Thomas W. Durso

'Apotheosis Of A Stereotype'

Opinions Vary On Whether Unabomb Suspect Will Damage Science's Image

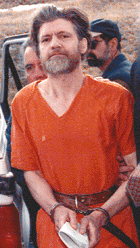

As the Federal Bureau of Investigation quietly builds its case against Unabomber suspect Theodore J. Kaczynski, observers ponder how the popular media's depiction of the Montana loner and former mathematician will affect the public's perception of science. Opinions range from beliefs that people will easily separate Kaczynski's credentials from his alleged crimes to fears that the case-played out in front-page headlines and sound bites-will reinforce stereotypes of "mad scientists."

"No sensible person is going to identify Mr. Kaczynski or the Unabomber with science or as a representative thereof," declares Paul R. Gross, the University Professor of Life Sciences and director of the Center for Advanced Studies at the University of Virginia. "On the other hand, the overwhelming majority of the public, I regret to say, is neither rational, nor reasonable, nor readers of detail."

Kaczynski, 54, was taken into custody in early April after his brother, David, discovered earlier writings of his that sounded suspiciously like the Unabomber's antitechnology manifesto. Published last September by the Washington Post, the 35,000-word manifesto denounced science as the downfall of humanity. "Science marches on blindly," wrote the Unabomber, "without regard to the real welfare of the human race or to any other standard, obedient only to the psychological needs of the scientists and of the government officials and corporation executives who provide the funds for research."

Kaczynski's capture, according to authorities, marks the end of an 18-year search for the Unabomber, whose explosive devices are said to have killed three people and injured 23 others (C. O'Kane, The Scientist, Aug. 23, 1993, page 1). Initial news reports about Kaczynski after his arrest were devoted to exploring his academic background, painting him as a mathematics prodigy. The description was not unfounded: He graduated early from high school and earned a bachelor's in math from Harvard University at age 20. A master's degree and doctorate from the University of Michigan quickly followed, and by the age of 25 he was on the tenure track as an assistant professor in the mathematics department at the University of California, Berkeley.

The manifesto's antitechnological theme makes clear that the Unabomber is a science hater, according to Gross. However, that may not matter to a public that relies more on quick-hit video clips to get facts. "Most people who get interested in this at the level at which people tend to be interested-in the six o'clock news on TV or '60 Minutes'-will hear, if it turns out that Kaczynski is the Unabomber, that this terrible person who killed people is a nut, a recluse," comments Gross. "They will hear that he has severe psychological problems, and that he is a brilliant mathematician. . . . Mathematics means science to most people, and so they might very well come to the conclusion of 'There's another example of a mad scientist,' period."

Science writer Anne Eisenberg, whose name and address were found by the FBI on a piece of paper in Kaczynski's cabin, is among those fearing he may end up as "the governing image of scientists in popular imagination."

"If convicted, Kaczynski will be perfect-he'll get top billing in the celluloid pantheon of scientists become monsters, replacing Vincent Price plotting murders in his laboratory or Dr. Strangelove wheeling through the War Room," Eisenberg writes in the June issue of Scientific American (A. Eisenberg, 274:25, 1996). "He will become the apotheosis of the stereotype, the archetype of the scientist run amok."

Nobel laureate Dudley Herschbach, a professor of chemistry at Harvard University and the chairman of the National Academy of Sciences' new Public Understanding of Science program, acknowledges the possibility that Eisenberg's prediction will come true. He attributes it to the media's need for "simple characterization."

"I think it's reasonable to guess that could happen, because there's such a propensity for such stereotyping," Herschbach notes. "I would hope that some of the media would portray this guy as a problem in psychology and pathology and not automatically assume that because he was educated as a mathematician, that somehow that accounts for his behavior.

"The vast majority educated as mathematicians show no such propensity," he points out. "It would be just as silly to say that everybody concerned about the environment is likely to start sending bombs to people. One has the impression that whatever in his background and makeup led him to write his manifesto and send his bombs didn't really have a whole lot to do with his education and mathematics."

As executive director of the American Mathematical Society (AMS), John Ewing has particular reason to worry about Kaczynski's background. However, he is quick to point out that while "the popular press refer to him as a mathematician," Kaczynski is merely "a person who many years ago did some mathematics."

Ewing adds that his society has taken pains to "make mathematics more accessible" to the American public. "In one fell swoop, here the Unabomber comes along and makes us all look like nuts," he says.

"I worry that people often don't really understand what it is that a mathematician does," Ewing observes. "I think that's kind of natural. Most people don't work on mathematical research. . . . When they see somebody who was at one time called a mathematician who then does something crazy, it makes them worry. That's bad for the image of the subject." He adds that AMS will continue its activities-publishing collections of articles to explain math developments to scientists, expanding its World Wide Web presence, initiating press contacts, and possibly launching public-service announcements-to "reach out" to people about math.

The fears are not unanimous. Gerald Holton, the Mallinckrodt Professor of Physics and Professor of History of Science at Harvard, says he is "not really worried about" how Kaczynski's training will be perceived by the general public.

"If he is the Unabomber, the image that comes through here is of a person who went off the edge," Holton contends. "He was well-educated in science up to a point, but he's seen as somebody who went nuts. He's more like the Freemen and other extreme groups, rather than being a black mark on education itself."

What does trouble Holton is a trend in journalism to be less interested in scientific advances and more in disputes. "The popular press has looked and will continue to look everywhere for controversial cases that can be played up as fraudulent science or mad science," he states. "It is part of the very regrettable tendency in the popular press to go away from discussions of matters of fact and of advances, for example, or detailed analysis of social needs, and instead focus on controversy."

Nobel Prize-winning physicist Leon M. Lederman has taken an active role in trying to improve the public image of scientists. Among his efforts is the attempted development of a network television series that would do for scientists what "ER" has done for physicians and "L.A. Law" did for lawyers (Notebook, The Scientist, Sept. 4, 1995, page 30). He predicts the Unabomber case will have "a very small effect," if any, on scientists. "When it comes to moral outrage, we have a great tolerance. Look at the executives of tobacco companies. The Unabomber is an ineffective pipsqueak compared to what they do," Lederman remarks. "I don't think it's going to have a negative effect. It might even go the other way. What he said is it's the scientists and engineers we [should] destroy," and, in reaction, the general public may feel more protective of science.

Keith Benson, a professor of medical history and ethics at the University of Washington and executive secretary of the History of Science Society, was interviewed by the FBI after the agency received a tip that the Unabomber had studied the history of science at the University of Utah. Benson disagrees with Gross's assessment that science equals math in many minds; for that reason, he claims, science's reputation is safe from any harm Kaczynski could cause.

"I don't think they're going to take anything away from science or scientists," Benson declares. "Most people think that mathematics is different than science. Science uses math, but mathematicians are some other type of individual. What's been emphasized in the press recently was not that he was arguing against the technical society, but that his background was in math."

"I wouldn't portray [Kaczynski] as a scientist," Herschbach cautions. "He's certainly not a scientist. His training was as a mathematician. The only professional work he did, apparently, was as a mathematician, and he was only a professor a short time."

Even so, argues Evelyn Simha, the head of the Massachusetts Institute of Technology's Dibner Institute, to equate that background with the Unabomber's crimes is wrong.

"The general press is giving math a bad reputation," contends Simha, whose organization seeks to advance the study of the history of science and technology.

Aside from Kaczynski's education, the overriding theme of many press accounts since his arrest has been the way he lived. Holed up in his cabin, hunting rabbits, and riding a battered bicycle into town, Kaczynski adhered to a lifestyle that perhaps was not very eccentric by Montana standards. Nonetheless, it is that lifestyle that will stick in the public's imagination, according to Langdon Winner, professor and graduate director of the Science and Technology Studies program at Rensselaer Polytechnic Institute in Troy, N.Y.

"I don't think they'll remember Kaczynski as a scientist. I think they'll remember him as a recluse, as somebody who ended up highly isolated from human contact and from human warmth and from everyday human concerns," he says. "I really don't think that people will remember Kaczynski, if he is found to be guilty, as anything like a typical scientist. What one might say is he tried mathematics, went far enough to get a Ph.D. and a first teaching job, and then something snapped. I think when he left his teaching position at Berkeley and became a troubled recluse, he stopped being a scientist. There's nothing scientific about his life for the last 25 years. I would be rather reluctant to draw any kind of conclusions about the public and scientists."

Regardless of their viewpoints, observers point out that their speculations are just that-calculated guesses whose accuracy will be difficult to quantify.

"Has [Kaczynski] had an effect on mathematics and mathematics teaching?" Simha asks rhetorically. "You really can't measure it statistically."

Virginia's Gross, who fears the media will overplay Kaczynski's education, adds: "If this were to happen on a broad scale, I suspect it would be very troublesome for science. The question is, will it? I don't know."

"It's just an aberration, that's all," says Herschbach, referring to Kaczynski's alleged behavior compared to those of mathematicians and scientists as a whole. "I hope that mad-scientist image is not the one that's trumpeted, but we'll have to see."

Then again, notes AMS's Ewing, perhaps the attention being paid to Kaczynski's schooling is not all that remarkable.

"It's natural that [when] people see someone who was once a mathematician who does something terrible, they're curious about it," he acknowledges. "Mathematicians and scientists in general ought to be thicker-skinned and be willing to roll with it a little bit, make light of it, have a sense of humor about things. Ever since Frankenstein, and probably long before that, people viewed scientists as a little strange. The truth is, academic communities tend to accept stranger behavior. . . . There's a little bit of truth there, that academic communities do have a broader acceptance. But I think that that's okay. You just have to accept the fact that people are going to view science as a little strange."

"Mathematicians have a reputation as people almost living in another world-justly," Herschbach points out. "They're fascinated by their subjects and feel that most people feel they're almost like computers."

According to Lederman, when the consequences of the Unabomber affair and Kaczynski's alleged involvement are examined, public reaction may be just the tip of the iceberg. He believes more time is needed to assess the impact on what he calls "influentials."

"Is the impact on decision-makers? Is the impact on journalists, writers, history teachers?" Lederman asks. "There are all sorts of different impacts with a much bigger waiting factor than the one on John Q. Sixpack."

Of course, famous murderers-mathematicians or not-are not a new phenomenon. Winner claims the Unabomber comes from "the same tradition" of serial killers as Jeffrey Dahmer-people recalled for their crimes, not their training.

"Who even remembers what they did before they started killing people?" Winner asks. "If anyone said there's a significant lesson here about what we ought to think about science, I would say there aren't any."

Despite the sensationalism swirling about the Unabomber, Holton believes it will all die down as the case recedes from front pages and nightly newscasts and is replaced by other horrors.

"The popular press is probably not going to think more about him up to the trial, and even then not much. I really think it's going to blow over fairly quickly," he maintains. "There is very little in this case except the fact that he's allegedly a murderer and probably loony. That's nothing so extraordinary in American life that one will keep talking about the case for a long time, alas."