Timothy Lloyd

What Folklorists Do

Professional Possibilities in Folklore Studies

Integrating Fieldwork and Library Research: Elissa R. Henken

Collaborating across Disciplines: Sheila Bock

Practicing Internationalism: Dorothy Noyes

Connecting Folklore Studies to Digital Humanities: John Laudun

Using Big Data in Folklore Scholarship: Timothy R. Tangherlini

Understanding the Information Technology World Ethnographically: Meghan McGrath

Doing Public Humanities: Danille Christensen

Serving a Campus as an International Scholar: Ziying You

Working as an Independent Scholar: Luisa Del Giudice

Teaching at a Community College: David J. Puglia

Teaching Undergraduate Students: David Todd Lawrence

Teaching Graduate Students: Ray Cashman

Teaching in an Interdisciplinary Department: Tom DuBois

Teaching Medical Professionals: Bonnie Blair O’Connor

Teaching Writing: Martha C. Sims

Integrating Vernacular and Mainstream Science in Teaching: Sandra Bartlett Atwood

Leading at a University: Patricia A. Turner

Chairing a Department: Debra Lattanzi Shutika

Directing an Academic Program: Michael Ann Williams

Managing an Academic Program: Cassie Rosita Patterson

Building an Online School: Sara Cleto and Brittany Warman

Performing Diplomacy: Valdimar Hafstein

Leading a Federal Government Agency: Bill Ivey

Directing a Federal Government Office: Elizabeth Peterson

Leading in a Consulting Firm: Malachi O’Connor

Directing Communications Strategy: Katy Clune

Directing a Learned Society: Jessica A. Turner

Directing a Museum: Jason Baird Jackson

Directing a Nonprofit Organization: Ellen McHale

Directing a Recording Label: Daniel Sheehy

Coordinating Research Projects: Diana Baird N’Diaye

Managing Regional Arts Programs: Teresa Hollingsworth

Managing a State Government Program: Steven Hatcher

Archiving for Preservation, Access, and Understanding: Terri M. Jordan

Building and Providing Access to Library Collections: Moira Marsh

Curating in a Changing Museum World: Carrie Hertz

Producing Audio Ethnography: Rachel Hopkin

Translating Language, Place, and Performance: Levi S. Gibbs

Critiquing Internet Culture: Andrea Kitta

Communicating and Educating Online: Jeana Jorgensen

Creating Educational Content: Jon Kay

Designing Visual Communications: Meredith A.E. McGriff

Presenting Ethnography Graphically: Andy Kolovos

Portraying and Preserving Culture through Documentation: Tom Rankin

Becoming a Journalist: Russell Frank

Editing a Scholarly Journal: Ann K. Ferrell

Publishing Scholarly Books: Amber Rose Cederström

Producing Festivals: Maribel Alvarez

Leading Cultural Tours: Joan L. Saverino

Performing Music and Theater: Kay Turner

Performing Stand-Up Comedy: Ian Brodie

Practicing the Act of Writing: Michael Dylan Foster

Using Folklore in Fiction and Poetry: Norma Elia Cantú

Writing Textbooks: Lynne S. McNeill

Writing for Education and Advocacy: Stephen Winick

Advocating for Community: Howard L. Sacks

Advocating for Communities and Their Environments: Mary Hufford

Using Ethnography for Community Advocacy: Miguel Gandert

Community Organizing: Jacqueline L. McGrath

Connecting University and Community: Katherine Borland

Exploring Home: Langston Collin Wilkins

Advocating for Labor: James P. Leary

Advocating for People with Disabilities: Amy Shuman

Advocating for Poetry: Steve Zeitlin

Advocating for a Region: Thomas A. McKean

Advocating through Consultancy: Susan Eleuterio

Creating Public Policy: Diane E. Goldstein

Analyzing Public Policy: Leah Lowthorp

Becoming a Politician: Jodi McDavid

Assisting Social Services Clients: Nelda Ault-Dyslin

Collaborating with K–12 Teachers: Ruth Olson

Partnering with K–12 Education: Lisa Rathje

Expanding Definitions of Regional Cultural Heritage: Nicole Musgrave

Preserving Historic Buildings and Environments: Laurie Kay Sommers

Front Matter

Title Page

WHAT FOLKLORISTS DO

Professional Possibilities

in Folklore Studies

Edited by

TIMOTHY LLOYD

INDIANA UNIVERSITY PRESS

Publisher Details

This book is a publication of

Indiana University Press

Office of Scholarly Publishing

Herman B Wells Library 350

1320 East 10th Street

Bloomington, Indiana 47405 USA

2021 by Indiana University Press

The paper used in this publication meets the minimum requirements of the American National Standard for Information Sciences—Permanence of Paper for Printed Library Materials, ANSI Z39.48-1992.

An earlier version of part of the Introduction was published in Timothy Lloyd’s essay about the American Folklore Society and the field of folklore studies in Learned Societies Beyond the Numbers, a 2016 publication he edited for the American Council of Learned Societies (http://www.acls.org/uploadedFiles/InfoBoxes/Learned_Societies/Learned_Societies_Beyond_web.pdf), and is included here with the permission of the Council.

Manufactured in the United States of America

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data

Names: Lloyd, Timothy Charles, editor.

Title: What folklorists do : professional possibilities in folklore studies / edited by Timothy Lloyd.

Description: Bloomington, Indiana : Indiana University Press, [2021]

Identifiers: LCCN 2021012952 (print) | LCCN 2021012953 (ebook) | ISBN 9780253058430 (hardback) | ISBN 9780253058423 (paperback) | ISBN 9780253058416 (ebook)

Subjects: LCSH: Folklore—Vocational guidance. | Folklore—Study and teaching. | Folklorists—Professional relationships.

Classification: LCC GR50 .W43 2021 (print) | LCC GR50 (ebook) | DDC 398.023—dc23

LC record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012952

LC ebook record available at https://lccn.loc.gov/2021012953

First printing 2021

Acknowledgments

I first want to thank those who helped create Time and Temperature, the ancestor of this book (see the introduction for details), in 1989: its editor, Charley Camp; its sixteen contributors; and the American Folklore Society’s Centennial Coordinating Council, led by Roger Abrahams and Marta Weigle, which commissioned Time and Temperature in the first place.

Second, I owe deep gratitude to my teachers Pat Mullen, Francis Lee Utley, John Rheinfrank, John Vlach, Dan Barnes, Bob Byington, Archie Green, Bess Lomax Hawes, D. K. Wilgus, and Joe Wilson, and to the members of the American Folklore Society, past and present, for their generosity in sharing their learning and insight.

Third, I thank my friends and colleagues Ray Cashman, Diane Goldstein, Bill Ivey, Jason Baird Jackson, and Michael Ann Williams (all contributors to this book) for their good counsel on parts of the manuscript and its organization. I’ll also cite contributors Ian Brodie and Dorry Noyes, and keen-eyed designer and editor Judy Sacks, each of whom gave me much-needed pieces of advice at just the right time.

Mostly, though, I am in debt to the seventy-seven contributors to this volume for their belief in and commitment to this project, for their willingness to undertake a different sort of thinking and writing assignment, and for sticking with their commitment through an especially difficult year for all of us and for the entire world.

Finally, my thanks go to my wife, Barbara, for her love, wisdom, and support.

Introduction

Timothy Lloyd

Why This Book?

It’s hard to go for long these days without being faced with yet another news article or op-ed about the perilous state of the humanities. Enrollments in humanities majors and classes, and job prospects for those with humanities BAs, are trending downward. Jokes and other narratives about humanities PhDs waiting tables or needing to learn how to write code to be seriously employed are never in short supply, but the situation of humanities PhDs who can only find piecemeal academic work without benefits or security is no joke. Within universities there has been much thinking and talking about what an undergraduate or graduate liberal arts degree is good for in the present world: committees and task forces have been created, conferences and symposia held, and reports issued, but the same thorny issues seem to persist.

At the same time, a new narrative has also begun appearing in reports and op-eds in which writers question the data—or the interpretations of the data—of humanities doomsayers. Those writers propose, on the contrary, that the abilities to think critically and pursue qualitative research, listen with openness and interpret with empathy, and deal with complexity and ambiguity—abilities that are at the core of humanities education—are exactly what are most needed in the world today and in the foreseeable future. In the last decade or so, the learned societies that represent fields in the humanities and the humanistic side of the social sciences have been focusing considerable attention on preparing graduate students and early-career professionals in their fields for what are called “alt-ac” positions, which draw upon the core competencies that education in a humanities field provides to offer alternatives to the diminished number of tenure-track faculty positions in the academy.

But I will let you in on a secret: there is a field that has been at this work, quietly but nevertheless successfully, for quite some time—folklore studies. This book, composed of seventy-six essays by folklorists writing personally and informally about their work, is intended to demonstrate many of the present-day outcomes of our field’s fifty-year history of engagement with these issues of purpose, usefulness, and public service: in other words, to show what folklorists do, to suggest what you can do in our field, and to evidence what other fields can learn from our experience.

None of this is to say that folklore studies has solved the problems of the diminishing number of tenure-track faculty positions or how to provide support for those who struggle in the academic or public workforces; far from it. These problems are a result of fundamental changes in the last half century across our economy, politics, and society and require comprehensive, sustained attention from many partners, including but not limited to the organizations that serve academic disciplines. People and institutions in our field have achieved some success at carving out new opportunities for productive folklore work and in advocating—as this book does—for the deep relevance of the perspectives of our field across society. But more remains to be done.

the Field of Folklore Studies

In the United States, the field of folklore studies straddles the humanities and the social sciences and is among the earliest organized of the seventy or so fields that exist in one or both of those universes. Members of three groups made common cause by simultaneously creating the American Folklore Society (AFS, the learned society and professional association for folklore studies) and establishing the American version of folklore studies in January 1888: scholars in then-developing humanities departments at colleges and universities, museum anthropologists, and private citizens with an interest in the subject and the financial means to pursue that interest.

The fifty years following the Civil War was not just the era when US folklore studies was born: it was the period when the modern American university, and the humanities and social science fields that live there, were created. We may think that the US university as we know it today—with multiple fields and departments; faculty who teach within those departments, conduct specialized research, and publish; and both undergraduate and graduate education in various departments and majors—has existed for many centuries. The fact is that this sort of university, based on German models, did not exist in the United States until the 1870s and 1880s, when it began to replace a world of undergraduate-only colleges, which instead of separate departments offered a single curriculum for all (in most US colleges at the time, “all” primarily meant well-off young White men), intended to create cultured citizens and leaders through the study of Latin and Greek grammar and literature, mathematics, ancient history, theology, and a few other subjects.[1] During this same fifty-year period, new fields in the humanities and social sciences—many of the ones we know today—started to take shape, become professionalized, and occupy newly created disciplinary territory, as evidenced by the birth years of some of the learned societies that represent these fields: the Modern Language Association (English and modern foreign languages), 1883; the American Historical Association, 1884; the American Economic Association, 1885; the American Folklore Society, 1888; the American Philosophical Association, 1900; the American Anthropological Association, 1902; the American Political Science Association, 1903; and the American Sociological Association, 1905.

During its history, our field has advanced several core ideas, among them that folklore—learned, practiced, and transmitted largely outside official settings and channels—constitutes a significant proportion of all cultural expression, not just a minor corner of it; that vernacular narratives, objects, beliefs, and performances offer especially productive routes toward understanding the identities and values people and communities create, and the extent and operations of human imagination; and that folklore shapes and is shaped by everyday life in our own (or any) time and place, not just in the past or somewhere else. Since its founding, the field of folklore studies has built an inclusive view of culture and creativity in communities by examining expressive life across boundaries of time and distance. Folklorists, using the core concepts of our field—including art, context, folk, genre, group, identity, performance, text, and tradition—work within the shared intellectual and social culture of what I have called a “listening discipline” to understand the intersections of artfulness and the social world, community-based creativity in a global economy, and both communication and conflict within and across religious, geographic, and ethnic divides.[2] Folklore studies describes the relations of lay and expert knowledge, advocates for mutual understanding and respect within the world’s diverse cultural commons, and has contributed unique intellectual insights to the creation, analysis, and evaluation of public policy.

In the United States, our field is organized somewhat differently than most of our sister disciplines in the humanities and social sciences. A number of universities support departments, centers, and programs in folklore studies that offer undergraduate majors and minors, graduate degrees, or both, whose faculty and students energize the field by creating their own approaches to scholarship, teaching, public service, and professional preparation. (For links to more information, please visit “Where to Study Folklore” on the AFS website, https://whatisfolklore.org/where-to-study-folklore/.) But most US universities do not have folklore departments; accordingly, the majority of folklorists in academic life work alone or in small teams across the full range of humanities, social science, and arts departments at hundreds of US universities, engaging in undergraduate and graduate teaching, research and publication, and service in our field and the fields of their departmental homes.

In the last fifty years, US folklorists—building upon a long history of strong public interest in our subject and extensive public engagement by our field since its founding—have also built homes for their work in arts and humanities agencies at all levels of government, in nonprofit organizations devoted entirely or in part to public education about folklore, and in private consulting practice. For the last twenty years, almost half of US folklorists—including an increasing number based at universities, where they train newer folklorists—have been working in this “public sector,” engaging with audiences of all ages and descriptions through public programs, including performances, museum exhibitions, media and other documentary works, and the development of curricula and teaching strategies for K–12 school programs.

A note: Although this book focuses on our field as it is practiced in the United States—just five of our authors work in other countries—folklore studies, since its nineteenth-century creation in Europe, is active around the world, as evidenced, for example, by the research and teaching of scholars abroad and by the robust activities (including conferences, collaborative projects, and communications in all media) of the national, regional, and international societies and associations that serve our international colleagues. (For links to more information, please visit the International Organizations page of the What Folklorists Do section of the AFS’s “What Is Folklore” webpage, https://whatisfolklore.org/what-folklorists-do/.)

Fieldwork

Folklore lives at the multiform intersections of artfulness and everyday life—or, as Henry Glassie put it, “the center [of the folklorist’s subject] is the merger of individual creativity and social order.”[3] Thus, to engage with folklore requires fieldwork: immersive research in the social world. Ethnographic fieldwork—presence in and engagement with a community and its people to observe, document, and come to understand their traditional cultural expressions as enacted in the course and context of everyday life—is the fundamental research activity of the field of folklore studies. If folklore is a listening discipline, most of the engaged listening and looking we do is done in the field: in the widest imaginable range of homes, workplaces, and gathering places, from our own familiar locations to those a dozen time zones and cultures away. Although library- and archive-based research are necessary complements to fieldwork—since to be properly situated, knowledge of the ethnographic present also requires deep historical and social understanding—even those folklorists who do most of their research in libraries and archives are in many instances working with scholarly publications based on, and documentary records created in the course of, fieldwork done by others.

There are many forms and kinds of fieldwork, including—to name just a few—basic collecting and documentation of traditional materials, long-term participant observation to address questions of change over time, quick surveys of the most visible traditions that characterize a community at a given moment, in-depth studies of particular individuals, and “salvage” fieldwork to document traditions rapidly evolving because of social, economic, or geographical change. Folklorists’ approaches to fieldwork, and the fieldwork activities they plan and carry out, often depend upon the desired outcomes of their project—film, exhibition, scholarly publication, public performance, cultural resource survey report, middle school social studies curriculum, or historic preservation plan. You will encounter stories of these and other sorts of fieldwork in this book, but underlying this diversity is the reality that fieldwork of some sort is central to what folklorists do. As Jim Leary, an author in this book, put it in his response to the essays in a 2020 special issue of the Journal of American Folklore: “If we really want to figure out what it all means . . . we need to do fieldwork with a lot of individuals and cultural groups over extended periods in particular places; listen deeply to what they have to say; share our findings with them; learn as much as we can about historical forces bearing upon their lives and traditional practices; and ponder meanings with comparativist circumspection.”[4]

This book begins with an essay about becoming a fieldworker, and throughout the book you will find evidence of the critical importance of fieldwork to folklorists. Regardless of the work they do, the great majority of our authors note the key importance of their ethnographic training—including their capacity for deep and engaged listening—to their professional lives.

Where This Book Comes From

As I noted previously, folklore studies as a field has been exploring professional alternatives for many years; accordingly, this book has its origins in another that was published more than thirty years ago. In 1987, Charley Camp, my longtime friend and folklore colleague who was then the Maryland state folklorist and had served as American Folklore Society executive secretary-treasurer from 1981 to 1986, was commissioned to edit one of the two volumes to be published by the society in celebration of its centennial in 1988 and 1989. (The AFS was founded on January 4, 1888, in Cambridge, Massachusetts, and held its first annual meeting in Philadelphia in 1889.) The first of these two volumes, a history of the field, was published in AFS’s first centennial year (100 Years of American Folklore Studies: A Conceptual History, edited by William M. Clements). The second volume Charley named Time and Temperature. Published in AFS’s second centennial year, it included lists of the society’s members in 1889 and 1989 and both visual and written essays on a variety of topics by contemporary folklorists, all illustrating the present and possible future states of our field and the organization that served it.[5]

Time and Temperature’s fourth section, though, is the one that concerns us here. Called “Faces,” it was composed of sixteen brief personal essays collectively describing some of the “ways in which folklorists apply and exercise their abilities” in a variety of professional roles common for folklorists to have occupied at the time. The essays’ titles all began “The Folklorist As . . .” and concluded with Academic Administrator (authored by Polly Stewart), Archivist (Jay Orr), Bibliographer (James R. Dow), Biographer (Edward D. Ives), Community Organizer (Lydia Fish), Cultural Critic (Archie Green), Curator (Marsha MacDowell), Dramatist (Robert McCarl), Editor (Judith McCulloh), Filmmaker (Tom Rankin, also an author in this book), Performer (Carol Silverman), Public Servant (Robert T. Teske), Publicist (Elaine Eff), Publisher (Marta Weigle), Record Producer (Neil Rosenberg), and Teacher (Ellen J. Stekert).

Collectively, these essays—informative, inspirational, and written by a “who’s who” of beginning to mid-career folklorists at the time—provide a valuable inventory of the state and repertoire of the field of folklore studies in the mid-1980s, and they remain valuable today on that score. Many folklore colleagues and I have found these essays to be of continual interest and use as a snapshot of the range of work folklorists do. However, since Time and Temperature was published, much has changed: the range of work folklorists do has greatly expanded in the past thirty years, and the ways even the original 1989 roles are now carried out have been altered, as the surrounding contexts of the academy and public-sector work—and our culture, technology, economy, and society in general—have been transformed, sometimes several times over. So for some time I have believed it would be worthwhile to create a new version of this part of Time and Temperature that would speak to the state and prospects of our field today.

What Folklorists Do is the tangible outcome of that belief—shared, happily, by more than six dozen of my colleagues in folklore studies whom you are about to meet. Like the original publication, this book focuses attention on the ways the perspectives of folklore studies inform the professional orientation and activities of those trained in it, regardless of what they do as folklorists and where they do it. Like its predecessor, it evidences the range of good work today’s folklorists actually do so folklorists-to-be (and the people who are in positions to hire folklorists) know the range of professional roles folklorists can and do fill, and how they do that work.

What Folklorists Do

The seventy-six essays in this book are not intended to illustrate all the non-folklore things you can “do” with a folklore degree; they are intended to illustrate many of the ways you can work in the world as a folklorist.

I have organized these essays into four categories—researching and teaching, leading and managing, communicating and curating, and advocating and partnering—but I encourage you not to take those categories too definitively. At some time in their careers, each of the contributors to this book could have been appropriately placed in any of these categories because each has done work in most or all of them, often at the same time—and more than occasionally they evidence this in their essays. All folklorists share a body of academic training, all create scholarship in some form and teach audiences in some educational context, all are called upon to provide leadership at some level, most of their professional activities are communicative and involve curatorial selection of what to talk about and how, and all have served as advocates and partners. Although a great many folklorists work in “alt-ac” occupations, many in the academy also carry out a range of activities extending far beyond teaching and research. And folklorists working outside the academy, like their sisters and brothers holding faculty positions, have a range of teaching responsibilities; they simply carry them out through different means for different audiences. Finally, please remember that each of the authors in this book represents many others doing similar work in our field.

That the range of folklorists’ work is this wide is in part a testimony to the creativity, the initiative, and (as one of this book’s essays notes) the scrappiness of those in our field, but it has other, more institutional sources as well. As I noted previously, the robust development of public-sector work in the 1970s brought folklore studies into a richer and more diverse version of today’s “alt-ac” business quite some time ago, and both educational curricula and professional development efforts in our field for many years have reflected this commitment to opening more doors to folklorists’ professional orientation and practice. The American Academy of Arts and Sciences’ report on its 2017 survey of humanities departments, to cite just one example, found that academic programs in folklore studies ranked highest among those in all humanities disciplines in offering presentations, workshops, and coursework on occupationally oriented subjects and that folklore studies also has the “highest rates of overall engagement with the digital humanities.”[6] The American Folklore Society has assisted in these efforts by managing a series of annual meeting preconferences and special sessions on many occupational issues and a year-round professional development funding program.

That’s how our field works. Our authors and I encourage you to read and engage with all the essays here; it’s our belief that each of them offers something for you to think with and learn from. Welcome to What Folklorists Do.

Bibliography

American Academy of Arts and Sciences. The State of the Humanities in Four-Year Colleges and Universities (2017). Humanities Indicators Project, n.d. https://www.amacad.org/sites/default/files/media/document/2020-05/hds3_the_state_of_the_humanities_in_colleges_and_universities.pdf.

Camp, Charles, ed. Time and Temperature. Washington, DC: American Folklore Society, 1989. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/handle/2022/9008.

Clements, William, ed. 100 Years of American Folklore Studies: A Conceptual History. Washington, DC: American Folklore Society, 1988. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/dspace/handle/2022/9008.

Feintuch, Burt, ed. Eight Words for the Study of Expressive Culture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2003.

Glassie, Henry. Turkish Traditional Art Today. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1993.

Ivey, Bill. “Values and Value in Folklore (2007 American Folklore Society Presidential Address).” Journal of American Folklore 124, no. 491 (Winter 2011): 6–18. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.124.491.0006.

Leary, James P. “Old Thoughts on (A)New Critical Folklore Studies: A Partisan’s Response to the Special Issue.” Journal of American Folklore 133, no. 530 (Fall 2020): 471–488. https://doi.org/10.5406/jamerfolk.133.530.0471.

Veysey, Lawrence R. The Emergence of the American University. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1965.

———. “The Plural Organized Worlds of the Humanities.” In The Organization of Knowledge in Modern America, 1860–1920, edited by Alexandra Oleson and John Voss, 51–106. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1979.

WHAT FOLKLORISTS DO

1. Researching and Teaching

Doing Fieldwork: Tom Mould

Tom Mould earned his PhD in folklore at Indiana University and is Professor of Folklore and Anthropology at Butler University.

Humans have been fieldworkers since the beginning of time. We watched, we learned. We joined in, we learned. Eventually, we began to ask questions to learn even more. Fieldwork is embedded in our species’ DNA. For the vast majority of the population, the process stops there—life recorded in memory and embodied in practice at the boundaries of our own cultures. The work is often invisible even to ourselves. Only when we engage in this work consciously and record it to share with others do we call it Fieldwork with a symbolic capital F. Observing, participating, and interviewing—these are the cornerstones of ethnographic fieldwork that are foundational to the study of folklore.

I remember my own transformation from fieldworker to Fieldworker as a rite of passage.

First, separation: Christmas Day, 1995. With a belly full of ham, mashed potatoes, and lupini beans, I borrow a car from my parents and set out—as a folklore grad student and novice fieldworker—for the tribal lands of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. I am a White, southern, male, single, cisgender, Italian American, second-generation college student. All these identities will play roles—some positive, some negative—in how I enter the Choctaw community. Then, transition: I struggle over the next six years, making missteps and breakthroughs in roughly equal measure. In no particular order, I come to learn about individual tribal members, ethnographic fieldwork, Choctaw culture, folklore, narrative, and myself. Finally, reintegration: I return a folklorist and a Fieldworker. Black robes and a blisteringly hot and humid graduation day formally proclaim my new identity. But the real confirmation happens before I leave Mississippi, at a farewell backyard barbecue where my relationships with tribal members are cemented. I am given a handmade Choctaw stickball shirt. Eventually I realize the most important integration achieved through the rite of passage of fieldwork is not into academia but into the community where I have worked.

Separation, transition, reintegration. Repeat. Simple and not so simple. The transition period of doing fieldwork is dynamic, exciting, exhausting, and, above all else, unique: what works in one community may not work in another. Among the Choctaw, where the interests of White men have rarely resulted in favorable outcomes for the tribe, I was most often met with suspicion. I worked hard to convince people I had no ulterior motives and that any money made from the books I wrote would go back to the tribe. Among members of the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-day Saints, on the other hand, I was greeted most often with open arms, with members often assuming I did have an ulterior motive: that of joining the Church. In both, there were exceptions. There were individuals among the Choctaw who befriended me far sooner than I should have expected, and among the Latter-day Saints were those who worried I might be one more academic from outside the Church whose goal was to expose rather than shed light. Honesty, sincerity, and transparency underlay my approach in both communities but emerged in response to very different expectations each group had about outside researchers.

The politics of identity, complex and unique histories, dynamic performance contexts, and the vast diversity of individuals ensure fieldwork can never be as objective, systematic, and uniform as books on methodology tempt us to believe. Social, cultural, and political norms change; so too must fieldwork. In the twenty-five years between my first visit to the Mississippi Choctaw and my most recent, the landscape has changed dramatically. Tired of research guided by exoteric interests, false assumptions, stereotypes, and misguided charity, indigenous groups the world over have been instituting formal procedures for determining what research can be conducted within their communities. And so it was with some trepidation that I found myself standing at a podium in the tribal council hall in early 2020, answering questions from the newly elected chief and the seventeen-member council of the Mississippi Band of Choctaw Indians. Thoughtful and insightful, the council members seemed interested, even encouraging. And then: “Why isn’t a Choctaw person doing this work?” The question was pointed but not unexpected. After all, the pros and cons of insider versus outsider research have been debated for years. I offered an answer that clearly did not satisfy the councilwoman, who directed her follow-up question to Jay Wesley, the head of the Chahta Immi Cultural Center.

Jay was there as a coresearcher, one of seven leaders in the community with whom I had spent the last year developing a research project. Within the proliferation of models for collaboration that attempt to recenter power and agency within the local community, I have most often used a community-based research model that attempts to play to the strengths of each member. I used this model a few years earlier with research on narratives about public assistance undertaken with a group of ten community partners in North Carolina spread across a range of social service agencies. The model served us well that day. Jay answered questions with an understanding of local politics I could not hope to navigate so well or so quickly. The council voted to approve our work.

In recent years, community-based research has become common in the social sciences and humanities, particularly with indigenous communities. If this sounds bureaucratic and impersonal, it is and it isn’t. The tribal process of formal approval surely is formal, with its committees, resolutions, precouncil meetings, and official voting, and it would be easy for the work to suffer a similar fate. But the friendship model of fieldwork I learned from Henry Glassie provides a blueprint for nurturing rapport and fostering relationships built on trust that can run parallel to formal procedures.

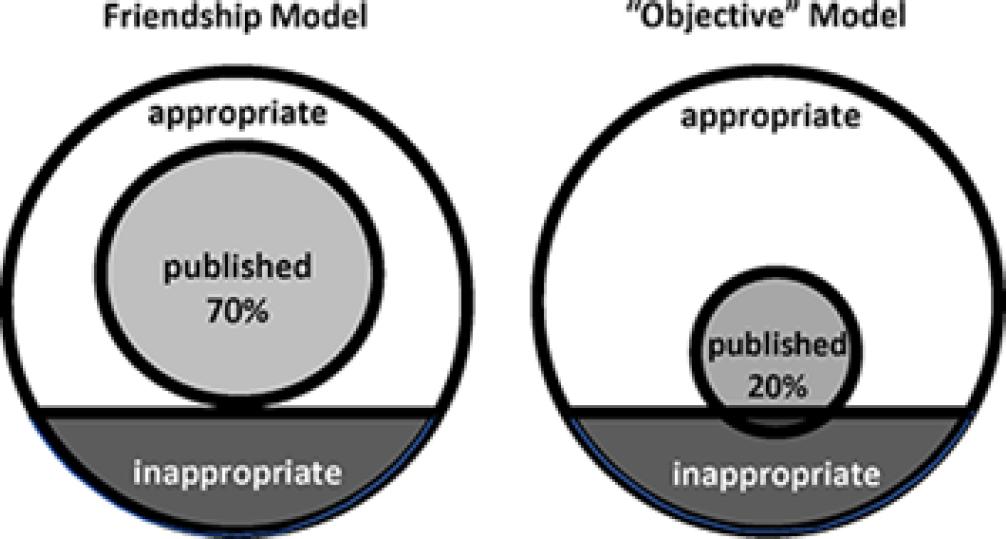

This model is not without its critics, who believe such an approach imposes interpersonal obligations that lead to flattery rather than honesty. Henry’s response, offered in a footnote in his book The Stars of Ballymenone, provides a defense of the friendship model, suggesting that fieldwork done without rapport and trust may yield an understanding of 20 percent of a tradition while friendship can lead to 80 percent. Because our work is fundamentally humanistic, our shared respect of people’s privacy and dignity leads us to avoid reporting on perhaps 10 percent of that knowledge, which still leaves 70 percent to be made public (see fig. 1.1).

To be sure, these numbers are imagined and impossible to prove, but many of us have had experiences like the one I had talking with a Latter-day Saint family. One hot June evening in 2006, I was enveloped in an overstuffed sofa in Tim and Meredith Sampers’s apartment, where they lived with their two children. (These names are pseudonyms; the reason will become clear in a moment.) I had gotten to know the whole family through my weekly Church attendance, Sunday school classes, and Priesthood meetings. An hour into our conversation, Tim paused and asked me to turn off the audio recorder. He and Meredith wanted to share two stories with me. “These are for you, not for the book,” he said. They were deeply personal, spiritual stories he wanted me to understand even though he didn’t want them shared more widely. Knowing these stories helped ensure that what I wrote was accurate, even if those particular stories could not be part of the written record. Tim understood what critics of the friendship model of fieldwork do not: that accurate and nuanced research in the humanities and social sciences is good because of our bonds of trust and respect, not despite them.

In the end, the binaries we construct to define our work fall apart. The clinical objectivity of the fieldworker who avoids friendship is as artificial as the accusations of utter subjectivity made about the work of the fieldworker who embraces it. Fieldwork versus archival research, qualitative versus quantitative research, insider versus outsider, lone researcher versus collaborative team, natural versus artificial performance contexts, face-to-face versus online: for many of us, these binaries either erode into a continuum or orient us toward both/and solutions rather than either/or ones. I have found synthesis and integration far more productive than working in absolutes. Coupling my ethnographic fieldwork with collaborative data collection, archival research, and online data has allowed me to ask quantitative as well as qualitative questions, exponentially expanding my interpretive lens.

The variations are as numerous as the research projects we develop, but at the heart of it all are the people we are privileged to learn from. The names of these people are also too numerous to mention, although early in my drafting, I imagined this essay filled solely with their names. Unable to list them all, I list none, save one: Gladys Willis. Her photo has been on my desk for twenty-five years. Many have followed, but Grandma Willis was the first to show me the power of fieldwork to introduce us to people, wise in ways we cannot imagine, who effortlessly reveal the astounding depths of our shared humanity.

Integrating Fieldwork and Library Research: Elissa R. Henken

Elissa R. Henken earned her PhD in folklore at Indiana University and is Professor Emerita at the University of Georgia.

Many things fascinate and delight me about studying folklore: its patterns and their variations, the way folklore both reflects and shapes people’s attitudes and behavior, the way it continually changes in accordance with the sociocultural context, and the fact that one can study it with any group, in any place, at any time. I’m continually in the field, taking notice and collecting—whether in a library, classroom, or community—combining research spheres of folklore studies. Sometimes I go in search of a specific topic; sometimes a topic just leaps out at me, which sounds haphazard but is very exciting.

My first major project was on folklore of the Welsh saints: men and women who were hermits and ecclesiastics in the fifth through seventh centuries. Narratives about them eventually appeared in a variety of sources, mostly in Welsh or Latin, beginning in the eleventh century. My study entailed culling all these sources, scanning them by eye, page by page, in those days before digitized texts and electronic searches—indeed, probably the most useful aspect of my work was providing a resource guide to the narrative traditions of these saints—and then trying to examine them as folklore. Researching folklore in written texts is always complicated by uncertainties about the original context and sources of the materials; these complexities only increase when dealing with medieval texts. Descriptions of saints’ lives, for example, were political—created in a clash of Celtic and Anglo-Norman churches and cultures—and copied other texts, shared motifs, and recorded local lore. Very often, working with medieval materials becomes a balancing act between figuring out what’s going on and not imposing one’s own sense of a satisfying narrative or seeing patterns where none exist. Nonetheless, one of my proudest moments was when I recognized a biblical and Norwegian folktale motif and was able to emend one letter in an otherwise unintelligible line of poetry to reveal a saint’s staff blossoming in divine proof.

Beyond the pleasure of gathering materials and contemplating sources and lines of transmission was the satisfaction of recognizing broader patterns: the male saints, who were local heroes, followed the same biographical pattern as secular heroes, starting with wondrous births, precocious childhoods, and marvelous feats, while the pattern for the female saints did not begin until they were confronted with male sexuality. Male sanctity was predetermined at conception, while female sanctity was accomplished only when the woman “won” her virginity or became the mother of a saint. Although lore about the saints is still shared in many places, this project remained mainly library focused due to problems with travel, language skills, and shyness.

My next major project, however, was more evenly divided between library research and fieldwork. Owain Glyndŵr, who led the last major armed rebellion of the Welsh against the English (1400–1415), was seen in his own time as a redeemer hero, the hero who is prophesied to come—or, never having died, to return—to restore the nation to its former glory. The Welsh, who suffered under the Romans, Anglo-Saxons, and Normans, were in need of a redeemer hero, and Glyndŵr, known as y mab darogan (the son of prophecy), was seventh in a line of eight major redeemers (King Arthur is fourth in that line). Again I spent innumerable hours in the library, thumbing my way through manuscripts and printed editions of poetry, histories, antiquarian reports, nationalist journals, and political writings as I traced the pattern leading up to Glyndŵr, saw how he used the traditions to present himself as the prophesied redeemer, and examined how, after his disappearance, he became the subject of legend and eventually a symbol of modern Welsh nationalism.

But I also spoke with people from all over Wales about Glyndŵr. Again, shyness was a problem—fieldwork for me is like wading into cold water: agony to make that first move but glorious once you’re in—but an even greater problem was that Glyndŵr, a nationalist symbol, remains politically fraught. One woman, who had been willing to talk with me and wasn’t even put off by my tape recorder, ran from me in the street when I mentioned Glyndŵr, and another woman kept repeating that she couldn’t talk to me and that her boss was English. And these occurred in Machynlleth, where Glyndŵr had set up his parliament, and they could have simply (and safely) pointed out the building. These less-than-successful encounters were instructive in themselves, but it was more exciting to hear people tell stories connected to local sites—the place from which Glyndŵr threw his sword, which left its imprint in a stone that is now part of the church; the field in which he dressed wooden poles as soldiers and tricked the enemy into not attacking; the cave where he sleeps while waiting for the right moment to return—all perfect demonstrations of the link between place and lore. While the overall study covered many centuries, fieldwork also permitted comparative study in a single time period, revealing how different people used the same legend. Take, for example, one legend (dating at least to the sixteenth century) in which Glyndŵr, having emerged from his cave, meets an abbot and remarks on him being up early. The abbot replies, “No, it is you who is up early, a hundred years too early.” And by that, Glyndŵr knows it is not time, and he goes back to his cave. With wistfulness for unaccomplished dreams, one older man, who had been describing Glyndŵr as a man of vision, told me this story and then explained that Glyndŵr was a man before his time. A younger man, a member of a group that teaches Welsh people more about their history so they can better appreciate their right to independence, ended his rendition of the story with the abbot by saying that Glyndŵr had come sooner than he should have; he suggested that the Welsh hadn’t been ready to fight but might have been had Glyndŵr waited two centuries, in which case Wales would be a free nation today.

Glyndŵr was noted for his destructiveness, but even when he burned whole towns, he left the homes of his supporters standing. During my first semester at the University of Georgia, my students, sharing their own local legends, told me how Civil War Union general William Sherman razed everything in his path but left their town—and only their town—unharmed. This was said of at least a dozen towns for reasons such as a former classmate or an old girlfriend living there, the women of the town making him and his men a fried chicken dinner, or the town being simply too beautiful to destroy. These and other stories showed the ravaging monster—that devil Sherman—tamed by southern civility to civilized, gentlemanly behavior. I continued to collect these and other stories from my students but also in the field.

I felt very strange as a New York Jew wandering around Georgia saying, “Tell me about Sherman.” One of my most difficult times was attending the annual conference of Georgian Sons of the Confederacy. I was fortunate that after an awkward start, a couple decided I was all right and took me under their wing, calling people over to talk with me. However, I found it confusing to work with people with whom I disagreed on almost everything politically and socially (the opposite of my experience in Wales) and at the same time to find myself tearing up alongside them as they told their family stories of wartime hardship. I wondered whether my own convictions were so malleable, but then I thought about shared humanity and the reality of suffering no matter the cause. When one man challenged me that I would misrepresent them, I could only promise that I would present his views as accurately as possible and that my job was to let each person’s voice be heard. Although it is sometimes painfully difficult, I still believe that. I have found myself constantly shifting between library research (Welsh legends of hidden treasure; Arthurian folklore) and fieldwork, often inspired by my students (legends about famous people sacrificing to join or leave the Illuminati; legends told by gamers versus nongamers about the dangers of video games; legends and beliefs about human sexuality) and sometimes requiring archival or online research, but the excitement of discovery is always the same. Very different discoveries—finding a previously undiscussed narrative genre (origin stories for proverbs) in medieval Welsh and Irish texts and recognizing in contemporary lore a pattern by which women of a distant enemy appear in jokes as dirty and ugly, while the women of a nearby enemy appear in legends as especially beautiful, luring men to death or disease—each left me high on excitement. No matter where a project starts—in the library, in the classroom, or from a casual bit of conversation, often with my tripping over one thing while looking for another—it generally requires research through the other spheres, and in each place I have observed and learned more I can share.

Collaborating across Disciplines: Sheila Bock

Sheila Bock earned her PhD in English and folklore at The Ohio State University and is Associate Professor in the Department of Interdisciplinary, Gender, and Ethnic Studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas.

During a campus visit to interview for a faculty position in interdisciplinary studies at the University of Nevada, Las Vegas (UNLV) soon after I defended my dissertation, the search committee asked me how my academic training and professional experience made me a strong applicant for that position. In all honesty, I don’t recall exactly what I said in response, but I remember I did not have a difficult time answering the question.

Throughout my graduate training in the field of folklore studies at The Ohio State University (OSU), I was incredibly lucky to have advisers and faculty mentors who so adeptly navigated the interdisciplinary landscape of that institution while also modeling engagement in research that straddled the boundaries of folklore and other disciplines, including political science, disability studies, Middle Eastern studies, and dance, among others. As is the case at many graduate programs in our field, at OSU students receive training in folklore studies while occupying different disciplinary homes within the institution: in my case, the Department of Comparative Studies for my MA and the Department of English for my PhD. As we came in contact with people from varying disciplinary backgrounds in our courses and attended different professional conferences to network and present our research, my fellow folklore graduate students and I had many opportunities to practice articulating for different audiences what folklorists study, how they do it, and how folklore as a discipline both overlaps with and differs from closely related fields that also lay claim to the study of informal knowledge, creative communication, and the complex dynamics of culture.

I am grateful for having acquired this ability from my graduate school experiences to cross disciplinary borders that were not heavily policed, to use a geopolitical metaphor. The interdisciplinary nature of my folklore training has not only enriched my scholarly work but has helped me envision and articulate the relevance of my work to different audiences and has also very directly informed my teaching in the Department of Interdisciplinary, Gender, and Ethnic Studies at UNLV, particularly in classes that guide undergraduate students through the process of conceptualizing and carrying out research-based projects that explicitly integrate at least two different disciplinary perspectives. In addition, it has helped me develop the confidence to converse with people in different disciplines about the value of folklore studies and its approaches, which became particularly beneficial when I found myself as the only folklorist on campus when I started my first year as a faculty member in 2011.

I still feel lucky to be in this departmental home, which appreciates my disciplinary grounding in folklore studies and encourages interdisciplinary connections. On multiple occasions during my time at UNLV, informal conversations across disciplinary boundaries (after lectures on campus, during faculty “meet and greets,” or at social events at colleagues’ houses) have developed into cross-disciplinary collaborations.

When I teach my students about doing research that crosses disciplinary boundaries, I distinguish between multidisciplinary and interdisciplinary research, and my collaborations have fallen at different positions on this spectrum. At one end of the spectrum, multidisciplinary research brings together the perspectives of two or more disciplines with the goal of gaining a more comprehensive perspective on a given research topic. In multidisciplinary research, the contribution of each disciplinary perspective is clearly defined from the beginning. For example, when I worked with colleagues in health-care administration and nursing to study patient perspectives on the Patient Centered Medical Home Care delivery model, especially among patients with type 2 diabetes, I was the only one on the research team with experience using in-depth open-ended interviews as a method. Within this project, my collaborators deferred to my expertise with qualitative methods as well as my disciplinary training in attending to people’s perspectives and experiences. Although we worked together to create the research design and analyze the interview data we collected—so the process was not just assembling the pieces of a premade jigsaw puzzle—each participant’s domain of expertise was clearly demarcated throughout the collaboration.

At the other end of the spectrum, interdisciplinary research also involves bringing different disciplinary perspectives together to more completely understand a given topic, but it also leaves open space for dialogue across the boundaries of the disciplines, creating opportunities for articulating new relationships between different domains of expertise and for thinking critically about the assumptions embedded within them. For example, I collaborated with a historian colleague to tell the story of an unpublished tale collection her father documented in the Sonora region of Mexico in the 1970s. While the demarcation of disciplinary expertise at first glance appeared pretty clearly defined, our project ultimately developed into an examination of the generative and at times uneasy interactions that emerged at the borderlands of our disciplinary affiliations within the academy. These dialogues at the borders of our disciplines led to a critical rethinking of the “archive” of materials we were working with and the hierarchies of interpretation that were grounding our analyses, both individually and collaboratively.

If we carry the borderlands metaphor farther, it is perhaps not surprising that my training as a folklorist has heavily informed the cross-disciplinary collaborations I’ve participated in at various points on the multidisciplinary-interdisciplinary spectrum I previously described. The foundational elements of folklore studies include a sincere desire to understand the perspectives of others and a willingness to think critically and reflexively about how our own background, perspectives, and biases inform the work we do. Folklorists, especially although certainly not exclusively those doing ethnographic work with communities in the present, recognize that the best and most fulfilling work grows out of sustained relationships with people and the respect, trust, vulnerability, reciprocity, and friendship those relationships can engender (although, of course, the intimacy of friendship can create its own challenges in scholarly enterprises). Finally, my folkloristic training, particularly in ethnographic methods, has helped me see value in the experiences of “failure” in those moments of uneasiness, and here I use the term failure not as the opposite of success but rather as the destabilization of our initial expectations through our encounters with the people with whom we work. In cross-disciplinary collaborations, such destabilizations can be incredibly generative, although, as with doing fieldwork, they require us to reflect on the messiness that emerges through a sincere commitment to dialogue. This is not always possible—given the institutional expectations and constraints of the university, among other factors—but I have found it to be an ideal worth working toward that reaffirms what I love most about the field of folklore studies.

Practicing Internationalism: Dorothy Noyes

Dorothy Noyes earned her PhD in folklore and folklife at the University of Pennsylvania and is Professor in the Departments of English and Comparative Studies at The Ohio State University and a past president of the American Folklore Society.

My father, a corporate executive in an aging rustbelt industry, once explained to me that management consultants command such outrageous fees because they are free to say what cannot be said by employees: they are simply ventriloquists who provide a safe channel for internal critique. I wasn’t convinced. Were all those Harvard Business Review buzzwords pure camouflage, then? Were the consultants actually listening to people like him or just peddling their formulas? Wasn’t his company bamboozled by the magical name of the prominent firm that promised to sweep in and set them right?

As an American folklorist working frequently in international settings, I have found myself playing both the ventriloquist and the mystifier. My nationality and, in due course, my professional position have called me to play both parts. But being a folklorist makes a difference. Practicing what Tim Lloyd has called a “listening discipline,” folklorists inevitably end up being transformed by what they hear. Associated with the study of practices deemed marginal, backward, minoritarian, or trivial, folklorists are forced into egalitarian, even deferential relations with others who can offer a useful counterweight to our national and professional identities. Both our working methods and our substantive focus on the local and vernacular can help us practice an internationalism less fraught than the kind tied to power politics and national interests.

When I first went to the struggling industrial town of Berga in the foothills of the Catalan Pyrenees for my dissertation fieldwork, I was at once sized up for any value I could offer. Americans were infrequent visitors, meriting attention, but a timid graduate student hardly fit local preconceptions; at one point I heard, “That’s not an American! It’s too short!” Still, as the only American handy, I was available to hear critiques of US foreign policy and answer questions about Michael Jordan and English grammar. As a future academic who planned to write a book, I was found somewhat worthy of cultivation by local elites seeking international amplification for Berguedan tourist attractions and Catalan nationalist claims. Most important, as someone talking across social boundaries within the town—partly by intention, partly out of ignorance—I became a conduit for indirect local communication. In short, I was recruited to play the ventriloquist at more than one level. Idiosyncratic social theories, personal grudges, political analyses, transgressive jokes, and inadmissible longings were all expressed to me insofar as it was my job to pay attention to anyone who approached me. The opportunity was of special interest to marginal individuals of every kind. Having had ample leisure to contemplate the grounds of their marginalization, they were always worth hearing, even though they were hardly objective observers. Over time, as I kept showing up, more central actors began to talk to me freely, blowing off steam about local irritants or formulating ideas they had no reason to articulate to their neighbors. In festive settings, my presence often prompted heightened performance and the acting out of small social scenarios, with a glance or a call to ensure I was attending and sometimes an explicit command: “Put this in your book!”

In the short term, as I published small pieces in the local press, my ventriloquism lent some legitimacy to the minority report of the festival I had come to study: a less reverential, more present-based, more experiential, and more contested account than the one articulated in the established channels but that still endorsed, even flattered, local convictions of the festival’s importance. As an ethnographer I was, of course, pulling together fragmented communications and making tacit understandings more explicit, and in the matter of the dancing mule’s orgasm, this provided much public glee. Occasionally I was able to offer an affirming mirror in which some actors could recognize their best individual and collective selves. I believe a few of them found this useful in imagining their next steps forward.

Still, the power of the ventriloquist is ephemeral; it does not always work for good, it does not work for everybody, and even the most illuminating ethnographic dialogue counts for nothing in relation to sustained economic forces, political struggles, and institutional frameworks. Conversely, I lost my perceived innocence and became aligned with certain views only; I went back to the United States and did other things. After thirty years the dialogue is only intermittent, now and then sparking interest or proving useful to someone there.

The greater impact was, of course, felt on my side. The folklorist’s modus operandi of learning to participate in shared social forms and taking insider views seriously poses inevitable challenges to the self. Many of my habits were altered; others were made visible. My assumptions were challenged, tacitly and explicitly. Some I revised or abandoned; others I came to acknowledge and value more carefully. Most important, as a late baby boomer White suburban American interacting intensely for the first time with people formed in a hardscrabble town under an authoritarian regime, I was forced into a radically different understanding of personal agency and freedom. Indeed, I learned to recognize my freedom as a constraint of its own: in the words of a Finnish immigrant proverb, once you’ve crossed the Atlantic, you’re always on the wrong side.

I was hired into a folklore job in an English department and did not remain a Catalan specialist. Instead, because my students came from around the world and because the network of folklore scholars is relatively small but global, I learned to think my way into a range of international situations, and I traveled a lot. Along with other folklore scholars at Ohio State, I was recruited into the interdisciplinary conversations of the university’s Mershon Center for International Security Studies because we were perceived as offering expertise into foreign cultures or, more subtly, the ability to ventriloquize other voices that would not otherwise enter into policy debates. What we really offered was the ability to knock the United States off its pedestal and enter into international conversations on a more equal footing. Because we were full of self-doubt, because we were accustomed to synthesizing other positions and imagining rationales for them, because as a discipline we were associated with localized low-status endeavors that pointed to inequities and imperfections in the achievement of the modern—because, in short, we did not intimidate anybody—we were able to go where respectable social science could not. Accustomed to making the most of accidental juxtapositions rather than having the resources to design our activities from the top down, we organized conversations among people who would not have thought to talk to one another. For example, take the 2010 “Making Sense in Afghanistan: Interaction and Uncertainty” conference my OSU folklore colleague Margaret Mills and I organized, in which high-ranking US military officers and low-level recruits, Afghan intellectuals, anthropologists critical of the US counterinsurgency strategy, folklorists listening to the gossip in the bazaars, NGO workers, and political scientists all managed to speak frankly to one another about the impact of confusion on all sides of a highly asymmetrical international conflict.

Now a professor of a certain age, I am frequently invited to speak to students and scholars in other countries, which is facilitated by the still potent mystique of US academia even as the nation’s prestige is in free fall and its state capacity has come into serious question. Sometimes I hear my words quoted and feel as bogus as the management consultants who used to plague my father. More often, however, PhD students, academics, policy makers, and cultural professionals receive me with friendliness, hear me politely, and then feel free to argue. They know my knowledge of their circumstances is incomplete, even when I fail to acknowledge it. They know my analytical frameworks are formed out of particular experiences, just as theirs are. Formed outside the insulation of a superpower, they are accomplished practical comparativists in multiple directions, well aware that I need their mirroring insights more than they need mine. As a certain kind of American, I am still learning to listen. But as a folklorist, I’ve got a lot of opportunities to do so.

Connecting Folklore Studies to Digital Humanities: John Laudun

John Laudun earned his PhD in folklore at Indiana University and is Professor in the Department of English at the University of Louisiana.

As a researcher and teacher, what drives me is making connections, sometimes between ideas and sometimes between people. At its best, folklore studies connects people and ideas, making it clear how all of us—no matter who we are or where we live—think our ways through the world with the resources we have at hand. Those things “ready to hand,” which we sometimes call vernacular, are the foundation for folklore studies, which sees the warp and weft of the ordinary as the only way to answer big questions. In collecting tale after tale to assemble archives of humanistic “big data,” early folklorists contributed to our understanding of human history as well as human psychology.

The strength of folklore studies as a domain has always been in the possibility of larger syntheses based on its diverse, and sometimes diffuse, data. Our focus at the local level is a strength, a commitment to understanding people as people and not as something other than that, and continuing to work with them as they seek their own place within a world where we all are reduced to so many numbers. If numbers are the lingua franca of our time, folklorists must be conversant.

The first time I realized there was a larger dialogue waiting to be had was when I was overseeing efforts to digitize the contents of the Archives of Cajun and Creole Folklore. We had won a grant from the GRAMMY Foundation and were steadily digitizing fragile recordings and entering information into a database that acted as a catalog. When it became apparent that not everyone understood the opportunity of making such material accessible to anyone with an internet connection, I wrote a grant to create a digital humanities lab so scholars and students alike could create their own “born-digital” materials: both original documentary materials and productions based on those materials.

This desire to reach both within and without more broadly, as well as to do it in a fashion that makes the data, the methods, and the outcomes of the work more accessible to any and all interested others, has been the nexus of the digital humanities: an umbrella term that brings together archivists, media creators, and computation specialists as well as scholars and, increasingly, scientists interested in exploring the synthetic possibilities of the information age. In folklore studies, our work has largely focused on building better, more accessible archives and on exploring new kinds of scholarly outputs and new forms of public outreach that include the possibility of interaction among curators, objects, and their many audiences.

As an Americanist interested in vernacular texts, I was frustrated by how all these high-quality texts, documented by colleagues near and far, were not readily available for comparison. We were the discipline that invented big data textual databases in the form of the tale type and motif indices, and yet these were useless when seeking out contemporary texts. (Because relatively little of the contents of folklore archives has been digitized, these texts remain off-line to this day, which boggles the imagination.)

Adding to my interest in finding comparative texts, as I pored over the recordings and photographs I made as part of the fieldwork that led to my book, The Amazing Crawfish Boat, and pinned things to both a time line and a map, I realized I was seeing networks of people and ideas and the groups within which they trafficked. When Tim Tangherlini invited me to join the National Endowment for the Humanities–funded seminar he had organized on network studies, I jumped at the opportunity. Later, Tangherlini also organized a National Science Foundation–funded long program that explored how the math behind networks, and other statistical methods, could both enhance traditional humanities theories and methods but also be enhanced by them.

That is, there is room in the field to get involved in these broader discussions and in the process to create more room for the field: dismissing the quantitative turn in scholarship of the current moment is as counterproductive as dismissing the turn toward performance that occurred in the last generation. What I find in the ideas and methods of the quantitative turn are realizations and extensions of ideas, and even methods, central to folklore studies. After all, the last third of Vladimir Propp’s Morphology of the Folktale is nothing but tables he compiled into a formula for a body of Russian folktales in the same way Claude Lévi-Strauss used his encyclopedic memory to compile the formulas at the heart of his Mythologiques. The more I look, in fact, the more I uncover startlingly prescient work, like that by Benjamin Colby and Pierre Maranda: work that was inhibited by the technology of the moment but overcame those inhibitions through powerful imaginations.

Inspired by the possibilities, I have found myself part of a larger set of conversations taking place in and between the humanities and the data and information sciences. Much of the groundwork for how texts are processed computationally in the current moment was achieved by computational linguistics and is focused at the level of the sentence. At the same time, the humanities remain dominated by the large texts that are the objects of literary studies. The result, when it comes to something like the study of narrative, is that the debates leap from texts of a few sentences to those of hundreds of pages. Meanwhile, all those mostly middle-sized texts—like folktales, legends, and personal-experience narratives—collected by folklorists across space and time are left out of attempts to build a computational model of narrative. This is my current work: combining advances in discourse analysis with advances in statistical modeling to build programs that come closer to seeing narrative the way humans do. As part of this work, I find myself not only attending the meetings of the American Folklore Society but also the Society for Data Science and Statistics and giving talks to rooms filled with as many computer scientists and mathematicians as literature scholars. The questions are different, but the answers are increasingly the same.

Perhaps most important, in my work as a digital humanist, I have experienced the power and rewards of collaboration. There is so much work to be done, and it requires not only many hands but also many minds. The things I have learned working with librarians and archivists to deposit digital materials and describe them with the correct metadata, and with data scientists to get the algorithms right, have been far more than what I have learned working on my own.

Using Big Data in Folklore Scholarship: Timothy R. Tangherlini

Timothy R. Tangherlini earned his PhD in Scandinavian at the University of California, Berkeley, where he is a professor in the Department of Scandinavian.

The COVID-19 pandemic started its march across the globe in the early weeks of February 2020, gained steam through March, and forced huge numbers of Americans into their houses by April. While the mainstream media presented a sobering yet informative view of the crisis, the internet exploded with everything from quite reasonable suggestions on how best to wash one’s hands to the most convoluted conspiracy theories that managed to link the pandemic to bioweapons research, chemtrails, a globalist Jewish elite, pangolins, and the 5G cellular phone network. The pandemic engendered an overwhelming outpouring of stories that spoke to the widespread anxieties caused by the poorly understood virus and the lack of accessible, authoritative, and trustworthy information. As any folklorist will tell you, rumor loves an information void, and the one caused by the pandemic was an almost perfect vacuum. Rips in the fabric of trustworthy news sources created by the vortex of social media and the current political environment allowed all sorts of stories to rush in to fill that vacuum.

When the COVID-19 pandemic hit, and the internet blew up with memes, videos, and conspiracy theories, our team at UCLA had already been heavily focused on computational modeling of conspiracies (actual) and conspiracy theories (fictional) from social media data (see our article “Conspiracy in the Time of Corona: Automatic Detection of COVID-19 Conspiracy Theories in Social Media and the News” at https://arxiv.org/abs/2004.13783). In early March we had pivoted our research away from the QAnon conspiracy theory to the emergence and dynamics of conspiracy theories about the virus that were spreading across social media. Our goal was to track the formation of these stories and the real-world actions they endorsed, providing the basis for a system to assist analysts tasked with identifying potentially dangerous ideas while supporting positive responses. We had started this work several years earlier by exploring the narrative frameworks of vaccine hesitancy and the anti-vaccination communities. By automatically analyzing thousands of conversations on “mommy blogs,” we showed that communities of belief on social media are remarkably stable, even if there is enormous turnover in the people who make up those communities, and that the narrative framework undergirding the tens of thousands of posts was endorsing exemption seeking, an overlooked activity that had greatly eroded herd immunity across the nation.

Since my earliest training, I have focused on storytelling and, in particular, the interrelated narrative genres of personal experience narrative, rumor, legend, and conspiracy theory. The current age of ubiquitous internet access and easily accessible social media is a golden opportunity for almost real-time collecting from a wide range of groups. Working at a very large scale—that of tens of thousands, if not millions, of stories and story fragments, expressed by individuals in very large groups—creates challenges that the philologically anchored close-reading methods of the humanities are not well equipped to handle. At the same time, this enormous scale, already present to some degree in the historical archives of tradition found across the globe, is something folklorists have long been trained to work with directly or at least to consider; see, for example, examples as widely spread in time as the Types of the Folktale (1910), the Motif-Index of Folk Literature (1932), and the 2016 “Big Folklore: A Special Issue on Computational Folkloristics” special issue of the Journal of American Folklore. Experts in data sciences—including machine learning, natural language processing, and geographic information systems (GIS)—can bridge that gap.

This “macroscopic” approach requires computer-based methods since the scale of the data is well beyond the cognitive limits of a single individual. It would be impossible, for instance, for a single person to read and remember the entire 4chan site, let alone to extract a meaningful understanding of the interrelationships and interdependencies of threads on that site. Yet by working with big data resources, we were able to develop a dynamic picture of the ongoing negotiation of belief organizing the conversations preserved there and potentially understand the implications of those discussions for real-world behaviors in the context of crises such as the COVID-19 pandemic, from the positive (people coming together to sew face masks for neighbors and friends) to the very negative (demonstrators encouraging armed action against statewide stay-at-home orders).

In this project, our problem was a classic one in folkloristics: while we recognize that we can only observe and record performances that are often incomplete, we also recognize that there must be something driving those performances to make them recognizable and, on some level, acceptable to the group. Much of our work over the past decade has been on understanding the relationship between narrative’s deep structures—the limits that a domain of discourse places on “what one can talk about”—and the surface-level, observable phenomena that comprise actual performances, and then on figuring out a way to create a model of those interdependencies. In short, our goal has been to devise a useful model of storytelling at internet scale. Although ethnographic fieldwork is rightfully the gold standard in folkloristics, it is necessarily constrained by problems of sampling, access, and time; the internet provides us with a form of self-archiving folklore: noisy, biased, and chaotic but still the product of collaborative, negotiated performances of informal cultural expressive forms circulating on and across social networks. So we used the internet as our data source and set our sights on developing a formal model for internet-scale storytelling.

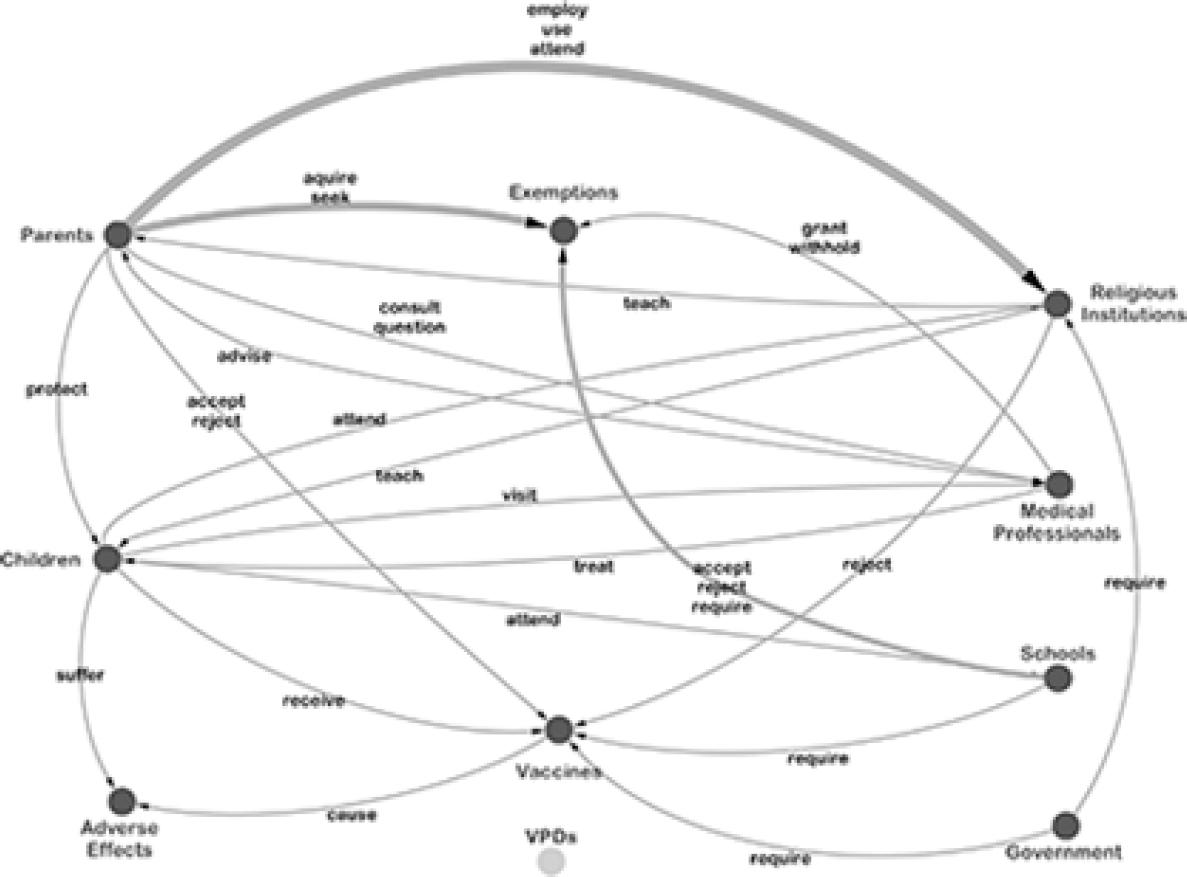

Inspired by the work of Algirda Greimas—published in 1966 in French in the journal Communications—on the interpretation of myth, coupled with the narrative analysis of William Labov and Joshua Waletzky published in Essays on the Verbal and Visual Arts in 1967, we think of a narrative framework as a network graph: stories or parts of stories, which we capture as social media posts or newspaper articles and then activate part of the graph. Over time the activated parts of the graph become more important, making it harder for new terms or relationships to be considered “part” of the narrative. Although the resulting narrative graph can be fairly simple, it provides clear information about not only what people are discussing but also how they are discussing it, even though individual posts can at times seem utterly unconnected (see fig. 1.2). It is worth noting that in the studied conversations, the vaccine preventable diseases (VPDs) are not connected to the graph: the real threat agent is the vaccine. Consequently, seeking an exemption is an understandable strategy for combating that threat.