 26, 1979 to Oct 23, 1979

Series III. Outdoor journal — at cabin, but #6 and #7 contain also some camping-out experiences

#1. Dec 1, 1971 to April 22, 1972

#2. April 27, 1972 to Oct 1, 1972

#3. Oct 2, 1972 to Nov 4, 1972

#4. June 24, 1973 to May 28, 1974

#5. May 31, 1974 to Sept 14, 1975

#6. Sept 14, 1975 to Feb 25, 1977

#7. Feb 28, 1977 to April 22, 1978

#8. Jan 25, 1980 to May 18, 1980

Series IV. Outdoor stuff at cabin mixed with highly personal stuff.

#1. June 9, 1979 to June 22, 1979

Series V. Personal experiences, outdoor or city; ideas and quotations; coded stuff (code probably breakable).

#1 June 22, 1980 to Jan 16, 1984

Series VI. Highly personal stuff. #4 also contains ideas and quotations.

#1. Sept 20, 1972 to Nov 12, 1972

#2. July 17, 1978 to Aug 23, 1978

#3. Letters of Aug 25, 1978 and Sept. 2, 1978

#4. Aug 29, 1978 to May 8, 1979

#5. Jan 6, 1975 to March 30, 1975

Series VII. Outdoor experiences, ideas and quotations.

#1. Jan 23, 1984 to March 3, 1986

#2. Sept 14, 1984 to Jan 26, 1993

#3. April 1, 1986 to June 22, 1990

#4. Nov 24, 1993 to Jan 23, 1996

Map

Autobiography

Coded stuff (unbreakable code)

Notes on my Journals

Series I, #1, pp. 11–12. Actually, Stefansson’s remark is not accurate. The Kalahari Bushmen are said to have little religion. The Siriono of Eastern Bolivia have no religion at all (see Allan R. Holmberg, Nomads of the Long Bow). The Ituri Pygmies studied by Colin Turnbull (The Forest People) certainly had less religion than the highly-developed civilization of medieval Europe, and their religion contained surprisingly little irrationality. (See also Turnbull’s Wayward Servants.)

Series I, #1, pp. 76. That the situation would last “forever” was certainly too hasty a conclusion. To engineer such a system of society so that it would have a high degree of stability is probably a far more difficult task than I imagined when I wrote those lines.

Series I, #1, pp. 83. It is doubtful that the scientists who made these predictions actually believed them. Very likely they were just trying to frighten people into being concerned about air pollution. But, whether they believed them or not, the predictions were irresponsible, and probably did more harm than good, because these scientists were “crying wolf”, and the fact that such predictions have proved so grossly inaccurate has made many people scoff at all predictions of environmental damage.

Back in 1969, I had a much higher opinion of the competence and honesty of scientists [ADDED LATER: than I do now], so I was then much more concerned about these predictions than I would be today.

Series I, #2, pp.115–118. Clearly I was at that time naive (and so was the author of the remarks in the newspaper clipping) in vastly overestimating the extent to which persons possessing unlimited authority could control the development of a society. Actually, even totalitarians can only to a very limited extent control the development of an industrial society or assure its stability. Totalitarians can control any individual member of the society, but, owing to the extreme complexity of the system, the ability to control individuals does not imply the ability to control the system as a whole. Thus the Soviet Union blundered into an economic mess that led to a social and political revolution, and those socialist countries that have alleviated their economic problems have been able to do so only through partial liberalization. But notice that this liberalization did not come through the kind of gradual, peaceful process envisioned by the liberal intellectuals, but was forced on the socialist world by critical economic problems.

Series I, #3, p.250. I don’t doubt that effective control of human behavior is possible, but I now think that the extent to which the behavior of an uncontrolled human being can be predicted is very much an open question. I am not suggesting that human behavior is based on anything but the laws of physics and chemistry; but it now appears that even purely deterministic processes are not necessarily predictable in practice. Bear in mind the “butterfly effect.”

Series I, #3, pp.253–254. The name “Nicomus Bagley” is fictitious. The quotation actually is from a book of Adolf Hitler’s speeches titled “My New Order.” I was a little embarrassed to put a quotation of Hitler in my notebook.

Series I, #3, p.284. I no longer believe in population-control laws, On the contrary, I hope the population explosion gets completely out of hand, because that will increase the likelihood that the system will collapse. Once the technological system is gone, population will decrease very rapidly, because without modern technology it will be impossible to produce and distribute enough food to supply such an enormous number of people.

Series I, #4, p.25. A totally planned society, or even a totally planned economy, most likely is impossible. See the five principles of history formulated in “Industrial Society and its Future,” and remember the butterfly effect. But it is still true that the tendency of the system is to exert ever-greater control over the individual.

Series I, #4, p.51. Mr. Dunkle was wrong, but not completely wrong. Montana’s population certainly has grown since 1971. [CROSSED OUT: I think it’s almost doubled by now (1996).]

Series II, #5, p.26. As to why the grouse were all male: I concluded that the wing-flapping sound they make as they fly into and out of the tree is their mating call, by which they attract females, just as blue grouse make a kind of grunting sound and ruffed grouse drum on a log with their wings. I’ve noticed that blue grouse use a wing-flapping sound to communicate, though it’s not their mating call. If you come on a blue grouse that is grunting, and has thereby attracted some females, and if you get close enough to frighten the birds so that they fly into the trees, then, a few moments after they have landed in the trees, each bird will flap its wings loudly by briefly. I believe they do this to signal their location to one another, so that the group can stay together and continue their mating ritual after the danger is past.

Series II, #5, p.71. I think I now know why I had trouble with my guts during that period. I wasn’t eating enough! Since then, I’ve observed that my guts function well if I get enough calories so that I have a bowel movement every day; but if I don’t get enough calories, then my guts start retaining the food, presumably to extract all of the calories from it; hence they are many days when I miss my bowel movement. This happens even if I am consuming plenty of fiber. If I miss too many bowel movements I find that I run a high risk of the following: I eat a meal, and then anywhere from a few minutes to an hour afterward, my guts start grumbling and griping and I get violent diarrhea, so that everything comes out except the meal I’ve just eaten. Then for at least a day afterward my guts feel sickish. And for some time after that my digestive system doesn’t feel as if it is functioning just right. However, I find I am more likely to have this problem if I am eating a lot of meat, so difficulty in digesting large amounts of meat may be a factor.

Series II, #5, p.117. Here’s something that I remember pretty clearly about catching that rabbit alive; I don’t know why I didn’t mention it in my notes. In pulling the rabbit out, I tore a large patch of his skin (snowshoe hares’ skins are very fragile). I had wanted to let the rabbit go, from pity, but I was afraid that I might be doing it a disservice if I let it go, because the wound probably was very painful, and with so much of its body deprived of fur the rabbit might die of cold anyway.

Series II, #5, p.130. I now (Feb, 1996) Feel very sorry about the fact that, in a few cases, I tortured small wild animals (two mice, one flying squirrel, and one red squirrel, as far as I can remember offhand) that caused me frustration by stealing my meat, damaging my belongings, or keeping me awake. There were two reasons why I tortured them. (1) I was rebelling against the moral prescriptions of organized society. (2) I got excessively angry at these animals because I had a tremendous fund of anger built up from the frustrations and humiliations imposed on me throughout my life by organized society and by individual persons. (As any psychologist will tell you, when you have no means of retaliating against whomever or whatever it is that has made you angry, you are likely to vent your anger on some other object.) When I came to realize that I had taken out on these little creatures the anger that I owed to organized society and to certain people, I very much regretted having tortured them. They are part of nature, which I love, and therefore they are in a way my friends, even when they cause problems for me. I ought to save my anger for my real enemy, which is human society, or at least the present form of society. I have not tortured an animal for many years now. However, I have no hesitation about trapping and killing animals that cause problems for me, provided they are animals of the more common kinds.

Series II, #6, whole thing. I think part of the reason why I used to get so tired on those long sojourns in the woods was that I wasn’t eating enough. I used to reduce to a minimum the amount of civilized food that I ate, in order to be able to stay out in the woods longer.

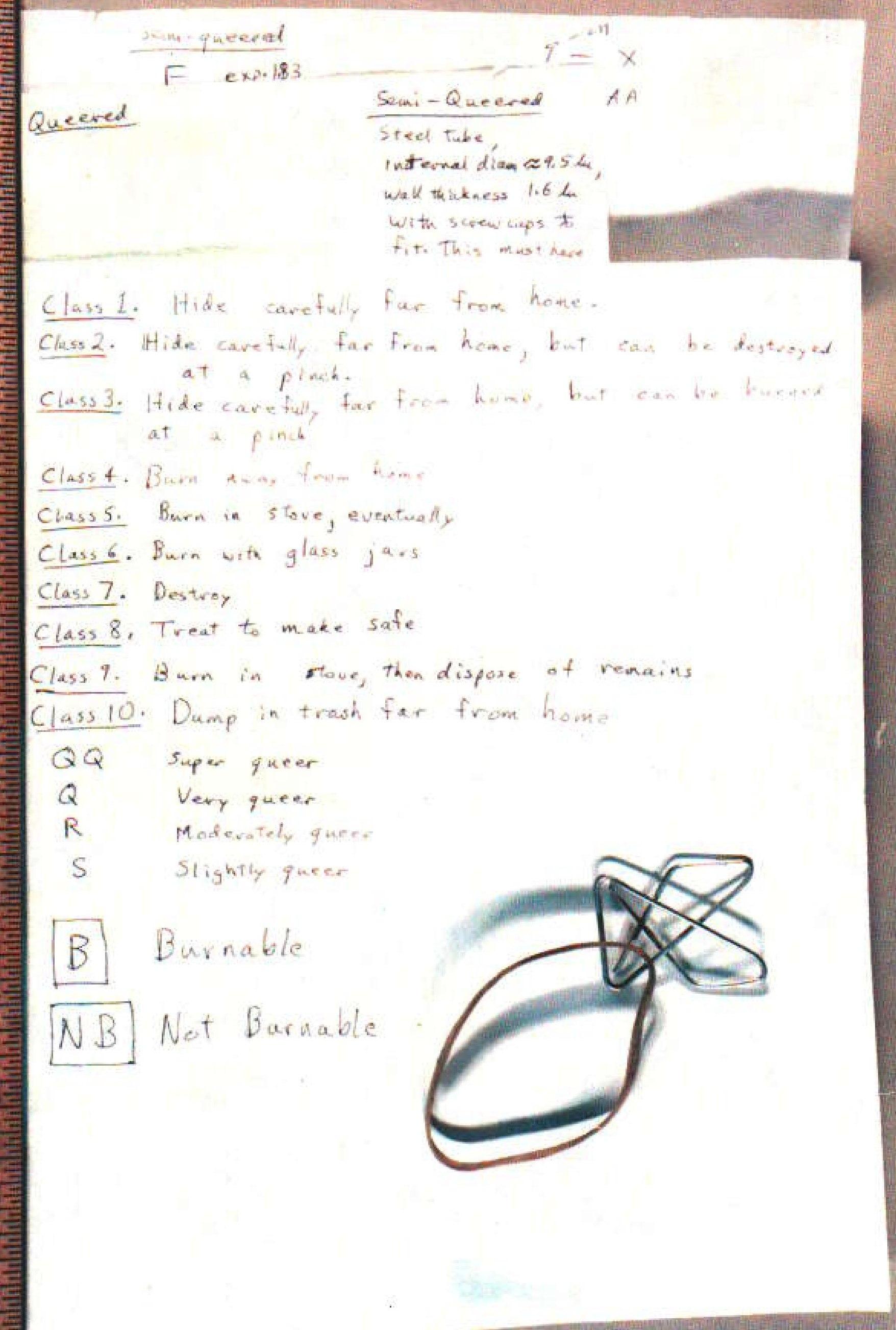

Queered: scale 0 to 10

0 is not queered at all

10 is utterly, maximally queered

Personal: Scale 0 to 3

0 not personal at all

3 very intimate

Poaching

Harmless

Queer #1—embarrassing but not dangerous;

Queer #2—embarrassing, not dangerous, but past the statute of limitations;

Queer #3—embarrassing, not dangerous, past the statute of limitations, but very bad public relations; ...

Queer #10—Most sensitive, embarrassing, incriminating, and dangerous.

Class 1. Hide carefully far from home.

Class 2. Hide carefully, far from home, but can be destroyed at a pinch

Class 3. Hide carefully, far from home, but can be burned at a pinch

Class 4. Burn away from home

Class 5. Burn in a stove, eventually

Class 6. Burn with glass jars

Class 7. Destroy with glass jars

Class 8. Treat to make safe

Class 9. Burn in stove, then dispose of remains

Class 10. Dump in trash far from home

QQ Super Queer

Q Very Queer

R Moderately Queer

S Slightly Queer

B Burnable

NB Not Burnable

Useful notes for manuscript

Series I, #1, pp. 12–13 (George Sanders)

Series I, #6, p.12. “There are frequent transfers of Forest Service personel from one post to another, a practice that reduces loyalty to a specific community and increases dependence on the Service.”

Series I, #1

pp.17–19 queer 8

pp.19–20 queer 2

pp.21–28 queer 5

pp.30–36 queer 5

pp.37–38 queer 6

pp.39–80 queer 8

pp.88–90 queer 2

pp.90–114 queer 7

Series I, #2

p.115 queer 7

pp.127–128 queer 2

pp.123–127 queer 8

pp.133–134 queer 6

p.136 queer 2

p.138 queer 8

pp.139–140 queer 7

p.143 queer 8

p.145 queer 4

p.149 queer 9

p.150 queer 5

pp.152–153 queer 5

pp.152–164 queer 8

pp.180–195 queer 8

pp.200–201 queer 6

pp.202–204 queer 2

pp.204–207 queer 8

pp.207–214 queer 9

Series I, #3 pp.261–262 0 queer 9

p.276–283 queer 10

Almost all the rest of the notebook is queer 8

Series I, #4. Might as well call the whole notebook queer 8.

Series, #5. pp.111–115 queer 10

p.p. 138–139 queer 10

Might as well call all the rest of the notebook queer 8

Series I, #6 Queer 10

Series I, #7 Queer 8

Series II, #1, no queer

Series II, #2, no queer

Series II, #3, p.29 queer 1 (embarrassing, not dangerous)

p.56 queer 2 (but past statute of limitations)

p.64 queer 7

p.82–86 queer 7

p.102 queer 1

p.105 queer 3

p.120–121 queer 2 (but past statute of limitations)

Bad Public relations

Series II, #4. Call this notebook queer 3. But very bad public relations.

Series II, #5, up to p.121, queer 2 (but past statute of limitations)

p.122-to end, queer 9