Thomas Doherty

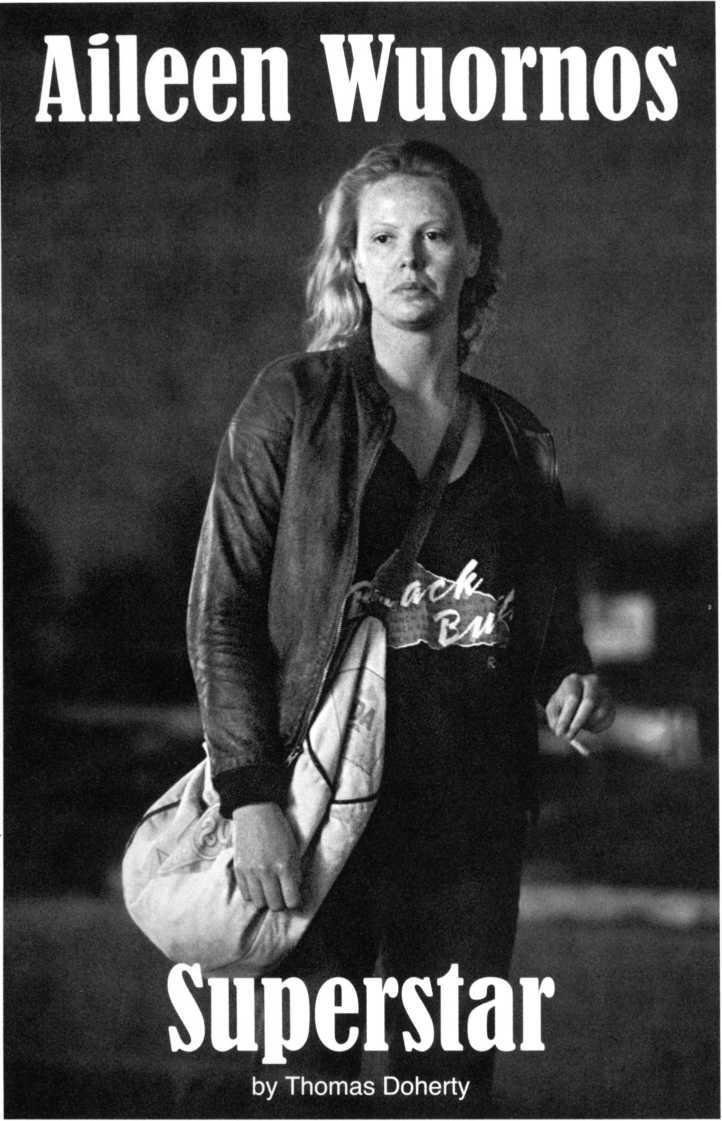

Aileen Wuornos Superstar

Outlaws we love, gangsters we admire, mobsters we respect, but serial killers—well, serial killers creep us out. This is not to say that we are not fascinated by them, that we are not hypnotized by their true-crime exploits in books, motion pictures, and enough video biodocs to clog a basic cable channel (SK- TV anyone?), only that the unabashed affection we bestov/ upon our more traditional criminal archetypes is withheld from the multiple murdering sociopath. If junior plays at being Jesse James or John Dillinger, he’s a normal, rambunctious lad. If he wants to grow up to be Ted Bundy, he’s a candidate for long-term therapy and heavy-duty pharmaceuticals.

As the gendered pronouns indicate, serial killing is a man’s game. Thus, in January 1991, when news broke that a Florida prostitute named Aileen “Lee” Wuornos had achieved the homicidal equivalent of crashing through the glass ceiling, a made-for-TV scenario arrived ready-made. Though genre purists may argue that Wuornos’s lucid motives (robbery and revenge) and singledigit body count (seven male victims) disqualify her from competition with the big boys, her place in the true-crime pantheon being attained through affirmative action not individual merit, a serial killing female, as Samuel Johnson might have said, is impressive not for her level of expertise but for the fact that she is doing it at all. Two motion-picture biopics, a future double bill for lazy film programmers, attest to the prurient attraction of a distaff twist on a patriarchal preserve: Nick Broomfield’s low- tech documentary, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, and Patty Jenkins’s “based on a true story” docu-drama, Monster.

Wuornos and British filmmaker Broomfield go way back. He first glommed on to her notoriety in Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1992), a droll, shaggy dog doc that reveled in the blood sport media journalism it excoriated. Viewed today, the documentary plays like a homage to the golden age of syndicated tabloid TV and if- it-bleeds-it-leads local newscasts. (“Killers may be murdering with a feminine touch!,” teases a bubbly Miami newsbabe in a vintage video clip.) With calculated guile, Broomfield reverses the standard Anglo-American dynamic by casting himself as a pure-hearted pilgrim wandering amidst the seedy hustlers and serious weirdos. Rivaling the killer herself for pride of place are Aileen’s clueless pot-smoking attorney Steve Glazer, who repeatedly pleads “No contest” for his client (and repeatedly gets her death by electrocution), and Arlene Pralle, an eccentric born- again Christian who raises horses and wolves and who has become Aileen’s adoptive mother (don’t ask). A checkbook journalist with an overdrawn bank account, the intrepid Brit plays true to national type and trade by charmingly pleading poor-mouth to bargain down the asking price from the fast-buck-minded Yanks. Ironically, the most compelling sequence in his film comes free of charge: a guard in the Florida death house flitters around the wooden throne that is “Old Sparky” while outlining the etiquette for a sure-fire electrocution.

Practicing a kind of stalkarazzi cinema verite, Broomfield has carved a niche oeuvre out of the pursuit of transgressive females (Aileen Wuornos, Heidi Fleiss, Courtney Love), the camera granting permission for harassing conduct that would otherwise warrant a restraining order. It is a measure of the derangement of his once and present muse in the well-timed sequel, Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer, that where Fleiss acted wary and Love went ballistic, Wournos welcomes the spotlight. “Nick!,” she sighs in greeting, happy to see a friendly face, her enormous pupils dilated on whatever meds the Florida State Prison system has her whacked out on.

Aside from Broomfield’s clipped, laconic narration and Wuornos’s banshee wail, there is not much to say here, really. The second installment traces a melancholy death watch with an end reel as predictable as a Breen Office gangster film. After a decade on death row, Aileen has decided to give up the game: she’s found Jesus, or maybe just decided that a quick needle is preferable to rotting away in an orange jumpsuit (since 1999, Florida’s Death Row inmates have been given a choice between “Old Sparky” and “Old Sharpie.”) The film plays like an obit in progress. Broomfield highlights close-up encounters with his star attraction, reprises clips from the previous film, stitches together local news footage of the count-down to zero hour, conducts interviews with Aileen’s friends and mother (who abandoned her in infancy), and drives around the bleak environs of Troy, Michigan, where Aileen traded “blow jobs for cigarettes since the age of nine.” Physical abuse, sexual molestation, pregnancy at thirteen— it is a grim tale of neglect and violence towards a friendless child who was left out in the cold, literally, to live in the woods during a Michigan winter.

Bloomfield caps the chilling tour of Wuornos’s back pages with the last Death Row interview with Aileen, who was executed on October 9, 2002. Wuornos has her own agenda for the face-off, namely to expose the Florida detectives she claims knew of her murders but refrained from stopping her rampage until she racked up a body count sufficient to secure a lucrative motion picture deal. This is sheer insanity— I think. After her capture, some of the cops on the Wuornos case actually were dismissed from the force for trying to pitch the project to Hollywood.

In her last video testament, Wuornos screeches, rants, and spits invective into the camera/audience (“You sabotaged my ass, society!”) before calling cut to the action. Prior to the interview, a board of Florida psychiatrists appointed by Governor Jeb Bush has decreed Wuornos sane enough, legally speaking, to understand a lethal injection. “It was really pretty incredible that Aileen sailed through the psychiatric tests the day before,” Broomfield deadpans. “It makes you wonder what you’d have to do to fail.” Though Broomfield’s narration oozes a very European moral supremacy about the beastliness of American capital punishment and toys with the possibility that Aileen killed her first victim in self-defense, something that she affirms, recants, and then affirms again (“Mallory [the first of her seven victims] was self defense,” she whispers to Nick, “and so was some others...”), any redeeming social value takes second seat to the freak show aspect of the proceedings. The film might have been called Dead Woman Raving.

With the motiyes in the case so murky, and the perpetrator nutty as a fox squirrel, Patty Jenkins’s meditative dramatization promises some psychological insight or at least a narrative through-line. Monster is a title with at least three echoes: the 4-H Club Ferris wheel of Aileen’s childhood memory, a metaphor for an innocence not so much lost as never known; the woman herself, whose deeds have placed her beyond the human pale; and, America, who cradled the beast in her bosom. (“Monster” was the name of a preachy 1969 Steppenwolf tune, whose chorus went: “America/where are you now/don’t you care about your sons and daughters?” But perhaps I am free associating.) In the end, the multiple readings lead to but one conclusion: Aileen is not a monster; she is a misunderstood girl, abused at home and on the streets, a pathetic misfit seeking love in all the wrong places.

“I always wanted to be in the movies” and “be beautiful and rich like the women on TV,” a disembodied voice-over begins, cuing a montage of photo albums and flashbacks that settles on a tableau of Aileen, gun in hand, contemplating suicide, shivering under a rain-swept highway overpass somewhere in Daytona, Florida. As filtered through cinematographer Steve Bernstein’s jaundiced eye, the Sunshine State has never looked so blighted and dreary, the asphalt vista along 1-75 a fetid swampland of strip malls, biker bars, and cheap hotels with subtrailer-park interior decor. Nathaniel West famously wrote that people came to California to die, which is ridiculous. They come to California to dream. People really do come to Florida to die.

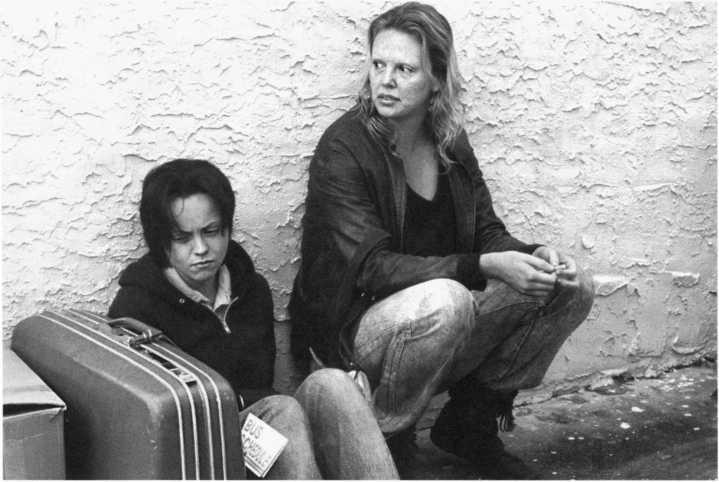

Shambling by chance into a gay bar, Aileen meets Selby (Christina Ricci), a quirky, cute as a button lesbian. “All I wanted was a beer,” claims Aileen, but we know better. The Mutt and Jeff pair bond while gulping whiskeys, and teenaged Selby takes Aileen home to bed, a sleepover her deep- fried Dixie family is understandably upset about. Soon, a moving camera is swirling about the lovebirds as they float around a roller skating rink to the overdetermined strains of Journey’s “Don’t Stop Believin’.” Against expectations, the lesbian angle is almost tangential, neither exploitative (the chick on chick tangos are discreet) or explanatory (no schematic feminist critique—though the men here, with the notable exception of Bruce Dern as a frazzled Vietnam vet biker who befriends Aileen, are lowlife scum).

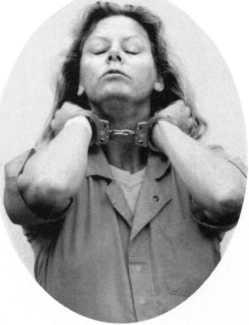

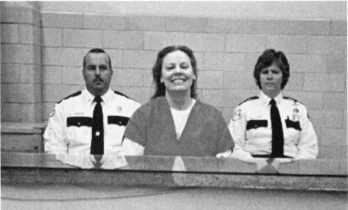

Aileen Wuornos (both photos above) as seen in jailhouse interviews in Nick Broomfield's two documentaries on the serial killer

The lovey-dovey stuff is a dead giveaway. In cable television terms, Monster plays like a Lifetime not Cinemax kind of serial-killer film. It is rooted in the genre of women’s melodrama not the kinky sex thriller, and body image, not body count, dominates the valence and visuals. With her blotchy complexion, bad teeth, and matted hair, Wuornos is a woman of frightful physical appearance and repellent demeanor, a veritable harpy, Medusa, she-wolf, and witch in a single package. If the handsome, intelligent Ted Bundy got all the breaks and squandered his potential with a conscious will to evil (“You’d have made a good lawyer and I’d have loved to have you practice in front of me,” said the judge who sentenced him to the electric chair, “but you went the wrong way, partner.”), Wuornos was dealt the worst card a sensitive female can hold. “Can I touch your face?,” pleads Selby that first night, with an unerring instinct for Aileen’s weakest spot. “You’re so pretty.” Later, primping in a gas station rest room for their first real date, Aileen sizes herself up in the mirror. “You look good, yeh,” she lies.

The sub textual (or sub-rosa) knowledge that beneath Wuornos’s skin is the beautiful actress Charlize Theron creates a curious spectatorial undercurrent—alternatively off- putting and absorbing. In an eerie CGI-like replication of the original, the regal swan transformed herself for Art into the ugly duckling. (Of course, the Academy obligingly chomped the obvious Oscar bait. Brecht- ian distancing + Stanislavski intensity = acting!) Clearly a close student of Broomfield’s earlier documentary, Theron nails Wuornos’s aggressive physical posture, her shoulders-back, chest-out, cock of the walk strut, her taut, contorted facial muscles poised to erupt in lunatic rage. Dressing up for a job interview wearing her notion of straight girls’ clothes, doomed to be humiliated by callous Human Resources bureaucrats, she is so ungainly that she seems a sister from another planet. Here Theron’s impersonation—bodily possession really— works to magnetic effect, for Aileen Wuornos is an alien inside her own body. After the end credits, one half expects the actress to appear, Scooby Doo-like, and rip off the mask to expose the babe beneath the prosthetics.

Not a bad girl at heart, Aileen commits her first killing during a backwoods tryst gone very wrong. After a sadistic john (and serial killer himself) beats, binds, and rapes her, she manages to wriggle out of her ropes and empty her gun into his torso. She emits an animal scream of pain before assuming his overalls, cap, car, and, ultimately, tastes. Yet she crosses the existential line only with the next killing, the cold-blooded murder of an obnoxious, but hardly dangerous, customer. If the first killing was necessity, the second is entrepreneurial: she needs money for Selby, her passive-aggressive coconspirator. “Why did you quit hooking?,” Selby whines, forcing lovesick Aileen—the breadwinner in the relationship—back out on the streets. (Presumably for legal reasons, the character of Selby is not so much a composite as a hallucination. Tyria Moore, Aileen’s real lover, was neither teenaged nor cute, and almost certainly less an innocent bystander during Aileen’s spree; she cut a deal with the cops and testified against Aileen in court.)

Slyly, director Jenkins renders the murders with little flash and less relish, ratcheting up the sympathy quotient for each doomed john, especially the last victim, an altruistic non-john (Scott Wilson) who genuinely wants to help, not exploit, the sad woman he picks up on the highway. Rather than wallow in on-screen splatter, Jenkins depicts existence on the lowest rung of the sex trade as the real monster movie: living out of a storage shed> cleaning up in public restrooms, and hooking on the interstate. Aileen plies her trade in cars, not even cheap motels. “Thirty dollars—straight up,” is her bargain-basement price, though at one point she touchingly tries to trade up by describing herself as a “call girl.”

When composite sketches of Selby and Aileen begin staring out from every video screen, the spatting but still smitten duo must split up to elude the long-comatose Florida police. After bidding a weepy farewell to Selby at the bus depot, however, Aileen spirals into a maudlin drunk at the real-life, perfectly named Last Resort Biker Bar, where, finally, she is busted. Soon the Aileen Wuornos familiar from Broomfield’s documentaries appears on screen, wearing the prison outfit that better suits her frame and temperament.

But fate has one last cruelty to visit upon the long suffering murderess. During a jailhouse phone call to Selby, she gradually realizes that the police are tapping the line. Jenkins intercuts between the two sobbing lovers, the one faithless, the other still true, allowing the scene to play out and letting Theron register the betrayal with her eyes. Nobly, she refuses to implicate her girlfriend and takes the fall alone. While Aileen is led away by the guards into a symbolic white light, the precredits voice-over returns to recite a string of banal, life-affirming cliches. “They gotta tell you something,” she snorts for the curtain line.

Yeah, they gotta tell you something— which is also the problem with serial killers on screen. After all, the species gainsays the stock psycho-sociological explanations for criminal deviance according to Hollywood: the Warner Bros, environmentalism of the 1930s (wherein gangsters were products of pool halls and tenements) and the Pop Freudianism of the 1950s (wherein delinquents juvenile or adult were damaged mental goods, usually dented by Mom). But though undreamt of in screenplays by Marx or Freud, the serial killer yields to a diagnostic model deeper in the American grain. “In Adam’s fall/sinn’d we all,” reads the first lesson in the Puritan alphabet book, imprinting the doctrine of original sin on young minds. Cast in the mold of John Milton’s satan and John Calvin’s sinner, the serial killer is just plain bad—unredeemably malicious, evil incarnate, beyond the ken of shrink or social worker. In life (Bundy is the exemplar) or in film (Hannibal Lecter is the icon), the serial killer prowls the two lane blacktops of the national psyche not because he is relentlessly murderous but because he is eminently sane—hence why Dr. Lecter is always more terrifying strapped to a gurney, smirking behind a hockey mask: he is restrained but not explained. Hence too why all those forensic noir detectives on television put their faith in the hard sciences. Best not to psychoanalyze the patient, just nail the fiend and put him down.

Aileen Wuornos was no Ted Bundy or Hannibal Lecter, and, billing and body count notwithstanding, not really a serial killer either. Warped by a lifetime of unimaginable abuse, she better fits the venerable role of the tormented madwoman— Lizzie Borden without the kinship network. Yet the sexual politics in her pop-cult celebrity is undeniable and cautionary. Serial killers often kill prostitutes—hey, who will miss them? When an anonymous hooker turns the tables and kills the man, she subverts more than genre expectations; she invites a vicarious thrill in the poetic payback wrought by an avenging female angel. Both Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer and Monster domesticate this woman and that meaning. Apparently, whether in documentary or docu-dramatic form, any female, even a multiple murderer, must, in the end, be the real victim.

References

Aileen Wuornos: The Selling of a Serial Killer (1992): Directed by Nick Broomfield, DVD, color, 88 mins.

Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer (2003): Directed by Nick Broomfield, DVD, color, 89 mins. Both documentaries are distributed by Lantern Lane Entertainment Ltd., P.O. Box 8187, Calabasas, CA 91372-8187, phone (818) 222-2309, www.lanternlane.com.

Monster (2003): Written and directed by Patty Jenkins, DVD, color, 109 mins., a Columbia TriStar Home Entertainment release (the DVD includes Aileen: Life and Death of a Serial Killer).