Tom Neale

An Island To Oneself

Chapter 1: Wanderlust in the Sun

Chapter 2: Shopping List for a Desert Island

Part 2: on the Island: October 1952 - June 1954

Chapter 5: Fishing, Cooking - and Improvising

Chapter 6: The Killing of the Wild Pigs

Chapter 7: Gardening - and a Chicken “Farm”

Chapter 10: The Pier - and the Great Storm

Chapter 11: Saved by a Miracle

Chapter 12: Farewell to the Island

Chapter 13: Six Frustrating Years

Part 4: on the Island: April 1960 - December 1963

Chapter 15: Visitors by Helicopter

Front Matter

Acknowledgements

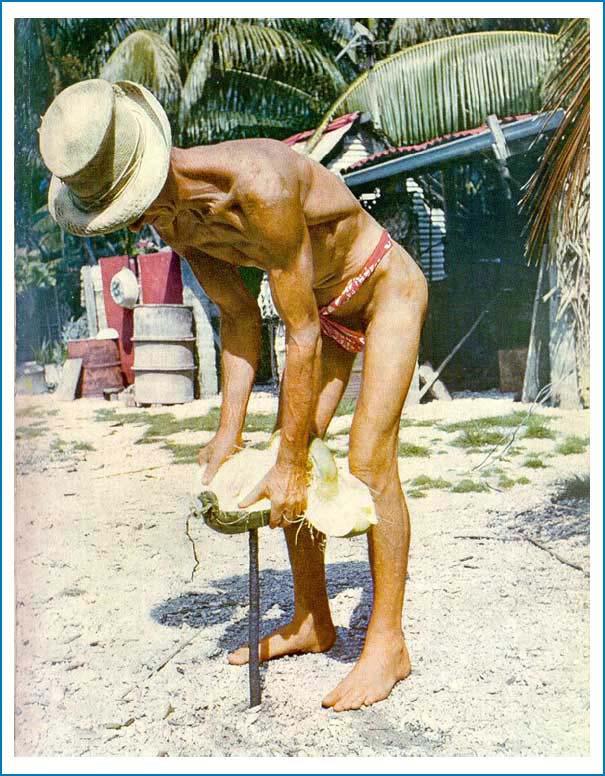

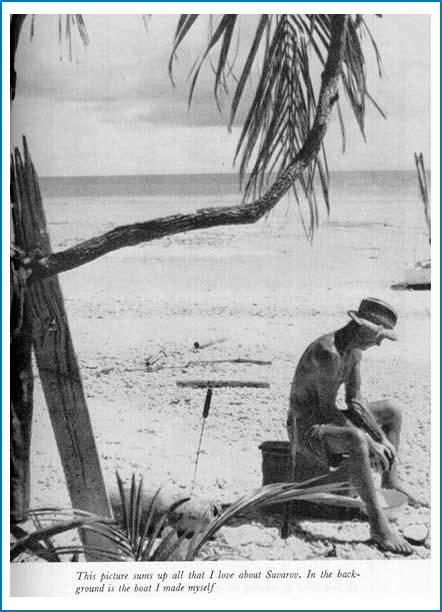

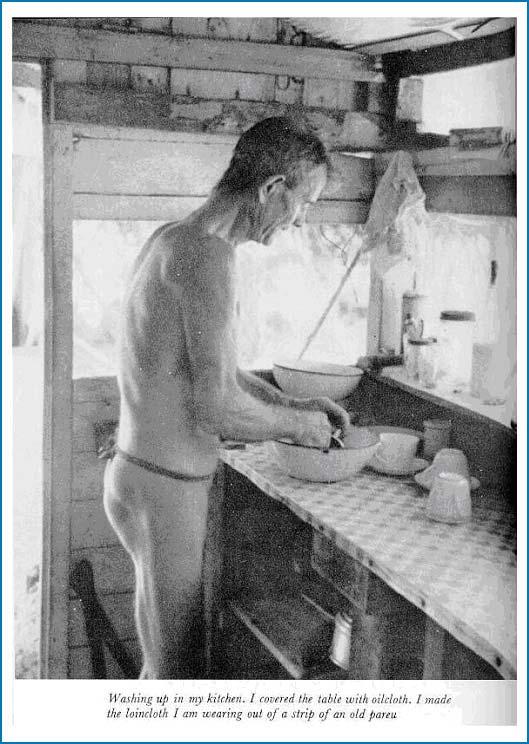

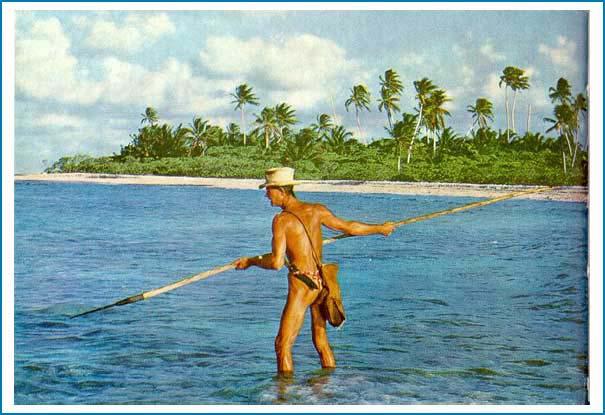

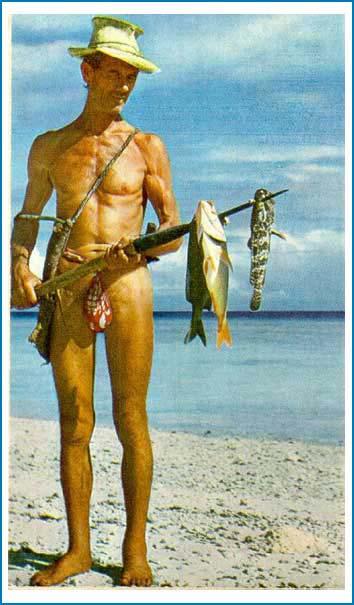

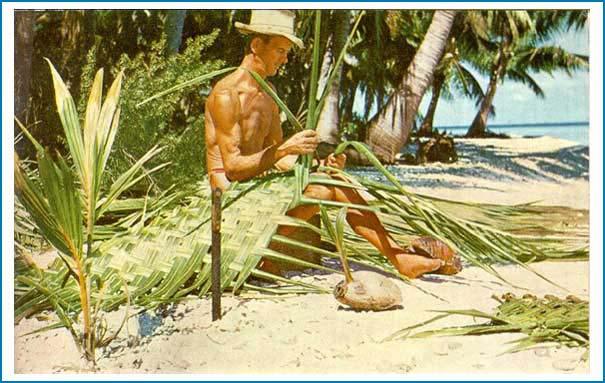

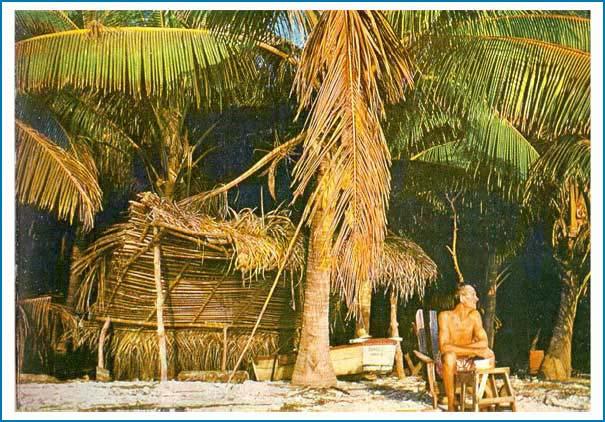

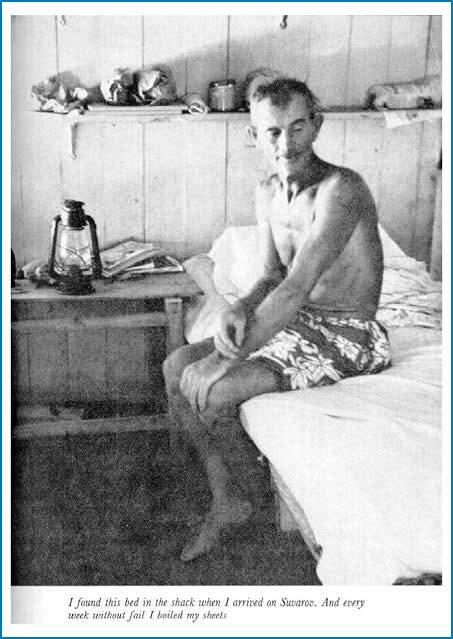

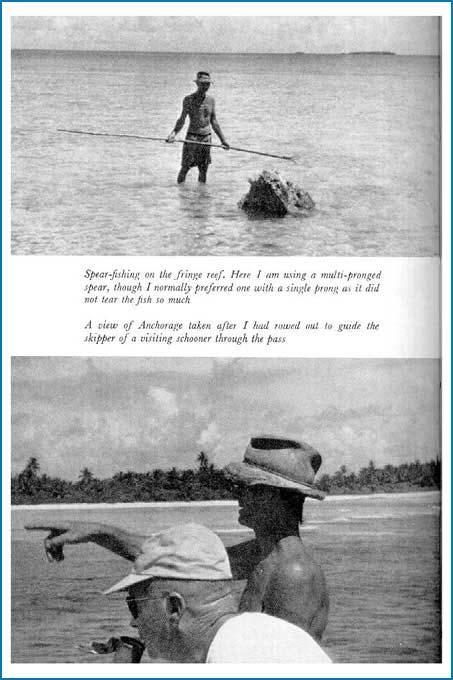

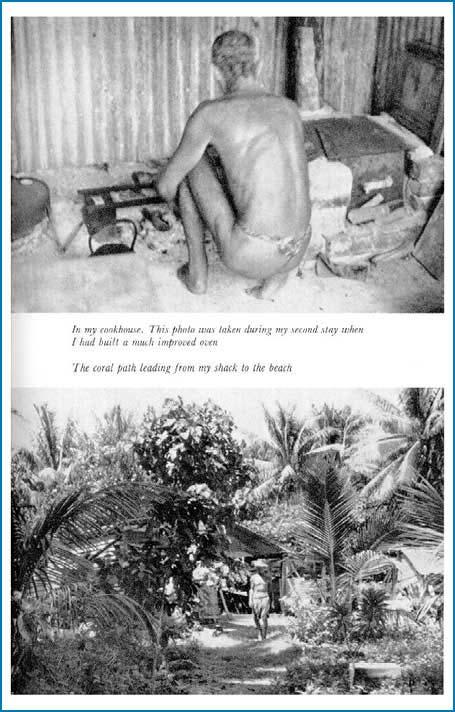

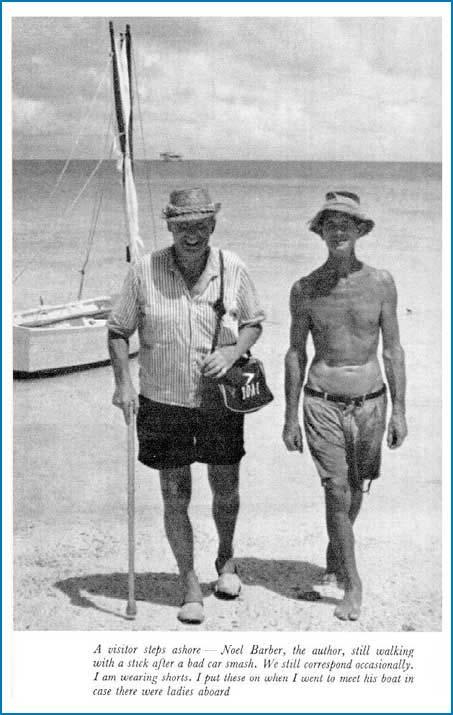

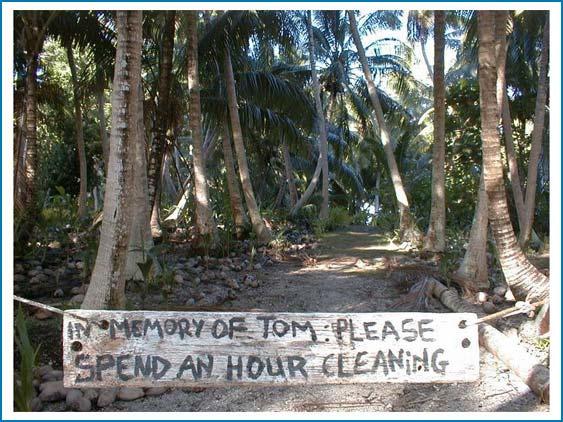

For George Moore Taggart III - My American Friend in The Old Tahiti Days. My thanks are due to “Peb” Rockefeller who took the photographs opposite pages 68, 69, 125, and 126 in this book when he visited Suvarov in 1954. The remaining photographs were taken by Noel Barber and Chuck Smouse when they visited me for the Daily Mail in 1961, and my thanks are due to the Daily Mail, London, for permission to reproduce them.

Author’s Note

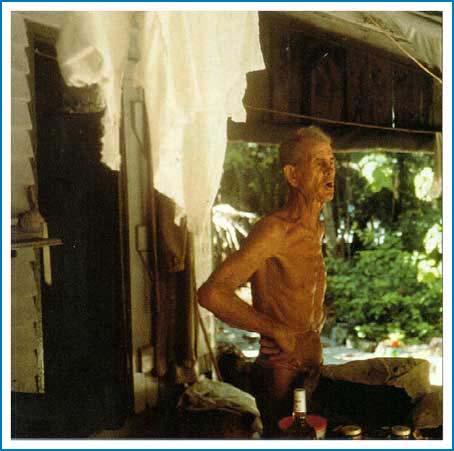

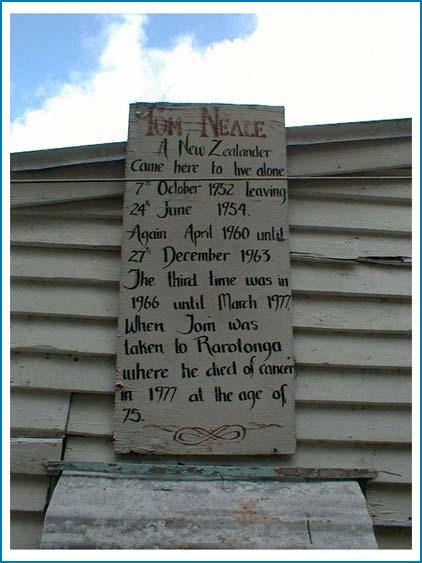

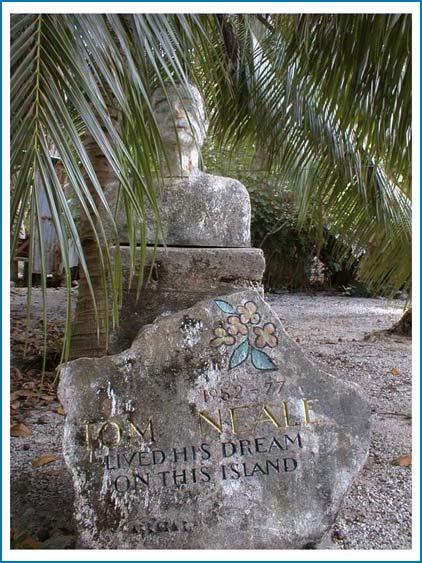

This is the story of six years which I spent alone, in two spells on an uninhabited coral atoll half a mile long and three hundred yards wide in the South Pacific. It was two hundred miles from the nearest inhabited island, and I first arrived there on October 7, 1952 and remained alone (with only two yachts calling) until June 24, 1954, when I was taken off ill after a dramatic rescue.

I was unable to return to the atoll until April 23, 1960 and this time I remained alone until December 27, 1963.

Tom Neale Tahiti and Rarotonga, 1964-1965

Introduction

by Noel Barber

For four rough days I had sailed due east from Samoa in a rusty old vessel called the Manua Tele which I had chartered in Pago Pago. Our destination was Suvarov atoll, a tiny group of islets in a coral reef normally uninhabited but where, it was said, a white man had lived alone for five years.

When I awoke on the fifth morning, the swell had gone, the Manua Tele’s engines were still, and the old tub was rocking gently at anchor. I donned a pair of shorts, picked up a tin of beer and some bananas and went on deck.

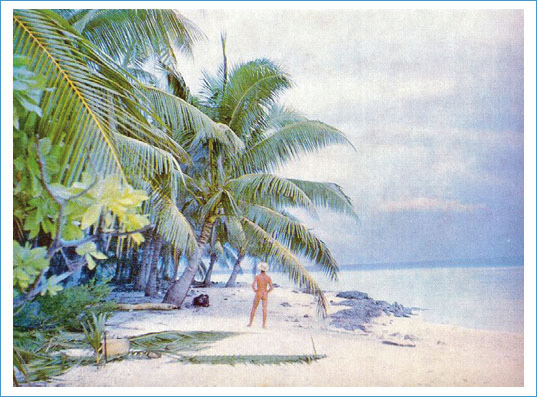

Ahead of us the reef thrashed the water in a line stretching for miles; beyond it, drenched in sun, was man’s most elusive dream, a coral island.

Suddenly, as the Samoan at the wheel searched for the pass through the reef, I saw a flash of movement where the palms met the coral, and a man bounded out and started waving. Through the glasses I saw him run to a tiny boat, push it into the water, and a few minutes later he had a sail up to help him as he rowed towards the Manua Tele. Within twenty minutes he was climbing aboard with the agility of a boy of twenty.

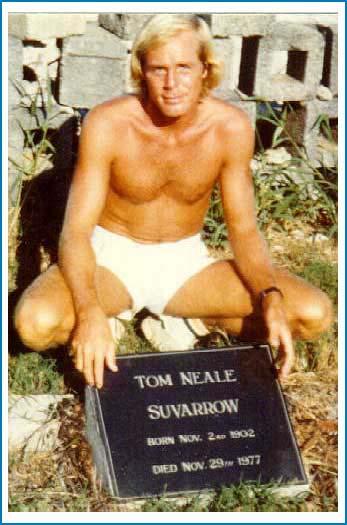

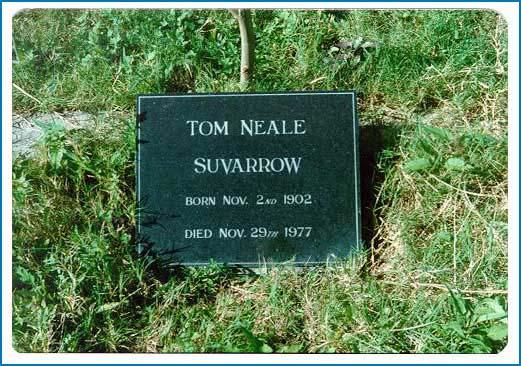

“Not bad for fifty-eight,” he grinned; and this was my introduction to a man who had done what millions of us dream of doing, but never seem to do. For Tom Neale, a New Zealander, had left the world behind for life alone on a coral island so remote from the trade routes that he was fortunate if one ship a year called by chance to disturb his solitude.

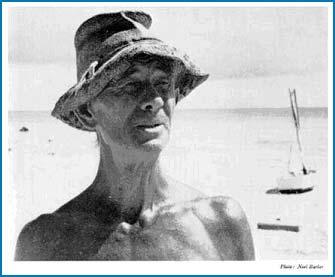

What had made him do it? Was he intelligent–or was he slightly mad? He didn’t look a crank, as he sat there on the deck, the Manua Tele rolling gently in the swell. Tall and spare, his skin was stained dark brown; he wore tennis shoes, a pair of ragged sorts, (“Usually I wear a strip of pareu, but I thought there might be women aboard!”) and a battered old hat. His greying hair was close-cropped. But it was his eyes that fascinated me. Brown and watchful–the alertness accentuated by the wrinkles the sun had drawn on his burned face–they were never still. They had a laugh in them, but they were always restlessly watching–a cloud in the sky, the Samoan mate’s brown back, the size of a wave, me, each time I spoke.

Though I am delighted that Tom has asked me to write an introduction to his book, it is not my place to describe the island and how he met the challenge of living on it. Tom has done that in a story I have found fascinating. I am more concerned with the man himself–with perhaps some aspects of his character that he has not put forward, for I found him very modest, quiet and intelligent, with a wonderful sense of humour and a lively curiosity about events in the world he had left behind. No, this was no crank.

He kept a journal, and its pages were crammed with neat, careful writing. He used an old-fashioned nib–in itself an indication of a character far more fastidious than I would have imagined; for any thoughts that Tom Neale might have lowered his standards simply because he was alone were quickly dispelled. Indeed, of all the anomalies of Tom’s island, nothing struck me so forcibly as the sight of him carefully washing up; holding a glass to the light to be sure it was clean–all incredibly incongruous, for outside, the coconut palms rustled, the sea lapped on the beach, and beyond the reef the lonely immensity of the Pacific started rolling to the nearest coral atoll two hundred miles away.

But Tom was the most house-proud man I ever met. Every cup and saucer was in its right place. The dishcloth was stretched to dry. When I dropped a bit of coconut shell on the veranda, he quickly kicked it away, and twice on that first day he swept out the hut with his home-made broom of palm fronds. And when he made his first cup of good tea for months with the tea I had brought him, he carefully heated the pot first.

“Even when I use old leaves over and over again, I always heat the pot first,” he said, adding almost severely, “I hate tea out of a cold pot.”

I can see him now after dinner, sitting on an old box, leaning forward, drawing an aimless pattern in the white coral dust, enjoying the sheer pleasure of talking, of forming words, for mine was the first ship he had seen for eight months.

But as he talked, I realised with something of a shock that though he was obviously pleased to see me, and was delighted with the stores I had brought him, he would not miss me when I left. He had never even bothered to inquire how long I intended to stay.

Only when I asked him the inevitable question “What made you do it?” was he silent for a long time, and I can remember the scene now on that long, black beautiful night; the hurricane lamp between us, Tom’s mahogany-coloured face half lit, two cups and the empty teapot on the roughly hewn table, one of his cats sitting upright, still as an idol.

“Many people asked me that–even before I left to come here,” he said finally, “and I must admit I’ve answered the question in many different ways; probably to get rid of them because I felt they would never really understand. Sometimes I’ve tried to put my feelings into words. But even then I would wonder, ‘Is that really why I came?’

“The real truth is, you don’t make decisions like this all at once. I’d been growing towards the idea for thirty years.”

Then suddenly he added, half teasingly, “Don’t go getting the wrong idea, though, and thinking I’m a hermit. Do I look like one?” He leaned forward. “I like people–I honestly do. I’m not just evading responsibilities. I suppose really–honestly–I don’t quite know why I did come here in the first place.”

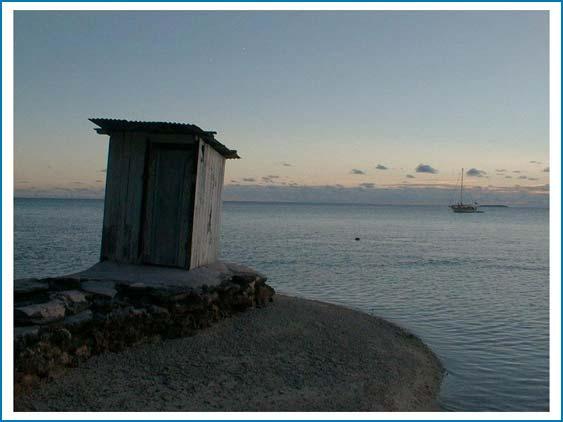

We sat talking far into the night. The moon came up, silhouetting the Manua Tele framed in palms, reminding me of a scene in Treasure Island with the Hispaniola anchored off-shore. But that had been a beautiful island of violence; this was a paradise of peace. Everything was calm and still on the beach. Even for me, a casual visitor, the world had ceased to exist. Here was nothing but peace, for even nature was not hostile.

When the time came for me to leave Suvarov, something very curious happened.

I had, in fact, rather dreaded the moment, possibly thinking of those endless embarrassing farewells on railway platforms; but when the actual moment arrived and the Manua Tele’s boat was ready to take me off the beach, Tom squeezed my hand firmly and said: “It’s been wonderful seeing you, Noel, and I can’t thank you enough for all the stores you brought.”

I wondered how he felt, but I had no time to find out, for as the crew pushed the boat into the turquoise water, he loped back up the beach and vanished in the shade of the coconut palms. He never once looked back.

Was that quick, unemotional farewell a sign of inner contentment or was it a mask to hide his despair at being left alone?

I never knew until I read this book. There is a photo of Noel Barber further on in this book.

Part 1: the Years of Waiting

Chapter 1: Wanderlust in the Sun

I was fifty when I went to live alone on Suvarov, after thirty years of roaming the Pacific, and in this story I will try to describe my feelings, try to put into words what was, for me, the most remarkable and worthwhile experience of my whole life.

I chose to live in the Pacific islands because life there moves at the sort of pace which you feel God must have had in mind originally when He made the sun to keep us warm and provided the fruits of the earth for the taking; but though I came to know most of the islands, for the life of me I sometimes wonder what it was in my blood that had brought me to live among them. There was no history of wanderlust in my family that I knew of–other than the enterprise which had brought my father, who was born in Wellington, though while I was still a baby we moved to Greymouth in New Zealand’s South Island, where my father was appointed paymaster to the state coal mines. Here we remained until I was about seven, when the family–I had two brothers and three sisters–moved to Timaru on the opposite side of South Island.

It was a change for the better. My maternal grandmother owned twenty acres of land only five miles out of Timaru and here we settled down, my father commuting to his new office either by bicycle, trap or on horseback, while I went to the local school where (with all due modesty) I was good enough in reading, geography and arithmetic to merit a rapid move from Standard One to Standard Three.

Looking back, I imagine the real clue to my future aspirations lay in the fact that it always seemed absolutely natural that I should go to sea. I cannot remember ever contemplating any other way of life and there was no opposition from my parents when I announced I would like to join the New Zealand Navy. My real ambition was to become a skilled navigator, but when my father took me to Auckland Naval Base to sign on, I was dismayed to discover that already I was too old at eighteen and a half to be apprenticed as a seaman.

It was a bitter disappointment, but I had set my heart on a seafaring career and did the next best thing. Signing on as an apprentice engineer meant starting right at the bottom–and I mean at the bottom–as a stoker, although I didn’t mind because the job, however menial, would give me a chance to see something of the Pacific.

I spent four years in the New Zealand Navy before buying myself out, and I only left because of a nagging desire to see more of the world than the brief glimpses we obtained beyond the confining, narrow streets of the ports where we docked.

And our visits were dictated by naval necessity–simple things like routine patrols or defective boilers–so that I saw Papeete but never Tahiti; Apia but never Samoa; Nukualofa but never Tonga. It was the islands I always longed to see, not a vista of dock cranes nor the sleazy bars which one can find in every maritime corner of the world.

For the next few years I wandered from island to island. Sometimes I would take a job for a few months as a fireman on one of the slow, old, inter-island tramps.

When I tired of this, I would settle down for a spell, clearing bush or planting bananas. There was always work, and there was always food. And it was only now that I really came to know and love the islands strung like pearls across the South Pacific–Manihiki at dawn as the schooner threads its way through the pass in the reef; Papeete at sunset with the Pacific lapping up against the main street; the haze on the coconut palms of Puka Puka; the clouds above Moorea with its jagged silhouette of extinct volcanoes; Pago Pago, where Somerset Maugham created the character of Sadie Thompson, and where you can still find the Rainmaker’s Hotel; Apia, where I was later told, Michener was inspired to create Blood Mary and where Aggie Grey’s Hotel welcomes guests with a large whisky and soda.

I loved them all, and it was ten years before I returned to New Zealand in 1931. I was then twenty-eight and when I reached Timaru I telephoned my father at his office.

“Who’s that?” he asked.

“Tom.”

“Which Tom?”

“Your Tom!” I replied.

At first he could hardly believe it. But before long he was at the station to fetch me in his car. The old man looked much the same as I remembered him, as did my mother–but my brothers and sisters had grown so much that at first I scarcely recognised them. Ten years is a long time, but before long I was back in the family routine as though I had been away hardly more than a month. Yet, somehow, I remained an outsider in my own mind. I had seen too much, done so much, existed under a succession of such utterly different circumstances, that at times I would catch myself looking at my mother sitting placidly in her favourite chair and think to myself, “Is it really possible that for all these years while I’ve been seeing the world, she has sat there each evening apparently content?”

I stayed for some months, doing odd jobs, but then I was off again, and I knew this time where I wanted to go, for of all the islands one beckoned more than any other. This was Moorea, the small French island off Tahiti, and it was here that finally I settled–or thought I had–in an island of dramatic beauty, with its jagged peaks of blue and grey rising from the white beaches to awesome pinnacles against the blue sky. It is a small island in which, however, everything seems to be a little larger than life. It is an island of plenty. I could walk along the twisting, narrow coast road and pick guavas, coconuts, or paw-paws and pineapples and nobody would be angry. The French, who had superimposed their wonderful way of life on the people, took care that Moorea should remain unspoiled.

Only one boat a day made the twelve-mile trip from Papeete and passed through the narrow channel in the barrier reef. And–when I was there, anyway–providing a man behaved himself, he was left alone, and I preferred it that way. I had to work–indeed, I wanted to work–and there was always bush to be cleared, copra to be prepared, fish to be caught. I really wanted for nothing, and I remember saying to myself one beautiful evening after swimming in the lagoon, “Neale” (I always call myself Neale when I talk to myself), “this is the nearest thing on earth to paradise.”

Life was incredibly cheap. A bullock was slaughtered twice a week and we were able to buy the meat at four-pence a pound. Within a short time of settling down the natives had built me a comfortable two-roomed shack for which I paid them a bag of sugar and a small case of corned beef. Life was as simple as that. I had my own garden, a wood-burning stove, plenty of vegetables, fruits and fish.

My living expenses never came to more than £1 a week–often the total was less–because from the moment I left the Navy I had made up my mind to “batch”–in other words, look after myself completely; do my own washing, cooking, mending, and never move anywhere without being entirely equipped to find for myself. It is a decision I have stuck to all my life. Even now, I am never without my own mattress, sheets, pillows, blankets, cutlery, crockery, kitchen utensils and a battered old silver teapot.

Even as I write, the “housewife” which the Navy gave me the day I joined up is not far out of reach. It is in itself a symbol of years of “batching” which has saved me a fortune. Mine was a simple existence. No furnished rooms to rent, no meals to buy. My only luxury was buying books.

I was very happy in Moorea. I quickly learned to speak Tahitian, I made one or two friends, I worked fairly hard, I read a great deal. My taste in literature is catholic–anything from Conrad or Defoe to a Western; the only thing I demand is an interesting book in bed last thing at night.

It was in Moorea that I first stumbled on the works of the American writer Robert Dean Frisbie, who was to have such an important influence on my life. Frisbie had settled in the Pacific, and had written several volumes about the islands which I read time and time again, though it never entered my head then that one day we should be friends.

I might have stayed in Moorea forever, but around 1940, at a moment when I thought myself really happy, a character came into my life who was to change it in a remarkable way. This was Andy Thompson, the man who led me to Frisbie, captain of a hundred-ton island schooner called the Tiare Taporo–the “Lime Flower.”

I met Andy on a trip to Papeete and immediately liked him. He was bluff, hearty and a good friend, though after that first meeting months would sometimes pass before we met again, for we had to wait until the Tiare Taporo called at Papeete.

We never corresponded.

I was astounded, therefore, to receive a letter from him one day. It must have been early in 1943. Andy was a man used to commanding a vessel and never wasted words. He simply wrote: “Be ready. I’ve got a job for you in the Cook Islands.”

At that time I didn’t particularly want a job in the Cook Islands and Andy didn’t even tell me what the job was. Yet when the Tiare Taporo arrived in Papeete a few weeks later, I was waiting. And because I sailed back with him I was destined to meet Frisbie, who in turn “led” me to Suvarov.

To this day, I do not know why I returned with Andy–particularly as the job he had lined up involved me in running a store on one of the outer islands belonging to the firm which owned Andy’s schooner. The regular storekeeper was due to go on leave and I was supposed to relieve him. On his return, I gathered, I would be sent on as a sort of permanent relief storekeeper to the other islands in the Cooks. I suppose, subconsciously, I must have been ready for a change of environment. Nonetheless, I didn’t find the prospect entirely attractive.

First, I had to go to Rarotonga and here, within two days of arriving, I met Frisbie.

Since this man’s influence was to bear deeply on my life, I must describe him.

Frisbie was a remarkable man. Some time before I met him, his beautiful native wife had died, leaving him with four young children. He loved the islands; his books about them had been well reviewed but had not, as far as I could learn, made him much money. Not that that worried him, for his life was writing and he had the happy facility for living from one day to the next with, apparently, hardly a care in the world. He was, he told me, an old friend of Andy’s, and any friend of Andy’s was a friend of his. It was Sunday morning and, unknown to me, Andy had invited us both for lunch.

I could not have known then what momentous consequences this meeting was to have. None of us suspected it then but Frisbie had only a few more years to live (he was to die of tetanus), and on that Sunday morning I saw in front of me a tall, thin man of about forty-five with an intelligent but emaciated face. He looked ill, but I remember how his eagerness and enthusiasm mounted as he started to talk about “our” islands and told me of his desire to write more books about them. We liked each other on sight, which surprised me, for I do not make friends easily; and it was after lunch–washed down with a bottle of Andy’s excellent rum–that Frisbie first mentioned Suvarov.

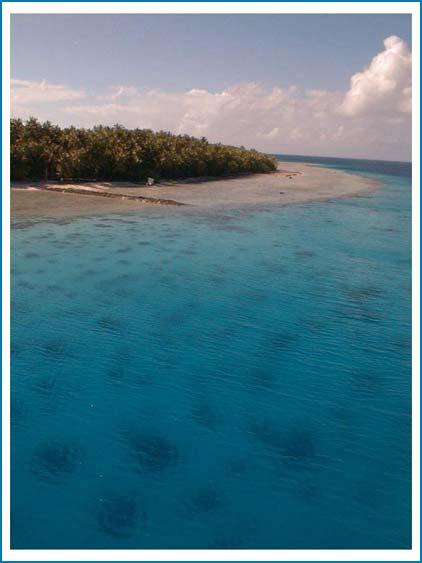

Of course, I had heard of this great lagoon, with its coral reef stretching nearly fifty miles in circumference, but I had never been there, for it was off the trade routes, and shipping rarely passed that way.

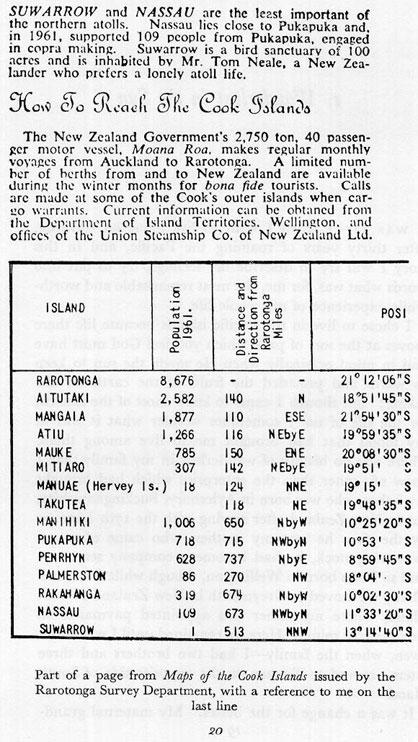

Because its reef is submerged at high tide–leaving only a line of writhing white foam to warn the navigator of its perils–Suvarov, however, is clearly marked on all maps. Yet Suvarov is not the name of an island, but of an atoll, and the small islets in side the lagoon each have their own names. The islets vary in size from Anchorage, the largest, which is half a mile long, to One Tree Island, the smallest, which is merely a mushroom of coral. The atoll lies almost in the centre of the Pacific, five hundred and thirteen miles north of Rarotonga, and the nearest inhabited island is Manihiki, two hundred miles distant.

That afternoon Frisbie entranced me, and I can see him now on the veranda, the rum bottle on the big table between us, leaning forward with that blazing characteristic earnestness, saying to me, “Tom Neale, Suvarov is the most beautiful place on earth, and no man has really lived until he has lived there.”

Fine words, I thought, but not so easy to put into action.

“Of course, you must remember,” he broke in, “There’s a war on, and at present Suvarov is inhabited.”

This I knew–for two New Zealanders with three native helpers were stationed on Anchorage in Suvarov’s lagoon. These “coast-watchers” kept an eye open for ships or aircraft in the area, and would report back any movement to headquarters by radio.

“But they’d probably be glad to see you–or even me,” added Frisbie with a touch of irony.

I got up for it was time to leave. And as I said goodbye to this tall, thin man whose face and eyes seemed to burn with enthusiasm, I said, and the words and sigh came straight from the heart, “That’s the sort of place for me.”

“Well–if you feel that way about it, why don’t you go there?” he retorted.

Storekeeping was not a very arduous job and I soon fell into my new life. My first “posting” took me to Atiu–a small island with rounded, flat-topped hills, and fertile valleys filled with oranges, coconuts and paw-paw; all of it less than seven thousand acres, each one of them exquisite and forever beckoning. From there I moved on to Puka Puka–“the Land of Little Hills”–where seven hundred people lived and produced copra.

The pattern of my life hardly varied, irrespective of the island on which I happened to be relieving the local storekeeper.

Each morning I would make my breakfast, open up the store and wait for the first native customers in the square functional warehouse with its tin roof. The walls were lined with shelves of flour, tea, coffee beans, tinned goods, cloth, needles–everything which one didn’t really need at all in an island already overflowing with fruit and fish! No wonder that as I was shuttled from one outer island to another, I soon discovered that storekeeping was not the life for me, though it did have its compensations.

As long as I kept my stock and accounts in good order, I had a fair amount of leisure, which I occupied by reading. In some stores we carried supplies of paperback books so even my browsing cost me nothing, providing I didn’t dirty the covers. I was batching, of course, and each store had free quarters so I was able to save a little money, especially as in some of the smaller islands the white population could be counted on the fingers of one hand.

Mine was, in every sense of the word, a village store. One moment I would be selling flour, the next I would be advising a mother how to cure her baby’s cough. I carried an alarming assortment of medicines (always very popular) as well as a jumble of odds and ends ranging from spectacles to cheap binoculars, from brightly decorated tin trunks to lengths of rusty chain. I had drums of kerosene for the smoking lamps of the village, lines and hooks for the fishermen who, more often than not, would try to buy these with their latest catch of parrot fish or crays.

I came to be something of a “doctor” and village counsellor, and this I did find a rewarding part of my job, for in the really small islands I was often the only man to whom the people could turn for help. In an indirect way, I was money-lender, too–because I alone had the power to judge the worth of a man’s credit against the future price of copra, and many is the bolt of calico I have sold against nuts still on the tree.

The really sad conclusion about my life as a storekeeper is that I might have enjoyed it had the store been in Tahiti or Moorea or had I never met Frisbie and been fired with the dream of going to Suvarov, for my yearnings were not desperate ones; I didn’t spend all my days mooning about. But always in the back of my mind was the vague feeling, “What a bore life is! Wouldn’t it be wonderful if for once I could see what life is like on an uninhabited island.”

As it was, I seemed to spend my time waiting for the inter-island schooner which, every now and then, would lie off the island, giving the people a reason for wakening for a few hours out of their languid torpor while my stores were unloaded. Occasionally, Andy would sail in the Tiare Taporo, then we would spend an evening on my veranda.

It was an uneventful, placid existence and though I should have been content enough, I soon disliked it intensely. Why, then, did I remain for years as a storekeeper moving around from island to island? The main reason was that every time I was transferred, I had to return through Rarotonga and so met up with Frisbie again.

Then we would talk far into the night about Suvarov (and the other islands of the Pacific) and occasionally, when the rum bottle was low, I was able to persuade him to read the latest passages he had written. He had a deep compelling voice, and talked with as much enthusiasm as he wrote. And towards the end of each evening–and often “the end” only came when the dawn was streaking over the red tin roofs of Raro–we always came back to Suvarov.

“Do you think I’ll ever get there?” I asked one night.

“Why not?” Answered Frisbie, “though probably you’ll have to wait until the war’s over.” I remember we were sitting together sipping a last beer on a visit to Rarotonga, “but then–there’s no reason why you shouldn’t go–that is, providing you equip yourself properly. Suvarov may be beautiful, but it not only looks damn fragile, it is damn fragile–and I should know.”

There was no need to elaborate. I already knew that in the great hurricane of 1942, sixteen of the twenty-two islets in the lagoon had literally been washed away within a matter of hours. Frisbie had been trapped on Anchorage with his four small children and the coast-watchers during this hurricane. He had saved the children’s lives by lashing them in the forks of tamanu trees elastic enough to bend with the wind until the violence of the storm was spent.

I did not see Frisbie again for some time, but we corresponded regularly, and one day when I was feeling particularly low, I picked up his book, The Island of Desire. When I came to the second half I discovered it was all about Suvarov; how he had lived on the island with his children, how he had been caught in that great hurricane. I was enthralled and his descriptions were so vivid that no sooner had I finished the book than I sat down and wrote to him. “One of these days,” I wrote in my sloping, eager hand, “that’s where I’m going to live.”

Frisbie replied, a half joking letter in which he suggested “Let’s both go. You can live on Motu Tuo and I can live on Anchorage, and we can visit each other.”

It made sense. For like me, Frisbie was naturally a solitary man. Like me, he never had much money and yet, sadly, we were never to see the island together. In fact, Frisbie was never to see Suvarov again before he died in 1948.

There was another important reason for remaining in the Cooks. If ever I did go to Suvarov–if ever I had the luck or courage to “go it alone”–I would have to leave from Rarotonga, for Suvarov is in the Cook Islands, and though the inter-island trading schooners rarely passed near the atoll, there might one day be an occasion when a ship would sail close enough to the island to be diverted. But only from Raro.

This is exactly what happened. Suddenly, in 1945, there came an opportunity to visit Suvarov for two days. It was Andy who broke the news to me in Rarotonga.

He was under orders, he told me, to take the Tiare Taporo round the islands, calling in at Suvarov with stores for the coast-watchers there, on his way back from Manihiki.

“I need an engineer for this trip,” he said off-handedly, as though he did not know how much I longed to see the island.

“Care to come along?”

I was aboard the Tiare before Andy had time to change his mind!

When we sailed a few days later, Andy and I were the only Europeans aboard amongst a crew of eight Cook Islanders. We set off for the Northern Cooks–Puka Puka, Penrhyn, Manihiki–which are all low-lying atolls quite different from the Southern Cooks which are always known as the “High Islands.”

It was a pleasant, leisurely trip. I can imagine no more perfect way of seeing the South Pacific than from the deck of a small schooner. Life moved at an even, unhurried pace. I did not have much work for the Tiare carried sail and the engine was seldom needed. Our normal routine was to sail for a few days until we reached an atoll, lay off-shore, discharging cargo, take on some copra and then sail off again into the beautiful blue Pacific with white fleecy clouds filling the sky above.

The night before we reached Suvarov, we lay well off the atoll without even sighting it, for Andy, a good navigator, had no intention of risking his ship during the hours of darkness. All through the night we could hear the faint, faraway boom of the swells breaking on Suvarov’s reef. Though there was no moon, it was clear and starry, and I stood on deck for a long time, listening, filled with an emotion I cannot even attempt to describe, until finally I fell asleep dreaming of tomorrow.

Dawn brought perfect weather and we began to approach the atoll at first light, though it lay so flat that for a long time we could not make out the land ahead.

We had a good wind and full sail, and the Tiare must have been making four knots without her engines as I stood on the cabin top, the only sound the lap of the water and the creaking of wood, shading my eyes until at last I caught my first glimpse of Suvarov–the pulsating, creamy foam of the reef thundering before us for miles, and a few clumps of palm trees silhouetted against the blue sky, the clumps widely separated on the islets that dotted the enormous, almost circular stretch of reef.

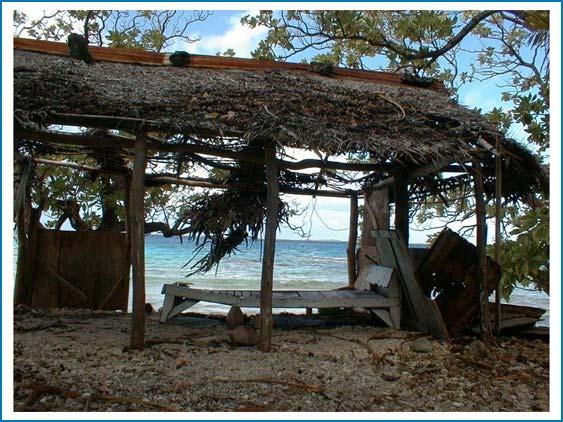

The air was shimmering under a sun already harsh as Andy took the Tiare towards the pass, and Anchorage started to take a more distinct shape. I could make out the white beach now, an old broken-down wharf–a relic of the days when attempts had been made to grow copra on the island–and then some figures waving on the beach.

From the south end a great flock of screaming frigate birds rose angrily into the air, black and wheeling, waiting for the smaller terns to catch fish so they could steal them.

How puny the islets seemed in the vast rolling emptiness of the Pacific! Frisbie had called them fragile but they were more than that. To me they looked almost forlorn, so that it seemed amazing they could have survived the titanic forces of nature which have so often wiped out large islands. Had they been rugged, then survival would have been easier to appreciate, but none of the islets ahead of us in the lagoon was more than ten or fifteen feet above sea level, so that only the tops of the coconut trees proclaimed their existence.

The chop of the sea ceased, for now we were in the lagoon, and it was as though the Tiare were floating on vast pieces of coloured satin. We edged towards Anchorage very slowly through a sea so still that our slight ripple hardly disturbed it. Like many South Pacific islets, Anchorage–lying just inside the lagoon–is subterraneously joined to the main reef by a submerged “causeway” of coral.

And so, as I looked down into the water, I thought I had never seen so many colours in my life as the vivid blues, greens and even pinks that morning; no painter could have imitated those patterns formed by underwater coral at differing depths.

Then the anchor rattled down. We put a ship’s boat overboard and a few minutes later I was wading ashore through the warm, still water towards the blinding white beach.

Common politeness made me greet the five men living there–each of them desperately anxious to go home as soon as possible!–but as soon as I decently could, I went off alone, and on that first day I took a spear and my machete–a French one I had bought in Tahiti, more slender and pointed than those of the Cook Islands–and went along the reef, spearing the plentiful fish I discovered in the reef pools and so lazy that one could hardly miss them.

In the evening, I had supper with the coast-watchers and looked over their shack with the secret, questing eyes of a man wondering if one day he would inherit it.

It seemed ideal. The tanks were full of good water, and when I went for a stroll I discovered a fine garden they had made out of a wilderness.

The watchers were only anxious to leave. How different are men’s attitudes to life! They were agreeable, cheerful and noisy–and delighted with the stores we had brought them–but theirs was a forced gaiety, hiding their anger that war should have played them such a dirty trick as turning them into castaways on a desert island.

On the second day, Andy and I took a ship’s boat to the islet of Motu Tuo six miles across the lagoon, where the native boys caught coconut crabs and fish and lit a fire to cook our picnic lunch.

And when lunch was over, I turned to Andy and said simply, but with utter conviction, “Andy, now I know this is the place I’ve been looking for all this time.”

It was to take me seven more years before my dream came true. Seven long years before another vessel from Rarotonga passed anywhere near the island, seven years during which I reached middle age. Perhaps it was this consciousness of time passing, perhaps this and the dreariness of my job that brought an increasing heaviness of heart which I only managed to struggle against by clinging obstinately to the hope that I would one day get back to the island.

In 1952 my opportunity came. Dick Brown, an independent trader in Rarotonga, had gone into the shipping business after the war, buying a long, narrow submarine chaser of less than a hundred tons which he had converted into an inter-island trader. She was called the Mahurangi, and quite by chance I heard that on her next trip she was going north to Palmerston Island and then to Manihiki. I did not need a map to know that the course passed right by Suvarov.

In all my years in the Cooks, I had never heard of a trading vessel sailing this direct route; it was an opportunity which might never come my way again.

I totted up my finances. I had saved £79. I went to Dick and asked when he was sailing.

“In two weeks,” he replied.

“How much would it cost to divert on the way to Manihiki and take me to Suvarov?”

He scratched his head, figuring.

“Thirty quid.”

It seemed a lot of money, especially when the Mahurangi must pass almost within sight of Suvarov and could have dropped me off with little trouble. But diverting a vessel is always expensive and I did not argue.

“Done!” I said, and we shook hands on it.

I had just two weeks to gather together everything I thought a man would need to survive on an uninhabited coral atoll. Two weeks–and £49.

Chapter 2: Shopping List for a Desert Island

Three minutes … after so many years of waiting. Only three minutes to settle my passage, and the whole transaction concluded in an almost comically casual fashion.

I walked slowly back to the unfurnished room I was renting for 7s. 6d. a week in the valley behind Raro, praying I would not meet anybody; I had to be alone–just for a little while. I was not thinking–not yet–of the dozens of preparations which I must make within a very short time. Instead, as I walked home in the hot sunlight, my mind went back to that day with Andy on the Tiare Taporo, when he had edged into the lagoon, and I had had my first real impression of Anchorage. I could see it in my mind’s eye now as I walked along and could still hardly believe that in a little over a couple of weeks I was going to be back there again. How excited Frisbie would have been. But poor Frisbie had been dead now for four years.

In my room I filled the kettle and made some tea on my primus, but was unable to bring myself to eat anything. My first overwhelming excitement was replaced now by hundreds of different jangling thoughts. For no reason I suddenly thought, “I mustn’t forget fish hooks.” In this daze I actually wasted several minutes mentally wrangling as to whether or not I ought to take any baking powder. Tea over, I went to wash up, and found myself saying almost crossly, “Neale, you’ll need some new dishcloths.”

I had only a fortnight before I sailed and there was so much to do. Nor could I turn to my friends for advice, for after all what would they know about living on a desert island? Even Andy was away at sea. Now the great moment had come, I was alone.

And maybe this was the best way, because once I calmed down, I discovered I really knew exactly what I would need. It was just a matter of getting things sorted out in my mind, so that the sudden thoughts that kept rushing in–like “I must get a crowbar!”–“How will I stop my tea going fusty?”–were pigeonholed in some sort of order.

I forced myself to concentrate on the island. I knew the coast-watchers had left some years ago, but I remembered now that they had had a flat-bottomed boat almost like a punt–and the chances were it would still be there. But would it be seaworthy? I made a mental note to buy a few copper nails.

I do not know how long I sat there–probably a couple of hours–whilst I jotted down the most vital items on an old bit of paper. But oddly enough, once I had got up and returned to the familiar world outside my shack, I never needed that piece of paper again. For my requirements now seemed written like a list in my mind where I suppose they had probably been accumulating subconsciously throughout all the years of waiting.

I was not afraid. That I can honestly say. Perhaps I was a little overawed by the challenge I had taken on. I was fifty now. And this dream of mine had been essentially a dream of youth. Was I too old now to turn this dream into successful reality? I flattered myself I was still in excellent shape, but there was no doubt that physical hardship would fall more heavily on me than it would have done twenty years ago; and then there was the possibility of falling ill…

By the following day, however, I was back to normal–and I started as efficiently as I could to make an inventory of my possessions. I still have it on faded pieces of paper, dated August 1952. There are several lists; one headed “Personal Effects,” another “The Kai Room” (“Kai” is the native word for eating, so my kai room list contained all the things I used for eating and cooking). The third list was headed “Tools.”

How well I remember my very first purchase. It was a sack of Australian flour, from a shipment which had just arrived. This was a rare luxury in Raro as we naturally bought everything we could from New Zealand, but I had cooked with Australian flour from time to time and knew from experience that it would keep much longer than the local brand.

I also knew that once the news of its arrival got around, there would be a run on it, for the South Seas stores are really more like warehouses than shops, and when shipments of new lines arrive to be piled up against the shelves of the barn-like buildings, everyone in town rushes to buy. So I was down at Raro’s “shopping district” as soon as the stores opened, asking the assistant at Donald’s, whom I had known for years, “Any of the Australian flour left?”

“Sure, Tom,” he replied. “How much–a couple of pounds?

“How much is it?”

“Sixpence a pound.”

“Oh well,” I pretended to hesitate, secretly enjoying the joke, “Might as well take a fifty-pound sack!”

He nearly dropped it; and at that moment the wife and daughter of a Government official came in, and stared in astonishment at the sight of Neale buying a whole sack of flour, so on the spur of the moment I added, as casually as I could, “While I’m here, I’d better take a seventy-pound bag of sugar!” After that, the news was soon round Raro–even though I said very little myself. But you can’t keep secrets on an island of only eight thousand people, especially when I–normally so careful–began to buy goods by the sackful. Most of the stores like Donald’s or the Cook Islands Trading Company–both famous island firms–had their functional buildings grouped on or near Main Road between the solid white building of the Residency and Avarua harbour, and now I started shopping in earnest.

I came in for a lot of good-natured banter. After all, I had been on friendly terms with some of the assistants for a long time, and the sight of me staggering out of Donald’s with enough coffee beans to last a year was bound to provoke curiosity or mirth.

At least I faced no problems as far as my “personal effects” were concerned.

These consisted of a couple of pairs of long trousers, a few singlets, three or four light shirts, two pairs of khaki shorts, three pareus (a sort of native sarong), two pairs of sandals and a raincoat. Naturally, I also had my Navy “housewife,” a razor, an old shaving-brush, a toothbrush, and a pocket-knife.

My sleeping gear was simple, although you could hardly call it extensive. I had my kapok mattress, a pair of sheets, an ex-Navy blanket, another lighter blanket, two pillows, two pillow slips and two towels. I planned to roll the whole lot up in the mattress, which I would wrap round with some old pandanus matting for protection when the time came to sail.

I needed only a few other personal effects. I invested in thread and needles for my “housewife”; I bought twenty-four razor blades which would last me some years, for I had long since learned that by sharpening them in a glass under water, I was able to use the same blade for three months or so. I thought I would probably shave twice a week, though I received several amiable suggestions that it would be cheaper–and more in keeping with my illustrious predecessor, Robinson Crusoe–to grow a beard. The same assistant who sold me the blades also asked me why I didn’t have all my teeth out before leaving instead of wasting money on the four tubes of toothpaste I bought.

Yet the interesting thing is that during the fortnight there was nothing malicious or sarcastic in any of the humour. Nobody was trying to take a rise out of me; indeed, I had a feeling, as I suddenly became a sort of local curiosity, that most people were secretly envying me.

I remember going into Donald’s and ordering two pairs of rubber-soled tennis shoes which I knew would be necessary to protect my feet when fishing on the coral reef. The salesman was an old pal of mine, and after saying jokingly, “Want anybody to carry your bags?” he added quite earnestly, “Two pairs isn’t enough, Tom. You know the islands better than I do, but let’s face it, you’ve always been near a store. What’s going to happen when these shoes wear out–or if you lose them?” He was right–and I bought six pairs. It turned out to be a very wise decision.

I planned to pack my clothes in an old suitcase and an equally ancient but serviceable Gladstone bag. Wonderful bags, the Gladstones–they have a great capacity for stretching and into this one, besides my clothes, I tucked a supply of writing materials; two bottles of ink, half a dozen spare nibs, some paper and envelopes, two big Collins “Trader” diaries–a page to a day–and a calendar.

As the day of departure drew nearer, I paid almost daily visits to the Mahurangi which lay in Avarua harbour. I knew most of the Cook Island crew–indeed, one or two of them had sailed with me on other vessels–and I would stop and chat with them, perhaps drawn towards them by a common love of the sea, perhaps because I knew they would be taking me to Suvarov, perhaps because I needed some reassurance; and when Dick Brown, who regarded my frequent visits with amusement, asked one morning, “What’s the trouble, Tom? Scared we’ll leave without you?” I suddenly felt a little cross and answered seriously and surlily, “You can’t. I’ve paid my passage money.”

For the truth is, I probably was a little frightened. It was never a predominant emotion–I never for a moment considered abandoning the enterprise–but, well, there were the odd times when I wondered if I weren’t a bit too old, and there were times when I asked myself if I really realised what life would be like without another human being to talk to for months on end.

I would hardly have been natural had I not occasionally felt this way, but the flashes of despondency always passed quickly. Quite apart from the fact that I had a great deal to do, I now became quite touched by the way people I hardly counted as friends rallied round. One day, staggering home with several parcels, a woman I knew only slightly offered me a lift in her car, and when we reached my shack in the valley she said, “Tom I envy you. It’s the sort of thing everybody would love to do. I’ve got a very good barometer I never use–I’d like to lend it to you.”

It was exactly what I wanted but could not afford, and I accepted it gratefully.

Then when I had difficulty finding two heavy strips of flat-iron which I wanted as firebars to rest on stones, the P.W.D., (Public Works Department) for whom I had worked occasionally, offered to give me a couple. A Government department!

I even had more than one proposition from the ladies. And I may say that I was tempted, for the Cook Island women are not only handsome but wonderfully adaptable, used to hard work, and can turn their hands to anything. Frisbie had found great happiness with his native wife, so when one woman of about thirty, the sister of a Cook Island friend, quite seriously offered to come (adding ingenuously, “You don’t need to marry me!”) I definitely considered the possibility.

However, I decided against it. I had been batching so long I really didn’t need a woman. And, perhaps most of all, the prospect of being cooped up with a woman who might eventually annoy me, of being imprisoned with her–like a criminal on Devil’s Island, without hope of escape–made me shudder. I would be better off as a middle-aged bachelor.

Curiously, those of my acquaintances who (sometimes facetiously and with sly winks) suggested I should take a woman to Suvarov all seemed most concerned lest I should fall ill alone, and regarded a “wife” as a necessity in case she had to play the role of nurse.

Indeed, the most persistent question posed by my friends during these last two hectic weeks was, “Aren’t you afraid of illness?”

Was I? I don’t think so. I cannot deny that occasionally a moment of apprehension flitted across my mind, particularly at the thought of an unexpected accident such as a broken limb. But any fears were fleeting. I couldn’t allow myself to be afraid, otherwise I might just as well go back to storekeeping. And I have always been fit, apart from the odd dose of fever. My eyesight was good, and as far as accidents were concerned, men like myself who are used to living very close to nature gradually acquire a special sort of protective instinct when using tools like saws or axes, or heating metal or climbing trees. It is the tenderfoot who usually cuts or burns himself. Automatically, I was in the habit of taking far greater care than the normal man.

I was, however, worried about the possibility of toothache, for that was something I could not control. I had had an upper plate for several years, but I went to the dentist and told him to take out as many of my bottom teeth as he wanted! It says much for my simple life that he only extracted one–and I have never had toothache.

I had to take some medical precautions, but I could not afford to take a really extensive kit, much as I would have liked to have it. Drugs cost so much. So I had to content myself with plenty of bandages, sticking-plaster, Germolene, a supply of Band-Aid, a little cotton wool, one bottle of Vaseline and a half-pint bottle of Mertholiate, plenty of antiseptic, some sulphur thiazole (M & B) tablets for fevers. I bought no aspirin because I never get headaches.

Of course, I did not spend one day buying food, or another selecting pots and pans. Like any housewife, I became a familiar figure in the local stores, carrying my shopping lists and buying whatever I needed from the heaped shelves and counters. I used to stagger home with my purchases, tick them off on my list and then pack them in a motley assembly of variously sized parcels, making a note of the contents of each packet.

I spent a great deal of time on my food list. I knew I would never starve on Suvarov, for I expected to find coconuts, bananas, paw-paw and breadfruit, in addition to unlimited fish and crayfish. I also knew that the coast-watchers had kept fowls though I could not be certain if there would be any left.

But obviously a diet consisting of only island produce was going to be monotonous, and since I had £49 I saw no reason for not laying out a substantial part of it on supplies that would at least tide me over until my garden was producing.

I had a pretty good idea of what I wanted, for after all I had been cooking my own meals for half a lifetime and I went from store to store buying the different basic foods. By the time I had finished, my stock of purchases, piled up in my shack, was not unimpressive.

I decided quite deliberately to spend some of my money on gastronomic luxuries which I really did not need, for though I had proved many times that I could live on native or island food, I had noticed over the years how the sudden switch to such a spartan diet tended to make me a little depressed. Breadfruit and coconuts sound all very well in adventure stories, but nobody can deny they are monotonous. I felt I should ease my way into the new life ahead of me by starting out with some of the foods I enjoyed.

After all, I didn’t really know what lay in the future. I flattered myself I would never be lonely, but how could I tell? I remember having a beer one evening with a friend, and when I pooh-poohed his suggestion that I might be bored with my own company, he pointed out quite seriously, “I know you enjoy being on your own, Tom, but remember you’ve always had somebody around–if only to call them a damned nuisance! What’s going to happen if you’re alone–and lonely?

Nobody to shout at–not even an enemy!

He was right, of course. How could I tell what I would feel in circumstances which I had only so far imagined? Well, at least I could get some good food to cheer me up if I felt too low. I went down to Donald’s the next morning and promptly bought a dozen one-pound tins of jam and a dozen tins of sweetened condensed milk!

I already had my flour and sugar, a forty-pound bag of coffee beans, and now I bought a forty-pound tin of Suva biscuits, also known as “cabin bread”, which I had chewed for years on the inter-island boats where it was always produced when the flour gave out–as it regularly did. I bought it for the same reason–to use when my flour gave out, or went bad. These biscuits were about four inches square, about ten to the pound. I chose my sealed tin with great care, checking that no seams were broken or punctured, for tins often arrived from Suva in bad condition.

Though I hoped there would be fowls on the island, I felt I had to take some meat with me, so I bought two dozen tins of bully beef to eat on special occasions, together with ten pounds of beef dripping which I sealed up with sticking plaster in an old sweet tin. I became a regular cadger of old sweet tins–even though sometimes I had to pay a shilling each for them. I needed several more, including two in which I sealed up twenty-five pounds of rice. I also bought some old screw-top jars in which I packed five pounds of salt.

I was now getting near the end of my food list, though I had still not bought my tea. Making a cup of tea just before sundown at the end of a day’s work had been a ritual of mine for years, but I reluctantly decided to limit myself to two pounds. So often in the past I had kept tea too long until it went fusty. It would be a waste of money to take a larger stock, though the very day I took the tea back to my room I repacked it in small containers–any tins I could find, such as baking-powder tins with press-top lids, which I filled right up to the top so there would be virtually no air space, and then sealed each lid with a rim of sticking plaster.

For a similar reason, I only bought four one-pound tins of butter. However carefully it is packed, butter invariably goes rancid after a time.

Tobacco was a real luxury. I don’t smoke a great deal, but one cigarette has always seemed to go with that evening cup of tea I love so much. I bought half a pound of tobacco and a dozen packets of cigarette papers.

At first I was unable to decide whether or not to take a shotgun. I had heard rumours that the coast-watchers had left some pigs on the island, which would be quite wild by now, perhaps savage. And, too, I knew there were plenty of birds on Suvarov. But there were several reasons against taking a gun. I don’t like killing living things; nor could I really afford a gun. But perhaps the deciding factor was that I was afraid of becoming dependent on a weapon which would be valueless when the last cartridge had been fired. I felt I had to meet the challenge of Suvarov on terms which would not change with the years. For the same reason I refused to take a small battery-operated radio. I imagine that subconsciously I was afraid I would miss its company after the batteries had run down.

Those stalwart friends of the P.W.D. lent me a pick and shovel; a storekeeper gave me a kerosene case which was made to hold two square four-gallon kerosene tins. The two empty tins were thrown in with the case. I cut the tops off each tin and then packed them both, and the odd spaces around them, with some of my smaller belongings. I knew that once I reached the island the tins would be invaluable for boiling clothes.

I even managed to swap a shirt for a crowbar which I considered a vital necessity. It was, in fact, the transmission shaft of an old model “T” Ford, which I took to a blacksmith who sharpened one end to a point and the other to a chisel edge.

My money–to say nothing of time–was running out, yet there were several tools I badly needed, despite the fact that I had accumulated quite an assortment over the years including chisels, a hacksaw and carpenters’ saws, an axe and tomahawk, a couple of machetes, a sheath knife, as well as pliers, an adjustable spanner, and things like a hammer, screwdriver and a rat-tail file.

All the same, I required a few more items, which I bought during the last week. I needed a couple of really good chisels for I expected to find empty fuel drums left by the watchers. I bought a pair of tin-snips in case the tin roof of the shack should need attention. And when I was in the hardware store, it suddenly seemed a wise precaution to buy two tins of paint to protect any new building I might have to erect. I needed some spare hacksaw blades and when I bought some eighteen-inch lengths of round iron, with the idea of making them into spears, I had to buy two extra files. I had made enough fish spears in the past to know that even the toughest file doesn’t last forever. Then I bought a selection of nails, a hundred assorted fishing hooks and a spare hank of fishing line. Lastly I bought a small vice, which I would need if ever I had to heat and shape metal.

While accumulating all this gear, I was also busy buying seeds for the garden I knew I would have to make. I bought packets of tomatoes, cucumbers, rock melon (known in Europe as cantaloupes), water melon, runner beans and Indian spinach, which trails along the ground with thicker, fleshier leaves than ordinary spinach.

I also purchased some shallots, a few tubers of sweet potatoes or yams–known in the Cooks as kumeras, an old Maori word–which I knew would quickly send up shoots which could be pulled out and planted. Finally, I bought two banana shoots in case the banana trees on the island had been torn down by a hurricane.

By now, my tiny shack was jammed to the ceiling with crates and parcels, and I had barely enough room to turn around when I made myself a cup of tea. Yet the shopping was not quite ended, for I still had to buy one or two things for my kai room. I had very nearly all I needed, for my belongings accumulated over the years included everything–crockery, cutlery, glasses, tin-openers (I never travelled without two), enamel and zinc bowls, a hurricane lantern and a glass table lamp, even a coffee-grinder as well as a coffee-pot, dishcloths and tea-towels and, above all, my old silver teapot which I had used since I left the Navy.

In addition, I had about a dozen square one-gallon screw-top glass jars which fitted into their original case. I had bought them about a year before with Suvarov in the back of my mind. They would be invaluable for storing the food I had bought in bulk; however, I did not plan to fill them before we reached the island in case they got broken on the voyage.

I bought several more articles for the kai room. Firstly, I decided to invest a precious £2 10s. on a six-pint cast-iron kettle, which would not deteriorate in the same way as aluminum when used over an open fire.

I also bought a big square of kitchen linoleum for the table. Throughout my “batching” days I had always insisted, even when alone, on eating off a table cloth, but for the island I thought washable linoleum would be simpler.

Otherwise, the rest of my kitchen purchases were fairly simple–plenty of spare wicks for the lantern and lamp, twelve dozen boxes of matches and four five-gallon tins of kerosene.

And now I gave some thought to the “home-front.” I decided it was imperative to take a cat, for though I knew Suvarov had virtually no insects or mosquitoes, it did have a colony of small indigenous rats. With all my carefully sealed tins, it was unlikely they would eat me out of shack and home, but I just happen to hate rats. As I was already the possessor of an old cat with a kitten I decided to take them both with me, and so that they should travel in style I built a special box to house them for the six-day boat journey.

We were not old friends. As a matter of fact, I had only had the mother cat for a very short time, and she was a confirmed thief which seemed a good reason for calling her Mrs. Thievery. The son I named Mr. Tom-Tom.

Only one thing more was necessary to make me completely self-sufficient, and this was a dozen large, volcanic stones–beyond price, but without any financial value. I dug them out of a creek bed not far from where I lived and carried most of them back to my room–which was now beginning to look like a warehouse– one at a time on the saddle of my bicycle.

Each one of these large stones weighed between eight and twelve pounds. I knew stones like this just couldn’t be found on Suvarov and I needed these heat-resisting stones to make a native oven. Coral is no use, for it crumbles after being used only once or twice.

With the last of my money I now went in search of my greatest luxury–a few books. Two days before the sailing date, I spent a morning browsing among the paperbacks on sale along Main Road. I had a few books already by Defoe, Stevenson and other favourite authors. Frisbie’s Island of Desire was certainly amongst them, but when it came to spending my last few shillings on reading matter, my choice was dictated by the stocks I could inspect. I knew that the coast-watchers had left some books on the island, but I had no certainty that they would please my taste. I had to take a few of my own choice–not many, for I derive great pleasure from re-reading the same book (so long as I like it), but I was able to pick up three books by Somerset Maugham, two by Dickens (including Oliver Twist), Mutiny on the Bounty by Nordhoff and Hall (whom I had met on occasion), and several rather poor quality Westerns and Edgar Wallace thrillers which featured predominantly on the local bookshelves.

On the last night but one, when I was riding my bicycle to the friend who had promised to keep it for me, I stopped by a small general store and picked up a book which was to give me great pleasure in the months ahead. Indeed, I must have read it a score of times. It was a dog-eared, second-hand copy of Lord Jim.

With this treasure clutched under my arm, I cycled to the house where I was to “park” my bicycle. I was just about to set off on the walk home when, for some ridiculous reason, I took the pump off the crossbar.

“What on earth do you need that for?” My friend must have thought me crazy.

I couldn’t answer. I just felt that I must take everything–just in case it came in useful.

Somehow or other, everything was ready in time. In all, I had twenty-one packages, twelve stones, two cats and my bamboo pole and saplings–plus a bundle of long-handled tools and a broom.

The Mahurangi was due to sail for Palmerston Island on the evening of August 29. That same morning I gathered all my gear together and Dick Brown sent up his lorry to collect it–and me. Having arrived at the wharf, it took us some hours to stow away all this cargo, since I insisted on watching every single bundle as it was stacked away in the after-hold. Had one of these parcels vanished, it could have made all the difference to my life on Suvarov.

The moment had almost arrived. I was leaving Rarotonga perhaps for ever. It gave me a queer sensation and I remember thinking, “Neale, remember you owe the P.W.D. a pick and shovel.” On that last day, Rarotonga–which I had disliked so much because of the work which chained me–suddenly seemed much more attractive than ever before, and the strip of dusty Main Road which separated the lagoon from the shops seemed alive with acquaintances stopping to shake my hand and wish me luck, and there is no doubt that there was an element of sadness behind my confidence.

These were very natural thoughts, but inside I was calm in the certainty that I was doing the right thing. Even more reassuring was a profound belief that I could make a go of it. I was equipped down to the last copper nail, so far as my budget would allow. I had forgotten nothing. All that remained was for me to say good-bye to the friends I had made in the frustrating years spent in and around Rarotonga.

This I did on the last afternoon, after I had watched the final cases being packed in to the Mahurangi.

And then, not four hours before sailing, everything went wrong. At a moment’s notice, the sailing plans were changed. Horrified, I learned that instead of calling at Palmerston the Mahurangi’s orders were to sail directly to Manihiki on a new route which would pass nowhere near Suvarov.

For a time I was unable to believe the news. I almost ran all the way down to the wharf to find Dick. Everything I owned in the world–excepting my bicycle–was on board. I had vacated my room; I had nowhere to sleep, nothing to sleep on, no clothes to wear, no food to eat and no money to buy food.

“You can’t do this!” My voice must have echoed my desperation.

“I’m awfully sorry, Tom–” Dick really did look sorry–“but the Palmerston Island trip is postponed until we return from Manihiki.”

He was very kind, assuring me it wouldn’t be long before my chance would come again. But at that moment I could have cried, even though I knew this sort of thing was always happening on the inter-island trading boats. Life in the South Seas does not know the same tempo as big ports and cities; a few weeks’ delay rarely matters to the island folk brought up in a different tradition. Should they find themselves in my situation, as likely as not relatives or friends will put them up for a week or two, for life is not only easy but cheap.

Many a time in the past, when I was working on the schooners, our sailing directions had been changed at the last moment. But that had been different.

As I stood there on the wharf wondering dully what would happen now, one thought was uppermost–I was virtually penniless. What was I going to do during the period of waiting? It must have been with a sense of desperation that I dived my hand into the pocket of my khaki shorts, and brought out some small change.

“Look–” I showed it to Dick–“that’s all the money I have in the world.”

And it was. The loose coins added up to five shillings and eight pence, for I had deliberately spent all my money before sailing as money would have no value on Suvarov. It struck me that what had happened now merely illustrated one of the reasons I wanted to get away.

After my first anger had subsided, I found I couldn’t honestly blame Dick. I just had to pull myself together and face up to the situation.

I turned to him again.

“It’s all I’ve got,” I said. “Lend me ten pounds and I’ll pay you back when I come back from Suvarov–if I ever do.”

Dick was the sort of man who always carried a fair amount of money in his pocket. Without demur, he handed me two five-pound notes.

I was able to off-load my belongings before the Mahurangi sailed… all except the stones and three big cases buried beneath other cargo. Fortunately, I had kept lists of the contents of each package. Dick’s lorry took eighteen of them back to the room after I had arranged to rent it again for a few weeks longer.

Before the Mahurangi sailed, I went to the skipper and every member of the crew, begging them to look after the three cases I could not off-load. And my stones! Oven stones were precious and those boys on Manihiki were bound to pinch them if they had half a chance.

But though my precious stones and cases returned safely, it took over another month before I finally did sail on October 1. We reached Suvarov on October 7, 1952.

Part 2: on the Island: October 1952 - June 1954

Chapter 3: The First Day

It was 1:30 p.m. as we chugged slowly towards the pass. I stood leaning over the gunwale, sipping from a tin of warm beer, watching Frisbie’s “island of desire”–which was now about to become my island–as we prepared to drop anchor a hundred yards off shore. This was an experience I did not want to share with anyone.

The journey northwards had been uneventful. I knew several of the crew–good-hearted, cheerful, bare-chested boys from the outer islands in search of adventure–and we carried nine native passengers as well as myself. There were five women and four men, all returning to Manihiki after visiting relatives in Raro, and they were bursting with the infectious exuberance of people just ending a wonderful holiday in the “big city.” The forward deck was cluttered with their farewell gifts; everything from newly-plaited hats to bundles of protesting chickens. Like all holidaymakers, they were taking home things they could just as easily have bought on their own island, but these were invested with all the importance of souvenirs or gifts.

They were a jolly crowd, but something had made me keep to myself for most of the trip. One might have thought I would eagerly seize the opportunity of sharing these last few days in the company of my fellow men, but in fact the opposite happened. Perhaps I was too excited; perhaps I was a little afraid.

As the captain–eyes fixed on the two rocks marking the channel–bellowed orders, I stood a little apart from the others, filled with a tremendous excitement surging up inside me. But I have never been a demonstrative man and I doubt whether the crew or passengers crowding the rails had the slightest inkling that this was a moment so remarkable to me that I could hardly believe it was really happening.

The sun beat down harshly; scarcely a ripple disturbed the lagoon as we edged our way through the pass, and the white beach, which I had last seen with Andy from the cabin top of the Tiare Taporo, came closer and closer.

My landing was hardly spectacular. Not far off the old wrecked pier the crew lowered a ship’s boat and loaded my belongings aboard, and rowed me ashore.

As the Mahurangi’s skipper had decided to stay in the lagoon until the following morning, my boat was followed by the passengers anxious for the chance to stretch their legs. So I came ashore in crowded company and almost before my crates and stores had been off-loaded, the beach was busy with women washing clothes whilst the men hurried off to fish.

Quite suddenly, though still in the company of human beings, I felt a momentary pang of loneliness. Everybody seemed so busy that nobody had any time to notice me. The crew was already rowing back to the Mahurangi, the laughing, brown women were sorting out their washing, the fishermen had disappeared, while I stood, feeling a little forlorn, on the hot white beach under a blazing sun, surrounded by a mound of crates, parcels, and black stones, unceremoniously dumped near the pier. A plaintive miaow reminded me I had a friend. Mrs.Thievery was impatiently demanding her freedom. Leaving all my packages on the beach, except my Gladstone and the box with the cats, I walked almost apprehensively the fifty yards up the coral path to the shack.

I was in some way reluctant to get there, wondering what I would find. Was it still going to be habitable? Were the water tanks still in good order? All sorts of anxieties crowded into my mind. Was there anything left of the garden which the coast-watchers had started, and what about the fowls they had left behind? Then there was the old boat. I had seen no sign of it on the beach.

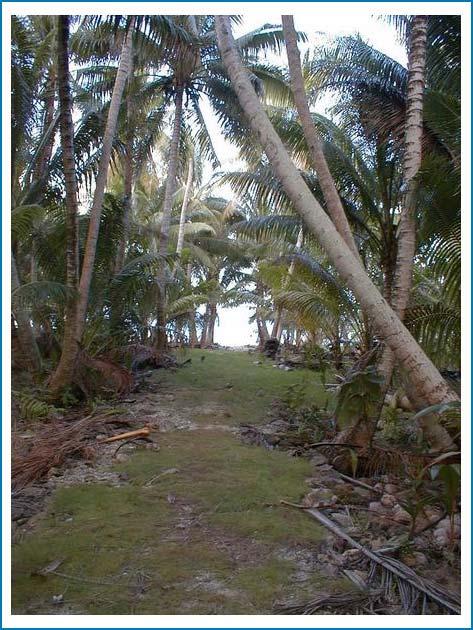

I quickened my step along the narrow path, brushing past the tangled undergrowth and creepers, the dense thickets of young coconuts, pandanus, gardenias, which had grown into a curtain, walling me in, almost blocking out the sun.

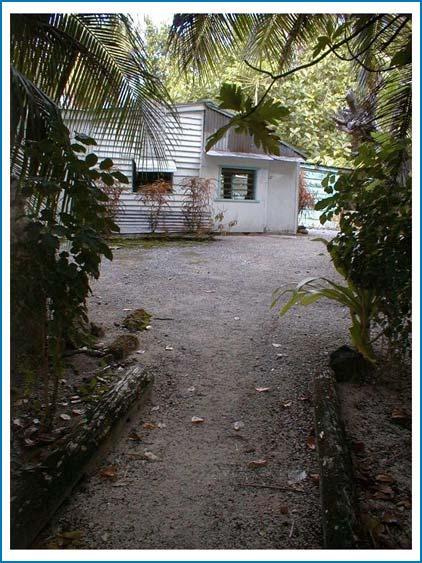

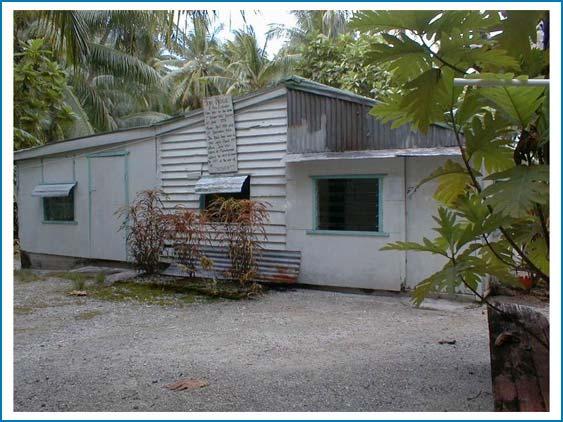

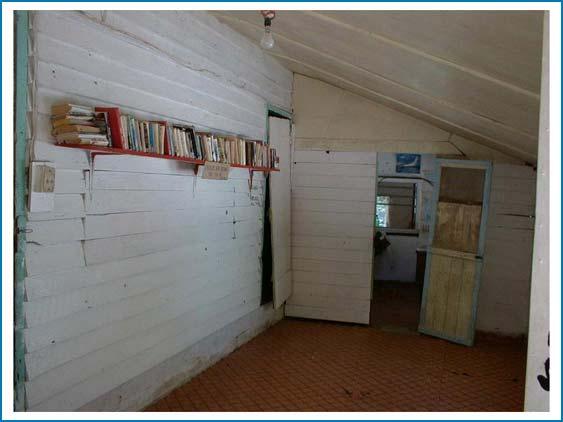

Suddenly the shack was there in front of me and I must admit my heart sank. I had forgotten the amazing violence of tropical growth; forgotten, too, just how long ago it was since men had lived here. Subconsciously, I had always remembered Suvarov when the shack had been inhabited. And now, standing there with my bag and box at my feet, I could hardly distinguish the galvanised iron roof through the thick, lush creepers covering it. The outbuildings, too, seemed almost strangled beneath a profusion of growth. Cautiously I stepped on to the veranda which ran the length of the shack. The floorboards felt firm, but when I looked up at the roof, I saw the plaited coconut fronds had rotted away.

And then, at one end of the veranda I spotted the boat, upside down–with two quarter-inch cracks running right along her bottom. I knew immediately she would sink like a stone in the water; nor was this realization made any less depressing by the knowledge I had brought no caulking with me.

It was all rather overpowering. I sat in the hot sun, mopped my brow and opened up my faithful Gladstone bag and took out the screwdriver which I had packed on top of my clothes in order to be able to unscrew the netted top of the box and release the cats. In a moment the mother had jumped out, looking around her, and I set the kitten down alongside. Unlike me, they did not seem a bit deterred and proceeded to make themselves at home immediately. Within five minutes Mrs. Thievery had killed her first island rat.

I rolled myself a cigarette, sat on the veranda for a few moments and looked around at the scene I remembered so well from my one brief visit.

The end of the veranda–which was about seven feet wide–had been walled in to make an extra room, which the coast-watchers had used as their kai room. In front of the shack the ground had been cleared to form a yard which was in hopeless confusion, with weeds and vines railing across it, dead coconut fronds blown in on stormy nights littering every corner.

At the end of the yard was a storage shed and bath-house, also overgrown with vines, while to my left were the remnants of the garden. After one glance at the tangled wreckage of its fence I turned away. Time enough later for these problems. First I must look over the shack. So, getting up, I pushed open my front door.

Oddly, this act gave me a curious sensation, an almost spooky feeling as though I were venturing across the threshold of an empty, derelict building which held associations I couldn’t know anything about. As though, in fact, I was trespassing into someone else’s past which had become lost and forgotten, but was still somehow personal because the men who had lived here must have left some vestige of their personalities behind.

Once I was over this, I went inside. The room was about ten by ten. There was a high step up from the veranda and the first thing I saw was a good solid table up against the wall facing me. Nearby was a home-made kitchen chair.

High on the wall to my left I saw two shelves holding some fifty paperback books.

Two of the walls had been pierced for shutters and I opened them to let in air and light. These were typical island shutters, hinged at the top, opening upwards and designed to be kept open with a pole.

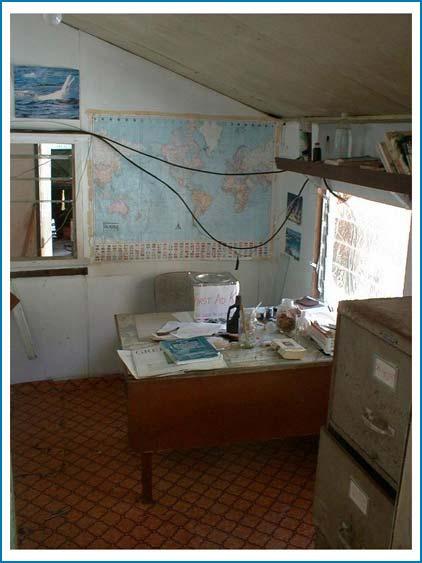

This had been the radio room, and it would make an excellent office, I thought; a sort of writing room where I could keep my few papers and, each evening, record the day’s events in my journal. And the barometer would look very handsome nailed to the wall over the table. Indeed, when I took down one or two books and riffled their pages, it did not need much imagination on my part to invest the roughly hewn table with the more dignified title of desk and visualize the small, square room not so much as four rather bare walls, but as my study.

A footstep outside interrupted my daydream, and as I turned around to see the man in the doorway, I felt a moment of irritation that even on this day I could not be left alone. But I had been unfair. It was one of the passengers, a big burly Manihiki pearl diver called Tagi, who now stood rather sheepishly, wearing nothing but a pareu, and said, “Tom, we thought you might be too busy to cook yourself a meal. When the fish is ready, come and eat with us.”

Full of contrition, I accepted gratefully, for on this day of all days I had no time to cook.

“I’ll give you a call when it’s ready,” he added cheerfully, but seemed to linger. He was filled with curiosity. “Come in and see–not bad, eh?” I asked him.

He looked around, then followed me into the bedroom which was separated from the office by a partition five-foot high, with a narrow slip serving as a door. I opened up the other shutters. This room was double the length of the first room, and to my astonishment contained a bed. It had never entered my head that I would find a bed as for some reason I had assumed the coast-watchers would have been equipped with camp beds and I had been cheerfully resigned to sleeping on the floor until I built one. I sat down eagerly to test it. It was solidly built of wood—with no springs, I was pleased to note, for I cannot stand a bed which sags. A wooden bedside table and a small shelf, which had probably been erected to keep toilet articles on, completed the furnishings.

“I wish I had a house like this,” sighed Tagi.

A practical thought now occurred to me. If the coast-watchers had left a bed, two tables, a chair and books, might they not also have left some useful articles in the kai room? I hastened to inspect it.

This room had been constructed by walling in the last third of the veranda and when I pushed open the door from the veranda and looked inside, I was astounded. In one corner was a large food safe with doors and sides of zinc netting, in another the carcass of an ancient kerosene-operated refrigerator. The fuel tank had been removed but it would still make an excellent cupboard. The hinges of the food safe seemed strong when I swung the door open and the three shelves were in good condition. To complete the furnishings, the coastwatchers had built a solid table—more of a bench, really—running nearly the length of the longest wall and facing out on to the yard, with shutters above it.

I wonder if you can appreciate the excitement I felt when I discovered this unexpected treasure. I know I had barely landed on Anchorage, yet the sight of these solid pieces of furniture—which would save me endless work—made me feel as Crusoe must have felt each time he returned to the wreck. I was so delighted that I opened the food safe and the refrigerator again for the sheer pleasure it gave me, and its platform eighteen inches above the ground, did not seem to have suffered the general process of decay. Fed from the guttering along the wall, each was almost full.

Behind the shack I discovered a latrine some eight feet deep, situated some little distance away. This handy convenience was lined with two oil drums whose bottoms had been thoughtfully knocked out. On the spur of the moment, I christened it “The House of Meditation.”

As I toured my new domain, my first sensation of dismay began to evaporate in the excitement of discovering items like the food safe and the bed, and I began to think to myself that this wilderness of creepers and vines could easily be cleared up in a couple of days. Then I had another pleasant surprise—in fact, two—after walking across the yard to take a look at the store shed and bath-house. Situated at the far end of the yard, it was shaded by parau trees which shed their hibiscus blossoms each day, so that I had to tread over a carpet of flowers to reach it.

Picking up a handful, I let them trickle through my fingers as I stood for a moment, soaking in the scheme. A gap in the trees, like a window, gave me a glimpse of the lagoon, blue and still and sunlit. If I listened carefully I could hear the thunder of the barrier reef above the faint rustle of the palm fronds, until the clamour of frigate birds wheeling overhead drowned all other sounds. One more angry than the rest seemed to dive almost on to the shack, and as I watched it, I suddenly realized that the long, low building, even though covered with creepers, was solid and that Tagi had been right to envy me, for it was, in fact, going to be the best place I had ever “batched” in. I turned round to tell him, but he had gone.

I had been so absorbed I had never heard him leave.